#henry ireton

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#OTD in 1650 – Kilkenny surrendered to Oliver Cromwell.

The success of Oliver Cromwell’s Irish campaign during the autumn of 1649 caused further divisions in the Marquis of Ormond’s Royalist-Confederate coalition. With the defeat of British and Scottish forces in Ulster and the defection of most of Lord Inchiquin’s Protestant troops to the Parliamentarians, Ormond was obliged to rely increasingly upon Catholic support. Early in December 1649, the…

View On WordPress

#Co. Kilkenny#Henry Ireton#Ireland#Irish Town#James Butler#Kilkenny Castle#Marquis of Ormond#Oliver Cromwell#Oliver Cromwell&039;s Model Army#River Nore#Siege of Drogheda#St John&039;s Bridge#Surrender of Kilkenny

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finally finished watching Cromwell (1970) yesterday. Out of all Michael Jayston films (current obsession still going strong!) I have been wanting to watch this the most because the English Civil War is a subject in which I am quite interested. Even then, going in, I prepared myself for historical inaccuracies and departures from my understanding of certain events and personalities because that's just what you do when you watch a historical film.

First thing to note is that the film has many good points. For its time, the film looked marvellous. I love the battle scenes and those scenes set in the House of Commons and the royal court – simply beautiful sets. Charles I's entrance into the Commons is my favourite; his flamboyantly colourful clothes set against a sea of MPs in black, providing a powerful contrast between royal decadence and somber Parliamentary sensibilities.

There's also a lot to admire in the acting. Alec Guinness is exquisite as Charles I and the character was played largely in line with my impressions of the doomed king: a sympathetic personal side (his reunion with his family after the war reportedly even moved Cromwell to tears) but a truly awful and weak ruler who didn't hesitate to drop even his most loyal supporters, as convincingly conveyed in the scene where Charles unfairly dismissed Prince Rupert after the Bristol surrender ("You promised mountains and yet performed molehills!"). Masterful performance.

Other supporting performances were strong too. I thought Dalton's Prince Rupert worked, despite the character being so different (read: less flamboyant) in my mind. Jayston's Ireton and Thomas Fairfax (not familiar with the actor, sorry) are even more different than what I imagined. I wasn't sure how I feel about the characterisation of Ireton and Fairfax. Seeing as I know Ireton primarily for the Heads of Proposals (probably the most famous document of that period, certainly influential in the Putney Debates, so there's really no escaping it) the differences stand out a bit. And no mention at all that he's Cromwell's son-in-law. Weird choice since that could have supported the storyline of Ireton being a strong influence on Cromwell, but on the whole I think that didn't take away from the story.

All this would have made the film an acceptable one save for one very key thing. I really couldn't stand Richard Harris's take on Cromwell. I know many biogs (even the ones that are sympathetic, like Antonia Fraser's Our Chief of Men) make allusion to Cromwell's 'changeable moods' but I don't think what Harris did captured what it means. Cromwell was most likely having nervous breakdowns (melancholia was the term used at the time by his physician) at certain periods of time, usually when he was faced with big decisions to make. What Harris did however was something else.

As I said, I don't mind occasional departures from history especially if they serve the film but here they did not. History aside, Harris made Cromwell changeable in a matter of seconds which backfired spectacularly considering that Cromwell is still one of the most divisive figures in English history. A careful balance must be struck between his nervous personality and his well-documented charisma and charm that helped him win supporters. There was no suggestion of the latter in the film. Even and calm tone of voice one second and suddenly booming rage in the next, shouting at everyone around him, even politicians who were on his side. Hard to see why anyone would see a leader in this unpredictable man sorely lacking in charisma. The personal side was more successfully portrayed –in scenes with his wife and when he received news of his son's death – although not enough to make up for the dismal attempt at capturing Cromwell the politician.

Aside from the lack of charisma, film Cromwell wasn't even portrayed as a visionary. It's like all ideas and plans he had for a better England seemingly originated from or were suggested to him by others around him chiefly Ireton. So, no charisma, no vision. Bad combo especially when stood next to Guinness' Charles I.

As the film is titled 'Cromwell', its success would largely depend on whether the character is convincingly played. I don't think it was. The film would have me believe that Cromwell's authority comes solely from his booming voice, as if sound volume was the only thing that matters in leadership. That's mainly why, despite all the good things that recommend this film and despite my willingness to forgive historical inaccuracy, I couldn't really enjoy it.

#cromwell 1970#oliver cromwell#charles i#richard harris#alec guinness#michael jayston#henry ireton#sir thomas fairfax#historical film

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Trial of the King, January 1649: ‘I tell you we will cut off his head with the crown on it,’

Revolution and Regicide

Judgement of Charles I by Ladislaus Bakalowicz (c1860)

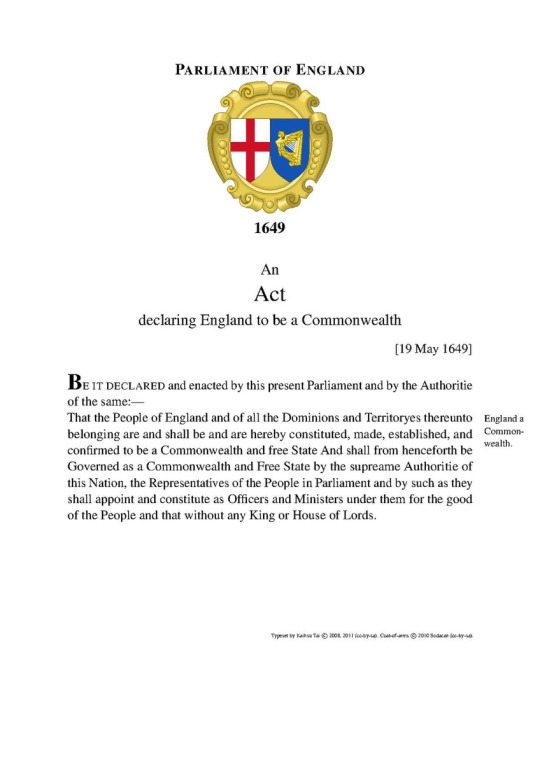

EVENTS MOVED swiftly in the January of 1649. The ordnance appointing the High Court of Justice moved rapidly to the House of Lords where it was promptly rejected with many peers doubting the judicial or constitutional grounds on which Parliament could place the monarch on trial for treason. The Earl of Northumberland highlighted the difficulty in establishing which party had first declared war on the other, given the almost accidental commencement of armed conflict in 1642. Indeed, this lack of clarity as to the authority of the High Court of Justice to bring the King to trial at all dogged the proceedings throughout and questioned the legitimacy of its ultimate ruling. The Commons however were in no mood to brook dissent: claiming that ‘the Commons in Parliament assembled, hath the force of law,’ it rejected the Lords’ arguments and swiftly passed the ordinance into law on 6th January. The Rump then appointed 135 commissioners to act as judge and jury, although only sixty eight so appointed actually took up the role. The Grandees were also disunited. Thomas Fairfax was appalled by the whole business and publicly distanced himself from the trial, whereas Henry Ireton and Oliver Cromwell remained in the capital, symbolic support to the revolutionary enterprise.

The Lord President, effectively both prosecuting counsel and senior judge, was John Bradshaw, a republican barrister from Stockport who had not seen action in the wars, but was nonetheless convinced of the righteousness of the Parliamentary cause under God, and of the need to bring an end to the monarchy that had, in his view, brought England to the brink of ruin. Charles was brought from St James’ Palace to the Westminster Hall on 20th January. The King dressed in black for the occasion, including a cloak that clearly displayed the badge of the Order of the Star and Garter. He looked regal indeed, causing a last minute drop in confidence on the part of the commissioners and Cromwell himself, witnessing Charles’ arrival. When Cromwell urged the commissioners to be clear on the authority they held to try the King, they agreed that the Commons of England gave them authority enough: no other argument was ever made.

Westminster was fashioned into the appearance of a court house, with a stage erected to seat Bradshaw and his fellow judges, a table for clerks to record the proceedings, and a seat for the King, who kept his hat on his head throughout the trial, to face his inquisitors. John Cook, one of the prosecuting barristers, read the charge, that by pursuing war with his Parliament, Charles had sought to rule as an absolute monarch and was therefore condemned as ‘a tyrant, traitor, murderer, and a public and implacable enemy of the Commonwealth of England’. Charles laughed out loud at this and asked the question the commissioners had dreaded - by what authority did this court seek to put on trial their lawful king? Throughout the proceedings Charles continued to needle his prosecutors with this demand and never received a clear or satisfactory answer. For the next three days the trial continued in this vein. The King refused to enter a plea because to do so would be to confer legitimacy on the court and therefore to collude in their right to condemn him; Bradshaw flailed when faced by the King’s demands for precedent or sources of constitutional authority. His counters focused on Charles’ behaviour and the previous removal of unworthy monarchs in medieval times. All present knew this argument was weak: the usurpations associated with, for instance, the Wars of the Roses, were essentially coups within the ruling royal family. On no previous occasion had a rival source of authority to royal power sought the removal of a monarch.

The impasse remained unresolved. With Charles refusing not only to enter a plea, but also claiming that he represented the true liberties of England, a frustrated Bradshaw ordered the clerks to enter a plea of guilty on the King’s behalf. Witnesses, who could not be heard in court due to Charles’ refusal to plead, were therefore interviewed by a sub-committee of the court and their testimony accepted. The court was adjourned on 27th January and the commissioners retired to deliberate. There was much disquiet in the Kingdoms at the way events had transpired. Even the Parliamentary-loyalist Londoners were outraged to the extent Bradshaw himself feared to walk abroad without a guard of soldiers; the Scottish government denounced the trial of a Stuart King and the commander of the Army himself, Fairfax, was known to be deeply troubled. The job of Cromwell, Bradshaw and Ireton was therefore, in this febrile atmosphere, to impress on any wavering commissioners that they must finish what they had started.

So it was that on 28th January 1649 the sentence of death was passed by the court. The death warrant was signed by Bradshaw, Cromwell, Ireton and Colonel Thomas Pride, and just 59 of the commissioners. The show trial thus ended with a mockery of Parliamentary representation sealing the fate of Charles. One wonders what John Pym would have made of it all.

Charles was brought back to court the following day to receive the judgement. He made a last ditch plea to have his case heard before Commons and Lords and despite some sympathy amongst some of the commissioners to this request, Cromwell’s will prevailed and Charles was hustled away and back to St James’ Palace. He spent his last forty eight hours receiving spiritual sustenance from his personal chaplain, donating his personal effects and saying farewell to his distressed and terrified children, Princess Elizabeth and Prince Henry. On 30th January, the King was escorted under armed guard to the hastily constructed scaffold outside Indigo Jones’ Banqueting Hall in Whitehall. Soldiers kept a disbelieving crowd at bay as the monarch mounted the scaffold. He took prayers with his chaplain and made an unrepentant speech (characterised by the phrase ‘a subject and a sovereign are clean different things’) and finally lay face down to receive the death stroke. The executioner took just one efficient blow with the axe to sever Charles’ head from his body. When the head was shown to the watching Londoners in customary fashion, the crowd, according to witnesses present, let out an audible moan.

For the first time since the two realms came into being, England and Scotland were Kingdoms without a King.

#english civil war#charles i of england#thomas fairfax#henry ireton#oliver cromwell#execution of Charles I#John bradshaw

1 note

·

View note

Text

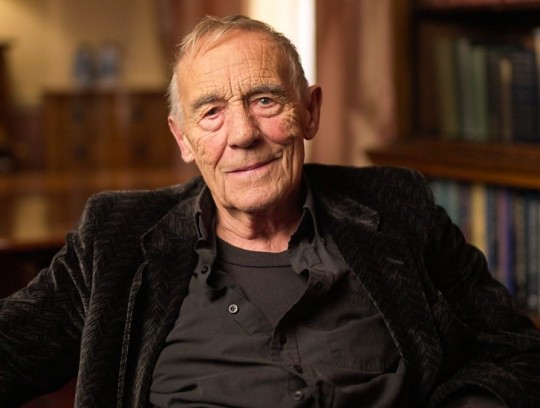

The actor Michael Jayston, who has died aged 88, was a distinguished performer on stage and screen. The roles that made his name were as the doomed Tsar Nicholas II of Russia in Franklin Schaffner’s sumptuous account of the last days of the Romanovs in Nicholas and Alexandra (1971), and as Alec Guinness’s intelligence minder in John Le Carré’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy on television in 1979. He never made a song and dance about himself and perhaps as a consequence was not launched in Hollywood, as were many of his contemporaries.

Before these two parts, he had already played a key role in The Power Game on television and Henry Ireton, Cromwell’s son-in-law, in Ken Hughes’s fine Cromwell (1969), with Richard Harris in the title role and Guinness as King Charles I. And this followed five years with the Royal Shakespeare Company including a trip to Broadway in Harold Pinter’s The Homecoming, in which he replaced Michael Bryant as Teddy, the brother who returns to the US and leaves his wife in London to “take care of” his father and siblings.

Jayston, who was not flamboyantly good-looking but clearly and solidly attractive, with a steely, no-nonsense, demeanour and a steady, piercing gaze, could “do” the Pinter menace as well as anyone, and that cast – who also made the 1973 movie directed by Peter Hall – included Pinter’s then wife, Vivien Merchant, as well as Paul Rogers and Ian Holm.

Jayston had found a replacement family in the theatre. Born Michael James in Nottingham, he was the only child of Myfanwy (nee Llewelyn) and Vincent; his father died of pneumonia, following a serious accident on the rugby field, when Michael was one, and his mother died when he was a barely a teenager. He was then brought up by his grandmother and an uncle, and found himself involved in amateur theatre while doing national service in the army; he directed a production of The Happiest Days of Your Life.

He continued in amateur theatre while working for two years as a trainee accountant for the National Coal Board and in Nottingham fish market, before winning a scholarship, aged 23, to the Guildhall School of Music and Drama in London, where he was five years older than everyone else on his course. He played in rep in Bangor, Northern Ireland, and at the Salisbury Playhouse before joining the Bristol Old Vic for two seasons in 1963.

At the RSC from 1965, he enjoyed good roles – Oswald in Ghosts, Bertram in All’s Well That Ends Well, Laertes to David Warner’s Hamlet – and was Demetrius in Hall’s film of A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1968), with Warner as Lysander in a romantic foursome with Diana Rigg and Helen Mirren.

But his RSC associate status did not translate itself into the stardom of, say, Alan Howard, Warner, Judi Dench, Ian Richardson and others at the time. He was never fazed or underrated in this company, but his career proceeded in a somewhat nebulous fashion, and Nicholas and Alexandra, for all its success and ballyhoo, did not bring him offers from the US.

Instead, he played Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (Lewis Carroll) in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1972), a so-so British musical film version with music and lyrics by John Barry and Don Black, with Michael Crawford as the White Rabbit and Peter Sellers the March Hare. In 1979 he was a colonel in Zulu Dawn, a historically explanatory prequel to the earlier smash hit Zulu.

As an actor he seemed not to be a glory-hunter. Instead, in the 1980s, he turned in stylish and well-received leading performances in Noël Coward’s Private Lives, at the Duchess, opposite Maria Aitken (1980); as Captain von Trapp in the first major London revival of The Sound of Music at the Apollo Victoria in 1981, opposite Petula Clark; and, best of all, as Mirabell, often a thankless role, in William Gaskill’s superb 1984 revival, at Chichester and the Haymarket, of The Way of the World, by William Congreve, opposite Maggie Smith as Millamant.

Nor was he averse to taking over the leading roles in plays such as Peter Shaffer’s Equus (1973) or Brian Friel’s Dancing at Lughnasa (1992), roles first occupied in London by Alec McCowen. He rejoined the National Theatre – he had been Gratiano with Laurence Olivier and Joan Plowright in The Merchant of Venice directed by Jonathan Miller in 1974 – to play a delightful Home Counties Ratty in the return of Alan Bennett’s blissful, Edwardian The Wind in the Willows in 1994.

On television, he was a favourite side-kick of David Jason in 13 episodes of David Nobbs’s A Bit of a Do (1989) – as the solicitor Neville Badger in a series of social functions and parties across West Yorkshire – and in four episodes of The Darling Buds of May (1992) as Ernest Bristow, the brewery owner. He appeared again with Jason in a 1996 episode of Only Fools and Horses.

He figured for the first time on fan sites when he appeared in the 1986 Doctor Who season The Trial of a Time Lord as Valeyard, the prosecuting counsel. In the new millennium he passed through both EastEnders and Coronation Street before bolstering the most lurid storyline of all in Emmerdale (2007-08): he was Donald de Souza, an unpleasant old cove who fell out with his family and invited his disaffected wife to push him off a cliff on the moors in his wheelchair, but died later of a heart attack.

By now living on the south coast, Jayston gravitated easily towards Chichester as a crusty old colonel – married to Wendy Craig – in Coward’s engaging early play Easy Virtue, in 1999, and, three years later, in 2002, as a hectored husband, called Hector, to Patricia Routledge’s dotty duchess in Timberlake Wertenbaker’s translation of Jean Anouilh’s Léocadia under the title Wild Orchids.

And then, in 2007, he exuded a tough spirituality as a confessor to David Suchet’s pragmatic pope-maker in The Last Confession, an old-fashioned but gripping Vatican thriller of financial and political finagling told in flashback. Roger Crane’s play transferred from Chichester to the Haymarket and toured abroad with a fine panoply of senior British actors, Jayston included.

After another collaboration with Jason, and Warner, in the television movie Albert’s Memorial (2009), a touching tale of old war-time buddies making sure one of them is buried on the German soil where first they met, and a theatre tour in Ronald Harwood’s musicians-in-retirement Quartet in 2010 with Susannah York, Gwen Taylor and Timothy West, he made occasional television appearances in Midsomer Murders, Doctors and Casualty. Last year he provided an introduction to a re-run of Tinker Tailor on BBC Four. He seemed always to be busy, available for all seasons.

As a keen cricketer (he also played darts and chess), Jayston was a member of the MCC and the Lord’s Taverners. After moving to Brighton, he became a member of Sussex county cricket club and played for Rottingdean, where he was also president.

His first two marriages – to the actor Lynn Farleigh in 1965 and the glass engraver Heather Sneddon in 1970 – ended in divorce. From his second marriage he had two sons, Tom and Ben, and a daughter, Li-an. In 1979 he married Ann Smithson, a nurse, and they had a son, Richard, and daughter, Katie.

🔔 Michael Jayston (Michael James), actor, born 29 October 1935; died 5 February 2024

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

On 20th January 1649 Charles I went on trial for treason and other “high crimes”

The trial of Charles I was one of the most momentous events ever to have taken place in the entire British Isles, . Kings have been deposed and murdered, but never before had one been tried and condemned to death whilst still King.

Following the end of the Civil War Charles I was brought to trial in Westminster Hall on this day, 1649. The Serjeant at Arms rode into the Hall carrying the mace and accompanied by six trumpeters on horseback. The King’s trial was proclaimed to the sound of trumpets and drums, at the south end of the Hall.

Bringing the King through a large crowd at the north was too great a risk; on the other hand, it was important that the trial be held in public. The court was divided from the public by a wood partition from wall to wall, backed by railings, and guards were stationed on the leads.

Charles appeared before his judges four times, charged with tyranny and treason. The exchanges always took a similar form with the King challenging the court’s authority and its right to try him. Charles also believed that he had the sole right to make laws, so to oppose him was a sin against God.

If you remember from previous posts about the Stewart monarchs, they believed in the divine right of kings, or divine-right theory of kingship, a political and religious doctrine of royal and political legitimacy. It asserts that a monarch is subject to no earthly authority, deriving his right to rule directly from the will of God.

The King’s persistence disconcerted the judges, but there was little doubt about the outcome, and the death sentence was proclaimed on 27th January, it was carried out 3 days later and England became a Republic

The Covenanter Parliament of Scotland meanwhile proclaimed Charles II King of “King of Great Britain, France and Ireland” But being Scotland things weren’t that simple, they refused to allow their new monarch into the country until he accepted the imposition of Presbyterianism throughout Britain and Ireland.

It took time for them to negotiate an agreement and left with little option, he agreed the demands of the Scottish Covenanters and came ashore at at Garmouth, in Moray, on 23 June 1650, signing the Covenant as he came ashore. Cromwell in response invaded Scotland and the King fled to France. It wasn’t until Cromwell’s death that the English invited him to become King, after the restoration many of the surviving regicides were tried and ten were condemned and executed.

The bodies of the key men who ordered the execution of Charles I - Oliver Cromwell, John Bradshaw and Henry Ireton - were exhumed and their heads stuck on poles on one of Westminster Hall’s towers. Cromwell’s remained there for more than 20 years!

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Clash at Naseby

The battle of Naseby was a decisive battle during the war and was the battle that show the effectiveness of the parliamentary New Model Army. However, my drawing isn't depicting that, but the clash at the parliamentary right between the Ironsides led by Oliver Cromwell and the royalist cavalry. The Ironsides managed to break the royalists cavalry and then charge the rear of the royalist infantry, wining the battle. As an interesting fact, the left led by Henry Ireton didn't have a lot of luck and were put to rout by Prince Rupert's cavalry, but the latter decided to plunder the parliamentarian baggage train instead of attacking the infantry. At the time they returned to the battlefield, Charles I had ordered the retreat.

If you have trouble in telling who is who, just remember that the parliamentarians used orange sashes and the royalists red ones. And yes, I copied the Ironside with the pistol from an illustration made by Graham Turner. I needed a guy there and didn't knew what to do...

#armor#art#war#civil war#english civil war#english#england#parliament#17th century#cavalry#clash#history#historical art#history art

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

IMAGENES Y DATOS INTERESANTES DEL DIA 30 DE ENERO DE 2024

Día Escolar de la No Violencia y la Paz, Día Mundial de la Enfermedades Tropicales Desatendidas (ETD), Día Internacional del Croissant, Día Internacional del Técnico Electrónico, Año Internacional de los Camélidos.

Santa Batilde, San Barsen, Santa Jacinta y Santa Martina.

Tal día como hoy en el año 2020

Hoy, después de que se produjeran los primeros contagios fuera de China, la Organización Mundial de la Salud declara la alerta internacional ante la imparable expansión del coronavirus de Wuhan (covid-19), a pesar de la excelente reacción de las autoridades chinas. (Hace 4 años)

2012

En Siria mueren más de un centenar de personas, incluyendo 55 civiles, en lo que parece ser una imparable guerra civil a consecuencia de la rebelión que enfrenta a las tropas de Bachar El Asad y a opositores y soldados desertores. (Hace 12 años)

1972

En Londonderry, Irlanda del Norte, tiene lugar lo que se conocerá como "Domingo Sangriento" al abrir fuego soldados del Primer Regimiento de Paracaidistas del Ejército británico contra una manifestación de aproximadamente 15.000 irlandeses que protestan por la imposición, seis meses antes, de las leyes de emergencia que permitieron encarcelar a 900 nacionalistas sin proceso legal previo. Mueren 14 manifestantes. De este modo se recrudece el conflicto entre católicos y protestantes. (Hace 52 años)

1933

El anciano presidente alemán Paul Hindenburg accede a nombrar a Adolf Hitler como canciller, a pesar de despreciarle. (Hace 91 años)

1847

En Estados Unidos, tras haberse fundado la localidad a finales del siglo XVIII con el nombre de Yerba Buena, esta población es rebautizada hoy con el nombre de "San Francisco", poco después de que la fuerza naval estadounidense al mando del Comandante John Sloat, reclame el territorio para su país. (Hace 177 años)

1667

Se firma la Paz de Andrusovo que pone fin a la Guerra de los Trece Años entre Rusia y Polonia. Se acuerda la soberanía rusa de la Ucrania del Margen izquierdo, mientras que la Ucrania del Margen derecho y Bielorrusia permanecerán bajo control polaco. (Hace 357 años)

1661

En Inglaterra, tras restituirse el 29 de mayo de 1660 a Carlos II en el trono y decretar éste una amnistía para los seguidores de Cromwell mediante el Acta de Inmunidad y Olvido, no perdonará a los jueces ni autoridades involucrados en el juicio y ejecución de su padre, algunos de los cuales fueron ejecutados en 1660 y otros condenados a cadena perpetua. Asimismo ordena someter a los cadáveres de Henry Ireton, John Bradshaw y Oliver Cromwell a la indignidad de una ejecución póstuma. Por eso en este día, la misma fecha en que había sido ejecutado su padre Carlos I de Inglaterra doce años atrás, el cuerpo de Oliver Cromwell es exhumado de su tumba en la Abadía de Westminster, y sometido al ritual de la ejecución póstuma, siendo colgado sus restos de cadenas en la plaza de Tyburn durante unos días, para ser después decapitado y lanzado a una fosa, mientras que su cabeza pasará a ser exhibida en lo alto de un poste de ocho metros de altura colocado en el tejado de Westminster Hall, en Londres. En 1685 se bajará del tejado y su cabeza irá cambiando de manos, para ser definitivamente enterrada en los terrenos del Sidney Sussex College, en Cambridge, en 1960, donde Oliver había estudiado. (Hace 363 años)

1648

En Münster (Alemania) se firma la Paz de Westfalia, dando fin a la Guerra de Ochenta Años entre Países Bajos y España. Francia sale ganando, Suecia se consolida como potencia, los Países Bajos logran la independencia y España continuará con su decadencia. (Hace 376 años)

1500

El navegante español Vicente Yáñez Pinzón se convierte en el primer europeo en avistar el río Amazonas, al llegar a su desembocadura. El río también es llamado Marañón. Años más tarde, en 1542, Francisco de Orellana lo recorrerá desde su nacimiento en las selvas peruanas, hasta su desembocadura en el Oceáno Atlántico. (Hace 524 años)

0 notes

Note

I think these are generally fair points, but I wanted to clarify things because I think I wasn’t clear enough and may have overly condensed my explanation.

So regarding the Instrument of Government and the elected Protectorate Parliaments that came after the Instrument, I would say that the difference between the Rump/Barebone’s Parliaments and the Protectorate Parliaments is that the former couldn’t get their act together and work with Cromwell, the latter didn’t want to work with Cromwell any more.

Between Pride’s Purge, the trial and execution of the King, the declaration of the Commonwealth, the gridlock in the Rump and Barebone’s Parliaments, Cromwell’s purge of the Rump Parliament, direct rule by the Council, etc. Cromwell and the Grandees had burned through a lot of political capital/goodwill through constitutional violations. To add some material base to the political superstructure, the gentry were particularly pissed off at paying the taxes needed to pay for the New Model Army and the Commonwealth Navy.

Thus when I wrote about “ the failure to enact the Heads of Proposals in 1647 after the Putney debates, or in 1648 or 1649 after Pride's Purge,” I was essentially referring to both the Heads of Proposals and the Instrument of Government (since one was a revision of the other), but I wasn’t being clear about what I meant. Had Cromwell presented the Instrument earlier and gotten any Parliament to enact it, thus giving himself a veneer of legality, I think the Instruments could have worked as the basis for a conservative Republic. And yes, there were some potential successors who might have been able to pick up the banner of the Good Old Cause after Cromwell’s death: if Henry Ireton hadn’t died of disease in Ireland he would have been a natural pick, if John Lambert hadn’t had his clash with Paraliament that prevented him from putting up a real fight against Monck he also could have done the job. (Although TBH, I think Richard Cromwell’s fight with both the Third Protectorate Parliament and the Grandees of the Army had already done a lot of damage.)

After Oliver Cromwell's death was the Commonwealth doomed, because of structural factors, or a republic like the United Provinces could have survived but it failed because of contingency and individuals' actions? How guilty is Cromwell for not setting solid foundations for the continuity of the Commonwealth?

Yes, the Commonwealth was doomed after Cromwell's death, but the reason why is both structural factors and contingency/agency - because the actions of a few individuals (including but not limited to Cromwell) set those structural factors in motion.

In term's of Cromwell's guilt, I would say that he bears ultimate responsbility for the institutional weaknesses of the Commonwealth. To be totally fair, he did try to fix those weaknesses repeatedly - but because of the actions he took at the beginning that set up the structural factors in question, those efforts came to naught.

That's the TLDR, I'll do the specific explanation below the cut, because it's going to go long.

Background

Just to make sure everyone's on the same page: in 1640, Charles I is forced to call Parliament even though he hates doing it. He dissolves Parliament after three weeks. (Hence why it's called the Short Parliament.) He's then forced to call Parliament again, and this Parliament is the Long Parliament. The Long Parliament enacts a whole series of legislation that Charles I hates, and then in 1642 the conflict between King and Parliament breaks out into the First English Civil War (1642-1646).

During this first phase of the conflict, it takes a while for Parliament and the Parliamentary generals to get their act together. Things begin to turn around in 1644 when the Scottish Covenanters join the war on Parliament's side and they win the Battle of Marston Moor - which gives Parliament control of the North of England and is the first battle where Cromwell plays a major role. The next year, Parliament gets rid of the original Parliamentary generals through the Self-Denying Ordinance, forms the New Model Army under Fairfax and Cromwell (the one guy specifically exempted form the Self-Denying Ordinance), and Fairfax and Cromwell go on to completely destroy the Royalist armies at Nasby and Langport.

Charles hangs on for a bit, but is eventually captured in 1646 and the first Civil War ends. The question is now: what do we do, now that Parliament has won?

The Putney Debates

Once the fighting was over, the political fighting could begin and it was quite complicated. You had the Long Parliament, which was dominated by the moderate "Presbyterian" faction who had been locked out of military power by the Self-Denying Ordinance. You had the New Model Army, which was religiously Puritan but split politically (more on this in a second). You had the Scots, politically constituted by the Scottish Parliament and militarily represented by the Covenanter armies, who wanted Presbyterianism to be extended throughout Britain. And then you had the Royalists and Charles I, who were usually but not always the same faction.

I'm going to focus here on the part of this conflict that involved the Long Parliament and the New Model Army. The Long Parliament wants to do a deal with Charles I - although the problem is that Charles is stretching out negotiations in the hopes that if everything collapses into anarchy he might get himself back on the throne - it wants a unified British Presbyterian Church established (because it had kind of agreed to set one up as the cost of getting Scottish support during the war), and it wants to get rid of the New Model Army which it views as dangerously radical and way too powerful.

The New Model Army isn't sure what it wants, because it's split between the Agitators (i.e, the Levellers) and the Grandees (the senior officers of the Army, led by Cromwell and Fairfax) - although the one thing both sides agree on is that they're not going to accept a single established Presbyterian Church and that they aren't going anywhere until they get their back pay and some sort of reforms happen that justify four years of civil war.

In the mean-time, everyone's getting very testy. First, the Long Parliament orders the New Model Army to disband in early 1647. The New Model Army refuses to disband. Then the New Model Army takes control of the prisoner Charles I in early June. In late June, a pro-Presbyterian mob invades Parliament calling for an established Presbyterian Church and for Charles I to be brought to London, causing all of the Independent (i.e, Puritan) MPs and the Speaker to flee the city and seek the protection of the New Model Army. Then in August, the New Model Army marches on London, and forces Parliament to enact a Null and Void Ordinance undoing everything the Long Parliament had done since June, which causes the Presbyterian MPs to withdraw from Parliament (temporarily), which means the Independents are now in the majority.

All of this is very confusing, and no one in the New Model Army is sure what to do now that they hold all the cards. So the New Model Army decides to have a public debate at Putney in late October in order to hash out what the Army's position is going to be.

At Putney, both sides put forward manifestos for what the Army should stand for. The Agitators put forward the "Agreement of the People," which calls for:

the Long Parliament to be dissolved and elections to be held for a new Parliament.

these elections to be held after a reapportionment of Parliament to establish equal districts on the basis of one-man-one-vote.

elections for a new Parliament every two years.

the electorate to be made up of "all men of the age of one and twenty years and upwards (not being servants, or receiving alms, or having served in the late King in Arms or voluntary Contributions)." (i.e, fairly universal male suffrage).

Parliament is to have full Executive and Legislative authority, except that the people shall have liberty of conscience, freedom from conscription, equality before the law, and there shall be amnesty for anything done or said during the Civil War.

The Grandees, who freaked the fuck out when they heard these terms and started immediately calling the Agitators "Levellers" (i.e, 17th century for "commie bastards"), put forward the "Heads of Proposals," which calls for:

the Long Parliament to be dissolved and elections to be held for a new Parliament.

these elections to be held after Parliament decides on "some rule of equality of proportion...to the respective rates they bear in the common charges and burdens of the kingdom," or on the basis of some other rule that will make the Commons "as near as may be" to equally proportioned.

for the next ten years, Parliament and not the King has authority over the military, finances, and the bureaucracy.

for the next five years, Royalists aren't allowed to run for elected office or hold appointed public offices.

the Church of England will continue to exist, but you don't have to read the Book of Common Prayer if you don't want to, you don't get fined for not going to CoE services or attending other services, and there will be no imposition of a Presbyterian Covenant.

You can see that there are some overlapping areas (no more Long Parliament, elections every two years, some form of reapportionment, some form of liberty of conscience) but there are some really significant differences - a republic versus a constitutional monarchy, a unicameral Parliament versus retaining the House of Lords, and universal suffrage versus property requirements.

During the Putney Debates, Cromwell flatly refuses to accept anything other than a constitutional monarchy, Ireton (Cromwell's son-in-law) refuses to accept universal suffrage, but the two sides agree that a committee will work out a compromise on the basis of everything else from the "Agreement" as long as the Agitators agree to go back to their regiments.

Then the King escapes from captivity and everyone panics. Cromwell and Fairfax scramble a new manifesto together and try to get the New Model Army to approve that manifesto along with everyone taking a loyalty oath to Fairfax and the General Council of the Army, the Agitators see this as a stab in the back and start up a mutiny, and Cromwell and Fairfax crush the mutiny and arrest the Agitator leadership. In late November 1647, Charles I, who has been recaptured by this point, signs a secret agreement with the Scots to invade England and restore Charles to the throne in return for Presbyterianism being established in England.

The Second Civil War

Things slow down for a bit, because the Scots are actually quite divided about this agreement - the Kirk actually condemns it as "sinful" - and it takes until April for the pro-agreement faction (known as the "Engagers") to get a majority in the Scottish Parliament.

In May 1648, Royalist uprisings break out across the kingdom, with South Wales, Kent, Essex, and Cumberland being particular centers of Royalist strength, and the Scottish Covenanter army crosses the border and invades England. Unfortunately for Charles, the Royalists, the English Presbyterians, and the Scots, they completely fail to coordinate their actions and the New Model Army is able to completely crush the uprisings one-by-one and then turns its attention to the Scots.

At the Battle of Preston in August 1648, the New Model Army under Cromwell wins another one of its ridiculously lopsided victories that make his emerging belief that he had been chosen by God somewhat understanable, and the formidable Covenanter army is crushed.

By this point, Cromwell and the rest of the Grandees are convinced of two things: one, no more negotiating with the King. As the Army Council put it rather ominously, it was their duty "to call Charles Stuart, that man of blood, to an account for that blood he had shed, and mischief he had done." Two, the (English) Presbyterians could not be trusted. They had conspired with the King and their Scottish co-religionists to overthrow the government and abolish religious liberty, and thus they had to go.

Thus, in December 1648, Pride's Purge is carried out, in which a detachment of troops acting under orders from Ireton (and thus from Cromwell) bar 140 MPs from taking their seat and arrest 45 of them. This effectively ends the Long Parliament, and the remaining 156 MPs continue to sit as the Rump Parliament. In the New Year, the Rump Parliament then votes to put the King on trial for treason and then afterwards establishes the Commonwealth as a unicameral Republic.

What Comes Next?

You'll note a couple things at this point: first, Cromwell's political positions are fairly fluid and change with events, so that he goes from being a staunch constitutional monarchist in late 1647 to a determined regicide by January 1949. Second, even though it's been a few years since the Putney Debates, Cromwell and the Grandees haven't implemented the "Heads of Proposals" - most crucially, they haven't dissolved Parliament and called for new elections, nor has a new Constitution been established.

Initially, one might say that Cromwell was distracted by his campaign to crush the Confederate-Royalist coalition in Ireland and then to crush the alliance between the Covenanters and Charles II. But by 1651, he's back in England and there's still no election and still no Constitution. Cromwell tries to get the Rump Parliament to call for new elections, establish a new Constitution that incorporates Ireland and Scotland now that they've been conquered, and finds some sort of religious settlement.

For two years, the Rump Parliament deadlocks on practically everything except the religious settlement, where it manages to piss off everyone by keeping the Church of England and its tithes, but also getting rid of the Act of Uniformity and allowing Independents to worship openly, but also passing all kinds of Puritan moral regulations. In April of 1653, Cromwell proposes that the Rump Parliament establish a caretaker government that will deal with the Constitution and new elections, but the Rump deadlocks on that too. This causes Cromwell to completely lose it and dissolve the Rump Parliament by force, culminating in one hell of a speech:

It is high time for me to put an end to your sitting in this place, which you have dishonoured by your contempt of all virtue, and defiled by your practice of every vice; ye are a factious crew, and enemies to all good government; ye are a pack of mercenary wretches, and would like Esau sell your country for a mess of pottage, and like Judas betray your God for a few pieces of money. Is there a single virtue now remaining amongst you? Is there one vice you do not possess? Ye have no more religion than my horse; gold is your God; which of you have not barter'd your conscience for bribes? Is there a man amongst you that has the least care for the good of the Commonwealth? Ye sordid prostitutes have you not defil'd this sacred place, and turn'd the Lord's temple into a den of thieves, by your immoral principles and wicked practices? Ye are grown intolerably odious to the whole nation; you were deputed here by the people to get grievances redress'd, are yourselves gone! So! Take away that shining bauble there, and lock up the doors. In the name of God, go!

Now there's no more Parliament and Cromwell and the Council are running the country on their own, but they don't have a plan for what to do next. A Fifth Monarchist member of the Council proposes appointing a "sanhedrin of saints" on the basis of religious credentials who will set up a godly commonwealth and bring about the imminent return of Christ. That doesn't happen, but the Council does like the idea of an appointed (rather than elected) body called the Nominated Assembly, which becomes known as Barebone's Parliament. This Parliament doesn't make it a year because of how badly it's divided between moderate republicans who want a functioning government and Fifth Monarchists who believe that Jesus Christ is coming back to Earth any day now, so why bother? Ultimately, Barebone's Parliament dissolves itself.

This then leads the Council to pass the Instruments of Government, which was essentially an adapted version of the original "Heads of Proposals." Under the Instrument, Executive power would be held by the Lord Protector who would serve for life, Legislative power would be held by a Parliament elected every three years, and then there would be a Council of State appointed by Parliament which would advise and elect the Lord Protector upon the death of the previous occupant. Thus, the Protectorate is born.

In 1654, Cromwell finally manages to get the First Protectorate Parliament elected...and it only lasts a single term, agrees to none of the 84 bills that Cromwell and the Council of State, and is promptly dissolved as soon as the Instruments would allow. And so on it went through the Second and Third Protectorate Parliaments, and then Cromwell died and the rest is history.

Conclusion

Coming back to what I mentioned at the very beginning about the interplay between structural factors and individual actions, I think we can see a kind of ratchet effect whereby decisions taken early on that foreclosed certain options compound on each other over time, leading to structural factors that weakened the Commonwealth.

The crucial turning point(s) to me are the decision to reject the Agreement of the People in 1647 and then the failure to enact the Heads of Proposals in 1647 after the Putney debates, or in 1648 or 1649 after Pride's Purge.

With the Agreement, you could have had a small-d democratic republic which would have offered ordinary working people new political rights and protections and the opportunity to buy-in to the new regime through an election for a new Parliament. With the Heads of Proposals, you could have had a more conservative republic that would have offered much the same to the traditional landed political class, which would have then granted their consent to the new regime by both standing for election and voting in that election for a new Parliament.

That kind of legitimacy was absolutely necessary in order to ensure the long-term allegiance of the population to the new regime in the face of Royalist revanchism, let alone the kind of radical changes (putting the king on trial, declaring a republic, establishing a religious settlement) that Cromwell and the Grandees saw as essential.

#history#early modern history#english commonwealth#english civil war#oliver cromwell#wars of three kingdoms

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Enjoyed a visit to Nenagh Castle yesterday, home of the Butlers built by Theobald le Boteler c. 1200. A peace treaty was signed between the O'Kennedys and Butlers in 1336. The peace treaty was later broke by the O'Kennedys, O'Carrolls & O'Briens who unsuccessfully attacked the castle but burned Nenagh. In 1550 the town of Nenagh & the Friary were burned by the O'Carrolls. In 1641 the town was captured by Owen Roe O'Neill but later recaptured by Earl Inchiquin. In 1651 the castle was taken by Cromwelian forces under Henry Ireton. The castle was attached to a curtain wall which enclosed a 5 sided courtyard with twin tower gateway on the south wall and a further tower on the east and on the west curtain wall.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Despite my original thoughts before reading more info about Charles I and Oliver Cromwell, Cromwell tried his hardest (with his friend and son-in-law Henry Ireton) to negotiate with Charles. But Charles was stubborn and inflexible. Then as we all know the events that transpired, Cromwell stopped negotiating with Charles and eventually signed his death warrant (along with Ireton and others).

What happened? According to Antonia Fraser, Cromwell and Ireton came across a letter that exposed Charles’s duplicity and some say snake-like behavior (but even Fraser has doubts about the credibility of the story). According to Leanda de Lisle, it was his experiences during the First English Civil War that radicalized Cromwell so much so that he was wanting to get rid of the King no matter what in God’s name (if I’m remembering correctly).

As with me, I really don’t know what to think. I think there was a small chance that both Charles and Cromwell could have come up with a compromise of some sort. But both men were stubborn as hell. I also think Cromwell lost patience and the rest is history. I know there is more to it, but that’s what I’m intuitively thinking right now.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Robert Walker - Elizabeth Bourchier, Lady Protectress of England, Scotland and Ireland -

Robert Walker (1599–1658) was an English portrait painter, notable for his portraits of the "Lord Protector" Oliver Cromwell and other distinguished parliamentarians of the period. He was influenced by Van Dyck, and many of his paintings can now be found at the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Walker was the chief painter of the parliamentary party during the Commonwealth of England from 1649 to 1660. Nothing is known of his early life. His manner of painting, though strongly influenced by that of Van Dyck, is yet distinctive enough to rule out the possibility of him being one of Van Dyck's immediate pupils.

He is chiefly known for his portraits of Oliver Cromwell, and our knowledge of Cromwell's appearance is mainly based on Walker's paintings, as well as the portraits of him by Samuel Cooper and by Peter Lely. There are two main types. The earlier, representing Cromwell in armour with a page tying on his sash, and the later, full face to the waist in armour, were frequently repeated and copied.

The best example of the first type is perhaps the painting now in the National Portrait Gallery (formerly in the possession of the Rich family). This likeness was considered by diarist John Evelyn (1620–1706) to be the truest representation of Cromwell which he knew. There are repetitions of this portrait elsewhere. In another portrait by Walker, Cromwell wears a gold chain and decoration sent to him by Queen Christina of Sweden.

Walker painted Henry Ireton, John Lambert (examples of these two in the National Portrait Gallery), Charles Fleetwood, Richard Keble and other prominent members of the parliamentary government. John Evelyn himself sat for him, as stated in his Diary for 1 July 1648: "I sate for my picture, in which there is a death's head, to Mr. Walker, that excellent painter"; and there is another entry on 6 July 1650: "To Mr. Walker's, a good painter, who shew'd me an excellent copie of Titian". This copy of Titian, however, does not appear, as sometimes stated, to have been painted by Walker himself. One of Walker's best paintings is the portrait of an unknown man – formerly thought to be William Faithorne the elder – now in the National Portrait Gallery.

In 1652, on the death of the Earl of Arundel, Walker was allotted apartments in Arundel House, which had been seized by the parliament. He is stated to have died in 1658.

Walker painted his own portrait three times – one is at the National Portrait Gallery, which also houses two engravings of portraits of Walker by other artists (one was finely engraved in his lifetime by Peter Lombart). Another example, with variations, is in the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

#OTD in Irish History | 26 May:

1562 – Following his submission to Elizabeth at Whitehall in January, Shane O’Neill returns to Ireland on this date. 1650 – Oliver Cromwell leaves Ireland on board the frigate President Bradshaw. His deputy and son-in-law, Henry Ireton takes control of the Irish campaign and captures Birr Castle. 1798 – United Irishman Rebellion: The rebels are defeated at Tara Hill; this marks the end of the…

View On WordPress

#irelandinspires#irishhistory ireland#OTD#1798 United Irishmen Rebellion#26 May#Bram Stoker#Clerkenwell Gaol#Co. Clare#Dáil Eireann#Dracula#History#History of Ireland#Ireland#Irish History#Irish War of Independence#Jack Charlton#Kilkee#Michael Barrett#Mickey Devine#Oliver Cromwell#Shane O&039;Neill#Today in Irish History

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On This Day In Royal History . 17 October 1660 . The Nine regicides who signed the death warrant of Charles I of England are hanged, drawn & quartered on the orders of Charles II. . Background: After Charles I’s execution at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War, England entered the period known as the English Interregnum or the English Commonwealth, & the country was a de facto republic led by Oliver Cromwell. Cromwell died in 1658 & was succeeded as Lord Protector by his son, Richard. However, the new Lord Protector had little experience of either military or civil administration. In 1659 Richard resigned. The English Parliament resolved to proclaim Charles Stuart as king & invited him to return to England. Charles agreed he would not exile past enemies nor confiscate their wealth. There would be pardons for nearly all his opponents ‘except the regicides’. (regicides basically means king killers) . The new king: Charles II set out for England from Scheveningen, arrived in Dover on 25 May 1660 & reached London on 29 May, his 30th birthday. . Although Charles & Parliament granted amnesty to nearly all of Cromwell’s supporters in the Act of Indemnity & Oblivion, 50 people were specifically excluded. In the end nine of the regicides were executed: they were hanged, drawn & quartered; others were given life imprisonment or simply excluded from office for life. . Cromwell’s body was exhumed from Westminster Abbey on 30 January 1661, the 12th anniversary of the execution of Charles I, & was subjected to a posthumous execution, as were the remains of John Bradshaw, & Henry Ireton. (The body of Cromwell’s daughter was allowed to remain buried in the Abbey.) His body was hanged in chains at Tyburn, London, & then thrown into a pit. His head was cut off & displayed on a pole outside Westminster Hall until 1685. . . . https://www.instagram.com/p/CGdTtU5DbK8/?igshid=1me31d76nt50d

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pride’s Purge: ‘I verily think that God will break that great idol the Parliament and that old job-trot form of government,’

The End of the Long Parliament

Pride’s Purge. Source: Wikipedia

IT CANNOT be underestimated just how much fury now existed towards the King in the ranks of the New Model Army and the Independent faction within Parliament. By inciting a resumption of fighting in England, Charles had persuaded the radicals there was no point in further negotiations with him. He had visited war once again upon his Kingdoms, even encouraging an invasion of England by the Scots. In the eyes of the Army and the Independents, the events of the late summer of 1648 had demonstrated the veracity of the Biblical prophecy of the “Man of Blood” and there could be no further dealing with such a Satanic figure. However, the moderate Presbyterian faction in the House of Commons which still comprised the majority of MPs, had not yet despaired of reaching a settlement with Charles. In fact their suspicion of the intentions of the Army and its Parliamentary allies, which they saw moving further and further towards advocating a new democratic and republican constitution, meant they viewed an accord with the monarchy and its retention as a safeguard of land holding and the power of the gentry, as essential.

On 1st September 1648, therefore, Parliament once again resumed negotiations with the King. These took place at Newport on the Isle of Wight, and the fifteen commissioners appointed by Parliament represented the range of opinion within Parliament with the exception of Leveller-inspired democratic radicalism. The negotiations went well. Most of the Parliamentary demands mirrored that of the Engagement, concessions the King had already made. He acceded to surrender of the control of the militias to Parliament for twenty years; he agreed to relinquishing all interest in the governance of Ireland and crucially, he also agreed to a three year introduction of Presbyterianism as a new national Church, as agreed with the Scots. However, Charles could not bring himself to agree to the permanent abolition of episcopacy: the rule of bishops and the Book of Common Prayer were the essence of the King’s Anglican belief, and on this issue, which had divided the monarch from swathes of his people for fifteen years, there could no compromise. Charles knew this meant a settlement was probably impossible and exile in France, where many of his supporters had already fled, was appearing an attractive alternative to abdication or trial. The King again began to look for opportunities for escape.

In the meantime, opinion within the Army was hardening. The Levellers, who had been suppressed after the Putney Debates but not crushed, reasserted their influence amongst the rank and file with the publication of the Humble Petitions of Well-Affected Persons, a restatement of much of the previous tract, the Agreement of the People, which had been presented at Putney. A call for annual elections, universal male franchise, religious toleration, free trade and trial by jury was restated. However, the Grandees were not united in the face of Army discontent: Thomas Fairfax based himself at St Albans and declared himself against radical re-ordering of the constitution and restricted himself to demands for pay arrears for his soldiers; Oliver Cromwell busied himself in the north reducing Royalist hold outs, while Henry Ireton felt obliged to support the Army’s insistence that the Newport negotiations did not result in Charles resuming his throne in anything but the most symbolic manner. In November, Ireton produced the Remonstrance of the Army and submitted it to the senior officers of the Army Council in Windsor. The Remonstrance was uncompromising: it called for the end of the Newport negotiations, the abolition of the monarchy and the bringing of Charles himself to trial for waging war on his own subjects. The Remonstrance also called for an end to the Long Parliament and the election of a new House of Commons on a much wider franchise. The radicalism of the Remonstrance was surprising given its author, but Ireton was genuinely fearful that a Newport Treaty might place Charles back on his throne with a real possibility of a Royalist resurgence, accompanied by mutiny or insurgency by the New Model Army: supporting the Army radicals seemed the only way to safeguard the existing gains of the Civil War.

The Grandees debated the Remonstrance at the Nag’s Head Tavern in St Albans. Fairfax tried one final time to contrive the circumstances under which a constitutional monarchy could be created, and issued a position agreed by the Council of Officers to the Parliamentary commissioners which would create a settlement that maintained the monarchy but created a constitutional role for the Army: Charles rejected the proposal. Therefore on 20th November, the Army Council submitted the Remonstrance to Parliament. The House of Commons were disconcerted by the bill as the Remonstrance would have effectively abolished the existing Parliament. MPs tabled a four day debate by which time they hoped a Newport Treaty with the King would be concluded, and eventually rejected the Remonstrance altogether. However, the Army moved quickly. Loyal troops were sent to Newport and Carisbrooke to forestall any escape attempt by Charles, and troops occupied London, Fairfax installing himself in Whitehall itself. On 1st December, the King was removed from the Isle of Wight and brought back to the capital. The Newport negotiations were over.

The stage now seemed set for a military-led dissolution of Parliament, but events took a curious turn. A delegation of Independent MPs approached Ireton and suggested instead of the imposition of full military rule, a more constitutional solution to the conflict might be to bar all pro-Treaty MPs from the Commons and then they helpfully provided the general with a list of all Members who still favoured engagement with the King. On 6th December, Ireton ordered a troop of soldiers under Colonel Thomas Pride to bar the entrance to the Commons. As MPs arrived for the business of the day, their names were checked against the list. If they were on the list, they were arrested. This performative coup lasted six days. By 12th December, just 156 MPs of a total Commons of 450 representatives remained. The Long Parliament had effectively been dissolved: its successor became derisively known as the “Rump Parliament”. The Rump was indeed a wholly unconstitutional body. When one outraged barred MP demanded of Pride on what authority the purge was being carried out, he was told: ‘by the power of the sword, sir.’

Fairfax was furious at Ireton’s action, but as so often when a situation becomes revolutionary, events have their own momentum. The Rump MPs were fully supportive of both the coup and the Remonstrance, which was immediately passed. By 1st January 1649, Parliament had resolved that Charles should be brought to trial by a High Court of Justice for the crime of waging war on England. Cromwell returned to London and the Grandees met in an atmosphere of doubt and guilt. They had no assurance that the coup would be successful or how the country outside the capital might react at the news that the King was to be put on trial for his life. There was fear a third civil war could break out. Cromwell initially hoped a means of avoiding a trial could yet be achieved by persuading the King to abdicate in favour of his third son, Henry Duke of Gloucester, conveniently in Parliament’s custody. However Charles, now seemingly increasingly fatalistic, remained obdurate and refused to countenance the idea. Cromwell then decided there was only one course of action that would preserve the victory of the Army and Parliament and ensure no return to absolute rule : the King had to die and with his death, so must die the monarchy itself.

#english civil war#King Charles I#oliver cromwell#thomas fairfax#Henry Ireton#Thomas Pride#Pride’s Purge#the Levellers

0 notes

Text

The site of The Whalebone, 41 Lothbury....

....is now home to somewhat more dubious, money-making, outfits. Formerly the street was known for coppersmiths and pewterers in the Middle Ages

https://photos.app.goo.gl/Gug21UupacpS2iMu9

Location of The Whalebone (arrowed) on Ogilby and Morgan's Large Scale Map of the City As Rebuilt By 1676 Source : https://www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/london-map-ogilby-morgan/1676 [Wikkipedia says: “The Whalebone was an eatery on Lothbury in the City of London that was a meeting place for the Leveller movement. The Levellers described themselves as "whaleboners" in an early printed declaration, and their leader John Lilburne would read various declarations and lead meetings there. Henry Ireton, Oliver Cromwell's son-in-law, sent spies to the Whalebone to observe the Levellers. It was referred to as one of the Levellers' 'Houses of Parliament” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whalebone_(Lothbury)#cite_note-londontop-1]

0 notes

Photo

On December 16th 1653 Oliver Cromwell became Lord Protector of England, Scotland and Ireland.

Cromwell was the military political leader best known for overthrowing King Charles I and leading the Commonwealth of England. He ruled England, Scotland, and Ireland as Lord Protector from 1653 until his death in 1658.

He passionately advocated religious liberty and equitable justice, that is unless you were a Roman Catholic. Cromwell tortured blasphemers and imprisoned critics. The way he treated the Catholics in Scotland and Ireland has been characterised as genocidal or near-genocidal.

Cromwell was the only invader of Scotland to conquer the whole country. He was King in all but name, historians are divided about him, to some he was a dictator, to others a hero.

The most famous story of Cromwell’s dealings in Scotland, was his attempts to capture the Honours of Scotland, our crown jewels, were thwarted after they were smuggled out of Dunnottar Castle.

After having Charles I head lopped off in January 1649, Cromwell beat his son, Charles II at Worcester in 1651, who fled to Europe where he stayed in exile, he had been crowned in Scotland before his failed invasion of England.

A political crisis followed the death of Cromwell in 1658 which resulted in the restoration of the monarchy, and Charles was invited to return to to take the throne in 1660.

Cromwell’s body was exhumed from Westminster Abbey and was subjected to the ritual of a posthumous execution. His body was hanged in chains and disinterred at Tyburn, eventually being thrown into a pit. His severed head was displayed on a pole outside Westminster Hall until 1685. His skull is said to have passed through many peoples hands since then, at times people were charged half-a-crown to view it.

By 1865, it had passed into the possession of a Mr. Williamson of Beckenham. His family donated it to Sydney Sussex College, (where he was educated), in 1960. At one time there were even two “authentic” Cromwell skulls on sale in London simultaneously. The owner of the second, smaller skull explained that his version was obviously that of Cromwell when he was a boy- really aye lol. It was buried beneath the floor of the college that year.

The pictures are of the man and his death mask which is displayed at Warwick Castle, the other pic is a contemporary engraving depicting the execution of Cromwell, Bradshaw and Ireton (whose heads are on poles labelled 1, 2 and 3 in that order). John Bradshaw was a lawyer and politician, who was head of the judiciary that condemned Charles I to death, Henry Ireton was a general in the Parliamentarian army, but also Cromwell’s son in law, both of their bodies were also exhumed. Their heads are on poles labelled 1, 2 and 3 in that order in the pic.

3 notes

·

View notes