#etymological doublets

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Pity and piety are doublets: they both stem from Latin pietātem, the accusative of pietās. Pity comes from Old French pité, a word inherited from spoken Latin. It underwent the sound changes that turned Latin into French. Piety was borrowed from Old French pieté, which itself was a borrowing from written Latin. Here's number 8 in my series: English doublets from Latin via French!

#historical linguistics#linguistics#language#etymology#english#latin#french#old french#etymological doublets#lingblr#middle french

281 notes

·

View notes

Text

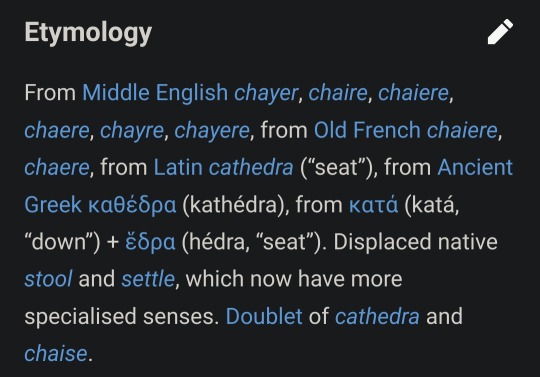

The etymology of chair. I never thought it comes from cathedra!

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

“gender” is from the latin word “genus” meaning “kind.” it is a doublet (that is, shares an etymological origin) with the words “genre” //// gotta replace the gender binary of "men" and "women" with the trinary of "poetry" "prose" and "drama"

which one of you relies on the aesthetic qualities of language in the relationship and which one of you follows the natural flow of speech

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

Names for the number 0 in English

"Zero" is the usual name for the number 0 in English. In British English "nought" is also used and in American English "naught" is used occasionally for zero, but (as with British English) "naught" is more often used as an archaic word for nothing. "Nil", "love", and "duck" are used by different sports for scores of zero.

There is a need to maintain an explicit distinction between digit zero and letter O,[a] which, because they are both usually represented in English orthography (and indeed most orthographies that use Latin script and Arabic numerals) with a simple circle or oval, have a centuries-long history of being frequently conflated. However, in spoken English, the number 0 is often read as the letter "o" ("oh"). For example, when dictating a telephone number, the series of digits "1070" may be spoken as "one zero seven zero" or as "one oh seven oh", even though the letter "O" on the telephone keypad in fact corresponds to the digit 6.

In certain contexts, zero and nothing are interchangeable, as is "null". Sporting terms are sometimes used as slang terms for zero, as are "nada", "zilch" and "zip".

Zero" and "cipher"

"Zero" and "cipher" are both names for the number 0, but the use of "cipher" for the number is rare and only used in very formal literary English today (with "cipher" more often referring to cryptographic cyphers). The terms are doublets, which means they have entered the language through different routes but have the same etymological root, which is the Arabic "صفر" (which transliterates as "sifr"). Via Italian this became "zefiro" and thence "zero" in modern English, Portuguese, French, Catalan, Romanian and Italian ("cero" in Spanish). But via Spanish it became "cifra" and thence "cifre" in Old French, "cifră" in Romanian and "cipher" in modern English (and "chiffre" in modern French).

"Zero" is more commonly used in mathematics and science, whereas "cipher" is used only in a literary style. Both also have other connotations. One may refer to a person as being a "social cipher", but would name them "Mr. Zero", for example.

In his discussion of "naught" and "nought" in Modern English Usage, H. W. Fowler uses "cipher" to name the number 0.

O" ("oh")

In spoken English, the number 0 is often read as the letter "o", often spelled oh. This is especially the case when the digit occurs within a list of other digits. While one might say that "a million is expressed in base ten as a one followed by six zeroes", the series of digits "1070" can be read as "one zero seven zero", or "one oh seven oh". This is particularly true of telephone numbers (for example 867-5309, which can be said as "eight-six-seven-five-three-oh-nine"). Another example is James Bond's designation, 007, which is always read as "double-o seven", not "double-zero seven", "zero-zero seven", or "o o seven".

The letter "o" ("oh") is also used in spoken English as the name of the number 0 when saying times in the 24-hour clock, particularly in English used by both British and American military forces. Thus 16:05 is "sixteen oh five", and 08:30 is "oh eight thirty".

The use of O as a number can lead to confusion as in the ABO blood group system. Blood can either contain antigen A (type A), antigen B (type B), both (type AB) or none (type O). Since the "O" signifies the lack of antigens, it could be more meaningful to English-speakers for it to represent the number "oh" (zero). However, "blood type O" is properly written with a letter O and not with a number 0.

In sport, the number 0 can have different names depending on the sport in question and the nationality of the speaker.

"Nil" in British sports

Many sports that originated in the UK use the word "nil" for 0. Thus, a 3-0 score in a football match would be read as "three-nil".[1] Nil is derived from the Latin word "nihil", meaning "nothing", and often occurs in formal contexts outside of sport, including technical jargon (e.g. "nil by mouth") and voting results.

It is used infrequently in U.S. English, although it has become common in soccer broadcasts.

"Nothing" and "oh" in American sports

edit

In American sports, the term "nothing" is often employed instead of zero. Thus, a 3-0 score in a baseball game would be read as "three-nothing" or "three to nothing". When talking about a team's record in the standings, the term "oh" is generally used; a 3-0 record would be read as "three and oh".

In cricket, a team's score might read 50/0, meaning the team has scored fifty runs and no batter is out. It is read as "fifty for no wicket" or "fifty for none".

Similarly, a bowler's analysis might read 0-50, meaning he has conceded 50 runs without taking a wicket. It is read as "no wicket for fifty" or "none for fifty".

A batsman who is out without scoring is said to have scored "a duck", but "duck" is used somewhat informally compared to the other terms listed in this section. It is also always accompanied by an article and thus is not a true synonym for "zero": a batter scores "a duck" rather than "duck".

A name related to the "duck egg" in cricket is the "goose egg" in baseball, a name traced back to an 1886 article in The New York Times, where the journalist states that "the New York players presented the Boston men with nine unpalatable goose eggs", i.e., nine scoreless innings.

"Love" and "bagel" in tennis

In tennis, the word "love" is used to replace 0 to refer to points, sets and matches. If the score during a game is 30-0, it is read as "thirty-love". Similarly, 3-0 would be read as "three-love" if referring to the score during a tiebreak, the games won during a set, or the sets won during a match. The term was adopted by many other racquet sports.

There is no definitive origin for the usage. It first occurred in English, is of comparatively recent origin, and is not used in other languages. The most commonly believed hypothesis is that it is derived from English speakers mis-hearing the French l'œuf ("the egg"), which was the name for a score of zero used in French because the symbol for a zero used on the scoreboard was an elliptical zero symbol, which visually resembled an egg.

Although the use of "duck" in cricket can be said to provide tangential evidence, the l'œuf hypothesis has several problems, not the least of which is that in court tennis the score was not placed upon a scoreboard. There is also scant evidence that the French ever used l'œuf as the name for a zero score in the first place. (Jacob Bernoulli, for example, in his Letter to a Friend, used à but to describe the initial zero–zero score in court tennis, which in English is "love-all".) Some alternative hypotheses have similar problems. For example, the assertion that "love" comes from the Scots word "luff", meaning "nothing", falls at the first hurdle, because there is no authoritative evidence that there has ever been any such word in Scots in the first place.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first use of the word "love" in English to mean "zero" was to define how a game was to be played, rather than the score in the game itself. Gambling games could be played for stakes (money) or "for love (of the game)", i.e., for zero stakes. The first such recorded usage quoted in the OED was in 1678. The shift in meaning from "zero stakes" to "zero score" is not an enormous conceptual leap, and the first recorded usage of the word "love" to mean "no score" is by Hoyle in 1742.

In recent years, a set won 6-0 ("six-love") has been described as a bagel, again a reference to the resemblance of the zero to the foodstuff. It was popularised by American announcer Bud Collins.

Null

In certain contexts, zero and nothing are interchangeable, as is "null". However, in mathematics and many scientific disciplines, a distinction is made (see null). The number 0 is represented by zero while null is a representation of an empty set {}. Hence in computer science a zero represents the outcome of a mathematical computation such as 2−2, while null is used for an undefined state (for example, a memory location that has not been explicitly initialised).

In English, "nought" and "naught" mean zero or nothingness, whereas "ought" and "aught" (the former in its noun sense) strictly speaking mean "all" or "anything", and are not names for the number 0. Nevertheless, they are sometimes used as such in American English; for example, "aught" as a placeholder for zero in the pronunciation of calendar year numbers. That practice is then also reapplied in the pronunciation of derived terms, such as when the rifle caliber .30-06 Springfield (introduced in 1906) is accordingly referred to by the name "thirty-aught-six".

The words "nought" and "naught" are spelling variants. They are, according to H. W. Fowler, not a modern accident as might be thought, but have descended that way from Old English. There is a distinction in British English between the two, but it is not one that is universally recognized. This distinction is that "nought" is primarily used in a literal arithmetic sense, where the number 0 is straightforwardly meant, whereas "naught" is used in poetical and rhetorical senses, where "nothing" could equally well be substituted. So the name of the board game is "noughts & crosses", whereas the rhetorical phrases are "bring to naught", "set at naught", and "availeth naught". The Reader's Digest Right Word at the Right Time labels "naught" as "old-fashioned".

Whilst British English makes this distinction, in American English, the spelling "naught" is preferred for both the literal and rhetorical/poetic senses.

"Naught" and "nought" come from the Old English "nāwiht" and "nōwiht", respectively, both of which mean "nothing". They are compounds of no- ("no") and wiht ("thing").

The words "aught" and "ought" (the latter in its noun sense) similarly come from Old English "āwiht" and "ōwiht", which are similarly compounds of a ("ever") and wiht. Their meanings are opposites to "naught" and "nought"—they mean "anything" or "all". (Fowler notes that "aught" is an archaism, and that "all" is now used in phrases such as "for all (that) I know", where once they would have been "for aught (that) I know".)

However, "aught" and "ought" are also sometimes used as names for 0, in contradiction of their strict meanings. The reason for this is a rebracketing, whereby "a nought" and "a naught" have been misheard as "an ought" and "an aught".

sometimes used as names for 0, in contradiction of their strict meanings. The reason for this is a rebracketing, whereby "a nought" and "a naught" have been misheard as "an ought" and "an aught".

Samuel Johnson thought that since "aught" was generally used for "anything" in preference to "ought", so also "naught" should be used for "nothing" in preference to "nought". However, he observed that "custom has irreversibly prevailed in using 'naught' for 'bad' and 'nought' for 'nothing'". Whilst this distinction existed in his time, in modern English, as observed by Fowler and The Reader's Digest above, it does not exist today. However, the sense of "naught" meaning "bad" is still preserved in the word "naughty", which is simply the noun "naught" plus the adjectival suffix "-y". This has never been spelled "noughty".

The words "owt" and "nowt" are used in Northern English. For example, if tha does owt for nowt do it for thysen: if you do something for nothing do it for yourself.

The word aught continues in use for 0 in a series of one or more for sizes larger than 1. For American Wire Gauge, the largest gauges are written 1/0, 2/0, 3/0, and 4/0 and pronounced "one aught", "two aught", etc. Shot pellet diameters 0, 00, and 000 are pronounced "single aught", "double aught", and "triple aught". Decade names with a leading zero (e.g., 1900 to 1909) were pronounced as "aught" or "nought". This leads to the year 1904 ('04) being spoken as "[nineteen] aught four" or "[nineteen] nought four". Another acceptable pronunciation is "[nineteen] oh four".

Decade names

See also: Aughts

While "2000s" has been used to describe the decade consisting of the years 2000–2009 in all English speaking countries, there have been some national differences in the usage of other terms.

On January 1, 2000, the BBC listed the noughties (derived from "nought") as a potential moniker for the new decade. This has become a common name for the decade in the U.K.and Australia, as well as some other English-speaking countries. However, it has not become the universal descriptor because, as Canadian novelist Douglas Coupland pointed out early in the decade, "[Noughties] won't work because in America the word 'nought' is never used for zero, never ever".

The American music and lifestyle magazine Wired favoured "Naughties", which they claim was first proposed by the arts collective Foomedia in 1999.However, the term "Naughty Aughties" was suggested as far back as 1975 by Cecil Adams, in his column The Straight Dope.

interchangeable, as is "null". However, in mathematics and many scientific disciplines, a distinction is made (see null). The number 0 is represented by zero while null is a representation of an empty set {}. Hence in computer science a zero represents the outcome of a mathematical computation such as 2−2, while null is used for an undefined state (for example, a memory location that has not been explicitly initialixed).

Slang

Sporting terms (see above) are sometimes used as slang terms for zero, as are "nada", "zilch" and "zip".

"Zilch" is a slang term for zero, and it can also mean "nothing". The origin of the term is unknown.

Silvio Pasqualini Bolzano inglese ripetizioni English insegnante teacher

#dialects#lexicography#lexicology#linguistics#english#american english#languages#mathematics#math#maths#geometry#colloquialism#informal#sports#numerology#vocabulary#definition#british english#dictionary#encyclopedia#score#slang#etimologia#linear algebra#lexicon#arithmetic#calculator#calculations#calculus#fraction

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Etymological doublets

host and guest both derive from the same Indo-European root *ghosti- ‘stranger, guest, host’, one through Latin and one through Germanic.

This is an example of a doublet—a set of words in a language that have the same etymological root.

Usually this happens when the same word enters a language through different paths. For example, frail and fragile are a doublet that came to English through Old French vs. directly from Latin, respectively.

The same word can also be borrowed at different points in history. For example, street and strata were both borrowed from Latin strāta ‘laid down, spread out, paved’, but street was borrowed before the Anglo-Saxons had even come to England, while strata was borrowed during the Renaissance.

Here are a bunch of doublets in English!

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

"nefling" as gender-neutral "sibling-child"

There's been some discussion about a gender-neutral term for "niece or nephew" and I know there's been some settling on "nibling". And I really don't like that, as it is an obviously play on "nibble" which implies something tiny and inconsequential. Which maybe works if they're a baby, but is generally condescending.

Looking through the etymology of "nephew" and "niece", I think that "nefling" is probably the most sensible linguistic construction.

Nephew:

From Middle English nevew, neveu (“nephew, grandson”), from Old French neveu, from Latin nepos, nepōtem, from Proto-Italic *nepōts (also, from whence we get "nepotism") Displaced or absorbed the inherited English neve (“nephew, grandson, male cousin”), from Middle English neve, from Old English nefa, from Proto-West Germanic *nefō, from Proto-Germanic *nefôd

Niece:

From Middle English nece (“niece, granddaughter”), from Old French nece (“niece, granddaughter”) (Modern French nièce (“niece”)) from Late Latin neptia, representing Latin neptis (“granddaughter”), from Proto-Indo-European *néptih₂ (“granddaughter, niece”). Doublet of nift. (displaced form)

nift: From Middle English nyfte, nift, nifte, from Old English nift (“niece, granddaughter”), from Proto-Germanic *niftiz (“niece”), from Proto-Indo-European *néptih₂.

All the terms we have for niece and nephew, both in original OE and in French borrowings, derive from the PIE *nepōts (*néptih₂ itself comes from *nepōts + *-ih₂.

If you trace those four terms back to a common ancestor, we could have "nepper", "nepling" or even "nephling", but that's crossing etymological forms (something English would never (/s) do, I know). But honestly, I just don't like the sound of "nepper" (close to "nipper", a colloquial for "small child" and very similar to "nibbler").

But if you go from the Proto-Germanic *nefod and *niftiz, you can construct either "nifling" or "nefling". Since "niffling" is slang for "to pilfer" and a "niffler" is a term for "trifle", I'm strongly inclined to the latter. And because we're taking the Germanic linguistic root, we don't have to deal with a "-ph-" in there.

"Nefling" it is?

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

*ver- (‘earn’)

Not entirely my own analysis, but rather something I’ve picked up from various Fando’a dictionaries and expanded upon.

Let’s look at canon instances of verd and its derivations first, then *ver- without the d, then some non-canon derivations, and lastly a bit of Mandalorian history for those who care to read that far.

Canon: verd & derivations

verd (n): soldier

I think this is a contracted form of ver-ad, ‘one who earns’ (see this post about agent nouns or this post about ad for more), making this construction equivalent to English soldier. Soldier comes (via French) from Latin soldarius, lit. ‘having pay’, ultimately from solidus, the name of a Roman gold coin. So this word refers to the traditional Mandalorian trade of working as mercenaries, which is probably the original meaning of this word.

And then we have many derivations and compound words with verd:

neverd (n): civilian

“Not a soldier”

verd’yc (adj): aggressive

Not a bad quality in Mandalorian culture! You could also translate this as spirited, decisive, bold, audacious, daring, or go-getter.

al’verde (n): commander

“Leader of soldiers”

ver’verd (n): mercenary

This is etymologically funnily enough “mercenary-mercenary”. Such doublets happen all the time in natural languages though, as the original word changes meaning.

Canon: *ver- in other words

*ver- also occurs in:

ver’alor (n): lieutenant

“Paid leader” or “hired leader”. Comparable to Commissioned Officers, I think, hence the translation as lieutenant (mando ranks probably aren’t exactly the same as ones in any particular country on Earth). Possibly represents e.g. the permanent command staff of a mercenary company, rather than the rank and file who might contract for a season or for a specific campaign. Traviss describes mando military organisation as “a flat pyramid”, e.g. lots of people at the bottom, few on top; so this probably refers to fewer people than English CO does.

veriduur (n): courtesan, sex worker

“Paid spouse”

ver’mircit (n): hostage

“Prisoner for money”

beroya (n): bounty hunter

This could be either be-roya, “of hunt”—or it could be ver-oya, “pay hunter”. The v and b sounds are very close to each other, especially if you pronounce v as a bilabial fricative /β/, and the sound change v > b is very plausible. So it’s possible that *ber- is an alternative form of this root, or that beroya was loaned into “standard Mando’a” (no such thing, I know) from another dialect of Mando’a where that sound change has happened.

Non-canon derivations

vere (n.): wages, payment (from Tuuri)

Lit. “earnings”.

berir (v): to pay, to buy (from Oyu’baat)

By analogy to beroya.

berii (n): buyer

From ber + ii.

verar (v): to earn, deserve

Two verbs from the same root, diverged meanings. Happens all the time in natural languages. Gave it a different vowel so it wouldn’t get mixed up as easily.

verdin (n): merit, reward; share

From ver-din, sort of “earnings given” or “give what’s earned”. From here you also get verdinyc ‘meritorious, rewarding’ and verdinir ‘to reward, merit’.

verdir (v): to work as a mercenary

Lit. “to soldier”, but keeping the original sense of verd here.

vergam (n): uniform

Whatever monkey suit you’re paid to wear that’s not beskar’gam.

A history lesson

When thinking of these derivations, I went back to the time of the Mandalorian wars. (And my theory of Modern Mando’a being a creole language that developed in their aftermath.)

So consider the Taung: these are the ancient Mandalorians, who have come to worship war in itself (or in other words, have come to see waging war as an expression of the divine). They’ve conquered large swathes of the galaxy and slaughtered entire peoples in this pursuit. But war is a hungry beast that gobbles up both men and machines, so this warfare must have taken a toll on the Taung even if the plunder fills their coffins.

So the revelation that Mandalore the Ultimate receives on planet Shogun is probably honestly less about other races being worthy of being Mandalorians*, and more about the strategic insight that if instead of total slaughter they assimilate the conquered peoples and draw from them to fill up their ranks, they can go on to conquer indefinitely.

*At this point there’s already a precedent for adopting other races as Mandalorians (e.g. the Mandallian giants), but I think that before the Neo-Crusaders, it was probably rather marginal. It didn’t cause significant changes in the culture, and they were probably assimilated slowly and in small numbers, and so learned the language more or less perfectly. It isn’t until the Neo-Crusaders that assimilating other races becomes widespread (otherwise it wouldn’t be a revelation). And the more the Taung conquer, the more peoples they assimilate and the less they have the time and resources to teach them the language and their ways as they themselves become diluted among the ranks.

Also, let’s be real: while Mandalore the Ultimate is said to have decreed that the recruits be treated equally among the clans, many of those recruits were probably not there voluntarily, but rather given the choice of being conquered/slaughtered or joining up. I’m sure many people saw joining as an opportunity to move up in life (better to be a Mandalorian warrior than a poor Rimmer), but many we’re probably shanghaied into service and some were little better than slaves.

And so the Mandalorian armies swell, and conquer, and conquer, reaching as far as Coruscant itself. They seem unstoppable until the Republic employs the desperate doomsday weapon on Malachor VI, which cripples the Mandalorian army and leadership. In the aftermath, the Mandalorians probably can’t hold on to their entire newly conquered Empire, so many areas are retaken by the Republic or otherwise secede. Without those resources and the continuous conquest they can’t pay their armies, so now there are lots of disaffected and unemployed soldiers, who turn mercenaries.

And these aren’t your honourable mercenaries ala Jaster Mereel yet. Rather, they are displaced and disaffected people who have no other trades or possibilities to ply them in the war-torn galaxy. So they take any jobs and if there are no jobs, do a bit of plundering on the side. This diaspora and disarray lasts for the next 300 years or so. It takes several centuries and galactic wars of cultural change, before Mandalorians have grappled with the after-effects of the Mandalorian wars, turned from worshiping the old gods into believing primarily in the Manda, turned their focus from conquest into thriving in adversity, and developed the philosophical tradition of military ethics that eventually produces Jaster Mereel and his likes.

All of this to say: when we’re thinking about the etymologies of Modern Mando’a words, we should be thinking of these first few generations of non-Taung Mandalorians. But when we’re thinking of the definitions of the words as they’re used today, we should think of the cultural change that came afterwards. So for example: verd was probably originally a mercenary, but over time came to mean a soldier. Verdin was originally “loot, plunder” or one’s share of it that whoever was in charge of the payroll doled out after a campaign (based on one’s role, performance, etc). In time, it became to mean other kinds of rewards and fruits of one’s labour.

#mando’a#mandoa#mando'a#mando’a language#mandalorian culture#meta: mandalorians#mandalorians#star wars#mando’a extended dictionary#mando’a words#ranah talks mando’a#mando’a etymology#mandalorian history

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dies Irae - Chapter 1

Fandom: Once Upon a Time (TV) Rating: Explicit Warnings: Creator Chose Not To Use Archive Warnings Relationships: Belle/Rumplestiltskin | Mr. Gold Characters: Belle (Once Upon a Time), Rumplestiltskin | Mr. Gold, Mad Hatter | Jefferson, Evil Queen | Regina Mills, Wicked Witch of the West | Zelena, Red Riding Hood | Ruby, Grumpy | Leroy, Captain Hook | Killian Jones, Grace | Paige (Once Upon a Time) Additional Tags: AU, Angst, Violence, archeology, psychic questing, Religion, spirituality, Magic, Supernatural - Freeform, Romance, Smut Summary:

A strange man confronts Doctor Belle French after one of her lectures, and claims to need her help. He also claims to know that she is troubled, and can offer her protection. When events transpire that lead Belle to take up that offer, a desperate search begins to find a series of ancient artifacts, and Belle and her friends - both old and new - face increasing danger as they try to secure the artifacts for the powers of good before they can fall into very wrong hands, and possibly threaten every living thing in Storybrooke and beyond!

Chapter One: Ēvincere

Etymology of the English word evince (v.) c. 1600, "disprove, confute," from French évincer "disprove, confute," from Latin evincere "conquer, overcome subdue, vanquish, prevail over; elicit by argument, prove," from assimilated form of ex "out" (see ex-) + vincere "to overcome" (from nasalized form of PIE root *weik- (3) "to fight, conquer"). Meaning "show clearly" is late 18c. Not clearly distinguished from its doublet, evict, until 18c. Related: Evinced; evinces; evincing; evincible.

"And I cannot stress hard enough…”

He didn’t move. While all around him in the lecture hall, those gathered in unspoken conspiracy seemed to squirm and shift uncomfortably in their places on the long, hard wooden benches, he remained immobile.

“…that if you are coming into archeology with dreams of… fame and fortune; of glory even, then you have been sadly misinformed.”

He sighed - perhaps the first sign of life since he entered the hall - and moved his hands with slow, measured precision, to turn to collar of his black, woolen trench coat up as if to defend against a unwelcome draft. He’d heard this before, several times, and as she continued, almost syllable for syllable, matched her litany.

“Treasure comes in many forms,” he muttered as she spoke, “and it isn’t always - is rarely as a matter of fact - gold or precious artifacts.” He recitation was lifeless and without the passionate inflection with which she spoke.

“But is something more precious still…” She gave a pause then, and in his line of sight, the watcher could separate those that had been caught in her spell, and those that were merely along for the ride. The former leaned, slightly, toward the front of the lecture hall, where the diminutive Doctor Belle French held court, and finished with all the mysteriousness it seemed that she could muster, “Knowledge.”

If she might have continued, he would never know, as the bell signaling the end of the alloted time sounded, and the ever impatient students began stuffing backpacks and tote bags with notebooks and textbooks; wooden boxes full of sharpened pencils and depleted ink pens, and hurried to rise and leave.

Still, he sat immobile, one booted foot up on the desk-like shelf in front of him, the other splayed slight to the side, toward the aisle. Others along his row shifted impatiently; pointedly waiting for him to take his foot down at least, so they could sidle, inconvenienced, past this apparent miscreant. He didn’t move. He didn’t even respond to the irritated murmuring; never once took his eyes off French as she too began packing away the lecture notes into folders, then the folders into piles on a table already replete with books and other papers.

“Are you gonna move y’foot, mate?”

Apparently, the patience of the nearby attendees had worn thin, or at least their courage had thickened, one or the other.

“Go around,” he said, his voice low and full of gravel, as well as gravitas. It was all he said, and neither did he make any attempt to remove his foot from blocking the way.

After another moment of immobility, and with the press of other students behind him, the one that had spoken tried again, more threatening this time as he grumbled, “I said move yer foot.”

With the grace of a highly trained dancer, and turning as he did indeed move his foot to stand, he turned to face the student, towering over the younger man as he said quietly, and with patience that somehow held a deadly quality, “And I said, go. Around.”

The student opened his mouth to make a third protest, but as he shifted slightly, something seemed to change the younger man’s mind and, muttering something not quite audible, but he was certain was unlikely to be very complementary, did indeed turn, and pushing the other students ahead of him, moved and exited the row from the other side.

The students were already forgotten though, and he turned his attention back to Doctor French. She was slowly clearing the table in front of the podium of all the books and papers littered there, packing them away in her already overstuffed messenger bag, paying absolutely no heed to the room around her, nor - he guessed - the energies in it.

When he felt the moment was right, just as the light descended enough to case a beam across the lecture hall and illuminate the dust that had yet to settle, he spoke.

“It isn’t true, you know?” he said. Though his voice was still soft he pitched it so that the acoustics of the hall carried it clearly to the professor. She started slightly, then looked up at him, raising a hand to shield her eyes from the light that concealed him.

“I beg your pardon?” she shot back, her voice terse, a challenge.

“Granted,” he said, and began to slowly descend the steps that flanked the tiers of seats.

“No, that’s not—” she began, slightly flustered, before annoyance got the better of her and she demanded, “I’m sorry - who are you?”

Once he reached the floor, he strode across to her, his trench coat almost billowing, cloak-like behind him, and once close enough held out a hand in her direction.

“My name is Jefferson,” he told her, “And I need your help to do something that I can’t.”

-------------

Belle blinked, then with a slight scoff, and ignoring his still outstretched hand said, “Well you have a very strange way of showing it!” Then she returned to packing her bag.

“In return,” he continued, apparently unmoved by her response, “I may be able to assist you.”

“I don’t need your help,” she snapped. The tone in his voice made the small hairs on the nape of her neck stand on end. Had he been watching her?

“There are powers in this world, Doctor French, who have no regard for the living, nor respect for the dead. I suspect you know the type, if not the very ones of whom I speak.”

She looked up at that, fixing her eyes first on his face, undeniably handsome, but clearly more than a little haunted behind the seriousness of his expression, and then traveling the length of the sombre-clad figure that stood before her, seeming to know more about her than a stranger should.

She couldn’t help but notice the small pin that graced his otherwise unadorned lapel: an equal armed, red cross, their width narrower at the center than they were at the ends, set against a white background that was stark against the black of his coat.

“Now you listen, Mister Je—.”

“Just Jefferson,” he corrected.

“I don’t know who you are, or where you came from,” she tried for indignation, but even to her own ears, the tone spoke more of fear, “or even why you’re here, but—”

“I told you,” he said, his voice soft, “I need your help.”

She frowned, and couldn’t muster an answer, just stood and shook her head.

He raised his long forgotten, outstretched hand to her again, and as if by magic, though she was certain it was slight of hand, he produced a velum business card and held it out to her, clasped between his index and middle finger.

“There’s a man, his name is Mister Gold,” he said. “If you have cause to change your mind, all you have to do is go to him. It’s very important you tell him what’s been going on. He can protect you, but you must tell him exactly what’s been happening. He’ll know what to do.”

He nodded then, just once, to the business card he still held, and hesitantly, she reached for it, and glancing down at it, saw the words that graced the center of the otherwise unadorned card.

“Gold - Antiquarian,” it said, and then in relief around the edges, words that she had to turn the card one way and then the other in order to read. Latin words.

Non nobis Domine, non nobis, sed nomini tuo da gloriam.

When she looked up, Jefferson was already gone.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Texan di

pronunciation /di/

etymology

from English do.

Related to Californian de, Pennsylvanian dy, and Mississippian yi, amongst others. Doublet of daü.

definitions

(intransitive) to do, to act, to perform an action

(transitive, auxiliary) to do

(transitive) to make, to create, to form

(with ef) to hide, to cover, to make invisible

(with eüwar) to repeat, to redo

(with wít) to combine, to put together

(intransitive, with eoz) to expire, to become outdated

(with deon) to hold still, to fix tightly

(with ín) to overwhelm

(with eotwórt) to express, to show

grammar

irregular verb

di, infinitive (non-finite) and lemma

di, 1st and 2nd person singular, and plural non-past (finite)

der, 3rd person singular non-past (finite)

dít, past (finite)

bdi, habitual (finite or non-finite)

dűng, continuous (non-finite)

don, passive

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Please can you explain this Persian/Farsi debate to an ignorant westerner?

Time for a philology lesson!

The oldest form of my language was called Ariya (𐎠𐎼𐎡𐎹) by its speakers; the name shares a root with Sanskrit ārya (आर्य), and was simply an autonym for the people who lived in the area and spoke Indo-Iranian—it’s the root of the English word Aryan, too, although that has its own socio-political connotations thanks to the ideology of the Nazi Party. Ariya is the root of the word Iran, and so it’s really the ‘original’ name for both the region and the language, without foreign influence.

The speakers of Ariya lived during the Achaemenid era, around the area they called Parsa (𐎱𐎠𐎼𐎿), known to us as Persis via the Greeks. They’re the ancestors of today’s Persians, the majority ethnic group within modern Iran. Parsa roughly approximated what is now known as Fars Province (فارس) in present-day Iran, and the modern autonym for the national language and majority ethnicity, Farsi (فارْسی), is the adjectival form of Fars. Parsa became Fars because of the influence of Arabic, a Semitic language unrelated to the Indo-Iranian languages; Arabic doesn’t have a p sound, and so foreign borrowings undergo a sound change that transforms p to f. The Arabs called the language and the people Farisiyy (فَارِسِيّ), which was then ultimately reborrowed by the Indo-Iranian speakers as Farsi. This is why we still refer to Zoroastrians in India, who migrated during the Arab Conquest, as Parsi (پارسی), not Farsi—because they moved there before we’d adopted the Arabic f sound-change.

So, ‘Persian’—which comes from the Ancient Greek word Persis (Περσίς), which in turn derives from Old Persian Parsa (𐎠𐎼𐎡𐎹)—shares the same root, and refers to the same language and region, as ‘Farsi’—which comes from Arabic Farisiyy (فَارِسِيّ), which in turn derives from Old Persian Parsa (𐎠𐎼𐎡𐎹). Two words, both from the same root—just one with a detour via Greek, and the other with a detour via Arabic. Since the Western world was culturally influenced much more by Greece, ‘Persian’ became the standard way to refer to the language in English, and the country was officially called Persia up until 1935, when the Shah formally requested that the original endonym Iran (from Ariya) be used.

In our own language, it’s easy to just call ourselves Irani (ایرانی) and say that we’re living in Iran (ایران), because we’ve done so since early times, but there is quite a bit of debate over whether to use ‘Iran’ or ‘Persia’ to refer to the country in English. Strictly speaking, it shouldn’t be a religious or political debate—it’s actually a matter of geography, in that ‘Iran’ refers to the whole land of the Iranians, whereas ‘Persia’ is arguably just one province—but because of the political changes that came about in the 20th century, the English language has associated Persia with the old Imperial state, and Iran with the new Islamic republic. In a similar way to the Parsi people retaining their original p, Iranians who left Iran before the Revolution (or those sympathetic to the Shah) often call their country ‘Persia’ in English, whilst those who left later (or are sympathetic to the current government) call it ‘Iran’ in English, but this isn’t a hard-and-fast rule.

This debate hinges around two separate words from two separate roots, but the Persian/Farsi question actually concerns two doublets, or etymological twins. Both are legitimate names for the language, but ‘Persian’ is the English name, whilst ‘Farsi’ is the endonym—exactly like ‘German’ and ‘Deutsch’, or ‘Hungarian’ and ‘Magyar’. The Academy of Persian Language and Literature, a governmental branch concerned with regulating the national language (equivalent to the Académie Française in France), issued a recommendation in 2005 that Farsi not be used in European translations, on account of its lack of historical precedence, but this has not been universally adopted by everyone. In popular English usage, ‘Persian’ can refer to the language and to both the Persian ethnicity and Iranian nationality, whereas ‘Farsi’ is only really used to refer to the language, even though in Iran, it’s used to refer to both the language and the ethnicity.

To sum up: there’s no clear-cut answer, and it comes down to preference and which linguistic and historic paths you wish to evoke. The words are pretty much synonymous, but can carry slightly different shades of meaning depending on the speaker and context.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Etymology of 'praise (v.)'

c. 1300, preisen, "to express admiration of, commend, adulate, flatter" (someone or something), from Old French preisier, variant of prisier "to praise, value," from Late Latin preciare, earlier pretiare "to price, value, prize," from Latin pretium "reward, prize, value, worth," from PIE *pret-yo-, suffixed form of *pret-, extended form of root *per- (5) "to traffic in, to sell."

Specifically with God as an object from late 14c. Related: Praised; praising. It replaced Old English lof, hreþ.

The earliest sense in English was the classical one, "to assess, set a price or value on" (mid-13c.); also "to prize, hold in high esteem" (late 13c.). Now a verb in most Germanic languages (German preis, Danish pris, etc.), but only in English is it differentiated in form from its doublets price (q.v.) and prize, which represent variants of the French word with the vowel leveled but are closer in sense to the Latin originals.

Etymonline

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shirt and skirt are doublets: they both stem from Proto-Germanic *skurtijōn. Shirt was inherited. It underwent the sound changes that turned Proto-Germanic into English. Skirt was borrowed from another Germanic language: Old Norse. Here's the finale of my doublets series: Germanic doublets in English.

#historical linguistics#linguistics#language#etymology#english#french#dutch#german#old norse#proto-germanic#lingblr#etymological doublets#old frankish#lombardic#old french

205 notes

·

View notes

Text

There are few ghosts in the sub- section. That is, relatively few words in sub- ever faded out of English after being well established. Most that fell away seem to have been transients and redundant doublets (sublunar / sublunary). What's in a dictionary now under sub- is about all of it there ever was to English.

But buried in the flat loam of sw- are mighty words of the old language. By the end of Middle English or shortly thereafter, they had shriveled into specialization or sunk in provincialism or faded into thin air.

There's swere, a once-common word for "heavy, oppressive; inactive, indolent; loath, reluctant, unwilling." German schwer "difficult" is a living cognate. There's sweve; sweven, the usual words for "a dream/to dream" until dream made an odd shift.

There's swike "deceit, treachery;" swiker "a traitor." There's swink, the old word for "to toil, engage in physical labor;" as a noun "work, effort." Middle English had swinkless for "effortless, free from toil," swinkful "toilsome," handiswink "manual labor, physical work;" Chaucer's plowman was A trewe swynkere, "a true swinker." All gone and forgotten now, but to Chaucer their absences would be holes in the word-hoard.

if you are bored and have a penchant for language or etymology or history or mere poetry, may i suggest the posts on etymonline? they are both informative and poetical, in the purest sense of the word; enlightened meanderings, if you will. they are loosely connected and sometimes scathing, but always valuable and clever with words.

enjoy.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey... sorry if this is too much, but im a baby trans and ive been struggling to grasp the concept what gender is, everytime i try to look for a definition i only find the vague basics like "its what you identify as!" Or i find bigoted shit from trasphobes. If you have any recommendations of essays about gender from trans people who dive deeper unto the concept it would really help. Sorry if im bothering you i just dont really know who else to ask 😅

i don't know how helpful i can be. i have a very instrumental view of transition--i.e., if you think it might make you happier than you are now, you should give it a try and see. i think a lot of pointless verbiage is spilled on trying to nail down difficult-to-elucidate questions about purely internal experiences, about the distinction between gender and sex, and about what all this gender stuff means anyway. i think that stuff can be interesting to discuss, if you like that sort of thing (and i do!) but that loading yourself up with a lot of gender theory isn't actually useful for figuring out what you should do vis a vis your gender presentation and how you identify.

for those latter questions, i think the answer is simple: what makes you happier? when you imagine a given gender presentation, or your body being different in certain ways, or people calling you by a certain name, does that sound appealing? doesn't matter why. if so, go for it! and frankly this advice is quite agnostic of whether or not you're cis or trans. people should adopt the identities that feel most conducive to their happiness. you do not need elaborate theoretical justifications for any of it. anyone who demands an elaborate theoretical justification for how you dress or what name you choose to use or anything like that is an asshole whose opinion you can safely ignore. i guarantee you they are selective in this demand, and are only using it to try to find an excuse to be a dick.

that said, you want a definition of gender, and i guess i can try.

"gender" has no definition. that's not meant to be a smart aleck answer. what i mean is: "gender" is a conceptual category. conceptual categories do not exist outside of our discourse about them. there is nowhere in the world you can go to lay your hands on A Gender. there is no Gender Particle. and while in most philosophical traditions we think of categories as having necessary and sufficient conditions for membership ("a human is an animal descended from the last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees" might be such a taxonomic definition), conceptual categories aren't actually constructed that way. because that's not how the human brain actually works: when you're a kid learning what words mean, you don't learn "a chair is a thing with four legs you sit on." that wouldn't be accurate anyway (a horse is not a chair). you see lots of chairs and pictures of chairs and you form an image in your mind of what a chair is and when you see a thing your brain compares it to other things like it you've seen before, and if it looks like your mental model of a chair, you think, "chair."

(this is in fact how almost all definitions work in practice. even for formal scientific categories for which it seems like a traditional definition might be workable, because our terms are so specific, there are problems and corner-cases. is a HeLa cell a human? it's certainly an autonomous organism. it's certainly descended from the last common ancestor of a chimpanzee and a human being. but it's a single-celled organism that exists only in laboratory cultures, and lacks everything else we expect a human to have.)

so, uh, gender. "gender" is from the latin word "genus" meaning "kind." it is a doublet (that is, shares an etymological origin) with the words "genre" and (more distantly) "kin." obviously, a word's etymology is not its meaning. confusing the two is called the etymological fallacy. but originally when we talked about "gender" we were pretty explicitly talking about categories in general, and i think that's useful to keep in mind. incidentally, "sex" (also from Latin) has a similar etymology--it's related to "section," i.e., the creation of a category by dividing a group. though "sex" acquired something like its current meaning much earlier.

most human cultures group humans into two broad conceptual categories. this is based on a variety of traits, of which physical traits like genitals are seen as frequently foundational. some cultures explicitly create additional ancillary categories, or provide a means to move (often only partially) from one category to another. contemporarily, there has been an effort to distinguish "biological sex" (seen as what chromosomes you have, reflected by what genitals and other physical characteristics you have) from "gender" (seen as a question of social presentation).

i think this is a mistake. you might be able to spot why--biological sex is a conceptual category! most humans are xx or xy, but there is in fact a wide variety of sex-chromosomal arrangements that are possible. xx and xy are only the most common. biology is messy, and it's hard to tell how messy, because we don't routinely karyotype people. the existence of rare-but-noteworthy conditions like complete androgen insensitivity (frequently reuslting in a chromosomal "male" that is "mis"identified as and lives their whole life as a female) highlight that even within the purely biological realm, sex emerges only as two broad clusters, not as two clearly divided bins. moreover, a trans person who has been taking cross-sex hormones for many years is in a sort of willingly-imposed intersex state. so saying a trans woman is a "biological male" or a trans man is a "biological female" (especially if they have had an orchiectomy or hysterectomy and can no longer produce gametes of their respective assigned sex at birth) is sort of funny--we're privileging an (assumed) chromosomal arrangement over the biological facts on the ground. and while DNA does control a lot about how our bodies grow and develop, it can in fact be overridden! otherwise, cosmetic surgery, or hair dye, or LASIK surgery would all be exercises in futility.

"gender" is sometimes also talked about as a set of internal experiences. you "feel like" or "identify as" a particular gender. and while it's certainly plainly true for some people (both cis and trans), it seems not to be true of everybody (cis or trans), and for other people it's hard to say. not everybody has perfect access to their own feelings all the time. people get told they're lying about what they feel when that's socially inconvenient for other people. and internal states are impossible to measure or verify. they're also often pretty hard to put into words, and we mostly can access them only indirectly, by sidling up to them, or by trying to find other people whose experiences/thoughts/feelings seem to resonate with our own.

so i don't have a definition of gender for you, or an etiology, or even a very robust account. sorry! but i also think that anybody trying to tell you they do is operating from an understanding so narrow that they don't even begin to understand its limits.

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

zar "serious"

zar /zar/ [zɑː]

serious, committed, for keeps, risky, undertaken with something staked on the outcome;

purposeful, deliberate, (of an act) not done lightly but instead with full regard of the possible consequences;

meaningful, high-stakes, dramatic, tense, (of a narrative situation) there being a lot on the line that might be lost or not achieved;

competitive, heated, rivalrous, antagonistic, (of a game) characterised by a strong desire to win on both sides or even of outright hostility;

cutthroat, dog-eat-dog, with a ruthless focus on personal gain

also cair zar "to matter, be important, have consequences"

Etymology: from sixteenth-century zar "risky, high-stakes", transferred from the name of a gambling dice game. This comes via Napolitan zara from Arabic زَهْر (zahr) "dice". Doublet of hasart "peril, danger", which comes via French. Used exclusively of games and competitions until the nineteenth century, when the idiom with cair is first attested.

"Cay zar!" dis jo cant corroim nos. /ke zar | dɪz ʒo kant kɔˈrɔim nɔz/ [ke zɑː | dɪˈʝo kan kʊˈʀɔim nɔz] fall serious | say.pst 1s when run-pst-1p 1p "It's not a game!" I said as we ran.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

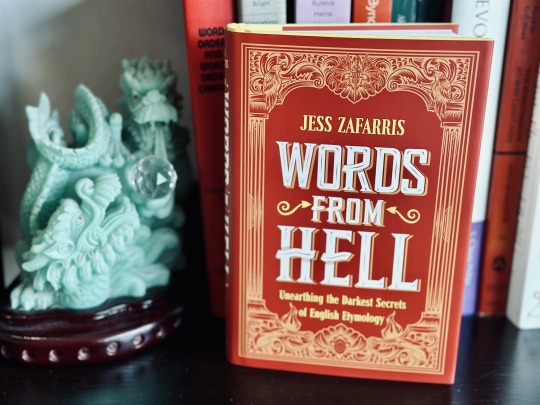

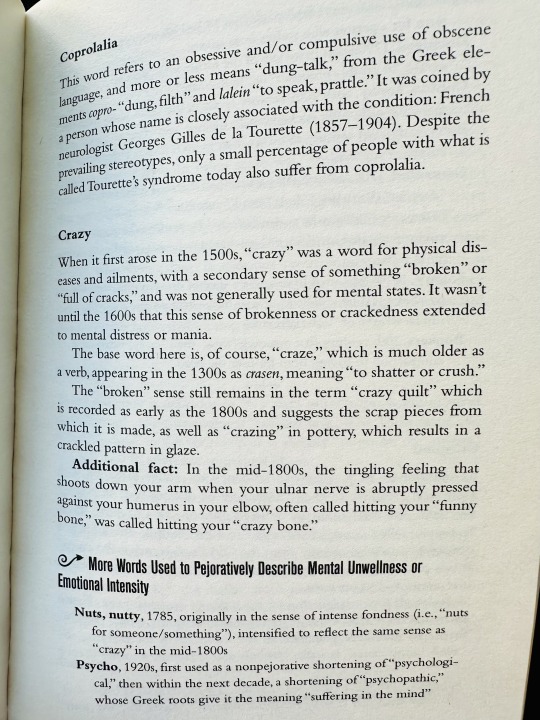

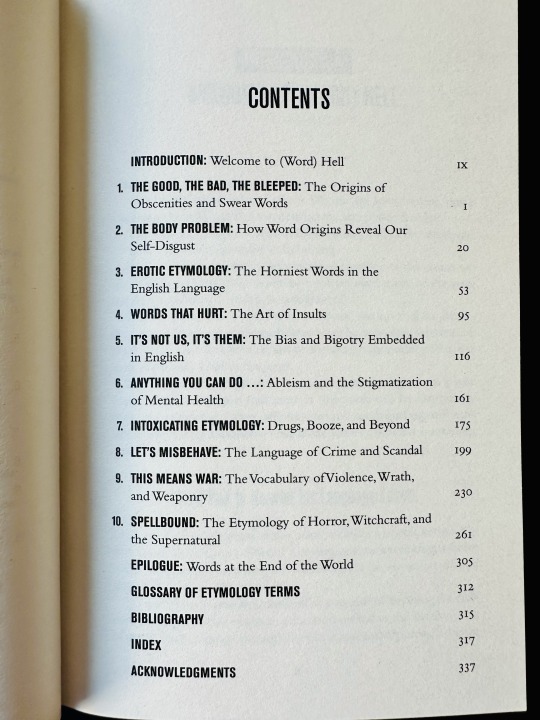

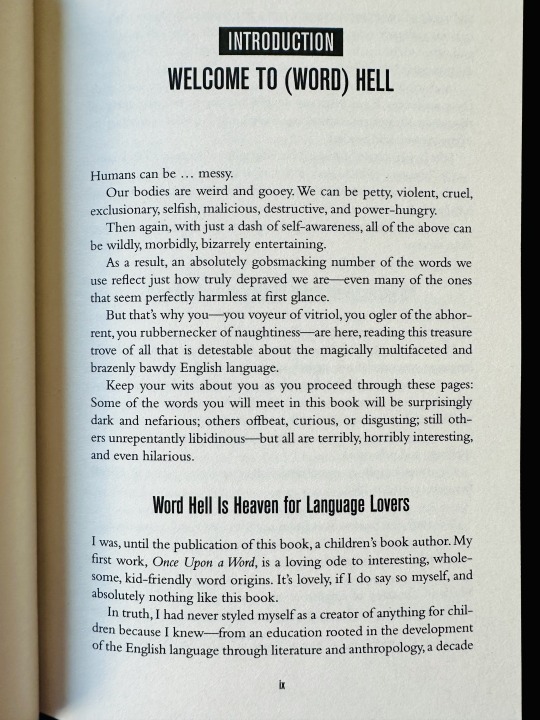

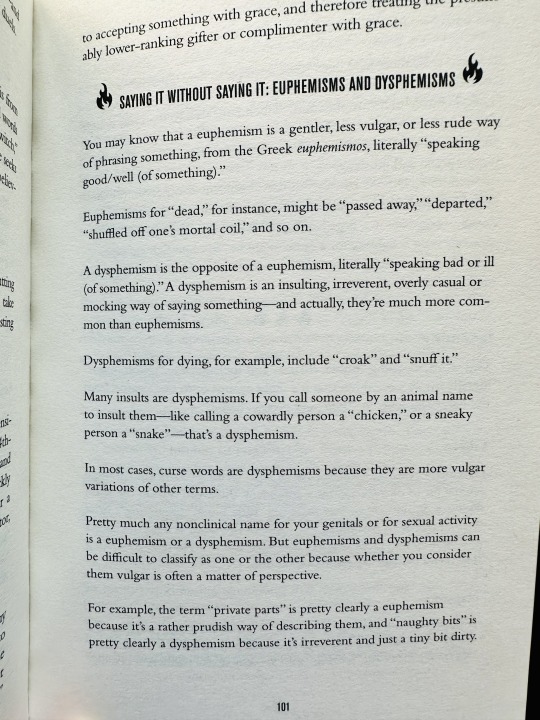

First Impressions: Words from hell

Look what just arrived! So excited to read Jess Zafarris' new book!

Here’s a little preview of what’s inside:

I’m two chapters in so far, but here are my first impressions:

I love the range of topics covered, from obscenities to ableism to the violence of war—a reflection of the fact that “Humans can be … messy. […] We can be petty, violent, cruel, exclusionary, selfish, malicious, destructive, and power-hungry. […] As a result, an absolutely gobsmacking number of words we use reflect just how truly depraved we are—even many of the ones that seem perfectly harmless at first glance.” Jess fearlessly illuminates all aspects of the dark underbelly of the English language.

Words from hell includes a number of fun asides, where Jess delves more extensively into certain topics or pulls together words on a similar theme—such as a digression on the connection between shit and science, or the origins of words for farting.

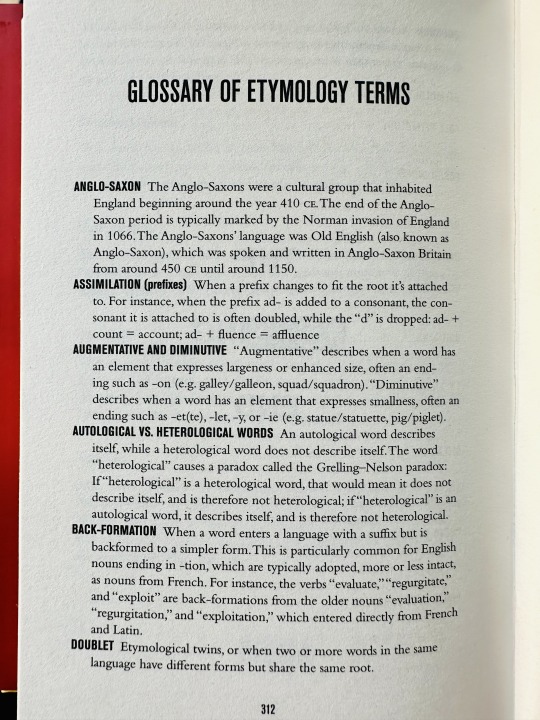

Also extremely useful for casual lovers of language is a glossary of etymology terms at the end of the book, explaining that a doublet is when two different words in the same language derive ultimately from the same root, or that Proto-Germanic is the reconstructed language from which all the Germanic languages (English, German, Dutch, Swedish, etc.) developed.

Right from the outset, I love the lighthearted, curious, and unabashed style with which Jess unearths the dirtiest words of English. You can tell she has as much fun using the messy treasure trove of English words as she does researching them, and it makes the book a joy to read. I’m excited to finish it!

Preorder your copy here!

64 notes

·

View notes