#fun fact I work professionally as a graphic designer and this is a good representation of the kind of work I typically do

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

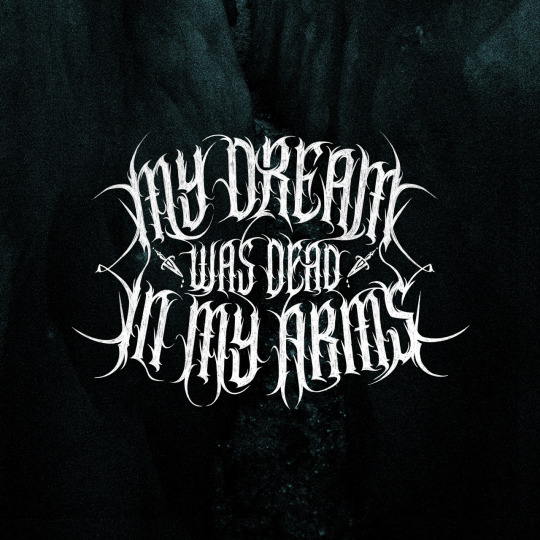

Fool's Fate but make it Death Metal

Inspired by yet another unhinged RotE discord convo from a while back.

#fool's fate goes hard#fitz would have been a metal head for sure#realm of the elderlings#rote#fool's fate#the tawny man trilogy#death metal typography#what is this even#fanart? kind of?#fan typography??#custom typography#fun fact I work professionally as a graphic designer and this is a good representation of the kind of work I typically do#most of my clients tend to want a more grunge/zine style aesthetic and I'm 100% here for it#but it's a lot different from my very cute and wholesome comic style#some rink lore for ya I guess lolol

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

GDMM106 Developing Graphic Concepts

This is my research report into book production methods, I will be exploring different binding techniques and materials used as well as investigating different print processes.

A brief history of books!

Books communicate an idea, Document a process or record historic moments throughout time, they have been used as an instrumental recording practice across all forms of each great civilisation known too man, different types of cultures such as religion, science and all manner of making practices have been recorded to quench the thirst for information!

The first materials for written documentation were beech, Bark and Bamboo it was not until the Mesopotamian culture used cuneiform tablets that were made from clay.

In Ancient Egypt they recorded written documentation on scrolls that were made from the Paryus Plant, these scrolls could be anything up too 14-52 feet in length and were clunky as you needed to hands too read them, also the longevity of these scrolls would crack and disintegrate.

The Romans created the Codex, This was the first recognisable book form as this had covers made from wood which protected the precious pages inside.

Pages made from animal skin (Vellum) was durable and lasted a long time, the codex was the first to contain an index of contents.

The first form of print was invented by the Chinese, all books since then had been hand written this was a laborious task which took time.

The Diamond Sita was a book that was printed using individual letters and shapes made out clay blocks this was revolutionary as you could save time by re arranging the letters, However the clay moulds began too crumble over time.

Koreans used bronze moulds which was a sturdier material

The Gutenberg Printing Press which was invented by Johannes Gutenberg in 1460 was a methodical printing press which gave mass communication to everyone, Before books had been an expensive luxury only for the rich but with the printing press literacy began to flourish and reference books like dictionaries became popular.

Pamphlets became popular and allowed people too share and talk about new ideas these also paved the way for newspapers and magazines!

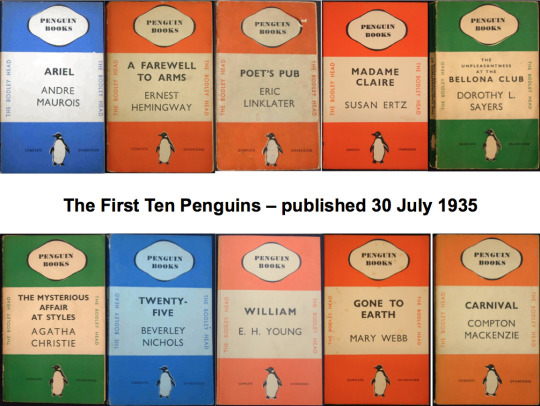

Modern Printing opened the world up even more too affordable books as some books were still sewn together in binderies which the revolution of glued binding and with Penguin publishing selling there first Paperback in the 1930′s this was dispatched and sold in busy transport hubs for the same price as a pack of ciggarettes!

The Evolution Of Book Cover Design

Medieval manuscripts are one of the first book cover designs we see, These manuscripts are usually heavily decorated with Gold and Silver usually encrusted with jewels.

Front cover, Lindau Gospels, c. 875.

Back cover, Lindau Gospels, c. late eighth century.

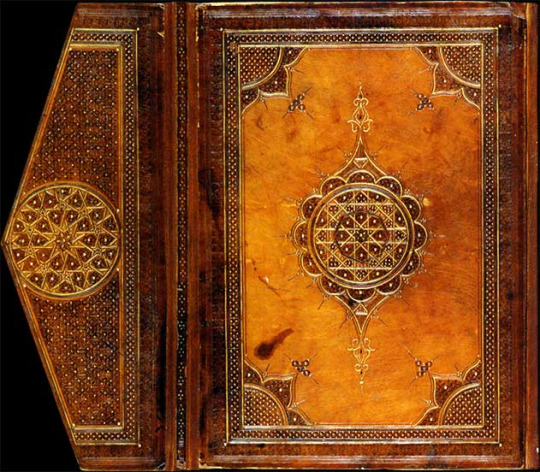

The Mamluk binding, commissioned by the Amir, Aytmish Al-Bajasi in Cairo in the eighth century, Front Cover on the Quran with intricate Geometric shapes embossed with gold

For hundreds of years these covers served as protection for the pages and are an expensive mark of respect for the cultural authority they represent.

It was not until the 1820′s that book cover design was seen as something to represent the text of the book, this was made easier by the mechanical revolution of steam powered printing which made books more affordable thus being able too experiment with applying techniques of colour Lithography and half tone illustration processes.

19th century Poster-Artists started too infiltrate book design as did the professional practice of graphic design, Book covers became something more than just protection for pages it was seen as a necessary advertisement for communicating the idea of the book.

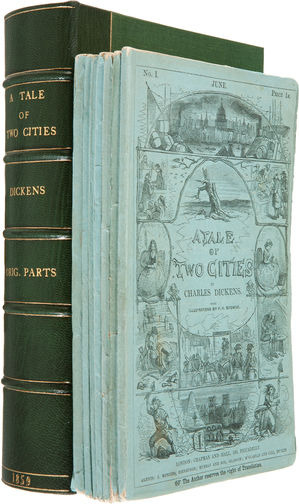

This is seen in Charles Dickens monthly editions of literature that were printed and distributed in a serialised form of twenty monthly issues, These little notable green sleeved front covers with hand drawn illustrations where made available so that the middle class could acquire these editions and spread the cost instead of purchasing the full edition.

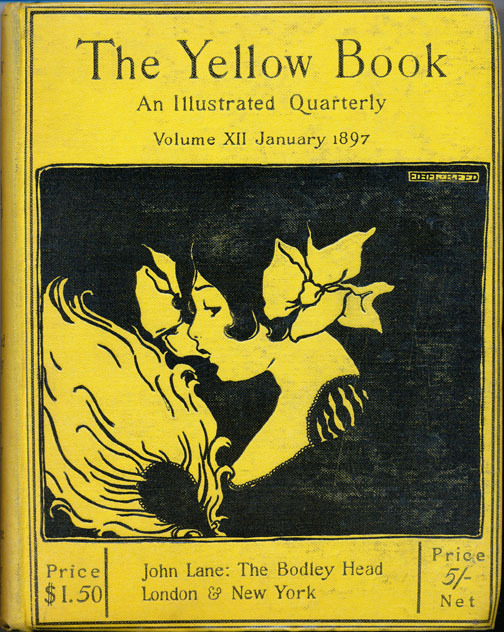

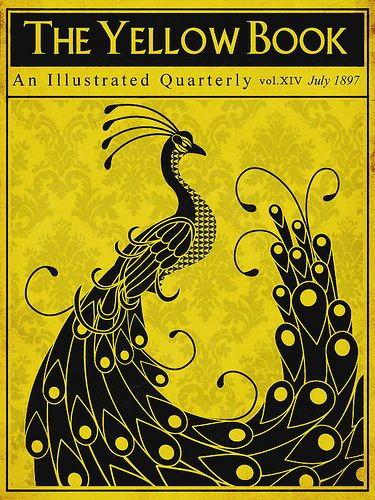

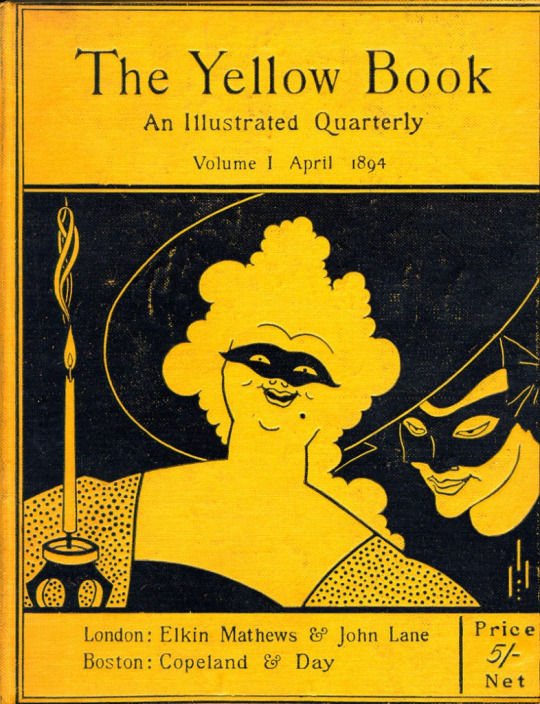

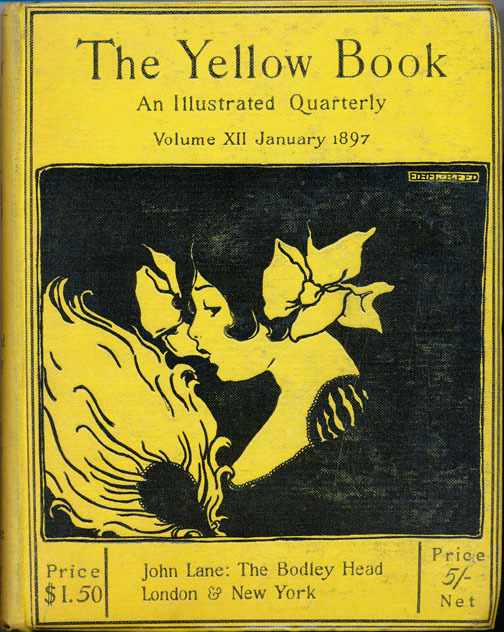

Another series of books that started too influence the necessity of book cover design was the ‘The Yellow Book’ which was published in April 1894, The striking cover illustrated by Aubrey Beardsley featured some of his recognisable and distinctive style of form and flattened perspective this coupled with his bold use of black space with yellow was a striking and noticeable.

Sadly for the time these covers were not received well as The Times commented 'repulsiveness and insolence' of the first cover and went on to describe it as 'a combination of English rowdyism and French lubricity'

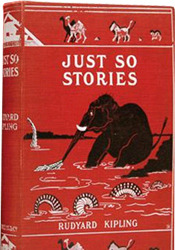

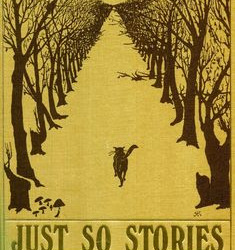

in 1902 book covers made there way into children's fiction as seen in Mr Kipling's Just So Stories

In 1911 There became a new commercial turn! Publishers became convinced that the jacket was every bit as important too advertise the book, as one publisher said "convinced that a book, like a woman, is none the worse, but rather the better, for having a good dressmaker”

This was the beginning of commercial illustrations being used too explain the contents of the book, In the 1920′s advertising and packaging design became prominent due too the economic boom in the US and with the rise of new artists this made the commercial art possible.

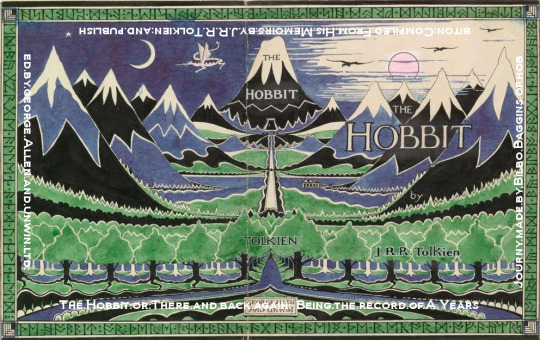

Publishers started taking the reigns on cover design with little or no reference too the author, In some rare cases illustrations from Authors did make there way onto the market authors like J.R.R Tolkien The Hobbit was a stylised illustration with runic type suited this other worldly book that Tolkien designed himself.

This simple illustration perfectly reflects the immense journey that is ahead with all the while drawing your attention too ‘The Lonely Mountain’ in the middle

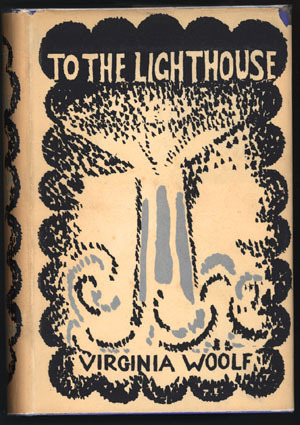

this is also seen in other cases in ‘To the Lighthouse’ by Virginia Woolf this cover was designed by her sister Vanessa Bell

This Archetypal Column of light with the waves crashing around it is a window into the book playing on the different perspectives of the themes

The next big thing was the colour coded book designs that penguin issued in 1935, These paperback books where an instant hit as Penguin had established simple system for different genres orange for fiction blue for biography green for crime, these little books opened up literature for people of all classes and were sold at many busy transport links around the country.

By today's standards these cover designs look very austere and quite boring simple typography with soft engravings clearly show the attitude of irrelevance too illustrative book design, This could also be due too the fact that British audiences were not used too such invasive advertising

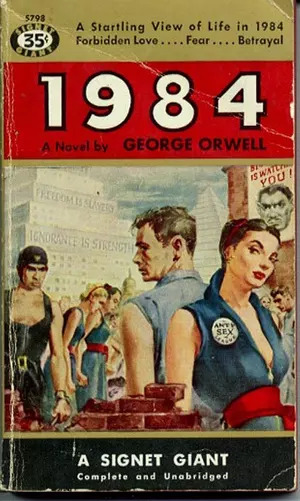

1984 by George Orwell (American edition)

Here we see a prime example of 1984 by George Orwell this was the American version that was published, We see the cover has been over sexualised and is mis leading the representation of the book.

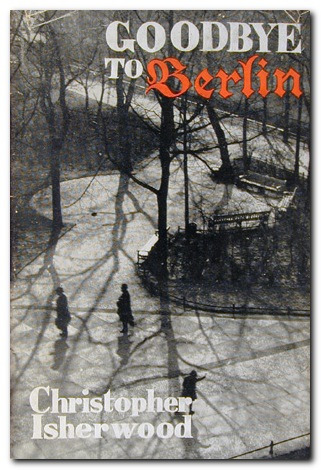

In 1939 Christopher Isherwoods - Goodbye To Berlin featured a Photograph of a Berlin park from above, This was encapsulating the narrative ‘I am a Camera’

By the 1960′s Photography was a widespread practice in cover design, Alan Aldridge cover design was always tasteful photos of womens torso’s disapearing into shadow was always sexy but restrained.

his works generally were always used for exploring the narratives for sexual passions.

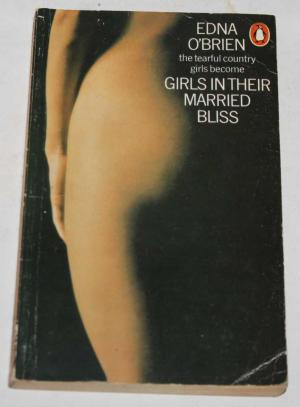

The cover for ‘Girls in their married bliss’ Published by Hogarth Press

Alan Aldridge decided to poke fun at Penguins distaste for illustrative and also photographic design by placing the penguin logo too the right as if showing embarrassment of the nubile young woman.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

9.4.4: Week 4 Mastery Journal Process and Reflection -

During my four weeks of Multi-Platform Delivery I was tasked with planning and then developing various types of media. I learned to create professional-quality deliverables from the research and exploration I conducted in my previous courses. I designed for a variety of platforms with the goal of developing a unified multi-media campaign for my developed Myrtle St. identity brand. I then refined those assets through critique and further development in preparation for its presentation.

Material & Concepts Overview:

This month was all about planning and developing media assets for various platforms, and to bring the production of my three-month Myrtle St. community branding project to a close. In week one I reviewed Logo Design Love and David Airey’s, 7 Elements of Iconic Design as well as read How To Proceed With Sketching Of Logo Design, by Henna Ray, and re-reviewed Logo Design: Illustrating Logo Marks, with Von Glitschka to develop, refine, and finalize a logo for Myrtle St.’s brand.

In week two, with the finalized logo completed it was time to delve into media asset planning and production. I started by reading How to Optimize Your Workflow as Freelance Graphic Designer, by 99designs and learned about Photoshop and In-Design mock-ups and plug-ins that can work to speed up my workflows and save me tons of time not having to make the templates from scratch. In particular, I had a lot of fun experimenting with this die-cut sticker mockup, by Axel Valdez, 2017. The smart object adjusts the padding of the stroke around the sticker to give the asset a die-cut look. After playing with 6 or 7 different iterations of Myrtle St.’s sticker, I realized that not only was I having too much fun and needed to refocus and get back on track to maintain my production timeline with my other assets, but also that since the template provided me with a technical edge, I had more freedom to experiment with other templates and design assets that would bolster the Myrtle St. brand. The sky’s the limit but I don’t have to stop there. I also, explored Olympics: User Experience and Design, by Nick Haley and examined Designing a New Playground Brand, by Playground Inc. for added guidance and inspiration.

In week three, I dove even deeper into asset production and finished up asset development. This free-form process allowed me to not only develop print collateral and digital assets for brand roll-out, but also allowed me to further experiment with and explore my brand’s design elements and how I can apply them to effectively communicate the voice of my brand to Myrtle St.’s intended target demographic while bolstering the graphic and dynamic nature of the brand and it’s elements.

In week four, it was time to conduct a postmortem or rather, a retrospective of my brand and to bring the production of my three-month Myrtle St. community branding project to a close. First, I read Running a Successful Post-Mortem, by Will Fanguy, watched Running a Design Business: Creative Briefs, Chapter 7: Evaluating Creative Briefs, with Terry Lee Stone to dissect and critically examine the strengths and weakness of Myrtle St.’s brand identity, what could stand to be improved and refined vs. what was working, and further more why those facets did or didn’t work. From there, I read How to Create a Brand Style Guide, by Shirley Chan and watched Learning Graphic Design: Layouts, with John McWade and learned the 6 essential elements that should be included in every brand style guide, and the 4 things I should do for every layout, “One, keep things simple. Two, have a focal point. Three, make bold moves. And four, put white space to work” (McWade 2016, Learning Graphic Design: Layouts).

I then got to work developing the beginnings of a brand guide for Myrtle St. that will be a critical user manual for maintaining the brand, and representing it’s various elements, from the logo to the treatment of brand images appropriately.

Degree Learning Outcomes:

Connecting/Synthesizing/Transforming - During the beginning of the course, as I was walking to work and contemplating Myrtle St.’s brand and it’s burgeoning logo, I saw a bike path with a painted representation of a bike with arrows and it dawned on me that arrows convey movement, guide direction, and can be associated with cycling and the bike paths of the area. When, I returned home I began to conduct research into way-finding and community signage. As I toyed more and more with the idea of implementing arrows into Myrtle St.’s branding, the idea of a diamond-shaped two-way street sign came to mind. At first it was merely meant to encapsulate movement through the use of another arrow, but then came considerations of how cyclists, pedestrians, skateboarders, and more all pass each other just like traffic would, side by side. By focusing on the arrows not only to promote and indicate movement, but also how the community’s target demographic navigates and gets around, bolsters the strength and purpose of the arrows in not only the logo, but also the use of arrows as two different brand patterns, as a key component in community way-finding signage, and as transition animations for the developed motion graphic, logo, and future digital media. By stumbling across that bike path, I examined the purpose and meaning of arrows in navigation and our perception of the shape itself, how it implies motion, movement, direction. I then synthesized those meanings and transformed the simple shape of an arrow into a key, critical element of Myrtle St.’s brand. Airey (2015) states, “Begin by focusing on a design that is recognizable—so recognizable, in fact, that just its shape or outline gives it away” (Airey 2015). While he is referring to keeping things simple for logo design, the same rule can be applied to larger facets of design. By choosing to incorporate arrows, a recognizable and simple shape I bolstered the graphic nature and visual voice of the Myrtle St. brand.

Problem Solving - Myrtle St.’s design problem was, that the lack of jobs, services, or attractions left the community of Myrtle St. asking what’s here for me? The perception of the area was that it featured poor infrastructure, roads riddled with potholes, worn down neighborhoods and houses, and a lack of an abundance of jobs, services, or attractions. Myrtle St. was perceived as a worn down area with nothing to offer. The developed Myrtle St. brand challenges the community to take the best of what the area offers. Myrtle St. boasts scenic views of mountains and the Clark Fork river, explorations of the historic buildings of the area, such as the Knowles building, and a plethora of outdoor sporting activities and opportunities for individual wellness through exercise. The challenge presented to the community of Myrtle St. is to embrace those facets as a means to interconnect the community and instill a purpose within the community. The over-arching brand tackles each misconception of the area, and offers something for the target demographic looking to bike with friends to Bernice’s Bakery for a fresh baked good and huckleberry tea, for the friends looking to Frisbee golf in the park, for the runner preparing for a marathon along the river trail, as a gathering spot for activists to commune, and more. While infrastructure and the job market are bigger overarching problems for Missoula as a whole to tackle, the wellness and well-being of its citizens is a community challenge. Myrtle St. solves these problems by changing the perception of the area as a fun, cheerful, and friendly community that the target demographic would want to adventure in and explore.

Innovative Thinking - The Myrtle St. brand is unique and innovative in that the final overall design is unexpected. The brand began by considering the target demographic’s question of, “What’s here for me?” and answered with an outdoor hub for cyclists, pedestrians, and more to engage in wellness through exercise, experiencing the outdoors, and to interconnect the community through shared outdoor and sporting activities, as well as invite everyone to join in on the fun, adventure, and pursuit of wellness. The use of the tetradic, or rather double-complimentary color palette avoids self-referential design, and while at times can be tricky to balance, allows varying opacities of the color palette to work together to convey a message and allows one specific color to be the main carrier of the intended message. The arrows as symbols, and as a shape for the brand’s design elements and logos convey motion, sports, and is reminiscent of arrow street signs or markings along bike paths that community members would see. The excitement and cheerful nature of the brand is a surprise to the target demographic that initially only considered the area’s pot-holes, poor infrastructure, and lack of jobs as all that the Myrtle St. area had to offer. Now, the unexpected design offers them a solution to embrace, opportunities to engage in, and invites the target demographic to take part in the community that was previously perceived as lack luster.

Acquiring Competencies - Where to begin? I learned more about media asset planning,. production, and delivery, as well as how to effectively examine and conduct a retrospective on a completed brand, and the key elements of brand guide, along with developing a deeper understanding of layout. I also learned how to work more efficiently and improve my work flows with Photoshop mock-up templates. In particular, I enjoyed experimenting with the die-cut sticker mockup, by Axel Valdez, 2017. Since the smart object adjusts the padding of the stroke around the sticker to give the asset a die-cut look., I began making more and more iterations of stickers for the Myrtls St. brand. Each became more bold, more out of the box, more fun. Each iteration brought me closer and closer to my finalized sticker asset.

First Iteration:

Second Iteration:

Third Iteration:

Final Iteration & Chosen Sticker Asset:

I remember after the second iteration remarking, “Oh that’s so cool!”. A huge part of why this simple and seemingly small process became so critical for not only the rest of Myrtle St.’s assets, but also its brand guide was that I had fun. I enjoyed this immensely. Seeing the padding of the stroke adjust to the shape of the smart object fueled my creativity, and was a critical and friendly reminder that while my assets and designs, of course need to align with the voice and vision previously developed for the brand, but a key characteristic of the brand’s voice is fun. So having fun with the design process only aided the finalized assets in communicating that critical facet of the brand.

Reflection:

Week 1: Logo Concept Development: In week one I explored logo concepts, refined my concepts through critique and further research, and then finalized a single logo that works to communicate Myrtle St.’s essential core attributes and also aligns with David Airey’s 2014, 7 Elements of Iconic Design.

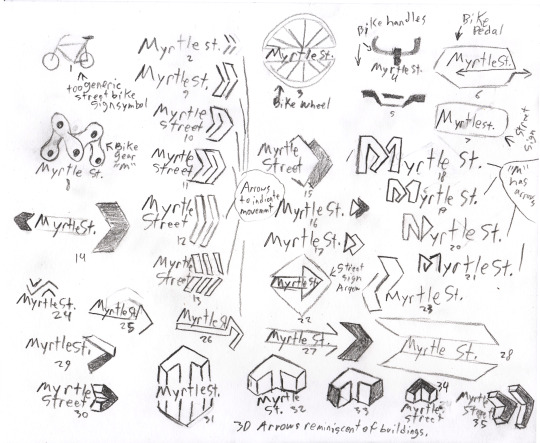

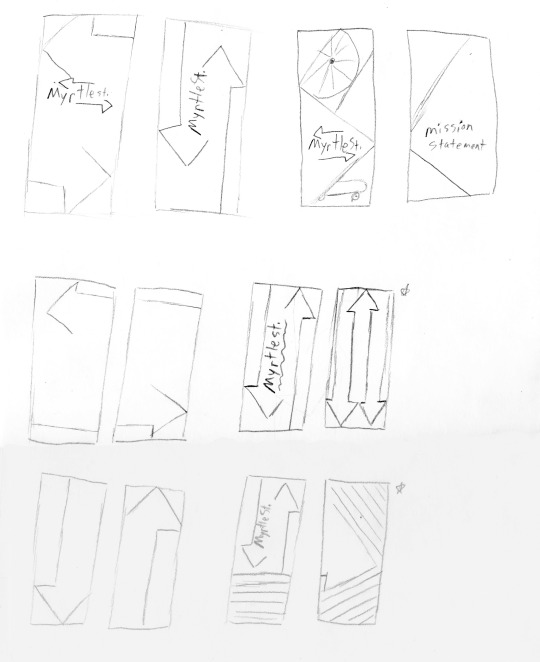

Initial Logo Sketches:

Initial Logo Sketches Rationale:

In what ways did your research inform this ideation process?

In considering the Myrtle St. brand and the pursuit of outdoor activities and sports as an opportunity for wellness and a chance to interconnect the community, the logo needs to encapsulate the idea of movement or motion. Often times on bike paths you can see the painted representation of a bike and arrows to indicate the path. It was with that image in mind that I began to ideate and sketch. Airey (2015) advises, “Adopting a minimalist approach enables your logo to be used across a wide range of media, such as on business cards, billboards, pin badges, or even a website favicon” (Airey 2015, p.22). By choosing to keep the logos simple the concepts become more versatile and adaptable for different media and different applications.

In what ways can you be confident that the selected logos will effectively communicate the brand identity?

The initial concepts work to encapsulate the adventurous characteristic of the brand in that with the arrows incorporated, the target audience will be encouraged to go out and explore all that the Myrtle St. area has to offer. Ray (2018) asserts, “When sketching, you must be aware of the main branding elements” (Key Branding Elements section ¶ 1). In considering the target demographic’s enjoyment and preference to bike places, the arrow approach will connect not only the movement and energy of the brand, but also the target audience’s desire to cycle over to Myrtle St for fun.

In what ways are your solutions unique, or innovative, by comparison to existing logos found through research that represent near and competing locations?

There are many, and I mean many a bike logo, bike wheel logo, bike gear logo, bike chain logo, and admittedly some of the first initial sketches feature these clichés. An “M” made of bike gears, Myrtle St. text placed in the center of a bike wheel, a minimalist rendition of a bike, but Myrtle St. is not about bikes or cycling. The brand strives to interconnect our all-inclusive community in the pursuit of wellness and fun through the transformative and healing power of the outdoors. Ray (2018) offers, “Know the brand’s mission as well” (Know Your Bran section ¶ 3). In considering Myrtle St.’s brand mission statement the arrow concepts work to incorporate the pursuit of wellness and the desire to be adventurous, seek wellness, and have fun.

What difficulties did you encounter within this concept sketching process?

As designers we are not here to re-invent the wheel. In the first handful of sketches there are many cliché and frequently seen cycling related depictions of bikes and all things bike related. I had to refresh my knowledge of my previously conducted research and remind myself that while the Myrtle St. area boasts being adjacent to the Clark Fork river bike trail the brand is not about bikes or biking. The brand is not solely focused on the river trail, but the Myrtle St. area as a whole and all that it offers the target demographic. In considering this, I was able to re-visit Airey’s Seven Elements of Iconic Design and work to further sketch concepts that are simple, relevant, and focused on one thing. Airey (2015) believes, “It’s up to you to tread new paths in your attempts to create designs that are a cut above the rest” (Airey 2015, ch. 3).

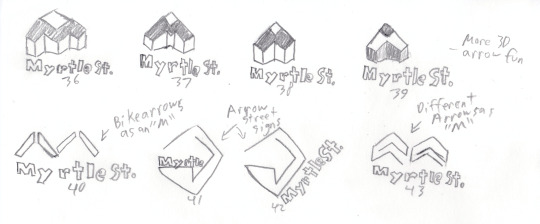

Logo Refinement Sketches:

Logo Refinements & Rationale:

Logo Refinement of #11:

Number 11 was selected for its simplicity, distinction, and focus on one thing. The proposed revision still incorporates arrows that indicate the promotion of movement and outdoor activity as a source for fun, adventure, and the pursuit of individual wellness. However, the proposed revision now incorporates relevance and tradition in that by connecting these arrows side by side and placing them above the text the target demographic can now be reminded of the mountains that can be seen in the distance as they explore Myrtle St. and the roofs of houses in the area. Myrtle St. with all of its natural, historical, and architectural offerings needs a logo that encapsulates the values of the brand, the unity of an interconnected community and a welcoming of the target demographic to the all-inclusive Myrtle St. community. Airey (2015) states, “Begin by focusing on a design that is recognizable—so recognizable, in fact, that just its shape or outline gives it away” (Airey 2015). By choosing to connect two upward pointing arrows and placing them above the Myrtle St. text the target audience can be reminded of the distinct scenic view of mountains that can be seen in the area as well as symbolizing the interconnected and all-inclusive community that the Myrtle St. brand strives for.

Logo Refinement of #34:

Number 34 was chosen for its relevance, focus on one thing, and its memorability. Like number eleven, this concept features two upward facing arrows, but are comprised of strong lines giving this approach an architectural feel to symbolize the historical buildings that can be found in the area and how the target demographic bikes, walks, or drives around or between these historic locales to experience the area. Once again, the arrows symbolize the promotion of movement and activity, but also incorporates relevance in that bike paths that can be found in the area features a painted street icon of a bike with two arrows over it. This approach is memorable in the unique 3-D approach and bold arrows. Airey (2015) asserts, “Quite often, one quick glance is all the time you get to make an impression. You want your viewers’ experience to be such that what you’ve designed is remembered the instant they see it the next time” (Airey 2015). It is with this in mind that the proposed refinements were designed to look like two adjacent pieces of architecture. The target demographic will be able to explore the historical buildings, such as the Knowles building by going to the Myrtle St. area and experiencing it first-hand.

Logo Refinement of #42:

Logo number 42 has undergone the most ideation and revision out of all the proposed concepts. Number 42 was initially inspired by a diamond-shaped arrow street sign. At first it was merely meant to encapsulate movement through the use of another arrow, but then the thought of two-way traffic signs came to mind. Cyclists, pedestrians, skateboarders all pass each other just like traffic would, side by side. That’s when the revisions for this logo began to change and transform. Number 42 was chosen for its incorporation of tradition, relevance, and simplicity, however it does abide by Airey’s (2015) other elements of iconic design in that number 42 is distinct in its recognizable design, memorable in its distinction, focuses on one thing, and if the central text were removed it could work small as an icon or watermark on brand images, and more, and would also be highly scale-able to accommodate larger media such as a billboard. Airey (2015) claims, “Incorporate just one feature to help your designs stand out. That’s it. Just one. Not two, three, or four” (Airey 2015). By choosing to focus on the arrows not only to promote and indicate movement, but also how the community demographic navigates and gets around bolsters the use of arrows in this approach and allows number 42 to stand out.

Chosen Logo:

Final Logo Production Rationale:

In considering the Myrtle St. brand and the pursuit of outdoor activities and sports as an opportunity for wellness and a chance to interconnect the community, the logo needs to encapsulate the idea of movement or motion. Often times on bike paths you can see the painted representation of a bike and arrows to indicate the path. It was with that image in mind that I developed the final iteration of the logo. The Myrtle St. brand strives to interconnect our all-inclusive community in the pursuit of wellness and fun through the transformative and healing power of the outdoors. Ray (2018) offers, “Know the brand’s mission” (Ray 2018). In considering Myrtle St.’s brand mission statement the arrow concepts work to incorporate the pursuit of wellness and the desire to be adventurous, seek wellness, and have fun.

Week 2 & 3: Media Asset Production: In week two it was time to produce roll-out media assets that communicates Myrtle St.’s new brand identity. First, I had to develop a media production plan in order to bolster my time-management and strengthen the turn-around time for each asset.

Media Asset Production Plan:

Draft Asset Delivery:

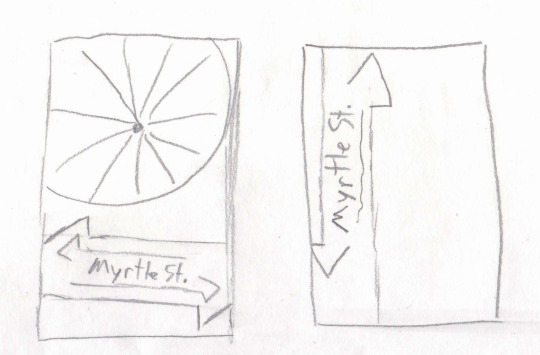

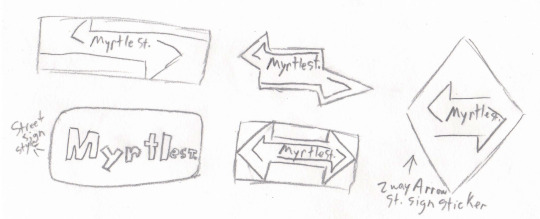

Signage:

The proposed sketches will feature the Myrtle St. logo with appropriate brand imagery and can be placed in main entrances to the community, such as on the Clark Fork River trail or by the historic Knowles building. The proposed signage will provide community information such as way-finding, facts, or the brand’s mission statement. Forsite (2018) asserts, “Like a business or nonprofit organization, your community has a brand, which includes its culture, landscape design, colors scheme, and any other element that make it unique” (Brand Reinforcement section). The strategic purpose of this signage allows visitors of the community to learn more about the Myrtle St. community, what it has to offer, and where they can go to explore the historic Knowles building for example. Visually, this asset will tie into the other proposed asset pieces in the use of relevant brand imagery, colors, and utilizing arrows as a pattern.

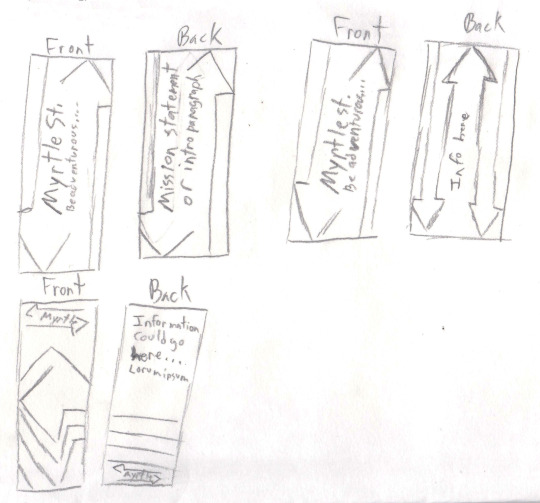

Pole Banner:

The proposed banners not only strengthen the visual presence of the Myrtle St. brand, but could also work to strategically direct new community members and visitors to key features and landmarks of the area. Forsite (2018) argues, “Way-finding signage will help visitors and mail/package couriers find homes and points of interest in any community more easily. Research shows that the average person drives for an additional 250 to 280 miles per year from being lost” (Easier to Find section). Despite the advent of Google maps and other smartphone navigation apps, apps do not always account for potential detours caused by real-world occurrences such as construction, which is a reality the target demographic of the Myrtle St. community face every year. The proposed sketches incorporate the functionality of the arrows but will maintain the fun in functionality by adhering to the brand’s tetradic and cheerful color palette.

Sticker:

The proposed sticker concepts work to incorporate the street sign inspired feel of the Myrtle St. logo and the sporty playfulness of the brand aesthetic. Nicholson (n.d.). believes, “The power of stickers lies in the fact that when displayed they are not perceived as advertising at all. They are personal endorsements, recommendations and badges of support for a message, product or organization” (Anti-Advertising / Personal Endorsements section). The target demographic prefers to shop locally, and considers themselves to be community-centered individuals that often support local causes, groups, charities, etc. They prefer local coffee shops to Starbucks, Shakespeare Books & Co. to Barnes & Noble, and often bike to commute. The effectiveness of keeping the Myrtle St. brand’s logo on the sticker makes the target demographic a walking advertisement for the community for every Myrtle St. sticker they place on their bikes, skateboards, long boards, car bumper, water bottle or laptop.

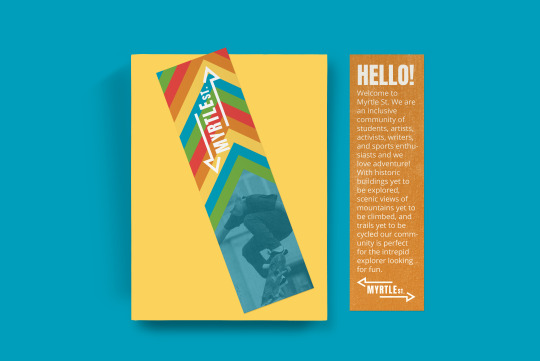

Bookmark:

The target demographic, among other things is comprised of bookworms that enjoy reading for both knowledge and pleasure. During the previously conducted demographic research, it was discovered that the target demographic enjoys biking to local coffee shops to read. It is with this hobby in mind that plans for a bookmark, to be designed and then distributed in local coffee shops to be given away to the target demographic came to mind. The opportunity to engage the target audience and inform them while providing a necessary item for one of their favorite pastimes, reading; is an opportunity to engage the target demographic with an item they will have to look at every time they open their book to read. Nicholson (n.d.) offers, “They are viewed more as a gift than “advertising”. And, like promotional products they are harder to throw away immediately and can engage the recipient” (An Engaging “Gift” section). While he was still referring to the power of stickers as a promotional and marketing tool, for the target demographic in need of a good place holder for their book of the moment, the same sentiment applies.

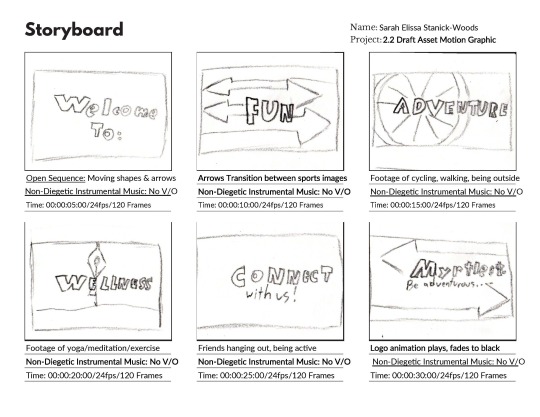

Motion Graphic:

Not unlike the previously conducted Dynamic Vision Board, the proposed motion graphic will work to bring the Myrtle St. brand to life through the power of dynamic media. The proposed motion graphic will encapsulate all that Myrtle St. has to offer in the pursuit of the activities, places, and things that can be found and experienced in Myrtle St. The transition animations of arrows will not only aid in tying together the footage presented, but also incorporate the promotion of movement and the pursuit of individual wellness through exercise and motion. The strategic purpose of the proposed motion graphic is to promote the Myrtle St. brand on the target demographic’s most used social media platform, Facebook. Murphy (n.d.) claims, “Humans are storytelling creatures and our brains soak up a good story like a sponge. With motion graphics, you can not only introduce a product, but turn it into a memorable story” (Videos can tell a story section). By engaging the target demographic in social media, the proposed motion graphic can work to tell the story of the community and all it offers.

Week 3: Finalized Media Asset Production: By the end of week three I was tasked with providing complete and presentation-ready assets. After receiving positive feedback from my peers, I went ahead and tackled turning the proposed sketch concepts into vector assets.

Signage:

The finalized signage features the Myrtle St. logo with a map of the area and will be placed in main entrances to the community, such as on the Clark Fork River trail or by the historic Knowles building. The signage features a map of the area for way-finding purposes. Since a critical value of the Myrtle St. is the pursuit of individual wellness through exercise and an added emphasis on motion and sports, the opportunity to provide newcomers to the community, and community members way to find historic landmarks of the area or the river trail for instance not only introduces the brand, but also maintains the friendly characteristic of the brand by providing a map so they can find their way. Forsite (2018) asserts, “Like a business or nonprofit organization, your community has a brand, which includes its culture, landscape design, colors scheme, and any other element that make it unique” (Brand Reinforcement section). The strategic purpose of this signage allows visitors of the community to learn more about the Myrtle St. community, what it has to offer, and where they can go to explore the historic Knowles building for example. Visually, this asset ties into the other proposed asset pieces in the use of relevant imagery of the community, colors, and utilizing arrows as a pattern, and the use of the logo as well.

Pole Banners:

There are two provided options for pole banners. The first option features relevant brand imagery and the Myrtle St. logo on both sides. The second, still features relevant brand imagery and the Myrtle St. logo, however it also provides an example of how the brand’s trademark arrows can be used for way-finding purposes in an effort to strategically direct new community members and visitors to key features and landmarks of the area. Forsite (2018) argues, “Way-finding signage will help visitors and mail/package couriers find homes and points of interest in any community more easily. Research shows that the average person drives for an additional 250 to 280 miles per year from being lost” (Easier to Find section). Despite the advent of Google maps and other smartphone navigation apps, apps do not always account for potential detours caused by real-world occurrences such as construction, which is a reality the target demographic of the Myrtle St. community face every year. The provided options allow for considerations of location when placed. The first option can be placed in areas by landmarks whereas the second option can be placed in key areas to guide the community.

Further Refined Pole Banners:

After further considerations and feedback from Professor Kratz, I revised and re-worked my pole banners to feature smaller Myrtle St. logos on both concepts, for the first banner I continued to experiment with the placement of the brand’s striped arrow pattern, further applied brand imagery that was more relevant to the brand’s values (and more discernible as to what it actually was), and adjusted the color overlay to be the bolder red of the brand instead of the orange overlay I initially used. For the second banner, I kept the concept of the way-finding arrows, but experimented with color and updated the backdrop with the brand’s secondary pattern of multi-color arrows. These changes add dynamism and bolster the boldness and fun audacity of the concepts.

Sticker:

The provided sticker concept works to incorporate the street sign inspired feel of the Myrtle St. logo and the sporty playfulness of the brand aesthetic. Nicholson (n.d.). believes, “The power of stickers lies in the fact that when displayed they are not perceived as advertising at all. They are personal endorsements, recommendations and badges of support for a message, product or organization” (Anti-Advertising / Personal Endorsements section). The target demographic prefers to shop locally, and considers themselves to be community-centered individuals that often support local causes, groups, charities, etc. They prefer local coffee shops to Starbucks, Shakespeare Books & Co. to Barnes & Noble, and often bike to commute. The effectiveness of keeping the Myrtle St. brand’s logo on the sticker makes the target demographic a walking advertisement for the community for every Myrtle St. sticker they place on their bikes, skateboards, long boards, car bumper, water bottle or laptop. The use of the brand’s pattern and color palette maintains cohesion with other brand elements and allows for easy identification of the brand’s tetradic color palette. Additionally, the strategic purpose of the sticker allows the Myrtle St. brand to go adventures with community members which bolsters the adventurous value of the brand.

Bookmark:

The target demographic, among other things is comprised of bookworms that enjoy reading for both knowledge and pleasure. During the previously conducted demographic research, it was discovered that the target demographic enjoys biking to local coffee shops to read. The opportunity to engage the target audience and welcome them to the Myrtle St. brand while providing a necessary item for one of their favorite pastimes, reading; is an opportunity to engage the target demographic with an item they will have to look at every time they open their book to read. Nicholson (n.d.) offers, “They are viewed more as a gift than “advertising”. And, like promotional products they are harder to throw away immediately and can engage the recipient” (An Engaging “Gift” section). While he was still referring to the power of stickers as a promotional and marketing tool, for the target demographic in need of a good place holder for their book of the moment, the same sentiment applies. The strategic purpose of the finalized bookmark is a frequent reminder of the brand to the target demographic. The subtle use of the brand’s concrete texture over the image and the brand imagery of the skateboard wheel maintains the tangible and achievable nature of the brand’s core value of wellness, while the friendly and cheerful tetradic colors, featured in the use of the brand’s arrow pattern is a reminder of the inclusive nature of the brand.

Further Revised Bookmark:

After receiving feedback from Professor Kratz regarding my pole banners, and how a subtle shift of the brand’s striped arrow pattern could provide added dynamism to those assets I further experimented with the placement of the pattern, included more relevant brand imagery on the front, and completely re-worked the back to incorporate the brand’s concrete texture and refine the alignment of the copy.

Motion Graphic:

vimeo

Not unlike the previously conducted Dynamic Vision Board, the motion graphic works to bring the Myrtle St. brand to life through the power of dynamic media. The finalized motion graphic encapsulates all that Myrtle St. has to offer in the pursuit of the activities, places, and things that can be found and experienced in Myrtle St. The transition animations of arrows not only aid in tying together the footage presented, but also incorporate the promotion of movement and the pursuit of individual wellness through exercise and motion. The strategic purpose of the proposed motion graphic is to promote the Myrtle St. brand on the target demographic’s most used social media platform, Facebook. Murphy (n.d.) claims, “Humans are storytelling creatures and our brains soak up a good story like a sponge. With motion graphics, you can not only introduce a product, but turn it into a memorable story” (Videos can tell a story section). By engaging the target demographic in social media, the motion graphic works to tell the story of the community and all it offers. By strategically engaging the target demographic on Facebook via dynamic media, the motion graphic works to push the brand’s values even further.

Motion Graphic Revision Considerations:

Unfortunately, due to this week’s workload I will be unable to revise and refine this graphic further this week. Professor Kratz offered some insightful suggestions on how I might bolster the strength of this asset. 1) Some of the sequences are a little long, and could stand to be shortened. 2) Play with the Ken Burns effect of parallaxing for the arrow animations for the brand values, also experiment further with the text animations for those values maybe they can grow to fill the screen and fade. 3) Let the Myrtle St. logo animation be the bold animation that sits in the final clip and stays.

Week 4: Retrospective & Brand Guide: In week four it was time to bring the production of my three-month community branding project to a close. I reflected on the production of my media assets via a retrospective, produced a brand guide, and presented Myrtle St.’s brand guide online via Issuu. I began with the retrospective by reading, Fanguy��s 2018, Running a Successful Post-Mortem which allowed me to contemplate the following questions regarding actionable changes for Myrtle St.’s brand: 1) What do I absolutely need to do? 2) What can I do about it now? 3) What should I do about it soon? I also reviewed Terry Lee Stone’s 2013, Running a Design Business: Creative Briefs which allowed me to delve further into the analytical process of conduction a postmortem retrospective on Myrtle St.’s brand.

From there I explored Learning Graphic Design: Layouts, with John McWade and read How to Create a Brand Style Guide, by Shirley Chan to enhance my understanding of layout and the 6 essential elements that should be included in every brand style guide.

Brand Guide:

Production Retrospective:

What was the original Problem to be solved by creating new identity branding? Has the purpose of the brand been met in your materials?

The original design problem of the Myrtle St. area was that a lack of jobs, services, or attractions left the community of Myrtle St. asking what’s here for me? The new Myrtle St. identity branding works to solve that problem by showcasing the opportunity to engage in individual wellness through exercise, to explore the historic buildings of the area, and to engage in fun through shared outdoor activities and sports with friends. While the brand overall works to convey the main message of the brand; to be adventurous, seek wellness, and have fun some of the finalized assets fall a little short on conveying the brand’s purpose to the target demographic. Firstly, the signage for the area and secondly the bookmark. The signage, while it is helpful to newcomers of the area to provide way-finding signage (in this case a Google map of the overall area) with a brand color overlay, the brand’s logo, and pattern, the signage can work to better inform and guide community member and newcomers alike with either 1) clear and distinct way-finding information as opposed to simply a map of the overall area, 2) the community’s mission statement or values, 3) or inform of potential activities and doings in the area that correlate to the brand’s values (i.e. tours of the historic Knowles building, workshops on the correlation between wellness and exercise, bike races). The bookmark, while it features an intro paragraph to the brand and the brand’s purpose, fails to bolster the brand’s values by having a vague image of a skateboard wheel as the brand imagery rather than an individual skating, biking, or walking. The brand imagery focus needs to align with the brand’s intention of placing the responsibility of the pursuit of one’s own individual wellness on the community member, and to highlight the plethora of activities and sports that they themselves could engage in. Essentially, the way to correct these issues is to remember that the brand’s focus is not on bikes or skateboards themselves but the importance of the target demographic going out and facilitating wellness through utilizing those items as tools, in the pursuit of wellness, fun, adventure, and active community involvement.

Will the brand identity and asset designs be perceived as appropriate to the brand attributes?

The overall brand identity, and more effective asset designs, such as the motion graphic encapsulates the cheerfulness and friendliness of the brand with the use of the tetradic color palette. Inclusivity, as a key value of the brand welcomes every member of the target demographic to pursue their own individual wellness through exercise, motion, and fun.

The decision to use a tetradic color palette allows the brand to encapsulate the colors of the man-made and natural elements that can be found in the Mytle St. area and allows the color palette the freedom and flexibility to work in different shades or tints as necessary to bolster not only brand messaging, but also the attainability and tangible nature of the brand and all that it offers. The importance placed on target demographic to engage in outdoor activities and sports works to incite action in the target demographic, but also allows for community involvement and the opportunity to interconnect the community through shared activities and experiences.

Does the design convey the intended message?

The developed brand works to convey the intended message of: “Be adventurous. Seek wellness. Have fun!”. Through the contemporary use of san-serif typefaces in different weights, to the tetradic color palette, the brand speaks specifically to the target demographic of twenty to thirty somethings that desire wellness, adventure, fun, and inclusivity. The design elements of the brand uphold the voice and tone and bolsters the brand’s mission: “Adventure is right here! We believe change starts within. Through the transformative and healing power of the outdoors we strive to interconnect our all-inclusive community in the pursuit of wellness and fun. Come join us!”. The use of arrows as a critical shape and key symbol of the brand from the design elements to the logo itself maintains not only the encouragement of motion and sportiness of the brand, but is also reminiscent of two-way street signs or the arrow and bike symbols a community member would see on local bike paths in the area. All of these elements uphold the message of the brand, and aligns with the brand’s solution statement: “While the budding identity for the Myrtle St. area cannot fix the mental health and well-being of its individual citizens it can provide a shift in perspective and be known as an outdoor hub for cyclists, pedestrians, and more to engage in wellness through exercise, experiencing the outdoors, and instill a purpose into the community.

Are the media choices effective in sharing the community's brand?

The completed motion graphic, pole banners, and sticker are effective in sharing the community’s brand in that these specific assets maintain cohesion of the brand; not only of the brand’s visual voice and design, but also speak directly to the brand’s target demographic. The strategic purpose of the motion graphic is to promote the Myrtle St. brand on the target demographic’s most used social media platform, Facebook. By engaging the target demographic in social media, the motion graphic works to tell the story of the community and all it offers. There are two provided options for pole banners. The first option features relevant brand imagery and the Myrtle St. logo on both sides. The second, still features relevant brand imagery and the Myrtle St. logo, however it also provides an example of how the brand’s trademark arrows can be used for way-finding purposes in an effort to strategically direct new community members and visitors to key features and landmarks of the area. The effectiveness of keeping the Myrtle St. brand’s logo on the sticker makes the target demographic a walking advertisement for the community for every Myrtle St. sticker they place on their bikes, skateboards, long boards, car bumper, water bottle or laptop. The use of the brand’s pattern and color palette maintains cohesion with other brand elements and allows for easy identification of the brand’s tetradic color palette. Additionally, the strategic purpose of the sticker allows the Myrtle St. brand to go on adventures with community members which bolsters the adventurous value of the brand. These specific media choices work to guide and direct the target demographic to the brand, remind them of the brand, it’s value, and opportunities and paves the way to invite newcomers to join the community, and the fun.

Is the design expected or unexpected? Is that good or bad?

The final overall design is unexpected. The brand began by considering the target demographic’s question of, “What’s here for me?” and answered with an outdoor hub for cyclists, pedestrians, and more to engage in wellness through exercise, experiencing the outdoors, interconnect the community through shared outdoor and sporting activities, and invite everyone to join in on the fun, adventure, and pursuit of wellness. The use of the tetradic, or rather double-complimentary color palette avoids self-referential design, and while at times tricky to balance, allows varying opacities of the color palette to work together to convey a message and allows one specific color to be the main carrier of the intended message. The arrows as symbols, and as a shape for the brand’s design elements and logos convey motions, sports, and is reminiscent of arrow street signs or markings along bike paths that community members would see. The excitement and cheerful nature of the brand is a surprise to the target demographic that initially only considered the area’s pot-holes, poor infrastructure, and lack of jobs as all that the Myrtle St. area had to offer. Now, the unexpected design offers them a solution to embrace, opportunities to engage in, and invites the target demographic to take part in the community that was previously perceived as lack luster.

Is there anything about the design that should be finessed, adjusted, or reconsidered?

Without a doubt, further explorations on the tonality of yellow and its readability issues in publications and media needs to be further explored and addressed. Consistency in the use of the brand’s pattern and further implementation of the brand’s textures in various media and assets needs to be further explored and applied. Two of the brand’s key roll-out assets, such as the main signage and bookmark need further development in an effort to re-align the assets to the brand’s overall vision. The previously completed Dynamic Vision Board needs to be reconsidered in that the incorporation of brand textures and colors, in the use of overlaid shape layers as luma-mattes were see as too psychedelic and deviates from the brand’s established voice and tone in its pseudo-experimental nature. With the finessed yellow, the adjusted bookmark and signage, and reconsidered Dynamic Vision Board, these critical assets and improved color palette can work to further bolster and represent the Myrtle St. brand.

References:

Airey, D. (2015). Logo Design Love, Second edition: A guide to creating iconic brand identities. United States: New Riders.

Chan, S. (2016). How To Create a Brand Style Guide. Available at: https://99designs.com/blog/logo-branding/how-to-create-a-brand-style-guide/

Diogo, J. (2013, February 20). Jamie Oliver - Brand Book. Available at: https://issuu.com/joaodiogo/docs/frv-brand-guidelines-_final_

Fanguy, W. (2018, May 17). Running a successful post-mortem. Available at: https://www.invisionapp.com/inside-design/running-successful-post-mortem/

Forsite. (2018, November 16). 5 Benefits of Wayfinding Signage for Your Residential Community. Available at: https://www.mailboxesandsigns.com/blog/2018/posts/5-benefits-of-wayfinding-signage-for-your-residential-community/

Free-PSD-Mockups. (n.d.). Free PSD Mockups. Available at: https://free-psd-templates.com/category/mockups-in-psd/

Glitschka, V. (2016, August 10). Logo Design: Illustrating Logo Marks. Retrieved June 4, 2019, from: https://www.lynda.com/Illustrator-tutorials/Foundations-Logo-Design-Illustrating-Logo-Marks/475455-2.html?org=fullsail.edu

Haley, N. (2012, July 9). Olympics: User Experience and Design. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/blogs/internet/entries/1a12229f-fe09-3e2f-bc93-e962569a4a29

Murphy, L. (n.d.). 7 Reasons Motion Graphics Will Enhance Your Digital Marketing. Available at: https://www.harpinteractive.com/blog/2018/01/7-reasons-motion-graphics-enhance-digital-marketing/

Nicholson, J. (n.d.). 9 Reasons to Consider Old School Sticker Marketing. Available at: https://ducttapemarketing.com/sticker-marketing/

Playground, Inc. (n.d.). Designing a New Playground Brand. Available at: https://playgroundinc.com/blog/finding-and-redefining-playground-brand

Ray, H. (2018, March 10) How To Proceed With Sketching Of Logo Design. Available at: https://www.designhill.com/design-blog/how-to-proceed-with-sketching-of-logo-design/

Reid, M. (2019, April). Brand imagery: how to select images to represent your organization. Available at: https://99designs.com/blog/tips/brand-imagery/

Stone, T.L. (2013, September 12). Running a Design Business: Creative Briefs, Chapter 7: Evaluating Creative Briefs. Retrieved June 24, 2019, from https://www.lynda.com/Design-Business-tutorials/Evaluating-design-based-creative-brief/114320/148463-4.html?org=fullsail.edu

Valdez, A. (2017, October 9). Free sticker PSD mockup. Available at: https://axelvaldez.mx/blog/2017/10/free-sticker-psd-mockup/

Workerbee [username]. (2018, September) How to optimize your workflow as freelance graphic designer. Available at: https://99designs.com/blog/freelancing/optimize-workflow-designers/

0 notes

Text

Top 3 Slot Games in Malaysia

Sign up

or

Login

Let’s Start This Article With a Riddle, Shall We?

You can find me on land, you can see me on screen; I can let you win a crock of gold, but that is only if your luck is on the roll.

Did you guess it? It is a slot machine!

In the old days, slot machines were known as one-armed bandits because they had the “power” to make a hole in your wallet and pocket (bandit), and you would have to pull a large lever on the side of the machine (one arm) to start the game. How witty!

Slot machines were first introduced to the world in 1894 by a Bavarian-born American inventor, Charles August Fey. Since then, slots have become part of communal entertainment found in bars, restaurants, and casinos.

With the inevitable passing of time and technology evolvement, slot machines once again made tremendous progress as men make modifications to it with the help of technology sciences. Now, instead of playing slot games at a physical location only, people from all corners of the world can share the fun at any time through their electronic devices, thanks to the creation of online slot games.

Game developers and providers are making online slot games so accessible that you can now play over hundreds of games (on top of new ones) with your laptop, tablet, mobile phone, and desktop. Talk about playing mobile slots when you are taking a bubble bath in a tub!

Online slot games have the same gameplay as the ones on a traditional machine. The reels spin and stop to show a series of mixed icons. To win, you need to hit different combinations and patterns of icons. You can access real money slots too. Online slot games have more reels and pay lines, and the game starts with a click on the lever button.

Among all electronic gadgets, the mobile slot game is the most consumed sector because it gives gaming businesses a platform to put up their products to a larger market, which will result in a higher play rate. Mobile slots are compatible with any mobile operating systems (Android, iOS, windows, etc.).

This is why slot games are so welcomed in the community. Because it is easy to get started, there are little to no risks, and it is convenient.

Facts aside, I will proceed to share with you the top 3 slot games in Malaysia that you cannot miss! They are Joker123, 918Kiss, and Mega888.

JOKER123

Joker123 has made its debut recently and it is one of the younger slot games providers in the market. Although new, Joker123 is committed to becoming an outstanding and professional online slot games provider.

Other than being well-known for their broad range of slot games, Joker123 also creates its versions of digital baccarat, roulette, arcade, fishing, single-player and other classic casino table games. Besides, knowing that the gaming community is constantly looking out for new games, Joker123 takes a proactive approach in developing and adding more options to their collection from time to time to keep the platform fresh.

Since we are on the topic of mobile slot games, let me introduce you to some of the most played mobile slot games on Joker123. To name a few, there are YGG Drasil, Lady Hawk, 5 Dragons, Aladdin, Ancient Egypt, Archer, Captain Treasure, and Beanstalk. These games are five-reel slots machine, with pay lines varying from 9 to 25, and have a high prize pool.

It is easy to tell from the names that these slot games are made up of different styles and themes. For some, they adapt ideas from Disney animations and add their twists to it, with other games are original ideas from Joker123. Needless to say, the graphics are very dynamic and it gets better with the sound effects that change following the progress of the game. The interface is user-friendly, and most importantly, the games run smooth.

A majority of players have given a 4 out of 5 or full-star rating to these slot games, so take caution! Once you start, it is difficult to exit the game because it gets addictive!

Here’s an Extra Tip: -

There is a setting in Joker123 that lets you “heart” your favourite games. When you click on the green button (the “heart” that comes with all games), the site automatically saves that game in the favourite category. So when you exit and visit Joker123 the next time, you don’t have to search for it.

Joker123 is compatible with Android and iOS. You can head over to their website to get the application download link. There is also a section on the site that guides you with the download process with images. If you encounter any problems, click on the live chat box and you will be greeted promptly by customer service.

918KISS

With 11 years of experience in the industry, 918Kiss expands its business across South East Asia and leaves footprints on countries like Brunei, Singapore, and our very own motherland. It is also the only online betting platform that lets you play its games without the internet!

918Kiss has card games, arcade games, and slot games. One of the mobile slot games that players frenzy over currently is Three Kingdoms Quest. It is a five-reel slot machine with a 9-pay line. Other than a high pay out, I cannot help but emphasize the visuals of this free slot game. It brings about an Ancient Chinese theme, the background of the game is a realistic representation of the Chinese countryside, and the symbols on the reels are intricate designs plus drawings of Chinese warriors, bow and arrows, goddesses, and magnificent animals such as horses and dragons. They have accurately presented the Chinese culture in an elegant yet captivating way and it surely helps players immerse themselves in the game more.

Other slot games such as Gong Xi Fa Cai and Ocean King boast of higher RTF rating up to 95%, better odds at winning cash prizes and other bonuses on specific pay lines. The 243 and 1024 Ways to Win slot games are also available in 918Kiss, on top of the conventional 9, 15, 20, 25, 50, and 100 pay lines.

Sometimes, 918Kiss puts in surprise promotions on their platform that lets players stand a chance at winning mysterious rewards!

Progressive Slots

If you are hoping to play progressive slots, look out for mobile slot games such as WOW Prosperity, Ming Dynasty, Shang Hai 008, Zeus, Magic Hammer, and Dolphin Reef. Playing any one of these games can give you a shot at being a multimillionaire since the pay out is skyrocketing!

Over the years, 918Kiss has amassed countless loyal customers for the reason that the business is mindful of the customers’ feedback and put in the effort to better their services. In return, these customers put in good reviews which help drive visibility of 918Kiss in the mobile slots community. There is a 128-bit SSL encryption in place that protects the leaking of private information and prevents hackers from meddling with the gaming interface.

MEGA888

Since its launch back in 2018, Mega888 rose to popularity, became a top-rated online slot game provider, and expanded its territory to our neighbouring countries such as Thailand and Indonesia. It is especially sought-after by our local players and Singaporeans, owing to its vast variety of themes and great odds. The demand for Mega888 is unstoppable!

Tables games, classic casino table games, arcade games, and the likes are available in Mega888. They take pride in the way they develop their games. Not only do they have unique themes and layouts, but each game is created catering to the players’ preferences and that means the game interfaces are made straightforward, so it is easier for players to adapt from traditional betting to online games. There is also a beginner’s guide to help players familiarize themselves with the games.

If you are new to betting in general, Mega888 provides free trials that you can take advantage of to practice and understand the games, before placing monetary bets.

There are about a hundred different types of slot games in Mega888. Some of their best games are Great Blue, five-reel slot machine with 25 pay lines; Dolphin Reef, five-reel slot machine with 20 pay lines; and the mighty legendary figure Sun Wukong, five-reel slot machine with 15 pay lines. The slot games in Mega888 are known for having high jackpot accumulation. Matter fact, there had been a few players that scored jackpot from playing other slot games, which were Da Sheng Nao Hai and Ocean King. Read along to find out 2 basic tips players swear by to have a higher chance at winning.

Tip 1: Keep switching

Don’t just stick to one game! Try as many games as you can, so you can get the hang of different winning patterns. Once you do, you learn to notice these patterns instinctively and the chances of winning become higher.

Tip 2: Know when to stop

Set a winning condition so when you win, you know enough to stop. Similarly, set a losing condition. As you reach the point, you will not further your games, so you won’t lose more money than you initially plan to.

Mega888 Android

If you haven’t noticed, when you download a mobile online casino app, you are likely doing so on the online casino’s website, where you will come across a link which once clicked, the website reroutes and you will be presented with instructions, links or maybe a QR Code that will essentially help you download the app to your phone.

The reason you cannot download any mobile online casino app on an Android play store is that real-money betting mobile app is strictly forbidden. This is why online casinos such as Mega888 put in so much effort into making mobile apps available and compatible with any mobile phone operating system, so people around the globe can enjoy the fun and have a chance at winning anywhere at any time.

Having to go back and forth between the website and your phone only to download an app seems like a lot of work, but trust when I say this – it is safer to download your app via the website because these casino operators can block any risky security problems and bugs that can mess with your device.

Mobile slots are no different from any other physical machine. Just like Mega888 Android slot games, they are designed to fit the screen of your phone while retaining its resolution, with hundreds of free and real-money betting option to select from, and you are entitled to perks such as claiming free spins and promotional incentives.

Being able to play your favorite games on the go and in such a compact manner has made entertainment that much accessible. I hope you can have a pleasurable experience playing the slot games recommended!

Sign up

or

Login

Top 3 Slot Games in Malaysia published first on https://9kingapp.tumblr.com

0 notes

Text

Starting a Career in User Experience Design (UX): Nearly Everything You Need to Know

If you’re a creative type, a problem solver, an empathetic listener, or a combination of all three, a career in User Experience might be a perfect entry point for your pivot into the tech industry.

Yes, working in tech CAN happen through more familiar tech roles like web development or web design, but User Experience (or UX or UX design as you’re likely to see it referred to) offers a chance to work on people-first projects while still reaping all the benefits of tech’s high starting pay and flexible schedules.

But what IS UX? And how exactly can you start working in the field?

It’s funny you should ask. We’ve put together this ultimate guide running down everything you need to know (and then some) about finding work as a UX designer (or any other role that falls under the UX professional umbrella).

Don’t feel pressured to take in all this information at once! Bookmark this page and come back as often as you need when you start charging ahead on your own UX odyssey.

And one last thing: make sure to download our free UX Industry Info Sheet from the top or bottom of this page and take some of the most salient UX facts and figures with you.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: What is User Experience?

Chapter 2: UX Skills and Tools

Chapter 3: What is a UX Designer Salary?

Chapter 4: How to Find a UX Job

Chapter 5: Freelancing in UX

Chapter 6: UX + Bonus Digital Skills

Chapter 7: Final Thoughts

Chapter 1: What is User Experience? What is UX Design? And What About UI? Definitions please!

User Experience: A Definition

Ok, first thing’s first: a quick definition of user experience.

UX, the tech acronym for “User Experience”, is a tech field that involves researching groups of people who use digital products (like websites and apps) and using the findings to literally improve users’ experiences with those products—the way a product makes the user feel while they use its features, how easy the product is to use, and how appealing users find the product overall.

Then, What is a UX Designer?

UX is often interchangeably referred to as UX design (and UX professionals are more often than not called UX designers). This can be misleading (and confusing!) because there’s more to user experience than just the “design” component. It’s also important to keep in mind that you don’t need a traditional design background to work in UX.

But if there’s more to UX than design (and if “UX design” differs from traditional print and digital design) what do UX designers and other UX professionals actually do?

What do UX Designers (and other UX professionals) do?

The UX process can be broken down into three general categories (which show up to varying degrees in any UX job based on specific job descriptions and what your particular employer is looking for).

These categories are:

UX Research. Research is the foundation of UX. Without researching customer experience through interviews, product testing, etc, there’s no data to use against product changes and improvements—which basically means no UX. UX research plays a part in every step of the UX process, but can also be its own UX career path (proving there’s more to UX than “UX design”).

Information Architecture. Information Architecture is the heart of “design” in UX design. After user research has been collected, it’s time for UX designers to craft a strategy for implementing that data—in other words, a user experience design.

Product Iteration Testing. Part of what makes UX such a great field for creatives is the fact that it isn’t a factory line process. You don’t mindlessly crank out a UX design, call it “done” and move on to the next one. Instead, iteration is a critical part of UX, allowing UX researchers, designers, and other industry professionals to apply their creative problem solving to multiple versions of a product during its development lifetime.

Product iteration testing is the stage in the UX process where a current version of a product is presented to clients, users, and other stakeholders, after which collected impressions are applied to the next product version.

And Then There’s UI

To add to the fun, when you start reading up on UX and UX design you’ll probably notice mention of “UI” as well—sometimes even in the same breath (as “UX UI”). Is UI just another way of saying UX? Well, not really.

Think of it this way: if UX deals with EVERYTHING related to a brand or product experience, (tech shorthand for “User Interface”) is one piece of this bigger picture. UI operates on the same basic principles and methodology of UX, but focuses these skills specifically on a product’s interface (a website’s or app’s menu, screen layout, sitemap, form placement, etc).

In this sense, UI design can be considered more adjacent to traditional web or graphic design than general UX, making it a particularly good transition point into the industry if you DO already have print or digital design experience.

Bonus Reads:

Tech 101: UX Versus UI—What’s The Difference We take an even deeper dive into UX basics and what UX UI designers do on the job in this Tech 101 article, plus we cover UX skills and UX salaries (discussed below, as well).

I’m a UX Designer—Here’s What I Do All Day Get a first hand account of what it’s like to work as a UX designer.

(back to top)

Chapter 2: The UX Skills and Tools You’ll Need to Become a UX Designer

Some of the skills needed to land and succeeded at a job in UX don’t require a single day of UX training. As mentioned above, if you like to listen to people and understand their problems, if you enjoy critical thinking and problem solving challenges, or if you excel in creative environments, you’re already off to a good start.

But what about the UX-specific skills you’ll need to add to your toolkit if you want to work in UX UI?

Here’s a snapshot look at the crucial skills needed for each of UX’s primary areas (and don’t hesitate to consult this companion article if you need a deeper definition for any of the skills listed).

UX Research Skills

Personas (fictional user profiles used to model customer groups)

Journey Mapping (building visual representations of a user’s “journey” with a product)

Design Ideation (the UX version of “brainstorming,” sometimes done alongside clients and product stakeholders)

Information Architecture Skills

Navigation and Layout Best Practices (while traditional design has best practices for elements like color and typography, UX and UI design have their own best practices when it website and web application layout and design, as described in this UX Planet article)

Wireframing (the process of creating visual wireframe models used to map out the basic structure of a website or application.

Prototyping (the next step up from wireframing—prototypes are a more fleshed out website or app model, building on basic wireframe concepts and giving users a sample version of a product that they can interact with)

Product Iteration Testing Skills

Usability Testing (a product testing method where UX designers or researchers observe customers using a product and anay;uze how easy and enjoyable the user experience is)

A/B Testing (product testing where users are introduced to a product iteration (version A) alongside a version with slight design variations (version B) and UX designers/researchers observe which version the user base prefers)

UX Tools

In addition to skills, tools are an important part of the UX trade.

Two of the most must-learn UX tools recommended by our own curriculum team are:

Figma (an industry-standard design tool for creating website and web application wireframes)

Invision (a powerful software tool that lets UX designers create interactive website prototypes to test with real users)

Both Figma and Invision are intuitive and easy to learn (making them ideal for beginners), but they’re also industry standard programs used by UX pros worldwide. Even better, they are free to use when starting out. Both tools offer no-cost plans that allow you to complete and store up to three full projects, which is perfect when you’re learning the ropes en route to paid work.

Alongside these two programs, other recommended UX UI tools include:

Axure (another prototyping tool for web and desktop applications)

Balsamiq (a User Interface design tool for making digital sketches, wireframes, and mockups)

UXPin (a full-service UX design platform for every stage of the UX process—designing, collaborating, and presenting to clients and test users)

Where to Learn UX Skills

If you’re wondering where you can start learning these skills and tools, that part’s easy. Look no further than our Skillcrush User Experience Design Blueprint—an online course designed to be completed in only 3 months (if you spend about an hour a day). Our course will walk you step-by-step through the skills listed above, as well as get you hands on with Figma and Invision.

Bonus Reads:

How to Talk User Experience (UX): 10 Key Terms to Help You Talk the Talk A handy glossary of 10 critical UX terms

5 Crucial Steps in the UX Process That Your Client Wants to See A five-step look at the UX design process

UXPin Free Books A library of free UX-related e-books

(back to top)

Chapter 3: What is a UX Designer Salary?

Ok, enough hype about the job itself, let’s get down to brass tacks: how much can you expect to make working as a UX UI designer?

When we posed the UX designer salary question previously, Alison Sullivan, Career Trends Expert at jobs and recruiting site Glassdoor, reported that Glassdoor cites an average base salary of $107,880 for UX designers and an average base salary of $86,883 for UI designers.

She added that—in addition to the money—UX design jobs ranked #27 out of 50 among Glassdoor’s recent Best Jobs in America report, a claim that’s reflected by Glassdoor’s own job listings. As of this writing, Glassdoor has over 5,000 UX designer jobs posted on its site, and nearly 5,000 UI designer openings.

You can read more about UX design salaries (and what it takes to earn them) here.

(back to top)

Chapter 4: How to Find a UX Job

Now that you have an idea of what UX is about, what kind of skills and tools you need to work as a UX designer, and how much money you can expect to make, how exactly do you go about finding a UX job?

Besides staying on top of job boards like Glassdoor and Indeed (as well as as UX-specific boards like the aptly named UX Jobs Board, UX Design Jobs, and Smashing Jobs, there are some proactive things you can do on your end to up your qualifications for those job listings.

1. Get Your Mock Project On

Just because you’re not getting paid to do UX work yet doesn’t mean you shouldn’t be doing UX work.

Huh?

Let me explain: one of the best way to gain experience and have a demonstrable body of work before getting hired for your first job is to harness your UX skills as you learn them and start working on mock projects.

Use Figma or Invision to create wireframes and prototypes of a UX rebranding for a website or application (it can be fictitious, or even a spec project overhealing the UX of one of your favorite real world sites or apps). By creating a mock body of work en route to your first paid gig, you’ll be able to show potential clients (and yourself!) what you can do.

This article on how to create a web design portfolio with mock projects can be applied to UX as well.

2. Then Get Your Portfolio in Order

Having a crisp, easily shareable digital portfolio is a must in order to win over UX clients and hiring managers. But what does that mean?

First, you need to find the right site to house your digital samples. This article on free design portfolio sites will lead you in the direction of stalwarts like Behance and Dribbble, both of which work just as well for UX portfolios as they do for web and visual design.

Second, you need to make sure you’re including the kind of UX samples that will resonate with clients and employers. This article will give you a list of seven foundational projects to start building a stellar UX portfolio, after which you can level up your portfolio game even further with this 4-step guide to making sure your work shines.

3. Have an Elevator Pitch on Standby

In between trolling job listings and compiling a knockout portfolio, life sometimes just happens. You never know when you might be in a situation where you’re suddenly face-to-face with someone who can hook you up with that dream UX job. Which means you better have something to say when and if the time comes.