#happy days samuel beckett

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

happy days by samuel beckett annotated by my friend

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

L'amica geniale S02E04 (Il bacio)

Book title: Il teatro di Samuel Beckett (1961) by Samuel Beckett

The plays included in this Einaudi edition are

Aspettando Godot (Waiting for Godot in English; 1949)

Finale di partita (Endgame in English; 1957)

Atto senza parole (Act Without Words in English; 1957)

Tutti quelli che cadono (All That Fall in English; 1956)

L'ultimo nastro di Krapp (Krapp's Last Tape in English; 1958)

Ceneri (Embers in English; 1958)

Atto senza parole II (Act Without Words II in English; 1959)

Giorni felici (Happy Days in English; 1961)

#l'amica geniale#l'amica geniale season 2#my brilliant friend#my brilliant friend season 2#il bacio#il teatro di samuel beckett#samuel beckett#irish literature#waiting for godot#happy days#embers#act without words#act without words ii#krapp's last tape#all that fall#endgame#books in tv shows

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Getting by

#my days are long and boring#on the plus side I finished women in love today#it slapped#now moving onto Samuel Beckett’s happy days#diary

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

who want to complete an absurd duo while doing nothing and only waiting for the end (of what?) without wanting or not to leave, with me? 🥺💖

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

啊,美好的一天!Happy Days!------ 2023年夏天在阿那亚演出

0 notes

Text

First Look! The last few months I’ve been working diligently on designing & directing an upcoming production of Samuel Beckett’s “Happy Days” — Opening March 17th at Chicago’s City Lit Theater. The set, the mound that’s slowly consuming the protagonist, was made exclusively of recycled materials. Her world consists of collapsed materials, musique concrete, isolation & electricity.

#theatre#Theater#director#sculpture#jon dambacher#Samuel Beckett#Happy Days#Kayla Boye#Chicago#Chicago theatre#artist#announcement#St. Patrick’s Day#musique concrete

0 notes

Text

Even though John is under-powered in this period we still see what made him so magnetic to Paul and to others around him. There is a scene early in Part Two that I find riveting. It takes place a couple of days after George has left. The status of everything - the project, the band - remains uncertain, but they are ploughing on for now. John, Yoko, Ringo, Paul and some of the crew are sitting in a semi-circle. Paul looks pensive. Ringo looks tired. John is speaking only in deadpan comic riffs, to which Paul responds now and again. Peter Sellers comes in and sits down, looks ill-at-ease, and leaves having barely said a word, unable to penetrate the Beatle bubble. At some point they’re joined by Lindsay-Hogg, and the conversation dribbles on. John mentions that he had to leave an interview that morning in order to throw up (he and Yoko had taken heroin the night before). Paul, looking into space rather than addressing anyone in particular, attempts to turn the conversation towards what they’re meant to be doing:

Paul: See, what we need is a serious program of work. Not an endless rambling among the canyons of your mind.

John: Take me on that trip upon that golden ship of shores… We’re all together, boy.

Paul: To wander aimlessly is very unswinging. Unhip.

John: And when I touch you, I feel happy inside. I can’t hide, I can’t hide. [pause] Ask me why, I’ll say I love you.

Paul: What we need is a schedule.

John: A garden schedule.

I mean first of all, who is writing this incredible dialogue? Samuel Beckett?

Let’s break it down a little. The first thing to note is that John and Paul are talking to each other without talking to each other. This is partly because they’re aware of the cameras and also because they’re just not sure how to communicate with each other at the moment. John’s contributions are oblique, gnomic, riddling, comprised only of songs and jokes, like the Fool in King Lear. Take me on that trip upon that golden ship of shores sounds like a Lennonised version of a line from Dylan’s Tambourine Man (“take me on a trip upon your magic swirling ship”). “We’re altogether, boy”? I have no idea. Does Paul? I think John expects Paul to understand him because he has such faith in what they used to call their “heightened awareness”, a dreamlike, automatic connection to each other’s minds. But right now, Paul is not much in the mood for it. His speech is more direct, though he too adopts a quasi-poetic mode (“canyons of your mind” is borrowed from a song by the Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band) and he can’t bring himself to make eye contact. “To wander aimlessly is very unswinging,” he says (another great line, I will pin it above my writing desk). Then John does something amazing: he starts talking in Beatle, dropping in lyrics from the early years of the band, I Want To Hold Your Hand and Ask Me Why. (To appreciate John’s response to Paul’s mention of a schedule, American readers may need reminding that English people pronounce it “shed - dule”.)

What’s going on throughout this exchange? Maybe Lennon is just filling dead air, or playing to the gallery, but I think he is (also) attempting to communicate to Paul in their shared code - something like he loves him, he loves The Beatles, they’re still in this together. Of course, we can’t know. I can’t hide, John says, hiding behind his wordplay.

— Ian Leslie, "The Banality of Genius: Notes on Peter Jackson's Get Back" (January 26, 2022).

[I was curious to read more of Ian Leslie's approach to the Beatles in general and Lennon-McCartney in particular, since he's currently writing a book about John and Paul's relationship: “John and Paul: A Love Story in Songs". He's also the author of that New York Times opinion piece that came out today.]

#The Beatles#John Lennon#Paul McCartney#Get Back sessions#the person i actually picked as my partner#johnny#macca#I Want to Hold Your Hand#Tell Me Why#But I could never speak my mind#As we share in each other's minds#quote#my stuff#That Paul and John business

196 notes

·

View notes

Text

April 29, 2023: June, Alex Dimitrov

June Alex Dimitrov

There will never be more of summer than there is now. Walking alone through Union Square I am carrying flowers and the first rosé to a party where I’m expected. It’s Sunday and the trains run on time but today death feels so far, it’s impossible to go underground. I would like to say something to everyone I see (an entire city) but I’m unsure what it is yet. Each time I leave my apartment there’s at least one person crying, reading, or shouting after a stranger anywhere along my commute. It’s possible to be happy alone, I say out loud and to no one so it’s obvious, and now here in the middle of this poem. Rarely have I felt more charmed than on Ninth Street, watching a woman stop in the middle of the sidewalk to pull up her hair like it’s an emergency—and it is. People do know they’re alive. They hardly know what to do with themselves. I almost want to invite her with me but I’ve passed and yes it’d be crazy like trying to be a poet, trying to be anyone here. How do you continue to love New York, my friend who left for California asks me. It’s awful in the summer and winter, and spring and fall last maybe two weeks. This is true. It’s all true, of course, like my preference for difficult men which I had until recently because at last, for one summer the only difficulty I’m willing to imagine is walking through this first humid day with my hands full, not at all peaceful but entirely possible and real.

--

(June is my birthday month and also the best month. Sorry, I don’t make the rules.)

More like this: » Steps, Frank O'Hara » After Work, Richard Jones » Dolores Park, Keetje Kuipers » Awaking in New York, Maya Angelou » A Step Away From Them, Frank O'Hara

Today in:

2022: Poem to My Child, If Ever You Shall Be, Ross Gay 2021: Choi Jeong Min, Franny Choi 2020: Earl, Louis Jenkins 2019: Kul, Fatimah Asghar 2018: My Life Was the Size of My Life, Jane Hirshfield 2017: I Would Ask You To Reconsider The Idea That Things Are As Bad As They’ve Ever Been, Hanif Abdurraqib 2016: Tired, Langston Hughes 2015: Democracy, Langston Hughes 2014: Postscript, Seamus Heaney 2013: The Ghost of Frank O’Hara, John Yohe 2012: All Objects Reveal Something About the Body, Catie Rosemurgy 2011: Prayer, Marie Howe 2010: The Talker, Chelsea Rathburn 2009: There Are Many Theories About What Happened, John Gallagher 2008: bon bon il est un pays, Samuel Beckett 2007: Root root root for the home team, Bob Hicok 2006: Fever 103°, Sylvia Plath 2005: King Lear Considers What He’s Wrought, Melissa Kirsch

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

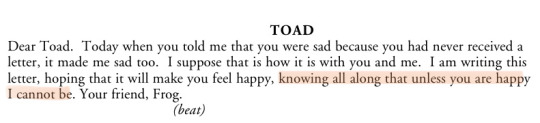

pair of rabbits

1) a year with frog and toad, willie reale 2) midsummer night’s dream, wikipedia 3) rosencrantz and guildenstern are dead, tom stoppard 4) on the romance of cannibalism, silas denver melvin 5) happy days, samuel beckett

#l564#mika moments#skipping the middleman. i can tag my ocs in my own webweave post guys. hashtag revelations hashtag enlightened#also i knowwwwwits all theater shit PLZ spare me

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

SAMUEL BECKETT Happy Days

Strange feeling that someone is looking at me. I am clear, then dim, then gone, then dim again, then clear again, and so on, back and forth, in and out of someone’s eye.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rebecca Ferguson: The first to ask questions in the intview

Ferguson calls via videocall from London and takes the interview in her own hands.

Rebecca Ferguson: Before we start I'd like to ask whats there behind you on the table. Sorry, I like to see through zoom-interviews the rooms of my intviewers.

ICONIST: What particular are you interested in?

Ferguson: The first book in the pile, for example.

ICONIST: I have to take a look for myself now. Here, "Bill Gates. How the prevent the next pandemic."

Ferguson: Oh. Does Bill have some good advice in it?

ICONIST: It's complicated. Gates had already warned of the dangers of such pandemics before the Covid outbreak. He later received death threats because one of his quotes, taken out of context, was used to create the grotesque fake news that he wanted to use the corona virus to microchip all of humanity. With that, we could now seamlessly move on to the conspiracies in your new series, Silo, in which no one knows which stories about human threats are true and which are fabricated.

Ferguson: *laughs* You are right.

ICONIST: The world has been destroyed, 10,000 people have survived in an underground silo, locked up there, isolated from the outside world. Nobody knows what really happened outside. You're not entirely wrong to take this as a depressing parable of the pandemic, are you?

Ferguson: There are certainly many parallels to events that happened not so long ago - the horror of the Covid lockdowns, governments wanting to control their environment, scarcity of resources and the need to recycle in order to survive. Only the novels on which the series is based have been published since 2011. And as an actress, what interests me most is the quality of the storytelling and the characters. When I was working on this role, I didn't think too much about whether the future society in the film had anything to do with today's society. To be honest, I don't want to think about the future of the world because sometimes it gets me pretty depressed. I am aware that I lead a very privileged life and that I am very fortunate. Don't get me wrong: it's important to me to speak my mind, for example I'm fighting for equality at every level. I accept those battles that I am convinced I must fight. Other than that, I just try to be friendly to others.

ICONIST: Your series about the silo society offers less action-packed science fiction escapism, instead it relies more on dialogue. It is reminiscent of Samuel Beckett's end-time visions in his play "Happy Days" - with two actors who are stuck in a mound of earth after an apocalypse, sink into it and console themselves with purposeful optimism about their hopeless situation.

Ferguson: I love your reference to Samuel Beckett *laughs* Makes perfect sense. I've done a lot of research on depression and trauma to better understand the loneliness, grief, and loss that weighs on my character. And I like philosophy. The theses of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Thomas Hobbes, for example, both of which assume the natural equality of human beings, i.e. that humans are good by nature and only become evil through society. It was interesting to transfer such thoughts to the film, to ask oneself: What happens when you condense this thesis and show what happens when many people are isolated in a room closed off from the outside world? And when down there one lie about the alleged causes of the catastrophe is followed by another. Do people rebel against lies? Regardless of the penalties they face? Those were the basic questions that fascinated me about this series.

ICONIST: The series is based on Hugh Howey's internationally successful best-selling trilogy "Wool", which is adored by fans. Did you feel pressure to live up to expectations? There are enough examples of film adaptations of fantasy and science fiction novels that have been torn apart by fans.

Ferguson: No, I didn't feel any pressure. It's great that this book series was so successful and has so many fans. I can only do my best. If people don't like it, that's unfortunate, but then there's nothing you can do about it. However, before I engage more intensely with such a role, I always do a lot of research on fan sites. I spend hours reading all sorts of things there.

ICONIST: Why are you doing that?

Ferguson: Because I often discover interesting details on these sites. For example, if a fan writes, "I love how the author describes how Juliette keeps her hand in a pocket the whole time." That's a small but significant detail. I said to myself, "Great, I'm going to do this the whole time through the shoot."

ICONIST: You say you don't like to think about the future too often. In a podcast "Spark Hunter" published in 2022, you dealt with the currently much discussed topic of the future of artificial intelligence. Actress Trudie Styler, wife of Sting, directed. What appealed to you about recording a podcast – actually more of a radio play – in addition to all your film commitments?

Ferguson: I like Trudie very much. When she called me one day and asked, "Do you want to do a radio play with actor Mark Rylance?" I immediately said, "If Mark Rylance is in, I'll be in, no matter what it is." Then sent me the scripts and I got scared at first.

ICONIST: Why?

Ferguson: Because it was pretty complicated stuff, with a lot of details about AI. It was just hard to understand at first. Mark Rylance voicing the inventor of a female artificial intelligence robot whom I speak. And then suddenly this robot starts to develop feelings, it takes pleasure in provocation and in questioning society. And reveals morbid feelings about human life - it's brilliant.

ICONIST: Sting also has a small speaking role in the podcast. In 1984 he had an unforgettable scene as an actor in David Lynch's film adaptation of "Dune - the desert planet" as the villain Feyd-Rautha Harkonnen. There he stands with an oiled naked body, only wearing a futuristic loincloth, which he himself once described as the "first example of flying underpants".

(Rebecca Ferguson is laughing)

You can be seen as Lady Jessica in Dennis Villeneuve's remake of Dune. While working on the podcast, did you and Sting talk a bit about how sci-fi staging has changed over the past 40 years?

Ferguson: We actually did. I remember sitting with him and his wife at a table in their beautiful home at their winery in Tuscany. At one of our long dinners, I asked him, "Do you know what I'm filming?" "No," he said, "what?" Then I revealed to him that we were remaking Dune. And then his eyes suddenly lit up and we went on a long journey in our conversation, talking about what it was like shooting the first film back then, compared to the new one.

ICONIST: And the flying underpants?

Ferguson: (laughs) I won't give you any details, that's between Sting and me.

ICONIST: In winter comes the second part of the Dune film adaptation, in which you again play Lady Jessica, the mother of the young hero Paul Atreides. In the summer you can also be seen again as MI6 agent Ilsa Faust alongside Tom Cruise in "Mission: Impossible - Dead Reckoning" - and already in the ten parts of the Apple TV series "Silo". it doesn't get any better. Aren't you afraid of overexposure?

Ferguson: No. This is going to be a big year for me, with three very different film productions that I'm very proud of. Things like that don't happen all the time. I don't worry too much about it. I'm damn happy it turned out that way. You never know if something like this will happen again. Actors often come into the limelight very quickly, but then just as quickly go out of fashion. Age is often not helpful either. In that sense, I feel like I'm in a good place right now. I've been very lucky.

ICONIST: It is your third appearance in the Mission: Impossible series and your second in Dune. Is it also important for you to have something like consistency in big blockbusters, in times of intensifying competition between film studios and streaming providers with an unprecedented oversupply of films, in which there are also rows and rows of flops?

Ferguson: It's actually nice that I now know my role in "Mission: Impossible" well, because working on the set is complicated because we often don't have finished scripts. Working on the Mission: Impossible movies is so different from other movies. But that's what makes it so exciting. I know my role, but I'm always getting to know new actors who are in for the first time. In their eyes, I can immediately see what they're thinking when they're on set for the first time: "What the hell…?" Then I just think to myself: "I know that, I felt the same way at first." Then it's nice, when you are already familiar with your role. Lady Jessica in "Dune" is also a cool woman. In the second part, however, she is changed. I won't reveal any details now. Just this much: Your performances in the second part are so different from those in the first that it felt like I was playing a new person.

ICONIST: What does it do to you when you switch from one large-scale production to the next?

Ferguson: Well, while I was shooting Silo, I got a message that I had to do some reshoots on the Mission: Impossible movie. I love that kind of thing yeah You always think you need breaks. Until it suddenly: "We need you for four days in June to reshoot scenes for 'Mission: Impossible'." Then you're suddenly sucked in again. I love that because I love the roles too. It sure would be bad if I had to work on set in a terrible environment. That's not the case. It is great.

translated from German by @edwardslovelyelizabeth exclusively for @rebeccalouisaferguson

#rebecca ferguson#interview#silo interview#dune interview#mi7 interview#spark hunter#dune part two interview

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

When Genocide Is the Best Option

I played the Mass Effect trilogy for the first time during the summer of 2022, and it broke my brain. So I played it again over the last six months, trying to figure out why it did what it did to me, and after finishing it again last week, I’ve had the same reaction of intense grief I did the first time. I know I’m a newbie and a decade late to this game, but I’ve tried to piece together what it is about the ending that’s so brilliant and so terrible. And in true English major form, I’ve written 3000 words to try and exorcise it from my head.

It starts with the ending of Stranger Than Fiction.

In Stranger Than Fiction, a boring accountant named Harold Crick (played by Will Ferrell in the best performance of his career) one day starts hearing a voice in his head (Emma Thompson, my love), narrating his life. It’s annoying, but bearable, up until the day he adjusts the time on his wristwatch and the Author says, “Little did he know this simple, seemingly innocuous act would result in his imminent death.”

Understandably perturbed, Harold seeks to prevent this, ultimately by seeking the Author out and trying to convince her not to finish typing out the book and, presumably, his death. (The unexplained magical realism in this movie is absurdity on par with Samuel Beckett, I can’t tell you how much I love it.) She handwrites the ending for him to see, and Harold shows it to a Professor friend (Dustin Hoffman!) who tells him, “Even if you avoid this death, another will find you and I guarantee that it won't be nearly as poetic or meaningful as what she's written.” And Harold agrees once he reads it too, because in it, he saves a little boy. Isn’t that what we all want, for the end of our stories to have meaning?

But the Author ends up changing the ending. When the Professor reads the finished story with the new, happier ending where both the boy and Harold live, he’s clearly disappointed. They have this exchange:

Professor: It's okay. It's not bad. It's not the most amazing piece of English literature in several years. But it's okay. Author: I think I’m fine with okay. Professor: Why did you change the book? Author: Lots of reasons. I realized I just couldn't do it. Professor: Because he's real? Author: Because it's a book about a man who doesn't know he's about to die and then dies. But if the man does know he's going to die and dies anyway, dies willingly, knowing he could stop it, then...I mean, isn't that the type of man you want to keep alive?

Shepard is the type of person you want to keep alive.

The series does a good job of getting us attached to Shepard, so it’s natural that we want a happy ending for them. We want The Good Ending. And we’ve been trained by the last century-or-so of western fiction heroes’ journies to expect The Good Ending, too. We expect Frodo and Sam to be rescued from Mount Doom by the eagles. We expect Cloud to beat Sephiroth and come out the other side, whole. And even when the protagonist does die—think the Hero of Fereldan choosing not to sleep with Morrigan, or the wipeout of the team in Rogue One, or the dad dying in Life Is Beautiful—it’s usually a sacrifice ultimately in service of The Good Ending. The world is left better because of the hero’s death—a choice that isn’t really a choice, because we expect The Good Ending.

But instead, at the very last moment, Mass Effect throws us into the cruelest version of the Trolley Problem imaginable.

On track one, if you choose to keep the trolley on its original path, you Destroy all AI. Which means you kill a valued member of your crew and an entire race of sentient synthetics in cold blood. Sure, Shepard (probably) lives at the very end, but this is definitionally Not The Good Ending. The hero can’t commit genocide and still be the hero. And the idea that Shepard could live with themselves after making that choice isn’t consistent with Paragon morality. Maybe if your Shepard is a Renegade, they become an antihero in this moment, but it’s still not The Good Ending as we understand it.

So jump to track two, and choose to Control the trolley and drive it away from death toward new purpose. Which is fine, except that a) the whole arc of the third game shows that Control isn’t possible and is actually evil, embodied in the mission of Cerberus and the person of the Illusive Man; and b) Shepard is then no longer Shepard at the end of the story—they’ve lost the humanity they’ve been fighting so desperately to preserve, stripped away to become the closest thing the galaxy has to a god. Maybe they’re a good god for a hundred years, or even a thousand, but maybe the Leviathans’ Intelligence was, too. Can we expect Shepard-without-humanity not to eventually turn into the Catalyst? To say that the only way to save humanity is to “preserve” it? Renegade Shepard even says in the epilogue, “I will destroy those who threaten the future of the many”; Paragon Shepard’s version, “I will act as guardian for the many,” isn’t much better. Who decides who’s the many? Autocracy can’t be The Good Ending.

Track three’s gotta be The Good Ending then, right? The game certainly presents it as such: Synthesis, the ultimate bridge of understanding between organics and synthetics. The only way to truly achieve peace, argues the Catalyst. It’s the central option in that final chamber, it’s the shortest path to walk to, it’s literally colored lifestream!green. And it’s a completely violation of the bodily autonomy of every living creature in the entire galaxy. The body horror’s real on this one, y’all. I actually picked Synthesis on my first playthrough because of how clearly it was presented as The Good Ending, but watching the epilogue…I mean, it’s great for EDI. Probably great for Joker too. But then I saw the little green circuitry flash across James’s face during Shepard’s memorial and I thought, This guy? The body-as-a-temple guy? No way he’s okay with any of this. Imposing your will on an entire galaxy full of sentient beings feels inconsistent with The Good Ending.

Those are our choices in the final moments of the game. And honestly, the most nearly moral choice is probably track one. Control, at best, pauses the cycle until AI Shepard decides to start the cycle of reaping again. Synthesis takes away the freedom of all sentient creatures—even those who aren’t spacefaring yet, which: imagine if we today suddenly got Synthesized, the chaos that that would bring—to be themselves. So we’re left with Destroy. Think about that. From a certain point of view, genocide is the most nearly moral decision. Which means there is no moral decision.

There is no Good Ending.

In trying to come to terms with the ending, I’ve read a lot of takes about how the writing is bad. I just don’t think that’s the case. I rather think it’s some of the most brilliant writing in Bioware’s canon, precisely because it’s so uncomfortable. Maybe the Choice comes a little bit out of nowhere, though it’s vaguely hinted at in certain descriptions of the Crucible War Assets, like how the Crucible “tunes into the mass relays' command switches” for “the safe discharge of tremendous amounts of energy”, producing “some kind of energetic pulse that might pass through the magnetosphere of a planet unimpeded.” But even if the Choice is a swerve, the choices aren’t. Destroy has been Shepard’s mission from day one. Control is set up as an alternate option starting at Mars. And Synthesis is hinted at as The Good Ending by EDI, the Leviathan, and Legion.

And let’s talk about Legion for a minute, and why the Geth/Quarian peace doesn’t affect the conversation with the Catalyst. My first playthrough, I was aghast that silver-tongued Shepard wasn’t able to argue with the Catalyst that none of the options were necessary, that the Geth/Quarian peace proves all three choices are unnecessary, that everything’ll be alright with a little grit and empathy. Shepard’s able to argue (and convince) damn near everyone else in the series of almost anything; it feels like bad writing not to let them do that with the Catalyst, too.

Except for two things. First, Shepard is actively bleeding out. They’re barely conscious when the platform takes them up into the Crucible, not exactly up for a rigorous Lincoln-Douglass debate. But second, and more importantly, the Catalyst is an unreliable actor. The Leviathians’ Intelligence that becomes the Catalyst has one—and only one—purpose: to stop the chaos of organic/synthetic antagonism. The cycle of reaping works for millenia until, finally, a creature actually makes it through the Citadel and onto the precipice of firing the Crucible. That’s never happened before. And more to the point, the Catalyst can’t stop the creature; it has no corporeal form. So the Catalyst has to come up with a new plan: rather than allow the creature to Destroy its solution or, worse, supplant it as the new source of Control, the Catalyst needs to convince the creature to go through with Synthesis. I’m willing to bet the Catalyst would rather just kill Shepard and continue the cycle of reaping, but it knows that that’s no longer possible, so Synthesis is its best remaining option. It has every reason to lie to Shepard, to cajole Shepard into making that choice. It is utterly consistent in its motivations.

In other words, it’s good writing, even if it’s terribly inconsistent with The Good Ending we’ve come to expect.

(As an aside, I know from bad writing: I’m a refugee from Final Fantasy. FFVI was my first—and still my favorite—RPG; FFVII and its followups are brilliant, FFVIII has some of my favorite characters, FFX is a theological treatise better than anything I read in seminary. But FFXIII and especially FFXV are complete and utter garbage. Hollow characters. Unearned conflicts. Absurd twists with no basis in the narrative. A storytelling mode that’s so rigid as to be unbearable. And FFXV’s ending! No pathos, no resolution, the barest connection to anything else in the story, just a huge timejump and then “kill the bad guy.” Uuuuuugh.)

In teasing out the deep grief I felt after beating Mass Effect the first time, I was surprised at the type of grief it is. It’s not the sharp grief of the loss of love, like I felt when my mother-in-law died or when my wife miscarried twice. It’s not the dull grief of the loss of innocence, like when I left home for the last time or when I watched the towers fall on TV. It took a while to process, but I think it’s the grief of the loss of purpose, the same lingering malaise I felt when I finally realized my career of twenty years was actively bad and I had to leave it behind. Mass Effect’s ending is so hard because we want Shepard either to live, or at least to have a “poetic and meaningful” death, and they don’t. They live, they become a mass murderer; they die, they become everything they’ve fought against. That single choice has the effect of making everything before the Crucible feel purposeless.

And yet.

There’s a quote I like from Beckett that goes:

You must go on.

I can’t go on.

I’ll go on.

Art is not always meant to comfort us. Sometimes, it’s meant to break us and then, a la Hemingway, help us become “stronger in the broken places.” Beckett and the absurdists and the existentialists get that on a deep level: there’s always An Ending, rarely is it a Good Ending, and sometimes what you do before and after the ending matters more than the ending itself. And I think that’s where I finally get to with Mass Effect: yeah, the ending is absurd and purposeless. And that’s the point.

I want desperately for Shepard to get The Good Ending because Shepard is the type of person you want to keep alive. I want Mass Effect 3 to end like Mass Effect 1, with Shepard’s companions wondering where they are, and then they run up a piece of debris like a conquering hero for all to see. I want to see my Shepard reunite with Kaidan, to run across the scorched battlefield of London into a fierce embrace and say, “I would never leave you behind, not really, not forever. Not again. Never again.” And he doesn’t. And that sucks.

And there is a deep beauty in fighting until you can’t anymore, in making the only choice you can because it’s still your choice, in finding new purpose after The Good Ending, or The Not-So-Good Ending, because if Mass Effect is about anything it’s about endurance. We will endure this war because we have to. I will endure this pain because I have no choice. Life keeps going because life keeps going with no reason or rhyme so it’s our job to make a reason, to invent purpose where none exists, because that’s what we do.

Existence is absurd. Doubly so in a universe like Mass Effect’s, filled with aliens who wield feckless power and technology that is indecipherable and an enemy who is fundamentally Other. For Beckett, the response to that absurdity is a happy, mighty “fuck you.” Maybe you can get The Good Ending if you try hard enough. Maybe there’s never any such thing as The Good Ending. None of that’s the point anyway because, again, existence is absurd—so fuck you, my life has meaning because I say it does. My choices have meaning because I say they do. We have purpose because we say we do.

As Shepard says, “However insignificant we may be, we will fight. We will sacrifice. And we will find a way. That’s what humans do.”

I’m left conflicted about the next game. A huge part of me—the part that loves the twist in Stranger Than Fiction, the part that’s all about redemption and grace and simplicity—wants the game to be “The Search for Shep.” And I think if it is, it’ll negate the purposelessness and terrible beauty of the ending to Mass Effect 3, which would be an absolute shame. The ending of the Mass Effect trilogy is so powerful because it forces you to find meaning in the journey, not in the ending itself. It turned the whole series on its head for me at least because, honestly, I didn’t really like it during my first playthrough. I mean, it was…fine? Some good characters, some good lines, but kind of a mundane military FPS. Halo with space wizards. But it’s that ending, that existentially absurd ending, that lifts the rest of the series into high literature. (Not that I’m down on fix-it fics, mind you. There’s no work of literature that isn’t elevated by fanfiction. Hell, I’m writing my own fix-it fic from Joker’s POV! I’m just…conflicted about what to do with canon, which is another thing that makes me think it’s good writing after all.)

So that’s where I am. Never thought Mass Effect would jump into my top five favorite games ever, but here we are. It helped me come to terms with some pretty deep feelings I didn’t know were still in me, in the way good literature does. I’ll be chewing on this one for a long, long time. And lucky for me, the state of the fandom ten years after the trilogy ended is so robust that I’m in good company. Got a lot more thoughts, but I’ll stop there. Thanks, friends.

Sometimes, when we lose ourselves in fear and despair, in routine and constancy, in hopelessness and tragedy, we can thank God for Bavarian sugar cookies. And, fortunately, when there aren't any cookies, we can still find reassurance in a familiar hand on our skin, or a kind and loving gesture, or subtle encouragement, or a loving embrace, or an offer of comfort, not to mention hospital gurneys and nose plugs, an uneaten Danish, soft-spoken secrets, and Fender Stratocasters, and maybe the occasional piece of fiction. And we must remember that all these things, the nuances, the anomalies, the subtleties, which we assume only accessorize our days, are effective for a much larger and nobler cause. They are here to save our lives. I know the idea seems strange, but I also know that it just so happens to be true. - Kay Eiffel, The Author, Stranger Than Fiction

#mass effect#mass effect 3#my writing#are you really an English major if you don't substitute writing an essay for therapy#i have so many more thoughts but they'll keep#also reading so much of the fic and essays the ME fandom's done on here helped me piece my brain together#so thanks for that#stranger than fiction

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The island. A last effort. The islet. The shore facing the open sea is jagged with creeks. One could live there, perhaps happy, if life was a possible thing, but nobody lives there. The deep water comes washing into its heart, between high walls of rock. One day nothing will remain of it but two islands, separated by a gulf, narrow at first then wider and wider as the centuries slip by, two islands, two reefs. It is difficult to speak of man, under such conditions.

Samuel Beckett, Malone Dies (trans. Samuel Beckett)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

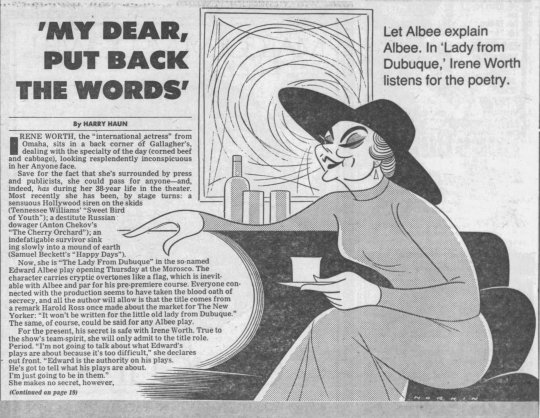

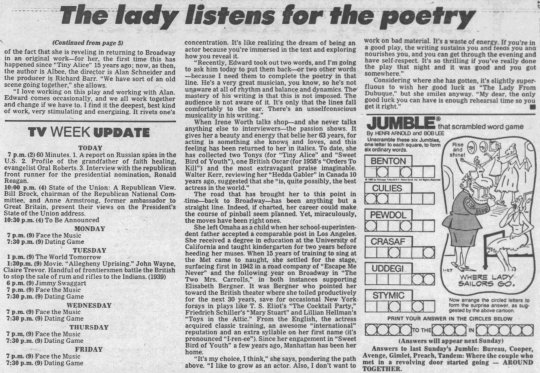

'My Dear, Put Back the Words'

Let Albee explain Albee. In 'Lady from Dubuque,' Irene Worth listens for the poetry.

By Harry Haun

Daily News, January 27, 1980.

Irene Worth, the "international actress" from Omaha, sits in a back corner of Gallagher's, dealing with the specialty of the day (corned beef and cabbage), looking resplendently inconspicuous in her Anyone face.

Save for the fact that she's surrounded by press and publicists, she could pass for anyone and, indeed, has during her 38-year life in the theater. Most recently she has been, by stage turns: a sensuous Hollywood siren on the skids (Tennessee Williams "Sweet Bird of Youth"); a destitute Russian; dowager (Anton Chekov's "The Cherry Orchard"); an indefatigable survivor sinking slowly into a mound of earth (Samuel Beckett's "Happy Days").

Now, she is "The Lady From Dubuque" in the so-named Edward Albee play opening Thursday at the Morosco. The character carries cryptic overtones like a flag, which is inevitable with Albee and par for his pre-premiere course. Everyone con nected with the production seems to have taken the blood oath of secrecy, and all the author will allow is that the title comes from a remark Harold Ross once made about the market for The New Yorker: "It won't be written for the little old lady from Dubuque." The same, of course, could be said for any Albee play.

For the present, his secret is safe with Irene Worth. True to the show's team-spirit, she will only admit to the title role. Period. "I'm not going to talk about what Edward's plays are about because it's too difficult," she declares out front. "Edward is the authority on his plays. He's got to tell what his plays are about. I'm just going to be in them." She makes no secret, however, of the fact that she is reveling in returning to Broadway in an original work—for her, the first time this has happened since "Tiny Alice" 15 years ago; now, as then, the author is Albee, the director is Alan Schneider and the producer is Richard Barr. "We have sort of an old scene going together," she allows.

"I love working on this play and working with Alan. Edward comes occasionally, and we all work together and change if we have to. I find it the deepest, best kind of work, very stimulating and energizing. It rivets one's concentration. It's like realizing the dream of being an actor because you're immersed in the text and exploring how you reveal it.

"Recently, Edward took out two words, and I'm going to ask him today to put them back—or two other words—because I need them to complete the poetry in that line. He's a very great musician, you know, so he's not unaware at all of rhythm and balance and dynamics. The mastery of his writing is that this is not imposed. The audience is not aware of it. It's only that the lines fall comfortably to the ear. There's an unselfconscious musicality in his writing."

When Irene Worth talks shop—and she never talks anything else to interviewers—the passion shows. It gives her a beauty and energy that belie her 63 years, for acting is something she knows, and loves, and this feeling has been returned to her in italics. To date, she has collected two Tonys (for "Tiny Alice" and "Sweet Bird of Youth"), one British Oscar (for 1958's "Orders To Kill") and the most extravagant praise imaginable. Walter Kerr, reviewing her "Hedda Gabler" In Canada 10 years ago, suggested that she "is, quite possibly, the best actress in the world." The road that has brought her to this point in time back to Broadway has been anything but a straight line. Indeed, if charted, her career could make, the course of pinball seem planned. Yet, miraculously, the moves have been right ones. She left Omaha as a child when her school-superintendent father accepted a comparable post in Los Angeles. She received a degree in education at the University of California and taught kindergarten for two years before heeding her muses. When 15 years of training to sing at the Met came to naught, she settled for the stage, surfacing first in 1942 in a road company of "Escape Me Never" and the following year on Broadway in "The Two Mrs. Carrolls," in both instances supporting Elisabeth Bergner. It was Bergner who pointed her toward the British theater where she toiled productively for the next 30 years, save for occasional New York forays in plays like T. S. Eliot's "The Cocktail Party," Friedrich Schiller's "Mary Stuart" and Lillian Hellman's "Toys in the Attic." From the English, the actress acquired classic training, an awesome "international" reputation and an extra syllable on her first name (it's pronounced "I-ren-ee"). Since her engagement in "Sweet Bird of Youth" a few years ago, Manhattan has been her home.

"It's my choice, I think," she says, pondering the path above. "I like to grow as an actor. Also, I don't want to work on bad material. It's a waste of energy. If you're in a good play, the writing sustains you and ieeds you ana nourishes you, and you can get through the evening and have self-respect It's so thrilling if you've really done the play that night and it was good and you got somewhere."

Considering where she has gotten, it's slightly superfluous to wish her good luck as "The Lady From Dubuque," but she smiles anyway. "My dear, the only good luck you can have is enough rehearsal time so you get it right."

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

For Michael Shannon, Waiting for Godot Is the Ultimate Opportunity

By Jake Nevins

Photographed by Travis Emery Hackett

November 21, 2023

The actor Michael Shannon, photographed by Travis Emery Hackett

Earlier this year, when I interviewed the actor Paul Sparks, who was then playing Henry in The Grey House, he revealed to me, a bit sooner than his publicists would have liked, that his next project was a production of Waiting for Godot at the Theater for a New Audience. The only actor, Sparks said, with whom he could imagine tackling the dense, despairing, and singularly precise words of Samuel Beckett was his good friend Michael Shannon. So, last week, nearly a decade after Sparks and Shannon starred in the theater’s 2014 staging of Eugène Ionesco’s The Killer, they began their run as Vladimir and Estragon, respectively, appearing here as a pair of wretched jesters in bowler hats. Director Arin Arbus has conceived of Beckett’s “country road” as a jet-black runway, making especially pronounced the characters’ experience of life as a punishing, empty void (“Let’s hang ourselves immediately,” Estragon suggests). But the actors, demonstrating an easy physical chemistry, fill it admirably, as Shannon synchronizes his brooding Gogo with Sparks’s Chaplinesque interpretation of Didi.

“It’s a monumental undertaking,” Shannon said the day after their opening show from a backroom of the theater. “Estragon is a state of mind that exists in all of us,” he continued, “or can exist in us if we’re overcome by it.” Shannon seemed, if not overcome by the play, at least deeply occupied by its notions of humanity. And while Beckett’s text commands a great deal of discipline and fidelity, he and Sparks were still plumbing its depths, finding new questions to ponder and play with. “The play,” he explained, “is an opportunity to go somewhere that doesn’t exist unless we’re doing it.”

———

MICHAEL SHANNON: Hi.

JAKE NEVINS: How’s it going?

SHANNON: Oh, you know.

NEVINS: I had the pleasure of seeing the show last night. Congratulations on such a fresh production of something that’s hard to make fresh.

SHANNON: Oh, yeah? Have you seen it before?

NEVINS: Only a high school production, and not with actors as formidable as you and Paul.

SHANNON: Thanks.

NEVINS: I’m curious what your prior encounters were with Waiting for Godot and Beckett’s work in general.

SHANNON: Well, I first saw Waiting for Godot when I was a kid. I think I was 11 or 12 and I saw it in a production that was outdoors, outside of a school actually, where the playground was, and it made a huge impression on me. I think it is probably one of the things that’s responsible for me getting into the theater in the first place. And I’ve seen Happy Days with Fiona Shaw at BAM [The Brooklyn Academy of Music], which I really loved. And I saw a production of Endgame at Steppenwolf, which I really loved. I’ve done a lot of Ionesco over the years and he’s kind of my favorite playwright, but I had never actually done a Beckett play myself. The way it came to be was kind of random, really. I was just sitting and talking with Jeffrey Horowitz, who runs the theater, and we were brainstorming about possible productions to put together and it just popped into my head, the idea of doing it with Paul, specifically.

NEVINS: I imagine the language, specifically all that philosophical slapstick, might be quite daunting.

SHANNON: Well, it’s a monumental undertaking. It’s not something that you can just follow simple instructions for. But, like most great plays, it really draws you back to your own life and your own situation. It’s very universal, I think. I think if you are willing to look at it and willing to be patient with it, it can reveal a lot to you about how you navigate your own life and navigate the world. And, frankly, I’ve just felt a lot of kinship with Estragon in terms of some of my own trials and tribulations of late. So it’s almost like you’re not really creating a person that’s separate from you. Estragon is a state of mind that exists in all of us, or can exist in us if we’re overcome by it. It’s different from other plays in that regard.

NEVINS: I appreciate that distinction and the way you both approached the characters. Paul, of course, plays Vladimir with a sort of playfulness, highly gestural and expressive. What’s it like to play opposite Vladimir as Paul has conceived of him?

SHANNON: Well, Paul is always giving so much of himself. He’s such a generous performer and he’s so playful and creative and intelligent in his work and it’s thrilling to fill the space that he creates. A lot of times I refer to it as a negative, like I’m the space around the light that he’s inhabiting and creating, like I’m the darkness. We both feel like there’s still so much to learn as we do the show. We don’t feel like we’ve figured it out or that we’re done and we can just do what we made up in rehearsal. We don’t want to just repeat something night after night. Now, it’s also a very deceptively precise show, so there is some discipline involved in terms of the rhythm of it. The music of it is very precise, but within those parameters, I feel like we both are still searching pretty fervently.

Vladimir and Estragon is that they entertain each other. That’s the substance of their friendship, that they’re able to keep each other occupied. And I think Estragon thinks that Vladimir is funny and that is something he desperately needs in order for him to keep on keeping on, as they say.

NEVINS: That’s interesting, because humor in the play serves that very same function for the audience, somewhat alleviating their sense of entrapment. Their kinship with one another makes you want to stick with something that might otherwise feel kind of punishing.

SHANNON: We really don’t intend to bum anybody out. I guess I’ve heard people talk about productions of this play that were, I don’t know, a little less buoyant than ours, I suppose. I think I even read a review that said they get the humor part, but they didn’t get the dark stuff right, or something.

NEVINS: A review of this production?

SHANNON: Of this production, yeah. I don’t know how to make dark stuff dark. It’s already dark.

NEVINS: Right.

SHANNON: The play is an opportunity. It’s an opportunity to go somewhere that doesn’t exist unless we’re doing it. And we want to welcome people into it. We don’t want to alienate people. We want people to hear it. We want people to hear the play because there’s nothing that’s in the room that’s going on that is as important as the actual play. The play is the star, and we’re just trying to deliver it in a way where you can hear it and feel it. We don’t want to put up walls, or make it seem inaccessible. The way it’s directed and designed is all about trying to make it feel intimate and trying to make it feel like you’re involved as an audience member. It’s not a proscenium. You’re not all sitting in the dark.

NEVINS: To your point, I quite liked the staging of it. The runway you two are on has a sprawl to it, as if that road could go on and on. But it doesn’t come at the cost of intimacy.

SHANNON: Thank you.

NEVINS: Are there other plays, canonical or otherwise, that you’re jonesing to do?

SHANNON: Not at this moment. Kind of like how I said earlier, this just kind of popped into my head. I’m pretty spontaneous about things. I don’t have a list at home of the things I want to do. Things just occur to me or present themselves to me and then I do them. But this theater is known for Shakespeare, and Jeffrey’s talked to me about doing Shakespeare, so maybe that’s on the horizon. But I wouldn’t even know which play. I get so focused on whatever it is that I’m doing that I forget about the future.

NEVINS: It shows. Congratulations. And thanks for your time.

SHANNON: My pleasure. Thank you.

0 notes

Photo

For several months I’ve had the privilege of working with Ms. @kaylaboye, who ever impresses me, to hand craft this full-bellied seminal piece, while balancing other projects, shifting dates, venues, team, etc. But we’re now at that time when we must unlock the doors & share it with our community. (More details & info to follow) From one of the most influential writers of the 20th century, we open Samuel Beckett’s “Happy Days,” with Kayla Boye, designed & directed by me. (Link in bio) #announcement #SamuelBeckett #HappyDaysChi #Chicago #ChicagoTheatre #KaylaBoye #JonDambacher #openingsoon (at City Lit Theater) https://www.instagram.com/p/CpTEfAAOGSx/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

3 notes

·

View notes