#historian: steven gunn

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

There is no doubt that [Henry VII] exercised close personal oversight of every aspect of government, more so than most English kings before or since; but that did not make him a royal bureaucrat, toiling for long lonely hours at mountains of paperwork. His famous habit of signing account-books was, as K. B. McFarlane pointed out, no more than 'the ordinary practice of his magnates', and as the developing chamber administration required him to sign more often, he simplified his monogram to make the job less trouble. By 1504 his sight was failing and he found writing difficult; he gave up signing each entry in the chamber receipt accounts and signed only once on each page.

— Steven Gunn, The Courtiers of Henry VII | The English Historical Review

The surviving paperwork from the King's hand, and even that generated by his discussions with his ministers and entered in the memoranda sections of the treasurer of the chamber's accounts (which never covered more than two folios a month), certainly does not substantiate Pedro de Ayala's claim that Henry spent 'all the time he is not in public, or in his council, in writing the accounts of his expenses with his own hand'.

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

Didn't edward iv leave his brother Richard in lots of financial difficulties though?

No, he did not. I really don't know where this myth has originated from other than the persistent need to victimize Richard.

Firstly, Edward IV didn't leave Richard anything. Whatever he left was for his own son and heir, Richard's nephew, who Richard usurped.

Secondly, Edward IV was literally one of the rare few medieval kings of England to die solvent. He had managed to break the vicious cycle of plummeting debt and inefficiency that had plagued pretty much every single ruler till then. It doesn't really matter how much money the crown actually had left at the time of his death*, because the fact that he died solvent meant that whoever his successor was (in this case, Richard III), they were going to begin their reign with a financial advantage that no English monarch had enjoyed for the past 200 years. I don't know Richard's fans have convinced themselves that he inherited financial difficulties instead.

As stated by David Horspool, Richard's own historian:

"(Richard III) would try to differentiate himself from his brother, whose ‘unlawful invencions and inordinate covetise, ayenst the lawe of this roialme’ he would later denounce in an Act of Parliament. In fact Edward had managed to set royal finances back on an even keel after the disastrous waste and inefficiency of Henry VI (and all former kings post Henry II), Richard was, initially, the beneficiary of the better practise instituted by Edward IV.”

(The contemporary Croyland Chronicle mentions a main reason that Richard was better prepared to defend his kingship was "because of the treasure which he had in hand—since what King Edward had left behind had not yet all been consumed". They may have exaggerated the money Edward left behind, but either way it shows how contemporaries were aware of Richard's comparative advantages. It's highly ironic that what should have been used to uphold Edward's son was now being used to uphold his son's usurper instead).

Thirdly, Edward IV had presided over a highly effective and innovative combination of financial policies. These included the elevation/increase of royal chamber finance, the enlargement of the crown lands (Steven Gunn calls it "the most extensive royal demesne in medieval English History"), and an increase in royal feudal rights towards the end of his reign, among others**. Most importantly of all, he was actually successful, meaning that whoever followed him would have the huge benefit of having his established and well-attested precedent to continue from. Indeed, Charles Ross has noted how "Henry VII had the great advantage of being able to build upon the foundations laid by his father-in-law". Richard III, who seized the throne just a few months later, would have had the same advantages, as Horspool also notes.

Richard III, in fact, seems to have (temporarily) reversed some of his brother's well-established policies which could be used to gain money. Eg: he abolished benevolences; and he repealed Edward IV's newly established wardships and marriages act in the Duchy of Lancaster "notwithstanding that he conceiveth the said act to be to his great profit … having more affection to the common weal of this his realm and of his subjects than to his own singular profit". If you deliberately reverse policies with immense potential for revenue-raising, I don't know how you can then go on to complain that your brother left you nothing.

In conclusion: no, Edward IV did not leave Richard in financial difficulties. If anything, he left Richard with financial advantages that no king had had in over 200 years.

(Also, just to clarify: the Woodvilles did not steal the treasury. We know for a fact that Elizabeth Woodville did not have any money in sanctuary. The story of a theft was only mentioned by Mancini and either originated in gossip or, more likely, from Ricardian propaganda aiming to vilify them in 1483 by positioning them against the crown.)

*We know for a fact that Edward IV died solvent, but from what I understand, the exact money he had is impossible to know because of his missing chamber records. Contemporaries like Croyland did believe he had substantial money and treasure; on the other hand, Rosemary Horrox has analyzed how his cash reserves were probably relatively low due to international conflicts the previous two years. Either way, like I said, the main thing is that he was the first king in over 200 years to die solvent, which was massively advantageous to his successor. **While his policies were clearly innovative, they weren't all completely original. However, their combination certainly was; they were modified to actually work better; and they were initiated from the beginning of his first/second reign and widespread across the royal lands (rather than in smaller pockets), meaning that they were clear systematic policies. They were also, like I mentioned, actually successful - meaning that they would be the proven precedent that his successors would turn to.

#ask#richard iii#edward iv#this is the same logic as people who hail Richard for his 'peaceful' administration and reign#without understanding that he a peaceful country *from Edward IV*#it was already peaceful when he took over - he can't really be given the credit for making it peaceful on his own lol#Or claiming that Edward IV let a rivalry develop between Richard and the Woodvilles which 'forced' Richard to usurp the throne#when there is no evidence of any hostility between them and all indication of cooperation#and *Richard* was the one who provoked fear/hostility by arresting them and forcibly seizing the young king#Or claiming that Edward IV left great naval tensions with France with he died - when he had already begun making efforts to alleviate those#tensions and preserve his truce - something *Richard* chose to ignore to try and instigate France for no reason instead#Or claiming that Edward IV's manipulation of landed estates somehow led to his son's usurpation - conveniently ignoring how they were#successful during his life and would have been successful during his son's as well. Without *Richard* actively inflaming and exploiting#them to gain political support they wouldn't have mattered (Edward was not the first nor the last king to do this)#Or claiming that Edward IV's policies complicated matters for Richard / Richard III was reforming them when in fact we know that#Richard mostly tried to *follow* his brother's policies (with some exceptions that usually backfired)#or when historians (Pollard; Ross) blame Edward IV for failing to pass his crown successfully to his son#Conveniently ignoring how literally everyone expected and wanted Edward V to be crowned soon#And minimizing how the only reason that Edward V was usurped because his own uncle *Richard of Gloucester#decided to usurp him* and took active steps to make that happen#Somehow Richard's agency is always downplayed. Just look at Ross saying: 'Nor should Richard's own forceful character be overlooked'#at the very END of the list of reasons for a potential usurpation#Richard's 'forceful character' is literally the main reason the usurpation happened. If he had supported his nephew instead#none of this would have happened. This is ridiculously simple; HOW is it so difficult to understand?#Horspool says it best: 'Edward IV had not left a factional fault line waiting to be shaken apart. Richard of Gloucester's decision to usurp#was a political earthquake that could not have been forecast on April 9 when Edward IV died'#and#'Without one overriding factor - the actions of Richard Duke of Gloucester after he took the decision to make himself King Richard III -#none of this would have happened'#It's a very consistent pattern I've noticed. Edward IV is somehow held more responsible for Richard's usurpation than Richard himself

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Birthdays 7.29

Beer Birthdays

Max Schwarz (1863)

Garrett Oliver (1962)

Five Favorite Birthdays

Ken Burns; documentary filmmaker (1953)

Geddy Lee; rock bassist, singer (1953)

William Powell; actor (1892)

Dave Stevens; artist, cartoonist, illustrator (1955)

Wil Wheaton; actor, blogger (1972)

Famous Birthdays

Afroman; rapper (1974)

Jean-Hugues Anglade; French actor and director (1955)

Doug Ashdown; Australian singer-songwriter (1942)

Porfirio Barba-Jacob; Colombian poet and author (1883)

Melvin Belli; attorney (1907)

Clara Bow; actor (1905)

Danger Mouse; cartoon character (1977)

Don Carter; bowler (1926)

John Clarke; New Zealand-Australian comedian and actor (1948)

Edgar Cortright; scientist and engineer (1923)

Professor Irwin Corey; comedian, actor (1914)

Sharon Creech; author (1945)

Simon Dach; German poet (1605)

Alex de Tocqueville; French writer, historian, political scientist (1805)

Stephen Dorff; actor (1973)

Neal Doughty; keyboard player (1946)

Leslie Easterbrook; actress (1949)

Richard Egan; actor (1921)

Adele Griffin; author (1970)

Tim Gunn; fashion consultant, television host (1953)

Dag Hammarskjold; Swedish diplomat (1905)

Betty Harris; chemist (1940)

Jenny Holzer; painter, author, and dancer (1950)

Robert Horton; actor (1924)

Isabel; Brazilian princess (1846)

Peter Jennings; television journalist (1938)

Eyvind Johnson; Swedish novelist (1900)

Joe Johnson; English snooker player (1952)

Diane Keen; English actress (1946)

Eric Alfred Knudsen; author (1872)

Harold W. Kuhn; mathematician (1925)

Stanley Kunitz; poet (1905)

Don Marquis; cartoonist, writer (1878)

Jim Marshall; guitar amplifier maker (1923)

Martina McBride; country singer (1966)

Daniel McFadden; economist (1937)

Frank McGuinness; Irish poet and playwright (1953)

Goenawan Mohamad; Indonesian poet and playwright (1941)

Harry Mulisch; Dutch author, poet (1927)

Benito Mussolini; Italian journalist and politician (1883)

Gale Page; actress (1910)

Alexandra Paul; actor (1963)

Dean Pitchford; actor and director (1951)

Isidor Isaac Rabi; physicist (1898)

Don Redman; composer (1900)

Sigmund Romberg; Hungarian-American composer (1887)

Mahasi Sayadaw; Burmese monk and philosopher (1904)

Patti Scialfa; musician (1954)

Mary Lee Settle; novelist (1918)

Tony Sirico; actor (1942)

Randy Sparks; folk singer-songwriter (1933)

John Sykes; English singer-songwriter and guitarist (1959)

Booth Tarkington; writer (1869)

David Taylor; English snooker player (1943)

Paul Taylor; dancer (1930)

Mikis Theodorakis; Greek composer (1925)

Didier Van Cauwelaert; French author (1960)

David Warner; English actor (1941)

Woody Weatherman; guitarist (1965)

Vladimir K. Zworykin, Russian-American engineer and inventor (1888)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

In an article last month, I noted that this past April (April 2016), Amazing Stories had celebrated its 90th anniversary.

This is not entirely true. As many may know, magazine cover dates are the date after which the periodical should be removed from the shelves (and presumably replaced with the next issue). A magazine with a cover date of April is “out dated” come May 1st.

If you are familiar with that concept, then you also know that the “April” issue is usually placed on the stands approximately mid-way through the preceding month. In Amazing’s case, that would be March 12th, 1926 for the first (April 1926) issue.

Thanks to many SF and pulp historians (chief among them Michael Ashley), we actually have a birth date for the world’s first magazine devoted entirely to scientifiction.

But this presents a quandary. Most people looking at the magazine’s first issue when confronted with a March celebration will, at best be confused. At this present time in history, if they seek clarification, most sources will tell them that the first issue of the magazine was dated April. Surmounting that potential confusion will required an explanation every single time the birthday is announced.

So I’ve decided to split the baby. Hence forth, Amazing Stories birth day is March 12th. The magazine’s anniversary is celebrated in April, in honor of its cover date,

With that out of the way, we can celebrate Amazing Stories’ 90th January today (with no explanation needed or required).

January 2005, Volume 74, Number 1

Jeff Berkwitz, Editor Paizo Publishing

$5.99 per copy

Bedsheet 84 Pages

Contents

Nowhere in Particular by Mike Resnick The Wisdom of Disaster by Nina Kiriki Hoffman Brainspace shortstory by Robin D. Laws Jimmy and Cat shortstory by Gail Sproule Wishful Thinking shortstory by J. Gregory Keyes

Summer, 1998, Volume 70, Number 1*

Kim Mohan, Editor Wizards of the Coast

$4.00 per copy

Bedsheet 100 Pages

Contents Unbelievable – but True by Kim Mohan Dispatches (Amazing Stories, Summer 1998) by The Editor The Observatory: It All Started by Being Amazing by Bruce Sterling Scientifiction: From Silver Screen to Superstore

January, 1987 Volume 61, Number 5

Patrick Price, Editor TSR. Inc.

$1.75 per copy

Bedsheet 162 pages

Contents Among the Stones by Paul J. McAuley Forward from What Vanishes by Mark Rich Harbard by Larry Walker Max Weber’s War by Robert Frezza Kleinism by Arthur L. Klein Temple to a Minor Goddess by Susan Shwartz Upon Hearing New Evidence That Meteors Caused the Great Extinctions by Robert Frazier Transients by Darrell Schweitzer Light Reading by John Devin Vergil and the Caged Bird by Avram Davidson Snorkeling in The River Lethe by Rory Harper Able Baker Camel by Richard Wilson

March, 1977 Volume 50, Number 4*

Ted White, Editor Ultimate Publishing

$1.00 per copy

Digest 134 Pages

Contents Alec’s Anabasis Robert F. Young Shibboleth by Barry N. Malzberg Our Vanishing Triceratops by Joseph F. Pumilia and Steven Utley The Bentfin Boomer Girl Comes Thru by Richard A. Lupoff The Recruiter by Glen Cook Two of a Kind by Rich Brown Those Thrilling Days of Yesteryear by Jack C. Haldeman, II An Animal Crime of Passion by Vol Haldeman

February, 1967 Volume 40, Number 10*

Joseph Ross, Editor Ultimate Publishing

50 cents per copy

Digest 164 pages

Contents Two Days Running and Then Skip a Day by Ron Goulart Tumithak of the Corridors by Charles R. Tanner Methuselah, Ltd. by Richard Barr and Wallace West The Man with Common Sense by James E. Gunn Born Under Mars (Part 2 of 2) by John Brunner

January, 1957 Volume 31, Number 1

Paul W. Fairman, Editor Ziff-Davis Publshishing Company

35 cents per copy

Digest 132 pages

Contents Quest of the Golden Ape (Part 1 of 3) • serial by Paul W. Fairman and Milton Lesser [as by Ivar Jorgensen and Adam Chase ] Savage Wind • shortstory by Harlan Ellison Reluctant Genius by Henry Slesar Heart by Henry Slesar Before Egypt by Robert Bloch

January, 1947 Volume 21, Number 1

Raymond A. Palmer, Editor Ziff-Davis Publishing Company

25 cents per copy

Pulp 180 Pages

Contents I Have Been in the Caves by Margaret Rogers Rejuvenation Asteroid by William L. Hamling The Secret of Sutter’s Lake by Don Wilcox Like Alarm Bells Ringing by Robert Moore Williams The Mind Rovers by Richard S. Shaver Death Seems So Final by Richard S. Shaver Mr. Wilson’s Watch by H. B. Hickey

February, 1937 Volume 11, Number 1*

T. O’Conor Sloane, Editor Teck Publications

25 cents per copy

Pulp 148 pages

Contents The Planet of Perpetual Night by John Edwards Prometheus by Arthur K. Barnes “By Jove!” (Part 1 of 3)by Dr. Walter Rose Denitro by Stanton A. Coblentz The Last Neanderthal Man by Isaac R. Nathanson

January, 1927, Volume 1, Number 10

Hugo Gernsback, Editor Experimenter Publishing Company

25 cents per copy

Bedsheet 108 Pages

Contents The Red Dust by Murray Leinster The Man Who Could Vanish by A. Hyatt Verrill The First Men in the Moon (Part 2 of 3) by H. G. Wells The Man with the Strange Head by Miles J. Breuer, M.D. The Second Deluge (Part 3 of 4) by Garrett P. Serviss

Perhaps the most interesting statistic is that we’re producing a series of anthologies and facsimile reprint editions, drawn from all of these years of STF goodness and keeping them accessible.

If art is your thing, take a gander at the posters we’ve got for sale; if fiction is what you’re after, here are the titles we’ve currently got on sale – with more coming every month; (click on any cover to purchase).

#gallery-0-6 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-6 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 33%; } #gallery-0-6 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-6 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Best of 1926

Best of 1927

Best of 1928

Best of 1940

35TH Anniversary Issue

May 1940 Facsimile Edition

September 1940 Facsimile Edition

Amazing Stories Annual Facsimile Edition

Amazing Stories Classic Novels

Ammazing Stories 88th Anniversary Issue

Also note: this article could not have been prepared without the resources of ISFDB.ORG and Galactic Central – Philsp.com. We are continually grateful for the work that they do in preserving genre history.

*As always, we try to get as close to an actual anniversary issue as possible, but given Amazing’s interesting publishing history, this is not always possible.

The Amazing Years – January 2017 In an article last month, I noted that this past April (April 2016), Amazing Stories had celebrated its 90th anniversary.

0 notes

Quote

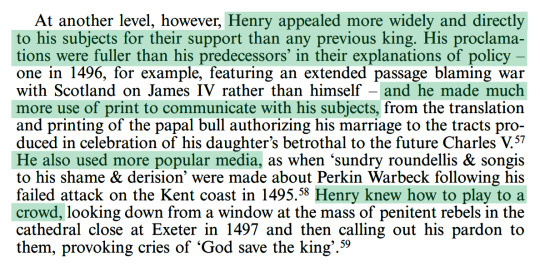

Charles the Bold was an ardent propagandist, sending out letters to local authorities justifying his policies, circulating inspiring accounts of great court festivities, expounding his view of princely powers and duties in the preambles to his ordinances and continuing the Burgundian tradition of a workshop of court historians fashioning favourable versions of the past and present. Edward IV began to commission similar official chronicles after his return from exile in the Netherlands, and made a practice of issuing royal proclamations in full and sometimes self-justificatory English texts, rather than bald Latin instructions to announce certain information.

Steven Gunn, State Development in England and the Burgundian Dominions, c.1460-c.1560

But it was Henry VII, perhaps inspired by Maximilian’s enthusiastic perpetuation of the Burgundian penchant for propaganda, who first appointed a court historian, first circulated accounts of diplomatics festivities (and did so in print), used fuller proclamations and the preambles to parliamentary statues — likewise printed by the king’s printer from 1504 — to explain himself to his people, and wrote to local authorities ordering celebrations of such successes as the Anglo-Burgundian marriage treaty of 1507 and expounding on their significance.

#as usual: henry vii wasn't an innovator#but simply very good at his job#edward iv#henry vii#charles the bold#historian: steven gunn

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Henry VII] followed the Yorkists in his personal judicial dynamism, sending out blistering letters like those to Sir William Say and Sir John Fortescue informing them that he had heard of their intention of confronting one another with 'unlawful assemblies and conventicles of our people' at the next sessions of the peace in Hertfordshire, warning them not to do anything 'repugnant to the equity of our laws or rupture of our said peace, at your uttermost peril', and summoning them to Westminster so he could deal with their dispute. From early in the reign, Henry used his council as a forum for this personal drive to impose good order, taking notes in his own hand of the witnesses' depositions when Lord Dacre of the North appeared before the council accused of riot in 1488-9.

— Steven Gunn, Early Tudor Government 1485-1558

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Others did benefit substantially from their proximity to Henry [VII], and they did so because the King valued their presence. Warrants ordering the prompt payment of annuities to his attendant esquires of the body were justified with their need to prepare themselves 'to attende upon us in this our next progresse', while an annuity unpaid to an esquire of the body whose 'great diseases' had prevented his daily attendance on the King was commanded to be paid notwithstanding his absence, on account of 'his long contynued s[er]vice doon unto us to our singler good pleas[ou]r'. The continuity of service among Henry's closest courtiers and the intensity of their attendance on the King lend substance to the claim of another warrant that he had 'singler regard unto the daily contynuell attenda[u]nce of our trusty s[er]v[au]nt[es]'.

— Steven Gunn, The Courtiers of Henry VII | The English Historical Review

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Thank you for the book recs - I’m currently gearing up to write a historical novel about one of H7’s controversial advisors (I know, I know, ambition is my fatal flaw), so recommendations on good biographies of H7 and EoY are always a good thing.

Hi! Oooh, would you tell me which advisor you're thinking about? There are some options that could be considered controversial. Empson and Dudley are the ones Tudor fans usually know about but Cardinal Morton, Sir Thomas Lovell, Sir Reginald Bray and Bishop Fox could also be considered controversial (and are especially hated by ricardians lol). I think there's one or more novels about Sir Thomas Lovell, actually.

When it comes to Henry VII's advisors I recommend Steven Gunn's book Henry VII's New Men and the Making of Tudor England. Gunn has also released some other articles on Henry's advisors so I would really recommend his work.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A key place in the spectrum of service was held by those noblemen who combined the King's confidence with great office at court, a position of regional authority which rested in part on the tenure of local offices in the King's gift, and senior diplomatic and military responsibilities. Such men were central to the process of late medieval state-building, and Henry VII had his Giles, Lord Daubeny, Robert, Lord Willoughby de Broke, and Charles Somerset, Lord Herbert, where Louis XI had his Georges de la Tremoille, Charles the Bold his Guy de Brimeu, Edward IV his William, Lord Hastings, Richard III his Francis, Viscount Lovell and Henry VIII his Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk and John, Lord Russel.

— Steven Gunn, The Courtiers of Henry VII | The English Historical Review

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Birthdays 7.29

Beer Birthdays

Max Schwarz (1863)

Garrett Oliver (1962)

Five Favorite Birthdays

Ken Burns; documentary filmmaker (1953)

Geddy Lee; rock bassist, singer (1953)

William Powell; actor (1892)

Dave Stevens; artist, cartoonist, illustrator (1955)

Wil Wheaton; actor, blogger (1972)

Famous Birthdays

Afroman; rapper (1974)

Jean-Hugues Anglade; French actor and director (1955)

Doug Ashdown; Australian singer-songwriter (1942)

Porfirio Barba-Jacob; Colombian poet and author (1883)

Melvin Belli; attorney (1907)

Clara Bow; actor (1905)

Danger Mouse; cartoon character (1977)

Don Carter; bowler (1926)

John Clarke; New Zealand-Australian comedian and actor (1948)

Edgar Cortright; scientist and engineer (1923)

Professor Irwin Corey; comedian, actor (1914)

Sharon Creech; author (1945)

Simon Dach; German poet (1605)

Alex de Tocqueville; French writer, historian, political scientist (1805)

Stephen Dorff; actor (1973)

Neal Doughty; keyboard player (1946)

Leslie Easterbrook; actress (1949)

Richard Egan; actor (1921)

Adele Griffin; author (1970)

Tim Gunn; fashion consultant, television host (1953)

Dag Hammarskjold; Swedish diplomat (1905)

Betty Harris; chemist (1940)

Jenny Holzer; painter, author, and dancer (1950)

Robert Horton; actor (1924)

Isabel; Brazilian princess (1846)

Peter Jennings; television journalist (1938)

Eyvind Johnson; Swedish novelist (1900)

Joe Johnson; English snooker player (1952)

Diane Keen; English actress (1946)

Eric Alfred Knudsen; author (1872)

Harold W. Kuhn; mathematician (1925)

Stanley Kunitz; poet (1905)

Don Marquis; cartoonist, writer (1878)

Jim Marshall; guitar amplifier maker (1923)

Martina McBride; country singer (1966)

Daniel McFadden; economist (1937)

Frank McGuinness; Irish poet and playwright (1953)

Goenawan Mohamad; Indonesian poet and playwright (1941)

Harry Mulisch; Dutch author, poet (1927)

Benito Mussolini; Italian journalist and politician (1883)

Gale Page; actress (1910)

Alexandra Paul; actor (1963)

Dean Pitchford; actor and director (1951)

Isidor Isaac Rabi; physicist (1898)

Don Redman; composer (1900)

Sigmund Romberg; Hungarian-American composer (1887)

Mahasi Sayadaw; Burmese monk and philosopher (1904)

Patti Scialfa; musician (1954)

Mary Lee Settle; novelist (1918)

Tony Sirico; actor (1942)

Randy Sparks; folk singer-songwriter (1933)

John Sykes; English singer-songwriter and guitarist (1959)

Booth Tarkington; writer (1869)

David Taylor; English snooker player (1943)

Paul Taylor; dancer (1930)

Mikis Theodorakis; Greek composer (1925)

Didier Van Cauwelaert; French author (1960)

David Warner; English actor (1941)

Woody Weatherman; guitarist (1965)

Vladimir K. Zworykin, Russian-American engineer and inventor (1888)

0 notes

Quote

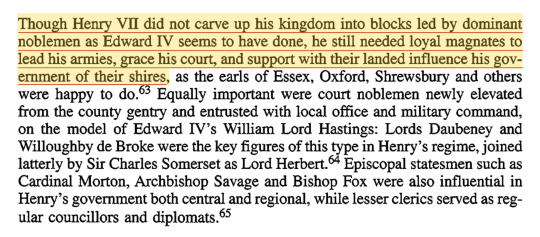

For historians working with McFarlanite models of later medieval political society, the key issue is the changing balance of power between peers and gentry in local politics, though the extent to which change was fostered by royal policy or came about autonomously as a result of the Wars of the Roses is more disputed. The notion that Henry [VII]’s government forged a special relationship with the gentry can be built into a satisfying model of a developing Tudor regime in which the court, the crown lands, the commissions of the peace and the commons in parliament all acted as points of contact between the king and the men who governed the shires.

Steven Gunn, Henry VII in Context: Problems and Possibilities

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sorry @realcatalina. I keep losing your replies in the middle of the new dashboard system, but yeah that was certainly a very noticeable trait about him and his reign. Another infamous example is the way he allowed and enabled his brothers to appropriate the inheritance of the dowager countess of Warwick (going so far as to declare her legally dead), the way he kept the Bohun inheritance from the young Duke of Buckingham, his decision to strip child Henry Tudor from his Richmond lands and give them to his brothers, the way he allowed his sister Anne to appropriate the inheritance of the Duke of Exeter, his treatment of young George Neville and his Salisbury inheritance, and the time Edward allowed Richard to bully the dowager countess of Oxford into handing over her lands to him.

When I was talking about how important his violent coming-of-age was, as well as the manner in which he took the throne, it's because it does seem to have informed the way Edward IV exercised his kingship. As Charles Ross said in his biography:

Edward never escaped from the rather old-fashioned proprietary notion of kingship implied in his own claim to the throne. This monarch who spoke of taking possession and seisin of the realm of England was the son of a great private landowner who now saw himself restored to an even greater inheritance from which his immediate forbears had been unjustly excluded. Moreover, he had grown to manhood during a struggle for power when the greed and land-hunger of the English aristocracy had been permitted their most naked expression. In an age of partisan government the competition for the profits and perquisites of political power had largely obscured the older ��medieval ideal of government by the king for the good of the whole community.’ It is scarcely surprising that a king of such preconceptions and background should have approached his position in terms of marked self-interest.

Pollard talked about Edward IV's inability to 'rise above factional politics'. It correlates to what I posted here. 'Fundamentally,' he said in his biography of Edward IV, 'Edward’s regime had remained to the very end the narrow rule of a victorious faction in civil war. Too much power in the provinces had been given to too few great lords personally close to the king.' There lies one of the main differences between Henry VII and Edward IV, and perhaps why Henry VII successfully safeguarded his dynasty whilst 'only half-hearted attempts had been made to unite the whole kingdom behind the [Yorkist] dynasty'. Henry VII made use of the printing press to circulate his proclamations and statues where, as stated by Steven Gunn, the words 'common weal, reformation, policy, peace, tranquillity or quietness, indifferent justice, punishment of wrongs, and remedies for idleness coursed through'.

In essence, as Pollard, Horrox and others have postulated, Henry VII's reign wasn't so much a 'New Monarchy' as a return to the royal authority enjoyed by the English monarchy at the beginning of the 14th century. That involved the concept of pax regis, and the enforcement of the English common law. Henry VII surrounded himself with his 'new men', all of them lawyers, a move that coincided with an ever-growing English interest at the end of the 15th century in the common weal of the realm. It ties up to Henry VII's decision to have the statutes of his parliaments printed and distributed in English instead of Law-French, so that ‘alle Englissmen’ could read them. Royal authority was enforced on all subjects, big or small—in theory no one, not even Henry VII's friends, was above the law.

#replies#edward iv#henry vii#historian: charles ross#historian: a. j. pollard#historian: steven gunn

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

— Steven Gunn, “New men” and “new monarchy” in England, 1485-1524

It was a measure of the new men’s skill but also of their importance to the king that these representatives of more traditional ruling groups did not reject them but formed very close bonds with them [...] But not everyone felt as happy with the new men as Daubeney or Oxford. Empson and Dudley discovered that, when they were arrested on the morning after the announcement of Henry VII’s death.

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Henry VII for the love meme? (I don’t think he’s been requested but if not then Anne Boleyn because I am Predictable ;)) <3

Oh my, I'm sorry I completely forgot about this ask! Ok, let's go:

love meme: put something in my inbox and i’ll tell you something i love about it

Henry VII: I suppose I really admire his strength of vision. Henry committed his whole self to his idea of uniting England under the crown and he made that happen not only by imposing his authority and driving royal policy but also by applying himself wholeheartedly to his work. He was quite an industrious man, and one could think that after a lifetime of having his inheritance denied and living like a hostage or a prisoner, he would dedicate himself solely to pleasure and pastimes after becoming the most powerful man in England. He had the political acumen to know that wouldn't last him long, though. Perhaps a survivor's mindset also factored into that. He never let himself feel too comfortable or safe. His story is extraordinary exactly because he had been the underdog for so long, and I think his success has got less to do with winning than with not giving up.

Pollard when talking about Edward IV said that the latter could really have united England under his rule but unfortunately, his reign was almost as much marked by factionalism as his predecessor (Henry VI)'s had been. 'Fundamentally,' Pollard says, 'Edward’s regime had remained to the very end the narrow rule of a victorious faction in civil war.' I think that perhaps it was necessary for someone that had stayed away from it all to read the country's situation with an unbiased mind and listen to both sides to heal old wounds. He integrated both Yorkists and Lancastrians into his regime and he reverted attainders that had injured both parties. This is the king that took men that had born arms against him like the Earl of Lincoln and welcomed them into his council, the very heart of his administration. He valued service and good counsel and a man could rise high in his regime by talent alone. Like Steven Gunn once said, there could never have been a Thomas Cromwell without the tradition of service to the crown initiated under Henry VII.

This 'direct line of civil servants administering the realm in the interests of the crown irrespective of the person of the king' can actually be traced back to Edward IV's reign. Those were men like John Fortescue and John Morton, but Henry VII made more use of them. I don't remember now who said that Henry VII had a real administrator's mind — I think that factor (an administrator's mind instead of a bubbling personality for example), coupled with a certain natural disposition made him smart enough to try to unite the whole kingdom not necessarily under himself, but under his heir. His son, aptly named Arthur, would be the 'once and future king', and that was all the message that was required. Though Henry is not particularly remarked as charismatic nowadays, he had a true talent for PR. A whole life having to live off appearances alone must have made him very attuned to that kind of thing.

The joining of the red and white roses was just brilliant as a PR stunt. Some people think it was just a cheap rip-off of the Yorkist white rose but setting aside the fact that Welsh poets were calling him the red rose before he had even landed in Britain (and his use of Welsh prophecy is a whole other brilliant thing), I think people just don't know the strong Marian connotations that white and red roses possessed in the late middle ages. We know Henry VII was particularly devoted to the Virgin Mary, and Mary was said to be a rose both white and red. The way I see it, the joining of the roses was not just the union of two factions at war, it involved a deeper religious meaning where Mary's white qualities (such as her purity) could be reunited with her red qualities (such as her charity). Before his children were even born Henry was already advertising that value. Henry VII understood the emphasis he needed to put on his heir, he knew how to create a commitment to his dynasty under his son so that the crown could be passed down peacefully.

Henry VII succeeded in that regard, but it wasn't an easy process. As far as 1504 there were people who weren't planning on crowning his son after his death. He didn't give up until his family and heir were safe, even though this man was literally ill with tuberculosis during the last years of his reign. Saying that is not the same as claiming Henry VII had some moral high ground, for that was just his tenacity and stubbornness — the same tenacity that made him escape so many attempts against his life by the skin of his teeth when he was young. Pollard mentions how Henry VII hung on until his heir was old enough to succeed him even though he had been at death's door so many times, and I think his herculean effort deserves some credit. He was very obstinate, and I can't help but admire that. He was also very lucky in a lot of ways, and he knew how to grasp that opportunity/luck when it presented itself to him.

Henry never vacillated in a moment of crisis, and I think that strong grip, combined with a more open mind acquired after a lifetime living on the Continent understanding the politics of Europe and away from the factionalism in England — I think that very combination in a monarch was just what the kingdom needed at the time. He wasn't flamboyant but it is his very seriousness and commitment that I admire in him. I hope I didn't ramble too much, though! Thank you for sending this ask, darling! 🌹x

P.S.: This answer was already sufficiently long but I think that Henry VII's patronage of the arts should be brought up more. Despite popular belief that he was a miser, Henry VII spent liberally on his court and Tudor patronage as we know it was very much shaped by his own. Henry VII founded a royal school of Flemish illuminations in England, he created the offices of royal librarian, royal portraitist and royal 'arras maker' (for tapestries), as well as transforming the office of king's glazier into a year-round job. He was a patron of the printing press at Westminster and of Mary of Burgundy's school of painting in Flanders. He supported poets and scholars at his court (called 'laureates'), men like Bernard André and Polydore Vergil but also Skelton, Hawes, Cornish and Pietro Carmeliano whom he provided with annuities. Henry also supported not just one but three troupes of actors, and two minstrel companies. He virtually institutionalised the patronage of arts in England through offices in the royal household, and that's something I admire about him too.

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

His coinage was shaped to link his subjects to him, with the first realistic profile portraits ever used on English silver coins. Some have doubted how effectively the coinage conveyed political messages, but people certainly noticed the change, the author of the Great Chronicle of London noting the issue of ‘newe coynys ... which bare but half a fface’. Henry also demanded active responses, encouraging more public celebration of his diplomatic, military and dynastic successes than his predecessors and meeting success in the triumphs held for Princess Mary’s betrothal at Shrewsbury and Dover.

— Steven Gunn, “Henry VII in Context: Problems and Possibilities.” History, vol. 92 (2007)

#henry vii#dailytudors#there are those who forget that henry#spent his whole exile with nothing but his own reputation#to recommend him; he literally had spent years#perfecting his own image#--not saying he was a mastermind#only that he wasn't clueless#historian: steven gunn#henry vii in context: problems and possibilities

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

Obsessed with this story:

Imagine being called Henry Winslow and trying to make King Henry VII laugh by way of a bawdy joke and words ‘not worth here to be repeated’... oof and cringe.

40 notes

·

View notes