#grand duke dmitri

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Prince Wilhelm of Sweden, Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna (the younger), Tsar Nicholas II, Princess Victoria, Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich and Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna.

#tsar nicholas ii#elizabeth feodorovna#grand duke dmitri#the younger#prince wilhelm of sweden#princess victoria#hesse#tsar#prince#princess#grand duchess#grand duke#grand duchess maria pavlovna#my own

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

#grand duke dmitri#dmitri pavlovich#russian history#french his#wwii#train collection#where the fuck are dmitris trainsss#obscure history#history hyperfixation#trains#history memes#this is actually devastating#fuck the faberge eggs i need to know where his trains went

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grand Duchesses Maria Nikolaevna & Anastasia Nikolaevna joking around with their cousin Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, 1916.

#tumblr fyp#maria nikolaevna#anastasia nikolaevna#grand duke dmitri#dmitri pavlovich#romanovs#romanov#rif#1916#1910s#romanovs being funny#pre-imprisonment

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grand Duchess Marie Alexandrovna on meeting the Hohenfelsens

(safe to say she was not impressed 🤣)

Paris, 16 June 1908

The young Swedish couple" has arrived in our hotel. Little Marie is a very sedate and calm little person, but she poured her heart out to Baby: she feels it terribly meeting here her step-mother and suffers greatly under it. As to poor little Dmitry, he is in perfect despair. He hates the whole thing and loathed the idea of seeing his new Geschwister [siblings]. He comes to me to talk about it.

Of course Uncle Paul and wife manquent de tact [are tactless] in every way: for instance, last Tuesday he arranged a big luncheon with quantities of his French acquaintances and asked us too. It was the first time poor Dmitry went to his house here and Uncle Paul presented him to all the guests as "mon fils aine" [my eldest son]. The boy simply se tordait de désespoir [curled up in despair], we observed it all and in the middle of this unknown company appeared these second children and all the affected French people went into loud ectasies about them [at this time, Vladimir was 11, Irina 4 and Natalie 2], whilst poor Dmitry was pale with concentrated rage and moral suffering.

Marie told Baby that she never would have come here, had she known, how it would be. And people are wonderfully taktlos. They all praise her to the skies when they talk to me, cette charmante Comtesse Hohenfelsen, "elle est adorable, cette femme". Vous trouvez [that charming Countess Hohenfelsen. She's adorable, don't you think?]. I answer, oh! Bien pour moi, c'est très pénible [for me it's all very painful] and I tell them a few truths. Then they at once turn the conversation, as French people hate when they are found at fault et ne désirent pas du tout en savoir d'avantage. [and don't want to be wrong in any way].

As to Uncle Paul, I cannot support at all him here; his whole attitude and tone I find detestable, I don't show it, à quoi bon and I am simply polite with his wife, like with any lady in society I don't care for. I simply writhe when I see in his house portraits of my mother, what a desecration! And he pointed them out to me! I thought one moment I would like to insult him before all his idiotic French guests.

"Dear Mama" - Diana Mandache

This is what I love about digging into original sources. When we read Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna's memoires, the idea we get is that she always had a pleasent relationship with her stepmother, but here (at least according to Maria Alexandrovna, who clearly still held a deep resentment towards her brother and his second wife) it seems things were not so smooth.

It's also interesting (and sad) to notice how she doesn't really consider Grand Duke Paul's children from his second marriage worthy of any note and is even annoyed that the French fawn over them and that Grand Duke Paul introduces Dmitri as his "eldest son", which seems to imply she doesn't consider Vladimir to be his son at all.

It kind of shows what the rest of the family thought about Grand Duke Paul's second family: so irrelevant that it was as if they didn't exist.

#romanov#paul alexandrovich#imperial russia#imperial family#royalty#olga paley#grand duke#grand duchess maria alexandrovna#natalie paley#vladimir paley#irina paley#morganatic marriages#marie pavlovna jr.#dmitri pavlovich#beatrice of coburg

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Felix Yusupov on Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich

During 1912 and 1913 I saw a great deal of the Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, who had just joined the Horse Guards. The Tsar and Tsarina both loved him and looked upon him as a son; he lived at the Alexander Palace and went everywhere with the Tsar. He spent all his free time with me; I saw him almost every day and we took long walks and rides together. Dmitri was extremely attractive: tall, elegant, well-bred, with deep thoughtful eyes, he recalled the portraits of his ancestors. He was all impulses and contradictions; he was both romantic and mystical, and his mind was far from shallow. At the same time, he was very gay and always ready for the wildest escapades. His charm won the hearts of all, but the weakness of his character made him dangerously easy to influence. As I was a few years his senior, I had a certain prestige in his eyes. He was to a certain extent familiar with my "scandalous" life* and considered me interesting and a trifle mysterious. He trusted me and valued my opinion, and be not only confided his inner-most thoughts to me but used to tell me about everything that was happening around him. I thus heard about many grave and even sad events that took place in the Alexander Palace. The Tsar's preference for him aroused a good deal of jealousy and led to some intrigues. For a time, Dmitri's head was turned by success and he became terribly vain. As his senior, I had a good deal of influence over him and sometimes took advantage of this to express my opinion very bluntly. He bore me no grudge and continued to visit my little attic where we used to talk for hours in the friendliest way. Almost every night we took a car and drove to St. Petersburg to have a gay time at restaurants and night clubs and with the gypsies. We would invite artists and musicians to supper with us in a private room; the well-known ballerina Anna Pavlova was often our guest. These wonderful evenings slipped by like dreams and we never went home until dawn. [...] My relations with Dmitri underwent a temporary eclipse. The Tsar and Tsarina, who were aware of the scandalous rumors about my mode of living,* disapproved of our friendship, They ended by forbidding the Grand Duke to see me, and I myself became the object of the most unpleasant supervision. Inspectors of the secret police prowled around our house and followed me like a shadow when I went to St. Petersburg. But Dmitri soon got back his independence. He left the Alexander Palace, went to live in his own palace in St. Petersburg, and asked me to help him with the redecoration of his new home.

*as a young man, Felix Yusupov had many romantic relationships with men and would often attend parties while dressed as a woman. this is presumably what he is referring to here.

source: Lost Splendour by Felix Yusupov, chapter 10

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

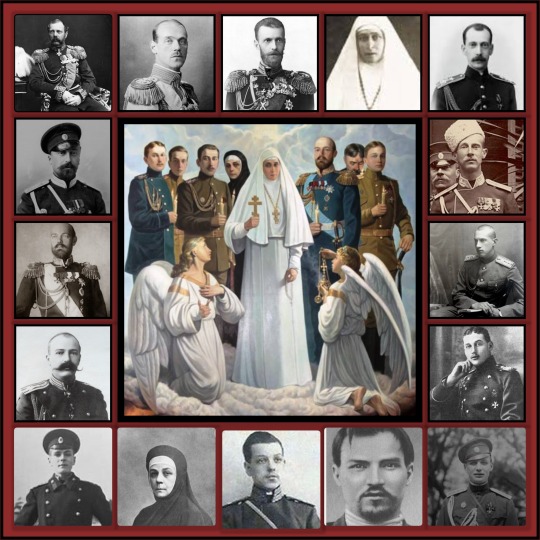

The Romanov Martyrs

I wanted to put together a little memorial that included all the members of the Romanov Family (as well as the members of their staff) that were murdered by the Bolshevik terrorists. This seems like a good week to keep them in our minds. Although we love and mourn the children especially, there were others we cannot forget.

Tsar Alexandre II was hunted down until finally blown to pieces.

Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna lost two sons and five grandchildren (no wonder she could not accept they were dead)

Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich was also hunted down and blown to pieces

Three Mikhailovichi brothers were murdered

Four Konstantinovichi were murdered, three of them brothers; I cannot imagine what their mother, Grand Duchess Elizabeth Mavrikievna, went through...and so on.

May they rest in peace.

#russian history#imperial russia#romanov family#Nicholas II#Tsar Alexander II#Empress Alexandra Feodorovna#Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna#OTMAA#Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich#Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich#Grand Duke Pavel Alexandrovich#Grand Duke Nicholas Mikhailovich#Grand Duke Georgiy Mikhailovich#Grand Duke Sergei Mikhailovich#Grand Duke Dmitry Konstantinovich#Prince Ioann Konstantinovich#Prince Igor Konstantinovich#Prince Konstantin Konstantinovich#Dr. Eugene Botkin#Anna Demidova#ivan karitonov#Akexei Trupp#Sister Varvara Yakolevna#Feodor Remez#mr. johnson

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich is so cool. He's first cousin to both Tsar Nicholas II of Russia and Prince Philip Duke of Edinburgh. Such a large age gap between both, I think that's interesting.” - Submitted by Anonymous

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna of Russia with her husband Prince Wilhelm, Duke of Södermanland and her cousin Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich of Russia

Swedish vintage postcard

#sdermanland#pavlovich#historic#romanov#maria#photography#postal#husband#ansichtskarte#dmitri pavlovich#cousin#maria pavlovna#duchess#grand#photo#sepia#prince wilhelm#swedish#södermanland#vintage#postcard#duke#briefkaart#wilhelm#russia#prince#pavlovna#dmitri#postkarte#tarjeta

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

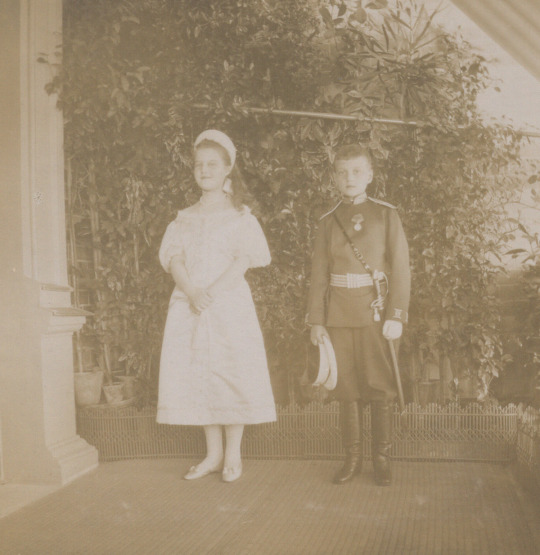

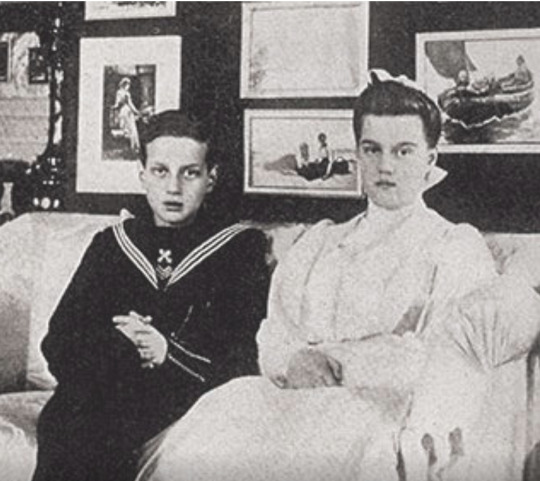

Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna (the younger) with her brother Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich at Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna’s baptism, 1901

#they are so cute!#maria pavlovna the younger#maria pavlovna#dmitri pavlovich#anastasia nikolaevna#baptism#1901#imperial russia#imperial Russian court dresses#kokoshnik#grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich#grand duchess Maria Pavlovna#romanov family

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

My only knowledge about James I's personal life comes from "Bad Gays" podcast and David M. Bergeron's King James & Letters of Homoerotic Desire, so I'm excited to see Mary & George and how they portrayed James

#mary & george#jacobean britain#i laughed so much when i found out galitzine is in it#tbh he should play Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

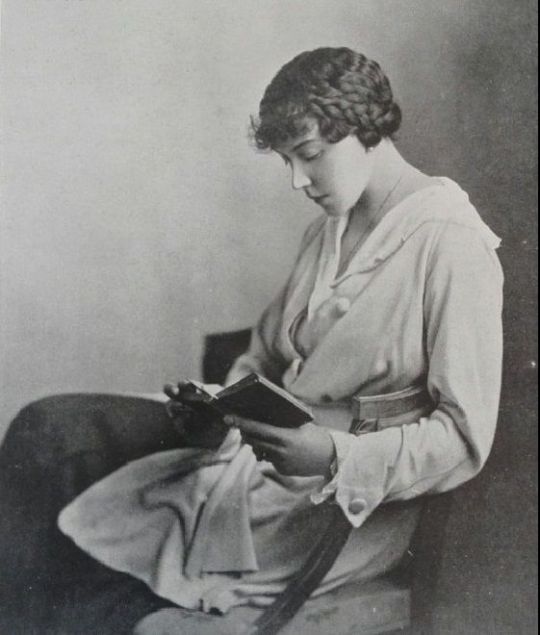

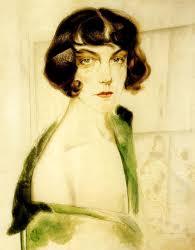

Below a lovely sketch of Maria Pavlovna (1890 - 1958)

This young woman did not have a very happy life. She lost her mother when she was not even three years old. Then she lost her father when Grand Duke Pavel Alexandrovich entered a morganatic marriage without the Tsar's permission and was banished from Russia; he was not allowed to take Maria and/or her brother, Dmitry. The aunt and uncle they stayed with adored them (especially Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich), but the children also lost them. Sergei was blown to pieces by a terrorist, and his wife, Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna, entered a convent.

Maria married twice; both marriages ended in divorce. She had a child with her first husband, who was raised by the father, and the baby she had with her second husband died very young.

I admire Grand Duchess Maria because she never gave up even if "relationships" were never her forte due to the many times she was abandoned (the only human being she truly loved was her brother Dmitry). She escaped Russia without papers and held a number of jobs, earning her own living. She lived in several countries, including Argentina.

Toward the end of her life, Maria and her son were able to rebuild their relationship, and she came and went from his residence. He buried her in the family palace in West Germany when she died. When Maria's brother Dmitry died, her son ensured he was interred next to his sister so she could rest close to him. (gcl)

Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna “the Younger” of Russia posing for a portrait.

#russian history#imperial russia#romanov family#Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna the Younger#Grand Duke Dmitry Pavlovich#Count Lennart Bernadotte#gcl

180 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marianne - The Most Scandalous of the von Pistohlkors Siblings

Marianne von Pistohlkors was born in 1890 and was known by many names throughout her life. Her family called her "Babaka", her friends called her "Malanya".

In 1908, at the age of 17, she married Lt. Col. Peter Petrovich Durnovo, the son of the Minister of Internal Affairs, Pyotr Durnovo, and a classmate of her older brother Alexander. They had one son, Kyrill, born in November 1908. During that time, she was known as Mrs. Durnovo.

There are different versions as to why the couple got divorced just three years after their marriage. Some say Durnovo had a drinking problem and was abusive, others say Marianne was having an affair with none other than Rasputin:

"She was married first to the guards hussar Durnovo. She was acquainted with Rasputin. Once Durnovo, having suddenly appeared at a small gathering of the Elder's admirers, caught the moment when the Elder was embracing his wife. With a strong blow the hussar knocked the Elder down, took his wife away, and Rasputin, lying down, shouted: "I will remember you" - A.I. Spiridonovich

Either way, the couple was divorced in 1911, but it didn't take long for 22-year-old Marianne to find a new husband: a year after her divorce, she married Christopher Ivanovich von Derfelden, another officer and collegue of her brother Alexander. From then on and during most of WWI, she was known as Marianne von Derfelden. And it would be under that name that she would be implicated in one of the most famous murders of history.

Marianne was considered a very attractive woman. She was also witty, inteligent and social, which made her very popular in Saint Petersburg high society in the final years leading up to World War One. One of her most famous stunts was to attend a costume ball given by Kleinmichel dressed as an Egyptian in which she performed a provocative dance with a naval officer (who was not her husband).

Two photographs of the evening were published in a famous social magazine and were a tremendous success.

At the time, Marianne was also an amateur actress and model.

After World War One started, Marianne became a nurse and drove ambulances around the city. On January 5, 1916, she received the St. George Medal for her efforts.

Since her mother and stepfather had returned to Russia in 1914, Marianne had also developed a close friendship (some even refer to it as flirtation) with her step-brother, Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich. They attended the same parties and had the same circle of friends. They also were among the Saint Petersburg aristocratic groups that hated Rasputin and thought he was a bad influence on the Empress.

This was a time when the rumours in Petrograd society were particularly wild and farfetched, so the nature of Dmitri and Marianne's relationship varies between "friendly", "flirtatious" to "they were lovers and took pictures of themselves reenacting Kamasutra positions" and "they participated in orgies thrown by Prince Felix Yussupov in his palace".

Whatever the nature of their relationship, the truth was that Marianne was deeply involved in the conspiracy to murder Rasputin. It had never been fully proved that she was the Yussupov Palace, but she knew about the plans and there were rumours that some of the meetings to organize the murder took place at her apartment.

When it was discovered that Dmitri was one of the co-conspirators and was sent to the Persian front as punishment, Marianne was one of the few people who went to the train station to say goodbye, which ultimatly alerted the authorities to her participation and Empress Alexandra ordered her house arrest. Her telephone was taken and her house was searched [apparently, when the guards asked for a key to open a closed drawer, she told them 'you'll only find love letters'], but nothing was discovered and she was set free on three days later.

A few days after Dmitri's departure, the French Ambassador, Maurice Paléologue, met Marianne at a restaurant and this was what he wrote about the meeting in his memoirs:

Dining at the Restaurant Contant this evening, I saw pretty Madame D----- at the next table with three officers of the Chevaliers-Gardes; she was in mourning. During the night of January 6-7, she was arrested on suspicion of having taken part in the murder of Rasputin, or at any rate known of the preparations. Thanks to the high influences which protect her, she was simply kept under observation in her flat and released three days later. When a police officer asked her for the key of her bureau in order to secure her papers, she replied sweetly and simply: "You'll only find love-letters." The remark is Madame D----- personified. Twenty-six years of age, divorced, remarried at once, then separated from her second husband, she leads a wild life. Every evening, or rather every night, she holds high revel until morning: theatre, ballet, supper, gypsy singers, tango, champagne, etc. And yet it would be a great mistake to judge her solely by this tawdry dissipation; at bottom she is warm-hearted, proud and an enthusiast. Rasputin's murder, of the preparations for which she knew, came as a thunderbolt to her. The Grand Duke Dimitri seemed to her a hero, the saviour of Russia. She went into mourning on learning the news of his arrest. When she heard that he had been sent to the Russian army front in Persia, she swore to continue his patriotic work and avenge him. Since the police evacuated her residence four days ago, she has been concerned in all the ramifications of the plot against the Emperor, carrying letters to some and passwords to others. Yesterday she called on two colonels of the guard to win them over to the good cause. She knows that the agents of the terrible Okhrana are watching her, and is fertile in resources to throw them off the scent. Any night she expects to be incarcerated in the fortress or sent to Siberia; but she has never been so happy before. The heroines of the Fronde, Madame de Longueville, Madame de Montbazon and Madame de Lesdiguières must have known this unreal exaltation, by virtue of which the conscientiousness of a great peril rekindles a great love. When she finished dinner she passed close to my table, followed by her three officers. She came up to me. I rose to shake hands. In rapid tones she said: "I know that our mutual friend came to see you yesterday and told you everything . . . He's extremely anxious about me. It's only natural . . . he loves me so much! Anyhow, he thought you would be ready to help me in case of disaster and was anxious to make certain. But I knew what you'd say. What could you do for me if things went badly? Nothing; that's obvious . . . . But I'm grateful for the nice things you've said about me, and I'm sure that at the bottom of your heart---though not as ambassador---I have your approval . . . We may never meet again. Good-bye!" And with these words she sped away swiftly and silently, escorted by her chevaliers-gardes.

As mentioned in the quote above, by 1916, Marianne was already separated from her second husband and would soon marry again, this time in October 1917 to Count Nikolai Konstantinovich von Zarnekau, a son of Prince Konstantin of Oldenburg.

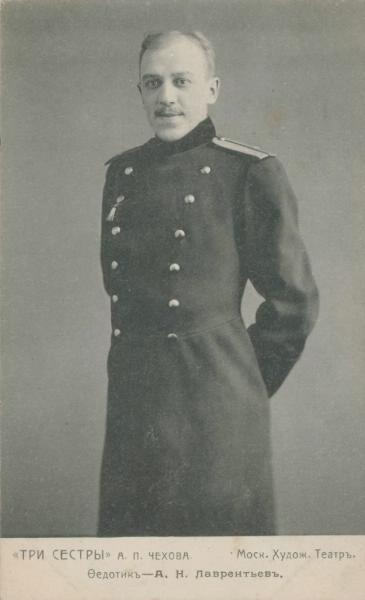

Perhaps because of the preassures of the revolution [Marianne later revealed that her life with Nikolai was marked by poverty], this marriage was even shorter than the others and, by 1918, she was already in a relationship with Andrei Nikolaevich Lavrentiev, a Russian actor and theater director.

According to her mother’s recollections, Marianne warned her family several times about the impending arrest, having received information from a commissar who was infatuated with her. “She was quick, … tactfully and easily met Kuzmin. He fell madly in love with her. And he freed us for her sake,” wrote Olga Paley. On August 9, 1918, the Danish envoy H. Scavenius proposed a plan through Marianne to save the Grand Duke: Pavel Alexandrovich, dressed in an Austro-Hungarian uniform, was to hide in the Austro-Hungarian embassy, but the latter refused to change into the uniform of a state hostile to the Russian Empire. Despite all her efforts, she still failed to save her family.

After the death of her son and husband, Olga Valerianovna and her younger daughters illegally emigrated to Finland with the assistance of P. P. Durnovo, Marianna's first husband. Her father and brother Alexander left the country with their families.

Marianne, however, remained in Russia until 1921. She became an actress at the Bolshoi Theater under the stage name Maria Pavlovna in honour of her late stepfather. In 1921, she moved with her lover to Riga, where they remained for several years. In 1936, under the stage name Marianne Fiori, Marianne moved to New York and would remain in the United States until her death. In 1961, she was married for the fourth time to Mikhail Aleksandrovich Paltov, the son of chamberlain Aleksandr Aleksandrovich Paltov , formerly a captain of the Life Guards Horse Grenadier Regiment.

#romanov#paul alexandrovich#imperial russia#russian aristocracy#marianne von pistohlkors#grigori rasputin#grand duke dmitri pavlovich#prince felix yussupov#irina paley#nataie paley

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Felix Yusupov on the murder of Rasputin

As I was alone in St. Petersburg, I was staying with my brothers-in-law at the Grand Duke Alexander's palace. On December 29, I spent most of the day preparing for my examinations which were to be held next day.* As soon as I had a free moment I went home to make the final arrangements. I intended to receive Rasputin in the flat which I was fitting up in the Moika** basement: arches divided it in two; the larger half was to be used as a dining room. From the other half, the staircase which I have already mentioned led to my rooms on the floor above. Halfway up was a door opening onto the courtyard. The larger room had a low, vaulted ceiling and was lighted by two small windows which were on a level with the ground and looked out on the Moika. The walls were of grey stone, the flooring of granite. To avoid arousing Rasputin's suspicions - for he might have been surprised at being received in a bare cellar - it was indispensable that the room should be furnished and appear to be lived in. When I arrived, I found workmen busy laying down carpets and putting up curtains. Three large red Chinese porcelain vases had already been placed in niches hollowed out of the walls. Various objects which I had selected were being carried in: carved wooden chairs of oak, small tables covered with ancient embroideries, ivory bowls, and a quantity of other curios. I can picture the room to this day in all its details, and I have good reason to remember a certain cabinet of inlaid ebony which was a mass of little mirrors, tiny bronze columns and secret drawers. On it stood a crucifix of rock crystal and silver, a beautiful specimen of sixteenth-century Italian workmanship. On the great red granite mantelpiece were placed golden bowls, antique majolica plates and a sculptured ivory group. A large Persian carpet covered the floor and, in a corner, in front of the ebony cabinet, lay a white bearskin rug. In the middle of the room stood the table at which Rasputin was to drink his last cup of tea.

My two servants, Grigori and Ivan, helped me to arrange the furniture. I asked them to prepare tea for six, to buy biscuits and cakes and to bring wine from the cellar. I told them that I was expecting some friends at eleven that evening, and that they could wait in the servants' hall until I rang for them. When everything was settled I went up to my room where Colonel Vogel, my crammer, was waiting to coach me for the last time before my exams. The lesson was over by six o'clock; before going back to dine with my brothers-in-law, I went into the church of Our Lady of Kazan. Deep in prayer, I lost all sense of time. When I left the cathedral after what seemed to me but a few moments, I was astonished to find I had been there almost two hours. I had a strange feeling of lightness, of well-being, almost of happiness... I hurried to my father-in-law's palace where I had a light dinner before returning to the Moika. By eleven o'clock everything was ready in the basement. Comfortably furnished and well-lighted, this underground room had lost its grim look. On the table the samovar smoked, surrounded by plates filled with the cakes and dainties that Rasputin liked so much. An array of bottles and glasses stood on a sideboard. Ancient lanterns of coloured glass lighted the room from the ceiling; the heavy red damask portieres were lowered. On the granite hearth, a log fire crackled and scattered sparks on the flagstones. One felt isolated from the rest of the world and it seemed as though, no matter what happened, the events of that night would remain forever buried in the silence of those thick walls.

The bell rang, announcing the arrival of Dmitri and my other friends. I showed them into the dining room and they stood for a little while, silently examining the spot where Rasputin was to meet his end. I took from the ebony cabinet a box containing the poison and laid it on the table. Dr. Lazovert put on rubber gloves and ground the cyanide of potassium crystals to powder. Then, lifting the top of each cake, be sprinkled the inside with a dose of poison which, according to him, was sufficient to kill several men instantly. There was an impressive silence. We all followed the doctor's movements with emotion. There remained the glasses into which cyanide was to be poured. It was decided to do this at the last moment so that the poison should not evaporate and lose its potency. We had to give the impression of having just finished supper - for I had warned Rasputin that when we had guests we took our meals in the basement and that I sometimes stayed there alone to read or work while my friends went upstairs to smoke in my study. So we disarranged the table, pushed the chairs back, and poured tea into the cups. It was agreed that when I went to fetch the starets, Dmitri, Purishkevich and Sukhotin would go upstairs and play the gramophone, choosing lively tunes. I wanted to keep Rasputin in a good humor and remove any distrust that might be lurking in his mind.

When everything was ready, I put on an overcoat and drew a fur cap over my ears, completely concealing my face. Doctor Lazovert, in a chauffeur's uniform, started up the engine and we got into the car which was waiting in the courtyard by the side entrance. On reaching Rasputin's house, I had to parley with the janitor before he agreed to let me in. In accordance with Rasputin's instructions, I went up the back staircase; I had to grope my way up in the dark, and only with the greatest difficulty found the starets' door. I rang the bell. "Who's that?" called a voice from inside. I began to tremble. "It's I, Grigori Yefimovitch. I've come for you. I could hear Rasputin moving about the hall. The chain was unfastened, the heavy lock grated. I felt very ill at ease. He opened the door and I went into the kitchen. It was dark. I imagined that someone was spying on me from the next room. Instinctively, I turned up my collar and pulled my cap down over my eyes. "Why are you trying to hide?" asked Rasputin. "Didn't we agree that no one was to know you were going out with me tonight?" "True, true; I haven't said a word about it to anyone in the house, I've even sent away all the tainiks.(* Members of the secret police.) I'll go and dress." I accompanied him to his bedroom; it was lighted only by the little lamp burning before the icons. Rasputin lit a candle; I noticed that his bed was crumpled. He had probably been resting. Near the bed were his overcoat and beaver cap, and his high feltlined galoshes. Rasputin wore a silk blouse embroidered in cornflowers, with a thick raspberry-colored cord as a belt. His velvet breeches and highly polished boots seemed brand-new; he had brushed his hair and carefully combed his beard. As be came close to me, I smelled a strong odor of cheap soap which indicated that he had taken pains with his appearance. I had never seen him look so clean and tidy. "Well, Grigori Yefimovich, it's time to go; it's past midnight." "What about the gypsies? Shall we pay them a visit?" "I don't know; perhaps," I answered. "There will be no one at your house but us tonight?" be asked, with a note of anxiety in his voice. I reassured him by saying that he would meet no one that he might not care to see, and that my mother was in the Crimea. "I don't like your mother. I know she hates me; she's a friend of [Grand Duchess] Elisabeth's. Both of them plot against me and spread slander about me too. The Tsarina herself has often told me that they were my worst enemies. Why, no earlier than this evening, Protopopov came to see me and made me swear not to go out for a few days. 'They'll kill you,' he declared. 'Your enemies are bent on mischief!' But they'd just be wasting time and trouble; they won't succeed, they are not powerful enough ... But that's enough, come on, let's go..." I picked up the overcoat and helped him on with it. Suddenly, a feeling of great pity for the man swept over me. I was ashamed of the despicable deceit, the horrible trickery to which I was obliged to resort. At that moment I was filled with self-contempt, and wondered how I could even have thought of such a cowardly crime. I could not understand how I had brought myself to decide on it. I looked at my victim with dread, as he stood before me, quiet and trusting. What had become of his second sight? What good did his gift of foretelling the future do him? Of what use was his faculty for reading the thoughts of others, if he was blind to the dreadful trap that was laid for him? It seemed as though fate had clouded his mind... to allow justice to deal with him according to his desserts... But suddenly, in a lightning flash of memory, I seemed to recall every stage of Rasputin's infamous life. My qualms of conscience disappeared, making room for a firm determination to complete my task. We walked to the dark landing, and Rasputin closed the door behind him.

Once more I heard the grating of the lock echoing down the staircase; we were in pitch-black darkness. I felt fingers roughly clutching at my hand. "I will show you the way," said the starets dragging me down the stairs. His grip hurt me, I felt like crying out and breaking away, but a sort of numbness came over me. I don't remember what he said to me, or whether I answered him; my one thought was to be out of the dark house as quickly as possible, to get back to the light, and to free myself from that hateful clutch. As soon as we were outside, my fears vanished and I recovered my self-control. We entered the car and drove off. I looked behind us to see whether the police were following; but there was no one, the streets were deserted. We drove a roundabout way to the Moika, entered the courtyard and, once more, the car drew up at the side entrance.

As we entered the house, I could hear my friends talking while the gramophone played "Yankee Doodle went to town." "What's all this?" asked Rasputin. "Is someone giving a party here?" "No, just my wife entertaining a few friends; they'll be going soon. Meanwhile, let's have a cup of tea in the dining room." We went down to the basement. As soon as Rasputin entered the room, he took off his overcoat and began inspecting the furniture with great interest. He was particularly fascinated by the little ebony cabinet, and took a childlike pleasure in opening and shutting the drawers, exploring it inside and out. Then, at the fateful moment, I made a last attempt to persuade him to leave St. Petersburg. His refusal sealed his fate. I offered him wine and tea; to my great disappointment, he refused both. Had something made him suspicious? I was determined, come what may, that he should not leave the house alive. We sat down at the table and began to talk. We reviewed our mutual acquaintances, not forgetting Anna Vyrubova and, naturally, touched on Tsarskoe-Selo. "Grigori Yefimovitch," I asked, "why did Protopopov come to see you? Is he still afraid of a conspiracy?" "Why yes, my dear boy, he is; it seems that my plain speaking annoys a lot of people. The aristocrats can't get used to the idea that a humble peasant should be welcome at the Imperial Palace. ...They are consumed with envy and fury... but I'm not afraid of them. They can't do anything to me. I'm protected against ill fortune. There have been several attempts on my life but the Lord has always frustrated these plots. Disaster will come to anyone who lifts a finger against me." Rasputin's words echoed ominously through the very room in which he was to die, but nothing could deter me now. While he talked, my one idea was to make him drink some wine and eat the cakes.

After exhausting his customary topics of conversion, Rasputin asked for some tea. I immediately poured out a cup and handed him a plate of biscuits. Why was it that I offered him the only biscuits that were not poisoned? I even hesitated before handing him the cakes sprinkled with cyanide. He refused them at first: "I don't want any, they're too sweet." At last, however, he took one, then another... I watched him, horror-stricken. The poison should have acted immediately but, to my amazement, Rasputin went on talking quite calmly. I then suggested that he should sample our Crimean wines. He once more refused. Time was passing, I was becoming nervous; in spite of his refusal, I filled two glasses. But, as in the case of the biscuits - and just as inexplicably - I again avoided using a glass containing cyanide. Rasputin changed his mind and accepted the wine I handed him. He drank it with enjoyment, found it to his taste and asked whether we made a great deal of wine in the Crimea. He seemed surprised to hear that we had cellars full of it. "Pour me out some Madeira," he said. This time I wanted to give it to him in a glass containing cyanide, but he protested: "I'll have it in the same glass." "You can't, Grigori Yefimovich," I replied. "You can't mix two kinds of wines." "It doesn't matter, I'll use the same glass, I tell you." I had to give in without pressing the point, but I managed, as if by mistake, to drop the glass from which he had drunk, and immediately poured the Madeira into a glass containing cyanide. Rasputin did not say anything. I stood watching him drink, expecting any moment to see him collapse. But he continued slowly to sip his wine like a connoisseur. His face did not change, only from time to time be put his hand to his throat as though he had some difficulty in swallowing. He rose and took a few steps. When I asked him what was the matter, he answered: "Why, nothing, just a tickling in my throat. " "The Madeira's good," he remarked; "give me some more." Meanwhile, the poison continued to have no effect, and the starets went on walking calmly about the room. I picked up another glass containing cyanide, filled it with wine and handed it to Rasputin. He drank it as he had the others, and still with no result.

There remained only one poisoned glass on the tray. Then, as I was feeling desperate, and must try to make him do as I did, I began drinking myself. A silence fell upon us as we sat facing each other, He looked at me; there was a malicious expression in his eyes, as if to say: "Now, see, you're wasting your time, you can't do anything to me." Suddenly his expression changed to one of fierce anger; I had never seen him look so terrifying. He fixed his fiendish eyes on me, and at that moment I was filled with such hatred that I wanted to leap at him and strangle him with my bare hands. The silence became ominous. I had the feeling that he knew why I had brought him to my house, and what I had set out to do. We seemed to be engaged in a strange and terrible struggle. Another moment and I would have been beaten, annihilated. Under Rasputin's heavy gaze, I felt all my self-possession leaving me; an indescribable numbness came over me, my head swam...

When I came to myself, he was still seated in the same place, his head in his hands. I could not see his eyes. I had got back my self-control, and offered him another cup of tea. "Pour me a cup," he said in a muffled voice, "I'm very thirsty." He raised his head, his eyes were dull and I thought he avoided looking at me. While I poured the tea, he rose and began walking up and down. Catching sight of my guitar which I had left on a chair, be said: "Play something cheerful, I like listening to your singing." I found it difficult to sing anything at such a moment, especially anything cheerful. "I really don't feel up to it," I said. However, I took the guitar and sang a sad Russian ditty. He sat down and at first listened attentively; then his head drooped and his eyes closed. I thought he was dozing. When I finished the song, he opened his eyes and looked gloomily at me: "Sing another. I'm very fond of this kind of music and you put so much soul into it." I sang once more but I did not recognize my own voice. Time went by; the clock said two-thirty... the nightmare had lasted two interminable hours. What would happen, I thought, if I had lost my nerve? Upstairs my friends were evidently growing impatient, to judge by the racket they made. I was afraid that they might be unable to bear the suspense any longer and just come bursting in. Rasputin raised his head: "What's all that noise?" "Probably the guests leaving," I answered. "I'll go and see what's up." In my study, Dmitri, Purishkevich and Sukhotin rushed at me, and plied me with questions. "Well, have you done it? Is it over?" "The poison hasn't acted," I replied. They stared at me in amazement. "It's impossible!" cried the Grand Duke.

"But the dose was enormous! Did he take the whole lot?" asked the others. "Every bit," I answered. After a short discussion, we agreed to go down in a body, throw ourselves on Rasputin and strangle him. We were already on the way down, when I was brought to a halt by the fear that we would ruin the whole scheme by our precipitation: the sudden appearance of a lot of strangers would certainly arouse Rasputin's suspicions. And who could tell what such a diabolical person was capable of doing? I convinced my friends with great difficulty that it would be best for me to act alone. I took Dmitri's revolver and went back to the basement. Rasputin sat where I had left him; his head drooping and his breathing labored. I went up quietly and sat down by him, but he paid no attention to me. After a few minutes of horrible silence, he slowly lifted his head and turned vacant eyes in my direction. "Are you feeling ill?" I asked. "Yes, my head is heavy and I've a burning sensation in my stomach. Give me another little glass of wine. It'll do me good." I handed him some Madeira; he drank it at a gulp; it revived him and he recovered his spirits. I saw that he was himself again and that his brain was functioning quite normally. Suddenly he suggested that we should go to the gypsies together. I refused, giving the lateness of the hour as an excuse. "That doesn't matter," he said. "They're quite used to that; sometimes they wait up for me all night. I'm often detained at Tsarskoe Selo by important business, or simply to talk about God.... When this happens I drive straight to the gypsies in a car. The body, too, needs a rest... isn't it so? All our thoughts belong to God, they are His, but our bodies belong to ourselves: That's the way it is!" added Rasputin with a wink. I certainly did not expect to hear such talk from a man who had just swallowed an enormous dose of poison. I was particularly struck by the fact that Rasputin, who had a quite remarkable gift of intuition, should be so far from realizing that he was near death. How was it that his piercing eyes had not noticed that I was holding a revolver behind my back, ready to point it at him? I turned my head and saw the crystal crucifix. I rose to look at it more closely. "What are you staring at that crucifix for?" asked Rasputin. "I like it," I replied, "it's so beautiful." "It is indeed beautiful," he said. "It must have cost a lot. How much did you pay for it?" As he spoke, he took a few steps toward me and, without waiting for an answer, added: "For my part, I like the cabinet better." He went up to it, opened it and started to examine it again. "Grigori Yefimovich," I said, "you'd far better look at the crucifix and say a prayer."

Rasputin cast a surprised, almost frightened glance at me. I read in it an expression which I had never known him to have: it was at once gentle and submissive. He came quite close to me and looked me full in the face. It was as though he had at last read something in my eyes, something he had not expected to find. I realized that the hour had come. "O Lord," I prayed, "give me the strength to finish it." Rasputin stood before me motionless, his head bent and his eyes on the crucifix. I slowly raised the revolver. Where should I aim, at the temple or at the heart? A shudder swept over me; my arm grew rigid, I aimed at his heart and pulled the trigger. Rasputin gave a wild scream and crumpled up on the bearskin. For a moment I was appalled to discover how easy it was to kill a man. A flick of the finger and what had been a living, breathing man only a second before, now lay on the floor like a broken doll. On hearing the shot my friends rushed in, but in their frantic haste they brushed against the switch and turned out the light. Someone bumped into me and cried out; I stood motionless for fear of treading on the body. At last, someone turned the light on. Rasputin lay on his back. His features twitched in nervous spasms; his hands were clenched, his eyes closed. A bloodstain was spreading on his silk blouse. A few moments later all movement ceased. We bent over his body to examine it. The doctor declared that the bullet had struck him in the region of the heart. There was no possibility of doubt: Rasputin was dead. Dmitri and Purishkevich lifted him from the bearskin and laid him on the flagstones. We turned off the light and went up to my room, after locking the basement door.

Our hearts were full of hope, for we were convinced that what had just taken place would save Russia and the dynasty from ruin and dishonor. In accordance with our plan, Dmitri, Sukhotin and the Doctor were to pretend to take Rasputin back to his house, in case the secret police had followed us without our knowing it. Sukhotin was to pass himself off as the starets and, wearing Rasputin's overcoat and cap, would drive off in Purishkevich's open car along with Dmitri and the Doctor. They were to return to the Moika in the Grand Duke's closed car, after which they would take the body to Petrovsky Island. Purishkevich and I remained at the Moika. While we waited for our friends, we talked of the future of our country, now that it was freed once and for all from its evil genius. How could we foresee that those who ought to have seized this unique opportunity would not have the will, or the skill, to do so?

As we talked I was suddenly filled with a vague misgiving; an irresistible impulse forced me to go down to the basement. Rasputin lay exactly where we had left him. I felt his pulse: not a beat, he was dead. Scarcely knowing what I was doing I seized the corpse by the arms and shook it violently. It leaned to one side and fell back. I was just about to go, when I suddenly noticed an almost imperceptible quivering of his left eyelid. I bent over and watched him closely; slight tremors contracted his face. All of a sudden, I saw the left eye open... A few seconds later his right eyelid began to quiver, then opened. I then saw both eyes - the green eyes of a viper - staring at me with an expression of diabolical hatred. The blood ran cold in my veins. My muscles turned to stone. I wanted to run away, to call for help, but my legs refused to obey me and not a sound came from my throat. I stood rooted to the flagstones as if caught in the toils of a nightmare. Then a terrible thing happened: with a sudden violent effort Rasputin leapt to his feet, foaming at the mouth. A wild roar echoed through the vaulted rooms, and his hands convulsively thrashed the air. He rushed at me, trying to get at my throat, and sank his fingers into my shoulder like steel claws. His eyes were bursting from their sockets, blood oozed from his lips. And all the time he called me by name, in a low raucous voice. No words can express the horror I felt. I tried to free myself but was powerless in his vicelike grip. A ferocious struggle began.... This devil who was dying of poison, who had a bullet in his heart, must have been raised from the dead by the powers of evil. There was something appalling and monstrous in his diabolical refusal to die. I realized now who Rasputin really was. It was the reincarnation of Satan himself who held me in his clutches and would never let me go till my dying day. By a superhuman effort I succeeded in freeing myself from his grasp. He fell on his back, gasping horribly and still holding in his hand the epaulette he had torn from my tunic during our struggle. For a while he lay motionless on the floor. Then after a few seconds, he moved. I rushed upstairs and called Purishkevich, who was in my study. "Quick, quick, come down!" I cried. "He's still alive!"

At that moment, I heard a noise behind me; I seized the rubber club Maklakov had given me (he had said: "one never knows") and rushed downstairs, followed by Purishkevich, revolver in hand. We found Rasputin climbing the stairs. He was crawling on hands and knees, gasping and roaring like a wounded animal. He gave a desperate leap and managed to reach the secret door which led into the courtyard. Knowing that the door was locked, I waited on the landing above, grasping my rubber club. To my horror and amazement, I saw the door open and Rasputin disappear. Purishkevich sprang after him. Two shots echoed through the night. The idea that he might escape was intolerable! Rushing out of the house by the main entrance, I ran along the Moika to cut him off in case Purishkevich had missed him. The courtyard had three entrances, but only the middle one was unlocked. Through the iron railings, I could see Rasputin making straight for it. I heard a third shot, then a fourth... I saw Rasputin totter and fall beside a heap of snow, Purishkevich ran up to him, stood for a few seconds looking at the body, then, having made sure that this time all was over, went swiftly into the house. I called, but he did not hear me. The quay and the adjacent streets were deserted; apparently the shots had not been heard. When I had reassured myself on this point, I entered the courtyard and went up to the snow-heap behind which lay Rasputin. He gave no sign of life.

But, at that moment, I saw two of my servants running up from one side and a policeman from the other. I went up to the policeman and spoke to him; I stood so as to make him turn his back to the spot where Rasputin lay. "Your Highness," he said on recognizing me, "I heard revolver shots. What has happened?" "Nothing of any consequence," I replied, "just a little horseplay. I gave a small party this evening and one of my friends who had drunk a little too much amused himself by firing his revolver into the air. If anyone questions you, just say that everything's all right, and that there is no harm done!" As I spoke, I led him to the gate. I then returned to the corpse by which the two servants were standing. Rasputin's body still lay in a crumpled heap on the same spot, but his position had changed. My God, I thought, can he still be alive? I was terror-stricken at the bare thought that he might suddenly get up again. I ran toward the house, calling Purishkevich, who had disappeared indoors. I felt sick, and Rasputin's hollow voice calling my name still rang in my ears. Staggering to my dressing room, I drank a glass of water. At that moment Purishkevich entered the room: "Ah! there you are! I've been looking for you everywhere!" he cried. My sight was blurred, I thought I was going to faint. Purishkevich helped me to my study. We had scarcely reached it when my manservant came to say that the policeman I had talked to a few moments before wished to see me again. The shots, it seems, had been heard from the police station, and my constable, whose beat it was, had been sent for to make a report on what had happened. As his version of the affair was considered unsatisfactory, the police insisted on fuller details. When the constable entered the room, Purishkevich addressed him in a loud voice: "Have you ever heard of Rasputin? The man who plotted to ruin our country, the Tsar and your brother-soldiers? The man who betrayed us to Germany, do you hear?" Not understanding what was expected of him, the policeman remained silent. "Do you know who I am?" continued Purishkevich. "I am Vladimir Mitrophanovich Purishkevich, member of the Duma. The shots you heard killed Rasputin. If you love your country and your Tsar, you'll keep your mouth shut." I listened with horror to this amazing statement, which came so unexpectedly that I had no chance to interrupt. Purishkevich was in such a state of excitement that he did not realize what he was saying. Finally, the policeman spoke: "You did right and I won't say a word unless I'm put on oath. I would then have to tell the truth as it would be a sin to lie." Purishkevich followed him out.

My manservant then informed me that Rasputin's body had been placed on the lower landing of the staircase. I felt very ill, my head swam and I could scarcely walk. I rose with difficulty, automatically picked up my rubber club, and left the study. As I reached the top of the stairs, I saw Rasputin stretched out on the landing, blood flowing from his many wounds. It was a loathsome sight. Suddenly, everything went black, I felt the ground slipping from under my feet and I fell headlong down the stairs. Purishkevich and Ivan found me, a few minutes later, lying side by side with Rasputin; the murderer and his victim. I was unconscious and he and Ivan had to carry me to my bedroom. Meanwhile Dmitri, Sukhotin and Doctor Lazovert came back in a closed car to fetch Rasputin's body. When Purishkevich told them what had happened, they decided to let me rest and go off without me. They wrapped the corpse in a piece of heavy linen, shoved it into the car, and drove to Petrovsky Island. There, from the top of the bridge, they hurled it into the river. On regaining consciousness I felt as though I had just recovered from a serious illness. The air I breathed in so deeply seemed fresh, clean and pure, as after a storm. I seemed to come to life again.

With the help of my servant I washed up all traces of blood which might give us away. When everything was in order I walked out into the courtyard... I had to think of some story to explain the revolver shots. This is what I decided to say: one of my guests while considerably the worse for liquor had tried to shoot one of our watchdogs in the courtyard when he was leaving. I then sent for the two servants who had seen the end of the tragedy and explained what had really happened. They listened in silence and promised to keep my secret. It was almost five in the morning when I left the Moika to return to the Grand Duke Alexander's palace. I felt full of courage and confidence at the thought that the first steps to save Russia had been taken. I found my brother-in-law Fyodor in my room. He had spent a sleepless night, anxiously waiting for me to come back. "Thank God you are here at last," he said. "Well?" "Rasputin is dead," I replied, "but I'm not in a fit state to talk about it; I am dropping with fatigue." Realising that I would need all my strength on the morrow to face the cross-examinations, the investigations, and perhaps even worse, I went to bed and at once fell into a deep sleep.

*Felix Yusupov was undergoing military training at the Corps des Pages at the time of the murder.

**the Yusupov palace on the Moika canal.

source: Lost Splendour by Felix Yusupov, chapter 23

#felix yusupov#imperial russia#history#rasputin#grigori rasputin#murder of rasputin#grand duke dmitri pavlovich#dmitri pavlovich

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

There are four individuals I do not recognize. Actually, this is an impressive gathering of Grand Dukes and Duchesses. I have included all the names of individuals in the group that I recognize on the tags.

Emperor Alexander III surrounded by family

#Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich#Grand Duke Sergei Mikhailovich#Grand Duke Nikolay Nikolaevich#Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich#Grand Duke Dmitry Konstantinovich#Duke Peter of Oldenburg#Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna#Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna the Elder#Grand Duchess Helena Vladimirovna#Grand Duchess Alexandra Iosifovna#Empress Maria Alexandrovna#Emperor Alexander III#Grand Duke Mikhail Nikolaievich#Grand Duke Pavel Alexandrovich#Grand Duke Alexey Mikhailovich#Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich#Grand Duke Andre Vladimirovich#Grand Duke Boris Vladimirovich#Olga

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

Photographs: 1. Grand Duke Pavel Alexandrovich; 2. Pavel's first wife: Grand Duchess Alexandra Georgievna (Nee Princess Alexandra of Greece and Denmark); 3. Pavel's morganatic wife: Olga Valerianovna, Princess Paley (nee Olga Valerianovna Karnovich).

Grand Duke Pavel Alexandrovich (1860 - 1919) and his children

Grand Duke Pavel was the youngest son of Emperor Alexander II and Empress Maria Alexandrovna. As a child and even as an adult, he had very frail health (but that did not prevent him from being very successful with the ladies and a great dancer.) Politically, Pavel would play his most important role toward the end of the Romanov dynasty, when he largely acted as a liaison between Empress Alexandra and Emperor Nicholas II and the rest of the Romanov family. It was Grand Duke Paul who informed the Empress of the abdication.

Pavel was married twice and had five children. His first wife was Grand Duchess Alexandra Georgievna (nee Princess Alexandra of Greece and Denmark.) He had two children with her, Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna (the younger) and Grand Duke Dmitry Pavlovich (Alexandra died giving birth to him.) Several years later, Pavel married Olga Valerianovna Karnovich morganatically and was exiled from Russia by the Emperor; the couple had a comfortable exile since Paul had money out of Russia. Olga would be made Princess Paley when the couple was allowed to return to Russia. By the time they returned to Russia, they had three children: Vladimir, Irina, and Natalia.

Grand Duke Pavel's five children were remarkably good-looking. One of his daughters, Natalia, became a model and actress in the United States. It is a shame that they had to live through such horrible times; none of them seem to find lasting stability in the area of relationships throughout their lives. But this post is just about what a good example of the general good looks of the Romanov family Pavel's children were.

Following are some photographs of Pavel's beautiful offspring:

Photographs: Pavel and Olga's children: 1. Prince Vladimir Pavlovich Paley; 2. Princesses Natalia and Irina Pavlovna Paley; 3. Prince Vladimir with his two little sisters; 4. Prince Vladimir; 5. Princess Irina Pavlovna; 6. Princess Natalia Pavlovna

Photographs: Pavel and Alexandra's children: 1. Grand Duke Dmitry Pavlovich and Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna the Younger; 2. Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna; 3. Grand Duke Dmitry Pavlovich

#russian history#romanov dynasty#Grand Duchess Alexandra Georgievna#Grand Duke Pavel Alexandrovich#Grand Duke Dmitry Pavlovich#Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna the Younger#Princess Olga Valerianovna Paley#Prince Vladimir Pavlovich Paley#Princess Natalia Pavlovna Paley#Princess Irina Pavlovna Paley

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich of Russia, Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna of Russia, with 2 children of Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich of Russia: Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna of Russia and Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich of Russia

Russian vintage postcard

#old#postcard#paul alexandrovich#duchess#children#postkaart#russian#maria pavlovna#dmitri#vintage#dmitri pavlovich#briefkaart#duke#postal#ansichtskarte#sergei#ephemera#grand duchess#paul#photography#2#elizabeth#photo#alexandrovich#feodorovna#postkarte#tarjeta#elizabeth feodorovna#russia#sergei alexandrovich

6 notes

·

View notes