#hes written one of the most successful teen lit series of all time

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

How do I say, without coming across as a jaded miserable little bitch who likes raining on everybody's parade, that the PJO Disney plus adaption is nostalgia bait, in the same way that their live action remakes are

#it'll probably be good#it sounds like its gonna be a pretty faithful adaption#im not denying that#but#20-30 something year old you ARE being pandered to by the Walt Disney Corporation#its fine to be excited for it. just so long as we are all aware of whats happening#also we gotta stop acting like mr riordan is some underdog in this situation#hes written one of the most successful teen lit series of all time#and in disney's current quirky girl phase of grasping hold of anything that already has a following#of COURSE they snatched this shit up#''Percy Jackson. A Disneyplus original.''#do you have any idea just how much theyre salivating to have their name attached to this series?#(tbf the books were owned by disney too. but a streaming service makes their link to the franchise all the more evident)#anyway. maybe i sometimes get a little bitter when i think about all the original projects in production that were abruptly cancelled#usually because of the current fear to take risks and put something new into the world#and then i remember adaptions like are going ahead#there is no risk associated the pjo series. the first few books are relatively squeaky clean for a teenage audience#this is a comfortable direction for them to go in#''but but but theres gay people in it'' hush. disney is not afraid of captilizing on the gay experience#also im pretty sure the gay people dont show up until like. 8 books in#thats 8 seasons#can you imagine#''guys we need to keep giving this show our support so we can eventually get solanjello (or whatever its called)''#ooooh theyre quite evil. very interesting#even tho like. dont worry you'll get your gay people eventually. you'll get all your book adaptions. you'll get all those seasons.#this franchise is disneys new pet#you can smell it#the hype. the cast announcements. the promotion#LIN MANUEL MIRANDA???#theyre going to squeeze every last drop of engagement they can get out of it

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Euphoria,' on HBO & Starring Zendya, is a Gen Z Nightmare

very happy im not a Gen-Z-er!

The teen drama has had somewhat of a recent renaissance of late, thanks to edgy shows like "Riverdale," "13 Reasons Why," "Chilling Adventures of Sabrina" and others. But HBO's new series "Euphoria," which begins Sunday, takes things to a new level; it's a provocative and explicit show that ought to cause a stir both among teens and adults. Based on the Israeli series of the same name and created for U.S. TV by Sam Levinson, "Euphoria" follows a group of high school teens in a Los Angeles suburb who are coping with the sick, sad world around them. The show mostly focuses on Rue, played by Zendaya in what may be her best and biggest role to date. Rue is returning home and integrating back into her high school and family after a stint in rehab. But she's quickly falling back into her old ways as she becomes friends with the new girl Jules (Hunter Schafer), who is trans and struggling to fit in. The show focuses on the two of them but also follows a few different cliques that orbit around each other in surprising ways. A good primer for "Euphoria" would be the divisive 2018 film "Assassination Nation," directed and written by Levinson. It is a stylish pop-art and violent revenge story that takes on some of the biggest cultural issues teens face today. It was big swing that didn't really work but it definitely garnered attention when it debuted at the Sundance Film Festival last year. With his TV show, Levinson is able to spend more time with the ideas he wanted to tackle in his movie, stretching them out and over the four episodes provided for review he takes the time to let his characters develop while dialing back some of the spastic energy that weighed down "Assassination Nation."

Though thematically similar, "Euphoria" is more of a sobering viewing experience than the cartoonish "Assassination Nation"; it is a wild ride that isn't for the faint of heart. "Euphoria" still keeps the Tumblr-aesthetic that made "Assassination Nation" stick out from a crowded festival, most notably fast cuts to jarring images that punctate characters' inner turmoil. "Euphoria" also features lots of whispery voiceover from Rue, who in the first episode, announces she was born shortly after the 9/11 attacks and the first images that were ingrained in her after being born were the Twin Towers in flames. She constantly offers this kind of insight as well as voiceover for other characters in the show. From drugs, sex, race, hookup culture, sexuality, gender identity, toxic masculinity, gender norms, the Internet and much more, there isn't a racy subject "Euphoria" won't explore. What separates the show from its contemporaries (besides its explicit scenes) is that "Euphoria" is less concerned about plot and feels more like a mood piece. The plot is in service to how the characters are feeling or what they're currently going through. Though in episodes three and four, an interesting plot does begin to take shape, involving Jules and a mystery man that she meets via a dating app. It climaxes in an incredible episode that takes place at a neon-lit carnival, echoing Alfred Hitchcock's thriller masterpiece "Strangers on a Train" (a film that's referenced a few times during "Euphoria" and sort of serves as the show's mantra.)

Fans of teen dramas may find "Euphoria" similar to the popular mid-00s U.K. series "Skins" but even that show feels tame in comparison, which results in one of the show's biggest problems. It's hard to figure out who "Euphoria," HBO's first teen show, is actually for. The show is too racy for Gen Z kids (although, who is really going to stop them from watching; thanks to the internet, they've likely been exposed to a lot worse) and too foreign for most adults (as a 31-year-old man, I have no idea what L.A. teens are actually like). "Euphoria" feels like a candy-color fever dream that's simultaneously elusive and gripping. It'll take a while to tune into the show's frequency but each episode is better than the last; the back-half of this drama ought to be fascinating. "Euphoria," which is a production of the super-chic indie company A24, comes to HBO at an interesting time. The network, facing the upcoming battle of the streaming wars, is expanding. For decades it owned Sunday nights — the only night of the week when HBO aired original programs. That's changing as the network is sprawling out to dominate Monday nights, too. It already had huge success with "Chernobyl," which turned out to be not only a ratings hit but one of the best reviewed TV shows of all-time. HBO knows what it's doing with "Euphoria." It knows it needs to draw in a new, younger audience — people who aren't tuning into the network for the frantic drama of "Big Little Lies" or the depressed hitman "Barry." Whether or not "Euphoria" is actually a good TV show sort of doesn't matter. With news over the show's controversy (30 penises, oh my! Laura Ingraham isn't happy!), there's a good chance "Euphoria" will be just what HBO ordered.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Where Are Our Black Boys on Young Adult Science Fiction and Fantasy Novel Covers?

Why are there no boys like me on these covers?

My seventeen-year-old brother who lives in Lagos, Nigeria, raised this question to me recently. Not in these exact words, but sufficiently close. I’d been feeding him a steady drip of young adult (YA) science fiction and fantasy (SFF) novels from as diverse a list as I could, featuring titles like Nnedi Okorafor’s Binti, Martha Wells’ Murderbot series, Roshani Chokshi’s The Star-Touched Queen and Cory Doctorow’s Little Brother. The question, at first seemed like a throwaway one, but as my head-scratching went on, I realised I did not have a clear-cut answer for it.

His question wasn’t why there were no black boys like him in the stories, because there definitely were. I guess he wanted to know, like I now do, why those boys were good enough to grace the pages inside but were somehow not good enough for the covers. And because I felt bad about the half-assed response I offered, I decided to see if I could find a better one.

So, I put out a twitter call for recommendations.

Can anyone point me to science fiction & fantasy novels with black teenage boys on the cover? Asking for my teenage brother. I know there's Tristan Strong, & books from Victor LaValle & Colson Whitehead, but I need more. Most YA I see with black boys are contemporary lit.

— Suyi on hiatus. (@IAmSuyiDavies) May 6, 2020

The responses came thick and fast, revealing a lot. I’m not sure I left with a satisfactory answer, but I sure left with a better understanding of the situation. Before I can explain that, though, we must first understand the what of the question, and why we need to be asking it in the first place.

Unpacking the Specifics

My intent is to engage with one question: How come there are few black boys on young adult science fiction and fantasy novel covers? This question has specific parameters:

black: of Black African descent to whatever degree and racially presented as such;

boys: specifically male-presenting (because this is an image afterall), separate from female-presenting folks, and separate from folks presenting as non-binary, all regardless of cisgender or transgender status;

are displayed prominently on covers: not silhouetted, not hinted at, not “they could be black if you turned the book sideways,” but undeniably front-of-cover blackity-black;

YA: books specifically written for young adults (readers aged 12-18), separate from middle-grade (readers 8-12) and adult (readers 18+);

SFF: science fiction and fantasy, but really shorthand for all speculative fiction and everything that falls under it, from horror to fabulism to alternative history;

novels: specifically one-story, book-length, words-only literature, separate from collections/anthologies or illustrated/graphic works (a novella may qualify, for instance)

I’m sure if we altered any of these criteria, we might find some respite. Contemporary YA and literary fiction with teenage protagonists, for instance, are littered with a relatively decent number of black boys on the covers (though many revolve around violence, pain and trauma). Young women across the people-of-colour spectrum are beginning to appear more often on SFF covers too (just take a look at this Goodreads list of Speculative Fiction by Authors of Color). Black boys also pop up on covers of graphic novels here and there (Miles Morales is a good example). But if we insist on these parameters, we discover something: a hole.

It is this gaping black hole (pardon the pun) that I hope to fill with some answers.

The Case for Need

Think about shopping at a bookstore. Your eyes run over a bunch of titles, and something draws you in to pick one–cover design, title, author, blurb. You’d agree that one of the biggest draws, especially for teens to whom YA SFF novels are aimed, is the character representation on the cover (if there’s one). Scholastic’s 7th Edition Kids & Family Reading Report notes that 76% of kids and teens report they’d like characters who are “similar to me,” and 95% of parents agree that these characters can help “foster the qualities they value for their children.” If the cover imagery, which is the first point of contact for this deduction, is not representative of the self, there’s an argument to be made that reader confidence in the characters’ ability to represent their interests would be significantly reduced.

The why of the question is therefore simple: when a group already underrepresented in literature and readership (read: black boys, since it’s still believed that black boys don’t read) are also visually underrepresented within their age group and preferred genre (read: YA SFF), it inadvertently sends a message to any black boy who loves to read SFF: you don’t fit here.

This is not to say that YA is not making strides to increase representation within its ranks. Publisher’s Weekly’s most recent study of the YA market notes various progressive strides, touching base with senior publishing professionals at teen imprints in major houses, who say today’s YA books “reflect a more realistic range of experiences.” Many of them credit the work of We Need Diverse Books, #DVPit, #OwnVoices and other organizations and movements as pacesetters for this growing trend.

In the same breath, though, these soundbites are cautiously optimistic, noting that the industry must look inward for underlying reasons why easy defaults remain commonplace. Lee&Low’s recent Diversity in Publishing 2019 study’s answer to why unquestioned go-tos still reign supreme is that the industry remains, sadly, 76% Caucasian. For a genre-readership with such exponential success, that makes the hole a massive one. Of the Top 10 Best Selling Books of the 21st Century, four are YA SFF franchises by Rowling, Collins, Meyer, and Roth, the most among all listed genres. In 2018’s first half, YA SFF vastly outsold every other genre, amassing over a quarter of an $80-million sales total. This doesn’t even include TV and film rights.

I once was a black boy (in some ways, I still am). If such a ubiquitous, desired, popular (and don’t forget, profitable) genre-readership somehow concluded a face like mine on its covers was a no-go, I’d want to know why too.

Navigating the Labyrinth

Most of the responses I received fell into three categories: hits & misses, rationale, and outlook. Hits & misses were those who attempted to recommend books that met the criteria. If I had to put a number to it, I’d say there were around 10+ misses to one hit. I received many recommendations that didn’t fit: middle-grade novels, graphic novels, covers where the blackness of the boy was up for debate, novels featuring black boys who were not present on the cover, etc.

The hits were really great to see, though. Opposite of Always by Justin A. Reynolds was the crowd favourite of the recent recommended titles. The Coyote Kings of the Space-Age Bachelor Pad by Minister Faust was the oldest recommended title (2004). One non-English title on offer was Babel Corp, Tome 01: Genesis 11 by Scott Reintgen (translated to French by Guillaume Fournier, published in the US as Nyxia). Non-print titles also showed up, like Wally Roux, Quantum Mechanic by Nick Carr (audio only). Lastly, some crossover titles like Miles Morales: Spider-Man by Jason Reynolds (MG/YA) and Temper by Nicky Drayden (YA/Adult) were present. You’ll find a full list of all recommendations at the end of this article.

Many of the hits were worrisome for other reasons, though. For instance, a good number are published under smaller presses, or self-published. Most are of limited availability. Put simply: a high percentage of all books recommended have severely limited wider industry coverage, which twanged a sour note in this orchestra.

The rationale group attempted to approach the matter from a factual angle. Points were made, for instance, that fewer men and nonbinary folks are published in YA SFF than women, and fewer black men even so, therefore representing black boys on covers may increase with more black male authors of YA SFF. While a noble thought, I do argue that various YA authors, regardless of race or gender, have written black boys as protagonists, yet those didn’t make the covers anyway. Would more black male authors suddenly change that?

Another rationale pointed toward YA marketing, which many stated mostly targets teenage girls because they are the biggest audience. I’m not sure how accurate this is, but I know sales often tell a different story from marketing (case in point: 2018 market estimates show that nearly 70% of all YA titles are purchased by adults aged 18-64, not teenage girls). If the sales tell a different story, yet marketing strategies insist upon a one-note approach, then it’s not really about the sales, is it?

Lastly, the outlook responses came mostly from readers, authors and publishing professionals who are long-time advocates of increased inclusion in publishing. The overwhelming consensus was that, while there is no complete absence of black boys on YA SFF covers, the real problem is the difficulty in pointing them out. It was agreed that it speaks volumes that we have to do this deep-dive just to find an okay amount of recommendations. Many left with a feel-good note, though, since more authors and professionals dedicated to inclusion and visibility are finally getting their feet into the doors at Big Publishing. Thanks to advocates like People of Color in Publishing and We Need Diverse Books, the future looks exciting.

So, I’ll end this on another feel-good note by offering an ongoing list of recommendations that fit the bill. You’ll find that most are absolutely worth a look-see. This list is also open for public updates, so feel free to add your own recommendations. And here’s looking to the decision-makers at Big Publishing to make this list even bigger.

+Black Boys on YA SFF Novel Covers: A List of Recommendations

#books#black literature#black lit#black children's books#children's books#black children#black boys#people of color in publishing#we need diverse books#tor#ya#sff#representation#publishing

0 notes

Text

Best books of 2017

The top 10

1. The Idiot (2017) by Elif Batuman There was never going to be any other contender for my #1 favourite. The Idiot isn't just one of the best books of the year, it's one of the best books of my life, an unforgettable, transformative novel. Only a few books make such an indelible impression that they come to feel like part of your identity, and The Idiot is one of these rare finds. The Idiot weaves an idiosyncratic and charming plot around Selin, a fish out of water in her first year at Harvard, a young woman of enormous intelligence struggling to untangle the mysterious codes of behaviour that seem to come naturally to everyone else around her. (Her deadpan observations are often utterly hilarious, and although it is also heartbreaking, I don't think any book has made me laugh this much in years.) Many of her choices are almost random, since she has little idea which path to take. Central to Selin's development throughout the book is her close, tense, peculiar friendship with Ivan, a slightly older maths student. She becomes infatuated: her decision to spend the summer teaching English in Hungary, his home country, is a result of that. I loved Selin so much that, by the time I reached the end of the book, I felt like I was being wrenched away from a real friend. She is so palpable, so true-to-life – the perfect mix of naive and sarcastic, rebel and conformist, book-smart and ignorant. The Idiot is the sort of book I want to recommend with real passion and precision; not by shouting about it to anyone who'll listen, but by seeking out those I know will appreciate it and ardently pressing it upon them. So good I could WEEP.

2. Based on a True Story (2017) by Delphine de Vigan, trans. George Miller Leave it to a French author to turn what sounds like the formula for a standard psychological thriller into a kaleidoscopic, existential meditation on writing, identity and friendship. Continually inviting speculation as to how much of it is autobiographical, Based on a True Story follows an author, Delphine, who has recently written an unexpectedly successful novel and is unsure what to do next. When she meets the glamorous L. at a party, she seems to have found the perfect confidante. But L.'s influence grows more and more toxic, and Delphine begins to lose her hold on her own identity. The story is sinister and edge-of-your-seat gripping, yet fiercely intelligent and philosophical: an utterly fascinating maze of fact, fiction and perception. 3. Devil's Day (2017) by Andrew Michael Hurley John Pentecost returns to his family home, a farm in a tiny and decidedly old-fashioned rural community, after the death of his grandfather. As Devil's Day – an eccentric village holiday linked to local legend – grows closer, old rivalries are resurrected and secrets come spilling out. Incredibly vibrant and masterfully paced, this is a bucolic tale of family and nature, death and renewal, history and folklore, and what lurks beneath the surface; it only gestures towards the macabre, and is all the more unnerving for it. It's like Robert Aickman rewrote a Thomas Hardy novel. While Hurley's debut The Loney was effective, I thought this was ten times better. 4. Harriet Said... (1972) by Beryl Bainbridge Despite the pervasiveness of coming-of-age themes in adult fiction, it's rare to come across a writer who is able to truly capture the strange contradictions of adolescence. In Harriet Said..., Beryl Bainbridge gets it exactly right and it is terrifying. This is a remarkable, nuanced character portrait of two precocious girls at the younger end of their teens: the unnamed narrator and her manipulative friend Harriet. Over the course of a claustrophobic summer, the narrator grows dangerously close to a much older man. It's a powerful and beautifully written story that drips with unease, feels horribly real, and is perhaps even more disturbing today than when it was published.

5. I'm Thinking of Ending Things (2016) by Iain Reid This year I read a handful of books that resembled nightmares in both construction and imagery. This was the best, the most effective, and the most memorable. A young couple are on a long, lonely drive, with one – the narrator – wondering whether she should end the relationship (hence the title). What unfolds from there is probably best described as 'psychological horror', replete with uncanny details. It steadily ramps up the disquiet, constantly veering off-course so you're left disorientated, asking yourself what the hell you're reading (in a good way). A masterclass of suspense and restrained weirdness. 6. Children of the New World: Stories (2016) by Alexander Weinstein In these tales of our incipient future, virtual lives are ubiquitous and the real world is rapidly deteriorating. However, it's the human element that makes these stories so successful and emotionally affecting. The sharply observed details, the rich characters, the imaginative visions of a world to come: everything about it is brilliant, my list of favourite stories is practically the entire book, and there's barely a flaw to be picked at. The best short story collection I've read in years and the definition of 'all killer, no filler'. 7. Kill All Normies: Online Culture Wars from 4chan and Tumblr to Trump and the Alt-Right (2017) by Angela Nagle The best political book I have read in aeons, maybe ever. In an accessible but unpatronising study, Angela Nagle draws a line through history from the 'culture wars' of the 1960s to those of today, and undertakes a review of the many, many factions of what is often sweepingly referred to as the alt-right. She writes even-handedly and with a fair critical eye about recent iterations of disruptive political groupings on both the right and left, achieving a perfect balance between academic critique, political commentary and assured, intelligent, non-embarrassing writing about the internet and its unique subcultures. In a year of political turmoil, Nagle's voice felt not just refreshing but essential.

8. The Answers (2017) by Catherine Lacey Broke, sick and out of options, Mary replies to a mysterious ad promising an 'income-generating experience'. This turns out to be a role as one of a series of Girlfriends to an A-list celebrity who thinks he can solve the 'problem' of romantic love by deconstructing and segregating its elements. Lacey writes Mary brilliantly, teasing out unique insights, naive and profound at the same time, about love and relationships. Her observations are so clean and sharp, her voice in a class of its own. I loved absolutely everything about the way this unusual, wonderful book was written – it's magical. 9. A Natural (2017) by Ross Raisin There were other books I rated higher this year, but few have stuck with me quite as vividly as A Natural. Tom is a talented young footballer whose promised success has failed to materialise; instead, he ends up playing for a middling League Two team. Introverted and sensitive, Tom doesn't feel he fits in, and that only gets worse when he embarks on a new relationship. It's a tender, honest novel exploring sexuality, repression and self-hatred. It's painful and precise on growing up and what 'success' looks like. I see it as a feminist novel about masculinity, looking at how patriarchal norms fail men who don't conform. 10. The Furnished Room (1961) by Laura Del-Rivo Published in 1961 and a bestseller in its day, this remarkable thriller seems to have (very unfairly) slipped into relative obscurity. Like the lost halfway point between Crime and Punishment and American Psycho, it charts the mindscape of a nihilist, chauvinist clerk, Joe Beckett, through his life of numbing excess in the bedsits, offices and cafés of 1960s London. When an insalubrious acquaintance asks him to murder his ailing aunt, Joe approaches it – in typically cold fashion – as an interesting moral dilemma, but things inevitably spiral out of control.

Honourable mentions

Books published in 2017

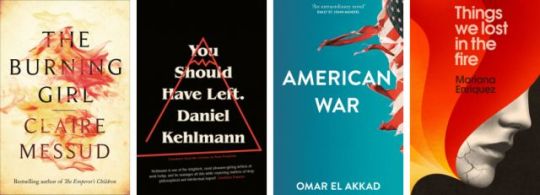

The Burning Girl by Claire Messud The title is apt: Messud takes a tired premise – two teenage girls growing up and growing apart – and sets it ablaze with knockout writing. Incandescent, razor-sharp, breathtakingly confident.

You Should Have Left by Daniel Kehlmann, trans. Ross Benjamin Brilliant modern take on the haunted house – like Mark Z. Danielewski's House of Leaves if it'd been ruthlessly edited down to only its most authentic and menacing elements.

This Young Monster by Charlie Fox Sublime collection of feverish, phantasmagorical essays that pull apart the distinctions between fiction, fact and surrealism, exploring the intersections of pop culture, queerness and self-image.

The Party by Elizabeth Day An irresistible formula (unreliable outcast narrator enters into golden world of privilege) executed flawlessly. My pick of the year for sheer unadulterated enjoyment.

American War by Omar El Akkad An extraordinarily rich dystopian vision in which a future USA is riven by civil war. Absorbing, emotionally wrenching, and complete with a brilliant heroine in the shape of rebel fighter Sarat Chestnut.

Things We Lost in the Fire by Mariana Enríquez, trans. Megan McDowell Not so much horror stories as stories about a country (Argentina) haunted and menaced by history. Powerful, memorable and wonderfully bizarre.

How to Be Human by Paula Cocozza After her abusive partner leaves, Mary becomes obsessed with a wild fox and begins to lose her grip on reality. Hands down one of the strangest, most audacious and uncomfortable stories I've read; it will leave you queasily transfixed.

Ties by Domenico Starnone, trans. Jhumpa Lahiri A portrait of a disintegrating marriage structured like a dossier of evidence, analysing the perspectives of wife, husband and daughter. Packed with emotion, yet elegant in its approach to the damage wrought by destructive behaviour.

Sweetpea by CJ Skuse If you've ever wondered what American Psycho reimagined as chick-lit would be like (and I mean, who hasn't?), this is it. Very bloody, very funny.

Books published before 2017

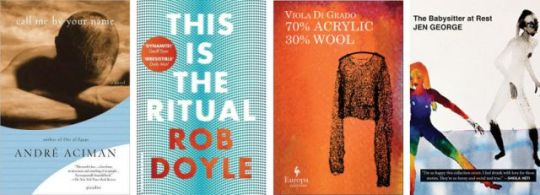

Call Me by Your Name (2007) by André Aciman You're probably familiar with the film; the book it's based on is more than worth your time, too. A heady evocation of first lust that brings its Mediterranean setting vividly to life, it's agonising as often as it's sexy.

This is the Ritual (2016) by Rob Doyle Lacerating short stories that approach (and rip apart) the trope of the tortured artist from a working-class perspective.

Two Girls, Fat and Thin (1991) by Mary Gaitskill Chronicles the friendship between two very different – but equally idiosyncratic – women, and traces their tortured histories. Startling and insightful, with unforgettable characters.

70% Acrylic 30% Wool (2013) by Viola Di Grado, trans. Michael Reynolds An Italian girl living in England deals with terrible grief, unrequited love and the mysteries of communication. Funny and twisted and dark, furious and bittersweet and raw.

FantasticLand (2016) by Mike Bockoven An oral history of the bloody disaster that unfolded after a hurricane left a few hundred employees of a theme park cut off from civilisation. Unbelievably fun horror with great worldbuilding.

The Absolution of Roberto Acestes Laing (2014) by Nicholas Rombes A curious and remarkable book which somehow makes descriptions of imagined films mesmerising. Dreamlike and disquieting.

The Babysitter at Rest (2016) by Jen George In these surreal-yet-mundane stories, George plays with her characters like they're figures in a very peculiar dolls' house. She's amazing at combining the painfully real with humour and fantasy.

Coming up in 2018

The Earlie King & the Kid in Yellow by Danny Denton You're probably already familiar with how much I loved this, so I won't go on about it, except to say again that it is a breathtaking patchwork of genres, a triumph of wordplay and a total joy to read. (If it wasn't a 2018 title, it would be in my top 10.)

A few more for the road

Life and all its ugliness, glory, grief, joy and horror: The Future Won't Be Long by Jarett Kobek; Sorry to Disrupt the Peace by Patty Yumi Cottrell; The Animators by Kayla Rae Whittaker; All Grown Up by Jami Attenberg; Wolf in White Van by John Darnielle Dark futures, the terrifying possibilities of technology, and what comes after its collapse: UnAmerican Activities by James Miller; Broadcast by Liam Brown; No Dominion by Louise Welsh; The Possessions by Sara Flannery Murphy Creepy shit (need I say more): The White Road by Sarah Lotz; The Wrong Train by Jeremy de Quidt; The Silent Companions by Laura Purcell; The Lost Village by Neil Spring; The Coffin Path by Katherine Clements When you just need to get stuck in to an engrossing thriller: He Said/She Said by Erin Kelly; Bonfire by Krysten Ritter; If We Were Villains by M.L. Rio; Last Seen by Lucy Clarke

0 notes