#fichtean curve

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Can you explain the fichtean curve to me?

The Fichtean Curve is a simple yet effective approach to storytelling that can add tension, drive conflict, and keep your readers hooked!

We've put together this blog post in the Reading Room to help you make sense of what it is and learn how to use it.

#fichtean curve#plotting#plotting tips#writers#creative writing#writing#writing community#writers of tumblr#creative writers#writing inspiration#writeblr#writerblr#writing tips#writing advice#writblr#writers corner#plotter#advice for authors#helping writers#writing blog#help for writers#writing asks#let's write#writing resources#writers on tumblr#writers and poets#resources for writers#references for writers#writer#writers block

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

Which is your style: Storytelling Structure/Writing Method

I identify as a Snowflake Methodist on the long run. Glad to know there was a name for my type of writing, tbh

More info about each here

Tag your fellow writer/storymaker/lorebuilder/OC tale developer pals!

I tag for starters: @ultfreakme and @janethepegasus!

#story structure#writing methods#storytelling#three act structure#hero's journey#dan harmon's story circle#tragic plot embryo#five act structure#freytag's pyramid#in media res#story spine#red herring structure#kishotenketsu#snowflake method#seven point structure#a disturbance and two doorways#save the cat beat sheet#fichtean curve#tag game

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

i often make the mistake of thinking that i know how the world goes and that i’m prepared for it but my god am i struggling right now

#thankfully i have work and responsibilities that keep me from crawling to a corner of my mind#everything else is going to shit and i feel like i’m at step four of the fichtean curve#and like a good plot i’m to blame for the mess

0 notes

Text

♡ Whump Plot Structures ♡

This was inspired by a post about sickfic plot structure. I wanted to contribute some whump ideas of my own.

Pure Recovery Arc: We begin with whumpee at their lowest. Whumpee is getting better over the course of the story. Obstacles may arise, but they do not build on each other - each one is just overcome, and then on to the next. It often feels efficient and satisfying, like things falling into place. Every new sentence offers a relief. There is no pyramid structure and no climax - rather, this structure can be thought of as pure falling action. Relaxing to read. May read almost like a checked-off to-do list.

Rocky Recovery Arc: We begin with whumpee at their lowest. Whumpee is getting better over the course of the story, but there are frequent downturns leading to mini-climaxes along the way as whumpee overcomes each one. We're never certain if they're going to make a full recovery or not. Tension builds to a climax in which their recovery or downfall is solidified. Classic pyramid structure.

Trauma Arc and Recovery Arc: The story is divided into two acts - the first focuses on increasing trauma that builds up to a climax in which whumpee can't take it anymore and at that moment, either escapes or is rescued. The second portion of the story focuses on their increasing progress towards recovery, leading up to a second climax in which they fully overcome what they've been through (perhaps by arriving at a lesson, by getting revenge, etc.). The first and second halves can echo or mirror each other in poetic ways.

Trauma, Admission, and Recovery Arc: This is the same as above, except the story is divided into three acts. Again, the first focuses on increasing trauma building up to escape. But this time, whumpee can't talk about what happened to them or can't admit they need help after what they've been through. The second act is devoted to them spiraling until they're forced to admit their pain at the climax. Then, a third act focused on their attempts to recover can begin. Again, these acts can echo or mirror each other in poetic ways.

Buildup to Breakdown: This follows a Fichtean Curve. Every time it seems like things are getting better, a new obstacle is added to the pile. The stakes just keep getting higher - more injuries are added, they get sicker, more bad things happen. Eventually, a climax is reached in which whumpee's problems must all be faced at once, and they may succeed or fail, followed by the consequences of that.

No Conflict/Flat: Whumpee is at the same level of pain throughout the story. We're just seeing a detailed description of their pain and/or the comfort that they're experiencing. It stays roughly the same the whole time. Good for fluff fics...or for a scene of whumpee just wallowing, or sitting through torture. Often feels dreamlike and outside of time.

251 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let's talk about story structure.

Fabricating the narrative structure of your story can be difficult, and it can be helpful to use already known and well-established story structures as a sort of blueprint to guide you along the way. Before we delve into a few of the more popular ones, however, what exactly does this term entail?

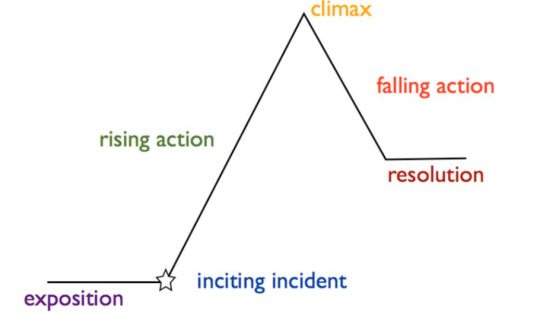

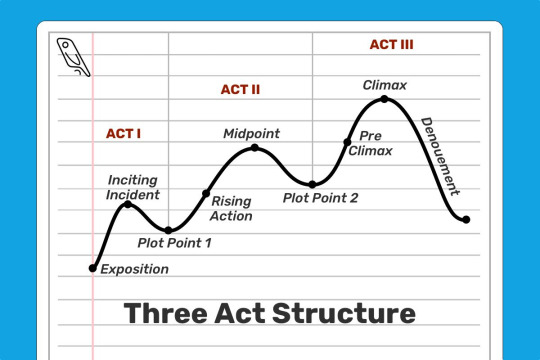

Story structure refers to the framework or organization of a narrative. It is typically divided into key elements such as exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution, and serves as the skeleton upon which the plot, characters, and themes are built. It provides a roadmap of sorts for the progression of events and emotional arcs within a story.

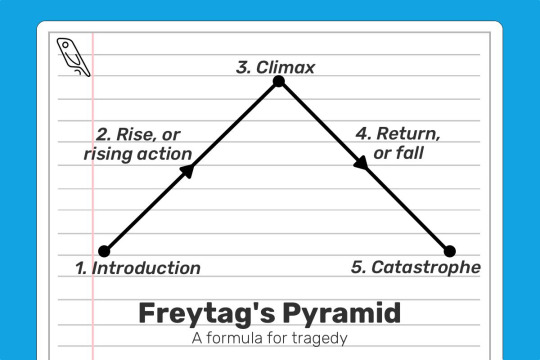

Freytag's Pyramid:

Also known as a five-act structure, this is pretty much your standard story structure that you likely learned in English class at some point. It looks something like this:

Exposition: Introduces the characters, setting, and basic situation of the story.

Inciting incident: The event that sets the main conflict of the story in motion, often disrupting the status quo for the protagonist.

Rising action: Series of events that build tension and escalate the conflict, leading toward the story's climax.

Climax: The highest point of tension or the turning point in the story, where the conflict reaches its peak and the outcome is decided.

Falling action: Events that occur as a result of the climax, leading towards the resolution and tying up loose ends.

Resolution (or denouement): The final outcome of the story, where the conflict is resolved, and any remaining questions or conflicts are addressed, providing closure for the audience.

Though the overuse of this story structure may be seen as a downside, it's used so much for a reason. Its intuitive structure provides a reliable framework for writers to build upon, ensuring clear progression and emotional resonance in their stories and drawing everything to a resolution that is satisfactory for the readers.

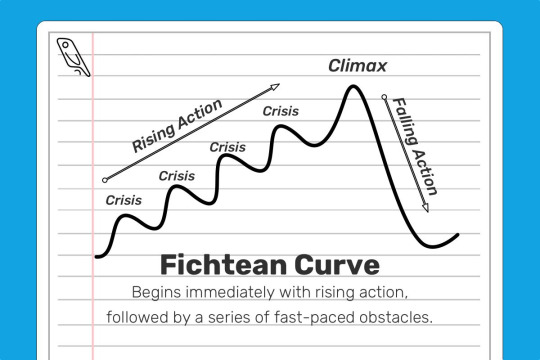

The Fichtean Curve:

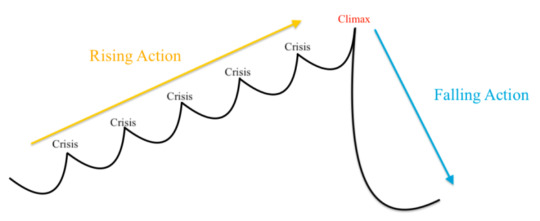

The Fichtean Curve is characterised by a gradual rise in tension and conflict, leading to a climactic peak, followed by a swift resolution. It emphasises the building of suspense and intensity throughout the narrative, following a pattern of escalating crises leading to a climax representing the peak of the protagonist's struggle, then a swift resolution.

Initial crisis: The story begins with a significant event or problem that immediately grabs the audience's attention, setting the plot in motion.

Escalating crises: Additional challenges or complications arise, intensifying the protagonist's struggles and increasing the stakes.

Climax: The tension reaches its peak as the protagonist confronts the central obstacle or makes a crucial decision.

Falling action: Following the climax, conflicts are rapidly resolved, often with a sudden shift or revelation, bringing closure to the narrative. Note that all loose ends may not be tied by the end, and that's completely fine as long as it works in your story—leaving some room for speculation or suspense can be intriguing.

The Hero’s Journey:

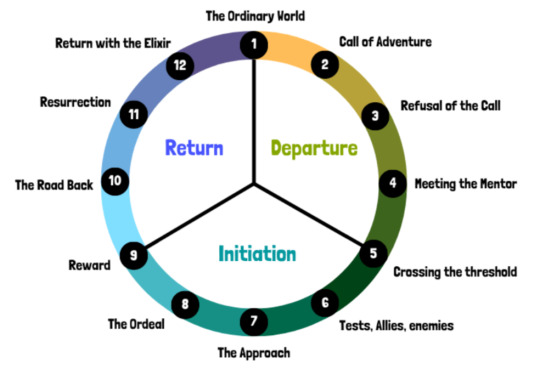

The Hero's Journey follows a protagonist through a transformative adventure. It outlines their journey from ordinary life into the unknown, encountering challenges, allies, and adversaries along the way, ultimately leading to personal growth and a return to the familiar world with newfound wisdom or treasures.

Call of adventure: The hero receives a summons or challenge that disrupts their ordinary life.

Refusal of the call: Initially, the hero may resist or hesitate in accepting the adventure.

Meeting the mentor: The hero encounters a wise mentor who provides guidance and assistance.

Crossing the threshold: The hero leaves their familiar world and enters the unknown, facing the challenges of the journey.

Tests, allies, enemies: Along the journey, the hero faces various obstacles and adversaries that test their skills and resolve.

The approach: The hero approaches the central conflict or their deepest fears.

The ordeal: The hero faces their greatest challenge, often confronting the main antagonist or undergoing a significant transformation.

Reward: After overcoming the ordeal, the hero receives a reward, such as treasure, knowledge, or inner growth.

The road back: The hero begins the journey back to their ordinary world, encountering final obstacles or confrontations.

Resurrection: The hero faces one final test or ordeal that solidifies their transformation.

Return with the elixir: The hero returns to the ordinary world, bringing back the lessons learned or treasures gained to benefit themselves or others.

Exploring these different story structures reveals the intricate paths characters traverse in their journeys. Each framework provides a blueprint for crafting engaging narratives that captivate audiences. Understanding these underlying structures can help gain an array of tools to create unforgettable tales that resonate with audiences of all kind.

Happy writing! Hope this was helpful ❤

Previous | Next

#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing advice#writing help#writing resources#creative writing#story writing#storytelling#story structure#plot development#outlining#plot structure

397 notes

·

View notes

Note

any tips on how to plot a story? Becuase I always come up with a vague idea but then i draw a blank because i have no idea how to put it in motion T~T

Opened my laptop to answer this, so it’ll be long. Still, I can make another post about it later if anyone else is interested. Important to say there isn’t a correct answer for that, each person does it their own way. That's how I do.

First, tell yourself the story: I know this probably sound silly, because technically we already know our stories, right? We know what we want to write. But then, I think that most of the times we have concepts, not stories. We have scenes we want to write, side characters that will show up in three chapters then die, so much dispersed information that we can’t properly link to write a cohesive story.

So, I literally tell myself my stories before I write any real paragraph. You can do it in multiple ways, you can write it down, record it, draw a mind map (I do it later in the process, but could work too at this point), explain it as if you were studying history (not a joke, I do that).

Think about, you won’t start teaching yourself French Revolution and go right into the Storming of the Bastille, even though is an important moment. You’ll first introduce yourself to the background, where it takes place, then you’ll name the main participants from each side, the time it lasted and its outcome. And all this in a very surface level. Only when it’s finished, you’d go into specifics.

Whatever way you feel works better for you, explain yourself your history.

Now that you know your history…

Second, pick a story structure: There are plenty of those, I particularly use the Freytag’s Pyramid. That’s what works for me. But there are many ways you can structure your story, and this you must personally try yourself each.

Here are some other examples for you to try:

Save the Cat

3-Act Story Structure

Fichtean Curve

Hero’s Journey (I personally prefer this to write characters arcs, but we’ll see it later)

Snowflake Method (I used this for some time, worked for me and I still use some elements of it)

Seven Point Structure

There are many other story structures you can try, the thing here is: the structure is meant to help you, not get you stuck. You can make changes in the story structure if you need to, the only thing that you must stick with it: Beginning (introduction of major characters and conflict), Middle (conflicts, development of the world and characters), End (conclusion of major characters arcs, be it good or bad).

Third, write the characters arcs: Even if you work has a lot of worldbuilding, what really drives your story are your characters. So, take your time to know your characters as they are in the beginning of the story, because these are the characters that will drive the plot. Who they are? Why they are like this? How do they look? How the way they look reflects how the world impacted them? Because the world also must affect your characters. How old are they? Do they behave accordingly to their age or not?

You must know where your characters are at the first chapter to know where they’re going from there. Do whatever it takes to get acquainted with them, create playlists, boards, draw them, make personality tests, etc.

Once you know who they are in the first chapter, you can start outlining their character arc.

But here is the thing, not character arc needs to be good. Sometimes, our characters get bad, sometimes they get good, and sometimes they don’t finish their character arcs (if you know you know). Treat your characters fairly, do not give them too much or too little unless it’ll impact them in the story.

You can have overpowered characters, but you’ll have to balance it with something else that’ll will drive their change throughout the story. You can have characters that are very delicate, but you’ll have to give them something to drive them to action, be it externally or internally.

Also, is important to know about your characters morals. Even if they’re in a grey area, what he’s more leaning to? What circumstances would drive them the other way? What are their priorities? What are their ambitions? What are the lengths they’re capable of going to reach it. Trust me, it’s important that your characters have ambitions. It doesn’t need to be something “in the real world” like a throne, or a job, or whatever. It can be living in safety; it can be learning something. But a character without ambition falls flat.

You can have morally good characters and morally bad characters, but even them must have something that readers can engage and identify with. Not necessarily something that turn them into a villain, not necessarily something that comes out as “they were never bad.”

For example, you can have an exceptionally nice character that makes choice that beneficiates themselves or a determined group that they personally support, it doesn’t turn them bad, because people will make choices all the time and it impacts other. At the same time, a mean character can be relatable through characteristcs that aren’t meant to be redemptive, they can be hardworking, they can have interests that not necessarily relate to their “mean” goal, they can even be on the “right” side but in a “reasons justify the means” way.

You need characters to take actions. Otherwise they'll become simply plot devices. And plot devices need to exist, don’t get me wrong, they can be useful. But the thing is: people don’t relate to plot devices. I could list a lot of characters with sob stories that were obviously meant to shock the audience, but I couldn’t care less about the sad things happened to them, because the author needed a bad thing to happen to go from point A to point B. Okay, I understand that. But it happened to a character we're constantly told we have to pity, and there is nothing else about them. People don’t care about plot devices, so if you want people to care and like your characters, give them agency.

Yeah, this is getting long. Sorry. But let’s talk about agency.

Allow your characters to make choices. Bad choices, good choices. Whatever choices they make, it needs to have consequences. A story without consequence is a weightless story. I t’s also important to make the character make choices, even if they’re being highly manipulated by someone, they must—eventually—walk on their feet. The plot is consequence of the characters choices, so don’t let the character become the plot punchbag.

Trust me, it’s easier for a reader to enjoy an unlikable character with agency than a likable character that does nothing and never stands out for anything. Your character can be anything—annoying, ugly, spoiled, cruel, anything but agency-less.

Important to say: The characters are stupid. People are stupid in general, and we react terribly bad under stressful conditions. We’re like enzymes. We stop working if we’re not in the proper conditions of pH and temperature, some enzymes will work in the intestine, but others will only work if they’re in the stomach. Different enzymes work in different environments, and so do people. What drives a story is conflict, so your character is usually stressed. It’s not a 100% of the cases rule, but if you’re character is in a super tricky situation they never been in, don’t make it easy for them to get out of that. If everything turns out easily, why should I care if the character is in a live-or-die situation?

Of course, if they have fought two dragons and survived, I expect them to live when they fight the third dragon. But if they never fought any, I want a good explanation why they’re alive and cracking jokes. As I said, characters are like enzymes. Some will do well fighting dragons but will cry their eyes out if they’re exposed to a sea monsters. Each situation is different, so analyse it.

Now, the character arc.

Your character needs to go through change, they need to find out something at least. It doesn’t need to be a good change; they can become a worse person (negative arc). They can become a better person (positive arc). But they need to go through change. Even if you have an impressive worldbuilding, well-built universe rules, a functional magical system… Everything is meaningless if the character is conflict-less (internally or externally).

There are flat arcs, but they usually serve other purposes. You can read into it if you're interested, but I never focused much on it so... Let's keep going.

Your character arc takes character from point A to point C. Because between A and C there is B, that’s usually the moment the character thinks they have it all, or they give up their journey, then something happens, and they start moving toward C again.

Again, there are many ways to structure a character arc. I usually follow The Heroine’s Journey (Maureen Murdock) or The Virgin’s Promise (Kim Hudson). These were inspired by the Hero’s Journey (Joseph Campbell), which is great too, I just feel like these helped me more. They don’t have to necessarily be applied to female characters only, in the same way that the Hero’s Journey doesn’t have to be used for male characters only. This is just a structure to help you see how your character changes throughout the story and can be used to write any gender.

I recommend you reading the books, this will help you a thousand times more than I ever could.

These are archetypical structures. The “hero” and the “heroin” are archetypes, so is the “virgin.” I also recommend you reading about archetypes, because our characters usually fit one or other, and if you don’t know what’s your character archetype is, you should find out. It helps to identify problems, because sometimes you’ll fall into stereotypes that you not necessarily want.

Fourth, about side characters: In a way, all that I said applies to side characters. But at the same time, it doesn’t.

You don’t need your side characters to be as flashed out as your protagonist(s), but they need to have some depth. The way your side characters interact with your protagonists and vice-verse says a lot of your protagonist. If you create this real nice person, who is supposed to care about everyone and be a selfless person who would take a bullet for their best friend, don’t turn the best friend into the protagonist’s sidekick.

You know those 2000s movies with the usually POC, or queer coded or often regarded as less attractive friend is always there for the protagonist, but then they ask to ONE THING and the protagonist will be like “Actually, I have plans”. Yeah, that. Your very nice character can become a dumbass because they’re never showing empathy toward others, as your very mean character can become a fan’s favourite because they’re treating people with more respect than anyone else in the story. It can’t be intentional, it can’t be part of their character arcs, but if it’s not, beware.

The way the side characters interact with the main characters is as important as the character interacts with the world. The don’t need to have super detailed backstories, but they need to have something. A goal that’s not necessarily is related to the protagonist.

For example, Grover is Percy’s best friend and protector. But he’s main goal ain’t protecting or be Percy, his main goal is to find Pan. Which makes sense (and it makes me so sad, because I love Grover) why his story basically “ended” with PJO original series. He accomplished his goal, and though I’d love to see him amongst the Argo II crew, putting him in that situation would turn him into Percy’s sidekick and nothing else. He’d be throwing all his responsibilities away (he’s literally Lord of the Wild at that point) to help Percy, and though we can argue he could help… Gaea was rising, this probably affects the nature spirits he’s supposed to care.

And most importantly: Percy cares about Grover. We’re shown this multiple times throughout the story, and if he didn’t care as much about Grover (his first friend introduced into the story), we wouldn’t believe that his fatal flaw is personal loyalty.

We don’t know everything about Grover, but we know enough to not break the entire narrative when we think about his relationship with Percy.

Keep this energy with side characters. Not everyone needs their entire story to be told, but you need them to feel as their own person.

Same goes for characters that don’t like your main characters. Some characters can be annoying and mean, but why? Is there a reason this character pesters the protagonist? Are they prejudiced somehow? Does it have something to do with class? Is there a hierarchy that ends up facilitating that sort of behaviour? Why no one does anything? Is it jealousy? Are they getting something by acting like that? Was it caused by something the main character did in the past? Do you protagonist fights back or they don’t? In whatever case, why?

Not every character who dislikes the protagonist needs to be a villain. It’s normal that people might dislike others, nobody pleases everyone, is nice having characters who don’t think the protagonist is the most awesome person in the world.

Just like the main character, it’s important to allow side characters to make decisions and have agency. Even if the reader ain’t inside their mind, these characters need to have ambition. Sometimes, you can use them to drive the plot somewhere, or to teach the protagonist something. Again, look into archetypes it might help.

However, if you keep showing a side character and never gives them a moment to shine, it might disappoint your readers. At the same time, using a character mentioned twice without any foreshadowing might come out as a dumb solution for some conflict.

So beware how you use side characters.

Fifth, write as much as you can… but not chapters yet: If you, like me, is dealing with worldbuilding, timelines and different POVs, you should plan how will this work before you get into the actual story.

Now, you can draft the whole story down as it is in your head.

Again, you don’t need to necessarily write. You can record yourself, or you can draw (I do it a lot), make mind maps (which is my case, I make mind maps to see were different things meet), or you can write multiple paragraphs about it. Just make sure you have a general idea before you start writing, make slideshows, spreadsheets, etc.

Write think pieces about characters relationships, make memes, make incorrect quotes, anything that helps you set things up inside your head.

This is a part that never ends, because sometimes you’ll have to look back and see what is lacking, what needs to be done or redone. Don’t be afraid of coming back here, rearrange the plot points, redraw characters. Your first draft will hardly be the one you’ll stick with.

I use obsidian for worldbuilding. I cannot really explain how obsidian works; it’d be like trying to write down how to draw on Photoshop. But I use the canvas plugin to draw the plot as a mind map, and I also use canvas to make a linear timeline.

This is the outline for a part of my fic, I didn't screenshot it all because it'd be too big. But you get the idea.

This is my linear timeline, is very useful to check info quickly.

To outline chapters, I use spreadsheets. I make enough room for general info, then a little resume of the chapter, and the white blocks beside the chapter I can write what scenes I want for those chapters.

Again, very simple.

I check the spreadsheet occasionally, because I sometimes change order of chapters, or add something. Your outline is an asset not a rule, you can change it if you feel is not working.

Sixth, write: After you went through it all, writing will become much easier, I can assure. But even then, you’ll face moments in which you feel that you’re stuck. But if you can write one hundred words every day, is already better than no word at all.

If you feel it might help, try different writing tools, try editing your document to make it aesthetic and to fit your story vibe. I personally use scrivener (it’s great for organisation) for some stories, and for others I use Microsoft Office, but there are cheaper or free options. Obsidian does basically everything Scrivener does, but it’s a bit trick to use if you’re new. So, it might take some patience, and it’s not as editable as other software (unless you are now a bit of code, which is not hard but is also not for everyone), there is Google Doc, and some open-source options like Libre Office, you can even write on Notion (I used to, I have templates for it even).

When you’re writing, treat yourself. I make myself coffee or matcha, I put some music, or I buy myself cheesecake. Try not to make your writing session a “I have to do it” moment, enjoy it, even if you aren’t writing your intended 10k words (trust me, setting such ambitious goals won’t help you in anything).

Sometimes, nothing good will come out. Sometimes, you’ll feel like you should win a Pulitzer. Just enjoy writing and do be afraid of committing mistakes.

I think this is it. I wanted to go deeper into some things, I wanted to speak of antagonists and conflict more deeply, but it got big enough. I hope I made sense and I helped, be free to ask if my non-native english speaker ass wrote something senseless.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

today's disconnected but related Thoughts are about how stories should exist within "containers", and how problems in long-running TV series are typically introduced when the writers don't use those containers properly. I'm struggling to articulate it in a coherent order, but:

● an audience needs to be able to see some kind of boundary enclosing the story, otherwise it doesn't feel satisfying. This is why we have set plot structures like Freytag's Pyramid and Fichtean Curve which so many stories follow. Most storytelling formats lend themselves to this – novels, certain comic books and graphic novels, plays, and films all have a beginning and an end. You open the book or enter a theatre or switch on the telly, and you experience the story, and then it ends. The story might live with you afterwards, if it affected or resonated with you or made you want to analyse it, but if the creator did their job well you'll at least feel closure with it on a mechanical level (i.e., plot and character arcs have conclusions that you can see fit within the framework of the story, even if personally you didn't like or agree with something). The Good Place is an example of a TV series that did this very well, because the writers had a set vision for the series and they executed it.

● A lot of TV dramas and serials operate on the premise of being ongoing – a story that stretches on without any defined end in sight. This can be done well, but sometimes the story gets bloated and stale, or it ends up like separate swatches of cloth instead of an interwoven tapestry. I'm not saying this means every TV series automatically fails to tell a story in a satisfying way, or even that the series that don't are inherently bad. It works differently from books or films, and therein lie its strengths as a storytelling medium! For one thing, TV is excellent for character-focused stories, and these can go on and on for ages and still be enjoyable and entertaining (even if not "good" by critical artistic standards). There's also more flexibility in TV than in a film; the ongoing format lets writers string out rising and falling tension, and focus in and out on different plots/subplots across a far larger scope.

● The way these shows work is the overarching medium of the series contains smaller stories in the form of plots. The boundaries between one plot and the next usually need to be permeable, too – a plot arc should conclude satisfactorily, yes, but the things that happen in it ought to resonate with the larger narrative afterwards, otherwise it'll feel pointless to the audience. Ghost Whisperer is an example where the creators failed to do this, repeatedly: each of the five seasons introduces a new concept which seems to be building towards some kind of climax, and then... doesn't. Characters vanish from the story never to be mentioned again. Huge events that ought to have life-altering consequences for the characters only have consequences for a few episodes, and then it's swept under the rug. The series had its appeal in a fun concept and lovable characters, but was let down by the execution. By contrast, medical drama Grey's Anatomy has been going successfully since 2005. It has some continuity issues (like interns vanishing without explanation) and some plots are better than others, but on the whole it takes its status as a long-running story seriously and does it quite well.

● The streaming model and the way TV writers are treated is a factor, too. Even where the boundaries of a story have been pre-defined and could be executed well, the creators often don't have the chance. (and I'm sure the same is true of long-running manga/comic books/graphic novels, although I'm focusing mostly on TV here). Ratings, network politics and actors' personal lives/ambitions have a huge impact on what happens to a TV series, and the popularity or apparent success of a series doesn't always guarantee its continuation. Just look at Netflix's habit of axing series after 2 seasons! Or at Good Omens, which despite being written by Neil Gaiman, having a huge fanbase, and a pre-set story which would be concluded in three seasons, hasn't yet been officially greenlit for season 3 (afaik). The industry has created an environment where stories are commodified, and that's not an environment in which stories can flourish.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

WtW Ghost Gala - Day 7: Skeleton

Have a favorite plot structure? If not, share how you plot!

As a chronic pantser used to figuring stuff out as I go along, I needed a brief dip into research before answering this one.

Now, with an idea of the most popular plot structures in mind, I have to say that I don't think I have ONE favorite one, because different ones work for the different stories I tell (although, full disclosure, I don't see myself using Freytag's Pyramid much, because I write sins not tragedies always lean towards if not happy, then hopeful, endings).

I think my current WIP maps very nicely to the Save the Cat plot structure: at least, I was able to outline Act 1 of it to the StC beats without changing anything I had planned.

Overall, I have a soft spot for Hero's Journey and Dan Harmon's adaptation of it. Pretty sure that the first novel I ever finished followed that.

And finally, to my great amusement, I think that my ~300k word fic (that's still a few chapters away from done) maps pretty well onto the Fichtean Curve! Despite the fact that this structure is often held up as the one for fast-paced stories. It's entirely possible that I've piled up a little too many crises onto my hapless protagonists along the way...

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Also known as the Fichtean Curve plot structure so quit coming @ me and do as you're told

The point of fiction is actually to put that guy in a situation™️, and he might try to tell you the point is to then get him out of the situation, WRONG, second situation

#what do you mean 'but you just keep adding curves'#i have a Plan#you're just faithless and frankly im hurt#writfunnies

57K notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Text

Plot: the Fichtean Curve

You may have gone over Freytag’s plot structure in English class, but it’s probably not the most realistic mapping of your novel. For the next few days, I’m going to be covering plot structures that could very well make up the foundation of your outline.

If you have a particular structure you’d like me to go over, send me an ask!

So, without further ado:

The Fichtean curve starts with the rising action instead of exposition. It’s not realistic to get all your exposition out at the beginning of the story, and even if you could, it would strip away a lot of the mystery surrounding your characters. Instead, exposition is scattered throughout the story.

You’ve probably also noticed that one side of the triangle is not straight. That’s because your character’s path won’t be smooth sailing; that would be boring. They’ll deal with mini obstacles, crises that will include their own mini rising action and falling action. Crises are good because they’ll be able to:

Develop your characters and their arcs

Develop relationships between characters

Establish setting by contributing to the worldbuilding

Foreshadow future conflicts, internal and external

Serve as opportunities to elaborate on characters’ backstories

The climax will occur about 2/3s of the way into the story, leaving the remaining third for falling action. This last third will be the time when you resolve loose ends and establish the new normal for your characters.

Check out the resource tag to find other resources toward building your novel!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Different Plot/Story Structures

There are a lot of different plot structures that you can play around with when writing a story. This post is just providing some of the more common ones for you to know. While these structures are not to be adhered to completely, they can provide a good basis to get a story running and help keep it on track.

Freytag's Pyramid

Freytag's pyramid is one of the oldest and most well-known story structures. It consists of five acts: introduction, rising action, climax, falling action, and conclusion. Falling action and conclusion do not mean a decrease in intensity, but rather a shift in the plot or the stakes for the characters - aka surpassing "the point of no return." What works about this structure is its ability to heighten action in a story and introduce plot twists to make a story grip the reader.

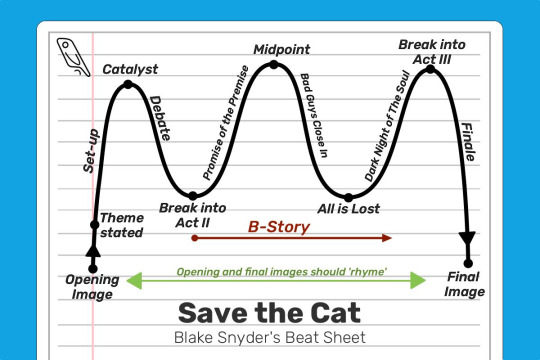

Save the Cat

Save the Cat is a newer structure that was initially constructed for TV shows, but it works well in a larger story as well, regardless of medium. It breaks up the story into an A-plot and B-plot, shifting action between the two to balance intensity with moments for the action to cool down. Typically, the A-plot has higher stakes than the B-plot and is the main focus of the characters. What works about this structure is that it effectively utilizes side-plots to not just accompany, but enhance the main plot.

The Fichtean Curve

The Fichtean Curve is essentially a series of mini-stories that build up to a greater story, with the stakes elevating during each story. It's similar to a TV season that has several episodes, each one advancing the plot while providing a smaller story that keeps the excitement continuing. What works about the Fichtean Curve is the freedom to move non-linearly through plots, using perspectives of different characters, different settings, and different mini-plots to enhance the story.

Free-form

Free-form is exactly what it sounds like: letting your mind run free while writing your story, disregarding traditional story structures and trusting yourself. This doesn't work for everyone: in fact, I believe that almost all writers need at least a little bit of structure when writing. But mapping out a beginning and end, and letting yourself find your own path to connect the two is what works for some writers. Besides, you can always go back during editing and figure out the most efficient way to map the pieces together!

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Story Structures for your Next WIP

hello, hello. this post will be mostly for my notes. this is something I need in to be reminded of for my business, but it can also be very useful and beneficial for you guys as well.

everything in life has structure and storytelling is no different, so let’s dive right in :)

First off let’s just review what a story structure is :

a story is the backbone of the story, the skeleton if you will. It hold the entire story together.

the structure in which you choose your story will effectively determine how you create drama and depending on the structure you choose it should help you align your story and sequence it with the conflict, climax, and resolution.

1. Freytag's Pyramid

this first story structure i will be talking about was named after 19th century German novelist and playwright.

it is a five point structure that is based off classical Greek tragedies such as Sophocles, Aeschylus and Euripedes.

Freytag's Pyramid structure consists of:

Introduction: the status quo has been established and an inciting incident occurs.

Rise or rising action: the protagonist will search and try to achieve their goal, heightening the stakes,

Climax: the protagonist can no longer go back, the point of no return if you will.

Return or fall: after the climax of the story, tension builds and the story inevitably heads towards...

Catastrophe: the main character has reached their lowest point and their greatest fears have come into fruition.

this structure is used less and less nowadays in modern storytelling mainly due to readers lack of appetite for tragic narratives.

2. The Hero's Journey

the hero's journey is a very well known and popular form of storytelling.

it is very popular in modern stories such as Star Wars, and movies in the MCU.

although the hero's journey was inspired by Joseph Campbell's concept, a Disney executive Christopher Vogler has created a simplified version:

The Ordinary World: The hero's everyday routine and life is established.

The Call of Adventure: the inciting incident.

Refusal of the Call: the hero / protagonist is hesitant or reluctant to take on the challenges.

Meeting the Mentor: the hero meets someone who will help them and prepare them for the dangers ahead.

Crossing the First Threshold: first steps out of the comfort zone are taken.

Tests, Allie, Enemies: new challenges occur, and maybe new friends or enemies.

Approach to the Inmost Cave: hero approaches goal.

The Ordeal: the hero faces their biggest challenge.

Reward (Seizing the Sword): the hero manages to get ahold of what they were after.

The Road Back: they realize that their goal was not the final hurdle, but may have actually caused a bigger problem than before.

Resurrection: a final challenge, testing them on everything they've learned.

Return with the Elixir: after succeeding they return to their old life.

the hero's journey can be applied to any genre of fiction.

3. Three Act Structure:

this structure splits the story into the 'beginning, middle and end' but with in-depth components for each act.

Act 1: Setup:

exposition: the status quo or the ordinary life is established.

inciting incident: an event sets the whole story into motion.

plot point one: the main character decided to take on the challenge head on and she crosses the threshold and the story is now progressing forward.

Act 2: Confrontation:

rising action: the stakes are clearer and the hero has started to become familiar with the new world and begins to encounter enemies, allies and tests.

midpoint: an event that derails the protagonists mission.

plot point two: the hero is tested and fails, and begins to doubt themselves.

Act 3: Resolution:

pre-climax: the hero must chose between acting or failing.

climax: they fights against the antagonist or danger one last time, but will they succeed?

Denouement: loose ends are tied up and the reader discovers the consequences of the climax, and return to ordinary life.

4. Dan Harmon's Story Circle

it surprised me to know the creator of Rick and Morty had their own variation of Campbell's hero's journey.

the benefit of Harmon's approach is that is focuses on the main character's arc.

it makes sense that he has such a successful structure, after all the show has multiple seasons, five or six seasons? i don't know not a fan of the show.

the character is in their comfort zone: also known as the status quo or ordinary life.

they want something: this is a longing and it can be brought forth by an inciting incident.

the character enters and unfamiliar situation: they must take action and do something new to pursue what they want.

adapt to it: of course there are challenges, there is struggle and begin to succeed.

they get what they want: often a false victory.

a heavy price is paid: a realization of what they wanted isn't what they needed.

back to the good old ways: they return to their familiar situation yet with a new truth.

having changed: was it for the better or worse?

i might actually make a operate post going more in depth about dan harmon's story circle.

5. Fichtean Curve:

the fichtean curve places the main character in a series of obstacles in order to achieve their goal.

this structure encourages writers to write a story packed with tension and mini-crises to keep the reader engaged.

The Rising Action

the story must start with an inciting indecent.

then a series of crisis arise.

there are often four crises.

2. The Climax:

3. Falling Action

this type of story telling structure goes very well with flash-back structured story as well as in theatre.

6. Save the Cat Beat Sheet:

this is another variation of a three act structure created by screenwriter Blake Snyder, and is praised widely by champion storytellers.

Structure for Save the Cat is as follows: (the numbers in the brackets are for the number of pages required, assuming you're writing a 110 page screenplay)

Opening Image [1]: The first shot of the film. If you’re starting a novel, this would be an opening paragraph or scene that sucks readers into the world of your story.

Set-up [1-10]. Establishing the ‘ordinary world’ of your protagonist. What does he want? What is he missing out on?

Theme Stated [5]. During the setup, hint at what your story is really about — the truth that your protagonist will discover by the end.

Catalyst [12]. The inciting incident!

Debate [12-25]. The hero refuses the call to adventure. He tries to avoid the conflict before they are forced into action.

Break into Two [25]. The protagonist makes an active choice and the journey begins in earnest.

B Story [30]. A subplot kicks in. Often romantic in nature, the protagonist’s subplot should serve to highlight the theme.

The Promise of the Premise [30-55]. Often called the ‘fun and games’ stage, this is usually a highly entertaining section where the writer delivers the goods. If you promised an exciting detective story, we’d see the detective in action. If you promised a goofy story of people falling in love, let’s go on some charmingly awkward dates.

Midpoint [55]. A plot twist occurs that ups the stakes and makes the hero’s goal harder to achieve — or makes them focus on a new, more important goal.

Bad Guys Close In [55-75]. The tension ratchets up. The hero’s obstacles become greater, his plan falls apart, and he is on the back foot.

All is Lost [75]. The hero hits rock bottom. He loses everything he’s gained so far, and things are looking bleak. The hero is overpowered by the villain; a mentor dies; our lovebirds have an argument and break up.

Dark Night of the Soul [75-85-ish]. Having just lost everything, the hero shambles around the city in a minor-key musical montage before discovering some “new information” that reveals exactly what he needs to do if he wants to take another crack at success. (This new information is often delivered through the B-Story)

Break into Three [85]. Armed with this new information, our protagonist decides to try once more!

Finale [85-110]. The hero confronts the antagonist or whatever the source of the primary conflict is. The truth that eluded him at the start of the story (established in step three and accentuated by the B Story) is now clear, allowing him to resolve their story.

Final Image [110]. A final moment or scene that crystallizes how the character has changed. It’s a reflection, in some way, of the opening image.

(all information regarding the save the cat beat sheet was copy and pasted directly from reedsy!)

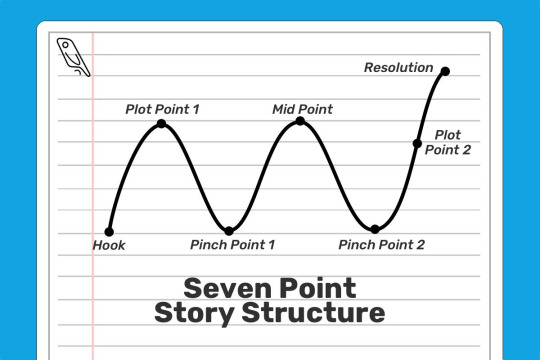

7. Seven Point Story Structure:

this structure encourages writers to start with the at the end, with the resolution, and work their way back to the starting point.

this structure is about dramatic changes from beginning to end

The Hook. Draw readers in by explaining the protagonist’s current situation. Their state of being at the beginning of the novel should be in direct contrast to what it will be at the end of the novel.

Plot Point 1. Whether it’s a person, an idea, an inciting incident, or something else — there should be a "Call to Adventure" of sorts that sets the narrative and character development in motion.

Pinch Point 1. Things can’t be all sunshine and roses for your protagonist. Something should go wrong here that applies pressure to the main character, forcing them to step up and solve the problem.

Midpoint. A “Turning Point” wherein the main character changes from a passive force to an active force in the story. Whatever the narrative’s main conflict is, the protagonist decides to start meeting it head-on.

Pinch Point 2. The second pinch point involves another blow to the protagonist — things go even more awry than they did during the first pinch point. This might involve the passing of a mentor, the failure of a plan, the reveal of a traitor, etc.

Plot Point 2. After the calamity of Pinch Point 2, the protagonist learns that they’ve actually had the key to solving the conflict the whole time.

Resolution. The story’s primary conflict is resolved — and the character goes through the final bit of development necessary to transform them from who they were at the start of the novel.

(all information regarding the seven point story structure was copy and pasted directly from reedsy!)

i decided to fit all of them in one post instead of making it a two part post.

i hope you all enjoy this post and feel free to comment or reblog which structure you use the most, or if you have your own you prefer to use! please share with me!

if you find this useful feel free to reblog on instagram and tag me at perpetualstories

Follow my tumblr and instagram for more writing and grammar tips and more!

#writing#writing advice#writing tips#original writing#writers on tumblr#writerscommunity#writersconnection#writersofig#writersofinstagram#writings

13K notes

·

View notes

Note

How to make the plot beautyful?

A great question worthy of an equally-great answer: how can we as writers make our plots not just good, but beautiful?

What NOT To Do:

String a bunch of random conflicts together

Start with a clear bad guy & good guy (and maintain that relationship throughout the story)

Create plotholes on purpose (then tell yourself that it adds to the “mystique” or think you’ll answer the question later)

Only create story arcs for the main characters and not the side characters because they’re “not as important”

Ignore your own world’s fictional rules without a good reason

Include subplots that don’t support your main story arc

Rely on an outline to rigidly dictate your story’s plot

What To Do:

Start with a simple, compelling premise

Choose a base plot structure to loosely follow (Freytag’s Pyramid, The Hero’s Journey, Three Act Structure, Dan Harmon's Story Circle, Fichtean Curve, Save the Cat Beat Sheet, Seven-Point Story Structure, etc.)

Set up your beginning with your end (the beginning is the question, the end is the answer)

Think about cause and effect; allow each scene to build off the beginning into the end (ensuring each moves the plot and its clear central conflict)

Including the 5 W’s ( ‘who’, ‘what’, ‘where’, ‘why’ and ‘when’) will give the readers a clear sense of setting and ensure the story is more solid

Most importantly: remember that your plot doesn’t drive your characters, your characters drive your plot. Their development over time with their hardships is what will separate your story from average fair.

Hope this gives you a great idea of where to start!

- Admin M x

#admin m#au fridays#develop a plot#plot#plot creation#plot development#writing tips#how do i write#auideas relaunch#writing prompt#writing prompts#writing inspiration#writing idea#writing ideas#prompts#prompt#idea#ideas#story idea#story ideas#writing concepts#writing quote#writing help

301 notes

·

View notes

Text

Howdy y’all.

After reviving my OG tumblr last summer and getting back into writing (especially fanfic), I decided I wanted to be able to actually start interacting with the writers I follow whose content I enjoy without having all the other stuff from 2010-2014 in the mix... hence, a new blog! I tried the side blog thing but wasn’t a fan... Now I don’t have to worry about a side blog and a main blog. Anyways, I’m E. 30. She/hers. Located in the US. I’m an educator by day and a nerd all the time. Given most of what I read is MCU, Loki, and Linked Universe/Legend of Zelda, expect to see those here, but don’t be surprised if/when it branches out well beyond (I could easily see Arcane being added to the mix, and Vox Machina). I reblog stories I enjoy, writing tips/resources, and other things that seem relevant.

Genres I tend to write for - Hurt/Comfort, Angst, Fluff, sick!fic/injury (probably falls under hurt/comfort but whatever, I’m including them here)... slow burn Friends to lovers? That shit slaps. Characters working through their trauma? Love to see it. Found family? *cue heart eyes emoji*

Writing-wise, I have a big project and then smaller one-shots. For one-shots, I’ll be sharing those as I complete them; however, I tend to write them as ways to help kickstart my brain for my big project... that being said, send me requests so I actually post some stuff I’ve written. Otherwise I’ll hyperfixate on my big project and never post anything else. Which, speaking of…

My big project is a 250,000+ word MCU Loki/OFC story set in an AU where all of the Asgardians on the Statesman escaped from Thanos and the Avengers defeated Thanos pre-snap... in other words, all our faves are still alive, and New Asgard is a thing. ;) It’s a FWB-lovers story with lots of found family and friendship, a dope playlist (I might be biased!), a lot of working through trauma and healing, a healthy dose of hurt/comfort and angst with funny and fluffy moments throughout. The story structure blends Fichtean Curve with In Media Res, so it’s not exactly linear... The ending and the beginning closely intertwine throughout, so to make sure everything lines up plot-wise I’m waiting to actually share it on AO3 until it’s finished. Each chapter has a song with it and a TON of work has gone into what songs go with what chapters (which has a tie-in to the plot but I’ll hold of on saying why because spoilers…) Once I start sharing it on AO3, I’ll also post little snippets and inspiration stuff here as well (Honestly I might start this stuff sooner, since I have been working on this since August 2021 and I’m super proud of it!!) I have started sharing snippets here! See the links below (in story order):

I’m Still Not Sure What I Stand For

The Sky Turned Black

Can You Feel It Now?

I Just Wanna Lose Myself With You

On AO3, you can find me as @use_your_telescope

Edit 12/21/22: updated age/dates/other miscellaneous details because holy Jesus I’ve been working on this story for OVER A YEAR OF MY LIFE (shoutout to ADHD for making that a miracle) (but also I am fucking obsessed with this fictional couple so send help)

6 notes

·

View notes