#hokum! productions

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Rain World Flat Earth Theory. I'm serious

Moon does not believe that the spritual elements of the setting are real or legitimate, but we, the slugcat, know that they absolutely are. We interact with echos, we interact with void worms. We clearly and obviously experience a spiritual journey throughout the game.

Moon describes echoes as "horror stories" which would "grandiosely haunt the premises forever" [LF Red pearl], and dismisses spiritual practice as "an instruction on how to starve yourself on herbal tea and gravel, but disguised as a poem" [LF Red pearl]. She completely doesn't understand why the Benefactors would care about keeping automated holy object production on the same grounds as the temple [HI blue pearl]. She famously dislikes having citizens in the UW Green pearl. Her disdain for their beliefs and culture is made clear through her dialogue.

When she speaks of the scientific, however, there is no trace of that implied doubt. She speaks in a factual, matter-of-fact tone when discussing the cyclical nature of life and death [SU Blue pearl] and how circumventing the self-destruction taboo works [CC Gold pearl].

I make the case that, despite being an inherently unreliable narrator due to her expressing a personal perspective to the slugcat, when it comes to matters of science, she can be taken at her word.

"If you leave a stone on the ground and come back some time later, it's covered in dust. This happens everywhere, and over several lifetimes of creatures such as you, the ground slowly builds upwards. So why doesn't the ground collide with the sky? Because far down, under the very, very old layers of the earth, the rock is being dissolved or removed. The entity which does this is known as the Void Sea." [SB Teal pearl]

If the world of Rain World were a globe, this would necessitate that the globe is ever-expanding as the globe is hollowed out from the inside. Moon specifically says "collide with the sky" as if it were a ceiling. An ever-expanding globe would have to reach that ceiling eventually as it grows, but that doesn't appear to be happening. This only makes sense if the world is flat.

So where's the end of the world? I don't know. Maybe it's like the Pirates of the Caribbean where you have to be enlightened enough and already know where it is in order to find it.

Or maybe this is complete hokum and she only sounds authoritative on the subject because she thinks she knows the scientific truth but it's really just hard-programmed knowledge, courtesy of the Benefactors, who were totally wrong. That seems like a break in character for her though, since, if they did that, why not hard-program affection for them too?

Maybe the Watcher dlc will provide more information on the subject. That's why I wanted to get this post out there before then. A game like Rain World implying that the truth is somewhere between the scientific and spiritual makes sense, considering how the game really likes blurring the lines already. Further iteration upon a theme.

#rain world#rain world lore#do i believe the devs intended to imply that the world might be flat? at this point no. that's not stopping me though

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

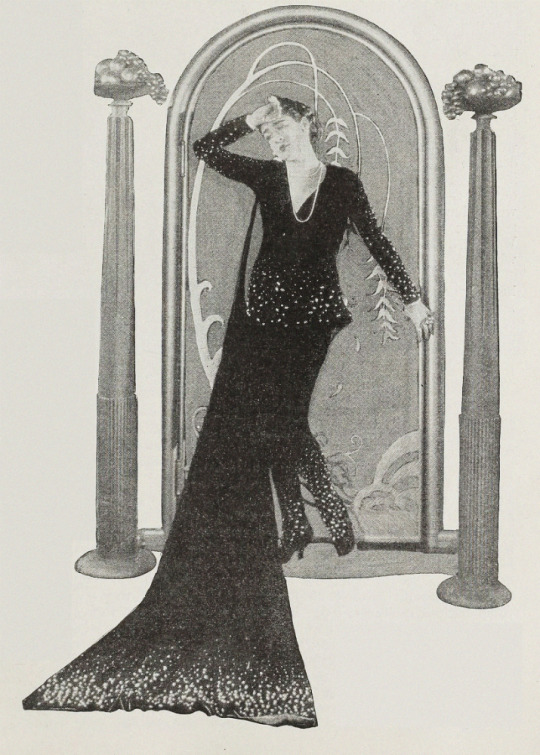

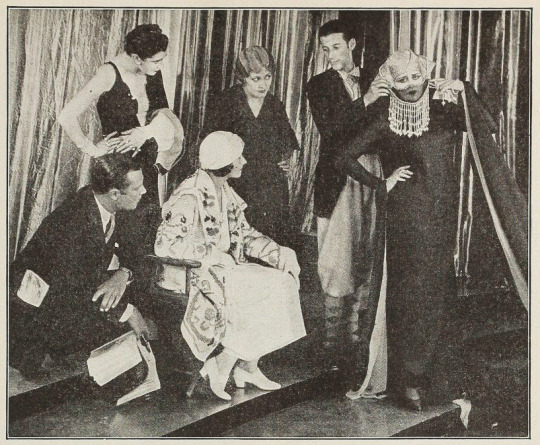

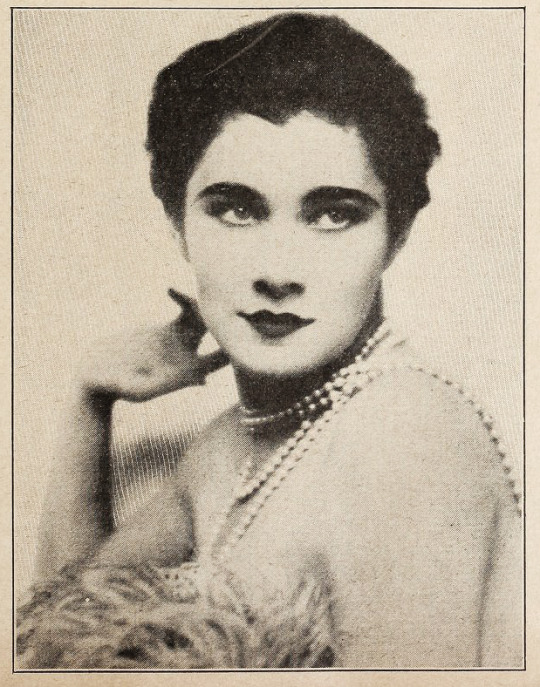

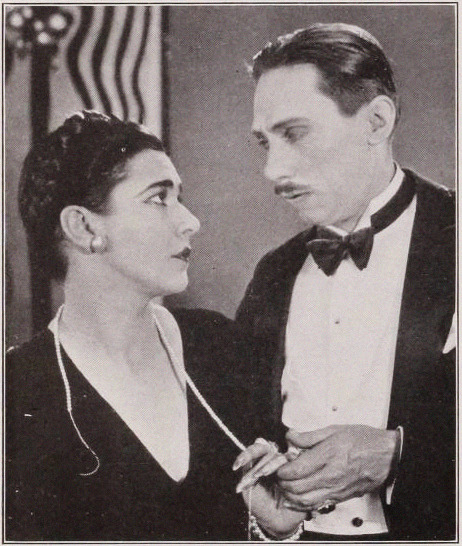

Lost, but Not Forgotten: What Price Beauty? (1925)

Direction: Thomas Buckingham

Scenario & Story: Natacha Rambova

Titles: Malcolm Stuart Boylan

Production Manager: S. George Ullman

Camera: J. D. Jennings

Art Direction: Natacha Rambova

Production Design: William Cameron Menzies

Costume Design: Adrian

Studio: Circle Films (Production) & Pathé Exchange (Distribution)

Performers: Nita Naldi, Pierre Gendron, Virginia Pearson, Dolores Johnson, Myrna Loy, Sally Winters, La Supervia, Marilyn Newkirk, Victor Potel, Spike Rankin, Rosalind Byrne, Templar Saxe, Leo White Maybe: John Steppling, Paulette Duval, Dorothy Dwan, and Sally Long

Premiere: None, general release: January 22, 1928

Status: Presumed entirely lost.

Length: Variously reported as 5000 and 4000 feet (more commonly listed as 4000) or 5 reels

Synopsis (synthesized from magazine summaries of the plot):

Mary, a.k.a. “Miss Simplicity” (Dolores Johnson) is a starry-eyed, country-to-city transplant. She works at a beauty shop operated by a glamorous matron (Virginia Pearson) and owned by the young and handsome Clay (Pierre Gendron).

Mary is in love with Clay, but doesn’t have the nerve or feminine wiles to woo him. The uber-sophisticated Rita (Nita Naldi), however, is chock full of nerves and wile. Rita’s fancy clothes and perfumes and advanced flirting skills leave Mary feeling destined to fail at winning Clay’s amorous attention.

These feelings sublimate into an expressionistic dream for Mary, where she finds herself transformed into a sophisticate like Rita. Her boss is seen as a magnificent wizard, converting her clients into archetypes of glamour: exotic types, flappers, and sirens. Her competition, Rita, is seen as a bewitching spider.

In the end, surprising Mary, it turns out that her fresh-faced, unassuming charm is more appealing to Clay than Rita’s more practiced charm.

Additional sequence(s) featured in the film (but I’m not sure where they fit in the continuity):

Scene of the trials and tribulations of a fat woman trying to “reduce”

Points of Interest:

Only one quarter of Nita Naldi’s Hollywood films have survived (7 extant titles/21 lost or mostly lost titles).

——— ——— ———

What Price Beauty? was the first and only film produced under Natacha Rambova’s own company. Coordinating production for the film was the business manager for Rambova and her husband Rudolph Valentino, S. George Ullman. The couple met Ullman when he was working for Mineralava beauty products, the sponsor of their 1922-3 dancing tour.

When Rudolph Valentino entered into a contract with United Artists, said contract reportedly stipulated that Valentino-Rambova were not a package deal. Therefore, Rambova could not collaborate with Valentino on his productions for United. Possibly as consolation, Ullman funded a production for Rambova while Valentino worked on The Eagle (1925, extant).

For Rambova, What Price Beauty? was meant to be a proving ground for her idea that an artistic film could be made on a modest budget. She also wished to remind people that she was a skilled artist in her own right.

In an interview in Picture Play Magazine from August 1925, Rambova asserts:

“…I do not want the production in any sense to be referred to as high-brow or ‘arty’. My reputation for being ‘arty’ is one of the things that I have to live down, and I hope by this picture, which is a comedy—even to the extent of gags and hokum—to overcome that idea. “A woman who marries a celebrity is bound to find herself in a more or less equivocal position, it seems, and her difficulties are only increased when she happens to have had some artistic ambitions of her own before her marriage. I am afraid that those who have accused me of meddling in my husband’s affairs forget that I enjoyed a certain reputation and a very good remuneration for my work as well before I became Mrs. Valentino.”

“What I desire personally is simply to be known for the work which I have always done, and that has brought me a reputation entirely independent of my marriage.”

There isn’t a vast amount of information on what exactly prevented WPB from gaining release in a timely fashion. If the film was truly nothing more than a ploy to separate Rambova from Valentino, that would be an absurd waste of time, money (~$80,000 in 1925 USD), and talent—Rambova employed soon-to-be famous designer Adrian for costumes and William Cameron Menzies for set decoration. Not to mention that, in front of the camera, Nita Naldi was still a popular star and the Rambova discovery, Myrna Loy, made her quickly hyped debut.

When Pathé finally purchased WPB for distribution in 1928, they did very little to promote the film. Naldi had moved on from the film industry—as had Rambova. And, while Loy hadn’t become the huge star we know today by January of 1928, Warner Brothers had already given her top billing in a number of films. Pathé barely mentions Loy’s role in the little promotion they did do.

To put WPB’s release in the context of Rambova’s personal/professional biography (which you can read more about here):

June/July 1925 – WPB is completed, Rambova and Valentino separate (in July according to Rambova’s mother as quoted in Rambova’s book Rudy)

August 1925 – Rambova leaves Hollywood for New York City, reportedly to negotiate distribution for WPB. She and Valentino would see each other in person for the last time. Rambova leaves NYC for Europe.

September 1925 – Valentino draws up a new will disinheriting Rambova

November 1925 – Rambova returns to the US to act in a film, When Love Grows Cold (1926, presumed lost), a title which Rambova objected to

December 1925 – Rambova files for divorce

August 1926 – Valentino dies

January 1928 – WPB is finally released with no fanfare by Pathé

In my research for my Rambova cosplay, the suspicious production/release history for this film stood out to me. I hoped that I might find some reliable evidence of whether WPB was a consolation prize and/or a scheme to keep Rambova and Valentino apart. Honestly and unfortunately, circumstantial evidence does support it!

After poring over what few contemporary sources cover WPB, there seemed to be no plan in place for distribution as the film was in production. United Artists, at whose lot the film was shot, claimed to have nothing to do with its release. Ullman had a news item placed about negotiating the distribution rights in the East. However, in Ullman’s own memoir, he admits that when he travelled to New York with Rambova, it was in a personal, not professional capacity—navigating the couple’s separation. (Ullman’s book contains many disprovable claims and misrepresentations, so anything cited from it should be taken with a grain of salt.) That said, Ullman’s failure to secure even a modest distribution deal for WPB in a reasonable timeframe speaks to how ill-founded Valentino’s and Rambova’s trust in his business acumen was.

WPB cost $80,000 to produce, which converts to $1.4 million in 2023 USD. While that wasn’t an outrageous budget for a Hollywood feature film at the time, especially one with such advanced production value, it’s certainly an absurd cost if the goal was only to separate a bankable star from his wife and collaborator.

A close friend and employee of Valentino and Rambova, Lou Mahoney, recalled in Michael Morris’ Madam Valentino:

“The picture was previewed at a theater on the east side of Pasadena, and Mahoney remembered the audience reaction as positive, but, thereafter, What Price Beauty? was consigned to oblivion. Mahoney knew why: ‘No help came from anyone, no thoughts of trying to get this picture properly released. No help came from Ullman, Schenck, or anybody else. Their whole thought was that if the picture were a success, Mrs. Valentino would be a success. She would then start producing under the Rudolph Valentino Production Company. But this nobody wanted—except herself, and Mr. Valentino.’”

——— ——— ———

The few reviews from 1928 that I was able to find are not very complimentary of WPB. The critics seem thrown by the film’s tone or genre—reading it as a drama. (Part of that is Pathé’s fault as they listed it as one.) But, according to sources contemporary to WPB’s production, it was intended to be a farcical satire of the beauty industry and social expectations of feminine beauty. Given the simple story, the intentional typage of characters (“The Sport,” “The Sissy,” and “Miss Simplicity”), and the over-the-top-but-on-a-budget art design of WPB, all signs point to high camp. In 1925 as well as 1928, the stodgier side of the critical spectrum would likely fail to see its appeal.

It’s a true shame we can’t find out for ourselves how good, bad, or campy WPB was as of yet, but here’s hoping the film resurfaces!

More about Rambova

GIFs of some of her design work on film

☕Appreciate my work? Buy me a coffee! ☕

Transcribed Sources & Annotations over on the WMM Blog!

#1920s#1925#1928#natacha rambova#nita naldi#cinema#silent cinema#american film#independent film#classic film#classic movies#film#silent film#silent movies#silent era#classic cinema#silent comedy#lost film#film history#history

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Red XIII and Sage Fire in Final Fantasy VII (1997), Remake (2020), and Rebirth (2024).

Heya, folks. I'm back after a long break for the holidays. SPOILERS for anything generally related to Red XIII and Cosmo Canyon in the 1997 or Remake releases.

As always, If you think even rudimentary literary analysis is academic hokum reading too far into things, this post is, as kindly as I can say, not meant for you. To the people who enjoy reading and leave kind words even on the posts I've deleted, thank you kindly again.

I'm covering two pieces of the game I adore at once, Red XIII and Cosmo Canyon, so this will be a longer post. To start with, though, I'm going to highlight a piece of media which was highly influential on modern anime and one of its most famous names, Osamu Tezuka.

Princess Iron Fan and Manga Into Anime

One of the underrepresented stories of East Asian media in English is the story of the Wan brothers' 1941 film, Princess Iron Fan. The film loosely adapts the portion of Xiyouji in which the pilgrims need to obtain a legendary fan from the eponymous Princess Iron Fan in order to pass Flaming Mountain. Much of the film depicts heroic duels between Monkey and Princess Iron Fan or Bull Demon King, with Monkey receiving aid from others along the way.

As Hongmei Sun points out in Transforming Monkey: Adaptation and Representation of a Chinese Classic, this film comes at the end of the Republican era of Xiyouji adaptation, so it also exists within the context of the Japanese occupation of much of China. While much of the film is intended as anti-imperialist allegory, Sun points out that the occupation of Shanghai caused text which she gives in English as, "all Chinese people must unite for victory against the Japanese invasion," to be censored from the film's release (61).

This might seem like an odd film to have influenced such a major individual in Japanese cultural exports, but the absence of this message meant that the film's introduction could be used to read the film as a story of people coming together, believing in one another, and overcoming individually insurmountable difficulties and foes outside of the Chinese cultural context at release. As it were, this film and the spirit that can be read from it inspired Osamu Tezuka, along with a picture-book copy of Journey to the West, in his creation of My Son Goku (1952).

This manga was serialized for much of the same time as his Astro Boy (1952) but received an animated film adaptation first as Saiyuki under the English name Alakazam the Great (1960). It was this 1960 adaptation that inspired Osamu Tezuka to move from the world of manga to the world of anime, and it's influence outside of him can be seen to this day. Many anime bear the production features employed on this film, and it's cultural impact extends from inspiration for single characters like Mario's Bowser to being one of the foundational pieces contributing to the work of super deformed media and nekketsu.

While nekketsu isn't a term often used in English, Astro Boy and My Son Goku are examples of foundational nekketsu shonen. If you've ever tried to describe the manga, anime, and RPGs with a spiky-haired, often blonde, naive protagonist who dreams of big things as a child, loses or lacks one or both parents early in the story (especially lacking a father and often around an event that marks a "time skip" in reader and/or character perception of the narrative), has abilities beyond any normal person that might mark them as not wholy or more than human, and seems to only get stronger and more determined or angry when anybody else would die, the word is probably nekketsu, "hot-blood."

If you are aware of Xiyouji, many of these features might seem familiar, and it is because many of the features of nekketsu are simply the influence of Xiyouji and Princess Iron Fan on people like Osamu Tezuka while creating two of his most influential manga among many during the post-war. If there is nothing else, and there certainly is much else, to be found in Hongmei Sun's Transforming Monkey, it is that Monkey is a multivalent character that excels in transforming in exactly this way as well as any other. In a postwar Japan, it only makes sense that the Monkey would adapt to consider questions of belonging, family, goodness, the environment, and humanity when those things had been challenged so thoroughly and intimately by the preceeding decades for people like Osamu Tezuka.

Tezuka's Goku emerging from his rock, the Calamity from the Skies setting up the rise of Final Fantasy VII's protagonist, and a spacepod depositing Toriyama's Goku once Goku had been revealed to be an alien. The sci-fi and environmentalism is Tezuka, but heavenly rocks and metal birthing the protagonist are all Xiyouji

I am going on at length about Tezuka after bringing up this film, but it is important to not understate how influential it and Xiyouji are for nekketsu manga, shonen, and RPGs through the influence of Osamu Tezuka. They are so important for Tezuka and those that worked with him, at least, that one of his final works was a postumously-completed and released animated film entitled I Am Son Goku: The Osamu Tezuka Story (1989). The film was split between a biography of him centered on the Monkey's influence on him and a sci-fi adaptation of his original My Son Goku. Some later releases of My Son Goku even included Tezuka noting how influential the specific gags of My Son Goku had become on other mangaka creating similar nekketsu.

As a cute note before I finally dive into the film for more specific discussion, I Am Son Goku ends with Goku reassuring Tezuka that his works will continue to spread the message of ending war and protecting the environment well after his death, which is another feature nekketsu shonen, manga, and RPGs often share, whether or not they fall closer to sports media or Xiyouji media.

Buddhism and the Journey

As Princess Iron Fan was released into the wartime, Republican environment, the Wan brothers had an interest in downplaying the fantastical and spiritual of the story in favor of the relevant and materially allegorical. Because of this, key moments around these chapters, such as the conflict between Monkey and the Sixth-eared Macaque over the Journey before this section of the story, Red Boy's conversion to the Buddhist cause and away from his parents' past around ten chapters beforehand, the nearby kingdom in which the bald are killed, or any of the main pilgrims having to face their pasts, are left out, ignored, or sidestepped in favor of key narrative points around Flaming Mountain. Other elements, such as a battle with what one might call a masked demon and two fire spirits, an impassioned speech convincing the people nearby that the pilgrims' cause might be right to fight for together, and Bull Demon King crying for his wife and son are added or manipulated.

While not an unheard-of set of opponents to Monkey, the fire spirits and demon mask of Princess Iron Fan (1941) might be more familiar to players of the 1997 release, especially as the mask is used to deliver the first scare of Chinese feature film.

Avoiding the overtly Buddhist is common for modern uses of Xiyouji, with much advertising and Western use largely simplifying the Monkey down to a kind-hearted, rogueish hero. Along with much of the world in the '70s to the '90s, however, these uses in Japan saw a turn back towards the spiritual while maintaining much of the heroicism and secular collectivism found in Princess Iron Fan and Havoc in Heaven (1961).

Highlights of this among these are NTV's Monkey (1978) and both Akira Toriyama's early Dragon Ball as manga (1984) and anime (1986), which used explicitly Buddhist, Taoist, Confucian, and Shinto language and ideas to communicate both spiritual and material ideals. Early Dragon Ball, especially, serves as a blend between the Xiyouji that can be read most easily through 20th century Chinese film export interpreted in Japan, with heroes and the people combating corrupt gods and demons, and as 19th century Chinese textual export interpreted in Japan, with spiritual allegory that extends from our place in communities to our place in the universe as a whole over questions of selfhood and belonging.

With this context and the lens of reading Final Fantasy VII Remake and Rebirth through the lens of Xiyouji as precursor text, we can turn towards the place itself.

Cosmo Canyon and Flaming Mountain

Silk Road Travel advertises with this photo of Monkey on his cloud somersault atop a sign that reads "Flaming Mountain." Not pictured are novelty thermometers, swarms of tourists trying to recreate Xuanzang's journey, or promises of feeling the heat of True Samadhi Fire.

The Flaming Mountains are a real place in China as part of the Tian Mountain range in the Taklamakan Desert. Within Wu Cheng’en's 1592 text, the Flaming Mountain is a result of Monkey's actions in Laozi's heaven, and the nearby community lives in entirely red buildings. Within Princess Iron Fan, Flaming Mountain is much the same, but the nearby community exists capping the peak of a rocky spire. In our world, The Flaming Mountain exists as a folk-history and folk-spirituality tourist destination of sandstone hills situated near the Lianmuqin and Subashi Formations, paleontological sites. Ruins of Buddhist temples dot the sides and caves of the mountains on the Silk Road towards the Flaming Mountains.

While Cosmo Canyon doesn't block the path of the party to a kingdom where those shaved bald are killed, instead sitting on a separate continent from a bar where only the bald are allowed, it does bear the image of many takes on Flaming Mountain. Tifa, for example, takes Cloud back into the unknown journey just before they reach Cosmo Canyon as Tripitika does Monkey into the Journey after the Sixth-eared Macaque fooled him, but the people of Cosmo Canyon live on the sides of a rocky spire and not simply by the road as in the novel.

While both communities help and need the help of those on the journey, the residents of the spire in Final Fantasy VII have always been less-than-interested in conflict.

Cosmo Canyon even bears the image of the real Flaming Mountain, a tourist destination atop a desert site of cultural importance existing within a world rapidly distancing itself from the metaphysics and spirituality of many stories of the past.

Square, however, obviously means to explore this connection to the past. If you are familiar with nekketsu, this and the fact that Jungian collective unconscious and Yogachara Buddhism are involved in creating the third part of the Remake series should be unsurprising - the influence of Xiyouji on nekketsu means that its characters are often embodiments of the Mahayahana Buddhist thought that inspired Jungian theory and, in turn, much of early Western literary theory.

For example, the protagonist of many nekketsu which bear the influence of Xiyouji through Tezuka will have an "evil" double born from a traumatic point in their life which they must defeat and reintegrate in some way to reach an apotheosis in a mirroring of Monkey's allegorical taming of the heart-mind monkey. In a text which takes an explicitly Jungian lens, that might be framed as individuation beginning with a trauma that causes the ego to undergo conflict and, ultimately, integration with the shadow as a part of the path towards realization of the Self.

This should sound similar to a number of Square titles, as they regularly use these two inventories, the psychoanalytic of Jung and Freud and the literary and spiritual of China. A character born of a heavenly rock who must go on a journey and integrate unwanted parts of the psyche alongside an equally allegorical cast was the name of the game for several Square titles from 1997 to 1999 with Cloud, young Cloud, and Sephiroth in Final Fantasy VII, Fei Wong, young Fei Wong, and Id in Xenogears (1998), and Zidane, young(er) Zidane, and Kuja in Final Fantasy IX (1999). This should be as familiar as the formats offered up by any of the other influential works of Chinese literature, like Water Margin (Suikoden in Japanese and transliterated back) and Romance of the Three Kingdoms with their political intrigue and drama.

Few nekketsu, however, more deeply and regularly explore characters involved in these dynamics outside of the main archetypes that can be found in the five pilgrims of the 1592 text. For many nekketsu, the focus can even laser itself onto the primary protagonist as the Self or untamed heart-mind before jumping to characters born of other precursors, such as is the case with Naruto (1999).

Final Fantasy VII, however, tends towards sympathy and mercy towards many of the villainous archetypes born of Chinese literature and popularized through Xiyouji while continuing to give them focus. Of those, my favorite is Red XIII.

Red XIII, Red Boy, and Rebirth

Within the 1592 text, Red Boy's involvement is mostly in Chapters 41-42 of the hundred chapter versions where he deceives the pilgrims about his age, makes attempts to eat the flesh of the Tang Monk to gain immortality, and is finally limited with gold bands on his wrists, ankles, and head by Guanyin to bind him to Buddhist practice. During the events adapted by Princess Iron Fan from Chapters 59-61, Red Boy is largely present only in reference to earlier events.

While there are myriad readings of Red Boy's involvement in Xiyouji, one of the most obviously popular interpretations in Japanese Xiyouji media in the '70s-'90s is that of youthful folly. Red Boy, the young child of Bull Demon King and a powerful demon princess, Princess Iron Fan, is quite often presented as he is in NTV's Monkey (1978) - a youth eager to match the deeds of his parents. Monkey itself goes so far as to remove Red Boy's deception of the pilgrims as an elderly man entirely, replacing it with an outspoken desire to emulate and usurp his elders.

This isn't to say, however, that Red Boy is a character consistently brought into adaptations of Xiyouji in Japan or elsewhere. Red Boy, while a popular character from the 1592 text, is not present in many of the most oft-adapted portions of the text, rendering him a character without much to do or be if he is included at all. As a villain outshone in popularity by his parents, Red Boy often becomes other characters entirely in places he was not before.

While Square and Enix had not yet merged in 1997, their red children of trapped fathers with complicated relationships in Final Fantasy VII's Red XIII and Saiyuki's Kougaiji (Red Boy) are strikingly similar. Few Red Boys have such design similarity.

As a highlight to this point, it is difficult to find an explicit manga, anime, or video game adaptation of Xiyouji from Japan that both contains Red Boy and maintains any symbolism, structure, or allegory from his original appearance. Chi Chi of Dragon Ball (1984) shares some elements with Red Boy during the early parts of Dragon Ball acting as adaptation, like being the child of a "demon" king. She does not, however, share many. Red Boy of the Koei-published tactical RPG Saiyuki: Journey West (1999) is an explicit adaptation of the 1592 character, but his entire story has been transformed through the lens of youthful folly to allow for his parents to join the pilgrims on their journey. He does, however, retain at least a passing connection to Red Boy's sage history and fiery abilities.

Red XIII in Final Fantasy VII blends many of these lenses and modifications while still bending them towards their original form. His flesh-eating and violent origins in attempting to first eat the Monk before attacking Guanyin are restored, for example, in the brief moments before Aerith interacts with the gold-bound boy feigning ferocity and venerability and says, "This child's a friend." This is rather similar to his false-aggression towards Aerith in the 1997 release, but builds more directly towards the reveal that Aerith has deep connections to children and that Red XIII is being deceptive beyond his later attempts to hide his insatiable desire for meat. This allows Final Fantasy VII to retain the frameworks most Xiyouji-influenced stories from Japan direct towards the folly of youth while preserving two elements of Red Boy's taming for other points in the story: the True Samadhi Fire that Red Boy ought to wield and the waters Guanyin provided to defeat it.

True Samadhi Fire, Killing the Unkillable, and the Protector of the Vale

True Samadhi Fire is usually not an important element in adaptations of Xiyouji from Japan. In fact, many Japanese adaptations isolate discussion of it to episodes involving their own Red Boy, implement it as part of an escalating set of powers, make it a one-time threat to the world itself, or exclude it entirely. This is not entirely surprising, as traditional nekketsu media in manga and anime often relies commercially on increasingly powerful threats. Once a threat has been overcome, returning to ponder on the significance of that defeated threat for several releases can itself threaten sales. True Samadhi Fire is one of the only things shown to be an imediate threat that cannot be overcome by Monkey without the aid of Guanyin in the novel, and this as a cycle would be exceedingly boring. If Japaneae adaptations or nekketsu adapt the story of Red Boy being defeated, they often either quickly move on or elevate the stand-in for True Samadhi Fire to a global disaster. This isn't uncommon outside of Japan, either, as Japanese versions of, adaptations of, and works inspired by Xiyouji grow increasingly popular.

Boruto with its weakened True Samadhi Fire, and the descending celestial dumpling standing in for True Samadhi Fire in the Lego Group's Lego Monkie Kid. The small spire is the center of a massive Lego city that Guanyin's waters will be used to protect, and true True Samadhi Fire is discussed in other episodes.

True Samadhi Fire, however, is an exceedingly interesting feature of a demon-turned-devotee like Red Boy. While ignored by many adaptations, True Samadhi Fire is often read to represent a polar opposite of the errant and indecisive mind represented by the Monkey. The "Monkey archetype," unindividuated Self, or heart-mind monkey idea-will horse is impulsive, indecisive, and bound to the whims and energies of the world around it, but the wielder of True Samadhi Fire represents the mind capable of existing in samadhi, an undistracted almost-opposite to the chaos of the heart-mind monkey and idea-will horse.

These features create the opportunity for a character which goes through a journey of cultivation of the body, so to speak, when Monkey's or the central protagonist's is often excluded from works. The "time skip" in nekketsu often serves to occlude this period of the central protagonist's development from the reader. This is the case in Final Fantasy VII (1997) and both entries in the Final Fantasy VII Remake (2020) series, where the period between Cloud's childhood and the destruction of Mako Reactor 1 are obscured by a time skip substantial enough to be acknowledged regularly by the text itself.

As such, these precursor elements can be expanded to explore elements of the story more deeply. Unlike other characters born of the same precursors, Red XIII is able to explore the period of Taoist-influenced teaching under Sage masters that Monkey underwent before his rebellion and imprisonment. Bugenhagen, then, can act as a Sage directing Red XIII towards development of the body, so to speak, as a Patriarch Subodhi-like mentor that usually appears in characters like Dragon Ball's Master Roshi.

More importantly, however, distancing the work from three of the most popular villain "archetypes" in the medium allows Final Fantasy VII and the Remake trilogy to subvert expectations within the plot around them. There is no feeling of grand betrayal when Red XIII reveals his age, but laughing and joking between friends. The audience is even warned fairly early in Junon that Red XIII is both lying and that Aerith doesn't mind. There is no ultimate defeat of the traitorous and detested father of Red XIII, but a tearful reunion and redoubled commitment to the journey. While this mirrors the conversion of the Bull Demon King in many Flaming Mountain episodes, Seto did not need to convert. There was also nothing the party needed there to pass, as the terminal they needed was converted into a turbine. All of this and more allows Red XIII of Final Fantasy VII (1997) to be a character that exists in the niche of deceptive, fiery child-antagonists with powerful parents while expanding on that Red Boy niche in a meaningful way through the Watcher of the Vale title.

Bull Demon King of Princess Iron Fan (1941) and Seto trapped, crying for their red sons, and giving their support to the protagonist's journey.

What this culminates in is threefold: Meteor has become associated with Cosmo Canyon and symbolic of both clarity of mind and duty through it, Red XIII has become the explicit successor to Seto's promise to return Meteor to the Gi, and the Cosmo Canyon episode of Rebirth serves to refocus the journey on Cloud's mental journey by showing the "reader" a child stepping onto the same path. While this all amounts to the same narrative direction as the 1997 release, the short of it is that Red XIII's connection to the symbolic and literary history of True Samadhi Fire has extended from his tail to the symbol of the series itself: Meteor.

Brief Conclusion and Fun Fact

TL;DR: Red XIII fits the Red Boy "archetype" in a way I think is just as interesting as the way Cloud is used to explore the Jungian archetypes "born" of folk ideas from texts like Xiyouji and the folk-Mahayana thought behind and around them. I think this lens also serves as a way to synthesize all parts of Final Fantasy VII into a journey of Cloud's "selfhood" all the way up to "samadhi" and what he must do looming in the sky as Cloud tears himself apart.

As the fun fact for this one, Monkey goes to the edge of creation after his rebellion against Heaven, but he doesn't teleport around and fight his Sixth-eared Macaque like Cloud does his Sixth-shouldered Psychic Shadow.

Monkey of NTV's Monkey at the edge of creation, having flown there on his cloud somersault. Monkey-figures will often travel to the edge of creation, the afterlife, and return to a great city by the end of their journey.

Tezuka work images from Tezuka Osamu Official. Dragon Ball image from fan wikia. Saiyuki image from fan wikia. All used works are mentioned save Anthony C Yu's 2015 Revised Edition of his translation of Wu Cheng’en's Xiyouji, and I've tried to only mention chapter proximity to cut down on this being unreadable to people who don't like that from citations and footnotes. These are getting long enough that I'm just gonna find a way that makes bibliographies doable here.

Thank you for reading if ya did :D

#ffvii rebirth#ffvii remake#ff7#final fantasy 7#ffvii#final fantasy vii#red xiii#nanaki#osamu tezuka#tezuka osamu#wan brothers#wan laiming#xiyouji#saiyuki#cloud ff7#final fantasy VII meteor#samadhi#true samadhi fire#jungian analysis#cosmo canyon#flaming mountain#cloud strife#bull demon king

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Robert Morley and Norma Shearer in Marie Antoinette (W.S. Van Dyke, 1938)

Cast: Norma Shearer, Tyrone Power, John Barrymore, Robert Morley, Anita Louise, Joseph Schildkraut, Gladys George, Henry Stephenson. Screenplay: Claudine West, Donald Ogden Stewart, Ernest Vajda. Cinematography: William H. Daniels. Art direction: Cedric Gibbons, Henry Grace. Film editing: Robert Kern. Costume design: Adrian, Gile Steele. Music: Herbert Stothart.

Hollywood historical hokum, W.S. Van Dyke's Marie Antoinette was a vehicle for Norma Shearer that had been planned for her by her husband, Irving G. Thalberg, who died in 1936. MGM stuck with it because as Thalberg's heir, Shearer had control of a large chunk of stock. It also gave her a part that ran the gamut from the fresh and bubbly teenage Austrian archduchess thrilled at the arranged marriage to the future Louis XVI, to the drab, worn figure riding in a tumbril to the guillotine. Considering that it takes place in one of the most interesting periods in history, it could have been a true epic if screenwriters Claudine West, Donald Ogden Stewart, and Ernest Vajda (with uncredited help from several other hands, including F. Scott Fitzgerald) hadn't been pressured to turn it into a love story between Marie and the Swedish Count Axel Fersen. But the portrayal of their affair was stifled by the Production Code's squeamishness about sex, and the long period in which Marie and Louis fail to consummate their marriage lurks unexplained in the background. MGM threw lots of money at the film: Shearer sashays around in Adrian gowns with panniers out to here, with wigs up to there, and on sets designed and decorated by Cedric Gibbons and Henry Grace that make the real Versailles look puny. The problem is that nothing like a genuine human emotion appears on the screen, and the perceived necessity of glamorizing the aristocrats turns the French Revolution on its head. The cast of thousands includes John Barrymore as Louis XV, Gladys George as Madame du Barry, and Joseph Schildkraut (made up with what looks like Jean Harlow's eyebrows and Joan Crawford's lipstick) as the foppish Duke of Orléans. The best performance in the movie comes from Morley, who took the role after the first choice, Charles Laughton, proved unavailable; Morley earned a supporting actor Oscar nomination for his film debut. With the exception of The Women (George Cukor, 1939), in which she is upstaged by her old rival Joan Crawford, this is Shearer's last film of consequence. When she turned 40 in 1942, she retired from the movies and lived in increasing seclusion until her death, 41 years later. It says something about Shearer's status in Hollywood that Greta Garbo, who retired at about the same time, and who also sought to be left alone, was the more legendary figure and was more ardently pursued by gossips and paparazzi.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

One Piece May Be The Most Irritating Manga Comic Of All Time, But The TV Series Is Well Worth Your Time

You have to hand it to Netflix, they've done it again.

Whereas the original comic and animated TV series were definitely acquired tastes (or lack of it) with a protagonist with the most dubious set of teeth this side of Tony Blair, the live action series distills the essences of all the characters into a far more palatable form, and the world into a more palatable format.

Yes, a lot of it is cheesy, inbetween the moments which appear lifted straight from Terry Prachett's Discworld, but it holds up, not least of all because the cast play up their parts so well.

Iñaki Godoy is wonderfully silly as Monkey D. Luffy - whose rubber persona serves as a metaphor for his ability to constantly bounce back from every set back (and frequent severe beatings) that have his more rational reluctant crew begging to throw in the towel, not least of all stereotypical whirlwind swordsman Zoro (yes, really - played superbly by Mackenyu Maeda) and the calculating Nami (Emily Rudd finally getting a role in a major production) who act as effective counterfoils as they're sucked ever deeper into Luffy's madcap life - despite every brain cell they have telling them they ought to be getting a hundred miles away from this bumnugget's insistence he will find a fabled treasure and be crowned King of the Pirates.

By the end of the first series, Luffy's got an eyewatering price on his head, has pissed off just about every pirate hunter and every other pirate on the planet, has the entire Marine Corps after him - and yet hasn't done a single piece of actual pirating - let alone one piece ...

If you want to know how this Klutz Corsair managed that, you can bingewatch the entire eight episodes of the first series just now - much of it highly rewatchable.

If you fancy some low brow hokum with a not that low brow plot, you could do a lot worse that 'One Piece'.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Early-morning hater hours:

MARMALADE (2023): Fizzy Keir O'Donnell crime comedy-drama about a wide-eyed young hick (Joe Keery) telling his new jail cellmate (Aldis Hodge) about how his romance with a pink-haired wild child called Marmalade (Camila Morrone) became a crime spree. Familiar but very charming for its first 70 minutes, with a bright, poppy visual style and a vivid evocation of the feeling of falling for someone who pushes you out of your comfort zone in ways both good and bad, the film then loses the plot with a twist obviously inspired by the 1995 crime drama THE USUAL SUSPECTS, leading to a resolution that isn't nearly clever enough to make up for the loss of the story's original emotional core. A real disappointment after its enjoyable opening.

MONSIEUR SPADE (2024): Peculiar AMC/Canal+ co-production, set in 1963 and starring Clive Owen as Dashiell Hammett's Sam Spade, now a retired but still cagey man of leisure living on the country estate of his late French wife (Chiara Mastroianni) in the rural town of Bozouls and acting in loco parentis for Teresa, the now-teenage daughter of Brigid O'Shaughnessey (Cara Bossom). Spade is drawn into a complex web of murder and conspiracy involving a mysterious young Algerian boy many people will kill to find, and who is somehow tied up with Teresa's errant father, Philippe Saint-Andre (Jonathan Zaccaï). Elliptical and very French, the show's sun-dappled atmosphere is pleasant, but the oblique way the story takes shape demands closer attention than it ever rewards, and the actual plot is both convoluted and unconvincing; at one point Spade aptly calls it "hokum." Furthermore, while the show is most enjoyable where it focuses on the hard-boiled American detective's uneasy integration into drowsy French rural life, it ultimately struggles to justify placing Spade so far outside his original milieu. It seems like creators Scott Frank and Tom Fontana wanted to create something approximating the Conan Doyle stories of a retired Sherlock Holmes keeping bees on the Sussex Downs, but Spade is really too thinly drawn a character for that, although Owen is better than one might expect. I also don't buy that Spade's exploits (at least vis-à-vis THE MALTESE FALCON) would make him world-famous like Poirot or Holmes.

#movies#teevee#hateration holleration#marmalade#marmalade 2023#keir o'donnell#joe keery#aldis hodge#camilla morrone#monsieur spade#dashiell hammett#sam spade#clive owen#scott frank#tom fontana#chiara mastroianni#cara bossom#jonathan zaccai#marmalade ends up resorting to one of my most hated movie tropes#which i can't even complain about without spoiling the ending#also#some of you have the worst taste in men JFC

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

basically there's no way to engage with childcare in the united states and emerge normal. it's 100% a madness rune. like i'm not even talking about parenting writ large, but the institutions of education and care here are so fucked, and part of it is because education is both a vector of conspicuous consumption and because everyone wants social reproduction without paying for it. every type of daycare is insanely, outrageously evil in some capacity (literally all of them, yes including the one you send/sent your kid to/the one you went to). waldorf schools are literally white supremacist hokum, montessori schools are the Original 'daycare as class indicator,' reggio emilia is montessori II with extremely aggressive EU enforced branding (and no one i know who's worked one has recieved a living wage), and chain daycares are entirely oriented around the idea of 'kindergarten readiness' (which is to say, women making minimum wage attempting to drill sight words into three and four year olds in environments with live camera feeds and preparing lunches primarily comprised of canned products from sysco). if you are lucky, one of these will cost you around $10k for a year of care for one infant.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wendy’s Real-Life Krabby Patty Meal Healed My Millennial Malaise

It's dumb, but it's also delicious.

If you were born between the years 1981 to 1996, there’s a good chance you worshiped the ocean’s most beloved fry cook. To many, Spongebob Squarepants is what Jerry Lewis or Kurt Cobain was to older generations, and his show is one of the most iconic of the early ‘00s era.

Because of his omnipresence in the popular culture since his debut in 1999, fast-food giant Wendy’s conceived a meal honoring Squarepants’ 25th year on TV with the Krabby Patty Kollab Meal. But is this meal worth slogging through long drive-thru lines?

What Is the Wendy’s Spongebob Squarepants Krabby Patty Kollab Meal?

For the few of you out there who aren’t Sponge-pilled, Krabby Patties are dished out on the daily by Spongebob at the Krusty Krab, which is Bikini Bottom’s most popular burger joint. Wendy’s Krabby Patty Kollab isn’t just another cynical “celeb meal” that a couple of its rivals trotted out in recent years. They actually made a new product instead of repurposing stuff that was already on the menu. Here’s what comes in the Kollab Meal:

Krabby Patty Kollab Burger: A quarter pound burger topped with two slices of American cheese, lettuce, tomato, pickles, onions, and a “top-secret Krabby Kollab sauce,” all on a premium bun.

Pineapple Under the Sea Frosty: Wendy’s Vanilla Frosty swirled with a yellow mango and pineapple “flavored” swirl.

Fries: Wendy’s fries. Perfectly serviceable.

Is the Wendy’s Spongebob Squarepants Krabby Patty Kollab Meal Worth It?

Actually Securing the Meal

Here’s a tip. If you’re anything like me (stunted Millennial, sort ofashamed he’s excited about trying a meal from a cartoon he loves), youcan save yourself a little shame by ordering your meal through theWendy’s app. This saves you from having to utter the words “One Krabby Patty Meal, please” out loud to another adult.

Pineapple Under the Sea Frosty

It’s early Fall in Northern California, which means it’s 90 degrees outside. The Pineapple Under the Sea Frosty would not survive the 10 minute drive home. After snapping a quick photo I figured it would be prudent to have dessert first. The swirl wasn’t very pronounced here like in all the promo material. But the neon yellow pineapple/mango sludge mixed with Vanilla Frosty was nothing short of divine. Something like a tropical creamsicle. Much of it sunk to the bottom, which I carefully mixed back into the frozen dessert. I had planned to only eat half, and freeze the rest for later. But it didn’t survive the car ride.

Krabby Patty Kollab Burger

The burger—let’s not kid ourselves—is a basic Wendy’s burger with “special sauce.” One of my long-held fast-food conspiracy theories (aside from McDonald’s Sprite being complete hokum) is that every single orangey-pink burger sauce is the same. Sure, the ketchup, mayo, and chopped pickle quotient can deviate from chain to chain, but it all turns into Thousand Island in your mouth. Before unwrapping the burger, I did what my spouse and I always do at dinnertime: put on something to watch. We put on my favorite episode, Season three’s “Krusty Krab Training Video.”

The first bite made me laugh. A visceral reaction that I only do when I see something funny, am being yelled at, or am genuinely surprised. The Krabby Patty Kollab Burger tasted like an In-N-Out Burger. No, not exactly. And frankly, not as good. But it was a fair facsimile. If you’ve ever wanted to try America’s Best Regional Burger served under the glow of neon trees, this burger will get you close.

Final Thoughts

Considering everything from the early ’00s making a resurgence, from Linkin Park to Yu-Gi-Oh, this Spongebob Squarepants-style meal is a pretty successful attempt at tapping into that new millennium nostalgia. I came away happy from the experience, and there’s a good chance I’ll enjoy the Kollab Meal at least once more before the promotion ends. What I truly loved about this Spongebob Squarepants x Wendy’s collaboration was what it didn’t do. There was no unnecessary packaging. No cheap plastic toy destined for a landfill. And most of all, there wasn’t a cynical markup.

I bought two meals and only spent a little over $20—a veritable steal in today’s current fast food landscape. I joked for a month with friends, colleagues, and enemies that the Krusty Krab Kollab meal would “heal me,” as the popular meme says. And I’m happy to report that it kind of, sort of did. It’s difficult to be cynical when you’re eating a cartoon hamburger.

Originally published on Playboy.com.

0 notes

Text

Sitting in Lincoln Center awaiting the curtain for Ayad Akhtar’s McNeal—a much anticipated theater production starring Robert Downey Jr., with ChatGPT in a supporting role—I mused how playwrights have been dealing with the implications of AI for over a century. In 1920—well before Alan Turing devised his famous test and decades before the 1956 summer Dartmouth conference that gave artificial intelligence its name—a Czech playwright named Karel Čapek wrote R.U.R.—Rossum’s Universal Robots. Not only was this the first time the word “robot” was employed, but Čapek may qualify as the first AI doomer, since his play dramatized an android uprising that slaughtered all of humanity, save for a single soul.

Also on the boards in New York City this winter was a small black-box production called Doomers, a thinly veiled dramatization of the weekend where OpenAI’s nonprofit board gave Sam Altman the boot, only to see him return after an employee rebellion.

Neither of these productions have the pizzazz of a splashy Broadway extravaganza—maybe later we’ll buy tickets to a musical where Altman and Elon Musk have a dance-off—but both grapple with issues that reverberate in Silicon Valley conference rooms, Congressional hearings, and late-night drinking sessions at the annual NeurIPS conference. The artists behind these plays reveal a justifiable obsession with how superintelligent AI might affect—or take over—the human creative process.

Doomers is the work of Matthew Gasda, a playwright and screenwriter whose works zero in on the zeitgeist. His previous plays have included Dimes Square, about downtown hipsters, and Zoomers, whose characters are Gen-Z Brooklynites. Gasda tells me that when he read about the OpenAI Blip, he saw it as an opportunity to take on weightier fare than young New Yorkers. Altman’s ejection and eventual restoration had a definite Shakespearian vibe. Gasda’s two-act play on the topic features two separate casts, one depicting the Altman character’s team in exile and the other focused on the board—including a genuine doomer seemingly based on AI theorist Eliezer Yudkowsky, and a greedy venture capitalist—as they realize that their coup is backfiring. Both groups do a lot of gabbing about the perils, promise, and morality of AI while they snipe about their predicaments.

Not surprisingly, they don’t come up with anything like a solution. The first act ends with the dramatis personae taking shots of booze; in act two, the characters gobble mushrooms. When I mention to Gasda that it seems like his characters are ducking the consequences of building AI, he says that was intentional. “If the play has a message, it’s something like that,” he says. He adds that there’s an even darker angle. “There’s a lot of suggestions that the fictional LLM is biding its time and manipulating the characters. It’s up to audiences to decide whether that’s total hokum or whether that’s potentially real.” (Doomers is still running in Brooklyn and will open in San Francisco in March.)

McNeal, a Broadway production with a movie star who famously played a character based on Elon Musk, is a more ambitious work, with flashing screens that project prompts and outputs as if AI is itself a character. Downey’s Jacob McNeal, a narcissistic novelist and substance abuser, who gains the Nobel and loses his soul, winds up hooked on perhaps the most dangerous substance of all—the lure of instant virtuosity from a large language model.

Both playwrights are concerned about how deeply AI will become entangled in the writing process. In an interview in The Atlantic, Akhtar, a Pulitzer winner, says that hours of experimentation with LLMs helped him write a better play. He even gives ChatGPT the literal last word. “It’s a play about AI,” he explains. “It stands to reason that I was able, over the course of many months, to finally get the AI to give me something that I could use in the play.” Meanwhile, while Gasda gave dramaturgy credits to ChatGPT and Claude in the Doomers program, he worries that AI will steal his words, speculating that to preserve their uniqueness, human writers might revert to paper to hide their work from content-hungry AI companies. He’s also just finished a novel set in 2040 “about a writer who sold all of his works to AI and has nothing to do.”

Theater itself is probably the art least threatened by AI. Its essence consists of flesh-and-blood actors making words come to life on stage and forging a direct connection to an audience whose iPhones are (hopefully) deep in their pockets. As Akhtar said in the Atlantic interview, “There is something irreducibly human about the theater, and … over time, it is going to continue to demonstrate its value in a world where virtuality is increasingly the norm.” I found McNeal’s ending particularly powerful, as we learn that our protagonist has perhaps fallen too far into the rabbit hole of ChatGPT. The performance ends on an apparently chatbot-created Shakespearean note that left us not only wondering how much of the protagonist’s work was generated by AI but also whether the playwright had followed him into that same rabbit hole. I had the vertiginous feeling that reality itself had been bent by the newly fuzzy line between thought and algorithm. That’s good theater.

And then the lights went on in Lincoln Center and I was back in the mundane physical world, only to discover that the bald head inches from my knees in the seat in front of me belonged to the ultimate real-life AI accelerationist, Marc Andreessen. Even ChatGPT couldn’t have come up with a better plot twist.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

And they're not even the production company OR the distributor for that movie. They're just the sales rep.

Honey, Don't Production Company - Focus Features

The Materialists Production Companies - 2AM/A24/Killer Films Sales Rep - Sony Pictures Distributor - Stage 6 Films

Sacrifice Production Company - Iconoclast Entertainment Sales Rep - CAA Media Finance

(This is all info found on IMdB Pro) So the "only" CAA backed movies is hokum as well lol 🧜🏻♀️

Now they are saying he’s only doing CAA backed movies cause “he burned his bridges.”🤣🤣//

Right it’s not like the director/producer has a say in who gets cast🙄🙄🙄

If they didn’t want him he wouldn’t be there. CAA may help but they don’t have the end say.

They give CAA alot of power lmao

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hokum Returns to JCTC's Merseles Studios for Summer Edition

Jersey City, NJ - Hokum Productions returns to the Jersey City Theater Center on June 2nd for its summer edition. Advance tickets are on sale now at: ticketfly.com/event/1695828-jctc-music-hokum-jersey-city/. This showcase will feature the New Jersey swamp rock band Reese Van Riper, alternative Americana artist Dolly Rocker Ragdoll on tour from Ohio, as well as black roots artists Vienna Carroll and Keith Johnston. The event will be MC'ed by blues artist, Church of Satan priest, and Hokum co-founder, Darren Deicide. The summer edition returns after a sold out debut at the Jersey City Theater Center. Hokum Productions is dedicated to alternative roots music and culture, and thus, will be having tables including JC Oddities Market, Jersey City Food Not Bombs, and more to be announced. Saturday, June 2, Doors at 7pm Merseles Studios at the Jersey City Theater Center 339 Newark Ave., Jersey City, NJ $10 and tickets available in advance at ticketfly.com/event/1695828-jctc-music-hokum-jersey-city/

#hokum! productions#reverend darren deicide#merseles studios#Jersey City#alternative roots music#blues music#swamp rock#americana#reese van riper#dolly rocker ragdoll#Vienna Carroll#Keith Johnston

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

So (continuing on my Batshit Rigoletto Interpretation) i think the whole curse thing in the opera has a completely different dramaturgical meaning than most people actually ascribe it. it's simultaneously as important and not as important as it's made out to be in various productions. here's my thinking

first off, i don't think the curse is an actual, literal curse. interpretations that make this out to be the case also strip all the characters of any agency from that moment forward, removing much of the dramatic tension. and it opens up more plot holes- why does the curse seemingly only affect rigoletto, and not the duke? why does monterone imply in act 2 that his curse isn't supernatural? everything that constructs the actual 'effects' of the 'curse' are all very much pre-built aspects of character reaching their natural conclusions. also it gives the opera a distinct sense of hokum and is slightly ridiculous in its nature.

the second, counteractive idea to the first is that the curse actually does not matter at all dramaturgically and was only really included to give the opera a false sense of moralism. i would argue the opera already has a moral; it's just more directed at us the viewers than it is the characters. (there are multiple morals, perhaps. but the largest one calls us out. i'll get to that later.) as evidence of this idea people point to how the motif for the curse becomes less and less used over time, and how the entire plot could theoretically happen the exact same way even if the curse and all references to it were removed. which you'd THINK would make sense but the idea of monterone's curse is a string that runs through the play's beads of plot. it's a dramatic through-line and something of a measuring stick.

so here's my thinking: the curse is not a literal curse. it's a representation of a theme: turning on other outsiders in order to conform to society.

it is through monterone that this idea is first expressed because monterone is the grandest of all the 'outsiders' and, also, the closest to actually conforming to society. (i've seen multiple productions imply that monterone himself was once a courtier before being abandoned for growing out of their schemes and/or becoming too old for them, which i think is a really neat idea.) monterone commands a sort of dramatic power and image. it's also perhaps the most on the nose example, given that much of the things rigoletto mocks monterone for are traits that he also possesses. rig is mocking monterone not out of personal malice but because the courtiers goad him into doing so and because rig, despite hating the courtiers, wants so BADLY to be part of society in some way or another. monterone's curse affects rig not because rig particularly believes in curses but because rig understands damn well what it means: he's losing himself in pursuit of an ideal that will never come to pass, and that rattles him.

the idea of the curse reappears, from then on, in scenes that have to do with that exact idea. that's why it keeps appearing. it occupies rig's mind after the whole gilda-kidnapping episode because, in his desire to be 'part of the gang' and in on the courtiers' group of friends, he ended up endangering his own daughter. it comes up during pari siamo before that after rigoletto's long spiel of self-hatred, showing that ultimately his desire to conform hurts himself, too. it even comes up when rigoletto isn't on the stage: when sparafucile decides to kill someone else instead of the duke and pass them off as the duke's corpse to rig, the music eerily echoes the courtiers' musings after rigoletto is cursed, showing that ultimately, sparafucile in that moment is doing the same thing rigoletto did. and of course the curse comes up in its most violent and horrific musical form when gilda dies and rigoletto's own machinations of participating in societal conform (this time in committing an act of revenge, which had previously been established as a Common Language utilized by the courtiers) fail in the worst possible way.

however, while rig's fatal flaw is very much his need to conform, this opera is not a 'be yourself!' type story. there is no room or safety for being one's own self in this world. if you are disabled or otherwise marginalized, there is not the safety and freedom to be yourself. rigoletto's entire livelihood depends on his need to conform, and without that there would be no other jobs for him to pursue given his disability. the opera's moral is not given to its characters but to its audience: could you change this? could this have gone down differently in another place, another time?

there's no answer, of course. there never is.

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Line Noro and Jean Gabin in Pépé le Moko (Julien Duvivier, 1937)

Cast: Jean Gabin, Gabriel Gabrio, Mireille Balin, Saturnin Fabre, Fernand Charpin, Lucas Gridoux, Gilbert Gil, Marcel Dalio, Gaston Modot, LIne Noro. Screenplay: Henri La Barthe, Julien Duvivier, Jacques Constant, Henri Jeanson. Cinematography: Marc Fossard, Jules Kruger. Production design: Jacques Krauss. Film editing: Marguerite Beaugé. Music: Vincent Scotto, Mohamed Ygerbuchen.

When Walter Wanger decided to remake Pépé le Moko in 1938 as Algiers (John Cromwell), he tried to buy up all the existing copies of the French film and destroy them. Fortunately, he didn't succeed, but it's easy to see why he made the effort: As fine an actor as Charles Boyer was, he could never capture the combination of thuggishness and charm that Jean Gabin displays in the role of Pépé, a thief living in the labyrinth of the Casbah in Algiers. It's one of the definitive film performances, an inspiration for, among many others, Humphrey Bogart's Rick in Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1943). The story, based on a novel by Henri La Barthe, who collaborated with Duvivier on the screenplay, is pure romantic hokum, but done with the kind of commitment on the part of everyone involved that raises hokum to the level of art. Gabin makes us believe that Pépé would give up the security of a life where the flics can't touch him, all out of love for the chic Gaby (Mireille Balin), the mistress of a wealthy man vacationing in Algiers. He is also drawn out of his hiding place in the Casbah by a nostalgia for Paris, which Gaby elicits from him in a memorable scene in which they recall the places they once knew. Gabin and Balin are surrounded by a marvelous supporting cast of thieves and spies and informers, including Line Noro as Pépé's Algerian mistress, Inès, and the invaluable Marcel Dalio as L'Arbi.

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

I am not sure where the 500 years of oil number came from. Going by currently discovered reserves and assuming we don't discover more or change our rate of consumption we have roughly 50 years left till we run out of oil. Which given every nation's reluctance to try and find out things to use instead of oil could be why they don't ramp up production.

everyone has kept assuming that there won't be any more discoveries or innovations. I remember growing up and hearing that same "only 20-30 years left!!!1!" hokum. We'll be okay

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

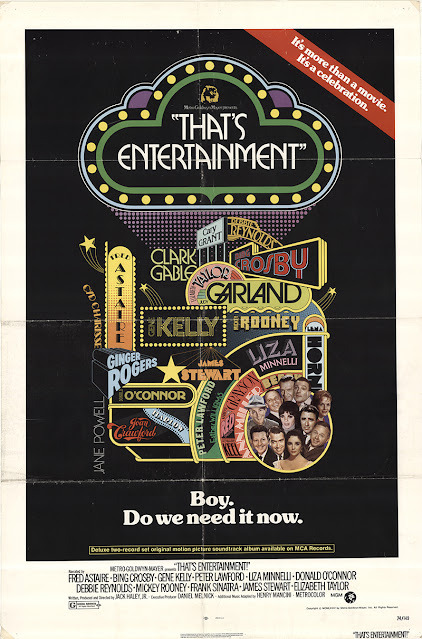

Doc/ Review Watch: That's Entertainment (1974)

Watched: 12/31/2022

Format: TCM

Viewing: First

Director: Jack Haley Jr.

I'm not clear on where this first showed - I guess wide release? It has a box office take listed, so I guess it was put out in theaters. Which is pretty wild. The movie is essentially a review/ clip show of MGM musicals and the greatest generator of a punchlist for movie nerds I can think of.

What's even wilder is that the movie was released as a 50th Anniversary celebration of MGM - and we're about 50 years from the release of this film. Time. It does roll on.

The film is hosted by an array of folks who were still living and vibrant, from Frank Sinatra to Bing Crosby to Elizabeth Taylor to a Mickey Rooney (who'll de damned if he's gonna shoot in the sun and manages the worst lighting you'll see in a major release as he wanders down a tree-lined sidewalk). But it's all a celebration of what made the movie musical great - and it makes a stunning case for the idea. Spectacle, talent, artistry and a bit of hokum all combine in an electric mix across about 100 clips supporting the thesis and the arguments presented for the musical.

Clips cover everything from the Depression-era Busby Berkley opuses to Andy Hardy films to Eleanor Powell, Ann Miller and of course Fred and Ginger (and Fred and Cyd). And a reminder that the most insane Hollywood may have ever gone was staging Esther Williams movies. It's impossible to imagine happening in the past 40 years.

1974 - the year of release - is an interesting inflection point. Liza Minnelli appears to remind you she's the daughter of Judy Garland and Vincent Minnelli and that she just won an Oscar for a musical. It's the promise of a new generation taking on musicals, which may have seemed possible in '74. But, clearly, that's not what happened. Sure, these days we get one or two a year, and most Disney cartoons are musicals for all intents and purposes, but as much as westerns would fade, musicals became a novelty. And, frankly, it seems like people my age feel weirdly threatened by musicals that don't start as Broadway shows.*

Trotting out the old guard is a fine idea for a retrospective, but in 1974, there's no home video. They weren't going to re-release 45 years of musicals, I don't think. So what was this for? One last hurrah and a trip down memory lane? The stars walk the now clearly dilapidated sets, around a decaying MGM lot, and I have to ask "why?" Why would MGM show their own sets in such a state of disrepair? I don't know what happened to MGM in the 1960's, but the story of MGM by the 1980's was about purchases, mergers, real estate sales... the company had gone from being a force of nature to a has-been. Even today, MGM seems to exist to put out Bond movies and not a whole lot else. If this film hoped to push people to clamor for musicals, I guess - not so much.

That said, it's a stunning reminder of what Hollywood - at least MGM - did on the regular to deliver wildly imaginative productions, the kind of talent they had on staff, and what movies can do. And maybe what we lost when the 1970's taught us to rely on "realism" in film, or at least pivoted us to space epics for our visions of flights of fancy.

Clearly Broadway tells us there's still an audience for musicals, and you do wonder - with today's techniques - what would an Esther Williams film look like? Who could star in it? Can an audience sit for a tap number? Do people still get swept up in ballroom dancing by the best, or just when it's a reality show with D-level stars trotted out for two minute numbers and people pretending to be judges?

And, honestly, even TCM doesn't play musicals like it used to. I'm sure the numbers track better to other kinds of films for whatever reason, but it would be nice to have some play of those big spectacle flicks.

MGM produced enough of these musicals that it spawned several sequels - That's Entertainment 2 and 3, as well as That's Dancing. So clearly they were making some money off of these things.

*I will never get the hostility to La-La Land

https://ift.tt/oC8A3vV

from The Signal Watch https://ift.tt/EwbolCf

1 note

·

View note

Photo

David Niven really loves Anthony Quayle, and Gregory Peck loves Anthony Quinn. Tony Quayle breaks a leg and is sent off to hospital. Tony Quinn falls in love with Irene Papas, and Niven and Peck catch each other on the rebound and live happily ever after.

- Gregory Peck explaining the plot of The Guns of Navarone (1961)

The Guns of Navarone is more than typical for a wartime adventure story. A team of roughneck military specialists is sent on a fool’s errand of certain death. You have the steel-eyed commando leader. The explosives expert. The cold-blooded killer, good with knives. The local boy looking for his shot. The aged, ethnic veteran of war. And the regular Joe, who just happens to have a certain knowledge that makes him ideal for a mission that must be completed. Given that the first four character types are, in this case, British, Navarone is strikingly reminiscent of The Bridge on the River Kwai.

The model the film offers is now a familiar one, as it was copied numerous times in the following decade, most notably by The Dirty Dozen, Where Eagles Dare and countless other fictional war stories of the 60s.

Based very loosely on an Alistair MacLean novel, it tells the story of a crack platoon of military misfits sent on a suicide mission to a Greek island in the Aegean Sea, where the Germans control the area with two huge artillery guns mounted in a cave. Sadly, as entertaining a notion as this all is, there is no island called Navarone, nor were there any big guns, or a mission to destroy them – it’s all pure hokum.

The film boasts a stellar cast in Gregory Peck, David Niven, Anthony Quinn, Stanley Baker, Anthony Quayle, James Darren, Irene Papas, Gia Scala, James Robertson Justice, and Richard Harris.

With such a large cast, some characters are often overlooked, but almost everyone I’ve mentioned gets at least one big scene, and the ones between Peck, Quinn and Niven are totally riveting. For Peck, it’s one of his less sympathetic roles, as the leadership of this band of miscreants ultimately drives him to sacrifice Anthony Quayle’s character to achieve the objective. But that’s exactly where Navarone is great, because it’s about the underlying tension between the characters, their allegiances and how the dynamic of the group alters during the story.

Gregory Peck firmly had his tongue in his cheek when promoting this classic war film by teasing the homoerotic themes that are not really there. Cinema-goers of the period were obviously far too excited by all the explosions and derring-do to notice. They also mostly missed the basic tenet of the story: that war destroys all those involved, irrespective of their virtues.Perhaps it’s worth forgiving those that missed all this, because the production values here are excellent. This was the most expensive movie made at the time, and looks it.

The Guns of Navarone is one of those films one can watch over and over again, like slipping into well worn slippers, and still feel comforted of what a good war movie should look like for mayhem, fighting, and a simple, sanctimonious story about heroism when it’s war at all costs. To me it’s one of the best ever war movies.

#gregory peck#quote#film#cinema#guns of navarone#war#war movie#david niven#anthony quayle#anthony quinn#alistair maclean#british#second world war#mission#classic#culture#personal

45 notes

·

View notes