#funerary statuette

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

~ Funerary Statuette: Bird Trainer.

Place of origin: China

Period: Six Dynasties (A.D. 220-589)

Date: A.D. 5th-6th

Medium: Gray terracotta, traces of paint and white slip

#ancient#ancient art#history#museum#archeology#ancient sculpture#ancient history#archaeology#sculpture#5th century#6th century#china#Chinese#asian#asian art#funerary statuette#bird trainer#six dinasties#terracota

866 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Funerary figure of a servant, 1206BC-220AD, China.

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Statuette of a Woman

Greek, about 450 BCE

Industrious workshops in Boeotia produced thousands of mold-made terracotta statuettes for religious, decorative, and funerary use for several centuries. This engaging statuette represents a woman whose down-turned eyes and pursed lips lend her a dejected air. Her hair is drawn up on the crown of her head and wrapped in a length of patterned cloth. She is clothed in a full-length, sleeveless dress and adorned with a necklace with seven pendants and a pair of bracelets on each arm. Remarkable for the preservation of its bold red, vivid yellow, and black coloration, this figurine reminds viewers that many ancient sculptures were once brightly painted.

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

Amenhotep I or Ramesses II wearing the Khepresh

This striding statuette of a New Kingdom king, depicts the king in a kilt (shendyt) adorned with an elaborate belt, a usekh collar around his neck, and most notably, the "Blue Crown of War", known to the Egyptians as the "Khepresh" upon his head, which is given a realistic glisten by the addition of rounded blue faïence.

The statue is often associated with Amenhotep I, but others, including the Louvre, where this statue now resides, label this piece as Ramesses II. This may be confusing, but it was not uncommon for kings to reuse or usurp relics from past monarchs, in fact Ramesses II is very well known among scholars for his usurping of past monuments and statues, especially those made during the reign of king Amenhotep III.

However, a further reason for this confusion when it comes to identifying this piece may or almost certainly comes from the deification of Amenhotep I within the Deir el-Medina region, where this piece was found.

Both Amenhotep I and his mother Ahmose-Nefertari became deified after their deaths. Ahmose-Nefertari outlived her son by approximately a year at the least, and became worshipped alongside her son for centuries after. Therefore, depictions of both Amenhotep I and his mother Ahmose-Nefertari are found in tombs and among other types of relics and funerary items dating from much later from their life-times. Thus, explaining statues and other depictions of either of the two dating from later king's reigns.

Read more

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

Archaeologists have uncovered dozens of ancient Egyptian tombs and numerous artifacts, including a remarkable set of objects made from gold foil.

An Egyptian archaeological mission coordinated by the Supreme Council of Antiquities unearthed 63 mud-brick tombs and some simple burials at the Tel el-Deir necropolis in New Damietta, a Mediterranean coast city in the country's north.

The tombs are thought to date to ancient Egypt's Late Period, which lasted from 664 to 332 B.C., the country's Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities announced in a statement.

Among these, researchers uncovered a "huge" tomb containing burials of people who appear to have been of high social class. Inside, archaeologists found a collection of gold foil artifacts in a variety of different forms, such as those shaped like religious symbols or figures.

The archaeological mission also uncovered a pottery vessel containing dozens of bronze coins from the later Ptolemaic era during the excavation, as well as a group of local and imported ceramic artifacts. The latter shed light on trade links between the ancient city of Damietta and other settlements along the Mediterranean coast.

The Ptolemaic era began following Alexander the Great's conquest of Egypt—then controlled by the Persians—in 332 B.C. A Hellenistic polity known as the Ptolemaic Kingdom was subsequently established in 305 B.C. and ruled Egypt until 30 B.C., when the region was conquered by the Romans.

Another intriguing find during the excavation in New Damietta was ushabti statuettes, small figurines used in ancient Egyptian funerary practices. They were placed in tombs in the belief that they would act as servants for the deceased in the afterlife.

The layout of the newly discovered tombs at Tel el-Deir has been seen in other ancient Egyptian tombs of the Late Period, the ministry said.

Mohamed Ismail Khaled, secretary-general of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, the latest discoveries at the Tel el-Deir necropolis highlight the fact that ancient Damietta was a center of foreign trade during different historical eras.

Earlier this month, archaeologists announced that a collection of ancient Egyptian artworks and inscriptions had been uncovered hidden below the waters of the Nile.

A joint Egyptian-French archaeological mission identified works in an area of the iconic river, near the city of Aswan, the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities said in a statement.

The settlement that existed in this location in ancient times was strategically significant, marking the southern frontier of pharaonic Egypt.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Issyk kurgan of the 'Golden Man' 6th-3rd C. BCE

"The Issyk kurgan, in south-eastern Kazakhstan, less than 20 km east from the Talgar alluvial fan, near Issyk, is a burial mound discovered in 1969. It has a height of six meters and a circumference of sixty meters. It is dated to the 4th or 3rd century BC. A notable item is a silver cup bearing an inscription. The finds are on display in Nur-Sultan. It is associated with the Saka peoples.

The burial complex located on the left bank of the Issyk Mountain River, 50 kilometers to the East to the Almaty city. The unique archaeological complex found by a small group of Soviet scientists led by archaeologist Kemal Akishevich Akishev in 1969. The burial ground consists of 45 large Royal mounds with a diameter of 30 to 90 and a height of 4 to 15 meters. The Issyk barrow is located in the Western half of the burial ground. Its diameter is 60 meters and its height is 6 meters.

Situated in eastern Scythia just north of Sogdiana, the kurgan contained a skeleton, warrior's equipment, and assorted funerary goods, including 4,000 gold ornaments. Although the sex of the skeleton is uncertain, it may have been an 18-year-old Saka (Scythian) prince or princess.

The richness of the burial items led the skeleton to be dubbed the "golden man" or "golden princess", with the "golden man" subsequently being adopted as one of the symbols of modern Kazakhstan. A likeness crowns the Independence Monument on the central square of Almaty. Its depiction may also be found on the Presidential Standard of Nursultan Nazarbayev.

There were two burials in the grave complex: the Central one and the Southern one (to one side). Unfortunately the Central burial site had been robbed but the side grave was undisturbed. The burial chamber in the side grave was constructed from spruce logs. The tomb and its contents remained intact and buried. The skeletal remains were found in the Northern half of the chamber. More than 4,000 gold items were found in the chamber, as well as iron sword and dagger, a bronze mirror, vessels made of clay, metal and wood, shoes, headdresses, gold rings, statuettes, bronze and gold weapons, and an inscribed silver bowl dating from the 6th to 5th century BCE. Many clothing ornaments made of gold, a headdress and shoes were found on and under the remains. Next to the remains were an arrow with a gold tip, a whip (the handle of which was wrapped with a wide ribbon of gold in a spiral pattern) and a bag containing a bronze mirror and red paint. Scientific research, particular that of the anthropologist O. I. Ismagulov, shows that the remains belong to a member of the Saka peoples of Semirecheye, who have a European appearance with an admixture of Mongoloid features. The age of the body at death is estimated at 16–18 years, and its sex is indeterminate. The form of clothing and method of burial suggest that "The Golden Man" was a descendant of a prominent Saks tribe leader, or a member of the Royal family.

A text was found on a silver bowl in Issyk kurgan, dated approximately VI BC. The context of the burial gifts indicates that it may belong to Saka tribes.

The Issyk inscription is not yet certainly deciphered, and is probably in a Scythian dialect, constituting one of very few autochthonous epigraphic traces of that language. János Harmatta, using the Kharoṣṭhī script, identified the language as a Khotanese Saka dialect spoken by the Kushans.

The Wikipedia page has a possible (partial?) deciphering of the Issyk inscription as: "The vessel should hold wine of grapes, added cooked food, so much, to the mortal, then added cooked fresh butter on".

...

Kazakhstan will rebury an iconic ancient warrior in a time capsule this year (2019), in the hope that future generations will be able to establish who he really was, Kazakh TV reports.

Since independence in 1991, he has become a symbol of Kazakhstan's national heritage. His armour takes pride of place in the national museum in Astana, and tours the world as a calling card of Kazakh culture.

The bones were only rediscovered recently at a forensic institute, stored in a cardboard box with a scribbled note reading "The Golden Man, May He Rest in Peace".

"We know his age and social status, while DNA tests could provide us with exhaustive data," researcher Dosym Zikiriya told Kazakh TV.

But Yermek Zhasybayev of the Issyk Museum held out little hope of this. "The bones are in a bad state. They have been kept in a cardboard box for 50 years and been exposed to all sorts of bacteria and viruses, including modern ones. It is now impossible to get a full DNA transcription - if only we had the skull, or just one tooth," he told the TV channel.

Scientists say their only hope is to seal the remains in a special time capsule to prevent any further decomposition, so that technological advances might allow future generations to glean more information about the long-dead warrior.

In recognition of the Golden Man's status, the capsule will be "ceremonially buried in keeping with ancient royal traditions", Kazakh TV said.

Archaeologists are confident that the remains date back to at least the 2nd-3rd century BCE, when south-eastern Kazakhstan was home to the Saka people, who are believed to have been part of the broader Scythian nomadic confederation.

They were gradually displaced by the arrival of the Kipchak Turk ancestors of the Kazakhs, but modern Kazakhstan has taken the Golden Man to its heart."

-taken from wikipedia and bbc

#saka#scythian#scythian gold#archaeology#anthropology#history#ancient history#antiquities#antiquity#artifacts#museums#ancient jewelry#pagan#6th century bce#3rd century bce

226 notes

·

View notes

Text

PF2e Character Concept: Mbe’ke Dwarf Investigator

Still reading ‘Lost Omens: The Mwangi Expanse’, and I really like the Mbe’ke? Just a lot. And I was thinking what kind of Mbe’ke character I’d like to make, and there’s just a couple of setting elements that I’d like to pull together here. Bear with me a bit:

The city of origin for this dwarf is going to be the Sky Citadel of Cloudspire. Initially, almost purely because of the Wellspring. The Wellspring is the water source at the base of the hollowed mountain bowl that is the city of Cloudspire, so deep that it’s rumoured to connect with the waters of the Darklands below, and blind abyssal fish often swim up into it. The Wellspring has two primary purposes: it’s the source of most of the city’s water, so fouling it has steep penalties, AND …

It's part of the funerary rites of at least Cloudspire dwarves and also possibly Mbe’ke in general. Not bodies, that would foul the waters. Bodies are cremated. But part of the funeral rites in Cloudspire involve a deceased dwarf’s family throwing a token in their name into the Wellspring, that their soul might return to the Darklands, the first homeland of the dwarves. If they’re poor, it might be just a stone with their name, but elaborate statuettes and carved liknesses are also thrown by richer families. And I thought …

Wouldn’t that would be a fabulous little thing for a dwarven adventurer to ask of their fellow party members? If I die here, will you take a stone in my name to the Wellspring, so that my soul will find home? A last request. If anyone makes it out, help guide my soul home.

So. I wanted a Cloudspire Mbe’ke. And that idea, the last request, tied up with another dark bit of history involving the Wellspring. During the War of Split Hearts, a massive civil war among the Mbe’ke a thousand years ago, the paranoid King Nkobe, believing his dead son had been poisoned instead of dying of disease, laid some groundwork and then spent nine days absolutely slaughtering everyone he believed had been involved. During the Nine Days of Blood, thousands of his people were arrested by masked enforcers, dragged to the bridges above Cloudspire, and beheaded, until the Wellspring beneath them ran red with gore, kicking off a massive civil war that only ended with cloud dragon interference and the deaths of King Nkobe and most of the aristocracy. For the last millennium, Mbe’ke society has had an elected council of kings and an elected high king, to avoid another King Nkobe ever happening again.

There’s also a fellowship … Mbe’ke society is broken up into fellowships, which are sort of like unions/guilds/electoral blocs. Dwarven society is divvied up by vocation, and the fellowships also support retired members, apprentices, dependents, and a few odd folks who are loosely connected to the profession but not actually part of it. There’s lots of loopholes so that people who need to be a part of a fellowship but who can’t actually do the profession can be supported anyway. And. There is a specific warrior fellowship that originated in the War of Split Hearts, called the Bloodmarked. Originally, they were people who survived the massacres of the Nine Days of Blood and who dedicated themselves to war in the aftermath, and these days they form a lot of the backbone of the faction of Mbe’ke’s who want to pursue the Corsair Wars against the Shackles Freecaptains to the death. To join the Bloodmarked fellowship, it’s not necessary but it is strongly traditional for a dwarf to have lost someone close to them to violence.

Now. I could make a Bloodmarked Mbe’ke. Pick a martial class and go for that. But. Another fellowship also caught my eye.

The Hall of Bells is the industrial core of Cloudspire, where most of the craft focused fellowships are found working the various foundries and forges. And among them is the Humble Fellowship. Who make pots and pans and parts, and who experiment with mass production and assembly lines. And there was a bit of me that thought …

Pathfinder has a background called Junk Collector. Which is what it sounds like. You make a living digging through rubbish and junk to find useable parts that you can recycle into something else. You’re trained in Crafting and either Engineering or Mining lore, and you get the Crafter’s Appraisal feat. So. Marry that back up to the Humble Fellowship. Pots and pans and parts, experiments with interchangeable pieces and assembly lines. And marry it also to … blood. And trash. And the Wellspring.

The Bloodmarked are the warrior fellowship. They guide national principles. They fight great causes. They’re born of survivors, yes, but their reach is vast. Electoral voting in the Mbe’ke system is weighted according to how many warriors a fellowship can bring to bear in times of war. So the Bloodmarked, as a fully warrior organisation, are powerful.

What happens to the survivors who aren’t?

Say you’re a humble dwarf, from a guild of pot makers, and you’re scrounging cast-offs for useable parts, and you find … a body. A body nobody cares about. Blood in the Wellspring, that’s only an issue because it pollutes the waters. Suppose some of those bodies are people you care about. People in the cracks, dependents on the edges of fellowships, that people do care about, but that don’t exactly have a lot of political weight behind them.

We’re not going to go for a warrior, here. We’re going to go for an investigator.

And there is … Tiny detail. Interesting detail. Mbe’ke society mostly follows the dwarven pantheon, though also, because of the cloud dragons, Gozreh of the wind and waves, and Uvuko, a draconic god. Among the dwarven pantheon, they favour Torag, obviously, and Grundinnar the Peacemaker, less typically, because the Mbe’ke are a mercantile, trading nation, and they have been powerfully allied with the cloud dragons for millennia, which they’re inclined to thank the Peacemaker for. Recently, with the Corsair Wars, the more hotblooded Angradd the Forge God is also gaining favour. But.

There is a lawful neutral dwarven deity called Dranngvit, the Debt Minder. She is considered a sour, acrimonious goddess of last resort, as she was betrothed to Torag once, only to be set aside when he fell in love with and chose Folgrit instead. Humiliated and embittered, she left Forgeheart, the heavenly realm of the dwarven pantheon, and went into self-imposed exile. She is a bitter, outcast goddess, and the goddess of debts, pursuit and vengeance. She asks retribution for contracts broken and debts unpaid. BUT. She is a lawful neutral goddess. She seeks the repayment of just debts, and appropriate vengeance against transgressions. It is anathema to her to force someone into a debt you know they can’t pay. She’s not the goddess of loan sharks, she just … would like agreements to be kept, and justice done if they are not.

So if you’re an investigator, in a society structured around fellowships that are supposed to support and take care of their members, and you have evidence, bodies, that say they don’t always do that. That people slip through the cracks. The promises are not always kept to those who don’t have force of arms to back them up. Maybe you would start to feel like the Debt Minder has some wisdom to offer?

I feel like an investigator. A junk collector, a dwarf of the Humble Fellowship of pot and pan makers. Who has found … blood in the waters. Bodies, here or there, among the junk, that nobody, or nobody with power, cares about. They’re not symptoms of a grand cause. They’re not soldiers in a war against piracy. They’re just bodies. People in the cracks. But someone should care about them. That’s what fellowships are supposed to be for. There were promises made. Maybe someone should try and make sure that promises are kept. Or that justice is done when they are not.

At the very least, someone should learn a name and throw a stone into the Wellspring for those who have no one else.

And. We could play this dwarf in Cloudspire, if the campaign is happy to do that. But we can also play them outside of it. Because, well, when you start finding bodies people don’t want found, and poking debts people don’t want to pay, sometimes you wind up having to leave to avoid becoming a body yourself. Not forever. You won’t let it be forever, won’t leave that debt unpaid, but no debts are paid by the dead. So. Survival first, and justice later. Dranngvit is a goddess in exile. If we have to, we can emulate her there, too. And thus we’re out and about in the world, in the wilds. Thus we’re asking our fellow adventurers to, in the event that we can’t, travel back to Cloudspire in our name, and throw a stone into the Wellspring to guide our soul home the only way left to it.

So. An Mbe’ke dwarf. A junk collector dwarven investigator from the Humble Fellowship of pot makers in the Sky Citadel of Cloudspire. A attempted champion, in their own small ways, of the unpaid debts and the forgotten dead.

I’m not sure what real world cultures, if any, the Mwangi and Mbe’ke naming conventions are drawing from, but there’s a Yoruba name, Ekundayo, that Behind the Name tells me means ‘tears become joy’, and I think … I think that would fit gently with this dwarf? Maybe she was named because her father never came home after conceiving her. Maybe he was a casualty of the Corsair Wars that the Bloodmarked care so much about. Maybe she could have been a Bloodmarked from the start, if she’d wanted to be. But she was named because she brought joy, even amidst grief, and that’s what she wants to be about. Or wanted. Pots and pans. Simple things, that bring simple comforts and simple joys. But, well, debts still need to be paid.

But, hopefully. Somewhere down the line. Maybe tears will still become joy. That’s … that’s a promise to work towards.

Ekundayo, a Cloudspire Mbe’ke Investigator. Heh.

I do really enjoy having a lot of crunchy setting details to build a character from.

#pathfinder#pf2e#character concepts#dwarves#investigators#mwangi expanse#mbe'ke#a little bit noir PI#also a little bit communist?#that wasn't entirely intentional#i love having setting details to play with#worldbuilding

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

@vitaeplaysda here 🥰 4 - 17 - 27 for the Rook questionaire!

Rook Questionnaire Here!

Abigail Ingellvar

4: If your Rook was a companion, where would they be found?

Her room would be pretty small, filled with books, with a fireplace, a writing table, and a good comfy chair for her to embroider in. The decor would be simple, with few personal effects. She would be one of the few companions to have an actual bed, albeit a very simple one. If she was a companion her Gift would be a pile of romance serials, and she’d acquire a few elven tapestries, some Nevarran artifacts, a halla statuette, and a small jewelry stand as the story progressed. She’d most often be found hanging out with Manfred, Emmrich, or Neve in their rooms or on one of the balconies, or in the kitchen cooking or making tea.

17: Do they enjoy life as an adventurer?

Abigail had never been out of Nevarra before, and very rarely left the Necropolis. She’s a curious person, so she loves exploring and learning new things, especially about elven culture across Thedas, or different funerary practices. She’s always felt very disconnected from her elven heritage, and enjoys discovering things that make her feel closer to it. She spends a lot of time with the Veil Jumpers, and with elven Shadow Dragons. Her least favorite part is probably the actual fighting. She views battle as a vital part of her duties; something to excel at for the sake of the job and for keeping people safe, but not necessarily as something enjoyable.

27: Answered here

Thanks for the ask!!

#dragon age#da4#dragon age the veilguard#da4 spoilers#spoilers#veilguard spoilers#Abigail Ingellvar#mourn watch#rook ingellvar

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

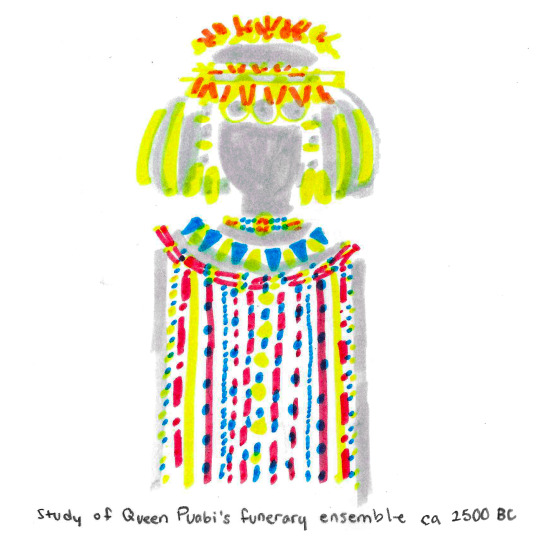

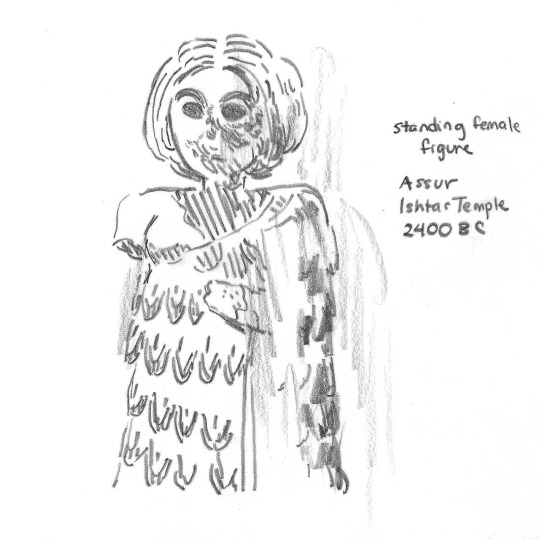

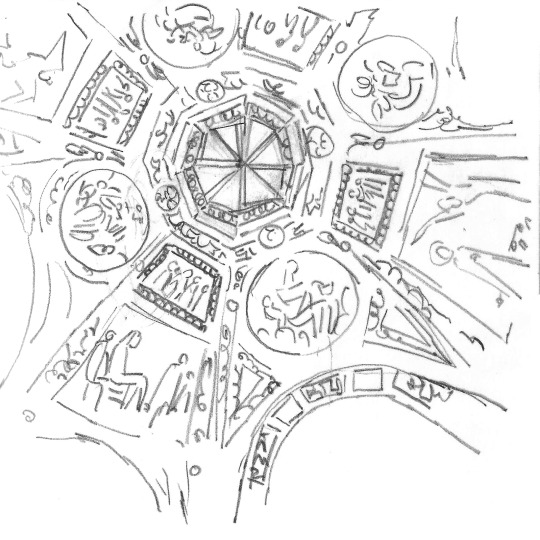

Sketches drawn at the Morgan Library. Image description under cut.

[ID: Six image photo set of sketchbook drawings drawn at the Morgan Library. 1) A gray mannequin bust wearing a golden floral headdress, gold hair coils and a series of necklaces with carnelian, lapis lazuli, and golden beaded chains hanging down the chest, drawn in marker. Written in pencil beneath the drawing, “Study of Queen Puabi’s funerary ensemble ca 2500BC.” 2) A stone carving of a female figure, drawn in yellow and orange marker, and shadows marked in gray. The figure is forward facing with her hands clasped at her abdomen. She wears a long-sleeved dress, hair braided around the top of her head, and bears a smile on her face. Written in pencil beneath the drawing, “Standing Female Figure w/ Clasped Hands - Mesopotamia (2600-2450 BC).” 3) Top half of stone female figure, drawn in pencil. The figure faces front-left three quarters, her right arm and left hand broken off. She bears a neutral expression, voluminous hair tied in a bob, and a woven dress with triangular etchings. The figure’s left side (the viewer’s right) is heavily worn down. Written on the right of the drawing, “Standing female figure Assur Temple 2400BC.” 4) Domed ceiling of the rotunda of the Morgan Library, sketched loosely in pencil. The center of the dome is an octagonal window, divided into eight triangular panes. Branching out from it are a series of repeating scribbled patterns, and mosaic panels featuring cherubs and other classical figures. 5) A casually dressed woman seated front-facing on a bench at the historic library room of the Morgan Library, sketched loosely in pencil. She has straight, medium-length hair, wearing sunglasses resting on her head, a face mask, open cardigan, t shirt, culottes, and closed-toe shoes. Her right hand rests on the side of her face, in the middle of a thought. Behind her is a glass case displaying books, and a wall of bookshelves. Beneath her is a carpeted floor marked by loose scribbles. 6) The fireplace of the Morgan Library historic library room, viewed at a right-facing, three quarter angle. It is drawn in pencil, spanning across one and a half sketchbook pages. The marble fireplace is carved with two Ionian columns to the sides, flanked by two, classical-style, bronze statuettes. Several birch logs fill the firebox. The back of the fireplace is decorated with a relief of a dragon resting atop flames.

End ID]

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

& . we are now open for interactions ! explore volterra, from the glorious architecture to its fascinating history see the this city’s evocative atmosphere. For some this comes from its Etruscan past, visible in the ancient Porta all’Arco and the Etruscan Museum Guarnacci, with its impressive collection of Etruscan funerary urns and the famous statuette “Ombra della Sera“. For others explore the east side of the city that gives it the Medieval feeling of its stone alleyways and closely-packed buildings. The Piazza dei Priori is a magnificent example of a Medieval public space. And to add to its mysterious atmosphere, there’s the Rocca Nuova, a dominating Renaissance prison that’s still in use still today. have fun exploring !

for now your characters have received an invitation to the ball the volturi are throwing that will happen soon ( a post will be made next week ) thus you can all begin your interactions with that small little plop . it's a city event thus all are invited .

tag your starter – sanguis.starter

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Statuette of a hippo, possibly a gift to Khentiamentio, a funerary diety, 3100BC-2649BC, Egypt. Hippos were feared and respected.

271 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kneeling official - Met Museum Collection

Inventory Number: 51.173 New Kingdom, Ramesside, Dynasty 19–20, ca. 1250–1070 B.C. Location Information: Location Unlisted

Description:

The number of examples of nonroyal statuettes in poses and stances typical for use in burials diminishes greatly in the New Kingdom, reflecting a general shift in funerary practices away from the deposition of statuary in tombs and toward placement in temples. This figure is the earliest metal statuette of a nonroyal man that can be ascribed to a shrine or temple provenance because of its ritual worshipping pose. It is datable to the late Nineteenth or Twentieth Dynasty based on the style of the official's hair and garments as well as the style of his face, which shows no influences of the earlier Amarna period. The statuette's open core cavity, without core supports, and its long, irregularly shaped tangs (not visible when the figure is displayed) also support such a date.

#kneeling official#new kingdom#ramesside#dynasty 19#dynasty 20#met museum#51.173#location unlisted#mens clothing#NKRMC

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Standing Statuette of Lady Henutnakhtu

This wooden standing statuette shows the Lady Henutnakhtu of the 18th Dynasty wearing a tight pleated garment and a long beautiful wig. She is holding in her right hand a flower and in her left one a staff, with which to purify the deceased.

The statuette rests on a wooden base with hieroglyphic text giving the offerings and the name of Henutnakhtu. Note that the face, surmounted by a heavy three part wig, is slightly large in proportion to the rest of the figure. The robe has just one sleeve with the left arm held at her side bare. This statue would have served as part of Henutakhtu’s funerary assemblage.

New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, ca. 1550-1292 BC. Height: 22.5 cm. From Saqqara necropolis. Now in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo. JE 6056 Read more

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roman statuette of Harpocrates

ITEM Statuette of Harpocrates MATERIAL Marble CULTURE Roman PERIOD 1st - 2nd Century A.D DIMENSIONS 110 mm x 60 mm x 34 mm CONDITION Good condition PROVENANCE Ex Swiss private collection, acquired between 1970 - 1990 In the Roman period, Harpocrates continued to be a significant deity, albeit with adaptations and reinterpretations influenced by both Roman and Egyptian religious traditions. Harpocrates was originally an ancient Egyptian god associated with silence, secrets, and confidentiality. In the Hellenistic and Roman periods, the cult of Harpocrates spread throughout the Mediterranean, and the god underwent syncretism with various Greek and Roman deities, blending cultural and religious influences. In Roman art and mythology, Harpocrates is often depicted as a young boy with a finger to his lips, symbolizing the gesture of silence. The Romans associated him with the concept of confidentiality and discretion, making him a popular figure in various contexts, including funerary art and domestic worship. The Roman adaptation of Harpocrates integrated elements of the original Egyptian symbolism with the broader Greco-Roman religious landscape, showcasing the fluidity and adaptability of ancient religious beliefs during this period. Devotion to Harpocrates also found a place in mystery cults and esoteric traditions in the Roman Empire. Read the full article

#ancient#ancientart#ancienthistory#artefact#artifact#ancientartifacts#antiquities#antiquity#art#artobject#ancientrome#ancientworld#history#classical#archaeology#roman#marble#statuette#statue#figure#figurine#harpocrates

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

there are a lot of ugly caskets in this world. listen….perhaps i am not an arbiter of funerary trends but if i owned a funeral home i would make the only option a tasteful rectangle made out of maple or poplar. no embroidery or metal statuettes of the pieta or brushed metal or ruffles. handles are on thin ice.

#wicker caskets also look nice#funeral home#indexing our caskets makes me very judgmental#we offer about a thousand and there are like. five that are even acceptable

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Is a Shabti, Anyway? (An Egyptologist Answers Your Burning Questions)

So, I wrote a novel called The Shabti (coming summer 2024!). In case you’re wondering what a shabti is—and why you might want to read a story about one—make yourself comfortable and let me fill you in. This might take a few minutes to explain.

The basics:

A shabti is a type of ancient Egyptian funerary figurine. If you’ve spent any time looking at Egyptian artifacts, you’ve probably seen one of these little guys. They usually* look like tiny mummies, with their legs fused together and their arms crossed over their chests. Sometimes they carry tools, such as hoes, adzes, and baskets. They can be made from a variety of materials, including stone, wood, pottery, faience, or even glass. For a typical example, check out this guy--a limestone shabti dating to the 18th Dynasty (ca. 1550-1295 BCE) that now resides in the Metropolitan Museum of Art:

There are many similar types of figurines (more on that below), but the shabti was specific to funerary contexts and served a particular purpose. It was intended to act as a stand-in for its owner that would step in if the deceased was called upon to do various types of labor in the afterlife.

While a lot of shabtis were inscribed only with the name and title(s) of their owners, others bore a spell explaining their function. This spell is usually identified by modern Egyptologists as Chapter 6 of the Book of the Dead, but it actually goes back to the earlier Coffin Texts of the First Intermediate Period and Middle Kingdom.

There are several variants of the Shabti Spell, and an even greater number of translations. But the gist is always the same: if the owner should be called upon to do various types of corvée labor in the realm of the dead (including things like tilling the fields and ferrying sand around), the shabti would step in to do the dirty work.

“I will do it,” promises the shabti. “Here I am!”

Some Egyptologists contend that in order to count as a true shabti, the figure in question must 1) be from a burial context and 2) be inscribed with at least a partial form of the Shabti Spell. But, like so many concepts in Egyptian religion, the shabti defies easy categorization. Shabtis have a lot in common, for example, with the votive statuettes inscribed with the names of their owners that pilgrims sometimes left as offerings at sacred sites. They may even share an affinity with the wax figurines described in several Egyptian magical texts and literary tales that could be animated and sent to do the bidding of the magicians who created them.

As representations of the dead in the form of Osiris, they could also serve a secondary purpose as a backup home for the Ka, or life essence, of their owner.

--

*There's actually a fair bit of variation in the appearance of shabtis. There was a brief fad for putting them in the “dress of life” during the Ramesside period (ca. 1295-1075 BCE), which means they are dressed in the equivalent of white tie formalwear instead of being bundled up like a mummy. Some of the earlier ones just look like, well, sticks. These might have a square-ish approximation of a face and maybe a blocky unifoot, like some kind of Minecraft mummy. You can see examples of both types, along with the more common mummiform shabti, here.

A brief history of the shabti:

The shabti represents one stage in the long, complex evolution of funerary statuary in ancient Egypt. It is the result of a melding together of several earlier traditions in Egyptian funerary art and religion.

One of the earliest types of statuary from Egyptian tombs is the Ka statue, a formal representation of the deceased person that was housed in the tomb chapel. Some Ka statues depicted single individuals, while others depicted couples or family groups (consisting of spouses, parents and children, or siblings, for example). These statues served as interfaces between the dead person (or people) represented in the statue and the living people who maintained their funerary cult. They were also meant to serve as a sort of backup body, a place where the person’s life-force (Ka) could go to rest and receive offerings.*

The ancient Egyptians liked to feed and entertain their dead. They envisioned an afterlife that was not too different from life-life, where dead people required sustenance and enjoyed the same kinds of luxuries and diversions that they did when they were alive. It also wasn’t without its dangers and inconveniences—hence the need for various forms of magical protection and assistance for the tomb owner.

In the later Old Kingdom, the serdab (“statue chamber”) that housed the Ka statue was also home to an assortment of other figures, commonly called “serving statuettes.” These statues are less formal and more naturalistic than the Ka statues. They show people engaged in various kinds of work, entertainment, and, sometimes, play. Serving statuettes can represent men and women, adults and children, and they depict a range of activities from slaughtering animals, grinding grain, or brewing beer to playing music, wrestling, and dancing.

These statuettes seem to have been intended as a sort of support staff for the dead. In the event that the supply of offerings from the living dried up, the serving statues were there to act as backup—much like the Ka statue itself served as a replacement home for the soul if anything should happen to the body. These representations of people preparing food and engaging in various other acts of service had the magical potentiality of becoming “real” in the realm of the dead.

Interestingly, not all of these statues represented nameless, generic servants. Some of them were inscribed with the names of the tomb owner’s children or other relatives. Perhaps this was both a way of honoring a deceased family member and a ticket to ride along with the tomb owner’s funerary cult. (Want to read about a couple examples of these named serving statues? Check out the writeups on pages 108-109 of this special exhibit catalog, written by yours truly.)

The serving statuettes were phased out after the end of the Old Kingdom in favor of elaborate wooden tomb models depicting whole tableaux of people at work. These models portray everything from crews manning ships to weavers toiling in textile workshops. Sometimes the tomb owner is depicted as well, carrying out the kinds of duties they would have done in life (such as overseeing cattle counts).

In the Middle Kingdom we also see the development of “estate figures,” an evolution of a type of two-dimensional imagery common in Old Kingdom tomb chapels. These are personified representations of the estates that supported the tomb owner’s funerary cult, and they were intended to keep providing for the soul of the deceased for eternity. They take the form of offering bearers carrying food, drink, and luxury goods for the dead.

But around the same time as these tomb models, another type of funerary statuette appeared on the scene. The earliest proto-shabtis were simple wax or clay figurines which eventually developed into miniature mummies, sometimes complete with wrappings and/or tiny coffins. While the earliest examples usually weren’t inscribed with much more than a name and titles, some of them carried an abbreviated version of the longer Shabti Spell.

By the New Kingdom, the more elaborate tomb models and serving statuettes had fallen out of favor altogether, to be replaced by the more streamlined and standardized shabti figurines.

While larger, more formal statues of the tomb owner were still a standard feature of most tomb chapels, the shabtis also served to combine the functions of the earlier Ka statues and the serving statuettes. The shabti both represented the deceased and served as a replacement or stand-in that was bound to do its owner's bidding; the master and servant combined into a single figure.

Up until the end of the New Kingdom, most burials contained only a handful of shabtis. These earlier examples tended to be individualized and highly variable in their appearance. As time went on, the number increased, and some people were buried with hundreds of mass-produced shabtis—a whole army of tiny henchpeople.

During the later New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Period, overseer shabtis were produced to manage the more generic worker shabtis. These super-shabtis were depicted carrying symbols of authority, such as whips and staves. A wealthy Third Intermediate Period burial might have 365 standard shabtis--one for each day of the year--with 36 overseer shabtis to manage them all. The overseer type eventually fell out of fashion with the return to more classical forms in the Late Period, but the tradition of mass-producing shabtis by the hundreds continued.

Around the same time, the spelling of the word “shabti” changed to reflect their evolving nature. More on that in a minute.

--

*Another weird possible spinoff of the Ka statue and/or precursor to the shabti is the so-called “reserve head,” a type of object that was in vogue very briefly, during the 4th Dynasty. What were these for? Well, like so many things in Egyptology, all we have are educated guesses. But the most popular theory is that they were literally spare heads. You know, in case something happened to the dead person’s real one.

What does the word “shabti” mean?

Hahaha! Wouldn’t we all like to know.

Okay, so in the early Third Intermediate Period, the spelling of the word changed from SAbty (shabti) to wSbty (ushebti). The explanation of the latter spelling is clear. It’s a backformation based on a folk etymology from the word “wesheb,” which means “to answer.” The ushebti is an “answerer,” an entity that responds when called upon to do work. This change may reflect a loss of the shabti’s earlier status as a representation of the deceased as well as a stand-in. The sole purpose of the ushebti was to do labor on behalf of its owner. These figures were simple worker-drones for the dead.

But what about the earlier form of the word? Well, speculations run the gamut from shabti being a form of the word SAb (meaning “food” or “meal”) to a Semitic loanword meaning “stick” or even a form of SAwAb (meaning “persea tree”). There might also be a connection with a word attested in Late Egyptian, Sby (meaning “to replace”). Any one of these meanings could make sense if you squint enough, but we may never know with certainty which one is correct.

What’s the deal with the shabti in your book?

Well, obviously I’m hoping you’ll read it and find out. For now, suffice it to say that it’s a particularly troublesome shabti. So troublesome, in fact, that the mild-mannered professor who curates the museum in which it now resides is starting to suspect that its original owner isn’t quite finished with it yet . . .

2 notes

·

View notes