#horace hardwick

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Bess of Hardwick: Four Times a Lady

Horace Walpole

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“You may see how happy this has made me; I look upon your Lordship as part of myself, Utrumque nostrum incredibili modo, Consentit astrum … I am, my dearest Lord,

Ever and most cordially yours,

Holles Newcastle

Written in June of 1753, this a fragment of a letter from Thomas Pelham, Duke of Newcastle and Secretary of State, to the Lord High Chancellor, his closest advisor and dearest friend Philip Yorke, Earl of Hardwicke. The piece of Latin verse which Newcastle chose to include is an extract from Book II, Poem 17 of Horace’s Odes. This particular work was addressed from Horace to his friend and patron Maecenas, and is centered around an entreaty from the poet to his friend not to die before him, as he could not bear to live without the dearest part of his soul.

#some days#I really love what I do#so much of their correspondence is like this#and it’s just the most beautiful and heart rending thing to read#all these tiny declarations of love slipped between diplomatic reports and political news and enquiries about family#it’s profoundly humanizing#especially when you know#that Hardwicke did ultimately die before Newcastle#not the stones#quotes#poetry#history#horace#Maecenas#duke of newcastle#earl of hardwicke#letters#friendship

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heaven, I'm in heaven...

Script below the break

Hello and welcome back to The Rewatch Rewind! My name is Jane, and this is the podcast where I count down my top 40 most frequently rewatched films in a 20-year period. Today I will be discussing number five on my list: RKO’s 1935 musical comedy Top Hat, directed by Mark Sandrich, written by Allan Scott and Dwight Taylor, and starring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers.

American dancer Jerry Travers (Fred Astaire) comes to London to star in a show produced by his friend Horace Hardwick (Edward Everett Horton). The night before the show opens, Jerry’s tapdancing in Horace’s hotel room awakens model Dale Tremont (Ginger Rogers) in the room below. She calls the manager to complain, who calls the room above hers, and Horace answers the phone. Because he can’t hear over Jerry’s dancing, he leaves to see what the manager wants. Tired of waiting for the noise to stop, Dale storms upstairs to confront the dancer. Upon seeing her, Jerry immediately falls in love, and the next day he starts following her around in a mildly creepy but mostly charming way. However, he never tells her his name, and when Dale learns that her friend Madge Hardwick (Helen Broderick)’s husband is staying in the room above hers, she naturally assumes that Jerry is Horace Hardwick. All of this results in much confusion, hilarity, and of course, dancing.

Top Hat was one of the many old movies that my mom introduced me to in 2002, and it has been among my favorite films ever since. I had already seen it several times before I started keeping track, and then I watched it five times in 2003, three times in 2004, three times in 2005, once in 2006, once in 2009, twice in 2010, three times in 2011, four times in 2012, once each in 2013, 2014, 2016, 2017, and 2018, twice in 2020, once in 2021, and once in 2022. This was the first Fred and Ginger movie I ever saw, and while I’ve since watched and enjoyed all nine others multiple times, none could top Top Hat, in my opinion.

This was the fourth film that Fred and Ginger made together, but only the second in which they had starring roles, and the first that was written specifically for them. Two of their previous films – 1933’s Flying Down to Rio and 1935’s Roberta – gave them relatively small parts, although their scenes were unquestionably the highlights. In Flying Down to Rio, they got fourth and fifth billing and are barely in it, but they caused a splash with their one dance number, and an iconic duo was born. They got second and third billing in Roberta, in which they basically function as the B romantic pair, with Irene Dunne and Randolph Scott as the A couple. Fred and Ginger’s first starring roles had been in 1934’s The Gay Divorcee, which was an adaptation of the Broadway musical Gay Divorce. Critics of Top Hat (including Astaire himself) complained that it was basically a rehash of The Gay Divorcee, and like, I can see their point: both films have a weird mistaken identity story and feature essentially the same cast filling very similar roles – with the notable change from Alice Brady to Helen Broderick in the “Ginger’s older relative/friend” role. But while I also enjoy The Gay Divorcee, somehow I feel like Top Hat just works better. The story makes at least a little bit more sense, and they didn’t devote a quarter of the runtime to a single interminable musical number like The Gay Divorcee did with the frickin Continental… although The Piccolino came dangerously close to replicating that. After Top Hat, Fred and Ginger made five more films with RKO in the 1930s: 1936’s Follow the Fleet, in which they were basically the B couple like they had been in Roberta, although they did get top billing in this one; 1936’s Swing Time, which is mostly very good and would probably have made it onto this podcast if not for that one blackface number; 1937’s Shall We Dance, which I kind of slept on for a while but now I think is probably my second favorite of theirs, although the ending drags a bit; 1938’s Carefree, possibly their weirdest movie, which involves hypnotism; and 1939’s The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle, which I find to be disappointingly forgettable. Then, after 10 years apart, they reunited for MGM’s The Barkleys of Broadway in 1949, which is basically Fred and Ginger fan fiction and it makes me so happy that it exists.

While there were lots of other dancing musicals being made in Hollywood around this time, the Astaire/Rogers ones feel like their own genre, and not just because of the stars. I think a big part of what makes Top Hat feel like the quintessential Fred and Ginger film is the supporting cast. Edward Everett Horton, Helen Broderick, Erik Rhodes, and Eric Blore were each in at least one other Fred and Ginger movie, but this is the only one that has all four of them. Edward Everett Horton excelled at playing the kind of guy who thinks he’s in control of every situation, but actually has no clue what’s going on, and he’s especially in his element as Horace Hardwick, convinced that he can get to the bottom of everyone’s strange behavior while never suspecting that he could end all the confusion just by meeting Dale. Helen Broderick delivers wisecracks in a brilliantly dry, cynical tone that contrasts with Horton’s bumbling to great comedic effect. Their characters don’t seem to have a very functional marriage, but they also don’t really seem to mind that. Typically the “haha, married couples hate each other” types of jokes really irritate me, but Horace and Madge are such ridiculous characters that it’s actually kind of funny when they do it. And then there’s Erik Rhodes, whose absurdly over-the-top Italian characterization in Top Hat and The Gay Divorcee so offended Mussolini that both those films were banned in Italy. Personally I feel like Top Hat’s portrayal of Venice as a giant white soundstage is probably more insulting to Italians than a guy doing a bad accent and being silly is, but I don’t know, maybe it’s still offensive. To me, as a non-Italian, I just think Erik Rhodes is very funny as Alberto Beddini, the dressmaker whose clothes Dale is modeling. He has some truly excellent lines, like, “Never again will I allow women to wear my dresses!” and “I am no man; I am Beddini!” Despite his declarations of love for Dale, he is extremely queer-coded, while also interestingly being one of the most masculine characters in the film, which is…kind of the opposite of how male characters are typically queer-coded. So Alberto is very silly but also quite fascinating. Eric Blore was in half of the Fred and Ginger movies and he’s always hilarious. In Top Hat he plays Horace’s valet, Bates, who always refer to themselves in the plural (“We are Bates, sir”), so the next time someone complains to you about this so-called newfangled trend of young people messing with pronouns, feel free to point out that at least one middle-aged man was doing that way back in 1935. One of my favorite exchanges in the movie is when Horace is trying to explain to Bates that Jerry seems to have gotten into a perilous situation with a woman by saying, “He has practically put his foot right into a hornets’ nest” and Bates respond with, “But hornets’ nests grow on trees, sir.” “Never mind that. We have got to do something.” “What about rubbing it with butter, sir?” “You blasted fool, you can’t rub a girl with butter!” “My sister got into a hornets’ nest and we rubbed HER with butter, sir!” “That’s the wrong treatment, you should have used mud – never mind that!” It has nothing to do with anything but it makes me laugh every time. This supporting cast adds a silly, somewhat Vaudevillian aspect to Top Hat that no Fred and Ginger film would be complete without.

Of course, Fred and Ginger movies are better known for a different somewhat Vaudevillian aspect: their songs. It’s very interesting to watch Top Hat from a musical history perspective because it was made before the advent of the book musical – that is, a show where the songs are fully integrated into the story and used to tell a specific narrative. The songs in this movie do sort of advance the plot, but the lyrics are generic enough that they stand alone completely out of context. It’s kind of a bridge between the disjointed songs and scenes of vaudeville and the continuously flowing story of book musicals. All the music in Top Hat was written by the legendary Irving Berlin, including two solo numbers for Fred: “No Strings (I’m Fancy Free)” which is what Jerry is dancing to in the hotel when he disturbs Dale, and “Top Hat, White Tie and Tails” which is part of his show; and three numbers for both Fred and Ginger to dance to: “Isn’t This a Lovely Day (to Be Caught in the Rain)?” for soon after they meet, before Dale thinks that Jerry is Horace, “Cheek to Cheek” when they’re in love but Dale is conflicted because she thinks he’s married to Madge, who is confusingly encouraging them to dance, and “The Piccolino” after Dale finally learns Jerry’s true identity. Both Astaire and Rogers were significantly better dancers than singers, but typically Fred did most of the singing, and the only song he doesn’t sing in Top Hat is the Piccolino, apparently because he didn’t like it, so Ginger sings it first and then an offscreen chorus repeats it. My favorite number in the film has always been “Isn’t this a Lovely Day (to Be Caught in the Rain)?” because I love the way Jerry starts dancing fancier and fancier and is pleasantly surprised that Dale can keep up with him, and it’s fun that Ginger got to wear pants for once, and I also just really enjoy that song. There was a time soon after I first fell in love with this movie when I tried to make saying the word “lovely” a lot part of my personality, mainly inspired by this song. I truly enjoy all the numbers, even if I do think The Piccolino goes on a bit too long, although, again, it’s not nearly as painfully long as The Continental in The Gay Divorcee, which it’s clearly meant to pay homage to. But Fred and Ginger’s most famous dance number – certainly in this film, and also probably in any of their films – is “Cheek to Cheek.” It is pure, breathtaking magic, and even knowing about the major drama with Ginger’s dress in no way detracts from that.

I’ve heard a few different accounts of the dress drama with slightly conflicting details, but what they all seem to agree on is that Ginger Rogers insisted that a low-backed, light blue, ostrich feather dress would look perfect during the “Cheek to Cheek” dance, and pretty much everybody else tried to talk her out of it, but she refused to back down until they were all forced to concede. And she was correct, it looks incredible, although if you’re watching closely you can see some feathers falling off while she dances, which was the main objection to the dress. Fred Astaire was reportedly extremely annoyed about the flying feathers, although he betrays none of that to the audience, and afterwards gave Ginger the nickname “Feathers,” which he continued to call her for many years. My interpretation of this is that it started as kind of an insult when he was genuinely upset about the incident but evolved to become more of a term of endearment, although obviously I don’t know for sure. As far as I can tell, apart from the occasional disagreement, Fred and Ginger got along pretty well in real life, although the studio sometimes invented or exaggerated stories about them fighting to try to generate more buzz. Personally I don’t think that was necessary; their talent spoke for itself, and audiences would have flocked to their films whether or not there was conflict offscreen.

One thing that I don’t like about old movies is that in general, most of the people who worked on them were deceased before DVDs were invented, which means that the special features are often lacking. I have watched Top Hat with commentary, but it’s by a film historian and Fred Astaire’s daughter who was born after this movie was made. It’s mostly the historian talking, but every once in a while Astaire’s daughter shares a memory of her father, and every. single. time. the historian responds with, in the most patronizing tone of voice I’ve ever heard, “Thank you for telling us that” and I hate it so much. But one thing that I did learn from the commentary that I definitely wouldn’t have noticed if nobody had told me is that Lucille Ball makes a very small appearance in this movie as a worker at the flower shop in the London hotel. She has a couple of lines, but even though I’m used to watching her in Stage Door, which was only made two years after Top Hat, I absolutely would never have recognized her. So that’s kind of fun.

Now, when it comes to watching Top Hat from an aroace perspective, even I cannot deny that this movie in general, and the “Cheek to Cheek” number specifically, is extremely romantic. The main storyline is Jerry immediately falling for Dale and flirting with her until she falls for him, and then her attempting to suppress her feelings when she thinks he’s married to her best friend. But somehow, even watching it as a young teen who had no idea that I was aroace, this felt different from other romantic films I’d seen. I remember feeling irritated the first time I read a description of Fred and Ginger’s dancing as their version of making love because “ugh, why do people have to make everything about sex?” It took me a while to realize that not only is that an apt description, but it’s also part of what drew me to them in the first place. Because despite the way the terms “making love” and “being intimate” are now used almost exclusively as synonyms for “having sex,” they don’t necessarily have to be. There are other ways of experiencing and expressing love and intimacy besides sex. It’s just that our allonormative society puts sex on such a high pedestal and portrays it as the One True Form of Intimacy that all other forms are devalued to the point that often they feel barely worth mentioning. And I do feel like when some people talk about Fred and Ginger this way, what they’re implying is “Their dances were the Hays Code era version of sex scenes.” And, granted, it’s quite possible that that was the intent. But nothing about their dancing is inherently sexual, and yet, it would be hard to deny that it’s extremely intimate. So as someone who craves non-sexual intimacy, in a world where that concept almost seems oxymoronic, it’s so encouraging to see these characters express that. Of course, I don’t want exactly what they have – for one thing, I’m a terrible dancer, despite my one year of tap lessons in 2nd grade. And for another, what they have is way too romantic for me. But although I could never have articulated this at the time, just seeing this example of extreme intimacy coming in other, non-sexual forms as a young obliviously asexual person was so important. It gave me some armor against the onslaught of allo- and amatonormative messages implying that sexual relationships are inherently more valuable and valid than any other kind of relationship. Top Hat ends with the implication that Jerry and Dale are about to get married, so I guess we’re meant to infer that their relationship will eventually become sexual, but I don’t see how anyone could watch this movie and still think that a sexless marriage consisting of dance numbers like “Cheek to Cheek” would be any less valid than a sexual marriage. Like so many of my favorite movies, it’s not exactly ace representation, but it’s easy to imagine many of the characters in Top Hat as ace, and often that’s as good as it gets.

While the subtle and probably unintentional message that sex doesn’t have to be the end all be all is great, the main reason I love this movie is because it’s just a lot of fun to watch. I’ll be the first to admit that the plot is a little ridiculous and doesn’t make a ton of sense, but I also have to admire the lengths they go to in order to maintain the mistaken identity for so long. Like the part when the London hotel manager tells Dale that Horace Hardwick is the gentleman with the briefcase and cane on the mezzanine, and Horace steps behind a chandelier before Dale can see him, and while she’s trying to get closer, Jerry runs up to Horace and says that he has a phone call, and Horace hands Jerry his briefcase and cane and rushes off, so Dale will see Jerry alone holding a briefcase and cane and therefore still think he is Horace. Or when Horace just happens to be in the bathtub when Dale comes into their room in Italy. Or how Jerry tells Madge that he’s met Dale so she doesn’t think she needs to introduce him. It’s like simultaneously the most far-fetched, bizarre plot imaginable and also kind of brilliantly executed, and I love it for that. And even if the plot doesn’t work for you, this movie is still worth watching for its truly phenomenal dancing by one of the most iconic pairs in Hollywood history.

Thank you for listening to me discuss another of my most frequently rewatched films. When compiling this list, I was very surprised to discover that Fred Astaire would only appear in one film, since I consider him one of my faves, but I hope he would at least be happy to know that that one film is in my top five. Next week, I will be talking about another Old Hollywood musical that I watched two more times than Top Hat, for a total of 33 views, which stars a man who is often compared to Fred Astaire, although I feel like, apart from being dancers, they were very different. So stay tuned for that, and as always, I will leave you with a quote from that next movie: “I make more money than…than…than Calvin Coolidge! Put together!”

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

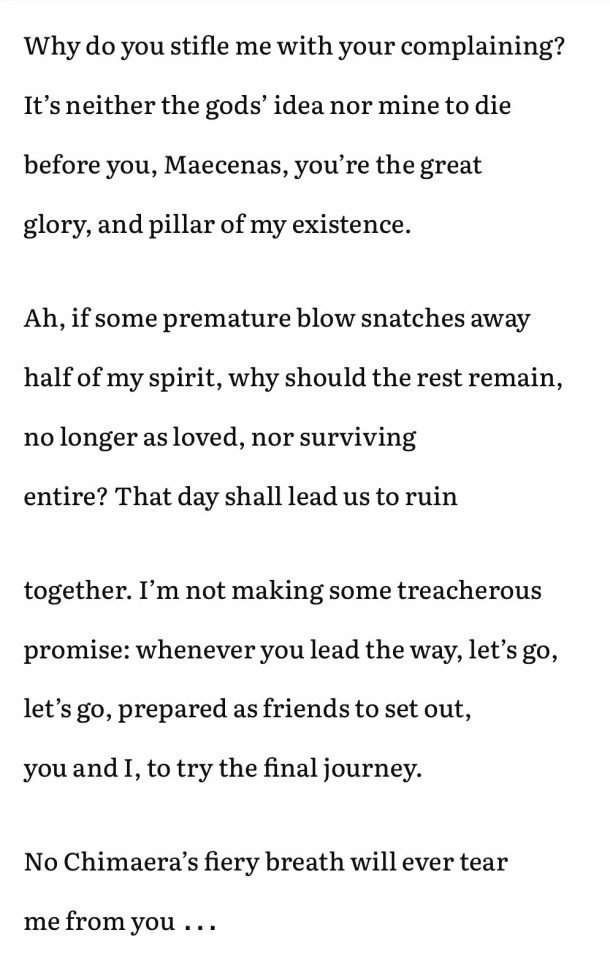

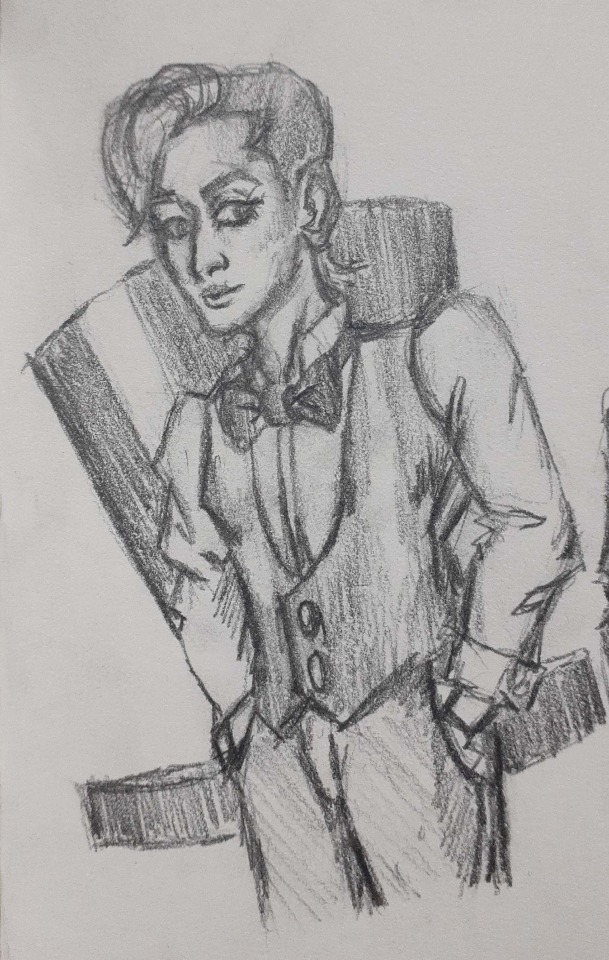

Top Hat quick Sketches! I saw the Shonichi Clips bruh, omg I just wanna see it already and Maiti on a showercap IS TOO CUTE!!!

#Takarazuka Revue#Takarazuka#Top Hat#yuzuka rei#rei yuzuka#minami maito#hoshikaze madoka#hanagumi#sketch#shonichi#jerry travers#dale tremont#horace hardwick#I’m dumping my Takarazuka Sketches here in Tumblr#AND NO WHERE ELSE#If i do get to watch it promise doing fanart fr#I mean do you see those outfits and stage design#chef's kiss#suits#showercap

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Astaire & Rogers Rewatch Part 4: Top Hat

• So we’ve reached Top Hat, which is generally everyone’s favorite including @elloette. Even many film historians say it’s the best Astaire/Rogers film. And it’s definitely one of the best but not the best imo. It does however have some of my favorite dances and songs and probably the most famous dance Astaire and Rogers ever created.

• Top Hat is kind of like a more sophisticated version of Gay Divorcee. It also has probably the best example of the Big White Set that was ubiquitous to these films. If I’m not mistaken they dyed the water black to make the set stand out more *goes to check IMDB* yep!

• Our characters/actors: Jerry Travers (Fred Astaire), Dale Tremont (Ginger Rogers), Horace Hardwick (Edward Everett Horton), Madge Hardwick (Helen Broderick), Alberto Beddini (Erik Rhodes)

• I never realized it before but Horace and his valet are like a bickering old couple. In many ways, they make far more sense as a pair than Horace and Madge.

• I’m back again to gush about Astaire’s singing. He slides effortlessly into “No Strings (I’m Fancy Free)” straight from the dialogue, and it sounds perfectly natural. Like the way hb and I integrate Parks and Rec quotes into everyday dialogue, but obviously Astaire is a bit fancier.

• His line about feeling like a sailor at sea is fitting since, in his next film, he will indeed be a sailor.

• This is a favorite solo routine for sure. He’s just so joyful and in the groove. I especially like when he taps out the beat on the side table and startles Horace with short burst of taps.

• Horace thinks he’s such hot shit that some random young woman has come to see him at his hotel late at night.

• Astaire didn’t think he was handsome and didn’t enjoy watching himself on screen, hence the grimace when he looks in the mirror, which is played for a laugh. But that opinion runs contrary to Astaire’s place as one of the leading men of Hollywood and as one part of some of the most romantic moments in film history, primarily with Rogers. It lends credence to Katharine Hepburn’s famous saying that Astaire gave Rogers “class,” and she gave him “sex” (metaphorically). He’s arguably never sexier than when dancing with Ginger Rogers.

• When Dale comes upstairs to tell him to shut up, she gives zero effs. Doesn’t care that he’s trying to be charming or funny, or that he’s sorry for waking her, or that he’s flirting with her, doesn’t care about him at all in any way. Just shut up so I can sleep, is her message.

• But then. She is charmed by his soft shoe dance on a sandy floor to lull her to sleep.

• Spotted: young Lucille Ball as the florist’s assistant. We’ll see her in the next movie too where she’ll have her first ever credited roll.

• Astaire’s face when he asks, “Don’t I even get any thanks?” is so heartfelt and open. It always makes me awwwwwwww.

• Another favorite line of dialogue from these films:

Jerry, holding an umbrella in a downpour: “May I rescue you?”

Dale, unimpressed: “No, thank you. I prefer being in distress.”

• “Isn’t it a Lovely Day?” is a flirtatious song and they act it that way but the true flirting comes in the dance, which is about partnership and equality. They imitate one another throughout the scene, starting even while Astaire is singing. Rogers puts a hand on her chest and he then does the same. They’re dressed alike as well, thanks to her riding outfit, and that furthers the theme by making her more masculine to match him but it’s also advantageous for some of the moves they’ll perform, such as when she lifts him.

• Jerry thinks he’s in control. He’s surprised, but pleased, to find Dale has gotten up and followed him as he begins to dance. He thinks he’s won her over. Then she mocks him a bit by sticking her hands in her pockets like he’s done and surprises him even more by busting out her own little extra tap. She’s telling him she’s not there just to follow his lead and any relationship between them will only work if they’re equals.

• They’re definitely testing each other in this dance, finding out if they are drift compatible. Trying this step and that to see if the other can keep up. She keeps glancing at him in a self-satisfied way. He crosses his arms to see if she’ll do the same. They circle the space mirroring each other with every movement, and while they’re in sync, it’s still like one is leading and the other is following. Until they clap in unison, skip forward, and land at the exact same time. They spin around neatly and he glances over, smiling in pleasure, and so is she.

• The first time they touch is over a minute and a half in and it’s only to lend a hand so each can twirl in turn. They glide forward and back in a wide loop as the music builds and now they’re smiling in earnest and it’s not just the characters; it’s Astaire and Rogers. He mouths something to her, maybe more than once, and they’re both clearly enjoying themselves.

• It’s only in the last 30 seconds or so that they actually touch for real, and it’s because she has crooked her arm in invitation. He spins them around the bandstand together and although it’s a fairly standard move Astaire uses a lot, because they’re both in trousers, you can see just how close they are to one another, knees and hips pressed together.

• And now they combine both elements of the dance: imitation and partnership. They move as reflections of one another and take turns lifting each other. During this portion is where you once again can see the acting stop and the actors just being themselves. As they near the end of the dance, Astaire and Rogers both grin in delight and he maybe looks especially proud of her. This was a technical dance with a lot of movement and she nails it. While her gowns often add to their duets, it’s routines like this, where she’s in trousers, that you can see her technical skill really shine.

• One of the many ways Rogers contributed to the dancing partnership was in being their “button finder,” which means she was good at figuring out how to end a scene or dance. The best example is at the end of this dance, where she came up with the idea for them to finish by having Jerry and Dale simply shake hands.

• Don’t miss the sex joke in the middle of Horace and Jerry’s argument:

Horace, who is concerned about scandal ahead of Jerry’s show: “Why, I’d rather have had it (getting slapped) happen to me than to you.”

Jerry, not missing a beat: “Oh, of course, if you enjoy that sort of thing.”

Horace: “I do, immensely… (realizing what he’s just said) Now don’t be absurd!”

• Dale’s line, “I hate men. I hate you. I hate all men!” is a mood.

• Beddini’s response, “I am no man. I am Beddini!” is how all men think of themselves.

• Interesting that all we’ve seen Dale and Jerry do is dance a very fun, flirtatious, but not necessarily romantic duet (ok, fine it was in a bandstand while it was raining which is pretty romantic but you get it), and yet she says, “How could he have made love to me when he was married all the time?” 🤔🤔🤔

Further 🤔🤔🤔🤔🤔

Horace: “You sure you didn’t forget yourself in the park?

Jerry: “Positive. If I ever forgot myself with that girl, I’d remember.”

• Seriously, there are some vibes between Horace and his valet. *gaydar pings very quietly out of earshot of the censors*

• I like Astaire’s little warm-up in his dressing room. Seems like the kind of thing he probably did irl.

• One of my absolute favorites moments is when Jerry instructs Horace to charter a plane so they can fly down to meet Dale. Horace asks, “What kind of plane?” And Jerry, already about to miss his stage cue, leans back into the doorway quickly to say, “One with wiiiings!”

• The physical “invitation” Jerry uses when singing the appropriate line in “Top Hat, White Tie and Tails” is actually Madge’s telegram about Dale. He took it on stage with him after snatching it from Horace’s hands.

• There are conflicting stories about how many canes Astaire broke while filming this sequence and which take was used. One account says he broke 12 canes in frustration while failing to get the number absolutely right and the 13th (and last cane) was used in the final take, which was then printed. But Astaire recalled that Jimmy Cagney, who was visiting the set at the time, advised him that he’d nailed it on the second take. Astaire wanted to try a couple more but the next day, agreed that Cagney was right and the second take was used.

• Shooting down his rivals with a cane and using taps for bullets was based on a gimmick Astaire had used years before in a terrible Broadway show. Here it became one of his most iconic creations. I especially like when he fires off a shot at the Horace’s stuffy club members in the audience.

• How on earth did Dale think that Jerry was married to Madge? In what world are they compatible? Granted, she hasn’t actually met Horace but still.

• While Horace is in the bathtub in his shower cap:

Horace: “Jerry! I don’t think it’s safe for you to see that girl alone.”

Jerry: “Well, I don’t think it would be quite proper for you to receive her that way.”

• In most Astaire/Rogers movies, he has a lot of bravado and pursues her but she almost always ends up shocking the hell out of him when she turns out to also be ballsy af. In Gay Divorcee, she invited him to her room. In Top Hat, she comes up to see him alone and then kisses him.

Hardly a romantic kiss btw. But we still aren’t to the place where we talk about the lack of kisses in this film series.

• Aaaaaand again, Astaire’s singing is so perfect for this song. He leads straight from conversation into the lyrics. The music has already been playing in the background, and he makes it appear he’s created the lyrics of “Cheek to Cheek” just for her in this moment.

• Rogers does a magnificent job of softening when he starts to sing. Her eyes flick up and down his face, touched that he’s serenading her. And when Astaire drops his tone on the word “seek,” his gaze is heated for a just a moment and her lips quirk a little. Being sung to is awkward but she makes it seem like the most romantic thing.

• Like in “Night in Day” in Gay Divorcee, this dance is about seduction but its more developed than in the prior film. Because the characters have already danced together, elements of “Isn’t it a Lovely Day?” seep in, such as the short tap routine they do side by side. Instead of getting her to simply give in to him, he is asking her to trust him, to remember the equality and partnership they’d built before. He almost never takes his eyes off her for the entire dance, even watching her out of the corner of his eye when they’re side by side.

• I would say most of this dance falls into the ��acting” category but there are a couple Astaire and Rogers moments that peek through. After the first time he leans her back and them brings them together so their faces are close, he smiles privately to her. After their little tap section, he swings her back into his arms and they’re both smiling in delight.

• A few times the only place they’re touching is his hand on her back and there’s something very Victorian hot about that.

• I’ve always liked the moment where she twirls and he waits, hand outstretched, expression openly adoring, until she takes his hand without looking and they’re in sync again.

• Another callback to “Isn’t it a Lovely Day?”: In that dance, she crooked her arm in invitation to him. Here, she leaves her arm up so he can wrap it around his neck.

• Several times he leans her back, each time dipping her a little further and keeping her there a little longer, but never failing to hold her and bring her up. Each time showing her she can trust him. When they reach the climax, she bends back completely and he holds her for several looooong seconds before very slowly returning her to her feet. Complete surrender and trust from them both. And after that moment, there is no need for anything else to cement their relationship. He can simply bring them cheek to cheek.

• Something that is evident in most of his partnered dances but perhaps most obvious in a duet like this with Rogers is that Astaire was very good about making his partner the central focus. Your eyes instinctively watch Rogers, not him, throughout the performance. But credit must also be given to Rogers herself for commanding the screen so thoroughly not solely because of her elegant dancing and gorgeous gown but because she remembers to keep acting the entire time. We never doubt that Dale is falling in love with Jerry through this dance.

• Sooo the feather dress. So much to say, some of which you may already know:

The short story is, as soon as they started filming the dance, the feathers on the dress flew everywhere. No one wanted that dress to be used, except Ginger Rogers, and she refused to wear something else.

Director Mark Sandrich, who was a dick to Rogers all the time, wanted her to wear a gown from Gay Divorcee. She told him to GTFO. Then she called her badass mom who came to the set to also tell him to GTFO.

Because they could be little shits, Astaire and Hermes Pan made up lyrics mocking the dress, set to the tune of "Cheek to Cheek.” They went, "Feathers, I hate feathers, And I hate them so that I can hardly speak, And I never find the happiness I seek, With those chicken feathers dancing cheek to cheek."

Rogers was pissed, not in the least because she had designed the dress herself and also they were ostrich feathers tyvm. Tbh it does look pretty magnificent in the final edit of the film… but that was after every single feather had been hand sewn into place. And you can still see some of them float off.

In their next film, Astaire is going to get whacked in the face by the heavy, beaded sleeve of Rogers’ dress so he really had it easy here.

He also knew he’d gone too far in poking fun at her dress and generally being an ass about the entire situation. Astaire apologized to Rogers by giving her a gold feather for her charm bracelet and affectionately calling her “Feathers” in the accompanying note (“Dear Feathers, I love ya! -Fred”). The nickname stuck. Later, he would also give her a beautiful travel watch that was housed in a golden envelope. Engraved on the outside of the envelope in Astaire’s writing? “By Hand/To Feathers/All best love -Fred.”

• The dress is absolutely essential to the dreamy quality of this dance. It makes her look like she’s floating along, caught up in being in love and in his arms. She even seems to come out of a daydream once they’ve finished dancing.

• The plot and dialogue jump through so many hoops to avoid Madge ever once saying, “my husband’s friend, Jerry,” which would clear up everything instantly.

• Interesting that when Dale reminisces sadly about her love for Jerry, whom she doesn’t think she can actually be with, the tune that plays is “Isn’t it a Lovely Day?” and not “Cheek to Cheek.” High romance is lovely but sometimes nothing beats being able to laugh and have fun together.

• Horace and Jerry have been sharing the bridal suite, as it was the only room available when they arrived. But now that Dale has impulsively agreed to marry Beddini, the management asks if Jerry and Horace would be wiling to give up the suite in exchange for a different room.

Jerry: “Well, we’ve hardly settled in it yet… Have we, angel?”

Horace: “No, and all our clothes are...(realizing Jerry is teasing him) Oh, please.”

• Upon finally realizing what’s actually been going on with Dale:

Jerry: “She’s been mistaking me for Horace all this time.”

Madge: “No wonder she thought Horace was fascinating.”

Horace: “Heh, no wonder. (then immediately) I resent that.”

• Perhaps poking fun at the way dances had been filmed until he took charge, Astaire and Rogers’ portion of “The Piccolino” starts with a close up of their feet. But instead of then cutting to a full body shot, the shot widens to show them and the dance continues all in one take.

• This may be a strange place to talk about how right Astaire and Rogers look together but I’m gonna do it anyway. Their heights are very complimentary and they move like extensions of one another. The routine is quick and bouncy, incorporating several styles and switching between them rapidly. Throughout, Astaire and Rogers elevate one another with their individual grace and skill. That element is only going to continue to grow in the next couple of films.

• At one point he whips around to pull her in so they can spin like they did in the bandstand. As she waits for him, Rogers’ face lights up and they go into the move smiling wide. Soon after, Astaire playfully raises his eyebrows to her. At another point, they step forward slowly, eyes on each other, and there’s a glimpse of that private world they sometimes slip into during their dances. The whole time, they’re absolutely flawless.

• It wouldn’t have made sense to record the taps, etc live like “I’ll Be Hard to Handle” in Roberta but I wonder what might’ve been picked if they had. Aside from when they clap and there’s no sound, Astaire says something to her when they’re dancing in a circle facing each other. She definitely seems to be giggling at several points.

• When the music kicks up and they go into an energetic section, he bows and flourishes his hand to her, once again making her the main focus.

• While filming the final scene of the movie, Sandrich (the director) wanted the duo to do a short ending dance and he told them this on the day of filming. Astaire and Rogers were peeved. Every bit of dancing, no matter how small, was always rehearsed. But Sandrich, who, again, was a dick, insisted. According to Rogers, she privately told Astaire to simply move her about however he wanted and she would follow along. In all likelihood, they probably did whip up this little dance and rehearse it quickly but you’d never know it wasn’t planned ahead of time.

She obviously had a lot of trust in his ability to lead them both but she also knew he was an excellent social dancer, meaning he didn’t necessarily need a pre-rehearsed routine. And she knew this because they’d gone dancing back in New York when they were dating.

• Here’s a cool behind the scenes picture from The Academy’s archive taken during the final scene.

• And so we’ve finished Top Hat, another glamorous adventure for Astaire and Rogers. Up is a more working class outing: Follow the Fleet.

#fred astaire#ginger rogers#top hat#classic hollywood#old hollywood#astaire and rogers rewatch#fred and ginger#any gifs without credit are mine#bc sometimes i just need a specific gif#and no one else has done it or i can't find it#so you're welcome to the three people reading these posts

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

EDWARD EVERETT HORTON

March 18, 1886

Edward Everett Horton was born in Brooklyn, New York. He began his stage career in 1906, singing and dancing and playing small parts in vaudeville and in Broadway productions. In 1919, he moved to Los Angeles, California, where he began acting in Hollywood films.

During his long career, he was in five Oscar Best Picture nominees: The Front Page (1931), The Gay Divorcee (1934), Top Hat (1935), Lost Horizon (1937) and Here Comes Mr. Jordan (1941).

His first role was in the silent comedy Too Much Business (1922).

He made his television debut playing Sheridan Whiteside in a 1949 CBS TV production of “The Man Who Came To Dinner” as part of “Ford Theatre Hour.” Lucy’s friend Mary Wickes reprised the role of Nurse Preen, a role she originated on stage and also played in the film version.

His first collaboration with Lucille Ball was Top Hat in 1935. Horton played Horace Hardwick while Ball was uncredited as a flower seller.

They also did the 1939 Kay Kayser film That’s Right - You’re Wrong, in which Horton played screenwriter Tom Village and Ball played Sandra Sand.

Their last feature film together was Her Husband’s Affairs in 1949. Horton played J.B. Cruikshank, and Ball was Margaret Weldon.

Ball asked Horton to appear opposite Bea Benadaret on the “I Love Lucy” episode “Lucy Plays Cupid” (ILL S1;E15 ) filmed on December 13, 1951 and first aired on January 21, 1952.

Lucy plays matchmaker between an elderly spinster (Benadaret) and Mr. Ritter, the butcher, who thinks that it is Lucy who is romantically interested in him!

In 1965 he played the recurring role of Chief Roaring Chicken on "F Troop” and the following year played Chief Screaming Chicken on "Batman.” He is probably best remembered as the narrator of Rocky and Bullwinkle’s "Fractured Fairy Tales” (1959-61).

Horton’s final screen appearance was posthumously in the film Cold Turkey in 1971, released posthumously. Horton died on September 29, 1970 at at 84.

#Edward Everett Horton#Lucille Ball#I Love Lucy#Top Hat#Her Husband's Affairs#That's Right - You're Wrong#Batman#Egghead#Vincent Price#Cold Turkey#Bob Newhart

0 notes

Text

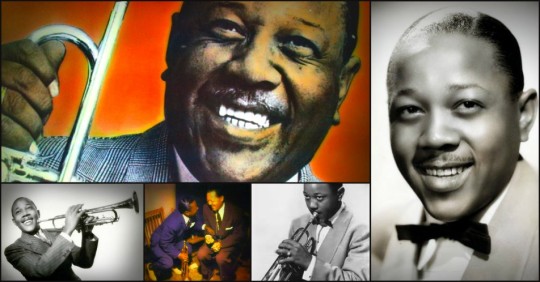

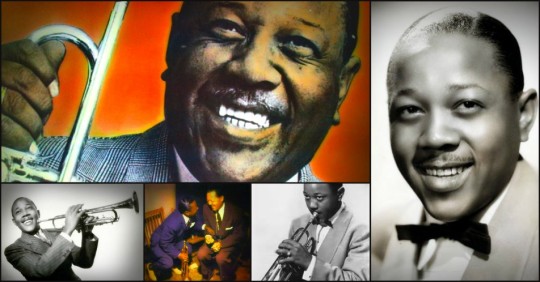

Roy Eldridge

David Roy Eldridge (January 30, 1911 – February 26, 1989), commonly known as Roy Eldridge, and nicknamed "Little Jazz", was an American jazz trumpet player. His sophisticated use of harmony, including the use of tritone substitutions, his virtuosic solos exhibiting a departure from the smooth and lyrical style of earlier jazz trumpet innovator Louis Armstrong, and his strong impact on Dizzy Gillespie mark him as one of the most influential musicians of the swing era and a precursor of bebop.

Early life

Eldridge was born on the North Side of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on January 30, 1911, to parents Alexander, a carpenter, and Blanche, a gifted pianist with a talent for reproducing music by ear, a trait that Eldridge claimed to have inherited from her. Eldridge began playing the piano at the age of five; he claims to have been able to play coherent blues licks at even this young age. The young Eldridge looked up to his older brother, Joe Eldridge (born Joseph Eldridge, 1908, North Side of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania died 5 March 1952), particularly because of Joe's diverse musical talents on the violin, alto saxophone, and clarinet. Roy took up the drums at the age of six, taking lessons and playing locally. Joe recognized his brother's natural talent on the bugle, which Roy played in a local church band, and tried to convince Roy to play the valved trumpet. When Roy began to play drums in his brother's band, Joe soon convinced him to pick up the trumpet, but Roy made little effort to gain proficiency on the instrument at first. It was not until the death of their mother, when Roy was eleven, and his father's subsequent remarriage that Roy began practicing more rigorously, locking himself in his room for hours, and particularly honing the instrument's upper register. From an early age, Roy lacked proficiency at sight-reading, a gap in his musical education that would affect him for much of his early career, but he could replicate melodies by ear very effectively.

Career

Early career and traveling bands

Eldridge led and played in a number of bands during his early years, moving extensively throughout the American Midwest. He absorbed the influence of saxophonists Benny Carter and Coleman Hawkins, setting himself the task of learning Hawkins's 1926 solo on "The Stampede" (by Fletcher Henderson's Orchestra) in developing an equivalent trumpet style.

Eldridge left home after being expelled from high school in ninth grade, joining a traveling show at the age of sixteen; the show soon folded, however, and he was left in Youngstown, Ohio. He was then picked up by the "Greater Sheesley Carnival," but returned to Pittsburgh after witnessing acts of racism in Cumberland, Maryland that significantly disturbed him. Eldridge soon found work leading a small band in the traveling "Rock Dinah" show, his performance therein leading swing-era bandleader Count Basie to recall young Roy Eldridge as "the greatest trumpet I'd ever heard in my life." Eldridge continued playing with similar traveling groups until returning home to Pittsburgh at the age of 17.

At the age of 20, Eldridge led a band in Pittsburgh, billed as "Roy Elliott and his Palais Royal Orchestra", the agent intentionally changing Eldridge's name because "he thought it more classy." Roy left this position to try out for the orchestra of Horace Henderson, younger brother of famed New York City bandleader Fletcher Henderson, and joined the ensemble, generally referred to as The Fletcher Henderson Stompers, Under the Direction of Horace Henderson. Eldridge then played with a number of other territory bands, staying for a short while in Detroit before joining Speed Webb's band which, having garnered a degree of movie publicity, began a tour of the Midwest. Many of the members of Webb's band, annoyed by the leader's lack of dedication, left to form a practically identical group with Eldridge as bandleader. The ensemble was short-lived, and Eldridge soon moved to Milwaukee, where he took part in a celebrated cutting contest with trumpet player Cladys "Jabbo" Smith, with whom he later became good friends.

New York and Chicago

Eldridge moved to New York in November 1930, playing in various bands in the early 1930s, including a number of Harlem dance bands with Cecil Scott, Elmer Snowden, Charlie Johnson, and Teddy Hill. It was during this time that Eldridge received his nickname, 'Little Jazz', from Ellington saxophonist Otto Hardwick, who was amused by the incongruity between Eldridge's raucous playing and his short stature. At this time, Eldridge was also making records and radio broadcasts under his own name. He laid down his first recorded solos with Teddy Hill in 1935, which gained almost immediate popularity. For a brief time, he also led his own band at the reputed Famous Door nightclub. Eldridge recorded a number of small group sides with singer Billie Holiday in July 1935, including "What a Little Moonlight Can Do" and "Miss Brown to You", employing a Dixieland-influenced improvisation style. In October 1935, Eldridge joined Fletcher Henderson's Orchestra, playing lead trumpet and occasionally singing. Until he left the group in early September 1936, Eldridge was Henderson's featured soloist, his talent highlighted by such numbers as "Christopher Columbus" and "Blue Lou." His rhythmic power to swing a band was a dynamic trademark of the jazz of the time. It has been said that "from the mid-Thirties onwards, he had superseded Louis Armstrong as the exemplar of modern 'hot' trumpet playing".

In the fall of 1936, Eldridge moved to Chicago to form an octet with older brother Joe Eldridge playing saxophone and arranging. The ensemble boasted nightly broadcasts and made recordings that featured his extended solos, including "After You've Gone" and "Wabash Stomp." Eldridge, fed up with the racism he had encountered in the music industry, quit playing in 1938 to study radio engineering. He was back to playing in 1939, when he formed a ten-piece band that gained a residency at New York's Arcadia Ballroom.

With Gene Krupa's Orchestra

In April 1941, after receiving many offers from white swing bands, Eldridge joined Gene Krupa's Orchestra, and was successfully featured with rookie singer Anita O'Day. In accepting this position, Eldridge became one of the first black musicians to become a permanent member of a white big band. Eldridge was instrumental in changing the course of Krupa's big band from schmaltz to jazz. The group's cover of Jimmy Dorsey's "Green Eyes," previously an entirely orchestral work, was transformed into jazz via Eldridge's playing; critic Dave Oliphant notes that Eldridge "lift[ed]" the tune "to a higher level of intensity." Eldridge and O'Day were featured in a number of recordings, including the novelty hit "Let Me Off Uptown" and "Knock Me a Kiss".

One of Eldridge's best known recorded solos is on a rendition of Hoagy Carmichael's tune, "Rockin' Chair", arranged by Benny Carter as something like a concerto for Eldridge. Jazz historian Gunther Schuller referred to Eldridge's solo on "Rockin' Chair" as "a strong and at times tremendously moving performance," although he disapproved of the "opening and closing cadenzas, the latter unforgivably aping the corniest of operatic cadenza traditions." Critic and author Dave Oliphant describes Eldridge's unique tone on "Rockin' Chair" as "a raspy, buzzy tone, which enormously heightens his playing's intensity, emotionally and dynamically" and writes that it "was also meant to hurt a little, to be disturbing, to express unfathomable stress."

After complaints from Eldridge that O'Day was upstaging him, the band broke up when Krupa was jailed for marijuana possession in July 1943.

Touring, freelancing, and small group work

After leaving Krupa's band, Eldridge freelanced in New York during 1943 before joining Artie Shaw's band in 1944. Owing to racial incidents that he faced while playing in Shaw's band, he left to form a big band, but this eventually proved financially unsuccessful, and Eldridge returned to small group work.

In the postwar years, he became part of the group which toured under the Jazz at the Philharmonic banner. and became one of the stalwarts of the tours. The JATP's organiser Norman Granz said that Roy Eldridge typified the spirit of jazz. "Every time he's on he does the best he can, no matter what the conditions are. And Roy is so intense about everything, so that it's far more important to him to dare, to try to achieve a particular peak, even if he falls on his ass in the attempt, than it is to play safe. That's what jazz is all about."

Eldridge moved to Paris in 1950 while on tour with Benny Goodman, before returning to New York in 1951 to lead a band at the Birdland jazz club. He additionally performed from 1952 until the early 1960s in small groups with Coleman Hawkins, Ella Fitzgerald and Earl Hines among others, and also began to record for Granz at this time. Eldridge also toured with Ella Fitzgerald from late 1963 until March 1965 and with Count Basie from July until September 1966 before returning to freelance playing and touring at festivals.

In 1960, Eldridge participated, alongside Abbey Lincoln, Charles Mingus, Eric Dolphy, Kenny Dorham and others, in recordings by the Jazz Artist's Guild, a short-lived grouping formed by Mingus and Max Roach as a reaction to the perceived commercialism of the Newport Festival. These resulted in the Newport Jazz Rebels LP.

Racial barriers

As the featured soloist in Artie Shaw and Gene Krupa's bands, Eldridge was something of an exception, as black musicians in the 1930s were not allowed to appear in public with white bands. Artie Shaw commented on the difficulty Roy had in his band, noting that "Droves of people would ask him for his autograph at the end of the night, but later, on the bus, he wouldn't be able to get off and buy a hamburger with the guys in the band." Krupa, on at least one occasion, spent several hours in jail and paid fines for starting a fistfight with a restaurant manager who refused to let Eldridge eat with the rest of the band.

Late life

Eldridge became the leader of the house band at Jimmy Ryan's jazz club on Manhattan's West 54th Street for several years, beginning in 1969. Although Ryan's was primarily a Dixieland venue, Eldridge tried to combine the traditional Dixieland style with his own more brash and speedy playing. Eldridge was incapacitated by a stroke in 1970, but continued to lead the group at Ryan's soon after and performing occasionally as a singer, drummer and pianist. Writer Michael Zirpolo, seeing Eldridge at Ryan's in the late 1970s, noted, "I was amazed that he still could pop out those piercing high notes, but he did, with frequency....I worried about his health, because the veins at his temples would bulge alarmingly." As leader at Ryan's, Eldridge was noted for his occasional hijinx, including impromptu "amateur night" sessions during which he'd invite inexperienced players on stage to lead his band, often for comedic effect and to give himself a break. In 1971, Eldridge was inducted into the Down Beat Jazz Hall of Fame.

After suffering a heart attack in 1980, Eldridge gave up playing. He died at the age of 78 at the Franklin General Hospital in Valley Stream, New York, three weeks after the death of his wife, Viola.

Music

Influences

According to Roy, his first major influence on the trumpet was Rex Stewart, who played in a band with young Roy and his brother Joe in Pittsburgh. But unlike many trumpet players, the young Eldridge did not derive most of his inspiration from other trumpeters, but from saxophonists. Roy first developed his solo style by playing along to recordings of Coleman Hawkins and Benny Carter, and later said that, after hearing these musicians, "I resolved to play my trumpet like a sax." Following these musicians was evidently beneficial to Roy, who got one of his first jobs by auditioning with an imitation of Coleman Hawkin's solo on Fletcher Henderson's "Stampede" of 1926. Eldridge additionally purports to have studied the styles of white cornettist Loring "Red" Nichols and Theodore "Cuban" Bennett, whose style was also very much influenced by the saxophone. Eldridge, by his own report, was not significantly influenced by trumpeter Louis Armstrong during his early years, but did undertake a major study of Armstrong's style in 1932.

Style

Eldridge was very versatile on his horn, not only quick and articulate with the low to middle registers, but the high registers as well; jazz critic Gary Giddins described Eldridge as having a "flashy, passionate, many-noted style that rampaged freely through three octaves, rich with harmonic ideas impervious to the fastest tempos." Eldridge is frequently grouped among those jazz trumpeters of the '30s and '40s, including Red Allen, Hot Lips Page, Shad Collins, and Rex Stewart who eschewed Louis Armstrong's lyrical style for a rougher and more frantic style. Of these players, critic Gary Giddins names Eldridge "the most emotionally compelling, versatile, rugged, and far-reaching." Eldridge was also lauded for the intensity of his playing; Ella Fitzgerald once said: "He's got more soul in one note that a lot of people could get into the whole song." The high register lines that Eldridge employed were one of many prominent features of his playing, and Eldridge expressed a penchant for the expressive ability of the instrument's highest notes, frequently incorporating them into his solos. Eldridge was also known for his fast style of playing, often executing blasts of rapid double-time notes followed by a return to standard time. His rapid-fire style was noted by jazz trumpeter Bill Coleman when Roy was as young as seventeen; when asked by Coleman how he achieved his speed, Eldridge replied: "Well, I've taken the tops off my valves and now they really fly." Eldridge attributes these virtuosic elements of his style to a rigorous practice regime, particularly as a teen: "I used to spend eight, nine hours a day practicing every day." Critic J. Bradford Robinson sums up his style of playing as exhibiting "a keen awareness of harmony, an unprecedented dexterity, particularly in the highest register, and a full, slightly overblown timbre, which crackled at moments of high tension." Giddins also notes that Eldridge "never had a pure or golden tone; his sound was always underscored by a vocal rasp, an urgent, human roughness."

As for Eldridge's singing style, jazz critic Whitney Balliett describes Eldridge as "a fine, scampish jazz singer, with a light, hoarse voice and a highly rhythmic attack," comparing him to American jazz trumpeter and vocalist Hot Lips Page.

Musical impact

Eldridge's fast playing and extensive development of the instrument's upper register were heavy influences on Dizzy Gillespie, who, along with Charlie Parker, brought bebop into existence. Tracks such as "Heckler's Hop," from Eldridge's small group recordings with alto saxophonist and clarinettist Scoops Carry, in which Eldridge's use of the high register is particularly emphasized, were especially influential for Dizzy. Dizzy got the chance to engage in numerous jam sessions and "trumpet battles" with Eldridge at New York's Minton's Playhouse in the early 1940s. Referring to Eldridge, Dizzy went so far as to say: "He was the Messiah of our generation." Eldridge first heard Dizzy on bandleader Lionel Hampton's 1939 recording of "Hot Mallets," and later recalled: "I heard this trumpet solo and I thought it was me. Then I found out it was Dizzy." A careful listening to bebop standards, such as the song "Bebop", reveals how much Eldridge influenced this genre of jazz. Eldridge also claimed that he was not impressed with Dizzy's bop solo style, saying once to bebop trumpeter Howard McGhee after jamming with Dizzy at the Heat Wave club in Harlem: "I don't dig it...I really don't understand him." Although frequently touted as the bridge between Louis Armstrong and Dizzy Gillespie, Eldridge always insisted: "I was never trying to be a bridge between Armstrong and something."

Other significant musicians influenced by Roy Eldridge include Shorty Sherock of the Bob Crosby Orchestra, and bebop pioneers Howard McGhee and Fats Navarro.

Personality

Eldridge was famously considered competitive by those who knew him with pianist Chuck Folds saying: "I can't imagine anyone more competitive than he [Roy] was in the 1970s. I've never met anyone scrappier than Roy, ever, ever, ever." Eldridge fully admitted to his competitive spirit, saying "I was just trying to outplay anybody, and to outplay them my way." Jazz trumpeter Jonah Jones reports that Eldridge's willingness to "go anywhere and play against anyone" even led to a cutting contest with his own hero, Rex Stewart. Roy could also become antagonistic, particularly in the face of those he deemed racist. Many noted Roy's constant restlessness with saxophonist Billie Bowen noting that Roy "could never, even as a youngster, sit down for more than a few minutes, he was always restless." Eldridge is also said to have suffered from sporadic stage fright. He occasionally found himself in trouble with women which included an incident that involved his being forced to sell his trumpet temporarily in order to reclaim a portion of the money that had been stolen from him by a woman with whom he had drunkenly spent the night. That women's name was Rose M. Harris. It was later found that they shared a child whose name was Timothy P. Eldridge. Timothy had a daughter named Tiana M. Eldridge. Roy is also said to have developed a fiery temper later in life according to clarinettist Joe Muranyi. Muranyi worked with Eldridge at Ryan's and has called Elridge's temper "Mt. Vesuvius to the fifth power."

Partial discography

The Big Band of Little Jazz (Topaz, 1935–45) with Dickie Wells, Benny Goodman, Benny Carter, Teddy Wilson, Gene Krupa, John Kirby

After You've Gone (Decca Records/GRP, 1936–46) with Ike Quebec, Cecil Payne, Billy Taylor, Sahib Shihab, Wilbur De Paris

Heckler's Hop (Hep, 1936–1939) with Gene Krupa, Benny Goodman, Helen Ward

Roy Eldridge 1943–1944 (Classics); 1945–1947 (Classics)

Nuts (Disques Vogue, 1950) with Zoot Sims, Dick Hyman, Pierre Michelot

French Cooking (Vogue, 1950–51) with Raymond Fol, Barney Spieler

Rockin' Chair (Clef, 1951–52, [1955])

Dale's Wail (Clef, 1953, [1955])

Little Jazz (Clef, 1954)

Roy and Diz (Clef, 1954) with Dizzy Gillespie

Swingin' on the Town (Verve, 1960)

The Nifty Cat (New World) with Budd Johnson, Benny Morton, Nat Pierce

Oscar Peterson and Roy Eldridge

Roy Eldridge in Paris (Vogue, 1950/51)

Roy's Got Rhythm (EmArcy, 1951)

Little Jazz (1957; 7"; EmArcy [Mercury] EP-1-6022) (plus Charlie Shavers, Joe Thomas, Jonah Jones & Emmett Berry) (prebop jazz/swing style)

The Coleman Hawkins, Roy Eldridge, Pete Brown, Jo Jones All Stars at Newport (Verve, 1957)

The Complete Verve Roy Eldridge Studio Sessions by Roy Eldridge (Verve-Kompilation)

"Newport Rebels" (Candid CJM 8022, 1960)

The Trumpet Kings Meet Joe Turner (Pablo, 1974) with Big Joe Turner, Dizzy Gillespie, Harry "Sweets" Edison and Clark Terry

Roy Eldridge and Oscar Peterson (OJC, 1974) Duo-Aufnahmen

Little Jazz and the Jimmy Ryan All-Stars (Pablo, 1975) with Dick Katz, Major Holley

Happy Time (Pablo, 1975)

Jazz Maturity...Where It's Coming From (Pablo, 1975)

Oscar Peterson and The Trumpet Kings - Jousts (Pablo, 1975)

The Trumpet Kings at Montreux '75 (Pablo) with Dizzy Gillespie, Clark Terry

The Tatum Group Masterpieces with Art Tatum, John Simmons (bass), Alvin Stoller (drums) (1955, Pablo 1975)

What is All About (OJC, 1976) with Milt Jackson, Budd Johnson

Montreux 1977 (Pablo; OJC, 1977) with Oscar Peterson, Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen, Bobby Durham

Roy Eldridge & Vic Dickenson (Storyville Records, 1978) with Tommy Flanagan

Heckler's Hop (Hep Records, 1995)

As sideman

With Count Basie

Count Basie at Newport (Verve, 1957)

Basie Swingin' Voices Singin' (ABC-Paramount, 1966)

Broadway Basie's...Way (Command, 1966)

With Ella Fitzgerald

Ella at Juan-Les-Pins (Verve, 1964)

With Johnny Hodges

Blues-a-Plenty (Verve, 1958)

Not So Dukish (Verve, 1958)

With Illinois Jacquet

Swing's the Thing (Clef, 1956)

With Gene Krupa and Buddy Rich

The Drum Battle (Verve, 1952 [1960])

With Ben Webster

Ben Webster and Associates (Verve, 1959)

With Lester Young

Laughin' to Keep from Cryin' (Verve, 1958)

Wikipedia

1 note

·

View note

Text

7 MUSICALES PARA VER ANTES O DESPUÉS DE "LA LA LAND" Y COMPLEMENTAR LA EXPERIENCIA CINEMATOGRÁFICA.

#1 LOS PARAGUAS DE CHERBURGO Les Parapluies de Cherbourg | 1964 | Dir. Jacques Demy Formalmente muy diferente al trabajo de su colegas de la Nouvelle Vague, Jacques Demy experimentaba a mediados de la década de los 60s con el género musical con composiciones de Michel Legrand, y abordando temas como el destino y el amor truncado nos regaló este sensacional y revolucionario filme de culto ganador de la Palma de Oro y nominado como Mejor Película Extranjera en los premios Oscar y Golden Globes. Rozando peligrosamente la cursilería y presentada en tres capítulos -la partida, la ausencia y el regreso-, "Les Parapluies de Cherbourg" nos adentra en la intensa y agridulce historia de amor de Geneviève Emery (Catherine Deneuve), una joven que ayuda a su madre en su tienda de paraguas en Cherburgo y que está perdidamente enamorada de Guy Foucher (Nino Castelnuovo), un joven mecánico con el que piensa contraer matrimonio a pesar de la oposición de su progenitora, quien considera al chico demasiado pobre, y a su hija, demasiado joven: además, las cosas se complican cuando Guy tiene que abandonar el país para hacer el servicio militar en Argelia durante dos años y Rolando, un rico joyero, se enamora de Geneviève.

#2 CANTANDO BAJO LA LLUVIA Singing In The Rain | 1952 | Dir. Stanley Donen y Gene Kelly Considerado por muchos como el mejor filme musical de la historia del séptimo arte, y poseedora de algunas de las secuencias más maravillosas del cine mundial, "Cantando bajo la lluvia" es una obra cumbre de la era dorada del género musical en Hollywood. La película retrata el cambio del cine silente al cine sonoro desde la perspectiva de quienes se encontraban frente a las cámaras: Don Lockwood (el inigualable Gene Kelly) es un ídolo del cine mudo y, junto con Lina Lamont (Jean Hagen), forman la pareja del momento en el cine silente. Sin embargo, la llegada del cine sonoro sacude la industria cinematográfica y la novedad técnica tiene al público ávido de descubrir la verdadera voz de sus estrellas favoritas; el problema surge cuando Lina Lamont posee una voz para nada atractiva, y además, Don se enamora perdidamente de Kathy Selden (la recientemente fallecida Debbie Reynolds) una prometedora aspirante a actriz.

#3 SOMBRERO DE COPA Top Hat | 1935 | Dir. Mark Sandrich Protagonizada por los astros Fred Astaire y Ginger Rogers, este musical se centra en Jerry Travers (Astaire), un famoso cómico musical estadounidense que, tras llegar a Londres e instalarse en la habitación de Horace Hardwick, productor de su obra, conoce a una bella modelo llamada Dale Termont (Rogers), quien se aloja en el piso de abajo y lo confunde con el productor Hardwick; al enterarse de que está casado, ella le rechaza y acepta la invitación de su jefe, el modisto Alberto Beddini, para viajar a Venecia donde, despechada, aceptará casarse con él. El carisma de la pareja protagónica y el excepcional guión que con astucia configura esta trama de enredos con comentarios sobre el Sueño Americano y la Gran Depresión en medio de sorprendentes números musicales compuestos y escritos por Irving Berlin, hacen de "Top Hat" una cinta indispensable para todos los amantes del cine.

#4 SINFONÍA DE PARÍS An American In Paris | 1951 | Dir. Vincente Minnelli Uno de los expertos en cine musical escribió con imágenes una carta de amor a París y a la vida con una optimista, colorida y romántica historia tan previsible como disfrutable que terminó por llevarse seis premios de la Academia, incluyendo el de Mejor Película. Un fenomenal diseño de arte con inspiración en el arte de Toulouse Lutrec y Rousseau, las sorprendentes composiciones musicales de George Gershwin y unas sensacionales coreografías fueron los ingredientes principales en la fórmula exitosa que dio forma a la historia de Jerry Mulligan (Gene Kelly tan sólo un año antes de filmar la emblemática "Singing in the Rain"), un pintor americano que, tras la Segunda Guerra Mundial, decide establecerse en la capital francesa para probar suerte y exponer sus cuadros en Montparnasse, y aunque tiene poca suerte con la venta de sus obras, conoce a una mujer millonaria que se ofrece a promocionar su trabajo a la vez que conoce y se enamora de una chica que trabaja en una perfumería.

#5 TODOS DICEN QUE TE AMO Everyone says I love you | 1996 | Dir. Woody Allen El eterno inconforme y perpetuamente angustiado Woody Allen nos presenta sus comentarios, políticos, religiosos y sexuales a través de un homenaje al género escapando de los lugares comunes del cine musical y con múltiples referencias a los clásicos del celuloide. En "Todos dicen que te amo" Allen mantiene su esencia formal europea y pone a todo su elenco a cantar -incluso él tiene un particular número musical- para presentar los problemas de una variopinta galería de personajes que encuentran un punto de conexión en el matrimonio neoyorquino formado por Steffi (Goldie Hawn) y Bob (Alan Alda). Esta sensacional película que combina magistralmente la música, el humor y el drama para retratar a esta burguesa familia disfuncional que se pasea no sólo por la Gran Manzana sino también por París y Venecia, y presentada bajo la formalidad melancólica por el cine de oro de Hollywood.

#6 EL CANTANTE DE JAZZ The Jazz Singer | 1927 | Dir. Alan Crosland Jakie Rabinowitz (Al Jolson) es joven judío que ha sido estrictamente educado por su padre para que, a la muerte de éste, sea su reemplazo en la sinagoga del gueto judío donde vive con su familia en la ciudad de Nueva York. Sin embargo, él no está interesado en seguir los pasos de su padre y, por el contrario, se siente fuertemente atraído hacia la música jazz, por lo que decide convertirse en cantante bajo el pseudónimo de Jack Robin, hacia lo cual su padre siente un fuerte rechazo. Se trata, ni más ni menos, que del primer filme sonoro de la historia del cine. Bajo la producción de Warner Bros. Pictures -estudio que entonces atravesaba fuertes problemas económicos-, esta adaptación al cine del exitoso musical de Broadway original de Samson Raphaelson se logró al alternar secuencias con escenas con voz y música sincronizada con las interpretaciones de Al Jolson y con los subtítulos clásicos del cine silente. "The Jazz Singer" se convirtió en un ��xito de taquilla, y es que más allá de la anécdota que supone su lugar en la historia del séptimo arte -y pese a quienes señalan que posee una trama elemental o acusan que hace "trampa" al montar las grabaciones de las voces y las canciones con la imagen-, se trata de un filme con una calidad artística propia y cualidades narrativas e interpretativas de primer nivel que la colocan como una sobresaliente producción del cine clásico.

#7 GUY AND MADELINE ON A PARK BENCH 2009 | Dir. Damien Chazelle Escrita, fotografiada y dirigida por Chazelle, esta ópera prima de espíritu artesanal, es un musical monocromático que presenta el encuentro fortuito y el enamoramiento instantáneo que surge entre Guy y Madeline, en gran parte por el amor a la música que ambos profesan (particularmente al jazz). Sin embargo, la separación se presenta muy pronto y la película se enfoca en la manera en la que ambos intentan superar el fin de la relación y continuar con sus vidas por separado, aunque el destino tenga otros planes.

*** Encuentra muchos más títulos de "Cine Musical" en nuestro especial dedicado a este fantástico género ► http://bit.ly/2jpJHyJ ***

#La la land#an american in paris#guy and madeline on a park bench#the jazz singer#everyone says i love you#top hat#singing in the rain#les parapluies de cherbourg#cine musical#recomendaciones

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Helen Broderick and Edward Everett Horton as Madge and Horace Hardwicke in a publicity still for Top Hat (1935). Helen was born in Philadelphia and had 37 acting credits from 1924 to 1946. This is her only film among the best 1,001.

Edward's other film ranked 134-200 is Lost Horizon.

0 notes

Text

Bess of Hardwick: Four Times a Lady

Horace Warpole

Four times the nuptial bed she warm’d, And every time so well perform’d, That when death spoil’d each husband’s billing, He left the widow every shilling. Fond was the dame, but not dejected; Five stately mansions she erected With more than royal pomp, to vary The prison of her captive When Hardwicke’s towers shall bow their head, Nor mass be more in Worksop said; When Bolsover’s fair fame shall tend, Like Olcotes, to its mouldering end; When Chatsworth tastes no Can’dish bounties, Let fame forget this costly countess.

From The Letters of Horace Warpole:

On Bess of Hardwick: She was daughter of John Hardwicke, of Hardwick in Derbyshire. Her first husband was Robert Barley, Esq. who settled his large estate on her and her heirs. She married, secondly, Sir William Cavendish; her third husband was Sir William St. Lo; and her fourth was George Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, whose daughter, Lady Gracek married her son Sir William Cavendish.

0 notes

Photo

TOP HAT Upstairs at the Gatehouse, Highgate, until 28 January 2018 ‘… rich with romance, dazzle and wit’ ★★★★★ Irving Berlin’s musical is brought to us through the lens of RKO’s motion picture starring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. Based on this film and its book by Matthew White & Howard Jacques, it has lost none of its dazzle and wit. For those of us who find it hard to relate to monochrome and the film’s constant stream of gags, this live theatre version comes off better. It tells the story of a Broadway sensation, Jerry Travers who falls for society girl Dale Tremont. As he pursues her across Europe to London, he become the victim of mistaken identity. It is a show rich in romance and full of hilarious characters. Whilst Astaire and Rogers can never be surpassed for style and quality, they are surely matched by Joshua Lay and Joanne Clifton in the roles of Jerry Travers and Dale Tremont. Right from the opening number when Lay faultlessly catches his cane in mid-air, the choreography (by Chris Whittaker) is going to be something special. Together and with the ensemble they regularly bring the house down, especially in the number ‘Top Hat, White Tie and Tails’. Beautiful sound, exceptional choreography and wonderful dance skills from all. Added to this Joanne Clifton has star quality. She’s a fine actress with an extremely expressive face, has a good quality voice and of course, she can dance. Whilst her Strictly fame does not do her talent full justice, it is wonderful to see her live. The curve of her back, the light quality to her movements and her luminous smile all add up to a fairy-tale loveliness, no doubt aided by costume and hair dressing. The design for this show is exceptional, particularly Clifton’s white dress, with feather boa, which floats with wispy airiness, complimented with an elaborate hairstyle probably a wig or hair piece (designed by Jessica Plews). The raft of characters in the show adds interest and much humour. Perhaps one or two of the ‘gags’ fall flat but overall they are brought to life and hit their mark over and over again. The hilarity factor rises to heights way beyond five stars, when Matthew James Willis as Alberto Beddini gives his rendition of ‘Latins Know How’. Rather less over the top, Darren Benedict as Horace Hardwick, is wonderful to watch in his role as Jerry Travers’ concerned producer and fall guy to his wife. Madge Hardwick is finely played with both frostiness and warmth by Ellen Verenieks. Overall, huge congratulations to director John Plews, whose long career in theatre (much of it on cruise lines Princess, Cunard and P&O) has fully paid off in this production. His experience really shows. Finally, a word about the band led by musical director Charlie Ingles with orchestrations and arrangements by Dan Glover. What a wonderful sound they make, complementing the many outstanding numbers in the show. Get a ticket if you can, it’s deservedly selling very well! Photography: Darren Bell Box Office: http://www.upstairsatthegatehouse.com/top-hat TOP HAT 13 December 2017 – 28 January 2018 Presented by Ovation Upstairs at the Gatehouse, Highgate, Music & Lyrics by Irving Berlin Based on RKO’s Motion Picture Book by Matthew White & Howard Jacques Presented by arrangement with R&H Theatricals Europe Reviewer Heather Jeffery is founder and editor of London Pub Theatres magazine www.londonpubtheatre.com (email for press releases: [email protected]) Formerly playwright and Artistic Director of Changing Spaces Theatre. Her credits include productions at Drayton Arms Theatre (Kensington), Old Red Lion Theatre (Islington), VAULT festival (Waterloo), St Paul’s Church (Covent Garden), Cockpit Theatre (Marylebone) and Midlands Arts Centre (Birmingham)

0 notes

Text

Top Hat: Astaire and Rogers have dancing down pat

youtube

Top Hat was released in 1935. The film was directed by Mark Sandrich, with songs written by Irving Berlin. This is the fourth and most well-known movie where Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire star together.

Fred Astaire’s movies differed from Busby Berkeley’s. Rather than having constantly changing camera shots, Astaire preferred to keep the camera steady in order to showcase the choreography. Also, rather than Berkeley’s dance numbers which had nothing to do with the plot of the film, Astaire’s numbers were always there to move the plot forward.

In Top Hat, Fred Astaire plays Jerry Travers, an American Broadway star who debuts his show in London, and Ginger Rogers plays Dale Tremont, an American model who wears the designer clothing of Alberto Beddini (Erik Rhodes). They meet in a London hotel after Jerry tapdances on the floor directly above her room while she is trying to sleep. Jerry falls in love with her instantly, follows her to the park, and follows her to Italy after his show. There’s just one problem- Dale thinks that he is Horace Hardwick (Edward Everett Horton), who is married to her best friend Madge (Helen Broderick).

The score was written by Irving Berlin, a famous songwriter behind many standards, including the song “God Bless America.” The success of the film led him to write the score for five more Astaire films.

The typical Fred Astaire film included three numbers: the solo dance, the comedic partnered dance, and the romantic partnered dance. In this particular film, the corresponding numbers were “No Strings (I’m Fancy Free),” “Isn’t This a Lovely Day (To Be Caught in the Rain),” and “Cheek to Cheek.”

youtube

youtube

youtube

The most popular number from the film (and arguably the most popular number ever done by Astaire and Rogers) is “Cheek to Cheek,” where the two dance on a crowded dance floor and eventually venture off alone, effortlessly dancing and showcasing the beautiful Venice hotel (the set was so big that it took up two sound stages and was roughly the size of Grand Central Station).

The ostrich feather dress that Rogers wore in the film was actually designed by Rogers herself. She insisted on wearing it, despite the production team hating it, and Astaire ended up hating it as well, since the feathers flew straight into his face. Eventually, the producers let her wear the dress for the film, but had the costume designer sew the feathers on more tightly (if you look closely, you can see feathers on the dance floor).

Astaire and Rogers continued to make five more films together as a professional duo, until they decided to move on with their solo careers at the end of the 1930s. Top Hat showcases Astaire and Rogers at their best; their chemistry and technical dancing skills continue to be admired by audiences today.

-

Sources:

http://www.filmsite.org/toph.html

http://www.reelclassics.com/Teams/Fred&Ginger/fred&ginger4.htm

http://clothesonfilm.com/ginger-rogers-ostrich-feather-dress-in-top-hat/14378/

http://thefilmspectrum.com/?p=18557

http://brightlightsfilm.com/fred-ginger-hit-highest-peak-top-hat/#

http://themovieprojector.blogspot.com/2011/10/top-hat-1935.html

http://www.tcm.com/this-month/article/133542%7C0/Behind-the-Camera.html

0 notes

Photo

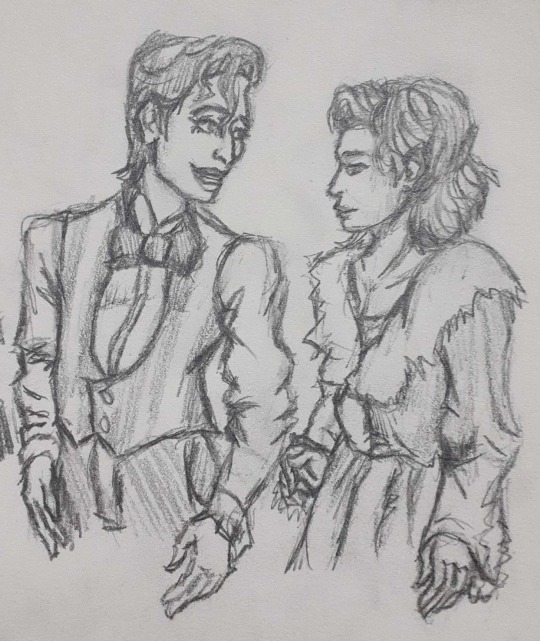

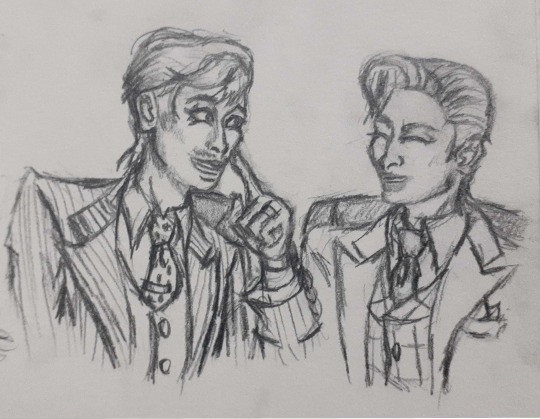

Did Some Top Hat Sketches! Tho it was more Horace x Madge tbh (Oto K TT^TT) Idk why but Maiti and Oto K made their relationship a lot cuter than the 2015 version. Also, Beddini ❤️

#takarazuka revue#takarazuka#top hat#tophat#minami maito#oto kurisu#yuzuka rei#hoshikaze madoka#hozumi mahiro#hanagumi#sketch#horace hardwick#madge hardwick#Alberto Beddini#jerry travers#dale tremont#Horace and Madge just kissing each others cheeks through out the show counter when#Jerry & Dale just got engaged and the it's two anniversary#They ended up sharing rooms and stuff happens so...lets keep it PG#Seeing Horace freak out with Jerry in a Plane made me wonder what if its Madge#Could be the reason these two don't fly together now that i think about it HAHAHA#I squeezed ReiMado somewhere there#Alberto in this play is for some reason is almost my..ideal man...i mean i like how he dresses and is a designer...soooo#Proceeds to dump in tumblr ikr#wait up im doing horace in a showercap art

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roy Eldridge