#hairy larva

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A Hairy Moth Caterpillar. The bristles/ hair on the body of this caterpillar are so many and so long, that they would be enough to cover another caterpillar. The main body of this caterpillar remains hidden under hair. And you can also notice water droplets accumulated in hair, it looks so beautiful.

#moth caterpillar#moths#caterpillars#moth larva#larva#hairy moth caterpillar#hairy larva#hair#bristles#insect#insects#insects of india#insects of western ghats#biodiversity of western ghats#photography#water droplets#droplets

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

♡︎ Hairy luna moth caterpillar ☾

긴꼬리산누에나방 (Actias artemis)

#photographers on tumblr#my photography#original photographers#art#lensblr#photography#animal photography#insect photography#wildlife photography#macro photography#nature photography#nature#wildlife#naturecore#insect#moth#moths#moon moth#larvae#luna moth#larva#caterpillar#caterpillars#crawlers#bugblr#entomology#hairy crawler#so cute#may 28 2024#noai

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grub-Dogs, for fun

58 notes

·

View notes

Video

tumblr

Wow, I got footage of a hairy woodpecker wresting an insect larva out of a tree and then whacking the crap out of it 😮

#backyard birds#birds#birdlr#birblr#woodpecker#hairy woodpecker#bird#nature#OBAB Photography#I was really lucky with this shot#I heard some knocking on the tree while I was doing yardwork and I happened to have my camera nearby#then I recorded this video and soon afterward the woodpecker flew away with its meal#I didn't know such large larva live in the tree 🤯

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round 3 - Reptilia - Cuculiformes

(Sources - 1, 2, 3, 4)

Our next order of birds are the Cuculiformes, commonly called “cuckoos”. Cuculiformes contains one living family, Cuculidae, and 33 genera.

Cuckoos are generally medium-sized, slender, intelligent birds. Most live in trees, though some are primarily ground-dwelling. They feed on insects, insect larvae, and a variety of other animals, as well as fruit. Their feet are zygodactyl, meaning that the two inner toes point forward and the two outer backward. Arboreal species tend to be more slender have short tarsi, while terrestrial species are more heavy set and have longer tarsi for running. Almost all cuckoos have long tales that are used for steering during either flying or running. Some species have cryptic plumage, while others have bright, elaborate, or iridescent plumage. They live all over the world’s continents except Antarctica, in habitats ranging from rainforest to desert. Some are migratory.

Most cuckoos are monogamous, though exceptions exist. Cuckoos are usually solitary, and only some species can be found in pairs or groups. However, during the breeding season a pair will spend time together, sometimes bringing each other gifts of insects or fruit. Some species of cuckoo are brood parasites. Brood parasites will lay their eggs in the nests of other birds, in some cases while the male distracts the host parents. Their eggs sometimes look similar to the eggs of their chosen hosts, though they usually have thicker and stronger shells. This protects the egg if a host parent tries to damage it. The cuckoo egg hatches earlier than the host eggs, and the cuckoo chick grows faster; in most cases, the chick instinctively evicts the eggs and/or young of the host species. In some species the cuckoo chick does not harm the other eggs or chicks intentionally, but will outcompete them for food. However, the majority of cuckoo species are not brood parasites, and their nests vary in shape from shallow platforms of twigs, to globular or domed nests of grasses, to saucers or bowls on the ground, to simply being laid directly on the ground. Non-parasitic species lay white eggs, and both male and female are usually involved in care of the eggs and chick. The young of all species are altricial, born weak and featherless, though non-parasitic cuckoos leave the nest before they can fly.

Cuculiformes are part of the clade Otidimorphae, which also includes the Musophagiformes (turacos) and Otidiformes (bustards). Otidimorphs arose in the Eocene, around 34 million years ago. One of the oldest known cuckoos is Dynamopterus velox from the Oligocene.

Propaganda under the cut:

While most species of cuckoo are solitary and secretive, the Anis (genus Crotophaga) (image 4) tend to be the exception to this rule. They live and nest communally, with a large nest being built by several pairs in which a number of females lay their eggs and then share incubation, feeding, and territorial defense duties. They also tend to be extremely trusting and friendly towards humans and other species.

Many cuckoos will eat the noxious, hairy caterpillars avoided by other birds. They can do this by rubbing the caterpillar back and forth on a branch to rub off their venomous hairs, and then crushing it with special bony plates in the back of their mouth.

The smallest cuckoo is the Little Bronze Cuckoo (Chalcites minutillus) which is 15-16 cm (5.9-6.3 in) long and weighs 14.5-17 grams (0.51-0.60 oz). It feeds on insects and while it usually hunts alone, it has often been seen hunting in groups of up to 5 birds.

Meanwhile, the Channel-billed Cuckoo (Scythrops novaehollandiae) is the largest living cuckoo, at 56–70 cm (22–28 in) long, with a 88–107 cm (35–42 in) wingspan, and weighing between 560–935 g (1.2–2 lb). The Channel-billed Cuckoo is a brood parasite, and also the largest brood parasite in the world. They parasitize the nests of larger Australian birds, such as ravens (genus Corvus), currawongs (genus Strepera), and butcherbirds (family Artamidae).

The fastest cuckoos are the Roadrunners (genus Geococcyx) (see gif above), which have been recorded running at 32 km/h (20 mph).

The Black Coucal (Centropus grillii) is unique among cuckoos for being polyandrous, with males tending to the nests while the larger female patrols the territory. A female’s territory can contain several nests with a different male at each nest, and males will often adopt the eggs and chicks of other males.

Cuckoos are a heavily present symbol in many human cultures. In Ancient Greek mythology, the god Zeus transformed himself into a cuckoo so that he could seduce the goddess Hera, to whom the bird was sacred (women in Ancient Greek mythology were frequently attracted to birds.) Three sacred cuckoos appear in the Finnish epic the Kalevala, connected to the death of a young girl who was being forced into marriage. In India, cuckoos are sacred to Kamadeva, the god of desire and longing, whereas in Japan, the cuckoo symbolises unrequited love. Cuckoos are a sacred animal to the Bon religion of Tibet. In Germany, a cuckoo clock is a classic pendulum-driven clock that mimics the call of a Common Cuckoo (Cuculus canorus) (image 2), complete with an automated cuckoo bird that moves with each note. Additionally, the brood parasitism of some cuckoo species gave rise to the term "cuckold", referring to the husband of an adulterous wife.

210 notes

·

View notes

Note

My boyfriend told me recently that barnacles have like, teeth??? They have tentacle teeth that eat fish & thats why they’re dangerous. What the fuck!?

I wish there were badass fish eating barnacles but no they really only have a little round hole for a mouth, deep inside the shell, and the hairy "tentacles" that pop out are the legs, which catch plankton from the water. A lot of plankton consists of tiny animals so they do end up eating meat of course, in fact some of the most common of all plankton in the sea are barnacle larvae, so they're always idly eating each other's babies.

There is a barnacle that grows as a parasite on small deep sea sharks though. Barnacles on other vertebrates, like whales or turtles, aren't parasitic at all and just riding around. But this one feeds on the shark and even castrates it, which is something many parasites do just so their host doesn't divert too many nutrients into having babies. I think this is the only case on which any parasite does this to something with a spinal cord.

image D here shows a non-parasitic barnacle in the same family for comparison, the parasitic one even lost its normal filter feeding system and draws sustenance through "roots!" Sometimes a crustacean wants to be a tree.

270 notes

·

View notes

Text

In a land of plentiful fluids, there is a great variety of life that thrive within them! Be it water, bile or blood, these fluid bodies are always a host to an incredible array of aquatic creatures!

1. Silt Snorter - A large bottom feeding fish with two mouths and iconic whiskers. They spend their lives down near the silt and muck, using their twin mouths to suck it up and filter food through their hairy gills. Their long whiskers help them keep their bearings when the silt is disturbed and the fluid is clouded. Growing to giant sizes, they are prized trophy fish, but not so great for eating. Their flesh is tainted by their mucky diet, but with the sheer quantity you can get from a single catch, no one wants to waste it, thus folk have developed recipes to help mask the flavor. Also a good source of sea snot.

2. Nailbiter - A keratin clad fish with a dexterous maw. They specialize in pulling prey from nooks and crevices, using their oral fingers to reach in and drag them out. With no actual biting or shearing teeth, they can only eat what can be swallowed whole. Their armored scales are tough but light, allowing them protection while not weighing them down. They are caught for their "fish fingers," a dish made from their oral digits. Legends like to say this fish came to be from a greedy fisherman who reached into the water for one too many fish and had the offending hand taken to replace what he stole.

3. Sperm Eel - An odd boneless fish known for its strange reproductive habits and milky nature. They live in riverside burrows, feeding on small invertebrates and floating bits. The species lives only long enough to reproduce once, as the viable adults congregate up river. When the time comes, these breeding fish straight up disintegrate into reproductive fluids, with the males becoming a cloud of sperm and the females a cloud of tiny eggs. Entire floats of white frothy egg masses form from this breeding session, creating thousands of larvae. This season can clog rivers with these rafts, but it is a bountiful moment for other species that come to feed. When it comes to fishing them, they must be caught and kept alive, as their bodies melt upon death. Though there is no meat to gain, they are used as a soup thickener and add a delightfully milky and salty flavor to a dish.

4. Syringefish - A parasitic fish of the rivers that targets larger piscines or wading beasts. Their single tooth is hollow and built for sucking Blood from prey. Typically look for sluggish fish to feed on, or disturbances from animals swimming. Will ram themselves into whatever flesh they can find and drink as much as they are able. Their stomachs can swell up to fit their meal, growing until they are practically sphere shaped. A pest to any who have to deal with them when wading through the river or trying to catch fish that don't have puncture wounds all over. At least good for a nice bloody snack for those who catch engorged ones.

5. Scabfish - Crimson in color and crusty in texture, they typically appear in bloody waters or in scarred regions. They rest upon the floor of the fluid body, waiting for prey to pass close for an ambush. Their rough scabby skin makes them unappealing to some predators, and make them quite abrasive to handle. Some seafolk may use their dried skin for sanding wood and ivory. Can also be used to make scab crackling.

6. Urolith Fish - A jagged fish that prefers to rest on the bottom rather than swim, using its wide fins to crawl in a way. Typically hides in tight spaces and uses ambush tactics to swallow prey. They are infamous for their spiny bodies. with nasty spikes that break off agonizing shards into those who touch them. Once inside the flesh, they are difficult to remove and are prone to breaking into smaller pieces. These fish serve as a reminder to watch your step when wading through the shallows. To be avoided and not eaten, as their meat reeks of urea. Some shady folk have found their spines good as debilitating knives, stabbed into victims to paralyze them with pain.

7. Mantinia - A colorful creature of chitin that slices through the water with its razor body. Its frontal appendage is designed for lashing out with blinding speed and snaring slippery prey in its barbed grasp. It lacks a true mouth, and instead uses its hollow spines on this "arm" to suck fluids from its prey. Its vivid coloration is believed to be used to win over mates. Despised by fisherman for stealing catches, cutting lines and shredding nets. Legends say that this fish came to life when a warrior surrendered his colorful chitin blade and gave it to the water.

8. Skullcracker - A powerful bulky fish known for its bony forehead and cracking teeth. They feed primarily on ivory corals and other hard-bodied prey, using a mouthful of broad teeth to shatter shells and armor. Their bulging forehead is solid and makes for a good weapon against predators and rivals. They make for dangerous catches, as they may ram the boat with their head or jump from the waters at inopportune times to concuss the unwary fisherman. They have gained this name for a reason.

9. Snot Shroud - A tiny fish that is capable of producing an incredible amount of Phlegm, they use it to surround their body in a false mass. This mucus sheath acts as a fake body and shield, allowing them to ward away parasites and survive predation. This sticky mass also collects food particles and tiny prey for the fish to feed upon. A potent producer of sea snot, and typically kept alive by seafolk on ships to churn out this marine Phlegm for medical purposes.

10. Searfish - A parasitic fish that possesses Yellow Bile and a nasty suction cup on its head. This structure is made to latch onto the sides of larger fish, where it then pumps the burning humor to melt through scale and flesh. The porous surface of this sucker allows it to absorb nutrients from its host, feeding on fluids and digested flesh. Typically target leviathans as their vast size allows them to shrug off these wounds. Circular scorch marks are the scars they leave behind, and some fisherman have found them on the bottom of their boats. If not deterred, they can scorch straight through the floor of a small canoe or boat, thus fisherman take steps to keep the burning buggers away.

11. False Floater - A seemingly rotting fish that plays a deceptive game. Their belly-up posture and patchy skin makes them look quite dead, but this fish is alive and well. A gas filled bladder suspends them in the water, while perfect stillness lures in scavengers. A multi-part jaw filled with needle teeth snares prey that comes to feed on this supposed corpse. Though they are not actually rotting, their meat is very pungent and slimy, thus is avoided when it comes to eating. Their dead appearance does lead to them being associated with the Mother of Snow.

12. Spiretail - A creature instantly recognizable due to their preference of hanging vertically and upside down in the water. They often hover just above the bottom, feeding on the small bits and critters that pass by. Sharp shards of Black Bile jut from their bodies, warding off predators. Often hang out in groups, gaining more protection through numbers. A bane to swimmers who accidentally swim through these schools, as such encounters guarantee several lacerations.

13. Cysthorse - A diseased looking fish that is actually filled with a burning toxin. Attempts to eat or touch them will result in these noxious boils to rupture and seep out this vile poison. Flesh that comes in contact with this fluid often winds up looking like the fish's unsightly skin. Avoided when it comes to fishing as one snared in a net may ruin both the net and the catch with its boiling fluids. Plus, they are associated with sickness, thus their appearance is an omen for future afflictions upon the catcher.

14. Sawtooth - A vicious fish with a killer overbite, they use their protruding blade of teeth to wound and shred prey. Appear to be solitary and not fans of their own kind, judging from the scars their hide often bears. They are a prized catch of any fisherman, though bringing them in without losing the line or a limb is difficult. Their upper jaws are often saved as trophies and turned into tools or weapons.

--------------------------------------------

Recently got and completed the fishing game Dredge and was inspired by it. So the obvious choice was to fill the fluid bodies of FOI with some fishies!

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bloody-Nosed Beetle (Timarcha tenebricosa)

Family: Leaf Beetle Family (Chrysomelidae)

IUCN Conservation Status: Unassessed

Also known as the Blood-Spewing Beetle, the Bloody-Nosed Beetle is a large, wingless, herbivorous species of beetle named for its unusual defensive adaptations: when threatened, members of this species secrete a thick, blood-red liquid from their mouths, giving the impression that they are experiencing a heavy nosebleed. The “blood” secreted by Bloody-Nosed Beetles is actually haemolypmh (a typically transparent bodily fluid found in the circulatory system of most arthropods which serves the role of both the blood and lymph of vertebrates) which contains both haemoglobin (giving it its striking red colour and allowing for more efficient oxygen transportation while in the body) and numerous foul-tasting chemicals that make the beetle unpalatable to most animals, deterring the majority of predators and causing hesitation even in those that are not deterred by the taste. Fairly common in grasslands, heathlands and other densely-vegetated habitats across much of Europe, adults of this species are slow-moving and active mainly at night, using their strong, hook-tipped legs to climb through dense vegetation and relying on their long, segmented antennae to aid them in finding bedstraws (small, often hairy plants in the genus Galium,) which they feed on exclusively. Adults lay their eggs on or near bedstraws to ensure their offspring have access to food after hatching, and while they are unable to survive the low temperatures of their range’s winter their larvae (which are jet-black with short antennae and rotund, wrinkly-looking bodies) burrow underground to pupate as the temperatures get lower, emerging as adults in the following spring.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Image Source: https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/118838-Timarcha-tenebricosa

#bloody-nosed beetle#beetle#beetles#zoology#biology#entomology#animal#animals#insect#insects#arthropods#arthropod#European wildlife#invertebrates#wildlife

280 notes

·

View notes

Text

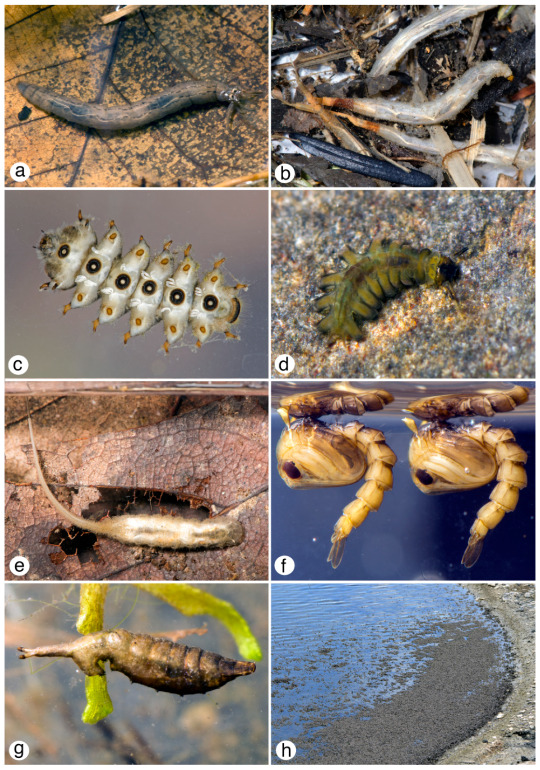

Wet Beast Wednesday: aquatic insect larvae

This Wet Beast Wednesday is going to be different than usual. Instead of an in-depth overview of a specific species or group of species, I'm going to give a general overview of aquatic insect larvae as a whole and then showcase some groups of insects. I'm going to focus on insects that have an aquatic larval stage and terrestrial adult stage, saving adult aquatic insects for another post.

(Image ID: a group of mosquito larvae. They are yellowish bugs with long, slender bodies, no visible limbs, small heads, and feathery appendages from their rear ends. From the back of the abdomen, a snorkel-like appeadage attaches to the surface of the water, using surface tension to allow the larvae to hang from the surface. End ID)

Insects are basically the most successful group of animals in the history of life on Earth and have adapted to live in just about every terrestrial habitat. It should not be much of a surprise than that they have also moved into the water. More specifically, fresh water as almost all aquatic insects inhabit fresh or maybe brackish water. Only the water strider genus Halobates are truly marine. Some species of insect are aquatic for their entire lives, some are primarily terrestrial but able to swim, and some are aquatic only for their larval stage of life. These aquatic larvae species are generally agreed to have evolved from fully terrestrial ancestors. The adaptation of partially returning to the water has evolved independently many times in many different clades of insect and so different species use different strategies and adaptations. It is possible that aquatic larvae evolved in response to high competition for resources on land. If multiple species are competing over the same resources during their larval stages but one of those species manages to adapt to a whole new environment, that species will now have abundant access to resources the other species are unable to get to. Because of the very different lifestyles required for aquatic and terrestrial animals, aquatic larvae often look very different than their adult forms.

(Image: an aquatic beetle larva. It looks nothing like an adult beetle, instead being a long, slender insect with no wings, multiple body segments, and two hairy appendages at the base of the abdomen. End ID)

Aquatic larvae serve important roles in their ecosystems. Many are herbivores or detritivores that consume algae and bits of biological material, helping recycle nutrients and clean the water. Some are predators that hunt smaller invertebrates or plankton. Importantly, aquatic insect larvae provide a major food source for larger fish, invertebrates, birds, and so on. Some species can be considered keystone species, vital to their ecosystems. Many species are highly sensitive to changes in their environment, allowing them to act as indicator species for the health of their ecosystems. The trio of mayflies, stoneflies, and caddisflies are very commonly used as indicators of pollution as all three are highly sensitive to pollutants. A stream with few mayflies, stoneflies, or caddisflies but plenty of less sensitive species is likely to be polluted.

(Image ID: a collage of aquatic larvae of multiple species in the order Diptera (true flies. They vary from slug-like to having multiple distinct body segments with legs, to looking like maggots with long tails. End ID. Source)

Mayflies (order Ephemeroptera) are among the oldest lineages of winged insects, bearing traits that they first flying insect also had. Juvenile mayflies are technically not larvae, but nymphs. The difference between a larva and a nymph is that nymphs look much more like the adult stage than larvae do. Mayfly nymphs lack the wings of adults, but have external gills growing from the sides of their abdomens. Mayfly nymphs can be identified by three appendages called cerci that emerge from the back of the abdomen. They are bottom-dwellers that typically live under rocks and other objects or amid plants. Most are herbivores, feeding mainly on algae. Months to years after hatching (species dependent), mayflies will float to the surface and go through a molt to a stage called the subimago. Uniquely among insects, mayflies go through two final winged molts. The first is to a not sexually mature stage called the subimago, then they quickly molt again into a fully mature imago stage. These molts happen in sync, resulting in hundreds to thousands of mayflies appearing all at once and swarming together to mate. Famously, adult mayflies exist only to mate and die. Their digestive systems are non-functional and few species last past a few days.

(Image: a mayfly nymph on a rock. It is a yellow bug with no wings, a long abdomen, and thick, grasping legs. Three long, hairy cerci emerge from the back. Along the side of the abdomen are multiple pairs of white, feathery gills. End ID)

Stoneflies (order Plecoptera) also have nymphs and can be quite difficult to tell apart from mayfly nymphs if you don't know what to look for. One of the biggest differences is that their gills are located by the base of the legs rather than along the abdomen. Like mayflies, stoneflies are some of the most primitive winged insects, but mayflies are Paleopterans (the earliest wings insects) while stoneflies and most other winged insects are Neopterans. The main difference is that Neopterans can flex their wings over their abdomens while Paleopterans cannot, and must hold their wings either out to the side or up in the air. Like with Mayflies, many adult stoneflies have nonfunctional digestive systems and exist only to mate and die.

(Image: a stonefly larva. It looks similar to a mayfly larva, but has a shorter abdomen, gills along the base of the legs, and only two cerci. End ID)

Caddisflies (order tricoptera) are the builders of the aquatic insect world. These larvae (most species anyway) can produce silk from glands near their mouths. These are used to make a variety of structures made from silk and various other materials including sand, silt, plant parts, shells, rock, and so on. Different species will seek out specific materials for their structures. There are a few types of structures, the most common of which is a tubular case that is open at both ends. The larva can carry the case with it as it crawls around and can retreat into the case for protection. The larva can draw water into one end of the case and out the other, allowing oxygenated water to flow over the gills. By moving around in the case, the larva can draw in more water. This allows the larvae to survive in water that is too oxygen-poor for other larvae. Other species build different structures including turtle-shell like domes or stationary retreats. My favorite structures are nets built with an open end into current. The current naturally brings detritus and micro-invertebrates into the net, where the larva can eat them. Caddisflies also pupate into pupa that have mandibles to cut their way out of their cases and swimming legs. Once developed, the pupae swim to the surface and molt into their adult forms. This molting is synchronized to ensure the adults emerge in swarms and can easily find mates.

(Image ID: a caddisfly larva in its case. The case is a tube composed of pebbles of different colors stuck together with silk. The head and legs of the larva are merging from the front of the case. End ID)

(Image: a caddisfly net. It is a structure made of silk shaped like a tube that is wide at one end and tapers toward the other. It is curved so both ends face the same way. End ID)

The order Megaloptera consists of alderflies, dobsonflies, and fishflies. All three have aquatic larvae, but their eggs are laid on land. Most species lad their eggs on plants overhanging the water so the larvae fall in once hatched, though a few lay eggs near the water's edge, forcing the larvae to crawl in. Meglaoptera have the least amount of differences between larva and adult of all holometabolous (pupa-forming) insects. The largest differences between the larvae and adults is the larvae lack wings and some species have leg-like prolegs. All species are carnivorous as larvae and feed on other invertebrates.

The adults don't look any less creepy

(Image: two hellgrammites, the larval form of a dobsonfly. It looks somewhat like a centipede with three pairs of limbs and a long abdomen with multiple pairs of leg-like prolegs. The head has no visible antennae, but does have a pair of powerful pincers. End ID)

Order Odonata consists of dragonflies and damselflies. These are powerful predators both as nymphs and adults. As nymphs, the juveniles are shorter and stockier than the adults, with no wings. The nymphs (or naiads) breathe through gills. In damselflies, these gills can be external, but dragonfly nymphs have their gills located in the anus. Damselflies can swim by undulating their gills, but dragonfly nymphs are restricted to crawling. The nymphs are voracious predators that will feed on anything they can catch. Most of their diet consists of invertebrates, but they will also attack small fish, tadpoles, and even salamanders.

(Image ID: a dragonfly larva on a rock. Its head is similar to that of the adults, but the abdomen is much shorter and broader and the legs are longer. It has no wings and is brown all over. End ID)

The groups of insects I covered today (plus the stoneflies) all have exclusively or near-exclusively have aquatic larvae while the adults are terrestrial. In other groups, aquatic larvae may be present in some species while others have terrestrial larvae. For example, a great many members of the order Diptera (true flies) have aquatic larvae including all mosquitos, while other members of the order have fully terrestrial larvae. In addition there are species of beetle (order Coleoptera), moth (order Lepidoptera), lacewing (order Neuroptera), and scorpionflies (order Mecoptera) that have aquatic larvae and some species of the true bugs (order Hemiptera) have aquatic larvae and aquatic adults, including water skaters, water scorpions, and giant water bugs. Aquatic insects are so prevalent that it is rare to find any lasting body of water that doesn't host some aquatic larvae or adults. Even incredibly stagnant and filthy water can host aquatic insect larvae, as shown by the notorious rat-tailed maggots, who love stagnant water and breathe through snorkels. Many species require very specific conditions and there are species of insect who exclusively grow their larvae in specific streams or lakes. Because of this, conservation of these bodies of water is vital to their survival and pollution, damming, and other factors can destroy whole species.

(Image: an aquatic moth larva. It looks very similar to a green land caterpillar, with none of the fancy elements many land species have. It is translucent and wrapped around some aquatic plant stems. End ID)

#wet beast wednesday#insects#insect larvae#aquatic insect larvae#larva#pupa#mayfly#stonefly#caddisfly#dobsonfly#hellgrammite#dragonfly#damselfly#freshwater ecology#ecology#biology#zoology#invertebrate#invertebrates#animal facts#informative#bug#bugs

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

The PNF-404 Phylogenetic Tree

A bit of a different post from the usual, as I have been very hyped for Pikmin 4! Here's my speculative phylogenetic tree for most of the creatures in the Pikmin series. It is a bit more cautious than an actual phylogenetic tree, so there are a lot of soft polytomies (ideally every branch split should only have two children), but I digress.

Edit

It seems that Tumblr's compression did some nasty work on my post, so I'm gonna leave here a link to my phylogenetic tree in case anyone would like to see it in its full glory.

Here are also all the notes on the image in case anyone needs those too:

Author's Notes

Updated as of the Pikmin 4 Demo.

Icons taken from the Pikipedia and Pikmin games.

Fonts used are “Pikmin Font” by TheAdorableOshawott and “Dimbo” by Jayvee Enaguas.

Species with multiple scientific names

The Red Bulborb, Empress Bulblax and Bulborb Larvae are all explicitly different forms of the same species, as is the case in their Japanese technical name.

The Spotty Bulbear and Dwarf Bulbear are both explicitly different forms of the same species, as is the case in their Japanese technical name.

The Baldy Long Legs and Hairy Long Legs are explicitly stated to be the same species.

The Centipare and adult Centipare have completely different scientific name and family.

Incorrect scientific name (according to Japanese family name)

Despite being in the Breadbug family, the Fiery Dwarf Bulblax, has the Oculus genus instead of Pansarus. This is corrected here.

Despite not being in the Blowhog family, the Tusked Blowhog shares its Sus genus.

Despite not being in the Mandiblards family, the Shooting Spiner shares its Himeagea genus.

Despite not being in the Flint Beetle family, the Glint Beetle shares its Pilli genus.

The Floaterbie family is supposed to be the same family as the Flutterbie family in the original Japanese.

The Crysanthemum family is considered the same as the Dandelion family in the original Japanese.

Changes due to assumed consistency

All Wollyhop names have been updated to match the Wolpole's European name, which was standardized in Pikmin 4.

Similarly, All mentions of the “frodendum" specific name have been updated to match Wolpole's frondiferorum name in Pikmin 4.

The Red Spectralid has a different genus (Fenestrati) than every other Spectralid. This is likely a mistake is corrected here.

Despite not all Candypop Buds being present in the Pikmin 4 Demo, it is assumed they are all now considered the same species in the Piklopedia.

Scientific name in the wrong order

The Fiery Young Yellow Wollyhop has its “volcanus" subspecies name incorrectly placed in front of its scientific name. This is corrected here.

The Queen Shearwig, Speargrub and Sheargrub all have their genus incorrectly placed as their specific name. This is corrected here.

Incorrect use of real taxonomy terms

The genus Chilopoda of the Centipare is actually the real world class of the centipedes.

The genus Stauromedusae of the Medusal Slurker is actually a real world order of cnidarians.

The specific name phytohabitans of the Leech Hydroe is actually a real world genus of bacteria.

The genus of the Common Glowcap is actually the real world kingdom of fungi.

Inconsistencies within English localizations

The Coppeler has the Scarpanica genus added in the American localization.

The Armurk has different scientific names: Tegoparastacoidea reptantia (US) and Scalobita rotunda (EU).

Other Notes

The Caustic Dweevil was renamed to Hydro Dweevil and its scientific name to Mandarachnia aquadis in the Switch port of Pikmin 2.

Although the Puffstool has no confirmed family, it shares a genus with the Puffstalk, implying they are likely related.

Missing creatures: Mamuta, Smoky Progg, Blubbug, Puffy Blubbug, Electric Cottonade, Red Blubblimp, Seedbagger, Stuffed Bellbloom.

Unplaceable creatures (extradimensional and/or possibly entirely artificial life forms): Waterwraith, Plasm Wraith.

244 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moth of the Week

Buff-Tip

Phalera bucephala

The buff-tip is part of the family Notodontidae and was first described in 1758 by Carl Linnaeus. They are best know for their resemblance of a broken birch twig when at rest. The name buff-tip comes from the color on the head and edge of the wings, buff: “a light brownish yellow, ochreous colour, typical of buff leather.”

Description The body is hairy, with a buff colored patch on the head followed by a brown ring. The upper body visible from under the wings is a mottled gray to match the forewings. The rest of the body is covered when resting and is a cream white with gray, cream and or brown legs. The forewings are also mottled gray with brown patterning and a buff patch at the tip mirrored on both sides. The hindwings are the same cream as the lower body. The antennae are brown and hidden when camouflaged.

Average wingspan: 55-68 mm

Males are smaller than females

Diet and Habitat Common food plants for this moth include the Norway maple, birch, chestnut, hazel, oak and many more. Caterpillars are social as young larva and eat in groups which can cause the defoliation of their host plants. Adult moths do not feed.

This moth is found across Europe and in Asia to eastern Siberia. It is very common in the British Isles, more so in the south than in the north. They prefer habitats with deciduous trees like open woodlands, scrubs, hedgerows, and urban gardens.

Mating Generally, the buff-tip can be seen from May to July, which is most likely their mating season. This moth is strictly nocturnal so it is also most likely they mate during the night. They have one generation per year with the females laying the eggs in clusters on the underside of leaves. The young larva are sociable and grow to be solitary through 4 instars.

Predators In order to protect itself while resting during the day, this species has adapted to look like a broken birch twig. This deceives common day time predators of moths such as birds and lizards.

Fun Fact This moth has been considered a pest in Lithuania for eating apple trees in the 1900s. High levels of environmental nitrogen compounds can increase outbreaks of the buff-tip.

(Source: Wikipedia, Wildlife Insight, London Wildlife Trust, Butterfly Conservation)

#libraryofmoths#animals#bugs#facts#insects#moth#mothoftheweek#lepidoptera#Notodontidae#buff-tip#Phalera bucephala

196 notes

·

View notes

Text

perhaps my favourite caterpillars are those of the Evening Brown (Melanitis leda). intensely green and hairy, with a pair of superb burgundy horns!

below is their adult form. as adults, they are crepuscular (only active at dawn and dusk), an unusal trait for an ectothermic insect. this adult was found sleeping well after sunset, perhaps the only way to get close enough for a good photo!

Evening Brown, larva and adult, 2 individuals (Melanitis leda), April '24.

#ljsbugblog#bugblr#entomology#macro#insects#lepidoptera#papilionoidea#butterflies#caterpillars#nymphalidae#brush-footed butterflies#satyrinae#melanitis#evening browns#melanitis leda#evening brown

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

My little brother found this weird little caterpillar while we were camping in Washington a while ago. Any idea what this strange fellow is??

Orgyia antiqua, rusty tussock moth. be careful handling fuzzy larvae, although I’ve never had any adverse reaction to my eastern Orgyia, it’s best to avoid handling anything hairy since many of these caterpillars can sting or cause itching

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aah.. Hallo! Don't be scared, this will be a big post!

Warning! You may not like the content, sorry :(

In recent days, "Bugbvie"(?) (I don't know what name to come up with for the city<:'() has experienced hot weather, which has increased the attractiveness of the water bodies many times over. The beaches are overcrowded. However, in the water people encounter an incomprehensible phenomenon - a long and round worm, reaching four meters in height, facing the department. Back then, they were only two meters tall and were already safe for insects, but now they have advanced and are now craving a new "home" in the bodies of insects. The body of a hairworm can reach three to four meters in length, but they are very thin.. It is usually inconspicuous in the water (the color can be either dark or light) and can easily get into the mouth. The female, when laying eggs, may grab you and forcefully push the eggs inside. The hairy one loves fresh water. It lives in streams, small rivers, lakes, ditches. But the most frequent appearance is the river - "Bagena", There are a lot of these worms there, and the mayor of the city said that the path to it should be closed. Hairworms crawl into the mouth through drink or food, and develop inside quite quickly. From egg to larva to full-fledged adult, the worms live inside, gradually turning the insects into "zombies". Worms easily take over the brain and turn it into mush, forcing the insect to go to a pond, where they later crawl out and lay eggs. Is it true that the hairworm — is a parasite? This is not true at all. It is not the worm itself that leads a parasitic lifestyle, but its larvae. Once inside the insect, they begin to absorb nutrients inside the stomach of their "host". At the end of its growth, the individual influences the behavior of its owner, forcing him to strive for water. After which, getting out, eating a hole into it. The insect after this...does not survive. But the praying mantises have adapted, and after such an experience, they can be restored.

One of them is — Tepvo! The hairy worm got out of the body too early and cannot even provide for itself without help. The "master" he was in, the fate is unknown, because I ("grandfather" Tepvo) found him hiding from the rays of the sun under a stone. He brought him home and became his guardian. Tepvo bites. Not literally. He is a very mean person and can hurt you, but he is trying to improve, thanks to.. my help💢. But if you see that he offends you, let me know. Tepvo is a domesticated worm. He will never bother anyone again. The bow on his neck is evidence of this - he is Domesticated

Phew.. sorry for so much information, I completely forgot that I had a separate text for this. If you are interested in reading all this, then.. thank you very much<:_

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

IF this is what my bug identification app says it is, it grows into a cool beetle at some point! yippii!!

[ID: Two pictures of a long, brown, slightly hairy insect that looks like a small caterpillar. It might be a drilini [Schneckenhauskäfer] larva. End ID]

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round 2 - Arthropoda - Diplura

(Sources - 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Diplura (commonly called “Two-pronged Bristletails”) were classically placed together with collembolans and proturans in the class “Entognatha.” However, most recent research points to Entognatha being paraphyletic (ie, grouped together based on morphological similarities and not so much how closely related they actually are.) It would appear that collembolans, proturans, diplurans, and insects all evolved the hexapodous body structure independently.

With that out of the way, there are around 800 species of diplurans, grouped into 10 families. They can be 2–50 millimetres (0.08 – 2 in) long. They lack eyes, wings, and pigment. Unlike proturans, they have long antennae with bead-like segments. Their most distinguishing feature is the pair of cerci projecting backwards from their last abdominal segment. These cerci may be long and thin or short and pincer-like. Some diplurans have the ability to shed their cerci to escape from predators. They have biting mouthparts concealed within their head, consisting of mandibles with several apical teeth. Diplurans with short cerci are carnivorous predators, using their pincer-like cerci to capture springtails, isopods, small myriapods, insect larvae, and other diplurans. Those with long cerci are omnivores, eating soil fungi, mites, springtails, other small soil invertebrates, and/or detritus.

Like collembolans and centipedes, male diplurans lay spermatophores for females to find. These sperm packets are held off the ground by short stalks. After collecting spermatophores, the female will lay eggs on stalks within a crevice or cavity in the ground. Most diplurans will abandon their eggs after laying them, but some will remain to protect their eggs and newborns. Upon hatching, nymphs looks like smaller, less hairy adults.

Diplurans do not have a very good fossil record. One apparent dipluran, Testajapyx, dates to the Carboniferous. Testajapyx had compound eyes and mouthparts resembling those of true insects.

(source)

Propaganda under the cut:

As soil-dwelling organisms, diplurans play a role in indicating soil quality and as a measure of the impact of human activities such as farming.

Diplurans can regenerate lost legs, antennae, and cerci over the course of several moults.

25 notes

·

View notes