#feedlot farming

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Focus on High Quality Beef: How Small-Scale Beef and Dairy Farmers Thrive in Urban Slums

Explore how Kenyan farmers are producing high quality beef by adopting modern feedlot practices and crossbreeding Bos taurus with traditional cattle breeds. Learn about the strategies behind producing high quality beef in Kenya, from selecting the right breeds to targeting premium markets for better profitability. Discover how feedlot farming and crossbreeding techniques are helping Kenyan…

#beef export market#beef farming challenges#beef farming in Kenya#beef farming profitability#beef feedlot practices#beef production strategies#beef weight gain#Boran cattle#Bos indicus cattle#Bos taurus breeds#cattle breeds in kenya#cattle fattening techniques#cattle rearing in Kenya#crossbreeding cattle#dairy cattle crossbreeds#dairy vs beef farming#feedlot farming#High Quality Beef#high-end beef market#kadogo economy#Kenyan beef industry#Kenyan butchery market#Kenyan meat production.#Makueni County farming#meat quality improvement#premium beef market#profitable beef farming#Sahiwal cattle#slow-growing cattle breeds#sustainable beef farming

0 notes

Text

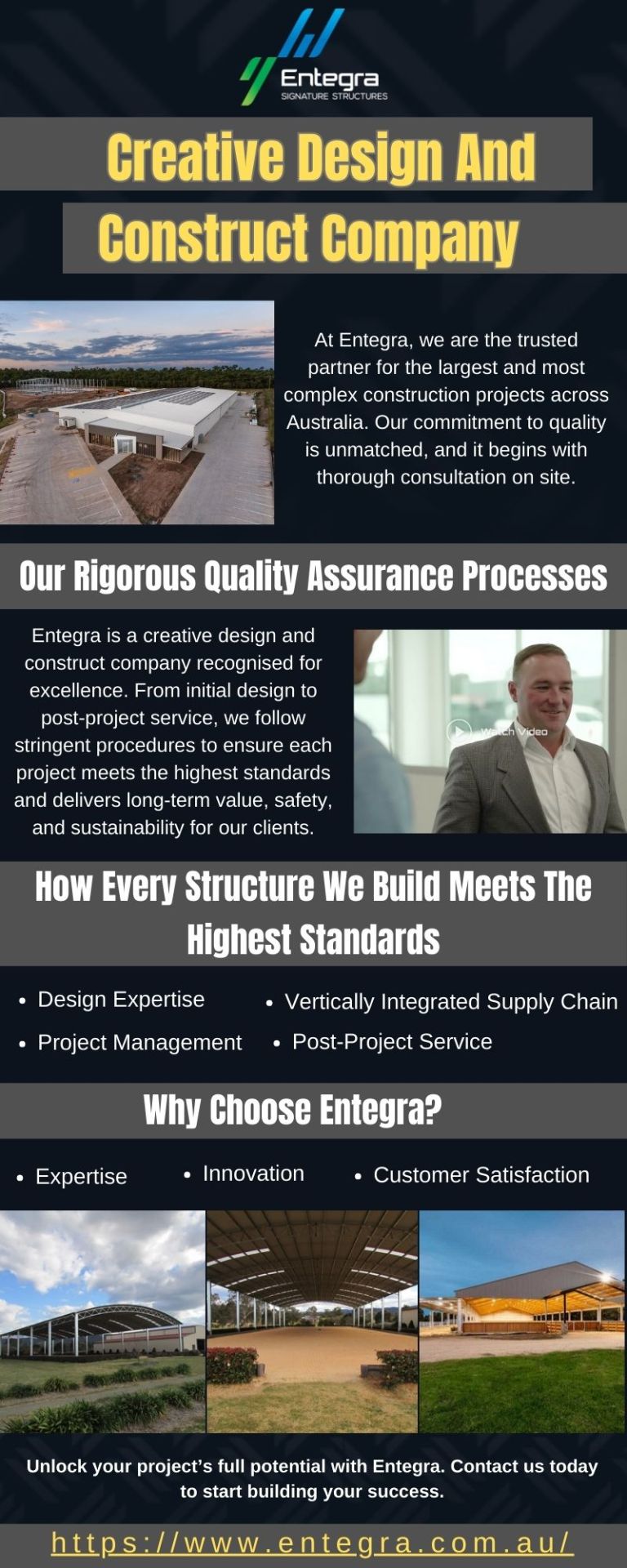

Top Construction Company Australia - Entegra Signature Structures

Discover the full potential of your construction projects with Entegra Signature Structures. We specialize in cutting-edge solutions for both residential and commercial endeavors, offering expert support every step of the way—from initial concept to final completion. For more details visit the link.

#construction projects#construction company Australia#Construction Solutions#Dairy Sheds#Industrial Sheds#Feedlot Sheds#Equine Arenas#Hay Sheds#Rural Farm Machinery Sheds#Horticulture Sheds and Buildings#Industrial Buildings#COLA’s#Cotton Sheds#Entegra Signature Structures

0 notes

Text

As the link between animal agriculture and climate breakdown becomes clearer, if anything, we are seeing more ordinary people falling over themselves to defend an industry that is destroying our planet, polluting our communities, exploiting animals and human workers. This is especially worrying to see from leftists, in spaces that are supposed to be progressive. I promise you, you do not need to spend your time greenwashing leather and wool, repeating blatant industry propaganda about veganism, 'regenerative agriculture' or whatever other buzzword they're using to sow doubt this week. The industry already spends millions of your dollars to lobby our politicians and influence public opinion; they don't need you to do it for free.

Vox – The greenwashing of wool explained

New Republic – The comforting lie of climate-friendly meat

Guardian – Big Beef’s climate messaging machine

The Breakthrough – Is Feedlot Beef Better for Environment?

International Journey of Biodiversity – Misinformation on Science of Grazed Ecosystems

Food Climate Research Network – Grazed & Confused

Science 2.0 – The regenerative ranching racket

DeSmog – A guide to six greenwashing terms

Truthdig – The backlash to plant-based meats

Independent – Meat & dairy industries downplaying role in climate crisis using tobacco tactics

Guardian – Meat & dairy lobbyists turn out in record numbers at COP28

Greenpeace – How Big Agriculture is borrowing Big Oil’s playbook at COP28

Guardian – Plans to present meat as ‘sustainable nutrition’ at Cop28 revealed

Guardian – Ex-officials at UN farming body say work on methane emissions was censored

Guardian – How UN food body played down role of farming in climate change

QZ – The meat industry blocked the IPCC’s attempt to recommend a plant-based diet

The Times – Red Tractor farms more likely to pollute environment

Influence Map – European meat & dairy industry weaken EU’s climate policies

The Grocer – Meat Industry lobbying behind cultured meat bans

Food Unfolded – Truth, tactics and the mist of meat lobby science

Business Green – Climate lobbying: Are meat and dairy lobbyists the ‘new merchants of doubt’?

Vox - A newly surfaced document reveals the beef industry’s secret climate plan

480 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seaweed is once again showing promise for making cattle farming more sustainable. A study by researchers at the University of California, Davis, found that feeding grazing beef cattle a seaweed supplement in pellet form reduced their methane emissions by almost 40% without affecting their health or weight. The study was published Dec. 2 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. This is the first study to test seaweed on grazing beef cattle in the world. It follows previous studies that showed seaweed cut methane emissions 82% in feedlot cattle and over 50% in dairy cows.

Continue Reading.

229 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Decade Of Doom!

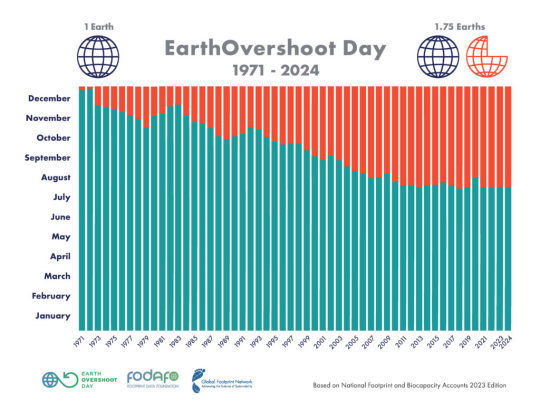

I started this blog ten years ago to compile the growing evidence that our planet would not longer be able to sustain human life by 2050, thanks to our continued, capitalist-fueled efforts to destroy all the systems we rely upon to sustain life. The first thing I put up here was this essay, on February 20, 2014. Now, a decade later, I thought it might be "fun" to look at what's changed: 1) Earth Overshoot Day

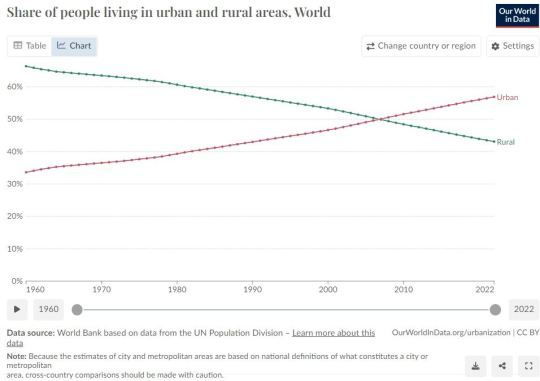

In 2014, "Earth Overshoot Day" (the day that humanity collectively consumes more resources from nature than it can regenerate over a year) was August 19th. Now, in 2024, Earth Overshoot Day is August 1st, 2.5 weeks earlier. At this rate and assuming things don't accelerate (even though they are likely to), Earth Overshoot Day will be around June 17th by 2050. 2) Biocapacity Biocapacity is the amount of resources contained on the planet required available to sustain life, measured by area. In 2014, I calculated that the planet had a biocapacity of 1.7 hectares per person. By dividing the total available biocapacity today in 2024 with the current global population as I did then, it now appears that there are just 1.5 hectares of planetary resources left per person to extract all the materials needed to sustain life, as well as all the area available to dispose of waste. That's a 12% loss over ten years. At that rate, we can expect to lose another 30% of biocapacity by 2050, going down to just 1.05 hectares per person by then, and that's assuming that the rate of biocapacity loss does not accelerate further and that the global population suddenly stops increasing after a run of non-stop increases spanning five centuries. Oh, also a reminder that the average human requires 2.7 hectares of land to sustain its current consumption habits/levels. So. 3) Individual Conservation To illustrate the futility of individual conservation at this point in the apocalypse, let me give you an example: If you were: a fully-vegan localvore living in a one-bedroom apartment with nine other people and using 100% renewably-generated electricity; who did not ever use motorized transportation of any kind or buy new clothing, furnishings, electronics, books, magazines, or newspapers and recycled all the waste you generated that was recyclable, you'd only require 1.4 hectares of biocapacity to sustain yourself. That is close to the kind of lifestyle extremism it would take to live sustainably. Deviate from that level of stoicism even slightly (say by living in a two-bedroom apartment with three other people instead of a one-bedroom apartment with nine other people and taking a single, four-hour roundtrip flight, once a year) and you're now consuming 1.6 hectares of biocapacity, which means you're using more resources than the world has available for you if everything was divided evenly among everybody. Of course, biocapacity, like all resources, are not divvied up evenly among everybody, which is why there are currently 114 different armed conflicts happening worldwide - the highest number of armed conflicts since 1946. 2023 was the most violent year in the last three decades. 4) Other Signs Of The End Times In my 2014 essay, I referenced the work of geologist Dr. Evan Fraser, who studies civilization collapse. In his book Empires of Food, Dr. Fraser noted common signs of a civilization about to collapse, which began to appear about two decades before it all goes completely to hell. Those signs were: -a rapidly-increasing and rapidly-urbanizing population We've added 700 million people to the planet since I began this blog in 2014. And where is everyone moving to?

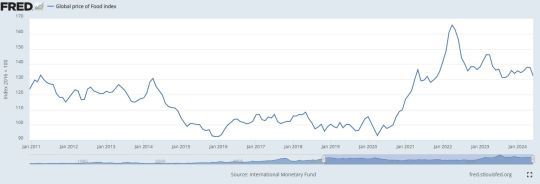

-farmers increasingly specializing in just a small number of crops " "As farm ecosystems have been simplified, so too are the organisms that populate the farm. A farm that specializes in a limited number of crops in short rotations does not, for example, look for plant varieties that do well in more complex rotations with intercropping. A beef feedlot operation wants breeds that gain weight quickly on grain diets and does not want cattle breeds that digest well pasture grasses and thrive in all year outdoor environments on the range." The result? Recent estimates put the loss of global food diversity over the last 100 years at 75%. Over the 300,000 species of edible plants that exist, humans only consume about 200 of them in notable quantities, with 90% of crop plants not being grown commercially. -endemic soil erosion Climate change and the need to raise more crops have combined to increase the rate of agricultural soil erosion globally. Back in 2014, when I started blogging about the end of everything, the UN had already determined that there was only enough fertile soil left to plant 60 more annual crops. So, by 2074, we won't be able to grow food, full stop. This of course comes at a time when the global population continues to increase, and with it the need to grow more food. If projections are accurate, we will need to increase food production by 50% over the next three decades to feed everyone. -a dramatic increase in the cost of food and raw materials When I started this blog in 2014, I noted that 2011-2013 had seen the highest food prices on record. So what's happened since then?

It's important to point out here that the current food price spike started in 2020, so if Dr. Fraser's calculations are correct, the food system will collapse sometime around 2034, taking civilization with it. I closed my debut essay on this blog with a quote from the (now deceased) climate scientist Dr. James Lovelock, who advised a Guardian journalist to "enjoy life while you can. Because if you're lucky it's going to be 20 years before it hits the fan." That interview was published in 2008. We have four years left to enjoy.

#doomsday#human extinction#apocalypse#climate change#global warming#capitalism#civilization collapse

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rain’s A Good Thing

WC 3,501 | GEN | CW: I’ve never chased a tornado, I don’t know how to drive manual

Read on Ao3

Hawkins, Indiana is a farm town.

Tommy Hagan’s family owned the largest feedlot in the county. Carol Perkins’ father was the leading corn producer in the state of Indiana. During the summer, Andy Hostetter and Chance Murillo worked harvest, and the McKinney family has a turkey farm.

And Steve?

Steve is the furthest thing from a country boy.

His father, Richard Harrington, is (ironically) one of the state’s leading divorce attorneys. His mother, Catherine, hated for Steve to get any sort of dirt on him. He was never allowed in sandboxes when she took him to the park. Never allowed to splash in puddles or play in the rain or roll in the grass.

Never allowed to get dirty.

Never allowed to be an Indiana country boy.

Until he met Eddie.

Eddie didn’t grow up on a farm, but he did spend the majority of his formative years in Forest Hills. When he stayed with Wayne as a child, he made mud pies and played with the trailer park dog. He played in the forest, following the creek deep into the woods and catching crawdads.

Eddie still goes fishing with Wayne. Not afraid to hold the catch of the day, posing for Wayne’s photo. Eddie loves driving on dirt roads, taking the back way to Indy, or just taking a late night cruise.

As much as Eddie denied, denied, denied, he was a country boy through and through.

And although Steve has spent his entire life in Hawkins … he was a city boy.

And Eddie keeps forgetting that.

It was a rainy Saturday afternoon. The third or fourth day in a row. Steve lost count. He hated rainy days. Especially storms. He felt trapped in his own home, but the last few days he spent at the trailer with Eddie felt special. The boys were both off from work and lazily tangled on the couch, watching ‘Used Cars’, questionably ‘borrowed’ from Family Video. Steve called it a perk of his job. Eddie knew Steve picked the movie solely because Eddie admitted that he used to have a crush on Kurt Russell (“Used to?” Steve laughed, “You still do!” “Do not!” “Do too!”), but there was something about the shitty cars driving through the mud of the dealership that had Eddie aching for a drive.

“We should go muddin’,” Eddie grinned, pressing a quick kiss to Steve’s lips before untangling his limbs. He climbed off the couch, taking a few steps into the kitchen to grab his keys off the counter.

“Go what-ing?” Steve said, sitting up.

“Muddin’,” Eddie said with a grin. It falters for a second. “Have you ever gone muddin’ before?”

“No,” Steve wrinkled his nose. “Like… playing in the mud?”

“Kinda,” Eddie shrugged. “It’s more driving around in the mud.”

“I’ve practically been muddling all week leaving the trailer park,” Steve said with a playful frown. “So what? We’re getting my car muddy on purpose?”

“Yeah, that’s the point,” Eddie said. “Besides, we’re not taking your car.” He flips his keys a few time for show. “We need to break this bad boy in.”

The bad boy in question was a 1972 Chevy Cheyenne, which is plenty of broken in. Eddie was able to buy it last month for a few hundred dollars. Eddie has been finding every excuse in the book to ‘break it in’ including taking it to the drive-in, stargazing, going for a late night cruise, a redneck swimming pool (Eddie’s words for the tarp in the bed of the truck and filling it with water), fooling around in the cab of the truck, fooling around in the bed of the truck, and now apparently mudding.

“C’mon,” Eddie whined like a child. “It’s hardly storming out there. I’ll take you out to the Dairy King afterwards. I’ll buy you a milkshake and curly fries.”

“Okay,” Steve sighed. “But were each getting our own milkshake.”

Eddie pumped his fist in the air. Steve couldn’t help but grin. “C’mon!” Eddie said, taking the few steps back to Steve and grabbing his arm, pulling him up. “We’re missing out on valuable mud time.”

“It’s supposed to rain all day,” Steve said, following Eddie to the truck. “There’s gonna be mud for the next few days.”

“Which means we’ll have to go again tomorrow,” Eddie grinned. “Plus it’s more sprinkling than anything. This is hardly anything. Here —“ Eddie handed Steve his mechanic’s work jacket, Eddie’s name stitched in red over the heart. “The finest robe for his majesty.”

Steve rolled his eyes, slipping on the jacket as Eddie ushered him out into the rain and into the Chevy. Eddie was right. The rain was light, nothing that made Steve concerned or worried. He just didn’t want to get his Nikes covered in mud. Eddie promised if they get dirty, he’d throw them in the washing machine with his Reeboks, but promised that they wouldn’t get out of the truck into the mud. Steve shoved his hands into the jacket pockets, feeling the cool metal of Eddie’s lighter against his finger tips. Eddie, the ever so gentleman, took three steps past Steve to the passenger door, yanking it open for Steve.

“Your chariot,” Eddie said with a bow. Steve couldn’t help but grin as he climbed into the truck, Eddie shutting the door behind him. Eddie started to jogged around the truck, jumping against the hood as if he was trying to slide over it to the other side. Steve couldn’t help but laugh, trying to figure out how anyone thought his goofy boyfriend was scary.

“You’re such a dork,” Steve said to Eddie as he climbed into the Chevy.

Eddie shot him a shit eating grin and revved the engine, “but I’m your dork. You ready?”

“As I’ll ever be,” Steve said.

Eddie pulled the truck into reverse, pulling away from the trailer home. Eddie fiddled with the music, going from station to station until he found one that was mostly music and less static. As he drove through the trailer park, the Chevy Cheyenne dug through the mud, leaving deep tracks behind. Eddie pulled onto the highway, driving out of town.

“I thought we were going mudding in the trailer park?” Steve asked.

“You gotta have open space to go muddin’,” Eddie explained. “I figured the fairgrounds, maybe some country roads. I promise, we will be safe. Nobody has ever died from muddin’.” There was a long pause. “Yet.”

“Eds,” Steve warned. Eddie smirked, reaching over to squeeze Steve’s thigh.

“I’m kidding!” Eddie said, squeezing again. “You know I’m a safe driver. I drove your Beemer before and you had no complaints!”

“Because I had a migraine,” Steve said. “And Robin still doesn’t have her license.”

“You would trust Robin over me?” Eddie gasped, jerking his hand away from Steve’s leg and bringing it over his heart. “Sweetheart, you wound me!”

Steve frowned, grabbing Eddie’s hand and placing it back over his thigh. Eddie grinned. “You’re so dramatic.”

“But you love it,” Eddie laughed, squeezing Steve’s thigh. “Right, baby?”

“Right,” Steve said, with a goofy smile. He kept his hand over Eddie’s as they drove a few miles out of town to the fair grounds.

The fairground parking was more dirt than anything. The annual Roane County Fair occurred the first week of July. Steve hasn’t found the energy to go, now that the Fourth of July was associated with being tortured by Russians. But maybe things would be different this year with Eddie holding his hand in secret.

The dirt parking was soaked with rain, mud piles and large puddles. Eddie looked over at Steve with the biggest grin. “You ready?”

“Yeah,” Steve said. “Sure.”

Eddie revved the engine a few times before taking off, Steve jerking back in his seat with a laugh as Eddie drove into the first mud puddle he saw, splashing the windshield with mud. He ran the wipers, smearing the mud on his windshield, steering the car into more mud. The truck slowed in the mud, stuttering against the sludge as it powered through the mud, kicking back. The brakes slipped, the Chevy lurching forward. Steve jerked forward, slamming his hand on the dash to keep him stable.

Eddie let out a hoot of a laugh. He kept his hand on Steve’s thigh, squeezing gently any time he needed to move his hand to switch between first and second gears. He pushed on the gas, the truck accelerating to the next puddle, coating Steve’s window in mud. The shocks in the truck already made Steve feel every bump in the unpaved roads to Eddie’s trailer. The bumps and dips in the fairground seemed worse, jerking the truck up and down unevenly like a rollercoaster ride. Steve couldn’t help but laugh when he felt his ass leave the seat.

“Now you get me!” Eddie grinned, jerking the wheel to the side, finding more mud to dig up with the tires. The thick mud would get stuck in his tires, kicking up to the bed of the truck, even the back window was covered in mud. It was gonna be a bitch to clean, but that’s a problem for another day.

The Chevy slid in the mud, losing traction, sliding ever so slightly. Eddie squeezed Steve’s thigh, holding him down. “Eds —“ Steve braced himself against the door.

“I got it,” Eddie said, pumping on the brakes, regaining control of the truck. “Just a little slide action.”

Steve doesn’t know how long they were out in the fairgrounds. Long enough to get the truck coated in mud. There was no seeing out the back window and the side windows weren’t any better. Eddie was lucky enough that his windshield wipers were able to clean the front windshield enough that he could see the highway as they left. But instead of turning right to go back into town, he turned left.

“Hawkins is that way,” Steve frowned.

“I know,” Eddie said. “I got one more spot to show ya. There’s a road by Hagan’s feedlot that’s usually muddy.”

“God, the feedlot smells,” Steve groaned.

“And it’s gonna smell worse during the rain,” Eddie grinned. “Just hold your breath, it’s just past the feedlot.”

Sure enough, the feedlot reeked. Eddie turned down the dirt road just past the feedlot, driving about a mile down the road where the slightly wet dirt road turned muddy. The road was full of divots and potholes, bouncing the truck with every movement. The mud started to fly back up onto the windshield as the rain started to come down again.

Then, Steve noticed the hill.

The truck started to go up the large hill, stuttering in the mud. Steve swore the truck even slipped backwards a little, but Eddie didn’t flinch.

“Eds —“

“I got this,” Eddie said, pressing on the gas and shifted gears. The tires spun, kicking up more mud against the windows. The rain started to pour harder. Steve reached over his shoulder for the seat belt.

“Eddie —“ Steve said as his seat belt clicked. Eddie squeezed his thigh, letting go so he could grab his seat belt with one hand, pulling it over his shoulder and to his hip. Steve reached over and buckled it in for him. Eddie shot him a quick wink, returning his hand to Steve’s thigh.

“Ready?” Eddie asked. Steve wasn’t sure if there was a choice, now that they were at the top of the hill —

“Oh fuck —!”

The Chevy Cheyenne went over the hill — Steve swore they flew in the air for a brief moment, feeling his gut and his ass leave the seat — and then they went down.

The Chevy was going fast, Eddie’s foot off the gas as they made their way down the hill, kicking up mud and shaking in the truck. Thunder sounded around them. Rain poured. Eddie squeezed Steve’s thigh. Steve grabbed his arm, wrapping his own around him. The Chevy shook, mud landing on the windshield, quickly washed away as the rain grew heavier and heavier. Hail hit the windshield. The traction slipped, sliding ever so slightly, enough to make Steve’s gut drop.

“Eddie —!”

“I got it,” Eddie said, letting go of Steve’s leg and gripped the steering wheel. He pumped the breaks, attempting to slow the truck down. Eddie turned the wiper switch on high, watching them try to push the rain water and mud away from the windshield. The rain poured harder. The road evened out at the bottom of the hill. Eddie could barely see out of the windshield with how heavy the rain was. The truck shook with the winds.

Steve reached for the radio, moving the frequency from FM to AM. Crackling over the speakers came the weather report.

“This is the National Weather Service with an urgent weather report. Severe thunderstorm warning is issued for the following counties: Clay, Greene, Hendricks, Monroe, Morgan, Putnam, and Roane —“

“Just a thunderstorm,” Eddie said, his grip still so tight on the wheel that his knuckles were turning white. “It’ll pass. We’ll be okay once we get out of the rain.”

“Is there a paved road soon?” Steve asked, feeling his heart hammering in his chest. Eddie pressed his lips together. “Ed?”

“About three more miles,” Eddie said. “Or I can try to turn around and we take that hill again.”

Steve couldn’t look out the passenger window, the mud too thick on the glass. He could barely see the road in front of them, let alone how deep the ditches are or when the next cross road was.

“Let’s keep going —“

“A tornado watch has been issued for the following counties: Greene, Monroe, and Roane —“

“Eddie —“

“Got it,” Eddie clenched his jaw, pressing on the gas.

“What’s worse,” Steve asked. “A tornado watch or a warning?”

“Doesn’t matter,” Eddie said. “We hardly get tornadoes. It’s not gonna happen —“

“A tornado warning has been issued for northwest Roane County —“

“Shit,” Eddie muttered.

“Eddie —“

“Yeah,” Eddie nodded. “That’s — that’s us.”

Steve nodded, clenching his jaw. He pulled on his seat belt, as if it would tighten more than it already was.

“It could be anywhere,” Eddie said raising his voice over the wind, holding the wheel tight, focused on keeping them on the road. “Hawkins is in the northwest part of the county. Doesn’t mean it’s touched ground. Just seen. Just —” Eddie shook his hand, barely above the wheel, frustrated. “Keep a look out.”

“I can’t see shit, Eds!” Steve shouted, winds whistling through the windows. The rain curtain made it near impossible to see out the front of the truck. “Pull over!”

“I can’t just — pull over, Steve!” Eddie snapped. “The ditches —“

“We should’ve stayed home!” Steve yelled.

“Trailer ain’t got shit against a tornado,” Eddie punched the steering wheel. “Fuck!”

The winds grew stronger. The truck shook, shocks bouncing like it did on the fairgrounds.

“Eds —“

“I know, Steve —“

“No, Eds —“

“I can’t just pull over —“

“Eddie!” Steve smacked Eddie’s chest, leaning over and pointed out the window. “Fucking stop!”

Eddie glanced out the window, watching a funnel cloud form, twisting in the air to the northeast. “Fuck!”

He slammed on the brakes, instantly regretting it as the truck started to swerve, threatening to spin as the rear wheels lock up. Eddie jerked the wheel, correcting his mistake and keeping the truck on the muddy road. Eddie pumped the brakes, feeling the truck slowly but surely come to a stop.

It felt surreal, in the midst of a storm. The whistling wind shaking the truck, the warm May temperature dropping ten degrees in a matter of moments. Rain and hail banging on the cab’s rooftop. No words exchanged from the boys, just heavy breaths and heartbeats. It wasn’t until the NOAA weather alert repeated for the third time since they stopped, that Eddie realized Steve’s hand was pressed against his chest.

Even then, they couldn’t take their eyes off the funnel cloud, getting bigger by the moment. Winds getting stronger and stronger until —

The tornado touched the ground.

“Holy fucking shit.”

Eddie nodded. “Holy fucking shit is right.”

It didn’t seem like they could do anything but watch.

Eddie wished they would’ve stayed home.

“Eds. Eddie,” Steve said, leaning forward in his seat. “It’s — it’s moving.”

Hell.

Sure enough, the tornado changed courses, no longer heading their direction, but parallel to the highway only a half-mile away. The rain started to lift. The hail stopped.

Eddie let out a laugh.

He reached out, grabbing Steve’s shoulder and shaking it. “God, Steve. I — I think I pissed myself.”

Steve laughed, leaning over and catching Eddie’s lips with his own. “Holy fucking shit.”

“Holy fucking shit is right,” Eddie said, smacking the steering wheel a few times. “Okay,” Eddie laughed, putting the truck into first. “Look, I know it was a mess, but if we go back over the hill —“

“What if we didn’t.”

Eddie raised his eyebrow, looking at Steve. “Then we’re following the storm. Storm’s past, I’ll go slow —“

“What if,” Steve said, a little stronger, slower. His eyes shining with something Eddie’s still not quite sure about. “What if we chased it.”

Eddie laughed in disbelief. “Chased it,” he said. “The tornado?”

“Yeah,” Steve said, a small smirk on his face. “Or are you too scared?”

Eddie’s face broke out into a shit eating grin. He leaned over the center seat, pressing a kiss against Steve’s lips. He leaned back, smacking Steve’s chest a few times, “That’s my country boy! Let’s fucking go!”

Eddie leaned back into his seat, pressing on the gas. Steve let out a laugh, as Eddie switched to second gear. Soon, they ran out of the dirt road, hitting the pavement. Eddie turned right, catching the rain. The tornado was now in full sight through the muddy windshield, maybe two miles out in the country. It wasn’t a large tornado, even close by, Eddie felt like he had decent control over the truck with the wind speeds. Nothing like they experienced minutes before.

They watched as the tornado tore up the pasture.

“You think —“ Steve said, stopping as if he was questioning himself. He looked at Eddie, a curious look on his face. “You think we could get closer?”

“Can we get — yes,” Eddie shot Steve an award winning grin. “Get ready, we’re going off roading.”

“Off-roading? Eds—!” Steve braced himself against the dash as Eddie drove off the road, into the ditch and into the pasture. He drove at an angle, trying to get closure to the tornado, while trying to keep up with it. Steve laughed as the Chevy shook, hitting uneven dirt and mud. Eddie pressed on the gas, shifting gears, speeding up.

The wind grew stronger as they grew closer to the tornado. Blowing pieces of wheat and hay around them. It was one thing seeing the tornado miles away, but up close? It was terrifying and beautiful at the same time. The way the wind controlled and destroyed the land. Dirt clouds at the bottom, the rain clouds following the top. Steve’s seen pictures of damages from tornadoes. Towns leveled by only a few minutes of a tornado. Lives changed in a matter of moments.

And they were following the danger, no way to stop it. No way to prevent the destruction.

That is, until the tornado slowed. They started to catch up on it. Eddie lowered gears, slowing down. Eddie knew. Steve was just figuring it out.

This was the end of the tornado.

Soon, the dirt settled below. The storm clouds above remained, but the rain lightened to a sprinkle. The tornado became smaller and smaller, thinner and thinner until it no longer touched the ground. Then, it practically faded into air, settling down for good and clearing the air.

“Damn,” Eddie said, putting the truck into park in the middle of the pasture. “Fun while it lasted.”

“Really fun,” Steve grinned. “We going storm chasing again tomorrow?”

“Jesus Christ,” Eddie laughed. “Hates the rain, he says! Spends all day locked indoors. We have awaken the real storm here.”

“Guess you could say rain’s a good thing,” Steve grinned. Eddie leaned over the middle seat, catching Steve’s lips with his own. “I think you owe me a milkshake.”

Eddie leaned back into his seat, rocking the truck as he does. “The storm requires a milkshake! To the King, we go!”

Eddie revved the engine, putting it into first gear and pressing on the gas. The Chevy Cheyenne stays true to its country boys, kicking up dirt as it jerks into motion, working its way through the pasture and back onto the pavement. Steve looked over at Eddie, grinning and humming to the radio now that the frequency was off the weather and back on FM. Eddie looked over at Steve, grinning. He placed his hand back on Steve’s thigh, squeezing. Steve put his hand over Eddie’s, running his thumb over Eddie’s knuckles.

Sure. Steve might be afraid of storms, but with Eddie by his side? He could face a fucking tornado.

#stranger things#eddie munson#steve harrington#steddie#steddie fic#steddie ficlet#storm chasing’s here !!!!!!!!!!!#//myfics#//myfic

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

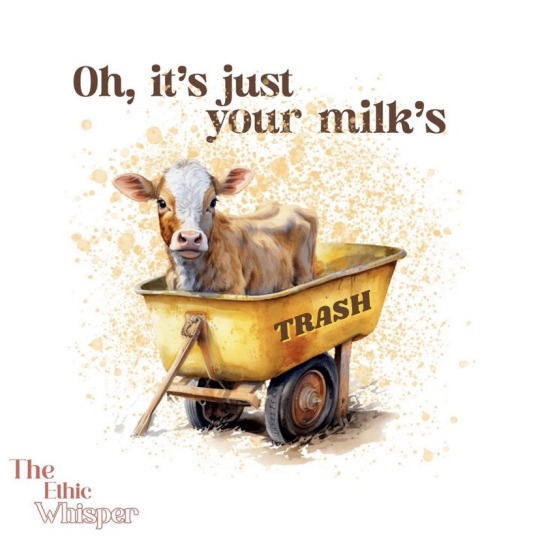

Male calves are often considered entirely disposable by the dairy industry, though some farms are equipped to exploit them for other purposes. Regardless, no male calf will live beyond the age of 2 years before being killed - and in some cases, the end can come within the first few hours of life.

Male dairy calves can be sold for beef production to eventually be turned into food like hamburgers. They're sent to feedlots, which are penned-in facilities that can hold up to 150,000 cattle, where they are confined and fed grain diets so that they gain weight and can be slaughtered as quickly as possible.

Calves are separated from their mothers, fed an artificial milk replacement, and prevented from fully socializing or even touching another animal until they are sent to the slaughterhouse, which occurs when calves are 8-16 weeks old.

In the United Kingdom, where veal crates have long been outlawed due to their overt cruelty, it's often cheapest to simply shoot male calves shortly after their birth. In the UK, close to 60,000 male calves are disposed of in this way every year. This practice is also disturbingly common in the United States, and in Australia, where one survey revealed that around 600,000 male calves were killed on dairy farms every year when they are just a week old.

Image with kind permission from The Ethic Whisper.

@theethicwhisper

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

In October, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. stood outside the United States Department of Agriculture headquarters and railed against the state of US agriculture. Big farms, pesticides, and feedlots were all part of a system that he said was destroying the health of Americans. “When Donald Trump gets me inside the building I’m standing outside right now, it won’t be this way anymore,” he said in a video uploaded to YouTube.

President Donald Trump did not get RFK Jr. inside the USDA. Instead he nominated his erstwhile opponent as Secretary of Health and Human Services, a role which will put Kennedy—if confirmed—in charge of vaccine policy, science funding, and public health. As HHS secretary, RFK Jr. would also be the most prominent supporter of organic farming in any recent administration, albeit one with limited access to the levers of power in agriculture, almost all of which reside with the USDA.

Even as an outsider, Kennedy’s vocal support of organic agriculture—and its central role within his Make America Healthy Again (MAHA) campaign—cements a realignment in the politics of organic farming. Eating organic has long been associated with left-leaning, Whole-Foods-tote-wielding urbanites. Now its biggest proponent is at the heart of the most right-wing US government in decades. In this shift, some groups spy an opportunity to place organic farming at the heart of the MAGA narrative—while others are concerned that RFK Jr.’s obsession with organic poses a serious risk to the climate.

That this realignment is happening at all is testament to Kennedy’s strangeness as a political figure. A longtime environmental lawyer at the National Resources Defense Council, he’s fought against water polluters and coal miners. His 2005 book Crimes Against Nature criticizes George W. Bush for allowing corporate interests to capture the US government and undermine environmental law. “The administration is systematically muzzling, purging, and punishing scientists and other professionals whose work impedes corporate profit taking,” he wrote in the book’s introduction. “The immediate beneficiaries of this corrupt largess have been the nation’s most irresponsible mining, chemical, energy, agribusiness, and automobile companies.”

Now Kennedy is vying to join an administration headed by a president who has dismissed climate change as a hoax and whose nominated energy secretary is currently CEO of one of America’s largest fracking companies. But RFK Jr.’s brand of environmentalism already eschews the main focus of the modern movement: carbon emissions. “Democrats have been subsumed in this carbon orthodoxy,” he told Tucker Carlson in August. “Everything is measured by its carbon footprint … And the reason we protect the environment is just the opposite of that. The reason we protect the environment is because there’s a spiritual connection.”

RFK Jr.’s embrace of organic—a vaguely defined approach to farming that shuns pesticides, herbicides, and artificial fertilizers and emphasizes soil health—aligns him more closely with the worldview of so-called “crunchy” environmentalists: suspicious of processed food and nostalgic for a vision of farming that harkens back to a simpler, more rural way of life. At his hearing on Wednesday, RFK Jr. thanked the “MAHA moms”—many of whom share his suspicion of vaccines as well as his dislike of pesticide and genetically modified crops.

It also puts him on a collision course with people who worry that a switch to organic crops would make it much harder for the US to achieve its climate goals. Organic crops tend to produce less yield per acre, thus requiring larger areas of land to grow the same amount of crops, which in turn increases carbon emissions and threatens biodiversity as more land is converted to agriculture.

On January 14, environmental research group The Breakthrough Institute published a letter opposing Kennedy’s confirmation as HHS secretary. The letter cites as a warning the Sri Lankan government’s April 2021 decision to switch to organic farming, which led to plummeting yields, skyrocketing food prices, and protesters storming the presidential palace. The Sri Lanka chemical ban was encouraged by environmental activist Vandana Shiva, whom RFK Jr. has described as a “hero” and a “role model.”

If he is confirmed in the HHS role, RFK Jr. will have limited influence on agricultural policy, says Emily Bass, associate director of federal policy, food, and agriculture at Breakthrough. But he would have oversight of the Food and Drug Administration, which enforces regulation of food in the US. “Pesticide residue limits are something that he could certainly influence with his regulations,” says Bass. And “limiting use of genetically modified crops, or more strictly monitoring their existence in the food supply, is something that could create a chilling effect on agricultural production.”

The HHS secretary also oversees the National Institutes of Health, which funds and coordinates medical research in the US. Bass says Kennedy may try to direct the agency and the FDA to produce research into pesticides and food additives that is then used to support litigation trying to change how the US farms. This might shift the FDA away from being an explicitly regulatory agency to more of an activist organization.

His ability to do any of this is likely to be constrained by Brooke Rollins, Trump’s pick for USDA chief, who is seen as a very conventional candidate for the role. Rollins’ chief of staff is Kailee Tkacz Buller, the former president and CEO of the National Oilseed Processors Association. RFK Jr. has consistently attacked oil seeds, writing on X that “seed oils are one of the most unhealthy ingredients that we have in foods” and directing followers to buy hats with the slogan “Make Frying Oil Tallow Again.”

In her confirmation hearing, Rollins indicated that she’d follow the president’s line on agriculture, and President Trump is unlikely to want to upset the farmers and agriculture industry figures who are his natural constituents. “I work for him. I am a cabinet member,” she said at the time.

There are already signs that conservative lawmakers are warming to organic farming. “Historically we haven’t gotten a lot of interest from the more conservative-leaning members of Congress,” says Gorden Merrick, senior policy and programs manager at the Organic Research Farming Foundation, a nonprofit that advances research into organic agriculture.

Now, Merrick says, he’s having a lot more meetings with “very conservative” legislators. “A lot of them did say they’re interested in hearing more about organic because of the influence of RFK and the growth of Make America Healthy Again.”

Pro-organic groups are also shifting how they speak about organic farming in order to appeal to the new administration. America imports a large amount of organic produce, says Kate Mendenhall, executive director of the Organic Farmers Association, a nonprofit that advocates for organic policies in the US. Growing more organic crops domestically will boost farmer’s incomes and US jobs, she says, and the growing demand for organic produce means that there is money to be made from getting in on the organic hype.

Although Kennedy’s support for organic is bringing new followers into the fold, this emerging coalition is still fragile. Organic consumers might lean left, but Trump has overwhelming support from American farmers. Only around 1 percent of US farmland is certified as organic, with the vast majority of farmers reliant on monocrops, feedlots, and pesticides, exactly the kind of farming practices that RFK Jr. opposes. If he did try to tighten up rules on pesticide residue or ingredient labeling, it’s not clear that the majority of farmers would back him.

There is another problem facing this uneasy political pairing. At his confirmation hearing, RFK Jr. struck a conciliatory tone, telling senators he isn’t anti-vaccine, but his dangerously inaccurate views on vaccines, autism, and HIV are well known. Having such a loose cannon in the administration may end up alienating both left-wing supporters of RFK Jr. and more conventional members of Trump’s cabinet, leaving Kennedy and his unusual organic coalition adrift once more.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from this story from Medium:

Is seaweed the most effective way to reduce cattle emissions? This question points to a trend in agricultural industry efforts to tell the public we can have our cake and eat it too. Or in this case, have our climate-intensive beef burgers and call them climate-friendly.

It’s an academic question that keeps getting funding in pursuit of climate-friendly cows. Certainly, as we face the intensifying impacts of a climate crisis in which food production is the number-two source of greenhouse gases, we need every solution on the table.

In a new study out of UC Davis’s School of Animal Science, researchers wanted to see if feeding seaweed pellets to grazing beef cattle could reduce methane emissions from cow belches. It’s a novel take after first trying to adjust the feed of confined beef cattle, and then dairy cattle, with poor results.

Most beef cattle emit the vast majority of lifetime emissions while grazing—before being sent to feedlots, where they live for a short time to be fattened for slaughter, consuming corn, soy, alfalfa, and easily digested feed, thus producing less methane.

However, the UC Davis study required intensive amounts of supplemental feed for grazing beef cattle multiple times a day, which isn’t a viable or realistic solution for grazing systems, where cattle are often left out to pasture. As with most feed-additive studies, the scalability isn’t in reach.

Predictably, the UC Davis study ultimately ignores a crucial reality — that the most effective way to reduce the agricultural emissions of cattle is to eat less beef.

It’s true: Cattle are the leading source of agricultural emissions and a top source of U.S. methane. They’re also a leading driver of deforestation, habitat loss, direct wildlife killing, and species endangerment — and require the most land and water to produce. So while factory farms aren’t climate solutions, grass-fed systems where cattle belch methane for longer periods aren’t either.

The serious industry problems we face need more than just … producing beef slightly differently. The reality is that feed additives aren’t a silver-bullet solution to the ecological problems caused by beef in the first place.

The fact is there’s no solution for “climate-smart” beef that will work without transitioning away from the overproduction of beef. In the United States, we consume more than four times the global average. Just as we can’t “clean coal” our way out of fossil fuels, we can’t “seaweed” our way out of beef’s climate destruction.

Research into drawing down cattle-based emissions is important. But research already conclusively shows the urgent need for dietary shifts. Eating less beef — not feeding cattle more seaweed pellets — is what’s needed. As Project Drawdown, a leading climate research organization, states, “greenwashing and denial won’t solve beef’s enormous climate problem.”

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

omg the setting prompts are so good….how about 10) a dingy truck stop after ten hours on the road or 13) a police station in a foreign country 😊

Thank you so much for the ask!! The ask list is here if anyone else wants to see it =)

Setting prompts 10- a dingy truck stop after ten hours on the road (I've taken slight liberties with the band's actual tour schedule and the number of hours to base this on a truck stop I've driven by many, many times) and 13- a police station in a foreign country (remember that cops can and will lie to you and this probably isn't how it would go in real life).

Matty stumbles off the bus, ridiculously grateful to have stopped, even for just a little while. He lost track of the hours a some point around the state line after traffic and an vacant construction zone meant it took ages to get out of Boise. If he's never back in Boise, it'll be too soon, and now he's at a rest stop somewhere along Interstate 84. He's not sure how much further it is to Portland.

He wanders away from the pumps to the edge of the pavement and lights a cigarette then looks around. There's the freeway and on the other side of it, a river, wide and deep blue and calm, interrupted only by a barge pushed by a tugboat. Matty remembers hearing about salmon runs and dams in this river years ago when he was different, when he didn't just want to go home, but he can't for the life of him remember the river's name. The bluffs on the far side of the river and a dull brown and when Matty surveys the land on this side of the river, then this side of the freeway, he finds it a similar dull color, sagebrush and juniper all dormant for the winter and the grass dead. The sky is the same color as his cigarette smoke. It's kind of miserable, he thinks, and he feels unsettled.

Matty takes another drag from his cigarette and glances back toward the bus and the truck stop. He doesn't really want to go in--more than anything, he'd like some quiet time to himself--but he's almost out of cigarettes and he's kind of hungry, so he finishes his cigarette, stubs it out, and heads towards the door. Inside is a little bit dingy and outdated, like it hasn't been undated since the early 2000s and since then, nothing but motor oil and dirt has been tracked across the floor.

It's kind of sad, Matty thinks, this dingy place in the middle of nowhere, in the middle of a bleak landscape. There's nothing but industrial sites and farms and feedlots for miles and miles and miles, and there'd been a billboard advertising religion along they exit. It all makes Matty feel tired. He is tired. He's so tired and he doesn't handle tired with much grace. He gets clingy and whiny and his temper gets a little bit shorter.

Lost in his thoughts, Matty walks right into another person as he wanders through the aisles. He starts apologizing the second he does, but when he looks up to see George, he cuts his apology off with, "Oh, hi."

"Hey," George responds. "Bit distracted are you?"

Matty sighs. "I'm tired. My knee hurts. I wanna sleep next to you."

"We have a hotel tonight," George offers, resting a hand on Matty's hip.

Matty's instinct is to step away from George's hand and maybe put some space between them because every time he's looked out for the past couple hundred miles, the billboards have been about life beginning at conception and how god is the answer and he's pretty sure this is not a place that would welcome casual, fond touches and love between two men, but he doesn't. He just appreciates the weight and warmth of George's hand and says, "I wanna sleep in our bed. I wanna roll over and see that painting we picked out when we lived in that little flat with all the fairy lights. I want that stupid blanket that you bought me when I was ill last winter."

"Soon," George promises. "We'll be home soon, and until then, there's ibuprofen in my bag and I grabbed you some crisps. You want anything else?"

Matty sighs. "Came in for a pack of cigs," he says. "And my lighter's almost dead. Why are my lighters always dead?"

"'cause your lighters are always lighters you took from me," George responds, easy, like it's obvious.

Matty sighs. "I'm tired," he repeats, following George to the counter. His gait is uneven as he goes, a product of the ache in his knee that's gotten worse lately. He doesn't remember ever hurting it, but there's a lot of his life he doesn't remember, so he's long since let it go.

At the counter, George sets the snacks he'd selected on the counter, asks the cashier for two packs of cigarettes, and adds a lighter from the display before Matty can say a word. He does accept Matty's cash, crumpled from being shoved into his pocket the last time he bought cigarettes at a truck stop, but only when Matty insists, saying he's trying to spend all the American cash he has before they leave the country. The cashier returns the change to George and they head outside, George passing the lighter and one of the packs of cigarettes to Matty as they go.

"Thanks," Matty mumbles, pushing the door open. It's still gloomy outside. He wants to linger, wants to be still for just a few moments, even if only in the lot of a truck stop, but George's hand on his back keeps him moving. He still feels unsettled when they get on the bus, even though it's supposed to be their home away from home. Something is pulling at him, unraveling him. He won't settle until he can wind himself back up, take the strings of himself that are being unwound and tie them back up. Soon, he thinks, remembering George's words, they'll be home soon.

----

Matty doesn't know where he is. He doesn't know what time it is, doesn't know when or how he left the hotel room he and George were sharing, doesn't know where his phone or wallet is. He barely even knows his own name. What he does know is that he's sober. There's no haze in his head, his limbs aren't heavy, and, when he pushes up his sleeve to look at the crook of his elbow, there's nothing but smoother skin, only marked by fading scars from over a year ago. He'd had a couple glasses of wine at dinner and a cigarette on the balcony with George before bed, but he wasn't drunk or high or stoned, so how did he get to be wandering the streets of an unfamiliar city in the snow wearing nothing but a long-sleeve shirt, sweats, and socks that feel morse like George's good wool socks that anything Matty owns?

Matty keeps walking, hoping he can find some sort of landmark and orient himself, hoping that he can remember something, hoping that he can get himself back to the hotel. He doesn't have his room key, but just having somewhere to go would be a good start. He feels like he's going crazy, or maybe that he's past going crazy and he's properly gone crazy. Matty Healy, finally fully mental, just like so many people have thought he was for most of his life.

Matty's not sure how long he walks before the street is suddenly bathed in blue and red light. He keeps walking until a car pulls up alongside him and he glances over to see the word 'police' and his instinct is to run or hide, somehow get out of here because he's heard American cops are more than happy to arrest people on minor drug charges, but he's sober, he knows his is, and his feet hurt, so he stops and looks at the car, blinking at the light. The car stops when Matty does and a few moments later, a young woman walks around the front of the car. She has one hand on the holster on her hip and asks something that Matty doesn't really catch. He's distracted by the lights and the realization that he's cold and the way his feet hurt.

"What?" Matty asks.

The woman, the officer, drops her hand from her holster, evidently deciding that Matty isn't a threat and apparently repeats, "Are you alright? This is a dangerous neighborhood."

Matty sniffs and shakes his head.

"Are you running from something?" she asks, looking down to Matty's feet. "Are you hurt?"

Again, Matty shakes his head. He's pretty sure he doesn't have anything to run from, only things to run towards.

"How 'bout home, then?" she asks. "You're liable to be mugged or attacked alone at night here--I can help you get home if you'd like."

"'m not from here," Matty admits.

"Where are you staying?"

"Erm, I don't know. I need to call George."

"Ok," the officer agrees. "Do you know his number?"

Matty shakes his head again.

"Alright. How 'bout we go back to the station and we'll find George together, ok?"

Matty wants to agree, if no other reason than to maybe be warm for a few moments, but he also doesn't want to be arrested and he still has the paranoia of an addict, so he hesitates.

The officer sees his hesitation and comes around to the side of the car and opens the passenger door, saying, "You haven't done anything wrong. My job is to keep my community safe and you're clearly not safe. We're gonna get you some help, ok?"

Matty hesitates again. The last time anyone said anything about getting him help, he was sent to Barbados alone for seven weeks. "I don't wanna go to a hospital," he says.

"If you're not sick or hurt, you don't have to."

"I'm not," Matty says.

"Just to the station, then," the officer says. "We'll find George and get you back to where you belong."

Matty lets out a breath, then agrees, "Ok," and climbs into the passenger seat. The car is warm and it's nice to be off his feet, even if he's still a little bit anxious about being there and upset about the gap in his memory.

The officer closes the door after he gets in and goes around to get into the driver's seat. Once she closes the door, she fiddles with the temperature controls for a moment, then says, "I've turned the heat up, but you can change it if you like. It's just a few minutes back to the station, ok?"

Matty nods.

The officer nods and puts the car into drive, then turns to check her blind spot and pulls away from the curb. "I'm Officer Harding," she says. "What's your name?"

"Matty."

"I have a cousin we call Matty," Officer Harding says, in a clear attempt to be friendly and make Matty a little bit more comfortable.

Matty doesn't say anything, just looks down at his feet. George's wool socks are ruined.

Officer Harding doesn't say anything else as she drives. True to her word, she pulls into the lot behind the police station after just a few minutes of driving. Once she's parked, she comes around and opens Matty's door, offering a hand to help him out of the car. He doesn't take it, but he lets himself be led into the station, his head down and shoulders hunched.

Officer Harding directs him to a chair next to a desk with a nameplate that reads 'O. HARDING' and asks, "Can I get you a blanket or something to drink?"

Matty sniffs and nods, saying, "A blanket, please?"

Officer Harding offers a smile and goes, coming back a few moments later with a folded blanket that she shakes out and drapes over Matty's shoulders. "Alright," she says, sitting in her own chair, "what's your last name, Matty? I'm going to check the missing person's database and see if someone is already looking for you."

"Healy," Matty says obediently. "An' 's not really Matty, 's Matthew."

Officer Harding nods and types Matty's name in, then makes a few clicks before saying, "Alright, no missing persons report. What about George? Do you know where he lives or is staying?"

"He's staying wherever I'm staying," Matty mumbles.

Officer Harding sighs. "Have you wandered off like this before? Experienced memory loss like this before? Do have any way of contacting anyone? Does anyone have any way of knowing where you are?"

"I’m not a dog," Matty says, looking up. "I don't have a microchip or a fucking GPS tag." Then he ducks his head again to focus on George's ruined socks and says, "Sorry."

"That's alright," Officer Harding says. "I've heard much worse."

"Sorry," Matty repeats.

"What's George's last name? I'm going to see if he's made any calls or reports."

"Daniel."

"Alright," Officer Harding says. She types George's name into a search field and makes a few clicks, then does the same a few moments later. "No calls and I can't look up a phone number. Are you sure you don't know where he's staying or what his number is?"

"I know his number," Matty clarifies, "but we got new SIM cards here and I don't know that number."

"How 'bout the number you do know?"

Matty gives a nod and recites George's number. He knows it by heart and has since George got it. He still knows the number to the landline George had when they were kids. He knows how to find George. He could be dropped in the middle of London blindfolded and get home to George with love alone guiding him, but love doesn't know this city. Love has failed him here, rendered blind, deaf, and dumb. All he can think is that he misses George and he wants to go home. He wants to know he could get home, not be reliant on the pity of another. He wants to not be pitiful anymore.

When Matty glances up, Officer Harding is on the phone. She's quiet while it rings, then introducing herself and says, "I’m looking George Daniel." There's a beat of quiet, then, "Great. I'm here with Matthew Healy, he asked that I call you-"

George is going to be livid, Matty thinks. They're supposed to be through this. He's not supposed to have to worry about where Matty has disappeared to, not supposed to worry if he's gone and gotten himself hurt or killed or arrested, not supposed to feel more like a babysitter than a partner. This is going to put them right back to where they were two years ago when Matty tattooed his passport number or his wrist because no one trusted that he wouldn't do something like try to drain his bank accounts or swap his passport for drugs or simply get it stolen because the only thing he cared about was getting high. This going to make things bad again, and on top of that, Matty has ruined George's socks.

"Matty?" Officer Harding asks, putting a gentle hand on his arm.

Her hand is warm Matty thinks as he glances up. He doesn't want her to move it.

"I got ahold of George. He'll be here in about twenty minutes."

"George is coming?" Matty asks, more shocked than anything else. "Is he upset?"

Officer Harding frowns at that, but says, "He didn't sound upset. He sounded grateful that I called. He asked if you were safe and where you were."

"And he's really coming?"

"I think so."

George is coming, Matty thinks. George is coming and everything will be ok and Matty will be safe, but oh, god, he doesn't know what happened or where he is or how he got there and he's ruined George's socks and he's a liability again and Matty is about to be sick. He looks around frantically and reaches for the little trash can by the desk just into to vomit into it, rather than on the floor.

Officer Harding waits for Matty to be done and set the trash can back on the floor, then rolls her chair a little bit closer and carefully asks, "Are you safe with George?"

Matty can't help but let our a laugh at that. It sounds foreign to his own ears and he says, "Yeah. I'm safe with George. George is safe. He's, I'm, he loves me. We're just supposed to be past this."

"Past this?"

Matty nods. "Past me being a liability."

"One night doesn't make you a liability," Officer Harding tires.

Matty scoffs. "There have been a lot of nights. And mornings and nights and days."

"So you have experienced an episode like this before?"

Matty shakes his head. "Didn't say that, said this is the first time this has happened."

"I can try to connect you to some community resources," Officer Harding offers.

Matty just shakes his head and pulls his knees up to his chest, heels resting on the edge of the chair. If he can make himself smaller, maybe this can get smaller, too.

Officer Harding lets it go after that, just turns back to her desk. Another ten or so minutes pass before Matty hears a ding and he twists around to see George following the desk sergeant off the elevator. Matty feels like he can breathe again and he gets up to quickly cross the open room and fling himself into George's arms, not minding that they're in the middle of a foreign police station. George accepts him, he always does, with arms wrapped tight around Matty holding him close.

"Hey," George murmurs, rubbing Matty's back gently.

Matty clings. George is warm and he smells good and he's safe and solid. "'m sorry," he chokes out. "I didn't take anything. I'm sober. I'm sober, George, I promise."

"I got you," George murmurs. "I'm right here. I've got you."

"I don't know what happened," Matty continues, on the edge of tears. "I don't know why I left or where I went, I just, I don't know."

"Shh, 's ok," George says. "We'll sort it out, whatever it is."

"I'm sorry," Matty repeats.

"No need to apologize," George says. "There's nothing for you to apologize for."

"There is," Matty insists. "I ruined your socks, the good wool ones you like that you give me sometimes when I get cold and now you're never going to give me your socks anymore 'cause I ruined them and-"

"Matty, love," George interrupts, "I don't care about that, I care that you're ok."

"Am I ok?" Matty asks. He has to. He doesn't know the answer.

"You will be," George promises. "We'll go back to the hotel and get a little more sleep, 'cause you look exhausted and it's three in the morning, and when we wake up, we'll figure out whatever this is."

"Really?"

George nods. "You and me," he says. "We can figure anything out, even you."

Matty laughs at that, a little bit wet from tears, but George is right. They've figured him out once before, they can probably do it again. "Love you," Matty murmurs. "Thank you.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

[“While “essential workers” in the poultry industry were made to feel dirty, nonessential workers in fields like finance and computer engineering—the “people with laptops”—were sheltering in place, more distant from what transpired in industrial slaughterhouses than ever before.

Thanks to FreshDirect and Instacart, consuming meat no longer even requires coming into contact with a deli butcher or grocery clerk. With a few taps on a keyboard or the swipe of a screen, consumers can get as much beef, pork, and chicken as they want delivered to their doors, without ever having to think about where it comes from. And yet, as the popularity of bestselling books like Michael Pollan’s The Omnivore’s Dilemma and Jonathan Safran Foer’s Eating Animals attests, a lot of Americans do think about this. In recent years, more and more consumers have begun to carefully scrutinize the labels on the packages of the meat and poultry they buy. The ranks of such consumers have grown exponentially, paralleling the rise of the “good food” movement, which promotes healthier eating habits and reform of the industrial food system.

Although the movement is, in Pollan’s words, a “big, lumpy tent,” composed of a broad coalition of advocacy organizations and citizens’ groups that sometimes push for competing agendas, one of its aims is to persuade consumers to become more conscientious shoppers and eaters. Among those who put this idea into practice are so-called locavores, who buy food directly from local farms, ideally from small family-run enterprises that embrace organic, sustainable practices: ranchers who raise grass-fed cows that never set foot in industrial feedlots; farmers who sell eggs that come from free-range chickens reared on a diet of seeds, plants, and insects rather than genetically engineered corn and antibiotics.

Locavores engage in what social scientists call “virtuous consumption,” using their purchasing power to buy food that aligns with their values. The movement appeals to the growing number of Americans who want to feel more connected to the food they eat and to the people who raise it, with whom locavores can interact directly at farmers markets or through community-supported agriculture programs. It is a captivating vision, and the benefits of eating locally grown food—which is likely to be more nutritious, to come from more humanely treated animals, and to be better for the environment—are manifold.

But locavores have some blind spots of their own, most notably when it comes to the experiences of workers on small family farms. As the political scientist Margaret Gray discovered when she set about interviewing farm laborers in New York’s Hudson Valley, the vast majority of these workers are undocumented immigrants or guest workers who toil under abysmal conditions, often working sixty- to seventy-hour weeks for dismal pay. “We live in the shadows,” one worker told her. “They treat us like nothing,” said another. In her book Labor and the Locavore, Gray asked the butcher on a small farm why so few of his customers seemed to notice this.

“They don’t eat the workers,” the farmer told her.

“He went on to explain that, in his experience, his consumers’ primary concern is with what they put in their bodies,” Gray wrote, “and so the labor standards of farmworkers simply do not register as a priority.”]

eyal press, from dirty work: essential labor and the hidden toll of inequality in america, 2021

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

Boosting Kenya's Livestock Sector: How the Establishment of 450 Feedlots in ASALs Could Transform Meat Production

Learn how Kenya’s plan to establish 450 feedlots across ASAL counties is set to transform livestock production, addressing the country’s 60% feed deficit and boosting red meat supply. Discover how modern feedlot farming and sustainable rangeland management can help Kenya overcome feed shortages and improve livestock productivity for local and global markets. Explore Kenya’s livestock sector…

#animal genetics breeding#ASAL counties feedlots#commercial livestock farming#feedlot farming Kenya#Kenya livestock production#livestock disease control Kenya#livestock farming innovations#livestock feed deficit#livestock industry Kenya#pastoralist livestock feed#protein demand Kenya#rangeland management Kenya#red meat production Kenya#sustainable livestock practices

0 notes

Text

Expert Construction Company Australia - Entegra Signature Structures

Looking for a reliable construction company Australia? Then you have us! we at, Entegra offer tailored solutions for both residential and commercial projects. With a focus on quality and sustainability, we ensure your project is completed on time and within budget. Hire us today! To know more view this infographic or visit the link.

#construction projects#construction company Australia#Construction Solutions#Dairy Sheds#Industrial Sheds#Feedlot Sheds#Equine Arenas#Hay Sheds#Rural Farm Machinery Sheds#Horticulture Sheds and Buildings#Industrial Buildings#COLA’s#Cotton Sheds#Entegra Signature Structures

0 notes

Note

Recently I've seen a lot of people argue that the water use of foods like beef are overstated because the majority of its water usage is comprised of green water and I don't really know how to respond

I’d need to see their source (and you should ask for that first) but only about 10% of beef cattle in the US are completely free ranging, and therefore mostly use green water. Most cattle are at least finished in feedlots where water use is intensive, if they’re raised in a factory setting their entire lives.

It also depends where you are. Most regions where cattle raising is most prominent don’t see enough rain for cattle to use mostly green water. Again I don’t know where these people are talking about, but in the US, beef uses 500 times its weight in blue water alone. That is five times the water intensity of even the thirstiest protein sources, with only almonds coming anywhere near that level.

None of this includes water used for anything other than drinking for cattle. What about the water raised to grow their feed crops? What about waste water run off and contamination, which is infamously high impact. I think I know the study they’re probably referring to here and it only factors in water produced and used by the cattle farmers themselves, not the rest of the supply chain, which is very limited.

It’s interesting that beef and leather advocates are so interested in this particular study, when they have ignored everything else that the Water Footprint Network have ever published. This is how it always goes with environmental science. You have a wide consensus gathered through decades of research, then you get one limited study that seems to contradict that consensus, so those with a vested interest leap on it, at the exclusion of all other established conclusions. This is the ‘one true study’ because I agree with its findings.

When you dig into it though, you figure out that the study doesn’t actually contradict anything, it is just looking at something quite limited, or their conclusion has been massively misunderstood or overstated, as in this case. If they are referring to the study I think they are, they are wildly misrepresenting what it was actually measuring.

If someone raised this to me, I’d start by asking them their source, then I’d ask some questions. This is from 14 years ago, do we think this is still accurate, considering the continued shift to intensive farming, and the fact that the conclusion you’re drawing from is contradicted by more recent studies? What was this study actually measuring? Just farm water use? Where in the world? Are most cattle raised 100% pasture? What about intensive farms and feedlots? Do you the rest of the supply chain might be where a lot of the blue water use is coming from? That should be enough to reveal the obvious weaknesses in drawing big conclusions from limited data sets.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just pulled some frozen farm-raised deer out of the freezer to thaw in the fridge. I saw it on sale, and couldn't resist picking some up. Both because I just like deer meat, and with the aim of turning it into oven jerky. Deer is certainly more than lean enough, and talk about traditional choices of meat for that.

But, I couldn't help but think some again about how much my own life has changed in some ways. As witnessed by readily finding (the "wrong" species of) deer meat in grocery stores, alongside moose and reindeer--which are both just sorta variations on a theme, and also too tasty for their own good btw. And of course that being the best way for me to get hold of any deer meat these days.

Nobody in our house hunted deer, so we didn't have a steady supply of it back home. But, it wasn't unusual for somebody we knew who did hunt to share around extra meat, or (most commonly) enlist help clearing out whatever's left in the freezer from last season to make room for this year's meat.

The only deer we ever brought in was one that jumped out in front of my mom's Ford Festiva. And she practically had to fight some dude to keep him from "helpfully" loading the carcass into his pickup to haul it away before the game warden could get there to record it. (No joke, I was in the car with her and witnessed that. That guy didn't realize just how close he came to an ass kicking.)

So yeah, that was one of the most expensive deer ever. And the meat really wasn't that good, between the bruising and the weather being too warm to hang it properly. But, you can bet she wasn't going to waste all that meat anyway. The price you pay for smashing somebody's radiator in, I guess.

I'm still not quite used to the idea of deer being sold period, or farmed. Gotta say that I am still personally ethically iffy on farmed meat in general, but at least a little less so in this country. They may not be out living their best autonomous cervid lives in the woods before some two-legged predator rudely interrupts that, but welfare standards are high enough that I feel a little better about it in general. Plus I don't think anybody has been trying to cram deer onto feedlots. That's not gonna work out so well, if not in quite the same ways as with bison.

I also couldn't help but think again about one guy I used to know, if not that well. More of a friend of a friend--actually one of my friend's partner's hunting buddies and general buds.

Guy called Buck (how appropriately!), who lived way up on a mountain somewhere in the only household I knew of without indoor plumbing. I had to take my friend's word on that, because I never went over there.

Buck was a vegetarian bodybuilder who practically lived off store brand peanut butter--and also hunted deer A LOT for his family without a lot of regard for season, because they really needed the food. I was an ethical vegan myself at the time, and could definitely respect that.

Seemed like a pretty cool guy, and I hope he's doing OK, whatever he's up to these days.

So yeah, now I guess I'll just be over here adding frozen mystery deer to my grocery delivery order when I spot it on sale.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Our online spaces are not ecosystems, though tech firms love that word. They’re plantations; highly concentrated and controlled environments, closer kin to the industrial farming of the cattle feedlot or battery chicken farms that madden the creatures trapped within."

12 notes

·

View notes