#how many ways can i explain standard score and percentiles

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Language Update

Cantonese

Had my first Cantonese lesson on italki today! I am at A0 for Cantonese but I think I felt pretty good about the first lesson. My tutor was a little bit disorganized at first but eventually found their rhythm and I felt like I learned a lot. They were super cognizant of my reasons for learning Cantonese and gave me excellent, relevant examples. They also provided me with excellent resources. After just this one session, I am starting to get the hang of basic sentence structure for declaratives and interrogatives. They let me know my tones are pretty accurate which is great because I feel like I am a little tone-deaf and it's a big concern of mine. I'm hoping tutoring will give me more structure and intensify my studying.

Cantonese pronunciation (tones and phonemes): https://www.polyu.edu.hk/cbs/pronunciation/cantonese/intro

Cantonese top 100 verbs: https://www.cantoneseclass101.com/blog/2020/08/25/cantonese-verbs/

Persian

These last few weeks have been a little bit slow. Still doing the On/Off method. It is working to alleviate the stress of feeling like I'm not doing enough. I'm inconsistently going through the motions, but don't feel like I'm absorbing or progressing. I do feel that some things come a little bit more naturally to me like reading and thinking in Persian.

French

Currently reading Les Impatientes by Djaili Amadou Amal after being tempted to join a francophone reading book club in my area. I missed their meeting in May and this is the book from that meeting. Jury's still out on whether I will join the bookclub because of my rampant imposter syndrome and self-diagnosed performance/cultural anxiety as a first generation francophone in a non-francophone country.

I still keep up with writing in French by dedicating at least one entry per day in my journal.

Spanish

I live and breathe this language every day, but am trying to increase my reading (still, *sigh*). Like French, I dedicate at least 1 day for writing.

Portuguese

I stopped studying Portuguese to make room for Cantonese, but am highly delusional and have been thinking of sneaking in some Portuguese to my already scattered and inconsistent routine.

Overall, though, my progress has been super super slow/stagnant. I really have not been focused or consistent with any of my languages (other than obligatory Spanish). These last few weeks have been blunder after blunder and very stressful. Even just today, I had a dreaded phone call with some parents at work today. I had to stand my ground and not let them bully me into giving into their *demands*. I already have given so much because I notice how much they are concerned and, clinically, I also notice the concern (albeit, not as intensely as they do from a clinical POV). I tried my best to explain and answer questions but after a while just ended up getting sucked into a vicious circle of a conversation about test scores with them who were hearing me but absolutely not fucking listening, I sort of got curt, interrupted them, and repeated my point kind of cruelly. And our mediator had to step in lol.

But, even with the stress in my professional life, I find a way to squeeze in even just a crumb of language learning in my day. If I wait for everything to blow over, I would be waiting forever. This is teaching me to let go of perfectionism and letting things happen as they happen.

#language update#personal#how many ways can i explain standard score and percentiles#sorry i don't make the damn bell curve!!!#but i also could have been a little bit more empathetic

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, I am very new to DnD and I would really like some tips on how to play and roll for certain things (Im not too good with examples) etc. etc.

Howdy! Mod Nate here coming at you with some Tips for Beginners. There’s a hell of a lot to cover that I cannot fit into one post (because, let’s be honest, that would be a nightmare), but I will try my best. So, without further ado, hold onto your butts.

The Three R’s

I find there are three main aspects to remember (and master!) when starting off in DnD or other such TTRPG’s. You can sort them into three categories:

Rules,

Rol(l/e)s, and

Roleplaying

Of course there are heaps of other things to consider in game, but for a beginner, it can get overwhelming very quickly, so we’ll just stick to the Three R’s for now.

Rules

What better thing for a game than rules! The first thing you hopefully would have done if you were gearing up for your first game is to get your hands on a Player’s Handbook (For DnD 5e), or your RPG’s respective rulebook. Hobby stores, book stores, libraries, even video game shops might stock a physical copy of our favourite WotC volumes, but you can also secure them online wherever you may find them.

Once you have your grubby little goblin hands on a handbook, give it to a friend, and have them read it to you. If that gets too boring, have them explain the rules in detail - you’ll need a pen and a notebook! If that is too time-consuming or - more likely - you don’t actually have any friends, you’ll have to settle for a hurried and often last-minute explanation of the core mechanics of the game, the finer details of which will be left unaddressed until you get your creative spirit crushed by your mean Dungeon Master, or local rules lawyer.

(Remember kids, if you aren’t sure of where to locate one of these “rules lawyers”, simply talk out loud about your homebrew weapon or Pathfinder game, and they will be sure to find you!)

In this fabled Player’s Handbook you will find a fun breakdown and walkthrough of the game’s races, classes, and backgrounds, all of which you will need to read through several times and then immediately forget. Only after you have asked yourself “Which Bard School is going to make Sildaar Hallwinter not a steaming pile of crap?” for the fifth time in 10 minutes, can you move on to “equipment” and “rules”. Make sure to read these thoroughly, because you’ll learn them pretty quickly after your party’s Paladin once again forgets how many d10s to roll. It’s two, Derek. You asked the exact same question last round.

Idiot.

Rol(l/e)s

Once you manage to wrap your head around the rules, you get to the meat of the sandwich - rol(l/e)s. Whoever came up with this idiotic word hybrid (me) needs to report to their editor (also me) and get his ass whooped (still me).

Now, I know you’ve gotten this far and thought “Wait, Nate, that may have rhymed but you haven’t actually given any tips yet?!??!?!?!!/1!?!?!?!?1?!???????????”. To that, I say yes (or no?), I have(n’t?) given you tips for how to play and roll for certain things, because the biggest tip I have for you is coming right up.

Wait for it.

You cannot build a dragon’s tower without strong foundations.

Meaning: Only once you have “mastered” the rules and basics of roleplaying (and rolling!) will you be able to spread your beautiful dragon wings and soar as a damn good DnD player. This doesn’t necessarily mean that you will have to learn and remember every single mechanic or rule in the book! Because that would be a nightmare and if you can do it, you will be God. No questions asked. But hey! People make mistakes, or remember things wrong, or guess incorrectly, or even make it up as they go along. Having the handbook or Dungeon Master’s Guide on hand for these occasions will save everyone’s sanity at least once, but knowing when to draw the line between fairness and fun will make everyone’s play a whole lot better.

So! Now that you’ve become God, rolling and role-ing (not a word) are your new best friends. And you know who makes the best friends? DICE! Just google it and have fun, kids, but remember that you have to eat and sleep somewhere warm and cozy tonight, so try not to build your hoard of shiny forbidden snacks too quickly, now. All you will need for starters is your standard 7-dice set: d4, d6, d8, d10*, d12, and d20.

*The d10 often comes in pairs to act as a percentile dice. The die with the ten’s (00, 10, 20, 30, etc.) will act as the ten’s place, and the other die will act as the one’s place. So, if you roll a 60 and a 9, you get a really funny number. If you roll a 00 and a 0, that’s 100! If you roll a 00 and a 1, however, that’s a 1. You die in game and you die in real life. Goodbye.

The handbook will tell you all the dice you will need to roll in order to both run the game, and make your character! That’s right! Maths begins even before the game does. Even Death themself cannot escape the point-buy system. Just submit.

Stats are fun.

What do they mean? What do they do? Who even knows what Constitution does?! I certainly don’t! But that’s where you’re in luck, bucko.

This post is already long enough without getting to the good stuff, so I’ll keep it simple.

Strength - a measure of how well you can do stuff with your muscles. Skills like Athletics (aaaaaaand nope just athletics, huh, really? No fish-lifting skill? Huh? Cowards) will benefit from having some damn good muscles. Also you can stab stuff real good.

Dexterity - a measure of how deft, nimble, and stealthy one can be. Contributes to skills like Acrobatics and Stealth, unsurprisingly. If you can move good, you can groove good. I’d add a skill for dancing if I were you, WotC.

Constitution - I lied before when I said I had no idea what constitution does, but it was only partly a joke. Constitution contributes to skills like not dying, staying alive, and stopping being dead. Sometimes it determines how much health you have. Sometimes it means you can drink an entire frog. Don’t ask.

Intelligence - Are you a smart cookie? Can you learn languages fluently in a short span of time? Can you destroy scores of defenceless troops with a single pillar of flame? Can you read? Are you kept awake at night by their screams? Intelligence makes you good (or not) at skills like History, Religion, Arcana, and being a nerd. Oh wait. No one is good at being a nerd. Sorry nerdlord. Also, if your intelligence is under 10, you can’t read! Just like me.

Wisdom - Not the smartest cookie in the shed? Like to eat leaves? You and me both, kid! Wisdom is a measure of your STREET SMARTS! so you can throw those nasty pervert kobolds off their rhythm. Unfortunately, starting equipment does not include a money clip. It makes you good at eating dirt and walking through forests and stuff. Also I think you can pet dogs really well?

Charisma - If you’ve ever played a bard, you would know what this is. If you haven’t played a bard, it’s not too late! Quick! Choose a Warlock or a Cleric if you want a Charisma based build! Choose the entertainer background if you must! -sigh- but if you insist, charisma is a measure of how easily you can quite literally charm the pants off a dragon. Also, sometimes you can roast people really well?

Having high skills is all fine and dandy, but the next tier of DnD player character power is owning your low skills. Have low constitution? Your tiefling is sickly or has a weak stomach! Low intelligence? Your character can’t read or write! Low charisma? You cause every single npc interaction to end with you being punched in the face. There is colour and interest in every aspect of your character, so make sure to let your character sheet represent your character as well as you can!

But how do you determine these stats?

Looking in your class description, you will see under the ‘Quick Build’ section the recommended stat scores, backgrounds and/or spells for that character. These are NOT mandatory, but I find them to be a helpful guideline for how to keep your character functional and, well, alive. Stat scores themselves can be determined a few different ways: Point-buy (I have no idea how this works but it looks like a lot of maths and that’s homophobic, so); Cascading, and rolling.

Cascading (or at least that’s my name for it, I have no other way to describe it) is where you take the values 15, 14, 13, 12, 10, and 8 and assign each to one of your stats. For example, before adding racial stat modifiers, I could assign my barbarian’s stats as follows:

STR: 15, DEX: 13, CON: 14, INT: 8, WIS: 10, CHA: 12.

I may have a character-based reason for assigning my barbarian a relatively adequate Charisma score. Maybe he was a particularly intimidating character, or perhaps his iron-will makes his Constitution a 14. Maybe he likes to dance. You could have a particularly burly mage with a strength score of 15, just because you feel like it. Maybe your cleric is part of team sweet-flips? Or your monk could study tomes night and day to get her Intelligence to a lofty 17 points post-modifiers. Balancing stat scores so that you don’t die is awesome, but having a change to shout “YOU DO NOT SEE GROG!” and win 9 times out of 10? Priceless.

Rolling your stats is perhaps the most widely-used way to determine stats, but to be safe, ask your DM (or get crafty if you’re the DM!) about their preferred method. It’s pretty simple: roll 4d6 (the six-sided dice four times), noting down each individual roll. After four rolls, you cross out the lowest roll, and add the remaining three. Repeat five more times and you have some good good stats, bro! Don’t forget to add your racial stat modifiers before you assign your stat scores!

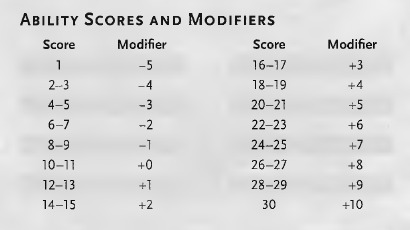

Modifiers seem pretty confusing as a newbie, but there is a handy table in the PHB to help you keep track. Alternatively, you could subtract 10 from your score, and then half what you have left, making sure to round down! A score of 19 would have a modifier of +4 (19 - 10 = 9/2 = 4.5 ≈ 4, rounding down). A score of 8 would have a modifier of -1 (8 - 10 = -2/2 = -1). Pretty simple, right?

So now I think I can finally address whatever the F*$# I mean by ‘Roles’. What the heck is a role? Do you mean roleplaying? No, dear reader, I do not. A ‘role’ is what I like to call your position in the party. Because yes, on the unlikely occasion that you do manage to wrangle a group of people willing (or able) to play DnD with you, you still have to play with other kids, Derek. That means that the typical balancing applies. You cannot just have a 7-person party filled entirely by bards. Or bees. Though I would prefer the bees. Who would want 7 bards? That sounds like the start of a bad joke.

A good rule of thumb is to make sure you have enough bases covered in the traditional party makeup that you won’t die immediately, but you also don’t have to deal with 7 goddamn bards, Derek, I swear to God-

You’ll want someone to hit stuff, someone to get hit, someone to help those who get hit, and someone to hit things when you don’t want to get hit. This could be solved any number of ways. Get creative, go hog wild. But not buck wild, Derek. I will not have the “Seven Buskateers” at my table again, do you hear me?!

This brings us to the finale. I’ve been writing this post for half an hour, and we’re finally getting to the good stuff. Thanks for stick with me so far. How about dropping your favourite stardew valley bachelor/ette down in the replies if you’ve read this far? Mine’s Elliot, because he’s beautiful and I love him, just like I love you. :3

Roleplaying!

It’s in the title! The very mechanics of the game! So, the question you’re asking me is: “Nate, how the Flippity Doo Daa do you roleplay?????????”

And I reply, “How are you making those noises with your mouth? Where am I?! Who are you? Why can I hear each individual question mark even though they shouldn’t have a place in the mortal coil? What are you?!”

And then I tell you about my favourite thing to tell my own players.

The easiest character to play is one that exists. So? What does that mean???

It means that YOU, my dead, dear nerd, can’t just pull a self-insert every single dang game, Damn it Derek! No one LIKES YOU! GO HOME! You have this opportunity to think of a fun, unique concept, and roll with it. So, how can you create the next Taako, or Nott, or Yashee’rak or Caduceus?

If you have a concept to work from, that’s great! If not, start from the ground up. Who is your character? What are their likes, dislikes, loves, hates, loyalties, vendettas? I often like to establish both a backstory and a goal for them to accomplish, the simpler the better, to get you on the right track. Perhaps a Neverwinter begger wishes to open their own tea shop in Ba Sing Se? A cursed child of an angel and a demon takes it upon themself to avenge their brother’s death? A simple farm girl falls in love and follows her princess Buttercup across Faerûn? You name it!

Some good questions to ask yourself about your characters personality could also include:

What would they kill for?

What would they die for?

What would they watch someone else die for?

What are some rumours your party members would have heard about your character?

What would they think of your favourite meme?

How do they treat their mum? How would they treat your mum?

Do they have any recurring nightmares? Why?

Etc. Etc. Think of them as a real being, with thoughts and feelings and hopes and dreams and fears! The more detailed you can get in theory might help in the long run. If you find yourself deviating from these details, however, don’t sweat! That’s a character’s natural development and progression as a character! In fact, if things don’t change as you play, you might have to have a look at your play style. Loosen up. No one is one emotion their entire lives. Characters lie! They hide things and change details and cheat and steal! But they also act kindly, even randomly, and change and grow. Encourage that. Let them grow. They (and your party members!) will thank you for it!

I think that’s all I have in me for now, and oh man there are so many more things I could mention. DMing in itself will have to wait for another day, of course, but I hope this helped! I’m going to die now.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

HP Spectre x360 (Kaby Lake G) Review

So, about 2 weeks ago I got my HP Spectre x360 with the i7-8705G processor, and I've decided to a little review on it, just for fun. My model has a 4K touchscreen display, 12 GB of DDR4 2400 (so dual channel memory doesn't work quite correctly), the i7-8705G (4 CPU cores, 4 GB of HBM2, and 20 CUs), and a 256 GB NVME SSD from Samsung, the one that comes with the laptop. I'm mostly going to be testing performance but I will touch on all aspects of the laptop.

Overview

The HP Spectre x360 is a 15 inch laptop that launched a couple of months ago at $1300-$1500; HP has sales pretty frequently so if you're lucky you can get this for about $1300 like I did. It comes with only one option for Kaby Lake G, the i7-8705G. You can configure the RAM from 8 to 16 GB and configure the SSD from 256 to 2 TB. The screen only comes in at 4K. The Spectre also includes a fingerprint scanner and a Windows Hello compatible webcam for quick sign in. IO is pretty good as well; HP includes one T3 port, one USB type C port, one USB 3.1 port, one HDMI port, a headphone jack, and an SD card reader. It can be charged either through its AC port or through the USB type C compatible ports, but only if you own one of HP's branded chargers. HP's software will reject anything that isn't from HP. Also, you can open up the Spectre (with some difficulty) and upgrade the RAM and SSD and even fiddle with the heatsink if you want. Finally, the Spectre is just under 20 mm in thickness and weighs about 4.6 pounds. Okay, with all that being said, let's get into it.

Chassis

The first thing you notice with a laptop is how it looks, and the Spectre looks and feels really good. It's very sturdy and feels very premium. I previously owned an HP Envy x360 15 inch, and I have to say it's actually not that much better. It definitely looks better with its gold accents though. There is very minimal keyboard flex and the screen hardly bends at all. Another nice upgrade over the Envy is the fact that its fans are configured in a much smarter way: intake on the bottom (like the Envy but with more holes) and output on both sides of the laptop (instead of out of the back). Using dual fans pushing air out of the sides makes it much easier to keep the Spectre and you cool, especially if you're putting the Spectre on top of something like a blanket. Overall, it's very thin and it's a little heavy but not too heavy.

Keyboard and Touchpad

This keyboard is about the same as on the HP Envy x360. It's pretty decent, and the backlight is pretty good. It's also full size, so you get your numpad as well. There's nothing particularly special about the keyboard. It's good. Some people might dislike the half sized up and down arrow keys, but personally I'm fine with it. The touchpad is okay, it's not quite as tall as I would like but it works good enough. No deal breakers here, though the Spectre isn't really amazing me with the keyboard and touchpad.

Display

While a 4K display does consume more power than a 1080p display, I have to say it's an incredible monitor. 4K may be overkill at such a small display, but damn does it look good. Just sublime. And compared to the Envy x360, the brightness is much better too. It's not the brightest monitor out there, but it'll do the job even in the sun. Colors look good as well, I haven't noticed any obvious gradients where colors gradually changed. On my Envy I could clearly see bands of colors on something like the sky. The Spectre has no problem displaying all the colors you need to see a smooth transition from one type of blue to another similar, but distinct blue. Bezels on the left and right are very thing, and while they're kind of thick on the bottom and top, it does allow for more space for the speakers and touchpad, as well as the webcam which is directly above the display.

Speakers

Kind of a mixed bag. I actually liked the speakers on the Envy, because they got pretty loud without distorting. When I couldn't get my cheap soundbar connected to my TV working one time, I used the speakers on the Envy instead, and the experience was pretty good. However, the experience with the Spectre is different. The speakers are now spread out over above the keyboard, and on the bottom of the chassis on the closest lower left and right corners. It just sounds a little off. It's totally fine, but it's not special.

Battery life

Battery life is okay, definitely not great though. Using the better battery life plan, setting the brightness to half, and running a Slow Mo Guys video at 4K resolution and 50 FPS, the laptop lasted a total of 3 hours and 46 minutes. For such a large battery, it's a disappointing result, but it's not surprising. The Vega M GPU, even though it was not used for this task, does require power even when it's idling, perhaps 5 or so watts. That's not nothing, and especially over time it's going to drain the battery.

Noise

Under full load, and even when watching 1080p60 videos or other high resolution content, the fans get pretty loud. Thankfully this keeps the system cool, but again, it does get loud. If you wanted a really quiet machine, the Spectre is not for you. Of course, there's a very good reason why it gets so loud and requires two fans.

Performance

Yep, that's right, it's because this laptop has alot of horsepower. The Spectre is based on the i7-8705G, which has not just an Intel CPU, but also a Radeon GPU. The Intel CPU has 4 cores, 8 threads, running at a maximum 4.1 GHz turbo and features Intel HD 630 graphics for use in low load applications. The Radeon Vega M GPU (which is really a Polaris GPU) has 20 CUs running at a maximum turbo of 1011 MHz and 4 GB of HBM2. On paper, this combination looks really good for everything from video editing to professional applications like CAD to gaming, and it should perform similarly to 7700HQ laptops with GTX 1050s to 1050Tis. Well, we'll see about that.

Our test suite includes these applications: Cinebench R15, 3D Mark Firestrike and Timespy, Ashes of the Singularity, Civilization VI, Total War: Rome II (with the new graphics patch), and the Witcher 3.

On Cinebench R15, the i7 scored 623 points on its best run, but in other runs the scores were as low as 480 and usually hovered around 550. This is likely due to thermal throttling. The i7 should boost very well under short loads but will fall behind if it can't finish a task before throttling sets in.

In 3DMark's Timespy, the Kaby Lake G processor scored 2167, and in Firestrike it scored 5161. Laptops with 7700HQs and 1050Tis typically make about 3000 points in Timespy and 7000 points in Firestrike. This is nearly a 50% difference, and it may surprise some of you. How could a 20 CU and 4 core CPU combo lose so heavily? Perhaps this processor lies closer to the 1050, but 1050Tis are not 50% faster than 1050s. Before I explain why the discrepancy exists, let's move on.

Using the standard preset at 1080p with the DX12 API on Ashes, the GPU focused benchmark scored an average framerate of 27.1 FPS (with all batches being GPU bound entirely) and the CPU focused benchmark scored an average of 16.8 FPS. I don't have any other hardware to compare this with, but I'm using mostly standardized benchmarks so that you can compare your own hardware or other benchmarks yourself.

Using the medium preset at 4K with the DX12 API on Civilization, the graphics benchmark ended up having an average frametime of 37.226 ms, which is mostly playable, and a 99th percentile of 44.947 ms. I'd recommend turning the settings down to low or the resolution down to 4K, but on a game like Civ it seems like a waste to not use 4K since the FPS doesn't matter that much. The AI benchmark resulted in an average turn time of 22.01.

And for our final benchmark, we have Rome II, which recently got some updates and new DLC. Using the in game benchmark with ultra settings at 1080p, the Kaby Lake G processor was able to achieve a framerate of 30.7. I'd recommend turning the settings down a tad since framerate is somewhat important for Total War and you won't be caring too much about looks when you're doing battle.

Now, I did say I was going to test Witcher 3, but not actually benchmark it since there's no point. I wanted to bring attention to the fact that the 8705G can play Witcher 3 with a blend of low and ultra settings (because going from low to ultra on some settings does not impact performance) at about 45-60 FPS. Overall, the Kaby Lake G processor is very impressive given the cooling limitations of the laptop's design.

Now, why is the processor underperforming? On paper, it should be a good deal faster than a 1050 and at least only a little slower than a 1050Ti. Well, earlier I mentioned thermal throttling playing a part in Cinebench's performance, but in this case I believe something else is more to blame: power throttling. You see, the CPU and GPU only have 65 watts between them. A 7700HQ alone can use 35-45 watts. The HBM and GPU also need to get power. What will happen is that the harder the GPU is hit, the less power the CPU is allowed to use, and in some games you may see the i7 go as low as 2 GHz on all cores. However, I personally am very happy with performance.

Conclusion

Overall, the HP Spectre is a very well balanced machine. It's pretty thin, it's got good performance, it has a 4K display with enough brightness and color accuracy, it has good battery life, and it's not super expensive. If I had to give this a score out of ten, I'd give it a 9. Points off for disappointing battery life and performance, but you will have a hard time finding a laptop this thin, with this battery performance and computational power, at this price point. It's not a gaming laptop, but it works fine as one. Stuff like CSGO should work really well since it's a game highly dependent on the CPU and not the GPU. With many laptops, you make compromises like having a really big battery and then having almost no performance to speak of, or having a great GPU and CPU but it weights like 15 pounds, is more than an inch thick, and costs a fortune. The Spectre on the other hand has no major compromises and is an excellent choice for people who don't need a laptop that's the best at only one thing.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

My recent experience with depression, anxiety, and ADHD

I figured I would make a post about this, because I know that at least a few of my mutuals are dealing with some or all of these things themselves and might find this helpful. Who knows? Very long, very personal, but mostly positive post under the cut. Like, really, more information than you probably ever wanted to know about me and my problems. Proceed, if you feel so inclined.

First, a brief history, for context. Throughout elementary and high school, I consistently scored in the 99th percentile on standardized tests. Then, I almost flunked out of high school, barely got my diploma, took a year off, and started art school college for an animation English degree. I was going to write novels. After a year or two of that, I decided I could write without a degree, so I dropped out. What followed was a decade of several strangely varied and unrelated jobs and no novel writing. Working a stable corporate gig while not accomplishing (or even pursuing) any of my personal creative goals was DESTROYING MY SOUL. So, I quit my job to become a full-time student and finish my degree, because at least that was kind of in the same universe as actually being creative. And now, a year or two later, here I am, 32 and a few semesters away from finally finishing that English degree. Clearly brains won’t get you everywhere kids.

I was diagnosed with ADHD at age 7 and was on some form of medication until sometime in high school, when I decided I didn’t want to take it anymore, for reasons I won’t bother getting into. It never occurred to me to even consider medication again until this semester, when everything fell apart.

ADHD can impact a person in a multitude of ways. For me, the biggest impact is probably executive function issues. I can wander through the garden of my ideas all day long. I cannot make myself sit down and do work, no matter how much I may want to. For personal goals, that means a literal solid decade of zero accomplishment. For school, that means procrastinating papers until the night before or morning of or sometimes even two weeks late, on the night before the professor has to turn in their grades. And the level of personal effort it took to make myself write that two-week-late paper was herculean in measure, when it really should not have been.

I’ve since learned that many professionals suspect this very common procrastination habit of ADHD folks is actually a kind of self-medicating by way of adrenaline via stress response. Which sounds entirely plausible to me, because every semester since I’ve been back at school, I’ve found myself pushing the risky boundaries of procrastination further and further, like a drug addict needing a higher dose to get a fix. A very unsustainable and unhappy process all around.

Which brings me to this semester, when the wheels finally fell off the car, and one of the campus psychologists found me crying on a bench outside the counseling center because they were closed for lunch and meetings, and I didn’t know where else to go. I couldn’t do any of my homework, was crying every day, and having panic attacks. To put it simply, I was a fucking mess.

I made more appointments at the counseling center, I spoke with my professors about what I was going through (hello more panic attacks), and for the first time in over a decade, I remembered that there are medications I should maybe try, and I made an appointment to see the psychiatrist at the campus medical clinic. (Also, guys, if any of you are students, look into your campus resources. There’s support for everything at my school. There’s even an office that’s only there to help guide students to all the other support options. Seriously, mental health, child care, food, housing, you name it. Get the help you need.)

When I explained everything I had been going through, the very nice psychiatrist at the clinic told me, with an unsettling degree of alarm in her voice, that I was “deeply depressed”. Which, I knew, but she really sounded shockingly concerned. And it’s like, jeeze, I maybe didn’t realize just how bad things had gotten, because I was just living with this shit every day, so it was kind of ‘normal’ for me.

Anyway, she agreed to start me on meds for my ADHD. The one I’ve been taking is called Vyvanse. I started on the lowest dose and have been gradually increasing. A month in, I’m at a dose where I can clearly tell a difference, and it’s having a noticeable impact. I wrote a meta yesterday. I was thinking the thoughts, and just sat down and wrote it. This morning, I got up and wrote some more, just notes for future things to do, but I did it. Fuck, I’m writing this fucking thing right now.

I thought that maybe I should write this shit out, and it took a little while sitting and getting my momentum going, but now I’ve written 800 1300 1650 words. And I’m sitting here actually crying as I type this paragraph, because this small little thing is like the biggest fucking thing in my life.

I don’t have any way to accurately explain what a big deal it is for me to have actively decided to write something and then to have actually actively produced content of my own volition and design, that wasn’t assigned to me and didn’t have a due date or a grade attached. And, that I’ve done it repeatedly now…

OVER TEN YEARS. Over ten years I went, writing almost nothing. Might as well have been zero words. Guys, I’ve been walking around with a trilogy of speculative fiction novels in my head for over ten years, I’ve been planning another unrelated novel for the last two. I’ve been planning something like 30 fanfics, across two fandoms, and another 20 metas for the past year. Part of me probably assumed feared that none of that would ever see the light of day. But now, it suddenly feels like maybe I’ll actually manage to write some of it. And I’m hoping like fuck that it’s not just a fluke.

Now, the ADHD meds aren’t the only thing I’ve been doing to contribute to this ‘good place’ I’m in currently. I’ve been going to counseling. Apparently, I have a lot of negative feelings about myself and my inability to accomplish jack shit for a whole decade. Who would’ve guessed? I also have weekly sessions with the disabilities accessibility team at my university to work on external methods for dealing with my executive function issues. (Again, if you’re a student, utilize your university resources. You’re already paying for them with tuition.) And, this is obviously not an option for everyone, but even before I started the ADHD meds, I took advantage of the fact that I live in a state where certain botanical products are easily and legally available and found a brand of gummies that really help with my anxiety and panic attacks. (They’re high cbd, low thc, so calming and don’t make you high.)

So far, the meds aren’t 100% sunshine and rainbows. With the dose I’m at right now, where I’ve been Getting Things Done, I can actively feel the drug, which is… not the greatest. I feel jittery, vaguely anxious, like I’ve drank way too much coffee but worse. And, the decreased appetite is something I really have to be vigilant about, because I don’t have any room to lose weight. These were both known possible side effects of stimulant meds, so I wasn’t surprised, and perhaps the doctor and I will be able to fine tune the dosing or try another med or something. But right now, I think I’m really leaning toward, I’ll put up with the side effects, because holy shit, I can finally actually do what I want to do. Also, I think (and Nice Doctor Lady thinks) the new higher dose is having a positive, stabilizing impact on my mood.

I guess my reason for writing all of this, other than pure catharsis, is to say, if you’re dealing with shit like this, try to be willing to consider all your options. For whatever reason, I didn’t think about trying medication for my condition. It wasn’t even like I was anti-meds or something. I just didn’t even think about it. Not until a few months back, when I sent a random ask to an ADHD blog on here, asking how they managed to make themselves write, and they responded with I had to get medication. Suddenly, it was like… why have I not been considering this option? So, this story is for anyone else out there that maybe also hadn’t thought to consider this option.

And really, not just the medication. I’m a hide behind walls, overly independent, do things on my own, never ask for help sort of person. But, I guess I finally reached a level of desperation where I was like, Clearly, doing this by myself, my way, has not gotten me the results I want. So, fuck it, I’m going to ask for help from every professional available to me. Which, I’m very lucky, and currently have ready access to multiple resources in a way not everyone does, but being open to getting this much assistance is very new territory for me.

I’m not really sure how best to wrap this up. If anyone actually read all of this, I’m astonished and… Hi, I guess? You really know quite a bit about me now. Hopefully, I haven’t scared anyone off. And, if anybody has further questions about any of this or you want to talk about your own issues, I’m sincerely available for that. I think the world we live in today makes it too easy to feel completely alone, even when you’re surrounded by people, and I’m here for chats, if you need it.

#well...#okay then#this exists#just a short 1650 word personal essay#yikes#anyway#shut up fraddit#fraddit talks mental health#give this topic it's own tag#in case i make any follow up posts

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another MCQ Test on the USMLE

By BRYAN CARMODY, MD

One of the most fun things about the USMLE pass/fail debate is that it’s accessible to everyone. Some controversies in medicine are discussed only by the initiated few – but if we’re talking USMLE, everyone can participate.

Simultaneously, one of the most frustrating things about the USMLE pass/fail debate is that everyone’s an expert. See, everyone in medicine has experience with the exam, and on the basis of that, we all think that we know everything there is to know about it.

Unfortunately, there’s a lot of misinformation out there – especially when we’re talking about Step 1 score interpretation. In fact, some of the loudest voices in this debate are the most likely to repeat misconceptions and outright untruths.

Hey, I’m not pointing fingers. Six months ago, I thought I knew all that I needed to know about the USMLE, too – just because I’d taken the exams in the past.

But I’ve learned a lot about the USMLE since then, and in the interest of helping you interpret Step 1 scores in an evidence-based manner, I’d like to share some of that with you here.

However…

If you think I’m just going to freely give up this information, you’re sorely mistaken. Just as I’ve done in the past, I’m going to make you work for it, one USMLE-style multiple choice question at a time._

Question 1

A 25 year old medical student takes USMLE Step 1. She scores a 240, and fears that this score will be insufficient to match at her preferred residency program. Because examinees who pass the test are not allowed to retake the examination, she constructs a time machine; travels back in time; and retakes Step 1 without any additional study or preparation.

Which of the following represents the 95% confidence interval for the examinee’s repeat score, assuming the repeat test has different questions but covers similar content?

A) 239-241

B) 237-243

C) 234-246

D) 228-252

_

The correct answer is D, 228-252.

No estimate is perfectly precise. But that’s what the USMLE (or any other test) gives us: a point estimate of the test-taker’s true knowledge.

So how precise is that estimate? That is, if we let an examinee take the test over and over, how closely would the scores cluster?

To answer that question, we need to know the standard error of measurement (SEM) for the test.

The SEM is a function of both the standard deviation and reliability of the test, and represents how much an individual examinee’s observed score might vary if he or she took the test repeatedly using different questions covering similar material.

So what’s the SEM for Step 1? According to the USMLE’s Score Interpretation Guidelines, the SEM for the USMLE is 6 points.

Around 68% of scores will fall +/- 1 SEM, and around 95% of scores fall within +/- 2 SEM. Thus, if we accept the student’s original Step 1 score as our best estimate of her true knowledge, then we’d expect a repeat score to fall between 234 and 246 around two-thirds of the time. And 95% of the time, her score would fall between 228 and 252.

Think about that range for a moment.

The +/- 1 SEM range is 12 points; the +/- 2 SEM range is 24 points. Even if you believe that Step 1 tests meaningful information that is necessary for successful participation in a selective residency program, how many people are getting screened out of those programs by random chance alone?

(To their credit, the NBME began reporting a confidence interval to examinees with the 2019 update to the USMLE score report.)

Learning Objective: Step 1 scores are not perfectly precise measures of knowledge – and that imprecision should be considered when interpreting their values.

__

Question 2

A 46 year old program director seeks to recruit only residents of the highest caliber for a selective residency training program. To accomplish this, he reviews the USMLE Step 1 scores of three pairs of applicants, shown below.

230 vs. 235

232 vs. 242

234 vs. 249

For how many of these candidate pairs can the program director conclude that there is a statistical difference in knowledge between the applicants?

A) Pairs 1, 2, and 3

B) Pairs 2 and 3

C) Pair 3 only

D) None of the above

–

The correct answer is D, none of the above.

As we learned in Question 1, Step 1 scores are not perfectly precise. In a mathematical sense, an individual’s Step 1 score on a given day represents just one sampling from the distribution centered around their true mean score (if the test were taken repeatedly).

So how far apart do two individual samples have to be for us to confidently conclude that they came from distributions with different means? In other words, how far apart do two candidates’ Step 1 scores have to be for us to know that there is really a significant difference between the knowledge of each?

We can answer this by using the standard error of difference (SED). When the two samples are >/= 2 SED apart, then we can be confident that there is a statistical difference between those samples.

So what’s the SED for Step 1? Again, according to the USMLE’s statisticians, it’s 8 points.

That means that, for us to have 95% confidence that two candidates really have a difference in knowledge, their Step 1 scores must be 16 or more points apart.

Now, is that how you hear people talking about Step 1 scores in real life? I don’t think so. I frequently hear people discussing how a 5-10 point difference in scores is a major difference that totally determines success or failure within a program or specialty.

And you know what? Mathematics aside, they’re not wrong. Because when programs use rigid cutoffs for screening, only the point estimate matters – not the confidence interval. If your dream program has a cutoff score of 235, and you show up with a 220 or a 225, your score might not be statistically different – but your dream is over.

Learning Objective: To confidently conclude that two students’ Step 1 scores really reflect a difference in knowledge, they must be >/= 16 points apart.

__

Question 3

A physician took USMLE Step 1 in 1994, and passed with a score of 225. Now he serves as program director for a selective residency program, where he routinely screens out applicants with scores lower than 230. When asked about his own Step 1 score, he explains that today’s USMLE are “inflated” from those 25 years ago, and if he took the test today, his score would be much higher.

Assuming that neither the test’s content nor the physician’s knowledge had changed since 1994, which of the following is the most likely score the physician would attain if he took Step 1 in 2019?

A) 205

B) 225

C) 245

D) 265

–

The correct answer is B, 225.

Sigh.

I hear this kind of claim all the time on Twitter. So once and for all, let’s separate fact from fiction.

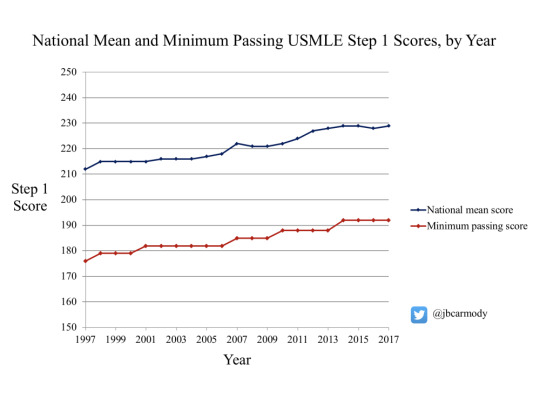

FACT: Step 1 scores for U.S. medical students score are rising.

See the graphic below.

FICTION: The rise in scores reflects a change in the test or the way it’s scored.

See, the USMLE has never undergone a “recentering” like the old SAT did. Students score higher on Step 1 today than they did 25 years ago because students today answer more questions correctly than those 25 years ago.

Why? Because Step 1 scores matter more now than they used to. Accordingly, students spend more time in dedicated test prep (using more efficient studying resources) than they did back in the day. The net result? The bell curve of Step 1 curves shifts a little farther to the right each year.

Just how far the distribution has already shifted is impressive.

When the USMLE began in the early 1990s, a score of 200 was a perfectly respectable score. Matter of fact, it put you exactly at the mean for U.S. medical students.

Know what a score of 200 gets you today?

A score in the 9th percentile, and screened out of almost any residency program that uses cut scores. (And nearly two-thirds of all programs do.)

So the program director in the vignette above did pretty well for himself by scoring a 225 twenty-five years ago. A score that high (1.25 standard deviations above the mean) would have placed him around the 90th percentile for U.S. students. To hit the same percentile today, he’d need to drop a 255.

Now, can you make the argument that the type of student who scored in the 90th percentile in the past would score in the 90th percentile today? Sure. He might – but not without devoting a lot more time to test prep.

As I’ve discussed in the past, this is one of my biggest concerns with Step 1 Mania. Students are trapped in an arms race with no logical end, competing to distinguish themselves on the metric we’ve told them matters. They spend more and more time learning basic science that’s less and less clinically relevant, all at at the expense (if not outright exclusion) of material that might actually benefit them in their future careers.

(If you’re not concerned about the rising temperature in the Step 1 frog pot, just sit tight for a few years. The mean Step 1 score is rising at around 0.9 points per year. Just come on back in a while once things get hot enough for you.)

Learning Objective: Step 1 scores are rising – not because of a change in test scoring, but because of honest-to-God higher performance.

_

Question 4

Two medical students take USMLE Step 1. One scores a 220 and is screened out of his preferred residency program. The other scores a 250 and is invited for an interview.

Which of the following represents the most likely absolute difference in correctly-answered test items for this pair of examinees?

A) 5

B) 30

C) 60

D) 110

_

The correct answer is B, 30.

How many questions do you have to answer correctly to pass USMLE Step 1? What percentage do you have to get right to score a 250, or a 270? We don’t know.

See, the NBME does not disclose how it arrives at a three digit score. And I don’t have any inside information on this subject. But we can use logic and common sense to shed some light on the general processes and data involved and arrive at a pretty good guess.

First, we need to briefly review how the minimum passing score for the USMLE is set, using a modified Angoff procedure.

The Angoff procedure involves presenting items on the test to subject matter experts (SMEs). The SMEs review each question item and predict what percentage of minimally competent examinees would answer the question correctly.

Here’s an example of what Angoff data look like (the slide is from a recent lecture).

As you can see, Judge A suspected that 59% of minimally competent candidates – the bare minimum we could tolerate being gainfully engaged in the practice of medicine – would answer Item 1 correctly. Judge B thought 52% of the same group would get it right, and so on.

Now, here’s the thing about the version of the Angoff procedure used to set the USMLE’s passing standard. Judges don’t just blurt out a guess off the top of their head and call it a day. They get to review data regarding real-life examinee performance, and are permitted to use that to adjust their initial probabilities.

Here’s an example of the performance data that USMLE subject matter experts receive. This graphic shows that test-takers who were in the bottom 10% of overall USMLE scores answered a particular item correctly 63% of the time.

(As a sidenote, when judges are shown data on actual examinee performance, their predictions shift toward the data they’ve been shown. In theory, that’s a good thing. But multiple studies – including one done by the NBME – show that judges change their original probabilities even when they’re given totally fictitious data on examinee performance.)

For the moment, let’s accept the modified Angoff procedure as being valid. Because if we do, it gives us the number we need to set the minimum passing score. All we have to do is calculate the mean of all the probabilities assigned for that group of items by the subject matter experts.

In the slide above, the mean probability that a minimally competent examinee would correctly answer these 10 items was 0.653 (red box). In other words, if you took this 10 question test, you’d need to score better than 65% (i.e., 7 items correct) to pass.

And if we wanted to assign scores to examinees who performed better than the passing standard, we could. But, we’ll only have 3 questions with which to do it, since we used 7 of the 10 questions to define the minimally competent candidate.

So how many questions do we have to assign scores to examinees who pass USMLE Step 1?

Well, Step 1 includes 7 sections with up to 40 questions in each. So there are a maximum of 280 questions on the exam.

However, around 10% of these are “experimental” items. These questions do not count toward the examinee’s score – they’re on the test to generate performance data (like Figure 1 above) to present in the future to subject matter experts. Once these items have been “Angoffed”, they will become scored items on future Step 1 tests, and a new wave of experimental items will be introduced.

If we take away the 10% of items that are experimental, then we have at most 252 questions to score.

How many of these questions must be answered correctly to pass? Here, we have to use common sense to make a ballpark estimate.

After all, a candidate with no medical knowledge who just guessed answers at random might get 25% of the questions correct. Intuitively, it seems like the lower bound of knowledge to be licensed as a physician has to be north of 50% of items, right?

At the same time, we know that the USMLE doesn’t include very many creampuff questions that everyone gets right. Those questions provide no discriminatory value. Actually, I’d wager that most Step 1 questions have performance data that looks very similar to Figure 1 above (which was taken from an NBME paper).

A question like the one shown – which 82% of examinees answered correctly – has a nice spread of performance across the deciles of exam performance, ranging from 63% among low performers to 95% of high performers. That’s a question with useful discrimination for an exam like the USMLE.

Still, anyone who’s taken Step 1 knows that some questions will be much harder, and that fewer than 82% of examinees will answer correctly. If we conservatively assume that there are only a few of these “hard questions” on the exam, then we might estimate that the average Step 1 taker is probably getting around ~75% of questions right. (It’s hard to make a convincing argument that the average examinee could possibly be scoring much higher. And in fact, one of few studies that mentions this issue actually reports that the mean item difficulty was 76%.)

The minimum passing standard has to be lower than the average performance – so let’s ballpark that to be around 65%. (Bear in mind, this is just an estimate – and I think, a reasonably conservative one. But you can run the calculations with lower or higher percentages if you want. The final numbers I show below won’t be that much different than yours unless you use numbers that are implausible.)

Everyone still with me? Great.

Now, if a minimally competent examinee has to answer 65% of questions right to pass, then we have only 35% the of the ~252 scorable questions available to assign scores among all of the examinees with more than minimal competence.

In other words, we’re left with somewhere ~85 questions to help us assign scores in the passing range.

The current minimum passing score for Step 1 is 194. And while the maximum score is 300 in theory, the real world distribution goes up to around 275.

Think about that. We have ~85 questions to determine scores over around an 81 point range. That’s approximately one point per question.

Folks, this is what drives #Step1Mania.

Note, however, that the majority of Step 1 scores for U.S./Canadian students fall across a thirty point range from 220 to 250.

That means that, despite the power we give to USMLE Step 1 in residency selection, the absolute performance for most applicants is similar. In terms of raw number of questions answered, most U.S. medical student differ by fewer than 30 correctly-answered multiple choice questions. That’s around 10% of a seven hour, 280 question test administered on a single day.

And what important topics might those 30 questions test? Well, I’ve discussed that in the past.

Learning Objective: In terms of raw performance, most U.S. medical students likely differ by 30 or fewer correctly-answered questions on USMLE Step 1 (~10% of a 280 question test).

__

Question 5

A U.S. medical student takes USMLE Step 1. Her score is 191. Because the passing score is 194, she cannot seek licensure.

Which of the following reflects the probability that this examinee will pass the test if she takes it again?

A) 0%

B) 32%

C) 64%

D) 96%

–

The correct answer is C, 64%.

In 2016, 96% of first-time test takers from U.S. allopathic medical schools passed Step 1. For those who repeated the test, the pass rate was 64%. What that means is that >98% of U.S. allopathic medical students ultimately pass the exam.

I bring this up to highlight again how the Step 1 score is an estimate of knowledge at a specific point in time. And yet, we often treat Step 1 scores as if they are an immutable personality characteristic – a medical IQ, stamped on our foreheads for posterity.

But medical knowledge changes over time. I took Step 1 in 2005. If I took the test today, I would absolutely score lower than I did back then. I might even fail the test altogether.

But here’s the thing: which version of me would you want caring for your child? The 2005 version or the 2019 version?

The more I’ve thought about it, the stranger it seems that we even use this test for licensure (let alone residency selection). After all, if our goal is to evaluate competency for medical practice, shouldn’t a doctor in practice be able to pass the exam? I mean, if we gave a test of basketball competency to an NBA veteran, wouldn’t he do better than a player just starting his career? If we gave a test of musical competency to a concert pianist with a decade of professional experience, shouldn’t she score higher than a novice?

If we accept that the facts tested on Step 1 are essential for the safe and effective practice of medicine, is there really a practical difference between an examinee who doesn’t know these facts initially and one who knew them once but forgets them over time? If the exam truly tests competency, aren’t both of these examinees equally incompetent?

We have made the Step 1 score into the biggest false god in medical education.

By itself, Step 1 is neither good nor bad. It’s just a multiple choice test of medically-oriented basic science facts. It measures something – and if we appropriately interpret the measurement in context with the test’s content and limitations, it may provide some useful information, just like any other test might.

It’s our idolatry of the test that is harmful. We pretend that the test measures things that it doesn’t – because it makes life easier to do so. After all, it’s hard to thin a giant pile of residency applications with nuance and confidence intervals. An applicant with a 235 may be no better (or even, no different) than an applicant with a 230 – but by God, a 235 is higher.

It’s well beyond time to critically appraise this kind of idol worship. Whether you support a pass/fail Step 1 or not, let’s at least commit to sensible use of psychometric instruments.

Learning Objective: A Step 1 score is a measurement of knowledge at a specific point in time. But knowledge changes over time.

_

Score Report

So how’d you do?

I realize that some readers may support a pass/fail Step 1, while others may want to maintain a scored test. So to be sure everyone receives results of this test in their preferred format, I made a score report for both groups.

_

NUMERIC SCORE

Just like the real test, each question above is worth 1 point. And while some of you may say it’s non-evidence based, this is my test, and I say that one point differences in performance allow me to make broad and sweeping categorizations about you.

1 POINT – UNMATCHED

But thanks for playing. Good luck in the SOAP!

2 POINTS – ELIGIBLE FOR LICENSURE

Nice job. You’ve got what it takes to be licensed. (Or at least, you did on a particular day.)

3 POINTS – INTERVIEW OFFER!

Sure, the content of these questions may have essentially nothing to do with your chosen discipline, but your solid performance got your foot in the door. Good work.

4 POINTS – HUSAIN SATTAR, M.D.

You’re not just a high scorer – you’re a hero and a legend.

5 POINTS – NBME EXECUTIVE

Wow! You’re a USMLE expert. You should celebrate your outstanding performance with some $45 tequila shots while dancing at eye-level with the city skyline.

_

PASS/FAIL

FAIL

You regard USMLE Step 1 scores with a kind of magical thinking. They are not simply a one-time point estimate of basic science knowledge, or a tool that can somewhat usefully be applied to thin a pile of residency applications. Nay, they are a robust and reproducible glimpse into the very being of a physician, a perfectly predictive vocational aptitude test that is beyond reproach or criticism.

PASS

You realize that, whatever Step 1 measures, it is a rather imprecise in measuring that thing. You further appreciate that, when Step 1 scores are used for whatever purpose, there are certain practical and theoretical limitations on their utility. You understand – in real terms – what a Step 1 score really means.

(I only hope that the pass rate for this exam is as high as the real Step 1 pass rate.)

Dr. Carmody is a pediatric nephrologist and medical educator at Eastern Virginia Medical School. This post originally appeared on The Sheriff of Sodium here.

Another MCQ Test on the USMLE published first on https://wittooth.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

Another MCQ Test on the USMLE

By BRYAN CARMODY, MD

One of the most fun things about the USMLE pass/fail debate is that it’s accessible to everyone. Some controversies in medicine are discussed only by the initiated few – but if we’re talking USMLE, everyone can participate.

Simultaneously, one of the most frustrating things about the USMLE pass/fail debate is that everyone’s an expert. See, everyone in medicine has experience with the exam, and on the basis of that, we all think that we know everything there is to know about it.

Unfortunately, there’s a lot of misinformation out there – especially when we’re talking about Step 1 score interpretation. In fact, some of the loudest voices in this debate are the most likely to repeat misconceptions and outright untruths.

Hey, I’m not pointing fingers. Six months ago, I thought I knew all that I needed to know about the USMLE, too – just because I’d taken the exams in the past.

But I’ve learned a lot about the USMLE since then, and in the interest of helping you interpret Step 1 scores in an evidence-based manner, I’d like to share some of that with you here.

However…

If you think I’m just going to freely give up this information, you’re sorely mistaken. Just as I’ve done in the past, I’m going to make you work for it, one USMLE-style multiple choice question at a time._

Question 1

A 25 year old medical student takes USMLE Step 1. She scores a 240, and fears that this score will be insufficient to match at her preferred residency program. Because examinees who pass the test are not allowed to retake the examination, she constructs a time machine; travels back in time; and retakes Step 1 without any additional study or preparation.

Which of the following represents the 95% confidence interval for the examinee’s repeat score, assuming the repeat test has different questions but covers similar content?

A) 239-241

B) 237-243

C) 234-246

D) 228-252

_

The correct answer is D, 228-252.

No estimate is perfectly precise. But that’s what the USMLE (or any other test) gives us: a point estimate of the test-taker’s true knowledge.

So how precise is that estimate? That is, if we let an examinee take the test over and over, how closely would the scores cluster?

To answer that question, we need to know the standard error of measurement (SEM) for the test.

The SEM is a function of both the standard deviation and reliability of the test, and represents how much an individual examinee’s observed score might vary if he or she took the test repeatedly using different questions covering similar material.

So what’s the SEM for Step 1? According to the USMLE’s Score Interpretation Guidelines, the SEM for the USMLE is 6 points.

Around 68% of scores will fall +/- 1 SEM, and around 95% of scores fall within +/- 2 SEM. Thus, if we accept the student’s original Step 1 score as our best estimate of her true knowledge, then we’d expect a repeat score to fall between 234 and 246 around two-thirds of the time. And 95% of the time, her score would fall between 228 and 252.

Think about that range for a moment.

The +/- 1 SEM range is 12 points; the +/- 2 SEM range is 24 points. Even if you believe that Step 1 tests meaningful information that is necessary for successful participation in a selective residency program, how many people are getting screened out of those programs by random chance alone?

(To their credit, the NBME began reporting a confidence interval to examinees with the 2019 update to the USMLE score report.)

Learning Objective: Step 1 scores are not perfectly precise measures of knowledge – and that imprecision should be considered when interpreting their values.

__

Question 2

A 46 year old program director seeks to recruit only residents of the highest caliber for a selective residency training program. To accomplish this, he reviews the USMLE Step 1 scores of three pairs of applicants, shown below.

230 vs. 235

232 vs. 242

234 vs. 249

For how many of these candidate pairs can the program director conclude that there is a statistical difference in knowledge between the applicants?

A) Pairs 1, 2, and 3

B) Pairs 2 and 3

C) Pair 3 only

D) None of the above

–

The correct answer is D, none of the above.

As we learned in Question 1, Step 1 scores are not perfectly precise. In a mathematical sense, an individual’s Step 1 score on a given day represents just one sampling from the distribution centered around their true mean score (if the test were taken repeatedly).

So how far apart do two individual samples have to be for us to confidently conclude that they came from distributions with different means? In other words, how far apart do two candidates’ Step 1 scores have to be for us to know that there is really a significant difference between the knowledge of each?

We can answer this by using the standard error of difference (SED). When the two samples are >/= 2 SED apart, then we can be confident that there is a statistical difference between those samples.

So what’s the SED for Step 1? Again, according to the USMLE’s statisticians, it’s 8 points.

That means that, for us to have 95% confidence that two candidates really have a difference in knowledge, their Step 1 scores must be 16 or more points apart.

Now, is that how you hear people talking about Step 1 scores in real life? I don’t think so. I frequently hear people discussing how a 5-10 point difference in scores is a major difference that totally determines success or failure within a program or specialty.

And you know what? Mathematics aside, they’re not wrong. Because when programs use rigid cutoffs for screening, only the point estimate matters – not the confidence interval. If your dream program has a cutoff score of 235, and you show up with a 220 or a 225, your score might not be statistically different – but your dream is over.

Learning Objective: To confidently conclude that two students’ Step 1 scores really reflect a difference in knowledge, they must be >/= 16 points apart.

__

Question 3

A physician took USMLE Step 1 in 1994, and passed with a score of 225. Now he serves as program director for a selective residency program, where he routinely screens out applicants with scores lower than 230. When asked about his own Step 1 score, he explains that today’s USMLE are “inflated” from those 25 years ago, and if he took the test today, his score would be much higher.

Assuming that neither the test’s content nor the physician’s knowledge had changed since 1994, which of the following is the most likely score the physician would attain if he took Step 1 in 2019?

A) 205

B) 225

C) 245

D) 265

–

The correct answer is B, 225.

Sigh.

I hear this kind of claim all the time on Twitter. So once and for all, let’s separate fact from fiction.

FACT: Step 1 scores for U.S. medical students score are rising.

See the graphic below.

FICTION: The rise in scores reflects a change in the test or the way it’s scored.

See, the USMLE has never undergone a “recentering” like the old SAT did. Students score higher on Step 1 today than they did 25 years ago because students today answer more questions correctly than those 25 years ago.

Why? Because Step 1 scores matter more now than they used to. Accordingly, students spend more time in dedicated test prep (using more efficient studying resources) than they did back in the day. The net result? The bell curve of Step 1 curves shifts a little farther to the right each year.

Just how far the distribution has already shifted is impressive.

When the USMLE began in the early 1990s, a score of 200 was a perfectly respectable score. Matter of fact, it put you exactly at the mean for U.S. medical students.

Know what a score of 200 gets you today?

A score in the 9th percentile, and screened out of almost any residency program that uses cut scores. (And nearly two-thirds of all programs do.)

So the program director in the vignette above did pretty well for himself by scoring a 225 twenty-five years ago. A score that high (1.25 standard deviations above the mean) would have placed him around the 90th percentile for U.S. students. To hit the same percentile today, he’d need to drop a 255.

Now, can you make the argument that the type of student who scored in the 90th percentile in the past would score in the 90th percentile today? Sure. He might – but not without devoting a lot more time to test prep.

As I’ve discussed in the past, this is one of my biggest concerns with Step 1 Mania. Students are trapped in an arms race with no logical end, competing to distinguish themselves on the metric we’ve told them matters. They spend more and more time learning basic science that’s less and less clinically relevant, all at at the expense (if not outright exclusion) of material that might actually benefit them in their future careers.

(If you’re not concerned about the rising temperature in the Step 1 frog pot, just sit tight for a few years. The mean Step 1 score is rising at around 0.9 points per year. Just come on back in a while once things get hot enough for you.)

Learning Objective: Step 1 scores are rising – not because of a change in test scoring, but because of honest-to-God higher performance.

_

Question 4

Two medical students take USMLE Step 1. One scores a 220 and is screened out of his preferred residency program. The other scores a 250 and is invited for an interview.

Which of the following represents the most likely absolute difference in correctly-answered test items for this pair of examinees?

A) 5

B) 30

C) 60

D) 110

_

The correct answer is B, 30.

How many questions do you have to answer correctly to pass USMLE Step 1? What percentage do you have to get right to score a 250, or a 270? We don’t know.

See, the NBME does not disclose how it arrives at a three digit score. And I don’t have any inside information on this subject. But we can use logic and common sense to shed some light on the general processes and data involved and arrive at a pretty good guess.

First, we need to briefly review how the minimum passing score for the USMLE is set, using a modified Angoff procedure.

The Angoff procedure involves presenting items on the test to subject matter experts (SMEs). The SMEs review each question item and predict what percentage of minimally competent examinees would answer the question correctly.

Here’s an example of what Angoff data look like (the slide is from a recent lecture).

As you can see, Judge A suspected that 59% of minimally competent candidates – the bare minimum we could tolerate being gainfully engaged in the practice of medicine – would answer Item 1 correctly. Judge B thought 52% of the same group would get it right, and so on.

Now, here’s the thing about the version of the Angoff procedure used to set the USMLE’s passing standard. Judges don’t just blurt out a guess off the top of their head and call it a day. They get to review data regarding real-life examinee performance, and are permitted to use that to adjust their initial probabilities.

Here’s an example of the performance data that USMLE subject matter experts receive. This graphic shows that test-takers who were in the bottom 10% of overall USMLE scores answered a particular item correctly 63% of the time.

(As a sidenote, when judges are shown data on actual examinee performance, their predictions shift toward the data they’ve been shown. In theory, that’s a good thing. But multiple studies – including one done by the NBME – show that judges change their original probabilities even when they’re given totally fictitious data on examinee performance.)

For the moment, let’s accept the modified Angoff procedure as being valid. Because if we do, it gives us the number we need to set the minimum passing score. All we have to do is calculate the mean of all the probabilities assigned for that group of items by the subject matter experts.

In the slide above, the mean probability that a minimally competent examinee would correctly answer these 10 items was 0.653 (red box). In other words, if you took this 10 question test, you’d need to score better than 65% (i.e., 7 items correct) to pass.

And if we wanted to assign scores to examinees who performed better than the passing standard, we could. But, we’ll only have 3 questions with which to do it, since we used 7 of the 10 questions to define the minimally competent candidate.

So how many questions do we have to assign scores to examinees who pass USMLE Step 1?

Well, Step 1 includes 7 sections with up to 40 questions in each. So there are a maximum of 280 questions on the exam.

However, around 10% of these are “experimental” items. These questions do not count toward the examinee’s score – they’re on the test to generate performance data (like Figure 1 above) to present in the future to subject matter experts. Once these items have been “Angoffed”, they will become scored items on future Step 1 tests, and a new wave of experimental items will be introduced.

If we take away the 10% of items that are experimental, then we have at most 252 questions to score.

How many of these questions must be answered correctly to pass? Here, we have to use common sense to make a ballpark estimate.

After all, a candidate with no medical knowledge who just guessed answers at random might get 25% of the questions correct. Intuitively, it seems like the lower bound of knowledge to be licensed as a physician has to be north of 50% of items, right?

At the same time, we know that the USMLE doesn’t include very many creampuff questions that everyone gets right. Those questions provide no discriminatory value. Actually, I’d wager that most Step 1 questions have performance data that looks very similar to Figure 1 above (which was taken from an NBME paper).

A question like the one shown – which 82% of examinees answered correctly – has a nice spread of performance across the deciles of exam performance, ranging from 63% among low performers to 95% of high performers. That’s a question with useful discrimination for an exam like the USMLE.

Still, anyone who’s taken Step 1 knows that some questions will be much harder, and that fewer than 82% of examinees will answer correctly. If we conservatively assume that there are only a few of these “hard questions” on the exam, then we might estimate that the average Step 1 taker is probably getting around ~75% of questions right. (It’s hard to make a convincing argument that the average examinee could possibly be scoring much higher. And in fact, one of few studies that mentions this issue actually reports that the mean item difficulty was 76%.)

The minimum passing standard has to be lower than the average performance – so let’s ballpark that to be around 65%. (Bear in mind, this is just an estimate – and I think, a reasonably conservative one. But you can run the calculations with lower or higher percentages if you want. The final numbers I show below won’t be that much different than yours unless you use numbers that are implausible.)

Everyone still with me? Great.

Now, if a minimally competent examinee has to answer 65% of questions right to pass, then we have only 35% the of the ~252 scorable questions available to assign scores among all of the examinees with more than minimal competence.

In other words, we’re left with somewhere ~85 questions to help us assign scores in the passing range.

The current minimum passing score for Step 1 is 194. And while the maximum score is 300 in theory, the real world distribution goes up to around 275.

Think about that. We have ~85 questions to determine scores over around an 81 point range. That’s approximately one point per question.

Folks, this is what drives #Step1Mania.

Note, however, that the majority of Step 1 scores for U.S./Canadian students fall across a thirty point range from 220 to 250.

That means that, despite the power we give to USMLE Step 1 in residency selection, the absolute performance for most applicants is similar. In terms of raw number of questions answered, most U.S. medical student differ by fewer than 30 correctly-answered multiple choice questions. That’s around 10% of a seven hour, 280 question test administered on a single day.

And what important topics might those 30 questions test? Well, I’ve discussed that in the past.

Learning Objective: In terms of raw performance, most U.S. medical students likely differ by 30 or fewer correctly-answered questions on USMLE Step 1 (~10% of a 280 question test).

__

Question 5

A U.S. medical student takes USMLE Step 1. Her score is 191. Because the passing score is 194, she cannot seek licensure.

Which of the following reflects the probability that this examinee will pass the test if she takes it again?

A) 0%

B) 32%

C) 64%

D) 96%

–

The correct answer is C, 64%.

In 2016, 96% of first-time test takers from U.S. allopathic medical schools passed Step 1. For those who repeated the test, the pass rate was 64%. What that means is that >98% of U.S. allopathic medical students ultimately pass the exam.

I bring this up to highlight again how the Step 1 score is an estimate of knowledge at a specific point in time. And yet, we often treat Step 1 scores as if they are an immutable personality characteristic – a medical IQ, stamped on our foreheads for posterity.

But medical knowledge changes over time. I took Step 1 in 2005. If I took the test today, I would absolutely score lower than I did back then. I might even fail the test altogether.

But here’s the thing: which version of me would you want caring for your child? The 2005 version or the 2019 version?