#especially theological aesthetics and hes such a subject

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

naamah i cant lie i am sooo curious and wanna hear more about you and argenti, if you have anyyy crumbs please :’) ♥️

HII Gray my love 🖤🖤🖤 your question made me run in circles for a bit fkfkgk. Honestly i want to hate him so much and hit him with a cartoonishly huge mallet!! He's so upsetting and silly and i just need to hold him like a little hámster Gray, help???

Okay so this is my evil selfship and villain origin story and wish i could hate Argenti but he's so baby and so dear to me bye. Actually just found him silly and ridiculous and wanted to slap the shit out of him at first but suppose I had the odd thought of "hmm its no good bc bet he'd like that :/ besides it would be kinda hot" and then it was downhill so fast for me 😭

The thing is i can't be mean to my men because then i feel sad and immediately want to make up for that by being nice and ig that was our whole dynamic until I warmed up (unwillingly) to him?

Other than that i think we share the same brand of over the top ridiculousness and to think he's just a little guy who finds beauty in even a houseplant and goes just wandering around the universe helping others is just so T-T sobbing.

He's my knight, my prince, my boytoy, my preraphaelite muse, my thesis topic, my amoeba under microscope, my artsy lewd photography subject. and my little lapdog too if that makes sense, i would literally guard him from evil... I'm his Lamia, his belle dame sans merci, his scary witch wife figuratively. i get in front of him and tell the cashier he asked for no pickles,, i have him by a collar of thorns, i unfortunately just feed into his silliness and delusions all the time.

Want to say so badly i am the only person who gets on his nerves enough to actually upset him (besides boothill probably?) and make him get into honest to god arguments dropping the good faith thing and losing his """cool""" but unfortunately that also works like two times before he figures out i just get a rise of seeing him angry and flustered and being mean on purpose and he's like. Oh. And i lose every bit of that upper hand quickly >_<. Probably the only instance he gets ahead and teases me for a change...

#Surely theres a deeper reasoning to this selfship because i swear im a nerd for the concept of (philosophical) aesthetics#especially theological aesthetics and hes such a subject#i wanna put him under a microscope and study him for ages in all seriousness#his character is unfathomably deep and interesting to me ughhh but lets keep moving.. im normal#thank you so much for your interst gray😘😘😘 even if it comes from the place of a concerned friend going “why him...”#or the friend subject to one's cringe boyfriend as collateral damage <3 luv you#asks

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

You're a druid and an ex-evangelical, right? What does being a druid mean to you? How did you get from evangelicalism to where you are now? And of course feel free to ignore this if it's nosy. (sincerely, a Christian who wants to leave but who doesn't know what to do)

this is going to make me sound ignorant as hell, lol, but i'm happy to share

under a cut because this got very long, sorry, lol.

my personal progression was: "vaguely christian -> VERY christian -> christian agnostic -> agnostic/atheist -> agnostic/druid -> some sorta druid-neopagan-animist thing." i guess i'll just go through what made me switch between each of those, and close out with some high-level thoughts that may be helpful for you?

okay, so when i was

VAGUELY CHRISTIAN,

i went to Sunday school every week because That's What You Do, and because my whole hometown was very southern Baptist, i never questioned the veracity of its teachings much... until they ran a whole weekly series on "why [x] is wrong," where [x] is some other group

e.g., we had a week on why Mormons are wrong, and i didn't bat an eye because i hadn't even known Mormons existed until that moment

then we had a week on why Muslims are wrong, and that... bothered me, because i had a friend who was Muslim, and she was just objectively a better person than me, and i was like "any universe where she goes to hell and i don't seems really fucked up"

then we had a week on why EVOLUTION was wrong, and that just absolutely threw me, because while i hadn't thought about evolution much (i think i was in fourth grade or so), it seemed common-sense? scientists thought highly of it? "adaptation over time" just seems logical?

so i went to the public library every day after school for like a week, read some Darwin and some science books, and came back to my Sunday school teacher with, like, an itemized list of objections to the whole "evolution is wrong" thing. and he came up with some standard Answers In Genesis rebuttals, and i did more research and came back the next week with more science, and we repeated this a few times until he was like "lua, you just gotta take some things on faith"

which. lmao. full existential crisis time, because no matter how hard i thought, i couldn't *not* believe in the science, but i also didn't want to go to hell, so i was like "maybe if i believe SUPER HARD i will SOMEDAY be able to unbelieve the condemn-me-to-hell bits"

so i decided to become

VERY CHRISTIAN

and my frantic googling for shit like "proof of god" and "god and evolution" *eventually* broke me out of the Answers In Genesis circles of the internet, and into some decent Christian apologia, like, think First Things and various Catholic bloggers. and there, i found some way to square my gut sense that evolution was right, with a spiritual worldview.

like, i remember finding some blogger who said:

"young earth creationists get tripped up when they try to explain stars that are millions of light-years away, and end up basically arguing that God's tricking us somehow, and—no! my God lets you believe in the evidence of your eyes, my God does not demand that you make yourself ignorant or stupid, my God expects you to use your brain"

and i just started crying at my computer, because no one had ever said "using your brain is Good and part of God's will," i was like *finally* here's someone who won't tell me i'm going to hell for just *thinking* about things

(st. augustine does a much better riff on a similar theme, fwiw, but i only found him later)

still, it was an uneasy fit, because, the more i learned and read about world history, the more it seemed... weird... that the One And Singular Path To Salvation was... the successor to some niche desert cult... which didn't even occur at the *beginning* of written history, like, it was all predated by that whole Mithraism thing, etc... and like, sure, i could trot out all the standard theological talking points for why Actually This Makes Perfect Sense, but gut-level-wise, the aesthetics just seemed kinda dumb! and no level of talking myself out of it made that feeling go away!

so at this point i started referring to myself as a

CHRISTIAN AGNOSTIC

i mean, not aloud. i still lived in southernbaptistopia and i didn't want, like, my hair stylist to tell me i was a horrible person. but in my *head* i called myself Christian agnostic and it felt right.

and i started church-hopping, which honestly was really fun, would recommend to anyone at any point. i visited the fire-and-brimstone baptist church, the methodist church, the episcopalians, the universal unitarians, etc.

unfortunately, while this gave me *some* new perspectives, each of the places either had the same shitty theology as my old megachurch (i remember the *acute* sense of despair i felt when i was starting to jive with a methodist church... only for the dumbass youth minister to start going on about evolution), or, they just lacked any sense of the *sacred*. like, the Church of Christ churches, with their a capella services, *definitely* had it; i felt more God there in one service than i did in a lifetime of shitty Christian rock at the megachurch. but their beliefs were even *more* batshit, so. big L on that one.

having failed to find a satisfactory church, i was basically

AGNOSTIC/ATHEIST

by the time i went to college, but honestly pretty unhappy about it; while it was harder than ever for me to actually *connect* with the divine, i didn't like thinking that my previous experiences of the divine were total lies. because my shitty evangelical church, for all its faults, could not *completely* sabotage the sense of God's presence. there were real moments in that church where i do believe i experienced something divine. mostly mediated by one particular youth minister, who in hindsight was the only spiritual teacher in that church who didn't seem a bit rotten inside, but! it was something!

so when i happened upon a bunch of writings on the now-defunct shii.org (that's the bit that makes me look WILDLY ignorant, lol), i was utterly captivated.

said author was a previous archdruid of the Reformed Druids of North America, an organization that was formed in the 1960s to troll the administration of Carleton College (there was a religious-service-attendance requirement; they made their own religion; their religion had whiskey and #chilltimes for its services). however, this shii.org dude seemed to take it pretty seriously. he was studying history of religion and blogged a lot about his studies, both academic and otherwise. while RDNA had started out as a troll, that didn't mean they hadn't *discovered* something real in the process, he said.

this, already, was going to be innately appealing to me; i've got a soft spot for wow-we-were-doing-this-ironically-but-now-it's-kinda-real? stuff in general.

in particular, shii.org’s discussions on the separation of ritual from belief was really interesting to me: most religions/spiritualities have *both*, but like, you can do a ritual without having the Exact Right Beliefs (if there even is such a thing!), and it can still be useful to you, it can have real power. (he had a really lovely essay, speculating on the origins of religion as just a form of art, but that essay is now lost to the sands of time, alas.)

(note that i wouldn't really recommend seeking out *recent* writing by the shii.org guy; he kinda went full tedious neoreactionary-blowhard-who-reads-a-lot-of-Spengler at some point? sigh.)

the shii.org guy led me to checking out a bunch of books on the history of neopaganism & also books by scholars of religion in general, and the more i read, the more excited i became. and i started doing little ritual/meditation stuff here and there.

then i was fortunate enough to attend some events with Earthspirit (this was when i lived in Boston), which cemented my hippie dalliances into something more real. the folks there, being from Boston, were all ridiculously overeducated (a sensibility that appeals to me), but also, being the kind of folks who drive out to a mountain in the middle of nowhere for a spiritual retreat, they tolerated a full range of oddities (everyone from aging-70s-feminist-wiccans to living-on-a-farm-with-your-bros-Astaru to dude-who-started-having-weird-visions-and-is-just-trying-to-figure-out-the-deal to Nordic-spiritualist-with-two-phds-from-Scandanavian-universities-on-the-subject, etc), which gave me a lot of room to explore different types of rituals, ceremonies, "magic", etc.

(polytheism in general lends itself well to this sort of easy plurality! i can believe other people are experiencing something real with their gods, and i can be talking to a totally different set of gods, and that’s just all very compatible, etc)

anyway, i started calling myself

AGNOSTIC/DRUID

around then, because i knew i'd found *something*, something that felt like all the realest moments i'd ever had in nature, and all the realest moments i'd ever had in that shitty megachurch, but i wasn't quite ready to put a theology to it.

but, idk, you do the thing for a while, and you start encountering some things that you may as well call gods, and you realize you're in pretty deep, and you ditch the "agnostic" bit and just throw hands and start describing yourself as

SOME SORTA DRUID-NEOPAGAN-ANIMIST THING

because that's the most precise thing you can muster. in particular, the druid bit resonates because nature's still very much at the center of my practice; the neopagan bit resonates because i'm not especially interested in reconstructing older traditions or being faithful to any actual pre-Christian traditions, and animist resonates because what i sometimes call gods seem to be tied pretty tightly to the land itself. it's all very experiential; all this mostly means i'm some weird chick who sometimes grabs a car and drives out someplace very lonely and hikes for a while and does some hippie shit to try and talk with the land or the god or whatever is there. and sometimes i come back from it changed, or refocused, or what-have-you, and hopefully i'm better for it. i'm aware this makes me look a little ridiculous, and is an unsatisfying answer, sorry!

WRT YOUR SITUATION

i don't know you or your situation, obviously, but if i wanted to give former-me some advice to save her some angst, i'd say

-> Christendom itself is far wilder and more diverse than many churches lead you to believe. if you still want to be Christian on some level, and it's just a shitty church that's convinced you the whole project is fucked, i'd honestly explore, i dunno, your nearest Quaker meeting. they're invoking the Holy Spirit with regularity but they're not raging douchenozzles about it.

-> if you're specifically interested in druidism, i found John Michael Greer's "A World Full of Gods" really nice. (caveat: Greer has *also* gone full right-wing nutjob these days, sigh, so like. would not recommend a great swath of his writing. but that one's good)

-> deciding that a just God wouldn't give me a brain and then ask me not to use it was hugely comforting to me. like, that was the start of the whole process, that was what made me feel ok searching for other churches and trying to find something that fit. obviously you should take this with 800 grains of salt, because obviously i'm no longer Christian, and thus maybe i'm just some poor misguided fallen soul, but... i still kinda believe that! maybe if you can make yourself believe that, it'll seem less scary?

idk, happy to answer more questions, sorry for the long ramble, hope it helped~

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

“ Should the Haruspex attempt to autopsy her body on Day 11, he will make the curious discovery that Aglaya does not appear to have any organs. However, looting her body reveals she is carrying a Revolver. “

trawling some highly enjoyable patho wiki content. Congratulations Aglaya Lilich on becoming a Body without Organs, with a gun! you go girl!

“Aglaya contends with God. Those she touches begin to rebel against the established order of things. At the same time, Aglaya is the voice of the law. She sees the universe as a machine. She maintains that the logic of the universe is above everything—polyhedrons be damned. To her, contending with God, too, is a form of restoring justice and natural law. Those she touches begin to realize that there are limits of what’s possible, and they must be accepted with humility.”

Humility

“I should have written nothing[1] at all, but it is far too late for that. Sin and guilt[2] have entered the world[3]— never mind where from, since in any case it would do no good to close that box — and I am no longer striding the crests of my dreams, filling my lungs with air and expelling it again, now instead I am manipulating the keys of a machine[4] striving to thus let my dreams pour and play out across the space of an information-obsessed plane of existence.

There exists no good reason[5] to occupy this space, especially when I have the heights and depths of life wholly available to me at any moment, and yet something compels me, God help me.[6] I have no hope that I will save anyone this way. Not even myself. I know I will not even reach to prevent the wretched[7] from abusing whatever I create. It is a fact that to take something from oneself and put it out into the world is to let it escape and become everything you didn’t want it to be. They say this is so for God the Father as for every human father. I do not believe in either one, but their stories both hold a strange beauty for me.

One can create a monster[8] or a babe; the difference is purely aesthetic. But it is this question of creation. Many simply put it aside, to their own loss. They still create things but they deny they are doing so. They are befallen by atrophy.[9] Others take on the question of creation by accepting the market assurance that whatever makes money must be good because, so the logic goes, people buy things that are good.[10] They become lost to the world of production. Others, in reaction to this, turn toward smaller and smaller circles to keep their creatures safe from the real world. But these spaces are either infected by the social disease or else suffocate for lack of oxygen.

There are some rare exceptions. No one can say where they come from. They destroy all that has come before. They blow into a dying ember. Without them there would be nothing at all.

Now, we have to say that the whole world without them would be an empty[11] dull[12] pale[13] and suffocating lifeless and deathless nothingness, and that they themselves are also a nothingness, but an ecstatic explosion of creative destructive nothingness. So it will be worth keeping in mind that there is a huge and unspeakable gap between the qualities of different sorts of nothingness. Otherwise everything will be overcome by an immense confusion.[14]

The first aspect which ensures that there is something interesting rather than nothing is the explosive energy of the sun. The second is the implosive energy of the earth. These provide for the habitation of a thin membrane where their intercourse takes place. Here there exists a tension between them. Much life forms by rebelling against being crushed into the bowels of the earth and the depths of the sea, whether this rebellion is volcanic, evaporative, or organic. Life must protect itself from being lost in the emptiness of space or scorched in the heat of the sun, and so it also flows, crumbles, burrows, glides, swims, falls and floats downward. This might be all, were it not for something else. Organization, organism, orgasm.[15]”

-Musings on Nothingness (And Some of It’s Varieties)

“Producing, a product: a producing/product identity. It is this identity that constitutes a third term in the linear series: an enormous undifferentiated object. Everything stops dead for a moment, everything freezes in place—and then the whole process will begin all over again. From a certain point of view it would be much better if nothing worked, if nothing functioned. Never being born, escaping the wheel of continual birth and rebirth, no mouth to suck with, no anus to shit through. Will the machines run so badly, their component pieces fall apart to such a point that they will return to nothingness and thus allow us to return to nothingness?

It would seem, however, that the flows of energy are still too closely connected, the partial objects still too organic, for this to happen. What would be required is a pure fluid in a free state, flowing without interruption, streaming over the surface of a full body. Desiring-machines make us an organism; but at the very heart of this production, within the very production of this production, the body suffers from being organized in this way, from not having some other sort of organization, or no organization at all. "An incomprehensible, absolutely rigid stasis" in the very midst of process, as a third stage: "No mouth. No tongue. No teeth. No larynx. No esophagus. No belly. No anus."

The automata stop dead and set free the unorganized mass they once served to articulate. The full body without organs is the unproductive, the sterile, the unengendered, the unconsumable. Antonin Artaud discovered this one day, finding himself with no shape or form whatsoever, right there where he was at that moment. The death instinct: that is its name, and death is not without a model. For desire desires death also, because the full body of death is its motor, just as it desires life, because the organs of life are the working machine. We shall not inquire how all this fits together so that the machine will run: the question itself is the result of a process of abstraction.”

-Anti-Oedipus ch. 1, “THE DESIRING MACHINES”

youtube

I can't stitch it together… but I can cut the knot.

We're all just… dancing on our strings.

Whenever I trace the edges of possibility on a map, I find myself reaching for an eraser not soon after…

Imagine a sphere. See it in your mind's eye. Now lay it out flat. Why is that so easy, when topology is so hard?

We live under the shadow of a higher power… I just despise it.

Only a fool would cut the Gordian knot. It ought to be… vivissected.

The squeal of the gears can't halt the machine.

Why do they insist on torturing me?

There is an immutable and rational order that fate itself has composed. All things run their inevitable courses, down the topology of the universe, toward the mass of this black gravity.

Let's open it. Carefully. And tally the contents.

The judgment of God, the system of the judgment of God, the theological system, is precisely the operation of He who makes an organism, an organization of organs called the organism, because He cannot bear the BwO, because He pursues it and rips it apart so He can be first, and have the organism be first. The organism is already that, the judgment of God, from which medical doctors benefit and on which they base their power. The organism is not at all the body, the BwO; rather, it is a stratum on the BwO, in other words, a phenomenon of accumulation, coagulation, and sedimentation that, in order to extract useful labor from the BwO, imposes upon it forms, functions, bonds, dominant and hierarchized organizations, organized transcendences.

The strata are bonds, pincers. “Tie me up if you wish.“ We are continually stratified. But who is this we that is not me, for the subject no less than the organism belongs to and depends on a stratum? Now we have the answer: the BwO is that glacial reality where the alluvions, sedimentations, coagulations, foldings, and recoilings that compose an organism—and also a signification aid a subject—occur. For the judgment of God weighs upon and is exercised against the BwO; it is the BwO that undergoes it. It is in the BwO that the organs enter into the relations of composition called the organism.

The BwO howls: “They’ve made me an organism! They’ve wrongfully folded me! They’ve stolen my body!��� The judgment of God uproots it from its immanence and makes it an organism, a signification, a subject. It is the BwO that is stratified. It swings between two poles, the surfaces of stratification into which it is recoiled, on which it submits to the judgment, and the plane of consistency in which it unfurls and opens to experimentation.

If the BwO is a limit, if one is forever attaining it, it is because behind each stratum, encasted in it, there is always another stratum. For many a stratum, and not only an organism, is necessary to make the judgment of God. A perpetual and violent combat between the plane of consistency, which frees the BwO, cutting across and dismantling all of the strata, and the surfaces of stratification that block it or make it recoil.

- “ Deleuze/Guattari; How Do You Make Yourself a Body Without Organs? “

youtube

(every morning i listen to confessional, i don’t give a shit bout the bulk ov it, still i keep it professional. and as penance i tell em to proselytize, say the sun is red, say that i am red, say that all their bases belong to us)

The crack Where is the crack? When did I crack?

Then I’ll stand alone on a planet with Nothing left to remember it And I’ll try, I’ll try, I’ll try to prevent it I’ll try, I’ll try, but I’ll never stop it, no

Muzzle me, muzzle muzzle me Bind my will and break of me And you try, you try, you try to prevent it You’ll try, you’ll try, but you’ll never stop it, no

because, laugh if you like, what has been called microbes is god, and do you know what the Americans and the Russians use to make their atoms? They make them with the microbes of god.

- I am not raving. I am not mad. I tell you that they have reinvented microbes in order to impose a new idea of god.

They have found a new way to bring out god and to capture him in his microbic noxiousness.

This is to nail him though the heart, in the place where men love him best, under the guise of unhealthy sexuality, in that sinister appearance of morbid cruelty that he adopts whenever he is pleased to tetanize and madden humanity as he is doing now.

He utilizes the spirit of purity and of a consciousness that has remained candid like mine to asphyxiate it with all the false appearances that he spreads universally through space and this is why Artaud le Mômo can be taken for a person suffering from hallucinations.

- What do you mean, Mr. Artaud?

- I mean that I have found the way to put an end to this ape once and for all and that although nobody believes in god any more everybody believes more and more in man.

So it is man whom we must now make up our minds to emasculate.

- How's that?

No matter how one takes you you are mad, ready for the straitjacket.

- By placing him again, for the last time, on the autopsy table to remake his anatomy. I say, to remake his anatomy. Man is sick because he is badly constructed. We must make up our minds to strip him bare in order to scrape off that animalcule that itches him mortally,

For you can tie me up if you wish, but there is nothing more useless than an organ.

To Have Done With the Judgement of God

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Terra Ignota

Over the last few weeks, I read Terra Ignota. I read all of the three published books so far: Too Like the Lightning, Seven Surrenders, and The Will to Battle.

Every review of Terra Ignota I have ever read is wrong. Or rather, every review of Terra Ignota I have ever read takes an extremely different perspective to my own, to the extent that I genuinely don’t understand how the author could have concluded that.

So as not to keep anyone in suspense, my perspective on Terra Ignota is that they are surprisingly trashy books, in a world that doesn’t make very much sense, but that doesn’t matter because the heart and soul of these texts is over-the-top soap opera drama. I think they are probably bad, and they outright offended me at several points, but nonetheless they drew me in enough that I wanted to keep reading. There is merit in that.

If you’re the sort of person who cares about spoilers, this is your only warning.

As I said, I don’t understand most of the reviews I have read of these books. I simply don’t.

I don’t understand the view that the writing itself is poetic and beautiful. Palmer has some good phrases from time to time, but overall I don’t find the prose particularly amazing. This is a very subjective point, so I won’t belabour it.

I don’t understand the view that the books are a masterful triumph of worldbuilding. From my perspective, the worldbuilding is actually kind of half-assed, and more importantly, Palmer does not seem to actually care about worldbuilding that much. It isn’t her priority. Reading the books I found myself constantly asking “How does X actually work?” or “Y sounds totally insane, could you explain how it makes sense to me?” or “Z seems like it clashes with X, please resolve this contradiction for me?”, and Palmer never answers those questions for you. If I want some more explanation for why, say, a global transportation system serving billions of people is run without oversight, from a single private residence, looked after by a man well-known to be suicidally depressed… nope, I’m not getting that. If I want some context for how hive-switching works, or how it interacts with crime, not happening. Even minor questions: in The Will to Battle, our heroes talk to a band of criminals involved in human trafficking, and I immediately wanted to know what human trafficking means in a world where borders have been abolished, geographic nations have been abolished, and every place on Earth is just a short taxi ride from every other place. This is the sort of question Palmer does not answer or even acknowledge.

And I don’t actually buy that she’s interested in the questions that I see raised when the books are spruiked to me. Are you intrigued by the question of what the world would look like if every individual could choose their own government, their own law code, unconstrained by geography? I’m intrigued by that. It sounds interesting. But this is not a question that Terra Ignota is actually interested in. It seems like it should be interested in it, and I read enough breathless expositions of how cool the hive system is that I expected Terra Ignota to be interested in it… but it’s not. If you’re interested in, say, the question of whether a permanent exit option would make absolute dictatorship more humane, as in the Masons, then I agree that’s interesting – but it is not a question that the text of Terra Ignota takes any interest in. The big worldbuilding questions raised by the hives are all window dressing.

I don’t understand the idea that Terra Ignota is a brilliant depiction of utopia. I want to acknowledge straight off the bat that I may have a bias here, because Terra Ignota’s world is premised on the, well, genocide of people like me, or at least the forcible suppression and exile of people like me, but I don’t think it’s only the fact that I’m openly in defiance of the First Black Law. Rather, I note two things here. Firstly, it’s hard to see whether Terra Ignota’s society is actually utopian because we spend so little time in it. We do not see how ordinary people live in this world, or what makes it wonderful. What Terra Ignota spends most of its time on is the scheming and backstabbing of the dozen most powerful people in the world, and everyone outside that little circle barely exists in the text. (Abigail Nussbaum noted in her review that Terra Ignota’s world never really feels like it has more than a few hundred people in it, and I agree.) It’s hard to convincingly argue Terra Ignota is a utopia or a dystopia, because we never meet the whole population. We meet a small handful of amoral nobility as they play out a space opera Game of Thrones. That’s certainly entertaining, and I give Palmer credit for making it fun to read, but it’s not really an investigation of utopia. Secondly, where we do see glimpses of the world outside the parlours of the ruthless rich, it…honestly seems rather conventional, and rather like the 21st century. People work fewer hours a week, taxis are much more efficient, movies have smelltracks as well as soundtracks, they go to the Olympics, apparently the Oscars endured the collapse of all nations and religions… but there is little in this world that seems radically different to our own. It’s all minor, incremental bits of technological progress. They’ve eliminated poverty, which is good, but I usually expect something more radical from utopia than that. What do people actually do in Terra Ignota that’s different to what any upper-middle class American might do today? Other, of course, than not go to church, call everyone singular they, and wear tracking devices.

I don’t understand the idea that these books deal with deep philosophical or theological themes. Like the hives themselves, it’s all window dressing. The narrator Mycroft is obsessed with the 18th century, and so is a bizarre anachronistic brothel that somehow every major world leader attends (cf. worldbuilding being weak, the world only feeling like it has a few hundred people in it), but they don’t do very much with this. Mycroft imagines Thomas Hobbes occasionally butting in, but his imaginary Hobbes has little to say beyond "Hi, I’m the guy who wrote Leviathan!” The characters reference Diderot and de Sade and Voltaire, but usually only on the surface level, and when they do try to go deeper, they often get the references wrong. The same for the theology. My point is not that Terra Ignota is bad: just that it isn’t really that interested in the political philosophy or the theology. It uses 18th century thought as an aesthetic. Deism, miracles, proof of God’s existence, how gods might communicate, etc., are not the questions that occupy the text. Ada Palmer is not a theologian.

But all that said, I enjoyed Terra Ignota.

I want to emphasise that. I enjoyed Terra Ignota! I am not saying that it’s bad! I’m just saying that it was not what everyone told me it would be.

Terra Ignota is a book about a bunch of very powerful, very horrible people, who all apparently go to the same brothel and are interested in the same wacky theories about human nature and God and so on, lying to and betraying each other. I think Palmer is really interested in the characters. Mycroft, our pretentious narrator who by the end of book three is genuinely losing his grip on reality and writing hallucinations. Jedd Mason, the madman who believes he’s God, but is probably just the delusional product of a radical set-set experiment. Caesar, the iron-proud absolute dictator seeking to do his duty by his ambitious, power-obsessed hive. Dominic, the sadistic sexual predator who nonetheless worships Jedd with fanatical devotion. Carlyle, the kind and compassionate philosopher-in-residence who inevitably gets tortured and abused. Ojiro Sniper, the freaky sex doll who nonetheless seeks to become the Brutus to Jedd’s Caesar. Apollo Mojave, the dead-but-still-influential space wizard who sought to cause a world war for stupid reasons. And so on. The characters are generally well-drawn and interesting enough that I want to see what happens to them.

I should emphasise Palmer’s achievement in making me want to know what happens to these people, especially because they’re all so unsympathetic. Carlyle and Bridger stand out as the most truly sympathetic characters in the novels, but by book three, the former has been captured, tortured, and now limps along, dead-eyed and broken-spirited, in the train of one of the resident sadists, and the latter has quite reasonably gone “Screw this” and used his immense psychic powers to delete himself from the book. But most of the core characters in this drama – Mycroft, Saladin, Jedd, Sniper, Ganymede and Danae, Madame d’Arouet, etc. – are mad, evil, both, or otherwise extremely unsympathetic. It is to Palmer’s credit that I want to know what happens in the war anyway. The most sympathetic of the political leaders in the text, Vivien Ancelet and Bryar Kosala, spend most of their time fruitlessly begging for peace. While they, perhaps alone of the leaders, have genuinely laudable intentions, it has been clear from the first book that neither will be permitted to achieve anything notable. The only people to barrack for, in Terra Ignota, are those noble if compromised few who seek to avoid a war – and who we all know will fail.

Book four, it seems, will finally be about the war that the first three books have been setting up, and even though I frankly want all three sides to lose – the Jedd faction, the Sniper faction, and Utopia are all deeply unpleasant, albeit in different ways – I am sure I will find it extremely entertaining to see how this all collapses.

Do I recommend Terra Ignota? I don’t know. If you want detailed, thorough worldbuilding, sincere contemplation of deep philosophical questions about theodicy, politics, and human nature, or a stirring vision of a possible utopia… no. Do not read it for those things. It does not have those things in it.

But it does have a scene where the prime minister of Europe body-tackles the Olympic president through a plate glass window and they land in a pile of people having sex mid-orgy, while the media broadcasts it worldwide.

And that’s excellent.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

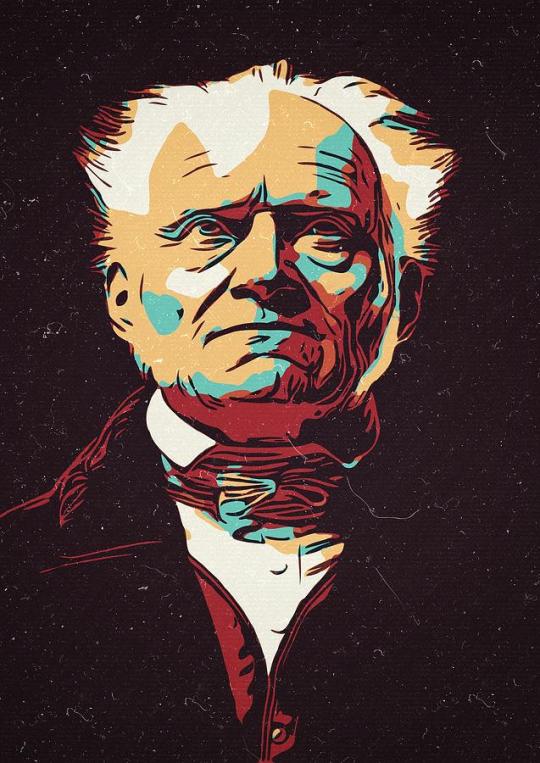

The Darkest Philosopher in History - Arthur Schopenhauer

Being one of the first philosophers to ever

really question the value of existence,

to systematically combine eastern

and western modes of thinking,

and to introduce the arts as a serious

philosophical focus, Arthur Schopenhauer

is perhaps one of the darkest and most

comprehensive philosophers in western history.

Schopenhauer was born in 1788 in what is

now Gdansk, Poland, but spent the majority

of his childhood in Hamburg, Germany after

his family moved there when he was five.

He was born to a wealthy family, his father

being a highly successful international merchant.

As a result of this, young Schopenhauer would

be expected to follow in his father’s footsteps.

However, from an early age, he had no interest

in business, and instead, found himself compelled

towards academics. And after going on a trip

around Europe with his parents to prepare him

for his merchant career, the greater exposure

he would receive to the pervasive suffering

and poverty of the world would cause him to

become all the more interested in pursuing

the path of scholarship and intellectually

examining, down to its very core, how the

world worked and why—or perhaps more accurately,

how and why it appeared to work so negatively.

After eventually going against his family’s

readymade path of international business,

Schopenhauer would attend the University of

Göttingen in 1809, where, in his third semester,

he would become more introduced and

focused on philosophy. The following year,

he would transfer to the University of Berlin

to study under a better philosophy program led

by distinguished philosophy lecturers of the

time.

However, Schopenhauer would soon find

academic philosophy to be unnecessarily obscure,

detached from real concerns of life, and often

tethered to theological agendas; all of which,

he despised. Eventually, he left the academic,

intellectual circuit, and spent the following

decade philosophizing and writing on his own.

By age thirty, Schopenhauer had published

the two works that would go on to define

his entire career, contain his complete,

unified philosophical system from which

he would never deviate, and eventually influence

the entire course of western thinking with.

The first groundwork of his philosophy

was established in his dissertation,

On the Fourfold Root of the Principle

of Sufficient Reason, published in 1813,

and his entire unified philosophical system,

including his metaphysics, epistemology, ethics,

aesthetics, value judgments, and so forth,

was laid out in his subsequent masterwork,

The World as Will and Representation, published

in 1819. Despite these impressive works going on

to hold major stake in western philosophy,

influencing some of the greatest thinkers

and schools of thought thereafter, during

this time, they would go mostly unnoticed.

Over the decades following his early

work, throughout his thirties and forties,

Schopenhauer would spend his time working to be a

lecturer at university, as well as a translator of

French to English prose, while continuing to write

on-and-off along the side. He found very little

success in all of it. His lectures were unpopular,

his translations received very little interest,

and his philosophical work remained mostly

overlooked. Only by around his fifties,

did Schopenhauer finally start to receive

any notable recognition, at all.

And only

after publishing a book of essays and aphorisms

in 1851, would he achieve the status of fame,

which he would remain in for the rest of his life

until he died in 1860 at the age of seventy-two.

In terms of Schopenhauer’s philosophical system

established within his work, it is relevant to

note that it leaned heavily on the work of his

predecessor, Immanuel Kant. In Schopenhauer’s

mind, he was completing Kant’s system of

transcendental idealism. Building off his

interpretation of Kant, Schopenhauer essentially

suggested that the world as we know and experience

it, is exclusively a representation created by our

mind through our senses and forms of cognition.

Consequently, we cannot access the true

nature of external objects outside our mental,

phenomenological experience of them. Deviating

from Kant, however, Schopenhauer would go onto to

argue that not only can we not know nor access the

varying objects of the world as they really are

outside of our conscious experience, but

there is, in fact, no plurality of objects

beyond our experience, at all. Rather, beyond

our experience is, according to Schopenhauer,

a singular, unified oneness of reality—a sort

of essence or force that drives existence

that is beyond time, beyond space, and beyond all

objectivation. Schopenhauer would go on to explore

and define this force by referencing and probing

into the experience of living within the body,

suggesting that this is the only thing

in the world that we have access to

that is not solely a mental representation of

an object but is also a firsthand, subjective

experience from within it. From here, Schopenhauer

would suggest that what is found from within,

at the core of our being, is an unconscious,

restless, striving force towards survival,

nourishment, and reproduction. He would term this

force the Will to live.

Essentially, this would

lead him to the conclusion that reality is made

up of two sides; one side being the plurality

of things as they are represented to a conscious

apparatus, and the other side being the singular,

unified force of the Will—hence the name of his

master work, The World as Will and Representation.

It is worth noting that the term Will can

perhaps be misleading in that it might seem

to imply an intention or human-like conscious

motivation, but the Will, for Schopenhauer,

is a blind, unconscious striving with no goal

or purpose other than to keep itself going

for the sake of keeping itself going. All of the

material world operates by and through this Will,

moving, striving, consuming, and violently

expressing itself in order to sustain itself.

Schopenhauer’s work was largely a response to

Kant and the western philosophical tradition,

but his work also contains distinct notes of

Hinduism and Buddhism. His conclusion of the

nature of reality is strikingly similar to that of

both. And his qualitative assessment of reality’s

negative relationship with the conscious self

mirrors ideas central to Buddhism. This made

Schopenhauer one of the first philosophers to

ever really combine eastern and western thinking

in such a systematically comprehensive way.

Especially similar to Buddhism, Schopenhauer

would top off his philosophical medley with a

layer of dark, unwavering pessimism. “Unless

suffering is the direct and immediate object of

life, our existence must entirely fail of its aim.

It is absurd to look upon the enormous amount

of pain that abounds everywhere in the world,

and originates in needs and necessities

inseparable from life itself, as serving no

purpose at all and the result of mere chance. Each

separate misfortune, as it comes, seems, no doubt,

to be something exceptional; but misfortune in

general is the rule.” Schopenhauer wrote. As a

qualitative assessment of the nature of reality,

he would describe the Will to live as a sort of

malevolent force that we, as individual selves,

become victims of in its process of continuation,

deceived by our own mind and body to go against

our fundamental interests and yearnings in order

to carry it out. Since the Will has no aim or

purpose other than its perpetual continuation,

then the will can never be satisfied. And

since we are expressions of it, neither can we.

Thus, we are driven to consume beings, things,

ideas, goals, circumstances, and all the rest,

constantly hoping we will feel a satisfaction or

happiness as result, while constantly being left

in the wake of each achievement unsatisfied.

"Human life must be some kind of mistake.

The truth of this will be sufficiently obvious if

we only remember that man is a compound of needs

and necessities hard to satisfy; and that even

when they are satisfied, all he obtains is a state

of painlessness, where nothing remains to him

but abandonment to boredom.” Schopenhauer wrote.

As the best possible ways of sort

of escaping and dealing with this,

Schopenhauer would put forth two primary methods:

one, engaging in arts and philosophy, and two, the

practicing of asceticism, traditionally being the

deprivation of nearly all desire, self-indulgence,

and everything past the bare minimum. In this

later method, Schopenhauer felt that by denying

the Will from being fed, so-to-speak, one would

turn the Will against itself and overcome it.

However, he also recognized the sheer

difficulty of this for the majority of people

and suggested the average person should

simply make their best efforts towards

letting go of ideals of happiness and pleasure,

and rather, focus on the minimization of pain.

Happiness in life, for Schopenhauer, is not

a matter of joys and pleasures, but rather,

the reduction and freedom from pain

as much as possible. “The safest way

of not being very miserable is not to

expect to be very happy.” he wrote.

Alternatively, engaging in arts and philosophy,

in Schopenhauer’s mind, served as another, more

accessible method. He felt that good art could

provide a source of clarity into the nature and

problems of being, without any of the illusion or

drapery. And while engaging in this sort of art,

one would have a transcendent-like experience

that provides a relief and comfort from existence.

As a result of this concept,

Schopenhauer would end up being one

of first thinkers to ever really introduce

philosophical significance to the arts,

and would eventually become known by

many as the ‘artist’s philosopher.’

Of course, throughout his work in general,

Schopenhauer makes large, often unprovable,

and unknowable claims about the nature of reality

and the value of existing within it. Some of which

is validly constructed and worth considering,

but some of which is likely not. Ultimately,

any attempt to define and assess the side of

reality beyond logic and reason through systematic

logic and reason is perhaps paradoxical in way

that is beyond repair. What precisely is the Will,

where does it come from, where does it

end, and how can we know or prove it?

And in terms of Schopenhauer’s suggestion

that one should turn against the Will

through an ascetic process of self-denial,

if all of life operates through the Will,

to turn against it, would seem to merely be the

Will turning against the Will for reasons that

favor it. And there can be no turning against

the Will if the Will is doing the turning.

Alternatively, considering the view of Friedrich

Nietzsche, a philosopher who notably followed in

Schopenhauer’s footsteps, the endless cycle of

desire and dissatisfaction caused by the Will

is actually a good thing that we can use as fuel

towards the process of self-overcoming and growth,

which we can then obtain life’s meaning

from. Of course, this is the more pleasant

of the two interpretations, but it isn’t clear

which is more apt and/or accurate, if either.

Ultimately, Schopenhauer is another surprising,

yet seemingly common story where a highly

important thinker, artist, or writer, barely

caught any recognition in their life, if at all,

only to die and end up with their name in

nearly every history book on the subject.

One trait these stories do all

seem to have in common, though,

is a refusal to stop, a refusal to budge from

pursuing and defending the world as one sees it.

Schopenhauer never deviated from the

philosophical system he created in his twenties

and never stopped confidently working to build

upon it and reinforce it throughout his life,

despite the world seeming to suggest to

him he should do otherwise. And yet, now,

it is hugely significant to the world that he did

exactly what he did. For some, his work might be

bleak and disconcerting, but for others, his work,

like all great works of dark, melancholic honesty,

is comforting, relieving, and legitimizing. It

reminds us that are not crazy, and our sadness

and suffering are not unfounded, even when they

may feel like it. We are merely put in a crazy,

sad, violent reality with a mind and body

that are often all in conspiracy against us.

Because of this and many other reasons

unmentioned, his work would go on to

influence artists like Richard Wagner and Gustav

Mahler; writers like Marcel Proust, Leo Tolstoy,

and Samuel Beckett; and thinkers like Friedrich

Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud, and Ludwig Wittgenstein,

as well as many others, ultimately influencing

the course of modern thinking, forever.

Having been one of the first to properly

and philosophically bring the value of life

and the possibility of meaning into question,

Schopenhauer helped locate the early budding

problem of the growing agnostic world

that philosophy would need to address.

With humanity seemingly suspending

further out into a void of meaning,

his unyielding and fearless confrontation with

the nature of existence, including all its

horrors and miseries, revealed an opening of new

possibilities towards finding answers from within.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you elaborate on Erusamus and the reformation please, or at least point me toward sources? Politics make more sense than philosophy to me, so I see the reformation through the lense of Henry VIII, or the Duke of Prussia who dissolved the teutonic order, or France siding with the protestants during the 30 Years War because Protestants > Hapsburgs

So sorry to take so long!

If you needed this answer for academic reasons, given that summer term is pretty much done I’m probably too late to help, but I hate to leave an ask unanswered.

HELLA LONG ESSAY BENEATH THE CUT SORRY I WROTE SELF-INDULGENTLY WITHOUT EDITING SO THERE IS WAY MORE EXPLANATION THAN YOU PROBABLY NEED

Certainly religion has been politicised, you need look no further than all the medieval kings having squabbles with the pope. Medieval kings were not as devastated by the prospect of excommunication as you’d expect they’d be in a super-devout world, it was kinda more of a nuisance (like, idk, the pope blocking you on tumblr) than the “I’m damned forever! NOOOOOOO!” thing you’d expect. I’m not saying excommunication wasn’t a big deal, but certainly for Elizabeth I she was less bothered than the pope excommunicating her than the fact that he absolved her Catholic subjects of allegiance to her and promised paradise to her assassin (essentially declaring open season on her).

I think, however, in our secular world we forget that religion was important for its own sake. Historians since Gibbon have kind of looked down on religion as its own force, seeing it as more a catalyst for economic change (Weber) or a tool of the powerful. If all history is the history of class struggle, then religion becomes a weapon in class warfare rather than its own force with its own momentum. For example, historians have puzzled over conversion narratives, and why Protestantism became popular among artisans in particular. Protestantism can’t compete with Catholicism in terms of aesthetics or community rituals, it’s a much more interior kind of spirituality, and it involves complex theological ideas like predestination that can sound rather drastic, so why did certain people find it appealing?

(although OTOH transubstantiation is a more complex theological concept than the Protestant idea of “the bread and wine is just bread and wine, it’s a commemoration of the Last Supper not a re-enactment, it aint that deep fam”).

I’ve just finished an old but interesting article by Terrence M. Reynolds in Concordia Theological Quarterly vol. 41 no. 4 pp.18-35 “Was Erasmus responsible for Luther?” Erasmus in his lifetime was accused of being a closet Protestant, or “laying the egg that Luther hatched”. Erasmus replied to this by saying he might have laid the egg, but Luther hatched a different bird entirely. Erasmus did look rather proto Protestant because he was very interested in reforming the Church. He wanted more people to read the Bible, he had a rather idyllic dream of “ploughmen singing psalms as they ploughed their fields”. He criticised indulgences, the commercialisation of relics and pilgrimages and the fact that the Papacy was a political faction getting involved in wars. He was worried that the rituals of Catholicism meant that people were more mechanical in their religion than spiritual: they were memorising the words, doing the actions, paying the Church, blindly believing anything a poorly educated priest regurgitated to them. They were confessing their sins, doing their penances like chores and then going right back to their sins. They were connecting with the visuals, but not understanding and spiritually connecting with the spirit of Jesus’ message and his ideals of peace and love and charity and connecting with God. Erasmus translated the NT but being a Renaissance humanist, he went ad fontes (‘to the source’) and used Greek manuscripts, printing the Greek side by side with the Latin so that readers could compare and see the translation choices he made. His NT had a lot of self-admitted errors in it, but it was very popular with Prots as well as Caths. Caths like Thomas More were cool with him doing it, but it was also admired by Prots like Thomases and Cromwell and Cranmer and Tyndale himself. When coming across Greek words like presbyteros, Erasmus actually chose to leave it as a Greek word with its own meaning than use a Latin word that didn’t *quite* fit the meaning of the original.

However, he did disagree with Protestants on fundamental issues, especially the question of free will. For Luther, the essence was sole fide: salvation through faith alone. He took this from Paul’s letter to the Romans, where it says that through faith alone are we justified. Ie, humans are so fallen (because of the whole Eve, apple, original sin debacle) and so flawed and tainted by sin, and God is so perfect, that we ourselves will never be good enough. All the good works in the world will never reach God’s level of perfection and therefore we all deserve Hell, but we won’t go to hell because God and Jesus will save us from the Hell we so rightly deserve, by grace and by having faith in Jesus’ sacrifice, who will alone redeem us. The opposite end of the free will/sola fide spectrum is something called Pelagianism, named after the guy who believed it, Pelagius, who lived centuries and centuries before the Ref, it’s the belief that humans can earn their salvation by themselves, by good works. Both Caths and Prots considered Pelagius a heretic. Caths like Erasmus believed in a half-way house: God reaches out his hand to save you through Jesus’ example and sacrifice, giving you grace, and you receive his grace, which makes you want to be a good person and do good works (good works being things like confession of sins, penances, the eucharist, charity, fasting, pilgrimages) and then doing the good works means you get more grace and you are finally saved, or at least you will go to purgatory after death AND THEN be saved and go to heaven, rather than going straight to Hell, which is what happens if you reject Jesus and do no good works and never repent your sins. If you don’t receive his grace and do good works, you won’t make the grade for ultimate salvation.

(This is why it’s important to look at the Ref as a theological as well as a political movement because if you only look at the political debates, Erasmus looks more Protestant than he actually was.)

There are several debates happening in the Reformation: the role of the priest (which is easily politicised) free will vs predestination, transubstantiation or no transubstantiation (is or isn’t the bread and wine transformed into the body and blood of Jesus by God acting through the priest serving communion) and the role of scripture. A key doctrine of Protestantism is sola scriptura. Basically: if it’s in the Bible, it’s the rules. If it’s not in the Bible, it’s not in the rules. No pope in the bible? No pope! No rosaries in the bible? No using rosaries! (prayer beads)

However, both Caths and Prots considered scripture v.v. important. Still, given that the Bible contains internal contradictions (being a collection of different books written in different languages at different times by different people) there was a hierarchy of authority when it came to scripture. As a general rule of thumb, both put the New T above the Old T in terms of authority. (This is partly why Jews and Muslims have customs like circumcision and no-eating-pig-derived-meats that Christians don’t have, even though the order of ‘birth’ as it were goes Judaism-Christianity-Islam. All 3 Abrahammic faiths use the OT, but only Christians use the NT.)

1. The words of Jesus. Jesus said you gotta do it, you gotta do it. Jesus said monogamy, you gotta do monogamy. Jesus said no divorce, you gotta do no divorcing (annulment =/= divorce). Jesus said no moneylending with interest (usury), you gotta do no moneylending with interest (which is partly why European Jews did a lot of the banking. Unfortunately, disputes over money+religious hatred is a volatile combination, resulting in accusations of conspiracy and sedition, leading to hate-fuelled violence and oppression.) The trouble with the words of Jesus is that you can debate or retranslate what Jesus meant, especially easily as Jesus often spoke in parables and with metaphors. When Jesus said “this is my body…this is my blood” at the Last Supper, is that or is that not support for transubstantiation? When Jesus called Peter the rock on which he would build the church, was that or was that not support for the apostolic succession that means Popes are the successor to St Peter, with Peter being first Pope? When the gospel writers said Jesus ‘did more things and said more things than are contained in this book’, does that or does that not invalidate the idea of sola scriptura?

2. The other New Testament writers, especially St. Paul and the Relevation of St John the Divine. (Divine meaning like seer, divination, not a god or divinity). These are particularly relevant when it comes to discussing the role of priests and priesthood, only-male ordination, and whether women can preach and teach religion.

3. The Old Testament, especially Genesis.

4. The apocryphal or deuterocanonical works. These books are considered holy, but there’s question marks about their validity, so they’re not as authoritative as the testaments. I include this because the deuterocanonical book 2 Maccabees was used as scriptural justification for the Catholic doctrine of purgatory, but 2 Maccabees is the closest scipture really gets to mentioning any kind of purgatory. Protestants did not consider 2 Maccabees to be strong enough evidence to validate purgatory.

5. The Church Fathers, eg. Origen, Augustine of Hippo. Arguably their authority often comes above apocryphal scripture. It’s from the Church Fathers that the concept of the Trinity (one god in 3 equal persons, God the Father, God the Son, God the Holy Spirit) is developed because it’s not actually spelled out explicitly in the NT. Early modern Catholics and Protestants both adhered to the Trinity and considered Arianism’s interpretation of the NT (no trinity, God the Father is superior to Jesus as God the Son) to be heresy. Church Fathers were important to both Catholics and Protestants: Catholics because Catholics did not see scripture as the sole source of religious truth, so additions made by holy people are okay so long as they don’t *contradict* scripture, and so long as they are stamped with the church council seal of approval, Protestants because they believed that the recent medieval theologians and the papacy had corrupted and altered the original purity of Christianity. If they could show that Church Fathers from late antiquity like Augustine agreed with them, that therefore proved their point about Christianity being corrupted from its holy early days.

Eamon Duffy’s book Stripping of the Altars is useful because it questions the assumptions that the Reformation and Break with Rome was inevitable, or that the Roman Catholic Church was a corrupt relic of the past that had to be swept aside for Progress, or that most people even wanted the Ref in England to happen. Good history essays need to discuss different historians’ opinions and Duffy can be relied upon to have a different opinion than Protestant historians. Diarmaid MacCulloch’s works are good at explaining theological concepts, he is a big authority on church history and he’s won a whole bunch of prizes. He was actually ordained a deacon in the Church of England in the 1980s but stopped being a minister because he was angry with the institution for not tolerating the fact he had a boyfriend. The ODNB is a good source to access through your university if you want to read a quick biography on a particular theologian or philosopher, but it only covers British individuals. Except Erasmus, who has a page on ODNB despite being not British because he’s just that awesome and because his influence on English scholarship and culture was colossal. Peter Marshall also v good, esp on conversion. Euan Cameron wrote a mahoosive book called the European Reformation.“More versus Tyndale: a study of controversial technique” by Rainer Pineas is good for the key differences in translation of essential concepts between catholic and protestant thinkers. The Sixteenth Century Journal is a good source of essays as well.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aristotle's Collection [ 29 Books] - Publish This

Aristotle's Collection [ 29 Books] Publish This Genre: Philosophy Price: $0.99 Publish Date: June 27, 2011 Publisher: Publish This, LLC Seller: Publish This, LLC This contain collection of 29 Books 1. Categories translated by E. M. Edghill 2. On Interpretation translated by E. M. Edghill 3. Prior Analytics translated by A. J. Jenkinson 4. Posterior Analytics translated by G. R. G. Mure 5. Topics translated by W. A. Pickard-Cambridge 6. On Sophistical Refutations translated by W. A. Pickard- Cambridge 7. Physics translated by R. P. Hardie and R. K. Gaye 8. On the Heavens translated by J. L. Stocks 9. On Generation and Corruption translated by H. H. Joachim 10. Meteorology translated by E. W. Webster 11. On the Soul translated by J. A. Smith 12. On sense and the sensible translated by J. I. Beare 13. On memory and reminiscence translated by J. I. Beare 14. On Dreams translated by J. I. Beare 15. On prophesying by dreams translated by J. I. Beare 16. On longevity and shortness of life translated by G. R. T. Ross 17. On Youth, Old Age, Life and Death, and Respiration translated by G. R. T. Ross 18. The History of Animals translated by D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson 19. On the parts of Animals translated by William Ogle 20. On the motion of animals translated by A. S. L. Farquharson 21. On the Gait of Animals translated by A. S. L. Farquharson 22. On the Generation of Animals translated by Arthur Platt 23. Metaphysics translated by W. D. Ross 24. Nicomachean Ethics translated by W. D. Ross 25. Politics translated by Benjamin Jowett 26. The Athenian Constitution translated by Sir Frederic G. Kenyon 27. Rhetoric translated by W. Rhys Roberts 28. Poetics translated by S. H. Butcher 29. On sleep and sleeplessness translated by J. I. Beare About the Author Aristotle (Greek: Ἀριστοτέλης, Aristotélēs) (384 BC – 322 BC) was a Greek philosopher, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. He wrote on many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, politics, government, ethics, biology and zoology. Together with Plato and Socrates, Aristotle is one of the most important founding figures in Western philosophy. He was the first to create a comprehensive system of Western philosophy, encompassing morality and aesthetics, logic and science, politics and metaphysics. Aristotle's views on the physical sciences profoundly shaped medieval scholarship, and their influence extended well into the Renaissance, although they were ultimately replaced by Newtonian Physics. In the biological sciences, some of his observations were confirmed to be accurate only in the nineteenth century. His works contain the earliest known formal study of logic, which was incorporated in the late nineteenth century into modern formal logic. In metaphysics, Aristotelianism had a profound influence on philosophical and theological thinking in the Islamic and Jewish traditions in the Middle Ages, and it continues to influence Christian theology, especially Eastern Orthodox theology, and the scholastic tradition of the Catholic Church. All aspects of Aristotle's philosophy continue to be the object of active academic study today. Though Aristotle wrote many elegant treatises and dialogues (Cicero described his literary style as "a river of gold"), it is thought that the majority of his writings are now lost and only about one-third of the original works have survived. http://dlvr.it/R5x5YH

0 notes

Text

Acid Communism, by Mark Fisher (k-punk)

“The spectre of a world which could be free”

“[T]he closer the real possibility of liberating the individual from the constraints once justified by scarcity and immaturity, the greater the need for maintaining and streamlining these constraints lest the established order of domination dissolve. Civilisation has to protect itself against the spectre of a world which could be free.

[…] In exchange for the commodities that enrich their lives […] individuals sell not only their labour but also their free time. […] People dwell in apartment concentrations — and have private automobiles with which they can no longer escape into a different world. They have huge refrigerators stuffed with frozen foods. They have dozens of newspapersand magazines which espouse the same ideals. They have innumerable choices, innumerable gadgets which are all of the same sort and keep them occupied and divert their attention from the real issue — which is the awareness that they could both work less and determine their own needs and satisfactions.” — Herbert Marcuse, Eros and Civlisation

The claim of the book is that the last forty years have been about the exorcising of “the spectre of a world which could be free”. Adopting the perspective of such a world allows us to reverse the emphasis of much recent left-wing struggle. Instead of seeking to overcome capital, we should focus on what capital must always obstruct: the collective capacity to produce, care and enjoy. We on the left have had it wrong for a while: it is not that we are anti-capitalist, it is that capitalism, with all its visored cops, its teargas, and all the theological niceties of its economics, is set up to block the emergence of this Red Plenty. The overcoming of capital has to be fundamentally based on the simple insight that, far from being about “wealth creation”, capital necessarily and always blocks the production of common wealth.

The principal, though by no means the sole, agent involved in the exorcism of the spectre of a world which could be free is the project that has been called neoliberalism. But neoliberalism’s real target was not its official enemies — the decadent monolith of the Soviet bloc, and the crumbling compacts of social democracy and the New Deal, which were collapsing under the weight of their own contradictions. Instead, neoliberalism is best understood as a project aimed at destroying — to the point of making them unthinkable — the experiments in democratic socialism and libertarian communism that were efflorescing at the end of the Sixties and the beginning of the Seventies.

The ultimate consequence of the elimination these possibilities was the condition I have called capitalist realism — the fatalistic acquiescence in the view that there is no alternative to capitalism. If there was a founding event of capitalist realism, it would be the violent destruction of the Allende government in Chile by General Pinochet’s American-backed coup. Allende was experimenting with a form of democratic socialism which offered a real alternative both to capitalism and to Stalinism. The military destruction of the Allende regime, and the subsequent mass imprisonments and torture, are only the most violent and dramatic example of the lengths capital had to go to in order to make itself appear to be the only “realistic” mode of organising society. It wasn’t only that a new form of socialism was terminated in Chile; the country also became a lab in which the measures which would be rolled out in other hubs of neoliberalism (financial deregulation, the opening up of the economy to foreign capital, privatisation) were trialled. In countries like the US and the UK, the implementation of capitalist realism was a much more piecemeal affair, involving inducements and seductions as well as repression. The ultimate effect was the same — the extirpation of the very idea of democratic socialism or libertarian communism.

The exorcising of the “spectre of a world which could be free” was a cultural as well as a narrowly political question. For this spectre, and the possibility of a world beyond toil, was raised most potently in culture — even, or perhaps especially, in culture which didn’t necessarily think of itself as politically-orientated.

Marcuse explains why this is the case, and the declining influence of his work in recent years tells its own story. One-Dimensional Man, a book which emphasises the gloomier side of his work, has remained a reference point, but Eros and Civilisation, like many of his other works, has long been out of print. His critique of capitalism’s total administration of life and subjectivity continued to resonate; whereas the claims Marcuse’s conviction that art constituted a “Great Refusal, the protest against that which is”3 came to seem like outmoded Romanticism, quaintly irrelevant in the age of capitalist realism. Yet Marcuse had already forestalled such criticisms, and the critique in One-Dimensional Man has traction because it comes from a second space, an “aesthetic dimension” radically incompatible with everyday life under capitalism. Marcuse argued that, in actuality, the “traditional images of artistic alienation” associated with Romanticism do not belong to the past. Instead, he said, in… formulation, they “recall and preserve in memory belongs to the future: images of a gratification that would destroy the society that suppresses it.”4

The Great Refusal rejected, not only capitalist realism, but “realism” as such. There is, he wrote, an “inherent conflict between art and political realism”.5 Art was a positive alienation, a “rational negation” of the existing order of things. His Frankfurt School predecessor, Theodor Adorno, had placed a similar value on the intrinsic alterity of experimental art. In Adorno’s work, however, we are invited to endlessly examine the wounds of a damaged life under capital; the idea of a world beyond capital is despatched into a utopian beyond. Art only marks our distance from this utopia. By contrast, Marcuse vividly evokes, as an immediate prospect, a world totally transformed. It was no doubt this quality of his work that meant Marcuse was taken up so enthusiastically by elements of the Sixties counterculture. He had anticipated the counterculture’s challenge to a world dominated by meaningless labour. The most politically significant figures in literature, he argued in One-Dimensional Man, were “those who don’t earn a living, at least not in an ordinary and normal way”.6 Such characters, and the forms of life with which they were associated, would come to the fore in the counterculture.

Actually, as much as Marcuse’s work was in tune with the counterculture, his analysis also forecast its ultimate failure and incorporation. A major theme of One-Dimensional Man was the neutralisation of the aesthetic challenge. Marcuse worried about the popularisation of the avant-garde, not out of elitist anxieties that the democratisation of culture would corrupt the purity of art, but because the absorption of art into the administered spaces of capitalist commerce would gloss over its incompatibility with capitalist culture. He had already seen capitalist culture convert the gangster, the beatnik and the vamp from “images another way of life” into “freaks or types of the same life”.7 The same would happen to the counterculture, many of whom, poignantly, preferred to call themselves freaks.

In any case, Marcuse allows us to see why the Sixties continue to nag at the current moment. In recent years, the Sixties have come to seem at once like a deep past so exotic and distant that we cannot imagine living in it, and a moment more vivid than now — a time when people really lived, when things really happened. Yet the decade haunts not because of some unrecoverable and unrepeatable confluence of factors, but because the potentials it materialised and began to democratise — the prospect of a life freed from drudgery — has to be continually suppressed. To explain why we have not moved to a world beyond work we have to look at a vast social, political and cultural project whose aim has been the production of scarcity. Capitalism: a system that generates artificial scarcity in order to produce real scarcity; a system that produces real scarcity in order to generate artificial scarcity. Actual scarcity — scarcity of natural resources — now haunts capital, as the Real that its fantasy of infinite expansion must work overtime to repress. The artificial scarcity — which is fundamentally a scarcity of time — is necessary, as Marcuse says, in order to distract us from the immanent possibility of freedom. (Neoliberalism’s victory, of course, depended upon a cooption of the concept of freedom. Neoliberal freedom, evidently, is not a freedom from work, but freedom through work.)

Just as Marcuse predicted, the availability of more consumer goods and devices in the global North has obscured the way in which those same goods have increasingly functioned to produce a scarcity of time. But perhaps even Marcuse could not have anticipated twenty-first-century capital’s capacity to generate overwork and to administer the time outside paid work. Maybe only a mordant futurologist like Philip K. Dick could have predicted the banal ubiquity of corporate communication today, its penetration into practically all areas of consciousness and everyday life.

“The past is so much safer”, observes one of the narrators of Margaret Atwood’s dystopian satire, The Heart Goes Last, ���because whatever’s in it has already happened. It can’t be changed: so, in a way there’s nothing to dread”.8 Despite what Atwood’s narrator thinks, the past hasn’t “already happened”. The past has to be continually re-narrated, and the political point of reactionary narratives is to suppress the potentials which still await, ready to be re-awakened, in older moments. The Sixties counterculture is now inseparable from its own simulation, and the reduction of the decade to “iconic” images, to “classic” music and to nostalgic reminiscences has neutralised the real promises that exploded then. Those aspects of the counterculture which could be appropriated have been repurposed as precursors of “the new spirit of capitalism”, while those which were incompatible with a world of overwork have been condemned as so many idle doodles, which in the contradictory logic of reaction, are simultaneously dangerous and impotent.

The subduing of the counterculture has seemed to confirm the validity of the scepticism and hostility to the kind of position Marcuse was advancing. If “the counterculture led to neoliberalism”, better that the counterculture had not happened. In fact, the opposite argument is more convincing — that the failure of the left after the Sixties had much to do with its repudiation of, or refusal to engage with, the dreamings that the counterculture unleashed. There was no inevitability about the new right’s seizure and binding of these new currents to its project of mandatory individualisation and overwork.What if the counterculture was only a stumbling beginning, rather than the best that could be hoped for?

What if the success of neoliberalism was a not an indication of the inevitability of capitalism, but a testament to the scale of the threat posed by the spectre of a society which could be free?

It is in the spirit of these questions that this book shall return to the 1960s and 1970s. The rise of capitalist realism could not happened without the narratives that reactionary forces told about those decades. Returning to those moments will allow us to continue with the process of unpicking the narratives that neoliberalism has woven around them. More importantly, it will enable the construction of new narratives.