#fechtbuch

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

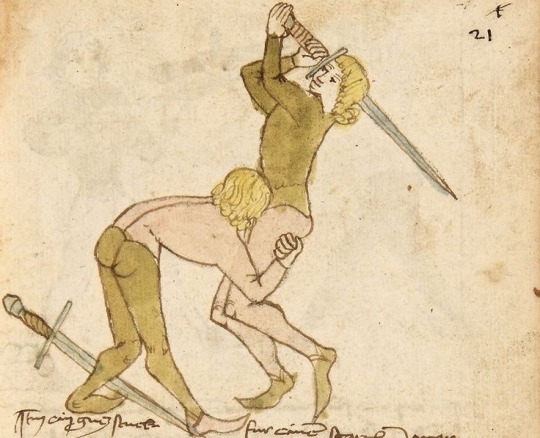

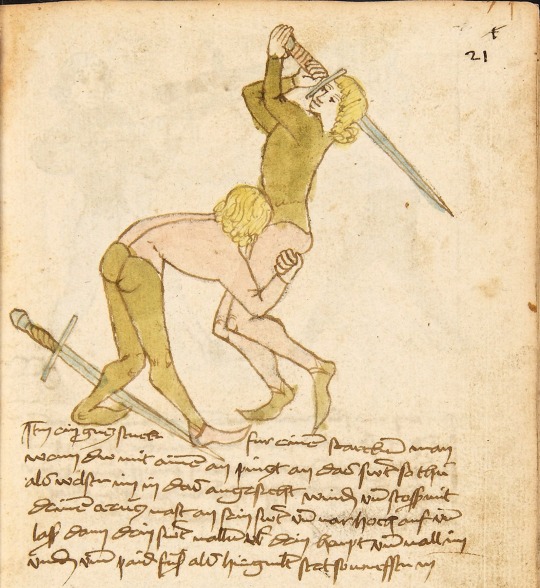

judicial duel between a man and a woman

manuscript illustrations from hans talhoffer's fencing manual alte armatur und ringkunst. bavaria, c. 1459

source: Copenhagen, Det Kgl. Bibliotek, Ms Thott 290.2º, fol. 80r-84r

#15th century#fechtbuch#fechtbücher#fencing manuals#hans talhoffer#alte armatur und ringkunst#duels#judicial duels

686 notes

·

View notes

Text

#fashion#medieval fashion#medieval clothing#medieval studies#fechtbuch#hosen#renaissance fashion#pants

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

As part of my Neuvillette-adjacent reading, I learned about Hans Talhoffer's combat manual of 1467. It depicts the numerous methods and types of judicial duel and...uh yeah. Not for the faint-hearted.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

I drew more mecha art! I like combining modern and archaic elements in these, like heads that resemble knight helmet designs and just the general sword & shield thing

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

More: https://thetravelbible.com/top-artifacts-from-the-medieval-period/

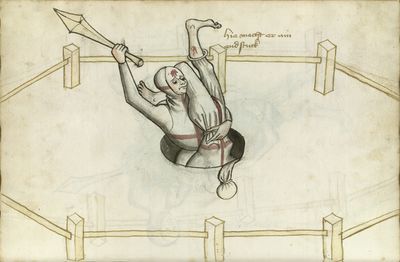

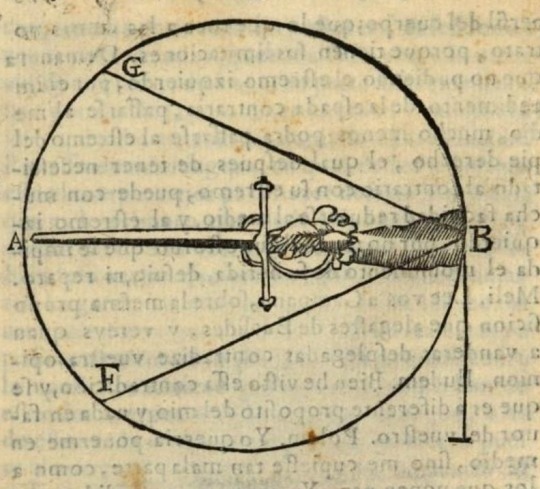

An Illustration of a longsword technique from the Codex Wallerstein, a 16th-century convolution of three 15th-century fechtbuch (combat manual) manuscripts, with a total of 221 pages. The codex is now housed at the Augsburg University library in Germany

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

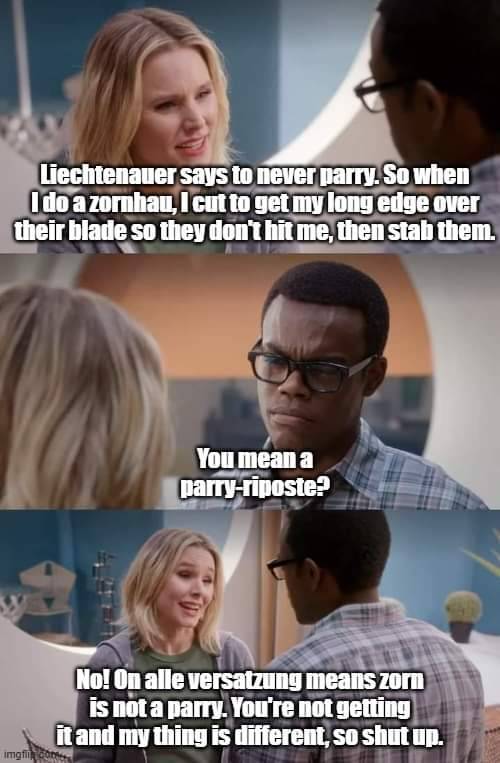

For the yet-to-be-informed, let me preach to you the gospel of Das gayszlen

What is Das Gayszlen?

Das gayszlen, generally translated as the "whip" is a technique in historical longsword fighting from 15th century German tradition. The basic mechanics of the gayszlen are as such: a single handed strike with the nondominant or lower hand, where the sword is released from a traditional grip to allow the blade to sweep towards the leg of your opponent. Some also define other one handed strikes, slices, or thrusts as a gayszlen, but (in my experience) the more common interpretation is the narrower definition I provided. There is some difficulty however in knowing definitively how it was used historically, beyond the general difficulty in knowing anything for certain in HEMA that comes with the territory of reviving a dead art. Much proverbial ink has been spilled online about how, when, and if it is appropriate to use, and many consider it to be a cheap trick, not to be used in serious competition or incorporated into a revival of historical fencing systems. I have Thoughts™ about it and my new URL change inspired me to detail those thoughts, continued below.

Where does it come from?

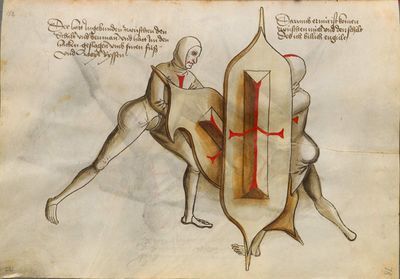

Ok. so. maybe "15th century german tradition" is a bit generous. There is a grand total of ONE source for the gayszlen, which is in a fechtbuch (fencing book) by fencing master and author Hans Talhoffer, one of the most influential and prolific of his time. His numerous manuals cover a wide range of weapons and techniques including grappling, dagger, polearms, mounted and armoured combat, as well as some more silly things like duelling/long shields and "man vs woman" duels (last two pictured below).

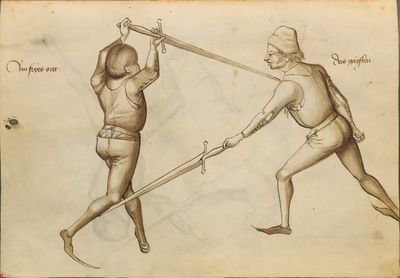

Despite all that and multiple depictions of many of the techniques for these silly "niche" styles of combat (at least in the context of modern HEMA practice, they likely were somewhat prevalent at the time and used to resolve legal disputes) there is only one illustration of the gayszlen, in one of Talhoffer's books. It depicts an exchange between a fencer in a "free point" (afaik the only time that term is used as well, though it is a position that is quite common in german longsword fencing, being a sort of hanging guard or the midpoint of a strike like a zwerchhau) and another performing the gayszlen against the aforementioned fencer, shown below (figure on the right is performing the gayszlen).

You may notice the text on the image, next to each figure! These say Ain fryes ortt and Das gayszlen, again translated as "a free point" and "the gayszlen". You may ask "but what does the actual caption or description say about it?!" I'm so sorry to disappoint you, and I share in your misery: this is all there is. Truly sad, I know. This lack of source material is (in my opinion) why there is so much difficulty defining it and so much debate over its historical usage and value in modern use.

So how do people interpret it?

As stated earlier, the (general) consensus is that it is a one handed strike (a hit, hew, or cut, as opposed to a thrust or draw/push slice) made with the offhand to the lower half of the opponent's body. One of the main disagreements on how to interpret this is whether the sword is "whipping" or cutting to the left from the right, or from the right to the left. Based on the foot position, it might look like the fencer performing the gayszlen (hereafter referred to as G) is bringing the sword from their left side to swing into the opponent's (hereafter referred to as F) left calf. However, this hand position and movement of the sword leaves G entirely open to attack anywhere on their torso or the right side of their body generally. An example of me (right) executing this interpretation is below: you can see that I do actually get the hit, but my opponent nearly hits me with the first strike to the right side of my head, where I am most vulnerable, and follows it up with another strike to my head. If this scenario played out with sharp swords and no protective gear I would lose this fight.

Another interpretation of the gayszlen is this: G holds the sword in any guard on the right side of their body (higher guards may be better for generating more force or deciding to do literally anything other than the gayszlen) and releases the sword from their right hand, holding the pommel in the left and sweeping the sword towards F's right calf. in the picture we have, it may be that the "free point" is meant to be a response to the gayszlen, and therefore F is retracting their foot to avoid the gayszlen, while striking G to their unprotected body. An example of me (left) attempting to execute this interpretation is below: even though my opponent fails to parry or suppress my attack, it wasn't necessary. I didn't have the reach to hit her leg, though her dodge may have saved her even if I had been a bit closer to begin or had extended farther.

Something that I believe supports this second interpretation is the general attitude of historical German longsword manuals to favor attacks and guards from above, to high openings, or generally closer to the upper half of the body than lower attacks and guards. A reason for this is detailed in many European sword systems, namely the destreza rapier tradition, thibault by extension, and meyer.

https://www.youtube.com/shorts/tPHbG28niyc

The above image and video are pretty simple explanations, the core idea being that a sword and arm extended at the height of the shoulder (or nearer the shoulder) will have more forward reach than a sword and arm extended higher or lower than the shoulder. Because of this, F theoretically has somewhat of a reach advantage over G, as their sword and arm are closer to their shoulder. though the utility (as I'll talk about more later) of the gayszlen is that it is done in a grip that extends G's reach beyond a normal grip like F has.

There are also interpretations that point to it being a thrust (like I attempt below) which is supported by similar techniques showing up in other European sword systems, which I could spend a whole equally long post talking about, but this is plenty long as is, maybe a topic for another time. The two lame reasons I have for not liking this interpretation is that a thrust doesn't seem very "whiplike", and also a thrust to the legs with one hand is harder to pull off than a cut to the legs or a one handed thrust to the torso.

How can I incorporate the gayszlen into my modern HEMA practice?

To preface this, throughout all of this I'm mixing terms and concepts from Fiore and Liectenauer and Talhoffer and Meyer and probably some other stuff. I primarily study and practice Liechtenauer blossfechten via Ringeck, Danzig, and Lew, as well as most of Fiore's system. This is just my opinion on what purpose the gayszlen can serve in the frog DNA filled world of HEMA longsword, this is not pure to any martial art system, just an application for the sport.

That being said: I believe the gayszlen's place in modern longsword fencing is similar to that of guards like the boar's tooth, long tail, or the key, all of which can use distance deceptively. they place the sword further back than it would be in an iron gate or a plow (guards which are somewhat close to those I mentioned) and allow the fencer using them to seem less threatening than they would with more aggressive guards. Likewise, I often find myself throwing gayszlens from positions where I'm somewhat retracted or seemingly out of distance, or preparing for an attack to another opening. This can often allow an attack at an unexpected timing or from an unexpected angle. I find it works well when your opponent is static in a guard and you to a distance juuust outside of where you could hit them with a normal grip, and the switch to a one handed pommel grip gives you the couple inches you need to get the hit, and hopefully enough speed to avoid getting beaten away by their sword. One of the big dangers with the gayszlen is the opportunity it presents for getting hit. When you employ this technique, you give up basically all protection your sword has to offer, you can't block any incoming attacks, and you don't have a good enough grip to bat your opponent's sword out of the way. This means that if you don't plan well, you leave yourself totally open to a double or a hit to you if they avoid your gayszlen. See below! The fencer attempting the gayszlen (right) goes in with his head down and totally unprotected, allowing the opposing fencer to get a really beautiful hit to his head as she dodges his gayszlen. This is what you should do if you encounter someone who is eager to use the gayszlen and you wish to discourage them.

A safer position (both to avoid getting hit and to avoid injury, as I'll mention in the next section) is a more upright stance and a deep lunge, though keeping your shoulder up, as I mentioned earlier, reduces your range to that lower point.

Why don't some people allow it in tournaments?

Many tournaments, in my area and others, don't allow gayszlens. some ways this manifests are bans on all one-handed cuts, all one handed strikes altogether, including thrusts, hits to the leg below the knee, etc. Some people just don't like the gayszlen, think it's too hard to judge, think it doesn't have enough historical basis, or think it is dangerous to the person doing it or the person having it done to them. A lot of those reasons are laid out in this article, which, while I disagree with most of the points, makes those points pretty well. It's also the first result when you search on google for gayszlen, which makes me sad :( Another argument regarding the safety that isn't mentioned in that article is that to get additional reach and evade strikes from above, some people get really low when executing a gayszlen, even exposing the back of their head or body, which can lead to some really nasty hits to the back of your head or your spine, which are vulnerable areas even when wearing gear, are are often the parts of the body that have the least protective gear. In my opinion, any ruling that is intended to ban gayszlens that we've seen is too broad. banning one-handed cuts (or strikes altogether) means that whole sections of manuscripts or traditions (such as fiore's uno mano plays) can't be performed, banning cuts to the legs or parts of the legs can give an advantage to taller fencers, discarding them automatically because they're too difficult to judge the quality of can punish those who have worked to perfect them safely, etc. At the end of the day it doesn't really make a huge difference one way or the other, and every tournament organizer is biased in the way they make their ruleset one way or the other, but I think the gayszlen is unfairly maligned. In my opinion, with proper attention to levels of force, protective equipment, and judging, the gayszlen deserves a place in modern HEMA tournaments.

ALSO IT HAS GAY IN IT TEEEHEE!!

some people pronounce it "guy-slen" and I usually say "gay-slen" and I don't speak modern or medieval german so idk how it should be pronounced but I like saying gay :) because homosexuality get it???? I

I've made the gayszlen a bit of a meme in my local scene by shouting "GAYSZLEN" whenever I do it, like an anime character. This is typically regarded with friendly annoyance, and it makes hitting this silly ass technique SO much more satisfying and makes whiffing it a lot less embarrassing :)

anyways thanks for reading my long ass post ily <3 if anyone has additional thoughts, please leave them in the comments! I'd rather not debate anything, but I'd be happy to discuss intricacies of the gayszlen's use and interpretation if you're nice about it!

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not entirely sure how to cite this, German website is Germaning. Kal, Paulus: Fechtbuch, gewidmet dem Pfalzgrafen Ludwig - BSB Cgm 1507, [S.l.] Bayern, 2. Hälfte 15. Jh. (nicht nach 1479) [BSB-Hss Cgm 1507]

#hema#(this is from a fighting manual)#15th century#medieval manuscript#medieval clothing#doublet#hosen#hmmm#medieval art

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Longsword, I Want to Learn the Longsword

What they don't want you to know about HEMA is....

...that we're all figuring it out. Some of us since the 80s and 90s, some of us in the 2020s. Its an uphill fight for both teachers and students. As a coach, we have to crush dreams about the reality of what we teach, that arming sword and shield (as people understand it in pop culture) doesn't exist as far as most text goes and we are doing experimental archeology to get somewhere close to it. Like having to tell people that karate isn't action movies and flying kicks. They show up once and get bored. Now that I got the sad stuff out the way, let me help you get started in figuring it out. I am gonna assume that you either don't have a near by club or you don't have the money to attend.

Remember this is a sport, its a workout, but also its very young. Some people have studied most of their lives in this by now. A lot of people are the equivalent of a black belt for lack of a better word. But they aren't everywhere. First thing you'll need is to find out what you want to do and a friend to do it with. If you're lucky, you aren't interested in rapier and you can get a book, a pair of fencing masks, and make some LARP grade boffers and be off to the races. Rapier people I am sorry but you're going to need modern fencing jackets, gloves, and pants at minimum. So lets give you the menu on the longsword, basically you have Italy and Germany that quite literally wrote the books on the subjects. England and France don't have much and is side project after you learned the basics. With that said:

I want to learn:

The most popular thing: Liechtenauer / Pseudo-Peter Von Danzig

This is the meta. The most popular and the most amount of info you will find on longsword usually is about this guy's style from the other guy's book. Liechty wrote a poem for his students to keep his teaching committed to memory and his students and students' students wrote books explaining the poem. Cuts, thrusts, and chivalry abound.

Gritty street fighting, knight style: Fiore de'i Liberi

This one is as much martial art as it is fencing. Don't grapple or kick people as you're learning it. Your partners are not replaceable, do not break them. Fiore is popular and prefers the fundamentals add in some medieval Krav Maga and you get the picture.

The cool stuff like on TV: Joachim Meyer

This is my style! Meyer writes in the end days of the longsword. People still carried it for self-defense but the saber and rapier were starting to take center stage. His book teaches you everything; from how to throw your first basic cuts, to how to move, to scaring away opponents and drunk brawlers with weapons out with moves you'd see out of a action flick. Thrusts were nearly illegal for self-defense so he tells you to read the rapier chapter and take what he taught you there and stick it on to longsword if you really need it.

Hipsterise me: Philippo di Vadi or Paulus Hector Mair or Bauman

Bauman is actually the name of the guy who compiled the Bauman Fechtbuch (fightbook). The style in there is different than most German sources because it doesn't come from Liechty. Mair is a guy in the same tradition.

Vadi is on the shorter end as far as longsword goes but has been growing in attention. He's part of the Italian traditions and while he isn't as gritty as Fiore he's certainly not afraid of using the point and pommel and making you look dumb for even getting into a fight.

Most of these are available for free thanks to the community translators at: wiktenauer.com

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Asexual defenders practicing circa 1450.

Don't mess with us.

asexuality is word that describes an orientation, not a set of behaviors, ace people can do all kinds of sexual behaviors and still be asexual. some ace people have sex, some don't. some ace people kiss, some don't. some ace people masturbate, some don't. some ace people get homoerotically stabbed, some don't. it's as easy as that to understand.

32K notes

·

View notes

Text

Sword of the day (1/20/2025): Medieval training sword by Cold Steel

I'd like to preface this particular post with a disclaimer: this is a terrible training sword. It's overbuilt, awkwardly constructed, too stiff and pointy for safe thrusting, and it both handles and hits like an old minivan. You could break bones with this thing. There are better products out there, and if you're strapped for money you can even find safer options in a similar price point. The only decent use case I can think of for this thing is as an improvised self-defense tool - even then, you might as well just carry a heavy cane or something.

That said... well, I wasn't always so safety-conscious. The Cold Steel trainer was, for better or worse, my first "proper" sword.

I did a lot of swordfighting as a kid. I'd play at swords with anyone who was willing: siblings, family friends, whoever. To this end, we had a lot of toy swords kicking around the house, of various shapes and materials: wooden bokken, foam boffers, cheap NERF swords, and the like. Less-obvious sword substitutes saw their moments in the sun too, like Wiffle bats and reflector sticks (the latter made for an especially evocative wizard staff.) Heck, regular sticks from the woods got plenty of use as well.

Various objects that saw regular combat use in our front yard. The best time we had with these sword-like objects was spent, not in direct combat, but in a kind of shared storytelling experience: we would fight imaginary enemies of every kind, cutting down demons and robots in worlds of our own devising. We called these collective endeavors "games," but the rules were implicit, the scope enormous, and the creative process as natural as air. I could tell you very little now of the settings we devised, save that they invariably contained an immense battle between good and evil: a small band of heroes, thrown again and again against powers of primordial gloom. We spent many hours this way. I suspect I would see the stories we told as prosaic now. I'll never forget the emotions they imparted. We also fought, a lot. I was the oldest, and a bit of a bully; I enjoyed feeling strong. I'd swordfight anyone brave enough to try me. We went full force with the weapons available to us, and found pretty regularly that our toys simply weren't built to handle the strain: sticks broke, foam swords chipped, wiffle bats dented. I wanted something stronger, more "real," purpose-built for sparring. We looked around on Amazon for awhile, and stumbled on the Cold Steel polypropylene swords.

Me and my sibling each got to pick a sword. They picked this gladius.

I'll say this about Cold Steel: when they call their trainers "virtually unbreakable," they mean it. Polypropylene is a very dense and stiff plastic, and these trainers use a lot of it - they're solid all the way through. We beat these swords on trees, rocks, other sparring weapons, and anything else we could think of. Beyond a couple scuff marks, the only way I was able to damage them at all was with a saw. (I'll get to that in a moment.)

Eager to finally have a "real sword," I set about unearthing the necessary research materials to best use it. I'd taken some martial arts in middle school, and now I wanted to learn to swordfight properly - the way knights did. I found a website from 2001 that claimed to offer just that. Their membership fees were prohibitive, but I could take inspiration from the few resources they did offer for free: most importantly, an old translation of Sigmund Ringeck's Commentaries on Johann Liechtenauer's Fechtbuch, c. 1440. This particular historical manual was dedicated to the use of the longsword. I, not realizing I would need the (slightly more expensive) hand-and-a-half trainer, only had an arming sword. Undeterred, I set about interpreting the Master Strikes.

A grip intended for one-handed use

My endeavors were doomed from the start. The clunky arming sword, already difficult to swing about with one hand on account of its complete lack of balance, was downright uncomfortable to wield with two. The grip was far too short; the wheel pommel dug into my palm if I tried to grab it with my left hand. I didn't have the resources to purchase another sword, and the training tool I had was unacceptable. Drastic measures were in order. The house we lived in at the time was quite large, and it contained, among other amenities, an impressive basement. Half of the basement was done up with drywall and proper flooring, suitable for residential use; the other half was half-lit pipes and bare concrete, the bones of the house visible to anyone who cared to venture down. In the back of this skeletal tunnel was a good-sized plywood table with a vise, furnished with a couple shelves on the walls above. This was our workshop. The workbench was a mess of scattered screws, wood scraps and hand tools, perfect for tinkering and general foolishness. We were permitted to use this space at our leisure, and I applied myself there to the best of my abilities: pounding nails and carving wooden knives, most projects left incomplete, their purpose forgotten, like a caveman's laboratory. This was the space I employed for my latest ambitions. The first thing was to take off that horrible wheel pommel. Locking the sword into the table vise, I hacked away at it with a cheap Japanese hand saw, lopping off the sides of the pommel and squaring it off as best I could. Now the exposed length of plastic could serve as part of the grip, giving me more room for two-handed use. Without a pommel, however, my hand would just slip off the stub. Mere amputation was insufficient. A prosthetic was needed. I sawed off a chunk of pressure-treated lumber from a convenient scrap, roughly the size I wanted. This done, I hacked the chunk down to a crude imitation of a longsword pommel. Finally I put a hole in the exposed stump of my sword with a hand drill, drilled a similar hole through the new pommel, and drove a screw through pommel and sword hilt both. (A screw? A nail? I don't recall.) The operation was complete. I could now learn longsword as the German masters intended.

An approximate rendition of my modifications The operation was, for a time, a success. I could now swing my sword at the empty birdhouse in the front yard, and put both of my hands on the grip instead of just one! My long-term prospects in the field of swordplay, however, were nevertheless doomed. The Cold Steel trainers still had no concept of safety whatsoever, and for that matter, neither did we - we were fighting with no helmet, feeble hand protection, and a weapon almost purpose-built for damaging the skulls and fingers of everyone involved. My sibling, younger and more vulnerable than myself, soon lost any interest in facing me. At some point my hackjob of a pommel popped off the sword entirely, and I gave up the pursuit. I've made only small forays into European swordsmanship since then: I've picked up a couple more practice trainers (after significantly more research), but otherwise I haven't had the time or money to pursue the hobby farther. If I ever join a club in earnest, I'll be going into it with a lot more armchair knowledge (and a lot more caution) than I had in highschool... ...and if I ever have children myself someday, you can bet I won't be buying them swords from Cold Steel.

Total length: 39.5 in Blade length: 32.25 in Handle length: 7.25 in Weight: 29.3 oz Material: Polypropylene Point of balance: no

https://www.coldsteel.com/medieval-training-sword-waister

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

So, I obsess a bit over sidesword treatises (focused mainly on Dall'agocchie for sword alone and Manciolino for buckler pairing), but under recommendation from a friend of mine in Philly, I was directed to Heinrich von Gunterrodt's "The True Principles on the Art of Fencing". It's not solely a "rapier" treatise (sidesword really), but it focuses heavily on it.

German treatise, obviously, and written in 1579, but super freakishly bizarre in the fact that he references the I.33 fechtbuch several times in his buckler section. Additionally, his sidesword is all done in thumb grip - all of it. It's a super peculiar system that I recommend getting a look at if you ever have the time.

It also has this freak ass weapon in there. Look at this shit.

Thanks for the recommendation! I'll definitely have a look at it.

My focus so far has mainly been longsword and polearm, but I've sparred against a few guys who specialise in sidesword. And I've been meaning to try my hand at sword and buckler.

That is indeed a weird-looking weapon! Like some sort of... sword halberd hybrid? I can't imagine it would be very comfortable holding that thing at arm's length for long, lol.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

"Everyone fenced in Early Modern Germany, but not everyone was a fencer in the way that the Fechtbucher assume. Athletics were an important part of young mens' upbringing, and the artistic motif of the Children of the Sun depicted those athletics, which included fencing. What was the difference between fencing, and fencing as a vocation?

Adam Franti is the lead instructor of the Lansing Longsword Guild.

If you enjoyed the lecture, please consider buying Adam a coffee: https://ko-fi.com/adamfranti

Interested in having Adam give a lecture for your group? Reach out to LansingLongsword at gmail, or send a message on this channel!"

A great video lecture on the physical culture of the time many of the manuscripts we study in HEMA are from.

For anyone who hasn’t yet seen the following links:

.

.

.

.

Some advice on how to start studying the sources generally can be found in these older posts

.

.

.

.

Remember to check out A Guide to Starting a Liberation Martial Arts Gym as it may help with your own club/gym/dojo/school culture and approach.Check out their curriculum too.

.

.

.

.

Fear is the Mind Killer: How to Build a Training Culture that Fosters Strength and Resilience by Kajetan Sadowski may be relevant as well.

.

.

.

.

“How We Learn to Move: A Revolution in the Way We Coach & Practice Sports Skills” by Rob Gray as well as this post that goes over the basics of his constraints lead, ecological approach.

.

.

.

.

Another useful book to check out is The Theory and Practice of Historical European Martial Arts (while about HEMA, a lot of it is applicable to other historical martial arts clubs dealing with research and recreation of old fighting systems).

.

.

.

.

Trauma informed coaching and why it matters

.

.

.

.

Look at the previous posts in relation to running and cardio to learn how that relates to historical fencing.

.

.

.

.

Why having a systematic approach to training can be beneficial

.

.

.

.

Why we may not want one attack 10 000 times, nor 10 000 attacks done once, but a third option.

.

.

.

.

How consent and opting in function and why it matters.

.

.

.

.

More on tactics in fencing

.

.

.

.

Open vs closed skills

.

.

.

.

The three primary factors to safety within historical fencing

.

.

.

.

Worth checking out are this blogs tags on pedagogy and teaching for other related useful posts.

.

.

.

.

And if you train any weapon based form of historical fencing check out the ‘HEMA game archive’ where you can find a plethora of different drills, focused sparring and game options to use for effective, useful and fun training.

.

.

.

.

Check out the cool hemabookshelf facsimile project.

.

.

.

.

For more on how to use youtube content for learning historical fencing I suggest checking out these older posts on the concept of video study of sparring and tournament footage.

.

.

.

.

Consider getting some patches of this sort or these cool rashguards to show support for good causes or a t-shirt like to send a good message while at training.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

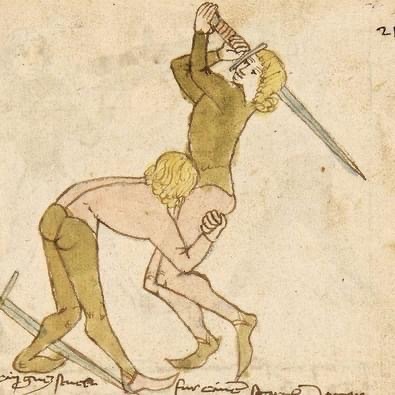

Queda de perna dupla para o Livro de Esgrima de Bauman ou Códice Wallerstein, Autor desconhecido

Double leg takedown from the Bauman Fechtbuch or Codex Wallerstein, Author unknown

They seem like good friends.

449 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Illustration of a longsword technique from the Codex Wallerstein, a 16th-century convolution of three 15th-century fechtbuch (combat manual) manuscripts, with a total of 221 pages. The codex is now housed at the Augsburg University library in Germany

More: https://bio.link/museumofartifacts

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

why is the historical shield that most closely resembles the standard gundam shield one that only exists in a random drawing in the gladiatoria fechtbuch

and why is it called a hungarian shield despite the fact that it looks nothing like any real hungarian shields I can find images of

I need a name for that type of shield that isn't "gundam shield" for the mech game and I refuse to call it a hungarian shield on the basis of it sounds weird.

#I'm currently calling it a Targebrace#(because the hungarian shield apparently qualifies as a subtype of targe and the gundam shield is (usually) mounted on the arm#and the brace in vambrace and rerebrace apparently come from the french 'bras' meaning arm#which I suppose means maybe it should be 'Bracetarge' instead. which I guess also works)

0 notes