#foundation haiti jazz

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Watch "KREOL JAZZ PROJECT" on YouTube

youtube

#kreol jazz project#kreyol jazz project#creole jazz#Caribbean jazz#caribbean fusion jazz#fusionjazz#foundation haiti jazz#pap jazz#haiti legends#haitian Jazz#martinique#Guadeloupe#african jazz#haitian jazz#Youtube

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Win Butler Of Arcade Fire On Working With Preservation Hall To Establish A New Mardi Gras Tradition In Krewe Du Kanaval

Each year on January 6, King Day in New Orleans, Carnival season begins, featuring numerous parade krewes marching throughout Mardi Gras in the run up to Fat Tuesday (also known as Shrove Tuesday), wrapping up each year the day before Ash Wednesday (February 26, 2020).

General knowledge of Mardi Gras outside New Orleans often begins and ends with the drunken revelry and Bourbon Street bead tossing most prominently featured in the media each year, lending a negative connotation to what, for locals, is an otherwise festive season steeped in tradition, music, culture and cuisine.

Win Butler and Régine Chassagne of Canadian indie rock group Arcade Fire moved to New Orleans in 2015. Like Talking Heads before them, Arcade Fire is an outfit impossible to pigeonhole, featuring in its musical stew everything from alternative and rock to baroque pop, punk, soul and more - which makes them a terrific fit in The Big Easy.

The musical heritage of New Orleans is defined by its inclusive nature, one which has always evolved as new people of all types come and go.

One of the single most important, and often overlooked, elements of New Orleans culture is its Haitian roots, influencing everything from music to food, even Creole language.

“It’s a historical fact that the population of New Orleans doubled in the early 1800s as a result of the Haitian revolution,” New Orleans native, Preservation Hall Creative Director and Preservation Hall Jazz Band multi-instrumentalist Ben Jaffe told Forbes last year. “10,000 people of Haitian and African heritage ended up finding their way to New Orleans - whether it was through Santiago de Cuba or directly to New Orleans. Honestly you can see and taste and feel Haiti in New Orleans.”

Chassagne was born in Canada to Haitian immigrants who fled the country in the 60s during the Francois Duvalier regime. Upon their arrival in New Orleans in 2015, Butler and Chassagne began a series of collaborations with Jaffe, eventually taking him on a trip to Haiti.

“New Orleans is sort of the source of huge cultural contributions to American society. Just from jazz to music, food and architecture - all of these things that are so unique within America. The first time I went to Haiti, I was like, ‘Wait a minute, this all looks familiar…,’” said Butler. “In the context of what Preservation Hall does, which has been to kind of perpetuate and preserve the legacy of jazz, I thought it would be cool for Ben to see sort of the motherland in a lot of ways. The first time he went to rural Haiti, and you’re just in the mountains and hearing these kids play - basically second lining through the mountains with brass instruments - you feel like you’ve found a time machine and went to pre-jazz New Orleans.”

That trip led to further work together and in 2018 Krewe du Kanaval was born, a joint effort between Jaffe, Butler and Chassagne on a series of events which make the connection between New Orleans and Haiti, celebrating both. The events have taken place annually since 2018 in what’s become a new part of the Mardi Gras tradition, embracing culture with the goal of giving back.

Kanaval Ball is an annual Krewe du Kanaval highlight. This year the concert features Arcade Fire’s first performance since wrapping up their “Everything Now�� tour as the group headlines the Ball for the first time on Friday, February 14, 2020 at Mahalia Jackson Theater in Louis Armstrong Park.

It’s a set Butler referred to as Arcade Fire’s “only show for a while” and, with a theme of “Merci Haiti,” will also feature Preservation Hall Jazz Band, Haitian DJ Michael Brun, Trinidadian electronic artist Jillionaire of Major Lazer, the uplifting sounds of Haitian collective Lakou Mizik, Congolese-Canadian pop musician Pierre Kwenders and more.

Proceeds from the Krewe du Kanaval events benefit Jaffe’s Preservation Hall Foundation and Chassagne’s KANPE Foundation. Preservation Hall Foundation works to preserve New Orleans heritage while KANPE targets helping Haiti’s most vulnerable. For Butler, Krewe du Kanaval’s philanthropic efforts were key.

“That was sort of the whole concept. We’re sort of plugging into a way of participating in Carnival that goes back a hundred years with Mardi Grew krewes. I think it was important for us to have something that was altruistic and entirely not for profit,” he said. “There’s sort of the cultural piece at the event but then there’s also the money actually getting back to the charity. And that’s sort of the concept of the whole thing: to kind of have a sustainable, annual event that, over time, raises significant money.”

In addition to the sales of concert tickets and merch, Krewe du Kanaval is largely membership driven. Following the Friday night concert, both Preservation Hall Jazz Band and Krewe du Kanaval are set to join the Krewe Freret parade on Saturday, February 15. Krewe du Kanaval members can join in the fun by marching along or riding on a pair of parade floats.

“I feel like before I moved to New Orleans, my conception of Mardi Gras was very limited. It was sort of this spring break, bacchanalia, French Quarter sort of caricature. Which I would say is maybe 10 or 15% of what’s actually going on at Mardi Gras. The actual, overwhelming culture of the city is this whole other thing. Carnival is ultimately sort of a spiritual event,” said Butler. “I feel like this is a good window into more of the real Mardi Gras. Even outside of our events, just in the city, there’s so much amazing stuff going on that’s not your typical plastic beads and Bourbon Street stuff. There’s a lot of really profound things going on. And I feel like Kanaval could be a jumping off point for people to discover that there’s a lot to discover.”

Even fifteen years later, New Orleans still hasn’t fully recovered from Hurricane Katrina. The situation in Haiti is even more dire following an earthquake in 2010 and Hurricane Matthew in 2016.

Once stories like that fall out of today’s quick news cycle, they have a tendency to be forgotten. As a result, the work being done by Jaffe’s Preservation Hall Foundation and Chassagne’s KANPE Foundation takes on increased importance.

“The area we’re working in is one of the most rural or remote areas in Haiti. We work with women who’ve never handled money. There’s really different levels of need,” said Butler, noting KANPE’s work in Haiti. “In Haiti, the brass band that we’ve kind of helped to support, ends up playing a lot of weddings and funerals and it just sort of provides structure and inspiration. It’s just a piece of it. I’ve been to places with no music but the same level of poverty and it just feels like a totally different place. It just tells you that there’s life. Music is the sound of life really,” he continued. “Haiti contributed all of this to the world kind of for free without asking anything. Because of the situation of the revolution, Haiti just brought all of this brainpower and culture and music and food - taught people how to grow coffee and sugarcane and make rum - and there’s this kind of incredible spreading of culture. A lot of these connections have been lost in time and I just think it’s a beautiful thing to pay tribute to it.”

Arcade Fire recorded their fifth studio album Everything Now in New Orleans. And as he gears up for this weekend’s Krewe du Kanaval events, Butler is clear on the profound impact his new home has had.

“I just feel like, a lot of places, if you tell people you’re a musician, there’s a lot of follow up questions. In New Orleans, it’s kind of the most normal thing you can do. There’s just a level of artistry that’s really inspiring. New Orleans offers a window into music as a way of life as opposed to music as a commodity,” he said. “My heroes are The Clash and bands that just weren’t really f—-king around - this music thing is life or death and it matters. And I feel like I’ve found in New Orleans a city that agrees with that basic premise. This is song and this is life but this sh-t is also life and death. It matters. It’s not an accident that some of the craziest music I’ve heard in New Orleans is at funerals. This is a step of life. It’s something that I’ve always sort of felt. I was raised to believe that. So it’s nice to be living in a city that knows that to be true.”

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Katherine Dunham

Katherine Mary Dunham (also known as Kaye Dunn, June 22, 1909 – May 21, 2006) was an American dancer, choreographer, author, educator, and social activist. Dunham had one of the most successful dance careers in American and European theater of the 20th century, and directed her own dance company for many years. She has been called the "matriarch and queen mother of black dance."

While a student at the University of Chicago, Dunham took leave and went to the Caribbean to study dance and ethnography. She later returned to graduate and submitted a master's thesis in anthropology. She did not complete the other requirements for the degree, however, and realized that her professional calling was performance.

At the height of her career in the 1940s and 1950s, Dunham was renowned throughout Europe and Latin America and was widely popular in the United States, where The Washington Post called her "dancer Katherine the Great". For almost 30 years she maintained the Katherine Dunham Dance Company, the only self-supported American black dance troupe at that time, and over her long career she choreographed more than ninety individual dances. Dunham was an innovator in African-American modern dance as well as a leader in the field of dance anthropology, or ethnochoreology. She also developed the Dunham Technique.

Early years

Katherine Mary Dunham was born on June 22, 1909 in a Chicago hospital and taken as an infant to her parents' home in Glen Ellyn, Illinois, a village about 25 miles west of Chicago. Her father, Albert Millard Dunham, was a descendant of slaves from West Africa and Madagascar. Her mother, Fanny June Dunham (née Taylor), who was of mixed French-Canadian and Native American heritage, died when Dunham was three years old. She had an older brother, Albert Jr., with whom she had a close relationship. After her father's remarriage a few years later, the family moved to a predominantly white neighborhood in Joliet, Illinois, where her father ran a dry cleaning business.

Dunham became interested in both writing and dance at a young age. In 1921, a short story she wrote when she was 12 years old called "Come Back to Arizona" appeared in volume 2 of The Brownies' Book.

In high school she joined the Terpsichorean Club and began to learn a kind of modern dance based on the ideas of Jaques-Dalcroze and Rudolf von Laban. At a young age, Dunham organized a cabaret party to raise money for her church in which she starred in. At the age of 15, she organized the Blue Moon Café, a fundraising cabaret for Brown's Methodist Church in Joliet, where she gave her first public performance. While still a high school student, she opened a private dance school for young black children.

Academic anthropologist

After completing her studies at Joliet Junior College, Dunham moved to Chicago to join her brother Albert, who was attending the University of Chicago as a student of philosophy. In a lecture by Robert Redfield, a professor of anthropology, she learned that much of black culture in modern America had begun in Africa. She consequently decided to major in anthropology and to focus on dances of the African diaspora. Besides Redfield, she studied under anthropologists such as A.R. Radcliffe-Brown, Edward Sapir, and Bronisław Malinowski. Under their tutelage, she showed great promise in her ethnographic studies of dance.

In 1935, Dunham was awarded travel fellowships from the Julius Rosenwald and Guggenheim foundations to conduct ethnographic study of the dance forms of the Caribbean, especially as manifested in the Vodun of Haiti, a path also followed by fellow anthropology student Zora Neale Hurston. She also received a grant to work with Professor Melville Herskovits of Northwestern University, whose ideas of African retention would serve as a platform for her research in the Caribbean.

Her field work in the Caribbean began in Jamaica, where she lived for several months in the remote Maroon village of Accompong, deep in the mountains of Cockpit Country. (She later wrote Journey to Accompong, a book describing her experiences there.) Then she traveled on to Martinique and to Trinidad and Tobago for short stays, primarily to do an investigation of Shango, the African god who remained an important presence in West Indian heritage. Early in 1936, she arrived in Haiti, where she remained for several months, the first of her many extended stays in that country through her life.

While in Haiti, Dunham investigated Vodun rituals and made extensive notes in her research, particularly on the dance movements of the participants. Years later, after extensive studies and initiations, she became a mambo in the Vodun religion. She also became friends with, among others, Dumarsais Estimé, then a high-level politician, who became president of Haiti in 1949. Somewhat later, she assisted him, at considerable risk to her life, when he was persecuted for his progressive policies and sent in exile to Jamaica after a coup d'état.

Dunham returned to Chicago in the late spring of 1936, and in August was awarded a bachelor's degree, a Ph.B., bachelor of philosophy, with her principal area of study named as social anthropology. She was one of the first African American women to attend this college and also to earn these degrees. In 1938, using materials collected during her research tour of the Caribbean, Dunham submitted a thesis, "The Dances of Haiti: A Study of Their Material Aspect, Organization, Form, and Function," to the Department of Anthropology at the University of Chicago in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master's degree, but she never completed her course work or took examinations to qualify for the degree. Devoted to dance performance, as well as to anthropological research, she realized that she had to choose between the two. Although she was offered another grant from the Rockefeller Foundation to pursue her academic studies, she chose dance, gave up her graduate studies, and departed for Broadway and Hollywood.

Dancer and choreographer

From 1928 to 1938

In 1928, while still an undergraduate, Dunham began to study ballet with Ludmilla Speranzeva, a Russian dancer who had settled in Chicago, having come to the United States with the Franco-Russian vaudeville troupe Le Théâtre de la Chauve-Souris directed by impresario Nikita Balieff. She also studied ballet with Mark Turbyfill and Ruth Page, who became prima ballerina of the Chicago Opera. Through her ballet teachers, she was also exposed to Spanish, East Indian, Javanese, and Balinese dance forms. In 1931, when she was only 21, Dunham formed a group called Ballets Nègres, one of the first black ballet companies in the United States. After a single, well-received performance in 1931, the group was disbanded. Encouraged by Speranzeva to focus on modern dance instead of ballet, Dunham opened her first real dance school in 1933 called the Negro Dance Group. It was a venue for Dunham to teach young black dancers about their African heritage.

In 1934–36, Dunham performed as a guest artist with the ballet company of the Chicago Opera. Ruth Page had written a scenario and choreographed La Guiablesse ("The Devil Woman"), based on a Martinican folk tale in Lafcadio Hearn's Two Years in the French West Indies. It opened in Chicago in 1933, with a black cast and with Page dancing the title role. The next year it was repeated with Katherine Dunham in the lead and with students from Dunham's Negro Dance Group in the ensemble. Her dance career was then interrupted by her anthropological research in the Caribbean.

Having completed her undergraduate work at the University of Chicago and having made the decision to pursue a career as a dancer and choreographer rather than as an academic, Dunham revived her dance ensemble and in 1937 journeyed with them to New York to take part in A Negro Dance Evening organized by Edna Guy at the 92nd Street YMHA. The troupe performed a suite of West Indian dances in the first half of the program and a ballet entitled Tropic Death, with Talley Beatty, in the second half. Upon returning to Chicago, the company performed at the Goodman Theater and at the Abraham Lincoln Center. Dunham's well-known works Rara Tonga and Woman with a Cigar were created at this time. With choreography characterized by exotic sexuality, both became signature works in the Dunham repertory. After successful performances of her company, Dunham was named dance director of the Chicago Negro Theater Unit of the Federal Theatre Project. In this post, she choreographed the Chicago production of Run Li'l Chil'lun, performed at the Goodman Theater, and produced several other works of choreography including The Emperor Jones and Barrelhouse.

At this time Dunham first became associated with designer John Pratt, whom she later married. Together, they produced the first version of her dance composition L'Ag'Ya, which premiered on January 27, 1938, as a part of the Federal Theater Project in Chicago. Based on her research in Martinique, this three-part performance integrated elements of a Martinique fighting dance into American ballet.

From 1939 to the late 1950s

In 1939, Dunham's company gave further performances in Chicago and Cincinnati and then went back to New York, where Dunham had been invited to stage a new number for the popular, long-running musical revue Pins and Needles 1940, produced by the International Ladies' Garment Workers Union. As this show continued its run at the Windsor Theater, Dunham booked her own company in the theater for a Sunday performance. This concert, billed as Tropics and Le Hot Jazz, included not only her favorite partners Archie Savage and Talley Beatty but her principal Haitian drummer, Papa Augustin. Initially scheduled for a single performance, the show was so popular that the troupe repeated it for another ten Sundays.

This success led to the entire company being engaged in the 1940 Broadway production Cabin in the Sky, staged by George Balanchine and starring Ethel Waters. With Dunham in the sultry role of temptress Georgia Brown, the show ran for 20 weeks in New York before moving to the West Coast for an extended run of performances there. The show created a minor controversy in the press.

After the national tour of Cabin in the Sky, the Dunham company stayed in Los Angeles, where they appeared in the Warner Brothers short film Carnival of Rhythm (1941). The next year Dunham appeared in the Paramount musical film Star Spangled Rhythm (1942) in a specialty number, "Sharp as a Tack," with Eddie "Rochester" Anderson. Other movies she appeared in during this period included the Abbott and Costello comedy Pardon My Sarong (1942) and the black film musical Stormy Weather (1943).

The company returned to New York, and in September 1943, under the management of the impresario Sol Hurok, her troupe opened in Tropical Review at the Martin Beck Theater. Featuring lively Latin American and Caribbean dances, plantation dances, and American social dances, the show was an immediate success. The original two-week engagement was extended by popular demand into a three-month run, after which the company embarked on an extensive tour of the United States and Canada. In Boston, then a bastion of conservatism, the show was banned in 1944 after only one performance. Although it was well received by the audience, local censors feared that the revealing costumes and provocative dances might compromise public morals. After the tour, in 1945, the Dunham company appeared in the short-lived Blue Holiday at the Belasco Theater in New York and in the more successful Carib Song at the Adelphi Theatre. The finale to the first act of this show was Shango, a staged interpretation of a Vodun ritual that would become a permanent part of the company's repertory.

In 1946, Dunham returned to Broadway for a revue entitled Bal Nègre, which received glowing notices from theater and dance critics. Early in 1947 Dunham choreographed the musical play Windy City, which premiered at the Great Northern Theater in Chicago, and later in the year she opened a cabaret show in Las Vegas, during the first year that the city became a popular entertainment destination. Later that year she went with her troupe to Mexico, where their performances were so popular that they remained for more than two months. After Mexico, Dunham began touring in Europe, where she was an immediate sensation. In 1948, she opened A Caribbean Rhapsody first at the Prince of Wales Theatre in London, then swept on to the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris.

This was the beginning of more than 20 years of performing almost exclusively outside the United States. During these years, the Dunham company appeared in some 33 countries in Europe, North Africa, South America, Australia, and East Asia. Dunham continued to develop dozens of new productions during this period, and the company met with enthusiastic audiences wherever they went. Despite these successes, the company frequently ran into periods of financial difficulties, as Dunham was required to support all of the 30 to 40 dancers and musicians.

Dunham and her company appeared in the Hollywood movie Casbah (1948) with Tony Martin, Yvonne De Carlo, and Peter Lorre, and in the Italian film Botta e Risposta, produced by Dino de Laurentiis. Also that year they appeared in the first ever hour-long American spectacular televised by NBC when television was first beginning to spread across America. This was followed by television spectaculars filmed in London, Buenos Aires, Toronto, Sydney, and Mexico City.

In 1950, Sol Hurok presented Katherine Dunham and Her Company in a dance revue at the Broadway Theater in New York, with a program composed of some of Dunham's best works. It closed after only 38 performances, and the company soon thereafter embarked on a tour of venues in South America, Europe, and North Africa. They had particular success in Denmark and France. In the mid-1950s, Dunham and her company appeared in three films: Mambo (1954), made in Italy; Die Grosse Starparade (1954), made in Germany; and Música en la Noche (1955), made in Mexico City.

Later career

The Dunham company's international tours ended in Vienna in 1960, when it was stranded without money because of bad management by their impresario. Dunham saved the day by arranging for the company to appear in a German television special, Karibische Rhythmen, after which they returned to America. Dunham's last appearance on Broadway was in 1962 in Bamboche!, which included a few former Dunham dancers in the cast and a contingent of dancers and drummers from the Royal Troupe of Morocco. It was not a success, closing after only eight performances.

A highlight of Dunham's later career was the invitation from New York's Metropolitan Opera to stage dances for a new production of Aida with soprano Leontyne Price. Thus, in 1963, she became the first African-American to choreograph for the Met since Hemsley Winfield set the dances for The Emperor Jones in 1933. The critics acknowledged the historical research she did on dance in ancient Egypt but did not particularly care for the results they saw on the Met stage. Subsequently, Dunham undertook various choreographic commissions at several venues in the United States and in Europe. In 1967 she officially retired after presenting a final show at the famous Apollo Theater in Harlem, New York. Even in retirement Dunham continued to choreograph: one of her major works was directing Scott Joplin's opera Treemonisha in 1972 at Morehouse College in Atlanta.

In 1978 Dunham was featured in the PBS special, Divine Drumbeats: Katherine Dunham and Her People, narrated by James Earl Jones, as part of the Dance in America series. Alvin Ailey later produced a tribute for her in 1987-88 with his American Dance Theater at Carnegie Hall entitled The Magic of Katherine Dunham.

Educator and writer

In 1945, Dunham opened and directed the Katherine Dunham School of Dance and Theatre near Times Square in New York City after her dance company was provided with rent-free studio space for three years by an admirer, Lee Shubert; it had an initial enrollment of 350 students.

The program included courses in dance, drama, performing arts, applied skills, humanities, cultural studies, and Caribbean research, and in 1947 it was expanded and granted a charter as the Katherine Dunham School of Cultural Arts. The school was managed in Dunham's absence by one of her dancers, Syvilla Fort, thrived for about ten years, and was considered one of the best learning centers of its type at the time. Schools inspired by it later opened in Stockholm, Paris, and Rome by dancers trained by Dunham.

Her alumni included many future celebrities, such as Eartha Kitt, who, as a teenager, won a scholarship to her school and later became one of her dancers before moving on to a successful singing career. Others who attended her school included James Dean, Gregory Peck, Jose Ferrer, Jennifer Jones, Shelley Winters, Sidney Poitier, Shirley MacLaine and Warren Beatty. Marlon Brando frequently dropped in to play the bongo drums, and jazz musician Charles Mingus held regular jam sessions with the drummers. Known for her many innovations, Dunham developed a dance pedagogy, later named the Dunham Technique, that won international acclaim and that is now taught as a modern dance style in many dance schools.

By 1957, Dunham was under severe personal strain that was affecting her health, and she decided to live for a year in relative isolation in Kyoto, Japan, where she worked on writing autobiographies of her youth. The first work, entitled A Touch of Innocence: Memoirs of Childhood, was published in 1959. A continuation based on her experiences in Haiti, Island Possessed, was published in 1969, and a fictional work based on her African experiences, Kasamance: A Fantasy, was published in 1974. Throughout her career, she occasionally published articles about her anthropological research (sometimes under the pseudonym of Kaye Dunn) and sometimes lectured on anthropological topics at universities and scholarly societies.

In 1964, Dunham settled in East St. Louis and took up the post of artist-in-residence at Southern Illinois University in nearby Edwardsville. There she was able to bring anthropologists, sociologists, educational specialists, scientists, writers, musicians, and theater people together to create a liberal arts curriculum that would be a foundation for further college work. One of her fellow professors with whom she collaborated was architect Buckminister Fuller.

The following year, 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson nominated Dunham to be technical cultural adviser—that is, a sort of cultural ambassador—to the government of Senegal in West Africa. Her mission was to help train the Senegalese National Ballet and to assist President Leopold Senghor with arrangements for the First Pan-African World Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar (1965–66). Later she established a second home in Senegal and occasionally returned there to scout for talented African musicians and dancers.

In 1967, Dunham opened the Performing Arts Training Center (PATC) in East St. Louis as an attempt to use the arts to combat poverty and urban unrest. It served as a catharsis after the 1968 riots, during which she encouraged gang members in the ghetto to vent their frustrations with drumming and dance. The PATC drew on former members of Dunham's touring company as well as local residents for its teaching staff. While trying to help the young people in the community she was even jailed herself, making international headlines which quickly embarrassed local police officials to release her. She also continued refining and teaching the Dunham Technique to transmit that knowledge to succeeding generations of dance students, and lecturing at annual Masters' Seminars in St. Louis that attracted dance students from around the world every summer until her death. She also established the Katherine Dunham Centers for Arts and Humanities in East St. Louis to preserve Haitian and African instruments and artifacts from her own personal collection.

In 1976, Dunham was guest artist-in-residence and lecturer for Afro-American studies at the University of California, Berkeley. A photographic exhibit honoring her achievements, entitled "Kaiso! Katherine Dunham," was mounted at the Women's Center on the campus. In 1978, an anthology of writings by and about her, also entitled Kaiso! Katherine Dunham, was published in a limited, numbered edition of 130 copies by the Institute for the Study of Social Change.

Social activism

The Katherine Dunham Company toured throughout North America in the mid-1940s, even performing in the then-segregated South, where Dunham once refused to hold a show after finding out that the city's black residents had not been allowed to buy tickets for the performance. On another occasion, in October 1944, after getting a rousing standing ovation in Louisville, Kentucky, she told the all-white audience that she and her company would not return because "your management will not allow people like you to sit next to people like us", and she expressed a hope that time and the "war for tolerance and democracy" would bring a change. One historian noted that "during the course of the tour, Dunham and the troupe had recurrent problems with racial discrimination, leading her to a posture of militancy which was to characterize her subsequent career."

In Hollywood, Dunham refused to sign a lucrative studio contract when the producer said she would have to replace some of her darker-skinned company members. She and her company frequently had difficulties finding adequate accommodations while on tour because in many regions of the country, black Americans were not allowed to stay at hotels.

While Dunham was recognized as "unofficially" representing American cultural life in her foreign tours, she was given very little assistance of any kind by the U.S. State Department. She had incurred the displeasure of departmental officials when her company performed Southland, a ballet that dramatized the lynching of a black man in the racist American South. Its premiere performance on December 9, 1950, at the Teatro Municipal in Santiago, Chile, generated considerable public interest in the early months of 1951. The State Department was dismayed by the negative view of American society that the ballet presented to foreign audiences. As a result, Dunham would later experience some diplomatic "difficulties" on her tours. The State Department regularly subsidized other less well-known groups, but it consistently refused to support her company (even when it was entertaining U.S. Army troops), although at the same time it did not hesitate to take credit for them as "unofficial artistic and cultural representatives."

The Afonso Arinos Law in Brazil

In 1950, while visiting Brazil, Dunham and her group were refused rooms at a first-class hotel in São Paulo, the Hotel Esplanada, frequented by many American businessmen. Understanding that the fact was due to racial discrimination, she made sure the incident was publicized. The incident was widely discussed in the Brazilian press and became a hot political issue. In response, the Afonso Arinos law was passed in 1951 that made racial discrimination in public places a felony in Brazil.

Hunger strike

In 1992, at age 83, Dunham went on a highly publicized hunger strike to protest the discriminatory U.S. foreign policy against Haitian boat-people. Time reported that, "she went on a 47-day hunger strike to protest the U.S.'s forced repatriation of Haitian refugees. "My job", she said, "is to create a useful legacy." During her protest, Dick Gregory led a non-stop vigil at her home, where many disparate personalities came to show their respect, such Debbie Allen, Jonathan Demme, and Louis Farrakhan, leader of the Nation of Islam.

This initiative drew international publicity to the plight of the Haitian boat-people and U.S. discrimination against them. Dunham ended her fast only after exiled Haitian president Jean-Bertrand Aristide and Jesse Jackson came to her and personally requested that she stop risking her life for this cause. In recognition of her stance, President Aristide later awarded her a medal of Haiti's highest honor.

Private life

Dunham married Jordis McCoo, a black postal worker, in 1931, but he did not share her interests and they gradually drifted apart, finally divorcing in 1938. About that time Dunham met and began to work with John Thomas Pratt, a Canadian who had become one of America's most renowned costume and theatrical set designers. Pratt, who was white, shared Dunham's interests in African-Caribbean cultures and was happy to put his talents in her service. After he became her artistic collaborator, they became romantically involved. In the summer of 1941, after the national tour of Cabin in the Sky ended, they went to Mexico, where inter-racial marriages were less controversial than in the United States, and engaged in a commitment ceremony on 20 July, which thereafter they gave as the date of their wedding. In fact, that ceremony was not recognized as a legal marriage in the United States, a point of law that would come to trouble them some years later. Katherine Dunham and John Pratt married in 1949 to adopt Marie-Christine, a French 14-month-old baby. From the beginning of their association, around 1938, Pratt designed the sets and every costume Dunham ever wore. He continued as her artistic collaborator until his death in 1986.

When she was not performing, Dunham and Pratt often visited Haiti for extended stays. On one of these visits, during the late 1940s, she purchased a large property of more than seven hectares in the Carrefours suburban area of Port-au-Prince, known as Habitation Leclerc. Dunham used Habitation Leclerc as a private retreat for many years, frequently bringing members of her dance company to recuperate from the stress of touring and to work on developing new dance productions. After running it as a tourist spot, with Vodun dancing as entertainment, in the early 1960s, she sold it to a French entrepreneur in the early 1970s.

In 1949, Dunham returned from international touring with her company for a brief stay in the United States, where she suffered a temporary nervous breakdown after the premature death of her beloved brother Albert. He had been a promising philosophy professor at Howard University and a protégé of Alfred North Whitehead. During this time, she developed a warm friendship with the psychologist and philosopher Erich Fromm, whom she had known in Europe. He was only one of a number of international celebrities who were Dunham's friends. In December 1951, a photo of Dunham dancing with Ismaili Muslim leader Prince Ali Khan at a private party he had hosted for her in Paris appeared in a popular magazine and fueled rumors that the two were romantically linked. Both Dunham and the prince denied the suggestion. The prince was then married to actress Rita Hayworth, and Dunham was now legally married to John Pratt; a quiet ceremony in Las Vegas had taken place earlier in the year. The couple had officially adopted their foster daughter, a 14-month-old girl they had found as an infant in a Roman Catholic convent nursery in Fresnes, France. Named Marie-Christine Dunham Pratt, she was their only child.

Among Dunham's closest friends and colleagues was Julie Robinson, formerly a performer with the Katherine Dunham Company, and her husband, singer and later political activist Harry Belafonte. Both remained close friends of Dunham for many years, until her death. Glory Van Scott and Jean-Léon Destiné were among other former Dunham dancers who remained her lifelong friends.

Death

On May 21, 2006, at the age of 96, Dunham died in her sleep from natural causes in New York City.

Legacy

Anna Kisselgoff, a dance critic for The New York Times, called Dunham "a major pioneer in Black theatrical dance ... ahead of her time." "In introducing authentic African dance-movements to her company and audiences, Dunham—perhaps more than any other choreographer of the time—exploded the possibilities of modern dance expression."

As one of her biographers, Joyce Aschenbrenner, wrote: "Today, it is safe to say, there is no American black dancer who has not been influenced by the Dunham Technique, unless he or she works entirely within a classical genre", and the Dunham Technique is still taught to anyone who studies modern dance.

The highly respected Dance magazine did a feature cover story on Dunham in August 2000 entitled "One-Woman Revolution." As Wendy Perron wrote, "Jazz dance, 'fusion,' and the search for our cultural identity all have their antecedents in Dunham's work as a dancer, choreographer, and anthropologist. She was the first American dancer to present indigenous forms on a concert stage, the first to sustain a black dance company.... She created and performed in works for stage, clubs, and Hollywood films; she started a school and a technique that continue to flourish; she fought unstintingly for racial justice."

Scholar of the arts Harold Cruse wrote in 1964: "Her early and lifelong search for meaning and artistic values for black people, as well as for all peoples, has motivated, created opportunities for, and launched careers for generations of young black artists ... Afro-American dance was usually in the avant-garde of modern dance ... Dunham's entire career spans the period of the emergence of Afro-American dance as a serious art."

Black writer, Arthur Todd, described her as "one of our national treasures." Regarding her impact and effect he wrote: "The rise of American Negro dance commenced ... when Katherine Dunham and her company skyrocketed into the Windsor Theater in New York, from Chicago in 1940, and made an indelible stamp on the dance world... Miss Dunham opened the doors that made possible the rapid upswing of this dance for the present generation." "What Dunham gave modern dance was a coherent lexicon of African and Caribbean styles of movement—a flexible torso and spine, articulated pelvis and isolation of the limbs, a polyrhythmic strategy of moving—which she integrated with techniques of ballet and modern dance." "Her mastery of body movement was considered 'phenomenal.' She was hailed for her smooth and fluent choreography and dominated a stage with what has been described as 'an unmitigating radiant force providing beauty with a feminine touch full of variety and nuance."

Richard Buckle, ballet historian and critic, wrote: "Her company of magnificent dancers and musicians ... met with the success it has and that herself as explorer, thinker, inventor, organizer, and dancer should have reached a place in the estimation of the world, has done more than a million pamphlets could for the service of her people."

"Dunham's European success led to considerable imitation of her work in European revues ... it is safe to say that the perspectives of concert-theatrical dance in Europe were profoundly affected by the performances of the Dunham troupe."

While in Europe, she also influenced hat styles on the continent as well as spring fashion collections, featuring the Dunham line and Caribbean Rhapsody, and the Chiroteque Française made a bronze cast of her feet for a museum of important personalities."

The Katherine Dunham Company became an incubator for many well known performers, including Archie Savage, Talley Beatty, Janet Collins, Lenwood Morris, Vanoye Aikens, Lucille Ellis, Pearl Reynolds, Camille Yarbrough, Lavinia Williams, and Tommy Gomez.

Alvin Ailey, who stated that he first became interested in dance as a professional career after having seen a performance of the Katherine Dunham Company as a young teenager of 14 in Los Angeles, called the Dunham Technique "the closest thing to a unified Afro-American dance existing."

For several years, Dunham's personal assistant and press promoter was Maya Deren, who later also became interested in Vodun and wrote The Divine Horseman: The Voodoo Gods of Haiti (1953). Deren is now considered to be a pioneer of independent American filmmaking. Dunham herself was quietly involved in both the Voodoo and Orisa communities of the Caribbean and the United States, in particular with the Lucumi tradition.

Not only did Dunham shed light on the cultural value of black dance, but she clearly contributed to changing perceptions of blacks in America by showing society that as a black woman, she could be an intelligent scholar, a beautiful dancer, and a skilled choreographer. As Julia Foulkes pointed out, "Dunham's path to success lay in making high art in the United States from African and Caribbean sources, capitalizing on a heritage of dance within the African Diaspora, and raising perceptions of African American capabilities."

Awards and honors

Over the years Katherine Dunham has received scores of special awards, including more than a dozen honorary doctorates from various American universities.

In 1971 she received the Heritage Award from the National Dance Association.

In 1979 at Carnegie Hall, she received the Albert Schweitzer Music Award "for a life's work dedicated to music and devoted to humanity."

In 1983 she was a recipient of one of the highest artistic awards in the United States, the Kennedy Center Honors.

In 1986 the American Anthropological Association gave her a Distinguished Service Award.

In 1987 she received the Samuel H. Scripps American Dance Festival Award, and was also inducted into the National Museum of Dance's Mr. & Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney Hall of Fame in Saratoga Springs, New York. She also received a Candace Award from the National Coalition of 100 Black Women.

In 1989 she was awarded a National Medal of Arts, an honor shared by only two other University of Chicago alumni, Saul Bellow and Philip Roth.

Dunham has her own star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame.

In 2000 she was named one of the first one hundred of "America's Irreplaceable Dance Treasures" by the Dance Heritage Coalition.

In 2002 Molefi Kete Asante included her in his book 100 Greatest African Americans.

In 2004 she received a Lifetime Achievement Award from Dance Teacher magazine.

In 2005, she was awarded "Outstanding Leadership in Dance Research" by the Congress on Research in Dance.

Wikipedia

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Free tix to DAVE CHAPPELLE, New Jazz Quartet, Sheila E, Jody Watley, George Clinton, and MORE at Yoshi's

Free tix to DAVE CHAPPELLE, New Jazz Quartet, Sheila E, Jody Watley, George Clinton, and MORE at Yoshi’s

7633 Sunkist Drive, Oakland CA 94605-3032 Phone (510) 394-4601 http://Ex-Why.com Aaron & Margaret Wallace Foundation http://Superstarmanagement.com Abdul-Jalil Honored in Port Au-Prince, Haiti and Miami, Fla. for Relief Missions to Haiti Join the Superstars Entertainment and Sports Network Abdul-Jalil’s Haas School of Business Profile Ziggs Profile of Abdul-Jalil Linked In Profile on…

View On WordPress

#“I Want Tickets!”#@amwft#@nowtruth#& Pain#occupyoakland#OWS#106th Ave#11 other musicians to form Zongo Junction#11th St#14th Ave#1972#20 year#24/7#25th season#4 Minutes#80′s#A & MWF#a best-seller#a blues-drenched gem that swings with dazzling aplomb#a commentary#a complaint against#a four-alarm fire#A girl I can love forever#a Harlem Renaissance Award#a holiday tradition#a huge success#a letter from me to my fans about what’s going on in my life#a lost art#a memorable concert#a modern nine-piece afrobeat band

0 notes

Text

SOUL

Jacqueline Perez

COM 105 Media and Society

FALL 2020

December 6, 2020

Blog post #5: Superhero Films: What should the future of this genre be?

SOUL

Alter ego: Shea Rincon J.D

Place of origin: The Bronx, New York

Abilities:

· Elite Level Marital Artist and hand to hand combat

· Master negotiation and persuasion skills

· Freak athlete

· Expert parkour practitioner

· Chess Grandmaster

· Gifted artist

Origin Story

Born on April 4th, 1974, SOUL’s secret identity is Shea Rincon. She is the founder of F.B.R. (Foundations Built Right). FBR is a nonprofit community group that provides opportunities in impoverished, lower socioeconomic, high crime neighborhoods in New York City. Born to a Haitian mother and a Puerto Rican father, Shea’s parents were community activist and renowned jazz musicians. They would actively participate in civil rights movements during the sixties and seventies. Unfortunately, due to the drug epidemic terrorizing New York City during the eighties, Shea’s parents fell victim to the devastating ripple sending its shock waves all throughout. Both her mother and father succumbed to drugs, by way of overdosing. This tragedy happening when Shea was just two years old, put her in custody of child protective services. She would bounce around foster care, residential programs, and group homes until the age of sixteen. At age eight, in 1982 The Bronx was filled with abandoned buildings and rubble from those very same buildings being burnt to the ground, you could easily find children at play in these buildings and surrounding rubble. In these buildings, she would develop and enhance her skills, jumping from floor to floor, roof top to roof top. This would help her tremendously with her love of graffiti. She would eventually take control of the paint can herself, tagging under the moniker of “SOUL 1”. During this time to get away from the constant shootings, robberies, gangs, and drug abuse, when she was not roaming around, doing graffiti or enhancing her parkour skills, she would constantly go to the library. Shea would become an avid reader and befriended an elderly man named Don Campos who taught her how to play chess, box, and educated her on life. During the day she would roam around practicing her art, parkour, playing chess for money and reading. In 1990 at 16 she became tired of her living circumstances within group homes and decided she would take control of her destiny and look after herself. She supported herself by going downtown to New York City parks and playing people at chess for money. She was able to rent out an apartment in a brownstone Don Campos owned. After about eight years of learning how to box from Don Campos, SOUL joined a martial arts gym to learn other fighting styles. From age eight to twenty-one, her life was constantly repeating the activities of chess, graffiti, training how to fight, and reading for hours upon hours. During a tragic home invasion, Don Campos, the only parental figure she ever truly acknowledged was murdered. The city’s homicide rate was at an all-time high, which hindered the police from ever finding the criminals behind the murder. Yet another tragedy, in the tragedy that was SOUL’s life. Becoming very cynical, SOUL went in search for the criminals. This pursuit forced her be tactful about how she was going to carry out this mission. She ultimately came up with a disguise to protect her identity. Along the way she had to gain information from gang members, drug dealers, and vicious people. She would search for active crimes, stop them, and question the criminals for information about the Don Campos murder. After obtaining the information she needed she would tie up the criminals, call the police and tag her moniker, “SOUL 1”. SOUL would go on to find the murders of Don Campos, bringing them to justice. This would be just the start of her crime fighting life, as she would actively go on to help solve crimes and stop criminals for many years to come. The name SOUL was well known throughout the city and praised by police groups and politicians.

Present Story

Standing at 5’9 and 150 pounds of pure muscle, SOUL continues to hone the skills that made her a hero in the first place. However, when she is not SOUL, she is just Shea. She operates non-profit F.B.R. (Foundations Built Right) and is well known for community activism and the mentorship she provides for the younger folk in the city. After solving the murder of her parental figure, Don Campos, SOUL went and got her G.E.D. She later went on to graduate from college, eventually attending Bronx Community College, New York University, and Colombia Law, all, respectively. This allowed her to actively advocate for the rights of people who cannot correctly advocate for themselves. When not fighting for the rights of others, SOUL is actively fighting crime and still tagging her moniker, “SOUL 1”. She uses this as a calling card and to warn others to lead a life away from crime. SOUL loves to spray beautiful murals all over the city, expressing thoughts on freedom, love, and peace. SOUL most resembles Batman from the DC UNIVERSE in this respect. Batman like SOUL were both orphans who possess no real superpowers like the ability to fly or teleport. They both possess the ability to work hard and use their environment to succeed. SOUL graduated from lower-level criminals, and currently fights criminal enterprises, and corrupt politicians. SOUL works in conjunction with the New York City Police Department and other federal departments, like the FBI and DEA to stop the flow of drugs coming into the city. This has presented incredible difficulty to SOUL’s plight. This due to the constant corruption within the city’s institutions. SOUL’s greatest challenge ever came from a woman named Throne Rayburn. Rayburn was mayor or New York City and appeared to support the same ideals that SOUL had. This was all an elaborate stunt however, as Rayburn was responsible for many corrupt and shady practices going on in the city behind the scenes and out of the public view. Mayor Rayburn also had a personal vengeance to destroy SOUL’s public image. This is because SOUL posed a threat to Mayor Rayburn’s success. SOUL eventually uncovered a mind-blowing scandal involving cartels, and other nations, working with Rayburn to bring in drugs. SOUL worked diligently to stop the flow of incoming drugs, going as far as going to the countries where the drugs were and getting rid of criminals responsible. Soon through, SOUL realized that this feat was bigger than what she would be able to handle on her own and with just capturing criminals. SOUL would go on to ask a Dave Hand, a journalist for help in showing Mayor Rayburns true nature. She would consistently supply Hand with information about the corruption of Mayor Rayburn. Unfortunately, Hand betrayed SOUL and found her identity. Hand would go on to expose this to Mayor Rayburn, later killed Hand so that he would not reveal SOUL’s identity to the greater public. At this point Rayburn had all the firepower she needed to make SOUL’s life miserable by means of politics. First, she was able to frame SOUL by getting her disbarred as a lawyer, framing her for the misuse of funds for her non-profit. Rayburn then proceeded to use criminals to burn down all of SOUL’s community F.B.R. locations. SOUL being of tenacious spirit and character realized that she needed to leave the city to escape constant police investigations and news articles assassinating her character by leaving the city. She flew to her biological mother’s home country, Haiti, and spent time there to figure what her next move would have to be. During this whole time, Mayor Rayburn continued to increase the flow of drugs and corruption, knowing that SOUL was out of the picture. Meanwhile, the whole of New York City was asking where is SOUL? The time away from New York, was much needed for SOUL. She was able to gather her thoughts and connect with her roots. She visited many important revolutionary sites in Haiti and became inspired again for fighting the fight against evil and wrongdoing. She realized the only way she could beat Mayor Rayburn was by revealing her identity and to tell her story to the FBI and the public. The last thing Mayor Rayburn would ever expect SOUL to do. SOUL told a federal agent she trusted by the name of Richard Gomez, her story and about how she wants the public to know who she is. Agent Gomez advised against this, but SOUL reiterated that it would not matter because if she did not reveal who she was, Mayor Rayburn would surely do so. Agent Gomez and SOUL agreed that they would conduct an investigation and use SOUL as a key witness in bringing down Rayburn. For the time being Agent Gomez told SOUL to stay in Haiti. After a year of investigating, the FBI indicted Rayburn on counts of murder, conspiracy, and drug trafficking. The star witness was SOUL, who was able to reveal her story to the public. Throne Rayburn quickly accepted a plea deal and was sentenced to only 10 years in federal prison if she agreed to cooperate and be a witness.

Future

The indictment and testimony of Throne Rayburn changed the landscape of the city. The city instantly became a much more peaceful and safer place. Not 100%, but a substantial changed was made. SOUL was celebrated and casted into the national spotlight as a heroine. She avoided the spotlight and moved back to Haiti. A statue sits in the middle of Central Park as a commemoration for all that she had done for the city. The CUNY Law School was renamed The Shea “Soul” Rincon Law School. She inspired many and sacrificed so much to make the city a better place to live for others. She donates all the money her organization receives and continues to receive to lower socioeconomic locations all over the world. She is considered to be a true civic leader and inspires so many.

0 notes

Text

Glenn Ligon

Happy birthday to Glenn Ligon.

https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Glenn_Ligon

Glenn Ligon (born January 1, 1960) is an American conceptual artist whose work explores race, language, desire, sexuality, and identity. Ligon engages in intertextuality with other works from the visual arts, literature, and history, as well as his own life. He is noted as one of the originators of the term Post-Blackness.

Early life and career

He was born in 1960 in the Bronx. At the age of 7, his divorced, working-class parents got a scholarship for him and his brother to attend Walden School, a high-profile progressive private school on Manhattan's Upper West Side. Ligon graduated from Wesleyan University with a B.A. in 1982. After graduating, he worked as a proofreader for a law firm, while in his spare time he painted in the abstract Expressionist style of Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock. In 1985, he participated in the Whitney Museum of American Art's Independent Study Program. He currently lives and works in New York City.

Work

Ligon works in multiple media, including painting, neon, video, photography, and digital media such as Adobe Flash for his work Annotations. Ligon's work is greatly informed by his experiences as an African American and as a gay man living in the United States.

Painting

Although Ligon's work spans sculptures, prints, drawings, mixed media and even neon signs, painting remains a core activity. His paintings incorporate literary fragments, jokes, and evocative quotes from a selection of authors, which he stencils directly onto the canvas by hand. In 1989, he mounted his first solo show, "How It Feels to Be Colored Me," in Brooklyn. This show established Ligon's reputation for creating large, text-based paintings in which a phrase chosen from literature or other sources is repeated over and over, eventually dissipating into murk. Untitled (I Am a Man) (1988), a reinterpretation of the signs carried during the Memphis Sanitation Strike in 1968 — made famous by Ernest Withers’s photographs of the march —, is the first example of his use of text.

Ligon gained prominence in the early 1990s along with a generation of artists like Lorna Simpson, Gary Simmons, and Janine Antoni. In 1993, Ligon began the first of three series of gold-colored paintings based on Richard Pryor's groundbreaking stand-up comedy routines from the 1970s. The scatological and racially charged jokes Ligon depicts speak in the vernacular language of the street and reveal a complex and nuanced vision of black culture.

In A Feast of Scraps (1994–98), he inserted pornographic and stereotypical photographs of black men, complete with invented captions ("mother knew," "I fell out" "It's a process") into albums of family snapshots including graduation photographs, vacation snapshots, pictures of baby showers, birthday celebrations, and baptisms, some of which include the artist's own family. Like almost all of Ligon's art, this project draws out the secret histories and submerged meanings of inherited texts and images.

For Notes on the Margin of the Black Book (1991–93), Ligon separately framed 91 erotic photographs of black males cut from Robert Mapplethorpe's 1988 "Black Book," installing them in two horizontal rows. Between them are two more rows of small framed typed texts, 78 comments on sexuality, race, AIDS, art and the politically inflamed controversy over Mapplethorpe's work launched by then-Texas Congressman Dick Armey.

Another series of large paintings was based on children's interpretations of 1970s black-history coloring books.

Installation art

In 1994, the art installation To Disembark was shown at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C. The title alludes to the title of a book of poetry by Gwendolyn Brooks. "To Disembark" functions in both works to evoke the recognition that African Americans are still coping with the remnants of slavery and its ongoing manifestation in racism. In one part of the installation, Ligon created a series of packing crates modeled on the one described by ex-slave Henry "Box" Brown in his "Narrative of Henry Box Brown who escaped from Slavery Enclosed in a Box 3 Feet Long and 2 Wide." Each crate played a different sound, such as a heartbeat, a spiritual, or contemporary rap music. Around each box, the artist placed posters in which he characterized himself, in words and period images, as a runaway slave in the style of 19th century broadsheets circulated to advertise for the return of fugitive slaves. In another part of the exhibition, Ligon stenciled four quotes from a Zora Neale Hurston essay, "how it feels to be colored me," directly on the walls: "I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background," "I remember the very day that I became colored," "I am not tragically colored," and "I do not always feel colored." Ligon found Hurston's writing illuminating because she explores the idea of race as a concept that is structured by context rather than essence.

Neon works

Since 2005, Ligon has made neon works. Warm Broad Glow (2005), Ligon’s first exploration in neon, uses a fragment of text from Three Lives, the 1909 novel by American author Gertrude Stein. Ligon rendered the words “negro sunshine” in warm white neon, the letters of which were then painted black on the front. In 2008, the piece was selected to participate in the Renaissance Society's group exhibit, "Black Is, Black Ain't"., and appeared on the Whitney Museum’s facade in 2011. Other neon works are derived from neon sculptures by Bruce Nauman; One Live and Die (2006) stems from Nauman’s 100 Live and Die (1984), for example.

Film

In 2009, Ligon completed short film based on Thomas Edison's 1903 silent film Uncle Tom's Cabin. Playing the character of Tom, Ligon had himself filmed re-creating the last scene of Edison's movie, which also provided his film's title: "The Death of Tom." But the film was incorrectly loaded in the hand-crank camera that the artist used so no imagery appeared on film. Embracing this apparent failure, Ligon decided to show his film as an abstract progression of lights and darks with a narrative suggested by the score composed and played by jazz musician Jason Moran.

Exhibitions

Ligon's work has been the subject of exhibitions throughout the United States and Europe. Recent solo exhibition include the Studio Museum in Harlem, New York (2001); the Kunstverein München, Germany (2001), the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis (2000); the St. Louis Art Museum (2000); the Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia (1998); and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (1996). A first survey of Ligon's work opened at The Power Plant in Toronto in June 2005 and traveled to the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh; Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston; Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus; Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery in Vancouver, and the Mudam in Luxembourg. The first comprehensive mid-career retrospective devoted to Ligon's work was held at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth in 2011. Group shows in which Ligon has participated include the Whitney Biennial (1991 and 1993), Biennale of Sydney (1996), Venice Biennale (1997), Kwangju Biennale (2000), and documenta 11 (2002).

In 2013, Ligon started writing letters to artists whose work had made an impression on him in his life, asking if he could borrow that particular work for an exhibition. While some of the letters were sent to living artists, others are letters that Ligon would have sent those of the past, including Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Andy Warhol and Felix Gonzalez-Torres. The resulting show at Nottingham Contemporary in 2015 featured work by 45 different artists from Warhol to Steve McQueen, as well as Black Panther Party posters, press shots and footage from the Birmingham riot of 1963.

Collections

Ligon's work is represented in many public collections including the Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia; the Guggenheim Museum, New York; the Tate Modern, London; the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; the Blanton Museum of Art, Austin; the Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford; the Warwick Arts Centre, Coventry; and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. In 2012, the National Gallery of Art in Washington bought the painting Untitled (I Am a Man) (1988).

In 2012, Ligon was commissioned to create the first site-specific artwork for the New School's University Center building, designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, on the corner of 14th Street and Fifth Avenue in Greenwich Village. The work will feature about 400 feet of text from Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass rendered in pink neon lights, running around the top of a wall in the center’s first-floor café.

Recognition

In 2005, Ligon won an Alphonse Fletcher Foundation Fellowship for his art work. In 2006 he was awarded the Skowhegan Medal for Painting. In 2010, he won a United States Artists Fellow award.

In 2009, President Barack Obama added Ligon's 1992 Black Like Me No. 2, on loan from the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, to the White House collection, where it was installed in the President's private living quarters. The text in the selected painting is from John Howard Griffin's 1961 memoir Black Like Me, the account of a white man's experiences traveling through the South after he had his skin artificially darkened. The words "All traces of the Griffin I had been were wiped from existence" are repeated in capital letters that progressively overlap until they coalesce as a field of black paint. Art critic Jerry Saltz called this work a "black-and-white beauty."

Art market

On the occasion of Ben Stiller and David Zwirner’s "Artists For Haiti" charity auction at Christie's in 2011, Jennifer Aniston set a record prize for Glenn Ligon's work by purchasing his Stranger #44 (2011). At $450,000, Aniston beat Ligon’s previous record of $434,500 for Invisible Man (Two Views) (1991), realized at Sotheby's in September 2010. Untitled #1 (Second Version) (1990), a painting in which the words "I Feel Most Colored When I Am Thrown Against a Sharp White Background" repeat again and again, sold for $2.6 million at Christie' New York in 2014.

Ligon is represented by Regen Projects in Los Angeles; Luhring Augustine in New York; and Thomas Dane Gallery in London.

Personal life

According to the Federal Election Commission (FEC), Ligon donated $30,000 to the presidential campaign of Hillary Clinton in September 2016.

0 notes

Note

So why are you named vodou/hoodoo when you're white?

Hello! I figured this would come up at some point so I’ll just go ahead and address this.

I am white, and I’m interested in Vodou, hoodoo, and other religious and magic systems of the African Diaspora. When I started this blog a few years ago I started diving and setting up altars, reading up on it etc. I felt it resonated with me in a way that Wicca and some other neo-pagan practices never quite hit and I was very excited. However, I started to realize that, with Vodou in particular, that this was a form of cultural appropriation. So, I decided not to ‘dabble’ I guess is the word. I came across very well thought out arguments against ‘solitary Vodou’ and started to understand that Vodou is a semi-closed religion that requires initiation and an appropriate community context. I respectfully retired what altars I’d set up.

I now approach my interest from an academic and anthropological perspective. I want to pursue my PhD in anthropology some day, and my primary area of research is in how New World (Western Hemisphere) spiritual and religious practices developed and continue to this day, and how these cultural practices influence oppressed communities to be resilient in the face of hegemonic white culture. For example, Vodou is often villainized in American culture and is often ‘blamed’ for Haiti’s “backwardness” and poor economy. I want to research how Vodou could be a source of strength and identity and resilience for Haitians. If we can dispell these myths, we can disarm harmful ideas that are used as excuses for treating other people as less than humans.

African Diaspora religions and spiritual practices should be respected and appreciated, and the contributions to our larger cultural context should be acknowledged and celebrated (i.e. the links between hoodoo and blues music, and between blues, jazz, rock n roll changed American music).

As for your question about hoodoo, this is a gray area for me. Can/should white people practice or be involved in hoodoo? Honestly, I don’t know. I’ve seen people argue, convincingly, yes/no/maybe on this subject. Is hoodoo a closed religion like Haitian Vodou or is it a system of folk Southern folk magic? Both? There are some similarities to the distinctions between Wicca (religion) and witchcraft (an occult magic system that can be practiced with/independent of religion). There is no doubt that African American people developed the practices that make up hoodoo, rootwork, conjure, ect. and that many of these practices are rooted in religious and spiritual practices from various African religions. But it’s also important to note how hoodoo developed in the context of the American South: there’s elements of Native American culture, Protestant and Catholic Christianity, Jewish mysticism and Kabbalah, using the Bible as a spell book... hoodoo is a blend of cultural practices based on a certain historical cultural context, the American South during and after slavery. There’s also Scotch-Irish elements as well, and Appalachian influence. That is -not- to say that white people ‘created’ hoodoo and are therefore some how entitled to practicing it. What it does say is that hoodoo wasn’t developed in a vacuum. Working with ancestors poses further questions. I don’t know the answers. I’m interested in hoodoo because I’m fascinated with the melting pot of cultures in the American South. I like the practicality of using what you have simple ingredients to meet your needs. It’s down to earth in a way that feels -real-. I’ve done some hoodoo-inspiried workings that worked for me.

As for this blog and why I call it Paganvoodoohoodoo, I wanted this to be a resource. At first, it was just a reference for myself, snippets I found interesting and sources to investigate further in the future. I identify as a Pagan witch who works with Hecate and a few saints introduced to me as I looked into African Diaspora religions and spiritual practices. As I gain followers, I wanted to pass along info that my followers would find useful and meaningful. If I see Haitian art depicting the lwa, I reblog it because I appreciate it for art and because a follower of this blog may also appreciate it or is a Voudisant. If I see a hoodoo style spell/working or curse and I think someone will find it perfect for their needs, I pass it on. I want to share these posts because someone else looking to reclaim or understand their own heritage may find something that’s hard to find somewhere else. Hell, I once reblogged a post about makeup foundation for darker skin because I know it’s really hard to find decent makeup for PoC.

I’m not, and never will be, an expert in Vodou or hoodoo. I’m trying to help others have access to valuable cultural knowledge. I know as a white person I live in a society with privilege. I want to contribute, in whatever small ways I can, to change things for the better.

I hope this doesn’t come off preachy or anything. I’m better at talking about it in person. I’m very open to discussion. If there’s something here you agree or disagree with, please talk with me. Or not. No body owes me anything. If you read this and decide to unfollow I wish you the best.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

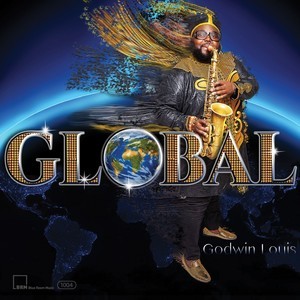

USA/HAITI: Godwin Louis Explores the Worldwide Impact of Afro-Caribbean Sounds and Concepts on Music and Takes them Global

Godwin Louis Explores the Worldwide Impact of Afro-Caribbean Sounds and Concepts on Music and Takes them Global

Saxophonist Godwin Louis had an epiphany when he came to New Orleans to study at the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz. He explored the city’s music--and kept getting an eerie sense of familiarity. “My mother and father are from Haiti, and though I was born in the States, I lived in Port-au-Prince for a few years in the 1990s,” recounts Louis. “When I moved to New Orleans, I felt that similarity everywhere, in the presence of Catholicism, the funeral marches, the second-line culture, the spiritual traditions tied to vodoun. I said, this is incredible. Where does this similarity come from?”

The answers turned out to be Global (release: Febuary 22, 2019), Louis’ first major release of his compositions and work as a band leader. Louis discovered the impact of Haitians on the music of New Orleans, arguably the musical heart of the US, and with it a history of Haitian presence going back to the French Colonial and Haitian Revolutionary period. Yet as Louis dug into the past, his understanding and musical vision expanded geographically and sonicly, as DNA tests led him to West and Central Africa (“Nago-Kongo”), Brazil, tiny Pacific islands--the entire global filigree of Afro-diasporic peoples and their art.

The resulting double-album of original compositions (with one anthemic concluding piece by composer Hermeto Pascoal) plumbs the past while remaining steadily grounded in contemporary and exploratory musical practices, that improvisatory, ever-fresh edge of jazz. A seasoned sideman--Louis’ touring history reads like a who’s who of jazz and pop--Louis felt it was time to bring his discoveries, in breathtakingly intricate and skillfully rendered form, to the world.

“My travels and studies let me fully explore and find this musical sound dedicated to the diaspora that you hear on Global,” says Louis. “The world is way more connected than we think. We’ve all heard of the Transatlantic trade slave and its tragedies and horrors, but so much came out of it and formed global culture, so much that’s rarely highlighted. You can feel it intensely in places like Santiago de Cuba, Bahia in Brazil, New Orleans, in L’artibonite, Haiti. The musical sound that came from those places has gone global, and it’s all filtered into pop culture. That’s where I started.”

Born in Harlem, Louis remembers encountering the beauties of jazz via his guitarist uncle, Robert “Magic” Saint Fleur. He marveled at his uncle’s ability to improvise and wanted to know his secret. “I was really drawn to that element of improvisation,” recalls Louis. “I would hear him riff off a song, and it seemed like the most incredible thing, how he came up with all these beautiful melodies on the spot. It showcased such knowledge of the songs and total mastery of the instrument.” His uncle encouraged him, then turned him on to Charlie Parker, and Louis was hooked.

He studied at Berklee and made an admirable name for himself among jazz’s creme de la creme. Though relatively young, Louis has already toured, performed, and recorded with Herbie Hancock, Clark Terry, Roger Dickerson, Ron Carter, Al Foster, Jack Dejohnette, Jimmy Heath, Billy Preston, Patti Labelle, Toni Braxton, Babyface, Madonna, Gloria Estefan, Barry Harris, Howard Shore, David Baker, Mulatu Astakte, Mahmoud Ahmed, Wynton Marsalis, and Terence Blanchard, among others, seeing a great swath of Africa, Asia, and Europe in the bargain.

As Louis developed his own style, where gospel and traditional Haitian and West and Central African songs, avant arrangements and grounded grooves collide, he discovered new concepts in African-heritage musical thought that enriched his jazz foundations. Fellow musicians in Mali, for example, based melodic phrases on underlying texts, not on arbitrary numbers of beats or bars.“Because it’s all based on the words, there's no common tempo,” explains Louis. “When the phrase is done, it’s done and then you move on. I decided to experiment with approaching notes the same way. An idea can keep on going. In general, Global questions tradition: Why should the form be one way and not another? If the idea isn’t done yet, it goes on, even when another idea comes. The melody is king in that approach.” The resulting feel is polyphonous, many different voices and perspectives chiming in and overlapping.

The overlap fascinates Louis and inspired many of Global’s pieces. He reveals into how European sacred music seeped into an Afro-diasporic melody found around the Atlantic, rich with triple meter. (“Four Essential Prayers of Guinea”) And how, in counterpoint, African instruments can inform Protestant hymns, despite centuries of church animosity toward West African sounds and forms. (“Bondye Ede-n”) He looks at narrative threads that unite the lyrical forms of Afro-Caribbean and Afro-South American romance (“Present” featuring Cuban singer Xiomara Laugart), and the playing techniques and moods that unite the Francophone cultures of the Caribbean (“Siwèl”).

Yet the wide-ranging journeys remain rooted in Louis’ personal experience as a person with a multilayered heritage and full awareness of past and present struggles. As the composer noted regarding the album’s title suite (“Global, Parts I and II”): “This is about my traveling experiences all over the world. I’ve been to 100 countries as of now. I have so many stories, some sad, some triumphant. So did our ancestors,” Louis reflects. “Sonically, I wanted to pay homage to some of our lesser-known ancestors that contributed to the development of music in Europe. People like Joseph Boulogne, Chevaliers De Saint-Georges who was a brilliant composer during the classical era. Overall, Global is the history of music and culture in the Americas. Cultures that came from Africa, met with indigenous aestheticism, and were refined or rarefied via colonialism, as a result changing the course of music history and culture worldwide.”

Links

Facebook

Instagram

Website

Contact

Publicist

Ron Kadish

8121-339-1195 X 202

via Blogger https://ift.tt/2Tjq7pl

0 notes

Video

youtube

Salilento / Afro-Haitian Experimental Orchestra (Pan African Music, 2016)

Seven-and-a-half thousand kilometres of cold ocean separate West Africa from Haiti. But music can cover that distance in a heartbeat, crossing the Atlantic to reunite the rhythms and religion of people torn from their homes to be sold into slavery on the Caribbean island. And on its self-titled album, the Afro-Haitian Experimental Orchestra honours those ghosts of the past even as it walks steadfastly and hopefully into the future.