#gustavo pittaluga

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Quote

To Gustavo Pittaluga Ollibood, 15 February 1945 Dear Gustavo, This is the third letter I’ve written since arriving at this cultured metropolis, not counting the one I wrote to Don Paulo to compliment him on his triumphant voyage. Portuguese gentlemen are bombastic, not to mention touchy and apt to feel stung if one does not respond to their epistles. While genteel Italian men such as yourself are also liable to get tetchy and write insulting comments on menus to obscure their own idle penmanship. I know a little of everyone except you. What are you up to? What are you doing to get by and what to prevail? What are your plans? You have to reply at once and no pleading excuses, because I’ve now opened fire. Tell me about your life too, the more minute the detail the better. You can imagine just how much I crave news from my position of great solitude, without a single friend. Even my ‘acquaintances’ have given up on me as a result of my sheer apathy. I work, and I work hard and that way I can at least drug my nostalgia hypnogogically (Demetrio will be able to untangle this weird word for you that is not in the dictionary). I await our liberation and return to the homeland. What is your view, those of you over there, of the possible proximity of this return? Now, something about my work: it has wind in its sails. I am forming another new company. They have doubled my salary although there was no provision for that in my contract. Incidentally, as we now need four writers we are running a kind of competition in Mexico and I’ve encouraged Ana María’s brother to put his name forward. I’m bringing Zulueta on as my personal assistant. They have also ‘lifted’ my title to dubbing executive producer. I have complete independence, etc. If you would be interested in coming along as a musician, let me know and we’ll see. There are lots of possibilities to do other things. Mr Warner, as I said in a letter to Demetrio, is happy for me to make films in English, but he doesn’t want me to leave the department; so until it is completely organized, I won’t be able to go ahead, and when I do, it would have to be something that doesn’t stray too far from the ideological line he has always followed. I can’t see why you shouldn’t have the same kind of opportunities? We could make this count in Spain, not financially, obviously, but in terms of prestige, so that Spanish films of the future do not sink into Perojoismo. I’m surrendering myself to Hollywood as a necessary phase in my plan to work in the future on improving our own cinema. Frankly, I don’t dare invite Cruz over, because he is used to other roles in life and I don’t think he would welcome a subordinate one in a film studio, even if his boss were someone like me, who holds him in such high esteem. I got a telegram yesterday from Iris, who is down here. She’s coming to have supper with us on Saturday with René Clair and Bronja. We shall see what that great monument has to tell us. I am fully recovered from the sciatica thanks to the monastic lifestyle they have prescribed me and a wonderful chiropractor. People who don’t know me think I’m 35. Forgive me for saying how healthy and handsome I am at the moment. The only thing holding me back now is my deafness, which, if it carries on, will soon have me composing a patétique or painting a series of caprichos. Or, more likely, asking you to let me design the sets for your next ballet. Apart from the couple of glasses of wine I drink when I get home from work, I never touch alcohol. My diet consists of dried fruits or raw vegetables, with meat twice a week. I sleep on a board and if I don’t say morning prayers, it’s only because we don’t celebrate them in my house. Don Paulo’s book of recipes has arrived, and I have concluded he only wrote it to get at you. First: the author favours quality over quantity. Second: he says that Portuguese wine is good. Third: he only mentions Sherry in passing, along with Madeira, which he showers in glory. Four: he prefers Swiss cooking to Spanish. Five: aware of your preference for Monje, he speaks of decanting fine wines. Personally, what offended me most was his claim that oysters portuguaises are the best in the world. Long live God Don Rascal, weary of Versailles, your worships the Claires of Marennes and all those other crustaceans Mr Pittaluga so appreciates! It’s enough to drive you crazy. I now see Don Paulo never ventured further than Duval’s or Chez Dupont Tout Est Bon when he was in Paris. The only evidence of any good taste in his book is his observation that I make a splendid paella. In response, I am composing another book called The Primitive Palate of Brazilians, subtitled: The French Influence in Certain Backwater Villages. I should be grateful if you would transmit these delicate impressions to Don Paulo; I shall be sending him others to follow directly. Tell José Luis I’m still waiting impatiently for the letter he promised in his New Year’s card. I’ll answer him at once. Warmest regards to him and my ‘maña’ Moncha. More, most affectionate, greetings to Cruz Marín. I can still see him elevating with his presence those Harvard Club gatherings where the doormen took him for the member and Demetrio for his guest. Do not even say good day from me to that wretched Demetrio until he sends me a letter, and then I’ll see what I have to say. You may give Mercedes on the other hand, my warmest regards. This letter is to you [and] Ana María; the fact that it is more comfortable to write in the third-person singular makes it look incorrectly as if I am just writing to you. I have more news of Ana María than of you, although still in less detail than I would like. Much love to you both, Luis

Jo Evans & Breixo Viejo, Luis Buñuel: A Life in Letters

0 notes

Text

Generation of 27

The Generation of '27 (Spanish: Generación del 27) was an influential group of poets that arose in Spanish literary circles between 1923 and 1927, essentially out of a shared desire to experience and work with avant-garde forms of art and poetry. Their first formal meeting took place in Seville in 1927 to mark the 300th anniversary of the death of the baroque poet Luis de Góngora. Writers and intellectuals paid homage at the Ateneo de Sevilla, which retrospectively became the foundational act of the movement.

Terminology:

The Generation of '27 has also been called, with lesser success, "Generation of the Dictatorship", "Generation of the Republic", "Generation Guillén-Lorca" (Guillén being its oldest author and Lorca its youngest), "Generation of 1925" (average publishing date of the first book of each author), "Generation of Avant-Gardes", "Generation of Friendship", etc. According to Petersen, "generation group" or a "constellation" are better terms which are not so much historically restricted as "generation".

Aesthetic style:

The Generation of '27 cannot be neatly categorized stylistically because of the wide variety of genres and styles cultivated by its members. Some members, such as Jorge Guillén, wrote in a style that has been loosely called jubilant and joyous and celebrated the instant, others, such as Rafael Alberti, underwent a poetic evolution that led him from youthful poetry of a more romantic vein to later politically-engaged verses.

The group tried to bridge the gap between Spanish popular culture and folklore, classical literary tradition and European avant-gardes. It evolved from pure poetry, which emphasized music in poetry, in the vein of Baudelaire, to Futurism, Cubism, Ultraistand Creationism, to become influenced by Surrealism and finally to disperse in interior and exterior exile following the Civil Warand World War II, which are sometimes gathered by historians under the term of the "European Civil War". The Generation of '27 made a frequent use of visionary images, free verses and the so-called impure poetry, supported by Pablo Neruda.

Members:

In a restrictive sense, the Generation of '27 refers to ten authors, Jorge Guillén, Pedro Salinas, Rafael Alberti, Federico García Lorca, Dámaso Alonso, Gerardo Diego, Luis Cernuda, Vicente Aleixandre, Manuel Altolaguirre and Emilio Prados. However, many others were in their orbit, some older authors such as Fernando Villalón, José Moreno Villa or León Felipe, and other younger authors such as Miguel Hernández. Others have been forgotten by the critics, such as Juan Larrea, Pepe Alameda, Mauricio Bacarisse, Juan José Domenchina, José María Hinojosa, José Bergamín or Juan Gil-Albert. There is also the "Other generation of '27", a term coined by José López Rubio, formed by himself and humorist disciples of Ramón Gómez de la Serna, including: Enrique Jardiel Poncela, Edgar Neville, Miguel Mihura and Antonio de Lara, "Tono", writers who would integrate after the Civil War (1936–39) the editing board of La Codorniz.

Furthermore, the Generation of '27, as clearly reflected in the literary press of the period, was not exclusively restricted to poets, including artists such as Luis Buñuel, the caricaturist K-Hito, the surrealist painters Salvador Dalí and Óscar Domínguez, the painter and sculptor Maruja Mallo, as well as Benjamín Palencia, Gregorio Prieto, Manuel Ángeles Ortiz and Gabriel García Maroto, the toreros Ignacio Sánchez Mejías and Jesús Bal y Gay, musicologists and composers belonging to the Group of Eight, including Bal y Gay, Ernesto Halffter and his brother Rodolfo Halffter, Juan José Mantecón, Julián Bautista, Fernando Remacha, Rosa García Ascot, Salvador Bacarisse and Gustavo Pittaluga. There was also the Catalan Group who presented themselves in 1931 under the name of Grupo de Artistas Catalanes Independientes, including Roberto Gerhard, Baltasar Samper, Manuel Blancafort, Ricard Lamote de Grignon, Eduardo Toldrá and Federico Mompou.

Finally, not all literary works were written in Spanish: Salvador Dalí and Óscar Domínguez also wrote in French. Foreigners such as the Chilean poets Pablo Neruda and Vicente Huidobro, the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges, and the Franco-Spanish painter Francis Picabia also shared much with the aesthetics of the Generation of '27.

The Generation of '27 was not exclusively located in Madrid, but rather deployed itself in a geographical constellation which maintained links together. The most important nuclei were in Sevilla, around the Mediodía review, Tenerife around the Gaceta de Arte, and Málaga around the Litoral review. Others members resided in Galicia, Catalonia and Valladolid.

The Tendencies of '27:

The name "Generation of 1927" identifies poets that emerged around 1927, the 300th anniversary of the death of the Baroque poet Luis de Góngora y Argote to whom the poets paid homage. It sparked a brief flash of neo-Gongorism by outstanding poets like Rafael Alberti, Vicente Aleixandre, Dámaso Alonso, Luis Cernuda, Gerardo Diego and Federico García Lorca.

Spanish Civil War aftermath:

The Spanish Civil War ended the movement: García Lorca was murdered, Miguel Hernandez died in jail and other writers (Rafael Alberti, Jose Bergamin, León Felipe, Luis Cernuda, Pedro Salinas, Juan Ramón Jiménez, Bacarisse) were forced into exile, although virtually all kept writing and publishing late throughout the 20th century.

Dámaso Alonso and Gerardo Diego were among those who reluctantly remained in Spain after the Francoists won and more or less reached agreements with the new authoritarian and traditionalist regime or even openly supported it, in the case of Diego. They evolved a lot, combining tradition and avant-garde, and mixing many different themes, from toreo to music to religious and existentialist disquiets, landscapes, etc. Others, such as Vicente Aleixandre and Juan Gil-Albert, simply ignored the new regime, taking the path of interior exile and guiding a new generation of poets.

However, for many Spaniards the harsh reality of Francoist Spain and its reactionary nature meant that the cerebral and aesthetic verses of the Generation of '27 did not connect with what was truly happening, a task that was handled more capably by the poets of the Generation of '50 and the social poets.

Statue:

A statue dedicated to the Generation 27 Poets is now in Seville in Spain. The inscription on the monument translates as 'Seville The poets of the Generation of 27'

List of members[edit]

Rafael Alberti (1902–1999)

Vicente Aleixandre (1898–1984)

Amado Alonso (1897–1952)

Dámaso Alonso (1898–1990)

Manuel Altolaguirre (1905–1959)

Francisco Ayala (1906–2009)

Mauricio Bacarisse (1895–1931)

José Bello (1904–2008)

Rogelio Buendía (1891–1969)

Alejandro Casona (1903–1965)

Juan Cazador (1899–1956)

Luis Cernuda (1902–1963)

Juan Chabás (1900–1954)

Ernestina de Champourcín (1905–1999)

Gerardo Diego (1896–1987)

Juan José Domenchina (1898–1959)

Antonio Espina (1894–1972)

Agustín Espinosa (1897–1939)

León Felipe (1884–1968)

Agustín de Foxá (1903–1959)

Pedro García Cabrera (1905–1981)

Federico García Lorca (1898–1936)

Pedro Garfias (1901–1967)

Juan Gil-Albert (1904–1994)

Ernesto Giménez Caballero (1899–1988)

Jorge Guillén (1893–1984)

Emeterio Gutiérrez Albelo (1905–1937)

Miguel Hernández (1910–1942)

José María Hinojosa (1904–1936)

Enrique Jardiel Poncela (1901–1952)

Rafael Laffón (1895–1978)

Antonio de Lara (1896–1978)

Juan Larrea (1895–1980)

José López Rubio (1903–1996)

José María Luelmo (1904–1991)

Francisco Madrid (1900–1952)

Paulino Masip (1899–1963)

Concha Méndez (1898–1986)

Miguel Mihura (1905–1977)

Edgar Neville (1899–1967)

Antonio Oliver (1903–1968)

Pedro Pérez-Clotet (1902–1966)

Rafael Porlán (1899–1945)

Emilio Prados (1899–1962)

Joaquín Romero Murube (1904–1969)

Pedro Salinas (1891–1951)

Guillermo de Torre (1900–1971)

José María Souvirón (1904–1973)

Miguel Valdivieso (1897–1966)

Fernando Villalón (1881–1930)

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Viridiana (Luis Buñuel, 1961)

Cast: Silvia Pinal, Francisco Rabal, Fernando Rey, Margarita Lozano, Victoria Zinny, Teresita Rabal, José Calvo, José Manuel Martín, Luis Heredia, Joaquín Roa, Lola Gaos, María Isbert. Screenplay: Julio Alejandro, Luis Buñuel, based on a novel by Benito Pérez Galdós. Cinematography: José F. Aguayo. Set decoration: Francisco Canet. Film editing: Pedro del Rey. Music: Gustavo Pittaluga.

It's hard to believe today that Viridiana, with its heavily moral tone, was once considered blasphemous, but ours is a day when anything sacred is routinely held up for scrutiny. It's the first work of Luis Buñel's greatest period as writer-director, and while it doesn't quite rise to the exalted standard of Belle de Jour (1967) or The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972), it wrangles effectively with their topics, including middle-class morality and the repressive element of Catholicism. Silvia Pinal gives the title role credibility, moving from naïveté through disillusionment to a final note of ambiguity: Has Viridiana truly fallen from the grace she has so ardently sought? The film is also a triumph of casting, not only in the key roles of Don Jaime (Fernando Rey), Viridiana's lecherous, tormented uncle, and Jorge (Francisco Rabal), his equally lecherous but profoundly untormented bastard son, but also Margarita Lozano as Ramona, Don Jaime's and later Jorge's maid-mistress, and Teresita Rabal as Rita, Ramona's sly, sneaky daughter, And then there's the gallery of grotesques, the beggars whom Viridiana naively takes in and tries to care for. Is there a more horrifying scene than the one that culminates in Buñuel's famous parody of Leonardo's The Last Supper, in which the beggars nearly destroy Don Jaime's house, which Jorge is trying to restore? It can be argued that the avaricious Jorge gets what's coming to him, of course, but Buñuel is never as simplistic as that, viz., the deep ambiguity of the closing scene in which the virtuous Viridiana has let down her hair and forms a threesome -- at the card table but where else? -- with Jorge and Ramona.

7 notes

·

View notes

Audio

LA GENERACIÓN DE LA REPÚBLICA. MÚSICOS ESPAÑOLES EN EL EXILIO

En el Curso de Siglo XX del Aula de Mayores he hablado hoy de la Generación de la República.

He tratado de destacar el esencial papel que el grupo jugó en la renovación de la música española dentro de ese período que José Carlos Mainer llamó la Edad de Plata de la Cultura Española. Fue esa vocación y esa convicción de estar sirviendo a la regeneración de la música española la que une a unos compositores por encima de su indiscutible heterogeneidad estética y geográfica; y eso a pesar de que la mayoría tenía como modelo al Falla de los años 20 y el neoclasicismo que llegaba de París. Gustavo Pittaluga lo dejaba claro en su famoso Manifiesto publicado por La Gaceta Literaria tras la presentación del Grupo de los Ocho en la Residencia de Estudiantes de Madrid en noviembre de 1930.

0 notes

Link

This track is from the album Segundo Ciclo and is available for purchase on CD Baby here: www.cdbaby.com/cd/danieldiaz

Composed and performed by Daniel Diaz Gustavo Paglia: Bandoneon DD: lead bass guitar, acoustic drums, synthesizers, vibes.

Recorded at The Pleasure Dome Buenos Aires, 1996. Released by Timeless Records (P)2002

Artwork by Sergio Pittaluga

1 note

·

View note

Photo

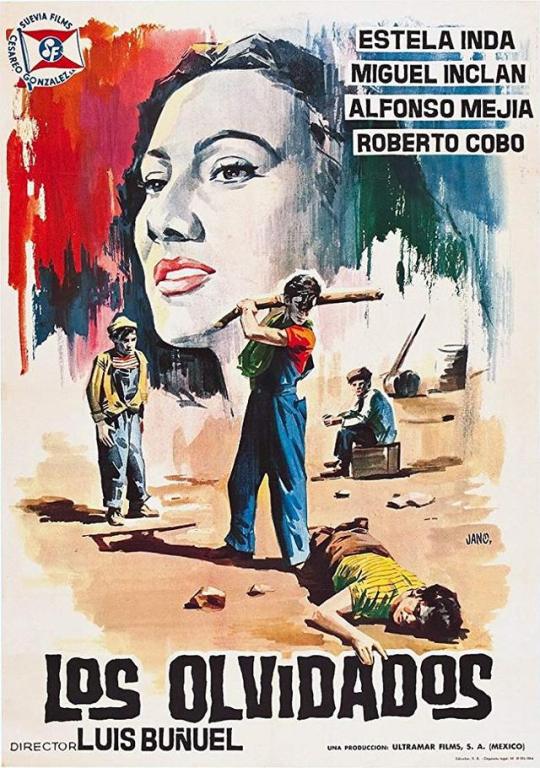

Los olvidados es una película mexicana filmada del 6 de febrero al 9 de marzo de 1950 en los estudios Tepeyac y en locaciones del D. F., estrenada el 9 de noviembre del mismo año en el cine México.1 Escrita y dirigida por Luis Buñuel, que obtuvo el premio al mejor director en el Festival de Cannes y que ha sido nombrada Memoria del Mundo por la Unesco.2 Los olvidados cuenta una historia trágica y realista sobre la vida de unos niños en un barrio marginal de la Ciudad de México. Esta película es la obra más relevante desde que Buñuel comenzó su etapa mexicana. Tras el éxito comercial que le proporcionó El gran Calavera, el productor Óscar Dancigers le propuso que dirigiese una nueva película sobre los niños pobres de México. La película se sitúa en la línea del neorrealismo italiano, al que Buñuel aporta su toque surrealista como se puede observar en la secuencia del sueño de Pedro, la obsesión por las gallinas o el huevo lanzado hacia la cámara.

SINOPSIS

Tras un prólogo inmerso en imágenes de Nueva York, París y Londres; se advierte de la universalidad de la tragedia que va a producirse, la cámara localiza enclaves reconocibles de la Ciudad de México. En uno de sus barrios marginales, Jaibo (Roberto Cobo) es un adolescente que escapa de un correccional para reunirse con Pedro (Alfonso Mejía). En presencia de él, Jaibo mata a Julián, el muchacho que supuestamente le delató. También intenta robar a un ciego al que finalmente maltrata en un descampado.

Cuando Pedro llega a su casa su madre no quiere darle de comer, lo que origina la secuencia onírica y surrealista en que la madre le ofrece unas vísceras que Jaibo le arrebata saliendo debajo de la cama donde yace el cadáver de Julián.

Otro niño, que ha sido abandonado por su padre en la ciudad, Ojitos, entra al servicio del ciego como lazarillo, que ejerce de curandero en casa de Meche, una turbadora adolescente de la que el ciego se quiere aprovechar.

Pedro intenta recobrar la estima de su madre comenzando a trabajar, pero sus buenas intenciones son frustradas por el comportamiento de Jaibo que comete un robo del que acusan a Pedro, que es arrestado por ello en una granja escuela. El director de la institución, confiando en el chico, le da cincuenta pesos y le manda a un recado, pero Jaibo le roba el dinero. Pedro entonces le denuncia como asesino de Julián, y Jaibo se venga matándolo en el gallinero de la casa de Meche. Esta y su abuelo arrojan su cadáver a un muladar. Entretanto, Jaibo es abatido por disparos de la policía, y su agonía se ve sobreimpresionada por un perro que avanza y la madre de Pedro diciendo «buenas noches» dirigiendo una mirada a Meche y su abuelo, que llevan el cadáver de su hijo en un saco, a lomos de una burra.

ANÁLISIS

Aparentemente, la película es un drama o tragedia neorrealista, documentada en los bajos fondos de la gran urbe y que tiene una intención marcadamente social. Sin embargo, el trazado subliminal, crea todo un flujo subconsciente en que los temas son la ausencia del padre, el complejo de Edipo, la orfandad, la maldad y la muerte. Todo esto está subrayado por secuencias oníricas, por la extraña y constante presencia de las gallinas, la rítmica repetición de brazos que se alzan cada diez minutos para golpear y matar cruelmente y, no menos importante, la vanguardista música, atormentada e inquietante, de Rodolfo Halffter sobre temas de Gustavo Pittaluga. Ello crea un clima de malestar que lleva al filme a la característica poética surrealista y tortuosa del aragonés.

Como ha recordado Octavio Paz, Buñuel muestra la evolución del surrealismo, que se inserta ahora en las formas tradicionales del relato, en este caso una tragedia sin coturno, integrando «las imágenes irracionales que brotan de la mitad oscura del hombre».

El estreno de la película en México suscitó violentas reacciones, y se pidió desde diversas instancias mediáticas la expulsión del cineasta del país. A los cuatro días fue retirada de los cines sin que faltaran intentos de agresión física contra Buñuel. Afortunadamente, algunos intelectuales salieron en su defensa y, tras recibir el premio al mejor director en el Festival de Cannes de 1951 (en una edición donde competían Milagro en Milán de Vittorio de Sica o Eva al desnudo de Joseph L. Mankiewicz), Buñuel fue «redescubierto» en los medios franceses y europeos, lo que le valió el respeto y la audiencia en México. La película fue reestrenada al año siguiente en una buena sala de la capital mexicana, donde permanecería más de dos meses en cartel.

Y su éxito comercial se dio pese a su extrema dureza, pues como señaló André Bazin, se trata de un ejemplo del "cine de la crueldad", en consonancia con las propuestas que para el teatro había hecho Antonin Artaud con su "teatro de la crueldad". Buñuel se permite mostrar lisiados sin el menor intento de mover la compasión del espectador hacia ellos. Antes al contrario, muestra al ciego cargado de rasgos negativos (lujurioso, avaro y chivato), y esto se refuerza eligiendo para este personaje a un actor conocido por su interpretación de numerosos ��malos» en el cine mexicano.

Los dos grandes temas son la sexualidad y la muerte, sin olvidarnos de la pobreza, la marginación y la miseria, que recorren el primero los componentes surrealistas y profundos de la psique humana y el segundo la dura lucha por la vida de la realidad social. Desde este punto de vista, «olvidados» son todos sus personajes: Ojitos, que es abandonado a su suerte por su padre en la gran ciudad para librarse de una boca que alimentar; Pedro, a quien su madre le niega el afecto y aun el sustento; esta, a su vez, repudiada y vejada por su marido, y luego abandonada; Jaibo, de orfandad total, que ha tenido que sobrevivir en la calle, e incluso el ciego, desasistido de beneficencia, por lo que tiene que mendigar en la calle, desvalido como el hombre-tronco, que se desplaza sobre un carrito con ruedas, y del que los chicos se burlan quitándole su medio de locomoción y tirándolo calle abajo.

Esta tremenda visión del mundo remata en la doble muerte sobreimpresionada de Pedro y Jaibo: ni el bien ni el mal escapan a ella, como constata trágicamente la película (al menos en las condiciones sociales en las que se desarrolla este drama). Su valor cinematográfico se desprende de todas estas sugerencias subterráneas, que, unido a la trama contundente y brutal, crean una gran catarsis.

Los olvidados, junto a Metrópolis de Fritz Lang, toda la cinematografía de los hermanos Lumière y El Mago de Oz de Victor Fleming son las únicas piezas del séptimo arte que han recibido la consideración de Memoria del Mundo.

Este filme ocupa el lugar 2 dentro de la lista de las 100 mejores películas del cine mexicano, según la opinión de 25 críticos y especialistas del cine en México, publicada por la revista Somos en julio de 1994.

— Wikipedia

#los olvidados#Luis Buñuel#Buñuel#wikipedia#en español#zaboravljeni#the forgotten ones#die vergessenen#the young and the damned#zapomniani#samfunnets stebarn#Jûdai no bôryoku#i figli della violenza#elhagyottak#Xehasmenoi apo tin koinonia#pitié pour eux#Medelijden met hen#De vergetenen

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Songs Of The Spanish Civil War

"This record is an imaginary journey through time, from 1936 to 1939, and space, from Asturia to La Mancha, from the lands of the Basques to Andalusia, from Castille to Estremadura. Throughout it appear and vanish the shadowy figures of the Republican militiamen, the International Brigades, La Pasionaria, Durruti, Frederico Garcia Lorca. The verses of Louis Aragon could serve as an introduction and a conclusion: I remember a tune that one could not hear / Without the heart beating and the blood catching fire, / Without the fire rekindling like a heart beneath the ashes / And one knew at last why the sky is blue."

Album został wydany w 1963 roku przez Le Chant du Monde, a ponownie ukazał się w 1996 roku. Piosenki nagrał w Barcelonie zespół Cobla de Barcelone pod dyrektywą Rodolfo Halfftera i Gustavo Pittalgua. Traktują one nie tylko o wojnie domowej w hiszpanii (1936-1939) - wśród nich są również popularne piosenki, sięgające datą nawet do początków XIX wieku, a które śpiewano (niekiedy w zmodyfikowanej wersji) podczas wojny przeciwko faszyzmowi.

Lista utworów: 1. Hymn Of Riego (Song Of Freedom) - Cobla De Barcelone Chor Et Orch/Gustavo Pittaluga/Rodolfo Halffter 2. The Four Generals (Song Of The Defence Of Madrid) - Cobla De Barcelone Chor Et Orch/Gustavo Pittaluga 3. We Are The Soldiers Of the Basque Land (Euzko Gudari) - Cobla De Barcelone Chor/Gustavo Pittaluga/Rodolfo Halffter 4. You Know My Address - Cobla De Barcelone Chor Et Orch/Rodolfo Halffter 5. The Sardana Of The Nuns - Cobla De Barcelone Chor Et Orch/Gustavo Pittaluga/Rodolfo Halffter 6. What Will Happen? - Cobla De Barcelone Chor Et Orch/Gustavo Pittaluga 7. La Santa Espina (Sardana of Freedom) - Cobla De Barcelone Chor Et Orch/Gustavo Pittaluga/Rodolfo Halffter 8. The Crossing Of The Ebro - Cobla De Barcelone Chor Et Orch/Rodolfo Halffter 9. The Armoured Train - Cobla De Barcelone Chor Et Orch/Rodolfo Halffter 10. The Fort Of San Cristobal - Cobla De Barcelone Chor Et Orch/Rodolfo Halffter 11. Sailors - Cobla De Barcelone Chor Et Orch/Gustavo Pittaluga 12. Eat It - Cobla De Barcelone Chor Et Orch/Gustavo Pittaluga 13. The Violet Banner - Cobla De Barcelone Chor Et Orch/Gustavo Pittaluga 14. The Mowers - Cobla De Barcelone Chor Et Orch/Gustavo Pittaluga/Rodolfo Halffter

0 notes

Quote

In a restrictive sense, the Generation of '27 refers to ten authors, Jorge Guillén, Pedro Salinas, Rafael Alberti, Federico García Lorca, Dámaso Alonso, Gerardo Diego, Luis Cernuda, Vicente Aleixandre, Manuel Altolaguirre and Emilio Prados. However, many others were in their orbit, some older authors such as Fernando Villalón, José Moreno Villa or León Felipe, and other younger authors such as Miguel Hernández. Others have been forgotten by the critics, such as Juan Larrea, Pepe Alameda, Mauricio Bacarisse, Juan José Domenchina, José María Hinojosa, José Bergamín or Juan Gil-Albert. There is also the "Other generation of '27," a term coined by José López Rubio, formed by himself and humorist disciples of Ramón Gómez de la Serna, including: Enrique Jardiel Poncela, Edgar Neville, Miguel Mihura and Antonio de Lara, "Tono", writers who would integrate after the Civil War (1936–39) the editing board of La Codorniz. Furthermore, the Generation of '27, as clearly reflected in the literary press of the period, was not exclusively restricted to poets, including artists such as Luis Buñuel, the caricaturist K-Hito, the surrealist painters Salvador Dalí and Óscar Domínguez, the painter and sculptor Maruja Mallo, as well as Benjamín Palencia, Gregorio Prieto, Manuel Ángeles Ortiz and Gabriel García Maroto, the toreros Ignacio Sánchez Mejías and Jesús Bal y Gay, musicologists and composers belonging to the Group of Eight, including Bal y Gay, Ernesto Halffter and his brother Rodolfo Halffter, Juan José Mantecón, Julián Bautista, Fernando Remacha, Rosa García Ascot, Salvador Bacarisse and Gustavo Pittaluga. There was also the Catalan Group who presented themselves in 1931 under the name of Grupo de Artistas Catalanes Independientes, including Roberto Gerhard, Baltasar Samper, Manuel Blancafort, Ricard Lamote de Grignon, Eduardo Toldrá and Federico Mompou.

Generation of '27 - Wikipedia

1 note

·

View note

Video

Luis Buñuel, Los olvidados, México, 1950 from Exilio Regreso on Vimeo.

En esta película recordada por los críticos, pero olvidada por el público e inhallable en Internet, participaron varios creadores del exilio español en México. Además de Luis Buñuel: Max Aub y Juan Larrea intervinieron en los diálogos; Gustavo Pittaluga y Rodolfo Halffter compusieron la música; Luis Alcoriza escribió el guión, mano a mano con Buñuel. Fue tal el impacto durante su estreno, que sus coautores estuvieron en un tris de ser expulsados del país que les había acogido.

Título: Los olvidados

Título original: Los olvidados

Dirección: Luis Buñuel

País: México

Año: 1950

Duración: 80 min.

Género: Criminal, Drama

Reparto: Estela Inda, Miguel Inclán, Alfonso Mejía, Roberto Cobo, Alma Delia Fuentes, Francisco Jambrina, Jesús Navarro, Efraín Arauz, Sergio Villarreal, Jorge Pérez, Javier Amézcua, Mário Ramírez

Distribuidora: Ultra Film

Productora: Ultramar Films

Agradecimientos: Armando List Arzubide, José Luis Patiño, José Luis Patiño, Maria de Lourdes Ricaud

Departamento editorial: Alberto Valenzuela

Departamento musical: Rodolfo Halffter

Diálogos: Jesus Camacho V. 'Urdimalas', Juan Larrea, Max Aub

Dirección: Luis Buñuel

Dirección artística: William W. Claridge

Diseño de producción: Edward Fitzgerald

Fotografía: Gabriel Figueroa

Guión: Luis Alcoriza, Luis Buñuel

Maquillaje: Armando Meyer

Montaje: Carlos Savage

Música: Gustavo Pittaluga, Rodolfo Halffter

Sonido: Jesús González Gancy, José B. Carles, William W. Claridge

0 notes

Text

El violonchelo de la República

[El pianista Pablo Amorós y el violonchelista Iagoba Fanlo. La foto es de Miguel Á. Fernández]

El violonchelista Iagoba Fanlo y el pianista Pablo Amorós registran en el sello IBS cinco obras de sendos compositores españoles de la conocida como Generación de la República

En diciembre de 1930 se presentó en la Residencia de Estudiantes de Madrid el llamado Grupo de los Ocho, ocho compositores nacidos en torno al cambio de siglo, vinculados a la capital española y que habían iniciado su actividad artística adulta en torno a 1920. Uno de ellos, Gustavo Pittaluga escribió para la ocasión un manifiesto que vinculaba su estilo al de Los Seis franceses: "Hacer música, este es el único propósito, y hacerla sobre todo, antes que nada, por gusto, por recreo, por diversión, por deporte", escribió Pittaluga. Los Ocho fueron la facción más visible de lo que historiográficamente ha sido conocido después como Generación de la República (o Generación del 27, en asimilación al grupo literario, mucho más célebre, que floreció por la misma época), un conjunto de compositores heterogéneo pero herederos del arte de Falla que, después de un tiempo de olvido, empiezan a ser revindicados, aunque no sin problemas. "No conocía su música", admite el pianista cordobés Pablo Amorós, "pero cuando Iagoba me propuso este trabajo y empezamos a ensayarla, quedé absolutamente prendado".

El violonchelista donostiarra Iagoba Fanlo empezó a recopilar música de estos compositores para su instrumento "hace cinco o seis años". "Hay muchísima, y de un nivel altísimo. Estamos ante una generación de compositores excepcionales a los que atropelló una guerra que hizo que muchos tuvieran que exiliarse. De hecho los cinco compositores que acabé escogiendo para este disco acabaron exiliados". Son los madrileños Roberto Halffter y Salvador Bacarisse, el tarraconense nacionalizado británico Roberto Gerhard, el aragonés Simón Tapia y la asturiana María Teresa Prieto.

El Adagio y Fuga de Prieto se graba por primera vez, "lo que es incomprensible", destaca Fanlo. "Si Bach hubiera vivido en el siglo XX habría escrito así, y lo digo yo, que soy un apasionado del arte de Bach", y sigue: "Se trata de la obra más solemne y monumental de las que se incluyen en este disco. La partitura la encontré a través de un anticuario en California". "Posiblemente sea la obra menos reconocible como española, tiene un carácter más escolástico, como homenaje evidente a Bach", añade Amorós. "Pero es una música extraordinaria. Que nadie piense que esta pieza cumple el papel de cuota femenina en nuestro disco. La obra es buenísima", y en el mismo sentido añade su compañero: "Si no decimos el nombre de su autor, ¿puede haber alguien que al escuchar la música sepa si la escribió una mujer, un hombre, un negro, un judío, un rojo, un blanco...? A mí eso me da igual. La música de María Teresa Prieto es buenísima. Eso es lo que me importa. Tengo en reserva su Concierto para violonchelo, dificilísimo, que haré con la Orquesta Sinfónica del Principado de Asturias en la temporada 2018-19, y espero grabar también".

Catedrático desde hace años en el Superior de Madrid, el violonchelista vasco no entiende tampoco que la obra de Bacarisse (Introducción y Variaciones) estuviese inédita. "Es la primera vez que se toca. Me puso sobre la pista del manuscrito Miguel Ángel Marín. Es una obra fabulosa, escrita en París: se nota el entorno. Nace de la mejor tradición vinculada a la capital francesa, de Debussy a Honegger". Más conocidas son las Sonatas de Halffter y de Gerhard. "La primera no es fácil de describir: formalmente es extraordinaria, pero tiene también la frescura típica de Halffter. Su lenguaje es personalísimo y la escritura es perfecta, si mueves un sostenido provocas un desastre. En cuanto a la de Gerhard, tiene un segundo movimiento de un lirismo maravilloso y un tercer tiempo en el que emplea un motivo de una canción de las milicias republicanas. Hay pese a todo en Gerhard giros sarcásticos un poco a lo Shostakóvich, una especie de queja sobre la realidad. Es música de un melodismo franco, convencional incluso, pero con ese toque personal de acidez". Menos conocida es posiblemente la personalidad de Simón Tapia, que, como Halffter y Prieto, acabó también en México: "Fue reclamado directamente por el presidente Cárdenas para el Colegio de España, cuando Tapia estaba en un campo de concentración francés. Tapia había sido alumno de D'Indy en París. Su Sonata no tiene desperdicio. Lleva toda la Segunda Escuela de Viena dentro".

Para Amorós, "es una obligación dar a conocer la obra de estos compositores, pero también un placer y una satisfacción. En octubre presentamos tres de estas piezas en Lima, en un concierto en el que hicimos además la Sonata de Debussy y la Arpeggione de Schubert, y la gente se entusiasmó... ¡con la música española! Lo otro gustó, claro, son grandes obras de repertorio, pero fue la música de Prieto, Tapia y Halffter la que más impactó". Para Fanlo "estos músicos beben de Falla, pero se abrieron a las vanguardias artísticas, cada uno a su manera. En estas obras hay una calidad artística extraordinaria y un trasfondo histórico que todo el mundo debería conocer. Nuestra grabación no está puesta al servicio de ningún interés, político o de otro tipo. Sólo queremos aportar justicia a la difusión de la obra de unos maestros excepcionales y demasiado olvidados. Espero que hayamos sabido recrearlas como se merecen. El CD está grabado además en una sala de una acústica espectacular, la del Auditorio Manuel de Falla de Granada, por unos técnicos extraordinarios y con unos instrumentos de primer nivel. ¿Que por qué tendría la gente que comprar este disco? Por todo esto que le llevo dicho, porque es una música buenísima y accesible, que van a disfrutar en casa, en el coche, donde sea".

[Diario de Sevilla. 9-07-2017]

#iagoba fanlo#pablo amorós#rodolfo halffter#simón tapia#roberto gerhard#maría teresa prieto#salvador bacarisse#shostakóvich#falla#debussy#schubert#bach#miguel ángel marín#gustavo pittaluga#música#music

0 notes