#englishchannel

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

instagram

Mihir Sen, a renowned Indian swimmer and lawyer, was the first Asian to swim the English Channel in 1958, setting a record time for the journey from Dover to Calais.

#mihir#swimming#panamacanal#englishchannel#reels#globalsports#athlete#sports#swim#swimwear#lawyer#oldtimes#Instagram

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

unmoored

Voyaging belongs to seamen, and to the wanderers of the world who cannot, or will not, fit in. If you are contemplating a voyage and you have the means, abandon the venture until your fortunes change. Only then will you know what the sea is all about.

Sterling Hayden, from Wanderer (1963)

I sense the weather as I wake, even before I open my eyes.

The hull is still, save for a faint, gravitational shift of tension starboard, between it and the wooden pontoon to which it’s tethered. A shift of tide, not wind. The only sound is my wife’s breathing as she sleeps.

The air in the cabin is cold for a summer morning. The moisture in it has substance; you can almost swill it around your mouth. There’s a thin taste of salt, diesel and wood.

Fog.

I open my eyes to peer through a perspex hatch above my head. Sky the colour of stale milk has fallen across it. I sit up, wrap my duvet around my shoulders, and check the small, brass-encased barometer and clock on the bulkhead above the foot of my bunk. 6.30am: four hours before high water.

In an hour, my wife and I will warp our old sloop from its berth and sail a mile or so north-west across the Tamar estuary on the flood to thread a narrow channel edged by mudflats, at the mouth of a nearby tributary, St. John’s River, to reach a ramshackle boatyard where our boat is to be lifted ashore for repairs.

Fog and unfamiliar waters will make what might have been a careless twenty-minute transit more testing. Up-river are commercial wharves and a naval dockyard. Large ships and ferries ply the buoyed, deep-water fairway in the middle of the river, heedless of small boats like ours — mere pin-pricks, if seen at all, on their radar screens. In such poor visibility, the percussive thud thud of heavy diesels will be the only hint we get of their proximity and course.

Our boat has no radar. No GPS either. The VHF radio has seen better days. Wrack is an impoverished vessel, sea-worn and ill-equipped, almost half a century old, but capable enough under sail. With a fair breeze today, we can make do with a salt-stiffened mainsail, steering compass, and a rough plan of soundings with a small section of shoreline that I’ve traced in pencil from a large-scale chart on the harbourmaster’s office wall.

We moved aboard four months ago, at the beginning of what turned out to be a cold, wet spring. The boat was berthed on a listing pontoon, on the lower reaches of another river, the Itchen, 150 sea miles east of where we are now, alongside a bank of coal black mud that dried at low water and smelled of rotting seaweed and industrial waste. The capricious eddies of a semidiurnal ebb and flow tugged at the keel. Mooring lines creaked as they strained against their cleats.

It took a while to get used to the constant movement of the boat and the noises the river — and the relentless equinoctial wind — drew from its hull and rigging, but they were the least of other things we had to get used to: cooking in a tiny galley, pumping waste from the toilet by hand, even moving back and forth in the narrow cabin or outside, along rope-strewn decks. I had spent my youth living and working on the water but that was nearly half a century ago; my wife had grown up in the rural north of Oklahoma, far from any sea. I’m not sure what we expected but our first month aboard was an unsettling hardship. The cabin was gelid and condensation dripped from the deckhead, portlights and hatches. Brown water puddled at the bottom of every shelf and locker. Mildew and mould were everywhere.

Yet the boat was a refuge. We had wandered in search of somewhere to settle — or, more precisely, somewhere we would be allowed to settle — for four years, moving between whatever cheap, temporary accommodation we could borrow or afford to rent in seven countries, until this unkempt but graceful vessel suggested a possibility of shelter, of ‘fixedness’, even as we were compelled by circumstances to remain mobile, unrooted. We saw it — no, not her — as a floating vardo, spartan but functional, and by the time we slipped our lines from the pontoon and headed downriver, with a spring ebb hurrying us towards the open sea, where we would turn westwards, still uncertain of a precise destination, we had accepted the idea of ourselves as waterborne Gypsies, seafarers not yachtsmen, finally cut adrift from a shore that, we felt, no longer had a place for us.

We reach the edge of the ship channel as the sun rises above the low hills inland. A light northerly and the press of a strong spring flood againt the leeward bow fills the mainsail just enough for a slight wake to trail aft from the transom. By the time we’re reach the other side of the estuary, the fog has begun to dissipate but we’re still taken by surprise when a pair of large tugs, steaming seawards in company, materialises suddenly, as if out of thin air, and crosses our track close astern.

My wife and I stand together in the cockpit and peer forward under the boom, hoping to spot small, plastic, red and green buoys that will guide our course towards the boatyard. I study my hand-wrought chart and try to make it fit with the few features we can see: a pub, a car park, jittery water over shoals that fringe the low-lying shore.

Within a few minutes, we are picking our way across those same shoals. My wife calls out readings from an electronic depth-sounder, none of them reassuring. Our keel is close enough to the river bottom that I can feel a swirl of turbulence around it through the rudder. Two hundred metres off the port bow, through haze, I make out the rusted steel hulks of two river freighters, aground on the mud; they suggest a makeshift breakwater. Several metres to starboard, another improvised breakwater: the large, weather-worn wreck of a wooden fishing boat, its seams swollen and seeping rust, also aground and listing precariously against a high concrete quay. I assume the entrance is somewhere in between. My chart, such as it is, ends at these motley barriers.

We douse our sails and start the engine; with the throttle in neutral, we let the tide carry us closer over the murky shallows. There’s a volley of small arms fire. Then an explosion.

“I’ve seen this movie,” my wife says.

When I was a boy I dreamed of pirate utopias.

They were everywhere in the 17th and 18th centuries, refuges for outlaws and dissolute outsiders. From the island of Madagascar, the renegade captains Henry Every and William Kidd preyed on Arab traders and ships of the East India Companies off the coasts of East Africa and southern India; there were corsair strongholds in the Mediterranean — Ghar al Milh in Tunisia and Algiers — and the Muslim pirate Republic of Salé on the Atlantic coast of Morocco; there were a score of well-known Caribbean refuges, among them Port Royal, a British buccaneer sanctuary on the Jamaican coast, Tortuga on the French-held island of Haiti, and New Providence in the Bahamas, the last an uninhabited island until it was claimed by an English privateer-turned-pirate Henry Jennings and became the hideout of a pirate admiral, Benjamin Hornigold, and later the infamous ‘Blackbeard’, Edward Teach.

These were rough, anarchic places, their shores often defended by ramparts arrayed with cannons, behind which lay improvised settlements of victuallers, armourers, shipwrights, canvasmakers, boarding houses, bars, brothels, illicit traders, ‘fences’, and slavers, all in service to the pirate fleet and its crews. During fair weather seasons, the anchorages would swell to become water-bound townships themselves, with ships of all sizes, many of the captured ‘prizes’, lying in close proximity to each other, a steady traffic of oared lighters and cutters navigating the narrow waters between them.

I was forty-two years old when I came across a copy of Peter Lamborn Wilson’s 1995 book, Pirate Utopias: Moorish Corsairs and European Renegadoes, which connected, obliquely, Wilson’s somewhat idealised take on these unruly havens to his by-then-notorious notion of Temporary Autonomous Zones. First published in 1991 under the pseudonym Hakim Bey, just two years after Timothy Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web, Lamborn’s book, T.A.Z.: The Temporary Autonomous Zone, described a “socio-political tactic of creating temporary spaces that elude formal structures of control”. It also suggested real and virtual ‘territory’ within which anarchic concepts of unrestricted freedom, beyond the reach of government, might be explored. Similar ideas, sparsely defined, in relation to sea-borne communities, had inspired me as a young man, when I first slipped away from a privileged, if peripatetic, upbringing to live alone aboard a tiny sailing boat.

If my younger self had been pressed to describe what a 21st century ‘pirate utopia’ might look like, he might have come up with the ramshackle, almost dystopian seascape that we are entering, tentatively, on a sluggish flood.

Astern of the rotting wooden trawler on the starboard edge of the entrance, a small, former naval ship of some sort with high freeboard lists against the quay, thin water barely covering its propellors, while to port, a row of aged, fibreglass sailboats are berthed along a rickety pontoon secured to the corroded river freighters-turned-breakwaters; the sailboats’ keels are sunk in a glutinous shoal that, we later find out, is submerged just twice a day, for two hours either side of high water. As we drift deeper within, we pass iron-hulled narrowboats in various states of disrepair, rafted together, but disconcertingly out of place on these tidal flats, far from any canal — two young women in long floral dresses atop one of them, sipping from colorful mugs, which they raise to greet us.

Every boat looks lived in, every deck strewn with jerry cans, pot plants, and mildewed canvaswork, coachtops and rigging draped with laundry and improvised awnings. The effect is of a shanty town, a floating favela thrown together by the vagaries of wind and tide, as if the disparate vessels were caught by the tendrils of a slow-moving gyre that eventually stranded them here, in this shallow rural backwater.

A once graceful, large motor-launch, its wooden superstructure gone to seed and patched with random off-cuts of marine ply and sheets of clear plastic, marks the end of the entrance channel. We turn ninety degrees to port into a rectangular pool of oily, brown water enclosed by cement quays and wooden pontoons. Arrayed along the quays, a handful of buildings, some more permanent than others, in stone, timber, and corrugated metal.

We steer towards a slipway; at the bottom of it, lapped by the rising tide, is a insect-like steel structure, a U-shaped gantry on wheels, from which are suspended a set of canvas slings. Men are perched atop the steel beams above the slings which, as we approach, are lowered and the whole structure moves further down the ramp, into the water. We kill the engine; there is just enough way on to drift the boat into its skeletal maw. The slings are raised, slowly, either side of the keel. The hull ceases to respond to the movement of the water. The deck becomes solid underfoot. Then, like some arcane Victorian mechanical stage effect, the boat begins to rise from the sea into the air.

More volleys of gunfire and the muffled thud of an explosion. A whisp of pale smoke rises above a line of trees on the other side of the harbour. Someone shouts a series of indistinct instructions.

“Bloody commandos,” a young woman says. She stands at a counter at one end of a somewhat chaotic kitchen in a small, open plan shed that serves as the harbour’s canteen.

“Training,” says an old man with arthritic hands and rheumy eyes, sitting alone at one of the few tables. Ex-military himself, the small sailboat he has lived aboard, alone, for six years is berthed just a hundred yards from the grassy foreshore that is the staging ground for a series of practice assaults by armed soldiers aboard rubber boats. He has retreated to the café to get away from the noise and for company.

There are three other customers, besides the old man, my wife and me. One is a former marine in his fifties who was discharged with post-traumatic stress and found insulation from his past and a necessary solitude aboard a different boats over the past decade. The others are a gangly, middle-aged South African guy who does freelance maintenance and refitting for the local yard, and a transexual English shipwright with Barbie-esque hips and bust but large, gnarled hands and a waterman’s weathern-worn face. All live aboard boats here and like the old man, come to the café as much for random social encounters as for food.

Everyone converses with each other easily: there is commonality in our lives afloat. But there is also the impression that we are all untethered and adrift. The lack of individual fixedness (that word, again) is stark. We talk of boats, sea passages and ports of call but there is no sense of place, of belonging. None of us have a home in our heads to return to — maybe this last defines the elemental difference between recreational sailors and sea-dwellers, between the guests of high-priced marinas and the liveaboard outsiders moored here and elsewhere in the obscure reaches of other estuaries and tidal creeks around the British coast — but very few of us have been pressed into this circumstance. It is a choice, or sometimes a lawless inclination, driven only in part by a desire to feel free of some of the strictures and conventions of life ashore.

Disappearance is an art and those drawn to a life on the sea are adept at it. Community among seafarers is temporary and non-committal at best. Even here, among a fleet of decrepit boats that rarely put to sea, the comings and goings of individual liveaboards — some of whom crew other people’s boats for a living — are like hauntings. For all the 20th century theorizing about pirate utopias and temporary autonomous zones — the former focussed on the consensus and lack of hierarchy at the heart of piratical decision-making (and a lack of tolerance for autocratic captains) — and the history of rigid command structurea and iron discipline imposed over centuries on sailing ships’ crews at sea, most seafarers are now, as in the past, introspective proto-anarchists, resolutely solitary, who, when ashore, might be mistaken for ghosts.

At sunset, the quayside is empty. The boatyard’s tradesmen and office staff have retreated to their homes and whatever awaits them there. A few, dim lights can be glimpsed through portholes or perspex hatches but few people. The light winds in the estuary have dissipated and the air has begun to cool. The tide is at its lowest ebb — in the harbour, now empty of saltwater , the keel of every vessel has been swallowed by an expanse of grim sludge

Standing on a short jetty, my wife chats with a much younger woman who is taking in bed linen left to dry along the boom of a small, gaff-rigged, wooden sailboat.

“How long’re you around for?” she asks my wife.

“Until the boat’s done,” my wife says.

“And then?”

We both shrug, not knowing.

First published in Dark Ocean, an anthology from The Dark Mountain Project, UK, 2024.

#sea#memoir#nomadlife#livingaboard#seafaring#seanomads#seasteading#englishchannel#boatcommunity#england

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#Russia#CrimeaIsUkraine#Crimea#UkraineRussiaWar#Ukraine#France#EnglishChannel#migrants#hawaiifires#wildfires#Ecuador#Israel#Niger#Lebanon#ECOWAS#Youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

У меня тут недавно случился прилив вдохновения и теперь у меня есть свой ✨ТЕЛЕГРАМ КАНАЛ✨ Я поняла, что давно пора: я столько знаю, стольким могу поделиться и такому большому количеству людей могу помочь - что не смогла удержаться! На канале буду вещать о том, какого быть преподавателем английского, соответсвенно и про английский тоже буду писать. Ну и, конечно же, лайфстайл, куда без него оставлю здесь ссылку со скромный надеждой на то, что вы по ней перейдете даже, если вы со мной не останетесь, то сможете найти что-нибудь интересное или хотя бы поставить реакции на парочку постов🫶🏻 tg: @englishandmaria https://t.me/englishandmaria

#tg#englishchannel#telegram#life#live#girl#жизнь#мысли#books and libraries#quote#блог#blog#business#fashion#порусски#блог по русски

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Across the Channel - Prologue (on Wattpad) https://www.wattpad.com/1479456592-across-the-channel-prologue?utm_source=web&utm_medium=tumblr&utm_content=share_reading&wp_uname=France_thecountry A Couple, stuck beyond the English channel, One in the UK, One in France, War has broken out and they want to see each other again, but with the war, financial problems, and the fact that they aren't married causes controversy, and they are unable to see each other. Elise is stuck in Calais, France, and Samuel is stuck in London, England. The Nazi Germany has started to invade Belgium and parts of France, Making Elise stuck in Calais, without enough money to leave. Updated weekly: Wednesdays at 15:00 (3pm) EST

0 notes

Text

Six Die as Migrant Boat Capsizes in English Channel

Read more:👇

#MIGRANTBOAT#MIGRANT#CAPSIZES#ENGLISHCHANNEL#RISHISUNAK#MIGRATIONCRISIS#todayonglobenews#todayonglobe#tognews#tog#news#dailynews#dailynewsupdate#trendingnews#breakingnews#latestnews

0 notes

Text

#Breaking: The number of #migrants crossing the #EnglishChannel into the #UK in 2024 rose by 25%

The number of migrants crossing the English Channel into the United Kingdom in 2024 rose by 25% according to data released by the interior ministry. The year 2024 also marked the deadliest year for Channel crossings, with at least 76 recorded deaths. https://p.dw.com/p/4ok9r Source: X

0 notes

Photo

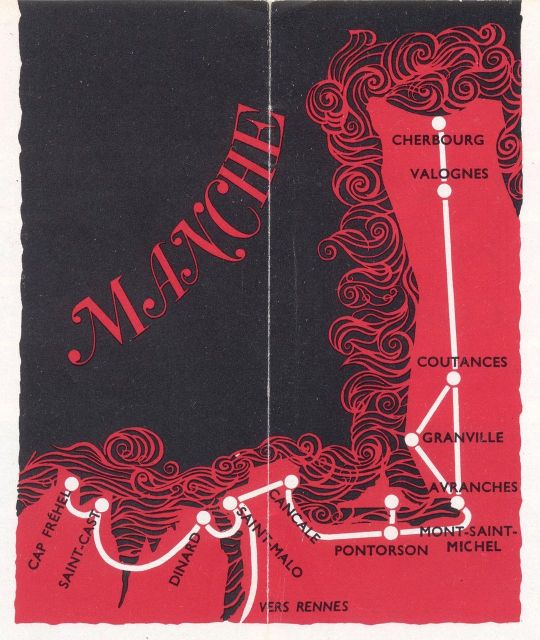

Groovy late-1960s waves going wavy on the shores of the Manche region of France in this snippit from a tourist guide foldout thingy (thanks @oliverwoodsphoto). T-r-è-s b-o-n! #tourism #france #manche #lamanche #retrodesign #typography #waves #sea #englishchannel #graphicdesign #illustration #map #vintagemap #cartography #tourist #1960s #60sdesign #1960sdesign https://www.instagram.com/p/CkY8n0aIhwF/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#tourism#france#manche#lamanche#retrodesign#typography#waves#sea#englishchannel#graphicdesign#illustration#map#vintagemap#cartography#tourist#1960s#60sdesign#1960sdesign

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lovely day on Wednesday. Great way to start the hoilday in Devon. Exploring the river dart from Dartmouth to Totnes. @dartmouth_steam_railway #dartmouth #boats #steamtrain #dayout #ferry #dartmouthcastle #history #memories #riverdart #englishchannel #fishingboats #roundrobin #hoilday #paingnton #weatherchanging #hot #trees #photography #devon (at River Dart) https://www.instagram.com/p/CgIC3UVspGT/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#dartmouth#boats#steamtrain#dayout#ferry#dartmouthcastle#history#memories#riverdart#englishchannel#fishingboats#roundrobin#hoilday#paingnton#weatherchanging#hot#trees#photography#devon

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Folkestone View (from Crete Road East) - swipe for on site photo. 31 July 2018. (12 x 16 ins). Painting available at £425 framed. #folkestoneview #creteroadeast #kent #shepway #dungenessview #englishchannel #parchedgrass #impressionism #oilpainting #painting #pleinair #pleinairpainting #britpleinair #allaprima #artlover #artistsoninstagram #contrejour (at Folkestone, Kent) https://www.instagram.com/p/CXJ6jlvobzy/?utm_medium=tumblr

#folkestoneview#creteroadeast#kent#shepway#dungenessview#englishchannel#parchedgrass#impressionism#oilpainting#painting#pleinair#pleinairpainting#britpleinair#allaprima#artlover#artistsoninstagram#contrejour

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rusted or splintered hulks and cement-filled pontoons form makeshift breakwaters for Carbeile Wharf, a tidal boatyard and Mad Max-adjacent live-aboard community in Torpoint, Cornwall, 2023

#community#estuary#marina#haven#liveaboard#cornwall#england#sea#sailors#boats#englishchannel#photography#travel

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

News emerged this afternoon that at least thirty people have drowned in the English Channel, during an attempt to cross it enabled by people traffickers. We may never know what their motivation and ambitions were, but those with faith will believe that they have gone to God, and those that have none will know that the fear, hunger and pain they may have suffered during their journey is ended. The news that four arrests have since been made in France will be of little comfort to their relatives, whose hopes may have been invested in the success of travellers who died so close to their final destination in the cold November seas. Had they made it to our coast some of them may have ended up in Greenford. Pedestrian walkway, Runnymede Gardens, A40, Greenford, London Borough of Ealing, London, UK, November 2021. #EnglishChannel #migration #night #sadness #thepassenger #A40 #Greenford #LondonBoroughofEaling #London #UK #November2021 #suburbs #suburban #suburbia #photography

#black#blue#grey#EnglishChannel#migration#night#sadness#thepassenger#A40#Greenford#LondonBoroughofEaling#London#UK#November2021#suburbs#suburban#suburbia#photography

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This is amazing, although I prefer to think it's Lir, but each to their own 🌬🌊/|\ #Repost @bbcnews・・・ This dramatic image was captured in the stormy seas of Newhaven Harbour in East Sussex, southern England. “Neptune seemed to make an appearance during this morning’s channel storm,” BBC photographer Jeff Overs said. His ‘sighting’ the face of Roman god of the water, Neptune seems to be an example of pareidolia. This is when people see a specific or meaningful image in an otherwise random or ambiguous visual pattern. Click the link in our bio to see other pictures from around the world. (📸@Oversnap) #pareodolia #poseidon #ocean #lir #storm #sea #seascape #neptune #mythology #englishchannel #newhaven #weather #gale #faces https://www.instagram.com/p/CREo5PtrWzl/?utm_medium=tumblr

#repost#pareodolia#poseidon#ocean#lir#storm#sea#seascape#neptune#mythology#englishchannel#newhaven#weather#gale#faces

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#BREAKING: 882 #migrants in 12 boats crossed the #EnglishChannel on Tuesday, the #HomeOffice has said

BREAKING: 882 migrants in 12 boats crossed the English Channel on Tuesday, the Home Office has said, which is the highest number of people on a single day so far this year Full story https://trib.al/EpEC1b4 Video: https://x.com/i/status/1803354811619791290 Source: X

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

OLD PORTSMOUTH • UK HAMPSHIRE Old Portsmouth is a district of the city of Portsmouth. It is the area covered by the original medieval town of Portsmouth as planned by Jean de Gisors. It is situated in the south west corner of Portsea Island. The area is also home to Portsmouth's small fishing fleet and fish market at Camber docks The very modern buildings are not considered in keeping with the historic surroundings. This was considered one of the factors in Portsmouth being ruled out of contention for the race to be the UK's next city of culture. #oldportsmouth #hotwalls #portsmouth #hampshire #uk #costalcity #port #heritage #history #urbanregeneration #adaptivereuse #beach #englishchannel #fishandchips #seafood #jeandegisors (at Old Portsmouth Hot Walls) https://www.instagram.com/p/CFtov2sjwvWneQigiSgeIjhpsi4z34QeXneT4M0/?igshid=1kw7l3sjb80qv

#oldportsmouth#hotwalls#portsmouth#hampshire#uk#costalcity#port#heritage#history#urbanregeneration#adaptivereuse#beach#englishchannel#fishandchips#seafood#jeandegisors

1 note

·

View note

Photo

#brighton #hove #palacepier #coast #seaside #englishcoast #beach #englishchannel #seafront #pier #travel #wanderlust #photosofbritain #unitedkingdom 🇬🇧 #summer (at Brighton Seafront) https://www.instagram.com/p/CEfNPrMJmqU/?igshid=3sxz913ml18j

#brighton#hove#palacepier#coast#seaside#englishcoast#beach#englishchannel#seafront#pier#travel#wanderlust#photosofbritain#unitedkingdom#summer

1 note

·

View note