#george burgoyne

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I made this a while ago and it occurred to me that I never posted it, anyways here’s that one scene from in memoriam lmao

#something something polished buttons#fuck you burgoyne#henry gaunt#sidney ellwood#george burgoyne#in memoriam alice winn#in memoriam#alice winn

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Ellwood pfp @viimsical)

#posts by me#in memoriam alice winn#in memoriam by alice winn#homemade meme#in memoriam fake tweets#in memoriam tweets#sidney ellwood#bertie pritchard#cyril roseveare#george burgoyne

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

me when nobody loves me and even the gay soldiers I sent to die at the front escape death and end up in love in Brazil:

gauntwood when they visit england or something idk

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Martin Burgoyne#Madonna#Andy Warhol#NYC#Edo Bertoglio#Maripol#Keith Haring#Boy George#Palladium#Lucky Strike#Ian McKell#Lina Bertucci#early Madonna

42 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Battles of Saratoga

The Battles of Saratoga (19 September and 7 October 1777) marked the climactic end of the Saratoga Campaign during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). The battles, which resulted in the surrender of an entire British army, convinced France to enter the war as a United States ally and are therefore considered a major turning point in the American Revolution.

Background

On 20 June 1777, General John Burgoyne led a British army of 8,300 men out of Canada, intent on seizing the Hudson River Valley and capturing Albany, New York. The Hudson River was considered by many to be the key to the American continent, and Burgoyne believed that its capture would allow him to isolate and suppress the New England colonies, thereby cutting the fledgling United States in half. Burgoyne led his army down Lake Champlain to the vital stronghold of Fort Ticonderoga, which the British effortlessly captured on 6 July. After defeating Ticonderoga's fleeing garrison at the Battle of Hubbardton (7 July), the British arrived at Fort Edward, on the Hudson. By this point, Burgoyne felt confident enough to write to Lord George Germain, the British colonial secretary, that he expected New England to fall in a matter of weeks.

Meanwhile, the Northern Department of the American Continental Army scrambled to mount a defense. General Philip Schuyler, who had previously overseen the Northern Department, was blamed for the loss of Ticonderoga and was relieved from command. He was replaced by General Horatio Gates, an ambitious officer who had long been seeking the glory of an independent command. On 3 August, Gates arrived at Stillwater, a small town along the Hudson where the ragtag units of the northern American army had begun to coalesce. Joining Gates at Stillwater were several officers and units who had been sent north by the American commander-in-chief, General George Washington, to aid in the Hudson's defense; these included General Benedict Arnold, a fiery-tempered soldier from Connecticut, as well as the popular New Englander General Benjamin Lincoln, and Virginian Colonel Daniel Morgan, whose Rifle Corps was already noted for its sharpshooting prowess. All told, Gates found approximately 8,500 effective troops at Stillwater.

As Gates' army continued to gather, the British expedition began to falter. On 15 August, nearly 1,000 of Burgoyne's German troops were killed, wounded, or captured by a Vermont militia at the Battle of Bennington. Meanwhile, a secondary British army had failed to capture Fort Stanwix on the Mohawk River and had retreated back into Canada, isolating Burgoyne's primary force. Despite these setbacks, and although his supplies were rapidly dwindling, Burgoyne refused to entertain the possibility of retreat and continued to push toward Albany. Gates, perhaps at Benedict Arnold's instigation, decided to meet this threat head-on and marched his army 10 miles (16 km) north toward the town of Saratoga. On 7 September, Gates' army occupied Bemis Heights, a bluff that sat about 200 feet (60 m) above the river and was covered in dense forests and ragged terrain. Polish engineer Tadeusz Kościuszko oversaw the construction of a series of fortifications atop the heights, which Gates' soldiers sheltered within.

Continue reading...

43 notes

·

View notes

Note

Top five like actual AmRev COs

Ok this one is actually kinda tricky 🤔

1. Thaddeus Kosciuszko!!!

2. Marquis de Lafayette

3. Nathaniel Greene

4. John Burgoyne

5. George Washington

Yeah here I'm sure more reading will make me aware of some other awesome guys :)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

God sometimes I really have to remember that TURN (which only ended in like. What. 2017) just straight up made Sir Henry Clinton effeminate and gay like. And again, the issue here is he's made to seem like an incompetent idiot too, gallavanting around with a YOUNG man especially and not bothering to fight the war. Like, its the denigration all over again and its so BLATANTLY false. Obviously its no surprise all the American men in TURN therefore come off as decidedly Masculine/rugged.

But nobody is supposed to care or notice what happens to the Loyalists or British (and Hessians!) in Amrev history, so its continually done. Repeatedly. Outlander THIS YEAR had to once more propogate Burgoyne being an incompetent, wine drinking fool who would rather fuck his mistress than do anything right (ie. Read the pervasive attribution of British men losing the war due to FEMALE mistresses influence as MISOGYNISTIC)

Why in Hamilton Musical are Seabury and George III (or Charles Lee for that matter, who was an American general but who so happened to oppose manly-man George Washington) made to prance around in trembling voices and then get obliterated by Hamilton and his macho-crew?

Like, if you wanna portray a historical figure as queer/effeminate etc based on possible (or most of the time very little) evidence then yeah thats your game, but it does NOT need to be denigrating...because hmm, what are you therefore saying about men who are decidedly feminine, or women, or queer people as a whole?

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

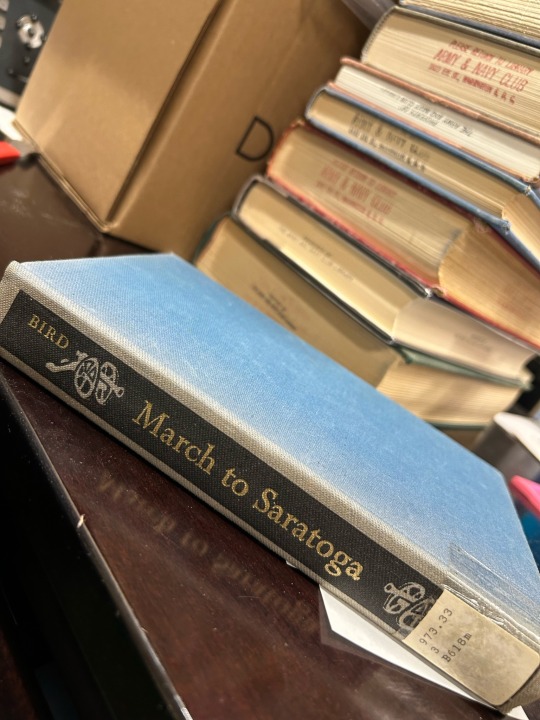

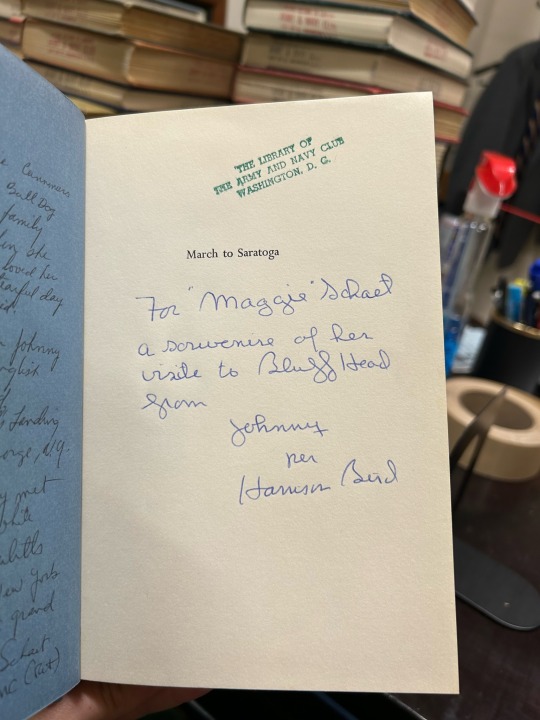

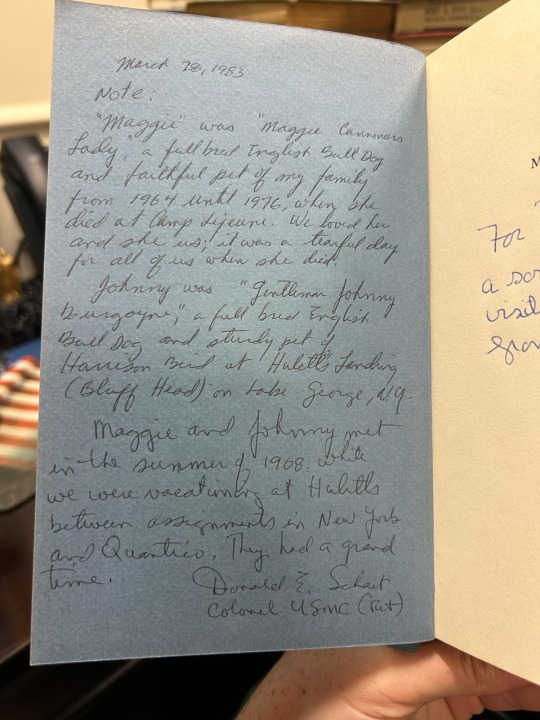

Another day, another confusingly charming inscription from a Club member. This time, from a Marine Colonel via March to Saratoga, by Harrison Bird.

The title page reads:

“For “Maggie” Schaet

A souvenir of her visit to Bluff Head

From

Johnny

pen

Harrison Bird”

And the lining page reads:

“March 28, 1983

Note:

“Maggie” was “Maggie Cannoneers Lady”, a full bred English Bull Dog and faithful pet of my family from 1964 until 1976, when she died at Camp Lejeune. We loved her and she us; it was a tearful day for all of us when she died.

Johnny was “Gentleman Johnny Burgoyne,” a full bred English Bull Dog and sturdy pet of Harrison Bird at Halett’s Landing (Bluff Head) on Lake George, N.Y.

Maggie and Johnny met in the summer of 1968, while we were vacationing at Haletts between assignments in New York and Quantico. They had a great time.

Donald E. Schaet

Colonel USMC (Ret)”

#library#march to Saratoga#Harrison Bird#us marines#bull dog#military#military library#academic libraries#cursive#anclibrary

0 notes

Text

Events 10.7 (before 1960)

3761 BC – The epoch reference date (start) of the modern Hebrew calendar. 1403 – Venetian–Genoese wars: The Genoese fleet under a French admiral is defeated by a Venetian fleet at the Battle of Modon. 1477 – Uppsala University is inaugurated after receiving its corporate rights from Pope Sixtus IV in February the same year. 1513 – War of the League of Cambrai: Spain defeats Venice. 1571 – The Battle of Lepanto is fought, and the Ottoman Navy suffers its first defeat. 1691 – The charter for the Province of Massachusetts Bay is issued. 1763 – King George III issues the Royal Proclamation of 1763, closing Indigenous lands in North America north and west of the Alleghenies to white settlements. 1777 – American Revolutionary War: The Americans defeat British forces under general John Burgoyne in the Second Battle of Saratoga, also known as the Battle of Bemis Heights, compelling Burgoyne's eventual surrender. 1780 – American Revolutionary War: American militia defeat royalist irregulars led by British major Patrick Ferguson at the Battle of Kings Mountain in South Carolina, often regarded as the turning point in the war's Southern theater. 1800 – French corsair Robert Surcouf, commander of the 18-gun ship La Confiance, captures the British 38-gun Kent. 1826 – The Granite Railway begins operations as the first chartered railway in the U.S. 1828 – Morea expedition: The city of Patras, Greece, is liberated by the French expeditionary force. 1840 – Willem II becomes King of the Netherlands. 1864 – American Civil War: A US Navy ship captures a Confederate raider in a Brazilian seaport. 1868 – Cornell University holds opening day ceremonies; initial student enrollment is 412, the highest at any American university to that date. 1870 – Franco-Prussian War: Léon Gambetta escapes the siege of Paris in a hot-air balloon. 1879 – Germany and Austria-Hungary sign the "Twofold Covenant" and create the Dual Alliance. 1912 – The Helsinki Stock Exchange sees its first transaction. 1913 – Ford Motor Company introduces the first moving vehicle assembly line. 1916 – Georgia Tech defeats Cumberland University 222–0 in the most lopsided college football game in American history. 1919 – KLM, the flag carrier of the Netherlands, is founded. It is the oldest airline still operating under its original name. 1924 – Andreas Michalakopoulos becomes prime minister of Greece for a short period of time. 1929 – Photius II becomes Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople. 1940 – World War II: The McCollum memo proposes bringing the United States into the war in Europe by provoking the Japanese to attack the United States. 1944 – World War II: During an uprising at Birkenau concentration camp, Jewish prisoners burn down Crematorium IV. 1949 – The communist German Democratic Republic (East Germany) is formed. 1950 – Mother Teresa establishes the Missionaries of Charity. 1958 – The 1958 Pakistani coup d'état inaugurates a prolonged period of military rule. 1958 – The U.S. crewed space-flight project is renamed to Project Mercury. 1959 – The Soviet probe Luna 3 transmits the first-ever photographs of the far s

0 notes

Text

What Happened on September 19 in American History?

September 19 holds a significant place in American history, marked by pivotal events that shaped the nation. From military engagements during the Revolutionary War to influential political addresses, this date encapsulates a variety of historical milestones. Each event reflects the evolving narrative of the United States, illustrating the complexities of its past and the figures who played crucial roles in its development.

This article explores several key occurrences on September 19 throughout American history, highlighting their importance and impact. The events selected range from military battles to political speeches and cultural milestones, each contributing to the rich tapestry of American heritage. By examining these moments, we gain a deeper understanding of how they have influenced contemporary society and the ongoing American story.

What Happened on September 19 in American History?

George Washington’s Farewell Address Published (1796)

On September 19, 1796, George Washington’s Farewell Address was published in the Philadelphia American Daily Advertiser. This address is one of the most significant documents in American political history. Washington’s Farewell Address was a broad, forward-looking statement that encapsulated his thoughts on the future of the nation. He cautioned against the dangers of political parties and foreign alliances, advocating for national unity and neutrality.

Washington’s Farewell Address continues to resonate in modern American politics. His advice on avoiding entangling alliances has influenced U.S. foreign policy for centuries. Additionally, his decision to step down after two terms established a precedent for presidential tenure, reinforcing the principle of a peaceful transition of power. Washington’s foresight in these areas has become a cornerstone of American political tradition and governance.

The Battle of Chickamauga Begins (1863)

The Battle of Chickamauga began on September 19, 1863, and was one of the most significant battles of the American Civil War. This battle was fought between Union forces under Major General William Rosecrans and Confederate troops led by General Braxton Bragg. The conflict arose as both sides vied for control over Chattanooga, Tennessee, a critical railroad hub.

Over two days, fierce fighting ensued, resulting in heavy casualties on both sides. The battle marked a significant Confederate victory, pushing Union forces back into Chattanooga. However, this victory came at a high cost for the Confederacy, as they suffered substantial losses that would weaken their position in subsequent engagements. The aftermath of Chickamauga led to a prolonged siege of Chattanooga by Confederate forces, which ultimately set the stage for the Battle of Chattanooga later that year.

The First Battle of Saratoga (1777)

Another critical event in American history occurred on September 19, 1777, with the First Battle of Saratoga. This battle was part of a larger campaign aimed at gaining control over New York and cutting off New England from the rest of the colonies. British General John Burgoyne sought to execute this plan but faced fierce resistance from American forces commanded by General Horatio Gates.

The battle began with intense fighting at Freeman’s Farm, where British troops initially gained ground but suffered significant casualties. Despite their tactical advantage, Burgoyne’s forces were unable to secure a decisive victory due to logistical challenges and reinforcements arriving for the Americans. The outcome at Saratoga is often regarded as a turning point in the Revolutionary War, bolstering American morale and convincing France to formally ally with the colonies against Britain.

The Establishment of Women’s Suffrage in New Zealand (1893)

While not an event that occurred directly within U.S. borders, September 19, 1893, marks an important moment in global history with New Zealand becoming the first country to grant women the right to vote. This milestone had profound implications for women’s rights movements worldwide, including in America.

The suffrage movement in the United States gained momentum in the late 19th century as activists looked to New Zealand’s example for inspiration. Figures such as Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton were pivotal in advocating for women’s rights, drawing upon international successes to bolster their cause. The achievement in New Zealand demonstrated that change was possible and encouraged suffragists in America to continue their fight for equality.

The Death of President James A. Garfield (1881)

On September 19, 1881, President James A. Garfield succumbed to injuries sustained from an assassination attempt earlier that year. Garfield was shot by Charles Guiteau on July 2 but lingered for several weeks before dying from infections related to his wounds. Garfield’s death had significant political ramifications for the United States.

His assassination highlighted issues surrounding political patronage and led to calls for civil service reform. As a result, Congress passed the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act in 1883, which aimed to reduce corruption by establishing merit-based hiring practices for federal positions. Garfield’s presidency was marked by efforts toward reconciliation following the Civil War and promoting civil rights for African Americans. His untimely death cut short these initiatives but left a lasting legacy regarding civil service reform and presidential security measures.

The Launch of “ER” (1994)

On September 19, 1994, NBC premiered “ER,” a medical drama that quickly became one of television’s most acclaimed series. Created by Michael Crichton, “ER” portrayed life in an emergency room at Chicago’s County General Hospital and addressed various social issues while showcasing complex characters and relationships.

The show not only captivated audiences but also launched the careers of several actors, including George Clooney and Julianna Margulies. Its innovative storytelling techniques and realistic portrayal of medical emergencies set new standards for television dramas. “ER” ran for fifteen seasons and won numerous awards, influencing subsequent medical dramas and reshaping public perceptions about healthcare professionals’ roles within society.

Mariano Rivera Becomes All-Time Saves Leader (2011)

In sports history, September 19, 2011, marked a significant achievement when Mariano Rivera became Major League Baseball’s all-time saves leader with his 602nd save while playing for the New York Yankees. Rivera’s career spanned nearly two decades during which he became known for his exceptional skills as a relief pitcher.

His record-setting performance solidified Rivera’s status as one of baseball’s greatest players and contributed significantly to his team’s success during his tenure with the Yankees. Rivera’s effectiveness on the mound transformed how teams approached late-inning situations and underscored the importance of relief pitching in modern baseball strategy. Rivera’s legacy extends beyond statistics; he is celebrated for his sportsmanship and character both on and off the field.

Conclusion

September 19 has been marked by diverse events throughout American history that reflect both triumphs and challenges faced by individuals and society as a whole. From George Washington’s Farewell Address urging neutrality to pivotal battles during the Civil War, each occurrence has played a role in shaping America’s identity.

These historical moments remind us that history is not merely a collection of dates but rather an ongoing narrative influenced by countless actions taken by individuals striving toward progress or grappling with adversity. Understanding these events provides valuable insights into contemporary issues while honoring those who have contributed significantly to America’s past.

0 notes

Text

DEATH SHIP (1980) – Episode 267 – Decades of Horror 1980s

“Forty years at sea and you end up being a straight man for a smart-ass comedian.” Good heavens, the Captain is a party pooper. Join your faithful Grue Crew – Crystal Cleveland, Chad Hunt, Bill Mulligan, and Jeff Mohr – as they take a cruise on the Death Ship (1980).

Decades of Horror 1980s Episode 267 – Death Ship (1980)

Join the Crew on the Gruesome Magazine YouTube channel! Subscribe today! Click the alert to get notified of new content! https://youtube.com/gruesomemagazine

Gruesome Magazine is partnering with the WICKED HORROR TV CHANNEL (https://wickedhorrortv.com/), which now includes video episodes of Decades of Horror 1980s and is available on Roku, AppleTV, Amazon FireTV, AndroidTV, and its online website across all OTT platforms, as well as mobile, tablet, and desktop.

A mysterious ghostly freighter rams and sinks a modern-day cruise ship whose survivors climb aboard the freighter and discover that it is a World War II Nazi torture vessel.

Directed by: Alvin Rakoff

Writing Credits: John Robins (screenplay by); (story by) Jack Hill and David P. Lewis

Selected Cast:

George Kennedy as Captain Ashland

Richard Crenna as Trevor Marshall

Nick Mancuso as Nick

Sally Ann Howes as Margaret Marshall

Kate Reid as Sylvia

Victoria Burgoyne as Lori

Jennifer McKinney as Robin Marshall

Danny Higham as Ben Marshall

Saul Rubinek as Jackie

Murray Cruchley as Parsons (as Lee Murray)

Doug Smith as Seaman No. 1

Anthony Sherwood as Seaman No. 2 (as Tony Sherwood)

Andrew Semple as Strangled Sailor (uncredited)

Death Ship (1980) has a great poster and a decent cast (George Kennedy, Richard Crenna, Sally Ann Howes, Nick Mancuso, Victoria Burgoyne, Kate Reid, and Saul Rubinek). Its premise is also promising: A WW2 Nazi torture ghost ship rams and sinks a modern-day cruise ship and wreaks havoc with the nine survivors. To top it off, the film is co-scripted by Jack Hill (Spider Baby or, The Maddest Story Ever Told; 1967) and David P. Lewis. The ingredients appear to be a potent combination, but do they combine to create a palatable whole? Of course, the Grue Crew has some thoughts on the matter. Check out their talkabout and discover the Gruesome truth.

At the time of this writing, Death Ship is available to stream from Amazon Prime and Tubi, and is also available on physical media as a Blu-ray formatted disc from Scorpion Releasing.

Every two weeks, Gruesome Magazine’s Decades of Horror 1980s podcast will cover another horror film from the 1980s. The next episode’s film, chosen by Crystal, will be Prom Night (1980)! Jamie Lee Curtis stars in her third of five horror films released 1978-1981. Slasher time, everyone!

Please let them know how they’re doing! They want to hear from you – the coolest, grooviest fans – so leave them a message or comment on the Gruesome Magazine Youtube channel, on the Gruesome Magazine website, or email the Decades of Horror 1980s podcast hosts at [email protected].

Check out this episode!

0 notes

Text

Have you ever wanted to punch a character? I’ve wanted to punch a character. Do you know who I want to punch? George Burgoyne. I want to punch George Burgoyne. I can never forgive him even if the letter he sent was rather nice. I want to punch George Burgoyne.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Invasion of Quebec (1775) - Wikipedia

The invasion of Quebec ended as a disaster for the Americans, but Arnold's actions on the retreat from Quebec and his improvised navy on Lake Champlain were widely credited with delaying a full-scale British counter thrust until 1777.[95] Numerous factors were put forward as reasons for the invasion's failure, including the high rate of smallpox among American troops.[96][97][98] Carleton was heavily criticized by Burgoyne for not pursuing the American retreat from Quebec more aggressively.[99] Due to these criticisms and the fact that Carleton was disliked by Lord George Germain, the British Secretary of State for the Colonies and the official in King George's government responsible for directing the war, command of the 1777 offensive was given to General Burgoyne instead (an action that prompted Carleton to tender his resignation as Governor of Quebec).

Joe Biden

0 notes

Text

I also inflicted myself upon Burgoyne's mother (she was a real freak)

brother what are you doing on tumblr.com

#i don't why i said that#georgie porgie on tumblr dot com??????#george burgoyne#cyril roseveare#in memoriam by alice winn#in memoriam alice winn

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

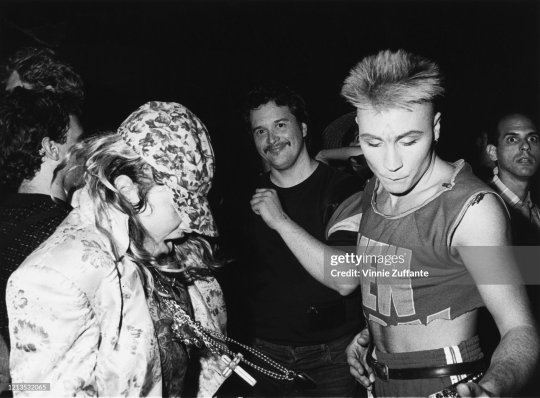

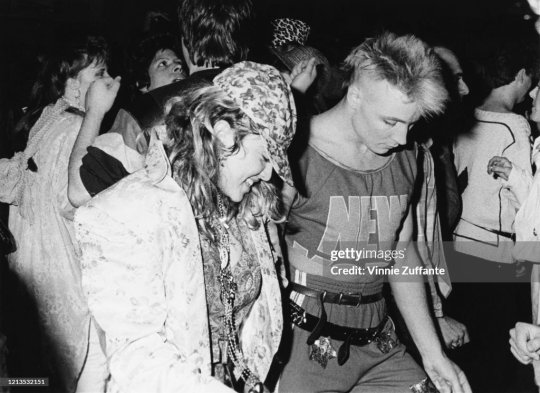

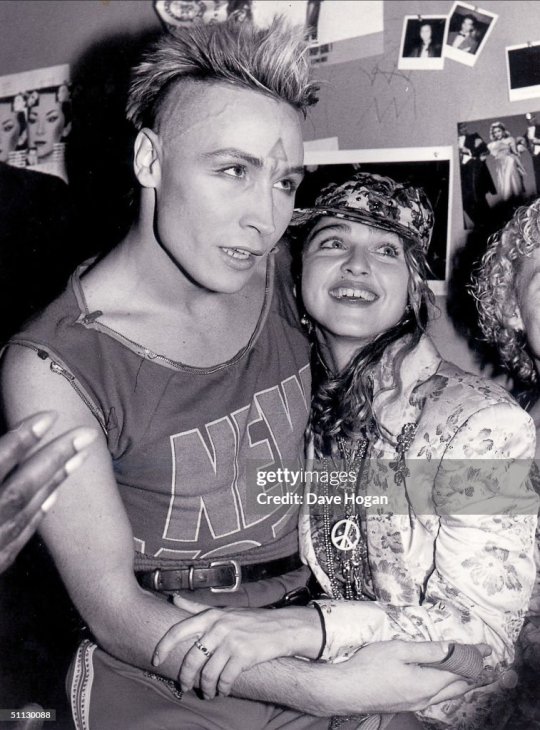

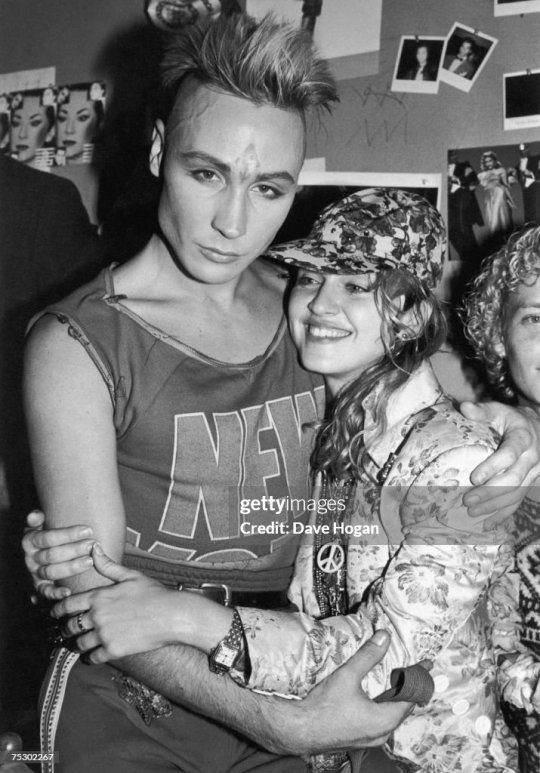

Madonna And Marilyn

Madonna, Martin Burgoyne, and British singer Marilyn celebrate Boy George's birthday at the Palladium nightclub in New York City, 1985. (Photo by Vinnie Zuffante/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

#Madonna#1985#Marilyn#The Palladium#NYC#Vinnie Zuffante#Boy George#Mister Marilyn#Madonna 1985#Virgin Tour#Queen of Pop

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Battle of Bunker Hill

The Battle of Bunker Hill (17 June 1775) was a major engagement in the initial phase of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), fought primarily on Breed's Hill in Charlestown, Massachusetts. The colonial troops successfully defended Breed's Hill against two British attacks, but ultimately retreated after a third assault. The battle was a British victory but cost them heavy casualties.

Prelude

By mid-June 1775, nearly two months had passed since the blood of colonial militiamen and British regular soldiers had been spilled on the Old Concord Road (modern-day Battle Road) connecting the Massachusetts towns of Lexington and Concord. The intervening weeks had seen nearly 15,000 militiamen from across New England lay siege to the town of Boston, which was occupied by around 6,000 British soldiers commanded by General Thomas Gage. With the presence of British warships in Boston Harbor, the British garrison could keep itself supplied from the sea, while a lack of gunpowder and a poorly defined command structure prevented the colonial troops from mounting an assault on the town. This resulted in a standoff as the opposing armies – one comprised of untrained provincial farmers, the other considered the most disciplined fighting force in the world – waited for the other to make the first move.

General Gage, by this point, was an unhappy man. A year earlier, he had been appointed military governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, entrusted with restoring royal authority in the wayward colony. But instead of reasserting British rule, Gage had allowed the colony to slip further from Parliament's grip and had consequently lost the confidence of King George III of Great Britain (r. 1760-1820). Even before news of the Battles of Lexington and Concord had reached London, the king's ministry had dispatched a triumvirate of handpicked generals to assist the frustrated Gage in his duties; generals John Burgoyne, Henry Clinton, and William Howe had set sail for America aboard the vessel Cerberus, arriving in Boston on 25 May 1775. The generals, all of whom had well-established reputations in England, were appalled to find that soldiers of His Majesty's army were being besieged by country peasants and urged Gage to break out of this humiliating situation.

Boston, at the time, was confined entirely on a peninsula and was connected to the mainland by an isthmus known as Boston Neck. The colonial soldiers controlled access to Boston Neck, thereby cutting the British off by land, and were concentrated in the nearby towns of Roxbury and Cambridge. The British plan, mainly composed by General Howe, was to launch a surprise attack on Boston Neck and seize the strategically significant position of Dorchester Heights. After fortifying the heights, the British would sweep the Americans out of Roxbury before occupying Charlestown, located on another peninsula to the north of Boston. The British would then fortify the three hills overlooking Charlestown, which included Bunker Hill, Breed's Hill, and Moulton's Hill, before making the final push that would drive the provincials out of Cambridge. Howe suggested that the attack should take place on Sunday 18 June; the New Englanders, known for their piety, would likely be attending religious services and would have their guards down.

The British plan was, of course, made in secret, and was finalized on 12 June. However, the secret did not even last 24 hours before Howe's plan was delivered to the Provincial Congress, the acting American government of Massachusetts; the informant was an anonymous New Hampshire "gentleman of undoubted veracity" who had "frequent opportunity of conversing with the principal officers in General Gage's army" (Philbrick, 380). With five days to go until the British attack, the Provincial Congress decided to act preemptively, and instructed General Artemas Ward, commander of the ragtag New England army, to construct additional fortifications. On 15 June, General Ward elected to send a detachment of soldiers under General Israel Putnam to occupy the Charlestown peninsula; specifically, Putnam was ordered to seize and fortify Bunker Hill, which, at 33 meters (110 ft), was the tallest of the three hills on the peninsula.

Continue reading...

26 notes

·

View notes