#fermentation brine

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Doing a "perpetual pickle" jar by adding fresh cucumbers and salt to an already established, active dill pickle brine.

I started with some slightly sad dill cucumbers from the store, knowing I'd be hitting the farmer's market on the weekend. At the St Norbert Farmer's Market, I scored a big ol' bag of tiny dill cucumbers. The next day, I visited my partner's grandmother who gave us some home-grown pickling cukes too! So I staggered these over about a week.

My personal preference is "half-sour" dills, about 3 days of fermentation, when the flesh looks creamy and opaque, perhaps hints of translucent regions. It's crisp, tastes cucumber-y, but isn't too "juicy" the way a full-sour often is.

I'd extend this project for even longer, but my partner gently reminded me that my pickle cravings often come in waves. I go on a bit of a #picklerampage for a few weeks, then it fades for a while. But now I have lots of brine ready for whenever I want to start again.

#pickles#dill pickles#fermentation#home fermentation#perpetual pickle jar#lactofermentation#food#pickle brine#pickle juice#preserved vegetables#fermented foods#LAB fermentation#wild fermentation#fermentation brine#kosher dills#fermented pickles#cucumbers#home ferments#LAB pickles#pickled cucumbers#perpetual pickle#pickle rampage

0 notes

Text

Fermented Pomegranate Rose Hot Sauce (Vegan)

#vegan#condiments#hot sauce#fermented foods#pomegranate molasses#rosewater#chili#ginger#cardamom#cinnamon#brine#caraway seeds#edible flowers#rose

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

New batch of pickles now underway! I did decide to cut the bigger Brussels sprouts in half, and threw the small ones in whole.

Those ended up filling less of the airlock lid Kilner jar than expected, so time for another illustration of how peeling will cover a multitude of produce sins.

I actually ended up grabbing another of those big carrots too, and cut them fairly chunky to go with the theme. These are not going to be nicely sandwich sliced pickles already.

Seasonings this time: my standard bay leaf-mustard seed-mixed peppercorn combo and a couple of large cloves of garlic--plus, this time I decided to try a few lightly crushed juniper berries in there, for variety. I didn't use much juniper because the taste can get pretty strong. It does go well with pepper and bay leaves in Weinkraut, though, which is what made me think to try some in these.

Top it up with water, weigh the jar to add 3% salt in, and we should be set.

I finished that off with a spare already-pickled homegrown chili, and a piece of cabbage leaf out of the same previous batch as a cap on top to help keep anything else from floating up around the edges around the pickling weight. That's why this jar is already looking a little cloudy at the top. It was there, and if anything should help act as a starter to get the fermentation kicked off.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

my brain is like kombucha and gay pirates is the SCOBY that ferments all my thoughts

#ofmd#txt#j#mine#og#hi i just woke up and have to go to work#and i am very emotionally drained by a lot of things going on in my life#so more and more i am pickling my brain in gay pirates#fermenting. marinating. brining.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

I keep seeing videos on TikTok of people trying to eat surstromming and they’re fighting for their lives just trying to get the can open Swedish people what is going onnnnn

#the few Swedish people in the comments are always like ‘you have to open it underwater and then wash the brine off’ dude what is the point..#also people being like ‘you eat it with boiled potatoes and sour cream’ 😭#just……#also why are the cans bulging like I know it’s fermented but nooooo is that not botulism???

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#I don’t mean like the shelf jar pickle brine I mean like the refrigerdate jar pickle brine#like the fermented pickle brine#iykyk

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"EASY TO OPEN!" Not noticeably, compared to other jars I've encountered. But, go off Felix.

Shame I don't have the before pictures anymore, and can't point to them on my old blog. But, this is the batch of mixed pickles which turned out mostly cabbage, with a handful of standard round red radishes we had thrown in because it seemed worth a try.

(With what was left transferred over into another saved pickle jar, to free up the airlock lid one they were made in.)

While I was fully expecting most of the color to leach out of those radish skins, I really did NOT think it was enough pigment to turn the whole jar so pink.

One of the bleached-out radish halves in question , with a piece of pink onion--and on the right, a chunk of Barbie cabbage.

The color of the carrot slices barely even stands out, in that sea of pinkness. Appearance aside, this turned out to be one of the best tart, garlicky, slightly hot batches of pickles that I have made so far.

So, if you really want some brine pickles that shade of pink, just throw in some of these babies:

It wouldn't even necessarily take that many. Not nearly as potent as beets or red cabbage pigment, but there seems to be more than enough in that thin outer skin layer.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

obsessed with making pickles by just putting cut veggies into pickle brine from which I've already eaten all the pickles. this is my pickle cycle.

#petchyposting#made one jar where i made the brine out of the fermented radish brine + some vinegar. it was v good

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Discover the Bold Flavor of Fermented Hot Sauce: Wild Brine Probiotic Hot Sauce in Dubai

In the bustling culinary scene of Dubai, food lovers are always looking for bold flavors and unique condiments. Among the growing trends, Fermented Hot Sauce has been spotlighted for its distinct taste and health benefits. If you're looking for a premium option, the Wild Brine Fermented Hot Sauce stands out. Known for its authentic fermentation process and rich probiotic content, this sauce isn't just about heat—it's about flavor, health, and culinary creativity.

What Makes Fermented Hot Sauce Unique?

Unlike regular hot sauces, Fermented Hot Sauce undergoes a natural fermentation process. This not only enhances its flavor but also introduces gut-friendly probiotics, making it a healthier choice. Fermentation breaks down the natural sugars in peppers, creating a tangy, umami-rich profile that standard sauces simply can't match.

Introducing Wild Brine Fermented Hot Sauce

The Wild Brine Sauce is a perfect blend of spice, tang, and depth. Crafted with carefully selected peppers and aged through traditional fermentation methods, this sauce delivers a unique balance of heat and flavor. Whether you're spicing up tacos, marinating meats, or drizzling it over scrambled eggs, the Wild Brine Sauce transforms any dish into a culinary masterpiece.

Health Benefits of Probiotic Hot Sauce

One of the standout features of Wild Brine Sauce is its probiotic content. As a Probiotic Hot Sauce, it promotes gut health, improves digestion, and boosts your immune system. Unlike heavily processed sauces, this fermented variant retains live probiotics, ensuring you get both flavor and health benefits in every drop.

Why Choose Wild Brine Hot Sauce in Dubai?

Dubai’s diverse food culture demands condiments that can complement a wide range of dishes. Whether you're enjoying shawarma, grilled meats, or vegan bowls, Wild Brine Hot Sauce fits seamlessly into any cuisine. Plus, with its availability online, getting your hands on this tangy delight has never been easier.

How to Use Wild Brine Fermented Hot Sauce

Tacos & Burritos: Add a splash for an extra kick.

Grilled Meats: Use it as a marinade for smoky flavors.

Salads: Mix it with dressings for a tangy twist.

Breakfast Favorites: Drizzle over eggs or avocado toast.

Where to Buy Hot Sauce in Dubai?

Looking to add this fiery delight to your pantry? You can easily purchase Wild Brine Fermented Hot Sauce online through tabchilli.com. Enjoy quick delivery and bring home the magic of fermented flavor.

Conclusion:

Whether you're a food enthusiast or a health-conscious eater, the Wild Brine Probiotic Hot Sauce is a must-have in your kitchen. Packed with probiotics, bold flavors, and culinary versatility, it’s more than just a condiment—it's an experience.

0 notes

Text

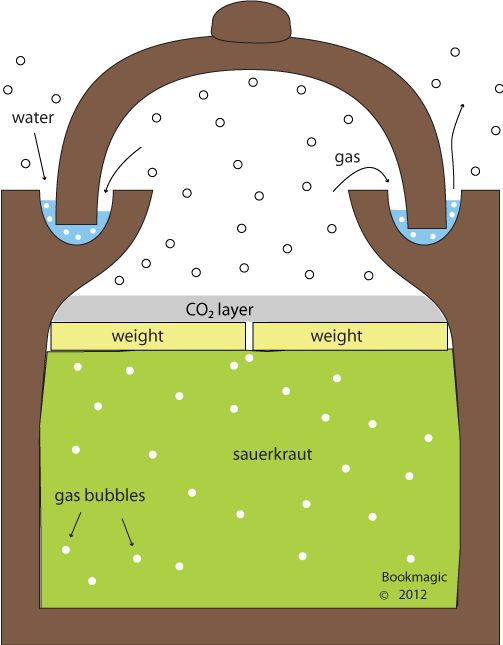

This is a water-seal stoneware crock. The design is ancient.

It is, essentially, a large ceramic vessel that you put vegetables and sometimes brine into. To prevent spoilage, you place those ceramic weights on top of whatever food is in the crock, and that keeps them weighted down, below the level of the water. Because fermentation creates gases, most crocks have a "water groove" in them. The lid sits in the groove, which allows air to escape but not come in. Because fermentation creates gas, the interior of the crock is positive-pressure, and because the gas created is almost entirely carbon dioxide, it's a low-oxygen environment that additionally helps prevent spoilage.

And all this would be pointless without lactobacillus, the bacteria that chomp down on the vegetables you put into the crock. They're anaerobic, which means totally fine without oxygen, and they produce an environment that's inhospitable to most other organisms. The main things they produce are CO2, which means no oxygen for other bacteria, and lactic acid, which makes the fermented thing sour and also decreases the pH low enough that many other bacteria cannot survive. They tolerate high levels of salt, which kill yet more competitor bacteria. It ends up being a really really good way to keep food from going off.

Our ancestors figured this out thousands of years ago without knowing what bacteria were. This general ceramic design has been in use around the world in virtually every place that had ceramics, salt, and too much cabbage or cucumbers that was going to rot if they didn't do something about it. It's thousands of years old, so old that it gets hard to interpret the evidence of the ceramics.

And I have crocks like this in my kitchen, where I make my own ferments, and I always think about how beautiful and elegant it all is, and how this was probably invented hundreds of times as people converged on something that Just Works.

(I do have pH testing strips though.)

12K notes

·

View notes

Text

You might not think that the dead of winter, on whatever day it is right now, is the best possible time to enjoy a pickle. That's ridiculous. It is always the best possible time to enjoy a pickle, but especially now. Brine-infused fermented vegetables are one of the greatest inventions of the human race.

Regardless of culture, pickled food is part of it. Ancient titans got, as the modern vernacular would put it, "mad snacky" all the time. Whether working for landlords in a fiefdom, or working for landlords in a modern market-based economy, pickles helped keep them going long enough to pop your ungrateful ass out.

Now, as you walk through the grocery store with an insanely high density of calories available to you, you pass up these pickles for "other food" that you "need." Not enjoying them is to spit in the face of your ancestors, who struggled to stretch their valuable produce in order to survive the winter.

So take it from me and not at all the Pickle Council of North America, whose innovative advertorial campaign is being run by an absolute but mysterious genius. Pick up some fermented fruit or vegetables today, share them with your family and friends, and then buy some more. Because if you stop buying this stuff, maybe civilization will end, and do you really want that on your conscience?

746 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've been doing lactic acid bacteria (LAB) fermentation for a year now, and I've realised that I really like to keep brine.

One way I use it is in fresh mayonnaise. Here's the general method by Serious Eats, which makes awesome mayonnaise in 2 minutes using an immersion blender (my recipe at the bottom of this post). But that only uses up 1 tablespoon (15 mL) at a time, and I apparently have litres of this.

Thankfully I have wonderful friends who enjoy pickle brine on its own. So they helped me out when I needed to make space in the fridge. Everybody wins!

My recipe:

1 large egg

1 cup sunflower oil

1 Tbsp fermentation brine

1/2 to 1 tsp salt

#food#recipe#mayonnaise#pickle brine#pickle juice#leftover brine#fermentation#sauerkraut#preserved vegetables#lactofermentation#fermented foods#LAB fermentation#pickles#wild fermentation#home fermentation#fermentation brine

0 notes

Text

foods of the Lands Between: spicy prawns · she-crab soup · meat dumplings · pickled veggies · herba tea · sheep's milk cheese · beast blood pancakes · rowa jam tarts

while Elden Ring has a variety of consumable items, most of them are described as being medicinal in nature. I wanted to come up with food that people in the Lands Between might have for actual meals! all of these were inspired directly by in-game items & creatures.

flavor text (hehe) below the cut:

spicy prawns: Widely enjoyed in Liurnia due to the abundance of crayfish, and seasoned with the same fiery spices used to prepare exalted flesh.

she-crab soup: A rich bisque made with fish stock, cream, fortified wine, crab meat, and crab eggs. The roe of giant crabs is particularly prized for use in this dish.

meat dumplings: A staple in the Lands Between made with whatever meat is readily available (springhare, guillemot, and land octopus are common fillings). Methods of preparation vary as much as the meat, and they're sometimes enjoyed fermented or raw.

pickled veggies: Mixed vegetables preserved in a sour brine and stored inside of clay pots. Edible mushrooms and cave moss are frequent additions. They can supposedly be thrown at attackers in a pinch to inflict the [PICKLED] status.

herba tea: A beverage made from herba leaves that have been meticulously steamed, dried, and ground into a fine powder, then whisked into hot water. It can also be steeped from fresh herba, though the powdered form is preferred for both its stronger flavor and ease of storage.

sheep's milk cheese: A blue cheese made from the raw milk of rolling sheep. Creamy and tangy, with a salty rind that tastes of seagrass. Its vibrant veins of mold come from fungi that flourish in Limgrave’s coastal caves.

beast blood pancakes: The blood of beasts makes a handy substitute when fresh eggs are hard to come by. These dense and savory pancakes are often served with buttery marrow from the beast's own bones, plus a hearty dollop of rowa jam.

rowa jam tarts: While red rowa is rather sour and more commonly consumed by animals than people, the golden fruit from the Altus Plateau makes especially sweet preserves that are perfect for use in tarts and other desserts. Such treats are precious things.

#elden ring#food#i was also inspired by dungeon meshi a bit :]#but tbf these dishes are pretty tame because i wanted them to be realistic#i'm sure there's some wild tarnished out there making braised glintstone dragon and arteria leaf pesto tho#cas draws

177 notes

·

View notes

Text

eating salmon: an explanation

lox: thin cuts of salmon (traditionally the fatty belly meat) dry cured with salt, but not smoked. this results in a delicate texture and a very salty taste. lox originated in Scandinavia as a method of preserving fish prior to refrigeration, but the American English word is derived from Yiddish because Jewish delis in New York first popularized it as a bagel topping. since lox is a type of uncooked fish, it is not recommended for pregnant people, immunocompromised people, or seniors, due to the risk of contamination with listeria.

cold-smoked salmon: thin cuts of salmon brined (with less salt than lox) and then smoked below 90 degrees Fahrenheit. results in the same silky texture but a milder, more palatable taste. often called "Nova lox", referring to Nova Scotia but denoting a method of preparation rather than the fish's origin. this is usually what modern Americans are referring to when they use the term "lox". cold-smoking reduces but does not eliminate the risk of listeria.

hot-smoked salmon: salmon brined quickly and then smoked above 120 degrees Fahrenheit. results in a flaky, jerky-liked texture, a hard shiny surface, and a smoky flavor. (as a West-coaster, this is my preferred style!) hot-smoking eliminates listeria during the cooking process, but salmon can be recontaminated during the processing/packaging process if the facility is not sanitary. (really, this is true of all foods- vegetables, dairy products, etc).

salmon candy: a traditional Pacific Northwest hot-smoked salmon recipe where the brine is sweetened with brown sugar, and the smoked fish is glazed with a sauce containing birch or maple syrup.

salmon jerky: cured salmon hot-smoked for longer than usual or processed in a dehydrator until it is tough and chewy.

gravlax: a traditional Scandinavian raw salmon recipe where the brine contains sugar and dill. historically buried in the ground and lightly fermented. sometimes it is still pressed to give it a dense texture.

kippered salmon: thicker cuts of brined salmon hot-smoked above 150 degrees Fahrenheit. results in a texture similar to baked salmon.

salmon sushi/sashimi: completely raw fresh salmon. this didn't exist in traditional Japanese cuisine, where salmon was always cooked, possibly because the local wild salmon had a high burden of parasitic worms (anasakis nematodes). Norwegian fish sellers convinced them to try farmed Atlantic salmon raw in the 80s, and it really took off.

poached salmon: salmon cooked on the stove while submerged in liquid (often white wine with lemon). results in a moist, soft, cooked fish with a pale color. can be bland without sauce.

baked salmon: salmon cooked in an oven, often wrapped in aluminum foil with seasonings to retain moisture and flavor. can result in perfect, flaky fish (as long as you don't overcook it).

dishwasher salmon: look, sometimes white people wrap salmon in aluminum foil like they're going to bake it and then poach it in their dishwasher instead. this can work but is stupid because the temperature dishwashers run at isn't standardized, so you have no control over the process and it's easy to over or undercook.

pan-fried salmon: salmon cooked in oil on a stovetop. I've never done this and frankly it sounds wrong, but I bet it makes the skin crunchy.

broiled salmon: salmon cooked under a broiler. as with all broiled foods, you will have to stare at it the whole time or it will burn to a crisp while your back is turned. results in a caramelized exterior.

grilled salmon: to grill salmon people often put it on a Western redcedar plank pre-soaked in water, which supposedly infuses the salmon with a smoky, aromatic flavor while it cooks. I've seen the technique variously credited to the Haida, the Salish, and the Chinook. it seems to be a modern variation of the traditional "salmon on a stick" style of slow-cooking salmon by spearing it on branches and leaning it over the coals of an above-ground pit fire.

deep-fried salmon: this sounds absolutely awful but I simply cannot stop thinking about it

462 notes

·

View notes

Text

[ID: A circle of overlapping semi-circular bright pink pickles arranged on a plate, viewed from a low angle. End ID]

مخلل اللفت / Mukhallal al-lifit (Pickled turnips)

The word "مُخَلَّل" ("mukhallal") is derived from the verb "خَلَّلَ" ("khallala"), meaning "to preserve in vinegar." "Lifit" (with diacritics, Levantine pronunciation: "لِفِتْ"), "turnip," comes from the root "ل ف ت", which produces words relating to being crooked, turning aside, and twisting (such as "لَفَتَ" "lafata," "to twist, to wring"). This root was being used to produce a word meaning "turnip" ("لِفْتْ" "lift") by the 1000s AD, perhaps because turnips must be twisted or wrung out of the ground.

Pickling as a method of preserving produce so that it can be eaten out of season is of ancient origin. In the modern-day Levant, pickles (called "طَرَاشِيّ" "ṭarāshiyy"; singular "طُرْشِيّ" "ṭurshiyy") make up an important culinary category: peppers, carrot, olives, eggplant, cucumber, cabbage, cauliflower, and lemons are preserved with vinegar or brine for later consumption.

Pickled turnips are perhaps the most commonly consumed pickles in the Levant. They are traditionally prepared during the turnip harvest in the winter; in the early spring, once they have finished their slow fermentation, they may be added to appetizer spreads, served as a side with breakfast, lunch, or dinner, eaten on their own as a snack, or used to add pungency to salads, sandwiches, and wraps (such as shawarma or falafel). Tarashiyy are especially popular among Muslim Palestinians during the holy month of رَمَضَان (Ramaḍān), when they are considered a must-have on the إِفْطَار ("ʔifṭār"; fast-breaking meal) table. Pickle vendors and factories will often hire additional workers in the time leading up to Ramadan in order to keep up with increased demand.

In its simplest instantiation, mukhallal al-lifit combines turnips, beetroot (for color), water, salt, and time: a process of anaerobic lacto-fermentation produces a deep transformation in flavor and a sour, earthy, tender-crisp pickle. Some recipes instead pickle the turnips in vinegar, which produces a sharp, acidic taste. A pink dye (صِبْغَة مُخَلَّل زَهْرِي; "ṣibgha mukhallal zahri") may be added to improve the color. Palestinian recipes in particular sometimes call for garlic and green chili peppers. This recipe is for a "slow pickle" made with brine: thick slices of turnip are fermented at room temperature for about three weeks to produce a tangy, slightly bitter pickle with astringency and zest reminiscent of horseradish.

Turnips are a widely cultivated crop in Palestine, but, though they make a very popular pickle, they are seldom consumed fresh. One Palestinian dish, mostly prepared in Hebron, that does not call for their fermentation is مُحَشّي لِفِتْ ("muḥashshi lifit")—turnips that are cored, fried, and stuffed with a filling made from ground meat, rice, tomato, and sumac or tamarind. In Nablus, tahina and lemon juice may be added to the meat and rice. A similar dish exists in Jordan.

Turnips produced in the West Bank are typically planted in open fields (as opposed to in or under structures such as plastic tunnels) in November and harvested in February, making them a fall/winter crop. Because most of them are irrigated (rather than rain-fed), their yield is severely limited by the Israeli military's siphoning off of water from Palestine's natural aquifers to settlers and their farms.

Israeli military order 92, issued on August 15th, 1967 (just two months after the order by which Israel had claimed full military, legislative, executive, and judicial control of the West Bank on June 7th), placed all authority over water resources in the hands of an Israeli official. Military order 158, issued on November 19th of the same year, declared that no one could establish, own, or administer any water extraction or processing construction (such as wells, water purification plants, or rainwater collecting cisterns) without a new permit. Water infrastructure could be searched for, confiscated, or destroyed at will of the Israeli military. This order de facto forbid Palestinians from owning or constructing any new water infrastructure, since anyone could be denied a permit without reason; to date, no West Bank Palestinian has ever been granted a permit to construct a well to collect water from an aquifer.

Nearly 30 years later, the Interim Agreement on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip (also called the Oslo II Accord or the Taba Agreement), signed by Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in 1995, officially granted Israel the full control over water resources in occupied Palestine that it had earlier claimed. The Argreement divided the West Bank into regions of three types—A, B, and C—with Israel given control of Area C, and the Palestinian Authority (PA) supposedly having full administrative power over Area A (about 3% of the West Bank at the time).

In fact, per article 40 of Annex 3, the PA was only allowed to administer water distribution in Area A, so long as their water usage did not exceed what had been allocated to them in the 1993 Oslo Accord, a mere 15% of the total water supply: they had no administrative control over water resources, all of which were owned and administered by Israel. This interim agreement was to be returned to in permanent status negotiations which never occurred.

The cumulative effect of these resolutions is that Palestinians have no independent access to water: they are forbidden to collect water from underground aquifers, the Jordan River, freshwater springs, or rainfall. They are, by law and by design, fully reliant on Israel's grid, which distributes water very unevenly; a 2023 report estimated that Israeli settlers (in "Israel" and in the occupied West Bank) used 3 times as much water as Palestinians. Oslo II estimations of Palestinians' water needs were set at a static number of million cubic meters (mcm), rather than an amount of water per person, and this number has been adhered to despite subsequent growth in the Palestinian population.

Palestinians who are connected to the Israeli grid may open their taps only to find them dry (for as long as a month at a time, in بَيْت لَحْم "bayt laḥm"; Bethlehem, and الخَلِيل "al-khalīl"; Hebron). Families rush to complete chores that require water the moment they discover the taps are running. Those in rural areas rely on cisterns and wells that they are forbidden to deepen; new wells and reservoirs that they build are demolished in the hundreds by the Israeli military. Water deficits must be made up by paying steep prices for additional tankards of water, both through clandestine networks and from Israel itself. As climate change makes summers hotter and longer, the crisis worsens.

By contrast, Israeli settlers use water at will. Israel, as the sole authority over water resources, has the power to transfer water between aquifers; in practice, it uses this authority to divert water from the Jordan River basin, subterranean aquifers, and بُحَيْرَة طَبَرِيَّا ("buḥayrat ṭabariyyā"; Lake Tiberias) into its national water carrier (built in 1964), and from there to other regions, including the Negev Desert (south of the West Bank) and settlements within the West Bank.

Whenever Israel annexes new land, settlers there are rapidly given access to water; the PA, however, is forbidden to transport water from one area of the West Bank to another. Israel's control over water resources is an important part of the settler colonial project, as access to water greatly influences the desirability of land and the expected profit to be gained through its agricultural exports.

The result of the diversion of water is to increase the salinity of the Eastern Aquifer (in the West Bank, on the east bank of the Jordan River) and the remainder of the Jordan that flows into the West Bank, reducing the water's suitability for drinking and irrigation; in addition, natural springs and wells in Palestine have run dry. In this environment, water for drinking and watering crops and livestock is given priority, and many Palestinians struggle to access enough water to shower or wash clothing regularly. In extreme circumstances, crops may be left for dead, as Palestinian farmers instead seek out jobs tending Israeli fields.

Some areas in Palestine are worse off in this regard than others. Though water can be produced more easily in the قَلْقِيلية (Qalqilya), طُولْكَرْم (Tulkarm) and أَرِيحَا ("ʔarīḥā"; Jericho) Districts than in others, the PA is not permitted to transfer water from these areas to areas where water is scarcer, such as the Bethlehem and Al-Khalil Districts. In Al-Khalil, where almost a third of Palestinian acreage devoted to turnips is located [1], and where farming families such as the Jabars cultivate them for market, water usage averaged just 51 liters per person per day in 2020—compare this to the West Bank Palestinian average of 82.4 liters, the WHO recommended daily minimum of 100 liters, and the Israeli average of 247 liters per person per day.

As Israeli settlement גִּבְעַת חַרְסִינָה (Givat Harsina) encroached on Al-Khalil in 2001, with a subdivision being built over the bulldozed Jabar orchard, the Jabars reported settlers breaking their windows, destroying their garden, throwing rocks, and holding rallies on the road leading to their house. In 2010, with the growth of the קִרְיַת־אַרְבַּע (Kiryat Arba) settlement (officially the parent settlement of Givat Harsina), the Jabars' entire irrigation system was repeatedly torn out, with the justification that they were stealing water from the Israeli water authority; the destruction continued into 2014. Efforts at connecting and expanding Israeli settlements in the Bethlehem area continue to this day.

Thus we can see that water deprivation is one tool among many used to drive Palestinians from their land; and that it is connected to a strategy of rendering agriculture impossible or unprofitable for them, forcing them into a state of dependence on the Israeli economy.

Turnips, as well as cabbage and chili peppers, are also grown in the village of وَادِي فُوقِين (Wadi Fuqin), west of Bethlehem. In 2014, Israel annexed about 1,250 acres of land in Wadi Fuqin, or a third of the village's land, "effectively [ruling] out development of the village and its use of this land for agriculture." Most of this land lies immediately to the west of a group of settlements Israel calls גּוּשׁ עֶצְיוֹן ("Gush Etzion"; Etzion Bloc). Building here would link several non-contiguous Israeli settlements with each other and with القدس (Al-Quds; "Jerusalem"), hemming Palestinians of the region in on all sides (many main roads through Israeli settlements cannot be used by anyone with a Palestinian ID). [2] PLO executive committee member Hanan Ashrawi said that the annexation, which was carried out "[u]nder the cover of [Israel's] latest campaign of aggression in Gaza," "represent[ed] Israel’s deliberate intent to wipe out any Palestinian presence on the land".

This, of course, was not the beginning of this strategy: untreated sewage from Gush Etzion settlements had been contaminating crops, springs, and groundwater in Wadi Fuqin since 2006, which also saw nearly 100 acres of Palestinian land annexed to allow for expansion of the Etzion Bloc.

All of this has obviously had an effect on Palestinian agriculture. A 1945–6 British survey of vegetable production in Palestine found that 992 dunums were devoted to Arab turnip production (954 irrigated and 38 rain-fed; no turnip production was attributed to Jewish settlers). A March 1948 UN report claimed that "[i]n most districts the markets are well-supplied with all the common winter vegetables—cabbages, cauliflowers, lettuce and spinach; carrots, turnips and and beets; beans and peas; green onions, eggplants, marrows and tomatoes." By 2009, however, the area given to turnips in Palestine had fallen to 918 dunums. Of these, 864 dunums were irrigated and 54 rain-fed. This represents an increase in unirrigated turnips (5.8%, up from 3.9%) that is perhaps related to difficulty in obtaining sufficient water.

Meanwhile, Israel profits from its restriction of Palestinian agriculture; it is the largest exporter of turnips in West Asia (I found no data for turnip exports from Palestine after 1922, suggesting that the produce is all for local consumption).

The pattern that Ashrawi called out in 2014 continued in 2023, as Israel's genocide in Gaza occurs alongside the continued and escalating killing and expulsion of West Bank Palestinians. The 2014 annexations, which represented the largest land grab for over 30 years and which appeared to institute a new era of state policy, have been followed up in subsequent years with more land claims and settlement-building.

Israeli military and settler raids and massacres in the West Bank, which had already killed 248 in 2023 before the حَمَاس (Hamas) October 7 offensive had taken place, accelerated after the attack, with forced expulsions of Palestinians (including Bedouin Arabs), and harassment, raids, kidnappings, and torture of Palestinians by a military armed with rifles, tanks, and drones. This violence has been opposed by armed resistance groups, who defend refugee camps from military raids with strategies including the use of improvised explosives.

Support Palestinian resistance by buying an e-sim for distribution in Gaza; donating to help two Gazans receive medical care; or donating to help a family leave Gaza.

[1] 918 dunums were devoted to turnips according to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) report for 2009; the 2008 PCBS report attributes 253 dunums of turnip cultivation to Al-Khalil ("Hebron") for 2006–7.

[2] Today, Gush Etzion is connected to Al-Quds by an underground road that runs beneath the Palestinian Christian town of بَيتْ جَالَا (Bayt Jala).

Ingredients:

Makes 2 1-liter mason jars.

500g (4 medium) turnips

1 beetroot

1 medium green chili pepper (فلفل حار خضرة), halved

2 small cloves garlic, peeled

1 liter (4 cups) distilled or filtered water

25g coarse sea salt (or substitute an equivalent weight of any salt without iodine)

Some brining recipes for lifit call for the addition of a spoonful of sugar. This will increase the activity of lactic-acid-producing bacteria at the beginning of the fermentation, producing a quicker fermentation and a different, sourer flavor profile.

Instructions:

1. Clean two large mason jars thoroughly in hot water (there is no need to sterilize them).

2. Scrub vegetables thoroughly. Cut the top (root) and bottom off of each turnip. Cut each turnip in half (from root end to bottom), and then in 1 cm (1/2") slices (perpendicular to the last cut). Prepare the beetroot the same way.

If you need your pickles to be finished sooner, cut the turnips into thinner slices, or into thick (1/2") baton shapes; these will need to be fermented for about a week.

3. Arrange turnip and beet slices so that they lie flat in your jars. Add garlic and peppers.

4. Whisk salt into water until dissolved and pour over the turnips until they are fully submerged. Seal with the jar's lid and leave in a cool place, or the refrigerator, for 20–24 days.

The amount of brine that you will need to cover the top of the vegetables will depend on the shape of your jar. If you add more water, make sure that you add more salt in the same ratio.

294 notes

·

View notes

Text

I bottled two different batches of fermented hot sauce, a batch of ghost and one of habanero. I've yet to try either but I'm curious how it compares to my usual method. It's the same exact ingredients and process but fermented in a brine for two weeks before blending with vinegar and then boiling to stop the fermentation.

53 notes

·

View notes