#giovanni di lorenzo de medici

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

BROTHERS IN MEDICI DESERVE BETTER

#you cant tell me they didnt love one another#fight me history#giovanni di lorenzo de medici#piero di lorenzo de medici#lorenzo#lorenzo the magnificent#lorenzo the elder#cosimo#francesco pazzi#guglielmo de pazzi#giuliano de medici#i medici

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Parents

Lorenzo the Magnificent

Clarice Orsini

The Children

Piero The Unfortunate

Maddalena Daughter of the Magnificent

Giovanni, Pope Leo X

#my fave family#beautiful#clarice and lorenzo#lorenzo il magnifico#lorenzo de medici#lorenzo the magnificent#clarice orsini#more than a wife {clarice orsini}#piero the unfortunate#piero di lorenzo#piero de medici#maddalena de medici#maddalena#daughter of the magnificent {maddalena}#giovanni de medici#giovanni di lorenzo#giovanni pope leo#pope leo x

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Average fiorentino a Roma be like prima ce ne andiamo da questa fogna meglio è

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Giovanni Pico della Mirandola morì avvelenato? Analisi di un mistero storico

La morte di Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, avvenuta l'17 novembre 1494, è stata a lungo oggetto di discussione e mistero.

La morte di Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, avvenuta l’17 novembre 1494, è stata a lungo oggetto di discussione e mistero. Secondo le fonti storiche, Pico della Mirandola morì a soli 31 anni, apparentemente per cause naturali. Tuttavia, nei secoli successivi sono emerse ipotesi che suggeriscono la possibilità di avvelenamento. Le circostanze della morte Pico si trovava a Firenze al momento della…

#Alessandria today#analisi forense#arsenico#arsenico nel Rinascimento#arsenico nella storia#avvelenamenti famosi#avvelenamento storico#cause della morte#cause naturali o avvelenamento#filosofia e religione#filosofia rinascimentale#Firenze rinascimentale#Giovanni Pico della Mirandola#Girolamo Savonarola#Google News#indagini scientifiche#indagini storiche#intrighi politici#intrighi rinascimentali#italianewsmedia.com#leggende del Rinascimento#Lorenzo de&039; Medici#Medici e Pico#Medici e politica#misteri del Rinascimento#Misteri Irrisolti#misteri storici#morte di Pico della Mirandola#pensatori rivoluzionari#pensiero filosofico

0 notes

Text

Ergo Proxy Opening: In search for the artwork's source

Ergo Proxy's Opening is a fascinating piece of artwork characterized by it's kaleidoscopic mix of scenery, images from the series and subtle references to pieces of art and literature. The whole design reminds me a bit of the style of Kyle Cooper in intro sequences like Se7en . Some are very clear while others are quite cryptic and frankly unreadable. This post will summarize a few of those references and their sources:

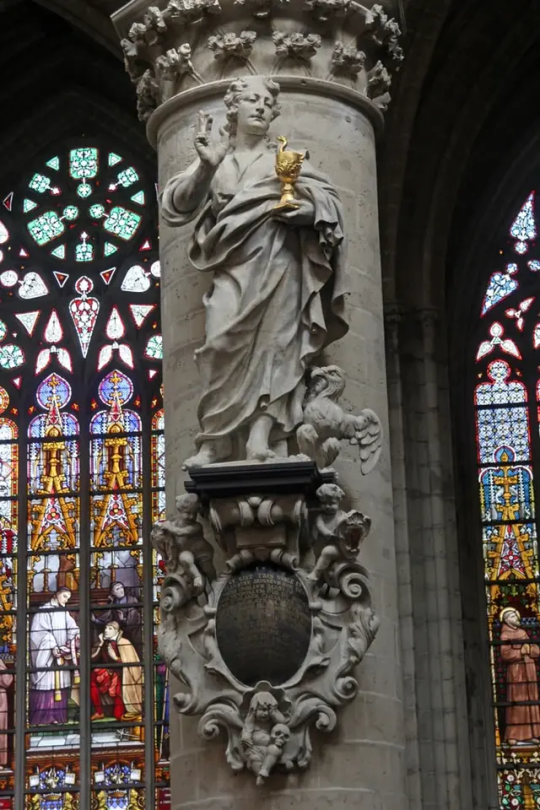

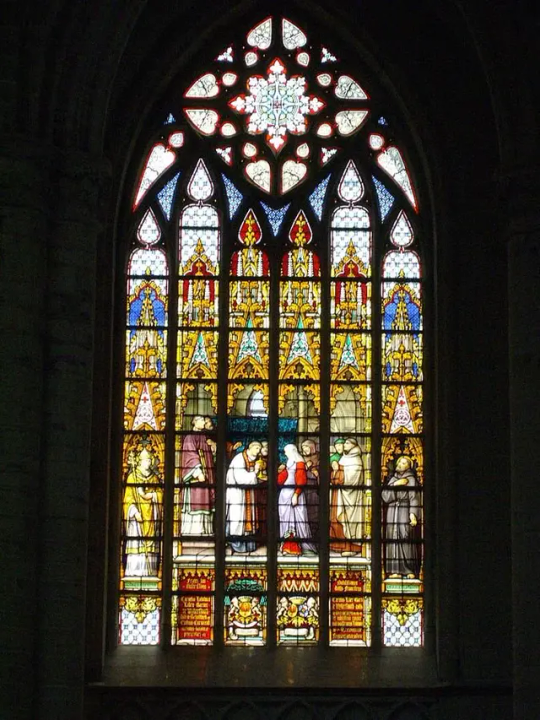

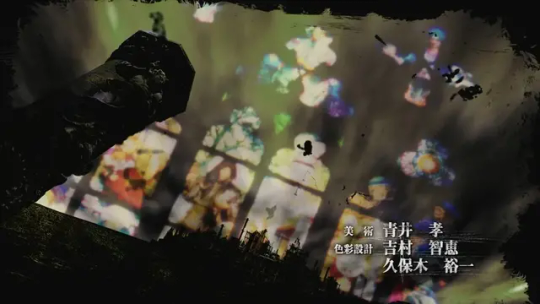

Holy Images

First we have the apparition of some glass panels and a statue in a column, and the image of some industrial complex. The statue have a chalice and appears to be a young man, and an eagle at his feet. Those are the attributes of Saint John the Younger. With that in mind, the search was easier... and after almost 14 hours of reading and searching, I found two of the three artworks.

Both the statue and the stained glass comes from the The Cathédrale Saints-Michel-et-Gudule at Brussels.

Stained Glass, probably made by Jean-Baptiste Capronnier (c. 1870):

Another decorated window appears, this time with a more modern artwork. The decorated window was designed by Alfons Mucha, c. 1930, for the reconstruction work for St. Vitas Cathedral in Prague.

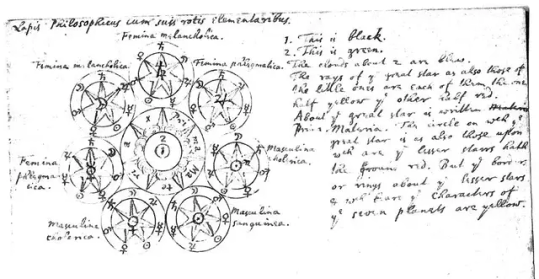

The Power of Seven and the Lapis Philosoficus

The occasional image of complex astrological or alchemical heptagrams flashes many times during the opening, being this one the most clear snap I could get. The text in the center of it reads "Ma Te Ri A Pri Ma *" that confirms the alchemical nature of the illustration.

After many attempts to find the source of the illustration i had to dive into my older alchemy notes. Suddenly I remember the works of a notorious alchemist obsessed with number seven, none other than Sir Isaac Newton. And Eureka!

the image comes from a set of notes on the processes behind the achievement of the philosopher's stone, titled "Lapis Philosophicus cum suis rotis elementaribus" and dated to c. 1690

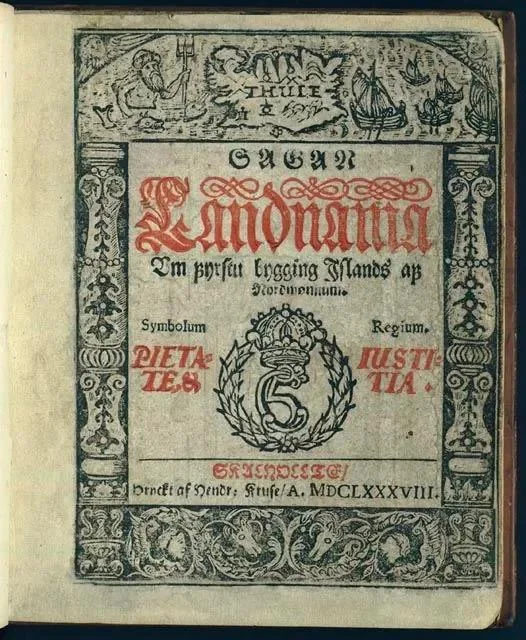

Landnámabók

Some of the decorations that appears on the opening comes directly from the icelandic text of settlers, a medieval Icelandic written work which describes in considerable detail the settlement (landnám) of Iceland by the Norse in the 9th and 10th centuries CE.

La Glorification de l'Art

This one was relatively easy to find. It is a quite common allegorical representation.

The building housing the Royal Museum of Ancient Art in Brussels is a masterpiece designed by Alphonse Balat, the Court's favorite architect, the sculpture flanking the main entrance is the work of Paul de Vigne, and was made around 1885. La Glorification de l'Art depicts Art as a winged youth, accompanied by Glory and Fame. It also appears on the opening. Art, represented by a winged man, receives from the hand of Glory a palm and a crown; while the Fame, with trumpet and bumper, publishes her exploits.

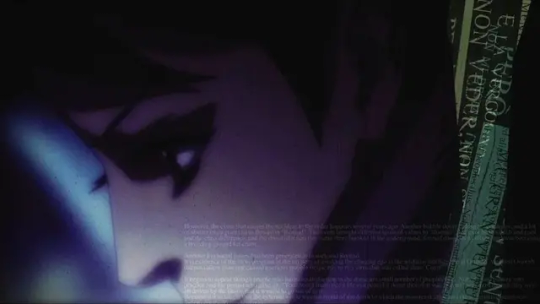

Rhyme 247

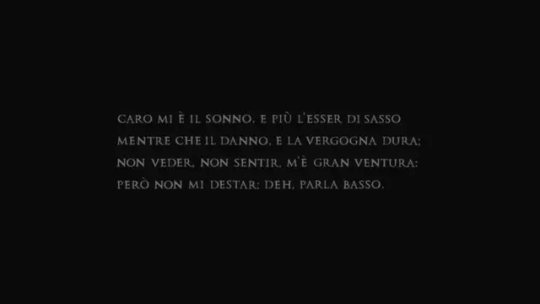

notice the words on the right side of the screenshot: "e vero", "Non Veder" "Gran Ventura"

Michelangelo Buonarroti was an exceptionally good artist, and a passionate poet too, even when he preferred to keep most of his literary production quite obscure. One of his works for the Sagrestía Nuova at the Medici Chapel in Florence was a representation of the Night, placed over the tomb of Giuliano di Lorenzo de' Medici, Duke of Nemours. Night was singularly praised by his contemporaries, especially Giovanni Strozzi, who dedicated an epigram on 1544:

La Notte che tu vedi in sì dolci attidormire, fu da un Angelo scolpitain questo sasso e, perché dorme, ha vita:destala, se nol credi, e parleratti.

Michelangelo responded in another epigram, today known as Rhyme 247:

Caro m'è 'l sonno, e più l'esser di sasso,mentre che 'l danno e la vergogna dura;non veder, non sentir m'è gran ventura; però non mi destar, deh, parla basso

This Rhyme appears on Ergo Proxy in another occasion:

The poem as appears on the beginning of the first episode

NIGHT DAWN DAY DUSK

Donov Mayer's Collective Entourage are embodied by the four sculptures from the allegorical monument (Sagrestía Nuova) of Michellangelo. A pair of the statues were located over the sarcophagus of Giuliano de' Medici, (Day and the Night) and Lorenzo de' Medici (Dusk (or Twilight) and the Dawn) respectively. On the series, each have the name of one prominent occidental philosopher:

Lacan: as Night, Voiced by: Atsuko Tanaka (Japanese), Barbara Goodson (English)

Derrida: as Dawn, Voiced by: Yōko Sōmi (Japanese), Melodee Spevack (English)

Husserl: as Day, Voiced by: Hidekatsu Shibata (Japanese), Michael McConnohie(English)

Berkeley: as Dusk, Voiced by: Yuu Shimaka (Japanese), Doug Stone(English)

[Unknown]

Some artworks or pieces of literature used are still unknown (for me)

The industrial landscape

The cursive text

And this arabic/persian texts

Thank you so much for reading so far

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

THIS DAY IN GAY HISTORY

based on: The White Crane Institute's 'Gay Wisdom', Gay Birthdays, Gay For Today, Famous GLBT, glbt-Gay Encylopedia, Today in Gay History, Wikipedia, and more … December 11

1475 – Pope Leo X (d.1521), born Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, was the Pope from 1513 to his death in 1521. He was the last non-priest (only a deacon) to be elected Pope. He is known for granting indulgences for those who donated to reconstruct St. Peter's Basilica and his challenging of Martin Luther's 95 Theses. He was the second son of Lorenzo de' Medici, the most famous ruler of the Florentine Republic, and Clarice Orsini. His cousin, Giulio di Giuliano de' Medici, would later succeed him as Pope Clement VII (1523-34).

Several modern historians have concluded that Leo was homosexual. Contemporary tracts and accounts such as that of Francesco Guicciardini have been found to allude to active same-sex relations - alleging Count Ludovico Rangone and Galeotto Malatesta were among his lovers.

Cesare Falconi has examined in particular Leo's infatuation with the Venetian noble Marcantonio Flaminio, with Leo arranging the best education that could be offered for the time. Von Pastor has argued, however, against the credibility of these testimonies, and rejected accusations of immorality as anti-papal polemic. Gucciardini was not resident at the papal court during Leo's pontificate, while other contemporaries such as Matteo Herculano took pains to praise his chastity. Paul Strathern, a British writer and academic, argues that Leo, while homosexual, was not sexually active as pope, despite identifying notable members of that family as such.

Jean Cocteau and Jean Marais

1913 – Jean Marais, French actor (d.1998); Marais was never much of an actor, and it is doubtful he would have achieved international fame had he not become Jean Cocteau's lover, but he was, by universal acclaim, one of the most handsome men ever to appear in films. In the 1940s when he made most of his movies for Cocteau, actors were still slicking down their hair with Kreml and Vitalis. But he changed all that. His cheveaux fous and athletic good looks created a new style of postwar leading man.

Cocteau and Marais

When in 1946 he spent his time in Cocteau's Beauty and the Beast, trapped within an ape-like constume, waiting for Beauty's kiss to turn him once again into Jean Marais, Gay moviegoers around the world secretly wished that they were Josette Day who actually got to kiss the handsome actor's furry face. What is perhaps most interesting about the friendship between Cocteau and Marais is that the actor's face in profile bore an astonishing resemblance to the boys Cocteau had been sketching for thirty years before meeting him.

In the 1960s, he played the famed villain of the Fantômas trilogy. After 1970, Marais's on-screen performances became few and far between, as he preferred concentrating on his stage work. He kept performing on stage until his eighties, also working as a sculptor. In 1985, he was the head of the jury at the 35th Berlin International Film Festival.

1945 – John Preston (d.1994) was an author of gay erotica and an editor of gay nonfiction anthologies.

He grew up in Medfield, Massachusetts, later living in a number of major American cities before settling in Portland, Maine in 1979. A writer of fiction and nonfiction, dealing mostly with issues in gay life, he was a pioneer in the early gay rights movement in Minneapolis. He helped found one of the earliest gay community centers in the United States, edited two newsletters devoted to sexual health, and served as editor of The Advocate in 1975.

He was the author or editor of nearly fifty books, including such erotic landmarks as Mr. Benson and I Once Had a Master and Other Tales of Erotic Love. Other works include Franny, the Queen of Provincetown (first a novel, then adapted for stage), The Big Gay Book: A Man's Survival Guide for the Nineties, Personal Dispatches: Writers Confront AIDS, and Hometowns: Gay Men Write About Where They Belong.

Preston's writing (which he described as pornography) was part of a movement in the 1970s and 1980s toward higher literary quality in gay erotic fiction. Preston was an outspoken advocate of the artistic and social worth of erotic writings, delivering a lecture at Harvard University entitled My Life as a Pornographer. The lecture was later published in an essay collection with the same name. The collection includes Preston's thoughts about the gay leather community, to which he belonged.

His writings caused controversy when he was one of several gay and lesbian authors to have their books confiscated at the border by Canada Customs. Testimony regarding the literary merit of his novel I Once Had a Master helped a Vancouver LGBT bookstore, Little Sister's Book and Art Emporium, to partially win a case against Canada Customs in the Canadian Supreme Court in 2000.

Preston also brought gay erotic fiction to mainstream readers by editing the Flesh and the Word anthologies for a major press.

Preston served as a journalist and essayist throughout his life. He wrote news articles for Drummer and other gay magazines, produced a syndicated column on gay life in Maine, and penned a column for Lambda Book Report called "Preston on Publishing." His nonfiction anthologies, which collected essays by himself and others on everyday aspects of gay and lesbian life, won him the Lambda Literary Award and the American Library Association's Stonewall Book Award. He was especially noted for his writings on New England.

In addition, Preston wrote men's adventure novels under the pseudonyms of Mike McCray, Preston MacAdam, and Jack Hilt (pen names that he shared with other authors). Taking what he had learned from authoring those books, he wrote the "Alex Kane" adventure novels about gay characters. These books, which included "Sweet Dreams," "Golden Years," and "Deadly Lies," combined action-story plots with an exploration of issues such as the problems facing gay youth.

Preston was among the first writers to popularize the genre of safe sex stories, editing a safe sex anthology entitled Hot Living in 1985. He helped to found the AIDS Project of Southern Maine. In the late 1980s, he discovered that he himself was HIV positive.

Some of his last essays, found in his nonfiction anthologies and in his posthumous collection Winter's Light, describe his struggle to come emotionally to terms with a disease that had already killed many of his friends and fellow writers.

He died of AIDS complications on April 28, 1994, aged 48, at his home in Portland.

1948 – Alvin Baltrop (d.2004) was a gay African-American photographer who earned fame through his photographs of the Hudson River piers during the 1970s and 1980s.

Baltrop was born in 1948 in the Bronx. He discovered his love of photography in junior high school. Baltrop received no formal art education; older photographers from the neighborhood taught him different techniques and how to develop photos himself.

Baltrop enlisted in the Navy as a medic during the Vietnam War and continued taking photos, mainly of his friends in sexually provocative poses. He built his own developing lab in the sick bay, using medic trays for developing trays. After his time in the Navy, Baltrop worked odd jobs as a street vendor, a jewelry designer, a printer, and a cab driver. Because he wanted to spend more time taking photos at the Hudson River piers, he quit his job as a cab driver to become a self-employed mover. He would park his van at the piers for days at a time, living out of his van to take pictures.

From 1975 through 1986, Baltrop took photographs of the West Side piers, where he was a well-known member of the community. Baltrop knew every person he photographed, and people often volunteered to be photographed. Younger boys and men at the piers often confided in him about their sexual orientation, their relationships with their families, their housing status, and their work.

Baltrop captured the gay cruising spots and hookup culture that existed in New York City before the AIDS epidemic. Baltrop's photographs not only captured human personalities, but also the aesthetics of the dilapidated piers. His life work is a snapshot of gay, African-American, and New York City history.

Baltrop struggled to make his way in the art world, facing racism from the white gay art world. Gay curators often rejected his work, accused him of stealing it, or stole his work themselves.

"Three Sailors"

Late during the 1990s, NYC artist John Drury, who knew Alvin from their shared neighborhood - Drury living on Third Street, with his wife and Baltrop on Second Street, in lower Manhattan - befriended the artist and recognized the photographers unique abilities, nominating him for a Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Award for the Arts. Alvin Baltrop had few exhibits in his lifetime; his work gaining international fame only after his death.

According to one journalist, Baltrop came out as gay at fourteen years old. Baltrop had long term relationships with men and women, but preferred identifying as gay.

Baltrop was diagnosed with cancer in the 1990s. Impoverished and without health insurance, curators and filmmakers attempted to exploit him for their own financial gain. He died on February 1, 2004

1990 – Nakshatra Bagwe, born in Mumbai, India, is an Indian actor and award winning film maker. Nakshatra will be making his Indian feature film debut in My Son is Gay and is due for his international film debut as the lead actor of Hearts. His films Logging Out, Book of Love, Curtains and PR (Public Relations) represent the current LGBT scenario of India.

He is a LGBT rights activist and also an organiser of Gujarat's first ever pride march. Nakshatra has participated in several Pride Parades in India. He won KASHISH – Mumbai International Queer Film Festival in 2012 for his debut film Logging Out. It was screened at prestigious venues like Queens Museum of Arts (New York), The Old Cinema (London) and it was also a part of Queer India European tour 2012 to raise awareness about LGBT issues in the Indian context.

Nakshatra hails from Konkan coastal region. Masure, Malvan is his native village. He takes part in homosexuality awareness projects. Nakshatra and his mother were featured in a promo of popular Indian television show Satyamev Jayte. He came out to society when he participated in Asia’s first LGBT flashmob. He also participated in second queer flashmob which happened at Dadar station, Mumbai. Nakshatra posed nude for a campaign named 'Breaking Closets'.

In July 2014, He became the brand ambassador of Moovz, a global social network for gay men. Nakshatra is first and only openly Indian LGBT person to be signed up as the brand ambassador by any brand till now.

1998 – At a meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in Denver, a resolution was passed rejecting reparative therapy. It stated that attempts to change a person's sexual orientation can cause depression, anxiety, and self-destructive behaviour. A similar resolution was passed by the American Psychological Association in August 1997. Dr. Nada Stotland, head of the association's public affairs committee, told the Denver Post that the very existence of reparative therapy spreads the idea that homosexuality is a disease or evil and has a dehumanizing effect resulting in an increase in discrimination, harassment, and violence against gays, lesbians, and bisexuals.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ages of Medici Women at First Marriage

I have only included women whose birth dates and dates of marriage are known within at least 1-2 years, therefore, this is not a comprehensive list.

This list is composed of Medici women from 1386 to 1691 CE; 38 women in total.

Piccarda Bueria, wife of Giovanni di Bicci de’ Medici: age 18 when she married Giovanni in 1386 CE

Contessina de’ Bardi, wife of Cosimo de’ Medici: age 25 when she married Cosimo in 1415 CE

Lucrezia Tornabuoni, wife of Piero di Cosimo de’ Medici: age 17 when she married Piero in 1444 CE

Bianca de’ Medici, daughter of Piero di Cosimo de’ Medici: age 14 when she married Guglielmo de’ Pazzi in 1459 CE

Lucrezia de’ Medici, daughter of Piero di Cosimo de’ Medici: age 13 when she married Bernardo Rucellai in 1461 CE

Clarice Orsini, wife of Lorenzo de’ Medici: age 16 when she married Lorenzo in 1469 CE

Caterina Sforza, wife of Giovanni de' Medici il Popolano: age 10 when she married Girolamo Riario in 1473 CE

Semiramide Appiano, wife of Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici: age 18 when she married Lorenzo in 1482 C

Lucrezia de’ Medici, daughter of Lorenzo de’ Medici: age 18 when she married Jacopo Salviati in 1488 CE

Alfonsina Orsini, wife of Piero di Lorenzo de’ Medici: age 16 when she married Piero in 1488 CE

Maddalena de’ Medici, daughter of Lorenzo de’ Medici: age 15 when she married Franceschetto Cybo in 1488 CE

Contessina de’ Medici, daughter of Lorenzo de’ Medici: age 16 when she married Piero Ridolfi in 1494 CE

Clarice de’ Medici, daughter of Piero di Lorenzo de’ Medici: age 19 when she married Filippo Strozzi the Younger in 1508 CE

Filberta of Savoy, wife of Giuliano de’ Medici: age 17 when she married Giuliano in 1515 CE

Madeleine de La Tour d’Auvergne, wife of Lorenzo II de’ Medici: age 20 when she married Lorenzo in 1518 CE

Catherine de’ Medici, daughter of Lorenzo II de’ Medici: age 14 when she married Henry II of France in 1533 CE

Margaret of Parma, wife of Alessandro de’ Medici: age 13 when she married Alessandro in 1536 CE

Eleanor of Toledo, wife of Cosimo I de’ Medici: age 17 when she married Cosimo in 1539 CE

Giulia de’ Medici, daughter of Alessandro de’ Medici: age 15 when she married Francesco Cantelmo in 1550 CE

Isabella de’ Medici, daughter of Cosimo I de’ Medici: age 16 when she married Paolo Giordano I Orsini in 1558 CE

Lucrezia de’ Medici, daughter of Cosimo I de’ Medici: age 13 when she married Alfonso II d’Este in 1558 CE

Bianca Cappello, wife of Francesco I de’ Medici: age 15 when she married Pietro Bonaventuri in 1563 CE

Joanna of Austria, wife of Francesco I de’ Medici: age 18 when she married Francesco in 1565 CE

Camilla Martelli, wife of Cosimo I de’ Medici: age 25 when she married Cosimo in 1570 CE

Eleanor de’ Medici, daughter of Francesco I de’ Medici: age 17 when she married Vincenzo I Gonzaga in 1584 CE

Virginia de’ Medici, daughter of Cosimo I de’ Medici: age 18 when she married Cesare d’Este in 1586 CE

Christina of Lorraine, wife of Ferdinando I de’ Medici: age 24 when she married Ferdinando in 1589 CE

Marie de’ Medici, daughter of Francesco I de’ Medici: age 25 when she married Henry IV of France in 1600 CE

Maria Maddalena of Austria, wife of Cosimo II de’ Medici: age 19 when she married Cosimo in 1608 CE

Caterina de’ Medici, daughter of Ferdinando I de’ Medici: age 24 when she married Ferdinando Gonzago in 1617 CE

Claudia de’ Medici, daughter of Ferdinando I de’ Medici: age 16 when she married Federico Ubaldo della Rovere in 1620 CE

Margherita de’ Medici, daughter of Cosimo II de’ Medici: age 16 when she married Odoardo Farnese in 1628 CE

Vittoria della Rovere, wife of Ferdinando II de’ Medici: age 12 when she married Ferdinando in 1634 CE

Anna de’ Medici, daughter of Cosimo II de’ Medici: age 30 when she married Ferdinand Charles of Austria in 1646 CE

Marguerite Louise d’Orleans, wife of Cosimo III de’ Medici: age 16 when she married Cosimo in 1661 CE

Violante Beatrice of Bavaria, wife of Ferdinando de’ Medici: age 16 when she married Ferdinando in 1689 CE

Anna Maria Franziska of Saxe-Lauenberg, wife of Gian Gastone de’ Medici: age 18 when she married Philipp Wilhelm of Neuberg in 1690 CE

Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici, daughter of Cosimo III de’ Medici: age 24 when she married Johann Wilhelm, Elector Palatine in 1691 CE

The average age at first marriage among these women was 17 years old.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here is how we can kill Giovanni Auditore and still win—

So, everyone who knows me know that I have a personal and deep dislike of the whole assassination of the Auditore, for a variety of reasons. First of all my suspension of disbelief ends at a process on a noble that is part of the medicean close circle being concluded, ruling for execution too, in but one night. It would be more likely for it to rule for exile, even if it happened in one night. Anyway. Second thing, you are really going to make a pivotal death in the game’s plot happen, in the kill-people-game, set in incredibly-violent-stab-stab-murders years of Italy, cushioned between the Duke of Milano being stabbed in the chest entering a church and Giuliano de’ Medici getting his head bashed in and a dozen other stab wounds in Santa Maria del Fiore, and make it something so utterly boring as a hanging? Where is the drama? Where is the visceral hatred, the centuries long hidden war intertwined with the political opposition in Firenze? Shameful, I say.

I have already ranted about the execution but I will shortly repeat it: man wasn���t getting condemned to the rope in one night. Least of all his children, and especially Petruccio. Like, that was going to be unlikely even if he were not in the favour of the current political power. But he very much is in the favour of the Medici, and even if Lorenzo were away for that day (one hour away on horseback, btw) his brother remained in Firenze, and most people involved with the trial would have been in the Medici’s pockets, loyal to them, or simply unwilling to risk going against them, I truly doubt the Templars could buy or threaten everyone. With the added point of, what guarantees Lorenzo wouldn’t have retaliated? Even if the hanging were lawful (which, it can’t be, but anyway) the Medici are very good at financially ruining people (see what happened after the congiura dei Pitti).

That being said, we have arrested Giovanni and Federico (and not Petruccio because that’s just whack, and that child shouldn’t even be in Firenze anyway, put him in the countryside for his health or so help me). Now we have the, previously mentioned arrest or Cosimo de Medici to take inspiration from, I guess: when the man was imprisoned in 1433 he refused to eat anything not given to him by his family for he feared being poisoned. Now, I don’t think you’d get to poison an Assassin, but he can still be killed in his cell.

After all, a hanging is so impersonal and clean, it’s much more satisfying to corner an imprisoned man and stab him enough times that his body has to be sewn closed for burial (that’s what happened to Giuliano, btw :3). And Federico can be made to watch, can be stabbed too, and whether he dies or not is up for discussion I guess.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Integerrimi

Racconta Tito Livio:

La censura si era resa necessaria non solo perché non si poteva più rimandare il censimento che da anni non veniva più fatto, ma anche perché i consoli, incalzati dall’incombere di tante guerre, non avevano il tempo di dedicarsi a questo ufficio. Fu presentata in senato una proposta: l’operazione, laboriosa e poco pertinente ai consoli, richiedeva una magistratura apposita, alla quale affidare i compiti di cancelleria e la custodia dei registri e che doveva stabilire le modalità del censimento. (Ab Urbe Condita, IV, 8).

La magistratura Censorea venne istituita nel 443 a.C., durante il regime repubblicano di Roma: Censura deriva da una concrezione tra CĒNSEŌ, “dare un’opinione, giudicare, valutare” e il suffisso -TŪRA, necessario per formare un sostantivo a partire da un verbo. I magistrati censori non solo facevano i censimenti (necessari sia per il sistema fiscale che per quello militare), ma erano anche guardiani della CURA MORUM, cioè i costumi del singolo e della collettività ed avevano poteri particolari: erano decisivi nelle assegnazioni degli appalti per i lavori pubblici, ed erano loro a concedere in affitto i terreni statali e avevano incarico di nominare i candidati che si potevano candidare al seggio del Senato, Massima Istituzione di Roma, nelle famose Lectio Senatus.

Il significato odierno si deve ad uno di questi poteri antichi, e ad uno rinascimentale: si racconta che i censori potevano tagliare con una cesoia apposita gli abbellimenti che ritenevano troppo distante dalla Cura Morum, tanto che come antonomasia dell'integerrimo amico della sobrietà si ricorda Marco Porcio Catone, detto il Censore, proprio per il ruolo che svolgeva al tempo.

Durante il Rinascimento, precisamente nel 1515, Papa Leone X, nato Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, secondogenito di Lorenzo Il Magnifico, emanò una bolla, Inter Sollicitudines, dove si stabilisce che essendo la stampa "inventato per la gloria di Dio, la crescita della fede e la propagazione delle scienze utili” ma con la paura che possa diventare “un ostacolo alla salvezza dei fedeli in Cristo”, decide che nessuno può stampare un libro senza l'autorizzazione del vescovo locale (o del Vicario del Papa, se si tratta di libri da stampare nello Stato della Chiesa), sotto pena di scomunica. Nasceva così l’imprimatur, ossia il visto ecclesiastico per la stampa dei libri. Di pochi anni dopo, nel 1559, è il primo Indice dei Libri Proibiti, il quale fu per l'ultima volta aggiornato nel 1959 prima del Pontificato di Papa Giovanni XXIII.

Gli uomini potrebbero fare a meno dell'arte, ma non i censori. Stanisław Jerzy Lec

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

And I have found three of Giovanni’s daughters!

A million years later Jesus Christ this man is hard to track down.

One might have been born out of wedlock when he was twenty-two? But that’s still TBC.

If I got it right, he married Maria Castellani circa 1469 (young! He would have been 25ish. Italian men in this period tended to marry a little older).

Daughters are: Lena (possible out of wedlock one), Lucrezia, and Ginevra (presumably named for his aunt).

I’ve seen sources saying he had four daughters, so we might be missing a name. TBC.

What I want to track down is the last will and testament, that would have some interesting information.

Also found his parents: Niccolò and Constanza

I believe this will be of interest to like three people, the main one being @centaurianthropology

(So that letter where Marsilio is like “I heard you had another daughter. But you haven’t officially told me so I’m congratulating you but also not? Idk man. Remember that daughters are also blessings!” That would have been for Ginevra, I think. If not her then the so-far unnamed fourth daughter.)

——

And what was our beloved philosopher up to in 1468/69?

Translating De Amore on Giovanni’s urging/recommendation of course.

From my little chronology:

1468 – Marsilio translated Dante’s De monarchia. It is said that he may have suffered a bit of a crises over his Platonic philosophising and its potential conflicts with his Christian beliefs—however, the extent of what this meant is debated. Some historians (e.g., Carol Kaske and John Clark) believe that the “famous” crises never occurred and was fabricated by his first biographer Giovanni di Bardo Corsi.

Also in 1468 Marsilio wrote/completed De amore, his commentary on Plato’s Symposium.

This was the year Lorenzo de’ Medici’s came of age. Giovanni Cavalcanti participated in the joust held in Lorenzo’s honour.

The joust is the first, formal, public mention of Giovanni Cavalcanti that we have.

1469 – Marsilio completed his translations of Plato and began his work on Platonic Theology, or, the Immortality of Souls in Eighteen Books. He also had the first Latin edition of Pimander, from the Corpus Hermeticum, published in Venice.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

DONATELLO

"Annunciazione Cavalcanti"

uno straordinario capolavoro di Donatello che è possibile ammirare all’interno della Basilica di Santa Croce, a Firenze.

L’opera realizzata in pietra serena serena dorata e in parte policroma fu commissionata all’artista da Giovanni Cavalcanti, cognato di Lorenzo de’ Medici il Vecchio, fratello di Cosimo, il Pater Patriae. Per tale ragione non è da escludere che la famiglia Medici abbia avuto un ruolo rilevante in questa commissione affidata a Donatello.

L’artista mise mano all’opera in età matura, nel 1435, poco prima di partire alla volta di Padova.

L’ubicazione originale dell’opera è ancora oggetto di dibattito tra gli studiosi.

Fonte Web

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

MWW Artwork of the Day (12/4/23) Scheggia [Giovanni di ser Giovanni Guidi](Italian, 1406–1486) The Triumph of Fame (c. 1449) Tempera, silver & gold on wood, 62.5 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Rogers Fund)

This commemorative birth tray (desco da parto), celebrates the birth of Lorenzo de' Medici (1449–1492), the most celebrated ruler of his day as well as an important poet and a major patron of the arts. Knights extend their hands in allegiance to an allegorical figure of Fame, who holds a sword and winged cupid (symbolizing celebrity through arms and love). Winged trumpets sound Fame's triumph. Captives are bound to the elaborate support. The three-colored ostrich feathers around the rim are a heraldic device of Lorenzo's father, Piero de' Medici. Painted by the younger brother of Masaccio, it was kept in Lorenzo’s private quarters in the Medici palace in Florence.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Medici Thoughts

Okay first things first, abuse its bad. Don't condone it.

So I don't agree with Lorenzo hitting Piero. Like it actually shocked me and I'm surprised Clarice didn't come back to live and hand her husband his ass right then and there for what he did.

While I don't agree with it, and it honestly...felt rather out of character for Lorenzo, also historically he had a good relationship with his kids

BUT I do see why the writers put it in, because I think it represents a lot of things.

1: It represents how lost Lorenzo is without Clarice. Like, the dude was bordering on losing it while she was still alive and her death really pushed him over the edge. He lost his way, he lost himself. He felt like an animal in a trap because he knows he's dying. The thing is, is that Clarice was supposed to survive HIM, not the other way around. Lorenzo would leave the bank and his family to her, probably one of the last people he trusts. But then she died. So he is not only mourning her but he is also panicking cause now he has to adjust his plans cause now when he dies he's gonna be leaving his children in charge of a broken Florence with no protection. He's panicking, he's freaking out and his son just did something to stop his plans, in his view to protect his family.

2: I think it shows just how much Lorenzo has changed over the years, the Pazzi Conspiracy hardened him. Lorenzo de Medici died that day, Lorenzo the Magnificent was all the remained. Lorenzo has basically been in fight or flight mode for the last several years and the dude is tired. He's done and he's losing it. (not en excuse)

3: I think it shows that in the end Lorenzo becomes something so much worse than any of his precedseeors. Worse than Giovanni, Cosimo and Piero. He was the hope and the light of the family. Now he has turned into something darker. He wanted to be better than those before him and instead he turned into something so much worse.

#medici#medici thoughts#i medici#lorenzo headcanon#lorenzo il magnifico#piero#piero the unfortunate#history thoughts#clarice orsini#cosimo de medici#giovanni di bicci#piero the gouty

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

What if scenario: Desmond dies and is reborn in AC2 and ends up somehow being betrothed to Claudia instead of Duccio. (Duccio still gets beaten up though lol) Desmond has his memories like in yew branches.

I’m sure there’s going to be at least three people (one of them being Claudia herself) who would joke that he only wants to marry Claudia to finally be Ezio’s brother. XD

Okay, in all seriousness, let’s talk about how this would work.

Betrothals during this era is quite… early. Claudia herself is betrothed to Duccio by the time she is 15 so it won’t be surprising if their betrothal happened when she was 13 or 14.

Now, you mention Yew Branches and I think that we would have an easiest way to make this happen by just kicking Desmond into a canon character that would make sense to be betrothed to Claudia.

Of course, the first target that comes to mind would be one of the Medicis, mainly because that would fortify the alliance between House Medici and House Auditore and Claudia would be marrying ‘up’ but the oldest son of Lorenzo would be Piero and he has an 11 year difference with Claudia and would be 4 when Claudia is 15.

Claudia would definitely complain and say no. Honestly, pre-tragedy Claudia feels like a girl who would be into older men because she’d think they’re sooooo mature and ‘dashing’ and ‘mysterious’. A bit of a hopeless romantic keeping her Auditore audacity at bay.

So��

May I suggest… kicking Desmond into being reborn as Lorenzo’s unfortunate will-die-in-the-Pazzi-conspiracy younger brother, Giuliano?

He would be 8 years older than Claudia but that’s fine. There are larger age gaps in Renaissance Italy (Lucrezia’s 14 year gap with Giovanni Sforza for example) and it would be funny if Claudia is actually attracted to him because he’s cool, strong and sooooo mysterious.

Desmond… Desmond just wants to save everyone, goddammit.

Also… this gives us an excuse for Desmond to have complicated feelings over having Lorenzo as his brother.

If you’re still iffy with the age gap, Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici is only 2 years older than Claudia and marrying Claudia to a branch family member of the Medici would be a better move because Lorenzo is trying to lock in the Auditores’ loyalty (and the Assassins’ support) but marrying from the main family seems a bit… ‘wasteful’.

Either way, pre-tragedy Claudia? She’d definitely be attracted to Desmond.

Post-tragedy Claudia? Yeah, she’d cling to Desmond more because she’s so lost but, once she gets her feet to the ground and starts understanding the ‘freedom’ she has in Monteriggioni, she’d probably be the one to break off the engagement (especially if this is Brotherhood!Claudia).

Desmond accepts it but, shit… He can’t believe he’s saying this but…

He…

He might have accidentally fallen in love with Claudia already???

#ezio would definitely be supportive#but also would threaten desmond that he’d kick his ass#if he ever hurts his baby sister#medici or not#desmond’s just like#dude i think claudia would kill me first#and you gotta help her hide the body#and ezio’s offended that desmond would think his baby sister is that viscious but also…#yeeaaaahh#he can see claudia being that viscious#ask and answer#assassin's creed#desmond miles#claudia auditore#ezio auditore#teecup writes/has a plot#fic idea: assassin's creed#claudes#i think that's what i use for their pairing#idk

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Giuliano de' Medici Duke of Nemours

Artist: After Raphael

Giuliano di Lorenzo de' Medici KG (12 March 1479 – 17 March 1516) was an Italian nobleman, the third son of Lorenzo the Magnificent, and a ruler of Florence.

Born in Florence, he was raised with his brothers Piero and Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, who became Pope Leo X; as well as his cousin Giulio de' Medici, who became Pope Clement VII.

His older brother Piero was briefly the ruler of Florence after Lorenzo's death, until the republican faction drove out the Medici in 1494. Giuliano moved therefore to Venice. The Medici family was restored to power after the Holy League drove the French forces that had supported the Florentine republicans from Italy. This effort was headed by Spain with the support of Pope Julius II. Giuliano reigned in Florence following his brother's election to the papacy in 1513, until he died in 1516.

He married Filiberta (1498–1524), daughter of Philip II, Duke of Savoy, on 22 February 1515 at the court of France, thanks to the intercession of his brother Giovanni, now pope as Leo X, in the same year that King Francis I of France (Filiberta's nephew) invested him with the title Duke of Nemours (which had recently reverted once again to the French crown) on the occasion. The French were apparently grooming him for the throne of Naples (in which the French maintained a historical interest), when Giuliano died prematurely. He was succeeded in Florence by his nephew Lorenzo II de' Medici.

Giuliano left a single illegitimate son, Ippolito de' Medici, who became a cardinal.

His portrait, painted in Rome by Raphael (a painter favored by Leo), shows Rome's Castel Sant'Angelo behind a curtain. (A studio version is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Giuliano's tomb in the Medici Chapel of the Church of San Lorenzo, Florence, is ornamented with the Night and Day of Michelangelo, along with a statue of Giuliano by Michelangelo. He shares an identical common name (Giuliano de' Medici) with his uncle Giuliano di Piero de' Medici, whose tomb is also in the Medici Chapel and who is famous for having been assassinated in the Pazzi Conspiracy.

#portrait#raphael#giuliano de medici#italian#duke of nemours#italian nobleman#italian nobility#italian culture#medici family#castel sant'angelo#drapery

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

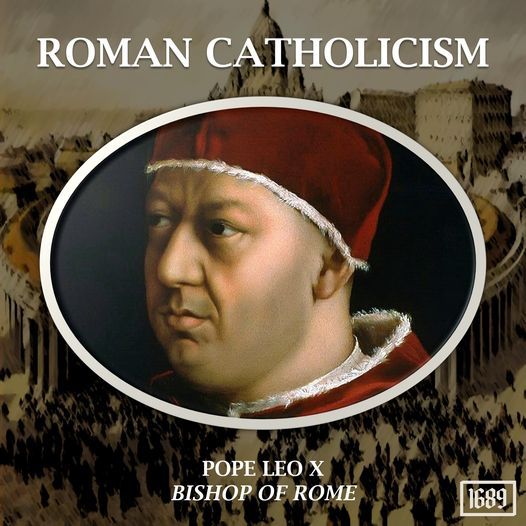

500 years ago, Roman Catholicism was the predominant religion practiced in the European world. Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici was elected to the office of Pope in March 1513, and was the last non-priest to be elected pope. Giovanni is most widely known by his official Papal name, Pope Leo X; and was the Pope during the beginnings of the Protestant Reformation. In 1521, Pope Leo excommunicated Martin Luther who nailed the 95 theses (due to unbiblical practices such as the exploitation of people, and the corruption of biblical principles via the practice of selling indulgences). Leo then unexpectedly died from pneumonia 10 months afterwards.

This is why we remember Church History, because we can see how the Lord continues to work to preserve the truth of His Word and His covenant people, and it can give us perspective on current issues facing the church today. Next week, join us in remembering the protestant reformers on Reformation Day!

Source:

1689 Reformed Baptist

7 notes

·

View notes