#especially with cisgender heterosexual men who perceive me as feminine

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

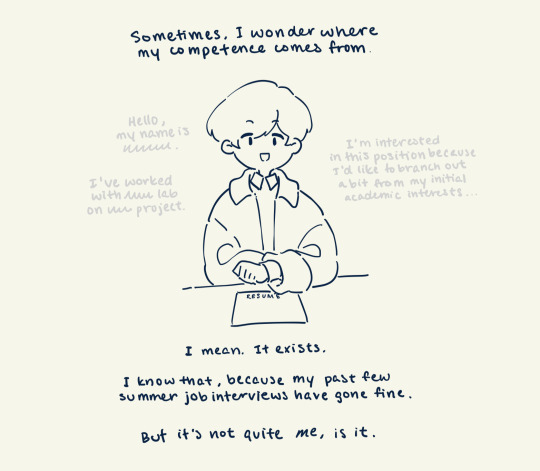

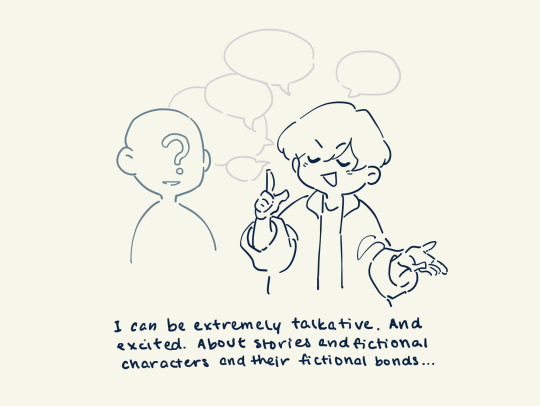

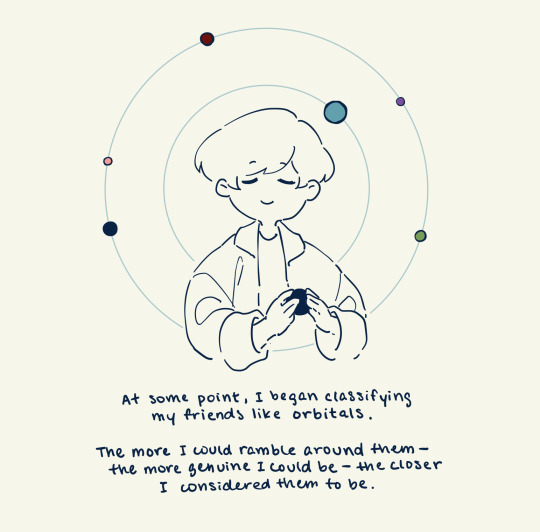

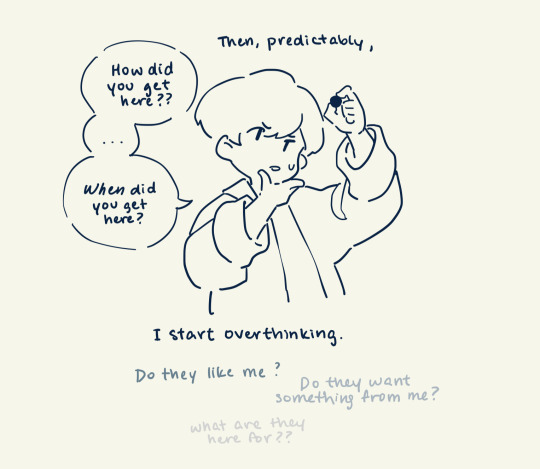

Recent thoughts on my social relationships

#reason number 2 for my massive third term burnout! social relationships#especially with cisgender heterosexual men who perceive me as feminine#and my overthinking of whether they have approached me for ulterior motives or actually genuinely enjoy my presence and my thoughts

539 notes

·

View notes

Note

Thank you for sharing your introspection on this post (for those who missed it): https://at.tumblr.com/marvellovelacevt/707838783056461824/8o6fu1lv0bbf

I found this very intriguing! So, do you feel like there's a lack of more precise labels to cover your experiences and identity? Or is it a lack of representation of your experiences and identity? If that made sense. As in, is it hard for you to find people who speak of experiences and identities that *match* yours?

"Is using catch-all labels like 'non-binary' or 'queer' hampering my ability to understand who I am as a person?"

—I thought this was really interesting. In cultural anthropology (I only took a beginner course, so I'm not speaking as an expert), there's discourse of whether language determines a group's culture or if culture determines a group's language. What you just said makes me think of that very thing, as it sounds like language is shaping the "culture" (though in this case, I'd say your "understanding") of your identity, whereas your identity should be shaping the language.

i'm glad it interested you!

so, my relationship with my gender, sexuality, and self-image is really really complicated. it's less that i want a precise label for my identities and more that i don't want to have to use a label at all while still having control of how my identity is perceived. my identity is really hard for me to put into words sometimes even when they should feel concrete!

the term nonbinary can spark a lot of speculation about an identity when you lack a precise label. nonbinary is an umbrella, after all. there's a belief held by a lot of people that nonbinary is "diet woman", when that's demonstrably untrue as a whole and especially for me. if i'm thinking as my identity as a set of sliders, the slider for my internal identity skews very slightly masculine of center. but then, my outward appearance doesn't reflect that, and i don't want it to. presentation-wise, i skew more feminine. naturally, people are going to see me as "diet woman", and for that, i can't fault them. but they're objectively incorrect about their assumptions!

my gender is quite possibly the most difficult thing about myself to truly define because when i look at more precise labels, none of them reflect how i feel, because when i think of gender, i break it down into several parts; the internal, the presentation, and the performance. the performance aspect of my gender is the most unknown to me because i don't really register how i act at all. i am a blind spot for my perception. it doesn't help that because of One Very Specific Mental Illness I Have But Will Not Disclose, i tend towards being a social chameleon.

my sexuality is easier for me to place, but it's still very messy to define. in short, i guess that, on paper, i am biromantic and demisexual. i resonate with those experiences the most. but also... i don't? not entirely.

it's less an attraction to specific genders that i feel and more an attraction to queerness in every aspect. i consider myself t4t as long as i've gotten to know someone. especially in regards to other nonbinary or gender non-conforming people. when i think of the possibility of dating someone who is cisgender or when a cisgender person takes an interest in me, i feel like something hits a panic button inside of me and i feel like i have to leave the situation immediately. this happens most often with cisgender and heterosexual men, but it happens regardless of whether it's a cis man or woman and regardless of sexual or romantic orientation. it mostly ends up being a circumstance of cishet men being very common to encounter and them seeing queer, vaguely feminine people as something interesting and fun.

and so that's why i say i'm queer and not biromantic demisexual. but then, that also feels like a cop-out?

i have a lot of thoughts and feelings about my identity and i wish i had a better word for it for convenience. a label is convenient. but i also wish i didn't have to want a label for that convenience and that i could exist using broader labels without feeling like my identity is speculated about or doubted, you know? like personally i think "unlabeled" as a term/label fucks hard but then it also has a reputation of celebrities using it to foster speculation and parasocial relationships with their fanbases and then feeling it gives them a free pass to comment on queer issues or queer media in a way that makes them look really close-minded (not naming names. if you know you know.)

so, i guess my introspection is more about exploring why i feel like i have to need labels in the first place.

#answered#long post#queer stuff#queer#nonbinary#headless hodgepodge#sorry this took so long to answer sfdghdfgh#just trying to articulate my thoughts yk

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay, so I like queer!Johnny and l@wrusso just as much as anyone, but lately I’ve been having some thoughts about the way media and fandom frames violence in men as an indicator of potential queerness. Particulary on the way this can sometimes change how people interpret classic macho behavior, such as misogyny or agressiveness.

Despite the stereotypes that exist about gay men being more feminine, there’s also this narrative in our culture that men who are aggressively masculine, especially if is in a way that’s harmful to others or themselves, are probably acting out because of repressed homosexuality or queerness. This is easy to observe in media: there’s the trope “Armoured closet man”, and Rantasmo mentions some examples in his video “The homophobic hypocrite”. And like he explains, this is something people sometimes apply to real life situations. For example, I have a friend who is usually pretty chill about engaging in gay behavior with other dudes for the laughs, and one day he was discussing it with a friend and they were like “Yeah, we don’t care. Some people care too much about appearing gay and we know why”. This idea it’s not limited to men: you can also find it in Lily Singh’s video “A Therapy Session For Homophobic People” where the homophobic lady ends up asking her out. Those are the first example’s I could remember, but there are more.

I’m not saying it’s not something that happens. Obviously, being homophobic or being conservative about gender roles does not guarantee that someone’s straight or cis. We were all raised in a homophobic, heteronormative society, after all. I was, at some point, scared of being gay. And I understand where the specific connection comes from: sometimes when you’re guilty or ashamed of something, you lash out more easily. That’s why there’s such a complex relationship between repression in queer men and violence: if you can’t express your desires in a healthy way, that can lead to channeling those feelings into aggression, which is more “socially acceptable”.

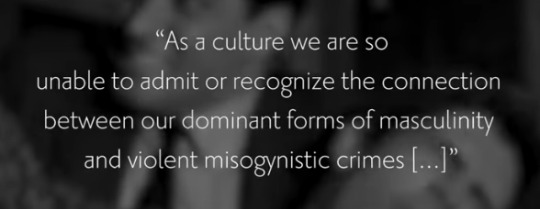

So it’s not automatically wrong to make the connection. What’s been bothering me lately is how interpreting homophobic, misogynistic, or just generally violent behaviors as secondary effects of repressed queer desire sometimes suggest that homophobia or misogyny are not enough on their own. Just like my friends said that one time: if you’re a man and you’re homophobic, it has to be for a reason. And that reason is not that you live in an homophobic, misogynistic society that makes you hate queer or feminine people, it has to be something particular about you that makes you more susceptible to those ideas.

The thing is that this is pretty convenient for cishet, conventionally masculine, men. It ends up suggesting is that homophobia, misogyny, aggression or other harmful attitudes have actually nothing to do with hegemonic masculinity. It’s only when men don’t fit into this ideal that these toxic behaviors start leaking out. And it’s not just convenient for them as individiduals, it also absolves our culture; if it’s the result of a particular experience, we don’t need to start thinking too hard about how our gender roles affects us in general.

Which reminds me of a video I saw recently, by Lindsay Ellis. She’s discussing transphobia in film, but there’s this moment when she’s talking about the movie Psycho, and she mentions Ed Gein, the real life version of Norman Bates. Apparently, he was originally presented in the media as a man who had unresolved queer tendencies, which served as an inspiration for the character in the film. But. That was a lie. There was no evidence that this was actually true for Ed Gein. As far as everyone knows, he was a straight cisgender man who killed women. And she brings up this quote, from Richard Titthecott, “Of men and monsters”:

So, the video is specifically about the perceived relationship between serial killers, trans women, and how this relates to transphobia. And I was talkig about seeing agressively masculine men, so I know it’s not exactly the same thing. But I keep thinking about that and about what Rantasmo said on his video. He goes from talking about canonical homophobic queer characters to talking about real life situations. And he mentions how sometimes when a homophobic hate crime takes place, people start speculating about whether or not the killer in question is queer himself, often implying that maybe it wasn’t really an explression of homophobia, but an example of the self-destructive tendencies of gay people. What he concludes is that this idea of the “homophobic hypocrite” is often used to “push the responsibility of homophobia and hate crimes off of heterosexuals and on to the victims”.

While these examples have to do with particularly strong forms of misogyny and homophobia, it’s not out of the question to consider how this relates minor forms of violence.

All of this is just about Thoughts. I’m not going to reach any conclusion here, because it’s impossible. Especially when it comes to what is and isn’t a Good or a Bad headcanon or ship. Like I said at the beginning, those ships can be fun and can be interesting for many reasons. I just want to think about the things that may be influencing my interpretations of a story without my knowledge. If we start to believe that just living in a world where you know that being a straight man gives you certain privileges over women and queer ppl is not enough to be hateful towards them, it becomes harder to hold privileged people accountable. Or to explore how those privileges work and why they are put in place. Obviously, there are many ways to talk about this topic, and people can be more than one thing. A man can be queer and misogynistic for example, both privileged and opressed. I don’t know.

Basically, I’m just going to end this post by saying that the idea that “queer interpretations of mainstream media are a way to expand the narrative and include ourselves in the stories we love, and these interpretations are often mocked or rejected by mainstream writers and audiences that think that labelling something as gay is insulting, so they often go against the current” can coexist with the idea that “interpreting homophobia, misogyny, aggression or other harmful attitudes as indicators of potential queerness can be pretty convenient for straight cis conventionally masculine men, and also the association between queer men and violence and self-destructive tendencies is really prevalent in mainstream media and in our homophobic culture”. ???

??????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????

#cobra kai#queer stuff#karate kid#johnny lawrence#oh and as usual: my native language is not english. please let my know if something sounds weird#i don't know how to feel about this#that's the only conclusion i have#i guess i just keep comparing this to everything i feel about daniel and mr miyagi and all those movies that portray a more tender version#of masculinity and how they relate to queerness#and i've been feeling a lot closer to that lately#i still haven't recovered#at the same time i still#like those interpretations that are like#this man is clearly obsessed with appearing masculine so we don't know who he truly is#and also jeff winger is gay. i'm almost 100%.#also repression is a relatable experience as a fellow queer#but i just#i don't want to absolve misogynistic homophobic men is the thing

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve identified as straight, I’ve identified as gay, and I’ve identified—and still identify—as bi. My sexual identity is something of a shapeshifting mass that I can never quite firmly grasp. In the minds of many, I’m confused. But I don’t see it that way. I’ve always been confident in my sexual orientation; it’s just changed over time. For the majority of my life, I was solely romantically and sexually linked to women. But in my late 20s, I started to experiment with men (something I’ve wanted to do for a long, long time) and really liked it. Now, I’m far more attracted to men than women, but who’s to say my sexual preference won’t sway again?

“It’s not uncommon for people’s sexual identities to change,” sex educator Erica Smith, M.Ed, tells NewNowNext. “I know this as a sexuality educator and because I’ve experienced it firsthand. I’ve identified as bisexual, lesbian, queer, and straight (when I was very young). It wasn’t until I was in my mid-30s that I relaxed into the knowledge that my sexual attractions are probably going to keep changing and shifting my whole life.”

According to Alisa Swindell, Ph.D. candidate and bisexual activist, it is not always our sexuality that changes. Usually, it’s our understanding of our sexuality that evolves when we explore what feels right to us. “Our understanding of gender and how it is expressed has been evolving at a rate that has not previously been known (or studied) and that is changing how we understand our own desires and responses to others,” she says.

Many outside factors can influence our sexuality. For instance, Swindell thinks many bisexuals are playing against a numbers game. “There are more people with other gender attractions than same-gender, so more often bisexual people end up in relationships with people of another gender and find it easier to pursue those relationships,” she says.

In her opinion, this sentiment is especially true for women, as there is still a lot of stigma toward bi women within lesbian communities. Men, however, experience a different set of challenges.

“Once [men] start dating [other] men, they often find themselves in social situations that are almost exclusively male and so meeting women becomes harder,” she adds, effectively summarizing my lived experience as a sexually active bisexual man. “Also, those men, like all of us, were socialized to respond to heterosexual norms. So many men who enjoy the queerness of the male spaces are still often attracted to heteronormative women who do not always respond to male bisexuality due to continuing stigma.”

The continuing stigma often pressures bisexuals to adopt a monosexual identity. Take Leslie, a “not super out” bisexual, as an example. Leslie dated a woman from her late teens to early 20s, keeping her sexual orientation a secret because her parents were conservative and she didn’t want to ruffle any feathers. As she revisits her past same-sex relationship with me, she has a realization: “In reflecting on all of that, I think deep down I thought that being with a man would just be easier.”

Now married to a man, Leslie feels like she’s lost her bi identity, though she’s still attracted to different genders. “When I see people I follow online and find out they are bisexual I usually reach out and say, ‘I am, too!’ so I can collect sisters and brothers where I can,” she adds. “Otherwise, as I am cisgender-presenting I often feel like I don’t really have a say but I offer my support.”

This loss of identity is all too common. “Maintaining a recognized bisexual identity can be difficult as monosexuality is still the assumed norm,” Swindell says, noting that showing support—whether that looks like keeping up with issues that affect bisexuals, correcting people who mistakenly call bisexuals gay or straight, or encouraging our partners to not let that slide when it comes up with friends and family are all important for maintaining an identity—as Leslie has, is important to maintaining a bi identity. Smith adds this loss of identity may be attributed to a person’s own internalized biphobia, too.

“When it comes to sexuality in particular, there is rightfully a lot of autonomy given to people to self-identify. If someone self-identifies as queer or bisexual, none of their sexual or relational behavior, in of itself, alters that,” psychotherapist Daniel Olavarria, LCSW, tells NewNowNext. “Of course, there is also a recognition that by marrying someone of the opposite sex, for example, that this queer person is exercising a level of privilege that may alter their external experience in the world. As a result, this may have implications for how that person is perceived among queer and non-queer communities.”

Jodi’s experience as a bisexual person is more reflective of my own: She shares that she’s gone through stages where she only dates men, and others where she only dates women. Available studies suggest that only a minority of bisexuals maintain simultaneous relationships with both genders. In one report, self-identified bisexuals were asked if they had been sexually involved with both men and women in the past 12 months. Two-thirds said yes, and only one-third has been simultaneously involved with both genders.

As for a possible explanation? “It can be really difficult for us to find partners who are comfortable with us dating other genders at the same time,” Smith offers up as a theory.

“If I’m in a situation where I have to be exhibiting a lot of ‘masculine’ energy (running projects, being very in charge of things at work, etc.), then I tend to want to be able to be in more ‘feminine’ energy at home,” Jodi adds, clarifying that people of any gender identity can boast masculine and feminine energy. “Likewise, if my work life looks quieter and focused on more ‘feminine’ aspects such as nurturing and caregiving, I tend to want to exhibit a stronger more masculine presence while at home.”

Bisexuality is, in many ways, a label that can accommodate one’s experience on a sexuality spectrum. This allows for shifts based on a person’s needs or interests at any given point in their life. Perhaps “The Bisexual Manifesto,” published in 1990 from the Bay Area Bisexual Network, says it best:

Bisexuality is a whole, fluid identity. Do not assume that bisexuality is binary or duogamous in nature: that we have “two” sides or that we must be involved simultaneously with both genders to be fulfilled human beings. In fact, don’t assume that there are only two genders.

Sexuality is complicated, and how we experience it throughout our lives is informed by a multitude of different factors—the exploration of power dynamics, craving certain types of sexual experiences, and social expectations can all influence our gender preferences at any given time, to name just a few. Much like our own bodies, our understanding of our sexual orientation will continue to grow.

I’ve come to accept this ongoing evolution as a wonderful and inevitable thing. Imagine having a completely static sexual orientation your entire life? Boring! Being able to explore your sexuality with wonderful people of all genders is intensely satisfying and uniquely insightful, no matter how many others try to denounce what you feel in your heart or your loins.

I didn’t choose the bi life; the bi life chose me. And I am grateful.

#bi tumblr#lgbtq pride#bisexuality#lgbtq community#bi#lgbtq#support bisexuality#bisexuality is valid#pride#bi pride#bisexual education#bisexual nation#bisexual youth#bisexual tips#bisexual info#bisexual rights#bi+#bisexual activism#bisexual community#support bisexual people#respect bisexual people#bisexual#bi youth#bisexual life#bisexual pride#proud bisexual#bi positivity#bisexual injustice

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

TW; Abuse, mental illness, intimate partner violence, death ment. Update Post

I think one of the worst things about being a writer are those days when you sit for hours in front of a blank piece of paper or a blank screen and not knowing if you'll ever write again. It's confession time, though I'm sure you're all aware, I'm incredibly mentally ill. I'm currently being assessed again, but previous diagnoses include Schizoaffective Disorder, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, Chronic Depression, Attention Deficit Disorder, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, and possible Borderline Personality Disorder. I also live with a mild processing disorder and an auditory processing disorder. You may be thinking right now, "ah yes, the tortured writer! This must be excellent for your writing!" It's more complicated than that unfortunately. I live my life constantly walking along a tightrope, only there is no safety net and everything is on fire around me. When it comes to writing, mental illness and trauma become a double edged sword. On one edge, my writing is best when the depression begins to slow loop its noose around my neck. On the other edge though, it becomes so bad that I begin to choke and eventually stop functioning. I can do nothing nut lay in bed and sleep for days on end, unable to move or even breathe. In those moments I feel like I might be better dead than alive. I'm not suicidal, don't worry, just more at a loss with what to do with myself. I stop posting on my blogs, I don't write, I'm not even able to talk to my partner. Sometimes it's paralyzing, like my body is frozen up. It makes writing hard.

I'm in one of these slumps right now, my writing practice has been disrupted entirely. The first time I've done any new writing was last night around midnight. I tried to replicate a poem that had been lost by rewriting it and got something entirely new. It was refreshing and helped to get out some of the feelings I have been dealing with as of late. I want to explore more what it's like being in love as an abuse victim and going from a relationship or relationships where your ex-partner was cruel and emotionally abused you to one where your partner wants to communicate with you and do things for you and with you. It's a strange feeling and I'm trying to capture that in my poetry right now, where your automatic response is to put up walls and attack and fight, but you no longer have to, there's nothing left to defend yourself from and it's strange and confusing and honestly a little terrifying. My current partner is the inspiration behind the new lover, they would move mountains for me and I for them. I want to capture that through conversation poems, where the speaker of the poem the "I" is on the left when speaking with their thoughts centered. What their partner responds with is on the right. I hope to capture the gentleness of the partner in their words as well as the protectiveness and love they feel for the speaker. With the speaker, the "I"/person speaking on the left, I want to capture the thoughts of a person who has been groomed and gaslighted and manipulated into a certain way of thinking and perceiving the world. The partner acts as a grounding mechanism in the poem, a way to remind the speaker that she/they is safe and doesn't have to fall back on the behaviors, thoughts, and feelings the abuser forced onto her/them. I want to explore this through characters from pop culture who have been in canon or implied abusive relationships, exploring the different ways abuse affects us and the different ways abuse can manifest as well as the different ways we heal as survivors of intimate partner violence. I want to give survivors a voice who aren't your typical cisgender, heterosexual, feminine, white women. We so often forget queer women, men, butch/masculine presenting women, trans people, and women of color, who all face different barriers in getting help for being abused, especially when that narrative doesn't fit what society deems the "ideal" victim. I want to remind people that not all abusers are cisgender, heterosexual, overly macho men. Sometimes it's a small, feminine woman who beats on her butch girlfriend that's six feet tall, sometimes it's a bisexual woman who has been groomed so much she keeps going back to her abusive ex before escaping again, sometimes it's a cisgender, heterosexual man whose girlfriend is constantly micromanaging his life and hits him every time he even looks at another woman or feminine person. Every survivor deserves a voice, regardless of race, gender, sexuality, gender expression, class, religion, ethnicity, and political leaning. I want to be there for the victims and survivors you who are thrown under the bus, I want to give us a voice.

I'm sorry this was so heavy y'all, I'm going to try to start maintaining this blog again and post some of the work I'm working on and have been working on. If you're a survivor of intimate partner relationship violence, check back soon, I'm going to put up a page with hotlines for survivor as well as links for information about power dynamics that aren't just geared towards your typical narrative seen in the media. If you have any info you think would be helpful, drop a link/name of the organization in my submissions box and I'll add it to my list!

J.R. Morris

#domestic violence#ptsd#abuse#survivor#writers of tumblr#JR Morris writes#tw domestic violence#tw abuse#tw mental illness#mental illness#tw death#mental health#domestic violence awareness month#I stand with all survivors

1 note

·

View note

Text

Bi, Bi, Bi: Bisexual Invisibility in the Philippines

by Jessica Alviz

History and Background

Bi Flags at the NYC Pride March from Medium

In this more progressive world, people are increasingly letting go of traditionalist views and accepting that the world is not in black and white: Caucasians are no longer deemed as the superior race, it is now relatively acceptable for boys to wear skirts and makeup, and girls who like girls and boys who like boys? Completely normal. However, the world isn’t as pleasant for those who like both. Until today, bisexual erasure and invisibility remains a problem. Bisexual erasure is when “the existence or legitimacy of bisexuality (either in general or in regard to an individual) is questioned or denied outright” (GLAAD, 2014). Bisexuals have described their experience as being neither here nor there, as they are attracted to more than one gender. Others—whether they are heterosexual or from the LGBTQ+ community themselves—have thought that bisexuals are either not straight enough to be gay, or not gay enough to be straight. A bisexual has narrated about this cognitive dissonance in Bisexual Blues (Hase, 2005) stating that she finds it easier to define her sexuality through the people that she dates, and because she is dating a man, she feels as if she does not belong in the LGBTQ+ community, because she is deemed as “straight.” She mentioned that she “feels as though she has to exchange an entire community to be with one person.” Furthermore, bisexuality is commonly described as a “phase” for people before fully discovering that they are actually either gay or lesbian (San Francisco Human Rights Commission, 2011). Some even believe that bisexuals are actually just heterosexuals who are experimenting with their sexuality (Serano, 2010).

The marginalization of bisexuals within the LGBTQ+ community is not new: during the first LGBTQ+ movements, bisexuals were excluded because they were being accused of “reinforcing the gender binary” (Serano, 2010). Serano states that this discrimination is not surprising. Because bisexuals can be attracted to the opposite gender, homosexuals find the existence of bisexuals threatening to their own identity. This is due to the heteronormative notion of homosexuality being phase and the notion that homosexuals can become straight if they try. This also explains why bisexuals are accepted only conditionally in the LGBTQ+ community. For instance, if a bisexual man is in a relationship with another man, he is included in the community. However, once that bisexual man dates a woman, especially if this woman is cisgender (identifies as the gender they were assigned to at birth), the man would be ostracized and marginalized.

Philippine Context

Although the LGBTQ+ community is slowly getting more recognition in the country, bisexuals remain invisible. This is most probably due to the following reasons: first, majority of Filipinos hold traditional and conservative views rooted in the teachings of the Catholic Church. Second, the Philippines has its own cultural perceptions about the LGBTQ+ community.

Homophobia is not as widespread or intense as one would expect of a predominantly Catholic country. However, Christian views on homosexuality remain almost adamant. After all, in theory, Catholics believe that following the Church’s teachings is key to being a good member of their religion, and the Church portrays homosexuality as something immoral. Sharing the Bible’s heteronormative outlook and existing gender order, the Church views homosexuality as an ethical concern, a medical condition, and/or a sexual misidentity (Joaquin, 2014). Though homosexuals are not outright excommunicated from the Church, they are discouraged from acting on their homosexual desires. Homosexuality is treated as something that needs to be corrected or cured, and the Church uses prayers, sacraments, celibacy, and guilt in order to “fix” a person’s homosexuality. And because bisexuality, in simplest terms, can be understood as being straight and gay at the same time, of course believers of the Catholic Church would urge bisexuals to “turn” heterosexual.

Vice Ganda from ABS-CBN

With the Church’s dominant ideologies of heteronormativity, as well as the Western dichotomous view on gender and sexuality brought about by the Spaniards (de Jong, 2017), there is a good amount of cultural shame linked to being homosexual in the Philippines. In the first place, there are no Filipino terms for “sexuality,” nor categories for sexual orientation (Ceperiano, Santos Jr., Alonzo, & Ofreneo, 2016). There are only street words--which might even be considered as derogatory--to describe such categories, because homosexuality is not talked about at all (Joaquin, 2014). Furthermore, the concepts of sexuality and gender are merged. While the Westerners’ concept of a gay man is a man who is sexually attracted to other men, it is not quite the same for Filipinos. In the Philippines, the closest local term for “gay” is bakla, which is an effeminate man attracted to other men (de Jong, 2017). The bakla is even often described as “having a woman’s heart stuck in a man’s body,” a representation much closer to the Western concept of a transgender rather than a gay man. The concept of bakla is also heavily attached to certain stereotypes, most of which come from mainstream media (Justiniani & Sierras, 2015). Typically, the bakla is portrayed as a man who dresses and acts like a woman, a flamboyant and theatrical man, or comic relief. This entertainment factor of a bakla--seen also in the most prominent bakla figure in the Philippines, comedian Vice Ganda--is perhaps one of the reasons why they are tolerated in the society.

The Philippine concept of a lesbian is also mixed with gender expression. The local term for this is tomboy, which, from the name itself, is also attached to the image of a masculine woman (Tiempo, n.d.). A tomboy is characterized by being boyish, tough, and manly, with cross-dressing as a major feature of their personality. Compared to the bakla, they are not as present in Philippine media.

Butch (Masculine Lesbian) and Femme (Feminine Lesbian) Wedding Picture from Pinterest

Given these, the only Philippine concepts for gays and lesbians are stereotypes. Once they act outside of these societal expectations, they are not considered socially acceptable. This is also possibly due to the heteronormative beliefs that the country has. Heteronormativity is the concept in which heterosexuality is the norm and homosexuality is deviant (Joaquin, 2014). To justify homosexual relationships, the Philippines has attached gender to sexuality. This enables homosexual relationships to fit into a heteronormative standard: because the bakla is effeminate, and the tomboy is masculine, the concept of a man and a woman in a relationship still exists if the bakla or tomboy’s partner is of the opposite gender expression.

Since Philippine homosexuals are subjected to this stereotyping, it is only natural for those that lie in between the homo-hetero spectrum to be the same. The Philippines already has misconceptions about homosexuals themselves--what more for bisexuals, those who love both? They have no concept of this at all, evident in how there is general confusion about who Filipinos perceive as bisexual (Tan, 1996). Sometimes, gay men identify as bisexual even though they are only attracted to men to indicate that they are the “straight-acting” type of gay. Bisexuality is not a concept written into Filipino language and culture. An example of bi-invisibility is in the following passage:

Sam (24 years old, F): Sam’s mother, upon hearing about how her boyfriend sexually abused Sam, told Sam that her boyfriend would not harass a “lesbian” like Sam even though Sam explicitly came out to her as bisexual. Sam’s friends also ask her questions like “Why can’t [you] just date a guy” and “Why can’t [you] just date a girl?” (International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission, 2015), implying that they only consider “lesbian” and “straight” as the legitimate sexual orientations.

There is also a lack of research about bisexuals in the Philippines, as seen in how there is a lack of data and respondents in interviews (Rainbow Rights Project, 2014). Available research is primarily about gays or lesbians. To make up for the lack of available research, short interviews were conducted with teenage Filipino bisexuals. The questions in the interview mainly focused on perceptions about being bisexual, bisexual acceptance, and bisexual visibility.

Several of the respondents mentioned that there have been times when their bisexuality was accused of being a phase, or otherwise an illegitimate sexuality. A participant said that when she came out to her peers, they did not believe her at first, as she had only ever talked about her male crushes around them. They even accused her of only calling herself bisexual for the sake of being trendy, as she mentioned her sexuality when “coming out videos” were popular. Another participant, who came from an all-girls high school, mentioned that when she talked about her female crushes, her friends would merely laugh along but insist that it was merely a phase and that she would become more attracted to men in college.

A respondent mentioned that due to the notion of bisexuality being a phase, she herself found it difficult to accept her sexuality:

My acceptance of my bisexuality was difficult because I feared it would mean that my identity up until that point would be rendered invalid. So in the past, when people were doubtful about my sexuality, it was because people didn’t think I was gay, and it made me very conflicted because I had a feeling they were somewhat right. Deep inside, I still feel like it’s a bit of a loss that I accepted being bisexual, and that currently I’m dating a guy. But I always tell myself that my sexuality is a part of a spectrum, and that I don’t have to prove myself to anyone. I understand my sexuality, and that is enough.

Again, it can be seen that there is cognitive dissonance: this bisexual is defining her sexuality through external factors, i.e. the person that she is currently attracted to at the time. There is confusion because of the false sexuality binary that was socially constructed by people, leading them to believe that one can only either be gay or straight.

As for the visibility of bisexuality in general, the respondents agree that it is not acknowledged much. One respondent mentioned that most people are skeptical about bisexuality, often saying that it is not a legitimate sexual orientation and that bisexuals are merely “confused” about their “real” sexuality. Another participant said that she feels that bisexuals are not represented enough in media--the LGBTQ+ community in general is underrepresented, but she mentions that compared to the more “definite” sexualities of gays and lesbians, bisexuals are barely seen on television and film. A third respondent lamented the extreme underrepresentation of bisexuals. She said that even in a school as liberal as the University of the Philippines, being heterosexual is the norm (it is a co-ed school after all). She also mentioned the situation of the LGBTQ+ people: “If people are gay, they either represent a spectacle or the movement. There’s no in-between region for bisexual people, we’re not defined by a certain institution [and] not even by a stereotype.”

The participants had differing views about the situation of bisexuals in the Philippines. When asked if bisexuality is accepted or at least acknowledged in the Philippines, a respondent mentioned that it is acknowledged but not accepted. She blames on the patriarchal and traditionalist values that majority of the country hold. Another participant agreed with this, saying that it is not accepted, though she says this is mostly due to Catholicism. She also said that it is mostly the older generations that do not tolerate it; most of the youth are more accepting towards bisexuality, which she correlates with awareness gained from social media as well as general open-mindedness. A third also shares this sentiment, saying that acceptance of the LGBTQ+ community in general is conditional: “ I have noticed the trend wherein we need to be beneficial for straight people for them to accept us. Our LGBT members to compensate more by being funny or being the fun friend.” This is in line with the aforementioned “entertainment factor” that is promoted by Vice Ganda.

One participant, however, says that bisexuality is not acknowledged at all: bisexuality is hardly a topic even in gay organizations, and bisexual representation in pride marches is minimal. She says that in general, people are unable to comprehend bisexuality, as they believe that it is merely a sexuality used as a label for justifying promiscuity. Another respondent echoes this:

Bisexuality is not entirely accepted. In my opinion, many don’t even understand what it means. The culture in the Philippines towards LGBTQ+ is more tolerant than accepting, and this leads to ignorance or apathy towards the community. Here, mostly gays and lesbians are the emphasized and known orientations, and this selective knowledge begets ignorance towards the feelings towards bisexuals, which may affect one’s perceptions about validity.

youtube

Bi the way, we exist | Viet Vu from Youtube

Conclusion

The fight is not quite over yet. Despite the LGBTQ+ community's growing acceptance, they remain marginalized in society, having to fit into the expectations that Philippine culture imposes on them. Furthermore, with only the recognition and focus on gays and lesbians, the “singular” sexual orientations, other sexual preferences are left in the dark, particularly bisexuality.

Because of the heteronormative and dichotomous view on gender and sexuality, bisexuality is, if not ignored, misunderstood. It is not seen as a valid sexual orientation and is typically accused of being an excuse for promiscuity, a confused sexuality, or the stepping stone to being “fully gay.” The Philippines still has a long way to go before everyone becomes truly free. I am unsure if will be around to see it, but as someone who also loves regardless of gender, I will gladly join the fight.

References

de Jong, A. (2017, February 15). Bakla. The creation of a Philippine gay-identity. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/5155866/Bakla._The_creation_of_a_Philippine_gay-identity.

GLAAD. (2014, September 19). Erasure of Bisexuality. Retrieved from GLAAD: https://www.glaad.org/bisexual/bierasure

Hase, M. (2005, November-December). Bisexual Blues. Off Our Backs, pp. 18-19.

Joaquin, A. (2014). Carrying the Cross: Being Gay , Catholic , and Filipino. Sociology and Anthropology Student Union Undergraduate Journal. 1 (2014). 17-28. Retrieved from http://summit.sfu.ca/item/15203.

Justiniani, B., & Sierras, N. (2015, August 13). Has love really won? Retrieved from The Lasallian: http://thelasallian.com/2015/08/13/has-love-really-won/.

Serano, J. (2010, October 9). Bisexuality does not reinforce the gender binary. Retrieved from The Scavenger: http://www.thescavenger.net/sex-gender-sexual-diversity/glb-diversity/467-bisexuality-does-not-reinforce-the-gender-binary-39675.html.

San Francisco Human Rights Commission. (2011, March). Bisexual Invisibility: Impacts and Recommendations. Retrieved from San Francisco Human Rights: https://sf-hrc.org/Modules/ShowDocument.aspx?documentid=989

Tiempo, J.M. (n.d.) Descriptive analysis on the portrayal of gays and lesbians in Filipino films since 1985-2015. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/29636048/Descriptive_analysis_on_the_portrayal_of_gays_and_lesbians_in_Filipino_films_since_1985-2015.

0 notes

Text

Trans Relations In The Black Community: A Love Letter.

I love my community. I honestly do. Black people are the most vilified, antagonized, unduly criticized people walking God’s green Earth. But we are not beyond reproach. There are many topics that are still taboo in the Black community because of deeply entrenched misogyny and the traditional need to “keep up appearances” in the street. My grandmother used to tell my cousin and I, no matter what happens in the house, you don’t let it spill outside. Which is cool when it comes to not bringing conflicts into the outside world because not everyone needs to know your business, but when it applies to things like mental illness, homosexuality, etc., it’s suppressive and disabling. As far as the burgeoning topic of gender identity and sexuality are concerned, we are still very oppressive towards our own because of the deep-seated hypermasculinity that pervades each and every level of our community, and it is damaging it viciously. This year alone, countless trans women of color have been murdered. Black men are still afraid of being caught with trans women because of what they perceive their peers will think about them, conflating trans women for men in women’s clothing, and that damaging perception is what perpetrates violence against trans women.

We don’t afford trans women the same rights we afford cisgender women because we still conflate genitalia for gender. Admittedly, I am unpacking the same damning concepts and misconstructions because of the socialization I’ve been exposed to all my life in a world where my masculinity is constantly being subjected to social cues and critiques; from family to the music we identify with to relationships, my manhood is always coopted by socialization. So why wouldn’t I buck against gender identity? Why wouldn’t I be upset when I date someone that I thought was a cisgender woman and is actually a trans woman; ain’t I gay for that? My homies are gonna turn on me so I should hide the fact that I ever did that, right? What will everyone think?

While I don’t excuse that mentality at all, I understand where it comes from. It takes a lot to undo the destructive primal chest-beating, psychosomatic reaffirmation of my masculinity and what makes me a man, and rather than address those issues, it is significantly easier to abandon all understanding and tolerance and simply be an asshole. But in being an asshole, the assertion that trans folk aren’t worth learning their identities and respecting them enough to address them as such, as well as not being antagonistic towards them is exactly the fight our community goes through. Yes, our discrimination is different systematically, but the origins are the same: I don’t value you as a human being therefore I don’t give a shit about who you are and what you stand for and I will dehumanize your existence at any opportunity that I get. That is hypocritical. We can’t very well demand the respect of “Black lives mattering” and then exclude Black trans folk because they don’t fit in with our heteronormative concepts. We don’t need to demand that trans folk meet our comfortable sensibilities; we need to meet their humanity at the base level. It literally does nothing to you to respect pronouns. It literally does nothing to you to respect identities. You’re not subscribing to some sort of wicked agenda, you’re being a decent human being.

I currently date a trans woman. She is genderfluid, meaning she identifies either as a woman or agender. Currently, her pronouns are “she/her”, but a lot of genderfluid people identify as “they/them”. She was afraid to come out to me because she felt like she would scare me off, which is the disheartening fear a lot of trans folk feel, and that’s just one of the minimum, upfront feelings. “Is this person gonna reject me? Is this person gonna hurt me? Is this person gonna kill me?” An interesting aspect of our relationship is the conversations that we have about her identity and how she’s learning a lot about herself every day, to which she imparts knowledge on me. We hit bumps in the road, because I’m still unpacking a lot of things myself. I’m learning how to unlearn all these aspects of toxic masculinity that have been dormant in me all my life. I still deal with little microaggressions that want to come out of my mouth and I have to censor myself a lot because I don’t want to be insensitive or unconsciously cruel. I still find myself on social media, talking in trans spaces and stepping on toes by centering the conversation on me, and that’s wrong. I still find myself misgendering some folks and apologizing profusely for it, to which I’m met with “don’t be sorry, be better”, and initially, it hurts my fragile male ego to be told that, but then I understand. How many times have we, as black people, had to defend our humanity to white people? How tiring does it get? It gets just as tiring for a trans person to be like “Look, I identify as this, my pronouns are these, please learn them”.

After I let her know it’s safe to come out to me and she would never have any issues with me as far as understanding and acceptance are concerned, I asked her what she deals with mentally, like what goes on in the mind of a genderfluid person. Individually, sometimes she feels feminine, but most of the time, she feels like she’s genderless, neither masculine nor feminine. We talk often about trans-affective subjects, and I’ve learned that it’s often exhausting to keep asking researchable things but she enjoys educating me, a luxury a lot of heterosexual cisgender partners aren’t afforded. I feel like it’s strengthened our bond even further. I’ve never dealt with a person quite like her and I feel privileged to know her, let alone be with her, in a world where she is targeted as a woman of color, as well as a member of the LGBT+ community. I feel like my role as an ally is increasing and that makes me elated because I genuinely care about her struggles, as well as the struggles of everyone else who has to deal with the stares and the aggressions and the violence and the social media condescension. I stand for all oppressed people, and I believe that empowering the Black community with knowledge will foster understanding, acceptance and tolerance, because we should all stand united, shoulder to shoulder, especially in these times where we all have targets firmly painted on our backs.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

FUCKING PANSIES:

Queer Poetics, Plant Reproduction, Plant Poetics, Queer Reproduction

Caspar Heinemann

with images from Lee Pivnik

‘Waking, I was certain my room was host to a demon; terrified, I watched the remorseless eyes in the half light, till dawn gave me the courage to bolt shivering with fear to my parents’ bed. My father laughed: ‘Don’t be such a pansy, Derek.’ -Derek Jarman, Modern Nature

Don’t be such a pansy, Viola tricolor, violet, heart’s-ease, love-in-idleness; Pansy goes by many names, and many names fit into and fall under ‘Don’t be such a pansy, _______.’ Don’t be such a pansy, even if there’s a remorseless demon in your room, crouching in the dark, ready to tear you apart. Even if there’s a whole remorseless world out there, even in your parents’ bedroom, ready and waiting to tear you apart.

The pansy has remained a staple in anti-queer lexicon since the last century, the humble violet symbolising weakness, effeminacy, all things effete, wimpy, and generally flowery. Propagating alongside its siblings sissy, fairy, and faggot, the pansy is a resilient flower. However, its roots as an insult are not strictly horticultural. The etymology of pansy (flower) is the French pensée, the past tense of ‘to think’, and a feminine reflexive. This occurred when, in a dubious feat of anthropomorphising, the pansy was seen to resemble a person leant over in intense contemplation, which in turn led to it becoming a symbol of remembrance. As an insult, it was applied to the ineffectual intellectual, implying an emasculating failure to embody a forceful, active, masculine ideal. The quality of thoughtfulness was already both feminized and feminizing, but the first known use of the word to describe gay men was not until 1925 (Partridge, 1984).[1] At some point along the way, the studious pensée became the flamboyant pansy, the femininity of the insult taking precedence over any other qualities. With ‘pansy’ having no non-floral meaning in English, in popular usage any association with remembrance is forgotten. The intellectual intellectual basis of the insult becomes obscured through time and translation and all that we are left with is the ontological relation of a human subject to the Viola tricolor itself, and the vague sense that there is something not right in the boy who thinks too much, looks too closely.

When the insult ‘pansy’ is thrown, there exists the obvious implication that the victim is themselves, physically, a pansy. But alongside this, to be a pansy is most likely to also be someone with an affinity for pansies, someone who would rather draw flowers in the garden than kick a ball around, a boy who would rather have a bunch of arum lilies than a brace of pistols (Jarman, 1992, p28). Being a pansy is seen as both a cause and an effect of an underlying affection for the delicate, the pretty, and the decorative. Pansies love pansies because they are pansies, which is why they are pansies. The love of pansies is a red flag on the slippery slope to becoming a pansy, and the pansy is a pansy because pansy is the word for people who love pansies. This is not an intentional morphing, but rather, after all those hours in the garden someone turns and says ‘Don’t be such a pansy’, and then there is a demon in your room, and it is clear a pansy is a bad thing to be, which is strange to consider for someone who loves pansies, but lots of things are going to be strange from now on.

The homophobia of the insult pansy is not just the implication of effeminacy from association with the flower itself, but the homophobic condemnation of perceived sameness. The pansies love of pansies is taboo in part because they are a pansy, there is no heterosexual difference in pansy desire. However, the pansy-pansy identification is not the same as Narcissus falling in love with his own image, not the egocentric self-adoration of the daffodil leaning into the pond. The pansy is intensely relational and curious, and loves other pansies (and daffodils and geraniums and buttercups and snowdrops). Remember, the pansy becomes a pansy through perceived similarity and/or attachment to other pansies. The initial recognition was with something they were yet to become. In this way, pansy is inherently a collective identity, inhabiting a multiple temporality. To clarify, this is not an essentialist argument that all pansies like pansies, as in, ‘all people perceived as queer men like Viola tricolor.’ But rather, that its formulation as a generalised homophobic insult, potentially applied to any queer man, or any person read as such, means that ‘queer men like queer men’ (uncontroversial) can be read as ‘pansies like pansies’. The collision of this meaning, with the horticultural association, begins to create a framework for a positive understanding of queerness, reproduction, survival and the natural.

As with many anti-queer insults, an underlying assumption in pansy is that there is an unnaturalness to effeminacy, that it signifies something gone astray that would never thrive or even survive in the state of nature, a rupture in the normatively gendered Arcadian ideal. The pansy clearly cannot be a real man, because he is a flower, and flowers are not men, and men are not flowers. But even the most ardent homophobe would find it hard to argue that flowers are not ‘natural’, even in all their selectively bred garden centre glory. Whilst not wanting to perpetuate the myth of queer sex as inherently unreproductive, it is important to not deny that queerness still exists with a turbulent relationship to reproduction, in the biological sense. At the heart of this is the existence of queerness in relation to a medicalised discourse that understands the queer subject in terms of biology, in a way that is inherently naturalised, assuming queerness as something to be located in genes and hormones, glands and chromosomes.

This is not a form of acceptance or understanding, but rather a naturalisation that implies a failure, a departure from the script of healthy, normative heterosexuality and gender. When the queer body is accepted as a natural form, it is always a defective natural body, an abnormality that reinforces the norm. Homophobic and transphobic discourse has adopted this position in recent years, in reaction to the realisation that an understanding of the queer body as unnatural has the unintended consequence of devaluing any biologically based understanding of gender and sexuality, rendering the cisgender heterosexual body equally unnatural.[2] In reference to the earlier (and still present) form of anti-queer rhetoric Greta Gaard (1997) points out the irony that when homophobes use the argument that to be queer is to be against nature, they are insinuating that they care about ‘nature’, which is rarely the case. This is especially true for people coming from a fundamentalist Christian theological perspective in which man’s dominion over nature is central. She writes that ‘in effect, the "nature" queers are urged to comply with is none other than the dominant paradigm of heterosexuality.’ Nature becomes a weaponised synonym for reproduction, and everything that does not directly contribute to the survival of a the species becomes an affront.

As much as the queer is being called a flower, the flower is being called a queer. As much as the pansy lends its prettiness to the queer subject, the queer subject lends their effeminacy to the pansy. Although this could be read as a reductive anthropomorphising, there is also the potential for something else if the relationship is not read as one-way mapping of human characteristics onto flowers, but also flower characteristics onto humans, with implications for the agency of both. Gaard asks us to think not only in terms of the dualisms traditionally associated with conversations around gender, race, and nature, but the ‘vertical’ associations, ‘between reason and heterosexuality, for example, or between reason and whiteness as defined in opposition to emotions and nonwhite persons […] the ways queers are feminized, animalized, eroticized, and naturalized in a culture that devalues women, animals, nature, and sexuality […] how persons of color are feminized, animalized, eroticized, and naturalized. Finally, we can explore how nature is feminized, eroticized, even queered’ (1997). Taking this as a call to arms, there is the potential for a queer identification with what is termed ‘nature’ to have positive political implications not just for queerness, but for a wider ecological and social struggles.

When read against a binary understanding of human reproduction, flowers are inherently queer. This is not a modish application of the term ‘queer’ to anything remotely ‘strange’, divorced from its roots as a slur or any analysis of human sexuality and gender, but rather a comparative statement about human understanding of gendered bodies across species.[3] While the term ‘queer’ is referring to a very specifically human (and mostly white, Western) subjects navigation of a social world, it is also inaccurate to think of plants (and other species) as exempt from and untouched by this discourse. Given the prevalence of anthropocentrism, the reading of gender in plants inevitably reverberates and affects human understanding of human gender, and the reverse. As well as not wanting to make an anthropocentric imposition onto plants, I also want to avoid essentialising queerness in humans. To borrow from Nicole Seymour, I do not want to ‘claim that queer individuals necessarily have a particular kind of relationship to the non-human; [but focus] primarily on the queer relationships that humans might develop with the non-human, and how environmental ethics might emerge from queer practices and perspectives’ (2013, p29). I would add to this an investment in thinking through how queer ethics might emerge from environmental practices and perspectives. The queer anarchist collective Baedan define queer as ‘the inherent decomposition which afflicts gender […]; not this or that historically constituted subject category, but all the divergent bodily and spiritual expressions which escape their roles’ (2014). Rather than a positive, universalising usage of queer, queer is a contingency. I hope the clumsiness of attempting to talk about how plants fuck spills over, somehow, into somewhere productive (or unproductive).

The number of scientifically validated genders for plants far exceeds those commonly understood and accepted for humans. At the most basic level, single flowers are either male, female, or bisexual (also referred to as ‘perfect’, hermaphroditic or androgynous). However, categories proliferate due to the fact that different plants grow different combinations of male, female, or bisexual flowers. This does not mean that all species have male, female, and bisexual flowers - it is possible for plants to only have either bisexual or female flowers, for example. This is complicated further by the fact that in some species, the flowers will change gender. It is important to clarify here that when we are talking about plant gender, we are potentially discussing at three different scales - the gender of an individual flower, the gender of an individual plant, and the morphology of the species as a whole, all of which determine each other. Although obviously not directly translatable, these multiple scales of plant gender provide a nuanced and useful framework for thinking through human gender, in that we are always referring to a complicated enmeshment of biological sex, individual identity, collective identity and socially enforced role, none of which can be considered independently of one another.[4]

To avoid reducing the link between the flower body and the queer body to being purely to do with reproduction in a mechanical and biological sense, it is important to think though the specificity of the situation. For one thing, many species have reproductive practices entirely contrary to the ideals of human monogamous heterosexuality.[5] For another, the conceptual reduction of reproduction to a process of sexual reproduction and the continuation of a species is profoundly anti-queer, both in a literal and abstract sense. There is clearly a specificity to flowers that has led to the association with queerness, beyond ‘flowers are not straight and have multiple genders’. Whether or not explicitly acknowledged, research and discoveries into non-human lifeforms are always embroiled in human social questions, both in process in terms of methodology, and in their consequences and applications. In their essay Involutionary Momentum: Affective Ecologies and the Sciences of Plant/Insect Encounters, Carla Hustak and Natasha Myers begin to explore this tension between botany and ideology. They write of Charles Darwin’s flower experiments, and his downplaying of the evolutionary role of self-pollination (reproduction by an individual plant possessing male and female reproductive organs) in favour of cross-fertilisation (reproduction by two plants, via insects) which was seen to be necessary for the survival of ‘higher organic beings’. Hustak and Myers write, ‘Orchids, it turns out, were caught in a queer interspecies assemblage that disrupted normative Victorian sexualities and species boundaries’ (2012, p82). Flowers must be kept at arms length to prevent them from contaminating human sexual norms, but the mapping of those norms onto the flowers becomes necessary to attempt to rationalise what is found when those flowers are not kept at arms length.[6] The flower is constantly indexed onto human sexuality and yet remains impossible to entirely understand within or assimilate into a human heterosexual framework.

CAConrad is a queer poet who for several years has been working with what he refers to as ‘soma(tic) rituals’, ritualised bodily practices which he completes and then writes from his experiences of. One of these is called Security Cameras and Flowers Dreaming the Elevation Allegiance (For Susie Timmons). CA describes his frustration at the prevalence of security cameras in his home city of Philadelphia (‘FUCK YOU WATCHING US ALWAYS!!’). The ritual resistance he describes involves taking a basket of edible flowers to the scene (‘I eat pansies, I LOVE pansies, they’re delicious buttery purple lettuce!!’). He then looks directly into the camera and proceeds to place his tongue in the flower ‘in and out, flicking, licking, suckling blossoms.’ When confronted by a security guard he responds ‘I’M A POLLINATOR, I’M A POLLINATOR!!’ As soon as it is declared, it becomes obvious that of course he is, undeniably, a pollinator. Despite not being able to facilitate the actual reproduction of the plants, due to species constraints, the small act of resistance towards the security cameras becomes an act of potential pollination, a pollination of politics and ideas and poetry and joy, both a self-pollination and a cross-pollination.[7] The security cameras that CA is resisting are a part of an ecosystem, and he uses his agency as a being within that ecosystem to make a somatic and semiotic intervention against a mode of biopolitical control.

In CA engaging in a sexualised public ritual with flowers, there is also an implied parody of straight anxieties around queer sexuality, such as the argument that legalising gay marriage is a slippery slope towards people being allowed to marry their dogs. Apart from the obvious association of queerness with animality and the non-human, these anxieties are often explicitly or implicitly predicated on the notion that all unreproductive sexual practices are on some level unethical, prioritising pleasure over the continuation of the species. CA’s pollinator intervention gains another dimension when understood in terms of certain species of orchids that have the ability to attract pollinators without a material prize (nectar), but purely on the basis of their imitation of insect sex pheromones, attracting insects on the basis of desire, rather than physical sustenance.

In Animacies, Mel Y. Chen discusses linguistic animacy hierarchies, the way in which language is used to assign different levels of agency to matter, both living and non-living. In English, firmly at the top is the white male subject, everything else placed on a scale somewhere between him and a rock, or other perceived as wholly inactive matter. The argument is that to be compared to anything lower down inherently operates as an insult, in that it implies loss of agency, which is then linked to intelligence, ability, value, and social standing. Chen asks us, ‘If language normally and habitually distinguishes human and inhuman, live and dead, but then in certain circumstances wholly fails to do so, what might this tell us about the porosity of biopolitical logics themselves?’ (Chen, 2012, p7). What are the implications when a being higher up the animacy hierarchy (a human) chooses to align themselves with a ‘lower’ being (for example an insect pollinator)? The act of solidarity both implies a rejection of the value system which places life forms on such a hierarchy, attempting to level the playing field, and recognising how in certain situations it can be desirable to disassociate from the expectations associated with being ‘human’. The situating of ‘homo sapiens’ as something that can be disidentified with and opted out of, rather than a taxonomical fact, finds affinity with Giorgio Agamben’s assertion that ‘Homo sapiens, then, is neither a clearly defined species nor a substance; it is, rather, a machine or device for producing the recognition of the human’ (2003, p26). In addition to active verbal identification with other non-human agents, In The Greenhouse by Veronica Forrest-Thomson highlights how simply the experience of embodied encounter with the non-human can render taxonomies feeling arbitrary and redundant:

The silent rhythm of pulsating pores

filling my lungs with filtered earth

is all I feel or know of alien shapes

that once were flowers.

I breathe their breath

until all definitions are dissolved,

and homo sapiens is nothing more to me.

Perhaps less aligned with Agamben’s definition, these lines find more affinity with Karen Barad’s position that ‘“Humans” are neither pure cause or pure effect but part of the world in its openended becoming’ (2003, 821). Acts of Youth by the late queer poet John Wieners provides another instance of flower-consumption as symbolic of freedom from oppressive power structures.[8] He writes:

The fear of travelling, of the future without hope

or buoy. I must get away from this place and see

that there is no fear without me: that it is within

unless it be some sudden act or calamity

to land me in the hospital, a total wreck, without

memory again; or worse still, behind bars. If

I could just get out of the country. Some place

where one can eat the lotus in peace.

Give me the strength

to bear it, to enter those places where the

great animals are caged. And we can live

at peace by their side.

‘Some place where one can eat the lotus in peace’ is presented as the ultimate sanctuary from the fear and violence of his world, both inner and outer. Flower-eating operates as a literal form of, and metaphor for, spiritual survival precisely because of the low nutritional value of flowers, especially when compared to their high symbolic value. To eat a flower is to aesthetically nourish the body. Eating the lotus in peace is to embody a form of consumption not predicated on a violent conquest, but a gentle taking in of the other into the self, a pleasurable participation in an affective-aesthetic ecology. Wieners desire to live at peace by the side of the great animals in their cages demonstrates an identification with the feral and a siding with the non-human over the human (for who put the animals in cages?). But it is perhaps telling that even in the potentially limitless space of poetics, Wieners chooses to live with caged animals. Trans poet Verity Spott ends her piece Against Trans* Manifestos (2015) with the lines: ‘Determined as it is by a start and a finish, a false double, something that contains at least five harmonic falsities on a liberal map of social reality. Perhaps this is why we have a fetish involving cages; everything impossible to communicate.’ Read against this, Wieners collective desire (‘we’) to live with caged animals becomes a recognition of the contingency of pleasure, and of the description of pleasure as itself a form of caging, and how agency can be enacted whilst being trapped ‘inside’.[9] There is also the issue of temporality within cages, and to what extent temporality is defined by a sense of history and progress, necessarily implying movement and action. Hustak and Myers identify the stationary nature of plants as part of the reason they are placed near the bottom of ‘hierarchies that identify outward motion and action as signs of agency’ (80). This has resonance with the origins of pansy as an insult, as rooted in an notion of thoughtfulness and introspection as effeminate and inferior to active, assertive masculinity. In Our Lady of The Flowers Jean Genet describes the gender identity of the character Divine:

‘Her femininity was not only a masquerade. But as for thinking woman completely, her organs hindered her. To think is to perform an act. In order to act, you have to discard frivolity and set your idea on a solid base. So she was aided by the idea of solidity, which she associated with the idea of virility, and it was in grammar that she found it near at hand. For if, to define a state of mind that she felt, Divine dared use the feminine, she was unable to do so in defining an action which she performed. And all the ‘woman’ judgments she made were, in reality, poetic conclusions.’ (1988, p176)

Solidity and action are associated with the masculine, but this is complicated by the assertion that ‘to think is to perform an act.’ Divine dares to use feminine pronouns for her states of mind, but not in defining her actions. If thinking is an action, then ‘state of mind’ has to be referring to something other than thoughts. The ‘‘woman’ judgements’ she made, which are emphatically not thoughts, are ‘poetic conclusions’. The distinction between active masculine ‘thoughts’ and feminine ‘states of mind’ and ‘poetic conclusions’ is that in order to act, ‘you have to discard frivolity and set your idea on a solid base.’ Solidity and virility are found in grammar, and therefore poetic language is disqualified from the realm of ‘thinking’ due to its frivolity and instability. Its exclusion from thinking as a masculine exercise, outside of solidity and grammar and certainty, means that poetry is in a unique position to express possibilities and potentials outside of dominant thought.

In an essay entitled The Queer Voice: Reparative Poetry Rituals & Glitter Perversions CAConrad describes the somatic rituals he performed to write poetry and attempt to heal himself from the trauma of the homophobic murder of his boyfriend, Earth. One of these rituals results in a dream, where CA finds himself in a garden with Earth, although they do not meet human face to human face. In the garden Earth communicates with CA through flowers who explain to him the difficulty of Earth’s time on earth, acting as prophets from the spirit world whilst remaining entirely grounded in earth and syntax. CA explains that the flowers did not speak with mouths, but ‘their centers mashed up and down as they told me [Earth] could not see me now because he was busy repairing.’ In German the phrase ‘Durch die Blume Gesprochen’, literally ‘spoken through a flower’, means to subtly hint at something without giving away all the details, a minor verbal obfuscation to soften blows or gently allude to an issue. In English, there is ‘flowery language’, with some similar implications and an added air of assumed affectation and pretension (remember the origins of ‘pansy’?). There is also the Latin phrase ‘sub rosa’, literally meaning ‘under the rose’ and used to indicate secrecy and confidentiality. Flowers are seen as untruthful, dishonest in their embodiment, as hiding something under their opulent exteriors. However, in CA’s prophet-flowers the exact opposite is the case, the flowers are messengers of the deepest, most vital truths.

In common parlance there is something in the overtly elaborate and ornate that becomes read as at best wasteful, and at worst deceitful. As a bridge between morphology and semiotics, Georges Bataille colludes with this perspective in The Language of Flowers when he writes, ‘Thus the interior of a rose does not at all correspond to its exterior beauty; if one tears off all of the corolla's petals, all that remains is a rather sordid tuft.’ (Bataille, 1985, p12) The flowers insides are seen as a betrayal of its exterior form, despite that exterior form existing partially for the purpose of attracting insects to the interior. Whilst admitting that some flowers (again, orchids) possess ‘elegant’ stamens, for Bataille this beauty is ‘satanic’, and ‘one is tempted to attribute to them the most troubling human perversions.’ (12) It feels redundant to say that flowers are sexualised, in the sense that they are literally reproductive organs. To be more specific, the sexualisation of flowers is both a cause and consequence of their status as feminine. Bataille makes this misogyny explicit, going on to state that once flowers die, they do not age ‘honestly’ like leaves, but wither like ‘old and overly made-up dowagers.’ (12) Flowers are singled out for their aesthetic qualities, objectified for their external beauty, and reduced to their reproductive function, a feminised position. Simultaneously, they are seen as performing in excess of that role, of being too flamboyant and melodramatic for the task at hand, their beauty seen as a form of deception and trickery. In addition to the obvious analogy with women under patriarchy, this mistrust on the basis of perceived inauthenticity and frivolity also has resonance with a queer position.

To deal first with inauthenticity, I want to suggest that the treatment of artifice as falsification and dishonesty is a feature of straight culture, with little relevance to most queer people. Despite the limitations and dangers of this kind of essentialising, there are material issues at hand. For example, for trans people there is often the sense that an external presentation that could be perceived from the outside to be inauthentic is in fact the most honest expression of their inner selves, and many queer people must keep their desires or certain aspects of their lives internal, or at least restrict who has knowledge of them. To exist as queer in the world requires a certain amount of ‘speaking through flowers’, acknowledging the impossibility and possible undesirability of an entirely transparent existence. Michel Foucault in A History of Sexuality describes the transition from sodomy as a practice into the homosexual as a subject position, ‘a personage, a past, a case history, and a childhood, in addition to being a type of life, a life form, and a morphology, with an indiscreet anatomy and possibly a mysterious physiology […] [sexuality] written immodestly on his face and body because it was a secret that always gave itself away’ (1978, p43). The assumed knowability of the queer body through its naming as such, and that naming giving rise to the presumption of a specific sexual morphology, provides some context for the ambivalent relationship of many queer people to visibility and representation. Speaking through flowers could be a mode of engagement simultaneously flaunting and obscuring one’s ‘indiscreet anatomy’, operating as a form of resistance to and avoidance of biopolitical control, a tactic of conscious illegibility and subterfuge.

A concept closely related to inauthenticity is unnaturalness, both related to the idea that there is a true form that is being betrayed. When Bataille talks of being tempted to attribute to flowers ‘the most troubling human perversions’ it becomes clear that despite falling under the rubric of what is commonly referred to as ‘nature’, the sexuality of flowers is only tenuously perceived as natural. Timothy Morton describes nature as a ‘transcendental term in a material mask’, and the end of a potentially infinite metonymic list: ‘fish, grass, mountain air, chimpanzees, love, soda water, freedom of choice, heterosexuality, free markets…Nature’ (2009, p14). When we accept that there is no actual criteria for naturalness, apart from vague essentialist subjective perception, there is the awkward reality that if something is described as unnatural then it is unnatural, inasmuch as something becomes natural through the same process. As flowers are often read as suspiciously unnatural, they are in some sense are. The unnaturalness of flowers has to do with excess, which is to say wastefulness, which is to say floweriness. To be natural is to fit into a straight human logic of heterosexual reproduction, whether through direct participation or resemblance to the model, to refuse this demand is to be against nature. It is here that both queers and flowers fall through the cracks.