#fer muratori

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Melodramas nórdicos

[Edvard Grieg y Jean Sibelius, los dos compositores nórdicos más célebres]

La Fundación Juan March presenta en su ciclo anual de ‘Melodramas’ una serie de obras de Edvard Grieg y Jean Sibelius, las del compositor finlandés jamás vistas en escena en España

La música alemana dominó los géneros instrumentales durante todo el siglo XIX. La concepción germánica de sinfonías, sonatas y cualquier tipo de obras camerísticas de raigambre clásica fue central y dominante en toda la Europa romántica. Pero el Romanticismo había despertado también los sentimientos de identidad nacional de los individuos, lo que tuvo consecuencias políticas bien conocidas (entre otras, la unificación de Italia y Alemania y la disolución de los grandes imperios, que sólo se confirmaría tras la Gran Guerra), y obviamente afectó al ámbito cultural. Así, en la periferia del continente nacieron escuelas artísticas propias, nacionales, que tuvieron en la música uno de sus principales cauces de expresión.

Noruega y Finlandia se pasaron todo el siglo XIX dependiendo política y culturalmente de otros países. Noruega primero de Dinamarca y desde 1814 de Suecia, de quien no logró independizarse hasta 1906; Finlandia, hasta 1809 de Suecia y después de Rusia, hasta la independencia, lograda, tras sangrienta guerra civil, en 1917. Reprimidos políticamente, los anhelos identitarios se expresaron fundamentalmente en la literatura y en la música. Edvard Grieg (1843-1907) y Jean Sibelius (1865-1957) representan para Noruega y Finlandia, respectivamente, la expresión máxima de esa voz nacional en música.

Habría que poner muchos matices a esa tesis. En realidad, ambos manejaron de manera primordial las formas clásicas. Cierto que Grieg, a pesar de la celebridad de su Concierto para piano, prefirió siempre el ámbito de la canción y de las miniaturas pianísticas, y ahí trató con frecuencia temas y caracteres locales, a menudo inspirados en danzas y canciones propios. Sibelius, y a pesar de que negó siempre implicaciones políticas en su Sinfonía nº2, tomada por los jóvenes patriotas finlandeses como un grito de rebeldía frente a la opresión, trató a menudo con temas de la mitología y las leyendas locales. Pero en realidad la concepción que Sibelius tenía de la sinfonía, el género que lo ha inmortalizado, era puramente musical. Contrariamente a Mahler, que hizo de sus sinfonías un campo de teatro psicológico en el que cabía prácticamente todo, Sibelius buscó siempre la mayor coherencia posible entre unos elementos musicales puramente abstractos. Y eso tiene poco de nacionalista.

Fuera cual fuere el grado de identificación con los medios nacionalistas de sus respectivos países ni Grieg ni Sibelius volcaron sus sentimientos en la ópera. Grieg jamás compuso una, aunque se le conocen intentos de escribir sobre la historia medieval noruega a partir de un libreto de su contemporáneo Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson. Sibelius estrenó en 1907 una operita de apenas 35 minutos y tema también medieval (La doncella de la torre), pero la obra, que estaba en sueco, el idioma materno del compositor por otro lado, no tuvo ninguna trascendencia ni en aquel momento ni después. La mayor vinculación de Grieg con el mundo del teatro le viene por su música incidental para el Peer Gynt de Ibsen, que incluye algunas de sus páginas más célebres. Sibelius compuso bastante música incidental para dramas entre otros de Shakespeare, Strindberg y Maeterlinck.

La Fundación Juan March se ha fijado en cualquier caso en otro tipo de piezas dramáticas, a las que viene dedicando un ciclo específico desde 2016. Son los melodramas, obra en la que el texto hablado alterna o se superpone a música instrumental. A menudo, y para evitar la posible confusión con otras acepciones del término 'melodrama' (entre ellas la que lo identifica con la ópera italiana) se usa la expresión melólogo. Desde el Pygmalion de Rameau, estrenado póstumamente en 1770, que tuvo apreciable éxito en Alemania, la técnica del melodrama fue muy empleada por Jiri Antonin Benda, pero puede hallarse en Mozart (su singspiel incompleto Zaide), Beethoven (Fidelio), Weber (El cazador furtivo) o Berlioz (Lelio), además de dar forma a obras específicamente melológicas (permítaseme el término).

En la exploración de este género poco habitual de las programaciones, la Fundación Juan March ha pasado por el Manfred de Schumann sobre texto de Lord Byron y por obras de Strauss y de Liszt. Este año, le toca el turno a Grieg y Sibelius. Entre el domingo 2 y el miércoles 5 de junio habrá una función diaria (el domingo a las 12, los otros días a las 19.30) en la sede de la fundación (calle Castelló, 77 de Madrid) de un espectáculo que contará con dirección escénica de Ernesto Caballero y escenografía de Paco Azorín y Fer Muratori. María Adánez y Joaquín Notario actuarán como narradores y un cuarteto formado por el pianista Eduardo Fernández, la soprano Svetla Krasteva, la violinista Cecilia Bercovich y el violonchelista Fernando Arias pondrán la música.

Además de una serie de obras pianísticas, que funcionarán como preludio e interludios, podrá escucharse Bergliot Op.42 de Grieg, melodrama a partir de un texto de Bjørnson datado en 1885, una obra de algo menos de veinte minutos de duración, escrita para narrador y piano sobre el drama medieval de la mujer del título, especie de Brunilda noruega, que jura venganza contra un rey traidor responsable de la muerte de su esposo y su hijo. Aunque parece que a Grieg no le convenció demasiado el ciclo del Anillo de Wagner, en su música hay indiscutibles resonancias wagnerianas.

En el caso de Sibelius se han escogido Una huella solitaria y Oh, si hubieras visto, dos obras breves para narrador y piano, La nixe, que es una canción de la Op.57 con una parte recitada (que, es de suponer, hará aquí uno de los actores en lugar de la soprano del elenco) y, finalmente, Noches de celos, la obra más extensa del lote (en torno a los 15 minutos), también con soprano, además del narrador, y acompañamiento de trío con piano. Estas cuatro piezas son estrenos absolutos en España, que se apunta una vez más la Fundación Juan March, institución que mantiene posiblemente la más original e importante programación musical privada del país.

Los conciertos de la fundación son gratis, con entrada libre (y posibilidad de reservar hasta un tercio del aforo), pero además la primera y última función (las de los días 2 y 5) serán retransmitidas por streaming en el canal de la propia fundación (www.march.es/directo) y en YouTube Live. La del día 5 podrá escucharse en directo a través de Radio Clásica de RNE.

[Diario de Sevilla. 27-05-2019]

LISTA DE REPRODUCCIÓN EN SPOTIFY

#edvard grieg#jean sibelius#bjorstjernen bjorson#ibsen#shakespeare#strindberg#maeterlinck#rameau#jiri antonin benda#mozart#beethoven#weber#berlioz#ernesto caballero#paco azorín#fer muratori#maría adánez#joaquín notario#eduardo fernández#svetla krasteva#cecilia bercovich#fernando arias#wagner

1 note

·

View note

Text

- E lo princep respos al almirall: -Ques aço que vos volets que yo hi faça? que si fer yo puch , -volenters ho fare.- Yo , dix lalmirall , quem façats ades venir la filla del rey Manfre, germana de madona la regina Darago, que vos tenits en vostra preso aci el castell del Hou , ab aquelles dones e donzelles qui soes bi sien ; e quem façats lo castell e la vila Discle retre . - E lo princep respos , queu faria volenters. E tantost trames un seu cavaller en terra ab un leny armat, e amena madona la infanta , germana de madona la regina , ab quatre donzelles e dues dones viudes. E lalmirall reebe les ab gran goig e ab gran alegre , e ajenollas, e besa la ma a madona la infanta.

Ramon Muntaner, CRÓNICA CATALANA, p. 221

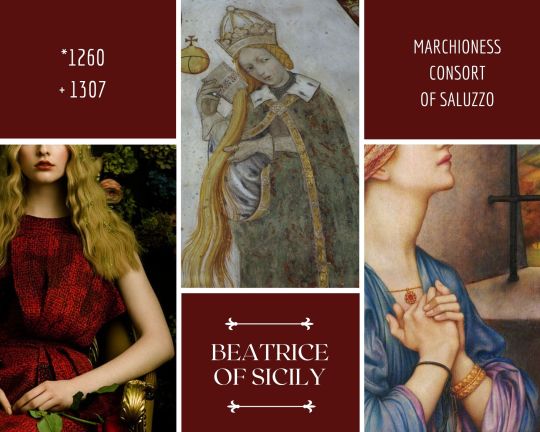

Beatrice was born (probably) in Palermo around 1260. She was the first child and only daughter of Manfredi I of Sicily and his second wife, the Epirote princess Helena Angelina Doukaina (“[…] et idem helenam despoti regis emathie filiam sibi matrimonialiter coppulavit, ex quibus nata fuit Beatrix.”, Bartholomaeus de Neocastro, Historia Sicula, in Giuseppe Del Re, Cronisti e Scrittori sincroni Napoletani editi ed inediti, p. 419). It’s quite plausible the baby had been named after Manfredi’s first wife, Beatrice of Savoy (mother of Costanza, who will later become Queen consort of Aragon and co-regnant of Sicily). The little princess would soon be followed by three brothers: Enrico, Federico and Enzo (also called Anselmo or Azzolino). With three sons, Manfredi must have thought his succession was secured.

Beatrice’s father was one Federico II of Sicily’s many illegitimate children, although born from his most beloved mistress (and possibly fourth and last wife), Bianca Lancia. Since his father’s death in 1250, Manfredi had governed the Kingdom of Sicily on behalf firstly of his (legitimate) half-brother Corrado and, after his death in 1254, of Corrado’s son, Corradino. In 1258, two years prior Beatrice’s birth, Manfredi had been crowned King of Sicily in Palermo’s Cathedral, de facto usurping his half-nephew’s rights.

Like it had happened with Federico, Manfredi was soon opposed by the Papacy, which didn’t approve of the Hohenstaufen’s rule over Sicily (and Southern Italy with it) and the role of the King as the champion of the Ghibellines faction. In 1263, Urban VI managed to convince Charles of Anjou, younger brother of Louis IX the Saint, to present himself as a contender to the Sicilian throne. Three years later, on January 6th 1266, the French duke was crowned King of Sicily by the Pope in Rome, thus overthrowing Manfredi. On February 26th, in Benevento, the usurped King then tried to get back his kingdom by facing Charles in the open field, but failed and lost his life while fighting.

The now widowed Queen Helena had previously fled to Lucera (in Apulia) with her children (Beatrice was now six), her sister-in-law Costanza, and her step-daughter, the illegitimate Flordelis, where she thought they would be safer. When they got news of the disaster of Benevento and Manfredi’s death, they fled to Trani from where they planned to set off to Epirus. The unfortunate party was instead betrayed and handed off to the Angevin. On March 6th night, Helena and the children were taken hostage and later separated. The Queen was sent at first to Lagopesole (in Basilicata) and finally to Nocera Christianorum (now Nocera Inferiore), where she would die still in captivity in 1271.

Enrico, Federico and Enzo were taken to Castel del Monte. Following Corradino’s death in 1268, Manfredi’s young sons (the oldest, Enrico, was just four at the time of his capture) were, to all effects, the rightful heirs to the Sicilian throne. It’s undoubtful Charles must have wanted them gone, or at least forgotten. In 1300 they were moved to Naples, in Castel dell’Ovo (which, at that time, was called San Salvatore a mare), under the order of the new Angevin king, Charles II. According to some sources, Federico and Enzo died there within the short span of a year. As for Enrico, he died alone and miserable in October 1318, he was 56.

As for Beatrice, her fate was more merciful compared to that of her mother and brothers and, for that, she had to thank her sex, which made her harmless in Charles’ eyes (as long as she was left unmarried). After being separated from her family (she will never see them again), the six years old princess was, like her brothers, held captive (although not together) in Castel del Monte. In 1271, she was moved to Naples, in Castel dell’Ovo, under the guardianship of its keeper, a French nobleman called either Landolfo or Radolfo Ytolant. Manfredi’s daughter is mentioned in a rescript of Charles dated March 5th 1272, from which we learn she had been granted at least a maid (“V Marcii xv indictionis. Neapoli. Scriptum est Iustitiario et erario Terre laboris etc. Cum ex computo facto per magistrum rationalem Nicolaum Buccellum etc. cum Landulfo milite castellano castri nostri Salvatoris ad mare de Neapoli pro expensis filie quondam Manfridi Principis Tarentini et damicelle sue. ac filie quondam comitis Iordani et damicelle sue dicto castellano in unc. auri novem et taren. sex de pecunia presentis generalis subventionis residuorum quolibet vel qua canque alia etc. persolvatis. non obstante etc. Recepturus etc.”, Monumenti n. XLIV. in Domenico Forges Davanzati, Dissertazione sulla seconda moglie del re Manfredi e su’ loro figliuoli, p. XLIII-XLIV). Like it had happened with her mother, and unlike her brothers, it appears Beatrice was treated with courtesy and respect. In her misfortune, she could count on the company of a fellow prisoner and distant relative, the daughter of Giordano Lancia d’Agliano, who was her grandmother Bianca Lancia’s cousin and had been a loyal supporter of her father, Manfredi.

On Easter Day of 1282, an anti-Angevin rebellion sparkled in Palermo would soon transform itself into a war to get rid of the so much hated Frenchmen, the so-called War of the Sicilian Vespers. It’s dubious that, close in her prison, Beatrice came to know about it. She might have also been surprised to know that her half-sister, Costanza, had been asked by a delegation of fellow Sicilians to take possession of what was hers by right (the throne) as she was their “naturalis domina”. Her rights were shared with her husband, Pedro III of Aragon, who would personally take part in the war and be rewarded with a joint coronation in November 1282.

For Beatrice, everything changed in 1284. On June 4th, Italian Admiral Ruggero di Lauria, at the service of the Aragonese King (he was also Costanza’s milk brother), defeated the Angevin fleet just offshore from Naples and took Carlo II prisoner. Being in clear superiority, the Sicilians could now demand (among many requests) the release of Princess Beatrice. Carlo’s eldest son and heir, Carlo Martello Prince of Salerno, could nothing other than obliging them. (“Siciliani autem , & omnes faventes Petro Aragonum, incontinenti de ipsorum victoria plurimum exultantes, Nuncios, & Legatos ad quoddam Castrum ex parte Principis direxerunt , ubi quaedam filia quondam Domini Regis Manfredi sub custodia tenebatur , ut dicta filia fine ullo remedio laxaretur , quae statim fuit antedictis Legatis , & Nunciis restituta.”, Anonimo Regiense, Memoriale Potestatum Regiensium. Gestorumque iis Temporibus. Ab anno 1154 usque ad Annum 1290, in Ludovico Antonio Muratori, Rerum Italicarum scriptores ab anno aerae christianae quingentesimo ad millesimumquingentesimum, vol. VIII, p. 1158).

Beatrice, finally free, left Castel dell’Ovo headed for Capri, where the Admiral was waiting for her. She had spent 18 long years in captivity and was now 24. From Capri she reached Sicily, where she was warmly welcomed and with a lot of enthusiasm, to meet her half-sister Costanza.

As the Queen’s closest free relative (both Pedro and Costanza had no interest in asking for Enrico’s release since, as a male, he had more rights than Costanza to inherit the throne), Beatrice had a great political value. At first, Ranieri Della Gherardesca’s name came up. He was the son of that Count Gherardo who had fought together with the unfortunate Corradino (the sisters’ royal cousin), and for that had been beheaded in Naples in 1268 alongside his liege. Finally the perfect candidate was found. Manfredo of Saluzzo was born in 1262 and was the son of Marquis Tommaso I and his wife Luigia of Ceva. Like Beatrice, Manfredo was strongly related to Costanza, specifically, he was her nephew since Tommaso and the Sicilian Queen were half-siblings (they were both Beatrice of Savoy’s children).

The marriage contract between the two is dated July 3rd 1286 and the contracting parties are on one side “la serenissima signora constanza regina dy aragon e dy sicilia e dil ducato de puglia principato di capua” and, on the other side “il marchexe thomas di sa lucio signore de conio una cum mạdona alexia soa moglie”. Tommaso declares that Manfredi will inherit his title, privileges and possession upon his death. If, after the marriage is celebrated, Manfredi were to die first, Beatrice would enjoy possession of the castle and some properties. The Marquise Luisa declares to agree with her husband’s decision (“[…] e a tuto questo la marchexa aloysia madre dy manfredo consenty”, Gioffredo Della Chiesa, Cronaca di Saluzzo, p. 165-166). The union was formally celebrated the year after.

Beatrice bore Manfredi two children: Caterina and Federico, born presumably in 1287 (“Et da questa beatrix haue uno figlolo chiamato fredericho et una figlola chiamata Kterina” Gioffredo Della Chiesa, Cronaca di Saluzzo, p. 185). In 1296 Tommaso died, so Manfredi inherited the marquisate and Beatrice became Marquise consort of Saluzzo. She will die eleven years later at 47, on November 19th 1307 (“Venne a morte nel dì 19 novembre di quest’anno Beatrice di Sicilia moglie del nostro marchese Manfredo, e noi ne accertiamo il segnato giorno col mezzo del rituale del monastero di Revello , nel quale leggesi annotato: 19 novembris anniversarium d. Beatricis filiae quondam d. Manfredi regis Ceciliae et uxoris d. Manfredi primogeniti d. Thomae marchionis Saluciarum, quae huic monasterio quingen- tas untias in suo testamento legavit.” Delfino Muletti, Memorie storico-diplomatiche appartenenti alla città ed ai marchesi di Saluzzo, vol III, p. 76). Her husband would quickly remarry with Isabella Doria, daughter of Genoese patricians Bernabò Doria and Eleonora Fieschi. Isabella would give birth to five more children: Manfredi, Bonifacio, Teodoro, Violante and Eleonora.

As of Beatrice’s children, Caterina would marry Guglielmo Enganna, Lord of Barge (“Catherina figlola dy manfredo e de la prima moglie fu sorella dy padre e dy madre dy fede rico e fu moglie duno missere gulielmo ingana capo dy parte gebellina in questy cartiery dil pie monty verso bargie.”, Gioffredo Della Chiesa, Cronaca di Saluzzo, p. 256). Federico’s fate would be more complicated. Like many mothers before and after her, Isabella Doria wished to see her own firstborn, Manfredi, succeeded his father rather than her step-son. The new Marchioness of Saluzzo successfully instigated her husband against his son to the point the Marquis. in a donatio mortis causa dated 1325, disinherited Federico in favour of the second son (Federico would have settled with just his late mother’s belongings), Manfredi (“Et questo faceua a instigatione de la moglie che lo infestaua a cossi fare.” Gioffredo Della Chiesa, Cronaca di Saluzzo, p. 224). Federico’s natural rights were later acknowledged by an arbitral award proclaimed in 1329 by his paternal uncles Giovanni and Giorgio of Saluzzo, and finally, an arbitration verdict dated 1334 and issued by Guglielmo Earl of Biandrate and Aimone of Savoy. As a condition of peace, the future Marquis should have granted his younger brother the castle and villa of Cardè as a fief. Stung by this defeat, Manfredi IV, his wife Isabella and beloved son Manfredi retired to Cortemilla. Federico died in 1336 and was succeeded by his son Tommaso, who would inherit his father’s rights and feud with the two Manfredi's. After being defeated by his half-uncle in 1341 (the older Manfredi, his grandfather, had died the year before), resulting in losing his titles, possessions and freedom, Tommaso would later regain what was of his right and rule as Marquis of Saluzzo.

Sources

-ANONIMO REGIENSE, Memoriale Potestatum Regiensium. Gestorumque iis Temporibus. Ab anno 1154 usque ad Annum 1290, in Ludovico Antonio Muratori, Rerum Italicarum scriptores ab anno aerae christianae quingentesimo ad millesimumquingentesimum, vol. VIII

-BARTHOLOMAEUS DE NEOCASTRO, Historia Sicula, in Giuseppe Del Re, Cronisti e Scrittori sincroni Napoletani editi ed inediti

- DEL GIUDICE GIUSEPPE, La famiglia di Re Manfredi

- DELLA CHIESA, GIOFFREDO, Cronaca di Saluzzo

-FORGES DAVANZATI, DOMENICO, Dissertazione sulla seconda moglie del re Manfredi e su’ loro figliuoli

- LANCIA, MANFREDI, Il complicato matrimonio di Beatrice di Sicilia

-Monferrato. Saluzzo

-MULETTI, DELFINO, Memorie storico-diplomatiche appartenenti alla città ed ai marchesi di Saluzzo, vol II-III

- MUNTANER, RAMON, Crónica catalana

- SABA MALASPINA, Rerum Sicularum

- SAVIO, CARLO FEDELE, Cardè. Cenni storici (1207-1922)

-Sicily/Naples: Counts & Kings

#women#history#women in history#historical women#history of women#beatrice of sicily#manfredi i#helena angelina doukaina#costanza ii#manfredi iv of saluzzo#federico of saluzzo#caterina of saluzzo#House of Hohenstaufen#norman swabian sicily#aragonese-spanish sicily#house of saluzzo#people of sicily#women of sicily#myedit#historyedit

46 notes

·

View notes