#how to draw New Yorker cartoons

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

[id: three redraws of Drawfee pictures as Lockwood and Co book characters instead. 1. l&co in drawfee hosts' pose with George in center, Lockwood and Skull are leaning on him from either side and Lucy's leaning on Lockwood. thers's a semi-transparent original photo in the empty space. drawing is titled "Drawfee & Co". 2. Lucy, Skull, George and Lockwood look as if they have a zoom call. Lucy is googling "how to fire your own coworkers"; Skull's texting in discord; George is playing a card game on his phone; and Lockwood is happily shouting to the point where it makes his screen blury. 3. drawing of chibi Skull points at the fire behind him, it's captioned "If anyone asks, I did this". dialogue between Skull and Lockwood takes place: 'but what did i do? there's so many things that i can claim-' 'yeah' ' -'cause im violent' drawing immitates screenshot of a youtube video titled "Drawing New Yorker Cartoons Based ONLY On Their Captions"./end id]

l&co x drawfee crossover because why not

#im not taking criticism in character assignment i am correct in every way#lockwood and co#l&co#drawfee#crossover#anthony lockwood#lucy carlyle#george cubbins#the skull#skull in the jar#skull in a jar#locklyle#sketch#sketch dump#shitpost#redraw#described#artpost#karina''s “i did this” lives in my head rent free

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay, was thinking about it and I remembered a lot of you were very young or not even alive for this, so:

When 9/11 happened I was 12 and had just started 7th grade. I grew up in a suburb of New York City. 12 people from my town died, including a firefighter whose son was in my younger brother's CCD group.

Things changed SO fast. Practically overnight. Suddenly, we were all hypervigilant, and after the immediate response of assistance from around the world, the prejudice was oozing from nearly everywhere. In northern New Jersey, we had and still have a large west (Middle East) and south Asian population. They were hit the hardest.

People freaked out just because a mosque was going to be built in lower Manhattan within several blocks of Ground Zero at one point. It was ridiculous and the Islamophobia was so fucking awful and infuriating. It still is. It didn't go away. For the most part, New Yorkers are usually good to each other because there's literally someone from everywhere here, but this was legitimately terrifying. People would even attack Sikhs - who weren't Muslim, Sikhism is its own thing - because they saw the turbans and made a decision based on racism (i.e. bin Laden had a turban so these people must be like him).

The "patriotism" was miserable. "Freedom fries" happened because people were mad that France didn't want to go into Iraq with Bush in 2003. We all thought it was stupid then too.

The Chicks (formerly known as the Dixie Chicks) got blackballed because they came out against said war. They were one of the biggest country acts in the world at the time. In general, country music went through a massive tonal shift post-9/11 and became far more "patriotic" and conservative. Johnny Cash wouldn't have recognized it.

The Flash movies that inevitably popped up satirizing politics were...something. You can find most of them archived on YouTube these days. But that was how the internet tended to cope back then.

The shift from happiness to paranoia was so fucking fast. I went from a world where my biggest concern was pre-ordering the GameCube to being worried about politics and death all the time. All the news showed was footage of people dying for weeks. Politicians started using the footage in commercials. You just had to keep reliving the trauma of it over and over again. I stopped watching the news.

It was, looking back on it, a huge galvanizing point for the American right. Politicians started using 9/11 to justify so many things. This was where I began to see as a young teenager that you could use people's prejudices to get a grip on power and get what you wanted. I didn't like it.

People started drawing memorial art almost immediately. The phenomenon of memorial art being done decades later with cartoon characters still persists on deviantART to this day, but when it started, it was mostly people doing vent art because it's really upsetting to be a kid and see death on that scale on the news.

It took me 15 years to go back to the site after 9/11. I'd been as a kid in 1997 and I went up in the South Tower with my family. I didn't set foot there again until 2016, 15 years after the attacks. I found the name of the firefighter whose son was in my brother's CCD class. It was surreal.

This chapter of American history arguably closed for many people in 2011, when bin Laden was killed in a raid. I remember watching the Mets play the Phillies that night. Daniel Murphy, who I'd named a cat after two years earlier, was at bat, and suddenly the crowd started chanting "USA." I used my Blackberry to check the news and that was how I found out. I was a senior in college, about to graduate. I don't even remember how I felt, just that the way I found out was so fucking weird.

It was a really stressful, bizarre climate to grow up in. In the time between my 12th and my 22nd birthday, I saw my entire world get turned upside down overnight, massive waves of prejudice, unnecessary wars that killed even more innocent people, literal war crimes (tw: rape, murder, prisoner torture, every other bad thing you can think of under the sun), and the rise of false patriotism and nationalism, which you can still see the right wing harnessing today.

If you're going to mock something here, mock the false patriotism. Mock "Freedom Fries." Mock George W. Bush. Just...don't mock the actual moments where people died. Too many innocent people died from the attacks themselves, the Islamophobia afterwards, and the wars that followed. That shit isn't funny.

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

medium vs message vs subject

tw for for discussion of depression, mental illness and suicide.

I had a Not Great reaction to a New Yorker Cartoon, lol. Gave me a lot of thoughts and feelings, so I decided to write about them here.

(Image description: a black and white drawing posted on Instagram. In the drawing, a man plays fetch with his dog, both of which are accompanied by a thought bubble. In the man's thought bubble, it says "I love how he finds joy in the little things." In the dog's thought bubble, it says, "The emotional burden of alleviating his depression is crushing me." End description.)

I had a pretty visceral reaction to this cartoon. At the lowest points of my depression, "my loved ones are crushed by the burden of caring for me" was a regular, invasive thought, and the thought that immediately followed was, "they would be better off without me."

These thoughts were suicidal ideation. Seeing a cartoon use my suicidal ideation as a punchline, particularly in such a way that affirms the ideation? Felt like a gut-punch.

I left a comment saying this, with the addition of: "I'm not saying jokes about this topic cannot be made. They certainly can be. But they need to be better than this one."

Most of the replies agreed that the cartoon was insensitive. But one person asked: "don’t you think the fact that it’s a dog, who couldn’t possibly think that, means the cartoon is calling this pattern of thought you’re talking about absurd?"

To which I replied:

"I understand what the joke is saying perfectly well. What I'm saying is that the way the joke is presented gave me (and evidently others) an involuntary trauma response. It's presented without sympathy or sensitivity for those having these types of thoughts. There's no real commentary on the nature of suicidality beyond "this is an absurd thing to think." It comes across as mean-spirited. I'm not saying that was the cartoonist's intent. I'm just saying what my experience with the cartoon is. And before anyone jumps in with "it's not that deep" - single gag cartoons are not that deep, but suicidality very much is. A single gag cartoon cannot be as sensitive and nuanced as the subject warrants, resulting in a not great joke."

I kinda hate when you critique something, and someone comes in with what ultimately amounts to be "you just didn't get it."

Like, I did get it. I still didn't like it. Why? Because the joke sucks.

I know that suicidal ideation manifests in absurd thoughts. I think we all kinda know that. But what is the cartoon saying beyond that? What is it saying about the absurdity? Not a whole lot. The joke is just "mentally ill people sure are crazy!"

Yeah dude, we know.

Make a better joke! Say something more! Say it with the sensitivity and nuance the subject deserves! Say it through a medium that allows you to do that!

"But, but if the artist's intent isn't to be mean and reductive, then--"

Shut up. Shut up. It doesn't matter. Someone didn't mean too stomp on your toe, but your toe still fuckin hurts, and the person responsible for that hurt is still the person who did the stomping.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

As a mario enjoyer I’m curious abt ur interpretation of the bros origins. This isn’t rlly asking what is canon cuz the series doesn’t rlly prioritize continuity and it’s all debatable etc. Personally I have a vague timeline in my head and I like to draw from pretty much all mario media but sometimes that makes contradictions. A lot of mario media has mario from new york (new donk?) and then ends up in the mushroom kingdom through a warp pipe. In yoshi’s island it seems his parents live in the mushroom kingdom though. And in partners and time baby mario and luigi are there during the shroob invasion in the past. I love partners in time a lot but I also rlly like mario being a new yorker so it’s hard to have my cake and eat it too. I guess he could be born in the mushroom kingdom then move to NY then come back? I’m not too sure. I’d like to know your take on it.

SORRY FOR TAKING SO LONG TO GET TO THIS. yeah i'm gonna be honest my take is sort of vague and meaningless because as a kid i just wanted every single thing to take place in one universe. and i sucked at making that happen. to me it sort of went like, they were delivered / born / whatever in yoshi's island to their parents. then those guys were like wait these arent our kids. then they were delivered to their actual parents or whatever (i have never really played yoshi's island i'm sorry) and they lived there for a couple of years and probably spent a lot of time with peach / around the castle because i figure if kamek was aware of the whole star children thing it's likely that at least some people in the mushroom kingdom would want them there for that. and mario has fought bowser a couple of times as a baby so who knows.

then after partners in time rolls around their parents who were sort of letting them hang around the castle went ermmmm actually nvm. we are going to brooklyn 1990 because it is Much Safer There. [looks into the camera like in the office]. and then they kind of lived in new york city for 20 years before getting dragged back to the mk in a tragic plumbing accident. even though i know they love their jobs as plumbers and are genuinely passionate about it i will admit that i like to think that mario wanted to go into paramedicine or nursing and luigi to university for aerospace engineering or something but it wasn't really feasible for them before the great eeby deebing 😔

i honestly don't really know how i imagine their parents, a lot of people have really lovely designs and concepts for them, and there's been a lot more stuff on them since the mario movie came out and gave people these dubiously canon characters to work with, but they just don't come up much in my mind. i don't want to be like "they died 💀" but also like mario and luigi are in their mid 20s and if they somehow ended up in the mushroom kingdom i figure their parents would also be able to go back there. but then you think about like the whole deal with the cartoons how the way between worlds was sealed and stuff and it just gets confusing to try and make everything work 😭

sorry i'll probably be able to come up with something more reasonable tomorrow after i sleep and give it some proper thought but i think in general i just have the skeleton of a timeline LMAO

delivered by stork yoshi's island style -> partners in time happens -> I Am Not Letting My Babies Fight Aliens We Are Going To New York City -> WHUH OH! PLUMBING EVENT GONE WRONG???!?!?! [NOT CLICKBAIT] -> basically every other game.

it's also a little tough to balance because judging by PiT they seem like they would have known or have learned at some point that they like. are actually from the mushroom kingdom and stuff. which idk how you'd explain that to your kids but whatever

there are honestly a couple of ways i imagine their backstory, like saying oh they fell into a warp pipe themselves while exploring baby style after PiT and were adopted and raised in brooklyn or just going oh they have their own room in the castle in PiT so they probably lived there as kids or just saying they were just born in brooklyn and ended up in the mk like in the the cartoons and ignoring yoshi's island and PiT but none of them are very cohesive or really make much of a difference in how i imagine their characters yknow?

i have the same dilemma as you because i also love mario being a new yorker but parnters in time is my favourite M&L game

don't worry though once get really into mario again i'm sure my favourite scenario will come to me in a prophetic vision. and then i will get back to you 🔥💯‼️

#talk tag#ask tag#sorry idk how coherent is i'm just experiencing the 4 am chattiness that plagues us all#(<- only a me problem)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The New TMNT Mutant Mayham Got Me Thinking About Why I Like the Turtles

So, I finished watching the latest movie Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Mutant Mayhem and it got me thinking about what it is that I like about the franchise. Although, not necessarily because I liked the movie. In fact, I found it kind of difficult to watch at points and I was having trouble understanding why at first. It had really good animation and really good voice actors, and I really liked the third act where a bunch of New Yorkers worked together to help the turtles take down the massive monster.

But I found myself not really enjoying it as a standalone movie and I really didn't find a lot that I liked as a TMNT fan. Consider this post as my way of trying to understand this.

The first way I'd like to think about this movie is as something on its own, regardless of the franchise it represents. After all, TMNT has had a lot of different interpretations with different flavors, so, what did this one have to offer? As I mentioned, really good animation and voice acting...but also a LOT of pop culture references and gross out humor. This franchise is not new to this kind of thing, but I was noticing that a lot of scenes would spend about 1-2 minutes every 5 minutes on drawing out a joke that seemed to reiterate "teenagers are cringy and gross". Perhaps the arguement could be made that, the film is labeled as a comedy, so it is excusable, but I don't quite agree with that. Comedy that is well-written is not simply a long string of goofiness; it's a punchline. A punch is something that needs to be planned and well-timed, and rapid punches can only be done effectively with focus and endurance, otherwise, it turns into a less effective equivalent of flailing your hand trying to slap someone, in which it is more annoying than impactful. There's not a lot of moments or jokes that stand out because a lot of them blurred together for me.

The heart of the message is important for any story. Each iteration of the Turtles seems to tie into the idea of trying to deal with how impressionable teenagers are, including Mutant Mayhem. With this recent film, the turtles are obsessed with earning a name for themsleves because they feel outcasted. It was interesting of a concept because this kind of thing was actually explored in the 1990 turtles movie, where the Shredder was recruiting teenagers throughout New York who felt misunderstood and convincing them that the only way they could live freely was to take from others. One of the human characters was a teenager who was following Shredder at first, but he changed his mind after Splinter and the turtles convinced him that there was no honor or true happiness in that path. The turtles were the role models in that situation, though the 2011 TMNT cartoon was an instance where the turtles had to learn hard lessons that helped them grow. Technically, Mutant Mayhem addresses this by saying the turtles needed to be confident in themselves and trust others, since trusting April and choosing to help her when her bike got stolen was what ultimately led her to doing a news report to convince New York to help them. The message is there, but it just felt muddled. In the first episode of the 2011 TMNT show, they saw April get kidnapped and failed to save her, Splinter makes a comment that the turtles will have to wait until next year to go outside again (though, I personally believe Splinter was just pretending to be dismissive of April's fate so as to spur the turtles) and Donnie responds "You didn't see into her eyes. The way she looked at me. Helpless. She needed my...our help." It's a small moment in a short episode, but it's a clear moment of empathy, even with very slight but subtle humor woven in, but not enough that distracts from the seriousness of the situation. Mutant Mayhem had chances to do this, like when Mikey thought Mando Gecko was buried under rubble but it turned out to just be his severed tail. It was a funny reveal, but I think it would have been more effective if there had even been a few seconds to show Mikey's panic and maybe even scratching at the rubble to allow for a moment of seriousness, that would have actually made the punchline hit more effectively.

In terms of the message, of having the turtles and other mutants feel like outcasts, I do feel like this particular story has been told a lot in movies nowadays (though I don't want to blame the movie for that, it's simply the current trend) but I do think there are movies where this kind of story has been told better. As far as films I look to as a personal golden standard, I think of the Iron Giant, who had to prove himself a hero by choosing not to be a weapon, but there are more recent films I think tackled this well, such as the Bad Guys, which had anthropormorphic animals trying to redefine their cultural stereotyping and personal beliefs about themselves as bad guys by choosing to do good. Technically, Mutant Mayhem does this same story, but I think it lacked a moment of respect for its message. And I don't think it's fair to comedy and storytelling to say "It's a comedy, it doesn't need to take itself seriously" because, for example, Bad Guys is technically a comedy too yet still manages to stirke a balance of comedy and character conflicts that showed you can have fun in the bad times, but mistakes do still have consequences. Mutant Mayhem had small moments like this, but it lacked a confidence in itself.

I think lack of confidence in itself was what I felt most with this movie. That was the main theme between the turtles and April, and technicallly that did get resolved as they worked together with the New York populace, though it all felt like a side story to Splinter's arc about not trusting humans. In a way, the turtles never quite got their big stand-out moment in their own movie. I guess that was the point of this movie, where the turtles aren't supposed to be important, since trying to attain that is what got them in trouble. It all technically works narratively, but I still had a hard time feeling satisfied.

Admittedly, perhaps some of this comes from my history with TMNT. One of my favorite Turtles media is the 1990 movie with a close second being the 2011 Nick cartoon, though I didn't get around to all of the other propteries, I still tried to stay informed. By the end of Mutant Mayhem, I was thinking about these other versions and trying to remember what I enjoyed about them so much and I really do enjoy those past versions. But I wanted to be cautious about not liking Mutant Mayhem just for interpreting things differently, since doing something different doesn't make it bad, but I think it still needs to be done well in order for the changes to work.

When dealing with so many iterations, it may not be fair to compare Mutant Mayhem to those before it, but I do wonder at what kind of identity that it offered of its own. As mentioned, these turtles lacked confidence in themselves and leaned very heavily on their jokes, to the point that I had trouble telling them apart personality wise. Even the old 80's cartoon was very careful in making the turtles distinct in how they reacted to situations despite their identical designs (like you could always rely on Raph making a snappy comment). Even with the other mutants, I liked that they were given the opprotunity to befriend the turtles, but they all blended together character-wise as well, since their motivations were all the same with only minor differences in how they behaved. For the turtles, things like Leo's over-responsibility and crush on April or Ralph's glee for violence felt more like sidenotes, and I'll try to explain why. Throughout Mutant Mayhem for instance, Ralph's anger was a running joke, saying he had anger issues...but I never got the sense he was angry. He was actually quite happy all the time and never took anything seriously, he just so happened to really like punching things and Splinter even lost his temper more than Ralph. A lot of the movie was like this, in telling things but not really showing it. And I think showing the personality traits rather than telling has been done well in the past. This is where I think it would be best to make comparisons: In other iterations, like the 1990 film, Ralph's anger is more apparent because we got to see how it resulted in him losing more than one fight he tried to do alone and almost dying, how he had to learn to manage his anger to help his brothers. In the TMNT 2011 cartoon, Ralph had a mean-streak, which caused problems with Mikey not feeling secure, but they would eventually work it through, and it was clear that Ralph's anger just stemmed from his immense passion for things, which sometimes led him to befriending pets or being the most empathetic of others in certain situations.

There were a variety of changes to the turtle's with their personality and backstory. As mentioned, change isn't bad but it should be done with a clear vision and executed well, especially when dealing with such a long-running franchise. I wasn't sure what to think of Leo's crush on April, in part because it didn't really have an impact on the story (as the turtles would have likely retrieved her stolen bike regardless--and if the only reason they helped April was because of Leo's crush then I think it reflects poorly on the turtles. One might argue Donnie had a crush on April before they went to save her in the 2011 TMNT cartoon but I think it was clear that Donnie's crush in the first episode was treated more as a fun joke and he expressed wanting to save her because they were the only ones who could help her and had a responsibility to). The other thing with Leo's crush in Mutant Mayhem was that it felt like it didn't add to the experience, not really being treated as a joke or committed to being explored like with TMNT's Donnie, and it didn't feel like Leo and April were given moments to even get chemistry. There were a lot of little decisions like this that made it feel added on rather than woven in. Other changes involving the backstory had a bigger impact on my experience and it relates to the fight scenes.

A lot of these past versions delivered when it came to the fight scenes, even the the live action 1990 movie. Part of the appreciation for it I felt like had to do with the fact that the turtles, no matter how young and fun-loving, do still have a level of seriousness for their craft. Mutant Mayhem had fights, but they kind of went by fast. There was some cool editing but not really a lot of moments that stood out. They largely felt like street fights, something chaotic and just scrambling to hit something. The only time I can really play back a fight in my head was also the one time it felt like a ninja was fighting, when Splinter was saving the turtles, but even that felt a little off, I think because of this Splinter's backstory. I might be biased in saying this, but I found myself missing the backstory of Splinter being either a pet of Hamato Yoshi or even the man himself, as it gave more creedance to the turtle's ninjustu. Even the Rise of the TMNT, which was before this movie and considered one of the more comedic of the recent iterations, still had Splinter originate as an honorable master of martial arts who got turned into a rat and raised the turtles to protect them. It was comedically portrayed but still faithful. It was to my surprise that the 1990 live action film was actually very faithful to the original comic adaption, in which Splinter was a pet rat who was close to Hamato and had a grudge against Shredder. Either backstory works I think because it has a level of believability. The only time I had heard of the turtles being trained by self-defense books was from the Micheal Bay 2011 movie. It is a goofy explanation, and it could work, but I'm not sure if Mutant Mayhem managed to make it work, as I feel it didn't quite work in the 2011 film either. It's not to say that Splinter has to be a martial arts master, but I feel like him and turtles learning ninjitsu from a legitimate source then gives more respect to ninjitsu. There's no sense of history and it makes it feel like, if Splinter found a book on boxing, then they could have just as likely become the Teenage Mutant Boxer Turtles and calling themselves ninja was just a means to an end.

I suppose all this to say, Mutant Mayhem was not a bad movie, but it is not one I would recommend, as I feel there are other films and even other Turtles media that can provide more refined versions of what this movie wanted to offer. I appreciate anyone who read to the end of this and allowing me to share my thoughts. Have an excellent day.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Assessment 1

2. conduct research into their life stories

Lisa Hanawalt - Bojack Horseman

She has been friends with show creator Raphael Bob-Waksberg since high school and they spent a lot of time imagining ideas for TV shows and riffing on the doodles in Hanawalt’s sketchbook. and previously worked with him on the webcomic Tip Me Over, Pour Me Out.

“He would look at my sketchbook and make up little stories about the characters, and we would make jokes about, like, what kind of TV shows we’d make, although I don’t think either of us honestly thought we’d be doing that later in life.” - Hanawalt

“I think we had a mutual prep period or something where we both didn’t have to go to class, and we’d just, like, sit in the green room and chat all day. She would doodle stuff and I would, like, make up voices for them, or we’d talk about different cartoon characters we made up. I don’t think either of us assumed we would one day be actually professionally making a cartoon together.” - Waksberg

Years later, it was with Hanawalt’s animal drawings in mind that Bob-Waksberg conceived his original treatment for BoJack. In 2011, he emailed to let her know that he’d merged her illustrations with his idea for the show

It was critically acclaimed, but not in the initial release of the first half of the show. People thought the show seemed overdone and a copy of other adult animations and specifically criticised the animation style. It was only in the second half/nearing the end of the show that revealed how Hannawalt and Waksberg subverted audience expectations.

BoJack was Netflix’s first original animated show and it was also Hanawalt’s first foray out of flat artwork and comics. She found the human characters harder to design than the animal ones. When the actors were cast, their natural timbres affected the visuals that would go along with them.

Hanawalt’s hybrids make use of the estrangement between human and animal.

Hanawalt makes use of comedy. she uses puns, pop culture and animal references, and sight gags in nearly every shot.

She uses iterations of famous paintings to foreshadow events later in the show. E.g: the painting of ophelia foreshadowing Sarah Lynn’s death.

She also makes great use of symbolic imagery.

She’s always been a big fan of horses. They're oddly paradoxical because they weigh about a tonne but they're also easily spooked by things as unassuming as a bucket.

"She relates to the horse, and describes herself as a “super-anxious person” plagued by personal scary buckets.” - The New Yorker, The Origin Story of the Depressingly Good “BoJack Horseman”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Turtlethon Extra Slices: “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II: The Secret of the Ooze”

US Release Date: March 22, 1991 UK Release Date: August 9, 1991

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II: The Secret of the Ooze is the follow-up to the hugely successful first live-action Turtles movie, released in the US through New Line Cinema. Much has changed in the year since the original TMNT film made its debut, coinciding with Turtlemania reaching its peak. Its director, Steve Barron, reportedly bowed out during post-production, the project heading in a different direction than he had originally envisioned. Judith Hoag, who played April O’Neil, was also unhappy, feeling that the finished product was too violent and that the more spiritual elements of the original story – I’m guessing this would have related to the mystical connection between the Turtles and Splinter ultimately confined to the campfire scene – were left on the cutting room floor.

As discussed in the entry for the first movie, the darkness present in that initial cinematic Turtles outing generated some consternation, not only from pundits and parental groups but from certain parties concerned with the business side of TMNT, most notably action figure licensee Playmates. What’s remarkable is that the final cut had already been watered down from what Barron had envisioned: most notably, the scene where Shredder’s right-hand man Tatsu took out his frustrations on one of the Foot Clan hoodlums was intended to have been considerably more violent than it ended up being. The pencilled-in punk rock soundtrack was swapped out for more commercially palatable hip-hop and new jack swing material that would shift plenty of units when the inevitable cash-in “Music from the Motion Picture” CD was released. These considerations would go on to dramatically impact the creative direction of the sequel: if there was so much money to be made in a gritty Turtles movie, so the thinking went, surely a brighter, agreeable one would draw in an even bigger audience.

The clock was also ticking. It was apparent to all involved that the dizzying levels of success the Turtles had achieved would be fleeting; inevitably kids would move on to whatever the next hot new trend would be before too long, and so there was a need to rush the second movie into production almost immediately after the first proved to be a hit. Barron was replaced by Michael Pressman, whose work in the years immediately prior had mostly been in the made-for-TV-movie field; meanwhile Paige Turco would be drafted in to fill the role of April. External factors would also lead to the Turtle whose original voice actor had the highest profile needing to be re-cast: Corey Feldman was dealing with addiction issues during the production of TMNT II, and so the decision was made to replace him with Donatello’s in-suit actor Leif Tilden for this chapter of the trilogy.

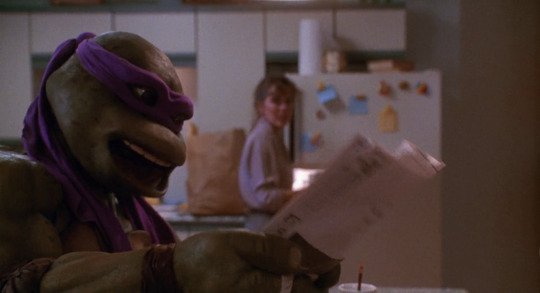

We open with shots of various New Yorkers enjoying pizza before being introduced to Roy’s, where delivery boy Keno (Ernie Reyes, Jr.) is tasked with making yet another visit to the home of April O’Neil. Upon arriving, he spots a robbery in progress at a neighbouring shopping complex. Keno confronts the crooks and uses his martial arts prowess to take out a few of them, but soon finds he’s bitten off more than he can chew, their numbers overwhelming. The Turtles intervene, having spotted the raid in-progress from nearby, and so an extended fight scene unfolds.

It’s immediately apparent how much things have changed from the first movie, where in their initial appearance the Turtles were barely glimpsed at all, acting quickly under cover of darkness to avoid being seen. Here they show no such restraint, yukking it up and engaging in slapstick reminiscent of the 1987 cartoon at its worst as they use toys and other items dotted around the stores they wander into to defeat their opponents. (I’m reminded particularly of the atrocious fight in the baby store from “Four Turtles and a Baby”, one of the lowest points of the entire series.) Jim Henson’s Creature Workshop has continued to develop the technology used in bringing the Turtles to life, something on show here: from the outset we can see that the team are now more wide-eyed, expressive and capable of pulling off cartoony expressions than before. As a result, they more closely resemble their animated counterparts from the Fred Wolf series.

A particular sequence of note involves Michaelangelo wielding sausages as makeshift nunchucks; this was removed from the initial UK release of the movie on the instruction of the then-director of the British Board of Film Classification, James Ferman, who was unwilling to recognise any distinction between the improvised weapons and the real thing. From the Region 2 DVD release in 2002 onward this scene was restored, the twin moral panics of the Turtles and nunchucks corrupting the youth both by then only vague memories which had long since receded out of the public consciousness.

Keno is instructed by the Turtles to call the police and request someone pick up the defeated robbers; by the time he returns not only have the crooks all been tied up, but his pizzas have been taken, a wad of cash left in their place.

April returns to her fancy new apartment at the same time the Turtles sneak in the window. The group yuk it up some more while also discussing the defeat of the Shredder at the end of the previous movie and their need to find a new home, given that the Foot Clan learned of the existence of their old lair. Splinter soon emerges and reminds his sons of the importance of remaining invisible as ninjas. He goes on to add that thoughts of Shredder should remain buried in the past.

At a garbage dump, a hand and a familiar bladed gauntlet are seen emerging from the debris. By sheer coincidence, this site was also selected as the fall-back location for the Foot Clan, its remaining members seen arguing among themselves in a hideout nearby. Tatsu again flies into a rage, declaring himself the group’s new leader, but this proves to be short-lived: Shredder returns, remarkably resilient for someone who up until now was thought to have been crushed to death by a garbage truck. He declares his intentions to target April as a means of getting back at the Turtles and Splinter, the only thing he now cares about.

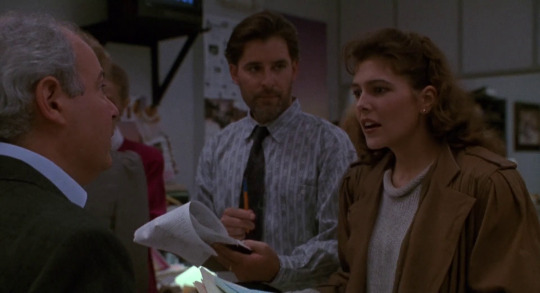

Reporting for Channel 3 News, April chats with a spokesperson for Techno-Global Research Industries (TGRI), Professor Jordan Perry, at the site of a contaminated area the firm is now working to clean up. Perry says little of any substance in the piece, which is watched on TV by the Turtles and Splinter. Freddy, a member of April’s news crew, sneaks behind a taped-off area once filming is over and discovers giant dandelions, a tell-tale sign that something has occurred with a huge environmental impact. Later, Perry informs one of TGRI’s employees that all the mutated dandelions must be removed, explaining that allowing the press to film there was the best way to ensure no-one suspected anything unusual was taking place.

Unbeknownst to April, Freddy, the rookie on her crew who discovered the giant dandelion, is an undercover member of the Foot. He takes his findings back to Shredder. Now clad in snazzy new purple attire, Shreds orders Tatsu to prepare his troops for an upcoming mission.

Splinter entered an extended period of meditation after watching April’s report, and upon her return home summons her along with the Turtles to the roof of the apartment building. There, he reveals that he kept the cannister that contained the ooze which, fifteen years earlier, transformed him along with the Turtles into their current forms; when re-assembled, the initials printed on it read “TGRI”. Now, he tells his students, the truth about their past has re-surfaced, and with it a potential danger to the people of the city.

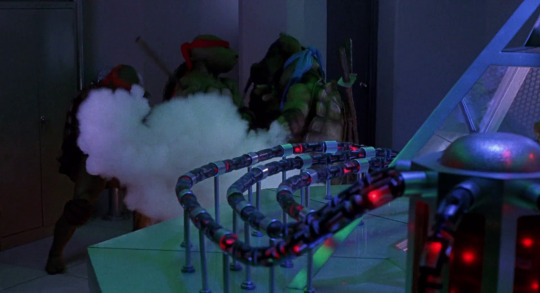

Professor Perry is seen in a lab on TGRI’s premises, examining records that show only one cannister of the type possessed by Splinter remains, the rest marked as “disposed”. He’s soon taken captive by Tatsu and a group of Foot ninjas. Later, the Turtles sneak into the building and examine the records on Perry’s computer, only to be confronted by Tatsu and his men, who goad their enemies with the prospect of claiming the last remaining full cannister. A fight breaks out which initially seems promising but again the Turtles are limited to performing slapstick routines with the items scattered around them, largely forbidden from using their weapons. Things peter out with Tatsu hurling a smoke bomb at the green teens, allowing both him and his men to escape.

Later, the Turtles begin preparing to move out of April’s apartment when Keno wanders in, suggesting that given the staggering number of pizzas she orders she may as well take another from an unsuccessful delivery intended for a neighbour. April struggles to make excuses after the delivery boy spots Michaelangelo’s nunchucks sitting on the counter, attempting in vain to demonstrate her proficiency with the weapons in a sequence that I’m sure severely traumatised James Ferman. None of this convinces Keno, who spots the Turtles hiding in plain sight and forces them to come out into the open. After learning of their history, he reveals his own knowledge of the Foot and their recruitment activities, suggesting he could work his way into the operation on their behalf, an idea endorsed by Raphael but swiftly shot down by Leonardo and Splinter.

Under duress from both Shredder and Tatsu, the kidnapped Professor Perry begins the procedure of using the remaining cannister of ooze to transform the two most vicious animals the villains could find. Meanwhile the Turtles say their goodbyes to April, heading underground in search of their new home. Raphael’s temper (and his on-again, off-again tension with Leonardo) flares up again as he refuses to participate in this exercise, stomping off to find a better use of his time. Moments later, Michaelangelo unwittingly stumbles upon an abandoned subway station, complete with unused train carriages, and the group begin to discuss the possibility that this could serve as their new residence.

At the Foot’s hideout, Shredder demands from Perry that the mutants be ready for battle with the Turtles as soon as possible, noting the failure of both his ninjas and himself in defeating the team, and that the next battle will be “freak against freak”. At Channel 3, April is pressured by a station manager called Phil – Charles from the first film is never mentioned – to do a more ratings-friendly story on swimsuits rather than pursue her investigation of TGRI.

Back to Shredder again. Having tired of waiting around, he demands Tatsu remove the bar keeping the two new mutants in their makeshift junk cell, a grey hand and a brown furry one occasionally poking out. Dutifully the underling does so, and the beasts are revealed: snapping turtle Tokka and wolf Rahzar, though neither are named at this point. After Shredder declares himself to be their master, the mutants mistakenly think him to be their “mama”. Both are, to the great frustration of Shredder, mere infants; it’s explained to him by Perry that this should have been obvious from the outset. Like the Ninja Turtles, who in this continuity grew from infants to adolescents over the course of fifteen years, Tokka and Rahzar will learn and develop over time, but for now are far from the fearsome warriors the masked villain had envisioned. Shredder orders them to be terminated, but Perry pleads that there must be a use for them, demonstrating that their relative strength can make them useful in carrying out tasks around the hideout.

It’s remarkable that we’re forty minutes into TMNT II and Shredder, an intimidating and grandiose figure in the first movie, is following the exact same trajectory that his animated counterpart did back in season two of the 1987 show, already becoming an ineffectual schmuck who clearly has no clue what he’s doing. With that observation out of the way, we now return to the movie, already in progress.

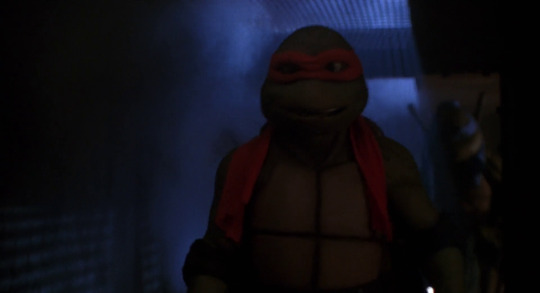

Raphael helps Keno to infiltrate the Foot’s operation as per his earlier suggestion, the delivery boy impressing a recruiter in a combat exercise. As a further test, Keno is required to remove a set of bells from a mannequin in a cloud of smoke; after doing so with unseen help from his Turtle ally he becomes a full-fledged member of the group, later reuniting with Raph in the scrapyard hideout. It doesn’t take long before both are spotted by Tatsu. Raphael orders Keno to flee, soon finding himself face-to-face with Shredder.

Keno relays the news of Raphael’s capture to April, and the other Turtles soon stake out the scrapyard in search of their brother. Conscious that they’re walking into a trap, the group discover Raph gagged and tied up. Shredder has the remaining Turtles placed inside a net, raised via a crane and about to be dropped on a set of scrap metal spikes until Splinter intervenes, a well-placed arrow cutting the team free ahead of time. The reunited Turtles continue to deliver quips and one-liners more than kicks or punches and find themselves vastly outmatched by the brute force of Tokka and Rahzar, with Donatello being thrown through the roof of the shack where Professor Perry is being held. After Michaelangelo discovers a manhole leading back to the sewers, the group escape with Perry underground; Tokka attempts to give chase but is too big to fit, and after getting stuck prevents the Foot from pursuing the team further.

Perry is amazed by the existence of the Turtles, and in a bit of role-reversal pieces together the events that led to their origin and recounts these to them before they can reveal their backstory themselves. After being introduced to Splinter, he goes on to explain to the group the properties of the substance that caused them to take on their current forms: “an unknown mixture of discarded chemicals was accidentally exposed to a series of radiated waves, and the resulting “ooze”, as you put it, was found to have remarkable but dangerous mutinogenic properties.” Though the cannisters were intended to be buried, one was lost down a sewer.

Donatello is troubled by the revelation that the Turtles were merely an accident, convinced there must be more to their origin that what Professor Perry is telling them. Splinter offers words of wisdom, telling his son to not “confuse the spectre of [their] origin with [their] present worth”, adding that “the search for a beginning rarely has so easy an end”.

Shredder unleashes Tokka and Rahzar on the streets of New York, encouraging them to engage in general mayhem and destruction as a means of getting to the Turtles. The next day, April reports on the resulting wreckage for Channel 3; in a call-back to the first movie she corners Chief Sterns, who goes out of his way to not directly address the issue of the two mutants and refuses to do anything about them. It soon dawns on April that only the Turtles will be able to stop Tokka and Rahzar. After concluding her broadcast April is pulled into a nearby alley by a group of Foot Soldiers, one of whom removes his mask to reveal his identity as her trainee. Freddy declares that he has a “message” from Shredder for the Turtles. Later, April is seen meeting up with the Turtles in their new home, where she relays what she was told: that if the Turtles don’t appear that night at a construction site, Shredder will unleash Tokka and Rahzar in Central Park.

Professor Perry begins the task of creating an anti-mutagen that will revert Tokka and Rahzar back to their original forms, the Turtles offering their assistance. (Along the way Mikey accidentally drops a slice of pizza into the mix, but keeps this quiet.) The team are surprised to learn that the final substance won’t take the form of a spray, but will be a liquid that the two mutants will need to consume for it to take effect. Enjoy this shot of the anti-mutagen in a Bart Simpson glass because this movie, for better or worse, is so 1991.

The Turtles arrive at the construction site carrying a box of donuts, soon finding themselves again face-to-face with Shredder and his army of ninjas. Wielding the remaining cannister of mutagen, Shreds tells the team that the substance which made them will now be the cause of their destruction, summoning Tokka and Rahzar. The green teens attempt to offer up the donuts as a peace offering, but the ruse falls apart when the ice cubes concealed within containing the anti-mutagen are tossed aside. Like in their prior encounter, the Turtles are hurled around, vastly overpowered by Shredder’s new mutants; soon the battle spills into a neighbouring nightclub.

Performing in the club is one Vanilla Ice – not portraying a fictional character, but rather himself - who to what I presume is the delight of the patrons briefly pauses his set to watch in astonishment as the Ninja Turtles do battle with their oversized opponents. After the music begins playing again Ice launches into a freestyle rap about the events unfolding in front of him. Meanwhile Perry meets up with Donatello and notes that the portions of the anti-mutagen ingested by Tokka and Rahzar aren’t working as intended, the excessive consumption of CO2 making them burp profusely. Donatello suggests a further dose might act as a catalyst for the anti-mutagen, picking up a nearby fire extinguisher.

While all this is unfolding, Keno is meditating with Splinter, but can’t contain his frustration at having to stay behind while the Turtles have their big confrontation. The team’s sensei is insistent that taking on Shredder is a job only his students are suited for, but the delivery boy won’t listen and makes his exit. This all feels tacked on; Keno had already made the mistake of getting into trouble with Raphael earlier, for him to need to learn this lesson a second time comes across as if the writers are struggling to find a way to keep him involved.

As Vanilla Ice repeats his “GO NINJA GO” chorus, the Turtles use barrels to take Tokka and Rahzar off their feet, forcing them to ingest the contents of the fire extinguishers until both doze off. The team take on further waves of Foot Soldiers as “Ninja Rap” continues; after defeating their foes the green teens get in on the dance routine themselves, ultimately joining Ice on stage in perhaps one of the most notorious scenes in TMNT history.

This moment that will live in infamy is mercifully interrupted, and I don’t think I’ve ever been so glad to see the Shredder in my life. Still wielding the TGRI cannister, he promises to produce further mutants, over and over again in future movies until this series becomes unprofitable – though not exactly in those words – until Keno intervenes, kicking the container out of the masked villain’s hand. Shreds attempts to rebound by taking a club-goer hostage, threatening to transform her using a small test tube also containing some of the mutagen. The Turtles use the instruments from Vanilla Ice’s band (???) to create a sound loud enough that it blows a nearby speaker, the resulting explosion sending the villain flying through a wall. On their way out, the team note that Tokka and Rahzar have reverted to their original forms.

In a dockside area outside the nightclub the Turtles peer into the water, seeing no sign of their old foe. Rejoicing and cowabunga-ing follows but this turns out to be highly premature: Oroku Saki’s hand bursts through the structure of the pier ahead of a final encounter. Having consumed the contents of the test tube, he’s grown into what Donatello dubs a “Super Shredder”. Soon the Turtles find themselves beneath the pier, watching as the oversized villain wrecks everything in sight. Leonardo is briefly manhandled by the mutated foe, but instructs his team to remember the importance for ninjas of working within the confines of their environment; they are, after all, turtles, and so as the remnants of the pier crush Super Shredder, they dive out into the water nearby, safely re-emerging moments later. The group watch as, for the third time in this movie, Shredder’s hand shoots out of the ground, suggesting there’s still more fight in him, but he can’t cling on any longer, and finally passes away, for really reals this time.

April is seen reading a thank-you note to the Turtles from Professor Perry on the news as the Turtles return to their subway home. Presumably some time has passed since the battle with Shredder as Splinter quizzes the team about their actions, wondering if they were seen during the battle; when they insist they kept a low profile, he produces a copy of the Daily News with a full-page photograph of them on the front page, accompanied by the headline “NINJA RAP IS BORN!”; a second, smaller headline reads “DOCK DEMOLISHED OVERNIGHT”.

The first Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles movie was highly regarded even at the time, and its reputation has only grown in the three decades that have followed; it was and is a truly great comic book adaptation, one that’s aged remarkably well given that it was produced on a small budget. None of this can be said of The Secret of the Ooze, which is by no means a bad movie – at least in my estimation – but which never rises above being merely enjoyable. To go from great to kinda sorta okay still represents a decline, and it’s not hard to see why. TMNT II is burdened by the sheer size of the Turtles machine as it was in the second half of 1990, the demands from different parties insistent on shaping the future direction of this property too great, the need to have a second movie out in the wild while there was still money to be made taking precedence over crafting a coherent movie experience. Along the way the losses accumulated from the first film continued to build, some out of anyone’s control but others self-inflicted: Steve Barron, Judith Hoag, Elias Koteas and Corey Feldman are all gone and their respective replacements can only do so much. Perhaps the biggest loss of all, however, is the first movie’s ability to strike a balance in tone between the earnestness of the Mirage comics and the tomfoolery of the Fred Wolf cartoon. Now, only the tomfoolery remains. TMNT II revels in the worst impulses of the 1987 cartoon, and I say that as someone who’s plainly a huge fan of the MWS Turtles. A decision was made to alienate the older audience who embraced the first movie, the wishes of licensees and parental groups clearly taking precedence. It’s regrettable.

Speaking of regrettable decisions, I’m sure that in late 1990 shoehorning Vanilla Ice into the climax of this movie made a lot of sense. The first film benefitted from having MC Hammer’s “This Is What We Do” on its soundtrack months before “U Can’t Touch This” blew up in the summer, and no doubt his newfound name recognition helped shift additional copies of the tie-in album well into the autumn. Here, again, we see the machinations of TMNT Incorporated at work: given the enormous success of “Ice Ice Baby” in the closing months of the year, why not take things a step further and insert Hammer’s new rival into the sequel? We can laugh about it now – in 2023 the corniness of “Ninja Rap” and the visual of the Turtles cavorting with the rapper feels like a joke we’re all in on – but all of this was assuredly a misfire. By the time the movie landed in US cinemas in the spring of 1991 it was clear that Ice’s appeal was limited to his initial hit; by the summer, when TMNT II received its UK release, he was a walking punchline. And so, Ice’s prominence in the marketing materials for this movie comes across as a major blunder: an association that, with their own popularity entering the beginnings of its downswing, the Turtles didn’t need.

For the faithful, however – the legions of kids who had followed the green team on TV for years at this point – this movie’s failings would have extended far beyond the presence of one Robert Van Winkle. The first film was notable in the elements it chose to adapt from the 1987 series, but also in what it elected to omit: the Technodrome, Krang, and the Channel 6 crew were all curiously absent, and it seemed inevitable that at least some of these would be held over for the follow-up. More than any of these, however, there were two obvious players for the Turtles to encounter in a hypothetical sequel: Rocksteady and Bebop.

It’s timely that we should discuss the thorny issue of Shredder’s mutant henchmen here, a week after covering their final TV appearance in the cartoon’s eighth season; while reflecting on their role within the show I wrote about how critical they were in establishing the 1987 show’s comedic credentials, even more than the Turtles themselves. In this respect, they represent everything that differentiates the Fred Wolf TMNT from the other incarnations of the property.

It wasn’t supposed to be like this. Over the years, Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird’s position regarding Rocksteady and Bebop seems to have hovered somewhere between low-key resentment and unreserved loathing. While these characters were created early on as part of the development of TMNT into an action figure property, it’s clear that the versions of the duo which eventually made it to air were in line with the vision of David Wise and the Murakami-Wolf-Swenson studio. When that vision turned out to be incredibly profitable – not just Rocksteady and Bebop, but the pizza gags, the catchphrases, April as a reporter and everything else that had been introduced as part of the transition of the Turtles to TV and as a toy line – a situation arose where the various parties involved each felt they were responsible for the elements that had made it all possible.

This all came to a head in 1990, as the worldwide popularity of the Turtles reached its apex. The Turtlethon entries for that year’s episodes tell the story of the ill-feeling brewing between two primary camps: Mirage Studios, whose artists by that point felt that the supporting characters they had created such as Leatherhead had been mishandled in the transition to animation, and MWS, whose zanier Turtles had been what introduced the vast majority of kids to the property. Eastman & Laird had put their foot down before – nixing outlandish ideas such as an early proposal for the post-season one Turtles to have them move into the Technodrome, where they would have resided with a no-longer-villainous Baxter Stockman – but it was in season four where we really saw the fallout of these creative differences, with “Ray” and Mona Lisa the end result, the latter far more successful than the former.

It’s understandable, then, that Eastman & Laird were keen to keep MWS out of the loop as far as the live-action films went, preventing Fred Wolf and his studio from taking any potential credit (and profits) from their success. And so, for movie-goers, there would be no Dimension X, no Burne, no Irma, no Vernon, no (robotic) Foot Soldiers, and certainly no Rocksteady or Bebop. Evidently there was some push to include the mutant duo in the movie – possibly from Pressman himself and/or the studio – and so a compromise was reached. Yes, Shredder could have two creatures to do battle with the Turtles on his behalf, but they would need to be new creations, free of any association with the cartoon.

youtube

youtube

Taken in isolation, Tokka and Rahzar could be seen as merely a disappointment, a poor substitute: they are, in the worst possible way, Bebop and Rocksteady at Home, TMNT’s own fake Razor and Diesel (an ironic comparison, given that the real Diesel played Super Shredder in this very movie). Like Vanilla Ice and all the casting changes, they represent another weight around this film’s neck. But they infuriate me in a way far greater than any of TMNT II’s other failings after examining how the film was marketed. Promotional materials such as commercials from the time of The Secret of the Ooze’s release go out of their way to not show Tokka and Rahzar; to hint at the idea that the Turtles will fight two new beastly enemies, leaving viewers to connect the dots themselves. Even within the movie itself, the visual of a grey, beastly hand and a brown, furry one prior to the full reveal of the mutants plays upon our expectations that Rocksteady and Bebop are waiting behind the scrap heap veil. When that turns out to not be the case it’s a giant middle finger to the audience, whose money has already been taken.

While I can understand Eastman & Laird’s desire to have the live-action movies remain an undiluted vision of what they intended the Turtles to be, the contempt displayed for the audience here – for children – is risible in my eyes. I’m giving Kevin and Peter the benefit of the doubt and assuming these were executive decisions made within the studio, given that the final product ended up hewing far closer to the cartoon anyway, something that by all accounts was the total opposite of what they themselves wanted; I don’t believe their disdain for Rocksteady and Bebop was so great that they orchestrated this deception to trick kids, but somebody involved with this film was clearly okay with it. To be clear, the secrecy surrounding these characters only went so far - they’re showcased in detail in the half-hour special on the making of the movie - but in the greater scheme of things there was definitely some sleight of hand at work here; if you should happen to think Rocksteady and Bebop will be in TMNT II, little in the pre-release marketing would convince you otherwise.

The greatest irony of all this is that Tokka and Rahzar would continue to hover around the periphery of the TMNT universe in the years that followed, but it was a surprise inclusion in season seven of the MWS cartoon that made something of them. “Dirk Savage – Mutant Hunter” was a terrific episode made better by appearances of the two mutants, re-interpreted as a duo whose friendship is so strong that when Tokka is captured, Rahzar can’t bear to be separated from him. And who was responsible for redeeming them? None other than David Wise, the same writer who helped craft Rocksteady and Bebop into the hapless henchmen whose buffoonery Eastman & Laird refused to sanction.

Today, many of the concepts created in The Secret of the Ooze remain a part of the fabric of TMNT: Tokka, Rahzar and Super Shredder all pop up on occasion in video games or as action figures. The film itself is fun fluff, the kind of thing you watch if it shows up on TV on some idle Saturday afternoon, and a representation of the exact moment where the bubble of Turtlemania burst, even if we didn’t realise it at the time. Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles III, the most derided film of the trilogy, would follow two years later. We’ll come back to that in a few weeks, but next time on Turtlethon we jump forward again in time to 1995, where the drastic reinvention of the green teens that took place the year prior somehow still hasn’t been enough: it’s out with Shredder and in with Lord Dregg as we learn the uncover the secrets of “The Unknown Ninja”.

#Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles#TMNT#TMNT II#1991#Turtlethon#The Secret Of The Ooze#Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II: The Secret of the Ooze#Tokka#Rahzar#Tokka and Rahzar#Vanilla Ice#Ninja Rap#90s films#1990s Films

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

I love that OC headcanon of yours! You got any more for your other OCs?

Well, sure! I have a few for my newest OC Betty, my New Yorker (Super Mario Bros. Movie OC):

1. She secretly has a mountain of stuffed animals but shoves them into the closet when her bandmates or the Mario Brothers come visit.

2. Despite her tough exterior, Betty is a softie at heart. She is always willing to help out a friend in need and has a soft spot for animals.

4. She has a wicked sense of humor and loves to make people laugh. She is known for her quick wit and sarcastic comments.

5. Regardless of her rockstar lifestyle, Betty is a deeply spiritual person. She meditates every morning and practices yoga to stay centered and focused.

7. She is a hopeless romantic, but she doesn't want to admit it. No matter how hard Mario and Luigi try to pester her about it.

8. She LOVES old-timey cartoons. Animaniacs is her favorite, but she occasionally watches Looney Toons.

9. She has a bad habit of starting fights. Whether it's bar fights, food fights, or just a normal fight. Any kind of fight you can think of, she's probably done it.

10. She has a huge criminal record. And yet, she's only been in jail a few times. She actually befriended the inmates there.

11. She is a total prankster. Her favorite prank is drawing on people's faces when they're asleep.

#thanks for the ask!#nintendoneko64#ask away#ask me anything#ask me stuff#oc#oc headcanons#super mario bros movie oc#smb oc#smb movie oc#super mario brothers oc#original character

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

EDITORIAL ILLUSTRATION IDEAS AND CONCEPTS

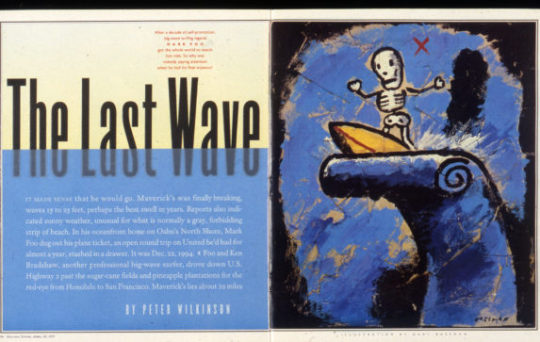

Gary Baseman

(top to bottom, left to right: The New Yorker (may 13 2002), New York Times For Kids (march 26 2023), The Atlantic (august 1991), Fast Company (August 2005), Fiona Apple, Rolling Stone (1999), Rolling Stone (1995)

Gary Baseman is an American artist known for his distinctive kitschy cartoony art style, inspired by Hanna-Barbera and Looney Tunes his work embodies whimsy, childishness and innocence.

Baseman’s art style is incredibly visually distinct, utilising traditional image making techniques such as oil pastel, watercolour and acrylic, his art possesses an overlying grittiness, contrasting with the usual naive and charming visuals.

Within Baseman’s work, he tends to put a lot of emphasis on colour, utilising bright yet de-saturated colour schemes, achieving a sickly-sweet aged affect, honing into and intensifying the aspects of its vintage children’s book and cartoon inspirations.

This is also seen within Baseman’s character design and expressions, taking inspiration from cartoons, his expressions and posing are heightened to an absurd degree, having characters bend and pose as if they’re made of rubber, this is especially noticeable for the cover he illustrated for The Atlantic, the exaggerated body language and posing helps visualise that the subjects are rushing forward from the left side of the page in excitement for the weekend, all holding different objects related to activities they’re excited to partake in over the days. The composition as well within this piece is strong, as it frames the people as rushing towards the right, drawing the readers eye to flip the page and read the contents of the issue.

Within Baseman’s editorial work, he makes use of his naïve art style into light-hearted commentary, making serious situations more childish for satirical affect. An example of this is his cover made for Fast Company in which the cover story talks about the frustration against HR Departments, Baseman depicts HR as a young girl throwing a tantrum and brutally abusing and breaking her toys. This is obviously meant to portray HR as being inescapable, ruthless and unthinking when it comes to employee wellbeing and creativity, stunting employees’ ability to advance within their job.

Another example is the illustration Baseman did to accompany Peter Wilkinsons article ‘The Last Wave’ for Rolling Stone. This article detailed Mark Foo’s, a famous surfer, death by drowning at a surfing competition and the controversy surrounding it. The illustration Baseman made to complement this article shows a dark oil pastel illustration depicting a skeleton riding a dangerously tall wave, clearly illustrating how this wave was fatal to Foo’s life.

0 notes

Text

It's ugly, but to me at least it's also kinda endearing? It's kinda like how some dog breeds are ugly but not to the point where they genuinely look gross and more like in an endearing kinda way. Like, buildings like this is something you'd see either drawn by a 5 year old who doesn't know how to draw for shit or in old cartoons that wanna simplify it. Take for example the Twin Towers that were a part of the original WTC.

New Yorkers used to fucking hate the damn things, but with time they just stuck out in NYC's complex skyline as these two giant filing cabinet shaped titans that grazed the skyline for nearly 30 years. It wasn't pretty, but they had a weird charm to them. We need to bring back "filing cabinet" type skyscrapers again. Sure they may never look nice, but I'd say they're definitely unique.

Apparently the 1300 ft trash chute in 432 Park Avenue does not have any breaks or offsets in it to slow down the garbage so stuff thrown away at the top floors easily reaches terminal velocity and sounds like bombs going off when it hits the bottom.

26K notes

·

View notes

Text

Dan Misdea.

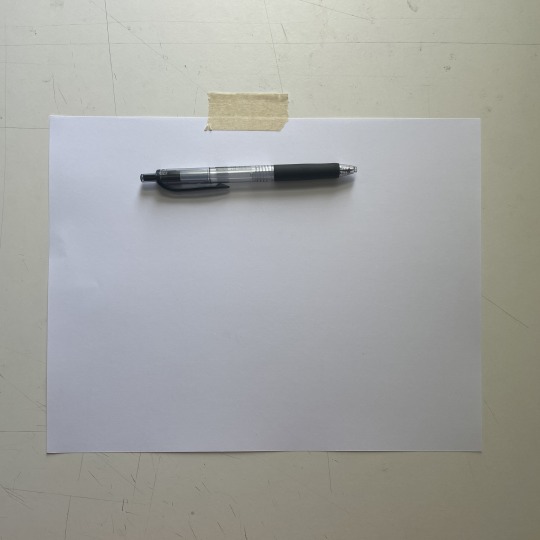

Editor's Note: Be sure to check out Dan's new children's book, The Light Inside, available this week!

Bio: I've been contributing cartoons to The New Yorker since 2021. My work has also appeared in Air Mail, Narrative, The Times, Weekly Humorist, The Golfer's Journal, and a few other publications. My first children's book, The Light Inside, is available now.

Find this print here!

Tools of choice: I brainstorm ideas on printer paper with a .38 Uni-ball Signo RT and sketch the roughs I submit to The New Yorker on my iPad.

For now, my finishes go on Bristol vellum (Canson) with graphic liners (Rotring), oil-based colored pencils (Lyra), and various blenders. Occasionally, I'll use a solvent to blend and fill larger areas, or an ink wash if the drawing calls for it. I used to finish all of my cartoons digitally, so there has been some trial and error in finding the right tools.

There’s no specific reason why I switched to traditional tools. It sounds corny, but it was just something I felt the urge to explore. I feel a stronger connection to my work now, and the creative process is way more enjoyable for me.

All materials are subject to change at any moment.

Tools I wish I could use better: My golf clubs.

Tricks: Allow yourself to experiment and remember to have fun.

Tools I wish existed: A magic tool that could scan my work and edit it to perfection all at once.

Misc: If you’re an aspiring cartoonist, I would suggest reading A LOT of cartoons. Try to notice how the pros compose their drawings and craft their captions. You’ll eventually gravitate towards certain styles and voices, and I think that will help shape your own values as a cartoonist.

Links:

Website: https://danmisdea.com

Instagram: @dan_misdea

The Light Inside: Buy my children's book, The Light Inside, here

Curated Cartoons: Buy my original cartoons here

-----

If you enjoy this blog, and would like to contribute to labor and maintenance costs, there is a Patreon, and if you’d like to buy me a cup of coffee, there is a Ko-Fi account as well! I do this blog for free because accessible arts education is important to me, and your support helps a lot! You can also find more posts about art supplies on Case’s Instagram and Twitter! Thank you!

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Carton of French Fries Walks Into a Bar

New Yorker cartoon by Schwartz. This is the latest specimen in The New Yorker’s cartoon caption contest that has run for centuries. I’ve never come close to inventing a caption for an entry in this feature, but it fascinates me for what it often shows of how much of a good cartoon’s payload is packed into the drawing itself. Adding words can feel like gilding the lily. Not that I discourage the…

0 notes

Text

Silence reigns supreme in my reich

No don (except me) doth trumpet within the aborted barren reach of freedoms within expansive realm, I annexed courtesy manifest destiny, which peoples now inhabiting said jurisdiction circumscribed by following coordinates - Latitude: 40° 16' 22.20" N Longitude: -75° 29' 29.39" W and for better or worse

must abide by decrees promulgation declared today May 21st, 2024, whence Poet of Perkiomen Valley issues proclamation, regarding any living person paying blind obedience lest posse comitatus act enforced otherwise Herr Harris will bring to fore active duty personnel

to "execute the laws"; however, there be disagreement over whether this language may apply to troops used in an advisory, support, disaster response, or other homeland defense role, as opposed to domestic law enforcement to challenge aforesaid claims which forthwith ownership of said territory

foremost allows, enables and provides yours truly to enact legislation, and especially restitution of comstock act predicated upon due diligence guaranteeing appropriation of all and every rights affecting master and slave

linkedin within said domain. Welcome to the dictatorship (er rather presidency)

of Putin diehard adherent.

Matter of fact, a favorite author of mine crafted the following words of inspiration,

which evocation will help shed figurative light on caricatures of terror reign as forty fifth president targeted by political cartoonists, but struggled to come up with an image that sticks. In october 2016, Vanity Fair

made a video of four of its cartoonists—

Edward Sorel, Steve Brodner,

Philip Burke, and Robert Risko—

drawing Donald Trump.

They clearly enjoyed themselves,

exploring every aspect of his physique:

his “girth,” the fact that

“there’s so much of him” (Burke);

the hair that “essentially closely a beret

flipped forward on his head” (Risko);

the eyes that show “greed, disdain” (Burke);

the “marvelously rat like” nose (Brodner);

the mouth a “sphincter muscle” (Risko);

the “sleazy” look (Sorel);

the facial features that resemble

“piss holes in the snow” (Brodner). And now? How have artists and cartoonists

dealt with Trump since he became president?

We’ve seen cartoons of the orange

potus smooching Vladimir Putin

and groping the Statue of Liberty.

We’ve seen him drawn (by Barry Blitt

in The New Yorker) as a fat-assed golfer

driving balls into the White House.

We’ve seen him caricatured (by Pat Oliphant

for The Nib) as a preening SS officer

being heiled by Steve Bannon.

We’ve seen him portrayed

(by Signe Wilkinson of the Philadelphia

Daily News) linking arms

with a Confederate and a Nazi.

We’ve seen him depicted

(by Mike Luckovich of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution)

as Jabba the Hutt, holding Lady Liberty in chains. We’ve seen him represented (by Matt Wuerker in Politico) as a kook in a straitjacket. We’ve seen him rendered (by Ann Telnaes of The Washington Post) as a red-faced fathead sitting on the toilet while he plots to pull out of the Paris climate accord.

Putin (also fell prey

to his fair share of cartoonists) not only as Vlad the Impaler reincarnate (a notion in mind of at least one writer), but also various and sundry other manifestations.

The self styled ruthless thug classified as a voivode (prince) of Wallachia (part of modern Romania).

Surrounded by enemies that included the Hungarians, the Ottomans, his younger brother, and Walachian nobility, Vlad employed extremely cruel gruesome measures to inspire fear in those who opposed him.

He earned his nickname by impaling his enemies on stakes.

No argument Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin equals and invariably will outrank Vlad the Impaler the second son of Vlad Dracul who became ruler of Wallachia in 1436.

Impossible mission to comprehend propensity exhibiting characteristics linkedin as impish, hellish, ghoulish... fiend whereby pathological pretensions besotted (punch drunk with delight) to incinerate, eradicate, annihilate, essentially to deplorably, heinously, loathingly... interblend all manner of atrocious, deleterious, insidious, opprobrious, vicious... lend ding his own vainglorious trademark to offend

Homo sapiens who strive toward repairing ruptures versus to rend usurpation of life, liberty and continuity of civilization to upend.

Worst nightmare scenario unfolding before our collective eyes Ukraine suffers blitzkrieg Russian soldiers devastatingly carpet bomb major metropolitan areas civilian population suffers major loss of innocent lives linkedin with accompanied psychological fallout, especially affecting babies, children and youth.

All commands issued by autocratic monster probably housed within secure bunker, meanwhile countless thousands or millions of battle fatigued people hunker among ruins gingerly negotiating their way thru rubble analogous to spelunker.

Though yours truly removed (think physically), where chaos and pandemonium run amuck and terror unruly, overt rampant upheaval plagues long established generations of Slavic peoples, this commonplace American experiences vicarious grief, when tragedy viewed online and/or television heart wrenching images also evoke anger being linkedin to most abominable, horrible, reprehensible, creatures that roamed the terrestrial firm

since time immemorial.

Major war crimes against humanity necessitate urgent punishment, if in fact such a global entity exists to condemn and convict the incontestable tyrant, yet never in the annals of twenty first century geopolitical webbed zeitgeist

did self anointed sovereign

access nuclear weapons

to obliterate fellow Earthlings.

0 notes

Text

Maybe An Artist: A Graphic Memoir

Maybe An Artist is a graphic novel memoir written and illustrated by Liz Montague - one of the first Black female cartoonists to be published in the New Yorker. The target age group for this graphic novel is young adults in grades 7-12.

This GN memoir is told from Montague’s point of view as an adult as she reflects on different stages of her life, beginning with her childhood up to adulthood. The illustrations that were published in the New Yorker are what led Montague to write this memoir. Liz touches on important themes throughout this memoir such as growing up as a Black girl in a predominantly white town. Trying to find her voice as an artist while navigating her severe dyslexia, and finding confidence to pursue her career.

I don’t usually read graphic novels but this one was displayed in the teen room at my local library. I initially picked it up because of the cover, but when I discovered that it was also a memoir I was immediately interested. After reading about the author, I felt a sense of comfort because I found a lot of similarities between her experiences as a young adult and my own. For example, I grew up with a learning disability like Liz and I remember feeling a sense of confusion and frustration when doing my schoolwork. When it comes to learning disabilities, I do think that it’s difficult to find representation in stories, and for authors to capture that feeling of frustration that so many young adults experience. I felt that Liz did well in representing those emotions through her art.

For this review, I will be evaluating illustrations, format, and Design & Layout.

Illustrations: The illustrations in this Graphic Novel have a bubbly and cartoonish style to them. The drawings are followed with simple text making it easy for readers to follow along. One observation I made was that the story begins when Liz is five years old and transitions to her middle school, high school, and then adult years. However, her features hardly change and she appears to be the same age throughout the entirety of the novel even though she’s not. I do think that overall the author did a good job with the illustrations because it’s easy for the reader to see the emotions that are being conveyed. Most of this story focuses on Liz and her academic and personal struggles and it’s easy to identify when she’s in the classroom, her room, or at her job. Overall, I enjoyed the author's style and color choices.

Format: As I mentioned, graphic novels are not my first choice when it comes to choosing books. I read the physical copy of Maybe An Artist and enjoyed going through the pages. It was a fun experience getting to see all of the details the author put into illustrating her personal story. I also appreciated seeing Black female representation and inclusivity in an industry and genre that is overwhelmingly dominated by men. I believe that if I had listened to this story as an audiobook or read it as an ebook I would not have had the same experience. I believe that graphic novels are meant to be read in their physical form rather than digital.

Design & Layout: I decided to review this element because what drew me to this book was the cover and the colors that were used. The two main colors on the cover are a light teal and the title stands out in a peachy/orange color. The most eye-catching element of the cover is the triple self-portrait of the author. I think this worked well because the cartoon style on the cover as well as the colors are consistent with what's inside of the book. Moreover, I enjoyed how the author alternated between individual and multiple panels throughout the novel. The position of the comics and the placement of the text were also well executed and made it easy to follow the story. Overall, I think the author chose the perfect font, style, and colors for the intended audience.

References:

Montague, L. (2022). Maybe an artist. Random House Studio.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Laughing Redhead and More