#even though it's probably more common as a verb than as a noun at this point

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

i exist solely to test the expansiveness of accepted-word-databases in various word puzzle games. so far they have all failed to please me.

#the csw (sowpods) list is the least bad but they don't update it often enough#for example it recognises 'dogpile' as a noun but not a verb - and thus does not accept 'dogpiled' or 'dogpiling'#even though it's probably more common as a verb than as a noun at this point#it also has the usual blindspots for marginalised forms of english as well as some types of loanwords and jargon and internet neologisms#but it does better with those than most who attempt it

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

ive done a lot of translating to high valyrian in my day and id like to think im pretty good at it sometimes (the way ive spent literal hours researching how just one piece of grammar works to change a noun to an adverb or something is maybe insane)

anyway all that to say i usually know what to look for and how to apply it, but i am struggling with this new bit im trying to translate. “i disdain all glittering gold.”

ive replaced disdain with hate cause there doesnt seem to be a word for disdain in valyrian and hate is the closest approximation. same with glittering — replaced that with shine, and had to manually transform that to an adjective (jehikagon -> jehikere? dunno if its right)

so what i have now is “nyke buqan unir jehikere aeksion”

(im not as concerned with getting the word order right as i am with the rest of the grammar)

ive learned from a previous answer “nyke” is potentially (probably) unnecessary here, so that leaves it as “buqan unir jehikere aeksion,” but the unir there in the middle kinda makes it feel off and im not sure if maybe that also needs to be part of a compound word like valar or how to make it one if so because idk what part of valar is all and what part is men and how to fit aeksion into that equation.

i lost track of what my question was originally meant to be but i guess im wondering if im on the right track and if theres some guidance you may have to get me all the way there.

thank you for your time 🙏

Uhhhhhh... Not to be that dude, but...maybe be more concerned with that...?

I'm not sure if you know about this site, but my wiki is exhaustively updated with respect to High Valyrian, specifically. There's a team of people that work on High Valyrian and it's massive. For example, you could go to the entry for jehikagon and see that jehikere is wrong: it should be jehikare. And, of course, it has to agree with āeksion (note the long ā), so it should be jehikarior. To get the sense of repetitiveness (with "glittering"), you might add ā- to the front, so ājehikarior.

Now for "all", why not use the collective? This is how you get "All men must die", so it should work for "I distain all glittering gold". That would be āeksior. Of course, it would need to be in the accusative, so altogether it would be ājehikarior āeksȳndi. By adding the repetitive you kind of get the aliteration, too, since they both begin with ā.

Finally you have "disdain", for which buqagon serves. Aside from sound a little more posh, the difference between "disdain" and "hate" in English seems to be one of duration. The words "disdain" and "loathe" seem to emphasize that this is a character trait rather than a reaction. If you disdain something, you've given it some thought, have experience with it, and may use this as a way of describing or characterizing yourself. You can do this with "hate" as well, but it's a much more common word, and so can be used in other more basic ways, whereas "disdain" and "loathe" tend to only have specalized uses. To try to approximate this, you could use the frequentative with buqagon to imply a lengthy duration. That would give you jobuqan "I disdain". In fact, you could even use the aorist if you really wanted to imply that it was a description of yourself, i.e. jobuqin.

Now that you have the pieces, though, I really hate to say it, but the words must be in the right order. I mean, you can change the order of the noun and adjective, if you'd like, but you simply cannot put the verb first and think you've created a Valyrian sentence. It's not just "kind of" wrong: it's completely wrong. It'd be like suggesting "I him saw" is close enough in English because the forms are correct. It's not. It's wrong. This is not a minor part of the grammar you can ignore. High Valyrian is aggressively verb-final. The verb must be at the end.

All in all, that gives you:

Ājehikarior āeksȳndi jobuqin.

Hope that helps!

70 notes

·

View notes

Note

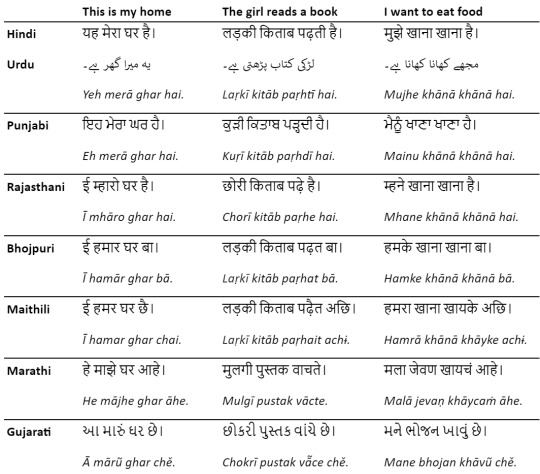

Are any of the other North Indian languages mutually intelligible with Hindi?

(other than Urdu)

Boy, did this ask take me down a rabbit hole. I have only studied Hindi and some Urdu, and my exposure to other Indian languages is mostly through fusion film songs that mix various languages. So if I make a mistake here, please feel free to expand and correct me!

India is home to a diverse range of languages, many of which share roots with Hindi in the Indo-Aryan language family. While some are highly mutually intelligible, others are more distinct but still share structural and lexical similarities.

When comparing languages with common roots, it's often helpful to look at the words that are probably the oldest, such as those for home, food, or basic verbs. Here's a comparison of Hindi and Urdu to six other Indian languages with three example sentences.

What we can see here:

Shared vocabulary: Words like घर, किताब and खाना are mostly consistent across the board and would likely be understood by many speakers of these languages. Words like पुस्तक, छोरी and भोजन are also familiar to Hindi speakers, though they might be considered more formal, regional or specific.

Grammar: all these languages follow the Subject-Object-Verb (SOV) sentence structure. Even if you encounter an unfamiliar word, this consistent syntax helps understanding and contextually deducing its meaning. Knowing where nouns, verbs and adverbs are likely placed in a sentence can be a huge advantage when learning or comparing these languages.

Script: Hindi uses Devanagari, Urdu uses Nastaliq or Naskh, Punjabi uses Gurmukhi in India and Shahmukhi (Perso-Arabian script similar to Urdu) in Pakistan. Gujarati has its own script, and others, like Maithili and Bhojpuri, also use Devanagari with minor regional tweaks.

So the answer to your question is: well yes, but actually no.

You can test how much you understand by listening to these songs! Some of them have a bit of Hindi influence or shared vocabulary mixed into them:

Punjabi

youtube

youtube

Rajasthani

youtube

youtube

Bhojpuri

youtube

Maithili

youtube

Marathi

youtube

youtube

Gujarati

youtube

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

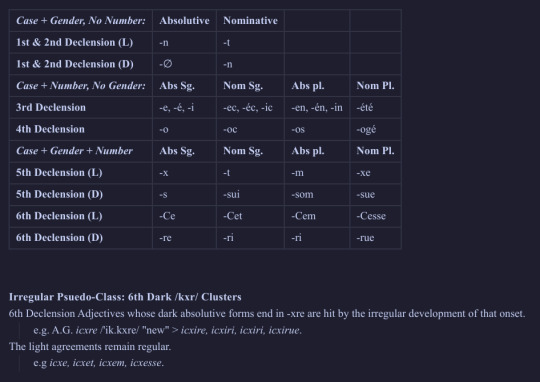

Neat Irregularity In Old Sogoic Adjective Agreement

I think this is the first time I've mentioned it on this blog, but Old Sogoic is a Sellan language (i.e, fairly closely related to High Gavellian), though the Old Sogoic period (c. 850–500 B.P.) came a fair time before the Cadan standardization of High Gavellian that I'm documenting (early centuries A.P.) or even the point where "High Gavellian" became a distinct concept outside of Koine (riight before the turn of the millennium).

I digress. The irregularity here is a splinter from Declension VI detailed down below. As a result of a sound-shift vowel insertion to break up an unwanted sequence at the syllable boundary, the 'irregular' class takes the root (this is romanisation, not ipa, though it is phonologically transparent atm) icx- and simply adds an -ir for gender agreement and then -e/-i/-i/-ue for case and number agreement. It's so nicely agglutinative!

but this is the irregular pattern. compare a similar stem in declension six like sios-. In the light gendered agreement pattern, it matches icx- exactly:

icxe, icxet, icxem, icxesse

siose, sioset, siosem, siosesse

buuut ofc the "expected" dark agreement pattern...

siosire, siosiri, siosiri, siosirue

...is completely incorrect! because that final consonant is only a part of the light stem, for some reason! the dark stem deletes it!

siore, siori, siori, siorue

It's all so very nice. The vowel insertion during the sound shifts on the xre /.kxre/ clusters prevented the consonant loss that hit every single other adjective in the class. Maybe if there were more preservation examples than this one (rather rare) cluster then it'd have spread through analogy/morphological leveling or somesuch, but it hasn't. so it's just an irregular pseudo-class that only retains some super common adjectives (as detailed in the pic, icxe/icxre "new" makes that cut). The rest of them have this fun stem consonant deletion thing going on. Which also means that if you hear a Declension VI adjective in its dark agreement form you've got like zero clue as to what the consonant at the end of its stem is. rip rip.

Again, maybe I'll level that out, but realistically what I'm probably going to do is collapse the adjectives into 2-3 declension classes max. Probably going to move them up into 5-6 as the language gets more (yes yay more) fusional. Unfortunately we've got a billion incoming noun cases (lots of adpositions just went postpositional & suffix mode) that I don't really see the adjectives agreeing with, but at the least that's one place where the marked nominative agreement is going to hold on. Rest of the language (family) is doing its level best to purge itself of any remnant ergativity.

Here's a language intro tangent:

Old Sogoic is somewhat fusional, though sound shifts have rendered its inflection system fairly neutered and highly syncretic. It's undergoing the same areal morpho-phonological reduction pressure that the nigh-isolating High Gavellian emerged from. Given the circumstances it managing to hold on to this much (16 verb inflections, up to 4 noun inflections, up to 8 adjective inflections, grammatical gender & number) is insane.

The adjective classes are weird and I like them a fair amount. The first/second declension distinction is barely a formality and only exists because of One insanely productive derivational suffix (the gods' strongest soldier, good work -on).

It also exists because this analysis lets me line up the adjectival inflection patterns with their cognate noun declension patterns. If Declension II didn't exist then I'd probably have to skip the number anyway.

Otherwise the six declensions are sorted into three pattern groups depending on their agreement behavior. I and II are defective when it comes to number agreement, III & IV don't agree for gender, and then finally V & VI have full agreement in all situations.

Going off what I mentioned earlier but wrote later:

As Old Sogoic evolves into Neo-Sogoic (where its speakers escape the black hole of isolation by ironically isolating the community from the rest of the sprachbund) planning on having it get even more fusional, which means that I'm probably going to have V & VI style patterns of full agreement extend to the entire adjective space. Hooray. This'll mainly favor the absolutive forms, but I won't see if I can't force the case-like suffixes to agglutinate to the adjectives too. That'll get a whole bunch of new agreements in real quick.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Guide to Language Domming, Pt. II

The Seven Key Phrases of Language Play

Welcome back! In Part I of this guide, I talked about what language play was, how you can engage in it with your little, and why it’s such a fun and immersive experience. I may also have mentioned that it’s possible to learn to language dom without being fluent in your target language beforehand. And in this part, I’m going to explain how.

Below are seven key phrases to keep in mind when you’re learning a language for play. With all of these, though, it’s not about translating the exact phrase - it’s about understanding the kinds of words highlighted, and being aware of them. These are language elements that common learning apps might not cover, and I’ll be including some helpful places you can look to fill in the gaps.

Beyond these, if you haven’t studied your target language much before, you probably will need to spend a week or two with DuoLingo, Youtube guides, and the like to get comfortable with language basics. Yes, it’s work, but isn’t it worth it to give your little one such a special experience? Plus, if you’ve ever wanted a good reason to go study a new language, it doesn’t get better or more fun than this!

Oh, and even if you have studied your target language quite a bit, or even if you consider yourself fluent, these might not be words or phrases you’ve thought much about, or are very familiar with. So read on, friend, and get ready to expand your vocabulary.

Phrase #1: “Good morning, Princess.”(Terms of endearment)

To be clear, “good morning” is fairly basic - Duolingo and the like will be sure to cover that in an early lesson. It’s the second part that’s trickier, and that’s because translating “princess,” or whatever word you like to use in English, isn’t going to cut it.

Common terms of endearment vary wildly from language to language. From the Spanish changuita (“little monkey”), to the Polish laleczko (“little doll”), every language has a wide assortment of colorful favorites. The lists are pretty easy to find online, and you’ll have plenty of great options no matter what you plan to study.

So why is it so important? Because for the duration of your play, this is essentially going to be your little’s name. Other than possibly the word “no” (if they’re an especially naughty little), your chosen term of endearment is going to be the word that they hear the most, and that they will have the strongest emotional association with when you’re done.

Phrase #2: “Now now, behave.”(Imperatives)

An imperative is essentially a command phrase - do this, don’t do that, and so on. In many languages, this is its own grammatical form, and learning imperatives means learning a few rules for verbs and their conjugations.

Now, all that sounds like it should be in a normal language syllabus, and it usually is. But I mention it here because this is one grammar lesson that you have to have to have down pat. Commands should be given clearly and quickly, especially if your little one has decided to be a bit of a brat. In fact, this is probably the most common way you’re going to be using verbs in play - you can’t really have much of a conversation, after all.

Some of the variations aren’t obvious - even with something as simple as “no!” it’s worth noting that some languages prefer “can not!” and some just say “bad!” So be sure to spend a little extra time on these lessons, so you can be ready to give some lessons of your own.

One last note on this: imperatives are probably the single most important part of language domming if you’re using it in a petplay context, and “training” your pet to follow commands in your target tongue. Now, that’s not something I’m personally experienced with, but boy does it sound like fun!

Phrase #3: “Would you like your teddy bear in the playpen?”(Household items)

As with imperatives above, common nouns for household items are already a part of the normal language lessons you’re likely to find. The tricky part here is that everyone’s household is different, especially when we throw in a whole bunch of paraphernalia. You might have your Italian words for sofa (“divano”) and refrigerator (“frigofieri”) down pat, but how about teddy bear (“orsacchiotto”)? How about baby bottle (“biberon”)? And did you know that the term used for playpen is just box? I sure didn’t, before I made this guide.

Obviously, not all of these are going to be featured in your standard beginners’ lessons, and Google is your friend. If you do use the translation tool though, be sure to swap back and worth to make sure it’s got the right word (if you put in “seal” because your little one has a cute baby seal, you may end up with the word for stamp, etc.). Also be sure to press that sound button to actually hear the word - some of them aren’t what they look like, and accent is important for the immersive experience!

Phrase #4: “Uh oh, did somebody make a pee-pee?”(Potty euphemisms)

Okay, you probably saw this one coming. It’s for those moments that so many AB/DLs and their caregivers look forward to - when we discover that our little has had a little accident. Language domming is all about creating a deeply immersive experience, after all, and what could be more immersive than being talked down to for using your diaper, in a language you don’t understand, knowing full well you’re about to be laid down on the mat and changed, and that you’re too little - and know too few words - to have any say about the matter? Sounds fun, right?

For those unfamiliar with the term, a euphemism is a ‘nice’ way of putting something that might not be so nice to talk about. With ‘potty’ related words, these are important, since technical terms for urination, defecation, and even diapers can be clunky and awkward. Knowing the right words to use for pee, poo (if you want to include that), potty, diaper, change, accident, and so on can go a long way.

Of all of the words covered on this list, these might be the trickiest to actually look up, but you can find some useful discussions in forums online. Here’s a lovely Wikihow guide on talking about poop in Spanish, and here’s a Reddit thread covering “polite ways to talk about bodily functions in German.”

Now, in the future, I’d love to start a repository of these lovely terms for ageplayers around the world to fill in, but that’s going to require you sharing this out with all your kinky friends! But I digress.

Phrase #5: “Ummmm… uh…”(Filler words)

Huh? Yes, believe it or not, knowing how speakers of your target language handle those awkward pauses we all have is important. The “ehhhh”s and “ahhh”s of the world are different, and you’ll want to get used to your target’s.

Why does it matter? Because accent is important. You want to create an immersive experience for your little, and sounding like a high schooler trying to fill a foreign language credit is not the way to do that. Having a confident accent (doesn’t mean it’s great - you won’t be tested on that) is crucial, and being able to maintain that when you’re looking for the words to say is a big deal.

One of the best ways to pick up on these filler words and how they’re said in your target language is to watch candid videos. Reality clips, interviews, man-on-the-street type deals - all of them will have people looking for what to say, and you’ll be able to see what they look like when they do.

Phrase #6: “Awwww, does my widdle pwincess want her stuffy-wuffy?”

(Diminutives)

If you’re wondering how to really baby-talk your little in your target language, the key is here, and it might be a bit more technical than you think. Baby-talking in language play, as it turns out, comes down to a combination of confident accent, CG attitude, familiar terms of endearment, and a whole bunch of diminutives. I’ve covered all of those things except the last - and it’s a big one.

Technically speaking, a diminutive is a modification of a word, used to convey smallness, endearment, or both. Tommy is a diminutive form of Tom, doggie is a diminutive from dog, and so on. When encountering foreign examples, they usually end up getting translated as ‘little’ + whatever the original root word was.

For many foreign languages, there are actually pretty clear rules about how to create a diminutive, and a lot of them have to do with endings added on, such as the Portuguese -inho / -inha, or the Czech -ka and -ička/-ečka. Wikipedia has a colossal list here, though you may need to have some knowledge of your target language’s noun cases and word structures to process it.

If all that sounds complicated, well, it can be at first. But once you nail that condescending tone and make your little just burn up blushing, it’s all going to worth it.

Phrase #7: “Oh, goodness, did I forget to turn off the thingamajig?”(Placeholders)

Last but not least on the list are those words that we use when we know exactly what we're talking about, but we don't know how to say it. And while catchalls like the English thingamajig, whatchamacallit, and doohickey do exist in other languages (including, amusingly, the Spanish chimichanga), this topic is much bigger than that.

The key point here is that you don't want to interrupt the immersive experience you've worked so hard to create, just because you happened to forget the word for toaster or the like. You can use the word for thingamajig. You can use the word for that. Or - and this can be our little secret - you can even make something up!

Remember, this isn’t a test. You’re not being asked to master a foreign language. Just to use what you know - maybe you’re doing a Duolingo crash course from scratch, maybe you took it in high school or college, maybe you know some from family - to make for the best, most immersive play experience you can give your little one. And hopefully, these phrases can help with that.

Phew. Hope you all learned a bit today! If you have any questions, or any suggestions for what I can add above, feel free to shoot me a DM. And if you want to help me build my repository of foreign language vocab for AB/DLs, please do reach out!

In the next and final part of the trilogy, I’ll be going over some slightly more advanced tips and tricks for language players, including a deeper dive into activities and props for play, combining language domming with other kinks, and even my picks on which languages most and least lend themselves to all this fun wackiness. As always, my friends, keep it kinky. - ONND

Pt. III Can Be Found Here

71 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey Profe 🍓:

Can you guide me through esdrújulas and how commands become them? They require the tílde, right?

When words are esdrújula, yes they require the tilde... not all commands are esdrújula but we'll get into it this is going to be a long one; but just know, it's not something you fully get at first, it's a pattern you recognize and keep recognizing as you go

I just want to quickly state that the entire topic is related to whether words are aguda, grave/llana, or esdrújula which is a very large topic that is a bit confusing - but it basically describes where you put your vocal emphasis on a word depending on if it ends in a noun, a consonant, N or S...

Again, not something you "learn" exactly but a pattern you realize you've been recognizing and how you know how to pronounce a word based on a pattern you've probably noticed without even trying, but then trying to understand it academically which is the weird part

Very big topic linguistically; I recommend looking it up on youtube but it's related to how to predict where to put a vocal emphasis on a word and if it should have an accent mark depending on syllables and what the word ends with

-

For your purpose though you're talking about esdrújula which means that a word has its vocal emphasis on the third to last syllable [antepenultimate]

A common example is la brújula which is a "compass"

The syllables in that are brú-ju-la

...That la is the last [ultimate] syllable, the ju is the second to last [penultimate], and brú is the third to last [antepenultimate]

Without an accent mark you would be inclined to put the emphasis on ju but because its emphasis is on brú it gets the accent mark to tell people that so they don't pronounce it wrong

-

With verb conjugations you're looking at more of a.... I don't know what the right word for it is but let's just say "imposed esdrújula"

By that I mean you're adding syllables to a word and that will change how it's pronounced

This is the basis being un making algún, ningún, or a counting word like veintiún "21 (of something)" have accent marks

By adding extra syllables you moved where the vocal emphasis would typically be. To make sure you understand we're talking about a root of un "one", that now takes an accent mark because if you didn't people would be pronouncing it wrong

[I said I wouldn't really go into it but most nouns ending in N have their vocal stresses on the second to last syllable like dicen, tienen, viven, hablan etc. because you want people to recognize un is from uno and related to "one" you're putting emphasis on that syllable which is unusual - hence an accent mark to keep people from messing it up]

This is the same idea behind seis as 6 turning to dieciséis 16 because people want you to know that it's related to the number 6, but most words ending in S have their vocal stress on the second to last syllable like tienes, caramelos, dulces, manzanas

Words like el compás "rhythm", además "furthermore" have the same vocal stress on the last syllable and end in S so they need the accent mark to not confuse people

-

Verbs also do this with commands, as well as some that use the infinitives or gerund forms + indirect objects, direct objects, and reflexive pronouns

With a verb in a command + objects, you're also adding syllables while also trying to keep the vocal stress originally where it was:

Habla. = Speak. Háblame. = Speak to me.

You turn a two syllable word into a three syllable word; but by keeping the stress on the same syllable you then need to add that accent mark to make sure people don't emphasize "bla"

This is the same for hábleme, or háblenme for usted and plural commands rather than simple hable, hablen.

...

This is somewhat different for a monosyllabic verb [often dar] or a verb with an irregular monosyllabic conjugation:

Da. = Give. Dame. = Give me. Dámelo. = Give it to me.

esdrújula by its nature needs at least three syllables, so immediately dame as a command only has two and works like normal so no accent mark, suddenly by adding a third syllable but still saying da has the stress means you need the accent mark

A somewhat unique thing then happens in usted it's that as an usted command it's dé "give", to differentiate it from de "of" it has that mark. But deme has no accent mark because it looks like a normal word with no accent mark needed - again better explained in a discussion of words that are either aguda or grave/llana - but then démelo "give it to me"

Another common one is poner to pon as a command but with reflexives and a direct object:

Pon. = Put. Ponte la ropa. = Put on your clothes. Póntela. = Put them on. [la ropa, collective noun] Ponte el vestido. = Put on the dress. Póntelo. = Put it on. Ponte los guantes. = Put on the gloves. Póntelos. = Put them on. Ponte las botas. = Put the boots on. Póntelas. = Put them on.

...Again compared to ponga in usted which already has two syllables, póngase "put on" or póngaselo-la-los-las can work like that too

This is also going to be why you see some verbs that have roots with poner, tener, venir etc conjugate a bit weird... like mantén is because ten is the command of tener for tú, now you have another syllable as mantén from mantener and it's a whole thing

...

Now I mentioned infinitives and gerund, and again this is easier to spot but it has to do with syllables again

Infinitives all have their tonic stress on the last syllable, so when you add things you're moving back that syllable from ultimate to penultimate to antepenultimate...

Necesito decir... = I need to say... Necesito decirte... = I need to tell you... Necesito decírtelo. = I need to tell it to you. / I need to tell you. Debo dar... = I should give... Debo darte... = I should give you... Debo dártelo. = I should give it to you.

This is why you might see something like ahora tendrás que vértelas conmigo as it's "you'll have to deal with me" but literally verse las caras "to deal with" kind of like "to see face face to face", so it became "see them with me" in a way as vértelas

Another common one is apañarse las coas "to handle things", and then sometimes as a command apáñatelas "deal with it / figure it out" or necesito apañármelas "I need to deal with it (myself)"

With gerund you're talking -ando or -iendo or -yendo. They're already multiple syllables so they always have an accent mark [on the -ándo, -iéndo, -yéndo] if you add to that word with a direct object, indirect object, and/or relflexive:

Me estás mintiendo. = You're lying to me. Estás mintiéndome. = You're lying to me. Se está volviendo loco/a. = They're going crazy. Está volviéndose loco/a. = They're going crazy. Les estoy diciendo la verdad. = I'm telling them [or "you all"] the truth. Estoy diciéndoles la verdad. = I'm telling them / you the truth.

-

What (thankfully?) makes this easier is that you can hear it and produce it pretty intuitively

It's just that the accent marks with esdrújula and especially with verbs is there so other people don't read the words wrong

It becomes a confusing topic because it's describing a thing a lot of people do naturally, but you can tell when someone gets the emphasis on the wrong syllable because it will sound off

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daily French words!

Intro:

Hi! I'm a French college student, and I study English literature and civilisation. I'm starting this page because I have a shit ton of extra French vocabulary to learn for exams, and it's a lot more fun to learn them through a tumblr page rather than just reading a piece of paper for hours!!!! All credits for the ideas for the first 160 main posts of this page goes to both of my French teachers this year, they're the ones who gathered up the lists- I obviously can't name them because I'd rather not dox myself (or them), but thanks!

Form :

(French word) : (French definition)

(example of the word's use in a French sentence)

(how common the word is out of ten, 1 being so uncommon people will look at you weird if you use it and 10 being common knowledge people will go "duh" at. please note this section will be the most subjective of the bunch and is purely based off my impression- the factors, such as social circle, time and place make it too difficult to have a more objective knowledge of how common said word is.)

(a possible translation in English) : (a definition in English because I like definitions)

(extra notes and precisions for context use, potential irregularities if it's a verb, other possible definitions, similarities, faux amis (see frequently used terms lower) or etymology because I'm a nerd)

Schedule :

Each week, ten words will come out : one each Monday, Tuesday, Thursday and Friday, and two each Wednesday, Saturday, and Sunday!

Posts will be uploaded around midday CEST, so between 11am and 2pm, depending how I schedule them/at what time I eat.

Extra requested words can be uploaded anytime from 6am CEST to 2am CEST (the next day).

Every main daily post will be gathered under the "main" tag, extras will be gathered under the "extras" tag, and other random posts I may feel free to upload about the most random college life shit ever (even if probably really rare) will be gathered under the "baguette" tag.

Things to note :

These words are not common! This is vocab improvement. If you're looking for basic knowledge of French vocab or common phrases, you may have to look elsewhere.

I sadly only speak two languages, English and French, so this blog is only accessible to people speaking one or both of these. If you'd like to translate it to other languages (especially since the additional notes are all in English, and a lot of notes and translations vary), feel free to do so but please DM me about it before starting the blog, and of course credit me!

If you'd like to request a word, do so through the page's asks! That's mostly useful if you'd like extra context on the word, its etymology or its history, or if you feel like it could be a cool word to be featured on this page. Of course, these extra words may take time to appear and will be scattered quite a lot through time since they require extra time and research, and I may refuse some of them if I don't think they'd be a good fit on here. Requests made through DMs will not be taken into account. Please only make requests through the ask feature, and wait until the asks open again if they're closed while I sort through them.

At the moment, I have 160 words, so enough content for four months (see schedule above to see how I count them). I cannot guarantee this page will update with the same schedule or update at all once I run out, depending on whether I still like doing it by then or prefer to stop. If it does stop updating though, I will leave all the posts up because knowledge is knowledge, and I may pick it up once in a while if I ever get bored and want to have fun with it again or if the asks supply me enough to sustain the page.

Frequently used terms (that you probably know already but I want to make sure everything is clear):

n. : nom/noun

nf. : nom féminin/feminine noun

nm. : nom masculin/masculine noun

nn. : nom neutre/neutral noun (we probably won't encounter any, but just in case, I'm putting this here!)

v. : verbe/verb

adj. : adjectif/adjective

sy. : synonyme/synonym

ant. : antonyme/antonym

litt./lit. : littéralement/literally

faux ami : expression that refers to a word that resembles another one in the same or a different language but that differs largely in sense.

About sources:

For most definitions and translations, I use the online Larousse dictionary (https://www.larousse.fr/dictionnaires/francais/), the Wikitionnaire (https://fr.wiktionary.org/wiki/) and WordReference (https://www.wordreference.com/).

For etymology and word history, I use a mix between the Wikitionnaire and the Centre National de Ressources Textuelles et Lexicale (CNRTL)'s website (https://www.cnrtl.fr), along with paper versions of etymology dictionaries.

#how do you tag#uh#intro post#french#words#i guess#french words#vocabulary#french vocabulary#college things#educational purposes#kinda#serious stuff#that is probably gonna be littered with dumb shit#wish me luck#exams#kind of i guess idk#i've been on this site for months and still cant tag#help#does this fall under the#main#tag or the#baguette#tag?#who knows#not me#okay i think that's enough tags#can't wait to do this!!! it's gonna be so much fun!!!!!!#i love languages#languages

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frislandic Historical Phonology

Ok so what the hell is with this phonology? Why this three-way aspiration contrast? What's with those aspirated labials? Those mutations? And why so many goddamn diphthongs?

All these questions and more will not really be answered but there'll at least be some more relevant information.

So Proto-Frislandic is a very nebulous entity, because many of the details of reconstruction are still hotly contested, some of which we'll discuss in a moment. For now the general consensus is on a reconstructed inventory like so:

*p *t *c *k

*pʰ *tʰ *cʰ *kʰ

(*s) *ʃ

*m *n

*r *l

*i *e *a *o *u

Roots had a C(n, l, r)V(ː)(n)CV structure with nouns and a C(n, l, r)V(ː)C- structure with verbs. *r did not occur root-initially, and do not seem to have been particularly common root-medially either. The exact quality of *l is also of some debate: some authors suggest it was likely some kind of lateral fricative (which is its primary reflex root-initially), rather than an approximant, but a resolution on this issue is likely impossible. *ʃ is also of uncertain quality, but it was likely retracted and slightly retroflxed, not palatal.

Authors tend to disagree most on the palatalised series, as there were probably three different sources for this in Pre-Proto-Frislandic: underived, palatalised dentals and palatalised velars.

The palatalisation of dentals before *i was most consistent (even today dentals never occur before reflexes of *i in native roots and there are scarce occurences even in loans; see e.g. zivl 'devil' and kerz 'believe' from Irish diabhal and creid respectively) and was a semi-productive part of derivation even in Proto-Frislandic, particularly for deriving basic agent nouns from verb roots. However it should be noted that paltalised *tʰ gave (not yet contrastive) *s not *cʰ (which in most varieties later merged with *ʃ to give modern /s/) so e.g. *kʰlat- 'return' → *kʰlaci 'returnee', *trotʰ- 'follow' → *trosi 'follower'. In modern Frislandic these are kald → kælz and dost → dors respectively, though note the nouns are lexicalised as 're-immigré, returning expat' and 'disciple' respectively. Some authors propose a distinct *t͡s from palatalised *t on the basis of some dialectal reflexes.

There's also evidence of palatalisation of velars, but this is less consistent outside of again agent noun forms (e.g. *ʃuk- 'speak a language' → *ʃuci 'speaker', *ʃrikʰ- 'sweep, brush' → *ʃricʰi 'sweeper'; modern sug → suz 'interpreter', sjisk → sjisj 'brush'). Some authors propose an additional series of indeterminate quality (some say labio-velar, some uvular) to explain forms such as *kriːta 'gland', modern girið, *kʰiːta 'sheath', modern kijð 'vagina'.

And there are still a number of palatals which cannot be explained through any kind of palatalisation process, such as *tʰoc- 'come', *coːta 'body', *cʰoːnti 'urine', modern toz, zuoð, sjuojn.

Additionally, while *tʰ *kʰ are still aspirates in most varieties to the present day, *pʰ *cʰ were likely already fricatives *ɸ *ç at the Proto-Frislandic stage. This shift was likely an early motivator for the breakdown of the aspiration dissimilation Grassman's Law-style which was present in pre-Proto-Frislandic and still is the general trend for native vocabulary and the formation of inanimate plurals (even seeing extension to loanword, e.g. gekirk /kəˈkʰirkʰ/ 'churches'), but is otherwise no longer productive (see previous example).

When it comes to the vowels, since unstressed root-final vowels were later lost, the contrasts in root-final vowels can be difficult to reconstruct outside of the context just outlined. The main contrast that can be adduced is between high *i *u and low *a *e *o, as these exhibit differing morphophonological behaviour, as well as being the motivation for the allomorphy of the modern Frislandic animate plural -u~o and genitive -i~e.

Already in Proto-Frislandic, the high vowels *i *u underwent syncope in certain morphololgical contexts, most notably in compounds, but traces of syncope in other contexts can be seen elsewhere (e.g. the instrument noun suffix -ll from *-li-tV). As such, there is a split between compounds where the first root ended in a high vowel and thus exhibited syncope and those where it ended in a low vowel and did not. In the former case stress was placed on the first syllable, the second later ended up undergoing vowel reduction and the consonant cluster was simplified, sometimes in rather radical ways (the full set of which will have to wait till another time), for example:

*citʰu + *paːʃa → *tiʰpːaːʃa to zitt 'jaw, chin' + bar 'stone' → zippar 'teeth'

*pʰonci + *pʰraːci → *pʰoɲpːʰraːci to onz 'sheep' + æræj 'bearer' → ojmpræj 'shepherd'

*traːkʰu + tʰaːci → *traʰtːaːci to darak 'length' + tæj 'dog' → dæstæj 'weasel'

*kʰoːku + *tuʃu → *kʰotːuʃu to kuo 'swamp' + dus 'berries' → koder 'cranberries'

*iːsi + *kʰreta → *iʰkːreta to ijr 'seaweed' + kærd 'bread' → ikkreð 'laverbread'

*tʰolu + *ʃeːli → *tʰolːeːli to toll 'shell' + siel 'slug' → tollel 'snail'

Note also that verb-noun compaunds exhibit the same behaviour.

*poːt-pʰaːli → *popːʰaːli to buoð bind' + æl town' → bopæl 'league'

*sinc-kʰuːnu → *siɲkːʰuːnu to sinz 'soak' + kwn 'bone' → sinkun 'bone broth'

*pent-tʰaːci → *pentːʰaːci to bænd 'guard' + tæj 'dog' → bentæj 'guard dog'

On the other hand, where the compound ended with a low vowel, syncope did not occur, stress was on the third vowel (the root vowel of the head of the compound) and the only substantial change was and is still lenition. This kind of compounding remains at least somewhat productive into Modern Frislandic, even with forms that would historically have behaved like high-vowel roots.

*maːte + *pala → *maːtepala to mæð 'pine tree' + ball 'seeds' → mæðvall 'pinenuts'

*mukʰa + *tuːkʰa → *mukʰatuːkʰa to mukk 'pigs' + dwk 'shark' → mukkðwk 'angel shark'

gat 'street' + tren 'train' → gættren 'tram'

sjuj 'tally, record' + kist 'box' → sjujkist 'computer'

So how did we get to modern Frislandic? Well I'm not going to go into all of the details but there's a few key points to make.

Firstly, vowel length an consonant length got slightly re-jiggled. Basically, single consonants after stressed short vowels became geminated (this was probably also when long vowels after geminates from cluster resolution shortened). Remaining single plain consonants would voice and then lenite intervocalically, while geminated forms of the aspirated stops *tʰ and *kʰ would be pre-aspirated, the singleton versions remaining post-aspirated. Note that this does not include the already post-aspirated geminates from cluster resolution seen above. The long vowels did remain different in quantity, as there were subsequent shifts in quality, including breaking (producing the first set of diphthongs ie uo ij w /iə̯ uə̯ əi̯ əu̯/). Furthermore the long vowels retained their quality when unstressed while the short ones were reduced. Thus:

*ʃuci → *ʃucːɨ → suz /syt͡s/

*citʰu → *ciʰtːɨ → zitt /t͡siʰt/

*kʰreta → *kʰrætːə → kærd /kʰært/

*kʰoːku → *kʰoːgɨ → kuo /kʰuə̯/

*kʰotːuʃu → *kʰotːɨʒɨ → koder /ˈkʰutər/

*maːtepala → *mæːdəbalːə → mæðvall /mæðˈβɑɬ/

Some other major changes to note. Firstly, the aspirated *pʰ and *cʰ behave differently. *pʰ (when not already geminated because of a former cluster) lenited to *ɸ and was sunsequently lost regardless of length and position (hence the discrepancy between the exonym Fri[sland] *ɸriːka~*ɸriːkaʃi-kʰuta and the modern reflexes Iri~Irijkud /ˈiri/~/ˌirəi̯ˈkʰyt/). Similarly, as *cʰ was likely lenited to *ç early on it participated in lenition in the same manner as the plain obstruents, resulting in its alternation being voiced-based rather than aspiration based.

A second change to the vowels not yet mentioned has to do with umlaut. The default reflex of Proto-Frislandic *e in modern Frislandic is /æ/. However, there was a process fo umlaut before original from vowels *i *e in a following syllable which resulted in its retention as a mid-front /e/. In this same environment original *a was fronted to /æ/ as well. The distance this umlaut effect can travel seems to have varied across Frisland: in some regions (in particular the capital Ojbar where the standard derives from) it only seems to have travelled one syllable, suggesting that in these cases it probably arose as a result of co-articulation effects on consonants, though there was seemingly a subsequent process of /æ/-dissimilation which produced forms such as bentæj /ˈpentʰæi̯/ 'guard-dog' (as opposed to *bæntæj). In other areas this instead seems to have been more like true umlaut, and these regions also tend to have expanded vowel systems due to the application of umlaut to the back-rounded vowels (but that's a story for another time).

Finally, those word-initial clusters underwent metathesis relatively late, with complete metathesis with short vowels and a kind of 'liquid-interpolating' with long vowels (see e.g .'weasel' above). some more educated speakers do pronounce such initial clusters in loanwords, but not always. Furthermore, this change only occurred word-initially, so there are still a lot of alternations of the kind gald~gelad /kɑlt/~/kəˈlɑt/ 'battle(s)', soroð~seruoð /ˈsuruð/~/səˈruə̯ð/ 'spear(s)' and bænll~bonæll /pænɬ/~/puˈnæɬ/ 'walking stick(s). This has even undergone extension to loanwords in some cases, such as koron~gekruon /ˈkʰurun/~/kəˈkʰruə̯n/ 'crown(s)' or sjuru~sjirw /ˈɕyry/~/ɕiˈrəu̯/ 'screw(s)'.

So yeah a bit long, hopefully I'll actually get onto dialectology next time.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ghilan'naelvish II

(This took me much longer than expected, sorry guys)

Once Rook & friends hack Razikale down to a sliver of health, Ghilan’nain snarls, “They take too much,” and commands her to return. Razikale is melted down, reformed, then returned to the moat, emerging as the Eborsisk from [ the 1988 movie, “Willow”. ]

Again, Ghilan’nain has two lines here:

"Essana ellath vallan."

(Spoken as Razikale’s previous form is manipulated into something else)

This one took me forever, not only because the phonemes are so common but also because of how little sense it makes. This line reads more like ‘words’ than ’dialogue’. Eventually I realised that may actually be the point: it's an incantation.

Essana = change/reform

This one I'm pretty confident of. I found multiple, completely different, ways of translating it that all break down to some variation of “become something else”.

e (v. inf. be) + sa (another, again) + nas (soul, self ; from) literally: from (you/yourself) become again

Ellath = Requirement ; force

This sounds like it’s being pronounced with a soft 's' (/s/ = simple, sun) rather than the ‘th’ (/θ/ = thing, thought) that’s shown. That might make more sense, as 'lath' is almost always used for love, lovers, and intimacy. I did find a (canonical, if archaic) reference of 'lath' as “need”, not necessarily romantic or sexual, and if that’s the case, ‘El’ could be the article or superlative rather than a possessive "our".

90% of my time was swapping out various interpretations of this word. Here's a few:

El + lath = The need (as in, ‘there is need for’) ; our needs ; requirement El + ath = piece, small amount (superlative + divide, part, fraction) El + lath = the love ; our love ; obsession ; devotion El + las = force (superlative + give, grant) ; bestow ; gift Elas = can/may, conjugated E + las = become hope ; memory ; ambition e + la + ath = being / become (v. to be + intensifier + noun from verb action - though this is kind of like making a word out of “ing”, “epic” and “ish”).

I trust you see the issue.

In context, “need/requirement” makes the most sense, but doesn't scan as well. As an incantation, the words stand on their own as commands.

Vallan = summon / invite

vall (v. bid/invite/order/summon) + an (suff. location/place) ; an (posessive) vall (same, but conjugated)

Without the ’s’ this is probably val/valla, as it was used by the guardian spirits in Trespasser. If the Inquisitor knows the passphrase, they stand down and invite you through with, “vallem (vall + em “[I] welcome/invite/bid”) as part of the phrase, "atish'all vallem". Somehow I can't imagine Ghilan'nain politely asking Raz to go stand on their marker, pretty please with a cherry on top, but if paired with ellath, it may tie together as "demand" or "order".

I can't say with 100% confidence what each word in this line means -- the context is doing most of the heavy lifting -- but there's enough to get what it's trying to say conceptually.

~ "Reconstruction is necessary, heed my order"

“Vallasan inall lasa!“

(Spoken authoritatively as Razikale reappears on the battlefield)

Vallasan = place of life ; body

vallas (life) + an (location suffix; possessive suffix)

Vallas as a root word has multiple meanings. We’ve even seen “vallasan” in canon — it’s the name of a unique bow in Jaws of Hakkon — though we have to infer its meaning. What’s weird about Ghilan’nain’s use of it here is that's [ very clearly not what she's saying ]. Whatever word she's using has two syllables; the "lla” has been dropped. That said, I think this is a line read error rather than a captioning error -- the translation makes more sense as shown.

Inall = dwellers / lives

ina (v. to live, to dwell - conjugated) ; + al (may indicate collective grouping)

Lasa = grant/allow/give

= "Bring me the bodies (of the living)"

Ghilan’nain’s Elvish

People seemed to enjoy the psychic bitchfight post so I figured I’d do one for Ghilan’nain’s lines in the ‘Siege of Weisshaupt’, too. Once again, I'm no expert, all glory goes to to [ FenXshiral ], and remember this is a vibe-based language so results vary with context, inflection, speaker and so on.

In the lead-up to the boss battle, First Warden Jowin will show up to take Davrin’s place as final sacrifice, only to be snatched up by Ghilan’nain before he can deliver the blow. After remarking on the quality of his blood, Ghil rips out his heart, turns it into an archdemon strength buff, then drops the used-up Warden like hot garbage. A moment later Wyrm!Razikale emerges from the moat to start the fight.

Ghilan’nain has two lines in this cutscene:

“Lasa hedallin ghellara”

(Spoken either to or about the First Warden as she manipulates his blood/heart).

Lasa = grant/allow/give

hedallin = blood of a noble kill/sacrifice; blood of [your] defeat

1. hel/hell (adj. noble, moral, just) + dala (v. kill, destroy) + lin (n. blood, person m.)

or 2. [hela (v. contest, oppose, fight) + dala (v. kill, destroy)] + lin (n. blood, person m.)

The use of ‘noble kill’/‘blood of your defeat’/‘sacrificial blood’ feels very deliberate here. Just before Ghilan’nain grabs him, Jowin recites the Grey Warden motto, “In war, victory! In peace, vigilance! In death, sacrifice!” . She’s throwing his words back at him, saying his ‘sacrifice’ would’ve been a waste... she'll put it to better use. She even taunts Rook with this later in the fight: “Witness! A Warden’s blood to birth your own destruction.”

ghellara = [my] beast more strong

ghe (n. monster, beast, creature) + elvara (v. to make difficult, hardy, sturdy, complex; from adj. elvar) + el (more, much, many. Used as a superlative) + ara (pron. sb. poss. my)

= “The blood from your sacrifice will strengthen my beast.”

"fenathra mellas”

(Spoken as Razikale’s transformation completes)

The natural assumption is fen = wolf, which would result in: fen (wolf) + ath (embodiment of) + ra (prn. it) or ara (my, possessive), making it, ‘the wolf’ in a kinda roundabout way. More like, “that wolf guy” or even, "my wolf guy" instead of a name or title. But I don’t think Ghilan’nain is invoking Solas or "the wolf” here. He isn’t an opponent at this point in the game, and neither her nor Elgar’nan see him as a real threat anyway. Additionally, the way she says the word ‘fenathra’ is quite soft — almost wistful — especially by comparison to the deep, guttural, delivery of, “mellas”. I think the root word she’s using here is actually ‘fenor’.

She calls Razikale her greatest creation. She mourns her death; pitifully telling Elgar’nan that Rook took her away. Razikale is more than just important to her — she is the very embodiment of the word 'precious'.

fenathra = My Precious One

fenor (precious) + athe (used to change the meaning of an existing word into, ‘physical manifestation of’, or ‘embodiment of’, eg. “the dead��� from death) + ara (my)

Mellas = Allow now / Go!

melana (adv. now, in relation to ‘time’ or ‘when’) + lasa (v. grant, allow, give, let - imperative verb form)

= “Go, My Precious One!”

I've been working on her remaining lines for several days now and am currently tearing my hair out about it, but I will add them to this post as a reblog once I finish!

As a bonus I'll throw in Solas' dialogue to Davrin when he briefly joins your party at the end of the game.

Dialogue source: Solas Interaction with All Companions [ x ]

"Mala shivanas ar athim"

mala (your) shivana (to do one’s duty, conjugated) ar (I) athim (humble, humility)

The Elvish scans in Solas’ Hallelujah cadence, so I preserved it for the translation.

= “I am humbled by your duty," or, "Your sense of duty humbles me"

#dragon age: the veilguard#dragon age: veilguard#DA:TV#DA:V#elvhen cipher#elvhen translation#ghilan'nain#DA elvish

169 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey! I hope you feel better soon

We haven't had a good long linguistics rant from you in a while!! How about you tell us about your favourite lingustical feature or occurrence in a language? Something like a weird grammatical feature or how a language changed

If this doesn't trigger any rant you have stored feel free to educate on any topic you can spontaneously think of, I'd love to hear it :D

ALRIGHT KARO, let's go!! This is a continuation of the other ask I answered recently, and is the second part in a series about linguistic complexity. I suggest you check that one out first for this to properly make sense! (I don't know how to link but uh. it's the post behind this on my blog)

Summary of previous points: the complexity of a language has nothing to do with the 'complexity' of the people that speak it; complexity is really bloody hard to measure; some linguists in an attempt to be not racist argue that 'all languages are equally complex', but this doesn't really seem to be the case, and also still equates cognitive ability with complexity of language which is just...not how things work; arguing languages have different amounts of complexity has literally nothing to do with the cognitive abilities of those who speak it.

Ok. Chinese.

Normally when we look at complexity we like to look at things like number of verb classes, noun classes, and so on. But Chinese doesn't really do any of this.

So what do Chinese and languages like Chinese do that is so challenging to the equicomplexity hypothesis, the idea that all languages are equally complex? I’ll start by talking about some of the common properties of isolating languages - and these properties are often actually used as examples of why these languages are as complex, just in different ways. Oh Melissa, I hear you ask in wide-eyed admiration/curiousity. What are they? By isolating languages, I mean languages that tend to have monosyllabic words, little to no conjugation, particles instead of verb or noun endings, and so on: so languages like Vietnamese, Chinese, Thai and many others in East and South East Asia.

Here’s a list of funky things in isolating languages that may or may not make a language more complex than linguists don't really know what to do with:

Classifiers

Chengyu and 4-word expressions

Verb reduplication, serialisation and resultative verbs

'Lexical verbosity' = complex compounding and word forming strategies

Pragmatics

Syntax

I'll talk about the first two briefly, but I don't have space for all. For clarity of signposting my argument: many linguists use these as explanations of why languages like Chinese are as complex, but I'm going to demonstrate afterwards why the situation is a bit more complicated than that. You could even say it's...complex.

1) Classifiers

You know about classifiers in Chinese, but what you may be interested to learn is that almost all isolating languages in South East Asia use them, and many in fact borrow from each other. The tonal, isolating languages in South East Asia have historically had a lot of contact through intense trade and migration, and as such share a lot of properties. Some classifiers just have to go with the noun: 一只狗,一条河 etc. First of all, if we're defining complexity as 'the added stuff you have to remember when you learn it' (my professors hate me), it's clear that these are added complexity in exactly the same way gender is. Why is it X, and not Y? Well, you can give vague answers ('it's sort of...ribbony' or 'it's kinda...flat'), but more often than not you choose the classifier based on the vibe. Which is something you just have to remember.

Secondly, many classifiers actually have the added ability to modify the type of noun they're describing. These are familiar too in languages like English: a herd of cattle versus a head of cattle. So we have 一枝花 which is a flower but on a stem ('a stem of flower'), but also 一朵花 which is a flower but without the stem (think like...'a blob of flower'). Similarly with clouds - you could have a 一朵云 'blob of cloud' (like a nice, fluffy cloud in a children's book), but you could also have 一片云 which is like a huge, straight flat cloud like the sea...and so on. These 'measure words' do more than measure: they add additional information that the noun itself does not give.

Already we're beginning to see the outline of the problem. Grammatical complexity is...well, grammatical. We count the stuff which languages require you to express, not the optional stuff - and that's grammar. The difference between better and best is clearly grammatical, as is go and went. But what about between 'a blob of cloud' versus 'a plain of cloud'? Is that grammatical? Well, maybe: you do have to include a measure word when you say there's one of it, and in many Chinese languages that are not Mandarin you have to include them every single time you use a possessive: my pair of shoes, my blob of flower etc. But you don't always have to include one specific classifier - there are multiple options, all of which are grammatical. So should we include classifiers as part of the grammar? Or part of the vocabulary (the 'lexicon')?

Err. Next?

2) Chengyu and 4-character expressions + 4) Lexical verbosity

This might seem a bit weird: these are obviously parts of the vocab! What's weirder, though, is that many isolating languages have chengyu, not just Chinese. And if you don't use them, many native speakers surveys suggest you don't sound native. This links to point number 4, which is lexical verbosity. 'Lexical verbosity' means a language has the ability to express things creativity, in many different manners, all of which may have a slightly different nuance. The kind of thing you love to read and analyse and hate to translate.

But it is important. If we look at the systems that make up the grand total of a language, vocabulary is obviously one of them: a language with 1 million root forms is clearly more 'complex', if all else is exactly the same, than a language with 500,000. Without even getting into the whole debacle about 'what even is a word', a language that has multiple registers (dialect, regional, literary, official etc) that all interact is always going to be more complex than one that doesn't, just because there's more of it. More rules, more words, more stuff.

Similarly, something that is the backbone of modern Chinese 'grammar' and yet you may never have thought of as such is is compound words. We don't tend to traditionally teach this as grammar, and I don't have time to give a masterclass on it now, but let me assure you that compounding - across the world's language - is hugely varied. Some languages let you make anything a compound; some only allow noun+noun compounds (so no 'blackbird', as black is an adjective); some only allow head+head compound (so no 'sabretooth', because a sabretooth is a type of tiger, not tooth); some only allow compounds one way ('ring finger' but not 'finger ring': though English does allow the other way around in some other words), and so on.

You'll have heard time and time again that 'Chinese is an isolating language, and isolating languages like monosyllabic words'. Well. Sort of. You will also have noticed yourself that actually most modern Chinese words are disyllabic: 学习,工作,休息,吃饭 and so on. This is radically different to Classical Chinese, where the majority were genuinely one syllable. But many Chinese speakers still have access to the words in the compounds, and so they can be manipulated on a character-by-character basis: most adults will be able to look at 学习 and understand that 学 and 习 both exist as separate words: 开学,学生,复习,练习 and so on.

I'm going to sort of have to ask you to take my word on it as I don't have time to prove how unique it is, but the ability that Chinese has to turn literally anything into a compound is staggering. It's insane. It's...oh god I'm tearing up slightly it's just a LOT guys ok. It's a lot. There are 20000000 synonyms for anything you could ever want, all with slightly different nuances, because unlike many other languages, Chinese allows compounds where the two bits of the compound mean, largely speaking, very similar things. So yes, you have compounds like 开学 which is the shortened version of 开始学习, or ones with an object like 吃饭 or 睡觉, but you also have compounds like 工作 where both 工 and 作 kind of...mean 'to work'...and 休息 where both 休 and 息 mean 'to rest'...and so on. So you can have 感 and 情 and 爱 and 心 but also 感情 and 情感 and 爱情 and 情爱 and 心情 and 心爱 and 爱心 and so on, and they all mean different things. And don't even get me started on resultative verbs: 学到,学会,学好,学完, and so on...

What is all of this, if not complex? It's not grammatical - except that the process of compound forming, that allows for so many different compounds, is grammatical. We can't make the difference between学会,学好 and 学完 anywhere near as easily in English, and in Chinese you do sort of have to add the end bit. So...do we count this under complexity? And if not, we should probably count it elsewhere? Because it's kind of insane. And learners have to use it, much like the example I gave of English prepositions, and it takes them a bloody long time. But then where?

Ok. I haven't had a chance to talk about everything, but you get the picture: there are things in Chinese that, unlike European languages, do not neatly fit into the 'grammar' versus 'vocabulary' boxes we have built for ourselves, because as a language it just works very differently to the ones we've used as models. (Though some of the problems, in fact, are similar: German is also very adept at compounding.) But as interesting as that difference is, the goal of typology as a sub-discipline of linguistics is to talk about and research the types of linguistic diversity around the world, so we can't stop there by acknowledging our models don't fit. We have to go further. We have to stop, and think: What does this mean for the models that we have built?

This is where we get into theoretically rather boggy ground. We weren't before?? No, like marsh of the dead boggy. Linguists don't know it...they go round, for miles and miles and miles....

Because unfortunately there isn't a clear answer. If we dismiss these things as 'lexical' and therefore irrelevant to the grammar, that is a) ignoring their grammatical function, b) ignoring the fact that the lexicon is also a system that needs to be learnt, and has often very clear rules on word-building that are also 'grammatical', and c) essentially playing a game of theoretical pass-the-parcel. It's your problem, not mine: it's in the lexicon, not the grammar. Blah blah blah. Because whoever's problem it is, we still have to account for this complexity somehow when we want to compare literally any languages that are substantially different at all.

On the other side of things, however, if we argue that 'Chinese is as complex as Abkhaz, because it makes up for a lack of complexity in Y by all this complexity in X' (and therefore all languages = equally complex), this ignores the fact that compounding and irregular verbs belong to two very different systems. The kind of mistake you make when you use the wrong classifier intuitively seems to be on another level of 'wrongness' to the kind where you conjugate a verb in the wrong way. One is 'wrong'. The other is just 'not what we say'. It's the same as the use of prepositions in English: some are obviously wrong (I don't sleep 'at my bed') but some are just weird, and for many there are multiple options ('at the weekend', 'on the weekend'). Is saying 'I am on the town' the same level of wrongness as saying 'I goed to the shops'? Intuitively we might want to say the second is a 'worse' mistake. In which case, what are they exactly? They're both 'grammar', but totally different systems. And where do you draw the line?

Here's the thing about the equicomplexity argument. As established, it stems from a nice ideological background that nevertheless conflates cognition and linguistic complexity. Once you realise that no, the two are completely separate, you're under no theoretical or ideological compulsion to have languages be equally complex at all. Why should they be at all? Some languages just have more stuff in them: some have loads of vowels, and loads of consonants, and some have loads of grammar. Others have less. They all do basically the same job. Why is that a big deal?

Where the argument comes into its biggest problem, though, is that if a language like Chinese is already as complex as a language like Abkhaz...what happens when we meet Classical Chinese?

Classical Chinese. An eldritch behemoth lurking with tendrils of grass-style calligraphy belching perfect prose just behind the horizon.

Let's look at Modern Chinese for a moment. It has some particles: six or so, depending on how you count them. You could include these as being critical to the grammar, and they are.

A common dictionary of Classical Chinese particles lists 694.

To be fair, a lot of these survive as verbs, nouns and so on. Classical Chinese was very verb-schmerb when it came to functional categories, and most nouns can be verbs, and vice versa. It's all just about the vibe. But still. Six hundred and ninety four.

Some of these are optional - they're the nice 'omggg' equivalent of the modern tone particles at the end of a sentence. Some of them are smushed versions of two different particles, like 啦. Some of these, however, really do seem to have very grammatical features. Of these 694, 17 are listed as meaning ‘subsequent to and later than X’, and 8 indicate imposition of a stress upon the word they precede or follow. Some are syntactic: there are, for instance, 8 different particles solely for the purpose of fronting information: 'the man saw he'. That is very much a grammatical role, in every sense of the word.

The copula system ('to be') is also huuuuuuugely complex. I could write a whole other post about this, but I'll just say for now that the copula in Classical Chinese could be specific to degrees of logical preciseness that would make the biggest Lojban-loving computer programmer weep into his Star Trek blanket. As in, the system of positive copulas distinguishes between 6 different polar-positive copulas (A is B), 2 insistent positive (A is B), 19 restricted positive (A is only B), and 15 of common inclusion (A is like B). Some other copulas can make such distinctions as ‘A becomes or acts as B’, ‘A would be B’, ‘may A not be B?’ and so on. Copulas may also be used in a sort of causal way (not 'casual'), creating very specific relationships like ‘A does not merely because of B’ or ‘A is not Y such that B is X’.

WHEW. And all we have in modern Chinese is 是。

I think we can see that this is a little more complex. So saying 'Modern Chinese is as complex as Abkhaz, just in a different way' leaves no space for Classical Chinese to be even more complex...so....where does that leave us?

Uhhhhhh. Errrrrr.

(Don't worry, that's basically where the entire linguistics community is at too.)

The thing is, all these weird and wacky things that Classical Chinese is able to do are all optional. This is where the problem is. Our understanding of complexity, if you hark back to my last post so many moons ago, is that it's the description of what a language requires you to do. We equate that with grammar because in most of the languages we're familiar with, you can't just pick and choose whether to conjugate a verb or use a tense. If you are talking in third person, the verb has to change. It just...does. You can't not do it if you feel like it. There's not such thing as 'poetic license' - except in languages like Classical Chinese, well. There sort of is.

The problem both modern Chinese and Classical Chinese shows us to a different extent is that some languages are capable of highly grammatical things, but with a degree of optionality we would not expect. Classical Chinese can accurately stipulate to the Nth degree what, exactly, the grammatical relationship between two agents are in a way that is undoubtedly and even aggressively logical. But...it doesn't have to. As anybody who has tried anything with Classical Chinese knows, reading things without context is an absolute fucking nightmare. As a language it has the ability to also say something like 臣臣 which in context means 'when a minister acts as a minister'...but literally just means...minister minister. Go figure. It doesn't have to do any of these myriad complex things it's capable of at all.

So...what does this mean? What does all of this mean, for the question of whether all languages are equally complex?

Whilst I agree that the situation with Classical Chinese is fully batshit insane, the fact is most isolating languages are more like Modern Chinese: they don't do all of this stuff. And whilst classifiers and compounds are challenging, they're not quite the same as the strict binary correct/incorrect of many systems. I'm also just not convinced that languages need to be equally complex. However.

HOWEVER. In this essay/rant/lecture (?), I've raised more questions than I've answered. That's deliberate. I both think that a) the type of complexity Chinese shows is not 'enough' to work as a 'trade off' compared to languages like Abkhaz, and b) that this 'grammatical verbosity' and optionality of grammatical structures is something we don't know how to deal with at all. These are two beliefs that can co-exist. Classical Chinese especially is a huge challenge to current understandings of complexity, whichever side of the equicomplexity argument you stand on.

Because where do you place optionality in all of this? Choice? If a certain structure can express something grammatical, but you don't have to include it - is that more complex, or less so? Where do we rank optional features in our understanding of grammar? It's a totally new dimension, and adds a richness to our understanding that we simply wouldn't have got if we hadn't looked at isolating languages. This, right here, is the point of typology: to inform theory, and challenge it.

What do we do with this sort of complexity at all?

I don't know. And I don't think many professional linguists do either.

- meichenxi out

#and that my friends is why I love Classical Chinese so much#askies#meichenxi manages#thank you karo that was very very very interesting!!#it's late now so I'll check over it again tomorrow but I don't imagine I'll be inundated with reblogs lmao#linguistics#lingblr#langblr#classical chinese#chinese#modern chinese

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is going to be a bit long-winded, but hopefully it'll be enlightening for anyone interested in Norwegian.

So I've been thinking about Norwegian sentence structure, and I've come to the conclusion that Norwegian is actually much better described as a kind of VSO language than as an SVO language or even a V2 language. Except there's a twist to it that is responsible for 90% of the confusion new learners have about the order of words in Norwegian.

Let's start on the confusing end.

== THE BLATANT LIES OF SVO ==

Many sources will list Norwegian as an SVO language, which is to say that the core elements of a sentence come in the order subject (who does), verb (what is done), object (who is it done to).

This is true for most basic sentences, but it breaks down very quickly the moment you add something as simple as an adverbial phrase (something about the manner, time, reason, etc).

Example 1:

EN: I eat breakfast in the morning.

NO: Jeg spiser frokost om morgenen.

Breakdown: Subject, verb, object, time adverbial.

This seems reasonable enough. That's a basic SVO sentence with an adverbial phrase at the end, SVO(A). But sometimes you want to put the adverbial phrase at the beginning of the sentence. Look what happens:

Example 2:

EN: In the morning, I eat breakfast.

NO: Om morgenen spiser jeg frokost.

Breakdown: Time adverbial, verb, subject, object.

The subject and verb switched places with each other, just because something was added before them. This (A)VSO sentence makes very little sense as SVO and looks like a strange exception, but this happens any time you put something at the beginning of the sentence besides the subject.

To make matters worse, this is still a correct sentence:

Example 3:

EN literal: Breakfast eat I in the morning.

NO: Frokost spiser jeg om morgenen.

Breakdown: Object, verb, subject, time adverbial.

What?? This is OVS(A), the exact opposite of SVO. The fact I'm using "jeg" and not "meg" still makes it unambiguous that I'm the one eating the breakfast rather than the other way around, but you can do this with plain nouns, which don't mark whether they're subject or object, too.

Example 4:

EN literal: The cat feeds my sister.

NO: Katten mater søsteren min.

Breakdown: Object, verb, subject.

The only things marking whether this is SVO or OVS are context, common sense and sometimes intonation. Both readings are grammatically correct, though the sister is probably feeding the cat.

== THE LINGUISTIC SHRUG ==

Because of all of these apparent "exceptions", more advanced sources will tell you Norwegian is a "V2 language". This is a fancy way of saying the verb goes second, no matter how everything else around it is arranged. (A)VSO? The verb is second after the adverbial. SVO, OVS? The verb is second so it doesn't matter.

That still has a couple significant flaws, though. For one thing, V2 is essentially throwing your hands up and saying "I don't know how this works, so here's the one thing that seems consistent." It doesn't explain how anything else in the sentence works, such as why (A)VSO is allowed but not (A)VOS.

And for another, there are plenty of times where the verb does not come second. A particularly frequent example is yes/no questions, where the word order (and tone) is the main thing setting it apart from a basic statement.

Example 5:

EN: Does your sister feed the cat?

EN literal: Feeds your sister the cat?

NO: Mater søsteren din katten?

Breakdown: Verb, subject, object.

Orders are also given with the verb first:

Example 6:

EN: Feed the cat!

NO: Mat katten!

Breakdown: Verb, object.

Subclauses tend to be SVO, but the specific type called relative clauses can be SV or VO. Admittedly the logic behind this one is tangential to my overall point in this post, but it does put the verb in a non-second position within the subclause:

Example 7:

EN: My sister, who feeds the cat, eats breakfast.

NO: Søsteren min, som mater katten, spiser frokost.

Breakdown: Main subject, relative clause marker, subclause verb, subclause object, main verb, main object.

(interpreting "som" as a stand-in for the subject of this kind of relative clause causes more trouble than it's worth)

The third flaw of V2 is it doesn't explain WHY we sometimes flip our sentences into forms like OVS.

== SO WHAT THEN? ==

So I've established that SVO is no good beyond basic sentences, and V2 is better but flawed. It's time I propose what I think is a better solution.

I think Norwegian sentence structure is best analyzed as "TVSO".

The T stands for "topic" and is essentially the main focus of the sentence. It can be the subject, the object, an adverbial phrase, or even the verb. This element is moved to the beginning of the sentence to mark it as the topic.

In most basic sentences, the topic is the subject. The subject moves to the beginning of the sentence and we get the familiar SVO.

Remember in example 2 how the subject moved behind the verb when we put something before it? That's because the subject stopped being the topic and jumped back to its default position. The adverbial phrase became the topic, changing the nuance of what the sentence is about:

Example 1 (SVOA) is about you and what you do (eat breakfast in the morning).

Example 2 (AVSO) is about the morning and what happens then (you eat breakfast).

Example 3 (OVSA) is about breakfast and what is done with it (you eat it in the morning).

In a similar vein, example 4 (OVS) is about the cat and what is done with it. "Katten mater søsteren min" is the kind of sentence someone might say to explain how the cat is going to be handled when they're going away on vacation.

Example 5 (VSO) is what happens when the verb takes the topic role, because the sentence is about the verb and whether it actually happens. Similarly, in example 6 (VO), the sentence is about what needs to be done, and the subject is an implicit "you".

== CONCLUSION ==

Most Norwegian people don't consciously think of this "topic" marking as a feature we have in our language, but it's 100% a thing we do constantly, and in my opinion, recognizing that the default order is VSO (but with the option to pull any element to the front to make it the topic of the sentence) rather than SVO makes Norwegian word order make a whole lot more sense.

I really hope I'm not the only one who thinks that, and that this helped you understand the quirks of the language better. Hopefully I didn't just confuse you further by overcomplicating things.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

@paragonrobits @veryever alright, here we go. Technically-not-swears to give your writing a punch that "oh spirits" does not.

@terulakimban, @mikaslilworld, and @589ish were asking for this too so I'll mention them so that they're sure to see it.

Adjectives:

Misbegotten. Implying that someone is of questionable parentage is generally seen as in poor taste at best or incredibly insulting, vulgar "fighting words" at worst.

Cursed. Implying something or someone has done something deserving of a curse and have all the bad luck and unpleasantness that comes with it. Probably the most mild example here.