#elderwomen

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Festival - Developer Log 9, 11/11/2024

Good evening!

So much has happened since my last checkin, that I don’t even know where to begin.

Just like in the last update, I’ve done a lot of work optimizing the code in Unreal, which wound up being hugely critical because I had to manually update the DialogueTree plugin I’ve been using due to a bug in the previous release. It was not an easy process, but I got it taken care of, and I’ve been making steady progress ever since.

Five major changes from last time worth noting:

First of all, I’ve been tweaking the character fullbody sprites I had in the previous iteration, editing their size, proportions, and even their expressions. Early feedback I have gotten from friends has made me confident that this was a superb and necessary move, as the sprites really add a lot of personality to the conversations.

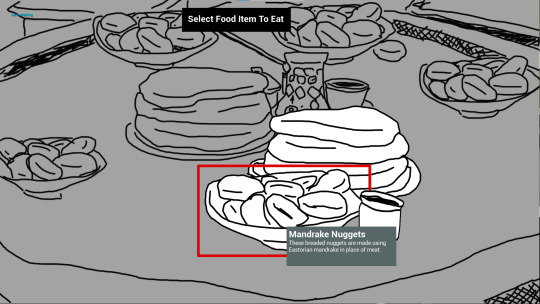

Secondly, I made rough draft drawings of the food scenes that I had incorporated into the game the for the last devlog as a prototype. As you can see below, the food scenes feature little plates of food that you can eat from which progress the conversation you are currently having with NPCs, and each food item even includes flavor-text describing the item you are eating.

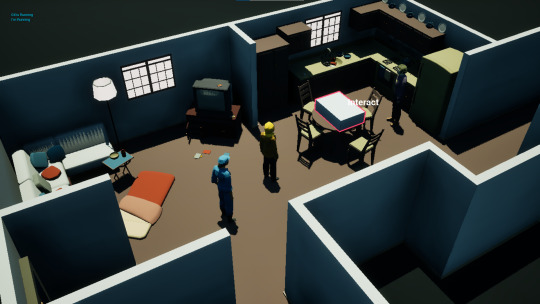

Thirdly, I created a character model for Roxane, another major character of the story (seen below). Over the course of writing the script, she grew from a minor character to one of its most crucial, as she has been swindled by the villain of the story, Helvan Dynicus, into letting him stay at her home, and it is up to Nishma and the Elderwomen of Hemmingward to try to save her from him.

Fourthly, Morgan and I have been fleshing out the interior environments for the game. I was working on the temple interior, while Morgan modeled a litany of props for the interior of Roxane's house, pictured below:

Fifthly, and lastly, I successfuly exported and uploaded the first build for the game. It took me some time to get it to a point I am happy with, especially since it only includes the first act out of three, but now people can actually check out what I have been working on for the past year and change. I’m really happy to be at this point, even if I still have a lot of work ahead of me.

I will upload the link to the game in a separate post. Partly because I want it to be a standalone post, and partly because I may re-export and re-upload the build in order to make some last minute changes. But otherwise, I hope to have a link for it posted here in the next couple days.

I may not be able to get another devlog done until after the semester ends, but I will do my best to document everything else I have gotten done by then. Hopefully I will have a full game to show, even if it is incredibly rough around the edges.

At this point, the important thing is to have *a* game to show off in full.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

https://youtu.be/qwD5ePvKaUY. Aquí el link del vídeo Chino divertido.... aquí hago la parte 1.... Anímate!!!!..... Muy fácil, busca tu motivación y muévete!!! 🇬🇧🇬🇧🇬🇧 Here is the link to the funny Chinese video .... here I do part 1 .... Cheer up !!!! ..... Very easy, find your motivation and move !!! #keepsafeandhealthy#fiftyoneyearsstrong#cincuentayunaños#cincuentañerasdeportistas#figurerobics#jungdayeon#aerobic#aerobicos#funnyworkoutvideos#iloveworkouts#elderwomen# (en Khok Kloi, Phangnga, Thailand) https://www.instagram.com/p/CB48wEohASc/?igshid=6ihrr6grw28n

#keepsafeandhealthy#fiftyoneyearsstrong#cincuentayunaños#cincuentañerasdeportistas#figurerobics#jungdayeon#aerobic#aerobicos#funnyworkoutvideos#iloveworkouts#elderwomen

0 notes

Photo

fot. Szymon Konieczny © Colorblind 2020 #elderwomen #people #streetphotography #streetphoto_bw #streetphoto #streetphoto_bnw #streetphotographers #warszawa #poland #poland🇵🇱 #zfaanima #colorblindartpl (w: Wawer, Warszawa, Poland) https://www.instagram.com/p/B9wnYJQptbc/?igshid=17oid6tamim0n

#elderwomen#people#streetphotography#streetphoto_bw#streetphoto#streetphoto_bnw#streetphotographers#warszawa#poland#poland🇵🇱#zfaanima#colorblindartpl

0 notes

Text

आखिर क्यों पुरुषों को भाती है अपने से अधिक उम्र की महिलाएं?

चैतन्य भारत न्यूज किसी के प्रति आकर्षित होना आम बात है, लेकिन कई बार पुरुष अपने से बड़ी उम्र की महिलाओं के प्रति आकर्षित हो जाते हैं। पुरुषों में यह बात देखी गई है कि वह अक्सर ही अपने से बड़ी उम्र की औरतों के प्रति एक अजीब-सा आकर्षण महसूस करते हैं। आइए जानते हैं कि आखिर क्यों पुरुष अपने से बड़ी उम्र की महिलाओं की तरफ आकर्षित होते हैं। (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || ).push({}); हर बात को बेहतर समझना

अधिक उम्र की महिलाएं चीजों को ब��हतर तरीके से समझती हैं। दरअसल उन्होनें आपसे ज्यादा दुनिया देखी होती है। वह खराब स्थिति में लड़ाई-झगड़े के बगैर शांति से बातचीत करना पसंद करती हैं, क्योंकि वह जानती हैं कि बातचीत ही हर समस्या का हल है। रिश्ते को मजबूत बनाती हैं

अधिक उम्र की महिलाएं रिश्तों को काफी गंभीरता से लेती हैं। उनके लिए रिश्ता उनकी पहली प्राथमिकता होता है, क्योंकि उन्हें पता होता है कि इस दुनिया में रिश्ते से बड़ी कोई चीज नहीं है। यही वजह है कि पुरुष बहुत जल्द अपने से बड़ी उम्र की महिलाओं के प्रति आकर्षित हो जाते हैं। आत्मविश्वास होना

अधिक उम्र की महिलाएं बेहद आत्मविश्वासी होती हैं। वह अपने आत्मविश्वास की बदौलत सब कुछ पाने की हिम्मत रखती हैं। पार्टनर के साथ खुद को भी समझना

बड़ी उम्र की महिलाएं अपने पार्टनर के साथ अपने आप को बहुत अच्छी तरह समझती हैं। उनकी अपनी जीवनशैली होती है और वे जानती हैं उन्हें अपनी लाइफ से क्या अपेक्षाएं हैं। ये भी पढ़े... पार्टनर के करीब आने से पहले खुद से पूछे ये सवाल, मजबूत होगा रिश्ता ये हैं वो खास बातें जिन्हें महिलाएं अपने पार्टनर से छिपाती हैं शादी के बाद पार्टनर की इन हरकतों की वजह से बिखर जाता है पति-पत्नी का रिश्ता Read the full article

#elderwomen#husbandandwiferelationship#menandwomenrelationship#relationship#relationshipelderwomen#relationshipgoals#relationshipnews#relationshiptips#relationshiptipsforladies#relationshiptipsinhindi#whymenslikeelderwomen#अधिकउम्रकीमहिलाएं#अधिकउम्रमहिलाओंकीतरफआकर्षितहोनेकीवजह#आकर्षितहोना#पुरुषोंकोक्योंपसंदआतीहैअधिकउम्रकीमहिलाएं#बड़ीउम्रकीमहिलाओंकीतरफआकर्षितहोना#रिलेशनशिप#रिलेशनशिपआर्टिकल#रिलेशनशिपकीकड़वीसच्चाई#रिलेशनशिपकीसमास्याएं#रिलेशनशिपकेटिप्स#रिलेशनशिपटिप्सइनहिंदी#रिलेशनशिपन्यूज#रिलेशनशिपपतिपत्नी

0 notes

Photo

Around 75% of women diagnosed with breast cancer over 50 years of age.

0 notes

Text

My Tolkien showerthought of the day is that making waybread was an art taught by Oromë to the Three Elderwomen of the Elves in prep for the Great Journey

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

Ancestral Ainu Remains Returned by Tokyo University by Noah Oskow

A long fight by Japan's indigenous Ainu results in a hard-won victory - but much more remains to be done. Resting Once Again Amongst Their People

On August 22nd, a Kamuinomi – an Ainu ceremony meant to celebrate the return of spirts to the realm of the gods – was held in Urahoro, in eastern Hokkaido. The sacrament��s purpose was that of welcoming back six sets of indigenous remains, taken long ago by Japanese researchers based out of the famed Tokyo University. The researchers first removed the Ainu remains from their gravesites in 1889, in the early Meiji Era; later, others returned in 1965, in the post-war era, for more.

The group receiving the ancestral remains was the Raporo Ainu Nation, the local Urahoro indigenous organization. For them, it was a day of quiet celebration – the culmination of a series of victories in their quest to reclaim stolen Ainu remains.

Raporo Ainu Nation had previously brought court cases against Hokkaido and Sapporo Medical Universities, both of which housed innumerable Ainu skeletons; all have now been returned to their homelands. Tokyo University, despite earlier protestations, was now also acquiescing to similar demands.

Six wooden boxes were laid out in front of a large freshly dug grave. Besides the waiting earth sat the Ainu delegation, bedecked in traditional clothing. They chanted in the Ainu tongue – one unrelated to the Japanese language which otherwise surrounded them. (Unlike the languages of the native Ryukuans, Ainu is not a Japonic language.) Libations of sake were offered to the kamuy, the spirits. Then, the remains were finally reinterred in the land from which they had so long ago been taken.

The Abduction of their Ancestors

The impetus for the veritable grave plundering of Ainu bones was ostensibly scientific: the desire by Japanese researchers to learn more about the physical and, later, genetic make-up of the indigenous ethnic minorities native to Japan’s northern borders. Indeed, at the time of the first unearthing, Hokkaido (and the native Ainu people along with them) had only recently been fully incorporated into Japan.

Previous to the Meiji Restoration in 1868, Hokkaido wasn’t even “Hokkaido;” rather, it was Ezo, a frontier borderland peopled by those the Japanese considered “barbarians.” A relatively small Japanese settler colony ruled by the Matsumae clan existed on the southern tip of Oshima Penninsula, which regulated trade with the Ainu and oversaw Japanese financial control of the island.

Sadly, this led to the entire field of Ainu Studies being essentially founded on grave robbery.

Previous to Japanese encroachment and eventual control, the Ainu people lived in villages scattered across Ezo, Sakhalin Island, and the Kurils. While they had a hunter-gatherer lifestyle that appeared uncivilized to the Japanese, Ainu society was in fact more complex than most interlopers perceived.

Beyond their advanced hunting and fishing techniques, the Ainu were also part of a diverse and expansive trade network that stretched from Hokkaido in the south, to Kamchatka in the far north. Ainu traders rode in dugout canoes to the Asian mainland, where they traded with the indigenous peoples of the Amur river basin. Sakhalin Ainu even made war with the Mongol-controlled Yuan dynasty of China, and later engaged in tributary trading with the Ming and Yuan dynasties.

High-quality silk brocades given to Ainu chieftains by the Chinese became prized goods for trade with encroaching Japanese from the south. It was access to these Chinese goods and Ainu-hunted pelts, furs, painted Sakhalin beads, and live falcons that made Japanese samurai desirous towards control of Ainu trade. Japanese trading pressure; exploitative and often coerced use of Ainu labor in Japanese fisheries; the ravages of newly introduced diseases; all these brought irreparable damage to the Ainu environment and society.

The Myth of a Naturally Doomed People

In 1889, in the midst of Japan’s headlong rush towards modernity, the Japanese government passed the Hokkaido Former Aborigines Protection Act. The Ainu were now officially considered Japanese. In practice, this meant they were subject to forced cultural assimilation that further disrupted their society and lead, ironically, to mass discrimination.

The Ainu’s were now a periphery people scheduled to be made “Japanese,” their “aboriginal” status to be forgotten as quickly as possible. In light of the notion that the Ainu were now a “disappearing tribe,” Japanese researchers became intent on taking as many artifacts of the Ainu’s material culture as possible before the earth swallowed them up. This is part of what resulted in the initial untombing of the Ainu remains just recently returned by Tokyo University.

In these inaugural years of the field of ‘Ainu Studies” (アイヌ学), previously held ideas about Ainu “barbarians” were melded with the emerging scientific field of evolution, leading Japanese researchers to make various claims about Ainu inferiority to “more evolved” Japanese society. Researchers, although often empathetic towards the plight of the impoverished Ainu, believed the only way to “save” the object of their research was to assimilate them out of existence. As Ainu ties to their craft traditions waned and the people themselves were assumed to be on the brink of annihilation, researchers felt the need to collect and document as much as possible.

A Dark Legacy for Ainu Studies

The Hokkaido Museum of Northern Peoples (Hoppo Minzoku Hakubutsukan) exhibits about the culture of Ainu native people and other northern peoples of the world.

Sadly, this led to the entire field of Ainu Studies being essentially founded on grave robbery. In both 1864 and 1865, mere years before the fall of the Tokugawa dynasty, the British consul in Hakodate led a group of foreigners interested in uncovering the mystery of the Ainu’s “Caucasian” features to secretly raid Ainu gravesites. When the story broke, it became a major scandal (even resulting in the firing of the consul).

Yet subsequent Japanese researchers continued to seek out Ainu bones for well over a century. Sometimes this was done with the understanding of local Ainu. (As often happened with Ainu crafts, money was possibly exchanged). Other times, however, researchers hoping to learn more about this “disappearing tribe” engaged in acts that very much resembled the previous British consul’s.

Ancestors Unearthed

Most infamous of the grave robbers was Hokkaido University Professor Kodama Sakuzaemon, who lead various state-sanctioned raids into local boneyards throughout the 1920s to 1970s – all against Ainu protests. Sometimes police were called in to help hold off Ainu from physically preventing the unearthing of their ancestors. As is recalled in the book Beyond Ainu Studies, a 1930’s bone-collecting expedition resulted in…

…the entire village police force [being] enlisted to assist Kodama’s team and when three or four elderwomen threw their bodies over their ancestors’ grave sites they were unceremoniously removed by attending officers. The end result of decades of university researchers stealing thousands of ancestral remains was an Ainu populace who often distrusted and felt anger towards those Japanese academics and scientists who, ostensibly, wanted to understand the Ainu. Especially egregious to the Ainu was the fact that, within their tradition, bodies are to buried whole in order to maintain a tie to the spirit.

Painful Memories

Our land, Ainu Mosir, had been invaded, our language stripped, our ancestral remains robbed, the blood of living Ainu taken, and even our few remaining utensils carried away. At this rate, what would happen to the Ainu people? For Kayano Shigeru (萱野 茂, 1926 – 2006), the first Ainu in Japanese parliament and a major voice for indigenous rights, the spiriting away of Ainu skeletons and artifacts by mainland researchers was a source of much shame. In his famous memoir, Our Land Was A Forest, Kayano recalled returning home to find treasured artifacts missing; his impoverished father had sold them away to researchers.

In those days I despised scholars of Ainu culture from the bottom of my heart. They used to visit my father for his extensive knowledge of the Ainu. I often railed at them and, accusing them of behavior as rude as that of waking a sleeping child, ordered them never to return. Professor K. [likely Kodama] of Hokkaido University was one at whom I snarled many times… They dug up our sacred tombs and carried away ancestral bones. Under the pretext of research, they took blood from villagers and, in order to examine how hairy we were, rolled up our sleeves, then lowered our collars to check our backs… It was this same anger and desire to recover the Ainu culture that lead Kayano to become such a major voice in the question for indigenous rights in Japan.

Seeing such self-centered conduct by shamo [Japanese] scholars, I asked myself whether matters should be left as they were: Our land, Ainu Mosir, had been invaded, our language stripped, our ancestral remains robbed, the blood of living Ainu taken, and even our few remaining utensils carried away. At this rate, what would happen to the Ainu people? What would happen to Ainu culture? From that moment on, I vowed to take them back.

The Fight to Reclaim the Ancestors

It was with the same spirit of cultural recovery that Ainu groups from around Hokkaido have set out to gain the return of their ancestor’s remains. In 2008, after centuries of denial and erasure, the Japanese government suddenly announced that the Ainu were to be legally considered the indigenous people of the north. Although by this point there remained only around 25,000 self-declared Ainu with only a few elderly native speakers still living, this signaled a huge victory for Ainu rights. In 2013, the Ainu council of Kineusu used their new indigenous status as a basis for suing Hokkaido University for the return of uninterred Ainu bones.

More lawsuits followed. Slowly, the ancestral remains and funerary artifacts sitting in collections and in storage across universities in Japan began to be returned. Hokkaido University, home to more Ainu remains than any other facility in Japan, played a major role in these skeletal repatriations. In July, Hokkaido opened the Symbolic Space for Ethnic Harmony – a “national center for the revival and development of Ainu culture.” The center is to host the National Ainu Museum and National Ainu Park. Importantly, it also has a space to carefully store Ainu remains. Still, the Symbolic Space itself has become controversial with Ainu, with some hoping for the return of remains more directly to Ainu communities.

The Way Forward

The return of the ancestral remains by Tokyo University on Saturday comes amidst an interesting time for the Ainu community. Recognition of the Ainu and their culture is one the rise worldwide, they finally have recognition by the Japanese government, and cultural revival movements are gaining steam. Young Ainu are engaged in reconnecting with their heritage, learning their language, and sharing their culture with others. Hokkaido schools will soon have textbooks that make multiple references to Ainu history. The field of Ainu Studies has evolved, now placing more primacy on the perceptions of the Ainu themselves and welcoming more Ainu scholars.

Yet still, Ainu face discrimination and erasure. A national survey from only four years ago revealed that a huge 74% of Japanese people had never been exposed to Ainu culture or people. The now-delayed 2020 Tokyo Olympics suddenly axed an Ainu ceremony planned for the opening ceremonies. Progress is being made, but it’s not always enough.

Yet, on Saturday, as the burial of six sets of remains in Urahoro marked the complete return of a total of 103 such Ainu once held at Tokyo University, Raporo Ainu Nation honorary president Masaki Sashima found himself becoming emotional.

この瞬間を迎えられて感無量です。遺骨には『今まで待たせて申し訳ありませんでした。静かに眠ってください』とお祈りしました。I’m overcome with feeling having reached this moment. I prayed to the remains of the deceased, saying, “I’m greatly sorry for having made you wait so long. Please rest in peace.”

The earth of the Ainu Moshir, the Ainu homeland, once again embraced the ancestral remains, welcoming them home.

Sources (08月22日). 東大返還アイヌの人の遺骨を埋葬. NHK News Web.

Kayano, S. (1994). Our Land Was A Forest : An Ainu Memoir. Routledge.

Hudson, M.J., Lewallen, A., & Watson, M.K. (2014). Beyond Ainu Studies: Changing Academic and Public Perspectives. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Walker, B. (2001). The Conquest of Ainu Lands: Ecology and Culture in Japanese Expansion,1590-1800. University of California Press.

Kimura, K. (2015, July 25). Japan’s indigenous Ainu sue to bring their ancestors’ bones back home. The Japan Times.

#Ainu#Ainu Moshiri#Ancestors#Hokkaido#Tokyo#Tokyo University#Japan#colonialism#colonial violence#genocide#grave robbing#racism#institutional racism

378 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This beautiful lady used to come to the farm with her daughter. They would walk thru the flowers picking a beautiful boquet every week. This particular week she looked radiant. . . . #flowers #flowerstagram #deepseeded #deepseededfarm #eldersister #elderwomen #KelleyBarrettPhotography #garden #communitysustainedagriculture #communitysustainableagriculture

#deepseeded#flowers#elderwomen#flowerstagram#eldersister#deepseededfarm#communitysustainableagriculture#garden#kelleybarrettphotography#communitysustainedagriculture

0 notes

Text

The Festival - Developer Log 6, 6/06/2024

Hello!

Following up from my last devlog a couple weeks back, one major thing I want to share today is the current outline for The Festival’s pilot quest, Hemmingward.

The first draft for this script was completed in Fall 2023, and in the past term Bekir reviewed the script in its entirety, raising several issues that I needed to address. The second draft of the script is currently in progress, though I don’t have an estimate on when exactly it will be completed.

What we do have completed is an outline of the second draft, which I am going to share with you all today. This outline is still subject to change, but this is the current version that I am working to flesh out and implement. The script is divided into three ‘acts’, primarily to make the overall script easier to read and work with.

This story is heavily based on the Bosnian film Snow/Snijeg (2008), by director Aida Begić. The central premise of a village having lost all its men and dealing with a visitor who, unbeknownst to them, was complicit in the loss of their men is taken straight from Snow.

I will detail the outline of the quest below the cut.

Hemmingward

Log Line

In pursuit of a secret recipe, Nishma is roped into solving a decade-long mystery, and putting a village’s trauma to rest.

Act I

Nishma and Gil to the hamlet of Hemmingward to obtain the recipe for Mandrake Meat, a plant-based substance that closely resembles red meat. The elderwomen of the village have offered to take part in Nishma’s festival, and they have invited her to their town to discuss their involvement.

However, she is not the only one who wants the recipe – a businessman named Helvan Dynicus is trying to buy it off the villagers.

Nishma and Gil run into Helvan shortly after they arrive in town. The girls sense there’s something off about the man, who attempts to rope Nishma into his scheme. After a brief exchange, Nishma and Gil continue on their way to meet with the elderwomen – Elders Margot, Camaltha, and Eurydice.

The duo sit down to have lunch with the elderwomen, who share the history of their town and their mandrake meat cuisine over a pleasant meal. However, things get complicated once the subject of Helvan Dynicus comes up. While Elder Margot is fully onboard with joining the festival, Elders Camaltha and Eurydice are reluctant to commit without first dealing with this mysterious interloper. Soon, they reveal to Nishma and Gil that they suspect Helvan of being a former military officer who came to Hemmingward years ago and rounded up all of the village's men.

When presented with this information, Nishma will be asked to investigate Helvan Dynicus’s true identity, using her connections to the Citizens Militia (the new ruling government of Eastoria) to find out if this man is indeed the same one as the officer who came 15 years prior.

In the full game, Nishma will have the option of accepting or refusing this quest. For this vertical slice, she will accept the elderwomen’s request, and she and Gil will set out to research what they can about this man (though Gil informs Nishma that they are way over their heads in accepting this responsibility).

After this inciting conversation, Nishma and Gil will place a call with Quartermaster Holmes, a Citizens Militia officer who is helping Nishma with logistical details for the festival.

Holmes is concerned by Nishma trying to carry out this investigation on her own, but nonetheless refers her to the Citizens Militia’s military archives as the place where she will most likely get an answer. With their new objective established, Nishma and Gil leave the village of Hemmingward to start their investigation.

Act II

We fast forward in time a few days. Nishma and Gil visit the military archives to begin their search for any paperwork or evidence pertaining to Helvan Dynicus and the village of Hemmingward. This section of gameplay will be mostly centered on reading documents. I would compare it to some of the side quests/minigames from Pentiment, where the protagonist takes time out of their day to learn some new information about both the world, and the quest at hand.

Eventually, Nishma will find a relevant paper detailing what happened at Hemmingward, but it’s vague in its details and Helvan’s name isn’t listed anywhere. Convinced that the name Helvan Dynicus must be an alias, and that he could still be one of the named officers listed, Nishma tries to gain access to a different part of the archive that could hold information on officer dossiers. However, she and Gil must convince an on-duty guard to let her into that part of the archive. Currently I have three solutions to this conundrum. Nishma can either:

Bribe the guard

Fetch an item of significance for the guard

Resolve an ideological dispute between him and someone else

Once one of these is completed, the guard will allow Nishma access to the other portion of the archive. Once there, Nishma will eventually find the dossier of one of the officers listed as being present at Hemmingward, and realize that he is indeed the same man as Helvan Dynicus. She and Gil will then head to Quartermaster Holmes to present their findings.

At this meeting, Nishma, Gil, and Holmes will discuss the logistics of apprehending Helvan, concluding that they have to work with the elderwomen of Hemmingward to arrest him. After this meeting, Nishma and Gil will call the elderwomen, and arrange to set another meeting as soon as possible.

Act III

Soon after their phone call, Nishma and Gil travel to Hemmingward with two other Citizens Militia soldiers. They meet once more with the elderwomen, along with Taemahra, another resident of the village who has had to deal with Helvan’s interference.

The elderwomen say that Helvan has been out of town for the past couple days, but that they can call him back with a false promise to negotiate a deal for their mandrake meat recipe. There is some conflict over what to do with Helvan once is in custody, with the elderwomen wanting to carry out justice for their men on their terms, and Gil wanting to bring Helvan in to stand trial for his actions. Nishma is able to persuade the elderwomen to go along with the plan to bring Helvan to trial for the time being, though they’re not fully convinced it’s the best idea.

The following day, Helvan returns to town to meet with the elderwomen at their old town hall to sign a deal with them, at which point Gil and the other soldiers spring their trap. They have Helvan in handcuffs, but Helvan manages to catch everyone off-guard by promising to show the elderwomen where their men are buried. At this point the elderwomen demand to have Helvan be handed over, but Gil refuses, and squabbles with elder Camaltha. Nishma is unable to intervene before Helvan throws down a smoke bomb to throw everyone off and cover his escape.

He doesn’t get far though before he runs outside and is shot in the leg by Taemahra, who was standing guard with her own rifle. Injured, Helvan succumbs to the ground, and is taken back inside the town hall by Gil and the soldiers. They and the elderwomen tend to Helvan’s wound while having him confined.

We fast forward a few hours. A crowd has gathered outside the town hall due to the commotion. The two soldiers previously accompanying Gil are posted outside to keep people at bay.

Once Helvan recovers enough to ‘talk’, the elderwomen press him for answers, with Gil and Nishma also asking him questions. It is here that Helvan’s polite façade from earlier disappears, and we see a truly rotten man who casts away all blame for what he did to the village’s men.

After a hostile conversation, the elderwomen agree they will execute Helvan, and go outside to speak with Taemahra about being their executioner. Gil runs after them, leaving Nishma alone with Helvan.

Helvan tries to appeal to Nishma’s kindness and desire to hold the festival (which was informed about in Act I in the first conversation) in an attempt to bribe her to let him survive. He explains he would rather stand trial with the Citizens Militia, believing he can plausibly explain his innocence. Nishma can make multiple choices here:

Accept the bribe and try to talk the elderwomen into letting him live

Reject the bribe but try to convince the elderwomen that it’s important for Helvan to be tried in a court of law

Reject the bribe and let the elderwomen kill him, convincing Gil that she and the others ought to step aside

Accept the bribe, but let the elderwomen kill him anyways

If Helvan is allowed to be killed, Taemahra and the elderwomen go back inside, with Taemahra executing Helvan with her rifle.

If Helvan is allowed to live, he will be escorted out by the two other soldiers. His expression will either be smug or worried, depending on if Nishma accepted the bribe or rejected it.

While Nishma can reject the bribe but still have Helvan stand trial, it’s presented in a different way from than if she agrees to go along with his plan. Nishma can point out to Helvan that it’s better he stand trial, not out of a sense of mercy, but because he must answer for any other crimes he may have committed. She also tries to argue – to him and to the elderwomen – that it’s important to use him to set a precedent for how other war criminals should be prosecuted by the Citizens Militia, a task they’ve historically had mixed success with as they’ve tried to present their new government as legitimate.

Ultimately, I wish to present both options – letting the elderwomen execute him, or letting him stand trial – as valid choices, where both have their strengths, and where the elderwomen are not judged for wanting to carry out revenge against the man who grievously harmed their village.

=====================================================

Thank you for reading this far! I would love to hear any feedback or critiques y’all may have, and I am glad I can finally share this outline with you all.

For my next post, I will try to do a character bio for Gil Yurez.

Lastly, a special thank you to Bekir for all his help in suggesting revisions and corrections for this quest.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

7 Senior Actresses Who Were Hot As Hell When They Were Young - Seeing older women dating younger men is no surprise, especially when you take a look at these awesome ladies. 1 total views, 1 views today Download this infographic.Embed Our Infographic On Your Site!Image Width%px<img... http://www.ucollectinfographics.com/?p=79426 #DatingOlderWomen, #Elder, #ElderLove, #ElderWomen, #OlderFemaleCelebs, #Senior, #SeniorCelebs, #SeniorFemaleCelebrities, #SeniorLove, #SeniorWomen www.ucollectinfographics.com | #FreeInfographicSubmission

#dating older women#elder#elder love#elder women#older female celebs#senior#senior celebs#senior female celebrities#senior love#senior women#Celebrities#Infographics#Lifestyle#Love and Sex#Pageantry

0 notes

Text

The Festival - Developer Log 5, 5/25/24

Hey everyone! It’s been a while since our last devlog. I apologize for the delay – I spent all of April finishing the Spring 2024 term here at UConn, and then I’ve been trying to take a break from The Festival the past couple weeks.

Truth be told, I was pretty taxed from life’s responsibilities the past few months, so I’m glad I was able to take some time to rest and recuperate.

I’m currently easing back into development on The Festival for the summer, and so I’d like to use this devlog as an opportunity to recount what I actually got done for the semester.

In previous devlogs, I showed a lot of incremental progress – character models being incorporated into the game, animations being made, and testing out the DialogueTree plugin I am working with. The following video is what I showcased to my MFA committee at the beginning of May, which showcases all of the work I’ve done up to this point.

youtube

This is a preview of the game’s Hemmingward quest, which will be the game’s ‘demo’ quest, along with the one quest I hope to have completed by the end of my time at UConn.

I don’t believe I’ve elaborated on this in a previous document, but due to various time constraints (along with the difficulty in making my first game), I decided this semester that I will only have this quest completed by the time I complete my MFA next year.

It will essentially serve as a vertical slice, which I will build upon and (hopefully) use to secure funding and interest going forward. Overall, this project is very near and dear to me, and I intend on developing it into a full release long past my time at the University of Connecticut.

As far as this current build goes, it’s very rudimentary, but this video showcases part of the Hemmingward quest’s script, and how Nishma and Gil interact with the major characters of this story – Helvan Dynicus, a shifty businessman …

... And the Elderwomen of Hemmingward, who Nishma is trying to learn a secret recipe from.

From left to right: Elder Margot, Elder Camaltha, and Elder Eurydice.

The Elderwomen’s models still need some editing and touching up, but I will save that for polish down the road.

One of the biggest technical developments in-game – which I’m unfortunately not going to keep for now – has been camera switching being triggered through dialogue. It was something I spent a lot of time working on, and it helped me better understand how the “Events” nodes work for the DialogueTree plugin, but I don’t think I’m a fan of how it currently looks. I may instead consider a top-down view with dialogue portraits, similar to the dialogue systems of either Disco Elysium or Hades. (see below for an example)

As of today, I am slowly easing back into work with The Festival. I have to eventually finish the script for the Hemmingward Quest, and I will provide a more expansive explanation of what that quest entails in a future post. For now though, I am currently working on something smaller and with lower stakes: grass sprites!

Working on vegetation has been a good way for me to ease back into the larger project, and it’s been much more relaxing to do now that the current semester is over.

I can’t guarantee when I will be able to update this blog again, but I am excited to resume work on The Festival for the summer.

The next major things I would like to post about would be the Hemmingward quest, along with a character bio for Gil Yurez, Nishma’s friend and bodyguard.

3 notes

·

View notes