#elvira of castile

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Bastard Kings and their families

This is series of posts are complementary to this historical parallels post from the JON SNOW FORTNIGHT EVENT, and it's purpouse to discover the lives of medieval bastard kings, and the following posts are meant to collect portraits of those kings and their close relatives.

In many cases it's difficult to find contemporary art of their period, so some of the portrayals are subsequent.

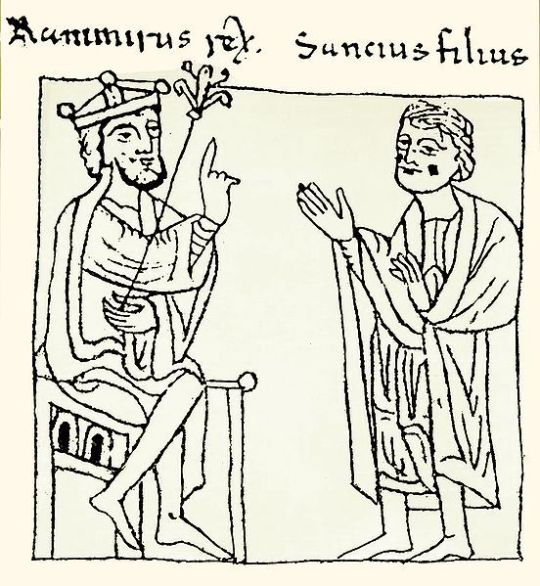

1) Ramiro I of Aragon (1006/7- 1063), son of Sancho III of Pamplona and Sancha de Aybar; with his son Sancho I of Aragon & V of Pamplona (1043-1094)

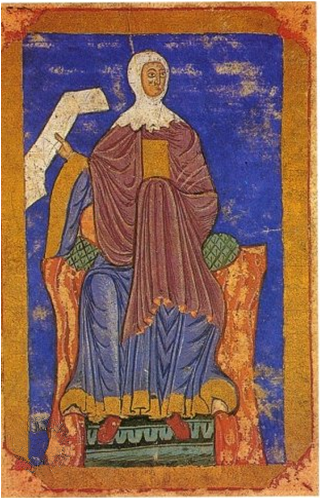

2) His wife, Ermesinda of Foix (1015 - 1049), mother of Sancho I of Aragon. Daughter of Bernard Roger de Foix and his wife Garsenda de Bigorra; and Sancha of Aragon (1045-1097), daughter of Ramiro I and Ermesinda

3) His father, Sancho III of Pamplona (992/96-1035), son of García II of Pamplona and Jimena Fernández

4) His brother, García III of Pamplona (1012-1054), son of Sancho III of Pamplona and his wife Muniadona of Castile

5) His nephew, Sancho IV of Pamplona (1039- 1076), son of García III of Pamplona and his wife Placencia of Normandy

6) His brother, Ferdinand I of Leon (1016- 1065), son of Sancho III of Pamplona and his wife Muniadona of Castile

7) His niece, Urraca of Zamora (1033-1101), daughter of Ferdinand I of Leon and Sancha of Leon

8) His niece, Elvira of Toro (1038-1099), daughter of Ferdinand I of Leon and Sancha of Leon

9) Sancho II of Castile (1038/1039-1072), son of Ferdinand I of Leon and Sancha of Leon

10) Alfonso VI of Leon (1040/1041-1109), son of Ferdinand I of Leon and Sancha of Leon

#jonsnowfortnightevent#jonsnowfortnightevent2023#asoiaf#a song of ice and fire#day 10#echoes of the past#historical parallels#medieval bastard kings#ramiro i of aragon#sancho i of aragon#sancha of aragon#ermesinda of foix#sancho iii of pamplona#garcía iii of pamplona#sancho iv of pamplona#ferdinand i of leon#urraca of zamora#elvira of toro#sancho ii of castile#alfonso vi of leon#bastard kings and their families#canonjonsnow

30 notes

·

View notes

Note

What are your favorite operas?

I'm bad with opera. Back when it was a mass rather than elite form, my great-grandparents named my paternal grandfather and his brothers and sisters after characters in Italian opera. My own namesake is disputed—John Hinckley and Pope John Paul II have been offered as options in the family—but my great uncle was John, Anglicized from Ernani, the titular character of Verdi's opera based on Victor Hugo's play riotously inaugurating "Romanticism, or the liberalism in literature," Hernani. A summary of the involuted plot from opera-online.com:

The action takes place in Spain in 1519. After the murder of his father, Don Juan of Aragon has become Ernani, leader of a troop of mountain rebels. Outlawed and pursued by the emissaries of Don Carlo, King of Castile, he loves and is loved by Elvira, but their love is impossible, as she is to wed an older relative, Ruy Gomez de Silva. The girl is also faced with the advances of Don Carlo, who is to become emperor under the name of Charles V. Ernani decides to kidnap his beloved just as Don Carlo is revealing his love to her. The three protagonists are surprised by Silva, who must bow before his king, whilst Ernani is able to flee. But the young man returns to Silva’s castle on the day of his wedding to Elvira. Silva, faithful to the laws of hospitality, refuses to turn over his outlaw rival to Don Carlo, who takes Elvira with him as a pledge of Silva’s loyalty. Ernani then enters into a pact with Silva: they will fight the king to save Elvira’s honour, then, as soon as the old man decides, he will sound his horn, which he entrusts to him to indicate to Ernani when it is time to die. Carlo, now Emperor Charles V, grants clemency to the conspirators and allows Ernani and Elvira to wed. But the sound of the horn rings out in the midst of the rejoicing. Silva, unyielding, demands what he is owed: the life of Ernani, who keeps his word by stabbing himself as the rejoicing old man looks on.

I'm sure I should listen to it, or even read Hernani, rather than contenting myself with the summaries. The spiritual significance of the name might be profound. With my namesake pope and saint, four years into whose reign I was born, I share a certain visionary strain (he began in Kraków as a poet and playwright); with the hapless assassin, now pacific musician, I share a certain inexorable fascination with my astral doppelgänger and the poet-pope-saint's great friend, Ronald Reagan. This conjunction might also be the basis of an opera. Call John Adams!

I first read about Hernani in Paul Berman's Terror and Liberalism. He traced Islamic fundamentalism to the Romantic irrationalism Hugo with his regicide-suicide plot supposedly introduced instead of the intended liberalism, and which coursed through fascism and communism on its way to Osama bin Laden and his suicide bombers. Not that what Berman himself ended up advocating wasn't also a disaster, but, even so, mightn't this be a warning against my own attempt to revive Romanticism, perhaps? What's in a name?

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ferdinand I of León

Artist: Antonio Maffei Rosal (Spanish, 1817-1868)

Date: 1855

Medium: Oil on Canvas

Collection: Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain

DESCRIPTION

The canvas depicts King Ferdinand I of León ( c.1016-1065 ), son of Sancho Garcés III of Pamplona , King of Pamplona, and Queen Jimena Fernandez. He promoted the Reconquista , conquering the towns of Lamego (1057), Viseo (1058) and Coimbra (1064), as well as subjecting several of the taifa kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula to the payment of parias to the Leonese kingdom. When he died, he divided his kingdoms among his sons: his first-born son, Sancho II , was given the kingdom of Castile and the parias on the taifa kingdom of Zaragoza . His second son, Alfonso VI , was given the kingdom of León and the imperial title, as well as the parias of the taifa kingdom of Toledo . The third son of Ferdinand I, Garcia , received the es , created for that purpose, and the parias of the taifa kingdoms of Seville and Badajoz . The princesses Urraca and Elvira were given the cities of Zamora and Toro , respectively, also with royal title and their own income.

#portrait#oil on canvas#king ferdinand of leon#spanish monarch#antonio maffei rosal#male#costume#desk#crown#spanish painter#museo del prado#spanish history#19th century painting#european art#11th century spain

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Et quia solum Guilielmum Capuanorum Principem habebat superstitem, veritus ne eumdem conditione humanae fragilitatis amitteret, Sibiliam sororem Ducis Burgundiae duxit uxorem, quae non multo post Salerni mortua est, et apud Caveam est sepulta. Tertio Beatricem filiam Comitis de Reteste in uxoris accepit, de qua filiam habuit, quem Constantiam appellavit.

Chronicon Romualdi II, archiepiscopi Salernitani, p. 16

Beatrice was born around 1135 in the county of Rethel (northern France) from Gunther (also know as Ithier) de Vitry, earl of Rethel, and Beatrice of Namur.

On her mother’s side, Beatrice descended from Charlemagne (through his son, Louis the Pious), while on the paternal side she was a grandniece of Baldwin II King of Jerusalem (her paternal grandmother Matilda, titular Countess of Rethel, was the King’s younger sister). The Counts of Rethel were also vassals of the powerful House of Champagne, known for its successful marriage politics (Count Theobald IV of Blois-Champagne’s daughter, Isabelle, would marry in 1143 Duke Roger III of Apulia, eldest son of King Roger II of Sicily).

In 1151, Beatrice married this same Roger. The King of Sicily was at his third marriage at this point. His first wife had been Elvira, daughter of King Alfonso VI the Brave of León and Castile and of Galicia, who bore him six children (five sons and one daughter). However, when four of his sons (Roger, Tancred, Alphonse and the youngest, Henry) died before him, leaving only William as his heir, Roger II must have feared for his succession. In 1149, the King then married Sibylla, daughter of Duke Hugh II of Burgundy. She bore him a son, Henry (named after his late older brother), and two years later died of childbirth complications giving birth to a stillborn son. As this second Henry died young too, Roger thought about marrying for a third (and hopefully last) time.

It is possible that Roger’s choice of his third wife had been influenced by the future bride’s family ties with the Crusader royalties as Beatrice was related with both Queen Melisende of Jerusalem and the Queen’s niece Constance of Hauteville, ruling Princess of Antioch. Constance was also a first cousin once removed of Roger, who had (unsuccessfully) tried to snatch the Antiochian principality from her when her father Bohemond II was killed in battle 1130, leaving his two years old daughter as heir.

Beatrice bore Roger only a daughter, Constance, who was born in Palermo on November 2nd 1154. This baby girl (who would one day become Queen of Sicily) never knew her father as he died on February 26th.

Nothing certain is known about her widowed life, although we can suppose she took care of her only daughter. Beatrice died in Palermo on March 30th 1185, living enough to see Constance being betrothed to Emperor Frederick Barbarossa’s son, Henry.

The body of the Dowager Queen was laid to rest in the Chapel of St. Mary Magdalene, together with her predecessor, Elvira, and her step-children, Henry, Tancred, Alphonse and Roger. Through her daughter, Beatrice would become Emperor Frederick II’s grandmother.

Sources

Cronica di Romualdo Guarna, arcivescovo Salernitano Chronicon Romualdi II, archiepiscopi Salernitani Versione di G. del Re, con note e dilucidazione dello stesso

Garofalo Luigi, Tabularium regiae ac imperialis capellae collegiatae divi Petri in regio panormitano palatio Ferdinandi 2. regni Utriusque Siciliae regis

Hayes Dawn Marie, Roger II of Sicily. Family, Faith, and Empire in the Medieval Mediterranean World

Houben Hubert, Roger II Of Sicily: A Ruler Between East And West

SICILY/NAPLES: COUNTS & KINGS

Walter Ingeborg, BEATRICE di Rethel, regina di Sicilia, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 7

#historicwomendaily#women#history#women in history#historical women#House of Hauteville#Roger II of Sicily#Beatrice of Rethel#norman swabian sicily#costanza i#people of sicily#women of sicily#myedit#historyedit

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queens and Princesses of the Spanish Kingdoms: Ages at First Marriage

I have only included women whose birth dates and dates of marriage are known within at least 1-2 years, therefore, this is not a comprehensive list. This data set ends with the transition to Habsburg-controlled Spain.

Sancha, wife of King Fernando I of Léon; age 14 when she married Fernando in 1032 CE

Ermesinda of Bigorre, wife of King Ramiro I of Aragon; age 21 when she married Ramiro in 1036 CE

Sancha, daughter of King Ramiro I of Aragon; age 18 when she married Count Ermengol III of Urgell in 1063 CE

Constance of Burgundy, wife of King Alfonso VI of Léon & Castile; age 19 when she married Count Hugh II of Chalon in 1065 CE

Felicia of Roucy, wife of King Sancho of Aragon; age 16 when she married Sancho in 1076 CE

Agnes of Aquitaine, wife of King Pedro I of Aragon; age 14 when she married Pedro in 1086 CE

Teresa, daughter of King Alfonso VI of Léon & Castile; age 13 when she married Count Henri of Burgundy in 1093 CE

Elvira, daughter of King Alfonso VI of Léon & Castile; age 15 when she married Count Raymond IV of Toulouse in 1094 CE

Bertha, wife of King Pedro I of Aragon; age 22 when she married Pedro in 1097 CE

Elvira, daughter of King Alfonso VI of Léon & Castile; age 17 when she married King Ruggero II of Sicily in 1117 CE

Berenguela of Barcelona, wife of King Alfonso VII of Léon & Castile; age 12 when she married Alfonso in 1128 CE

Urraca, daughter of King Alfonso VII of Léon; age 11 when she married King Garcia Ramirez of Navarre in 1144 CE

Petronilla, daughter of King Ramiro II of Aragon; age 14 when she married Count Ramon Berenguer IV of Barcelona in 1150 CE

Richeza of Poland, wife of King Alfonso VII of Léon & Castile; age 12 when she married Alfonso in 1152 CE

Sancha, daughter of King Alfonso VII of Léon & Castile; age 14 when she married King Sancho VI of Navarre in 1153 CE

Constanza, daughter of King Alfonso VII of Léon & Castile; age 16 when she married King Louis VII of France in 1154 CE

Urraca of Portugal, wife of King Fernando II of Léon; age 17 when she married Fernando in 1165 CE

Eleanor of England, wife of King Alfonso VIII of Castile; age 9 when she married Alfonso in 1170 CE

Sancha of Castile, wife of King Alfonso II of Aragon; age 20 when she married Alfonso in 1174 CE

Dulce, daughter of Queen Petronilla of Aragon; age 14 when she married King Sancho I of Portugal in 1174 CE

Berenguela, daughter of King Alfonso VIII of Castile; age 7 when she married Duke Conrad II of Swabia in 1187 CE

Marie of Montpellier, wife of King Pedro II of Aragon; age 10 when she married Viscount Raymond Geoffrey II of Marseille in 1192 CE

Garsenda of Foralquier, wife of Prince Alfonso II of Aragon; age 13 when she married Alfonso in 1193 CE

Constance of Toulouse, wife King Sancho VII of Navarre; age 15 when she married Sancho in 1195 CE

Constanza, daughter of King Alfonso II of Aragon; age 19 when she married King Emeric of Hungary in 1198 CE

Blanca of Castile, daughter of King Alfonso VIII of Castile; age 12 when she married King Louis VIII of France in 1200 CE

Eleonora, daughter of King Alfonso II of Aragon; age 22 when she married Count Raymond VI of Toulouse in 1204 CE

Urraca, daughter of King Alfonso VIII of Castile; age 19 when she married King Afonso II of Portugal in 1206 CE

Mafalda of Portugal, wife of King Enrique I of Castile; age 20 when she married Enrique in 1215 CE

Sancha, daughter of King Alfonso II of Aragon; age 25 when she married Count Raymond VII of Toulouse in 1211 CE

Elisabeth of Swabia, wife of King Fernando III of Castile; age 14 when she married Fernando in 1219 CE

Eleonora of Castile, wife of King Jaime I of Aragon; age 19 when she married Jaime in 1221 CE

Berenguela, daughter of King Alfonso IX of Léon; age 20 when she married Emperor Jean I of Brienne in 1224 CE

Marguerite of Bourbon, wife of King Teobaldo I of Navarre; age 15 when she married Teobaldo in 1232 CE

Yolanda of Hungary, wife of King Jaime I of Aragon; age 20 when she married Jaime in 1235 CE

Joan of Dammartin, wife of King Fernando III of Castile; age 17 when she married Fernando in 1237 CE

Yolanda, daughter of King Jaime I of Aragon; age 13 when she married King Alfonso X of Castile in 1249 CE

Isabelle of France, wife of King Teobaldo II of Navarre; age 14 when she married Teobaldo in 1255 CE

Kristina of Norway, wife of Prince Felipe of Castile; age 24 when she married Felipe in 1258 CE

Beatriz, daughter of King Teobaldo I of Navarre; age 16 when she married Duke Hugues IV of Burgundy in 1258 CE

Constanza, daughter of King Jaime I of Aragon; age 21 when she married Prince Manuel of Castile in 1260 CE

Constanza of Sicily, wife of King Pedro III of Aragon; age 13 when she married Pedro in 1262 CE

Isabel, daughter of King Jaime I of Aragon; age 14 when she married King Louis IX of France in 1262 CE

Beatrice of Savoy, wife of Prince Manuel of Castile; age 18 when she married Pierre of Chalon in 1268 CE

Blanche of France, wife of Prince Fernando of Castile; age 16 when she married Fernando in 1269 CE

Blanche of Artois, wife of King Enrique I of Navarre; age 21 when she married Enrique in 1269 CE

Beatriz, daughter of King Alfonso X of Castile; age 17 when she married Marquis William VII of Montferrat in 1271 CE

Esclaramunda of Foix, wife of King Jaime II of Majorca; age 25 when she married Jaime in 1275 CE

Maria de Molina, wife of King Sancho IV of Castile; age 17 when she married Sancho in 1282 CE

Yolanda, daughter of King Alfonso X of Castile; age 17 when she married Diego Lopez V de Haro in 1282 CE

Juana, daughter of King Enrique I of Navarre; age 11 when she married King Philippe IV of France in 1284 CE

Maria Diaz I de Haro, wife of Prince Juan of Castile; age 17 when she married Juan in 1287 CE

Yolanda, daughter of Prince Manuel of Castile; age 12 when she married Prince Afonso of Portugal in 1287 CE

Isabel, daughter of King Pedro III of Aragon; age 17 when she married King Denis of Portugal in 1288 CE

Isabel of Castile, wife of King Jaime II of Aragon; age 8 when she married Jaime in 1291 CE

Blanche of Anjou, wife of King Jaime II of Aragon; age 15 when she married Jaime in 1295 CE

Yolanda, daughter of King Pedro III of Aragon; age 24 when she married Prince Roberto of Naples in 1297 CE

Constanza of Portugal, wife of King Fernando IV of Castile; age 12 when she married Fernando in 1302 CE

Beatriz, daughter of King Sancho IV of Castile; age 16 when she married King Afonso IV of Portugal in 1309 CE

Maria, daughter of King Jaime II of Aragon; age 12 when she married Prince Pedro of Castile in 1311 CE

Constanza, daughter of King Jaime II of Aragon; age 12 when she married Prince Juan Manuel of Villena in 1312 CE

Teresa d'Entença, wife of King Alfonso IV of Aragon; age 14 when she married Alfonso in 1314 CE

Marie of Lusignan, wife of King Jaime II of Aragon; age 42 when she married Jaime in 1315 CE

Isabel, daughter of King Jaime II of Aragon; age 10 when she married King Frederick I of Germany in 1315 CE

Eleonora of Castile, wife of Prince Jaime of Aragon; age 12 when she married Jaime in 1319 CE

Elisenda of Montcada, wife of King Jaime II of Aragon; age 30 when she married Jaime in 1322 CE

Blanca de La Cerda y Lara, wife of Prince Juan Manuel of Castile; age 10 when she married Juan Manuel in 1327 CE

Constanza, daughter of King Alfonso IV of Aragon; age 18 when she married King Jaime III of Majorca in 1336 CE

Cecilia of Comminges, wife of Prince Jaime of Aragon; age 16 when she married Jaime in 1336 CE

Maria of Navarre, wife of King Pedro IV of Aragon; age 8 when she married Pedro in 1337 CE

Leonor of Portugal, wife of King Pedro IV of Aragon; age 19 when she married Pedro in 1347 CE

Eleonora of Sicily, wife of King Pedro IV of Aragon; age 24 when she married Pedro in 1349 CE

Juana Manuel, daughter of Prince Juan Manuel; age 11 when she married King Enrique of Castile in 1350 CE

Blanche of Bourbon, wife of King Pedro of Castile; age 14 when she married Pedro in 1353 CE

Constanza, daughter of King Pedro IV of Aragon; age 18 when she married King Federico of Sicily in 1361 CE

Maria de Luna, wife of King Martin of Aragon; age 14 when she married Martin in 1372 CE

Juana, daughter of King Pedro IV of Aragon; age 29 when she married Count Juan I of Ampurias in 1373 CE

Marthe of Armagnac, wife of King Juan I of Aragon; age 26 when she married Juan in 1373 CE

Beatriz of Portugal, wife of Prince Sancho of Castile; age 19 when she married Sancho in 1373 CE

Eleonora of Aragon, daughter of King Pedro IV of Aragon; age 17 when she married King Juan I of Castile in 1375 CE

Eleonora, daughter of King Enrique II of Castile; age 12 when she married King Carlos III of Navarre in 1375 CE

Isabel of Portugal, wife of Count Alfonso Enriquez; age 13 when she married Alfonso in 1377 CE

Violant of Bar, wife of King Juan I of Aragon; age 15 when she married Juan in 1380 CE

Beatriz of Portugal, wife of King Juan I of Castile; age 10 when she married Juan in 1383 CE

Juana, daughter of King Juan I of Aragon; age 17 when she married Count Matthieu of Foix in 1392 CE

Eleonora of Albuquerque, wife of King Fernando I of Aragon; age 20 when she married Fernando in 1394 CE

Yolanda, daughter of King Juan of Aragon; age 19 when she married Duke Louis II of Anjou in 1400 CE

Blanca I of Navarre, wife of Prince Martin of Aragon; age 15 when she married Martin in 1402 CE

Juana, daughter of King Carlos III of Navarre; age 20 when she married Count Jean I of Foix in 1402 CE

Beatriz, daughter of King Carlos III of Navarre; age 14 when she married Count James II of La Marche in 1406 CE

Isabel, daughter of King Pedro IV of Aragon; age 31 when she married Count Jaime II of Urgell in 1407 CE

Margarita of Prades, wife of King Martin of Aragon; age 14 when she married Martin in 1409 CE

Maria of Castile, wife of King Alfonso V of Aragon; age 14 when she married Alfonso in 1415 CE

Catalina of Castile, wife of Prince Enrique of Aragon; age 15 when she married Enrique in 1418 CE

Isabel, daughter of King Carlos III of Navarre; age 24 when she married Jean IV of Armagnac in 1419 CE

Maria, daughter of King Fernando I of Aragon; age 17 when she married King Juan II of Castile in 1420 CE

Eleonora, daughter of King Fernando I of Aragon; age 26 when she married King Duarte of Portugal in 1428 CE

Agnes of Cleves, wife of Prince Carlos of Aragon; age 17 when she married Carlos in 1439 CE

Blanca II of Navarre, daughter of King Juan II of Aragon and Queen Blanca I of Navarre; age 18 when she married King Enrique IV of Castile in 1440 CE

Eleonora of Navarre, daughter of King Juan II of Aragon and Queen Blanca 1 of Navarre; age 15 when she married Count Gaston IV of Foix in 1441 CE

Juana Enriquez, wife of King Juan II of Aragon; age 19 when she married Juan in 1444 CE

Isabel of Portugal, wife of King Juan II of Castile; age 19 when she married Juan in 1447 CE

Joana of Portugal, wife of King Enrique IV of Castile; age 16 when she married Enrique in 1455 CE

Isabel I of Castile, wife of King Fernando II of Aragon; age 18 when she married Fernando in 1469 CE

Juana, daughter of King Enrique IV of Castile; age 13 when she married King Afonso V of Portugal in 1475 CE

Juana, daughter of King Juan II of Aragon; age 21 when she married King Fernando I of Naples in 1476 CE

Isabel, daughter of King Fernando II of Aragon; age 20 when she married Prince Afonso of Portugal in 1490 CE

Juana, daughter of King Fernando II of Aragon; age 22 when she married Felipe I of Castile in 1501 CE

Margaret of Austria, wife of Prince Juan of Aragon; age 17 when she married Juan in 1497 CE

Maria, daughter of King Fernando II of Aragon; age 18 when she married King Manuel I of Portugal in 1500 CE

Catalina, daughter of King Fernando II of Aragon; age 15 when she married Prince Arthur of England in 1501 CE

Germaine of Foix, wife of King Fernando II of Aragon; age 18 when she married Fernando in 1506 CE

112 women; average age at first marriage was 16. The eldest bride was 42 years old, and the youngest was 7.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

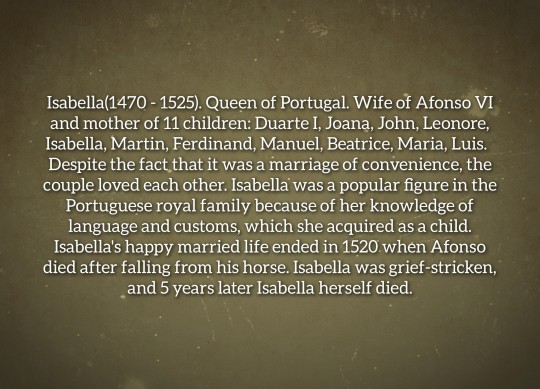

AU House of Trastamara: Children Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon.

Isabella(1470 - 1525). Queen of Portugal. Wife of Afonso VI and mother of 11 children: Duarte I, Joana, John, Leonore, Isabella, Martin, Ferdinand, Manuel, Beatrice, Maria, Luis. Despite the fact that it was a marriage of convenience, the couple loved each other. Isabella was a popular figure in the Portuguese royal family because of her knowledge of language and customs, which she acquired as a child. Isabella's happy married life ended in 1520 when Afonso died after falling from his horse. Isabella was grief-stricken, and 5 years later Isabella herself died.

Ines(1473 - 1495). Married to the Venetian Doge Marcantonio Trevisan. Had two children by him: Piero and Lucrezia. Died before her husband became Doge. Their marriage was not long and very unhappy. Died in childbirth, giving birth to twins.

Alfonso XII(1475 - 1540). King of Spain. From 1504 king of Castile, and from 1516 of Aragon. He united 2 kingdoms into one country. After ascension to the throne he continued the policy of his parents, expanded the lands of Spain. Organize campaigns against the Turks, in which he personally took part. And also actively engaged in the cultural dedication of his state. In 1493 he married Luisa Medici, daughter of Lorenzo the Magnificent. The married life of Alfonso and Luisa was happy, the marriage gave birth to 9 children: Ferdinand VI, Pilar, Clarice, Henry, Lorenzo, Isabella, Pablo, Miguel and Antonio.

Beatrice(1486 - 1514). Queen of France. Wife of Charles VIII. Their marriage was an ordinary political alliance. Beatrice fell in love with her husband after a while, but he paid little attention to her. Charles preferred to spend his time in the company of his favorites. They gave birth to 5: Louis XII, Josephine, Francis I, Joffroy, Madeleine. The French did not like their queen either, but then she was able to win their love. Beatrice did a lot of charity work. She opened churches, free canteens, schools for the poor and their children. Died 10 days after the birth of her two daughters.

John(1478 - 1538). Grand Master of the Order of Santiago. Count de Alburquerque. Husband of Margaret of Austria. John loved his wife very much and was always interested in her opinion on any matter. They had 4 children: Sancha, Miguel, Elvira, Ramiro. He was the main advisor of his older brother. Personally participated in all military campaigns. He suffered the death of his wife, survived her by 8 years. He contracted the plague while returning home from a campaign and died a few days later.

AU: Дети Изабеллы Кастильской и Фердинанда Арагонского.

Изабелла(1470 - 1525). Королева Португалии. Жена Афонсу VI и мать 11 детей: Дуарте I, Жуана, Жуан, Леонор, Изабелла, Мартин, Фердинанд, Мануэль, Беатриса, Мария, Луис. Не смотря на то, что брак был по расчёту супруги любили друг друга. Изабелла была популярной фигурой в португальской королевской семье благодаря тому, что имела неплохие познания в языке и обычаях, которые она приобрела ещё в детстве. Счастливая супружеская жизнь Изабеллы окончилась в 1520 году, когда Афонсу погиб упав с лошади. Изабелла была убита горем, а ещё через 5 лет не стало и самой Изабеллы.

Инес(1473 - 1495). Была замужем за веницианским дожем Маркантонио Тревизаном. Родила от него 2 детей: Пьеро и Лукреция. Умерла до того как её муж стал дожем. Их брак был не долгим и очень не счастливым. Умерла при родах, рожая на свет близнецов.

Альфонсо XII(1475 - 1540). Король Испании. С 1504 года король Кастилии, а с 1516 Арагона. Объединил 2 королевства в одну страну. После восшествия на престол продолжил политику своих родителей, расширил земли Испании. Организовывал походы против турок, в которых лично принимал участие. А также активно занимался культурным просвящением своего государства. В 1493 году женился на Луизе Медичи, дочери Лоренцо Великолепного. Супружеская жизнь Альфонсо и Луизы была счастливой, в браке родилось 9 детей: Фердинанд VI, Пилар, Клариче, Энрике, Лоренцо, Изабелла, Пабло, Мигель и Антонио.

Беатриса(1486 - 1514). Королева Франции. Жена Карла VIII. Их брак был обычным политическим союзом. Беатриса через некоторое время полюбила своего мужа, но он уделял ей мало внимания. Карл предпочитал проводить время в обществе своих фавориток. У них родилось 5: Людовик XII, Жозефина, Франциск I, Жоффруа, Мадлен. Французы тоже не долюбливали свою королеву из за того, что она была испанкой, но потом она смогла заваювать их любовь. А когда она умерла, то искренне оплакивали ее кончину. Беатриса занималась благотворительностью: открывала церкви, бесплатные столовые, школы для бедняков и их детей. Умерла через 10 дней после рождения 2 дочери.

Хуан(1478 - 1538). Великий Магистр ордена Сантьяго. Граф де Альбуркерке. Муж Маргариты Австрийской. Хуан очень сильно любил свою жену и всегда интересовался её мнением по любым вопросам. У них родилось 4 детей: Санча, Мигель, Эльвира, Рамиро. Был главным советником своего старшего брата. Лично участвовал во всех военных походах. Тяжело перенёс смерть своей жены, пережил её на 8 лет. Заразился чумой когда возвращался домой из похода и через несколько дней умер.

Part 1.

#history#history au#spain#spanish#spanish history#isabella#IsabellaofCastile#FerdinandofAravon#royal family#royalty#Isabel#catherine of aragon#henry viii#the tudors#mary tudor#15th century#16th century#au#spanish princess#the spanish princess#spanish royal family#spanish royalty#Royal#Royals

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

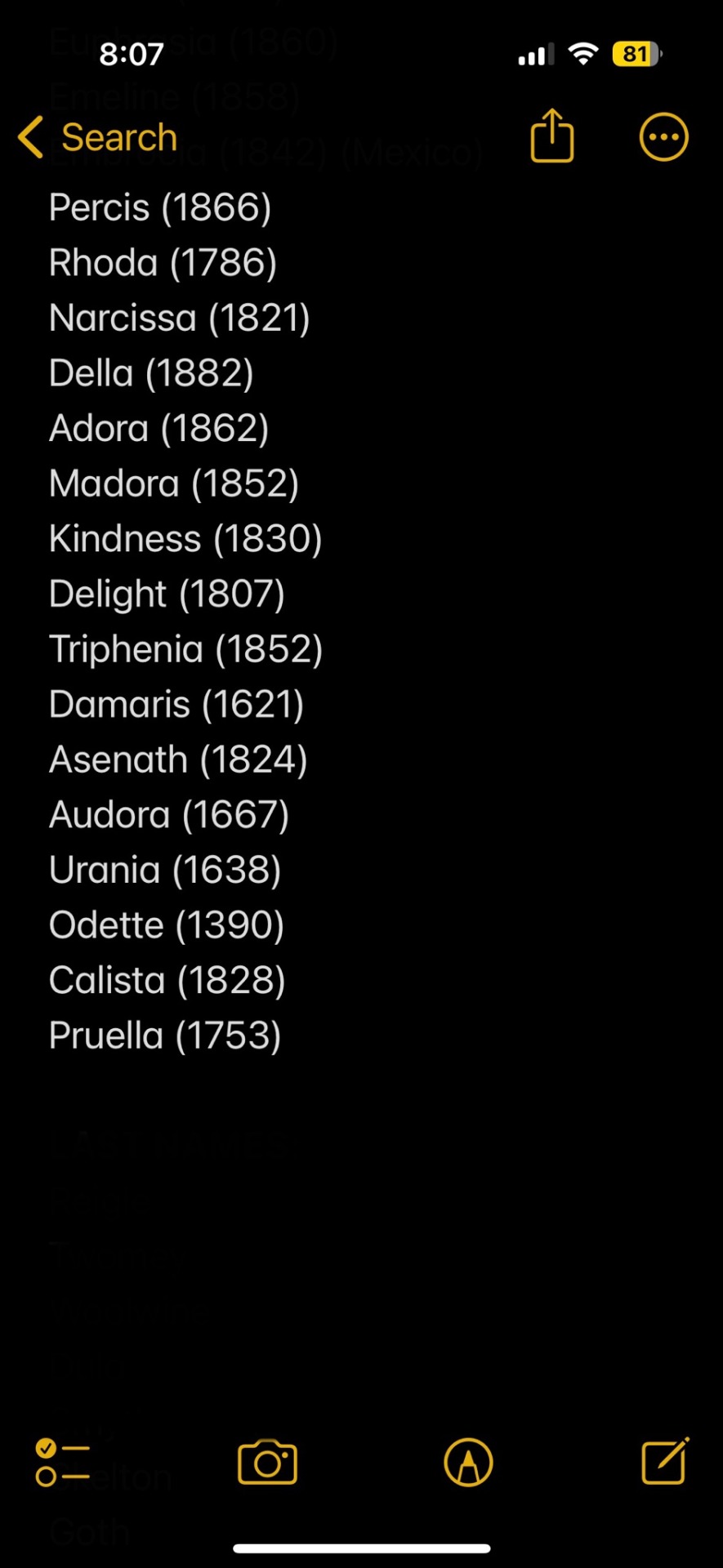

[id: list of names on notes app, four images total. List from top top to bottom: Vera, Zipporah, Zelba (1854), Saturine (1893, Spain), Orrila (1818), Elvira (1826), Sevilla (1810), Zoeth (1860), Zelica (1819), Vestilla (1832), Permelia (1760), Hezetina (1896), Neoma (1840), Homiselle (1874), Izora (1849), Zella (1849), Thurza (1854), Sabra (1782), Soledad (means lonely), Euphemia (1317, means well-spoken), Drucilla (1817), Dyanthe (ancient, 1849), Manira (1849), Fezzie (1889), Vona (1878), Fenella (1862), Lilya (Finnish), Lavina (1810), Lovenia (1841), Evaline (1825), Marcelona (1875), Esteline (1840), Edmonia "Eddie" (1863), Alcinda (1819), Artress (1892), Arminta "Mint" (1874), Sibbella (1760, ancient), Zilphia (1796), Thyrza (1850), Fidelia (1844), Zaida (1816, ancient), Violante (1265, Castile), Alexandrine (1798), Advisa (1003), Edigna (1055), Aristylla (Ancient Greece), Herculine (1838, French), Lucretia (510 BC, Ancient Rome), Claudette (1903), Guillermina (1905, Mexico), Germaine (1930), Theodosia (1806), Eulala (1860), Arabine (1850), Alcy (1762), Content (1805, Puritan), Tryphosa (1825), Zina (1828), Zeruah (1784), Elnora (1830), Postumia (Ancient Rome), Dervorguilla (1210, Gaelic), Gatsy (1905), Zerviah (1754), Millie Bell (1874), Iva (1901), Adeline (1789), Paradine (1853), Marcella (1839), Eudoxia, Ermengarde (1170), Amice (1264), Annis (1507), Artemisia (1593), Dove (1895), Eupraxia (1067), Margaretha (1802, Swiss), Hyacinthia (1834), Placida (1887, Mexican), Peonie (1879), Ernestine (1740), Valeria (1862), Euphrasia (1860), Emeline (1858), Embrocia (1842, Mexico), Percis (1866), Rhoda (1786), Narcissa (1821), Della (1882), Adora (1862), Madora (1852), Kindness (1830), Delight (1807), Triphenia (1852), Damaris (1621), Asenath (1824), Audora (1667), Urania (1638), Odette (1390), Calista (1828), Pruella (1753).]

Since you guys like my male name list, here are some vintage girl’s names from old historic documents, recently updated:

(Sorry I listed the name origin/individual’s place of birth on some and not others.)

23K notes

·

View notes

Text

Everything wrong with Spanish Princess-1x06

Catherine waits for dispensation and dowry, writing to her mother.that was true.

But to say how she and Henry are in love and plan their future and how they’d rule together, is totally false. In real life she barely could not see Harry that much on few occasions she visisted court between 1503 and late 1505. And not much after too. Partly because she was often sick in real life during her dowager years, and because his father was very protective of his son.

Catehrine is seemingly compassionate towards lady Pole-but actually i think such character would wish lady Pole to be well, in order to keep her mouth shut.

Isabella died in December 1504. Juana and Philip ships were carried by storm to English coast in January 1506. They skipped 2,5 years! The missed due date of dowry, etc. They missed Henry VII trying to console Catherine after her mother died, fiasco in Andalusia, Catherine moving away from Durham house to court, dona Elvira fleeing, Catherine’s father remarrying. And much more!

Basically they skipped 2,5 years of the drama! Those were very eventful and emotional years for Catherine!

Juana’s outfit is not even remotely Spanish nor Netherlandish. Nor English But since no constumes truly are accurate(rarely even remotely) i should stop complaining about that.

So lady Margaret speaks Latin and Spanish(in the tv show only), and instead talks to Philip and Juana in English? And they understand her?!

I don’t think they’d take Philip’s sword.

Juana and Catherine barely spoke during the visit, in real life.

Juana is being jerk too-does it run in family? Juana’s religious doubts are imo very overexagerated in TSP. She attended masses, she just wasn’t overzealous as some of family. That doesn’t mean she was atheist! And I hate that it was presented thaht way!

Tbh, Philip looks too handsome. In real life he was ugly. Habsburg Empire again?! Juana ordering her husband around!?

Henry says Ferdiand woudln’t pay the dowry-that is true. He tried to push that on castile solely(whetever rightfully or not idk.). But nobody would think Catherine’s rank became too low to be wed to future King of England, this is false narrative, myth often repeated-which wasn’t real cause for Catherine and Henry VIII not marrying in 1505.

Henry VII wouldn’t refer to Juana and Philip as spanish royals-but as castilian royals. Lazy writing! Oh, more of false fued between father and son.

Scenes set in summer etc. even though visit of Juana and Philip happened in winter and early spring. (This keeps happening and I am sick of it. I know of tv shows which also shooted in summer, but they at least pretended it was not so!)

Tbh, one tapestry hanging on those walls would pay lady Pole’s taxes. Presenting it otherwise is false. Tapestries were VERY expensive.

Then Catherine asks Juana about her new baby boy, upon which Juana replies her boy stayed at home with her children and nursemaid (she means wet-nurse-wrong use of language, lazy writing!).

This is very inaccurate, as i said Ferdinand was born in March 1503 in Spain, and he stayed there! Not with rest of his siblings. Then in September 1505 Juana gave birth to daughter called Mary-who was newest baby in the family. Yet they skipped her!

Henry VII was nice to Juana, true but he and Henry VII were way more interacting with Philip, way more honoring him over her. Way more than in all of scenes in Spanish Princess. Harry considered Philip good friend, became his penpal and was deeply sadenned by his death. It shaken him.

Henry VII certainly did not forget himslef while looking at Juana, he always kept state business as priority. He negotiated bethrohal of Mary Rose Tudor to future Charles V, and in great detail he negotiated proposed wedding to Philip’s sister Margaret of Austria. She rejected the match.

That is what happened in real life.

Juana didn’t throw wine at her husband in public. In fact entire visit she was acting completely sane. But Juana was not at all as cynical about men. It is also unclear who is abusing whom-Juana Philip or Philip Juana in TSP.

How long is Rosa pregnant now? 3 years?! 3,5? Her baby should have been long born and walking!

It wasn’t just about fleet of Juana and Philip being damaged, but also it being scattered across southern english coast, it took lot of time to get back together.

Juana certainly wouldn’t be rudely implying English need gold. In fact, Henry VII gave ‘loan’(gift) to Philip’s father Maxmiloan-of 100,000. He had money to throw away. And he used it to get Edmund de la Pole.

Absolute misrepresentation!

Rosa loses the baby. Philip cheats upon Juana in public(as men appear to be in habit doing in this tv show. Fuck in public, all the time.)

Juana says she doesn’t believe in god, outloud. Untrue.

Walked through fire to get to her?! That is not what happened in the tv show nor in real life. She also says Harry will do anything she asks-that is now how yu speak of amn you supposedly love. But one who is mere pawn to you.

(This not acceptable portrayal of Catherine! Nor Juana.)

Pretty sure I’ve seen piano in background scene of Juana and Catherine talking in church. Tudor soldiers stopping Juana?! Why? On foot she’d not get far, plus there was another gate behind 1st! She would still be on royal property.

Philip speaks English?! And says his father supports Edmund de la Pole?! WTF?

Henry VII is suggesting to disown his only son?! To be slapped when you say you can’t wait your parent to die, is totally justified. But would never happen in real life, though. The feud is complete fiction and Henry VIII didn’t try to break his son’s will.

Juana and Harry never had affair, as i said he spent more time with Philip.

(I agree with Thistle-you’d have more evidence for affair between Harry and Philip than of Harry and Juana! based upon this visit. Harry was fallowing Philip almost like puppy.)

Juana’s supposed torture has no historical evidence to support it. It’s possible she suffered emotionally due to not being zealous enough and being part of zealous/very pious family, but there is no evince that she was ever tortured due to this. And I recall seeing tumbrl posts about where such rumour started-not contemporary rumour at all. (And even those wouldn’t have to be reliable, as I often point out.)

Juana tells Catherine their mother renounced her, and Catherine slaps her. It didn’t happen in real life. But still Juana nor Philip intended to pay Catherine’s dowry.

Henry being sexist in his speech, Juana supposedly seducting Harry. (what will be next? Will her next daughter be Harry’s? It’s so ridiculous!).

Catherine calls her sister Joanna, instead of Juana. Aren’t they supposed to be Spanish?

Juana had no part in handing over Edmund de la Pole and she wouldn’t call herself Queen of Spain. She was Queen fo Castile only!

(As long as her father lived, lazy writing!)

But she was right Maxmillian wouldn’t support Edmund de la Pole’s claim.

Margaret saying Juana doesn’t believe in God? In public?! Also, Juana was never confidently standing up against her husband, in real life.

Lady Margaret being heartless villain and making lady Pole miserable. So wrong.Juana being heartless to Catherine, stating that instead of helping her sister she’d rather bethrohe her own daughter english prince.

The supposed bethrohal between Eleanor of Austria and future Henry VIII, didn’t take place! It’s myth. Nothing to back up that it occured in 1506.

Yet they go once again they don’t care.

By this point it is laughable to say this is real story of Catherine. We see nothing of her actual personality, nothing of her household, nothing of the actual exchanges between royal courts, nothing of her actual relationship with boy who was to be her husband. It’s a story, but not her story.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

ALFONSU III

King of Asturias

THE GREAT

(born c. 848/49 - died 910)

pictured above is an imagined portrait of the King of Asturias, by Eduardo Cano de la Peña from 1852

-------------------- ~ -------------------- ~ --------------------

SERIES - Descendants of the Kings of Asturias: Alfonsu was King of Asturias from 866.

-------------------- ~ -------------------- ~ --------------------

ALFONSU was born around 848-49, on an unknown location at the Kingdom of Asturias.

His parents were Infante Ordoñu of Asturias and his wife Nuña, and he was a member of a branch line of the ASTUR-LEONESE DYNASTY. His name was ALFONSU ORDÓÑEZ, meaning Alfonsu son of Ordoñu.

By 850 his grandfather Ramiru I, King of Asturias died and his father immediatly succeeded as King Ordoñu I. And probably on his father's accession he became an INFANTE OF ASTURIAS.

When his father died in 866 he succeded as ALFONSU III, KING OF ASTURIAS, but a certain Count Froila from Galicia tried to usurp his throne. He then fled to Álava and was only able to regain control over Asturias a few months later, after Count Froila was killed.

However unlike King Nepocianu, the other defeated usurper of the Asturian throne, Count Froila is not considered to have been King of Asturias.

He married a certain Ximena around 860-70, so it is not known if he was already King or not at the time of his wedding. They probably had eight children (check the list below), at least five sons and three daughters.

As some sources believe that his wife was a Navarrese Royal, one of the daughters of Gartzia I Enekoitz, King of Pamplona and his first wife Urraka, the marriage could have been arranged as an alliance between Asturias and the newly established Kingdom of Pamplona.

Early in his reign he conquered Oporto (currently in Portugal) and for two decades he fought the Emirate of Córdoba, over old and new Asturian terriories, until they finally made peace around 884.

In the early 900s his internal problems began as his family started to rebel. Some sources believe that in 909 his eldest son Infante García tried to took the power with the support of his mother and brothers around 909 but was defeated and imprisoned.

However theses sources also believe that his family forced him to abdicate in 910, before his death, and the Kingdom of Asturias was divided between his eldest sons. After which the capital of the Kingdom was changed from Oviedo to the city of León.

The King of Asturias died sometime in 910, in Zamora, when he was returning from a battle, probably against his sons. He was probably already in his sixties.

-------------------- ~ -------------------- ~ --------------------

Though, sources diverge on when his sons took the power and divided the Kingdom. Some believe he was forced to abdicate before his death and others believe that his sons only inherited the Kingdom after his death.

Each of his three eldest sons received:

Infante García - received León, Álava and Castille and became known as King of León;

Infante Ordoñu - received Galicia and became known as King of Galicia;

Infante Fruela - received the remainder of Asturias, around Oviedo, and became known as King of Asturias.

-------------------- ~ -------------------- ~ --------------------

Check my posts on ALFONSU III's family, his Royal House and his Kingdom!

ALFONSU III and his wife XIMENA may have had eight children...

García I, King of León - husband of Muniadona;

Ordoñu II, King of León - husband first (possibly) of an unknown woman, second of Elvira Méndez, third of Aragonta González and fourth of Antsa Santxitz of Pamplona;

Fruela II, King of Asturias - husband first to Nunilo Jimena and (possibly) second of an unknown Muslim woman;

Infante Ramiro of Asturias - possible husband of Urraca;

Infante Gonzalo of Asturias - probably unmarried;

possibly Sancha Alfónsez - nothing is known about her;

possibly an unnamed daughter - nothing is known about her; and

possibly another unnamed daughter - nothing is known about her.

He was a member of a branch line of the Astur-Leonese Dynasty.

And was the King of Asturias between 866-900.

#alfonsu iii#king of asturias#middle ages#medieval spain#medieval europe#astur leonese dynasty#royals#royalty#monarchy#monarchies#asturian royalty#spanish royals#royal history#asturian history#spanish history#iberian history#european history#world history#history#reconquista#9th century#10th century#history with laura

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Alfonso VI (c. 1040/1041 – 1109)

Son of Fernando I of León and Queen Sancha, Alfonso VI became the ruler of a vast kingdom and far outstripped his predecessors in the extent of his sway. Yet few would have predicted this at his birth. A series of events between that moment and his triumph in 1072 shaped the king that was to rule a reunited León, Castile and Galicia, and from 1085 Toledo. This was a vital conquest, which recovered for Christian Spain one of the most important historical, strategic, and cultural centres of the peninsula, one that had been in the possession of the Muslims since the early 8th century. His name is also associated with Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar (El Cid), who was alternatively his enemy and indifferent supporter.

Alfonso VI probably grew up in the palace at León along with his brothers and sisters. He was either the third or fourth child; the sources give conflicting evidence, some suggesting that both sisters, Urraca and Elvira, were born before Alfonso. In either case, the first child was Urraca, and the second child was Sancho. Thus Alfonso VI was the second son, a position with which his father, also a second son, may have empathised. Given the later conflicts between the siblings, it is all too likely that the family dynamics were stormy from the beginning and split into various factions.

By his will, King Fernando divided his kingdom among his three sons: the eldest, Sancho, received Castile; the second, Alfonso, León; and from the latter the region of Galicia was carved off to create a separate state for García. Ferdinand’s two daughters each received cities: Elvira that of Toro and Urraca that of Zamora. In giving them these territories, he expressed his desire that they respect his wishes and abide by the split. However, soon after Fernando’s death, Sancho and Alfonso turned on García and defeated him.They then fought each other, the victorious Sancho reuniting their father’s possessions under his control in 1072. However, Sancho was killed that same year and the territories passed to Alfonso. García was imprisoned by Alfonso for life, leaving Alfonso in uncontested control of the reunited territories of their father. In recognition of this and his role as the preeminent Christian monarch on the peninsula, in 1077 Alfonso proclaimed himself “Emperor of all Spain”.

The twelfth-century Historia Silense famously describes Alfonso’s relationship with his elder sister, Urraca. It says that she looked after him in loco matris, in place of a mother, that she fed and dressed him, and that she loved him, as a sister, medulitus, deep in her heart, more than her other brothers. Although this relationship later became the subject of literary scandal, there is nothing here to suggest that it was more than a strong alliance formed in the midst of sibling rivalries.

Alfonso VI’s reign coincided in time with the origins and first development of the Crusading phenomenon, promoted by pope Urban II from 1095 onwards. This fact influenced the very nature and character of warfare against Muslims in the Iberian Peninsula. Alfonso VI stands out as a strong king whose interest was in law and order. He was a leader of his state during the Reconquista who was regarded by the Arabs as a very fierce and astute enemy, but also as a man who kept his word.

Alfonso showed a greater degree of interest than his predecessors in increasing the links between Iberia and the rest of Christian Europe. The past marital practices of the Iberian royalty had been to limit the choice of partners to the peninsula and Gascony, but Alfonso had French and Italian consorts, and arranged to marry his daughters to French princes and a king of Sicily. The influences from across the Pyrenees showed themselves in the introduction of the Romanesque style in art, the adoption of the Roman instead of the Mozarabic liturgy, the replacement of Visigothic by Carolingian script, and the energetic support that Alfonso gave to Cluniac monasticism, as well as in his reconstruction and safeguarding of the pilgrim road to Santiago.

According some chronicle, Alfonso VI had five wives and two concubines nobilissimas (most noble). The wives were Agnes of Aquitaine, Constance of Burgundy, Bertha, Isabel, and Beatrice of Aquitaine and the concubines Jimena Muñoz and Zaida of Seville. Zaida is also counted among the wives of Alfonso VI with the name Isabel and mother of his son Sancho Alfónsez. Some chroniclers from north of the Pyrenees report an earlier espousal, to a daughter of William the Conqueror, King of England and Duke of Normandy named Agatha.

The final stage of Alfonso’s reign was marked by a series of frustrating defeats at the hands of the Almoravid Berbers, who invaded Spain at the behest of Spanish Muslim leaders worried about growing Christian power, and a family crisis. Alfonso VI cunningly defeated a conspiracy of his sons-in-law Raymond and Henry of Burgundy who had plotted to divide the kingdom at his death.To turn them against each other, he gave Henry and his daughter Teresa the government of the County of Portugal, until then ruled by Raymond and his daughter Urraca, while the government of Raymond and Urraca was limited to Galicia. Accordingly, both cousins, instead of being allies, became rivals with conflicting interests; the succession pact went up in smoke and, henceforth, each would try to garner the favor of King Alfonso VI. Alfonso’s designated successor, his son Sancho, was slain after being routed at the Battle of Uclés in 1108, making Alfonso’s eldest legitimate daughter, the widowed Urraca as his heir. In order to strengthen her position as his successor, Alfonso began negotiations for her to marry her second cousin, Alfonso I of Aragon and Navarre, but died before the marriage could take place.

Sources:

Carlos de Ayala, ON THE ORIGINS OF CRUSADING IN THE PENINSULA: THE REIGN OF ALFONSO VI (1065-1109)

http://www.1066.co.nz/Mosaic%20DVD/stamford%20bridge/Alfonso%20VI%20of%20Leon%20and%20Castile.htm

http://homepages.rpi.edu/~holmes/Hobbies/Genealogy2/ps07/ps07_001.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfonso_VI_of_León_and_Castile

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bastard Kings and their families

This is series of posts are complementary to this historical parallels post from the JON SNOW FORTNIGHT EVENT, and it's purpouse to discover the lives of medieval bastard kings, and the following posts are meant to collect portraits of those kings and their close relatives.

In many cases it's difficult to find contemporary art of their period, so some of the portrayals are subsequent.

1) Tancred I of Sicily ( 1138 – 1194), son of Roger III of Apulia and Emma of Lecce; with his sons Roger III of Sicily (1175 –1193) and William III of Sicily (c. 1186 – c. 1198)

2) His wife, Sibylla of Acerra (1153–1205), mother of Roger III and William III

3) His brother-in-law, Richard of Acerra (d. 1196)

4)His father, Roger III of Apulia (1118 – 1148), son of Roger II of Sicily and his wife Elvira of Castile

5) His grandfather, Roger II of Sicily (1095– 1154), son of Roger I of Sicily and his wife Adelaide del Vasto

6) His uncle, William I of Sicily (1120/1121 – 1166), son of Roger II of Sicily and his wife Elvira of Castile

7) His cousin, William II of Sicily (1153 – 1189), son of William I of Sicily and his wife Joan of England

8) His aunt, Constance I of Sicily (1154–1198), daughter of Roger II of Sicily and his wife Beatrice of Rethel

9) His uncle, Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI (1165 – 1197), son of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I and his wife Beatrice I of Burgundy; and Constance I of Sicily's husband

10) His cousin, Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II (1194 – 1250), son of Constance I of Sicily and Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I

#jonsnowfortnightevent2023#asoiaf#a song of ice and fire#day 10#echoes of the past#historical parallels#medieval bastard kings#bastard kings and their families#tancred i of sicily#roger iii of sicily#william iii of sicily#sibylla of acerra#richard of acerra#roger iii of apulia#roger ii of sicily#william i of sicily#william ii of sicily#constance i of sicily#holy roman emperor henry vi#holy roman emperor frederick ii#canonjonsnow

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Zaida of Seville.

She was a refugee Muslim princess, formerly associated with the Abbadid dynasty, who became a mistress and then perhaps wife of king Alfonso VI of Castile.

With the fall of Seville to the Almoravids, she fled to the protection of Alfonso VI of Castile, becoming his mistress, converting to Roman Catholic Christianity and taking the baptismal name of Isabel.

She was the mother of Alfonso VI of Castile's only son, Sancho, who, though illegitimate, was named his father's heir but was killed in the Battle of Uclés of 1108 during his father's lifetime. It has been suggested that Alfonso's fourth wife, Isabel, was identical to Zaida, but this is still subject to scholarly debate, others making Queen Isabel distinct from the mistress or suggesting that Alfonso had two successive wives of this name, with Zaida being the second Queen Isabel. Alfonso's daughters Elvira and Sancha, were by Queen Isabel, and hence may have been Zaida's. Queen Isabel is last seen in May 1107.

#monarquia española#reyes de españa#reinas de españa#reina de castilla#isabel de sevilla#zaida of seville#spain in the middle ages#royal mistresses#la concubina del rey emperador#kindom of sapin#queen isabel

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

“…Inés Vanegas was only one of Catherine’s ladies at court who came to England and stayed. María de Salinas was the daughter of Martín de Salinas, a noble courtier to king Fernando, and Josefa Gonzales de Salas and, some suggest, perhaps related to the royal family. María was part of Catherine’s entourage from Spain but the details from 1501 to 1509 are not well known except that she attended Catherine at her coronation. Her family’s wealth and prestige made her an asset to Catherine’s court and she remained one of the queen’s closest and most loyal friends. Their friendship is well documented in the Tudor historical record, which include letters, payments and gifts, and reports of life at court from the Spanish ambassadors.

María was a very appealing bride, marrying William, eleventh lord Willoughby of Eresby, a baron and the largest landowner in Lincolnshire, on 5 June 1516 at Greenwich, probably in the chapel of the Observant Friars (Franciscans) where Catherine and Henry had married. By all accounts, María de Salinas moved fluidly from the Spanish court to the English. Her ease with the English customs and culture and family connections on the continent had important practical benefits. Her relative, Juan Adursa, a Castilian merchant in Flanders, worked with Juan Manuel, former advisor to Catherine’s brother-in-law, Archduke Philip of Burgundy, giving Catherine access to information about her sister, Juana.

Eustace Chapuys, the resident Spanish ambassador and a man privy to the secret, and not-so-secret activities at court, reports that the: few Spaniards who are still in her household prefer to be friends of the English, and neglect their duties as subjects of the King of Spain. The worst influence on the Queen is exercised by Doña María de Salinas, whom she loves more than any other mortal. Doña María has a relation of the name of Juan Adursa, who is a merchant in Flanders, and a friend of Juan Manuel. He hopes, through the protection of Juan Manuel, to be made treasurer of the Prince of Castile. By means of Juan Adursa and Doña María de Salinas, Juan Manuel is able to dictate to the Queen of England how she must behave. The consequence is that he can never make use, in his negotiations, of the influence which the Queen has in England, nor can he obtain through her the smallest advantage in any other respect.

The word “love” in the later Middle Ages can mean many things depending on context –courtly love, friendship, love of God, lord-vassal relationships, an apprentice for a master– and it could be shorthand for friendly affection. But Chapuys is clearly suggesting that the love has political implications, which further complicates an understanding of the significance of the relations of Catherine and her servants. But later events suggest a deep personal bond. María de Salinas had been forced to leave queen Catherine’s service in 1532 due to the politics of the divorce proceedings and Henry VIII’s marriage to Anne Boleyn, but she remained part of Catherine’s life. She defied Henry’s orders –never a wise thing to do even under the best of circumstances– and continued to correspond with the cast-off queen and sent her news of her daughter, Mary Tudor.

She and Charles Brandon, the king’s brother-in-law and close friend who was sent by Henry on numerous missions, had to impress upon Catherine the reality of her new marital state. In April 1533 Brandon had to tell her that she was no longer queen, and in December 1533 he was ordered to disband some of her servants and move her to the unhealthy home at Somersham. Catherine, defiant, locked herself in her room. María de Salinas told Chapuys that Catherine only relented when Charles admitted how he wished something dreadful would have happened on the road that would have made it impossible for him to carry out his duty to Henry. These are the actions of someone who is more than just a servant.

The depth of this relationship continued to the end. In 1535, when Catherina was seriously ill, María was denied permission to visit the former queen but once again, she defied Henry and traveled to Kimbolton Castle anyway. She was with Catherina when she died on January 7, 1536 and was the second mourner at Catherine’s funeral in February. Catherina had an equally close friendship with another Spanish noblewoman who served in her court. María de Rojas, daughter of Francesco de Rojas, count of Salinas, was one of Catherine’s closest and most intimate of the ladies at court, first in Spain and later in London. She appeared in queen Isabel’s household accounts in 1501 when she was paid 27,000 maravedís and received clothing in payment for service in 1500.

Her relationship with Catherina was as close as that of María de Salinas, a fact known best through her testimony in 1530 before the papal court concerning the divorce. She was asked to give a deposition concerning the consummation of the marriage between Catherina and Prince Arthur, who had died in April 1502, just a few months after their wedding. María de Rojas stated that to comfort the young widow, she had slept in bed with Catherina for the first few days after Arthur’s death: The same questions to be put to the wife of Juan Cuero once waiting maid to the said queen of England, and who is supposed to reside nowadays at Madrid; also to María de Rojas, wife of Don Álvaro de Mendoça, who used to sleep in the same bed with Her Most Serene Highness the Queen, after the death of prince Arthur, her first husband.

This is a remarkable glimpse into Catherina and into the sort of intimacy of life at court that was crucial to Catherina’s transition first from Spain to England and then from bride to widow. María de Rojas’s social rank and closeness to Catherina made her a desirable potential bride, first for the son of the earl of Derby, and later, the son of Elvira Manuel. Neither marriage took place and she returned to Spain around 1504 as señora de Santa Cruz de Campero where she married Álvaro de Mendoza y Guzman, son of Juan Hurtado de Mendoza and his second wife Leonor de Guzmán. It is possible that Maria de Rojas and María de Salinas were related and that when María de Rojas left England to marry, María de Salinas replaced her.

The intensely political life at court was not always conducive to such loyalty and devotion, and was often fraught with dangers. This is best exemplified by the relationship of Catherina and Elvira Manuel, guarda de las damas for Catherina, from 1499 to 1500, and her camarera mayor (chief household officer) from 1500 until 1507. Elvira Manuel de Villena Suárez de Figueroa was the daughter of Juan Manuel de Villena Fonseca, señor de Belmonte de Campos, and Aldonza Suárez de Figueroa. She married Manrique Manuel, Catherina’s chief mayordomo, and together the couple formed a key part of Catherina’s household in England.

Elvira made her first appearance in Catherina’s household in 1501, as Catherina prepared to move to England and on 10 March 1501 she received a payment of 100,000 maravedís: en cuenta de 216,666 marvedís de ovo de aver de su rraçcion e quitaçcion e ayuda de costa de vn año e ocho meses, en que seruio los años pasados de noventa e nueve e quinientos años, por el cargo de la guarda de sus damas. Their son, Iñigo, also came to England, as the master of Catherina’s pages. Elvira kept close contact with her brother, Juan Manuel, who was a servant of Philip of Burgundy.

In December 1505, Elvira was accused of promoting Philip’s interests at the expense of those of king Fernando, Catalina’s father, and Elvira was told to leave England. She departed on the pretext of visiting a doctor in Flanders about a disease that had already caused her to lose one of her eyes, but she knew that she would not be permitted to return. She had alienated not only king Henry but also Catherina. Elvira spent the rest of the life among Spanish exiles in Flanders.”

- Theresa M. Earenfight, “RAISING INFANTA CATALINA DE ARAGÓN TO BE CATHERINE, QUEEN OF ENGLAND.”

#katherine of aragon#maria de salinas#maria de rojas#elvira manuel#spanish#history#tudor#renaissance#ladies in waiting#theresa m earenfight

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Part III of the Arias Davila:

1. DIEGO ARIAS was born in Avila, Espana, and died 1466 in Segovia, Espana. According to the Tizon de la Nobleza, he married ELVIRA GONZALEZ,

Here we go again, rumors do not make for good genealogy or a written history. When I see the tag tavern maid I can't help but think about Juan Ponce de Leon's laison with a non existant Leonor Ponce de Leon who was also labeled to be a tavern maid.

"rumored to be a tavern maid", who was born in Madrid, Espana and a Jewish Conversa as well. Diego Arias, was created Senor de Alcobendas, Villaflor, Casasola, San Agustín, Pedrezuela y Villalba, and elevated to high office due to his intimate relationship with King Enrique IV, called "el Impotente", due to his well known homosexual proclivities. Diego Arias er hombre de extraccion humilde, de bajas inclinaciones, Judoo Converso segun el sentir popular, elevado por Enrique IV de la nada a las cumbres del poder y de la opulencia. Las "Coplas del Provincial" motejaban a Diego Arias de Judio en las conocidas estrofas: "Aguila, cruz y castillo, Dime, de dónde te viene, pues que tu pila capuz Nunca las tuvo ni las tiene? El aguila es de San Juan; El castillo el de Emaus, Y en la cruz pusiste a Jesus, Siendo yo el capitan"

Las estrofas se referían al blason de los Arias D'Avila compuesto de un aguila, castillo y cruz: en la parte superior derecha, una cruz colorada en campo blanco; en la superior izquierda, un aguila en campo blanco; y en la parte inferior del escudo, un castillo blanco en campo verde. Siendo príncipe don Enrique, Diego se estableció en Segovia y comenzo a ganarse el sustento cambiando especias de escaso valor y vendiendo a bajo precio otras de mayor estima, como pimienta, clavo y canela. Así recorría los pueblos castellanos congregando a los aldeanos al son de sus canticos moriscos. Así se gano de casa en casa las voluntades de los campesinos y obtuvo recursos suficientes para sus gastos. Con el favor de Juan Pacheco, se convirtio en recaudador de alcabalas y rentas del príncipe, y para ejercer el cargo en mejores condiciones de prontitud y seguridad, compro un caballo, flaco, de miserable traza y de bajo precio, que le permitia ponerse a salvo de las iras de los aldeanos. Por ello merecio el mote de "El Volador". Diego cometio un crimen horroroso y fue condenado a la pena capital de la que lo libro el Infante Enrique, príncipe de Asturias. Este, prendado de su dotes, no tuvo inconveniente en nombrarlo su secretario y le hizo tomar el apellido Arias. Al subir al trono pasando a ser el Rey Enrique IV de Castilla, Diego fue nombrado Contador Mayor de Castilla, cargo que desempeno por muchos anos, y desde el cual disponía a su antojo del reino. Se dice que "Diego Arias, acumulando atropello sobre atropello, aconsejaba al rey...que no hiciese caso de las querellas y enojosos llantos del necio vulgo y del insolente populacho, mientras tuviese dinero en abundancia; ni temiese las murmuraciones de los grandes, ni su adusto ceno mientras capitanease escuadrones satisfechos con el aumento de soldada..." Source: Jose de Herrera via E mail.

There are other sources full of rumors that would try to convince us that Diego Arias was a Jew.

By : Richard Gottheil <http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/contrib.jsp?cid=C120046&xid=A040718&artid=156&letter=D> Meyer Kayserling <http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/contrib.jsp?cid=C110107&xid=A040718&artid=156&letter=D>

Minister and confidant of King Henry IV. of Castile; born of Jewish. parents in Segovia; died in 1466. He, together with his family, embraced the Christian faith when Vincent Ferrer was preaching special sermons with a view to making converts. Drawn to the court of Juan II. of Castile by Alvaro de Luna, Davila, in conjunction with his former coreligionist Juan Pacheco, became both the farmer and the administrator of the royal taxes. In time he gained the confidence of the prodigal young king Henry to such a degree that the latter appointed him head of theroyal audit office or minister of finance ("contador mayor"). To win popular favor both he and his wife showed themselves very generous toward the Church; nevertheless he was always considered a Jew. The author of the "Coplas del Provincial" addressed to Davila the following malignant couplet: "A ti Diego Arias p . . . Que eres é fuiste Judio, E tienes gran señorio Contigo non me disputo." [Translation.] "Diego Arias, thou wretched hypocrite, A Jew thou wert and a Jew thou art. Great is the power that is thine; Hence to no dealings with thee I incline." Toward his coreligionists Davila's attitude was for a long time cold and forbidding; only later, when it became his duty to appoint supervisors of the revenues in most of the cities, did he have recourse to Maranos. Furthermore, despite repeated decrees of the Cortes to the contrary, he appointed Jews as tax-farmers. The chief administrator of the ducal tax-revenues at the time was D. Moses Ẓarfati; Rabbi Abraham and Joseph, Castellano were the farmers of the revenues in the bishopric of Roa from 1460 to 1462, and D. Moses of Briviesca the farmer of the revenues of S. Salvador de Oña in 1455. While the Jewish tax-farmers were very lenient, the Marano officials appointed by Davila showed themselves merciless, which drew upon them the enmity of the people to such an extent that D. Gomez Manrique, who possessed great influence, preferred charges against the minister, and in the "Advice" which he addressed to him ("Consejos à Diego Arias") he predicted for him a fate similar to that of Alvaro de Luna. With a king so frivolous and prodigal as Henry, Davila's situation was indeed very difficult and precarious; and he often found himself on the verge of being deposed. On one occasion when he represented to the king that the conditions urgently demanded a curtailment of expenditure, the king replied in an imperious tone "You speak as Diego Arias; I act as king." The castle Puñorostro, together with the villages and hamlets connected with it, which, after its acquisition by him, he turned into an entailed estate. Davila transferred to his oldest son, Pedro Davila, whom he married to D. Maria de Mendoza, niece of the first Duke del Infantado and a grandchild of Marquis de Santillana. Pedro filled the same position as his father had at the court of Henry IV., until he was overthrown through the intrigues of Alonso de Fonseca. Davila's second son, Juan Arias Davila (not "de Avila"), was Bishop of Segovia. Full of hatred against the Jews, he caused sixteen of them who had been accused of a ritual murder to be burned at the stake.

Bibliography: Enriquez del Castillo, Cronica de D. Enrique IV. xx.;

Amadorde los Rios, Hist. iii. 128 et seq., 168 et seq.;

Grätz, Gesch. viii. 327.G.

Read more: http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=156&letter=D#ixzz1BcTEW8Ot <http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=156&letter=D>

The Jewish Encyclopedia.

Ayes Sources:

Archivo: Archivo General de Simancas

Signatura: RGS,LEG,148012,254

Código de Referencia: ES.47161.AGS/1.2.1127//RGS,LEG,148012,254 Titulo Nombre atribuido: Pago de deudas a Diego de Madrid por Diego Arias Dávila. Fecha Creación: 1480-12-10 (Medina del Campo) Signatura Histórico: RGS,LEG,148012,254 Nombre de/l (los) productor/es: Cancillería. Registro del Sello de Corte Alcance y Contenido: Requerimiento con emplazamiento a Diego Arias de Avila [Dávila], hijo de Predrarias de Avila [Dávila], para que pague a Diego de Madrid, como heredero del dicho Pedrarias, cierto dinero y trigo que éste le quedó debiendo.-Consejo. Notas del Archivero: Información descriptiva tomada del asiento núm. 878 de la obra: 03

Archivo: Archivo General de Simancas

Signatura: RGS,LEG,148406,90

Código de Referencia: ES.47161.AGS/1.2.1123//RGS,LEG,148406,90 Titulo Nombre atribuido: Receptoría en pleito de Diego Arias Dávila y Diego de Tejada por ciertos bienes. Fecha Creación: 1484-06-19 (Valladolid) Signatura Histórico: RGS,LEG,148406,90 Nombre de/l (los) productor/es: Cancillería. Registro del Sello de Corte Alcance y Contenido: Receptoría en el pleito que tienen de una parte Diego Arias de Ávila [Dávila], y de la otra Diego de Tejada por ciertos bienes que se determinan.-Consejo.

Notas del Archivero: Información descriptiva tomada del asiento núm. 2898 de la obra: 03

Archivo: Archivo General de Simancas

Signatura: RGS,LEG,148406,105

Código de Referencia: ES.47161.AGS/1.2.1123//RGS,LEG,148406,105 Titulo Nombre atribuido: Incitativa a petición de Diego Arias Dávila, curador de Inés López Dávila. Fecha Creación: 1484-06-20 (Valladolid) Signatura Histórico: RGS,LEG,148406,105 Nombre de/l (los) productor/es: Cancillería. Registro del Sello de Corte Alcance y Contenido: Incitativa a petición del protonotario Diego Arias de Ávila [Dávila], curador de Inés López de Ávila [Dávila], para que le entreguen ciertos bienes la abuela de la menor y Toribio de Ávila, vecinos de Ávila.-Consejo.

Notas del Archivero: Información descriptiva tomada del asiento núm. 2903 de la obra: 03

Archivo: Archivo General de Simancas

Signatura: RGS,LEG,148409,160

Código de Referencia: ES.47161.AGS/1.2.1123//RGS,LEG,148409,160 Titulo Nombre atribuido: Amparo a unas casas en la ciudad de Segovia a Diego Arias de Ávila [Dávila]. Fecha Creación: 1484-09-01 (Córdoba) Signatura Histórico: RGS,LEG,148409,160 Nombre de/l (los) productor/es: Cancillería. Registro del Sello de Corte Alcance y Contenido: Amparo a unas casas en la ciudad de Segovia a Diego Arias de Ávila [Dávila], protonotario.-Consejo.

Notas del Archivero: Información descriptiva tomada del asiento núm. 3262 de la obra: 03

Archivo: Archivo General de Simancas

Signatura: RGS,LEG,148310,292

Código de Referencia: ES.47161.AGS/1.2.1124//RGS,LEG,148310,292 Titulo Nombre atribuido: Sentencia en pleito de Diego Arias Dávila sobre ciertos heredamientos. Fecha Creación: 1483-10-30 (Vitoria) Signatura Histórico: RGS,LEG,148310,292 Nombre de/l (los) productor/es: Cancillería. Registro del Sello de Corte Alcance y Contenido: Ejecutoria de una sentencia dada en el pleito que Diego Arias de Ávila [Dávila], 'cuya fué Torrejón de Velasco', sostuvo con los hijos de Gil de Vivero, ya difuntos, sobre los heredamientos de Pajares, Valverde y Posanco [Pozanco].-Consejo.

Notas del Archivero: Información descriptiva tomada del asiento núm. 1626 de la obra: 03

Archivo: Archivo General de Simancas

Signatura: RGS,LEG,148312,1

Código de Referencia: ES.47161.AGS/1.2.1124//RGS,LEG,148312,1 Titulo Nombre atribuido: Confirmación de juro al obispo de Segovia, Juan Arias Dávila, y su mesa obispal. Fecha Creación: 1483-12-15 (Vitoria) Nivel de Descripción: Unidad Documental Simple Signatura Histórico: RGS,LEG,148312,1 Nombre de/l (los) productor/es: Cancillería. Registro del Sello de Corte Alcance y Contenido: Confirmación a D. Juan Arias de Avila [Dávila], Obispo de Segovia, y a su mesa obispal de 4.000 maravedís de juro que posee por privilegio de Enrique IV.

Insertos: a) Albalá de Enrique IV, para que se asienten al contador mayor Diego Arias de Avila 4.000 maravedis de juro que en él renuncia D. Gómez Carrillo de Albornoz. 25 Noviembre 1456.

b) Renunncia y troque que el dicho contador hace a favor de la diócesis de Segovia y de su obispo D. Fernando del Orden. Medina del Campo 2 Noviembre 1459.

c)Carta de privilegio de Enrique IV confirmando al obispo y diócesis de Segovia los dichos maravedís. Medina del Campo 2 Noviembre 1459.-Contadores Mayores. Notas del Archivero: Información descriptiva tomada del asiento núm. 2040 de la obra: 03

Archivo: Sección Nobleza del Archivo Histórico Nacional

Signatura: OSUNA,C.138,D.101

Código de Referencia: ES.41168.SNAHN/17.3.13//OSUNA,C.138,D.101 Título: Cédula de Enrique IV por la que manda a Fernán Gómez de León, su recaudador de alcabalas en Cáceres, que pague a Diego Arias de Ávila 2.600 maravedíes. Fecha Creación: 1462-07-10 (Toledo (Toledo)) - (Toledo (Toledo)) Signatura Histórico: OSUNA,LEG.138,D.4 OSUNA,C.138,D.101 Estado de Conservación: Bueno Lengua/Escritura de la Documentación: EspañolCortesana Características Físicas y Requisitos Técnicos: Original Índices de Descripción: Alcabala Arias de Ávila, Diego Cáceres (Cáceres) Cédulas reales Enrique IV, rey de Castilla (1424-1474) Gómez de León, Fernán Libramientos Recaudadores de hacienda

Notas del Archivero: Descripción elaborada por Natividad Manzano Rubio

Archivo: Sección Nobleza del Archivo Histórico Nacional

Signatura: OSUNA,C.296,D.13-14 Código de Referencia: ES.41168.SNAHN/42.3.3//OSUNA,C.296,D.13-14 Titulo Nombre atribuido: Escritura de cambio entre Álvaro [López] de Zúñiga [Guzmán, I] conde de Plasencia con Diego Arias de Ávila, por la cual el primero da unas casas en la ciudad de Segovia a cambio de unos molinos en el río Voltoya. Fecha Creación: 1457-10-23 (Segovia (Segovia)) Signatura Histórico: OSUNA,LEG.296,D.2;OSUNA,LEG.296-1(10) OSUNA,C.296,D.13-14 Nombre de/l (los) productor/es: Ducado de Béjar Alcance y Contenido: Contiene:

-Documento 14: correspondencia remitida por Francisco Díez de Velasco al capitán Juan de Capilla sobre compraventa de lana. Dada en Béjar (Salamanca) a 8 de abril de 1639. Estado de Conservación: Bueno Lengua/Escritura de la Documentación: Español. Cortesana y Humanística. Notas del Archivero: Rus Huerta Rubio

Archivo: Sección Nobleza del Archivo Histórico Nacional

Signatura: OSUNA,C.96,D.45-47

Código de Referencia: ES.41168.SNAHN/14.2.6//OSUNA,C.96,D.45-47 Título: Escritura de compraventa, por juro de heredad, otorgada por Fernando de Ribadeneira, vasallo del rey y de su Consejo, a favor del rey Enrique IV, y en su nombre a su contador Diego Arias de Ávila, de los lugares de Langayo, Piñel de Yuso y San Mames (Valladolid). Fecha Creación: 1458-05-24 (Medina del Campo (Valladolid)) - 1837-10-02 (Medina del Campo (Valladolid)) Signatura Histórico: OSUNA,LEG.96,N.15;OSUNA,C.96,D.15;OSUNA,C.1,N.36 OSUNA,C.96,D.45-47 Alcance y Contenido: Documento 45: Original en pergamino. Medina del Campo (Valladolid), 1458, mayo, 24.

Documento 46: Traslado. Madrid, 1837, octubre, 2.

Documento 47: Copia simple, sin fecha. Estado de Conservación: Bueno Lengua/Escritura de la Documentación: EspañolGotica y humanística Características Físicas y Requisitos Técnicos: Original, traslado y copia Índices de Descripción: Arias de Ávila, Diego Compraventas Consejeros reales Contadores de hacienda Enrique IV, rey de Castilla (1424-1474) Juros Langayo (Valladolid) Piñel de Abajo (Valladolid) Ribadeneira, Fernando de San Mamés (Valladolid) Notas del Archivero: Descripción elaborada por Natividad Manzano Rubio

Archivo: Sección Nobleza del Archivo Histórico Nacional

Signatura: OSUNA,C.97,D.6-8

Código de Referencia: ES.41168.SNAHN/14.3.3//OSUNA,C.97,D.6-8 Título: Escrituras de partición de los bienes de Diego Arias Ávila, contador mayor del rey y de su Consejo Real, hecha entre sus hijos Juan Arias Ávila, [obispo de Segovia], y su hermana Isabel Arias, ésta última con autorización de su marido, Gómez González de la Hoz, regidor de Segovia. Fecha Creación: 1466-01-15 (Segovia (Segovia)) - 1837-10-09 (Segovia (Segovia)) Signatura Histórico: OSUNA,C.97,D.2;OSUNA,LEG.97,N.2a-c OSUNA,C.97,D.6-8 Alcance y Contenido: Contiene:

-Documento 6: traslado. Valladolid, a 23 de enero de 1473.

-Documento 8: traslado realizado tras la ley aclaratoria de señoríos, por la cual deben presentarse en los juzgados todos los títulos de propiedad, lo cual hace el [XI] duque de Osuna, [Pedro de Alcántara Téllez-Girón], para demostrar la procedencia o fundación de algunos de sus señoríos, como es el caso de Quintanillas de Yuso y de Suso (Valladolid). Madrid, a 9 de octubre de 1837. Estado de Conservación: Bueno Lengua/Escritura de la Documentación: Españolcortesana y humanística Características Físicas y Requisitos Técnicos: traslados Índices de Descripción: Arias de Ávila, Diego Arias de Ávila, Juan, obispo de Segovia (1461-1497) Arias, Isabel Consejeros reales Consejo Real Contadores de hacienda Estados señoriales González de la Hoz, Gómez, regidor de Segovia Inventarios de bienes Leyes Madrid (Madrid) Obispado de Segovia Quintanilla de Abajo (Valladolid) Quintanilla de Arriba (Valladolid) Segovia (Segovia) Testamentarias Títulos de propiedad Valladolid (Valladolid)

Notas del Archivero: Descripción elaborada por Isabel Ralero Rojas

Archivo: Sección Nobleza del Archivo Histórico Nacional

Signatura: OSUNA,C.97,D.9-11