A collection of notes, translations, and the occasional gif.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Note

oh and i also meant to ask! now that dragon maid is over, do you think you'll be doing notes for any other shows? your blog is such a benkyou ni naru for me lol

That's the plan! The dragon maid episode 12 notes aren't quite finished yet because Work has been dumping on me, but they should be up next weekend, and after that I'm planning to pick up a new show for this season (and/or work on the backlog of older dragon maid episodes).

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

thank you as always! specifically for episode 11, your explanation for the "どうしてトールがうちに来てくれる気になったのか" line was super interesting, and I didn't even realize it upon first watch. I was thinking about it for a while, and if you stuck a か after the 来てくれる, so "どうしてトールがうちに来てくれるか気になったのか" would this mean it was more kobayashi being curious about tohru's coming to her home vs the line as is, where it's kobayashi being curious about what DROVE tohru to come? or am i totally wrong lol

You are basically correct, yes!

However you'd need to tweak the rest of the sentence a little as well: removing the のか from 気になった (you could put another particle there instead if you wanted, like よ or even a different-use-case の), and making the 来てくれる past tense: どうしてトールがうちに来てくれたか気になった or something like that.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Kobayashi’s Maid Dragon S2 Episode 11 Notes

This is ラジオ体操 radio taisou, lit. radio exercise(s). Basically it’s a short series of light stretches intended for general health. It used to be broadcast over the radio (and I guess still is), but is also on TV and internet these days too.

It’s generally popular as a morning thing to kind of get the blood flowing—some companies (apparently around 1/3rd) even have a few minutes in the morning set aside to have everyone do it. Some neighborhoods will hold outdoor public gatherings during summer break, as a morning routine thing for children while school is out. It’s also a kinda stereotypical old-person thing to do.

There are two “sets,” known as radio taisou dai ichi, and radio taisou dai ni (basically “the first” and “the second”), and each has a standing version and sit-down version for improved accessibility.

“Pound (shoulders)” here is 肩たたき kata-tataki, a type of shoulder massage that involves lightly bopping the recipient’s shoulders with the bottom of your fists. It’s a stereotypical thing for kids to do for parents/grandparents (remember the shoulder massage tickets Kanna gave Kobayashi for Father’s Day in ep 8? same thing).

I honestly have no idea how effective it is.

小林さんは安く済ませようとして、色々物を買ってしまうタイプなんでしょうか?

For clarity here, the idea is less that Kobayashi tries to buy lots of stuff for cheap, but that she wants to solve whatever problem on the cheap, and ends up wasting a bunch of money on several cheapo purchases that don’t really help.

Another angle on it might be like:

“Could she be the type who tries fixing a problem cheaply, but ends up paying more for less?”

Just a bit of trivia, but in the manga Elma answers this question about computer chairs by saying “Yes, a good one costs as much as 1,000 cream buns.”

That’s our Elma.

Takiya’s word for “logic” here is 理屈 rikutsu. Rikutsu does mean “logic,” but it has another use too: referring to something that relies excessively on “theory” vs. practical application/real experience, or a kind of “forced” logic.

Basically here he’s saying this out of modesty, not like “the solution was only logical.”

This “concerning” is 危うい ayaui, an adjective describing something that’s in a perilous situation, kind of like something you’d say “balanced on a razor’s edge” of. It’s typically for less immediately physical types of danger (which would use 危ない abunai instead).

In this case, while it’s true such situations are typically “concerning,” he’s not saying this because he’s concerned per se; he’s saying that situations like Tohru’s, where emotions run high (e.g. romantic relationships), are often fragile because of that strength of emotion.

For “a little hard,” Tohru says グサッと gusa-tto. (“Sharp” was 鋭い surudoi, which is basically one-for-one.)

Gusa-tto is one of those sound effect words mentioned in previous notes, used to describe a heavy stab or pierce (literally or figuratively). (If you’ve seen that anime/manga visual gag where someone says something and the words/speech bubble “stab” the other person, that’s a more light-hearted use of this.)

I mostly bring it up here because the “he’s sharp”→”what he said cut deep” was a good pairing of evocative phrasing that we didn’t really get in the English.

この程度でいいですか? kono teido de ii desu ka? この程度でいいよ。 kono teido de ii yo.

Kobayashi’s answer here is repetition of the question, but changing the “question” marker for a declarative one. Like “Is this enough?” “This is enough.”

I bring it up here for two reasons. One is just because I mentioned the whole repetition thing in a previous episode’s notes, so as an example to help drive that home.

The other is that I have a bit of an issue with the choice of the word “perfect.” Kobayashi is generally a lowkey person (with some exceptions), prone more to understatement than overstatement, so a relatively strong word like perfect is a little out of character for this scene, I would say—especially given the Japanese.

The use of the particle で de in these two lines is also worth noting. In this context (where you’re talking about whether something is what you want), de ii and ga ii have two distinct meanings. With de, it’s “good enough.” With ga, it’s not just enough, it’s actively what you want. If you’ve seen romance shows where one person has low self-esteem, you’ve likely heard a question like “boku de ii?” answered with ”kimi ga ii.”

If there’d been some sort of twist to the phrasing like that, “perfect” might have been a good choice, but as it is I’d have probably stuck with something like “Yeah, this is plenty.” (if maintaining that sentence structure anyway)

そういうもんですか? そういうもんだよ。 分かりました。そうします。

Just one quick note for clarity on this exchange; the “that/this” they’re talking about is the “what Kobayashi wants” topic, not specifically this tail-chair thing or how fast the tail-vibrations are etc. You likely got that anyway, but I figured I’d mention just in case, since the Japanese wording felt more obvious about it.

Notably here Daddy Tohru says 知り合い shiriai, which is very explicitly a level or two removed from “friend.” (it’s often translated as “acquaintance”)

They might actually be friends and he just phrases it that way because tsundere, but either way I don’t know if I’d use “friends” here.

If you’ll recall from the Elma episode, “clairvoyance” there was 千里眼 senrigan. This is actually not that, but instead 未来視 mirai-shi, which is more or less literally “future sight.” It probably won’t really come up again(?), but just as a world-building thing I guess, know that this guy and Elma don’t actually have exactly the same power (at least in this instance).

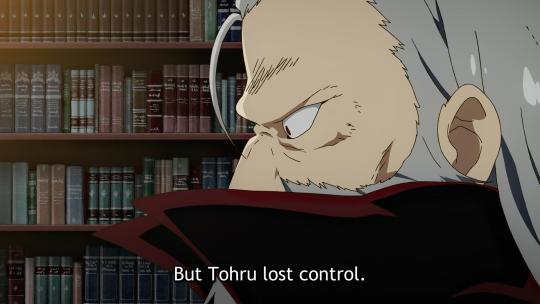

The word for “lost control” here is 暴走した bousou shita, which does basically mean that.

I would, however, like to point out that he’s not necessarily saying Tohru lost control of herself. Bousou means that [whatever] is running wild, but that ranges from a runaway train, to someone going berserk, to someone acting rashly without consulting others.

My point in bringing it up is that “lost control” sounds like Tohru had little/no agency in the decision to storm the enemy’s home ground, which is not really the case and not necessarily implied in the Japanese.

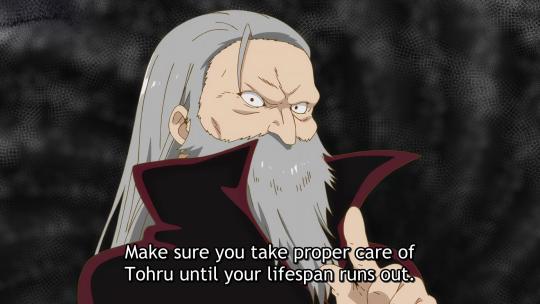

When Kobayashi responds here, she says she, Kobayashi, will be the one getting looked after by Tohru, not the other way around. She flips it 180 degrees from how Dad here says it.

(Since, y’know, Tohru’s the maid and everything.)

Example alt text:

“Make sure you take good care of Tohru until your lifespan runs out.”

“Yessir, I’ll have her take good care of me.”

It’s supposed to give this very heavy and serious scene a bit of levity to end on.

(For the Japanese students: she says [面倒を]見てもらいます, meaning that Kobayashi is having Tohru do the “looking [after].” If she was the one doing the looking after, it would be something like 見させてもらいます instead.

When you stick もらう or いただく after a verb, it’s you having someone else do that verb, not you doing it, so to make it work for “you” being the verb-doer, you have to flip the verb to a passive form. It’s kind of like the difference between “please [verb]” and “please allow me to [verb]”.)

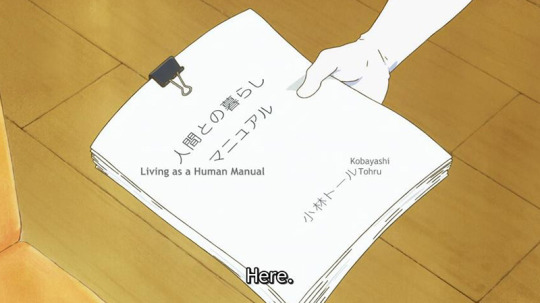

どうしてトールがうちに来てくれる気になったのか

Two small things about this line. First: the “came here” is うちにきてくれる uchi ni kite kureru. The two words I want to mention are uchi, which is like “my/our place” (like “wanna come to my place?”), and kureru, which is used as a helping verb to denote that a verb was done for someone else.

So basically the Japanese adds two extra layers of… emotion(?) to the “came here.” That is, “here” is specified as Kobayashi’s home (vs “here” being more vague and could just mean “this world”), and the “came” is conjugated in a way that expresses Kobayashi sees Tohru’s .

The second, more minor, is that it seems like the English took the 気になった ki ni natta and changed it from talking about Tohru to talking about Kobayashi.

Ki ni naru can mean to take an interest in something (“I’m curious”), or when attached to a verb, can mean “got the will/motivation to do [verb].” In this sentence, it’s attached to the verb phrase uchi ni kite kureru, so meaning more like “why you chose to come here.”

(That said you could easily leave the “curious to hear” part there in the English too though, since that still makes sense for her asking a question like this.)

(Basically the English reads like a translation of どうしてトールがここに来たのか気になった instead of the line in question.)

So like as an example alt:

“I’m curious what moved you to come live with me.”

Which still doesn’t fully grasp that kureru, since that’s a hard thing to just “slip in” in English, but does hit a few other relevant notes and should still be okay length-wise (cursed subtitle restrictions!).

The phrase for “[move] to the big city” here is 上京 joukyou. It combines the characters for “up” and “capital” (of a state/country) and is used as a verb for moving to the capital—these days, specifically Tokyo.

(It used to mean moving to Kyoto, and I’m told it annoys some old-school Kyoto-ites if you use it to say moving from Kyoto to Tokyo, lol.)

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kobayashi’s Maid Dragon S2 Episode 11 one quick note

Just one quick note now—before the full notes write-up—since I just watched the episode and this stuck out as a missed TL:

When Kobayashi responds here, she says she, Kobayashi, will be the one getting looked after by Tohru, not the other way around. She flips it 180 degrees from how Dad here says it.

(Since, y’know, Tohru’s the maid and everything.)

Example alt text:

“Make sure you take good care of Tohru until your lifespan runs out.”

“Yessir, I’ll have her take good care of me.”

It’s supposed to give this very heavy and serious scene a bit of levity to end on.

(For the Japanese students: she says [面倒を]見てもらいます, meaning that Kobayashi is having Tohru do the "looking [after]." If she was the one doing the looking after, it would be something like 見させてもらいます instead.

When you stick もらう or いただく after a verb, it’s you having someone else do that verb, not you doing it, so to make it work for “you” being the verb-doer, you have to flip the verb to a passive form. It’s kind of like the difference between “please [verb]” and “please allow me to [verb]”.)

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kobayashi’s Maid Dragon S2 Episode 10 Notes

I’m extremely not an expert in birds, but I tried to look these up to see if they were a species native to New York (since they’re similar to the sparrows we usually see around Kobayashi’s place). Apparently there are few similar-looking species in New York? My totally uninformed guess is that they may be house sparrows.

The sun sets in Japan relatively early (probably around 6:30pm when this episode takes place), which would make it entirely plausible that if she just flew east (with a slight northward angle) she’d find herself over New York in the early morning while most of the rest of the country is still dark.

These bumpy grey pads at the pedestrian part of the intersection here are known as (among other things) tactile paving; they’re to assist people who can’t fully rely on eyesight to get around.

Interestingly (imo), they were actually invented in Japan in the 60s (by a Miyake Seiichi), where today they’re extremely ubiquitous. They even show up later this episode!

They’re often referred to in Japan as 点字ブロック, tenji (Braille) blocks, and they tend to come in two types: the “dot” design, which indicates a place to stop (or an angle change, or more generally “caution”), and the “line” design which indicates you can safely keep going. They’re generally colored yellow in Japan, ideally making them stand out more to help people with impaired vision find them, and are mandated by law in most places public transport can be found (among others).

Not really a translation note, but “deer cola” felt especially funny in the context of all the horse medicine stuff.

I guess “[animal] [drink]” is a common branding device in-universe, given the crab beer Kobayashi’s always drinking.

Also not really a translation note, but the difference between how “hard” Kanna and Chloe are running to be at the same speed was a nice animation touch.

遊んだ遊んだ! asonda asonda!

One feature of the Japanese language is a very heavy use of repetition. This includes “reduplication,” a linguistic term for creating words by repeating a root (e.g. a “boo-boo” in English or the dara-dara example below in Japanese), but also just like… saying the same word multiple times, as Chloe does here.

Typically this is done for emphasis or to help increase clarity: if you’ve worked in a Japanese office, you’ve likely heard someone in a phone conversation say desu desu in response to someone asking for confirmation.

This acceptance of repetition sort of extends beyond the obvious uses like this as well: for example, personal pronouns are much less common; instead (if the subject isn’t dropped) you’ll often just use the person’s name again. You’ll notice similar trends with other types of words as well.

Not to mention the ubiquity of things like otsukare.

This often ends up being a challenge for translators, because reusing words in English (when it’s not for an obvious reason) tends to stick out rather unflatteringly, even if they aren’t that close together.

(Like when I overuse “hence” in these notes.)

This “Christ” in the Japanese was “ったく” (short for 全く mattaku, but just used as a semi-generic exclamation). I mostly bring this up because it’s a good example of a word that doesn’t work out of its cultural context; e.g. it wouldn’t make any sense for a fantasy character to say “Christ,” but since this is an American speaker it works just fine (and helps distinguish that fact, even).

I think I’ve mentioned this before, but English uses a lot of “explicit reference” words like this, that can break immersion if put in the mouths of characters who wouldn’t have exposure to said reference—which can be annoyingly limiting when trying to write dialogue sometimes.

As a bit of a culture shock for a lot of Americans I’ve met, most Japanese homes tend to have wall mounted air conditioning units, like this one, that are only for heating/cooling the one room they’re in. (Many also have a “Dry” setting that makes them act kind of like a dehumidifier as well.) It’s common to not have them in every room, like bedrooms, however.

This is in contrast to the central air conditioning system used by a majority of homes in the US (though type/use of AC in the US varies a lot by region; less common in the north for example)—and places like the UK where apparently residential AC units of any kind are quite rare.

You may have noticed that the doors between rooms always seem closed in Kobayashi’s apartment. That’s not just to make the backgrounds simpler, it’s also a good habit to keep if you’re going to be running the AC!

“Kobayashi, are you お休み today?”

“Yeah, お休み.”

お休み o-yasumi, is a noun form of the 休む yasumu, to rest. The word has a variety of applications, as we see here. A day off work/school, i.e. a rest day? お休み. Want to say “good night” to someone before bed? Also お休み.

In this case, it’s not even necessarily clear it’s being said as a pun; as mentioned earlier, repetition is a common feature of the language, so despite the yawn there wouldn’t really be any reason for Kanna to think Kobayashi was about to go to nap or anything.

“Laze about” here is だらだら dara-dara, another phenomime (擬態語 gitaigo in Japanese)—one of those words that mimics the “sound” of an idea/concept/state, which don’t actually make a sound per se.

These phrases aren’t necessarily childish or anything (overuse of them can be, but you can find them even in news articles and political speeches for example). They are, however, used frequently by children, and by adults talking to children, as they’re very “easy” words: they’re expressive, they capture useful daily-life concepts, and they usually roll off the tongue. You’ll notice, for example, that Kanna uses them a lot.

Kanna has a very interesting way of talking actually, which I’ll touch on a bit more later.

Kobayashi’s “bean jam” here is あんみつ anmitsu, a traditional Japanese dessert (technically a spinoff of mitsumame). It typically is a mix of red beans (and/or red peas), agar (an algae-based gelatin equivalent), some fruit, some variety of rice flour product (shiratama in this case, similar to mochi), and a syrup (often black sugar based).

You can find it year-round, but it has a strong summer association and is even used as a summer season word. (It’s typically chilled and you can often get it with ice cream as an ingredient.)

It’s also sometimes paired with a green-tea flavored something as well (e.g. ice cream, agar, or syrup). The trinity of green tea, red beans (aka azuki), and shiratama makes what I like to think of as the “Japanese S’mores Flavor (for Adults)”. No I will not elaborate on this.

I will though point out the shaved ice flavor Kobayashi ordered later in the episode:

え?今スイカ様子あった?

A word of note here for language learners is 様子 yousu, which has a lot of definitions, but in cases like this where it’s attached to a noun or phrase means roughly “the appearance of __” or “an indication of ___” etc. In actual use, it typically means something that makes you think of whatever ___ is—or the lack of something that would make you think ___.

For example here, it’s like “Watermelon? Where’d that come from?” (since the TV was talking about a different dessert-y food entirely).

Or an unrelated example: “I think that guy is hiding something” → “Really? I haven’t seen any yousu of that.” In other words, it can be a lot like “sign,” as in “I’ve seen no sign of ___.”

These color-bordered envelopes (originally colored based on the flag of the country of origin) used to be the standard for air mail, domestic or international, though they haven’t been required for several decades.

That said, they’re still popular for that “ooh, international mail!” feel (at least in Japan) and you can buy them at most places that sell stuff like envelopes. As here, they’re often used in media to immediately convey that a letter came from outside Japan.

Kanna (and Kobayashi) says エアメール, lit. “air mail” in English, which is used colloquially for international mail specifically, rather than “mail sent by plane.”

They’re having what’s called 冷やしそうめん hiyashi soumen, chilled/cold soumen for lunch here. (Soumen being a thin wheat noodle; udon but thinner.) As Kanna says, it’s very easy to make!

Basically you just boil it, wash it in cold water, add ice, get some sort of sauce to dip it in, and you’re done! It’s a popular quick meal in summer, and much easier than the more involved nagashi soumen setups you may have seen elsewhere, where they slide the noodles down a chute for you to try to grab and eat. (It’s basically the same meal aside from that though.)

(You can of course add more to it, but as we see here, you don’t really have to.)

The type of tea here, for the curious, is 麦茶 mugicha, barley tea. Mugi is the general name for cereals/grains including wheat (komugi), barley (oomugi), rye (kuromugi or rye mugi), and oats (enbaku or oat mugi). It’s incredibly common in Japan (and much of East Asia), where it's the household summer drink.

It has no caffeine like many other teas, and has a bunch of various nutritional benefits, so it’s considered a good way to stay hydrated as you’re sweating buckets in the muggy Japanese summer weather.

帽子した? boushi shita? した! shita!

I thought this was a cute way of phrasing this question/answer, and a good example of the “parent and their young child” way these two talk.

The suru (past tense shita) verb used here is the ultimate in “generic verb,” and it basically doesn’t get any simpler grammar-wise to phrase something as “noun+suru” like Kobayashi does here (even the particles are dropped).

Kanna, for her part, doesn’t respond with a “yes” or etc, but instead just repeats back the verb itself in confirmation.

Just to note another one of those words like dara-dara: bura-bura, used for things like wandering around, doing something (or nothing) casually/aimlessly, or (with one bura) for something dangling/swinging in a more literal sense, like a spider, slack yo-yo, or wind chime.

These booklets are a common homework assignment for practicing kanji; you can see along the left side there it shows the stroke order, with the first block giving an example to trace over & showing where to start each stroke.

Each character is made up of radicals (e.g. “hot” above: 日 and 耂), which each have a standard way to write them. There’s 214 such radicals (though many are pretty niche; only about ~50 of them are needed to make most characters), and once you get a hang of them it makes learning new characters much easier (not too different from learning word spellings in English imo).

Kanna is repeating out loud the reading for the “hot” character as she writes it.

In addition to the above workbooks (which usually involve both kanji and math problems at Kanna’s grade), elementary school summer homework in Japan typically involves doing an illustrated diary (not a daily one necessarily) and some sort of research project about a subject of your choice. (Think kind of like a small science fair project).

The “research” project part is pretty expansive, and you can typically even do something more arts & craftsy for it.

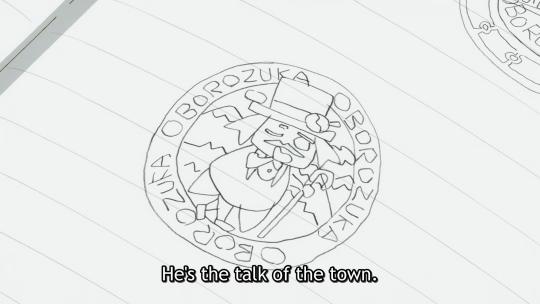

Manhole covers in a lot of Japanese municipalities feature art representative of the area. For example, the city of Chofu, where the author of GeGeGe no Kitaro lived most of his life, has several with art of that series.

(Photo from https://www.gotokyo.org/jp/spot/1734/index.html)

I mentioned earlier that Kanna has an interesting way of speaking. Probably a better way to put it is that she has a pretty convincingly childish way of speaking (despite the monotone). That is, she uses simple grammar and “easy” words most of the time, but then throws out random big words and fancy idioms from time to time that make you go “...where did you learn that?”

In this case, the phrase she uses is 巷で人気 chimata de ninki. Chimata originally means like a fork (in the road), and since those are often places with lots of people passing through, it expanded to mean “the undefined place where people talk about ~stuff~.” So it’s used for “many people are saying~” or “word on the street is~” types of situations (or “talk of the town,” as here).

It’s kind of an “adult” word though; for example the character for it isn’t included in the jouyou kanji (the 2000+ that are taught in elementary through high school). Hence Kobayashi’s reaction here.

The word she uses for “protected” here is 死守 shishu. The word is the combination of the characters for “death” and “protect,” ~meaning to protect something even at risk to one’s life (to the death, as it were).

It's a word that you learn in third grade in the Japanese education system—the same grade Kanna is in!

Both of these types of signs are common sights in residential areas like this: depending on where you live, it can feel like there’s always some sort of construction project going on, and Japan’s many family/individually-owned businesses like this tend to be closed on various extra days during the summer (and certain other times) to allow for time off.

In this case, them being closed August 12th~16th implies they’re taking off for Obon (and probably leaving town to visit family).

The word Kobayashi uses here is 風物詩 fuubutsu-shi. Fuubutsu refers to something that makes up part of the “scenery” of a place or season, in a pretty broad sense. This shi typically means “poem.”

So fuubutsu-shi is originally a type of poem celebrating a season or a scene of natural beauty, that sort of thing. From that, it’s also now (more popularly) used to describe things that are representative of a season; the kind of stuff you say “it’s not winter until…” about, or “you know it’s summer when…” (It can also be used for places + seasons, like the ice sculptures of Hokkaido winters, or even summer Comiket in Tokyo.)

They’re very similar to the season words I’ve mentioned previously, though they’re far less strict about what counts as one. Here, Kobayashi’s could be referring to the whole package experience of “having to take cover and wait out a sudden heavy rain, despite it being mostly clear skies a few minutes ago,” which you could call fuubutsu-shi (summed up probably as like 夏の雨宿り etc.)

In contrast the relevant season word here would probably be yuudachi (or niwaka-ame), a word referring to the short, sudden bouts of rain that tend to fall (from cumulonimbus clouds, the makings of which are noticeable in the backgrounds before this) on summer evenings.

Feels like in season one she woulda eaten it. Three cheers for character growth!

The parentheticals there are just the “English” in hiragana/katakana.

Kobayashi’s comment (nihongo de ok, roughly “you can just use Japanese”) is an internet-born term people originally would use to reply to someone who said something that didn’t make any sense, had terrible grammar, or was so full of katakana loanwords it was hard to read etc.

Kanna says this line in English, and while I have no proof at all, my guess is that the specific choice of “wicked” was taken from the translation of “maji yabakune?” used in season one.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kobayashi’s Maid Dragon S2 Episode 9 Notes

...設立から大分地盤が固まってきており、少しずつだが、業態は改善されている。

One thing to note here is that Kobayashi(‘s narration) isn’t saying the company has already made solid improvements, it’s that the company has finally established itself somewhat (as it was only founded relatively recently, and typically new companies are especially busy while trying to get off the ground) and now is starting to make improvements.

Similarly in the second sentence, it’s not “was” slow going, it’s “is still” slow going, and the working conditions “are” improving, not “have improved.”

This is がんば ganba, short of course for がんばって ganbatte, which I’m sure most of you are familiar with: the (in)famous “do your best.”

I only mention it because I like this shortened version of it. Ganba!

This is a fun little idiom(?)/saying: 鼻で笑う hana de warau (conjugated as hana de warawareta), lit. to laugh using the nose. It’s used to describe laughing at someone you’re looking down on for whatever reason (not necessarily in a super serious way, could just be a friend being dumb etc.; in this case it’s Elma’s being naive).

Typically it refers to like a “heh-but-through-the-nose” kind of “laugh,” but as you can see in this scene (where clearly Kobayashi is laughing with the mouth, even starting with “pff” lips) it works idiomatically even if the laughing isn’t only through the nose.

You may have heard that Japan is/was a “lifetime employment” country, where typically people would get hired right out of school and stay at that company until retirement. While that’s much less true today than it was even a couple of decades ago (and has become kind of controversial in ways), it’s still much more common of a practice than in say the US.

One result of this is that there’s a much bigger distinction placed between hiring people in spring as part of the annual graduation rush (the Japanese school year ends in March), and mid-career hiring. Typically you can’t participate in the fresh grad hiring if you aren’t one, even if you’re new to the field in question.

For larger employers (i.e. 5k+ employees), roughly two-thirds of all hirings come from fresh grads, and only small employers (<300 employees) hire more mid-careerists than people directly out of school.

Of course, this split tends to apply mostly to “standard” full time jobs, not so much part time, and is not necessarily a thing in every industry/at every company.

Just as a minor point of clarity, this “organized text” in Elma’s document refers to the phrase まとめられた文章 matomerareta bunshou. In a literal sense, matomerareta can mean organized/consolidated etc., and bunshou text/passages, but meaning-wise it’s more like “writing that gets its point across clearly/cleanly.”

This is a pretty big compliment and a very useful skill to have in organizations like this, as writing such that people can quickly and easily understand exactly what you’re trying to say often saves a ton of time and frustration.

我々はエルマの気迫に押されるがままにその書類を読み始めた。

Another minor point, but where the English could imply that they were overwhelmed by Elma’s intensity through the act of reading her report, the Japanese implies more that they started reading it because of how intense Elma was being.

It doesn’t really make much of a difference either way, but it stuck out a little for me.

To justify mentioning it, I guess I’ll explain the grammar point Kobayashi uses: されるがままに sareru ga mama ni. Sareru is a generic verb/verb conjugation for having something done to you (technically here it’s 押される, to be “pushed/pressed/pressured”), and mama refers to a state, condition, or “way” (like “do it this way”).

Put together, the whole phrase is used to indicate “you” do/did something that someone else wants you to, without (meaningful) opposition. (Something similar in raw meaning but with a very different connotation would be “going with the flow.”)

If a friend says “hey let’s go do something,” and next thing you know you’re out bowling despite preferring to stay at home, this is you.

You can stick the mama ni to various other things as well to come up with a similar idea, but without the sareru the nuance may end up different.

The word for clairvoyance here is 千里眼 senrigan, lit. “eye(s) [that can see] a thousand li”, li being a Chinese unit of measurement for length (shorter than a mile, but for general purposes “eyes that see a thousand miles” is basically the gist).

Despite the perhaps physical-sounding nature of the term, it does actually describe the same power as “clairvoyance” in English: being able to perceive things outside your actual range of vision, including potentially into people’s hearts and minds etc.

Hence why it’s a thousand screen display, when she updates it with tech knowledge:

“Tainted by work” here is 職業病 shokugyou-byou, lit. an occupational disease. The “proper” definition is a disease one gets from working in a particular job, such as black lung for coal miners or even posture-related health issues for desk workers.

Additionally, it’s used colloquially to refer to noticeable habits or quirks that people in a certain profession pick up, like a baker always waking up super early or a programmer using programming lingo out of context in normal conversation. The latter being especially noticeable in Japanese, as a lot of such terms are English in origin.

“Shocking” here is a fun word: ドン引き don-biki. “Don” here is added just for emphasis; the main meaning revolves around 引き hiki/biki, from the verb 引く hiku, meaning to pull.

The idea is that someone does/says something that you recoil from. Maybe it’s gross (“I only shower once a week”), maybe it’s mean (“They didn’t smile enough so I didn’t leave a tip.”), maybe it’s creepy (“I sent like 30 texts yesterday but still no reply.”), just anything that has you feeling like you might want to create some distance because... phew.

It’s kind of similar to the current use of “cringe” as an adjective/noun, though with less of an internet-slang feel* to it, and generally used more as something the speaker is doing rather than describing whatever/whoever is being cringe.

(*I think it started being used popularly in this way in the early-to-mid 90s, with the “don”biki variant specifically popping up around 2005.)

A “Premium Friday” is the last Friday of the month, where you get to leave work at 3 pm. It is largely theoretical.

The idea was created by the Japanese government as a way to reduce working hours and encourage domestic spending (boost demand), but it has not been implemented by all that many employers, and especially not many smaller employers. There isn’t, after all, any mandate or government-provided incentive for doing so.

Evidence from the places that did implement it suggests it is actually good for the economy, but good luck convincing bosses to give extra paid time off.

“Last Friday of the month” was chosen because most people get paid on the 25th each month (Japan tends to pay monthly instead of every two weeks), so it would usually be right after payday, when people are more willing to get spendy.

Kobayashi saying eight hours here reminded me of a “fun” fact: the typical Japanese work day is eight hours plus a one hour break. Plus a one hour break, not with. So a typical work day is actually nine hours. Most commonly 8 to 5 or 9 to 6. Not many “nine-to-fives” here.

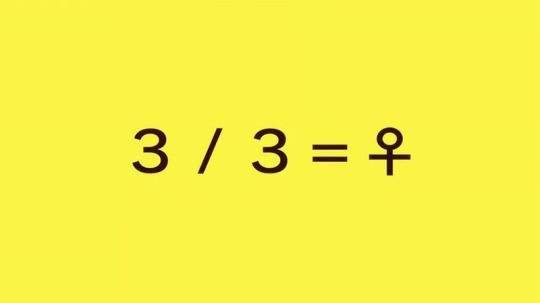

The characters for Joui are 上井, which usually read as Kamii or Uwai. It’s “Joui” because that means, when written as 上位, “superior.” As in “a superior life-form.” Like a dragon, say.

でも、ゆっくりやる事業改善案を見せてもらえたじゃない?

This one is actually kind of a critical mistake. In the English it sounds like she’s talking about the improvement proposal that Elma made and that the boss looked at. In the Japanese though, she’s talking about a different plan, one the boss showed them*, that is similar in idea but is going to take longer to be fully implemented**. So we’re being told that while Elma didn’t get what she wanted as fast as she wanted it, it is still basically going through at a slower pace.

*In ”見せてもらえた misete moraeta,” the misete vs mite means they were the ones who got shown something, rather than the ones who got someone to look at their stuff.

**Which you can tell from the ゆっくりやる yukkuri yaru, where yaru is basically “do” and yukkuri means (in this case) at an unhurried pace.

(Re previous note: Hence why she says “immediately” here.)

“Black (ブラック)” and “white (ホワイト)” in the context of Japanese employers refers to how well employees are treated: a company with good benefits/pay, reasonable levels of overtime, and feels safe to work at is “white,” while a company that has excessive overtime, often pays poorly, breaks labor laws, and allows harassment to fester is “black.”

While “white company” was created simply in contrast to the term “black company,” the latter finds its origins in front businesses for organized crime, which were called “black” in the sense of “illegal” (similar to “black market” or something being in a “grey area”). Given the international reputation of Japanese work life, you can imagine that “black company” as a term sees much more use.

There’s been some discussion about maybe replacing it due to the racial implications (especially since it uses the English word “black”), but while typically English translations drop the color for that reason (e.g. ブラック企業大賞, an “award” given to Japan’s worst employer each year, is officially “Most Evil Corporation of the Year Award” in English), it hasn’t really penetrated to the mainstream at this point.

The rice there is in a 飯盒 hangou, a metal container that looks… like that, and is the stereotypical item of choice for cooking rice while camping. It has its origins in the mess kits used by the military, but these days they’re primarily marketed as portable rice cookers for camping use.

You can get round ones too, but the bean shape is very popular.

“Settings” here is 設定 settei, lit. exactly that, “setting(s).” E.g. if you open a computer program and look at the settings menu, it’ll be settei in the Japanese language settings (settei).

I bring it up here because there’s a bit of a difference in how it gets used colloquially like this. In English, the “setting” for a story typically refers to where and when it’s set. In Japanese, “setting” in that sense is usually 舞台 butai. But settei is still used when talking about fiction, just in a different, more expansive way.

Often in these cases settei is used to refer to the various conceits that provide the context in which the story takes place. In this show, for example, one such “setting” is that dragons are real: another is that magic exists. It comes up especially often in fantasy/sci-fi type stuff where there are major distinctions between that universe and the real world—not that stories in a real-world setting don’t have settei of their own, but they often are lumped into descriptions of the plot in that case (”a dragon comes to live with an office worker in her apartment”).

It also refers to the “settings” of characters, like name or age, and things like “they run a bakery that’s going out of business and are trying to save it.” Basically all the details you’d have in a character profile.

It also gets used in conversation to refer to pretend things or (basically) lies: like here, where Saikawa thinks Shouta is playing pretend with his ley-lines talk, or e.g. if someone is trying to tell you some outlandish story (“my uncle works at Nintendo…” or someone asking for love life advice for “their friend”) and you’re just like “Okay so that’s the settei here, I see.”

Not really a big deal, but Elma’s line here in Japanese implies she won’t let Tohru call her that anymore (see her もう mou). Tohru’s response is also more of a “I haven’t been?”, since of course she wasn’t aware of Elma’s-mental-image-Tohru tormenting Elma in the previous scene:

The word for “full of” in the title here is ざんまい zanmai (a suffix form of 三昧 sanmai), usually meaning that there’s a whole lot of [whatever] to immerse oneself in. I mostly bring it up because there’s a famous restaurant chain called Sushi Zanmai that specializes in, obviously, sushi.

And you know, Elma is a water dragon that looks kinda like an eel… I’m just sayin’…

Not really a translation note, but wild that Elma didn’t even touch her parfait. (Not so wild that Fafnir finished his so quickly.) Serious business ahead...

“Genuinely” here is 素直に sunao ni, where the “ni” is used like “-ly” to make sunao work as an adverb. Sunao itself is an interesting word that falls into that category of “simple concept that is often hellish to translate.”

For some context, the first character, 素, is also used in the word 素顔 sugao, which is a face without makeup and 素材 sozai, basically raw ingredients/materials. The second, 直, is used in words like 直線 chokusen, a straight line, or 正直 shoujiki, honest.

Put them together, and you’ve got a word with connotations of directness and being unadorned. The original definition of the word tends toward “simple, natural” in the sense of e.g. life growing up on a rural farm.

The more common use for it these days is to describe people and their actions. Positively, it can mean something similar to a person being happy to help, or kind of like the opposite of conniving; open, frank, genuine. Less positively, it can mean someone is too trusting and easy to trick into doing things OR someone who is “too honest” and says hurtful things.

(If it helps: tsundere characters are often described as explicitly not sunao.)

In this case, the idea is that Tohru accepted the invitation easily as-is, without putting any conditions on it, or doing any “ugh, what a pain, do I have to, jeez” rigamarole—she just accepted. Another way you could put it in this case might be “It’s even more unusual for Tohru to accept an invitation like this without a fuss.”

Just to point out the hand on head thing again.

Also just to point out that this is another example of otsukare, as a reminder of how ubiquitous that word is.

And it makes a good place to end on: thanks for reading!

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kobayashi’s Maid Dragon S2 Episode 5 Notes

Better late than never! Hopefully I’ll catch up with these before next week’s episode hits.

私は、種族全体の目的よりも自分がやりたいことをやっているエルマに、興味がありました。

当時の私、そんな感じでしたし。

What Tohru is saying in these shots is a little different in the Japanese:

“I had an interest in Elma, who was doing what she wanted to do instead of advancing the goals of the species [her faction]. Since that’s how I was at the time, too.”

That is, for the first sentence, Tohru is saying Elma wasn’t interested in the broader dragon goals, not Tohru herself.

Then in the second sentence, instead of a wishy washy “I think that’s how it was?” Tohru says that she was like that too, hence her interest.

So it goes from like:

“I was interested more in Elma than in faction goals, because she was acting freely. I think, anyway.”

to more of a:

“I was interested in Elma because she was acting freely, not bound by faction goals. That’s what I was like too, after all.”

Not sure if it really counts as a translation note, but since I had some questions about it, here’s a few words on the Tohru/Elma disagreement scene.

Tohru thought Elma was like herself: acting not according to what dragon (or human) society asked of them, but according to their own personal set of values. Elma, by allowing herself to be placed in the position of “god” by the humans, had changed that; she locked herself into permanently being a (large, important) cog in the human society. From Tohru’s perspective, she’d lost the one person she felt kindred with, her fellow “free actor.” She doesn’t particularly care what happens to the humans, hence the 私が言いたいことはそういう話ではない (“That’s not what I’m trying to talk about”) when Elma says she’ll just stop the wars from happening: that’s all well and good, but it doesn’t solve Tohru’s issue.

Hence Kobayashi’s response: both grand (involved the fate of nations), and petty (Elma got “trapped” by food, and Tohru’s initiation of the fight was for personal reasons).

喧嘩するほど仲がいい kenka suru hodo, naka ga ii

This is one of those sayings that is often a giant pain in the butt to translate, because it’s not an odd concept in English, but for whatever reason* there is no common pithy saying for it like there is in Japanese, so it’ll almost come off less smoothly.

The idea is that, in order to “have a fight” with someone, you have to already have an established relationship that’s at a certain level of closeness.

Two strangers? Why would you even have a reason to fight, who cares. Two acquaintances? Why deal with it, just smile and nod and go on with your day. Two close friends though? You probably care enough to want to convince them of whatever it is, and/or you don’t want to have to hide your real thoughts/feelings around them like you might around, say, just random coworkers or something—meaning more chances for friction.

*My theory on this is that it comes from the same place as the “wow Japanese people are so polite” stereotype and stuff like honne/tatemae as discussed in a previous episode’s notes: in a situation where two strangers/acquaintances might get into a shouting match in the US, in Japan there’s a comparatively higher chance they just tatemae it up to prevent direct conflict and end the situation early—hence less likely to “have a fight” per se. As always this stuff is just on a continuum though.

What do you call these “clouds” left by planes as they fly? In Japanese, they’re called 飛行機雲 hikoukigumo, lit. “airplane clouds.” And they’re not a season word!

Officially, anyway.

However, they are heavily associated with summer, to the point where you if you google around to find out if they are a haiku season word, there are a whole bunch of sites to tell you no, they’re not, stop asking. That doesn’t mean they’re not a great way to tell the audience it’s summer anyway, though!

If you’re curious as to why the summer association: how long vapor trails like this remain visible depends heavily on how humid the air is. More humidity, longer trails. And Japan has very humid summers (and very dry winters!).

If you’ve heard the song Tori no Uta, the OP to Air (also animated by Kyoani), hikoukigumo is the very second word in the lyrics—no coincidence given the heavy summer theming! If you haven’t heard it, I suggest giving it a try.

“Candy shop” here is 駄菓子屋 dagashi-ya, which is a kind of store that specializes in very cheap varieties of “candy” (maybe more accurately snack foods?): dagashi. If you’re seen/read any of the series Dagashi Kashi, you’re familiar with this variety of snack.

Dagashi is so called because, back in the Edo period, quality white sugar was super expensive and not something commoners could typically eat. Cheaper brown sugar was, though, so you ended up with different terms for stuff made from each: the expensive 上菓子 jougashi and the cheap 駄菓子 dagashi.

Later, in the Showa period after WW2 when the average person was able to afford a bit more, the term stuck around but more generalized, referring to a wide variety of cheap snacks. These snacks are not necessarily always sugary, and they often have some sort of gimmick so it wasn’t “just” a piece of candy—toys attached, or games/puzzles, or requiring some interesting way to eat/drink them. If you grew up with Dunkaroos: that kinda thing.

Similar to “penny candy,” dagashi was/is cheap enough for children to afford several different varieties of with just a bit of change from their parents, and small stores specializing in them—dagashi-ya—sprung up all over the country, quickly becoming a popular spot for kids… and, not too long after, a symbol of childhood nostalgia.

They’ve been on a big downtrend in the last few decades however. The spread of convenience stores as a competitor for snack buying is often cited as one reason, while a greater variety of ways for kids to spend their playtime now (video games etc.) is another.

You’re probably aware, but of the many reasons to bow in Japan, to show humility when making a request is a big one.

Of note here is that Tohru doesn’t push Ilulu’s head down, which other characters in other shows might have done here, but just lightly reminds her: yeah okay you’re a dragon talking to a human, but you’re the one asking—act like it. She does, and her sincerity is rewarded.

The word here is ぱねぇ panee, which is a heavily abbreviated form of 半端(では/じゃ)ない hanpa nai, ~lit. “not halfway/half-done/half-assed.”

hanpa ja nai→hanpa nai→hanpa nee→panee

It’s used probably how you’d expect: describing something intense af.

(I’m mostly just bringing it up because I love super-shortened slang like this!)

The phrase for “like” here is 気に入った ki ni itta, which is basically to have an interest in something/someone, to take a liking to, to say something is a favorite, etc. When said of another person, there’s typically an air of the speaker considering themselves in a higher position. It generally isn’t “like” in a romantic sense.

Take’s “hey that’s my line,” comes from the fact he’s (in his mind) in the position of power and was judging her on whether he’d try to kick her out of the job. You can tell he was thinking of it as “I like the cut of your jib. I guess you can stay.” kind of thing.

Normally a new employee would not say this about their new boss/job, even if they did like it, though a boss/senpai could of a new employee, hence the “what?”

Notably, Ilulu used “like” earlier in the episode to refer to Tohru as well. In that case it was 好き suki, which is a more literal “like,” with the various implications that may or may not have. Personally, it strikes me as a little odd to translate them both as “like” in the same episode.

And that’s it for episode five! I’m

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kobayashi’s Maid Dragon S2 Episode 4 Notes

This week’s episode notes are a little short due to me being super busy. (Maybe shorter is better on these things anyway though?)

This does get explained somewhat, later in the episode, but here’s some more. Takiya is calling Kobayashi a 柱 hashira, lit. “pillar,” meaning what you’d probably expect: she’s a metaphorical “pillar” holding up/supporting the company.

The word is also used in the term 人柱 hitobashira, lit. “human pillar,” which refers to actual human sacrifices. The specific origin comes from people who were prematurely buried/drowned as sacrifices in the building of things like castles or other major construction efforts.

The meaning of 柱 here, though, is not the same as “pillar” per se: “hashira” is also a “counter” word used to refer to gods (so instead of saying “二人, two people, you’d say 二柱, two gods”). The idea was that the sacrifice became sort of deified and would strengthen/protect the building. This isn’t exactly the same practice as offering human sacrifices to gods (or dragons) for things like a good crop harvest during a famine/drought/etc., but obviously it’s pretty close. In general these days, hitobashira can be used to refer to any sort of human sacrifice (including less serious uses, like someone going first in a videogame to test something for everyone else at some risk to their account, etc.)

Unrelated to Maid Dragon, but if you’re into Kimetsu/Demon Slayer: I would imagine the author was uh, not unaware of this connotation when choosing the name “pillar” in that series.

This is a pretty famous story, so you likely have heard it before, but this refers to Aesop’s fable of the North Wind and the Sun. The two entities make a bet as to which can get a traveler to remove their cloak; the North Wind tries to blow it off them, but fails as the traveler only wraps themself in it tighter, while the Sun succeeds by warming the traveler enough that the cloak becomes unnecessary.

The usual moral being that persuasion can achieve what threats and force cannot.

I’m not 100% sure if the blue/orange coloring is supposed to suggest Tohru = Sun and thus was the winner, or if the actual sun up in the top left is there to deny that and suggest neither won (because lol dragons using persuasion on a human).

And here we have an example of some people musaboru-ing some damin, if you recall that phrase from the last episode notes.

The word for gaze/resting face here is 目付き metsuki, a combination of the words for “eye(s)” and tsuku, a word with a million definitions, but for now let’s just say means “to attach.”

I like to think of it as “the way your ‘eyes’ are attached to your face,” hence the kind of look you have, but more accurately it’s the way your eyes look when you’re looking at something (i.e. the way you “attach” your eyes to something).

As you might guess, the fact that it’s specifically referring to eyes means it’s most commonly used in situations where the rest of the face is in a relatively neutral position. Given that, it may make sense that it’s one of those terms that is technically neutral, but is most commonly used together with more sorta negative-sounding adjectives. For example, 目つきが悪い (“having a nasty/scary look”) is extremely common, and is what they’re saying of Kobayashi here. 鋭い目つき (“a sharp/piercing look,” e.g. with narrowed eyes) is another main one.

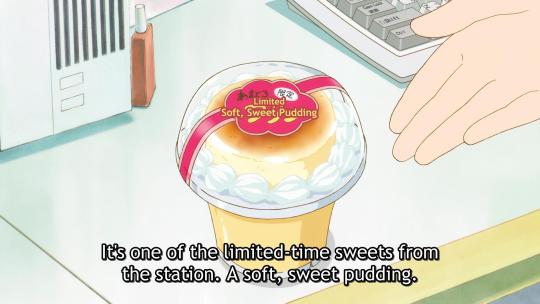

Ahh, “limited” products. Things like this are a super popular marketing technique in Japan, to the point that “日本人は限定に弱い” (“Japanese people are weak to ‘limited’ things”) is basically a meme in Japan itself. There’s endless articles you can read (if you can read Japanese) about “Why do Japanese people fall for ‘limited’ marketing schemes so much?”

I don’t know if people in Japan are actually weak to that form of marketing especially—probably not really—but it’s certainly a thing people think. Maybe it has something to do with Japan traditionally having a very high savings rate, and “limited-time” being an effective marketing tool when people are otherwise feeling frugal? Who knows.

Anyway, there’s multiple flavors of “limited,” of course. Sometimes it’s like “limited edition” runs of something, like a game. Other times it’s “seasonally limited,” like Kit-Kat flavors or restaurant menu items (check out menus during strawberry season). Yet others, it’s like how a bakery will only make 5 or 10 of a certain popular item per day, and you have to rush to try to buy one before they sell out.

Continuing from the earlier hitobashira note.

Kobayashi says this, that there are no hitobashira in modern Japan, but anyone who has heard the term 過労死 karoshi, death by overwork, knows that’s not exactly true.

(It’s worth noting that since the widespread popularization of the term karoshi, there have been a number of reforms toward reducing working hours. To some extent they’ve been successful, but not that successful; much of the reduction in official working hours data comes from the spread of precarious temporary employment contracts that have people working fewer hours for fewer benefits, while typical salaried employees keep working long hours. Similar to the problem in the US I think, actually.)

So why does Kobayashi say this? Well, we’ll see if they touch on this issue again later in the season (there’s reason to believe they might), but for now it may be that it’s representing Kobayashi’s view—rather than the show’s—as one of those people who works way too much, but has unfortunately come to accept it as normal.

The typical word for people like that is 社蓄 shachiku, a play on the word for “domesticated farm animal” (家畜 kachiku)—a “domesticated society animal” you might say—that refers to people who work long, hard hours (typically for not enough pay), but also have no will to try to improve that situation (and may not even consider it a bad thing).

It’s a very glaring gap (even looking at the Japanese comments for this scene on niconico, there was a wave of “uhhhh wrong”), so I have a feeling it will come up again. But who knows!

Just because I love this word so much:

The word Kobayashi uses here for “standing by” is the verb スタンバる sutanbaru. It literally comes from the word “standby” in English, but “verbed” by replacing the final sound with the Japanese verb ending -ru (which can then be conjugated, as in this line). So:

Standby→Standbai→Stanbaru

Beautiful.

Collab cafes are, as is perhaps obvious, themed restaurants set up in collaboration with some media franchise. They’ll have stuff like character-themed menu items, merch, and often randomized-art drink coasters, as we see here. Gotta keep buying drinks til you get the one you want/all of em! (or trade with other people, that’s big too)

Typically these collabs are short-lived, capitalizing on the popularity of something when it’s at a peak (such as during/after an anime run), though some major franchises have permanent ones, like the Gundam Cafe in Akihabara.

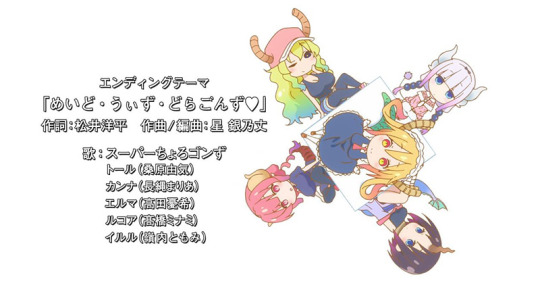

Maid Dragon itself ran one itself last month (July 2021) with Sweets Paradise, a popular cake buffet chain (yes, a restaurant based around all-you-can-eat cake). Here’s the menu from it:

Also note that the maid in that scene is voiced by Georgie’s VA.

Just as a little note, the word for “casual clothes” here is 私服 shifuku, made of the characters for “personal/private/me” and “clothes.” Shifuku are basically casual clothes, but they’re more specifically in contrast to uniforms, than formal/casual per se.

Sort of the idea is that, unlike a uniform, it’s something that you (or a parent/partner perhaps) picked out for yourself, and thus is more personalized. A lot of romance-focused shows, especially ones set in a middle/high school or a workplace, will have scenes where the characters first get to see each other's “personal clothes” and ooh/aah about it.

Just for clarity, yes the Japanese is also “forehead” flick, despite it not being on the forehead at all. (デコピン dekopin, where deko is forehead and pin is an onomatopoeic word)

That said there’s not really a colloquial word for “flick” that isn’t on the forehead, so it sometimes does get used for other body parts (not that that stops people from laughing about it not being “deko”pin).

I don’t know if these background signs will ever be relevant, but just so you know what they say:

-Yellow and red: “Honeymoon (/Newly-Wed) Vacation” (presumably that storefront is a travel agency)

-Top poster on right: “Female Vocalist” (either a band looking for a woman singer, or the inverse)

-Bottom poster on right: “Band Looking for Members”

Here Elma is buying ooban-yaki, also known as Imagawayaki and a million other local names, a flour-based confection filled with red bean paste or various other flavors (this place has red bean, chocolate, custard, and green tea).

It’s similar to taiyaki, the fish-shaped version of this that shows up in a bunch of anime. The “ooban” (大判) comes from a type of (now-defunct) coin that it sort of resembles shape-wise, not unlike how “tai” is the name of the fish taiyaki are shaped like.

Traffic lights in Japan tend to be “green,” but are often referred to with the word that would usually be translated as blue (青 ao).

Referring to green/blue as the same color (especially in certain situations) is a common feature of many languages/cultures (there’s a big wikipedia article on it), and this is one instance of that still being the case in Japan, even as blue/green have become much more linguistically distinct over the years.

Anecdotally, I’ve heard stories from several Japanese people that moved to the US for a while, about how they didn’t know about this and called the “go” traffic light “blue” in English, confusing the heck outta the locals.

When these two dudes greet Tohru, they use ちーっす chiissu, which is an interesting term. It comes from konnichiwa, the famous 'during the day’ greeting, shortened all the way down to just “chii.”

Konnichiwa→Konchiwa→Chiwa→Chii

Then the “ssu” is added, which is probably (though as a super slangy term, nobody is really 100% sure) short for です desu, you know the one, which gives it a minimal level of “politeness,” such that it is able to be used toward people of a higher standing than you while still being very slangy and highly informal.

This is the various pieces to the character for “bear,” 熊, in the order you would write them if writing it out by hand properly.

The scene after this, with the delinquent Ryuu training in the mountains and the bear attacking, seems to be a callback to episode 5 of last season:

For this episode title, the saying used is 郷にいては郷に従え gou ni ireba gou ni shitagae, which means pretty much exactly what the English “When in Rome, do as the Romans do” does.

I mostly bring it up here because the one difference between the two is that the gou basically just means a village, so there is not a specific reference to a real-life place like Rome. It makes no difference in this case, but English has a tendency for it’s sayings to do this sort of thing, and it makes translating stuff in a fantasy setting annoying sometimes! Yes I’m venting!

I guess “Acro” for “acrobat” since it’s the Parkour Land mascot?

Part of this line is 大人のずぃかん otona no zikan, which is supposed to be 大人の時間 otona no jikan, “adults’ time.” The difference is that the “じ ji” is pronounced “ずぃ zi/zui.”

Why? Well, Japanese doesn’t actually have a “zi” sound; when the consonant for “z” combines with the vowel “i,” it changes to a “j” sound instead. Obviously this isn’t a problem when speaking Japanese, but it can be a bit of a stumbling block when trying to pronounce English (or other language) words that have that sound in them.

The workaround, when trying to imply a more “correct” pronunciation for such foreign words, is write the sound not as “ジ” (zi/ji) but “ズィ” (”zu” plus a small “i”)―which is what Tohru is pronouncing here.

The reason she’s doing that? Speaking a foreign language comes off as fancy and mature, so she’s playing up the “adult time” bit. It’s not super unlike someone speaking English mixing in a little French, or a French accent, to jokingly make something seem more romantic. “After you, mademoiselle!” or something like that.

味は普通だ。

誰と飲むか、だよね。

それは私とだからですよね…

The second line here is a variation of a saying, one that basically goes “it’s not what you drink that’s important, it’s who you drink it with.” I.e., even the best tasting food or drink will be bad if had with people you hate, and even bad-tasting stuff will be a good time if had with the right people.

So in this case, the idea is that the tea is very average, but Kobayashi is having a great experience anyway. Tohru hopes it’s because she’s with her, but is worried that it’s actually because of the Victorian-style maids.

So maybe something along these↓ lines?

“The taste is just average. But what’s important is who you drink it with.”

“You do mean me by that... right?”

~Fin~

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kobayashi’s Maid Dragon S2 Episode 3 Notes

Sparrows! Specifically the Eurasian tree sparrow, known in Japan as the suzume. You can just about see them all over Japan, all year long—but that doesn’t mean they aren’t a season word!

Depending on their depiction, they can be used as a season word for most times of the year, but a major one is “late spring,” as that’s when they’re out and about finding food for their baby birds. You can also see in the art they look a little floofy, indicative of the winter coat they haven’t fully shed yet; suzume in summer have a more sleek look. Here’s a shot of them from late summer last season:

And from closer to winter here↓. Quite fluffy.

As a quick refresher, 季語 kigo, or season words, are words/phrases/concepts used to give a sense of season to a haiku (or other poem/work of art), which is what part of what differentiates them from a senryuu. They were used pretty frequently in a lot of episodes last season, but a bit less so this time so far.

Where Lucoa and Ilulu are talking about a “right” here, the Japanese word is 資格 shikaku. While this usage is similar to “right” in English, the connotation is a little different as the word actually means more “qualification.”

Whereas a “right” is generally something you have innately in some sense (e.g. if you make art you automatically have copyright over it, you have human rights just for being human, etc.), a shikaku is something you earn (e.g. if you study and take a test for certification program and pass, you’re rewarded with a shikaku.)

Ilulu’s response to the question here is

そういうのは違う。小林がくれたあの言葉はなかったことにはできないから。

One way in which this differs from the English is that she’s not saying it would be right or wrong, but rather not the solution she’s looking for—because it would also mean undoing the words Kobayashi gave her, and that is something she doesn’t want to do, no matter what.

In contrast the English feels more like she thinks it would be wrong to do that, and even if she did it wouldn’t let her escape what Kobayashi said to her. (That would make more sense if Kobayashi had called her out on being evil, but that’s not really what went down.) An alternative wording might be something like:

“That wouldn’t solve anything. Besides, I don’t want to erase what Kobayashi gave me.”

This line is: 小林さんのようにはいかないなー

This is perhaps just my interpretation, but the English here sounds like Lucoa once convinced/helped Kobayashi in some fashion previously, is trying it again with Ilulu, but failing this time. (I don’t that’s ever happened though.)

In contrast, I think the Japanese is saying that Lucoa is trying to be like Kobayashi (e.g. when helping alleviate/solve Tohru’s various worries), and it’s not really working for her. I.e. “It’s not working like when Miss Kobayashi does it.”

Ilulu’s line about “I don’t want to ask Kobayashi about it because she’d probably solve it too easily" seems to support that reading; the dragons know Kobayashi as worries-solver.

The English here has Lucoa saying she’ll go talk to Kanna/Saikawa, and casually telling Ilulu to wait in the bathroom. But Lucoa doesn’t actually talk to the kids, and even if she was planning to, why would Ilulu waiting in the toilet do anything?

The answer is that Lucoa is actually telling Ilulu to talk (to an unspecified subject, assumed to be Saikawa, since she’s a human and thus someone Ilulu feels guilty about interacting with; Kanna she’s more fine with, as a dragon). And instead of “Go ahead and wait in the bathroom,” it’s more of a “Go wait in the bathroom and see what happens,” with the implication Lucoa is going to set something up.

And she does!

“I won’t lie about X, but Y is a different story.” This seems to imply she will still lie about Y? That seems a bit odd to me, especially when she just lied about X (those feelings) to Kanna/Saikawa minutes ago.

The Japanese says something a bit different though.

The core of the middle line here is 気持ちに嘘をつかない kimochi ni uso wo tsukanai. Because the に, the particle indicating “direction,” is attached unadorned to "feelings,” it is saying not “lying about X” but “lying to X.” This construction, to say one is lying to a feeling, is fairly common in Japanese media. It’s basically equivalent in English to lying to yourself about those feelings.

(for “lying about X” you’d change the に into a について or similar)

So basically she’s saying she won’t pretend, to herself at least, that she doesn’t want to play. But that’s a separate issue to whether she has, as she said before, the “right” to play after what she did.

You could maybe put it sort of like this:

“I won’t lie to myself about my feelings anymore. But that doesn’t mean I can act on them after what I did.”

I feel extremely silly even pointing this out, but the beam here is 尿意 nyoui, which is the urge to pee, not necessarily actually needing to pee. Hence why she seems to stop needing to as soon as she gets to the bathroom and walks straight back to the living room with Ilulu after they talk.

“Be deceived” here is not 騙される damasareru, lit. “be deceived,” but 騙し討ちにあう damashi-uchi ni au, which is like being hit by a sneak attack, being stabbed in the back, etc. In a fairly literal sense in this case too, as they’re talking about actual combat.

I mostly bring it up because it feels like there is not much difference between “being deceived” and “being tricked,” despite those being portrayed as polar opposites (deceived by hostile dragons, tricked by kind Kobayashi), so it might have been wise to differentiate them more in the translation.

E.g. perhaps “She had to change to avoid a knife in the back.” (though dragons don’t use knives, so maybe a claw?)

Another pretty minor point, but the “doesn’t know right from wrong” is 分別のない funbetsu no nai, where funbetsu means not so much “knowing right from wrong,” but a more encompassing sense of discretion and maturity.

I mostly bring this one up because it struck as me awkward to say Ilulu explicitly shouldn’t know right from wrong, since that would be going backward to her be okay destroying the city again. Instead it’s more that she shouldn’t need to feel weighed down by what’s “correct” or what she “should” do. One possible alt example:

“So go back to being a kid, and worry more about what you want to do than ought to do.”

(Lucoa also changes from a narrative tone to a more conversational tone at the end, in conjunction with the visual shift away from the flashback, so swapping the “she” to “you” might be appropriate.)

Note how Kanna shuffles the cards here. Depending on where you’re from, this may seem like an odd way of doing it (unless you watched Yugioh maybe). A lot of places with majority English speakers tend to use the overhand shuffle or riffle shuffle, but in Japan (and many other Asian countries) the most common shuffle is the one on display here, known as the Hindu shuffle.

~The More You Know~

The act of handing over a piece of candy like this has been used as imagery in other places in the show as well, though I’ll leave thinking about what it represents to you.

“Blanket” is futon, which is used to refer to both the “mattress” part and “blanket” part of a full futon, the traditional Japanese bedding (not the same thing as the sofa/couch mattress you might hear called a futon in some places).

I mostly mention because just “a blanket” kind of sounds like they’re going to leave them on the floor, but they’re actually going to get the equivalent of a guest mattress (+blanket) to put them to sleep in, as it’s late enough for this to turn into a sleepover.

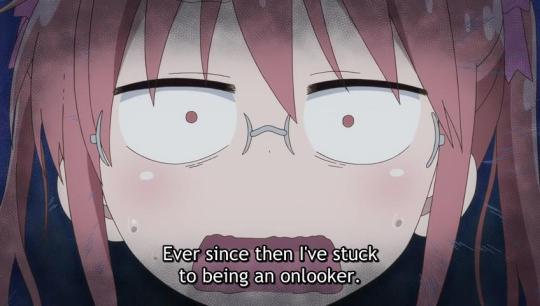

Just as a bit of trivia, the word she uses for “onlooker” here is the same term as the “spectator faction.” In the manga Tohru interjects with “Aww, come on, why not Chaos faction instead?”

Also as a side note to this whole bit about Kobayashi wearing a maid outfit; recall this scene from early in season one, where Tohru found an outfit Kobayashi had bought and stuffed deep in a closet:

Relevant! Anyway, back to the actual episode now:

If you felt like this exchange felt a little disjointed, especially given Tohru’s tone of voice: the idea is that Lucoa is saying Tohru really goes to extremes when it comes to matters relating to Kobayashi, which is implying that it seems excessive to call so many people over for a relatively mild issue (not that she necessarily minds though). Tohru’s response is a slightly defensive “yeah I know, but thanks for coming over anyway.”

(They’re saying it in ways such that you have to read between the lines a bit though, so it may not come across as easily in a translation.)

The word for “cold” here is 水くさい mizu-kusai, basically meaning “watered down” (like beer etc.), and used frequently to refer to a person/actions/words that the speaker considers too reserved for the relationship they have with the other person.

So it’s similar to cold, but cold in the context of already warm relationship. If talking about a stranger or someone you don’t get along with normally, you shouldn’t use 水くさい; you can just say 冷たい tsumetai (lit. “cold”) or similar.

In this context you could probably have her say “No need to apologize, Kobayashi-san.”

Also I like how they swap around the honorifics (Miss, Lady, -san, -sama, etc.) based on the speaker (I think differentiating between dragons and native-Japanese-speaking humans?). I would say it works given the setting, but that’s just me.

The text there says “Money Street.” It’s probably obvious, but it’s based primarily on Monopoly, which is semi-popular in Japan (though not to the extent as say in the US).

Just some trivia, but the “sales pitch” for the game in the Japanese market is more that it’s an educational game that teaches investing and negotiation skills. (The origin of the game in general being an educational tool about exploitation of tenants by landlords, so not quite the same thing.)

Japan also has Momotarou Dentetsu (”Momotetsu”), which is a video game series that’s been around since the NES and is broadly similar to Monopoly rules-wise.

I just want to point out, amid all the riches, the bag of potato chips and other junk food in the back there.

Mini-trivia: the cardboard boxes in the background there seem to be a mix of the Amazon logo and the Seino Transportation logo, a Japanese shipping company with a kangaroo logo.

You probably noticed it without me pointing it out, but I enjoyed the fact Elma got corn starch* all around her mouth from the daifuku and then immediately got told to go play with the kids while the adults are talking.

*It may seem like powdered sugar if you’re used to donut holes, but daifuku, like most Japanese sweets (wagashi) generally, is not heavily sugared and not even particularly sweet by the standard of most “sweets” (which is part of the appeal for many). The skin of the daifuku is powdered with corn starch or similar simply to make it less sticky.

Kobayashi’s “do that” here is やろー yarou, which can mean “let’s do X” (which is a construction often used to tell/suggest someone to do something, without really including yourself in the “us”).

However in this case—especially given Kobayashi’s pronunciation and tone of voice—I think it’s actually a homophone of that, a form of 野郎 yarou, a word for “guy” with often negative connotations, like saying “son of a” or “asshole” etc.

The idea, I think, being that his immediate agreement of “Oooh, right I didn’t think about you wearing it,” comes with a heavy implication of “yeah you’re right, you couldn’t pull off something cute like that,” so she’s replying with a (mostly good-natured) “oh you fucker.”

This giant 完 kan means “the end,” used like “fin” at the end of a story or game etc. It’s also frequently used in “fake end” jokes. E.g. a show about a sentient zombie might start with the main character getting hit by a truck and dying immediately. The end! ...Except not, and they wake up as a zombie.

So here, the original goal was “make a maid outfit for Kobayashi to wear.” Then Georgie convinces Kobayashi that anything is a maid outfit as long as you are a maid at heart, so really, she’s already wearing one! The end! ...Except not.

Here’s some extra, probably needless, context on this “annoying”: it uses the word 面倒くさい mendokusai, which is basically used to describe something as annoying, a pain, etc. When used to describe a person like this, one of the ways it can be taken is specifically that the person is really fussy about details that others wouldn’t really care about—which describes Kobayashi about maids pretty well.

So just for clarity, it’s not necessarily “I became an annoying person who is a maid otaku,” and can be more of a “within the context of my maid otaku-ness I became annoying.” Just to kind of shed some light on the extent of her self-deprecation here.

The word Kobayashi uses for “helping with the housework” is 家事手伝い kaji-tetsudai, which is a noun* that means “a housework helper”... here, basically a more bland way for a native Japanese speaker to say maid.

Hence why Tohru reacts with “Oh, don’t call me that, call me a maid!”; Kobayashi went as far as to acknowledge her clothes as a maid outfit, but not quite as far as calling her maid outright. That’s our “annoying maid otaku” doing her thing.

*It can also be verbed.

These neighborhood notices, 回覧板 kairan-ban, ~lit. circular notice, are a method used by local governing organizations to distribute information or forms etc. For example, about an upcoming neighborhood event to pick up litter.

The general idea is that one person gets the notice, reads it, signs it, then goes and passes it to the next household in line. It saves paper versus sending everyone a thing in the mail, encourages interaction between neighbors, and is more likely to be read than a flyer/email, though some people consider them a pain and they generally feel a little dated.

The phrase for “piercing noise” is 劈く金切り音, tsunzaku kanakiri-on, ~lit. “ear-piercing sound of tearing metal.”*

“Was it that loud?” in the Japanese is a little different, そんな音してた?, meaning “was it making a sound like that?”

I’m mostly just bringing it up to say that the “Sasakibe’s cooking isn’t just loud, the sounds don’t even make sense” gag is alive and well this season.

*The “sound of tearing metal” phrase can also used idiomatically for some types of high pitched sounds, but I imagine it was chosen very deliberately here.

It’s probably obvious, but this is a reference to the music video of the OP for season one. You can see it on the official channel for the band, fhána, here.

The season two music video is here, and it seems to have decent English subtitles for the lyrics if you’re curious what they are.

The adjective here is ニヒル nihiru, an abbreviation of nihilistic. It can be used as actually “nihilistic” like in English, but it can also be used more colloquially to describe a person with dark vibes. It can almost be a compliment!

“Sleeping” here is 惰眠をむさぼる damin wo musaboru. Damin is not just sleep, but “worthless” sleep—not like a nap because you’re tired. Musaboru is a verb for ~gorging upon on something (often metaphorically, not just food).

The two words are somewhat frequently used together for, basically, lying around the house doing nothing all day. And not in a particularly flattering way, so it’s pretty funny for her to just be like “yeah I do that as a hobby I guess.”

It doesn’t mean the same thing, but it’d be like saying your hobby is loitering. Maybe could have translated as like “Hobbies? Vegetating.” or “Procrastinating?” or something, though I don’t know if those would have the right impact...

Kanna’s word for “idol” here is アイドル aidoru, i.e. idol in the pop culture sense.

Tohru’s word is 偶像 guuzou, or idol in the religious sense.

(Tohru swaps to the pop culture “idol” when she starts talking about Kobayashi though.)

Kanna’s “lost it” it here is 大変 taihen, a pretty common, almost generic word used as an intensifier (greatly, immensely, seriously, terribly, really, etc.) in both positive and negative ways. E.g. “thanks, you really saved me!” or “that was extremely rude.”