#hirobumi ito

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I drew Ito from Rise of the Ronin using Ohioboss Satoyu as a reference

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

🌟 Ready for a challenge? Explore the mission A Vow of Steel in Rise of the Ronin! Fight alongside Hirobumi Ito and Aritomo Yamagata, test your skills against tough opponents, and experience a story filled with growth, respect, and determination!

#Rise Of The Ronin#AVow Of Steel#Edo 1868#Action RPG#Gaming Community#Hirobumi Ito#Aritomo Yamagata#Jigoro Kano#Character Development#Boss Battles#Gaming Strategy#Game Objectives#Combat Skills#Martial Arts#Game Rewards#Role Playing Game#Japanese History#Video Game Narrative#Dialogue Choices#Character Relationships#Gaming Challenges#Victories And Struggles#Gaming Culture#Video Game Characters#Game Lore#Epic Battles#Growth Through Struggle#Game Review#Game Enthusiast#Honor And Triumph

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Her Room ひとりぼっちじゃない (2022) Director: Chihiro Ito [New York Asian Film Festival 2023] 2

In Her Room ひとりぼっちじゃない 「Hitori Bocchi Janai」 Release Date: March 10th, 2023 Duration: 135 mins. Director: Chihiro Ito Writer: Chihiro Ito (Screenplay/Original Novel), Starring: Fumika Baba, Satoru Iguchi, Yuumi Kawai, Hirobumi Watanabe, Kazuyuki Aijima, Website IMDB In Her Room is veteran screenwriter Chihiro Ito’s debut film. It is based on a novel she wrote and is an impressive achievement…

View On WordPress

#ひとりぼっちじゃない#Chihiro Ito#Fumika Baba#Hirobumi Watanabe#In Her Room#Japanese Film#Japanese Film Review#New York Asian Film Festival 2023#Satoru Iguchi#Yuumi Kawai

1 note

·

View note

Text

She doesn't even know Japan occupied Korea in 1905 after the Russo-Japanese war and ruled the country as a protectorate after that, with 1910 only demarcating its formal annexation into the Japanese Empire; you gotta turn her down -_-

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

2024 Book Review #41 – Japan 1941: Countdown to Infamy by Eri Hotta

Almost everything I know about World War 2, I learned against my will through a poorly spent adolescence and reading people argue about it online. Living in Canada, Japan’s role in it is even more obscure, with the wars in the Pacific and China getting a fraction of a fraction of the official commemoration and pop culture interest of events in Europe. So I went into this book with a knowledge of only the vague generalities of Japanese politics in the ‘30s and ‘40s – from that baseline, this was a tremendously interesting and educational book, if at times more than a bit dry.

The book is a very finely detailed narrative of the internal deliberations within the Japanese government and the diplomatic negotiations with the USA through late 1940 and 1941, which ultimately culminate in the decision to attack Pearl Harbour and invade European colonies across the Pacific. It charts the (deeply dysfunctional) decision-making systems of the Imperial Japanese government and how bureaucratic politics, factional intrigue and positioning, and an endemic unwillingness to be the one to back down and eat your words, made a war with the USA first possible, then plausible, then seemingly inevitable. Throughout this, the book wears its thesis on its sleeve – that the war in the Pacific only ever seemed inevitable, that until the very last hour there was widespread understanding that the war would be near-unwinnable across the imperial government and military, but a broken political culture, the career suicide of being the one to endorse accepting American demands,, and a simple lack of courage or will among the doves, prevented anything from ever coming of it.

So I did know that Imperial Japan’s government had, let’s say, fundamental structural issues when I opened the book, but I really wasn’t aware of just how confused and byzantine the upper echelons of it were. Like if Brazil was about the executive committee – the army and navy ministries had entirely separate planning infrastructures from the actual general staffs, and all of them were basically silo’d off from the actual economic and industrial planning bureaucracy (despite the fact that the head of the Cabinet Planning Board was a retired general). All of which is important, because the real decisions of war and peace were made in liaison meetings with the prime minister, foreign minister, and both ministry and general staff of each branch – meetings which were often as not just opportunities for grandstanding and fighting over the budget. The surprise is less that they talked themselves into an unwinnable war and more that they decided on anything at all.

The issue, as Hotta frames it, is that there really wasn’t a single place the buck stopped – officially speaking, the civilian government and both branches of the military served the pleasure of the Emperor – whose theoretically absolute authority was contained by both his temperament and both custom and a whole court bureaucracy dedicated to making sure the prestige of the throne didn’t get mired in and discredited by the muck of politics. The entire Meiji Constitution was built around the presence of a clique of ‘imperial advisers’ who could borrow the emperor’s authority without being so restrained – but as your Ito Hirobumis and Yamagata Aritomos died off, no one with the same energy, authority and vision ever seems to have replaced them.

So you had momentous policy decisions presented as suggestions to the emperor who could agree and thus turn them into inviolable commands, and understood by the emperor as settled policy who would provide an apolitical rubber-stamp on. Which, combined with institutional cultures that strongly encouraged being a good soldier and not undercutting or hurting the image of your faction, led to a lot of people quietly waiting for someone else to stand up and make a scene for them (or just staying silent and wishing them well when they actually did).

Now, this is all perhaps a bit too convenient for many of the people involved – doubtless anyone sitting down and writing their memoirs in 1946 would feel like exaggerating their qualms about the war as much as they could possibly get away with. I feel like Hotta probably takes those post-war memoirs and interviews too much at face value in terms of people’s unstated inner feeling – but on the other hand, the bureaucratic records and participants’ notes preserved from the pivotal meetings themselves do seem to show a great deal of hesitation and factional doubletalk. Most surprisingly to me was the fact that Tojo (who I had the very vague impression was the closest thing to a Japanese Hitler/Mussolini there was) was actually chosen to lead a peace cabinet and find some 11th hour way to avert the war. Which in retrospect was an obviously terrible decision, but it was one he at least initially tried to follow through on.

If the book has a singular villain, it’s actually no Tojo (who is portrayed as, roughly, replacement-rate bad) but Prince Konoe, the prime minister who actually presided over Japan’s invasion of China abroad and slide into a militarized police state at home, who led the empire to the very brink of war with the United States before getting cold feet and resigning at the last possible moment to avoid the responsibility of either starting the war or of infuriating the military and destroying his own credibility by backing down and acceding to America’s demands. He’s portrayed as, not causing, but exacerbating

every one of Japan’s structural political issues through a mixture of cowardice and excellent survival instincts – he carefully avoided fights he might lose, even when that meant letting his foreign minister continue to sabotage negotiations he supported while he arranged support to cleanly remove him (let alone really pushing back on the army). At the same time, the initiatives he did commit were all things inspired by his deep fascination with Nazi Germany – the dissolution of partisan political parties and creation of an (aspirationally, anyway) totalitarian Imperial Rule Assistance Association, the creation of a real militarized police state, the heavy-handed efforts to create a more pure and patriotic culture. He’s hardly to blame for all of that, of course, but given that he was a civilian politician initially elected to curb military influence, his governments sure as hell didn’t help anything (and it is I suppose just memorably ironic that he’s the guy on the spot for many of the most military-dictatorship-e aspects of Japanese government).

One of the most striking things about the book is actually not even part of the main narrative but just the background context of how badly off Japan was even before they attacked the United States. I knew the invasion of China hadn’t exactly been going great, but ‘widespread rationing in major cities, tearing up wrought iron fencing in the nicest districts of the capital to use in war industry’ goes so much further than I had any sense of. The second Sino-Japanese War was the quintessential imperial adventure and war of choice, and also just literally beyond the material abilities of the state of Japan to sustain in conjunction with normal civilian life. You see how the American embargo on scrap metal and petroleum was seen as nearly an act of war in its own right. You also wonder even more how anyone could possibly have convinced themselves that an army that was already struggling to keep its soldiers fed could possibly win an entirely new war with the greatest industrial power on earth. Explaining which is of course the whole point of the book (they didn’t, in large part, but convinced themselves the Americans wouldn’t have the stomach for it and agree to a favourable peace quickly, or that Germany would conquer the UK and USSR and impose mediation on Japan’s terms, or-).

When trying to understand the decision-making process, I’m honestly reminded of nothing so much as the obsession with ‘credibility’ you see among many American foreign policy hands in the modern day. The idea that once something had been committed to – the (largely only extant on paper) alliance with Nazi Germany, the creation of a collaborator government in China to ‘negotiate’ with, the occupation of southern Vietnam – then, even if you agreed it hadn’t worked out and had probably been a terrible decision to begin with, reversing course without some sort of face-saving agreement or concession on the other side would shatter any image of strength and invite everyone else the world over to grab at what you have. The same applies just as much to internal politics, where admitting that your branch couldn’t see a way to victory in the proposed war was seen as basically surrendering the viciously fought over budget, no matter the actual opinions of your experts – the book includes anecdotes about both fleet admirals and the senior field marshal China privately tearing their respective superiors in Tokyo a (polite) new one for the bellicosity they did not believe themselves capable of following through on, but of course none of these sentiments were ever shared with anyone who might use them against the army/navy.

The book is very much a narrative of the highest levels of government, idea of mass sentiment and popular opinion are only really incidentally addressed. Which does make it come as a shock every time it’s mentioned that a particular negotiation was carried out in secret because someone got spooked by an ultranationalist assassination attempt the day before. I entirely believe that no one wanted to say as much, but I can’t help but feel that people’s unwillingness to forthrightly oppose further war owed something to all the radical actors floating around in the junior ranks of the officer corps who more than willing to take ‘decisive, heroic action’ against anyone in government trying to stab the war effort in the back. Which is something that the ever-increasing number of war dead in China (with attendant patriotic unwillingness to let them die ‘for nothing) and the way everyone kept trying to rally the public to the war effort with ever-more militaristic public rhetoric assuredly only made worse.

That same rhetoric also played its part in destroying the possibility of negotiations with the United States. The story of those negotiations runs throughout the book, and is basically one misunderstanding and failure to communicate after another. It at times verges on comedy. Just complete failure to model the political situation and diplomatic logic of the other party, on both sides (combined with a great and increasing degree of wishful thinking that e.g. letting the military occupy southern French Indochina as a concession for their buy-in on further negotiations would be fine with the Americans. A belief held on exactly zero evidence whatsoever). The United States government was actually quite keen to avoid a war in the pacific if possible, as FDR did his best to get entangled in Europe and effectively start an undeclared naval war with Germany – but the negotiating stance hardened as Japan seemed more and more aggressive and unreliable, which coincided exactly with Japan’s government taking the possibility of war seriously enough to actually try to negotiate. It’s the same old story of offering concessions and understanding that might have been agreed to a few months beforehand, but were now totally unacceptable. In the end, everyone pinned their hopes on a face-to-face diplomatic summit with FDR in Juneau, where sweeping concessions could be agreed to and the government’s credibility staked on somewhere the hardliners could not physically interfere with. The Americans, meanwhile, wanted some solid framework for what the agreement would be before the summit occurred, and so it never did.

After the war, it was apparently the general sentiment that the whole nation was responsible for the war with the United States – which is to say that no individual person deserved any special or specific blame. Hotta’s stated aim with the book is to show how that’s bullshit, how war was entirely avoidable, and it was only do to these small cliques of specific, named individuals that it began. The hardliners like Osami Nagano, but just as much the cowards, careerists and factional partisans like Konoe, Tojo, and (keeper of the Privy Seal) Kido. Having read it I, at least, am convinced.

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

Imagine, back in the 1800s, an enslaved person, let's all them "A", assasinated a slave trader to free fellow enslaved people. Do you think descendants of A should feel sorry for the slave trader?

Imagine, back in 1943, a Jewish person, Let's call them "B", who was sent to a camp, assassinated a nazi officer to free other Jewish people from the camp. Do you think Jewish people nowadays should not be proud of B in fear of hurting german people's feelings?

Now explain to me why Japanese people are canceling Han So Hee and calling her "anti japan" because she posted a picture of An Jung-geun, a korean independent activist who assasinated the colonizer ito hirobumi?

58 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A picture postcard of Gifu Kanazuen's courtesan journey... Before the war, Kanazuen was located in what is now Nishiyanagase, and was a big geisha district with Asanoya, where Hirobumi Ito played. Although it is monochrome, it reminds me of the gorgeous appearance of Oiran. It must have taken a lot of effort and skill to walk in these clogs. Text by Ryohei Masawaki

114 notes

·

View notes

Note

to get the most on-brand one for you I can think of out of the way - VOR for Itō Hirobumi?

Man, all of these really do need essays, I alas lack the spoons/time for that now, so it will just be some thoughts. Ito Hirobumi is a great case! For those who don't know, one of the 'founding fathers' of the Meiji Restoration and Japan's first and longest-serving Prime Minister.

As Meiji "revolutionary" is VOR is very high - he is one of the "Chosu five" who were (illegally!) sent to study abroad in the United Kingdom as youths, which pivoted him from a reactionary to someone, awed by Britain's power, committed to modernizing and westernizing Japan. While that process was inevitable, it being done on Japan's terms was far from inevitable - many wanted to resist western systems & norms. He also had several unique relationships with westerners that paved the way for foreign expertise on everything from railways to bureaucratic design. So in 1871 in particular, when he was building ministries for the new government and eventually became the Minister of Public Works in 1873, he was building a modernized, western systems that many others would not have wanted to build, or not known how to build. Japan's transition in the 1870's would have been notably messier without him.

Later on as Prime Minister his VOR declines. He adopts "consensus centrism" as his modus operandi, privileging stability over reform in the retrenchment era of the 1880's. Not a bad decision, but it was also not nearly as contested, he was making decisions others would have made. And he fails to anticipate the rise of political parties, suffering defeats later at the hand of the Kenseito faction that honestly better leaders would have seen coming. He was a ministry man first, politician second in some ways.

He did play a notable role in the resolution of the 1885 Qing-Japan crisis over Korea - after a failed, Japanese-sponsored coup in 1884 that China helped crush, de-facto war in Korea existed between the two factions which his personal intervention quashed with the Convention of Tientsin that normalized relations for the next decade. From my understanding, this was something he very much championed, with other factions in the government being muddled or bellicose, and it came from his experience as the tax minister understanding that Japan's economic growth was being driving by a complex import-export supply chain around textiles and raw materials with China, which Japan did not want to disrupt. This moment is a high VOR moment for him imo, way better to wait for a decade.

Certainly would love to know more, you ideally truly do go case in these scenarios.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Someone really argued with me that what happened to ORV's webtoon and e-book is not censorship. Bruh, 4 biggest glaring censorship happened when these things changed, some context completely erased:

"Korean Empire Invader" is Ito Hirobumi. A fascist Japanese prime minister.

He was the constellation supporter of Yamamoto Hajime who had a stigma called "colonization" .

Ito was assassinated by An Junggeun, a Korean activist who is the constellation supporter of Lee Boksoon called "Harbin Sniper".

If that censorship of Korean history is not enough, they gave the arc a Japanese culture of youkai versus omyouji. So basically in order to make it palatable to Japanese fans, history got redacted and Japanese influence was inserted in it. It's like Japan is invading again. How badly do you know about history and literature to deny censorhip that happened with that just because the anti Japan arc stayed?

Censorship is gross and Japan takes all the blame for that because they can't deal with their history. They can't respect the countries they bastardized.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

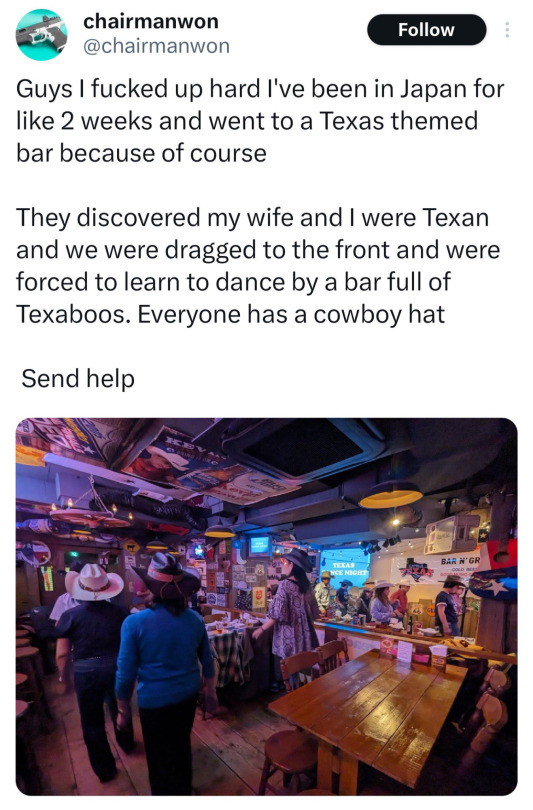

the uncanny resemblance to a real shit texan bar suggests some modern day ito hirobumi came back from that grim land with a desire to bring bad beer and worse music home with him

111K notes

·

View notes

Text

'Harbin' review: Impresses with visuals but falters in storytelling

Harbin delivers stunning cinematography and a powerful score but struggles to craft a compelling narrative about Ahn Jung-geun’s heroic journey.

“Harbin.” CJ Entertainment Woo Min-ho’s Harbin delivers a visually stunning portrayal of Ahn Jung-geun, a revered Korean independence fighter, but falls short in crafting a captivating narrative. The movie highlights Ahn’s mission to assassinate Ito Hirobumi, a key figure in Japan’s colonization of Korea. While the film’s cinematography and score are remarkable, its storytelling leaves much to…

0 notes

Text

Ahn Jung-geun - Korean Independence Activist (안중근) [Korean History 57]

In this video, I will discuss the life and achievements of Ahn Jung-geun (1879-1910), a Korean independence activist who dedicated his life to making Korea independent from Imperial Japan. He is most famous for his assassination of Ito Hirobumi 伊藤 博文, an important Japanese politician. Ito Hirobumi was the first prime-minister of Japan and the first resident-general of Korea. This event is…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

An Interview with Chihiro Ito, Director of In Her Room ひとりぼっちじゃない (2022) [New York Asian Film Festival 2023]

In Her Room is veteran screenwriter Chihiro Ito’s debut film. It is based on a novel she wrote and is an impressive achievement in style as it gives a refreshing cinematic spin on a familiar story of a jealous lover learning to let go. That is how my review opens and the rest of the writing is dedicated to describing how this fine film works so brilliantly because it comes from a writer/director…

View On WordPress

#ひとりぼっちじゃない#Chihiro Ito#Film Interview#Fumika Baba#Hirobumi Watanabe#In Her Room#Japanese Film#New York Asian Film Festival 2023#Satoru Iguchi#Yuumi Kawai

1 note

·

View note

Text

Dialogue with Gemini (1) History of exchange between Japan and Britain

Q: It would be good to cover the history of exchanges between Japan and Britain in an NHK taiga drama. The history of friendship such as the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, the history of hostility such as the Imphal Operation in World War II, and the history of reconciliation after the war. What plot could be written for a drama between geopolitically similar island nations?

A: Title: Across the Ocean: A Tale of Two Islands(plot)

The story begins in the late 16th century, during the seclusion period of Japan (Sakoku). A young shipwrecked English sailor, William Adams, finds himself on Japanese shores. With the help of a kind samurai, he integrates into Japanese society, becoming an advisor to the powerful Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu. Adams acts as a bridge between the two cultures, fostering initial trade relations. (This reflects the early positive exchanges)

Fast forward to the late 19th century. Japan is undergoing rapid modernization, and the British Empire is a dominant global power. The drama follows a young Japanese diplomat, Ito Hirobumi, who travels to London to negotiate the Anglo-Japanese Alliance. The alliance, born out of mutual strategic interests against Russia, showcases the complex dance between cooperation and competition between island nations. (This reflects the period of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance)

The narrative then shifts to World War II. A Japanese soldier, Tanaka Soichiro, finds himself fighting in the brutal Imphal Operation against British forces in India. Witnessing the horrors of war and the cultural similarities between the fighting soldiers, Soichiro questions the path his nation has taken. (This reflects the period of hostility)

Post-war, the drama follows the story of a Japanese woman, Sato Hana, who travels to London to pursue her studies. She encounters prejudice but also finds friendship and understanding with a young British historian, Thomas Moore. Together, they grapple with the legacy of the war and the importance of reconciliation. (This reflects the period of reconciliation)

This NHK taiga drama would showcase the evolving relationship between Japan and Britain, reminding viewers of the shared humanity that transcends geographical distance and political conflict.

#Dialogue with Gemini#Japan#Britain#rei morishita#Anglo-Japanese Alliance#friendship#Imphal Operation#hostility#reconciliation#geopolitics

1 note

·

View note

Text

Watch "Excavation of the Grave of a Woman from the Jinju Ha Family Clan" on YouTube

youtube

Korean used to write Chinese letter but Ming dynasty China made this latter for chinese letter so Mongo. Uigru and Korea made own Alphabet as their own langue because they were not chinese and didn't involving with them except diplomatic deal or issue. Chinese Ming dynasty was befor Qing dynasty and Ming dynasty China gone by manchurisn and Japanese like Wiansky? Or Oneuri of manchurian, Ito Hirobumi of manchrian Japanese and voyage people ruined Far East Asia with new arms. This trio are same souls

0 notes

Text

Bae Jeong-nam, a new start as an actor

Bae Jeong-nam gave it meaning that he announced a new start as an actor through 'Hero'.

Through the movie 'Hero', Bae Jung-nam broadened his acting spectrum by adding a sense of weight while slightly departing from the existing comical image.

In a recent interview with Herald POP at a cafe in Samcheong-dong, Jongno-gu, Seoul, Bae Jeong-nam revealed his expectations for the future as an actor.

'Hero' depicts the last unforgettable year from the time Ahn Jung-geun, who died in Harbin in October 1909, was sentenced to death by a Japanese court after killing Hirobumi Ito, preparing for the death. . Director Yoon Je-gyun's first new film in 8 years raised expectations early.

"I didn't even know that this work existed, so I just greeted the director with the introduction of the representative. Afterwards, he gave me a scenario and asked me to read it and give an answer. It's a work where a master and 'Hero' met, so it's an honor to go out at least Hanshin. God I said I would do my best on the spot without knowing how much it would be. I read the scenario later and it was hot. It was the first time I was given a character like this, so I was happy."

Bae Jeong-nam played the role of Jo Do-seon, the best marksman of the independence army in the play. 'Jo Do-seon', who makes a living by running a laundry in Vladivostok, is a person who saves comrades in the Independence Army with precise sniping skills at every moment of crisis. Accordingly, Bae Jung-nam learned and practiced everything new about shooting, from various shooting postures to the center of gravity according to the length of the gun.

“The director told me that he is a real person and that snipers should come out cool, so I wanted to do something cool, so he asked me to make it well. It was helpful because I learned a lot about posture and look in ‘Berlin’.”

0 notes