#emperor Sakuramachi

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Royal Birthdays for today, February 8th:

Yaroslav II, Grand Prince of Vladimir, 1191

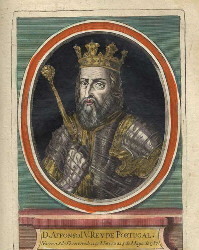

Afonso IV, King of Portugal, 1291

Constantine XI Palaiologos, Byzantine Emperor, 1405

Ulrich, Duke of Württemberg, 1487

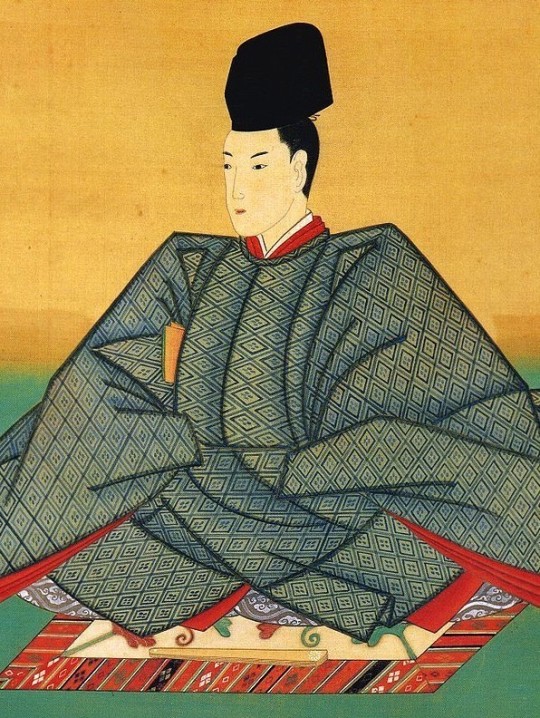

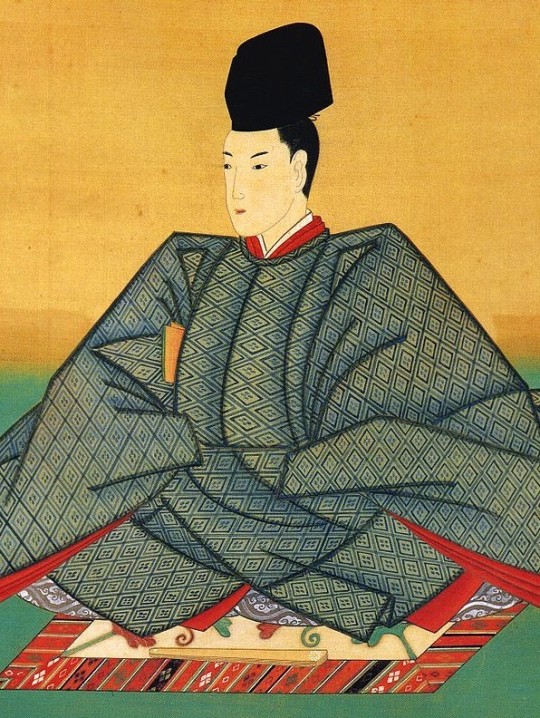

Sakuramachi, Emperor of Japan, 1720

Gia Long, Emperor of Vietnam, 1762

Caroline Augusta of Bavaria, Empress of Austria, 1792

Michael Pavlovich, Grand Duke of Russia, 1798

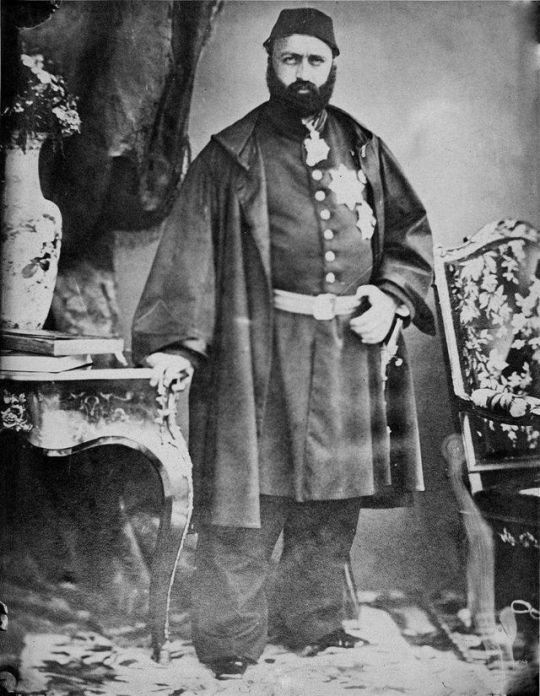

Abdülaziz, Ottoman Sultan, 1830

#Caroline Augusta of Bavaria#yaroslav ii#afonso iv#Constantine XI Palaiologos#duke ulrich#emperor Sakuramachi#emperor gia long#michael pavlovich#Abdülaziz#royal birthdays#long live the queue

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Empress Kōken-Shōtoku (718–770) has long been burdened by an undeserved negative reputation. Far from being a weak woman, she was in fact the last great empress regnant of Japan.

The Crown Princess

Her father was Emperor Shōmu, and her mother, Empress Consort Kōmyō, wielded significant influence. In 727, Kōmyō gave birth to a son, but he tragically died shortly after. In 738, Kōken, then known as Princess Abe, was declared crown princess—a historic first, as no woman before her had been officially named heir apparent, despite Japan’s history of female rulers.

Her early education was overseen by her mother, followed by a renowned scholar who taught her Chinese classics and statecraft. In 749, she ascended the throne after her father’s abdication.

Her First Reign

The Great Buddha Hall at Tōdaiji Temple was completed during her reign. Like her parents, she was a fervent supporter of Buddhism. As a patron of the arts and a sponsor of sutra distribution, she played a key role in establishing Buddhism as a cornerstone of Japanese culture for centuries.

However, Kōken also faced challenges, particularly the growing influence of the powerful Fujiwara clan, to which her mother belonged. After her father’s death in 756, he had designated a successor for Kōken, but the strong-willed empress chose her own candidate. She abdicated in 758 to focus on religious matters.

Machinations and Revolts

Kōken was thus free from the constraints of court ceremonies and quickly became a focal point for opposition to the Fujiwara clan. During this period, she formed a close relationship with the monk Dōkyō, who healed her during an illness in 761.

Legend claims that Kōken once lamented to her attendants that while a male emperor could take multiple consorts, she was expected to remain single. Whether true or not, she was likely aware of the societal constraints imposed on her.

Meanwhile, her successor, Emperor Junnin, sought to wage war against the Korean kingdom of Silla. Kōken opposed him, asserting that matters of such importance—war, rewards for merit, and punishment for wrongdoing—were decisions only she, as a former empress, was qualified to make.

Junnin’s chief minister, Fujiwara no Nakamaro, plotted a revolt against Kōken, but she acted swiftly. Her forces defeated Nakamaro in a decisive battle, leading to his capture and execution. Kōken then deposed Junnin, exiling him and reclaiming the throne in 764 as Empress Shōtoku. By this point, her authority was unchallenged.

Return to Power

During her second reign, Kōken-Shōtoku consolidated her power. She prohibited unauthorized land claims and banned officials from keeping private weapons. She also worked to integrate Buddhist and Shinto beliefs. Her reign saw Japan’s first examples of woodblock printing, which she sponsored in 764.

Kōken-Shōtoku granted significant responsibilities to Dōkyō, though his roles appeared more religious than political. The question of succession remained unresolved. Tensions escalated in 769 when an oracle from the Usa Hachiman Shrine declared that Dōkyō should become emperor. This tentative from someone unrelated to the imperial lineage to usurp the throne caused a scandal. However, sources documenting this event were written later and likely by Kōken-Shōtoku’s detractors.

Kōken-Shōtoku sent the courtier Wake no Kiyomaro to verify the oracle, and he returned with a new prophecy refuting the first. Furious, Dōkyō exiled Kiyomaro, further deepening court divisions. Kōken-Shōtoku withdrew with Dōkyō to Kawachi Province, ruling from there until her return to Nara in 770. She died later that year at age 52.

Following her death, women's roles at court changed and they were bared from ruling. It wasn’t until 1629, with Empress Meishō, and later Empress Go-Sakuramachi (1740–1813), that women once again sat on the throne, though their roles were largely symbolic.

The controversy surrounding Dōkyō tarnished Kōken's reputation. Before World War II, schoolchildren were taught that her so-called "feminine weakness" was why women shouldn’t rule.

Yet Kōken was far from a puppet ruler. She was a decisive leader with a will of her own. As the last great Japanese empress regnant, she deserves to be remembered for her accomplishments.

Enjoyed this post? You can support me on Ko-fi!

Japanese empresses regnant: Suiko, Kōgyōku-Saimei, Jitō, Genmei, Genshō

Further reading

Brown Norton Louise, Block Printing & Book Illustration in Japan

“Kōken, histoire de la dernière grande impératrice japonaise”

Tsurumi Patricia E., “Japan’s early female emperors”

Aoki Michiko Y., “Jitō Tennō, the female sovereign”,in: Mulhern Chieko Irie (ed.), Heroic with grace legendary women of Japan

#Kōken#Shōtoku#empress Kōken#history#women in history#women's history#historyedit#japanese history#japan#asian history#empresses#japanese empresses#queens#powerful women#historical figures

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

GO-SAKURAMACHI // EMPRESS OF JAPAN

“She was the 117th monarch of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. Her reign during the Edo period spanned the years from 1762 through to her abdication in 1771. The only significant event during her reign was an unsuccessful outside plot that intended to displace the shogunate with restored imperial powers. As of 2025, she remains the most recent empress regnant of Japan as the current constitution does not allow women to inherit the throne. Empress Go-Sakuramachi and her brother Emperor Momozono were the last lineal descendants of Emperor Nakamikado. Her nephew succeeded her as Emperor Go-Momozono upon her abdication in 1771. Go-Momozono died eight years later after a serious illness with no heir to the throne. A possible succession crisis was averted when Go-Momozono hastily adopted an heir on his deathbed upon the insistence of his aunt. In her later years, Go-Sakuramachi became a "guardian" to the adopted heir, Emperor Kōkaku, until her death in 1813.”

0 notes

Photo

Shōren-in: Autumn Splendor in Kyoto City! Shōren-in (青蓮院) during the autumn season in Kyoto-City. This is the Ryūjin-no-ike pond (龍神池 or Heavenly Dragon Pond) decorated with deep red autumn leaves. The granite stone bridge in front is called Koryu-no-hashi (跨龍橋). The large rock in the middle of the pond looks like the back of a dragon, bathing in the pond.

#Emperor Toba#Empress Go-Sakuramachi#Gyōgen#Japan#Kyoto#Shōren-in#Sōami#autumn#後桜町天皇#相阿弥#秋#行玄#青蓮院#鳥羽天皇

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

Different anon. But what is the problem for Japan accepting female rulers today? Both historically (at least five, like kogen) and legendary there have been many examples of ruling empresses, the latest Go-sakuramachi died in 1813.

You’d have to ask the Japanese scholars who oppose the move, preferring instead to reinstate members of the shinnoke and oke. Japan introduced agnatic succession in 1899 alongside the Meiji Constitution, influenced a great deal. In 1947, a revised Imperial Household Law made amending the succession possible within the Japanese Diet, which is why the succession crisis is debated there rather than up to the Emperor, but it also made only Hirohito’s immediate family eligible for succession, hence why there is such a dearth of eligible heirs.

Thanks for the question, Anon.

SomethingLikeALawyer, Hand of the King

12 notes

·

View notes

Video

<strong>Autumn Landscape Garden /Kyoto Sennyuji <a href="https://www.flickr.com/photos/100016856@N08/">by Masako Ishida</a></strong>

"location : Sennyu-ji temple Gozasyo-Teien Garden, Kyoto city,K yoto prefecture,Japan

京都 御寺 泉涌寺 御座所庭園

Sennyū-ji (泉涌寺 Sennyū-ji)is a Buddhist temple in Higashiyama-ku in Kyoto, Japan. For centuries, Sennyū-ji was a mortuary temple for aristocrats and the imperial house. Located here are the official tombs of Emperor Shijō and many of the emperors who came after him. Sennyū-ji was founded in the early Heian period. The origin of this temple, which is commonly called Mitera or Mi-dera, can be traced back to the Tenchō era (824-834) when the priest Kūkai established a small temple in this location. That modest structure and community were initially known as Hōrin-ji. The major buildings in Sennyū-ji was very much reconstructed and enlarged in the early 13th century.

Emperor Go-Horikawa and Emperor Shijō were the first to be enshrined in an Imperial mausoleum at Sennyū-ji. It was called Tsukinowa no misasagi.

Go-Momozono is also enshrined in Tsukinowa no misasagi along with his immediate Imperial predecessors since Emperor Go-Mizunoo -- Meishō, Go-Kōmyō, Go-Sai, Reigen, Higashiyama, Nakamikado, Sakuramachi, Momozono and Go-Sakuramachi. Nochi no Tsukinowa no Higashiyama no misasagi Kokaku, Ninko, and Komei are also enshrined at Nochi no Tsukinowa no Higashiyama no misasagi (後月輪東山陵). - wikipedia

ƒ/6.3 18.0 mm 1/50sec ISO500"

#dry landscape garden#temple#tempo#garden#Garten#traditional#Sennyu-ji#御座所庭園#Kyoto#Kioto#autumn#fall#color#colour#Canon#EOS M5#EF-M11-22mm f/4-5.6 IS STM#御寺#泉涌寺#京都#秋#pond#manual focus#manual exposure#霧雨#foggy

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Royal Birthdays for today, February 8th:

Yaroslav II, Grand Prince of Vladimir, 1191

Afonso IV, King of Portugal, 1291

Constantine XI Palaiologos, Byzantine Emperor, 1405

Ulrich, Duke of Württemberg, 1487

Sakuramachi, Emperor of Japan, 1720

Gia Long, Emperor of Vietnam, 1762

Caroline Augusta of Bavaria, Empress of Austria, 1792

Michael Pavlovich, Grand Duke of Russia, 1798

Elia Zaharia, Crown Princess of Albania, 1983

#caroline augusta of bavaria#michael pavlovich#elia Zaharia#afonso iv#Constantine XI Palaiologos#emperor Gia Long#emperor Sakuramachi#ulrich i#Yaroslav II#long live the queue#royal birthdays

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

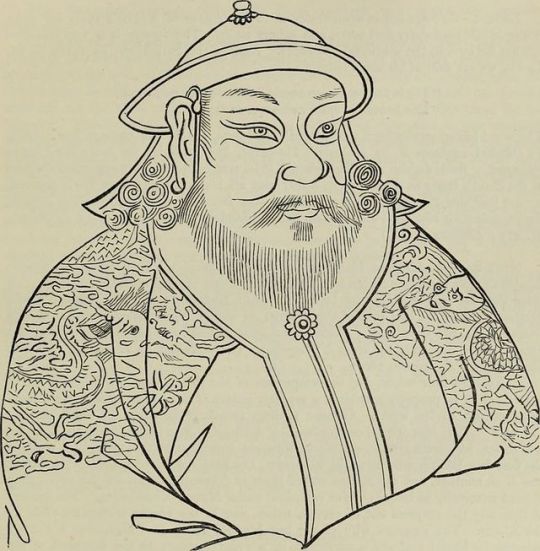

Royal birthdays for today, September 23rd:

Geoffrey II, Duke of Brittany, 1158

Kublai Khan, Mongolian Emperor, 1215

Eleonora Gonzaga, Holy Roman Empress, 1598

Ferdinand VI, King of Spain, 1713

Go-Sakuramachi, Empress of Japan, 1740

Marie Clotilde of France, Queen of Sardinia, 1759

Kokaku, Emperor of Japan, 1771

Juliane of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, Russian Grand Duchess, 1781

Marie Elisabeth, Princess of Saxe-Meiningen, 1853

Omar Ali Saifuddien III, Sultan of Brunei, 1914

#clotilde de france#Kublai Khan#eleonora gonzaga#ferdinand vi#emperor Kokaku#empress go sakuramachi#Juliane of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld#Princess Marie Elisabeth of Saxe-Meiningen#Omar Ali Saifuddien III#royal birthdays#long live the queue

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Royal Birthdays for today, February 8th:

Yaroslav II, Grand Prince of Vladimir, 1191

Afonso IV, King of Portugal, 1291

Constantine XI Palaiologos, Byzantine Emperor, 1405

Ulrich, Duke of Württemberg, 1487

Sakuramachi, Emperor of Japan, 1720

Gia Long, Emperor of Vietnam, 1762

Caroline Augusta of Bavaria, Empress of Austria, 1792

Michael Pavlovich, Grand Duke of Russia, 1798

Elia Zaharia, Crown Princess of Albania, 1983

#Yaroslav II#Caroline Augusta of Bavaria#michael pavlovich#afonso iv#Constantine XI Palaiologos#ulrich i#emperor Sakuramachi#emperor Gia Long#Elia Zaharia

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Royal birthdays for today, September 23rd:

Geoffrey II, Duke of Brittany, 1158

Kublai Khan, Mongolian Emperor, 1215

Bagrat III, King of Imereti, 1495

Eleonora Gonzaga, Holy Roman Empress, 1598

Ferdinand VI, King of Spain, 1713

Go-Sakuramachi, Empress of Japan, 1740

Marie Clotilde of France, Queen of Sardinia, 1759

Kokaku, Emperor of Japan, 1771

Juliane of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, Russian Grand Duchess, 1781

Marie Elisabeth, Princess of Saxe-Meiningen, 1853

#geoffrey ii#kublai khan#Eleonora Gonzaga#ferdinand vi#marie clotilde de france#empress Go-Sakuramachi#emperor kokaku#Juliane of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld#Princess Marie Elisabeth of Saxe-Meiningen#royal birthdays#long live the queue#Bagrat III

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Royal birthdays for today, September 23rd:

Geoffrey II, Duke of Brittany, 1158

Kublai Khan, Mongolian Emperor, 1215

Eleonora Gonzaga, Holy Roman Empress, 1598

Ferdinand VI, King of Spain, 1713

Go-Sakuramachi, Empress of Japan, 1740

Marie Clotilde of France, Queen of Sardinia, 1759

Kokaku, Emperor of Japan, 1771

Juliane of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, Russian Grand Duchess, 1781

Marie Elisabeth, Princess of Saxe-Meiningen, 1853

Duarte Nuno, Duke of Braganza, 1907

#madame clotilde#ferdinand vi#Kublai Khan#Geoffrey II#Eleonora Gonzaga#empress go sakuramachi#emperor Kokaku#Juliane of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld#Princess Marie Elisabeth of Saxe-Meiningen#duarte nuno#royal birthdays#long live the queue

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Royal Birthdays for today, February 8th:

Yaroslav II, Grand Prince of Vladimir, 1191

Afonso IV, King of Portugal, 1291

Constantine XI Palaiologos, Byzantine Emperor, 1405

Ulrich, Duke of Württemberg, 1487

Sakuramachi, Emperor of Japan, 1720

Gia Long, Emperor of Vietnam, 1762

Caroline Augusta of Bavaria, Empress of Austria, 1792

Michael Pavlovich, Grand Duke of Russia, 1798

Abdülaziz, Ottoman Sultan, 1830

Elia Zaharia, Crown Princess of Albania, 1983

#elia zaharia#michael pavlovich#caroline augusta of bavaria#emperor gia long#emperor Sakuramachi#duke ulrich#Constantine XI Palaiologos#Afonso IV#Yaroslav II#royal birthdays#long live the queue#Abdülaziz

75 notes

·

View notes