#first of all describing an artwork‚ even more in the case of a description aimed towards visually impaired people‚ is a skill you have to

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

personal pet peeve: when ppl add a (bad) image description to an artwork that isn't theirs

#.txt#artwork by an artist who is still alive it goes without saying#first of all describing an artwork‚ even more in the case of a description aimed towards visually impaired people‚ is a skill you have to#learn (unless you're the artist‚ then you can do what you want even though it's always nice to learn the basics and be able to describe your#art with the best possible words to convey what you wish to convey)#a description should be done with care. i see so many bad descriptions lol its almost giving the artwork a disservice#+ there's the problem of AIs. adding descriptions to artworks might make them easier to be 'stolen' and used by AI. maybe the artist cares#about that#personally i wouldnt like it if someone added a bad description to my art#but that's just my opinion etc etc

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Much delayed Holiday Ficlets

Hello to all, I hope everyone reading this is having an excellent holiday season!

As some of you may remember, last year @generallkenobi and I had hoped to send out holiday cards involving matching TCW artwork and ficlets. Unfortunately a series of illness and other IRL impediments meant we were unable to complete our tasks and had to admit defeat.

But there is some good news! Because while busy schedules haven’t allowed for completion of the artwork, the ficlets themselves were finished, and as a gift to you all I have (with my partner in crime’s permission) decided to share our three little seasonal scenes.

This is the first of three pieces: I plan to post second ficlet tomorrow evening, and then the last after that depending on family commitments.

I hope you enjoy them. :)

~~~

First Card: Winter

[Image Description: Rex and Cody are standing in a snowy field, either side of a snowman whose head is in the shape of a standard trooper’s helmet, the beginnings of blue markings showing a clear allegiance to the 501st. In the distance are snow covered trees and signs of other troopers going about general snow related festivities]

“Huh. This is actually kind of...fun.”

The tone of faint surprise in his brother's voice is enough to make Cody look up from the edge of the blue stripe he’s finishing.

“Really? I would never have guessed. Not with all the laughter coming from where Boil and Waxer are currently distracting the local children...” he offers blandly, eyes twinkling with amusement.

Rex glares at him.

“You've been spending far too much time with Kenobi.”

Cody raises his eyebrows and tilts his head in a very familiar motion. “It’s rather hard to avoid given the circumstances.”

His well honed reflexes kick in to duck the clod of snow aimed at his unprotected head, managing to avoid damaging their creation in the process.

“Oi! Don’t damage the merchandise!”

Rex huffs. “My aim is better than that and you karking well know it.”

“I do.” Cody says, unable to hide his sincerity.

Identical smiles break out on both their faces.

And they relax.

Cody hadn't realised how much he'd needed this. A moment of calm, on a peaceful planet, brother at his side, no enemies in sight…

Well not yet anyway.

Rex apparently has similar instincts.

“Do you think that maybe we might be going a little overboard on this?” he says, carefully.

“Our Generals have been assigned a purely diplomatic mission as Jedi representatives to oversee the ceremonies associated with some kind of once in a decade Force event, on a planet far from the front lines and of little strategic importance… ” Cody replies, completely deadpan.

Rex looks at Cody. And then to the faintly blinking light hidden by the snow figure in front of them and further on to the brightly illuminated walls of the nearby city.

“... You're right. Do we have another relay beacon?”

“We do once your boys return with the new LAATs.”

They share a look of deep satisfaction.

“Skywalker didn't notice the modified comms?”

Rex snorts. “Oh he did. I just told him the truth - that if this Convergence or whatever it is messes with the usual systems we want some way for them to contact us in an emergency.”

Cody chuckles. “I presume you left out the bit about the biomonitors and visual recorders.”

“If my General neglects to ask about the remote monitoring features and automatic activation in case of physiological distress it's hardly my fault is it?” Rex replies archly.

“Of course not,” Cody agrees smoothly “and we certainly don't want a repeat of the incident with the 'unknown contaminant’ on Florrum…”

Their expressions of innocence last only a second before breaking down into what is most certainly not best described as snickering.

As he regains his breath Cody takes a minute to look again at their icily camouflaged equipment. For two soldiers who rarely have the chance to explore their artistic side, the snow sculpture is rather impressive. No one would ever consider it to be anything but yet one more of the local holiday decorations celebrating their latest visitors.

He smiles.

“I think we're done here.”

Rex matches his smile before wrapping an arm around his brother's shoulders. “Yeah, me too. Come on, let's go grab some of that spiced drink the locals are so fond of and work out where we're going to put the next one.”

“Sounds good to me - but next one we use gold. You can't steal all my best recruits!”

Their laughter fades with their footsteps, as behind them the Snow Trooper begins his vigil.

All is well.

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

Civil Rights Icons' Mothers, Lost Ancient Cities and Other New Books to Read

https://sciencespies.com/history/civil-rights-icons-mothers-lost-ancient-cities-and-other-new-books-to-read/

Civil Rights Icons' Mothers, Lost Ancient Cities and Other New Books to Read

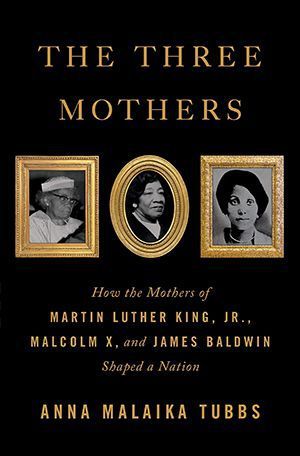

Anna Malaika Tubbs has never liked the old adage of “behind every great man is a great woman.” As the author and advocate points out in an interview with Women’s Foundation California, in most cases, the “woman is right beside the man, if not leading him.” To “think about things differently,” Tubbs adds, she decided to “introduce the woman before the man”—an approach she took in her debut book, which spotlights the mothers of Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X and James Baldwin.

“I am tired of Black women being hidden,” writes Tubbs in The Three Mothers. “I am tired of us not being recognized, I am tired of being erased. In this book, I have tried my best to change this for three women in history whose spotlight is long overdue, because the erasure of them is an erasure of all of us.”

The latest installment in our series highlighting new book releases, which launched last year to support authors whose works have been overshadowed amid the Covid-19 pandemic, explores the lives of the women who raised civil rights leaders, the story behind a harrowing photograph of a Holocaust massacre, the secret histories of four abandoned ancient cities, humans’ evolving relationship with food, and black churches’ significance as centers of community.

Representing the fields of history, science, arts and culture, innovation, and travel, selections represent texts that piqued our curiosity with their new approaches to oft-discussed topics, elevation of overlooked stories and artful prose. We’ve linked to Amazon for your convenience, but be sure to check with your local bookstore to see if it supports social distancing–appropriate delivery or pickup measures, too.

The Three Mothers: How the Mothers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, and James Baldwin Shaped a Nation by Anna Malaika Tubbs

Ebenezer Baptist Church is perhaps best known for its ties to King, who preached there alongside his father, Martin Luther King Sr., between 1947 and 1968. The Atlanta house of worship proudly hails its ties to the Kings, but as Tubbs writes for Time magazine, one member of the family is largely left out of the narrative: King’s mother, Alberta.

The author adds, “Despite the fact that this church had been led by her parents, that she had re-established the church choir, that she played the church organ, that she was the adored Mama King who led the church alongside her husband, that she was assassinated in the very same building, she had been reduced to an asterisk in the church’s overall importance.”

In The Three Mothers, Tubbs details the manifest ways in which Alberta, Louise Little and Berdis Baldwin shaped their sons’ history-making activism. Born within six years of each other around the turn of the 20th century, the three women shared a fundamental belief in the “worth of Black people, … even when these beliefs flew in the face of America’s racist practices,” per the book’s description.

Alberta—an educator and musician who believed social justice “needed to be a crucial part of any faith organization,” as Tubbs tells Religion News Service—instilled those same beliefs in her son, supporting his efforts to effect change even as the threat of assassination loomed large. Grenada-born Louise, meanwhile, immigrated to Canada, where she joined Marcus Garvey’s black nationalist Universal Negro Improvement Association and met her future husband, a fellow activist; Louise’s approach to religion later inspired her son Malcolm to convert to the Nation of Islam. Berdis raised James as a single parent in the three years between his birth and her marriage to Baptist preacher David Baldwin. Later, when James showed a penchant for pen and paper, she encouraged him to express his frustrations with the world through writing.

All three men, notes Tubbs in the book, “carried their mothers with them in everything they did.”

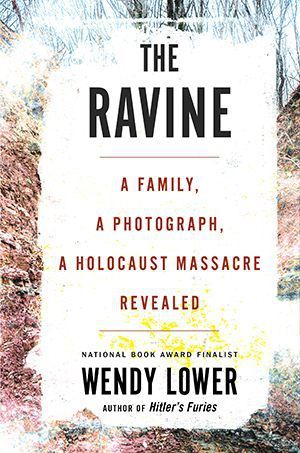

The Ravine: A Family, a Photograph, a Holocaust Massacre Revealed by Wendy Lower

Few photographs of the Holocaust depict the actual moment of victims’ deaths. Instead, visual documentation tends to focus on the events surrounding acts of mass murder: lines of unsuspecting men and women awaiting deportation, piles of emaciated corpses on the grounds of Nazi concentration camps. In total, writes historian Wendy Lower in The Ravine, “not many more than a dozen” extant images actually capture the killers in the act.

Twelve years ago, Lower, also the author of Hitler’s Furies: German Women in the Nazi Killing Fields, chanced upon one such rare photograph while conducting research at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Taken in Miropol, Ukraine, on October 13, 1941, the photo shows Nazis and local collaborators in the middle of a massacre. Struck by a bullet to the head, a Jewish woman topples forward into a ravine, pulling two still-living children down with her. Robbed of a quick death by shooting, the youngsters were “left to be crushed by the weight of their kin and suffocated in blood and the soil heaped over the bodies,” according to The Ravine.

Lower spent the better part of the next decade researching the image’s story, drawing on archival records, oral histories and “every possible remnant of evidence” to piece together the circumstances surrounding its creation. Through her investigations of the photographer, a Slovakian resistance fighter who was haunted by the scene until his death in 2005; the police officers who participated in their neighbors’ extermination; and the victims themselves, she set out to hold the perpetrators accountable while restoring the deceased’s dignity and humanity—a feat she accomplished despite being unable to identify the family by name.

“[Genocide’s] perpetrators not only kill but also seek to erase the victims from written records, and even from memory,” Lower explains in the book’s opening chapter. “When we find one trace, we must pursue it, to prevent the intended extinction by countering it with research, education, and memorialization.”

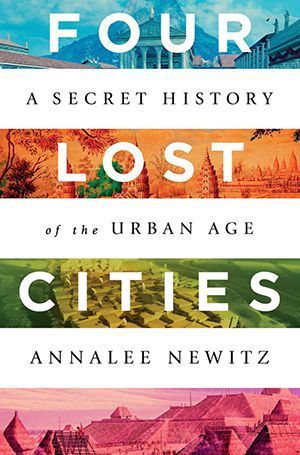

Four Lost Cities: A Secret History of the Urban Age by Annalee Newitz

Sooner or later, all great cities fall. Çatalhöyük, a Neolithic settlement in southern Anatolia; Pompeii, the Roman city razed by Mount Vesuvius’ eruption in 79 A.D.; Angkor, the medieval Cambodian capital of the Khmer Empire; and Cahokia, a pre-Hispanic metropolis in what is now Illinois, were no exception. United by their pioneering approaches to urban planning, the four cities boasted sophisticated infrastructures and feats of engineering—accomplishments largely overlooked by Western scholars, who tend to paint their stories in broad, reductive strokes, as Publishers Weekly notes in its review of science journalist Annalee Newitz’s latest book.

Consider, for instance, Çatalhöyük, which was home to some of the first people to settle down permanently after millennia of nomadic living. The prehistoric city’s inhabitants “farmed, made bricks from mud, crafted weapons, and created incredible art” without the benefit of extensive trade networks, per Newitz. They also adorned their dwellings with abstract designs and used plaster to transform their ancestors’ skulls into ritualistic artworks passed down across generations. Angkor, on the other hand, became an economic powerhouse in large part thanks to its complex network of canals and reservoirs.

Despite their demonstrations of ingenuity, all four cities eventually succumbed to what Newitz describes as “prolonged periods of political instability”—often precipitated by poor leadership and unjust hierarchies—“coupled with environmental collapse.” The parallels between these conditions and “the global-warming present” are unmistakable, but as Kirkus points out, the author’s deeply researched survey is more hopeful than dystopian. Drawing on the past to offer advice for the future, Four Lost Cities calls on those in power to embrace “resilient infrastructure, … public plazas, domestic spaces for everyone, social mobility, and leaders who treat the city’s workers with dignity.”

Animal, Vegetable, Junk: A History of Food, From Sustainable to Suicidal by Mark Bittman

Humans’ hunger for food has a dark side, writes Mark Bittman in Animal, Vegetable, Junk. Over the millennia, the food journalist and cookbook author argues, “It’s sparked disputes over landownership, water use, and the extraction of resources. It’s driven exploitation and injustice, slavery and war. It’s even, paradoxically enough, created disease and famine.” (A prime example of these consequences is colonial powers’ exploitation of Indigenous peoples in the production of cash crops, notes Kirkus.) Today, Bittman says, processed foods wreak havoc on diets and overall health, while industrialized agriculture strips the land of its resources and drives climate change through the production of greenhouse gases.

Dire as it may seem, the situation is still salvageable. Though the author dedicates much of his book to an overview of how humans’ relationship with food has changed for the worse, Animal, Vegetable, Junk’s final chapter adopts a more optimistic outlook, calling on readers to embrace agroecology—“an autonomous, pluralist, multicultural movement, political in its demand for social justice.” Adherents of agroecology support replacing chemical fertilizers, pesticides and other toxic tools with organic techniques like composting and encouraging pollinators, in addition to cutting out the middleman between “growers and eaters” and ensuring that the food production system is “sustainable and equitable for all,” according to Bittman.

“Agroecology aims to right social wrongs,” he explains. “… [It] regenerates the ecology of the soil instead of depleting it, reduces carbon emissions, and sustains local food cultures, businesses, farms, jobs, seeds, and people instead of diminishing or destroying them.”

The Black Church: This Is Our Story, This Is Our Song by Henry Louis Gates Jr.

The companion book to an upcoming PBS documentary of the same name, Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s latest scholarly survey traces the black church’s role as both a source of solace and a nexus for social justice efforts. As Publishers Weekly notes in its review of The Black Church, enslaved individuals in the antebellum South drew strength from Christianity’s rituals and music, defying slaveholders’ hopes that practicing the religion would render them “docile and compliant.” More than a century later, as black Americans fought to ensure their civil rights, white supremacists targeted black churches with similar goals in mind, wielding violence to (unsuccessfully) intimidate activists into accepting the status quo.

Gates’ book details the accomplishments of religious leaders within the black community, from Martin Luther King Jr. to Malcolm X, Nat Turner and newly elected senator Reverend Raphael G. Warnock. (The Black Churches’ televised counterpart features insights from similarly prominent individuals, including Oprah Winfrey, Reverend Al Sharpton and John Legend.) But even as the historian celebrates these individuals, he acknowledges the black church’s “struggles and failings” in its “treatment of women and the LGBTQ+ community and its dismal response to the 1980s AIDS epidemic,” per Kirkus. Now, amid a pandemic that’s taken a disproportionate toll on black Americans and an ongoing reckoning with systemic racism in the U.S., black churches’ varying approaches to activism and political engagement are at the forefront once again.

As Gates says in a PBS statement. “No social institution in the Black community is more central and important than the Black church.”

#History

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hello everyone!

As promised before, I will be posting an exhibition review below for the Montreal Museum of Fine Art’s Exhibition “Once Upon a Time… The Western”. This is a part of my final exam, however before you are thrown headfirst into the art world, I thought I would talk about what an exhibition review is and how to conduct one as an artist.

An exhibition review is much like a movie review, and as an artist or art student, you will right several over the course of your academic career. They discuss the themes and motives of the exhibition and the artworks featured, as well as the use of space and curation technique: what is the art like? How is it displayed?

Before you go:

Pick an exhibition, in most cases for your courses you will be required to pick one you can attend in real life, and I personally prefer those. If you are going to discuss a space, you should be able to go stand in it for best results.

Read some other exhibition reviews! The best part of an exhibition review is that it is about your feelings and your experience of the gallery, and shows through in other writings. You can also get a good sense of what kinds of things to talk about although I will try to help you there.

BRING A NOTEBOOK AND PENCIL! Seriously. You will not remember everything you need if you don’t write it down, and most galleries won't allow you to use pens near the art, to prevent potential vandalism.

With that being said…… WRITE THINGS DOWN! If you like a piece, or the way it’s displayed, or something about the gallery, make note of that! Your reactions, your thoughts, those are important things to have when you want to begin writing. You should also feel free (unless the museum or gallery forbids it) to take pictures of the works that particularly stick out to you, as well as the artist's description. You can also take pictures of the gallery space to help you remember what you saw, or if you are a drawing person, you can make sketches of the space and the works.

While you are there:

If the gallery has a guidebook or a pamphlet for the exhibition, take one! It will be a good reference for later and may provide information like the featured artist list and the names of the curators.

READ THE EXHIBITION DESCRIPTION. This will describe the goal or theme of the exhibition in the curator’s own words, and it is often up on the wall.

Take your time. Try to take in the exhibition as a whole. As you walk through the space, ask yourself some questions: what does the gallery space make you feel or remind you of? Can you relate it to the theme of the exhibition? How does the artwork shown relate to the theme? Is there any art that you don’t feel fits the theme? Would you arrange it differently? Who is making the art, does it all come from one group? Write down your answers because that is basically an exhibition review.

After your visit, while writing:

Talk to other visitors! Especially if you went with a class or a group for a school assignment. This will help you understand your own ideas, and hear what others thought. They may have different perspectives that you can use to inform your own writing, even if you do not agree.

Read exhibition reviews written by others! If you don't have access to other gallery visitors, then the internet can be a great resource, as many writers will post there. There are many art journals that operate online and they are worth checking out, I promise.

Visit the Museum website! There may be a full list of works shown for the whole show which can help refresh your memory.

While writing: don't be afraid to be honest! I have written many reviews about exhibitions I enjoyed, and I have written just as many about ones I did not. Share your opinion, but be sure to tell people why: if you didn't like the art, why? If you loved the use of space, why?

Language When Writing

We have arrived at the other aspect of the project, which involves confronting some frustrating situations and circumstances. If you are writing this for submission to a university, you will be required to write using some pretty stuffy and inaccessible language. This kind of “Formal” writing will often be required for a good grade.

However, this kind of voice used in academics can leave a lot of people out of the conversation. And in my opinion, art should not be exclusive, because are is universal. Everyone needs to be welcome in the conversation.

Because of this, I have written the following exhibition review using much more common language, in the interest of including everyone who comes across it on the internet. Hopefully, that will also make it easier for you to see how the writing is structured and give you some ideas on how to write this kind of review.

And if you have a thought or comment or if you have seen this show as well and want to talk about it, instead of sending me an ask, leave a comment! If someone has left a comment or question below and you feel like you have something to add or the answer, please feel free to respond! My goal is to foster discussion that welcomes everyone.

With that in mind, please be respectful of others and their opinions. You are allowed to disagree, but please keep it civil. Violence or inappropriate comments will be reported and blocked because this is meant as a positive platform for discussion.

The exhibition review is under the cut! Thank you so much for reading!

The exhibition, “Once Upon a Time… The Western” calls itself an “in-depth, interdisciplinary look at western genres”. It boasts multimedia displays, complex discussions of history, and a massive exhibition space made up of a maze of rooms and hallways. They use this space to discuss the romantic stereotypes that developed in the artistic representations of the west, and they’re continued effect today. The show is co-curated by Mary-Dailey Desmarais and Thomas Brent Smith, curator of modern art at the MMFA and Director of the Petrie Institute for Western American Art respectively.

The massive space is split up into a maze-like array of rooms, but it not hard to navigate. Each one has one entrance and one exit, meaning that even if you didn’t spend $7.00 on the audio guide, your tour of the exhibition will still have some structure. They move through chronologically, organized very carefully into parts, so it really is quite easy to guide yourself through and gain a good understanding of the themes the exhibition aims to discuss.

The first few rooms, following the Hollywood thread, are organized into “The Set” which discusses the landscape of the west, which served to inspire the artists, “The Cast” which covers the tropes and stereotypes of the mounties, cowboys, vagrants and native americans that would all be manipulated and romanticized, “ The Real Characters” which serves to showcase the real-life celebrities of the west, like Buffalo Bill and Billy the Kid, and “The Drama” discussing the so called “common” events that litter the plotlines of the hollywood western: kidnapping, train hijacking, robbery, battles, and runaway stage couches. While the first rooms do well to represent different media and art styles, they also address both side of the western story: that of the fictionalized settlers, and that of the displaced and abused indigenous people.

On the settler side of things, the first few rooms discuss the power of art, especially photography and painting. Both of these mediums presented a visual for the settlers arriving on the continent and greatly contributed to inspiring the writers and directors of Hollywood. One of these paintings, Thomas Moran’s The Mirage (1879, oil on canvas), is a perfect example of this amazing scenery: sweeping valleys and towering mountains dwarf the riding party that cross the scene near the bottom of the canvas. This goes on into an exploration of the heroes and antiheroes that shone on screen, in front of these backdrops. The Cowboys, vagrants, mounties, sheriffs, some of whom are based on real outlaws, going about their lives thwarting the kidnappings, preventing (and orchestrating) bank robberies, getting into bar fights, and living free in the open air, as shown in Charles Marion Russell’s Free Trapper (1911, oil on canvas).

The story told of the roles of the indigenous people is much more traumatic and horrifying to consider. Pushed out of their homes and lands for the sake of white colonial settlers, and massacred when they resisted, the remaining indigenous people were then further mistreated in art and film. The men became villains: holding up trains and threatening passenger, kidnapping and holding hostage “innocent” settlers, and stealing women from their husbands, as shown in The Captive by Eanger Irving Course (1891, oil on canvas). The indigenous women were romanticised and sexualized and abused. This villainization and sexualization would continue up to the present day.

The “Drama” room is also the beginning of the second and third themes of the exhibition: the different varieties of westerns in Hollywood, and the effect of various world events on the genre, and modern indigenous responses to the representations of their ancestors, and the lasting impression those representations left on North America. The “Drama” room gives way to a series of smaller rooms, which discuss two major directors (complete with dramatic, shadow lettered names) John Ford and Sergio Leon. Ford was a famed director, and his 140 films were inspired directly by the 19th-century painters explored in the first few rooms. His film, Stagecoach (1939, film), Leon came after the second world war, participating in the more international sect of western films, including the “Spaghetti Western” Sergio Leon's films came at the end of the western genre as it had been known up until that point, and his characters were tropes of themselves. Their exhibition rooms include movie release posters, massive timelines detailing their filmographies, and on the right sides of both, a screening of clips from their films for visitors to sample.

Separating the two men’s rooms is a room that discusses the effect of the end of the second world war had on the western genre. Heros became anti-heroes; brooding and outlaws, living isolated on the fringe of society. This isolation was meant to relate to the men who were returning home from the war, who themselves also felt isolated, and of course the constant threat of an atomic bomb.

Moving from these viewing rooms, we approach one of the final rooms of the exhibition. This room talks about the next age of the western after the post-war western: the western genre’s interaction with the counterculture of the 1960’s in response to the Vietnam war. The cowboy character was played with especially, in their gender and sexuality. Andy Warhol’s film, Lonesome Cowboys (1968, film), played with this heavily in order to dramatize homosexuality in Hollywood. And finally, the indigenous were shown as the victims of a violent colonial attack, much like the citizens of Vietnam were casualties of the war.

The other end of this next-to-last room, and continued into the last room, we see modern era indigenous artists responding to these representations of their ancestors. Here the multimedia aspect of the art truly shines, especially in Llyn Foulkes’ the Last Outpost (1983, mixed media) and a number of other indigenous artists, including Wendy Red Star and Gail Trembloy.

The very last room lead into a sort of entrance to the gift shop, which I referred to as the “bonus room”. It had a few seats and was showing clips of modern westerns, including Django: Unchained (Quentin Tarantino, film, 2012) and True Grit (Ethan and John Coen, film, 2010). I felt as though more could have been done with this room, as the clips were hard to follow if you were not familiar with the films (I was not) and so it was hard to relate what were shown on screen to the rest of the exhibition. This room did lead into the gift shop, which had a few large cabinets of indigenous art for sale, providing visitors with the opportunity to support real indigenous artists. Among the handmade works was a few true treasures: a cast of Miss Chief’s praying hands by Kenneth Monkland, edition two of only ten made.

Overall, the exhibition met the expectations it set at the entrance. The decision to lay everything out chronologically made it seem much more like a story and recalled the films that it was aimed at critiquing. Some of the lighting was dark in some of the rooms, especially those with projections of films, which made it harder to read the information in some cases, but this was a minor issue that did not greatly affect the impact of the works being shown.

The show also aimed to explore the mistreatment of indigenous people during colonization and continuing today. While I was glad to see this aspect of the western explored at all and I was encouraged to see modern indigenous artists benefiting from the exhibition and sale of works, it should be noted that as someone who benefits from colonialism, I cannot accurately form an opinion on the representation in the exhibition.

The exhibition will be showing until the fourth of February in 2018 and is worth visiting for its interesting and depth look at the western genre and all its implications.

#concordia#mmfa#mbam#montreal museum#Montreal Museum of Fine Arts#final exam#exhibition review#art student#art history#abbystudiesart#my posts#studyblr#studioblrcollective#studioblr#artblr

165 notes

·

View notes

Link

I don’t like the films of Quentin Tarantino. I think Woody Allen’s work is rubbish, and Brett Easton Ellis’s books suck. Am I allowed to admit to this now?

For so long, I’ve been held back by the sexist male genius paradox, which decrees that any failure to appreciate the genius of a sexist male artist must be down to one’s own failure to rise above the sexism. It’s a problem many women have, though we’re only finding out about it today.

In Uma Thurman’s recent New York Times interview, she outlined awful experiences with Harvey Weinstein, but also described how she had felt pressurised by Tarantino to drive a car that she thought was dangerous. Tarantino is yet to respond to the allegation, but more and more women are coming forward to admit they never liked Pulp Fiction anyway. We’re witnessing similar things in relation to Allen’s films.

While this may not be the primary aim of the #metoo and #timesup movements – and not liking a film is hardly comparable to experiencing assault – I think this matters. One of the many ways in which abusive men get away with terrible things is because we’re supposed to respect their genius (and assume that misogyny is somehow a necessary part of it). Right now we’re calling time on the misogyny, but why can’t we call time on the perception of genius too?

I know that to some this will sound terribly unsophisticated, but there is a relationship between misogyny in art and misogyny in real life. It’s a complex one, as female writers have been outlining in recent discussions around thrillers and true crime, and it’s obviously not the case that artistic description equates to real-life prescription. Nonetheless, when male artists produce works which consistently prioritise the inner lives and/or fantasies of men, something has gone wrong. There’s a limit to how much women should have to transpose art in order to see a world in which they, too, are human. How good is a book or film when it demands so much on-the-spot correction from the reader or viewer?

Men who don’t like women – and there are an awful lot of them – frequently make art that a male-dominated establishment considers to be amazing, but which a high proportion of women consider to be crap. You didn’t know this? That’s because up till now we haven’t said.

For women, witnessing misogyny in “great” film and literature is akin to being one of the subjects in The Emperor’s New Clothes. You can’t help but notice something is wrong, yet no one else seems to notice, so you worry that the problem lies with you (and of course you can’t say anything – anyone who fails to see the finery is a simpleton!).

Like so many women of my generation, I’ve spent years pretending to laugh at “ironic” sexism, refusing to “stigmatise” extreme pornography and bestowing serious, straight-faced analysis on the useless art of self-styled genius men. Why have I done this? Because I want to be thought of as someone who has a sense of humour, someone who’s open-minded, someone who’s intelligent. I want to be seen as someone who “gets it”, even when I don’t.

Deciding a work of art is irreparably flawed just because the entire worldview underpinning it, the characterisation, the narrative drive, the humour, the whole lot relies on the assumption that women are not fully human – well, that’s a bit naïve, isn’t it? Shouldn’t I be able to get over that?

Well, no. No, I can’t and I won’t. I’ve struggled with this “hang on, is it just me?” feeling ever since I watched my first James Bond film at eight years old and concluded that rape, in some circumstances, must be OK. From now on I will be the little boy in the crowd pointing out that the misogyny-in-art Emperor is stark bollock naked.

This is not just a case of judging an artwork by the disgrace of the artist. Bret Easton Ellis may or may not be a misogynist in his personal life (he told The Guardian in 2010 “I don't think I'm a misogynist. But if I was, so what?”). His book American Psycho, however, is packed with detailed scenes of rape and mutilation of female bodies. Writing about American Psycho in 2015, fellow author Irvine Welsh argues that accusations of misogyny are based on “bad faith” and “fatuous notions”:

American Psycho holds a hyper-real, satirical mirror up to our faces, and the uncomfortable shock of recognition it produces is that twisted reflection of ourselves, and the world we live in. It is not the “life-affirming” (so often a coded term for “deeply conservative”) novel beloved of bourgeois critics.

Obviously I don’t want to be bourgeois and conservative – who does? But honestly, this is the bullshit defence of an ultra-conservative, male-dominated art establishment which desperately tries to position misogyny – so mundane, so unoriginal, so murderous – as in some way edgy. There’s no genius required to describe pinning down a woman’s fingers with a nail gun before you cut out her tongue and rape her. I’m not shocked (I know what happens to women in real life); I’m just pissed off.

And I’m done with this, all of it. I understand the difference between art and artist (I wrote a PhD on the subject, not that this has ever silenced the mansplainers). I also understand that there’s nothing clever, subversive or enlightening about watching men in stupid suits with stupid names talk too fast and shoot each other, or in noticing a gay subtext in Top Gun, or in watching abused women die or – amazing plot twist! – not die in the end.

Just as the “best” postmodern theory tends to be appallingly written in order to fool us that the difficulty is in the ideas, the nihilism and misogyny of the “best” male directors is so glaringly obvious we end up assuming we’ve missed the hidden message (so we use “hyper-reality” as a posh way of describing unimaginative exaggeration). The real creativity isn’t in Manhattan or Inglourious Basterds; it’s in the imaginative contortions critics have gone through to make these films seem more than the sum of their parts.

There’s nothing unsophisticated in recognising that an industry mired in sexism will produce art that is tainted by sexist beliefs. There’s nothing childish or bourgeois about calling time on representations of the human condition which fail to accommodate half the human race. For too long genius has been defined as male, far removed from such petty concerns as granting consideration to the female gaze. This isn’t just unfair; it’s dull.

“You just didn’t get the irony/humour/bathos/[add your own technique]” is the male critic’s version of that lesson girls are taught from the first time they’re groped in the playground: abuse is flattery. We just haven’t learned to read it correctly. From now on I suggest we don’t even try.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝖂𝖍𝖆𝖙 𝖉𝖔𝖊𝖘 𝖙𝖍𝖆𝖙 𝖊𝖛𝖊𝖓 𝖒𝖊𝖆𝖓?

A growing glossary for my confused brain, all being alphabetical.

A

Accidental: When speaking of something accidental, most often you’d associate it with making a mistake. In art, that is an often occurrence; but it’s not always for the worse! Mistakes can force you to see your creation from a different perspective or make you have to think outside the box to cover it up/blend it into the rest of the picture. You might even end up liking your mistake as it is and choose to then embrace it.

Allegorical: Allegory is often used in art as a way to convey and symbolize a deeper moral or spiritual meaning such as; death, life, jealousy, hatred, etc.

Angular: This refers to some kind of shape, object or an outline having sharp angles and corners.

Animatic: Essentially it can be described as a moving story that is synced up to audio. In the animation industry, it is used to create a rough visual of the final product with the use of the voice recording that they have had their voice actors record. During this process, they can add and take away everything they feel like.

Animation: A series of linked images placed in a sequence to create the illusion of movement and life

Antagonist: They are the rival of the protag. A person who actively opposes or is hostile to someone or something; an adversary. They are often portrayed as characters with a dark background; an example of this could be an evil ruler that grew up in an abusive environment or something alike.

Archetype: This can be defined as a very typical example of a certain person or thing, often very generalising/stereotypes, but this is not how you would define archetypes in storytelling specifically. Archetypes can be defined as for example; the sidekick or comical release character (the jester), the mentor (wise), the innocent, the explorer, the hero, the lover, the ally, the trickster, the guardian, the shadow, the ruler, the friendly beast. Essentially, they are different roles.

Automatic: This is a way of tapping into the unconscious mind. When you create something using the technique of automatism, it means that you aren’t thinking about what you are drawing, have drawn and is going to draw next, you simply just let the pen and your hand do the work while your head is left to rest.

B

C

Chaotic: When referring to something being chaotic, most often you’d use this term to describe a piece of artwork, depending on how many individual aspects are put together on the “canvas”. In some cases, if the artist has a lot to say, it might end up affecting the way it turns out in the end; chaotic. If a piece of art is chaotic or feels busy, it could reflect something allegorical as well; a hidden meaning hiding in between all of the distractions.

Chattering: It generally means that each frame in a given animation isn’t lined up completely evenly; general imperfections are often very easy to spot once played back, but with practice, it can be avoided quite efficiently.

Clean up: This is part of the overall process of animating. It is especially often used in hand-drawn/analogue/traditional animation. In this workflow, the first (conceptual) drawings are called roughs, referring to how they are very loose and rough at this stage. Professionally speaking, when the director has approved of these roughs, this is when clean versions of these are created. This process is called clean up. The term of clean up can also be referred to as, for example, when you have done frames in ink and some of it may smudge in the process, you can scan in the frames and proceed by cleaning up the frames digitally.

Climax: A climax builds upon everything that has been introduced during the exposition and rising action. This is the moment of truth for the protagonist and the peak moment of the story. You know the plot is successful at delivering a good climax when the outer journeys and the inner goals of which the protagonist wish to complete click.

Considered: Opposite to automatism, considered art has been planned out before being done. Sometimes artists even go as far as planning out each line and colour before applying to the final product. This can be done by doing a bunch of tests and sketches, or by mind-mapping ideas beforehand.

D

Denouement: Denouement (resolution) is a fancy way of saying that the story is about to come to an end. At this point, all questions are resolved and answered; letting the reader.

E

Encounter: (verb) Unexpectedly be faced with or experience (something hostile or difficult). (noun) An unexpected or casual meeting with someone or something.

Exposition: This is where the characters of the story gets introduced alongside the story and plot itself. This is often the most difficult part to set up successfully, simply because you need to capture the readers/viewers/target audiences’ attention and have then clued in on what’s going on in the story, but this has to be done without completely spoiling the rest of the story. It is important to not mistake exposition and an info dump.

F

Falling action: So, what now? You’ve technically finished the story. Finishing a story after a climax or during one is what is known as a cliff-hanger. Cliff hangers work well in film series, but they don’t feel as satisfying. A way to see falling action could be as the old saying; “What goes up must come down.” Putting together any hanging threads not yet solved in the plot is done during this stage.

Frame by Frame: An animation will only work if key positions are lined up together. There has to be a start and a finish for it to be a successful frame by frame animation.

G

H

I

Illustration: When talking about illustration, it describes usually a drawing or an altered picture of some kind. It can also be referred to the act of illustrating; (creating, drawing, altering, etc.)

Inanimate: Doesn’t move or have any life to it. Lack of consciousness and power or motion. Not endowed with life and spirit. Some examples being; bricks; it comes alive if you throw it. inanimate things come to life.

Incongruent:

J

Juxtaposition: This is when you bring together two opposite things that may not naturally go together, go together; creating contrast.

K

L

Linework/Keyline: Linework can simply be put as a specific technique of drawing lines when talking about art. There are countless ways in which you can interpret linework, some of them being; bold, fine, scattered, clean, sharp, fluid, altering thickness, etc. - When talking about keyline, it can relate to linework as the planning part of linework. To give an example of this, it could be that you outline the image or shape of something, planning where the linework has to be placed; keyline.

Looping: Looping is where you have a sequence of frames that repeats infinitely. The first frame is the same as the last frame. It’s like an endless cycle. It’s a labor-saving technique for animation repetitive motions; walking, a breeze in the trees or running.

M

Model Sheet: When talking about model sheets (also known as a character board, character study or character sheet) it is mostly understood as a visual representation of a character to understand the poses, gestures and even the personality in animation, comics, and video games.

Mutated:

N

Narrative: This can be explained as the plot of a story. It most often includes characters and a setting as well as a person or narrator from whose point of view the story is told. It is generally speaking a spoken or written (to later be illustrated/animated to convey this story) collection of connected events. It’s how a story is told. Who? It is told to an audience. In the beginning, the scenario is set up. Why is a narrative different from a story? The story is a subjective opinion about what’s happening, whereas the narrative is more of an objectified version of that. Jack walks up the hill; story, Jack has mental problems, narrative.

Narrative theory: Exposition -> Rising action -> Climax -> Falling action -> Denouement

Neolithic: Neo means “new”, Lithic meaning “stone”- New-Stone (stone age/new stone age; creating something new from old stone)

O

Objective:

Organic: When something looks organic, it’s just another way of saying “natural”. Most often, an organic shape would appear fluid and have some imperfections to its qualities. A sharply edged shape would convey something manmade like houses or other solid manmade objects.

P

Primary research: Interviews, looking and studying imagery, galleries, museums, exhibitions

Primitive Art: The term “Primitive Art” is a rather vague (and unavoidably ethnocentric) description which refers to the cultural artifacts of “primitive” peoples - that is, those ethnic groups deemed to have a relatively low standard of technological development by Western standards.

*This term is usually not associated with developed societies but can almost definitely be found in most cultures.

Protagonist: This is the main character or one of the major characters in a play, film, novel, etc. It is not at all unheard of that the protagonist is a heroic figure for. They make the key decisions and experience the consequences of these decisions and actions. Protagonists usually go through a journey to learn and evolve upon themselves.

Q

Quest: A quest is a journey that someone takes, in order to achieve a goal or complete an important task. Accordingly, the term comes from the Medieval Latin “Questo”, meaning “search” or “inquire”.

R

Rising action: This is the moment where the plot and narrative beings picking up. Rising action is usually encouraged by a key trigger, which is what tells the reader that “now things will start to take form.” This key trigger is what rolls the dice, which then causes a series of events to escalate to then set the story into motion.

Rotoscoping: It is one of the most simple and accessible ways of animating regardless of the level of skill, aimed to create realistic sequenced movement. It is one of the simplest forms of animation and is also used universally. Rotoscoping is an animation technique that animators use to trace over filmed footage, frame by frame, to produce a realistic sequence of action and movement.

S

Secondary research: Book, documentaries, the internet, presentations, articles

Sequence: A sequence is a collection of something that is related to each other, put into a specific order to create motion, storytelling, feel, spark thoughts etc. It is used in animation, related to Frame by Frame.

Stop motion: Where you have a model or any animate objects and you move it a bit for each picture taken; when played back it should give the illusion of movement. The more frames per second, the more fluid the movement will become.

Storyboard: Storyboards are a sequence of drawings, often with some kind of direction and/or dialogue included within. They are often used for storytelling in film, television productions and comics/comic books.

Subconscious: In art, the use of one’s subconscious mind was inspired by the psychologist Sigmund Froyd and his many theories on dreams and the subconscious mind. To put it simply though, the noun subconscious describes a person’s thoughts, impulses, feelings, desires, etc. all of which are not within the individual’s direct control, meaning they simply just contribute and affect the conscious decisions and thoughts the person do and experience.

T

Turnaround: A turnaround or character turnaround is a type of visual reference that shows a character from at least three different angles. They are essential for mediums that will be showing the character from multiple different angles, such as animation and comics. Another use for these turnarounds is to make sure artists keep their character visually consistent and proportional, to pitch characters for projects and as guides for teams where a bigger group of people will be drawing the character and need to stay on model.

U

V

W

X

Y

Z

0 notes

Text

#Week 6 Reading response

Bodies, Surrogates, Emergent Systems, p. 140

I still think it’s kind of arrogant to put human bodies and artificial intelligence parallel together. I’m kinda believe that one day artificial intelligence will break that final door and become completely self functional beings. Look at how fast they involve; once pass the final point there’s no way human can keep controlling them. If that day comes, it’s even hard to say if human can still survive. Just think of the Neanderthal.

However it all starts with human body. When making artificial intelligence human intentionally made them similar to body functions. We want to make new things that looks like our self. God made human with his image, and human made their creations with their images. It’s creation, but it’s also control.

Atsuko Tanaka, p. 140

To me this is a very beautiful work for sure. The style of it is also so timely sensitive. It is also a wonderful example to show the artist’s traditional background, but not using any cliche icons or contents.

I think it’s hard to deal with the cultural background thing. On one hand, artists tend to show all the good and beautiful things they think: traditional paintings, icons, hand made styles- but all of those had already be seen too many times and used on too many inappropriate situations that already became such cliches that even not worth to look at; they are also cultural bias in both ways. Artists treasure them think they are the best over all other cultures, while ‘outsiders’ viewed them as the same thing as ‘Asians have small eyes’.

In fact, I’m thinking of China’s official cultural advertisement- it’s also been a family, father and mother, grandparents and kids who lives happily together. This kind of advertisement is aimed to be a national image for foreigners to show that how good China is. However, just put the good or not part away, it doesn’t make sense. Every cultural, every country on earth will have families of the exact same constructions; every family will have parents, grand parents and children. How is that suppose to be a cultural unique thing?

What’s more, cultural unique has this easy and dangerous trend of going into nationalism. In this case, I like this art work the most. It’s showing the Japan style; especially these multi-color bulbs. Its similar to traditional color pattern, common modern Japanese light bulbs decoration style(just visit any authentic Japanese restaurant here and you’ll see what I mean), and most importantly its content. The artist was expressing some serious cultural problems; but instead of saying Japan cultural No.1 or saying Japan gender discrimination sucks, she put it in between- everything looks so decent and honorable on the outside, but what about inside?

In short, I really like her way of dealing those topics.

Harold Cohen, p. 144

I think of Photoshop when I saw this work. Computer art media has difference from traditional media; for most of the time the label will be ‘digital’ or ‘computer’, but no one can really specify which exact ‘digital’. Because computer is artificial intelligence to some extend, so sometime it’ll raise the question about how many percentage of a digital work is actually executed by the artist? Yet how many by the computer?

However, is this really a big question? Cohen’s work might be popular among that time, but seldom do people mention it now. As human we still want to see human’s work; its imperfection made its meaningful to look. It’s almost the same when looking at ‘paintings’ by animals. We’ll never admit those to be art works. Art works have to be made by human, because creative thinking needs to be happy, satisfying, painful and all emotions mixed together during the progress, and only human can achieve that.

Chris Burden, p. 145

I think this one is somehow like Roca’s work since I actually read that first in the book, and I prefer this one. I can’t help to think about all these people with depression that I met online or in real life. Some people just yell a lot about it to get attention, while they probably not suffer it at all; other ‘real’ patients might just kill themselves quietly at one night. However, you can never tell who’s who; and you can never ask. All activities that involving suicide have the similar facts, that is people can only wait for them to come, but cannot change a thing.

Indeed, this is a nice picture. One thing I would like to point out is, except from doctors/soldiers/police, common people don’t really get that many chances to see dead people, or to be more specific, the moment before death. What is more, we cannot see our own moment for that. As a result, I was kind focus this photo on the fact that Burden’s facial expression can be a suicide person’s last minute. No matter how the artist put it as an experiment, an art work or gave it such a long list of meanings, this still is a potential suicide. That fact actually interested me the most than any other thing. We don’t really know how human died; we will never know if there is a afterlife, or if we can thinking during the last minute. As it was put in the book, the author describe it as an eerie clam, but I find it eerie from the reverse angle; It just seems too idealized, like a movie. It’s almost like ‘he passed away peacefully in his sleep’, but that was not supposed to be the result. I just kept thinking of ‘do not go gentle into that night’ when I saw and when I wrote this response, and I have no idea why.

Antunez Roca, p. 153

No doubt this is a powerful art work. To me this one is special because of this description: “A monitor with a digital representation of Antunez Roca’s body allows the user to commit violent virtual acts, like...”

I think it is a clever way to deceive the viewers, or in this case, users. I think virtual acts cannot represent real life thoughts. For example, the violence in games. Whenever there’s a school shooting/ teenager crime happens, media and public will always blame on virtual worlds. I think it was just ridiculous for Walmart to remove all the video games in their stores after a recent shooting but kept all real guns on sale as usual. Back to the art work, I think it then created this unbalance between virtual and reality acts, because users can see both in a really short time. From this aspect, I think it is powerful to see how is imaginary movement really out put, and it is about power as the artist choose as his topic.

Another point is its format. Looking at the way the artist put those device on him, it was brutal. I think that this and other similar behavior art have the same trend of wanting the viewers/users to do harsh work. Artists in these performances wanted to be hurt; they are almost inviting viewers to make them pain and even death to justify their topics, whatever those are. It’s like the viewers are physically controlling the artists, while the artists are mentally controlling the viewers. This somehow sounds like a twisted but yet common form of love.

Stelarc, p. 154

We all heard the phrase of human body is like a computer, but then the artist literally turned his body into one. I might never understand why every artist valued their body to such a high extend, but still this sounds like a good experiment.

The fact that it is remote makes it complicated. Online viewers are different from actual viewers; Online viewers are behind several screens, and also cannot receive actual timely feedback. What is more, in this art work the viewers can almost only view the artist body, which makes it so erotic in some ways than Roca’s work while electric shock could be erotic, but the way the artist put the devices on made it not. Considering the time for this artwork it is innovative at that time, but how should we view it now? It has a weird balance of questioning and teasing the viewers in some ways. The photo showed in the book also made it so irrelevant with actual human beings.

Just off the topic a bit, I think in the year of 1980-1999 many performance art included hurting body and extreme behaviors, even I can recall seeing those artists in China doing the similar acts and were (and are) viewed as lunatics. After that time, this kind of act become less and less. I do wonder if there was a universal background made it so, or just individual historical progression in individual areas separately involved into the same result.

Jim Cambell, p. 155

I like this work of trying to be offensive. It’s simple; it doesn’t have any fancy decorative pieces attach to it; but it’s enormous. I can’t really tell how religious people felt when they looked at it, but at least I’m curious. I’m not sure if Mozart’s Requiem worked in here since I can’t experience it myself, but it’s just probably because Requiem is one of my favorite and I’m having a bias of using it as a background music.

This work and Requiem also share a similarity. To some extend, they are all by product of religion; first is the Bible, then come those work. It’s an appropriation, but I can’t see them as appropriation. It’s also extremely difficult to value any aesthetic meaning of any religious holy books; it’s simply a task cannot be done. However, put the religion aside, holy books were made by human. In this case, they should be able to valued by human.

I remember in one religion and universe class, my teacher ask us to re-read the very first chapter of the Bible. I had this long term impression that in the Bible, woman was made by one rib of man. That’s one of the reason why I don’t like about the whole religion thing. However then the teacher said that there were two version of this creation of woman; in a previous version, man and woman were made in the same time. As I do find the text to prove that, I start to wonder how religion truly worked. Just as this piece, everyone can put his or hers assumption, action, experiment and literation on the Bible; and some of the viewers will be affected by those secondary sources, and leave and propagate these thoughts. Religion is about people putting their faith in a higher thing/figure, but sometimes it also can be putting the faith into other normal human that share the same level with them in this world.

Coming back to this piece, I think the artist had made his point starting but going beyond religion. However, because it’s religion, so viewers’ focus point will be forever trapped in it, before they going elsewhere.

Ken Feingold, p. 165

I don’t think the artist’s description really matches his work. In fact, I think he is a better writer than artist. To be honest, I won’t be that disappointed if I don’t look at the description but just the art work. It seems like something you can find in every big and small galleries in Chelsea; it looks cheap and unfinished. I can see the artist is telling the truth about how it functions, but there are just some words that make the whole thing not seems appropriate.

Like “nature of violence”, “interior worlds”, “cinematic sculpture” and “personality”, these are all very big words that should be used with extra caution to not let the viewers feeling they are being deceived and the artist doesn’t know what he is doing at all. There are just some well handed parts mixed with rough parts, together without transition, and make the art work fragile. For example, the artist used real people looking heads; they are very detailed; but the robotic arm and board underneath them look like some high school student work. All three heads are placing in one line, so honestly there’s not much space for movement. What bothers me the most is “that thing” before them. I can’t see the meanings that it should have; because they look like overnight undergraduate final project. This kind of nonprofessional touch in this work is just making me cannot get into it, or understand it. This is even worth when he got a nice description; reading the description only I’m imagine something that looks completely different from this one.

0 notes

Text

The New-York based artist guides us through Several Shades Of The Same Color.

Max Ravitz, aka Patricia, produces techno with a spelunker's wide-eyed exploratory flair. His new album offers infinite ways in which a listener can roam along with him. Released July 14th across three 12"s, Several Shades Of The Same Color was Bleep's album of the week and is featured among Bandcamp Daily's essential picks — they summarize it well: "The whole thing is a marvel, the kind of maze-like album that keeps revealing surprise left turns and secret passages. Several Shades reveals Patricia to be a true synth artist, comfortable in multiple mediums, bending all of them to his will." Below, Max fields our questions with patience and consideration. Sit back, cue up the kaleidoscopic trip, and get to know the mind behind the maze.

[ Several Shades Of The Same Color in The Ghostly Store | iTunes | Spotify ]

Suppose by nature an interview asks us to defy some of Several Shades Of The Same Color's listening tips ("Don't think; Just hear."). If that's alright, explain your mindset behind encouraging listeners not to over-analyze?

I could literally write a several page essay on this one topic, but I'll try my best to keep it reasonable... I'm gonna start with this immense quote by Igor Stravinsky (anyone reading who isn't familiar with Stravinsky, get familiar): I consider that music is, by its very nature, powerless to express anything at all, whether a feeling, an attitude of mind, a psychological mood, a phenomenon of nature, etc....If, as is nearly always the case, music appears to express something, this is only an illusion, and not a reality.... In my mind, music serves as an extension of language, aimed at expressing ideas that can't be described with words. Obviously lyrical music has the capacity to make this expression a bit more overt, but music began as a non-lyrical tradition and it's real power lies in abstraction. To our brains, all sound is just stimuli used to generate information. Our ears monitor fluctuations in air pressure, and our brain filters these fluctuations through past experiences to determine the source of the sound, and its meaning. For example, say you've watched an action movie with gunfire, after which, you hear a gunshot in person without seeing the shot fired, you will assume the sound was made by a gun, because you recognize it as similar to the sound from the movie. Your brain looks for these associations to derive meaning from sound, and in turn, generate the appropriate bodily response. Music, in its simplest form, is nothing more than a series of these air pressure changes, and our brain tries to translate this stimuli into information. Determining the source of the sound is often the easy part, as most people know what different musical instruments sound like, but our brains trying to understand the meaning of music is where the great nebulous mystery lies. Music journalism is often an attempt to translate this mystery into words, and its pervasiveness nowadays encourages people to approach listening from an analytical point of view where music has to have meaning. Personally, I don't listen to music in an attempt to glean its message. I'm not looking to understand why music makes me feel a certain way, the fact that it makes me feel things I don't always understand is more powerful than knowing why. If my goal as a musician was to convey some clearly discernible message through my work, I might as well just be a writer. Music inherently defies description, so the record's listening suggestions were meant to encourage people not to analyze it too much.

On that topic, what is 'body music' to you?

Well I consider body music to be any music that a listener can feel, as opposed to think about. I would say most lyrical music strays away from being body music, as the addition of words will lead the listener to consider what is being said. Also, to be clear, body music can of course elicit thoughts and ideas, but is able to do so without using formal signifiers like words. Ultimately, I tend to avoid defining musical concepts, as definitions can give rise to rules and restraints. I also avoid classifying music by genre , because in my mind, genres are essentially a set of guidelines for what a type of music is 'supposed to be'. In general, you'll find I have an aversion to the idea that music needs to follow any rules.

Your music is recorded live. Is there a certain effect or freedom or constraint to this approach?

My current solo recording process is aimed at heavily restricting what I allow myself to do. I used to spend weeks, if not months editing songs to death trying to achieve some sense of perfection, then I'd reach the end of that process and not even like what I made. After moving to New York, I met a few likeminded producers, and began collaborating more and more. Having worked in relative isolation up until that point, getting to see how other people would approach recording and production was very useful for me. Eventually I made a rule for myself that I could never take longer than a day working on a song, and if I couldn't finish it in a day, I'd just move on. In the past, I would get attached to ideas, and like one element of a song so much that I'd try to force it to work, but having a one day limit makes me move on from ideas that aren't working. In the end, I find the songs I like best, are the ones I make quickly anyways.

When performing live, how closely do you follow the recordings?

Not at all. My live and studio practices are two entirely different things. I've been collecting recording gear since I was 15, so I have a lot of equipment. On any given song I record in my studio, I can be using drastically different gear, so trying to approximate these different techniques live becomes difficult. My solution has been to just approach live performance differently. At shows, I play 90% improvisational material that has almost no relation to my recorded stuff. Occasionally I'll end up liking something from a live set enough to try and recreate it at home, but that doesn't happen often.

What were the conditions or emotions and logic that lead you to this record? When did the concept of three LPs, an epic, first enter your mind?

My only real goal in developing the record was to make something long. I wanted the opportunity to show a wider range of my musical interests than a 4-5 track record would allow for. I think that longer albums are often given more exploratory leeway than something like an EP, and I wanted to show some weirder/slower/different music than I had released in the past. I thought about doing a 2x12", but I became fixated on the idea of the 3x12", and was lucky enough to have Sam Valenti from Ghostly be open to the idea. The track-listing itself was arranged by a friend of mine named Russell Butler, who also releases on Opal Tapes, the label that put out my first and third Patricia records. I sent him the 15 tracks to listen to, and asked him to come up with the sequencing because I was struggling to do so, and I'm really happy with what he arrived at.

The title and artwork reflects the music's stoicism in ways I can't quite define. Can you?

Well the title has a few personal meanings to me, but I'm not going to share them, as I don't think they're relevant to the music. In terms of the artwork, it was done by my friend Molly Smith. I just sent her the music, gave her very little input, and she did all the heavy lifting. It was an incredible amount of work on her part, as all the images are meticulously-drawn pointillist pen drawings, and she did all the layout and graphic design work on top of that. It was a wonderful symbiotic working relationship, and I couldn't be happier with how the records came out. The chosen imagery could be related to her interpretation of the music, but that's really a question for her.

Spectral Sound is releasing the album in conjunction with your own label, Active Cultures. It's a pretty new venture — tell us about it.

Well I wouldn't even call Active Cultures a label, it's more a swirling entity lacking in form :) While releasing music will be an aspect of the project, it's really just a means to not only give myself more freedom to explore ideas, but also support my friends who are making interesting things. I find the idea of curation intriguing, so Active Cultures will allow me to flex that muscle a bit. Actually, Molly Smith who did the artwork for my record has helped develop the aesthetics for the project. I also worked with Bill Converse aka Tide Eman, who produced the Active Cultures record that came out in June. That was followed up by the Patricia LP co-released with Spectral Sound. There are a few other releases coming together, but the next record will be an archival release of music recorded by Todd Sines in the '90s, from around his .Xtrak and Enhanced days. I also recently started working on developing a website with a friend of mine named Jesse Pimenta, who records music as Dreams and has a record coming out on Apron records soon. Not sure what else to say, time will tell where it goes.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

This Open Source Software Could Make Museum Websites More Accessible

MCA Chicago front steps. Photo by Nathan Keay. © MCA Chicago.

Earlier this year, dozens of New York City art galleries were hit with lawsuits filed separately by two legally blind plaintiffs. Their common charge: The websites of galleries including Sperone Westwater, Gagosian, and David Zwirner were not readable by people with vision loss, an alleged violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

Many of these cases are pending, and the law on ADA website compliance is murky. But defendants and other cultural players who do want to break down digital barriers face the question of how they can redesign their websites to be accessible to all. One particular issue: how to provide clear information about images of artwork. For this, galleries and museums can look to the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) in Chicago, which has created a tool that seamlessly integrates image descriptions into its online platform.

Called Coyote, this program provides a system for creating, reviewing, and managing the language used to describe art—a thorny process that involves acknowledging and navigating personal prejudices. Its name refers to a Hopi legend about a coyote that wanted to see further than its own eyes would allow.

Details of the MCA's homepage showcasing Coyote image descriptions. © MCA Chicago.

Visit the MCA’s website, toggle on the descriptions by clicking “image description” in the menu on the left, and small white boxes with blue text appear atop images. The caption for Laurie Simmons’s Walking House (1989), used to promote the MCA’s ongoing survey of her work, reads: “A black-and-white photograph depicts a model house sitting atop naked, feminine legs wearing nude heels.” A work by Doris Salcedo is described as: “Four murky sepia-toned images of shoes embedded on a white wall by what appears to be surgical stitching.” These descriptions can automatically be transcribed aloud by screen readers, allowing visually impaired or blind users to imagine the artwork.

Many museums ensure that individuals with disabilities can experience art in person by providing special resources, from in-gallery audio descriptions to tactile tours. But most can benefit from improving accessibility for their virtual visitors. The MCA Chicago’s website is the first by a museum that has “intentionally created visual descriptions as a primary feature,” according to Sina Bahram, founder of Prime Access Consulting, a company that helps organizations make their digital spaces more accessible. “There are museum websites that put alt text on images”—HTML code descriptions that screen readers can detect—“but to our knowledge, this is the first to take image descriptions so seriously and surface them for all users.”

The result is a laudable example of inclusive design—a design approach that ensures products have equitable use for people with diverse abilities. In other words, the same information is conveyed to everyone, no matter their visual acuity.

Long and short description of Kerry James Marshall’s Untitled (Painter), 2009 in the MCA’s image description software, Coyote. © MCA Chicago.

Bahram was hired by the museum in 2015, when it was redesigning its website, and he spearheaded the project alongside former MCA employees Susan Chun and Anna Chiaretta Lavatelli. That year also marked the 25th anniversary of the passage of the ADA, and the MCA had been in conversations with other museums across the country about how to better serve visitors with disabilities. “We wanted to build a platform to solve a need for institutions to enhance access for visitors who are blind and visually impaired,” said Lisa Keys, MCA Chicago’s deputy director. “It was clear that we needed better tools.”

Coyote is a free, open-source software that lives in the cloud, so anyone can adopt it. Editors log in and write descriptions for images assigned to them, which get reviewed before web developers present them to the public. “Think of it like a Google Doc for image descriptions,” Bahram said. “There’s an editing and approval flow that is really critical.”

Currently, just about 10 percent of the MCA’s 20,000 or so images have descriptions, but the museum’s editorial team has devoted a lot of energy to coming up with guidelines for writing about artworks in the most effective and intelligible way. The quandaries are complicated: What kind of visual information do you include in a few succinct lines? How does diction help shape the experience of learning about an artwork? How do you clearly describe abstract art?

MCA staff gather on the stage to write Coyote descriptions. Photo © MCA Chicago.

“Our primary goals are to be accurate, informative, and to stay within [30 words],” said Sheila Majumdar, the museum’s senior editor. “The biggest challenge lies in guarding against internal biases and mistaking opinion or assumption for fact. This is why every description is reviewed by an editor, and no editors approve their own descriptions.”

The Coyote team developed a style guide (also freely accessible online) to help them decide what to include or exclude in descriptions. There are tips related to focus (“describe the objects/information most important to understanding the image”), demographic information (“default to ‘light-skinned’ and ‘dark-skinned,’ when clearly visible”); and precision (“avoid excessive specificity and jargon”). “The first question I recommend asking is, ‘What is relevant?’” said Majumdar. “There is a lot of room for interpretation. In some instances, colors, shapes, or textures might take precedence over narrative content.”

The MCA’s team is also aiming to write two descriptions for every image—a short one and a long one. Screen readers automatically read the former; the latter, which requires users to opt in, gives a more detailed and evocative understanding of an image. The aforementioned Simmons photograph, for instance, has a longer description that reads: “The humanoid house is dramatically lit against a black background, as if posing for a portrait or performing in a play. The house is angled downward toward the floor, giving an impression of sheepishness or a bowing movement.” And the MCA doesn’t only describe images of artworks; it also provides captions for promotional photography and performance documentation. Faced with a massive and growing image repository, editors are now prioritizing images related to current exhibitions and programs, while working backward to fill in text for images of artworks in its permanent collection.

Photo from MCA’s Touch Tour of Chicago Works: Amanda Williams, 2017. Photo by Nathan Keay. © MCA Chicago

A web designer might shudder at the thought of all this additional text. But the notion that it is difficult to produce a website that is both accessible and elegant is “a false narrative that we fight against,” Bahram said. “That these two things are antithetical is simply not true. It’s not only the right thing to do, but it is easy to achieve those things.”