#hypuronector

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

cretoxyrhina, barinasuchus, clidastes, hypuronector

#my art#paleoart#paleostream#flocking#cretoxyrhina#barinasuchus#clidastes#hypuronector#drepanosaur#shark#mosasaur

297 notes

·

View notes

Text

Flocking doodles

Cretoxyrhina drowning a Pteranodon

Barinasuchus walking around at night

Clidastes preying on a flock of Hesperornis

Hypuronector doing a mating display

#paleostream#paleoart#Cretoxyrhina#Pteranodon#Barinasuchus#Clidastes#Hesperornis#Hypuronector#shark#pterosaur#crocodile#mosasaur#lizard#birds#fish

218 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Paleostream 13/07/2024

here's today's #Paleostream sketches!!! today we drew Cretoxyrhina, Barinasuchus, Clidastes, Hypuronector

#Paleostream#paleoart#paleontology#digital art#artists on tumblr#digital artwork#palaeoart#digital illustration#sciart#id in alt text#palaeoblr#paleoblr#shark#shark week#shark art#extinct shark#Cretoxyrhina#pseudosuchian#Barinasuchus#mosasaur#marine reptile#extinct reptile#Clidastes#drepanosaur#Hypuronector

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

Results from todays flocking

The first sketch was cretoxyrhina, which I could do at the same time as everyone because eating, so I did this while everyone was posting In like uh ten minutes

Then we did

Barinasuchus

Clidastes

Hupuronector

#speculative biology#paleoart#lmao#baby stream#reptile#paleontology#paleostream#flocking#art#really proud of myself#night#gecko#cretoxyrhina#barinasuchus#clidastes#hypuronector#myart#shark#shark week#babies

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Flocking Together

Cretoxyrhina

Barinasuchus

Clidastes

Hypuronector

#paleoart#prehistory#paleostream#cretoxyrhina#barinasuchus#clidastes#hypuronector#palaeoblr#made with krita

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

my hand is hurting a little from drawing stuff for work, so today's flocking sketches are simple and silly. cretoxyrhina (with a pteranodon), barinasuchus, amplectobelua, clidastes and hypuronector

#they all have 0 braincells and so am i after this week#barghestland#art#artists on tumblr#paleoart#paleoland#paleostream flocking

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Doodles from yesterday's flocking paleostream featuring Cretoxyrhina, Barinasuchus, Clidastes, and Hypuronector.

#art#paleostream#paleoart#paleontology#paleoblr#prehistoric#digital illustration#reptile#shark#shark week

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rutiodon, a Late Triassic phytosaur, basking in the sunlight of a late summer afternoon. A hypuronector, icarosaurus and other reptiles scurry and fly among the bushes.

Lockatong fm., Triassic

#drawing#art#paleoart#palaeoblr#dinosaurs#triassic#fossils#phytosaur#paleontology#watercolor#palaeontology#watercolour#dinosaur#palaeoart

89 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A male hypuronector is flushing color to his tail in the hopes of attracting a female.

#my art#hypuronector#drepanosauromorpha#reptile#triassic#scales#trees#green#blue#Prehistoric Life#prehistoric#paleoart#paleoillustration#paleontology#Mesozoic#leaves#ancient reptile

649 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rutiodon

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Wrinkle Tooth

First Described By: Emmons, 1856

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Deuterostomia, Chordata, Olfactores, Vertebrata, Craniata, Gnathostomata, Eugnathostomata, Osteichthyes, Sarcopterygii, Rhipidistia, Tetrapodomorpha, Eotetrapodiformes, Elpistostegalia, Stegocephalia, Tetrapoda, Reptiliomorpha, Amniota, Sauropsida, Eureptilia, Romeriida, Diapsida, Neodiapsida, Sauria, Archosauromorpha, Crocopoda, Archosauriformes, Eucrocopoda, Crurotarsi, Archosauria?, Pseudosuchia?, Phytosauria, Parasuchidae, Mystriosuchinae

Referred Species: R. carolinensis, R. manhattanensis

Status: Extinct

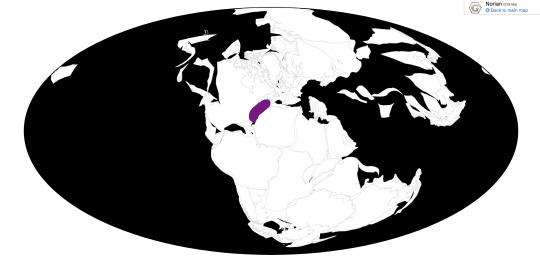

Time and Place: Sometime between 227 and 208.5 million years ago, in the Norian of the Late Triassic

Rutiodon is primarily known from the Eastern United States; there are reports from Canada, as well, but these are more dubious. All reports from the Chinle Formation that were once assigned to Rutiodon have since been given their own names. It is known from the Blue Bell Quarry and the New Oxford Formation of Pennsylvania, the Cumnock and Pekin Formations of North Carolina, and the Ewing Creek Member of the Lockatong Formation and the Passaic Formation of New Jersey.

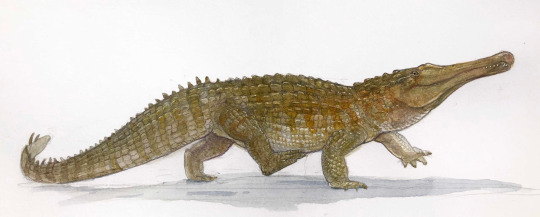

Physical Description: Rutiodon was a Phytosaur, so naturally it looked ridiculously similar to modern crocodilians - and wasn’t one in the slightest. In fact, Phytosaurs and Crocodilians have a major difference - they had their nostrils far back on the head, close to the eyes, rather than on the tip of the snout. Rutiodon itself was very long, between 3 and 8 meters in body length, making it one of the largest animals in its environment. It had a very long, narrow jaw, with large teeth inside that grew much bigger at the front of the jaw. Weirdly enough, it was covered in armored plates like modern crocodilians on its back, sides, and tail, though this is a clear-cut case of convergent evolution - Crocodilians evolved from completely different Triassic reptiles. Rutiodon had a long tail, a squat body, and legs splayed out to the sides, just enhancing how much it resembled living crocodilians.

Diet: Rutiodon would have fed on small animals and fish in its environment, using the hook in its jaw as well as the large teeth to grab onto struggling prey and hold it steady.

Behavior: Despite its uncanny resemblance to living crocodilians, it is difficult to determine whether or not Phytosaurs such as Rutiodon would have actually behaved like them. While being an ambush predator in the water it called home makes a certain amount of sense, that sense is primarily based on its resemblance to living analogues. That said, it’s also possible that the extreme length of its mouth would have aided Rutiodon in reaching and grabbing food that would be out of reach for a more snort-shouted animal (such as the large predatory amphibians that it shared a home with). It probably would have taken care of its young, though if it was more social than that it would have been more out of convenience than anything else. That said, Rutiodon seems to have been quite common, so groups of “I guess we’re all in this place together” may have been very common and a large annoyance to animals in the area trying to move through unscathed.

Ecosystem: In general, Rutiodon lived in lake environments, usually near forests with decent amounts of water present beyond the lake. Flooding and swamp-like conditions were probably favored by this genus, based on its fossil neighbors. It was found in lakes, river deltas, and floodplains that would frequently turn into extremely overflowed swamps. In the Cumnock Environment of North Carolina, it lived alongside the large amphibian Dictyocephalus, as well as therapsids like Dromatherium and Microconodon and a variety of fish and unnamed reptiles. In the New Oxford Formation of Pennsylvania, it lived alongside another large amphibian - Koskinodon - as well as the fish Synorichthys, and potentially other Phytosaurs like Suchoprion and Palaeoctonus. Finally, in Lockatong, it lived with the Tanystropheid Tanytrachelos, the Kuehneosaurid Icarosaurus, the Protorosaur Hypuronector, the Rhynchosaurid Rhynchosauroides, unnamed dinosaurs, another Metoposaurid, and a variety of fish like Diplurus, Synorichthys, Turseodus, and Osteopleurus. All that fish would have made an excellent source of food for Rutiodon, along with those small Therapsids!

Other: Phytosaurs like Rutiodon are a fun group of creatures that actually come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes, and aren’t all so similar to Crocodilians - they had weaker ankyls, no bony structure in the mouth to aid in breathing while underwater (though they may have had a fleshy one), and they actually had even more armor than crocodilians. That said, there is a chance Rutiodon and relatives are… stem-Crocodilians. What this means is, that living Crocodilians are their closest modern relatives. This is a subject of hot debate - they’re either the earliest branching members of the Crocodile-Relative group, or they’re closely but equally related to all modern archosaurs (so, they’d be equally Crocodile - and equally bird!) More research on these animals are sure to reveal further insights into their place in the evolution of the ruling reptiles.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Baird, D. 1986. Some Upper Triassic reptiles, footprints and an amphibian from New Jersey. The Mosasaur 3:125-153.

Ballew, K.L. (1989). A phylogenetic analysis of Phytosauria from the Late Triassic of the Western United States. Dawn of the age of dinosaurs in the American Southwest: pp. 309–339.

Carroll, R.L. (1988). Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution, WH Freeman & Co.

Colbert, E. H. 1966. Ancient reptile of Blue Bell. Frontiers 31(2):42-44.

Cope, E. D. 1878. On some Saurians found in the Triassic of Pennsylvania, by C. M. Wheatley. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 17(100):231-232.

Doyle, K. D., and H.-D. Sues. 1995. Phytosaurs (Reptilia: Archosauria) from the Upper Triassic New Oxford Formation of York County, Pennsylvania. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 15(3):545-553.

Emmons, E. 1856. Geological Report of the Midland Counties of North Carolina xx-351.

Emmons, E. 1857. American Geology, Containing a Statement of the Principles of the Science with Full Illustrations of the Characteristic American Fossils. With an Atlas and a Geological Map of the United States Part IV:x-152.

Gaines, Richard M. (2001). Coelophysis. ABDO Publishing Company. p. 21.

Gregory, J.T. (1962). Genera of phytosaurs. American Journal of Science, 260: 652-690.

Hungerbühler, A. (2002). The Late Triassic phytosaur Mystriosuchus Westphali, with a revision of the genus. Palaeontology 45 (2): 377-418

Jaeger, G.F. 1828. Über die fossilen Reptilien, welche in Würtemberg aufgefunden worden sind. Metzler, Stuttgart.

Kammerer, C. F., R. J. Butler, S. Bandyopadhyay and M. R. Stocker. 2016. Relationships of the Indian phytosaur Parasuchus hislopi Lydekker, 1885. Papers in Palaeontology 2:1-23.

Kimmig, J. & Arp, G. (2010) Phytosaur remains from the Norian Arnstadt Formation (Leine Valley, Germany), with reference to European phytosaur habitats. Palaeodiversity 3: 215-224

Long, R.A. & Murry, P.A. (1995). Late Triassic (Carnian and Norian) tetrapods from the southwestern United States. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 4: 1-254.

Lucas, S.G. (1998). Global Triassic tetrapod biostratigraphy and biochronology. Paleogeog. Palaeoclimatol., Palaeoecol. 143: 347-384.

Lyman, B. S. 1894. Some New Red horizons. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 33:192-215.

Maisch, M.W.; Kapitzke, M. (2010). "A presumably marine phytosaur (Reptilia: Archosauria) from the pre-planorbis beds (Hettangian) of England". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen. 257 (3): 373–379.

Mateus, O., Clemmensen L., Klein N., Wings O., Frobøse N., Milàn J., Adolfssen J., & Estrup E. (2014). The Late Triassic of Jameson Land revisited: new vertebrate findings and the first phytosaur from Greenland. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Program and Abstracts, 2014, 182.

Nesbitt, S.J. (2011). "The early evolution of archosaurs: relationships and the origin of major clades" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 352: 1–292.

Olsen, P. E., A. R. McCune, and K. S. Thomson. 1982. Correlation of the early Mesozoic Newark Supergroup by vertebrates, principally fishes. American Journal of Science 282:1-44.

Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 95.

Schaeffer, B. 1941. Revision of Coelacanthus newarki and notes on the evolution of the girdles and basal plates of the median fins in the Coelacanthini. American Museum Novitates 1110:1-17.

Sengupta, S.; Ezcurra, M.D.; Bandyopadhyay, S. (2017). "A new horned and long-necked herbivorous stem-archosaur from the Middle Triassic of India". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 8366.

Senter, P. (2005). "Phylogenetic taxonomy and the names of the major archosaurian (Reptilia) clades". PaleoBios. 25 (2): 1–7.

Stocker, Michelle R. (2010). "A new taxon of phytosaur (Archosauria: Pseudosuchia) from the Late Triassic (Norian) Sonsela Member (Chinle Formation) in Arizona, and a critical reevaluation of Leptosuchus, Case, 1922". Palaeontology. 53 (5): 997–1022.

Stocker, M. R. (2012). "A new phytosaur (Archosauriformes, Phytosauria) from the Lot's Wife beds (Sonsela Member) within the Chinle Formation (Upper Triassic) of Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 32 (3): 573–586.

Stocker, M. R.; Li-Jun Zhao; Sterling J. Nesbitt; Xiao-Chun Wu; Chun Li (2017). "A Short-Snouted, Middle Triassic Phytosaur and its Implications for the Morphological Evolution and Biogeography of Phytosauria". Scientific Reports. 7: Article number 46028. doi:10.1038/srep46028.

#rutiodon#rutiodon carolinensis#rutiodon manhattanensis#phytosaur#triassic#triassic madness#triassic march madness#reptile#prehistoric life#paleontology

206 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Paleoart of the weird, possibly glide-adapted drepanosaur Hypuronector for #FossilFriday. We don't have soft-tissues to confirm flight membranes in this species, but some osteological features imply gliding potential.

by mark witton

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hypuronector limnaios, a basal drepanosaur from the Late Triassic (~220 mya) of New Jersey, USA. Only around 12cm long (4.7″), it’s known from several incomplete fossils and was originally described as an aquatic reptile due to its flat paddle-like tail -- but the thin delicate bones and inflexible structure of the tail wouldn’t actually have made it very useful for swimming at all. It’s more likely that Hypuronector was a tree-climber like its relatives, with its odd leaf-shaped tail perhaps being used for some sort of display or camouflage.

It was probably still capable of swimming if it needed to, much like many other terrestrial animals, but it wouldn’t necessarily have been good at it. Possibly it would have moved somewhat like a modern chameleon in the water.

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#hypuronector#drepanosaur#protorosaur#archosauromorpha#triassic#art#i love drepanosaurs#weird little monkey-lizards

188 notes

·

View notes

Text

Drepanosaurs!

Recently, I talked about Sharovipteryx, a strange-looking animal belonging to Protorosauria. The protorosaurs were relatives of the archosaurs that lived from the Early to Middle Triassic period, and occupied roles similar to modern lizards and other small reptiles. One particular group of protorosaurs was quite striking in its resemblance to a modern group of animals, and yet remained one of the strangest groups of reptiles to ever walk the earth.

The drepanosaurs lived for a very short time - only about four million years during the Late Triassic - but were already highly specialized for tree-dwelling lifestyles. They are characterized by their prehensile tails, which were often tipped with sharp, claw-like hooks of bone, believed to have aided in climbing. They also possessed a “hump” of fused vertebrae in between their shoulder blades - an attachment point for powerful neck muscles, allowing their heads to quickly strike forward and snatch up unwary insects.

In terms of their lifestyles and adaptations, drepanosaurs closely resembled chameleons - a group of reptiles to which they were not closely related, and which would not evolve for at least 160 million years.

Only a few species of drepanosaurs are known, but all of them possess uniquely strange features. Megalancosaurus, pictured above, had thumb-like opposable toes found only in some individuals - possibly a sexually dimorphic trait, used by either males or females to strengthen their grip during mating. Drepanosaurus, pictured below, had a massively distended claw on its index finger, possibly used to tear open tree bark or insect nests.

(Both above reconstructions by Nobu Tamura.)

Hypuronector is so divergent from its drepanosaur relatives that it is currently classified in its own unique sister group. Its flattened, paddle-like tail suggests that it may have been aquatic rather than arboreal. However, no complete skeleton has yet been found.

(Reconstruction by Smokeybjb, showing Hypuronector as an arboreal animal.)

Due to their extremely derived and strange anatomy, classification of the drepanosaurs has been difficult. It’s currently believed that they’re closely related to the other arboreal protorosaurs, such as Sharovipteryx, as well as the long-necked tanystropheids.

21 notes

·

View notes