#foreign policy realism

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

This hangs some details on a rant I was going to release after they buried him in the cold, cold ground. (It's been long enough I'm starting to wonder if some patriot at Arlington is making excuses not to take him.)

"Foreign policy realism" turns out to not be realistic after all.

Henry Kissinger's obituary in the NYT wasn't half the fawning apologist trainwreck we all expected it to be, but they did bend over backwards to present his side of the argument, what he was thinking all those decades, based on interviews with many of his friends, co-workers, and his students at Harvard:

Kissinger's WWII experiences convinced him that America was the most moral and trustworthy country in the world. And, he reasoned, that is why the President of the United States should be able to give an order to anybody in the world, in any country, and reasonably expect to be obeyed. And since the evil countries won't want to acknowledge the American president as the Leader of the World, not only is he morally allowed to do whatever it takes to get his way, he's morally required to do so.

Which was what he was thinking when he taught "foreign policy realism" both in the halls of power and in the halls of the Ivy League schools, which meant that, given a range of options, he was always, every time, on the side that would result in the most innocent civilian deaths. The more innocent civilian deaths there are, the faster other countries will have to do the right and moral thing: accept the moral superiority and moral authority of the President of the United States.

To describe this as merely incoherent is to fail to notice the most idiotic part of it:

Every time a US president or secretary of state or CIA covert operations director, on Kissinger's advice, murdered tens or hundreds of thousands of innocent civilians, every single time, the result was the opposite of what Kissinger predicted it would be. At best, we replaced bad governments with worse. At worst, you can trace the origin story of every single one of the worst terrorist groups in the world to the results of Kissingerist "realism." And, even more appallingly to me, ...

Kissinger gave this same stupid, evil advice every few years for sixty years without learning a thing from his failures. Sixty years' worth of US leadership followed his bad advice and never even paid any attention to his track record. It's the same old disgusting cognitive bias over and over again: it takes no evidence to believe what you already want to believe, and no amount of evidence can disprove something once you've already made up your mind.

It's why, among other things, there's never any consequence to being demonstrably wrong in politics or elite journalism: if you were telling people in power that their darkest impulses are good and right, and it turns out you were wrong, that can't possibly be your fault, because "nobody could possibly have known" it wouldn't work, no "reasonable person" would have thought you were wrong. Nor can it be the fault of people who were persuaded by his "foreign policy realism" because "everybody knew" he was always right, knew it so confidently they never looked back and checked.

So I apologize to Henry Kissinger's family and friends for not letting them grieve, but if they're going to keep postponing the funeral service, I can't stay silent forever. Henry Kissinger was a monster, because he made the people he touched even more monstrous than they already were, and no matter how early he had died, I would have wished it had been sooner, and may the hallowed ground of Arlington spit out his evil corpse, and may his ghost spend eternity in a customized torture pit in the fiery depths of Tartarus as a warning to the next 100 generations that his kind of "realism" isn't just evil, that being a "foreign policy realist" isn't just monstrous, but it's also demonstrably, historically, really, really stupid. Psychopathic callousness isn't "realism." It doesn't even WORK.

VOR: Henry Kissinger

Ugh, HUGELY overrated, Bismark has nothing on him. What, truly are his accomplishments? Oh, rapprochement with China? You mean the country that had just experienced a huge split with the Soviet Union, to the point where they were scared of military conflict, that was simultaneously backing North Vietnam in a war against the US? And so we opened doors to them and gave them literally everything they asked for, hanging Taiwan out to dry, and in return got absolutely nothing; China's aid to North Vietnam actually *increased* the year after? The corpse of a roadkill dog could have done that.

The "cease fire" with North Vietnam? That's just losing with coat of paint to poorly cover the shame! At least he had the self-respect to try to return his Nobel Peace prize. Ho Chi Minh handed him his ass on a platter and somehow that is a win on his ledger.

Accelerating arms sales to the Shah of Iran in order to back separatist fighters in Iraq? Whoops! Wow, that uh, wow what a call there. Really picked the right side.

Coup against Allende in Chile? That went well! Not to mention...he didn't. Chile coup'd Chile, Allende was a complete disaster imploding the country's economy. The Chilean military asked for permission as like a token gesture, we gave them support that didn't matter. Its like taking credit for a sports team win because you bought box seats, except at this game they dropped the opposing team's family out of a helicopter headfirst onto the pitch.

All the SALT treaty stuff started under Johnson, he continued it which is fine but is VORcel stuff. His grand "pivot to Europe" was trying to link trade policy to increases in defense spending from European partners...which didn't happen. They didn't increase them. We gave them trade deals anyway. Its fucking Trump without the memes.

On March 1, 1973, Kissinger stated, "The emigration of Jews from the Soviet Union is not an objective of American foreign policy, and if they put Jews into gas chambers in the Soviet Union, it is not an American concern. Maybe a humanitarian concern.

Awww "I'm such a cool little edgy boy, look at me and my joke about the Holocaust when discussing systemic discrimination against Jews the Soviet Union, surely this will somehow score me Realpolitik points on the Big Board that I can cash in for prize money while shedding America's moral legitimacy because it makes my dick hard."

He is the academic definition of style over substance, snottily walking from fuck-up to disaster to status-quo free ride and putting a pithy quote about The Nature of Power over it to pretend he had any to begin with. Hurry up and die already so I can stop running into you haggling over hostess tips at overpriced Georgetown restaurants.

F-

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Sometimes, as much as I love internet communities and spaces, I really think a lot of people have spent so much time in sanitized, morally pure echo chambers that they lose sight of realism and life outside the internet.

I live in Alabama. My fiancée and I cannot hold hands down the street without fear of homophobic assholes. We have an abortion ban with no exceptions for rape or incest. We are one of the poorest states in the US with some of the lowest scores on metrics related to quality of life, including maternal mortality, healthcare, education, and violence. It’s not a coincidence that we are also one of the most red, one of the most Republican states in the Union. In 2017 the UN said the conditions in Alabama are similar to those in a third-world country.

Trump gave a voice to the most violently racist, sexist, xenophobic groups of people who, unfortunately for most of us in the Southern U.S., run our states and have only grown more powerful since his rise to power. The Deep South powers MAGA, and we all suffer for it.

We have no protections if they don’t come from the federal government.

I know people are suffering internationally and my heart is with them. However, this election is not just about foreign policy - we have millions of Americans right here at home living in danger, living in areas where they have been completely abandoned by their local leaders. We need this win.

No candidate is perfect, but for the first time in my voting lifetime I’m excited to vote. I’m excited for the Kamala Harris/Tim Walz ticket because they are addressing the issues close to home. They’re advocating for education as the ticket to a better life, but without the crippling student debt. They’re advocating for the right to love who you love without fear and with pride. Kamala has always been pro-LGBT+ and so has Tim. Again, if you’re queer in the South, we don’t have support unless it comes from the federal government, and we absolutely will not have support if the Republicans regain the White House.

Kamala speaks in length about re-entry programs to reduce recidivism and help people who have been arrested and imprisoned regain their lives. Tim Walz supported restoring voting rights to felons. In the South, you know who comprise the majority of felons? Members of minorities. It’s one of the major tools of systemic racism and mass disenfranchisement, and arguably the modern face of slavery (there are some fantastic documentaries and books that explain the connection between the post-Reconstruction South and the disproportionate rates of imprisonment for BIPOC). Having candidates who recognize this and want to restore the freedom and rights to people who have come into contact with the criminal justice system? And keep them from having to go to prison in the first place? That’s refreshing. That’s exciting.

I would *love* to live in a country where women’s rights are respected, where LGBT+ rights and protections are a given, where we treat former criminals and individuals experiencing mental health crises with respect and dignity. I would *love* to live in a country where education is free of religious interference and each and every citizen is entitled to a fair start and equal opportunities.

But I don’t live in that country. Millions and millions of Americans find their rights and freedoms up for debate and on the ballot.

Project 2025 poses the largest threat to the future of our democracy as we know it. We are being called to fight for the future of our country.

We have to put on our oxygen masks first before we can help others.

You don’t have moral purity when you wash your hands of the millions of us who are still fighting for own freedoms right here.

The reality is that a presidential candidate is a best fit, and not a perfect fit. But comparatively speaking? Kamala is pretty damn close.

#us politics#kamala harris#vote kamala#vote blue#don’t forget about the southern states please#we’re still here

3K notes

·

View notes

Note

i only learned recently from a friend's who much more comic literate than I that magneto's backstory as an Auschwitz survivor wasnt planned from the start, which surprised me since it seemed to me a really integral part of his character. anyway, twofold question: how common is it to see capes with backstories tied to very specific historical events, and, as time inevitably passes and real world survivors of those events pass, how do they justify having their characters still alive and kicking? (stay safe on your mountaintop friend)

Depending on how wide you cast the net, this is a pretty big list! There are a lot of comics who's characters cutting-edge ripped-from-the-headlines origin later became a very specific historical event, or at least Of A Specific Moment, in a way the writers had no reason to anticipate the franchise would run long enough to have happen. But to shed pedantry and hone in on some specific ones;

The big one, of course, is Captain America. Superficially Cap's contemporary origin comes with a baked-in means of him making it to the present day- he gets stuck in the ice and then gets unthawed. The fly in the ointment, though, is when he unthaws. When they first brought him back into rotation in 1964, his stint in the ice was only around 20 years; long enough for there to be a significant culture shock, but not long enough that his entire social circle was dead or even culturally sidelined. Nick Fury is still around and kicking ass as a zeitgeist-appropriate 60s superspy. But the further the sliding timeline hauls forward his implicit date of release, the more it changes the tone and tenor of the resulting story. Losing twenty years is different from losing fifty years (as was the case in The Ultimates, where he very explicitly comes back during the Bush years as part of the book's commentary on The War On Terror) and those will both be way different from when we inevitably hit the point where he's lost 100 years and he's the cultural equivalent of a Civil War Vet or something. There's strength to all of those stories but they're undeniably different.

Iron Man's origin was originally explicitly tied to the Vietnam war; he was captured by a detachment of "Red Guerillas" while consulting for the US military and the South Vietnamese government. Unfortunately U.S. foreign policy to this day has prevented this from ever becoming an unresolvable storytelling issue.

The Fantastic Four are a case where their origin was intimately tied to the space race; their untested, cutcorner spaceflight was expressly an attempt to show up the Russians. The extremely specific political context of their test flight is something that sort of gets brushed off; the Ultimate incarnation (written by Warren Ellis) threaded this needle deftly by having the accident be a dimensional expedition instead, circa the early 2000s. I'm not actually sure how the urgency of their test flight is currently contextualized in 616 continuity. Anyone got their finger on that pulse?

The Punisher was also originally a Vietnam vet- but through the jaded cynical lens of the 1980s rather than the straightforwardly peppy and jingoistic lens that defined Iron Man's debut in the 60s. Current continuities I believe have mostly bitten the bullet and updated his origin to the invasion of Afghanistan. However, an interesting decision in the Garth Ennis-spearheaded Punisher MAX continuity of the early 2000s- where Punisher is literally the only costumed vigilante- is that they bit the bullet and posited a version of Frank Castle who really has been killing criminals nonstop since shortly after his return from Vietnam in the 70s, a man well into his 60s who's survivability and efficacy at killing are edging up against the boundaries of magical realism.

Hulk I feel sort of deserves a mention here- he's in a sort of twilight zone on this issue, as there was, uh, a pretty goddamn specific political context in which the Army was having him make them a new kind of bomb, but you can haul that forward in the timeline without complete destruction of suspension of disbelief. Pretty soon it'll be downright topical again.

To circle back around to The X-Men, Claremont introduced a lot of historical specificity with the ANAD lineup. Off the top of my head, Colossus was explicitly a USSR partisan (updated to a gangster forced into crime to survive in the mismanaged chaos of the USSR's collapse in the Ultimate Universe) and Storm was orphaned by a French bombing during the Suez War. More to the point, the timing was such that Magneto, in his upper-middle age, had a pretty strongly defined timeline vis a vis his ideological development vs Xavier; child during the holocaust, Nazi hunter who eventually rifts with Xavier during the mid-to-late 60s, and then the two of them spend their years marshalling their respective resources before coming to blows during the quote-unquote "Age of Heroes," whatever the timeline looked like for that in the 80s. And it was a timeline that held together pretty damn well in the 80s, but it's gotten increasingly awkward as time's gone on. The Fox films completely gave up on having it make sense, near as I can tell. In the comics they've had all sorts of de-aging chicanery occur that very pointedly ignores what an odd timeline that implies for everyone else in the X-books besides Magneto. The Cullen Bunn Magneto standalone from 2014-15 I remember actually leaned into playing up the idea that he's just old as shit and dependent on so many superscience treatments to remain functional that he's basically pickled, which was a take I liked; the comic ended when he died of exertion trying to stop two planets from crashing into each other, right before a brand-wide universal reset. When the MCU was at it's peak and people were wargaming how to integrate the X-Men (lol) you occasionally saw people float "fixes" for the issue, such as making Magneto a survivor of the Bosnian Genocide, or making him black and a survivor of the Rwandan genocide; I remember that this consistently drew a lot of ire from people who (reasonably) thought that his Judaism and connection to the holocaust were deeply important to his character, continuity be damned. But yeah, he's a character dogged by specificity in a way only Cap even slightly approaches. If this is a tractable problem I'm not going to be the one to tract it.

Interestingly, I'm genuinely having a lot of trouble coming up with stuff that's analogous to this at DC comics- almost universally the core roster updates into any given time period much more smoothly. Furthermore, DC stuff has always been much more willing to eschew Marvel's World-Outside-Your-Window philosophy in favor of deliberately obfuscating the time period via the Dark-Deco aesthetic of BTAS's Gotham or the retrofuturism of STAS's Metropolis.

The closest you get to this kind of friction is The Justice Society, who, pre-crisis, were siloed off in a universe where superheroes had existed since the 40s and there was no comic book time, so they were all in their upper-middle-age to old age now, with their kids and grandkids as legacy capes. Post crisis they were (and are) kind of an awkward fit in DC continuity; in the scant few JSA comics from the 90s and early oughts that I read, surviving members of the WW2-era lineup like Alan Scott and Jay Garrick were absolutely written as dependent on their metahuman physiques to have endured up to the present day. I think they're still doing stuff with those guys. I don't know how. I do understand the impulse, though. I also never throw anything out.

#thoughts#ask#asks#superheroes#a lot of this is just pure memory tbc#so some of this might be off in some direction or another#magneto#marvel#effortpost

228 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jimmy Carter's emphasis on human rights contributed to the fall of the Soviet empire.

President Carter had an almost instantaneous effect on human rights in Latin America when he became president. The Nixon-Kissinger policy of officially propping up dictators was replaced with one of supporting democracies. A majority of Latin American countries in 1976 were authoritarian. Within a decade, a majority were democratic or at least democratizing.

The Carter human rights policy had a more subversively indirect effect on the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe.

Historian and journalist Kai Bird said this at Washington Monthly:

He put human rights, that principle, as a keystone of U.S. foreign policy, and none of his successors have been able to walk back from that or ignore it completely. They’ve talked about some of the hypocrisy and impracticality of the policy, but you can’t ignore it. I make this argument in my biography, that human rights, the talk about human rights, and the focus on dissidents in the Soviet Union, and in Czechoslovakia, and Poland—all of that did much more to weaken the Soviet empire in eastern Europe than anything Ronald Reagan did by increasing the defense budget or threatening Star Wars. The Soviet Union was a weak adversary, not a strong adversary. It was falling apart, and along comes Carter, talking about human rights, and as Jon has said, ideas are powerful, and this idea remains powerful, and it really contributed monumentally to the falling of the Berlin Wall and people seizing power in the streets, and wanting to have personal freedom. That, in part, can be attributed to Jimmy Carter.

Michael Hirsh of the journal Foreign Policy (archived) was more emphatic.

Perhaps the least understood dimension of Carter’s much-maligned, one-term presidency was that he dramatically changed the nature of the Cold War, setting the stage for the Soviet Union’s ultimate collapse. Carter did this with a tough but deft combination of soft and hard power. On one hand, he opened the door to Reagan’s delegitimization of the Soviet system by focusing on human rights; on the other hand, Carter aggressively funded new high-tech weapons that made Moscow realize it couldn’t compete with Washington, which in turn set off a panicky series of self-destructive moves under the final Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev. [ ... ] Although he was mocked for being naive at the time, it was in large part thanks to Carter and his more hawkish national security advisor, Zbigniew Brzezinski, that human rights issues later came to the fore inside the Eastern Bloc, acting like a gradually rising flood that eroded the foundations of Moscow’s power. Helped along by the 1975 Helsinki Accords, which authorized “Helsinki monitoring groups” in Eastern Bloc countries (perhaps most famously with Charter 77 in Czechoslovakia, which set the human rights movement in motion with a 1977 petition), these newly formed dissident groups during the 1980s undermined the legitimacy of Warsaw Pact communist satellites—and thus the Soviet bloc—from within.

Daniel Friend, former US ambassador to Poland, has this to add at the Atlantic Council.

An implicit axiom of President Richard Nixon’s détente was that the Soviet takeover of Eastern Europe at the end of World War II, marked by the imposition of the Iron Curtain, was a sad but by then immutable fact. Official Washington and most of US academia regarded the Soviet Bloc—communist-dominated Europe from the Baltic to the Black Sea east of West Germany—as permanent and, though this was seldom made explicit, stabilizing. Talk of “liberating” those countries was regarded as illusion, delusion, or cant. Maintaining US-Soviet stability, under this view of Cold War realism, required accepting Europe’s realities, as these were then seen. The Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe’s Final Act of Helsinki, a sort of codification of détente concluded under President Gerald Ford, did include general human rights language, and this turned out to be important. [ ... ] Carter’s shift toward human rights challenged this uber-realist consensus. It came just as democratic dissidents and workers’ movements inspired by them began to gather strength in Central and Eastern Europe, especially Poland. Carter, and his national security advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski, put the United States in a better position to reach out to these movements and to work with them when communist rule began to falter as Soviet Bloc communist regimes started running past their ability to borrow money on easy “détente terms,” making them vulnerable. More broadly, by elevating human rights in the mix of US-Soviet and US-Soviet Bloc relations, Carter put the United States on offense in the Cold War and on the side of the people of the region.

President Carter's human rights policy was also popular among Americans of Eastern European descent.

#jimmy carter#human rights#the cold war#eastern europe#russia#soviet union#ussr#daniel friend#kai bird#michael hirsh

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Have you ever wondered why the work of Russian artists is very easy to define. So much so that there is a concept of “Russian style” on the internet?

Then it's time to learn my theory on how the “Russian style” was formed, since I've been in the Russian community of artists for about 11 years and 6 years in the foreign one and I have a lot to say.

If you're too lazy to read, I'll keep it short: it's all because of harsh criticism and harassment in the past, a language barrier where most people don't know English (or any other popular language), own methods of learning to draw, and more. However, if you want to understand more about what it all means, read my story below.

I'll probably start by saying that the peak of artistic progress started around 2013-2018. Previously, most artists sat on a social network called Vk\Vkontakte. I can't say anything for sure about whether there was any development before 2010+, since most of the artists I meet on the internet are mostly my colleagues who were born between 2002 and 2007 :D. Many of the Russian artists came to the Internet being children 8-14 years old. (back then not many adults were mostly advanced with the understanding of the Internet, so parental control was simply excluded from the rules) + the Internet itself was very free. Mix the fact of having a free internet + having kids on it and you get a very aggressive environment. I still remember how sometimes we were harassed by adults (or another kids) to tell us how terrible our art was (however, I was also bullied by adults back then) + adults tried to find my parents' contacts to write them ridiculous things like “your child is sitting on the internet and drawing children's drawings!!! That's terrible!!!”. In general, the Internet of the past was very aggressive, which means that many of us had to develop as “fast” as possible in artistic terms, otherwise you could get into the “wall of shame” (in the past a public called dno-arts or for example in Fairies in Vkontakte, as it used to be called). However, because of that, by the way, some of us have a fear of showing our work in public, lol (at least I still have a fear of drawing human characters because of that) But by 2017, things started to change. Many of us at that point grew up and rebelled against all those “walls of shame” and as a consequence, they were completely destroyed and at that point a new stage of Russian artists started to emerge. This gave more opportunities for creativity, as idiotic rules like “you can't use very bright colors in art” were eliminated and no one cared anymore. However, by about 2020, a new era of development of Russian artists' work began because of tiktok and the deterioration of Vkontakte's policy. Many of the artists went partially or permanently to telegram after 2020. Before that, the foreign community (English-speaking internet let's say roughly) was closed to us and not everyone could afford to venture out into the English-speaking internet. In general, because of the language barrier it is still closed to many of us :D. A huge number of Russian artists are still hiding somewhere in the dark corners of the Internet. With the advent of tiktok and telegram also began to appear “new” generation of Russian artists. Basically, as I personally noticed - these artists are not afraid of criticism and tend to show themselves more in public. Also many of these artists began to lose their “Russian style” and began to have rather more of a “general” style (in general, despite what I consider to be an older generation of artists (?), my style seems to have lost my “Russian handwriting” and become general? I don't know). By common, I mean that most Russian artists started mixing anime\cartoonish\semi realism style with their usual style. Although the English-speaking internet was open to us after 2010, few people dared to start their creative accounts on the English-speaking internet. But after 2020, the information for us became much wider than before. As it seems to me personally, the development of Russian artists is now centered not only in their closed environment, but also in the environment of the open world. But it is precisely because of the closed nature of the artistic Russian community that we have developed a so-called “Russian style” that is visible in one way or another in our art (lol, even I can easily tell if someone is Russian by their art) I have a lot more to say about how the Russian community of artists is developing now according to my observations. But I'll tell you about it some other time.

If anything, it's not the most reliable source for how the Russian style came to be. It's just my personal observation based on what's been happening to me for 11 years. No one has done statistics and research on this and most of the data from the past has been destroyed

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

From the homeless to a new global color line to immigrant “safe havens,” the harm will be absorbed by the unseen and the unheard.

While I’ve been at a mind-jolting workshop in Canberra about “progressive” foreign policy, my head has just been spinning the entire time from everything going on in the world. Countless political cross-currents happening at the speed of Twitter right now.

But the J.D. Vance thing stands out as singularly significant, in part because people can’t help but comment on it while appearing to be confused about what the Vance nomination actually means for everything from the defense budget to “great-power competition,” and from NATO to war in America.

This take, for example, from Murtaza Hussain—who is generally of quite sound mind—totally misreads Vance based purely on a selectively hopeful reading of Vance’s rhetoric.

I’ve made it a point to digest every Vance speech, quote, or piece of writing since 2017 (or at least as much of it as I could find). Not because I thought he’d be Veep.

Rather, initially, I was trying to understand right-wing #NeverTrumpers (he had once been one). But Vance also intrigued me because it was obvious from the beginning that he was a class subversive, cosplaying as an Appalachian working-class explainer while actually following a typical Ivy-League-to-finance-bro pipeline. He was exploiting, rather than representing, a particular rural, white working-class grievance—and that made his presentation distinct from typical defenders of ruling-class privilege.

Now, you don’t need me to tell you all the reasons why he’s a bad candidate or a danger or whatever. Plenty of people doing that right now.

What I can add is an explanation of:

How Vance’s ideas about violence are explicitly racialized (envisioning a Global Color Line),

Why a Trump-Vance presidency will never yield foreign-policy realism (because of neocon infiltration), and

How the political terrain we’re operating on has changed (Washington’s foreign policy imagination is becoming post-hegemonic in a particularly reactionary direction).

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trump’s anti-Ukraine view dates to the 1930s. America rejected it then. Will we now?

(Illustration: Brian Stauffer for The Washington Post)

This opinion column by Robert Kagan reminds us that history appears to be repeating itself. Trump's America First movement is an echo of the 1930s/1940s isolationist, neo-fascist America First movement that tried to keep the U.S. out of WWII. This is a gift🎁link, so you can read the entire article, even if you don't subscribe to The Washington Post. Below are some excerpts:

Many Americans seem shocked that Republicans would oppose helping Ukraine at this critical juncture in history....Clearly, people have not been taking Donald Trump’s resurrection of America First seriously. It’s time they did. The original America First Committee was founded in September 1940. Consider the global circumstances at the time. Two years earlier, Hitler had annexed Austria and invaded and occupied Czechoslovakia. One year earlier, he had invaded and conquered Poland. In the first months of 1940, he invaded and occupied Norway, Denmark, Belgium and the Netherlands. In early June 1940, British troops evacuated from Dunkirk, and France was overrun by the Nazi blitzkrieg. In September, the very month of the committee’s formation, German troops were in Paris and Edward R. Murrow was reporting from London under bombardment by the Luftwaffe. That was the moment the America First movement launched itself into the battle to block aid to Britain. [...] This “realism” meshed well with anti-interventionism. Americans had to respect “the right of an able and virile nation [i.e. Nazi Germany] to expand,” aviator Charles Lindbergh argued. [...] Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) has called for the immediate reduction of U.S. force levels in Europe and the abrogation of America’s common-defense Article 5 commitments. He wants the United States to declare publicly that in the event of a “direct conflict” between Russia and a NATO ally, America will “withhold forces.” The Europeans need to know they can no longer “count on us like they used to.” [...] Can Republicans really be returning to a 1930s worldview in our 21st-century world? The answer is yes. Trump’s Republican Party wants to take the United States back to the triad of interwar conservatism: high tariffs, anti-immigrant xenophobia, isolationism. According to Russ Vought, who is often touted as Trump’s likely chief of staff in a second term, it is precisely this “older definition of conservatism,” the conservatism of the interwar years, that they hope to impose on the nation when Trump regains power. [...] Like those of their 1930s forbears, today’s Republicans’ views of foreign policy are heavily shaped by what they consider the more important domestic battle against liberalism. Foreign policy issues are primarily weapons to be wielded against domestic enemies. [...] The GOP devotion to America First is merely the flip side of Trump’s “poison the blood” campaign. It is about the ascendancy of White Christian America and the various un-American ethnic and racial groups allegedly conspiring against it. [emphasis added]

Use the gift link above to read the entire article. It is worth reading.

____________ Illustration: The above illustration by Brian Stauffer originally drew me to this article. It does a great job of succinctly illustrating the Trump GOP's rightward march towards isolationism (and Putin-style dictatorship). [edited]

#america first#wwii era#republicans#trump#ukraine#history repeating itself#american history#robert kagan#the washington post

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Senate confirmed Tulsi Gabbard as director of national intelligence on Wednesday.

All Senate Democrats voted against Gabbard, a former Democratic representative of Hawaii, while nearly every Republican voted in favor. Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky was the only Republican to join the Democrats. Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, an independent who caucuses with the Democrats, also voted no, though Gabbard endorsed him for president in 2016. The final tally was 52 to 48.

Gabbard’s nomination stirred controversy because of her sharp criticism of the U.S. foreign policy establishment and “regime change” wars. Her confirmation represents a potentially major shift towards realism and restraint on the part of the second Trump administration.

*** Tulsi stepped down from the DNC to support Bernie Sanders. Yet He couldn’t be bothered to vote for her. Funny how that works.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

From the UK perspective, Trump round 2 is going to be particuarly amusing, and to give some context - it's because a few weeks ago, he accused the British government, currently led by the Labour Party, of interfering in the presidential election campaign for Team Harris.

This is funny not because that "Trump=Russian agent" crap, but because a) Members of the Labour Party were actually going across the pond to canvass for the Harris campaign b) It is well understood, as in not even an open secret, that there is a cross-pollination in terms of policy, political strategy, donors, etc. between the left liberal parties of the Anglosphere especially between the US and the UK that has been going on for decades so Labour activists in Pennysylvania or whatever is not only nothing new but the least interesting thing about the UK Labour-US Democrat link c) Because of b), Labour were looking to consolidate a revival of the Atlanticist model that defined the 1990s-2000s: a liberal internationalism (and as implied, with features of 'humanitarian interventionism') informed by an echo of third-way politics with Starmer representing a reiteration of New Labour and Harris for the New Democrats. This liberal internationalism persisted, and was even strengthened during the Bush presidency, and New Labour itself became a vector for neoconservative advisors. Labour's 'progressive realism' was supposed to underpin this, but Trump's victory undermines it completely as he conceives of no reason to even pretend that the UK is even a junior partner to the US, but a lackey to call on when necessary.

British foreign policy has since World War II been mostly about how to come to terms with the loss of its geopolitical standing as paramount hegemon - and what was most important to it since then is at least hedging closely to American imperialism, and presenting outwardly that the UK's interests are in accordance with the US. If Trump's approach to foreign policy is repeated in his second presidency, then it suggests that not only will there be a malformed iteration of Atlanticism due to the UK's and specifically the Labour government's insistence on maintaining the so-called "special relationship" in spite of so many of its MPs and even the Mayor of London having expressed personal disdain for Trump, it also potentially problematises the coordinated operations of Western imperialism currently taking place, or about to take place.

All of this presents decline of not just the American empire, but also accelerates that of the British one as well. The whinging of the British ruling class about 'sacrifices made' over Afghanistan three years ago have made that clear that this process was happening. With this, the UK is locked in the black hole of American decline, and in light of European imperialism now openly stating that they wish to strike out on their own - it is entirely a desicion of their own accord.

#uk politics#british politics#labour party#democratic party#donald trump#atlanticism#imperialism#us imperialism#british imperialism#'special relationship'#us politics#empire in decay

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Sixteen years into the Peloponnesian War, the devastating conflict between the Athenian and Spartan empires during the fifth century BC, an Athenian fleet came to rest outside the tiny island of Melos. The Melians wanted to stay neutral between Athens and Sparta, and the Athenians could not tolerate that stance. They thought it made them look weak.

Thucydides’ account of the conversation between the Melians and the Athenians has become emblematic of the harshest, most cynical form of realism in international relations.

The Melians protested that it was not right for the Athenians to force them to take a side. In response, the Athenians told the Melians not to speak of justice. Although it might be true that Athens did not have a just cause in the war, Melos was simply not strong enough to complain: “Right, as the world goes, is only in question between equals in power, while the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.”

It’s probably the most famous statement of the belief that in international affairs “might makes right.”

(…)

Claims of justice, the Melians reminded the Athenians, benefit everyone. They are a “common protection.” The big wheel could turn, the Athenians might find themselves weaker in the future, and then their present cruelty “would be a signal for the heaviest vengeance and an example for the world to meditate upon.”

A day might come, in other words, when the Athenians would wish that they had taken the protections of justice more seriously, when they would wish they could invoke them in their own self-defense. But by then it would be too late, and all those who suffered under their domination would be pleased to kick them as they fell.

Further, what would neutral observers of the international scene take away from Athens’s behavior toward Melos? Weren’t the Athenians just sowing mistrust all around them?

Thucydides writes that the Melians asked, “How can you avoid making enemies of all existing neutrals [who will worry that] one day or another you will attack them?” Athens’s cynical view of international relations created unnecessary suspicion, dissuaded others from collaborating with the powerful city-state, and increased the chances that observers would rejoice in its downfall. How could all that amount to protecting self-interest?

The Athenian behavior and the behavior of the Trump administration, the Melians seem to be telling us over the expanse of the centuries, is shortsighted. You can get away with it for a while, but the conviction that might makes right presumes that power lasts forever. It doesn’t.

The Melians decided to fight and were wiped out. But 12 years later, the Athenians, after several more displays of overconfidence culminating in a ruinous expedition to Sicily, surrendered to the Spartans on humiliating terms. Their navy was decimated, the walls of their city torn down, their democracy disbanded. Athens lived on as an intellectual powerhouse for a while, but it never recovered political power.

Many in the Trump administration bemoan the erosion of classical education and are keen on restoring the great works of Western civilization. They might want to read their Thucydides.”

#trump#donald trump#zelensky#volodimir zelenszkij#putin#vladimir putin#war#ukraine#classical history#peloponnesian war#melos#melians#athens#sparta#thucydides#greece#greek#justice#enemies#might makes right#nir eisikovits

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

One thing at least is now indisputable. We live in a multipolar world. Secretary of State Marco Rubio admitted as much during his wide-ranging interview in January with Megyn Kelly. The recognition that multipolarity is now the kind of world we live in came about, in the first instance, because Russia has not been defeated in Ukraine. Rather the reverse.

To be sure, acceptance of the fact of multipolarity does not dictate the nature of our response to it. Secretary Rubio’s preferred response, as he made clear during his interview, is to embrace—one is tempted to say relearn how to do—the “hard work of diplomacy.”

Other responses are certainly possible. A team writing for Foreign Affairs last fall suggested reinstating a far-going policy of containment of Russia, such as existed during the first Cold War. Former British defense secretary Ben Wallace, for his part, went considerably further: he suggested, in an article published in January, placing Russia “in a prison” and “building the walls high.”

Which path is the right one? Rubio’s strikes me as the best approach, especially if supplemented by what is sometimes termed civilizational realism, a school that does not—as the pure realists are sometimes prone to do—exclude moral considerations from the practice of foreign affairs. Civilizational realists accept the necessity of virtue, but they also have the sophistication to recognize that liberal democracies are not the only states capable of practicing it. As for the idealists, their problem is a tendency to get divorced from reality, and they have an annoying habit of imposing their own version of morality on everyone everywhere—or at least, trying to.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mearsheimer Realism

Do you have a take on the realist school of though seen from people like John Mearsheimer? Was listening to an interview he did that made some interesting points about ethics vs realism in foreign policy as well as the end of the unipolar world situation following the cold war. Boiled down to we need to concede on Ukraine and get Russia more aligned with the west to contain China, its not possible to do both and China is more of a threat. I can see the value of this kind of arguments but its very much at odds with some of the more morally informed view about the US opposing tyrants and smaller nations rights etc that you have at times expressed on the blog and I wanted to know if you had a take.

In short: it’s wrong, and despite being named “realism” is grounded in fiction.

For one, the growing Russia-China alliance was always going to happen. As Russia declined further into geopolitical irrelevance, Putin’s choice was to either fade away or attempt to force a return to the past by acting as the champion of a bloc to resurrect the old Cold War. He opted for the latter, and given Russia’s anemic GDP, its only recourse was to act as a bully on the world stage. To hope for Russian support against China is a fantasy - China and Russia’s growing closeness grows out of a desire to push other countries out of what they see as their spheres of influence. Even a Russia that was downright hostile to China would demand US withdrawal from Eastern Europe. If the point of realism is that countries govern according to their national interests, power politics, and self-preservation, then Russia is always going to seek confrontation with the United States because the US, EU, and NATO emerged as a credible and desirable alternative to the Russian sphere of influence after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

For two, Russia has used a variety of coercive measures against its neighbors for decades, attempting to export instability and maintain a stranglehold on the near-abroad. Under the Mearsheimer model, Russia started to be provoked with the 2008 increased NATO dialogues with Ukraine (and Georgia), but Russia had already been meddling in Ukraine years earlier, attempting to rig the 2004-2005 elections or enacting energy sanctions against Kyiv for not showing enough deference to Moscow throughout the 1990′s and early 2000′s. From the get-go, Russia is a perennially paranoid, hostile world actor attempting to export instability as a means to preserve its own influence as opposed to a sober, rational actor that sought to preserve its own power. So to expect them to align themselves and act as a good-faith actor is a pipe dream.

So yeah, it’s not only wrong from an idealistic perspective, but from a practical one as well. Should someone like Ramaswamy (who also argues for this) get into power, Putin will laugh, take everything they’re willing to give away, and continue turning his nation into a Chinese client-state all out of a vain desire to recreate the old Cold War where Russia mattered.

Thanks for the question, Esq.

SomethingLikeALawyer, Hand of the King

12 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

The Great Delusion: Mearsheimer's Critique of Liberal Hegemony

Dive into the complex world of global politics with our latest video, where we explore the intriguing dynamics of power and influence among nations. Discover how the theory of liberal hegemony, once viewed as a beacon of peace, faces intense scrutiny. John Mearsheimer's sharp critique reveals the discord and instability stemming from the pursuit of this utopian vision. Delve into the American foreign policy of promoting democracy, and the unintended chaos it often brings. Through the lens of realism, understand the significant human and political costs of military interventions. Join us as we unravel Mearsheimer’s argument for a pragmatic, restrained foreign policy that prioritizes national interests and global stability. #GlobalPolitics #LiberalHegemony #Realism #ForeignPolicy #JohnMearsheimer #InternationalRelations #WorldPolitics #USForeignPolicy If you found this video insightful, please like and share!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

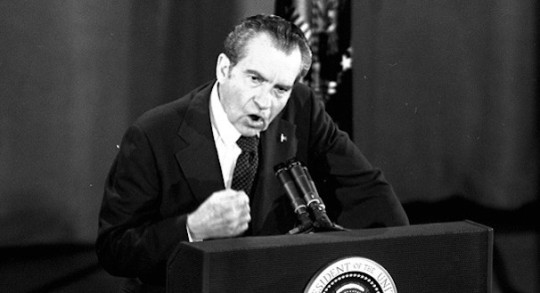

Vivek Ramaswamy and other Republicans are trying to rehabilitate the memory of Richard Nixon. I will concede that Nixon is at least a step up from Donald Trump; Nixon wrote his own books and probably even read them.

In the current GOP, Dwight Eisenhower and Gerald Ford are nonpersons; the integrity and honesty of Ike and Jerry are too high a standard for today's cesspool-dwelling Republicans.

Current Republicans are Reaganites In Name Only. If he somehow returned, Uncle Ronnie would castigate the Kremlin-friendly Trumpsters who play footsie with the Evil Empire which is now led by a onetime KGB (secret police) colonel.

The Bush clan has never been on great terms with the Trump crew. Jeb's kid, George P. Bush, had tried to save his own political skin by pandering to MAGA – but to no avail.

So Richard "Tricky Dick" Nixon enters into the revisionist GOP pantheon.

In late August, Republican presidential hopeful Vivek Ramaswamy took a break from his typical campaign events to make a pit stop at an unusual venue for mainstream Republicans: The Richard Nixon Presidential Library. Speaking before a packed house, Ramaswamy was slated to deliver a speech on foreign policy. But his opening remarks served the more provocative purpose of challenging Nixon’s much-maligned status in the annals of conservative history. “He is by and away the most underappreciated president of our modern history in this country — probably in all of American history,” said Ramaswamy, without a hint of irony. Ramaswamy’s homage to America’s most disgraced ex-president perplexed some liberal commentators, for whom Nixon remains the ultimate symbol of conservative criminality. But Ramaswamy is far from alone in rethinking Nixon’s divisive legacy. Among a small but influential group of young conservative activists and intellectuals, “Tricky Dick” is making a quiet — but notable — comeback. Long condemned by both Democrats and Republicans as the “ crook” that he infamously swore not to be, Nixon is reemerging in some conservative circles as a paragon of populist power, a noble warrior who was unjustly consigned to the black list of American history. Across the right-of-center media sphere, examples of Nixonmania abound. Online, popular conservative activists are studying the history of Nixon’s presidency as a “ blueprint for counter-revolution” in the 21st century. In the pages of small conservative magazines, readers can meet the “ New Nixonians” who are studying up on Nixon’s foreign policy prowess. On TikTok, users can scroll through meme-ified homages to Nixon. And in the weirdest (and most irony laden) corners of the internet, Nixon stans are even swooning over the former president’s swarthy good looks.

I can understand them loving Nixon for his attempts to improve ties with Putin's old Soviet Union. But Nixon as a sex symbol requires a strong imagination. He's hot only when compared to Donald Trump or Rudy Giuliani.

“No man is perfect — Richard Nixon definitely wasn’t — but one element of his legacy that I respect is reviving realism in our foreign policy,” said Ramaswamy in an interview from the campaign trail, pointing specifically to Nixon’s successful efforts to reestablish diplomatic relations with China during the 1970s. “Pulling Mao out of the hands of the USSR was one of the great victories that allowed us to come to the end of the Cold War … and it took an independent thinker like Nixon to lead us out of that.”

What Ramaswamy ignores is that Nixon escalated the Vietnam War after promising "peace with honor" in his 1968 campaign. After Nixon invaded Cambodia in 1970, large protests broke out across the US which led to the killings of unarmed students by National Guard troops at Kent State University in Ohio and Jackson State University in Mississippi.

And Nixon certainly did not pull "Mao out of the hands of the USSR" the way Vivek claimed. The China-Soviet split pre-dates the Nixon administration by over a decade. The USSR and China even fought a small border war against each other in 1969.

youtube

Ramaswamy has a pitiful understanding of the world. Like Elon Musk, most of his knowledge of geopolitical history seems to come from memes and dubious social media posts. Tech billionaires are among the most ignorant people on the planet outside of their narrow fields.

#richard nixon#vivek ramaswamy#republicans#republicans think nixon is hot#springtime for nixon#the vietnam war#china#geopolitics#cold war history#tech billionaires#election 2024

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Master of Djinn - P. Djèlí Clark

4.5/5 - classic murder mystery with magic; LOVED steampunk Cairo; Hadia <33 my beloved <33

SLIGHT spoilers below!

Fantabulous first full-length novel from Clark! I really enjoyed the characters and getting to walk around this alternate history Cairo with the characters.

Steampunk/magic earth in 1912 was a lot of fun, and I love the amount of foreign policy thrown in. Like, yes, Jim Crow America would react violently badly to a new potentially powerful minority. That's just a background detail, but Clark nails every one like it on the head. I also loved the way that djinn and magic were woven into everyday life. It just felt so real, which is really the ultimate standard for magical realism as far as I'm concerned.

The characters themselves were also super endearing. Fatma and her love of impeccable suits and a cane with a secret knife in it. Siti and her allure and uncanny (literally inhuman) sense of timing. Zagros and his love of a good book ordering system! Fatma and Siti's situationship!

But the character whom I loved the most was easily Hadia. A new agent, thrust in with a partner whose respect she desperately wants on top of battling the still ingrained misogyny in Cairene culture - there was simply no scenario in which I wouldn't love her. I also love how involved she was in the feminist politics outside of the story and how she kept trying to coordinate her hijab to match Fatma's suits!

Anyway, this was a superb first outing and if y'all ever liked steampunk (I'm thinking specifically The Girl in the Iron Corset) then you will love this novel!

#- 0.5 just because i don't usually love mystery books but it was delightfully fun!!!#also ... fatma ... does that count as monsterfuckery? i think it does and i'm happy for her!#anyway what's not to love here#gay people dead english people djinn evil english people (getting comeuppance) magic of all kinds women beating the SNOT out of annoying me#truly something for everyone#a master of djinn#p djeli clark#fantasy#book review

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Foreign policy is likely to feature prominently at the Republican presidential primary debates. At the debate in August, a question on whether the candidates would support continued U.S. assistance to Ukraine produced a firestorm. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, who had previously suggested that Russia’s war in Ukraine was not a “vital” national interest, appeared skeptical, calling on Europe to do more instead. Entrepreneur Vivek Ramaswamy was more direct in opposing such aid, calling it “disastrous” for the United States to be “protecting against an invasion across somebody else’s border.” Former Vice President Mike Pence and former U.N. Ambassador Nikki Haley, on the other hand, expressed strong support for assisting Ukraine, effectively standing behind President Joe Biden’s efforts to counter Russian aggression while imploring the United States to do even more.

On the other side of the aisle, some Democrats have been wary of Biden’s policy on Ukraine, as evidenced by a letter (that was later retracted) sent to the president by progressive Democrats, calling for a diplomatic end to the conflict and potential sanctions relief for Russia.

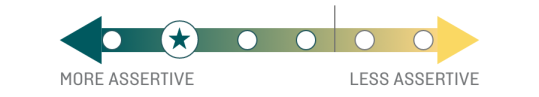

In today’s polarized political atmosphere, such cross-cutting views may appear confounding. On most domestic policy issues, whether political leaders have an R or a D next to their name is often a pretty good guide to their take on any particular issue. But when it comes to foreign policy, the normal rules of politics do not apply. Instead, of much greater relevance is where a political leader falls on the foreign-policy ideology spectrum.

The schools of thought that make up this spectrum, reflecting fundamentally different views about the U.S. role in the world, are highly influential but not very well understood.

In seeking to differentiate between foreign-policy positions, the media often resorts to cliches, such as “hawks versus doves,” or buzzwords, such as “isolationist” and “neoconservative.” However, these terms tend to be oversimplified or exaggerated and convey little useful information. International relations theories are not all that helpful either. “Realism” is routinely conflated with an academic concept that predicts how nations can be expected to behave, rather than how they should. And other theories, such as “idealism” and “constructivism,” offer limited utility in understanding real-world decision-making.

Yet there are critical differences in how policymakers view the world and are seeking to influence the direction of U.S. foreign policy. There is a clear dichotomy, for instance, between those who believe that U.S. influence is mostly positive and that the United States should play an active role in global affairs and those who believe that U.S. hubris more often leads to bad outcomes and want to scale back the country’s overseas commitments.

There is a significant divide between those who believe that the United States should prioritize efforts to advance democratic values and norms and those who believe in defending more narrow strategic interests. And there are disparate views on whether the United States should stand firm against adversaries, such as Russia and China, or should seek to find common ground.

I have delineated six distinct foreign-policy camps that represent the dominant strains of thinking on the U.S. role in the world. These camps can be placed along a spectrum of international engagement. Four of them fall on the more assertive side of this spectrum, constituting “internationalists,” who believe that the United States should exercise its influence and be actively engaged in global affairs. And two of the camps are “non-internationalists,” who believe that the United States should scale back its global commitments and adopt a less forward-leaning foreign policy.

1. Unilateral Internationalists

Defining worldview: Unilateral internationalists believe U.S. primacy and freedom of action are paramount and prioritize unilateral U.S. action, unconstrained by alliances or international agreements, to advance strategic interests. While President George W. Bush came close, especially during his first term, no U.S. president has directly embraced this school.

Key attributes:

View China and Russia as the greatest challenges to U.S. primacy in the international system and seek to exert maximum pressure to counter U.S. adversaries and project American power

Prioritize U.S. national interests, even if at the expense of allies, and favor strategic interests over democratic values or a “rules-based order”—but support U.S. alliances while skeptical of allies’ willingness to act

Are distrustful of the United Nations and international agreements and favor U.S. withdrawal from international institutions where necessary to avoid restraints on U.S. power and sovereignty

Support using military force to advance U.S. interests

Prominent voices: Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, John Bolton

Recent U.S. presidents: None

Republican candidates: None

s the second most assertive of six camps.

2. Democratic Internationalists

Defining worldview: Democratic internationalists believe that defending democracy is essential to maintaining U.S. and global security and prioritize working with like-minded allies to advance shared values and a rules-based democratic order. This school has been predominant among elected U.S. leaders—across both political parties—since President Harry Truman declared it was the policy of the United States to help “free and independent nations to maintain their freedom.”

Key attributes:

View strategic competition between democracy and autocracy as the major fault line in the international system and support proactive measures to defend against revisionist autocracies, namely China and Russia

Are strong proponents of democratic alliances and solidarity and are eager to maintain the United States’ role as the “leader of the free world”

Support robust efforts to advance democratic values and human rights and to hold autocratic regimes to account for war crimes and violent oppression

Are willing to consider use of force if necessary to defend democracy and the rules-based order

Prominent voices: Madeleine Albright, John McCain, Mitt Romney, Chris Coons, G. John Ikenberry, Hal Brands

Recent U.S. presidents: Harry Truman, John F. Kennedy, Ronald Reagan, George W. Bush, Joe Biden

Republican candidates: Chris Christie, Nikki Haley, Mike Pence

ost assertive of six camps.

3. Realist Internationalists

Defining worldview: Realist internationalists believe that U.S. power should be utilized to defend more narrow strategic interests and prioritize pragmatic engagement with all nations to help preserve global and regional stability. Former National Security Advisors Brent Scowcroft and Henry Kissinger were quintessential practitioners of this school, which was also embraced by the presidents they served.

Key attributes:

View great-power rivalry as inevitable in the global system and support U.S. alliances and active efforts to deter rival powers and maintain global order

Are willing to engage adversaries and work with all nations, regardless of regime type, to advance strategic objectives

Are prepared to make mutual accommodations with rivals, or seek to divide them, to achieve a stable balance of power

Are inclined to “accept the world as it is” and are wary of U.S. intervention and democracy promotion efforts

Support a strong U.S. defense posture and are willing to use force when required to defend vital national interests

Prominent voices: Henry Kissinger, Brent Scowcroft, Robert Gates, Richard Haass, Stephen Krasner, Charles Kupchan

Recent U.S. presidents: Richard Nixon, George H.W. Bush

Republican candidates: Ron DeSantis

4. Multilateral Internationalists

Defining worldview: Multilateral internationalists believe that peaceful coexistence with other nations should be a key objective and prioritize working through the U.N. and other multilateral institutions to solve global challenges and uphold international norms. President Barack Obama’s foreign policy was steeped in this school, now represented by former Secretary of State John Kerry, who is currently serving as the United States’ chief climate negotiator.

Key attributes:

Are wary of great-power rivalry and strategic competition and are eager to “extend a hand” and find areas of common ground with adversaries

Support active U.S. engagement to advance global norms, good governance, and human rights

Seek to cooperate with all nations to address transnational challenges, with a particular priority on climate change

Prefer to engage through inclusive institutions but support working with U.S. alliances to foster a rules-based order

Are disinclined to use military force and will consider it only when authorized by the U.N. Security Council

Prominent voices: John Kerry, Bruce Jones

Recent U.S. presidents: Barack Obama

Republican candidates: None

Non-Internationalists

1. Retractors

Defining worldview: Retractors believe that the world is taking advantage of the United States and support a more transactional foreign policy that seeks to retract the United States from global commitments and maximize pecuniary benefits. President Donald Trump’s foreign policy epitomizes this school. But its adherents date back to Republican presidential candidate Pat Buchanan in the late 1990s and the America First movement of the 1930s that sought to keep the United States out of World War II.

Key attributes:

Are deeply cynical about values and norms and seek and are prone to conspiracy theories and suspect the role of the “deep state” in manipulating U.S. policy

Are critical of alliances and disdainful of U.S. allies, particularly in Europe, and believe efforts to cooperate through international institutions are naive and self-defeating

Seek to “make deals” with autocratic regimes and are dismissive of democratic values and international norms

Emphasize economic protectionism and closed borders to prevent others from “ripping America off”

Believe the United States is militarily overcommitted but support occasional limited military actions to “act tough” and demonstrate U.S. prowess

Prominent voices: Michael Anton

Recent U.S. presidents: Donald Trump

Republican candidates: Donald Trump, Vivek Ramaswamy

2. Restrainers

Defining worldview: Restrainers believe that the United States is overstretched and overcommitted and support a more restrained foreign policy that significantly reduces the country’s global footprint. While still largely on the margins, this school has gained some prominence in recent years, as reflected by the emergence of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft and its adherents.

Key attributes:

Are distrustful of U.S. power and influence in the international system and believe that the United States has no standing to promote democratic values or a rules-based order, given its own flawed democracy, hypocrisy, and imperialism

Believe the United States has picked unnecessary fights with adversaries and that its overseas military posture, alliances, and sanctions policies are often overly provocative

Are wary of “inflating” threats posed by China and Russia and favor diplomatic efforts to cooperate with adversaries and reach a mutual accommodation and view a nationalistic foreign policy as arrogant and distasteful

Seek to reduce the U.S. military presence overseas and to scale back commitments to NATO and other alliances and vigorously oppose the use of force

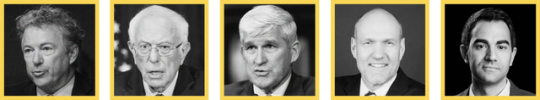

Prominent voices: Rand Paul, Bernie Sanders, Andrew Bacevich, Stephen M. Walt, Stephen Wertheim

Recent U.S. presidents: None

Republican candidates: None

Several key points follow from this analysis. First, admittedly, the edges of these camps are fuzzy, and policymakers may often find themselves straddling one or more of these camps, especially on specific issues. Nevertheless, these six schools are sufficiently discrete and represent the primary worldviews that are influencing the contemporary debate on how the United States should conduct its foreign policy.

Second, many of these schools tend to cross partisan lines. Democratic internationalism, for example, has been enthusiastically embraced by political leaders on both sides of the aisle and has strong bipartisan constituencies, as reflected in pro-democracy institutions such as the International Republican Institute and National Democratic Institute. Realism has also had a long tradition in U.S. foreign policy, resonating with national security practitioners across both parties. Similarly, the restraint school draws support among both progressives on the left and libertarians looking for Washington to scale back its global commitments. On the other hand, unilateral internationalism has found a home mainly among conservatives, while multilateral internationalism draws support mostly from liberals. In recent years, retraction has become the policy of choice among pro-Trump Republicans.

Third, determining where recent U.S. presidents fall on this spectrum is not axiomatic. While they may be inclined toward a particular camp as they enter office, most presidents are not purists, and as they govern, many find themselves running up against practical and political realities that make it difficult to maintain a consistent and predictable foreign-policy governing philosophy.

Barack Obama, for example, seemed drawn toward realist internationalism, pursuing a “reset” in relations with Russia and later declining to commit U.S. force to hold Syrian President Bashar al-Assad accountable for his use of chemical weapons. But given the priority Obama placed on engaging adversaries such as Cuba and Iran and working through the United Nations, the main thrust of his foreign policy appeared more consistent with multilateral internationalism.

George W. Bush also straddled various camps. In launching the global war on terrorism, Bush seemed determined to assert U.S. primacy and appeared to be leaning toward unilateral internationalism. But with his emphasis on democracy promotion in Iraq and Afghanistan, his signature Freedom Agenda, and his call for “ending tyranny in our world” in his second inaugural address, Bush’s overall worldview appeared to be more grounded in democratic internationalism.

Where Biden falls is still up for debate. Currently, the Biden national security team is split between realists, who pressed for Biden to withdraw from Afghanistan and reengage with Saudi Crown Prince Muhammed bin Sultan, and democratic internationalists, who championed the president’s initiative to organize a Summit for Democracy. However, given Biden’s steadfast commitment to work with NATO to defend a democratic Ukraine and his conviction that the world is facing a “global struggle between democracy and autocracy,” the broad arc of the Biden administration’s foreign policy so far seems to be more consistent with democratic internationalism—though a more definitive judgment will have to wait until his presidency concludes.

So where does this leave the current slate of Republican candidates? Pence and Haley, as well as former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, all of whom have called for standing up against Russian aggression and have denounced China’s human rights violations, are squarely in the democratic internationalist camp. Donald Trump, of course, has his own lane. DeSantis and Ramaswamy, on the other hand, appear caught between realism and Trumpian retraction, as they battle for support among the Republican rank and file who are skeptical of U.S. global engagement. DeSantis favors a pivot away from Ukraine and toward China—a very realist way to think about trade-offs. Ramaswamy, who has called for a strategy to split Russia and China, also sounds like a realist at times, but his stance on extricating the United States from any involvement in the Russia-Ukraine war, potentially ceding Taiwan to China, and putting the “interests of America first” seems to suggest he is veering toward retraction.

While voters may not consider foreign policy to be central to their vote for the next president, how U.S. leaders choose to engage in the world is critical to the security and prosperity of the American people. By gaining a clearer understanding of the most influential foreign-policy schools of thought, voters—and indeed the candidates themselves—will be in a better position to make informed choices.

33 notes

·

View notes