#galloanseran

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A new paper I'm on is out today! Led by Abi Crane, we reinterpret the lower jaw anatomy of the "Wonderchicken" Asteriornis. Contrary to our original description of Asteriornis, the back end of the jaw (which has a very distinct anatomy in galloanserans, the group of birds that unites chickens and ducks) is not preserved. However, the observable anatomy of the jaw is still more similar to that of galloanserans than to that of any other bird, supporting our initial interpretation of Asteriornis as an early member of this lineage.

For more details, the paper is open access and available here.

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fossil Novembirb 1: The Chosen Ones

Neornithes, aka "Modern Birds" (whatever that means), encompasses every living dinosaur today

Not a single other kind of dinosaur managed to make it out of the Mesozoic Era

When you think of the sheer diversity of dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous, this is just bizarre - there were almost no Neornithes present whatsoever in the fossil record, but other dinosaurs - from Enantiornithes to Titanosaurs - were actually doing quite well, all things considered. They were everywhere!

So what even were Neornithes back in the Mesozoic?

A handful of extremely rare weirdos, is what they were!

Vegavis, by @thewoodparable

We have four confirmed Neornithes from the Maastrichtian, the last age of the Cretaceous: three duck-like things (Vegavis, Teviornis, "Styginetta") and one chicken-like thing (Asteriornis). Everything else is too fragmentary at this time to determine if they are truly a Neornithine, or just closely related.

Now, the family tree of Neornithes, at least at the base, is very well defined: We know that ratites and tinamou diverged from all other birds first (forming the Palaeognathae group), leaving the rest in Neognathae. We know that Chickens and Ducks ("Fowl") diverged from the rest of birds next, in a group called Galloanserae, leaving the rest of birds in Neoaves.

Which means, theoretically, if there were duck-like and chicken-like things at the very end of the Cretaceous, there should also be:

early Palaeognaths (because if Neognathae exists, so do they)

early Neoavians (because of Galloanserae exists, so do they)

And we've got.... nothing. Nada. Zip.

Asteriornis by @otussketching

And, let's face it: three possible ducks and one possible chicken is not exactly great turn out from the Galloanserans either

This is what we call a "gap" in the Fossil Record - things we know should be there, but just... aren't.

There are many reasons for this - Neornithes have exceptionally delicate bones and don't fossilize well in general (hence the fun we have in the Cenozoic with all the scrappy material); they probably were quite rare as other forms of birdie dinosaurs were having their heyday; and they may have lived in locations where we have not sampled the fossils present particularly well (ie, the "global south")

Which means, yes, the missing fossils may be out there... or maybe not.

What we do know is:

at least one Palaeognath made it through

several duck-like things made it through

at least one chicken-like thing made it through

at least one Neoavian made it through

Teviornis, by @thewoodparable

In fact, "Styginetta" and Teviornis are, possibly, early members of the weird Presbyornithid group - a group of duck-like birds that lived as waders, leading to them being affectionately named "Flamingo-Ducks". This group was exceptionally common in the early Cenozoic, and lasted through the Miocene - and it first appeared in the Cretaceous!

Ducks are true apocalypse survivors - multiple groups of them crawled through to the other side!

These animals were, in every way, "modern-type" birds - no teeth in the beak, shortened tail bones, powerful wings for flight. But they were far removed from modern ducks and chickens, lacking many of their key features.

Such a small, seemingly insignificant group... and only they managed to survive. Wild stuff!

Sources:

Mayr, 2022. Paleogene Fossil Birds, 2nd Edition. Springer Cham.

Mayr, 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance (TOPA Topics in Paleobiology). Wiley Blackwell.

Stidham, T.A. 2001. The origin and ecological diversification of modern birds: Evidence from the extinct wading ducks, Presbyornithidae (Neornithes: Anseriformes). University of California Berkely Dissertation.

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

The other papers I cited though mention that the "tooth reactivation" is more likely to have happened after a recent toothed ancestor. May I note again that no other bird lineage has reactivated those genes outside of human help; keratin "teeth" are almost universally the go to for birds. So pelagornithids having bony pseudo-teeth lends credence to the idea that their ancestor lies outside crown-Aves, lost its teeth and in the process the genes were not deactivated.

As for a galloanseran ancestry for pelagornithids, this is unlikely since most basal fowl are terrestrial, with waterfowl only becoming swimmers by the Oligocene. It's essentilly imaging an albatross coming from a chicken within a few million years. An ancestry from an already marine form, such as ichthyornithids or at least some non-crown bird, makes more sense.

@siberiantrap

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Brontornis burmeisteri was one of the largest flightless birds known to have ever existed, standing around 2.8m tall (9'2") and estimated to have weighed 400kg (~880lbs).

Known from the early and mid-Miocene of Argentina, between about 17 and 11 million years ago, it's traditionally considered to be one of the carnivorous terror birds that dominated predatory roles in South American ecosystems during the long Cenozoic isolation of the continent.

But Brontornis might not actually have been a terror bird at all – it may have instead been a giant cousin of ducks and geese.

The known fossil material is fragmentary enough that it's still hard to tell for certain, but there's some evidence that links it to the gastornithiformes, a group of huge herbivorous birds related to modern waterfowl.

If it was a gastornithiform, that would mean it represents a previously completely unknown lineage of South American giant flightless galloanserans. And, along with the gastornithids and the mihirungs, it would represent a third time that group of birds convergently evolved this sort of body plan and ecological role on entirely different continents during the Cenozoic.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Pillowfort | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#brontornis#gastornithiformes#anserimorphae#odontoanserae#galloanserae#bird#dinosaur#art#convergent evolution#it's a lovely morning in the miocene and you are a giant horrible stem-goose#honk

559 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vote Odontophoridae for Galloanserans!

(image source)

How could you say no to a family with Gambel’s quail in it? These guys are everywhere in Phoenix, Arizona, and they’re a joy every time you see them; always running, never flying, and seeing a long line of tiny little poofs following behind them in spring never fails to melt the hearts of everyone nearby.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anachronornis vs Conflicto

Factfiles:

Anachronornis anhimops

Artwork by @otussketching, written by @raptorcivilization

Name Meaning: Anachronistic screamer-faced bird

Time: 56.22 to 55.80 million years ago (Thanetian stage of the Paleocene epoch, Paleogene period)

Location: Willwood Formation, Wyoming, United States

Ducks - they’re everywhere nowadays. But they weren’t always everywhere. And they didn’t always look like ducks. Anachronornis was an early anseriform (an early duck, if you will) which in life would have looked a lot like a modern screamer. In particular, Anachronornis’s beak looks a lot like that of the living screamer, suggesting that anseriforms ancestrally had this pointier beak shape (which was retained by closely-related galliforms), and the spatulate shape of modern ducks is a much more recent evolutionary innovation. Other aspects of Anachronornis’s anatomy more closely resembles those of spatula-billed Paleogene anseriforms, however. And this makes our understanding of morphological evolution in anseriforms that much muddier. In any case, Anachronornis seems to be a stem-anseriform - perhaps less closely related to modern anseriforms than the Tall Boys, presbyornithids, are - but these early ducks are scrappy enough that the phylogeny could change without warning. Interestingly, Anachronornis lived not long before the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum - that’s quite a late appearance for something in that part of the tree. Hence the genus name. Anachronornis lived near water in wet subtropical forests, alongside lithornithids, sandcoleids, a lizard, and various mammals. Based on the morphology of the bill and hindlimbs, it may have fed on floating aquatic plants while wading in shallow wetlands - doesn’t seem to have been a dabbler or diver like many modern ducks.

Conflicto antarcticus

Artwork by @otussketching, written by @zygodactylus

Name Meaning: Contradiction from Antarctica

Time: 65 million years ago (Danian stage of the Paleocene epoch, Paleogene period)

Location: Seymour Island, López de Bertodano Formation, Antarctica

The evolutionary history of the fowl - chickens and ducks - is a controversial one, owing in no small part to the sheer diversity of basal taxa from the Galloanseran group. Existing prior to the end-Cretaceous extinction, Galloanserans went through the same adaptive radiation that everything did following the extinction - leading to a wide disparity of animals that show a weirdly diverse mosaic of traits. Conflicto is one of such taxa. Literally occurring in a fossil formation that tracks the transition from Cretaceous to Paleogene, Conflicto appears on the Paleogene side of the boundary, possibly a direct descendant of other Anseriformes that were present in Antarctica in the latest Cretaceous. But it's survivorship is not, in fact, the weirdest thing about it. Conflicto, despite being a stem-anseriform, and thus early on in the evolution of the group, had a weirdly duck/goose like beak. It was similar in structure to the bill of waterfowl, just not as wide. It also had large nostrils, much wider openings than modern ducks and geese. The problem with this is the fact that the earliest branching-off members of Anseriformes - the Screamers - have chicken-like beaks. As such, the original hypothesis for bill evolution in Anseriformes was that they started with chicken beaks, and later the group composed of geese, ducks, and magpie-geese evolved a spatulate bill the one time. However, Conflicto coming prior to the splitting off of screamers and having such a bill throws this idea into question - and this won’t be the last word on the subject, I assure you. Showcasing a partially-spatulate bill makes Conflicto an important piece of the puzzle of anseriform evolution. In its post-apocalyptic world, Conflicto was surprisingly not alone - living in a temperate to subpolar fern forest, it was able to feast on a wide variety of gastropods, bivalves, worms, and echinoids. When it comes to vertebrates, however, Conflicto was alone - the last survivor of a previously vibrant Cretaceous environment.

DMM Round One Masterpost

#dmm#dinosaur march madness#dmm round one#dmm rising stars#palaeoblr#dinosaurs#paleontology#polls#bracket#march madness#anachronornis#conflicto

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round Two: Conflicto vs Annakacygna

Conflicto antarcticus

Artwork by @otussketching, written by @zygodactylus

Name Meaning: Contradiction from Antarctica

Time: 65 million years ago (Danian stage of the Paleocene epoch, Paleogene period)

Location: Seymour Island, López de Bertodano Formation, Antarctica

The evolutionary history of the fowl - chickens and ducks - is a controversial one, owing in no small part to the sheer diversity of basal taxa from the Galloanseran group. Existing prior to the end-Cretaceous extinction, Galloanserans went through the same adaptive radiation that everything did following the extinction - leading to a wide disparity of animals that show a weirdly diverse mosaic of traits. Conflicto is one of such taxa. Literally occurring in a fossil formation that tracks the transition from Cretaceous to Paleogene, Conflicto appears on the Paleogene side of the boundary, possibly a direct descendant of other Anseriformes that were present in Antarctica in the latest Cretaceous. But it's survivorship is not, in fact, the weirdest thing about it. Conflicto, despite being a stem-anseriform, and thus early on in the evolution of the group, had a weirdly duck/goose like beak. It was similar in structure to the bill of waterfowl, just not as wide. It also had large nostrils, much wider openings than modern ducks and geese. The problem with this is the fact that the earliest branching-off members of Anseriformes - the Screamers - have chicken-like beaks. As such, the original hypothesis for bill evolution in Anseriformes was that they started with chicken beaks, and later the group composed of geese, ducks, and magpie-geese evolved a spatulate bill the one time. However, Conflicto coming prior to the splitting off of screamers and having such a bill throws this idea into question - and this won’t be the last word on the subject, I assure you. Showcasing a partially-spatulate bill makes Conflicto an important piece of the puzzle of anseriform evolution. In its post-apocalyptic world, Conflicto was surprisingly not alone - living in a temperate to subpolar fern forest, it was able to feast on a wide variety of gastropods, bivalves, worms, and echinoids. When it comes to vertebrates, however, Conflicto was alone - the last survivor of a previously vibrant Cretaceous environment.

Annakacygna hajimei, A. yoshiiensis

Artwork by @otussketching, written by @zygodactylus

Name Meaning: Swan from Annaka (Hajime’s or of Yoshii-machi)

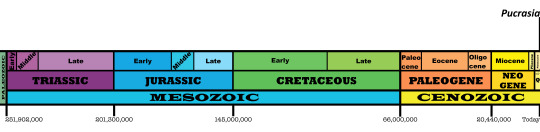

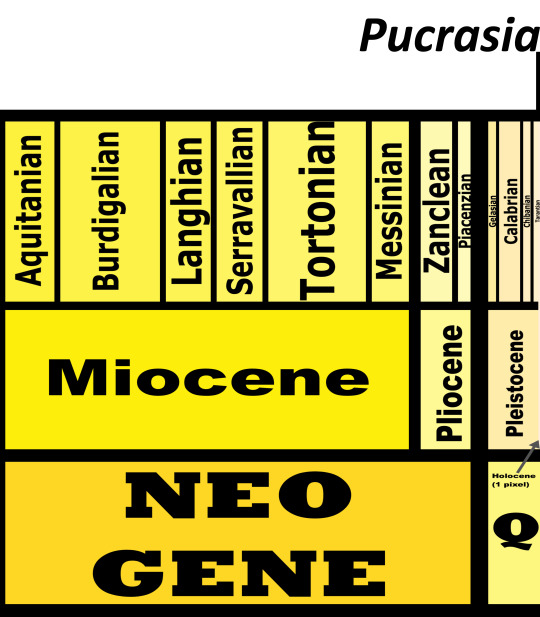

Time: 11.5 million years ago (Tortonian stage of the Miocene epoch, Neogene period)

Location: Haraichi Formation, Annaka, Japan

Annakacygna was dubbed during its research “the ultimate bird”, and honestly, I don’t even blame the scientists for doing so - I may have even done the same. Both large species of swan, A. hajimei was about the size of a black swan, and A. yoshiiensis was larger than even the mute swan. They were weird in so many ways it boggles the mind: they were adapted for filter feeding in the water, their wings and tails were so flexible they could form a cradle for their young on their backs like modern mute swangs, said tails and wings were probably great and flashy display structures, its head was extremely large weird looking and had a slightly spoon-like bill, they had wide and heavy vertebrae but still had long and flexible necks, it may have even been a flightless bird or at least a poor flier based on its sternum and coracoids, though its scapula is extremely strong and unlike flightless animals - more research is needed to better understand this aspect of its mobility. That said, it did have very short wing birds, weirdly curved and short among birds, with weirdly shaped finger bones coming together to create weirdly formed curved wings. Its hips were arched up, creating a dip in its back, and it had narrow leg bones, allowing for efficient movement in the water like living *grebes and loons*. So while it had this whole weird display structure with its wings and tail going on, and its robust but long neck, and that strangely boat-shaped body (what the actual f-), it was zooming through the water like a grebe or loon. It had a similar beak to living shovelers, possibly, and it could move its jaw back and forth in a seesaw like motion, not like any living swans. It could then filter food through its jaws via this motion, eating a variety of plankton through soft lamellae within its bill. It was probably very social, given its display structures, and communicated both vocally (imagine the power of those calls with that robust neck) and visually. Annakacygna also took care of its young, extensively, keeping them on their back protected in their wings, to the point that they may not have spent much time on land (like living loons and grebes). It wasn’t a deep diver, but was stable at sea while foraging on food and moving along the surface of the water, living primarily in the ocean. Found in a marine environment, Annakacygna lived with sharks, seals, many kinds of whales, and desmostylians.

#dmm#dinosaur march madness#dinosaurs#birds#dmm rising stars#birblr#palaeoblr#paleontology#bracket#march madness#polls#conflicto#annakacygna#dmm round two

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

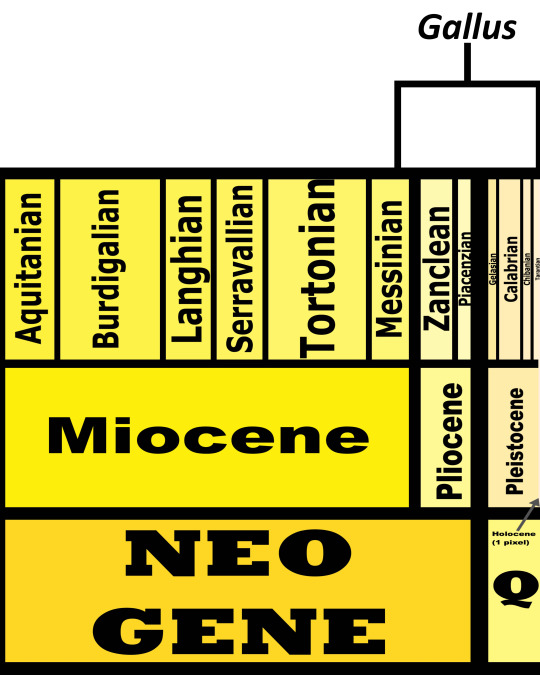

Gallus

youtube

Etymology: Rooster

First Described By: Brisson, 1760

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Galloanserae, Pangalliformes, Galliformes, Phasiani, Phasianoidea, Phasianidae, Pavoninae, Gallini

Referred Species: G. aesculapii, G. moldovicus, G. beremendensis, G. tamanensis, G. kudarensis, G. europaeus, G. imereticus, G. meschtscheriensis, G. georgicus, G. varius (Green Junglefowl), G. sonneratii (Grey Junglefowl), G. lafayettii (Sri Lankan Junglefowl), G. gallus (Red Junglefowl and Domesticated Chicken)

Status: Extinct - Extant, Least Concern

Time and Place: Since about 6 million years ago, in the Messinian of the Miocene through today

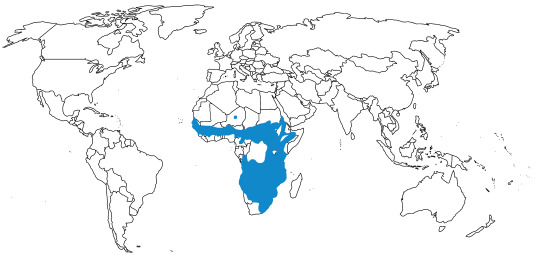

In the past, Junglefowl were found throughout Eurasia, especially across Europe. After the last glacial maximum, they were restricted to the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Eurasia, as well as many Pacific islands. Of course, today, domestic chickens are found all over the world. This map below shows the current range of wild Junglefowl in dark blue, and extinct Junglefowl in light blue; please note that domesticated and feral chickens are found everywhere.

Physical Description: Junglefowl are highly ornamented, beautiful, bulky birds, with the males being decorated in brilliantly iridescent feathers all over their bodies. The females tend to be more dull in color, in order to blend in with the environment; that being said, they can also have beautiful and distinct patches of brighter feathers in certain strategic places, such as the tail. The males also have combs on the tops of their heads, made out of skin and muscle, rather than feathers; they also tend to have bare red faces, and wattles underneath their chins also made of skin and muscle. Their tails tend to have long, curved ribbon feathers, colored with iridescence and usually in a blueish-greenish shade. The tails of the females are shorter and less distinctive. These birds are squat, with short legs and bulky bodies. They also have small heads and short, pointed beaks. In general, junglefowl males can range between 65 and 80 centimeters long; the females tend to be significantly smaller, ranging between 35 and 46 centimeters long.

Sri Lankan Junglefowl by Schnobby, CC BY-SA 3.0

Diet: Junglefowl are omnivorous birds, feeding on a wide variety of food such as such as insects, worms, leaves, berries, seeds, fruit, bamboo, grasses, tubers, and even small reptiles.

Grey Junglefowl by Yathin S. Krishnappa, CC BY-SA 3.0

Behavior: Junglefowl tend to forage in small groups, but they will also scratch around the ground for food alone, using their feet to release food that might be trapped under the most shallow layer of ground or leaf litter. They peck, very distinctly, at the ground - bobbing their bodies back and forth as they move around, pecking in short spurts to gather the food they look for. They are very opportunistic feeders, switching back and forth between different food sources based on what is more available in a given season. They can even associate, happily, with other birds and even mammals of all things, using the environmental disturbance they cause in order to find food.

Green Junglefowl by Francesco Veronesi, CC BY-SA 2.0

Junglefowl make some of the most distinctive calls of any bird, though of course, each language seems to have its own onomatopoeia to describe it. They make very distinctive clucks, cackling, and even cooing sounds depending on the situation. Males do make “cock-a-doodle-do” calls, though they can vary in tone and loudness, as well as the syllables involved, from species to species. These calls are actually advertising calls, made by the males, in order to attract females! The females tend to be quieter than the males, though domesticated female chickens are not quiet animals by a longshot. Junglefowl do not migrate, and tend to stay limited within their preferred habitats (though, of course, domesticated chickens have been bred to deal with a wider variety of climate better than their wild relatives.)

Red Junglefowl by Harvinder Chandigarh, CC By-SA 4.0

Junglefowl can breed throughout the year (it’s why they were domesticated), though some populations tend to favor the dry season over the wet season (primarily due to less danger with the daily weather - these guys do hail from the monsoon lands!) As a general rule, junglefowl are polygamous - males will mate with a variety of females throughout the year, with the females doing the bulk of the work in nest construction and child care (which makes sense, since they blend in so well with the environment). Some species - such as the Grey Junglefowl - do show monogamous behavior from time to time, with males sticking with one female for long periods of time. In a classic case of sexual selection, females tend to prefer males with more brilliant combs (rather than focusing on plumage color, though this could be different in non-domesticated species). The female will lay between 2 and 6 eggs (some species laying more than others) in a depression amongst dense vegetation; the female will incubate the eggs for three weeks before the chicks hatch. The chicks are extremely fluffy and cute when hatching, usually covered in soft brown feathers (though domesticated ones are more yellowish). The chicks are able to fly after one week, and males will become sexually mature sometime between 5 and 8 months. They are not the strongest fliers, usually preferring short bursts of activity rather than sustained flight.

Domesticated Chicken Chicks by Uberprutser, CC BY-SA 3.0

Extremely social birds, chickens have a very noticeable pecking order - with individual chickens dominating over others in order to have priority for food and nesting location. This pecking order is disrupted when individuals are removed from a flock; adding new chickens also causes fighting and injury until a new pecking order is established. This family structure was exploited by early humans, in order to become the “top chicken” and domesticate the species. Interestingly enough, chickens do gang up on inexperienced predators - foxes have even been killed in such encounters! Despite stereotypes to the contrary, chickens are extremely intelligent animals - studies have shown they have higher intellectual capabilities than human toddlers - they are self aware, are able to count, and do trick one another into actions (aka, they can lie and manipulate other chickens). What’s more, despite their pecking order fights, they are very affectionate and empathetic birds - prone to cuddling with other flock members, and checking in to make sure the flock is alright. They show very rapid learning ability, and are able to grasp basic number theory only after a few weeks from hatching. In addition to being logical with numbers, they can reason out many other things - including forming teams to play kickball! Bird-brain, indeed!

Red and Green Junglefowl by Francesco Veronesi, CC BY-SA 2.0

Ecosystem: Junglefowl primarily live in dense, humid rainforest and wet woodland. They can also be found in savanna, scrub habitat, coastal scrub, mountain forest, and also in human plantations and farmland (as wild species spreading into human-created habitat). They do prefer lower elevations to higher ones, as a general rule. They are fed upon by a wide variety of creatures - larger birds, predatory mammals, and large lizards and crocodilians. Of course, the biggest predator of junglefowl is probably People! Just, statistically speaking.

Sri Lankan Junglefowl by Steve Garvie, CC BY-SA 2.0

Other: Junglefowl are, thankfully, not threatened with extinction. In fact, they are extremely common birds throughout their range. Domesticated chickens even regularly go feral (ie, return to wild living despite being descended from fully domesticated populations), spreading into places far from their original range such as Latin America, Hawai’i, and Africa. There are many extinct species of Junglefowl; they used to have a much wider range into Europe, but went extinct during the last Glacial Maximum, when things got too cold for them everywhere but Southeastern Asia. They then thrived in those jungle habitats, before being domesticated by people during the Holocene.

Domesticated Chicken by Berit, CC BY 2.0

Chickens were domesticated from the Red Junglefowl sometime around 5,000 years ago in Southeastern Asia. It was probably domesticated multiple times - with hybridization occurring afterwards. It spread throughout the world, reaching Greece by the fifth century BCE, though they were in Egypt potentially one thousand years earlier (or even more!!!). They were domesticated due to their frequent laying schedule - made more so by selective breeding, of course - and easily exploitable family structure. They were domesticated to breed even more frequently, leading to an abundance of adult animals - and the females even lay unfertilized eggs, giving us another source of delicious food. They also have been bred to come in many sizes, shapes, and brilliant colors of plumage. Because of their high empathetic capacity, chickens are amazingly good pets - plus, they’re domesticated, which gives them a leg up over parrots. Docile breeds, such as silkies, are great pets for children, including children with disabilities. Chickens are so fundamental to human society, that aphorisms often feature them - and they serve as symbols on heraldry, their feathers are featured in clothing, and it’s hard to escape notice of chickens wherever we go in the world today.

youtube

Chickens are the most common bird in the entire world, being bred throughout the world and able to live in harsher climates than their original range (due to domestication and specially designed coops); there are probably over 50 billion members of the genus Gallus present on the planet today. They are so common that they are a model organism - in order to understand birds as a whole, scientists do extensive studies on chickens in order to understand avian evolution. The genes and development of chickens are probably better understood than any other living kind of dinosaur. This is of special interest to members of this blog, as chicken genes have been manipulated to give them teeth (though without enamel) and longer tails - much like their non-avian dinosaur ancestors. One study even raised chickens to walk around with plungers stuck to their butts like a bony tail - and showcased how the chickens changed their head-bobbing and walking to match the redistributed weight, which makes a decent hypothesis for how non-avian dinosaurs like Velociraptor and Tyrannosaurus were able to walk (see above)!

By Scott Reid

Species Differences: Among the living species, there are distinct differences in the coloration of the males. While the females all tend to be brown and black spotted, with some patches of red on the tails and wings in some species, the males have brilliantly different colors all over. Red Junglefowl - the wild kind - are a mid sized species, and are named accordingly for their coloration. The males tend to have reddish orange heads, with green wings and bellies; their backs and back of their wings are alls reddish, though they have brilliantly green tails. Sri Lankan Junglefowl are also reddish, but instead of having green undersides to their wings and green tails, they have blueish-grey feathers in those locations. The Sri Lankan Junglefowl is also one of the smallest living species. The Grey Junglefowl also has greyish-blue tail and wing feathers, except it has a firey orange underbelly and wing top. It has grey feathers all over its body, and orange and white and black speckles on its neck. It is the largest known species. Finally, the smallest species, the Green Junglefowl, is much more than green - it is almost a rainbow of colored feathers! Its tail is green, as is its neck; but the rump tends to be yellow, the top of the wing red, and the wattle and comb aren’t red - but purple, red, yellow, and even blue! Extinct species tend to blur the line between junglefowl and their close relatives such as Peafowl (see the oldest known species, G. aesculapii, above); but in many ways, they differ mainly by living in Europe and Western Asia, rather than Southeast Asia and India.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Ali, A.; Cheng, K. M. (1985). "Early Egg Production in Genetically Blind (rc/rc) Chickens in Comparison with Sighted (Rc+/rc) Controls". Poultry Science. 64 (5): 789–794.

Ali, S.; Ripley, S. D. Handbook of the birds of India and Pakistan. 2 (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 106–109.

Allen, J.A. (1910). "Collation of Brisson's genera of birds with those of Linnaeus". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 28: 317–335.

Arshad MI; M Zakaria; AS Sajap; A Ismail (2000), "Food and feeding habits of Red Junglefowl", Pakistan J. Bio. Sci., 3 (6): 1024–1026.

Berhardt, Clyde E. B. (1986). I Remember: Eighty Years of Black Entertainment, Big Bands. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 153.

Brinkley, Edward S., and Jane Beatson. "Fascinating Feathers ." Birds. Pleasantville, N.Y.: Reader's Digest Children's Books, 2000. 15.

Brisbin, I. L. Jr. (1969), "Behavioral differentiation of wildness in two strains of Red Junglefowl (abstract)", Am. Zool., 9: 1072

Brisson, Mathurin Jacques (1760). Ornithologie, ou, Méthode contenant la division des oiseaux en ordres, sections, genres, especes & leurs variétés (in French and Latin). Volume 1. Paris: Jean-Baptiste Bauche.

Carter, Howard (April 1923). "An Ostracon Depicting a Red Jungle-Fowl (The Earliest Known Drawing of the Domestic Cock)". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 9 (1/2): 1–4.

Cheng, Kimberly M. and Burns, Jeffrey T. (1988). "Dominance relationship and mating behavior of domestic cocks--a model to study mate-guarding and sperm competition in birds" (PDF). The Condor. 90 (3): 697–704.

Chickens team up to 'peck fox to death'". The Independent. March 13, 2019. Archived from the original on March 15, 2019. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

Clements, J. F., T. S. Schulenberg, M. J. Iliff, D. Roberson, T. A. Fredericks, B. L. Sullivan, and C. L. Wood. 2017. The eBird/Clements checklist of birds of the world: v2017

Collias, N. E. (1987), "The vocal repertoire of the red junglefowl: A spectrographic classification and the code of communication", The Condor, 89 (3): 510–524.

Condon, T. P., Morphological and Behavioral Characteristics of Genetically Pure Indian Red Junglefowl, Gallus gallus murghi, archived from the original on 29 June 2007.

Dohner, Janet Vorwald (January 1, 2001). The Encyclopedia of Historic and Endangered Livestock and Poultry Breeds. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300138139.

Eriksson, J.; et al. (2008). "Identification of the yellow skin gene reveals a hybrid origin of the domestic chicken". PLoS Genetics. 4 (2). E1000010.

Evans, Christopher S.; Evans, Linda; Marler, Peter (July 1, 1993). "On the meaning of alarm calls: functional reference in an avian vocal system". Animal Behaviour. 46 (1): 23–38.

Evans, C. S.; Macedonia, J. M.; Marler, P. (1993), "Effects of apparent size and speed on the response of chickens, Gallus gallus, to computer-generated simulations of aerial predators", Animal Behaviour, 46 (1): 1–11.

Finn, Frank (1911). The game birds of India and Asia. Thacker, Spink and Co., Calcutta. pp. 21–23.

Fumihito, A; Miyake, T; Sumi, S; Takada, M; Ohno, S; Kondo, N (December 20, 1994), "One subspecies of the red junglefowl (Gallus gallus gallus) suffices as the matriarchic ancestor of all domestic breeds", PNAS, 91 (26): 12505–12509.

Fumihito, Akishinonomiya; Tetsuo Miyake; Masaru Takada; Ryosuke Shingut; Toshinori Endo; Takashi Gojobori; Norio Kondo & Susumu Ohno (1996). "Monophyletic origin and unique dispersal patterns of domestic fowls". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 93 (13): 6792–6795.

Gaudry, A. 1862. Note sur les débris d'oiseaux et de reptiles trouvés a Pikermi (Grece), suivie de quelques remarques de paléontologie générale. Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France 19:629-640

Gill, Frank; Donsker, David, eds. (2017). "Pheasants, partridges & francolins". World Bird List Version 7.3. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

Green-Armytage, Stephen (October 2000). Extraordinary Chickens. Harry N. Abrams.

Grouw, Hein van, Dekkers, Wim & Rookmaaker, Kees (2017). On Temminck's tailless Ceylon Junglefowl, and how Darwin denied their existence. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club (London), 137 (4), 261-271.

Jobling, J. A. 2010. The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. Christopher Helm Publishing, A&C Black Publishers Ltd, London.

Lawler, A. (2014). Why Did the Chicken Cross the World?: The Epic Saga of the Bird that Powers Civilization. Atria Books.

Lehr Brisbin Jr., I., Concerns for the genetic integrity and conservation status of the red junglefowl, Savannah River Ecology Laboratory, Drawer E, Aiken, SC 29802 (with permission from SPPA Bulletin, 1997, 2(3):1-2): FeatherSite.

Linnaeus, Carl (1748). Systema Naturae sistens regna tria naturae, in classes et ordines, genera et species redacta tabulisque aeneis illustrata (in Latin) (6th ed.). Stockholmiae (Stockholm): Godofr, Kiesewetteri. pp. 16, 28.

Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturæ per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Volume 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 158.

Liu, Yi-Ping; Wu, Gui-Sheng; Yao, Yong-Gang; Miao, Yong-Wang; Luikart, Gordon; Baig, Mumtaz; Beja-Pereira, Albano; Ding, Zhao-Li; Palanichamy, Malliya Gounder; Zhang, Ya-Ping (2006), "Multiple maternal origins of chickens: Out of the Asian jungles", Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 38 (1): 12–19.

Madge, S.; Philip J. K. McGowan; Guy M. Kirwan (2002). Pheasants, Partidges and Grouse: A Guide to the Pheasants, Partridges, Quails, Grouse, Guineafowl, Buttonquails and Sandgrouse of the World. A&C Black.

Mayr, G. 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance. Topics in Paleobiology, Wiley Blackwell. West Sussex.

Marino, L. 2017. Thinking chickens: a review of cognition, emotion, and behavior in the domestic chicken. Animal Cognition, doi: 10.1007/s10071-016-1064-4.

McGowan, P.J.K., Kirwan, G.M. & Boesman, P. (2019). Green Junglefowl (Gallus varius). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

McGowan, P.J.K. & Kirwan, G.M. (2019). Grey Junglefowl (Gallus sonneratii). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

McGowan, P.J.K. & Kirwan, G.M. (2019). Red Junglefowl (Gallus gallus). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

McGowan, P.J.K., Kirwan, G.M. & Boesman, P. (2019). Sri Lanka Junglefowl (Gallus lafayettii). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Morejohn, G. Victor (1968). "Breakdown of Isolation Mechanisms in Two Species of Captive Junglefowl (Gallus gallus and Gallus sonneratii)". Evolution. 22 (3): 576–582.

Morejohn, G. V. (1968). "Study of the plumage of the four species of the genus Gallus". The Condor. 70 (1): 56–65.

Nishibori, M.; Shimogiri, T.; Hayashi, T.; Yasue, H. (2005). "Molecular evidence for hybridization of species in the genus Gallus except for Gallus varius". Animal Genetics. 36 (5): 367–375.

Perry-Gal, Lee; Erlich, Adi; Gilboa, Ayelet; Bar-Oz, Guy (2015). "Earliest economic exploitation of chicken outside East Asia: Evidence from the Hellenistic Southern Levant". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (32): 9849–9854.

Peters, James Lee, ed. (1934). Check-list of Birds of the World. Volume 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 118.

Peterson, A.T. & Brisbin, I. L. Jr. (1999), "Genetic endangerment of wild red junglefowl (Gallus gallus)", Bird Conservation International, 9: 387–394.

Piper, Philip J. (2017). "The Origins and Arrival of the Earliest Domestic Animals in Mainland and Island Southeast Asia: A Developing Story of Complexity". In Piper, Philip J.; Matsumura, Hirofumi; Bulbeck, David (eds.). New Perspectives in Southeast Asian and Pacific Prehistory. terra australis. 45. ANU Press.

Pritchard, Earl H. "The Asiatic Campaigns of Thutmose III". Ancient Near East Texts related to the Old Testament. p. 240.

Roehrig, Catharine H.; Dreyfus, Renée; Keller, Cathleen A. (2005). Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 268.

Sacci, MA; K Howes; K Venugopal (2001). "Intact EAV-HP Endogenous Retrovirus in Sonnerat's Jungle Fowl". Journal of Virology. 75 (4): 2029–2032.

Sherwin, C.M.; Nicol, C.J. (1993). "Factors influencing floor-laying by hens in modified cages". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 36 (2–3): 211–222.

Siddharth, Biswas (2014). "Gallus gallus domesticus Linnaeus, 1758: Keep safe your domestic fowl from your domestic foul". Ambient Science. 1 (1): 41–43.

Smith, Jamon. Tuscaloosanews.com "World’s oldest chicken starred in magic shows, was on 'Tonight Show’" Archived February 20, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Tuscaloosa News (Alabama, USA). August 6, 2006.

Smith, Page; Charles Daniel (April 2000). The Chicken Book. University of Georgia Press.

Stonehead. "Introducing new hens to a flock " Musings from a Stonehead". Stonehead.wordpress.com. Archived from the original on August 13, 2010.

Storer, R. W. (1988). Type Specimens of Birds in the Collections of the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. University of Michigan, Miscellaneous publications No. 174.

Storey, A.A.; et al. (2012). "Investigating the global dispersal of chickens in prehistory using ancient mitochondrial DNA signatures". PLoS ONE. 7 (7): e39171.

"Top cock: Roosters crow in pecking order". Archived from the original on January 15, 2018. Retrieved January 14, 2018.

Wong, GK; et al. (December 2004). "A genetic variation map for chicken with 2.8 million single-nucleotide polymorphisms". Nature. 432 (7018): 717–722.

#Gallus#Chicken#Dinosaur#Bird#Junglefowl#Birds#Dinosaurs#Birblr#Palaeoblr#Factfile#Terrestrial Tuesday#Pheasant#Galloanseran#Landfowl#Quaternary#Neogene#Eurasia#Australia & Oceania#India & Madagascar#Omnivore#Gallus gallus#Gallus varius#Gallus lafayettii#Gallus sonneratii#Green Junglefowl#Grey Junglefowl#Sri Lankan Junglefowl#Red Junglefowl#Gallus aesculapii#paleontology

762 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anurophasis monorthonyx

By Carlos N. G. Bocos

Etymology: Tail-Lacking Pheasant

First Described By: van Oort, 1910

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Galloanserae, Pangalliformes, Galliformes, Phasiani, Phasianoidea, Phasianidae, Pavoninae, Tetraogallini

Status: Extant, Near Threatened

TIme and Place: Since 10,000 years ago, in the Holocene of the Quaternary

Snow Mountain Quail live entirely in the Snow Mountains of Irian Jaya in New Guinea

Physical Description: Snow Mountain Quail are adorable little round birds, ranging in size from 25 to 28 centimeters in length. They have small heads and tiny, pointed beaks, with large round bodies. They do not have large tails - as you would assume from their names - but instead have a small tuft of feathers in the shape of a triangle on the ends of their bodies. They also have short, stubby feet. The males are reddish, with brown backs and brown striping on their bodies. The females are more pale, but also with brown backs and brown striping.

Diet: These quail feed mainly on flowers, leaves, seeds, foliage, and sometimes caterpillars.

By Charles Davies, in the Public Domain

Behavior: Snow Mountain Quail aren’t the most social pheasant species, usually only foraging in small groups of 2 to 3 individuals. They make small, noisy squeals when flustered, and repeated squee-ing calls when alarmed. They do not migrate, though they do move back and forth along the elevation due to predator activity. They make nests on the edge of grass tussocks, usually in September; where they lay three pale brown eggs with dark brown spots.

Ecosystem: Snow Mountain Quail are known from grassland and scrubland in the mountains, between 3100 and 3800 meter elevations. This is an extremely remote - and chilly - environment.

By Romain Risso, CC BY-SA 3.0

Other: Snow Mountain Quail are mainly near threatened due to the extremely limited and unique nature of its habitat. It is also not helped by the fact that the Indonesian Government has not granted protected status to these birds. More work is needed to protect these adorable little birds.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

BirdLife International (2012). "Anurophasis monorthonyx". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Jobling, J. A. 2010. The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. Christopher Helm Publishing, A&C Black Publishers Ltd, London.

McGowan, P.J.K., Kirwan, G.M. & Boesman, P. (2019). Snow Mountain Quail (Anurophasis monorthonyx). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

#Anurophasis monorthonyx#Anurophasis#Snow Mountain Quail#Quail#Dinosaur#Bird#Birds#Pheasant#Galliform#Galloanseran#Birblr#Factfile#Terrestrial Tuesday#Herbivore#quaternary#Australia & Oceania#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature#Landfowl

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

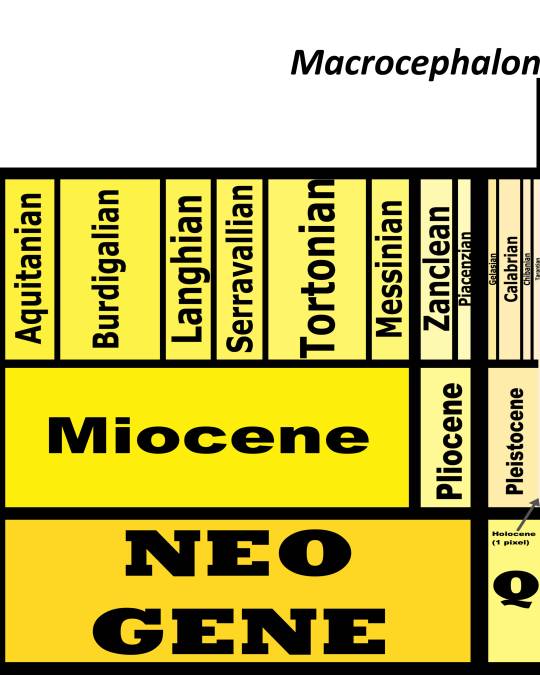

Macrocephalon maleo

By Ariefrahman, CC BY-SA 4.0

Etymology: Great Head

First Described By: Müller, 1846

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Galloanserae, Pangalliformes, Galliformes, Megapodiidae

Status: Extant, Endangered

Time and Place: Within the last 10,000 years, in the Holocene of the Quaternary

Maleos are known entirely from the island of Sulawesi in Indonesia

Physical Description: Maleos are large landfowl, reaching 55 centimeters in length. These are large, round birds with skinny necks and odd looking heads - they have black crests on the tops of their heads that flop over the back, and little red bands at the top of their beaks. The beaks of Maleos are thick and grey, and they have primarily brown heads. Their backs are black, as are their wings and tails, but their bellies are white; and they have long, grey legs. In addition to all of this, Maleos have orange rings around their eyes that are extremely noticeable. The young tend to have black heads in addition to these features.

Diet: Maleos feed on a variety of fruits, seeds, insects, and other invertebrates.

By Stavenn, CC BY-SA 3.0

Behavior: Maleos are Megapodes, which means they are one of the only groups of dinosaurs that don’t take care of their young! Instead, Megapodes make giant mound-nests which use geothermal energy and solar-heat in order to incubate the eggs. Maleos are monogamous, mating with only one individual per season (and potentially per life, but they aren’t very well studied), and the pair builds the nest mound together, lays the eggs, and leaves. Around ten eggs are laid per year, though some may lay as many as thirty. The eggs incubate for nearly three months; when the young hatch, they rapidly lose a lot of weight, before beginning to chow down on as much food as possible and growing rapidly for the next two months. They reach sexual maturity themselves at around two years of age. They can live for up to 23 years.

By BronxZooFan, CC BY-SA 4.0

These are noisy birds, making a wide variety of calls including brays, rolls, and quacking - to the point of sounding rather surreal in some situations. They tend to spend most of their time foraging with their mate, walking around and gathering the food off of the ground. They do not migrate, but they also do move around the island each year, not sticking in one place or placing their nests in the same sites from year to year.

Ecosystem: These megapodes live primarily in lowland and hill jungle, going to the beaches for their breeding or in forest clearings with extensive amounts of sand. They usually roost in trees high off of the ground. Maleos are preyed upon by humans, pigs, monitor lizards, and crocodilians.

By Ariefrahman, CC BY-SA 4.0

Other: Maleos are endangered, with only potentially 14,000 individuals left with a rapidly declining population. The reasons for this seem to be due to human exploitation, egg hunting by humans and introduced mammalian predators, and extensive habitat loss. This is also illegal, as much of that lost habitat is protected - as are the eggs of this species, which are being collected in the thousands. Since they are a delicacy, and not a food source staple, this practice must be condemned and hopefully further regulation can help to increase Maleo populations.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Elliott, A. & Kirwan, G.M. (2019). Maleo (Macrocephalon maleo). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Foley, James A. (March 9, 2013). "Rare Maleo Eggs Successfully Incubated And Hatched At Bronx Zoo". Nature World News. Nature World News.

#Macrocephalon maleo#Macrocephalon#Maleo#Megapode#Dinosaur#Factfile#Birds#Dinosaurs#Galloanseran#Galliform#Landfowl#Pheasant#Quaternary#Birblr#Australia & Oceania#Omnivore#terrestrial tuesday#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cyanochen cyanoptera

By Brent Moore, CC BY 2.0

Etymology: Dark Blue Goose

First Described By: Bonaparte, 1856

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Galloanserae, Anseriformes, Anseres, Anatoidea, Anatidae

Status: Extant, Vulnerable

Time and Place: Within the last 10,000 years, in the Holocene of the Quaternary

The Blue-Winged Goose is only known from the Horn of Africa

Physical Description: Blue-Winged Geese look very similar to other geese in terms of proportions - with round bodies, short tails, and long necks. Their heads are small, as in other geese, with small triangular bills. They also look like most non-canadian geese by being softer and rounder in general angles and shape. They differ from other geese primarily in color - they have grey heads and brown bodies, but the undersides of their wings are distinctively powder-blue in color, with black and green contrasting feathers around the blue. The males have brighter colors than the females, and are in general heavier - though they range between 60 and 75 centimeters in length in both sexes. The tails of these birds are usually black. The juveniles differ from adults in being duller in color still.

By Dick Daniels, CC BY-SA 3.0

Diet: Blue-Winged Geese feed mainly on grasses, sedges, water-edge plants, and sometimes invertebrates.

Behavior: Despite being geese - and even feeding on aquatic food from time to time - Blue-Winged Geese seldom swim! Instead, they will graze along the river bank, searching for food while keeping their feet firmly planted on dry land. They also mostly do this during the night, spending their days asleep! Even though it is reluctant to both swim and fly, it is good at both, but will rarely run away from humans approaching it. They are social birds, forming flocks year-round, which are filled with high-pitched whistles and penk-penk-penk calls. They do move flocks occasionally during different seasons - and go to higher altitudes during the dry winter to breed.

By Charles J. Sharp, CC BY-SA 4.0

They begin breeding during the dry season, usually forming single pairs to build nests on the ground hidden by the vegetation. The female does most of the incubation alone, laying four to seven eggs and incubating them for about a month. The chicks hatch very fluffy and brown-black, taking around three months to fledge. They then join the flock, and become sexually mature at around two years of age. These flocks can include hundreds of geese, and are a noticeable feature in the Ethiopian landscape.

Ecosystem: Blue-Winged Geese primarily live in grassy meadows and pastures at mid to high levels of elevation, usually near rivers and lakes and pools. It will avoid entering deep water, though it will venture into waterlogged soils with dense vegetation.

By Dick Daniels, CC BY-SA 3.0

Other: Blue-Winged Geese might be common, but they have a very unfortunately restricted range - which means there are probably less than 10,000 sexually mature individuals alive today, which are specially affected by drainage and habitat conversion by local populations. Luckily, local religious beliefs prevent it being hunted, however immigrants into Ethiopia are starting to hunt the Blue-Winged Geese which is causing increased pressure on this bird. Clearly, protection is needed and increased monitoring of its population. This is especially important as Blue-Winged Geese is actually a very unique bird - it’s not a goose at all, but a duck! It is closely related to Hartlaub’s Duck, another unique African species of waterfowl, indicating an isolated clade of African waterbirds evolved similarly to waterbirds around the world. More research is needed to better understand these birds - but they must be protected so we can do so.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Carboneras, C. & Kirwan, G.M. (2019). Blue-winged Goose (Cyanochen cyanoptera). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Jobling, J. A. 2010. The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. Christopher Helm Publishing, A&C Black Publishers Ltd, London.

Johnson, Kevin P.; Sorenson, Michael D. (1999). "Phylogeny and biogeography of dabbling ducks (genus Anas): a comparison of molecular and morphological evidence" (PDF). Auk. 116 (3): 792–805.

Kingdon, J. (1989). Island Africa: The Evolution of Africa's Rare Plants and Animals. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Madge, Steve; Burn, Hilary (1987). Wildfowl: an Identification Guide to the Ducks, Geese and Swans of the World. London: Christopher Helm.

Stidham, T. A., X. Wang, Q. Li and X. Ni. 2010. A shelduck coracoid (Aves: Anseriformes: Tadorna) from the arid early Pleistocene of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, China. Palaeontologia Electronica 18(2.24A):1-10.

#Cyanochen cyanoptera#Cyanochen#Blue-Winged Goose#Goose#Dinosaur#Bird#Birds#Duck#Waterfowl#Galloanseran#Quaternary#Factfile#Birblr#Africa#Herbivore#Water Wednesday#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Miortyx

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Miocene Quail

First Described By: Miller, 1944

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Galloanserae, Pangalliformes, Galliformes, Phasiani, Odontophoridae

Referred Species: M. teres, M. aldeni

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Between 23 and 16 million years ago, from the Aquitanian to the Burdigalian ages of the Miocene of the Neogene

Miortyx is known from the Batesland Formation and middle member of the Sharp’s Formation of South Dakota

Physical Description: Miortyx is the oldest known member of the American Quail, a group of small birds with similar habits (but far distance in relation) to Old World Quail. These are shy, diurnal, terrestrial birds, with generalist diets. As such, Miortyx probably resembled its modern relatives in most ways, with round bodies and tiny heads. They probably also had tiny beaks and only somewhat decent flight ability. They probably also had short, boxy wings, like other American Quail. These birds were larger than their modern relatives, making them an interesting transitional form between larger fowl (such as pheasants) that these quail evolved from, and the smaller quail we have today. Both species are known from ends of humeri, making it difficult to say more about them.

Diet: A mixture of grains, seeds, and invertebrates that it could pluck from the ground.

Behavior: Miortyx would probably have behaved similar, if not identical, to living quail, spending most of its time walking around and bobbing its head as it tried to peck up food from the ground. They probably lived in large flocks, which would rarely rely on flight to get away, instead running away in a silly and bobbing fashion. When flying, it would have been an awkward, sporadic sort of flight. They would have taken care of their young for at least some time, and the young were probably precocial.

By Scott Reid

Ecosystem: Miortyx lived across the transition of environments in South Dakota during the Early through the Middle Miocene. During this time, grasslands were starting to grow, creating the famed American plains. Still, forests were a major feature of the ecosystem. Miortyx aldeni lived in the middle ecosystem of the Sharp’s Formation, a braided river channel in an extensive forest. This forest was in the middle of a valley, with a lot of different types of trees like sycamore, poplar, alder, and ash. Here, it lived alongside other dinosaurs such as Arikarornis, an Old World Vulture (in the New World!), and the large flightless bird of prey Bathornis (a kind that convergently evolved a very similar lifestyle to the Terror Birds of the South). There were also a variety of mammals such as proto-horses, primates, marsupials, rabbits, deer, rodents, and predatory mammals.

The later Batesland formation featured the growth of grasslands into the area, though where Miortyx teres was found was still forested. This was a stream system flowing out of nearby rivers and lakes, with well-developed surrounding woodland featuring many of the same plants as the earlier area. Nearby grasslands were bleeding in, though it was still more forested than what one would see today. Here there were many other dinosaurs such as the Chachalaca Boreortalis, crakes like Ortalis, grouse Typmanuchus, ducks like Dendrochen and Querquedula, a swan Paranyroca, an Old World Vulture Palaeoborus, an owl Strix dakota, and even the swimming-flamingo Megapaleolodus. There were also countless mammals like a startling number of rodents, many kinds of hoofed mammals including horses, predatory mammals, rabbits, and hedgehogs and shrews.

Other: Miortyx is the oldest record of American Quail, making it an important find for that group’s biogeographical history.

Species Differences: M. aldeni is slightly larger than its cousin M. teres, and also older, coming from the Middle Sharp’s Formation rather than the later Batesland Formation.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Ducey, J. E. 2012. Fossil Birds of the Nebraska Region. Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences and Affiliated Societies 130: 83 - 96.

Farmer, D. 2012. Avian Biology, Volume VIII. Nature.

Jobling, J. A. 2010. The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. Christopher Helm Publishing, A&C Black Publishers Ltd, London.

Johnsgard, P. A. 2008. Evolution and Taxonomy. Grouse and Quails of North America.

Miller, A. H. 1944. An avifauna from the lower Miocene of South Dakota. University of California Publications, Bulletin of the Department of Geological Sciences 27(4):85-100

Olson, S. L. 2012. The Fossil Record of Birds. In Avian Biology.

#Miortyx#Quail#Dinosaur#Bird#Prehistoric Life#Prehistory#Paleontology#Palaeoblr#Birblr#Factfile#Miortyx teres#Miortyx aldeni#Galliform#Galloanseran#Terrestrial Tuesday#Omnivore#North America#Neogene

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

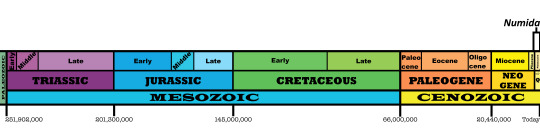

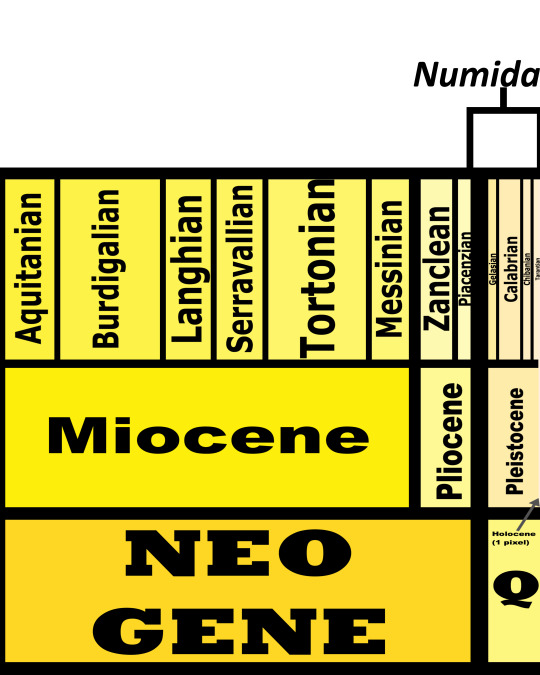

Numida meleagris

By Diego Delso, CC BY-SA 4.0

Etymology: From Numidia

First Described By: Linnaeus, 1764

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Galloanserae, Pangalliformes, Galliformes, Phasiani, Numididae

Status: Extant, Least Concern

Time and Place: Numida has been known since about 2.6 million years ago, in the Piacenzian of the Pliocene of the Neogene, through today

The Helmeted Guineafowl is known from across sub-Saharan Africa

Physical Description: The Helmeted Guineafowl is an exceptionally distinctive bird, with a very round, large body, and a small but visually appealing head. They range from 53 to 63 centimeters in length, with the females slightly smaller than the males in terms of size, but otherwise identical in color. Their bodies are dark brown to black, with distinctive rows of white spots across all parts of it; they have long grey legs, with large flat feet. They have tiny heads with different colors, depending on the subspecies - the West African population has a white head, with a red wattle under the chin; the Saharan population has a blue head with a red patch on the top of the head; Reichenow’s population has red patches on the top and the bottom but also a blue head; and similar patterns can be seen on the Tufted population. All of these birds have an orange to brown crest on the top of the head, leading to its common name of Helmeted. The young start out brown and yellow striped, with a little brown patch on the top of the head; they begin to turn into a dull dark brown as teenagers, before transitioning into adult plumage.

By Roland Hunziker, CC BY-SA 2.0

Diet: The Helmeted Guineafowl is a true omnivore, feeding on a variety of seeds, tubers, bulbs, roots, berries, flowers, insects, snails, ticks, worms, and millipedes. Though they eat more plants than animals, it seems that is mainly due to relative abundance.

Behavior: The Helmeted Guineafowl is an extremely social bird, forming flocks of about 25 birds that spend all their time together - foraging and nesting; sometimes these flocks can even grow up to 100 individuals. They don’t fly often, but rather run about from place to place. They forage on the ground, scratching with their feet to dig up available food. These flocks are extremely complex, with the highest ranking males fighting to organize the flock’s daily activities, and the two highest ranking males will work together to fight off intruders into the habitat. Breeding females usually associated mainly with the high ranking males, especially the highest; leaving lower ranking males to lead the flock during this time when the higher ranking males help with rearing the chicks.

By Brian Gratwicke, CC BY 2.0

These birds begin breeding right after it rains or during the rainy season, which varies across its range. They are monogamous for the mating season only; these pairs are not maintained after the year is up. Early on in the season, even, the males will try to mate with multiple females. The nests are scrapes in the ground, made by the females and lined with grass and feathers - usually these scrapes are made in areas with long grass and hidden under brush. Six to twelve eggs are laid on successive days; sometimes more than one female will lay in a single nest, leading to up to fifty eggs. These eggs are usually yellowish to pale brown, with dark specking. The eggs are incubated by the females for about a month; the male then takes over in brooding the chicks the first two weeks after hatching. They can then fly poorly at two weeks; they fully fledge at a month; and they reach adult size after thirty weeks. The females are sexually mature at around that time. The family groups rejoin the larger flock when the chicks are about one to three months of age. Most of the chicks die, especially in cold weather.

By Snowmanradio, CC BY-SA 2.0

The Helmeted Guineafowl makes loud, cackling calls with a variety of intensities, including at roosts; they contact each other with more metallic clanking and far-carrying cheer-ing. The females will make nasal “ka-bak” calls that can increase in pitch to call to males. They don’t migrate, but rather, stay within one territory for their whole lives within their flocks. They do move to find sources of drinking water, as well as roosting sites.

Ecosystem: The Helmeted Guineafowl can be found all over the place, from the edges of forests, to the savanna, to thorn scrub, to steppe, to subdesert, to woodlands. They are especially common in the savanna. They are generally limited by the availability of drinking water and suitable nesting sites in trees and bushes. They are found occasionally in human-cultivated areas, even suburbs. They are usually found below 3000 meters high in elevation, and can be found in very large numbers around watering holes.

By Bernard DuPont, CC BY-SA 2.0

Other: The Helmeted Guineafowl is not, on the whole, threatened; there may be up to a million of these birds all over Africa. That being said, plenty of populations are more threatened than others, especially due to hunting and egg collecting. At least a few populations are more threatened than others. They have also been introduced to the Americas, specifically to aid in controlling Lyme Disease due to their propensity for feeding on ticks. These birds are often domesticated by people and served for their meat and eggs.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Jobling, J. A. 2010. The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. Christopher Helm Publishing, A&C Black Publishers Ltd, London.

Martínez, I. & Kirwan, G.M. (2019). Helmeted Guineafowl (Numida meleagris). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

#Numida#Numida meleagris#Dinosaur#Helmeted Guineafowl#Fowl#Galliform#Guineafowl#Dinosaurs#Bird#Birds#Birblr#Palaeoblr#Factfile#Quaternary#Neogene#Africa#Omnivore#Galloanseran#Terrestrial Tuesday#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

248 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chendytes lawi

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Goose Diver

First Described By: Miller, 1925

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Galloanserae, Anseriformes, Anseres, Anatoidea, Anatidae, Anatinae

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Between 126,000 and 250 BCE, from the Tarantian of the Pleistocene through the Holocene

Chendytes is known from a variety of locations along the west coast of North America - the Palos Verdes Sand Formation, the San Pedro Sand Formation, the San Miguel Island deposits, the Daisy Cave deposits, and the Port Orford Formation, among others.

Physical Description: Chendytes was a fascinating and odd duck, about the size of living swans - so approximately 1.5 meters long in terms of its body size. They were shaped almost identically to the Hesperornithines of old - with streamlined bodies for diving and short legs for propelling their swimming, they also had small wings that were essentially useless for any activity. As such, like the dead Hesperornithines and the living grebes, it was extremely well adapted for diving, which is precisely what they spent their lives doing. Chendytes had a long neck, like modern geese, and a fairly stout body - also like living geese. It differed from living geese in having stronger legs for diving, and almost no wings at all.

Diet: Chendytes would have mainly eaten fish and other aquatic organisms as it dived through the sea.

By Apokryltaros, CC BY 2.5

Behavior: Chendytes probably spent most of its time diving and swimming through the water, in search of sources of food. It would have rarely gone on land, being ill-suited to walking, but instead done most of its business in the ocean. It would have propelled itself fast in pursuit of prey, as well as to escape predators such as sharks, whales, and even large ray-finned fish. It probably migrated to nest - with large concentrations of eggs known from the Channel Islands of California, it even seems probable that these ducks would have migrated all the way there to breed, like many other aquatic birds do today. They probably lived in very large flocks, diving and swimming about together like living penguins.

Ecosystem: The coast of North America was very similar in the past to today, but with more dramatic climate movements given the fluctuations of the Ice Age, and a different cast of living creature characters. There were giant, Sabretooth Salmon; robust and terrifying carnivorous mammals like Sabretooth Cats and Dire Coyotes; mammoths and mastodons; and a variety of interesting dinosaurs such as giant Condors, tiny Dow’s Puffins, and the bulky Californian Turkey. In short, the coast of California during the time of Chendytes would have resembled today, while still being very odd and foreign - filled with a variety of megafauna, both dinosaur and not.

By Scott Reid

Other: Interestingly enough, even though Chendytes was adapted so thoroughly for diving, it is more closely related to the dabbling ducks than to the diving ducks - indicating it was a strange evolutionary offshoot of the dabbling duck group, adapting to the rapidly changing conditions of the late Quaternary Ice Age. It probably went extinct due to a mixture of habitat loss and human hunting, as people became more common along the coast - there is an extensive record of it being hunted and exploited by humans for at least 8,000 years, one of the longest such records known. .

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Buckner, J. C., R. Ellingson, D. A. Gold, T. L. Jones, D. K. Jacobs. 2018. Mitogenomics supports an unexpected taxonomic relationship for the extinct diving duck Chendytes lawi and definitively places the extinct Labrador Duck. Molecular Phylogenetics Evolution 122: 102 - 109.

Jones, T. L., J. F. Porcasi, J. M. Erlandson, H. Dallas Jr., T. A. Wake, R. Schwaderer. 2008. The protracted Holocene extinction of California’s flightless sea duck (Chendytes lawi) and its implications for the Pleistocene overkill hypothesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105 (11): 4105 - 4108.

Miller, L. 1925. Chendytes, a diving goose from the California Pleistocene. Condor 27:145-147.

Jobling, J. A. 2010. The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. Christopher Helm Publishing, A&C Black Publishers Ltd, London.

#Chendytes lawi#Chendytes#Duck#Dinosaur#Bird#Birds#Palaeoblr#Birblr#Piscivore#North America#Quaternary#Water Wednesday#galloanseran#Anseriform#Factfile#Dinosaurs#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pucrasia macrolopha

By Prateik Kulkarni, CC BY-SA 4.0

Etymology: Pheasant

First Described By: G. R. Gray, 1841

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Galloanserae, Pangalliformes, Galliformes, Phasiani, Phasianoidea, Phasianidae, Phasianinae, Tetraonini

Status: Extant, Least Concern

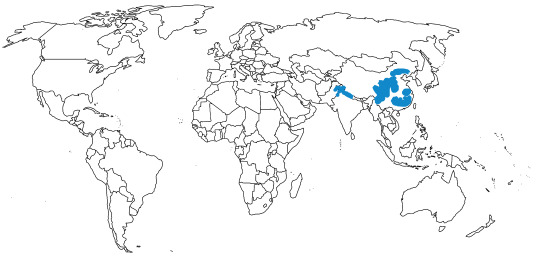

Time and Place: Within the last 10,000 years, in the Holocene of the Quaternary

The Koklass Pheasant is known from India and Southeast Asia

Physical Description: The Koklass Pheasant is a large bird, ranging between 52.5 to 64 centimeters in length, with the males on average larger than the females. The birds are also sexually dimorphic in terms of body color, with the males supporting large, spikey crests and distinctive striping along their sides - while the females are more mottled and brown. The males come in a variety of plumage colors - in general, they have green faces with green and black crests, and then have varieties of grey, black, white, and red bodies and necks, with black striping (or white striping if their bodies are black). The females have light brown stripes near their eyes and a variety of brown over the rest of their bodies. The juveniles tend to resemble the females until the first year of age, when the males begin getting their adult colors.

By Harry Rawat, CC BY-SA 4.0

Diet: The Koklass Pheasant eats a variety of seeds, berries, insects, and worms.

Behavior: This particular variety of pheasant is rarely seen foraging, being quite shy and flying away at the first sign of trouble, but it tends to scrape at the ground while searching for food. They especially love foraging around ferns. They form loose flocks occasionally, but primarily feed alone or in pairs in the early morning and late afternoon. They defend their territories extensively, making rhythmic “kraa-krra-kraara” calls over and over again with some variation based on home territory and individual. They also make a variety of other clucks and barks and high pitched alarm calls.

By Sheila Mary Castelino, CC BY-SA 4.0

This pheasant will call for mates at dawn starting in November and going through June. They form monogamous pairs, which nest from April to June - making a scrape in the ground under dense cover for the nest, the Koklass Pheasant then lines this scrape with twigs and leaves. They lay five to seven yellow eggs with reddish-brown marks, which are incubated for a month by the female. These birds do move downward in terms of elevation as it gets colder and the higher altitudes are more difficult to live in.

By P. Jeganathan, CC BY-SA 4.0

Ecosystem: The Koklass Pheasant lives in coniferous forest, especially in steep terrain, being associated with the HImalayan mountains; they also enjoy areas with dense bamboo. They tend to roost in the trees of these forests.

Other: The Koklass Pheasant is not endangered and is quite common throughout its very wide range, though local extinctions based on habitat loss and human hunting have been reported.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Jobling, J. A. 2010. The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. Christopher Helm Publishing, A&C Black Publishers Ltd, London.

McGowan, P.J.K., Kirwan, G.M. & Boesman, P. (2019). Koklass Pheasant (Pucrasia macrolopha). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

#Pucrasia#Pucrasia macrolopha#Pheasant#Koklass Pheasant#Dinosaur#Dinosaurs#Bird#Birds#Galliform#Galloanseran#Terrestrial Tuesday#Omnivore#Quaternary#Eurasia#India and Madagascar#factfile#Birblr#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

Polarornis gregorii

By José Carlos Cortés

Etymology: Polar Bird

First Described By: Chatterjee, 2002

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Galloanserae, Anseriformes, Vegaviidae

Status: Extinct

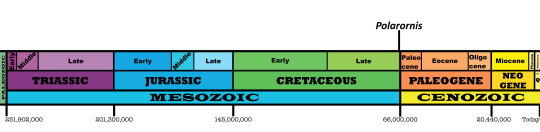

Time and Place: 66 million years ago, in the Maastrichtian age of the Late Cretaceous

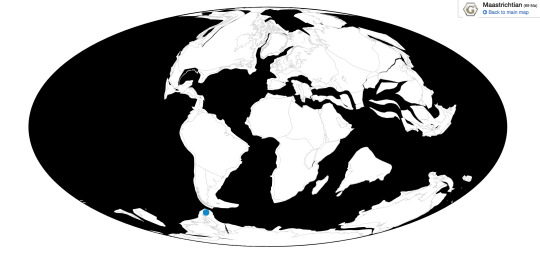

Polarornis is known from the Lopez de Bertodano Formation of Seymour Island, Antarctica

Physical Description: Polarornis was a fairly long duck-like dinosaur, around 80 centimeters in body length, though its wingspan and tail length are unknown. It would have had a fairly long looking body, with a long head and long neck (there’s a reason it was mistaken as a loon); the length of its legs is fairly unknown, but it had a short thigh and also had strong calf muscles. It had a long, narrow, toothless beak as well. Its wings aren’t well known, and it had very dense bones, so it may have had small wing. This makes it a fascinating case of a duck that evolved to look weirdly loon-like - convergent evolution is amazing!

Diet: Polarornis probably fed mainly on fish and aquatic invertebrates, especially given how many were there in its environment!

Behavior: Polarornis seems to have been flightless or nearly so, and probably spent most of its time in the water and as a diving dinosaur. This makes it a bird very similar to modern penguins and to contemporary hesperornithines! It would have probably used its legs extensively to kick and paddle through the water in search of food. As a diving bird in the far south, it also probably would have spent a lot of time preening, to keep its feathers waterproof and able to keep in warm air to protect it from the environment.

As an Anseriform, it is likely that Polarornis would take care of its young, and live in family groups; Polarornis young grew very quickly, especially for dinosaurs at the time, which would help it in the highly seasonal climates of Antarctica at the time. but beyond that it’s difficult to say what it would have acted like, beyond “duck-like”.

By Scott Reid

Ecosystem: Polarornis lived in the Lopez de Bertodano Formation, an antarctic shorline ecosystem from right before the end-Cretaceous extinction. Though Polarornis is known from the layer right before the extinction, nothing else is known from the same layer except some invertebrates such as bivalves, gastropods, and cephalopods. This was a mild arctic coastline ecosystem, with maritime climate and the higher temperature of the planet making it warmer than it would be today, but still very chilly for Mesozoic standards. Here there were many mosses, hornworts, liverworts, ferns, clubmosses, conifers, proteas, and beech trees. Other dinosaurs known from the layer just below Polarornis - and thus may have been around with Polarornis, we can’t entirely rule it out - includes the ornithopod Morrosaurus, the Anseriform Conflicto, and another Vegaviid Vegavis - in fact, I wouldn’t be surprised if Polarornis was the descendant of Vegaviis! There was also the Elasmosaurid Aristonectes and the Mosasaurid Kaikaifilu, which may have fed upon Polarornis. The Lopez de Bertodano Formation is thus a beautiful snapshot of the evolution of avian dinosaurs right up to the extinction of their nonavian relatives.