#especially cownose rays

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Round 3 - Chondrichthyes - Myliobatiformes

(Sources - 1, 2, 3, 4)

Our first order of rays are the Myliobatiformes, or “Stingrays.” This order includes the families Zanobatidae (“panrays”), Hexatrygonidae (“Sixgill Stingray”), Dasyatidae (“whiptail stingrays”), Potamotrygonidae (“river stingrays”), Urotrygonidae (“American round rays”), Gymnuridae (“butterfly rays”), Plesiobatidae (“Deepwater Stingray”), Urolophidae (“round rays”), Aetobatidae (“pelagic eagle rays”), Myliobatidae (“eagle rays”), Rhinopteridae (“cownose rays”), and Mobulidae (“devil rays”).

Myliobatiformes are characterized by their enlarged, expanded pectoral fins being completely fused to their head and body, called a “disc”. Their disc shape ranges from diamond to subrhombic to lozenge-shaped. They are also characterized by the presence or absence of a single small dorsal fin, a long whip-like tail, and one or more stinging spines on the upper tail base (some species have secondarily lost this spine). As a defense mechanism, stingrays will flail their pointed or barbed tails and lodge the spine within a potential predator while they escape. The spine eventually grows back. As rays, their eyes and spiracles are on the dorsal side of their body while their gill slits, nostrils, and mouth are on the ventral side. Most myliobatiformes have blunt, pavement-like teeth for crushing hard-shelled prey and bony fish, though Manta Rays are planktonivore filter-feeders. They give birth to live young, usually 1-10 per litter, depending on species. This is a highly diverse group, and the second largest order of batoids (rays).

Myliobatiformes arose in the Early Cretaceous.

Propaganda under the cut:

Most stingrays are not aggressive if left alone, and some are even curious and friendly. The Cownose Rays (Rhinoptera) especially are known for this behavior, and are often the species of choice for touch tanks in public aquariums, as they will actively seek out attention. In my family’s experience, my sisters and mother were swimming in the ocean two Summers ago, and my sister patted what she thought was my mom’s foot after it bumped her on the back. She then realized it was a Cownose Ray (Rhinoptera bonasus) when another one tripped my other sister! A school of them was playing in the shallows and had decided to mess with my family. (I only ever get pinched by crabs and spooked by jellies when I enter the ocean ;_;)

Uniquely for its family, the Porcupine Ray (Urogymnus asperrimus) lacks a venomous tail spine. Instead, it defends itself with the many large, sharp thorns found over its disc and tail. Due to its thorny hide, this now endangered ray has historically been a very valuable source of shagreen.

The Giant Oceanic Manta Ray (Mobula birostris) is the largest stingray, growing up to 9 m (30 ft) long, 7 m (23 ft) wide, and weighing about 3,000 kg (6,600 lb), though the average size commonly observed is half that.

Around 35 cm (14 in) in width, the Bluespotted Ribbontail Ray (Taeniura lymma) is one of the most venomous species of stingray and is known to have an excruciating sting. Nevertheless, it is popular with home aquarists for its small size and beautiful coloration. Despite this, it is not well suited for captivity, being a very shy species and prone to refusing to feed. Seldom have hobbyists been able to keep one alive for long in home aquariums. Professional, public aquariums have had much better luck with the species, even maintaining breeding programs.

The composition of venom in freshwater stingrays appears to differ from that of marine stingrays.

Stingrays that live in the deep sea, such as the Deepwater Stingray (Plesiobatis daviesi) and the Sixgill Stingray (Hexatrygon bickelli) are flabby and almost goopy, with a skate-like appearance. The deep sea changes folks.

When threatened, the Crossback Stingaree (Urolophus cruciatus) raises its tail over its disc like a scorpion, as a warning.

Spotted Eagle Rays (Aetobatus narinari) sport 2-6 venomous, barbed spines at a time, but the most danger they have presented to humans so far is via their leaping from the water at the wrong place/wrong time! On at least two occasions Spotted Eagle Rays have been reported as having jumped into boats, and in one incident this sadly resulted in the death of a woman in the Florida Keys. Otherwise, these rays appear to be curious about humans and will sometimes slow down to inspect snorkelers if the human is not acting threatening.

The Chilean Devil Ray (Mobula tarapacana) is one of the deepest-diving ocean animals, traveling from the surface to feed at depths of up to 1,896 metres (6,220 ft). A veined structure of blood vessels warms the ray's brain at colder depths. These rays stay near warmer surface water for at least an hour both before and after deep diving, suggesting that they are soaking up heat to prepare for and recover from their descent into colder water.

Manta Rays (genus Mobula) are incredibly smart. They were the first “fish” in the world to pass the “mirror test” (ie show self-awareness by recognizing themselves in a mirror rather than seeing the reflected image as another manta ray). They also have highly-developed long-term memory, form friendships, and play with each other by blowing bubbles and breaching out of the water.

Steve Irwin’s death was a freak accident. He was swimming and passed overtop a 2 m (6.7 ft) long Short-tail Stingray (Bathytoshia brevicaudata), and the animal reacted reflexively to his shadow by stabbing its barbed tail repeatedly into what it perceived as a predator. By an insane stroke of bad luck, the spine from the stingray’s tail pierced right through into Steve’s chest. (And no, the barb did not become lodged and he didn’t pull it out; that’s a rumor. Venom or no, there’s not much you can do about being stabbed in the heart.) Fatal stings are very rare, and only around 20 stingray-related deaths have been recorded in history. Steve loved all animals and would not have wanted people to hold his death against literally all species of stingray, let alone the single one that accidentally took his life. Even as a joke, using Steve Irwin to hate on an animal does a great disservice to his legacy. So if I hear a word of stingray-hate in Steve’s name, I’m calling the guards. >:C

#let me be clear you’re allowed to dislike them but I am so very tired of seeing comments of people bringing up#’getting revenge for Steve Irwin’ or ‘hate stingrays for what they did to Steve’ every time a stingray is mentioned#I don’t care if it’s a joke it’s on ‘if it doesn’t scan does that mean it’s free’ levels of funny to me but worse because it’s on a whole#new level of comically missing the point and spitting on the ashes of the dead to boot#You may dislike the Sea Pancakes but you MAY NOT take Steve’s name In Vain about it#round 3#animal polls#chondrichthyes

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

In my defense sting ray slime. Even though they did get the art incorrect.

ok so I did spend sixty dollars buying slime. nobody talk to me

#basically the art on the label depicts the face of a manta ray which aren't found in touch tanks#and the shape is cownose ray like- especially because cownose rays are by far the most common touch tank ray it makes sense that it would b#depicting a cownose ray#but cow nose rays don't have that face shape+they don't have spots+theyre not blue#the charm does get the face shape right. :3 face is very important

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

Sometimes I see you on my dash doing a science and it makes me happy and do you have any shark facts pls? Sharks are so cool. Especially the weird deep sea sharks that always get ignored when ppl talk about great whites and such (no shame to great whites they are very lovable,)

Of course I have quite a lot!

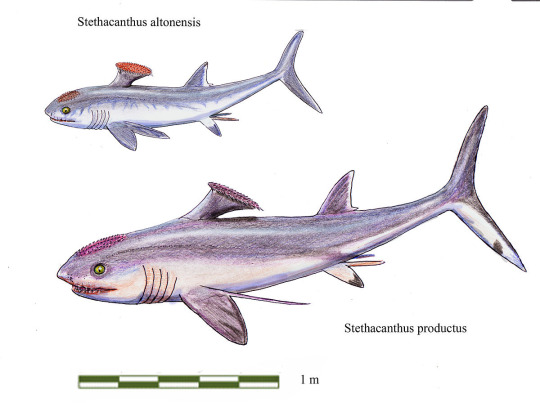

Okay so we can start with the first shark ancestors, the spiny sharks! They lived in the Silurian, more than 400 million years ago. They looked pretty unique as each fin was actually a spine supporting the whole fin, and had already reacquired the cartilaginous skeleton that modern sharks have!

Nobu Tamura / CC BY-SA 4.0

They often had a bunch of little pairs of "finlets" (not real fins, but spines serving a similar purpose) between their actual fins! So spiky!

Then we come to the true sharks (and rays). Or, nearly. Turns out, there are two main groups of shark-like cartilaginous fish alive today. On the one hand the sharks and rays, and on the other hand the chimeras, majestic creatures often found in the deep sea!

Havforskingsinstituttet / CC BY-SA 4.0

Turns out however, the ancestors of chimeras were historically way more shark-like! And ranged between adorable and pretty weird, and more often than not both! Here's one of them: the sawblade shark, Helicoprion!

Entelognathus / CC BY-SA 4.0

And here's the anvil shark!

DiBgd / CC BY-SA 4.0

And the wtfshark, Squaloraja!

Nix Illustrations / I don't know the license but he's on Tumblr

And now we can move on to the actual sharks. And rays. And sawsharks. And sawfish. And sawskates. The design so good they had to invent it thrice.

Here's a sawfish (these ones are closer to rays!), heavily judging whoever took the photograph. Surprisingly, they're the largest of the bunch, reaching up to 7 meters - while sawsharks are barely a meter in length at best, and sawskates aren't alive anymore but could reach a respectable 4 meters! (although they were wider relative to their size, which has to count for something?)

Simon Fraser University - University Communications / CC BY 2.0

Now that we saw the saws, we can move on to actual sharks... wait what's that? An interruption by the coolest species of six-finned ray?

Robert Fisher, Virginia Sea Grant / CC BY-ND 2.0

Seems like it. Of course I had to mention my favourite cartilaginous fish in the bunch. Cownose rays (and their manta ray cousins) are the only vertebrates to have developed an entire new pair of fins - on their face, to help them grab stuff! Since fish paired fins are homologous to our limbs, it would be like having an extra pair of arms coming from our face!

Robert Fisher, Virginia Sea Grant / CC BY-ND 2.0

Back to sharks now (finally)! And speaking of stuff it's rare to have six of, what about sixgill sharks?

No author information / Public domain

The most divergent group of true sharks alive today, the deep-sea creatures that we call frilled sharks are actually very derived, despite their prehistoric appearance! Ironically, their more ordinary-looking sixgill cousins, the cow sharks, are more representative of how sharks started off back in the days!

NOAA / Public domain

Still six gills because why not. Or even seven, because really, why not.

Next step on our shark list (and back to the regular five-gill pattern), the angelsharks! Or sand devils, because they really couldn't decide on these ones. Angels or devils, they're absolutely adorable pancakes.

Nick Long / CC BY-SA 2.0

Now, we would still have five more orders of sharks to go, but these are the pretty well-known ones (great white shark, hammerhead shark, etc.) and this post is getting pretty big, so I'm happy to have presented cool unique ones already! Have a nice day, and don't forget - there are always more shark species to learn about!

153 notes

·

View notes

Text

List of random obscure stuff I'm fascinated with for no reason, or maybe there is a reason, but I'm too tired to figure it out:

1. Small spaces that aren't really safe given the overall environment, but that still feels safe for whatever reason. (Ex. 2D's underwater room from Plastic Beach, my own room, horror game safe rooms, the backseat of cars driving at night.)

2. The cold. Any version. The Arctic, snow in Texas, the sound of a box fan in the middle of winter. Snow. I like the cold. I like walking in it and having it surround me.

3. Blue noise. The ambiance noise. It's my favorite kind. It sounds cold. Ain't that neat?

4. Early 2000s nostalgia. This one's more understandable, considering I grew up in the 2000s. Particularly focused on the technology because young me was a big fan of the 'puter. Throw in a DS, and I'm sold.

5. Nautical stuff. I know next to nothing about sailing, but you bet your ass I love me some boats and sailors. Oh, or lighthouses and lighthouse keepers. Not so much pirates as just old people sailing boats. Make it cold and thats even better. Like that one oil rig horror game? Loved it. The ocean is cool too sometimes. Especially stingrays. Love em. You know what actually?

6. Stingrays. Funny dudes. Favorite animal. Any kind of ray, really. Mantaray, eagle ray, cownose ray... I think they're very cool.

7. Carousels. I like the pretty horses, fucking sue me. I'd like to design them, especially the ones with all types of animals. The ones on boardwalks or outside aquariums in particular are very cool because they have all the sea creatures.

#idk what to even tag this#hyper fixations#hyper fixation#current fixation#lists#i just like making lists

8 notes

·

View notes

Conversation

Stingray Feeding Time

Me: Hi sweet nuggets! Time for dinner!

Cownose rays: *nom nom nom*

Me: Ok, this was great...

Rays: As is custom with our peoples, we must grant the provider of nomz a splash in the face

Me: Really, no, that's not necessa-

Rays: WE MUST. DO. THE SPLASHY SPLASH!!!

#dammit#every time#rays are ridiculous#especially cownose rays#savages#but i love them#aquarist#aquarist life#always covered in water#cownose ray#stingray#Rhinoptera bonasus#elasmobranch#pancake sharks#aquarium#marine biology#i think i'm funny#sea nerd

437 notes

·

View notes

Note

aang! 💨 katara! 🌊 yue! 🌙

So this got really really long. Sorry y’all.

Aang (what makes me happy): getting asks, hehe ;) but in all seriousness...

writing, reading books that I truly enjoy, fiction and fandom and storytelling in general. Getting caught up in a story that makes me feel like a part of something more important than my own life. Baked goods, all types, both making and consuming. Shipping things. The retreats and praise/worship sessions we used to do at my high school. Going to Disneyland. The cereal aisle at the grocery store. Mochi ice cream. aesthetically pleasing salads. The Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto. (Really, all violin concertos that aren’t baroque or the weird 20th century ones.) Rediscovering things I loved as a kid and finding that I still love them now. Road trips. Anything with a Marvel logo on it. Bookstores. Thunderstorms. Watching figure skating. Trying on evening gowns I know I’ll never buy at stores. Korean dramas. Fandom merch. Beluga whales. Anytime the weather does anything interesting because my born-and-raised Southern Californian brain gets tired of 75 and sunny. Driving fast, music blaring, on empty highways - the more lanes, the better. Finding a new song that I like (bc I’m so insanely picky about music that this rarely happens). Choreographing dances and skating programs. Novelty - being places that aren’t like home, doing things I would never usually do. Airports. wearing new clothes. Large friendly dogs. People I haven’t talked to in a while responding to my Snapchat stories. Pictures of whale sharks. Tropical flowers, especially plumeria. Being in classes. Scrapbooking. Being onstage. Birthdays. Being nostalgic. Managing to write song lyrics that don’t suck. Christmas decorations. Rays (the ocean kind) - bat rays, manta rays, eagle rays, cownose rays, they’re all Babies and I love ‘em all. Foreign films that make you cry. Sandwiches! Museums. School dances. The idea, feeling, and experience of being a teenager in love. Textbooks. Movie trailers. Every single one of my OTPs. So many things.

Katara (most important person): um...most likely my mom. She’s been such a huge moral influence that it’s virtually impossible for any area of my life to *not* have been touched by my relationship with her. I love her a lot but we also challenge each other. Constantly. But that leads to growth? Right?

Yue (dreams): that’s hard, ugh...I feel like all of my biggest dreams are really selfish, and it’s kind of hard to admit that. But if I’m being completely honest, I have two:

1. to experience a moment of clarity in which something happens that is so good and so triumphant and so clearly right that my view of life shifts to make sense of it and I realize why things that once disappointed me had to fall into place the way they had to bring me to this moment, and

2. to have a best friend. You know, the kind that knows you better than yourself and helps you grow and goes on crazy adventures with you and never makes you doubt whether you mean as much to them as they do to you. Someone who feels like home. Maybe even a whole group of them. I’ve wanted that since I was old enough to make friends, and I don’t know if it’ll ever happen, but guys, I YEARN. Friendship is hard for me, and I know I should say my dream is to help bring about world peace or something, but...it’s really just this. Having people I can trust to take care of my heart.

0 notes

Text

List of animals I very much would like to hold or pet (non-comprehensive):

Goat

Sheep

Pigeon

Cow

Large Reptile (any)

Sea Hare (California Black or otherwise)

Giant land snail

Chicken

Your pet rat

Your pet mouse

Tarantula

Kid (goat)

Baby pig

Cicada (he scream)

Ray (sting, cownose, or otherwise)

Large slugs

Bee (fuzzy sorts only)

Whip spider (long whips!)

Armadillo

Large cockroach

Toe beans (any)

Opossum

Otter

Ferret, weasel, stoat, similar

Jackel, djole, coyote, simlar

Rabbit

Dogs (especially: extremely large or small; greyhound; hyper-fluff)

Do not want to hold or pet (non-comprehensive):

Bird larger than a chicken, especially with kicking legs

Llama

Alpca

Parrot larger than cockatiel (bite!)

HORSE

kangaroo

Sloth (claws and sharp! They're sneaky!)

Deer and larger

Dolphin (seems untrustworthy)

Whale (any)

Large cricket or weta (bite?)

Millipede (very bite!)

Centipede (seems untrustworthy)

Monkey or similar (seems untrustworthy)

Hyena

Mole rat (naked or otherwise - very bite!)

Beetle larvae (bite?)

Just any mammal more than 20% larger than me

Badger

Bear

Kid (human)

Mole (very soft! But do a bite)

Rainbow Lorikeet (BAD TONGUE)

Moth or butterfly (don't want to hurt them!)

Turtle (seems untrustworthy)

0 notes

Text

Get To Know Me Meme Tagged by @thesickficsideblog I choose: @feverfetish , @nerdlycharming @churningtummy , @feelingsick , @smolsickficwriter , @emetoandotherthings , @sickficprompts , @poorsickies , @sick-bae , @sitruksista

Name: G. Obviously I have more name, but this is what people call me.

Nickname: None, except for G. Although occasionally people call me Awkward. And my family calls me Pete.

Gender: Cis-Female

Star Sign: Aquarius

Height: 5′ 2". Almost exactly. At night anyhow. In the morning I’m about 5’ 2.75". Yes, I’ve measured.

Hogwarts House: Slytherin forever!!

Favorite Color: I do like black, but also deep blues, and also Fire colors. And also purples, especially lilac? But also teals and turquoises but also the colors of the forest?? But also—-

Favorite Animal: I’m so about all animals it’s not even funny. Cats are fantastic but I also really like dogs. I own a snake and love all reptiles, but I also love amphibians, especially salamanders they’re so cute. I love bugs too, except for mosquitoes and shit. They can fuck right off. Mantis shrimp are awesome, and also sting rays, especially spotted eagle rays and cownose rays. Also sharks, tho??? And I fuckin love octopi and cuttlefish!!!

Avg. Hours of Sleep: It constantly fluctuates between none and like 14. So I guess the average is technically around like 5 because I get less more often than more, but also go for days on end without sleeping, to the point of hallucinating a lil bit sometimes. Insomnia is a bitch.

Cats or Dogs: Cats!! I’m such a cat person it’s kinda crazy. But I also REALLY love dogs. But I don’t stop there. I love my reptiles too and I’m just an animal person, really. Favorite Fictional Characters: This isn’t a fair question. I have far FAR too many.

Favorite Singer/Band: I don’t have many specific ones right now. I listen to a lot of Broadway, though. How to Succeed, Beauty and the Beast, Mary Poppins, Little Mermaid, Wicked, Matilda, Hamilton, Footloose, and others. I also listen to a lot of jazz and classical, particularly Frank Sinatra, Bobby Darin, Dean Martin, Louis Armstrong, but also Chopin, Beethoven, Holst, Mahler, Schumann, Rachmaninoff, Stravinsky, Bartok, Tchaikovsky….

Dream Trip: Well I’m actually currently planning a road trip with my friends all around the states. But also I’d love to go Germany. I’m probably going to intern at a Biomedical Engineering lab in Stuttgart at some point in the next two years or so. But I’d also be down with taking a few close friends to a little wooded area I know about an hour south of my home and just go camping there for a week or so. Did that last year; its honestly one of my fondest memories.

Dream Job: Cardiothoracic surgeon with the background in engineering that allows me to research and develop new artificial hearts and such.

When was the blog made?: A few years back, in the winter I think.

Follower Count: 450 or so I think???

What made you make this blog? I found a community that shared my interests and didn’t judge me for having them. So I wanted to be a part of it. And now I am!! Love you all!!!

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Callinectes sapidus

Callinectes sapidus

Blue Crab escaping from the net at Core Banks, North Carolina. Callinectes sapidus (from the Greek calli- = "beautiful", nectes = "swimmer", and Latin sapidus = "savory"), the blue crab, Atlantic blue crab, or regionally as the Chesapeake blue crab, is a species of crab native to the waters of the western Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico, and introduced internationally. C. sapidus is of significant culinary and economic importance in the United States, particularly in Louisiana, the Chesapeake Bay, and New Jersey. It is the Maryland state crustacean and is the state's largest commercial fishery. Description Sexual dimorphism Females have a broad abdomen, similar to the shape of the dome of the United States Capitol building. Males have a narrow abdomen, resembling the Washington Monument. Callinectes sapidus is a decapod crab of the swimming crab family Portunidae. The genus Callinectes is distinguished from other portunid crabs by the lack of an internal spine on the carpus (the middle segment of the claw), as well as by the T-shape of the male abdomen. Blue crabs may grow to a carapace width of 23 cm (9.1 in). C. sapidus individuals exhibit sexual dimorphism. Males and females are easily distinguished by the shape of the abdomen (known as the "apron") and by color differences in the chelipeds, or claws. The abdomen is long and slender in males, but wide and rounded in mature females. A popular mnemonic is that the male's apron is shaped like the Washington Monument, while the mature female's resembles the dome of the United States Capitol. Claw color differences are more subtle than apron shape. The immovable, fixed finger of the claws in males is blue with red tips, while females have orange coloration with purple tips. A female's abdomen changes as it matures: an immature female has a triangular-shaped abdomen, whereas a mature female's is rounded. Other species of Callinectes may be easily confused with C. sapidus because of overlapping ranges and similar morphology. One species is the lesser blue crab (C. similis). It is found further offshore than the common blue crab, and has a smoother granulated carapace. Males of the lesser blue crab also have mottled white coloration on the swimming legs, and females have areas of violet coloration on the internal surfaces of the claws. C. sapidus can be distinguished from another related species found within its range, C. ornatus, by number of frontal teeth on the carapace. C. sapidus has four, while C. ornatus has six. The crab's blue hue stems from a number of pigments in the shell, including alpha-crustacyanin, which interacts with a red pigment, astaxanthin, to form a greenish-blue coloration. When the crab is cooked, the alpha-crustacyanin breaks down, leaving only the astaxanthin, which turns the crab to a red-orange or a hot pink color. Distribution Callinectes sapidus is native to the western edge of the Atlantic Ocean from Cape Cod to Argentina and around the entire coast of the Gulf of Mexico. It has recently been reported north of Cape Cod in the Gulf of Maine, potentially representing a range expansion due to climate change. It has been introduced (via ballast water) to Japanese and European waters, and has been observed in the Baltic, North, Mediterranean and Black Seas. The first record from European waters was made in 1901 at Rochefort, France. In some parts of its introduced range, C. sapidus has become the subject of crab fishery, including in Greece, where the local population may be decreasing as a result of overfishing. Ecology The natural predators of C. sapidus include eels, drum, striped bass, spot, trout, some sharks, humans, cownose rays, and whiptail stingrays. C. sapidus is an omnivore, eating both plants and animals. C. sapidus typically consumes thin-shelled bivalves, annelids, small fish, plants and nearly any other item it can find, including carrion, other C. sapidus individuals, and animal waste. C. sapidus may be able to control populations of the invasive green crab, Carcinus maenas; numbers of the two species are negatively correlated, and C. maenas is not found in the Chesapeake Bay, where C. sapidus is most frequent. Callinectes sapidus is subject to a number of diseases and parasites. They include a number of viruses, bacteria, microsporidians, ciliates, and others. The nemertean worm Carcinonemertes carcinophila commonly parasitizes C. sapidus, especially females and older crabs, although it has little adverse effect on the crab. A trematode that parasitizes C. sapidus is itself targeted by the hyperparasite Urosporidium crescens. The most harmful parasites may be the microsporidian Ameson michaelis, the amoeba Paramoeba perniciosa and the dinoflagellate Hematodinium perezi, which causes "bitter crab disease". Life cycle Eggs of C. sapidus hatch in high salinity waters of inlets, coastal waters, and mouths of rivers and are carried to the ocean by ebb tides. During seven planktonic (zoeal) stages blue crab larvae float near the surface and feed on microorganisms they encounter. After the eighth zoeal stage, larvae molt into megalopae. This larval form has small claws called chelipeds for grasping prey items. Megalopae selectively migrate upward in the water column as tides travel landward toward estuaries. Eventually blue crabs arrive in brackish water, where they spend the majority of their life. Chemical cues in estuarine water prompt metamorphosis to the juvenile phase, after which blue crabs appear similar to the adult form. Blue crabs grow by shedding their exoskeleton, or molting, to expose a new, larger exoskeleton. After it hardens, the new shell fills with body tissue. Shell hardening occurs most quickly in low salinity water where high osmotic pressure allows the shell to become rigid soon after molting. Molting reflects only incremental growth, making age estimation difficult. For blue crabs, the number of molts in a lifetime is fixed at approximately 25. Females typically exhibit 18 molts after the larval stages, while postlarval males molt about 20 times. Male blue crabs tend to grow broader and have more accentuated lateral spines than females. Growth and molting are profoundly influenced by temperature and food availability. Higher temperatures and greater food resources decrease the period of time between molts as well as the change in size during molts (molt increment). Salinity and disease also have subtle impacts on molting and growth rate. Molting occurs more rapidly in low salinity environments. The high osmotic pressure gradient causes water to quickly diffuse into a soft, recently molted blue crab's shell, allowing it to harden more quickly. The effects of diseases and parasites on growth and molting are less well understood, but in many cases have been observed to reduce growth between molts. For example, mature female blue crabs infected with the parasitic rhizocephalan barnacle Loxothylacus texanus appear extremely stunted in growth when compared to uninfected mature females. Blue crab may reach maturity within one year of hatching in the Gulf of Mexico, while Chesapeake Bay crabs may take up to 18 months to mature. As a result of different growth rates, commercial and recreational crabbing occur year-round in the Gulf of Mexico, while crabbing seasons are closed for colder parts of the year in northern states. Female blue crab with eggs Mating and spawning are distinct events in blue crab reproduction. Males may mate several times and undergo no major changes in morphology during the process. Female blue crabs mate only once in their lifetimes during their pubertal, or terminal, molt. During this transition, the abdomen changes from a triangular to a semicircular shape. Mating in blue crab is a complex process that requires precise timing of mating at the time of the female's terminal molt. It generally occurs during the warmest months of the year. Prepubertal females migrate to the upper reaches of estuaries where males typically reside as adults. To ensure that a male can mate, he will actively seek a receptive female and guard her for up to 7 days until she molts, at which time insemination occurs. Crabs compete with other individuals before, during, and after insemination, so mate guarding is very important for reproductive success. After mating, a male must continue to guard the female until her shell has hardened. Inseminated females retain spermatophores for up to one year, which they use for multiple spawnings in high salinity water. During spawning, a female extrudes fertilized eggs onto her swimmerets and carries them in a large egg mass, or sponge, while they develop. Females migrate to the mouth of the estuary to release the larvae, the timing of which is believed to be influenced by light, tide, and lunar cycles. Blue crabs have high fecundity: females may produce up to 2 million eggs per brood. Migration and reproduction patterns differ between crab populations along the East Coast and the Gulf of Mexico. A distinct and large scale migration occurs in Chesapeake Bay, where C. sapidus undergoes a seasonal migration of up to several hundred miles. In the middle and upper parts of the bay, mating peaks in mid to late summer, while in the lower bay there are peaks in mating activity during spring and late summer through early fall. Changes in salinity and temperature may impact time of mating because both factors are important during the molting process. After mating, the female crab travels to the southern portion of the Chesapeake, using ebb tides to migrate from areas of low salinity to areas of high salinity, fertilizing her eggs with sperm stored during her single mating months or almost a year before. Spawning events in the Gulf of Mexico are less pronounced than in estuaries along the East Coast, like the Chesapeake. In northern waters of the Gulf of Mexico, spawning occurs in the spring, summer, and fall, and females generally spawn twice. During spawning, females migrate to high salinity waters to develop a sponge, and return inland after hatching their larvae. They develop their second sponge inland, and again migrate to the higher-salinity waters to hatch the second sponge. After this, they typically do not reenter the estuary. Blue crabs along the southernmost coast of Texas may spawn year-round. Commercial importance Cooked blue crabs Cooked blue crabs, shown here on sale at a fish market in Washington, D.C., are red. Commercial fisheries for C. sapidus exist along much of the Atlantic coast of the United States, and in the Gulf of Mexico. Although the fishery has been historically centered on the Chesapeake Bay, contributions from other localities are increasing in importance. In the past two decades, the majority of commercial crabs have been landed in four states: Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, and Louisiana. Weight and value of harvests since 2000 are listed below. Fishery value in millions of dollars (and percentage of national harvest weight) Year Maryland Virginia North Carolina Louisiana National 2000 31 (12.3) 24 (15.5) 37 (21.8) 34 (28.0) 164 2001 35 (16.3) 26 (15.8) 32 (20.2) 32 (26.3) 158 2002 30 (15.1) 21 (15.5) 33 (21.5) 31 (28.5) 147 2003 35 (16.3) 19 (12.6) 37 (25.0) 34 (28.1) 154 2004 39 (19.4) 22 (15.8) 24 (19.6) 30 (25.4) 146 2005 40 (21.9) 21 (16.4) 20 (16.0) 27 (23.9) 141 2006 31 (17.7) 14 (13.7) 17 (15.3) 33 (32.1) 126 2007 42 (19.6) 16 (16.0) 21 (13.6) 35 (28.7) 149 2008 50 (21.5) 18 (14.3) 28 (20.3) 32 (25.7) 161 2009 52 (22.0) 21 (18.6) 27 (16.8) 37 (30.1) 163 2010 79 (33.2) 29 (19.3) 26 (15.4) 30 (15.4) 205 2011 60 (25.3) 26 (19.6) 21 (14.9) 37 (21.7) 184 2012 60 (24.4) 25 (18.5) 23 (14.9) 39 (22.8) 188 2013 50 (17.9) 24 (18.0) 30 (16.5) 51 (28.8) 192 As early as the 1600s, the blue crab was an important food item for Native Americans and European settlers in the Chesapeake Bay area. Soft and hard blue crabs were not as valuable as fish but gained regional popularity by the 1700s. Throughout their range crabs were also an effective bait type for hook and line fisheries. Rapid perishing limited the distribution and hindered the growth of the fishery. Advances in refrigeration techniques in the late 1800s and early 1900s increased demand for blue crab nationwide. The early blue crab fishery along the Atlantic coast was casual and productive because blue crabs were extremely abundant. In the lower Chesapeake Bay, crabs were even considered a nuisance species because they frequently clogged the nets of seine fishermen. Early on, the blue crab fishery of the Atlantic states was well documented. Atlantic states were the first to regulate the fishery, particularly the Chesapeake states. For example, after observing a slight decline in harvest, the fishing commissions of Virginia and Maryland put size limits into place by 1912 and 1917 respectively. Catch-per-unit-effort at the time was determined by packing houses, or crab processing plants. The early history of the recreational blue crab fishery in the Gulf of Mexico is not well known. Commercial crabbing was first reported in the Gulf of Mexico in the 1880s. Early crab fishermen used long-handled dip nets and drop nets among other simple fishing gear types to trap crabs at night. Blue crab spoiled quickly, which limited distribution and hindered the growth of the fishery for several decades. The first commercial processing plant in Louisiana opened in Morgan City in 1924. Other plants opened soon after, although commercial processing of hard blue crabs was not widespread until World War II. Louisiana now has the world's largest blue crab fishery. Commercial harvests in the state account for over half of all landings in the Gulf of Mexico. The industry was not commercialized for interstate commerce until the 1990s, when supply markedly decreased in Maryland due to problems (see above) in Chesapeake Bay. Since then, Louisiana has steadily increased its harvest. In 2002, Louisiana harvested 22% of the nation's blue crab. That number rose to 26% by 2009 and 28% by 2012. The vast majority of Louisiana crabs are shipped to Maryland, where they are sold as "Chesapeake" or "Maryland" crab. Louisiana's harvest remained high in 2013, with 17,597 metric tons of blue crab valued at $51 million. In addition to commercial harvesting, recreational crabbing is very popular along Louisiana's coast. The Chesapeake Bay has had the largest blue crab harvest for more than a century. Maryland and Virginia are usually the top two Atlantic coast states in annual landings, followed by North Carolina. In 2013, crab landings were valued at $18.7 million from Maryland waters and $16.1 million from Virginia waters. Although crab populations are currently declining, blue crab fishing in Maryland and Virginia remains a livelihood for thousands of coastal residents. As of 2001, Maryland and Virginia collectively had 4,816 commercial crab license holders. Three separate licenses are required for each of the three major jurisdictional areas: Maryland, the Potomac River, and Virginia waters. While the Bay’s commercial sector lands the majority of hard crab landings and nearly all peeler or soft crab landings, the recreational fishery is also significant. In 2013, an estimated 3.9 million pounds of blue crab were harvested recreationally. Blue crab populations naturally fluctuate with annual changes in environmental conditions. They have been described as having a long-term dynamic equilibrium, which was first noted after irregular landings data in the Chesapeake in 1950. This tendency may have made it difficult for managers to predict the severe decline of the Chesapeake’s blue crab populations. Once considered an overwhelmingly abundant annoyance, the declining blue crab population is now the subject of anxiety among fishermen and managers. Over the decade between the mid-1990s to 2004, the population fell from 900 million to around 300 million, and harvest weight fell from 52,000 tons (115,000,000 lbs) to 28,000 tons (62,000,000 lbs). Revenue fell further, from $72 million to $61 million. Long term estimates say that the overall Chesapeake population decreased approximately 70% in the last few decades. Even more alarming, the number of females capable of reproducing, known as spawning age females, has plummeted 84% in the just a few decades. Survival and addition of juveniles to the harvestable crab population is also low. Many factors are to blame for low blue crab numbers, including high fishing pressure, environmental degradation, and disease prevalence. Many types of gear have been used to catch blue crabs along the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts. Initially people used very simple techniques and gear, which included hand lines, dip nets, and push nets among a variety of other gear types. The trotline, a long baited twine set in waters 5–15 feet deep, was the first major gear type used commercially to target hard crabs. Use of commercial trotlines is now mostly limited to the tributaries of the Chesapeake Bay. In the Gulf of Mexico, trotline use drastically declined after invention of the crab pot in 1938. Crab pots are rigid boxlike traps made of hexagonal or square wire mesh. They possess between two and four funnels that extend into the trap, with the smaller end of the funnel inside of the trap. A central compartment made of smaller wire mesh holds bait. Crabs attracted by odorant plumes from the bait, often an oily fish, enter the trap through the funnels and cannot escape. Species other than blue crab are often caught incidentally in crab pots, including fish, turtles, conch, and other crab species. Of important concern is the diamondback terrapin, Malaclemys terrapin. The blue crab and diamondback terrapin have overlapping ranges along the East and Gulf coasts of the United States. Because the funnels in a crab pot are flexible, small terrapins may easily enter and become entrapped. Traps are checked every 24 hours or less, frequently resulting in drowning and death of terrapins. Crab pot bycatch may reduce local terrapin populations to less than half. To reduce terrapin entrapment, bycatch reduction devices (BRDs) may be installed on each of the funnels in a crab pot. BRDs effectively reduce bycatch (and subsequently mortality) of small terrapins without affecting blue crab catch. Because of its commercial and environmental value, C. sapidus is the subject of management plans over much of its range. In 2012, the C. sapidus population in Louisiana was recognized as a certified sustainable fishery by the Marine Stewardship Council. It was the first and remains the only certified sustainable blue crab fishery worldwide. For the state to maintain its certification, it must undergo annual monitoring and conduct a full re-evaluation five years after the certification date. source - Wikipedia Dear friends, if you liked our post, please do not forget to share and comment like this. If you want to share your information with us, please send us your post with your name and photo at [email protected]. We will publish your post with your name and photo. thanks for joining us www.rbbox.in

from Blogger https://ift.tt/2N4A9Uu

0 notes

Text

Wildlife Weekly Wrap-Up: 03/17.17

Your weekly roundup of wildlife news from across the country.

Don’t miss your shot to be featured! Defenders’ 9th annual photo contest ends on Monday March 24th! You can submit six images into the different categories. Don’t forget to check out the list of 25 key species and 15 focal landscapes that we are especially interested in!

Learn more about the photo contest and see who won last year >>>

LWCF funding affected by new budget. Despite bi-partisan legislation introduced by Senator Burr (R, NC) and Senator Cantwell (D, WA) last week, the Land and Water Conservation Fund could lose 70% of its funding as part of the newly proposed budget.

Read more about the importance of LWCF >>>

A wildlife shop of horrors? USFWS has a property repository of confiscated items that included shipments full of illegal wildlife products, like a taxidermic Hawksbill Sea Turtle which is an endangered species.

Find out more about illegal wildlife products seized entering the US >>>

The National Wildlife Refuge System turned 114! On March 14th, the National Wildlife Refuge System celebrated one hundred and fourteen years. Today it spans 850 million acres, including seven marine national monuments, 566 national wildlife refuges, and 38 wetlands management districts.

Check out some amazing images celebrating this milestone >>>

Great news for Cownose Ray! Thanks to our coalition efforts, the MD cownose ray bill passed the House of Delegates this afternoon 119-21!

Read more about this important state legislation >>>

The post Wildlife Weekly Wrap-Up: 03/17.17 appeared first on Defenders of Wildlife Blog.

from Defenders of Wildlife Blog http://ift.tt/2n710p7 via IFTTT

0 notes