#pastoralist livestock feed

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Boosting Kenya's Livestock Sector: How the Establishment of 450 Feedlots in ASALs Could Transform Meat Production

Learn how Kenya’s plan to establish 450 feedlots across ASAL counties is set to transform livestock production, addressing the country’s 60% feed deficit and boosting red meat supply. Discover how modern feedlot farming and sustainable rangeland management can help Kenya overcome feed shortages and improve livestock productivity for local and global markets. Explore Kenya’s livestock sector…

#animal genetics breeding#ASAL counties feedlots#commercial livestock farming#feedlot farming Kenya#Kenya livestock production#livestock disease control Kenya#livestock farming innovations#livestock feed deficit#livestock industry Kenya#pastoralist livestock feed#protein demand Kenya#rangeland management Kenya#red meat production Kenya#sustainable livestock practices

0 notes

Note

Can we see more about pyliod....he's so silly. ♥️ kissing him on the head.

I'm obsessed with how khait mimic real world bulls but also goats in their behaviors. are there any other behaviors/traits they mimic from IRL animals?

Which leads me to the question: what separates livestock from pets?

Esp for brakul, I'm assuming the animals he lived around when he was younger were livestock and meant for eating - but what if you had a favorite? Was it different for janeys? Hibrides?

Also leads me to another question: fish keeping - is it a hobby? Are fish just seen as food or can they be considered decorative?

(please forgive any spelling errors it's 1 in the morning for meeee)

Don't know if you saw this post but this gives a good rundown of khait behavior. They're based on wildebeests and most of the descriptions of their social behavior are accurate to them, other aspects of their behavior is pulled mostly from other bovids (other antelopes mostly. l swear I saw urine self-anointing+wallowing by topi or hartebeest or smth in a documentary once, but in terms of bovids that might just be a goat thing. Cervids also do that). Not much of their behavior is actually based on cattle, besides using cattle as a model to inform the concept of a hypothetical domesticated antelope. There's also some horse influence, though in that case it's pretty much exclusively to inform the concept of a non-horse domestic ungulate used Primarily for riding, and their interactions with humans.

The like, general definition of distinction between livestock/pets would be a venn diagram between 'livestock' 'working animals' and 'pets', with livestock being animals raised for production (meat, wool, fur, leather, eggs, milk, etc), working animals being used for physical labor or otherwise performing utilitarian 'jobs' (plow animals, riding animals, ratters, herders, guardians, etc), and pure pets having no directly 'productive' role and exist for companionship, ornamentation, etc (though the definition of a pet can be pretty nebulous, especially if you're framing it around emotional attachment instead of the lack of a productive angle). These categories can heavily overlap.

This is just a generalized answer (not even in-universe). How a culture defines these concepts separately (if it does at all) is going to vary extensively.

Brakul grew up surrounded by livestock/working animals and virtually no animals kept EXCLUSIVELY for companionship. The core subsistence method is a mix of settled agriculture (producing primarily grain) and seasonal pastoralism of cattle and horses (producing primarily dairy and wool), occasionally supplemented by hunting and fishing of wild game. The diet revolved around dairy and grain with meat being eaten irregularly, especially for people who aren't rich (which in this particular context is primarily measured in the quality and quantity of livestock- someone wealthy in cattle can afford to slaughter more frequently). Slaughtering a cow is a special occasion. Brakul's clan was on the lower end of the livestock wealth scale, so he ate meat infrequently and almost never his Own livestock (mostly eating hunted/fished game, meat given as gifts or in trade, meat provided by the ruling clan by social obligation).

(This is also broadly true of animal husbandry in Real Life across history prior to industrialized farming- most livestock is more valuable alive as a continuously replenishing resource (milk, wool, eggs, pulling plows, etc) and thus would be slaughtered for personal use infrequently. In class stratified societies, the majority of animals raised for meat would often feed upper classes rather than the people actively involved in rearing them. Some pastoralist societies will rarely or virtually never slaughter their animals for meat, as they are wholly relied on for products they produce while alive.)

So Brakul existed in a context where it was very possible to get attached to livestock and working animals. A lot of basic survival revolved around the dairy and wool the livestock provide, there are high emotional stakes in their survival and well-being, so personal attachment to these animals (even those likely destined for slaughter) can come naturally and be beneficial. The concept that's more alien to him is pure companion animals that don't really do anything directly productive. House dogs kind of freak him out because they're SO different from the dogs he was used to (extremely independent livestock guardians that don't really bond with people, and herding dogs that bond readily with their owners but are notably intelligent and self-sufficient). Encountering dogs that are utterly dependent on their owners and desperate for human attention was like 'what the fuck is wrong with that thing? sad'.

Pretty much the exact reverse situation for the characters from noble families. They would rarely be in close contact with livestock or subsistence level working animals (if anything, they/their families own land and livestock that is entirely raised by peasant workers), and instead would have most contact with pets/ornamental animals/leisure type working animals (hunting dogs, sport khait), and animals used in transportation (cart khait and oxen). They have VERY clear, clean-cut delineations between 'pet' and 'food' (though still not as much as is common in industrialized societies where most people are completely and utterly disconnected from the sources of their food. They're still Connected to the process, seeing animals being slaughtered is a part of daily life). They also would have eaten meat on a much more regular basis, while having little to no personal involvement in its production.

Wardi culture as a whole is not big on companion dogs (there are a few companion dog 'breeds' within the region, but most are hunting or herding dogs). Polecats are by far the most common companion animal in this cultural sphere (they technically fill working functions as ratters, but are mostly kept as housepets). Other animals kept purely as pets are mainly ornamental fowl and ducks. There's also a kind of pygmy horse breed that is kept as a companion animal (reminder that horses in this setting share the size range of goats).

Faiza, Couya, Janeys and Hibrides all grew up with pet polecats and hunting dogs, and sport khait owned by their families. Hibrides had pygmy horses as a kid. In the present day, Janeys' household has two hunting dogs that he doesn't like all that much, he also got two polecats for his children (one of which died tragically after being thrown from a window by his eldest), and has 14 total khait (12 of which are Brakul's) (technically owns another herd and a herd of cattle, but has nothing to do with them. It's an investment). Faiza likes dogs quite a bit and owns three bred hunting dogs and one feral dog she took off the street, also two khait (she owns land and the animals are kept there).

Re: fishkeeping. There's going to be plenty of variation in a global context, but broadly speaking keeping fish as a hobby/for display/other non-meat purposes is going to be on the rarer side in this setting. This is a limited practice in Imperial Wardin (you'll get the occasional wealthy home keeping fish in a courtyard pool but there's no traditions built around it). In terms of nearby civilizations, it's a much more significant practice in Bur, where water gardens with ornamental plants and fish are integrated into temples, city layouts, and wealthy homes.

#Also keeping animals PURELY for companionship is going to be rare in this setting overall. The vast majority of the world's population#is existing at subsistence level and maintenance of an animal that provides no practical benefit in return (as much as one can argue#that emotional companionship is a practical benefit) is unsustainable in a lot of contexts.#Though sometimes the 'practical benefit' can be intrinsic to the animal enough to lower this barrier- ie any dog can benefit its owners#by barking to alert of intruders (and may be able to mostly fend for itself and not require a massive investment in resources)

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

From ancient fertilizer methods in Zimbabwe to new greenhouse technology in Somalia, farmers across the heavily agriculture-reliant African continent are looking to the past and future to respond to climate change.

Zimbabwe

A patch of green vegetables is thriving in a small garden the 65-year-old Tshuma is keeping alive with homemade organic manure and fertilizer. Previously discarded items have again become priceless.

“This is how our fathers and forefathers used to feed the earth and themselves before the introduction of chemicals and inorganic fertilizers,” Tshuma said.

He applies livestock droppings, grass, plant residue, remains of small animals, tree leaves and bark, food scraps and other biodegradable items like paper. Even the bones of animals that are dying in increasing numbers due to the drought are burned before being crushed into ash for their calcium.

Somalia

Greenhouses are changing the way some people live, with shoppers filling up carts with locally produced vegetables and traditionally nomadic pastoralists under pressure to settle down and grow crops.

“They are organic, fresh and healthy,” shopper Sucdi Hassan said in the capital, Mogadishu. “Knowing that they come from our local farms makes us feel secure.”

The greenhouses also create employment in a country where about 75% of the population is people under 30 years old, many of them jobless.

Kenya

In Kenya, a new climate-smart bean variety is bringing hope to farmers in a region that had recorded reduced rainfall in six consecutive rainy seasons.

The variety, called “Nyota” or “star” in Swahili, is the result of a collaboration between scientists from the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization, the Alliance of Bioversity International and research organization International Center for Tropical Agriculture.

The new bean variety is tailored for Kenya’s diverse climatic conditions. One focus is to make sure drought doesn’t kill them off before they have time to flourish.

--------

Other moves to traditional practices are under way. Drought-resistant millets, sorghum and legumes, staples until the early 20th century when they were overtaken by exotic white corn, have been taking up more land space in recent years.

Leaves of drought-resistant plants that were once a regular dish before being cast off as weeds are returning to dinner tables. They even appear on elite supermarket shelves and are served at classy restaurants, as are millet and sorghum.

This could create markets for the crops even beyond drought years

#solarpunk#africa#indigenous knowledge#community#climate smart agriculture#knowledge weaving#cultural interface

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Animal Husbandry: The Sustainable and the Disastrous

Several studies have challenged, and disproven the claims made in the Tragedy of the Commons by Garrett Hardin. Yet the narrative is still pervasive, used to justify forced assimilation of indigenous people (especially nomadic cultures), closing off land and resources from communities for "conservation" efforts, and/ or using the land for more "productive" endeavors such as intensive farming and mining.

While land degradation can happen from frequent tilling, monocultures, land exhaustion, overgrazing and trampling, it's very rare for small-scale (and usually indigenous) communities to practice these destructive practices. It's only when animal-raising expands well past subsistence that it becomes unsustainable for the environment, and can lead to famine along with loss of biodiversity.

In this post I will be expressing the importance of animals and the benefits of pastoralism on the environment, examining unsustainable animal-raising practices that do lead to environmental destruction, and explaining practices people can adopt to improve upon animal agriculture.

Animals, including humans, are unquestionably vital to the environment. To such a degree that forests would disappear without primates. Herbivores are essential for the spread of plant seeds, and carnivores are essential to keep herbivore populations in check so they don't overgraze. But what happens when humans keep livestock?

If you're not familiar with pastoralists, they are self-sustaining societies who manage domesticated animals, usually travelling to ensure adequate grazing opportunities for their livestock. Pastoral communities are often blamed for desertification due to overgrazing, but there's proof that rainfall (or rather, the lack of) is the cause of vegetation loss, and grazing animals managed by pastoralists reduce nitrogen emissions, rather than adding to it (which is observed in large-scale animal agriculture).

It seems that much of the overgrazing syndrome has stemmed from prejudice, political conflicts, and lack of ecological knowledge. We should not base conservation practice on such a shaky foundation. (Gilbert 2013)

The misconception and deliberate lies against pastoral communities are maintained by industrial farmers and their benefactors, who ironically are one of the leading causes of climate change and environmental degradation. Intensive farming results in water and air pollution, which disproportionately affects poor communities surrounding farms.

Overgrazing does exists, and does contribute to devastation, but it's not caused or perpetuated by pastoralists. While some communities can stray from subsistence-based lifestyles for status (such as using livestock as a marriage dowry), or trading (or even being forced to pay fur taxes at the threat of genocide, such as yasak), pastoralists rely on their environment, and cannot overexploit resources without famine.

Large-scale animal agriculture, however, does not depend on immediate surroundings. Animal feed is produced elsewhere and is transported to the farm, where they can have enormous populations of animals condensed in one area.

In Dark Emu by Bruce Pascoe, we can see how livestock managed by colonists in Australia lead to land degradation (relying on the written accounts of early European explorers).

While David K. Wright blames pastoralism as the unintentional creation of the Sahara desert, I would argue that if humans contributed to its creation, emerging hierarchies and condensed settled populations in cities who needed to outsource food production, would be to blame.

We know that early agriculture relied on irrigation and ploughing the earth (the intensity of which made early european farmers more jacked than modern athletes lmao) to keep up with production, since the land wasn't allowed to rest and soil nutrients were depleting. Many civilizations reliant on irrigation crumbled because of salinization of soils, and we have recent records of desertification because of saline irrigation. We also have memory of the American dust bowl caused in part by intensive tilling. These could have sparked the beginning of desertification by encouraging albedo, poor water retention because of less extensive root systems, and decreasing transpiration that reduced overall rainfall.

(Though I wouldn't vilify horticultural/ small-scale crop management, as many MANY cultures have practiced sustainable farming. I expanded on this in another post, since permaculture is literally based on traditional knowledge)

In Rome's Fall Reconsidered by Vladimir G. Simkhovitch, we're presented with two recorded accounts of pastoralism emerging to survive the new, degraded environment.

As the productivity of the soil diminished, and the crops could no longer repay the laborer, then the same process that occurred in England in the 15th and 16th centuries, the turning of arable land into pasturage, began in Italy, about two centuries before Christ. In Rome, too, this process was met by hostile legislation, as was the case in England, but without avail. As in England, so in Rome, it became a matter not of choice but of necessity, although even the thinking heads of both nations refused to admit it at the time, and preferred to ascribe the change to greed and corruption. In England they blamed the poor sheep; in Rome they blamed the attractions of city life. (Simkhovitch 1916)

Now that we've established that subsistence-based pastoralists don't contribute to land degradation, I can discuss the details of sustainable animal husbandry. Most pastoralists I've researched did and do not use their domesticated animals for meat- though, they did enjoy meat when the animals died naturally. Rather, they were primarily raised for milk, blood, as hunting companions, and/ or for labor, which means people had a small herd herd to maintain. (Past tense used because many pastoralists have been forced to abandon traditional lifestyles due to government pressure)

Prior to forced settlements (such as the ones affecting Mongolian pastoralists today), domesticated animals would graze a large area of land, never disrupting vegetation regeneration. Some people, such as the Evenki (previously known as the Tungus), form strong bonds with their animals and let them mingle with undomesticated animals for better foraging skills and improved health.

While a majority of pastoralists live in harsh climates -tundras, taigas, deserts, mountains, etc-, some have integrated grazing livestock in forest settings. A managed grazing in woodlands is called silvopasture, which is usually accompanied by managed plant life; agroforestry. So if nomadic grazing isn't an option (fuck borders, fuck private property 🤬), silvopasture is a great way of raising animals! Other resources can be grown in the grazing area, like the dehesa system.

Rotating plots of land, to let the soil rejuvenate, is also a good practice. You can border livestock enclosures with bags of mushrooms for mycofiltration, to reduce contamination (oyster and stropharia can digest e.coli).

Choosing deep-rooted plants, and fast growing plants for fodder would be ideal. Animals can even be trained to eat weeds such as kudzu and azolla, both of which grow extremely fast. While a diverse diet works best for overall health, supplementing the diets of herbivorous mammals with certain types of algae can significantly reduce their methane production. I'm talking 90% reduction when algae is 1-2% of their diet.

Learning about pastoralists and their traditional practices is a key part of raising animals sustainably. Our current system of large-scale destructive farming is not an accurate reflection of the mutually beneficial relationship between humans and animals. Animal husbandry doesn't need to be disastrous, and historically, it never was.

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lupine Publishers | Pastoralists’ Perception of Resource-Use Conflicts as a Challenge to Livestock Development and Animal Agriculture in Southeast, Nigeria

Lupine Publishers | Scholarly Journal of Food and Nutrition

Abstract

One of the major but hidden challenges to livestock development and animal agriculture the world over is resource-use conflicts between crop farmers, pastoralists and other land users. This is so because during conflict situation, almost all human livelihood activities come to a standstill including livestock farming. This study therefore sought to examine how conflicts involving different land users hinder livestock production. Questionnaire and oral interview were used to obtain information from a total of 120 pastoralists in three selected states of Southeast (Abia, Enugu and Imo). Data were analyzed using percentages, mean and standard deviation. The results showed that the mean age of pastoralists was 38, and the mean household size was 10, mean herding experience was 18. The following were the causes of resource-use conflicts - blocking of water sources by crop farmers with a mean (M) response of 3.30, farming across cattle routes (M = 2.95), burning of fields (M = 3.30), theft/stealing of cattle (M = 3.40), among others. The factors attracting the pastoralists to the study area were availability of special pasture (M=2.37), availability of land for lease (M=2.52), water availability (M=2.60) among other reasons. Conflicts, therefore, affect livestock production in the following ways - unsafe field for grazing, poor animal health, loss of human and animal lives, abandonment of herds for dear life and many others.

Keywords: Animal; Agriculture; Conflict; Livestock; Pastoralists

Introduction

In Nigeria, grazing lands are rarely demarcated, and this large sector of agriculture always suffers compared to crop farming or fruit plantation [1]. The latter two are mostly demarcated favorably for the fact that most people are sedentary, and areas needed are small. The establishment of demarcated rangelands and passageways (cattle corridors) allow the livestock to access water points and pastures without causing damage to cropland [2]. Pastoralists usually graze over areas outside farm lands, and these have been accepted to be the norm from time immemorial. Their movements are opportunistic and follow pasture and water resources in a pattern that varies seasonally or year-to-year according to availability of resources [2].

Livestock production in the form of pastoral livestock keeping is among the most suitable means of land use in arid areas of Africa because of its adaptability to highly variable environmental conditions. In Nigeria, most pastoralists do not own land but graze their livestock in host communities [3]. While a few have adopted the more sedentary type of animal husbandry, the increasing crises between farmers and pastoralist presupposes that grazing is a major means of animal rearing in Nigeria. The livestock sector in Nigeria is plagued by several challenges such as lack of adequate supplies of quality feed and pasture, diseases, weak market network, unavailability of adequate water and poor veterinary services [4- 7], reiterate that the sector is constrained by institutions, markets and policy as well as technical issues. More recently concern on herdsmen-farmers’ conflicts has appeared in literature and policy discourse as one of the formidable challenges facing livestock production (particularly ruminant) in many developing countries. Resource-use conflicts in Nigeria have persisted and stands out as a threat to national food security, livestock production and eradication of poverty with pastoralists often regarded as the most vulnerable. Resource-use conflicts not only have a direct impact on the lives and livelihoods of those involved, they also disrupt and threaten the sustainability of agriculture and pastoral production in West Africa [8]. So many land users make their livelihood within the same geographical, political, and socio-cultural conditions, which may be characterized by resource scarcity [9] or political inequality and population pressure. Pastoralists are believed to be more vulnerable compared with farmers because their cattle can be confiscated and/or seized and released only on payment of a fine. Besides, sometimes they are in the minority and could lack political power to their advantage [10].

Resource use conflicts/clashes according to Adisa and Adekunle [11], are becoming fiercer and increasingly widespread in Nigeria. A study of 27 communities in central Nigeria by Nyong and Fiki [12] shows that over 40% of households surveyed had experienced agricultural land-related conflicts, with respondents recalling conflicts that were as far back as 1965 and 2005. Okoli and Atelhe [13], showed that about 13 cases of farmer- herdsmen conflicts across states of the federation which claimed 300 lives of the citizens. In Abia, Enugu and Imo States, there have been cases of conflicts between pastoralists and crop farmers in Umunneochi, Ugwunagbo Uzo-uwani, Nkanu-West,Udi, Ohaji/Egbema, Owerri West, and Okigwe areas of the States over crop destruction by cattle, killing of herders and stabbing of farmers following reprisal attack on different occasions [14]. Therefore, the study examined challenges of resource-use conflicts to livestock production in the Southeast region of Nigeria. It specifically sought to: describe the socioeconomic attributes of respondents; b. examines causes of conflicts as perceived by the pastoralists; c. identifies factors that attract the pastoralists to the state; and, d. ascertain challenges of resource-use conflicts to livestock agriculture.

Methodology

This study was conducted in Southeast agro-ecological zone of Nigeria. The zone lies within latitudes 5oN to 6oN of the equator and longitudes 6oE and 8o E of the Greenwich meridian. Southeast Nigeria is made up of five (5) states-Abia, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu and Imo. The zone occupies a total land mass of about 10, 952, 400 hectares with a population figure of about 33,381,729 persons in 2018 projected from 2006 National Population Commission Census figure [15]. About 60-70% of the inhabitants of the zone are observed to engage in agriculture, mainly crop farming and animal rearing [16]. The 2-stage sampling technique was adopted in the process of sample selection. The first stage was the purposive selection of three states from the Southeast agroecological zone where cases of farmer-pastoralists conflicts have occurred and were reported (Abia, Enugu and Imo). The second stage involved the random selection of 120 pastoralists from the list of 180 pastoralists from their various camps in the three states. Both primary and secondary data sources were used. Simple descriptive statistics such as mean, percentage, frequency distribution was used to analyze the socio-economic characteristic of the respondent. Objective 1 was analyzed using percentage presented in table. Mean was computed on a 4-point Likert type rating scale of strongly agree, agree, disagree and strongly disagree assigned weight of 4,3,2,1 to capture the perceived causes of the conflicts (objective 2) and challenges of conflicts to livestock development (objective 4). The values were added and divided by 4 to get the discriminating mean value of 2.5. Any mean value equal to or above 2.5 was regarded as a major factor causing conflict and challenge to livestock development, while values less than 2.5 were regarded none. Again, mean was also computed for objective 3 which looked at factors attracting pastoralists to the area on a 3point Likert type rating scale of very serious, serious and not serious assigned values of 3,2,1. The values were added and divided by 3 to obtain a discriminating mean value of 2.0. Any value with mean equal to or greater than 2.0 was considered very serious and vice versa (Figure 1).

Results and Discussion

Socioeconomic Characteristics of Respondents

Table 1 showed that 83.3 percent of the pastoralists were married, while 16.6% were single. The predominance of married people among the pastoralists could be attributed to the complementarity experienced in farm labour provision at the household level. The man, woman and children pool their physical reserves to keep the arm on course. It is worthy to note that there are potential soldiers at the event of land use conflict. Whereas 85.8% of the pastoralists had quranic education, 10 percent had primary education, then, only 4.2% had no formal education. The pastoralists, all (100%) belonged to social organizations; Islamic unions and or herder unions. These respondents who belonged to social organization will likely benefit and share knowledge and experiences through contacts and cross-fertilization of ideas. The organization could also provide forum to plot, plan and execute attack.

The table reveals that 47.5 percent of the pastoralists indicated that the animals are not their own but that of military officers, retired and serving. Some of the animals are also owned by alhajis and traditional rulers in the north (29.2%) who have established contacts with their kits and kins to protect their interest where ever they may be. Also, 20.8 percent and 2.5 percent respectively are owned by the pastoralists themselves and few politicians who also trade in animals. The result explains the effrontery of the pastoralists and their seeming more powerful than the natives who are always helpless at their audacity. The mean age range was 38 years. This implies that the pastoralists are also young and can endure the difficult nature of their practice of trekking very long-distance day and night. The average herding experience was 18 years. Experience is a valuable asset. The years of experience of the pastoralists could enable them to relate encounters they had; causes, effects and resolution. The mean herd size was 61. This is indeed large, and it reveals the fears of the crop farmers should cattle numbering into 30-100 invade their farms. A great deal of damage would be done, livelihood activities may be lost, food insecurity enthroned in addition to accentuated poverty. The average monthly income was N53,500.00. The pastoralists in their course sell the cattle and they also reproduce under their care.

Perceived Causes of Resource-Use Conflicts in the Study Area

Table 2 showed the pastoralists perception of the causes of the conflicts involving them and the crop farmers. Although they may seem to blame crop farmers or shy away from reality of telling the truth. To them the causes of the conflicts included blocking of water source by crop farmers (M= 3.30), farming across cattle routes (M = 2.95), limited grazing areas (M = 2.70), burning of rangeland/field by crop farmers (M = 3.28). They claim that farmers block the wells, ponds and river routes where their animals drink. They also assert that farmers set their grazing areas ablaze and farm across their animal routes thereby hindering their movement. Other causes of conflict were claim of land ownership (M = 2.64) by the farmers; farmers fight herdsmen (M = 3.00), setting of traps along the cattle way (M = 2.74), harassment of pastoralists (M = 3.01) by the youths, stealing/theft of cattle (M = 3.40), and poisoning of water source (M = 2.80). The pastoralists see land as a free gift of nature and as such nobody should prevent others from the use of it and make laws regarding it against others. To them, land is for all and should be used as desired.

Factors Attracting Pastoralists to the Study Area

Table 3 showed that several factors attracted the Fulani pastoralists to the state. Among the factors were water availability with a mean (M) response of 2.60 and availability of land to lease with mean score of 2.52. Water is life of both man and animals and the availability of streams and rivers in the Southern part of Nigeria becomes a reason for the pastoralists’ invasion of Imo state. Again, even during the dry season, water sources remain intact as families get water either from streams, rivers and even ponds. Land for lease or rent (M=2.52) to the head of the pastoralists is also available. These lands are mostly abandoned land not good enough for immediate crop production. The pastoralists are given this type of land for a specified period of time. Availability of special pasture with mean score of 2.37, market opportunity (M = 2.04), absence of tse-tse fly (M = 2.41) and support/backing from influential people with mean (M=2.11) were other reasons attracting pastoralists to the study area. Special pasture here means grasses and legumes that are highly nutritious to the animals and that can grow faster after being eaten by the animals. It involves digestibility, palatability and fastens reproduction of animals. This type of pasture draws the animals to the area often. Influential people in community also work with the pastoralists. These include traditional rulers who come in contact with the pastoralists, politicians, retired/serving civil servants, and military men-retired/serving who have established relationship with the pastoralists. Because they have the backing / support of those individuals, the pastoralists flock to the study.

Conflicts as a Challenge to Livestock Development and Animal Agriculture

Conflict is a major challenge to livestock development and animal agriculture not only in the study area, but the world over. Any situation that brings chaos is not healthy for humans and animals as all will be restless and disturbed. Table 4 revealed that during conflicts the grazing field for animals becomes unsafe as shown by a mean response of 3.30, poor animal health (M = 3.27), animal/herd abandonment (M = 3.38), loss of human lives (M = 3.33), loss of farm income (M = 3.37), cattle rustling/raiding (M = 3.32) and high cost of animal products (M = 3.25). The above situation presents a big challenge to animal agriculture as rearers of animals will put a stop to business and run for their dear lives thereby making the livestock suffer neglect and abandonment. Due to concern for human lives and property, the business of animal rearing will take second fiddle, after all, the living will do the things that are important because there is life. Again, during conflict, livestock markets are closed (M = 3.20) as both buyers and sellers will be in fear of going to the market to risk being attack. Market is an area where buying and selling and other economic transactions take place for the survival of man. When market for livestock is cease, the economic life of the people is touched. Demand for livestock is reduced (M = 3.27), total loss of pasture (M = 3.40) where animals feed is also a challenge to livestock development and animal agriculture. Conflicts reduces the facilitating functions of animals (M = 3.21). Rearers of animals sell them for meeting up with their financial obligation and family responsibilities. The money from cattle and other animals facilitates the performance of other necessary roles, function and obligation sponsoring social gathers and other traditional events.

For more JOURNAL OF FOOD AND NUTRITION : https://lupinepublishers.com/food-and-nutri-journal/

Please Click Here: https://lupinepublishers.com/food-and-nutri-journal/fulltext/pastoralists-perception-of-resource-use-conflicts-as-a-challenge-to-livestock-development-and-animal-agriculture-in-southeast-nigeria.ID.000126.php

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

Excerpt from this story from Ozy:

On Nov. 20, residents of Gya village in northern India’s Ladakh region woke up to a devastating loss — 16 yaks on one of their high-altitude pasture lands, nearly 16,000 feet above sea level, had been killed. They belonged to Phuntsog Tserinng Choksar, a yakzi (yak herder). “It could have been either a snow leopard or a pack of wolves that attacked the yaks,” says Karma Sonam, a local wildlife conservationist.

For the seminomadic pastoral communities that span Ladakh and the Tibetan Trans-Himalaya region in China, yaks are a source of livelihood and symbols of wealth. Yet these pastoralists share this rugged, mountainous terrain with snow leopards and Himalayan wolves that routinely target their livestock, setting up what for centuries has been a classic man-versus-animal conflict.

Now, a dramatic new approach pioneered by local conservationists and villagers is upending that seemingly irreconcilable tension, using Buddhist principles to turn enmity into peaceful coexistence. If successful, this strategy promises a surprising new route to wildlife protection using religion and spiritualism that other societies and nations could emulate.

For generations, people in the region have built conical stone traps known as shangdong for predators. A live bait, usually a sheep or a goat, is kept inside the structure to lure the wolf in. Once the wolf steps in, the upward-slanting walls prevent the wolf from getting out, thereby trapping it. The villagers then typically come together to stone the wolf to death.

But conservationists are now teaming up with Buddhist leaders and villagers to replace shangdongs with Buddhist stupas — religious pillars — that serve as reminders of the Buddhist principle of compassion toward all living creatures. At the same time, they’re building wildlife reserves for the wolves and snow leopards. Herders aren’t allowed to use these reserves as pasture lands.

The idea is to create boundaries within which the predators can feed on local prey like the bharal, goat-like creatures that are also known as blue sheep, while yak can roam in relative safety outside the reserves. Driving this shift are age-old Buddhist principles, now being used for 21st-century conservation.

“Bauddha dharma [Buddhism] tells us that one should not harm any living being, for in their previous birth, it could have been your father, mother or sibling,” explains Rangdol Nyima Rinpoche, one of the region’s most influential Buddhist leaders, in a phone interview with OZY. (Rinpoche is an honorific title used for highly respected teachers.)

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

Video by @amivitale. Orphaned baby elephants at Reteti Elephant Sanctuary (@r.e.s.c.u.e) in northern Kenya browse on Namunyak Wildlife Conservancy, where the sanctuary is located. Elephants are some of nature’s greatest eco-engineers. They feed on low brush and bulldoze small trees, promoting the growth of grasses, which attract bulk grazers, like buffalo, zebra, eland and oryx, as well as provide food for the livestock of pastoralists, like the Samburu people who live here. By caring for and protecting the elephants, the Samburu people are also helping care for the land they live on. @r.e.s.c.u.e is the first ever community-owned and run elephant sanctuary in Africa. This oasis where orphans grow up, learning to be wild so that one day they can rejoin their herds, is as much about the people as it is about elephants. ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ Learn more, including how to get involved, by following @r.e.s.c.u.e. ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ @conservationorg @kenyawildlifeservice @tusk_org @sandiegozoo @thephotosociety @photography.for.good #protectelephants #bekindtoelephants #DontLetThemDisappear #elephants #saveelephants #stoppoaching #kenya #northernkenya #magicalkenya #whyilovekenya #africa #everydayafrica #photojournalism #nikon #nikonlove #nikonambassador #nikonnofilter #natureisspeaking #conservation #amivitale #cuteanimals (at Reteti Elephant Sanctuary) https://www.instagram.com/p/CEnbVrjBjoY/?igshid=oqcg51wox06i

#protectelephants#bekindtoelephants#dontletthemdisappear#elephants#saveelephants#stoppoaching#kenya#northernkenya#magicalkenya#whyilovekenya#africa#everydayafrica#photojournalism#nikon#nikonlove#nikonambassador#nikonnofilter#natureisspeaking#conservation#amivitale#cuteanimals

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

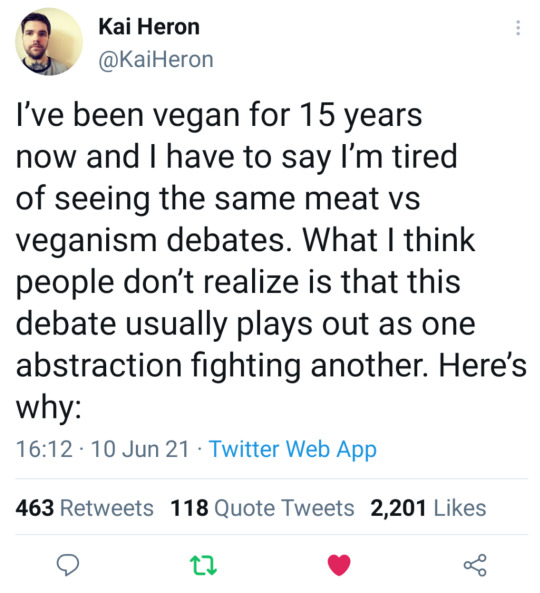

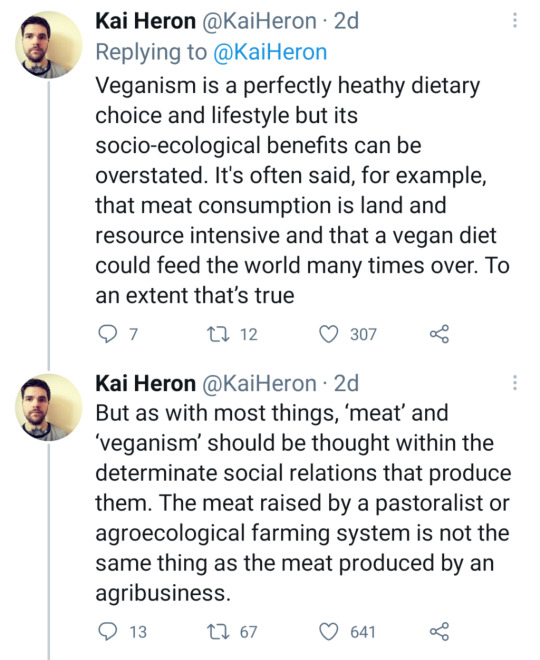

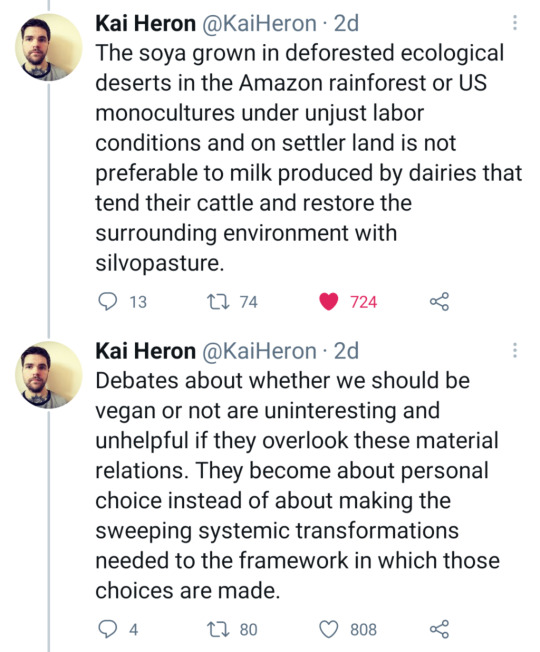

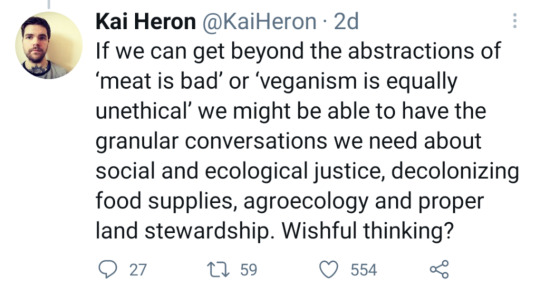

Text is a chain of 10 tweets by "Kai Heron" (@/KaiHeron) that read:

I've been vegan for 15 years now and I have to say I'm tired of seeing the same meat vs veganism debates. What I think people don't realize is that this debate usually plays out as one abstraction fighting another. Here's why:

Veganism is a perfectly heathy dietary choice and lifestyle but its socio-ecological benefits can be overstated. It's often said, for example, that meat consumption is land and resource intensive and that a vegan diet could feed the world many times over. To an extent that's true

But as with most things, 'meat' and 'veganism' should be thought within the determinate social relations that produce them. The meat raised by a pastoralist or agroecological farming system is not the same thing as the meat produced by an agribusiness.

The soya grown in deforested ecological deserts in the Amazon rainforest or US monocultures under unjust labor conditions and on settler land is not preferable to milk produced by dairies that tend their cattle and restore the surrounding environment with silvopasture.

Debates about whether we should be vegan or not are uninteresting and unhelpful if they overlook these material relations. They become about personal choice instead of about making the sweeping systemic transformations needed to the framework in which those choices are made.

So it's not about going vegan or not. It's about producing our food in as ecologically benign way as possible. Meat (sustainable sourced, and in dramatically reduced quantities for some) is likely to play a role in that for the foreseeable future.

When managed appropriately, livestock's inclusion in farming systems can restore soil health, boost biodiversity, and to a certain extent sequester carbon. This is a fascinating area of ongoing scientific research sciencedirect.com/science/articl... &

Global food systems are complex. Transitioning to an ecologically benign, let alone restorative, food system is even more so. It will take ingenuity, struggle, and a willingness to learn from pastoralists, peasants, scientists, and black and Indigenous land stewards alike.

And yes, it will require an end to capitalist production. It is capital–not meat or soya per se–that impels the wasteful, anti-ecological, carbon intensive overproduction of food and that drives producers towards grossly unjust and inefficient land uses. [x]

If we can get beyond the abstractions of 'meat is bad' or 'veganism is equally unethical' we might be able to have the granular conversations we need about social and ecological justice, decolonizing food supplies, agroecology, and proper land stewardship. Wishful thinking?

#twitter#tweet chain#contains links#I'm like 99% sure those are the right links#the second one didn't actually have the link in the text so I hope the x is fine

47K notes

·

View notes

Note

Any source for fao supporting animal agriculture?

Their 2013 report, “Tackling climate change through livestock” which is available in full form right here: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3437e.pdf

To people who haven’t been following this debate, the 2013 report is a follow-up on the much more widely known “Livestock’s long shadow” from 2006. Both reports are published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Highlights from the 2013 report include:

“With emissions estimated at 7.1 gigatonnes CO2-eq per annum, representing 14.5 percent of human-induced GHG emissions, the livestock sector plays an important role in climate change.” (14.5%, while still significant, is way lower than any estimate ARAs tend to quote)

“A 30 percent reduction of GHG emissions would be possible, for example, if producers in a given system, region and climate adopted the technologies and practice currently used by the 10 percent of producers with the lowest emission intensity.” (meaning the livestock sector would only account for a 10-11% of our global GHG emissions, from this change alone, never mind the numerous other technologies in development)

“Grassland carbon sequestration could significantly offset emissions, with global estimates of about 0.6 gigatonnes CO2-eq per year.” (meaning this, if implemented with the aforementionen practice changes, would bring livestock down to roughly 9-10% of our global emissions).

“Cutting across categories, the consumption of fossil fuels along the sector supply chains accounts for about 20% of emissions.” (meaning when the switch to reneweable energy inevitably happens, the sector can be reduced with - optimistically - close to 20%, which would bring it down to under 7% of our global emissions)

“Substantial emission reductions can be achieved across all species, systems and regions.” (so this isn’t just about cows - we’re talking pigs, poultry, buffalo, goats, sheep, you name it. The report doesn’t include aquatic animals, furbearers, or invertebrates, but I see no reason why their emissions can’t be reduced as well - fish and inverts are already ridiculously low)

“Hundreds of millions of pastoralists and smallholders depend on livestock for their daily survival and extra income and food.”

“The potential to reduce the sector’s emissions is large. Technologies and practices that help reduce emissions exist but are not widely used.The adoption and use of best practices and technologies by the bulk of the world’s producers can result in significant reductions in emissions.”

“The mitigation potential can be achieved within existing systems; this means that the potential can be achieved thanks to improving practices rather than changing production systems (i.e. shifting from grazing to mixed or frombackyard to industrial.”

“A reduction of emissions can be achieved in all climates, regions and production systems.”

“Most of the technologies and practices that mitigate emissions also improve productivity and can contribute to food security and poverty alleviation as the planet needs to feed a growing population.“

“Packages of mitigation techniques can bringlarge environmental benefits as illustrated infive case studies conducted to explore mitigation in practice. The mitigation potential ofeach of the selected species, systems and regions ranges from 14 to 41 percent.”

“The livestock sector should be part of any solution to climate change: its GHG emissions aresubstantial but can readily be reduced by mitigation interventions that serve both development and environmental objectives. “

________________________

Now, it’s worth mentioning that the report doesn’t treat animal agriculture like it’s all fine and dandy. There are problems with the sector - the fact that it still accounts for more than 10% of our global GHG emissions is evidence enough of that! What we need to do to fix the sector is not to boycott it, but to support innovation within it.

Another thing I’d like to point out: When reading this report, it’s very easy to get swept up in all the good we can do by making animal ag (and agriculture in general) more efficient, but it’s important to keep in mind that, at present, we are producing more food than we can eat, and a lot of our problems are due to inefficient distribution, rather than inefficient farming. We need to make farming more efficient to reduce the waste of the sector (remember, any waste is a financial and energy loss, including GHG emissions), not to produce more food.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lupine Publishers | Pastoralists’ Perception of Resource-Use Conflicts as a Challenge to Livestock Development and Animal Agriculture in Southeast, Nigeria

Lupine Publishers | Scholarly Journal of Food and Nutrition

Abstract

One of the major but hidden challenges to livestock development and animal agriculture the world over is resource-use conflicts between crop farmers, pastoralists and other land users. This is so because during conflict situation, almost all human livelihood activities come to a standstill including livestock farming. This study therefore sought to examine how conflicts involving different land users hinder livestock production. Questionnaire and oral interview were used to obtain information from a total of 120 pastoralists in three selected states of Southeast (Abia, Enugu and Imo). Data were analyzed using percentages, mean and standard deviation. The results showed that the mean age of pastoralists was 38, and the mean household size was 10, mean herding experience was 18. The following were the causes of resource-use conflicts - blocking of water sources by crop farmers with a mean (M) response of 3.30, farming across cattle routes (M = 2.95), burning of fields (M = 3.30), theft/stealing of cattle (M = 3.40), among others. The factors attracting the pastoralists to the study area were availability of special pasture (M=2.37), availability of land for lease (M=2.52), water availability (M=2.60) among other reasons. Conflicts, therefore, affect livestock production in the following ways - unsafe field for grazing, poor animal health, loss of human and animal lives, abandonment of herds for dear life and many others.

Keywords: Animal; Agriculture; Conflict; Livestock; Pastoralists

Introduction

In Nigeria, grazing lands are rarely demarcated, and this large sector of agriculture always suffers compared to crop farming or fruit plantation [1]. The latter two are mostly demarcated favorably for the fact that most people are sedentary, and areas needed are small. The establishment of demarcated rangelands and passageways (cattle corridors) allow the livestock to access water points and pastures without causing damage to cropland [2]. Pastoralists usually graze over areas outside farm lands, and these have been accepted to be the norm from time immemorial. Their movements are opportunistic and follow pasture and water resources in a pattern that varies seasonally or year-to-year according to availability of resources [2].

Livestock production in the form of pastoral livestock keeping is among the most suitable means of land use in arid areas of Africa because of its adaptability to highly variable environmental conditions. In Nigeria, most pastoralists do not own land but graze their livestock in host communities [3]. While a few have adopted the more sedentary type of animal husbandry, the increasing crises between farmers and pastoralist presupposes that grazing is a major means of animal rearing in Nigeria. The livestock sector in Nigeria is plagued by several challenges such as lack of adequate supplies of quality feed and pasture, diseases, weak market network, unavailability of adequate water and poor veterinary services [4- 7], reiterate that the sector is constrained by institutions, markets and policy as well as technical issues. More recently concern on herdsmen-farmers’ conflicts has appeared in literature and policy discourse as one of the formidable challenges facing livestock production (particularly ruminant) in many developing countries. Resource-use conflicts in Nigeria have persisted and stands out as a threat to national food security, livestock production and eradication of poverty with pastoralists often regarded as the most vulnerable. Resource-use conflicts not only have a direct impact on the lives and livelihoods of those involved, they also disrupt and threaten the sustainability of agriculture and pastoral production in West Africa [8]. So many land users make their livelihood within the same geographical, political, and socio-cultural conditions, which may be characterized by resource scarcity [9] or political inequality and population pressure. Pastoralists are believed to be more vulnerable compared with farmers because their cattle can be confiscated and/or seized and released only on payment of a fine. Besides, sometimes they are in the minority and could lack political power to their advantage [10].

Resource use conflicts/clashes according to Adisa and Adekunle [11], are becoming fiercer and increasingly widespread in Nigeria. A study of 27 communities in central Nigeria by Nyong and Fiki [12] shows that over 40% of households surveyed had experienced agricultural land-related conflicts, with respondents recalling conflicts that were as far back as 1965 and 2005. Okoli and Atelhe [13], showed that about 13 cases of farmer- herdsmen conflicts across states of the federation which claimed 300 lives of the citizens. In Abia, Enugu and Imo States, there have been cases of conflicts between pastoralists and crop farmers in Umunneochi, Ugwunagbo Uzo-uwani, Nkanu-West,Udi, Ohaji/Egbema, Owerri West, and Okigwe areas of the States over crop destruction by cattle, killing of herders and stabbing of farmers following reprisal attack on different occasions [14]. Therefore, the study examined challenges of resource-use conflicts to livestock production in the Southeast region of Nigeria. It specifically sought to: describe the socioeconomic attributes of respondents; b. examines causes of conflicts as perceived by the pastoralists; c. identifies factors that attract the pastoralists to the state; and, d. ascertain challenges of resource-use conflicts to livestock agriculture.

Methodology

This study was conducted in Southeast agro-ecological zone of Nigeria. The zone lies within latitudes 5oN to 6oN of the equator and longitudes 6oE and 8o E of the Greenwich meridian. Southeast Nigeria is made up of five (5) states-Abia, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu and Imo. The zone occupies a total land mass of about 10, 952, 400 hectares with a population figure of about 33,381,729 persons in 2018 projected from 2006 National Population Commission Census figure [15]. About 60-70% of the inhabitants of the zone are observed to engage in agriculture, mainly crop farming and animal rearing [16]. The 2-stage sampling technique was adopted in the process of sample selection. The first stage was the purposive selection of three states from the Southeast agroecological zone where cases of farmer-pastoralists conflicts have occurred and were reported (Abia, Enugu and Imo). The second stage involved the random selection of 120 pastoralists from the list of 180 pastoralists from their various camps in the three states. Both primary and secondary data sources were used. Simple descriptive statistics such as mean, percentage, frequency distribution was used to analyze the socio-economic characteristic of the respondent. Objective 1 was analyzed using percentage presented in table. Mean was computed on a 4-point Likert type rating scale of strongly agree, agree, disagree and strongly disagree assigned weight of 4,3,2,1 to capture the perceived causes of the conflicts (objective 2) and challenges of conflicts to livestock development (objective 4). The values were added and divided by 4 to get the discriminating mean value of 2.5. Any mean value equal to or above 2.5 was regarded as a major factor causing conflict and challenge to livestock development, while values less than 2.5 were regarded none. Again, mean was also computed for objective 3 which looked at factors attracting pastoralists to the area on a 3point Likert type rating scale of very serious, serious and not serious assigned values of 3,2,1. The values were added and divided by 3 to obtain a discriminating mean value of 2.0. Any value with mean equal to or greater than 2.0 was considered very serious and vice versa (Figure 1).

Results and Discussion

Socioeconomic Characteristics of Respondents

Table 1 showed that 83.3 percent of the pastoralists were married, while 16.6% were single. The predominance of married people among the pastoralists could be attributed to the complementarity experienced in farm labour provision at the household level. The man, woman and children pool their physical reserves to keep the arm on course. It is worthy to note that there are potential soldiers at the event of land use conflict. Whereas 85.8% of the pastoralists had quranic education, 10 percent had primary education, then, only 4.2% had no formal education. The pastoralists, all (100%) belonged to social organizations; Islamic unions and or herder unions. These respondents who belonged to social organization will likely benefit and share knowledge and experiences through contacts and cross-fertilization of ideas. The organization could also provide forum to plot, plan and execute attack.

The table reveals that 47.5 percent of the pastoralists indicated that the animals are not their own but that of military officers, retired and serving. Some of the animals are also owned by alhajis and traditional rulers in the north (29.2%) who have established contacts with their kits and kins to protect their interest where ever they may be. Also, 20.8 percent and 2.5 percent respectively are owned by the pastoralists themselves and few politicians who also trade in animals. The result explains the effrontery of the pastoralists and their seeming more powerful than the natives who are always helpless at their audacity. The mean age range was 38 years. This implies that the pastoralists are also young and can endure the difficult nature of their practice of trekking very long-distance day and night. The average herding experience was 18 years. Experience is a valuable asset. The years of experience of the pastoralists could enable them to relate encounters they had; causes, effects and resolution. The mean herd size was 61. This is indeed large, and it reveals the fears of the crop farmers should cattle numbering into 30-100 invade their farms. A great deal of damage would be done, livelihood activities may be lost, food insecurity enthroned in addition to accentuated poverty. The average monthly income was N53,500.00. The pastoralists in their course sell the cattle and they also reproduce under their care.

Perceived Causes of Resource-Use Conflicts in the Study Area

Table 2 showed the pastoralists perception of the causes of the conflicts involving them and the crop farmers. Although they may seem to blame crop farmers or shy away from reality of telling the truth. To them the causes of the conflicts included blocking of water source by crop farmers (M= 3.30), farming across cattle routes (M = 2.95), limited grazing areas (M = 2.70), burning of rangeland/field by crop farmers (M = 3.28). They claim that farmers block the wells, ponds and river routes where their animals drink. They also assert that farmers set their grazing areas ablaze and farm across their animal routes thereby hindering their movement. Other causes of conflict were claim of land ownership (M = 2.64) by the farmers; farmers fight herdsmen (M = 3.00), setting of traps along the cattle way (M = 2.74), harassment of pastoralists (M = 3.01) by the youths, stealing/theft of cattle (M = 3.40), and poisoning of water source (M = 2.80). The pastoralists see land as a free gift of nature and as such nobody should prevent others from the use of it and make laws regarding it against others. To them, land is for all and should be used as desired.

Factors Attracting Pastoralists to the Study Area

Table 3 showed that several factors attracted the Fulani pastoralists to the state. Among the factors were water availability with a mean (M) response of 2.60 and availability of land to lease with mean score of 2.52. Water is life of both man and animals and the availability of streams and rivers in the Southern part of Nigeria becomes a reason for the pastoralists’ invasion of Imo state. Again, even during the dry season, water sources remain intact as families get water either from streams, rivers and even ponds. Land for lease or rent (M=2.52) to the head of the pastoralists is also available. These lands are mostly abandoned land not good enough for immediate crop production. The pastoralists are given this type of land for a specified period of time. Availability of special pasture with mean score of 2.37, market opportunity (M = 2.04), absence of tse-tse fly (M = 2.41) and support/backing from influential people with mean (M=2.11) were other reasons attracting pastoralists to the study area. Special pasture here means grasses and legumes that are highly nutritious to the animals and that can grow faster after being eaten by the animals. It involves digestibility, palatability and fastens reproduction of animals. This type of pasture draws the animals to the area often. Influential people in community also work with the pastoralists. These include traditional rulers who come in contact with the pastoralists, politicians, retired/serving civil servants, and military men-retired/serving who have established relationship with the pastoralists. Because they have the backing / support of those individuals, the pastoralists flock to the study.

Conflicts as a Challenge to Livestock Development and Animal Agriculture

Conflict is a major challenge to livestock development and animal agriculture not only in the study area, but the world over. Any situation that brings chaos is not healthy for humans and animals as all will be restless and disturbed. Table 4 revealed that during conflicts the grazing field for animals becomes unsafe as shown by a mean response of 3.30, poor animal health (M = 3.27), animal/herd abandonment (M = 3.38), loss of human lives (M = 3.33), loss of farm income (M = 3.37), cattle rustling/raiding (M = 3.32) and high cost of animal products (M = 3.25). The above situation presents a big challenge to animal agriculture as rearers of animals will put a stop to business and run for their dear lives thereby making the livestock suffer neglect and abandonment. Due to concern for human lives and property, the business of animal rearing will take second fiddle, after all, the living will do the things that are important because there is life. Again, during conflict, livestock markets are closed (M = 3.20) as both buyers and sellers will be in fear of going to the market to risk being attack. Market is an area where buying and selling and other economic transactions take place for the survival of man. When market for livestock is cease, the economic life of the people is touched. Demand for livestock is reduced (M = 3.27), total loss of pasture (M = 3.40) where animals feed is also a challenge to livestock development and animal agriculture. Conflicts reduces the facilitating functions of animals (M = 3.21). Rearers of animals sell them for meeting up with their financial obligation and family responsibilities. The money from cattle and other animals facilitates the performance of other necessary roles, function and obligation sponsoring social gathers and other traditional events.

Conflict changes the structure of livestock market which disproportionately affects the livelihoods of livestock producers and livestock traders as well as consumers’ access to livestock products. Other major factors are: insecurity of trade routes; market closures or destruction; lack of demand; the departure of traders from some conflict-affected counties FAO [17], forced migration of millions of heads of livestock. In some cases, herders’ choices of migration routes were influenced by the need to protecting their livestock rather than feed and water availability.

Conclusion

Conflicts between pastoralists and crop farmers in agrarian communities present a formidable challenge to livestock production in Nigeria. This is due to the problems of incompatibility of livelihood strategies, competition for access and use of natural resources such as land and water. Pastoralists - crop farmers’ conflict has production and economic consequences for herding. Among the most direct effects are loss of human lives, reduced number of livestock as well as reduced access to water, pasture and even loss of homes. In addition, the conflicts lead to distrust in other communities and a strong omnipresent perception of insecurity which entails several and partly interconnected subsequent effects. These effects include ineffective resource use, reduced mobility, closing of markets and schools and obstacles for investments. There is a need for effective conflict mitigation that breaks the cycle of violence, retaliation and impoverishment. There is need to move from the conflicting to a cooperative path, which could start by addressing the capability of the actors

https://lupinepublishers.com/food-and-nutri-journal/fulltext/pastoralists-perception-of-resource-use-conflicts-as-a-challenge-to-livestock-development-and-animal-agriculture-in-southeast-nigeria.ID.000126.php

For more Lupine Publishers Open Access Journals Please visit our website: https://twitter.com/lupine_online

For more Food And Nutrition Please Click

Here: https://lupinepublishers.com/food-and-nutri-journal/

To Know more Open Access Publishers Click on Lupine Publishers

Follow on Linkedin : https://www.linkedin.com/company/lupinepublishers Follow on Twitter : https://twitter.com/lupine_online

0 notes

Text

How Maasai Pastoralists Are Securing Their Livelihoods Through Self-Sufficient Fodder Production

“Discover how Maasai Pastoralists in Kajiado County are transforming their livelihoods through innovative forage production and climate resilience strategies.” “Learn how Maasai Pastoralists are overcoming drought challenges by growing their own animal feed, supported by FAO and the Mastercard Foundation.” “Explore the success story of Maasai Pastoralists who are leading the way in sustainable…

#climate change adaptation#Climate resilience#community resilience.#drought adaptation#FAO project#fodder production#forage production#Indigenous youth#Kajiado County#Livestock feed#livestock security#Maasai innovation#Maasai Pastoralists#pasture management#sustainable livestock farming

0 notes

Text

Juniper Publishers- Open Access Journal of Environmental Sciences & Natural Resources

Value Chain Analysis of Frankincense in Hammer and Benna-Tsemay Districts of the South Omo Zone, South Western Ethiopia

Authored by Asmera Adicha

Abstract

A study was conducted in Hamer and Benna-Tsemay districts of the South Omo zone of Ethiopia, with the objectives of identifying and mapping the market chain and its functions, providing the picture of supply and use patterns, identifying and suggesting possible intervention of value additive techniques, identifying potential opportunities and constraints in the production, processing and marketing of Frankincense. Two- stage sampling strategy used to select Frankincense collectors for the study the producers/collectors and traders within society as well nearby marketing systems were studied through group discussion, personal observation, and using a structured questionnaire where each household was taken as a unit of analysis (45 households from Hammer, 15 from Benna-Tsemay). Simple descriptive statistical tools were used for the analysis. Observation among value chain were summarized using Strength, Weakness, Opportunity and Treat (SWOT) analysis and software called Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) were also used for the analysis. Survey results show that almost all of the respondents confirmed that the incense products potentially collected from the natural forest found far away from their villages. Currently the marketing of Frankincense both at Hammer and Benatsemay Woreda of south Omo zone in general is not well developed and there is no established market in place. To advance the value chain the of Frankincense and sustainably contribute to the income of pastoral communities formation of collector groups, associations or cooperatives is needed to foster cooperation and coordination of the collection and marketing of Frankincense.

Keywords: Frankincense; Marketing; Value Added; Value Chain

Abbreviations: SWOT: Strength Weakness Opportunity Treat; SPSS: software called Statistical Package for Social Science; NTFP: Non-Timber Forest Products; PNRM: Participatory Natural Resource Mapping

Introduction

In rural Ethiopia, a majority ofthe households make use of nontimber forest products (NTFPs) for different purposes, ranging from food, feed, energy, and medicine to income generation and cultural practices [1,2]. As provided by among the range of NTFPs, gums and resins are important trade commodities with a potential for spurring economic and social developments both at rural and urban areas in Ethiopia [3-5]. Commercial gums and resins are produced in rural (remote) areas, traded in urban centers, and consumed by western countries and, hence, touch wide ranges of human lives and cross-sections [6-8]. However, recent studies revealed poor linkage of rural producers to the market niches and, hence, lack of proper producers' marketing system [5]. Sound development of the value chain of Frankincense will, thus, have a massive impact on the larger population, especially the vulnerable rural poor dependent upon natural resources in the country [9,10]. Moreover, in the south Omo zone, value chain of the Frankincense starting from inception to consumption among major actors (producers//collectors, processors, traders, middlemen, and commission agents and consumers) are not yet studied and documented. Thus, the value chain analysis of Frankincense is carried out with the following objectives:

a) To identify and map the market chain of Frankincense and its functions

b) To provide the picture of supply and use patterns of Frankincense

c) To identify and suggest possible intervention of value additive techniques of Frankincense

d) To identify potential opportunities and constraints in the production, processing and marketing of Frankincense

Methods

Description of the study area

The study was conducted in Hamer and Benna-Tsemay districts of south omo zone found in the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People's Regional State of Ethiopia. The two districts have a total land area of 9,496 km2 (Hamer = 5,742 km2 and Benna-Tsemay = 3,754 Km2). The districts are located 4° 27'-5° 39' north and 35° 23'- 37° 49' east, bordering Kenya to south; Bako gazer district to the north; Borana zone and Konso district to the east, and Kuraze and Selamago districts to the west. The study districts, Benna-Tsemay (Key Afer) and Hamer (Dimeka), are located at about 739 and 839 km from the capital city Addis Ababa, respectively. Furthermore, Key Afer and Dimeka are located 402 and 602 km from Hawassa, respectively [11]. The study area is characterized by semi arid and arid climatic conditions, with mean annual rainfall increasing from the extreme south lower part, with some 350 mm, to the upper part where it ranges to 838 mm. The rainfall is bimodal, with the long rain season from March to June and the small rain. Forest composition of districts are a mixture of Acacia, Boswellia and Commiphora woody species and short grasses type with varying density of woody vegetation (woreda classification). The arid and semiarid zones are the preferred sites for Boswellia and Commiphora species (in altitude less than 1250 m.a.s.l). Acacia nilotica is the dominant woody plant in altitude ranging from 1,250 m.a.s.l to 1,600 m.a.s.l. Agro-mountain broad leaf wood plants with floristic elements of the Ethiopia highland is the typical vegetation in altitude abovel, 600 m.a.s.l. [11]. The pastoralists in the study districts raise cattle, goats, sheep and chicken as well they harvest honey from traditional hives and wild honey from the inside holes of trees and between rocks.

Data source and sampling techniques

This study used primary and secondary data sources. The secondary sources included Agriculture and rural development offices and development agents. primary data collected through focus group discussions with development agents, elders' women, young's, men and kebele administrative: key informant interviews with key person in the area: field observations and over viewing marketing system (Figure 1).

Field observations: They collect the exudates (ooze) from a standing tree by climbing on it to nearest branches by their own bare hands and sometimes they use sharp local materials such as knife and stone. Children and elders are the main collectors while chasing after group of goats and cattle who has been responsible for brought into the natural pasture and permanent water sources (Figure 2).

Passengers purchase at the road side: Two-stage sampling strategy used to select Frankincense collectors for the study: Stage 1: purposive sampling to select the districts and kebeles. Stage 2: random sampling to select individual households for survey. Three pastoralist kebeles from Hammer district (Marsha kelema, bita gelefa and gembela) and two pastoralist kebeles from Benatsemay district (luka and ufo) were selected. And a structured and pretested questionnaire was administered to sixty(60) households in the Hammer and Benatsemay Woreda. The questionnaire was designed in such a way that it enables to collect data on the demographic and socio-economic characteristics of households, potential opportunities and constraints in production ,production and use pattern , picture of supply ,market chain and marketing of incense in the study area.

Data analysis

Simple descriptive statistical tools were used for the analysis. Observation among value chain were summarized using Strength, Weakness, Opportunity and Treat (SWOT) analysis and software called Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) were also used the analysis.

Results and Discussion

This chapter deals with the analysis of the survey data and interpretation of the analytic finding.

Demographic and Socio-economic Characteristics

A majority of the respondent households are between 20 and 55 years old and male-headed (Table 1). In rural Ethiopia, due to cultural influence, it is common to find few female-headed households. Illiteracy is prevalent and only 20% of the respondent households completed primary school. In contrast to government reports that indicate significant improvement in educational access for children and youth, none of the family heads below 20 years of age had completed even primary school [12]. Almost 50% of the family sizes of the respondents are above 5. This shows that family planning in the area is poor. The major occupation the respondents in the area is livestock and crop production, Frankincense collection, honey/bee farming.

Production and use pattern of Frankincense

Survey results show that almost all of the respondents confirmed that the incense products potentially collected from the natural forest found far away from their villages. As revealed by Woreda agricultural development office and development agents the annual production potential of Frankincense from natural forest at both Hammer and Benatsemay district were on average 500-600kg/year and 720-840kg/year respectively Most of the studied households are engaging in Frankincense activities, i.e. either in tapping/collection, marketing, or both activities to generate cash income. Income generated from sale of Frankincense helps in meeting household needs, purchasing food and supporting livestock keeping activities. Annual income from Frankincense sales in the agro pastoralist kebeles of Luka, Ufo, Marsha Kelema, Bita Gelefa and Gembela mostly ranged from 3,000 to 9,000 birr (Table 2). The average cash income from Frankincense sales among the 60 surveyed households was about 5312.7 birr/ year during the survey period. Total annual income from Frankincense sales for all surveyed households is: 5312.7 birr* 60 households = 318,762 birr.

Source: own survey (2005/6 E.C)

Market chain of Frankincense

Currently the marketing in Frankincense both Hammer and Benatsemay Woreda of south Omo zone in general is not well developed and there is no established market in place. Buying and selling is done at many levels ranging from the collection point up to marketing centres in small towns (Turmi-for Hammers; Luka, Woito and keyafer for Benatsemays). As respondents stated that still now they do not have permanent customers to sell the incense. But mostly passengers and town dwellers purchase from small town marketing centre and at the road side. Also they revealed that it takes a long time to market Frankincense and collectors lack sound market information to guide them on opportunities, trends and price mechanisms. The price of the Frankincense increases as the commodity heads to the end of the value chain. The number of traders buying Frankincense are few, mostly based in marketing centers that buy at collection points or small centers and in return sell to them. However, there is an emerging trend where traders are going around and buying incense directly from collectors.

As it is well understood from the group discussion respondents confirmed that during different occasion of time the incense production and marketing cooperatives have been formulated with ultimate support and initiatives of two different NGO's (Farm Africa-Hammer and Benatsemay, and AFD-Hammer). Moreover, different trainings concerning tapping and handling of incense products have been organized by pastoral and agro-pastoral development office of the two discrete wore das. However, none of the cooperatives have been functional due to lack of continuous follow up and support. Collectors are paid 12-14birr per kg for black and 40-50birr per kg white incense by both middlemen and local traders. Middlemen and local traders mostly sell at 16-20birr per kg black and 50-60birr per kg white incense to town dwellers and passengers. However there is no trader who transports the Frankincense to exporters. According to collectors, in recent years the price of Frankincense has improved (Tables 3 & 4).

Source: Survey data (2005/2006).

From the above table in the years (2001-2003) it was so cheap. But recently, its value increased. As quantity increase, the prices also increase in consecutive years (2004-2006) of production and this shows that trends in production increase due to increase in price. There are a number of reasons that trigger the demand and price of incense products. According to respondents, the most reason is the season of production. Dry season is the potential period of incense production and consequently high production of incense has been collected by the community. However, during this period the price of incense has been dropped due to equilibrium of the market and the reverse is true for rainy season (Figure 3). Hence, the major steps in the collection and marketing value chain of Frankincense can be tapping (collection) -- Processing -- local market/passengers. As the collected Frankincense move through this chain in both districts of the study area.

Value adding system