#eiger nordwand

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#mine#My Pictures#my picture#photography#amateur photography#nature#nature photography#mountain#mountains#bergen#mountain photography#switzerland#die schweiz#helvetica#eiger#eiger nordwand#eiger mountain

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

How is everyone having sexy dreams about Ewan??

I dreamt we were mountain climbing and he kept messing around with the ropes and bolts and I had to climb back and forth to rix them like ten times which really pissed me off but he got a laugh out of that every time and then asked me if we couldn't "wing it?" And then I looked up and it was the flipping Eiger-Nordwand...

Dream-me yelled at him so hard I woke up, but since then I hc that he drinks red bull from time to time

He also wasn't wearing a helmet

That sounds incredibly irritating. I’d have woken myself up from frustration crying lol

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

the Eiger Nordwand

0 notes

Text

Gran Turismo 7 ottiene l’aggiornamento 1.49 con 6 auto, il nuovo circuito alpino e fisica migliorata

Gran Turismo 7 ottiene l’aggiornamento 1.49 con 6 auto, il nuovo circuito alpino e fisica migliorata Gran Turismo 7 si espande ancora con il prossimo arrivo dell’aggiornamento 1.49, che porta con sé 6 auto, il nuovo circuito alpino Eiger Nordwand (un ritorno, a dire il vero) e fisica migliorata. Powered by WPeMatico Gran Turismo 7 si espande ancora con il prossimo arrivo dell’aggiornamento 1.49,…

0 notes

Text

• Toni Kurz

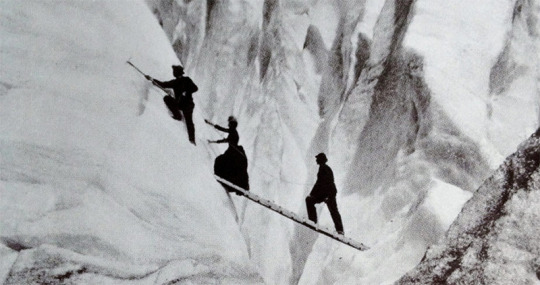

I have watched Nordwand (2008) which is a movie about two Alpinists' climbs of the dangerous Swiss Eiger north face. I was very touched by the ending of the movie and the fact that it was a true story. In fact, this is not the most famous photo of the protagonist of this story; it's the moment he died but I didn't want to share it here.

0 notes

Text

#16 Ball Pass

Im Mt. Cook Nationalpark haben viele Bergsteiger wie auch Edmund Hillary für ihre Begehungen im Himalaya trainiert. Seine langen, steilen, vergletscherden Felswände sind eine Seltenheit. Und das bei guter Zugänglichkeit und ohne all die Anforderungen die die Höhe zusätzlich noch mit sich bringt. Da wir auch bald nach Nepal fliegen werden macht das natürlich auch Sinn für uns.

Die Tour die wir uns vorgenommen haben führt uns ganz nah an den höchsten Berg Neuseelands heran. Zunächst entlang des Hooker Gletschers, welcher direkt aus der Westwand des Mt. Cook und angrenzender Berge entspringt. Unterhalb seiner Ostwand überschreitet die Route den Ball Pass um dann ins Nachbartal zum Tasman Gletscher hin abzufallen. Eine herrliche Wanderung. Drei Tage mit dem Zelt. Teils weglos. Immer Alpin. Bei perfekten Wetter.

Unser Lager für die erste Nacht ist auch Spielplatz von acht Keas die vor Einbruch der Dunkelheit, mit Aufgehen des Mondes und mit der ersten Dämmerung fleißig um das Zelt tanzen und schauen was man alles anpicken kann. Tolle Atmosphäre. Dieses bedrohte Tier so in Ruhe aus dem Schlafsack heraus aus der Nähe beobachten zu können ist schon eine tolle Erfahrung. Merklich klüger als alle Vögel die ich bisher erlebt habe lässt sich ein Kea nicht einfach durch ein harsches "Shhhhh" verscheuchen. Auch ein Steinwurf in seine Nähe ist ihm egal. Tolles Tierchen.

Am nächsten Morgen geht es steil über Schuttfelder um eine Felsrippe und der Blick auf den Ball Pass wird frei. Steil wirkt er und Schneefelder unter dem Pass. Wie erwartet. Gut 1,5h steigt man durch Schutt bis man die Schneefelder erreicht. Diese werden immer flacher ja näher man kommt und lassen sich mit Steigeisen problemlos queren.

Zum Pass dann noch eine recht steile Schuttrampe und der Blick auf die höchste Felswand Neuseelands ist frei. Das 2000m hohe Caroline Face, die Ostwand des Mt Cook. Der El Capitan in Yosemite hat mit seinen 1000m Höhe schon mehr als gewaltig gewirkt. Aber es ist immer die Perspektive. Wenn alles riesig ist passen 2000m wieder ins Verhältnis.

Gewöhnungsbedürftig: Auf der Südhalbkugel bleibt Ostwand Ostwand, aber Südwand wird zu Nordwand. Hier unten wäre bspw. die Eiger Südwand die berüchtigte Wand die kaum Sonne bekommt.

Das zweite Lager ist in einer herrlichen kleinen Senke mit Blick zur Ostwand.

Die ganze Zeit gehen Lawinen am Mt. Cook ab und man kann die Wand in Ruhe beobachten. Diesmal kein Eis auf dem Zelt wie in der Vornacht. Noch 13km wieder rauslaufen und 1000 Höhenmeter Abstieg und dann zum Ausgangsort Hitchhiken um unser Auto zurückzubekommen. Alles reibungslos. Besser kann das Ball Pass Crossing nicht laufen. Tolle Tour.

Die Änderung der alpinen Landschaft ist auch hier sehr deutlich. Man sieht genau die extrem steilen seitlich Moränen die der Gletscher bei seinem Rückzug frei werden lässt. Sie lassen seine einst (vor ca 10.000 Jahren) gewaltige Größe erahnen.

Diese steilen Seitenmoränen bestehen aus Schutt und Steinen bis Hausgröße und rutschen immer weiter ab und fressen den Berg über sich langsam auf. Grau frisst Grün. Wie in der Stadt. Früher hat der Gletscher diese Wände gehalten. Natürlicher Prozess an sich. Beschleunigt durch uns. Merklich spürbar auch für uns schon jetzt. Das Ball Pass Crossing ist deutlich anspruchsvoller geworden, da Teile des Weges abgerutscht sind. Es mussten Hütten im Nationalpark verlegt oder abgebaut werden, weil sie gefährdet sind bzw. der Zugang nicht mehr möglich war. Und auch wir mussten als wir dem Gletschern folgten häufig weit nach oben in die steilen Wände ausweichen weil sich von der Seitenmoräne die Auswaschungen tiefe schluchtenartige Schneisen schneiden.

Belohnung muss sein.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

#switzerland#alps#swiss alps#eiger#grindelwald#northface#eiger nordwand#eiger north face#clouds#hiking#hike#snow#bernese alps#bernese oberland#landscape#travel#mountain#mountains#travels#travelblr#europe#eurotravel#peak#travel photography#landscapes#landscape photography#mysterious#snow covered#ominous#landscape photo

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

To the summit in a skirt: Lucy Walker, pioneering Victorian Alpine mountaineer

The stories of women just weren’t written, so people tend to think they didn’t happen. There have always been women who have had the courage to step out into the unknown, and that’s what Lucy Walker did. The fortitude, the bravery, the commitment to the goal - women’s power was not invented yesterday.

- Rebecca A. Brown, Women on High: Pioneers of Mountaineering

Leaving behind a quiet life of croquet and cream teas, Lucy Walker became one of Britain’s finest early Alpine mountain climbers. Her climbing career spanned some 21 years, totalling 90 or so different summits, many being first ascents by a woman. Walker was the first woman to summit the Matterhorn and the Eiger - in a billowing Victorian dress no less - but she nearly vanished from history.

Her story as a female pioneering mountaineer has always inspired me in my mountaineering sojourns to the Alps and other mountainous places. During my time in the army flying combat helicopters I enjoyed free weekends that did come my way to take off to the Alps with like minded friends and climb together.

Mountains are so special; they have such magic to them. Maybe it is the fact they are can be so dangerous or maybe it is because they make us feel so small. Even if you don’t even climb them they call to you.You might find that all the problems in your life dissolve when you are around them or that life slows down a bit. All that I can tell you is that after spending time surrounded by them or climbing them you will feel the urge to come back.

Climbing a mountain is the furthest thing from easy. Long stretches of constant vertical climbing can be the most exhausting and hardest thing you do. Not only the physical difficulties but also the mental difficulties will also test you. Exposed and tricky climbing and route finding can get the best of your mental abilities.

The classic quote that tells you “not to look at the whole mountain take it one piece at a time” is something you will come to understand. You will learn to never give up; to know that the reward will be worth the work it takes.

Lucy Walker possessed great strength, endurance and determination and was an inspiration, especially for other women climbers. Indeed she paved the way for a wave of other - largely forgotten - women mountaineers to test the limits of their own mental and physical strength and courage against not only some of the hardest mountains to climb but also some the harshest social strictures against women seeking adventure.

Born in Liverpool in 1836, Lucy Walker was a British woman widely credited as being the first female alpine mountaineer. But this 19th century alpinist left behind no diaries, newspaper interviews, or personal accounts of any kind. And yet her presence haunts the annals of early mountaineering like a persistent ghost. Her serene, inscrutable face stares out from among men in Victorian-era expedition photos, and she lurks in a doorway in a renowned engraving of top 19th century alpinists - all male except for her. In journals, male climbers describe sightings of Walker briefly drying her sodden clothes at a hut or moving fast through deep snow and the astonishment of villagers after she became the first woman to climb the Eiger.

On Lucy Walker’s first trip to the Alps in 1858, she – unlike many people – was not content to remain in the valley but accompanied her brother and father into the high mountains. Whereas today climbers use cable cars or trains for the first part of an expedition, in the 19th century, several hours of steep walking was required. Lucy wanted to climb and at the sight of the Alps she began her life time obesession with mountain climbing.

Walker would go on to become one of the first and most prolific female mountaineers of the 19th century. Over the course of her 21-year career in the Alps, starting in 1858, Walker undertook 98 expeditions, including 28 successful attempts on 4,000-meter peaks. She holds first female ascents on 16 summits, including Monte Rosa, the Strahlhorn, and the Grand Combin, and a first ascent for either sex on the Balmhorn, which she completed in 1864.

But it was perhaps the Matterhorn ascent that gained her the most fame. The Matterhorn was regarded as the most desirable trophy by both men and women mountaineers. Lucy Walker was not the only woman whose dream it was to reach the peak. Various women attempted the ascent, most notably Meta Brevoort (1825-1876), a New Yorker who had settled in England. Just like Miss Walker, Meta was making a name for herself in the mountaineering world in the late 1860s. In 1869, Meta undertook her first attempt to climb the Matterhorn and, approaching from the Italian side, reached an altitude of just under 4,000 metres before being forced to turn back due to severe weather conditions.

Two years later, however, Meta Brevoort decided to give it another go, setting out for Zermatt with the aim of attempting another ascent. Lucy Walker was already in Zermatt though and, on receiving word of Ms Breevort’s intentions, quickly assembled her own group in order to begin her ascent of the Matterhorn, a feat that would make her the most famous female mountaineer of the era.

Long before dawn on July 21, 1871, Walker woke up in a hut on the northeastern flank of the legendary mountain, surrounded by men. She wore her favorite long dress and hobnail boots as she, her father, their guide, and several other climbers set off on snowy slopes in the flickering gloom of candle lanterns.

The mountaineers were probably nervously aware that six years earlier, four men from the first expedition to stand on top of this 14,692-foot spire on the Swiss-Italian border fell and perished on their descent. But Lucy Walker was determined that the American Meta Brevoort would not be the first woman to reach the summit. Walker fully intended to beat her to it.

As the sky brightened and smoke rose from breakfast fires in the village of Zermatt far below, the climbers ascended a skinny, ice-encrusted ridge with heart-palpitating exposure. One mindless step could have sent them plunging a thousand feet down to the valley below. But by midmorning, with willful determination and agreeable weather, they reached the summit. A tableau of rocky pinnacles, meadows, forests, streams, and villages unfurled in every direction - and Walker was the first woman ever to see it all from that iconic perch.

Meta Brevoort arrived just after Lucy‘s achievement to receive the shocking news that she had missed her chance to win the ultimate trophy. That very evening, the two women met each other in Zermatt. What Meta really felt on this occasion is anyone’s guess but contemporary sources state that “there were congratulations” – noblesse oblige.

This would be the only occasion that the two most prominent female Alpinists of the era would meet, somewhat unusual considering that they came from a similar background. Lucy Walker came from a wealthy merchant family in Liverpool and Meta Brevoort from a family of Dutch immigrants who made a fortune in New York as property owners.

Contrary to the strict notions of Victorian society, both women were outgoing and cheerful characters with a lively spirit. According to her obituary, Lucy was known for her “warmth, humour and buoyant personality” while, according to chronicler Cicely Williams, Meta stood out for her “astounding vitality and her exception gift of living life to the full”.

Walker’s other great accomplishment - amongst the many she already had achieved - was the Eiger. Mountaineers down the ages to the present will say hands down that it is the most dangerous of all Alpine mountains.

The Nordwand, or north face, of this peak in the Bernese Alps in Switzerland is an objective legendary among mountaineers for its danger. Reaching nearly 6000 feet, it is the longest north face in the Alps. Though it was first climbed in 1938, the north face of the Eiger continues to challenge climbers of all abilities with both its technical difficulties and the heavy rockfall that rakes the face. The difficulty and hazards have earned the Eiger’s north face the nickname Mordwand, or Murder Wall. Lucy Walker didn’t climb the north face but she did climb it all the same. Nothing daunted her.

At 10.15 am on 25 July, 1864, a group of 11 people arranged themselves gingerly on the narrow arête of the Eiger’s summit, and “proceeded to howl [themselves] hoarse” in celebration of their achievement. The merriment was more raucous than usual because 28-year-old Lucy had just become the first woman to climb the mountain.

Poor visibility, ice and difficult route-finding threatened to defeat them, but as fellow climber Adolphus Moore noted, in a typical example of middle-class Victorian pride: “A repugnance to abandoning an undertaking once commenced…appears to be naturally inherent in the breasts of Britons, male and female alike.” When the party arrived back in the village, Moore noted that “the astonishment amongst the people, collected at the inn, at a lady having performed such an unusual feat, was immense and entertaining.”

Lucy Walker was the person that made women visible in the Alps for the first time. She was the first woman to ascend most of the major alpine summits and crushed through the glass ceiling, making it easier for women to follow. And yet the details of Walker’s life remain largely unknown.

At the time, women were expected to stay out of the public eye, avoid celebrating their accomplishments, and conform to narrow notions of femininity that prized meekness and subservience. While newspapers glorified male exploits in the mountains, they often ignored or satirized women who climbed, painting them as weak and unfit—or sometimes just laughable eccentrics. Women mountaineers of the 19th century generally underplayed their accomplishments in letters and books so as not to appear unfeminine and risk ridicule. Many did not write about their expeditions at all. Walker might have kept quiet about her climbing so that she could continue doing it in peace, but she also didn’t let the inevitable jibes discourage her.

“In those far-off mid-Victorian days, when it was even considered ‘fast’ for a young lady to ride in a hansom, Miss Walker’s wonderful feats in the mountains did not pass without a certain amount of criticism, which her keen sense of humor made her appreciate as much as anyone,” wrote Frederick Gardiner, a friend and mountaineer who climbed alongside Walker up the Matterhorn, in an obituary in the Alpine Journal in 1917.

Over the course of her climbing career, Walker proved herself a model of both skill and endurance, climbing mostly with her father and brother and possibly, as some scholars have suggested, outperforming them. She ascended the tallest technical peaks in Europe, braved spectacular exposure with unreliable ropes, and pioneered long, difficult routes through the high cols. According to friends who wrote about her, Walker was witty and lively and had a penchant for hydrating with champagne.

She also went to great lengths to avoid offending delicate Victorian sensibilities and gender roles—at least until out of sight. While climbing, Walker would walk out of villages looking every bit the proper lady and then stash her petticoat behind a rock. Like a chameleon, she transformed from an elite athlete in the Alps to a prim Victorian Englishwoman at home in Liverpool, where her family ran a lead-dealing business. Walker tended to the family house; kept up with her needlework; read widely in French, German, and Italian; and hosted parties. (She chose not to marry, however, which would have been unusual at the time.) There are no records of her ever scaling a British peak or even partaking in any exercise more taxing than croquet.

Perhaps because she didn’t brazenly challenge social norms, Lucy Walker’s activities in the mountains were occasionally feted. International newspapers covered her Matterhorn climb, and the satirical English magazine Punch even published a poem celebrating her fortitude.

“No glacier can baffle, no precipice balk her,” it read. “No peak rise above her, however sublime. Give three cheers for intrepid Miss Walker. I say, my boys, doesn’t she know how to climb!”

Clare Roche, a historian on 19th-century women’s mountaineering, argued that this recognition likely encouraged other women to be more adventurous in the Alps. Katherine Richardson, Margaret Jackson, and Emily Hornby, three of the best women mountaineers of the late 19th century, started climbing within a couple years of Walker’s Matterhorn ascent. Meta Brevoort was also inspired by her example, according to her nephew and climbing partner.

Even before that time, however, Walker was far from the only woman in the peaks. After examining historic führerbücher, books in which guides kept client testimonials, Roche discovered that from about the mid-1860s, women ventured into the mountains on technical expeditions in much greater numbers than previously thought. In the second half of the 19th century, women completed nearly 60 first ascents on Europe’s high peaks and more than 100 first female ascents. These include Brevoort’s first winter ascent of the Jungfrau in 1874 and Margaret Anne Jackson’s first ascent of the east face of Weissmies in 1876.

Letters suggest that while there were rivalries, women climbers also formed a sort of sisterhood in the mountains and helped each other out, Roche says. Even though women weren’t allowed to file papers in the Alpine Journal until 1889 and were excluded from the Alpine Club until 1974, some of their male counterparts welcomed them in the high country. These wild areas afforded rare freedom in a time of stifling social constraints. In coed expeditions, women climbed and slept alongside men, a practice that would have been unthinkable in the valleys and cities. In the late 1800s, women even led men on expeditions without guides, which had been customary earlier in the century.

In later life Lucy continued to walk in the Alps and meet with friends, including Melchoir Andregg, who was the foremost Swiss mountain guide of his time and is still revered today. When asked why she had never married, her typically direct reply was: “I love mountains and Melchoir and Melchoir already has a wife!”

Walker continued to climb until her mid-forties, when a doctor advised her to stop for health reasons that are now unknown. She continued to walk in the Alps long after her climbing career and acted as a mentor to younger climbers, encouraging them to write about their experiences. Although Lucy was an extremely capable mountaineer, she was never allowed to join the male-only Alpine Club in London but did become the second president of the Ladies’ Alpine Club in which she was involved in the founding in 1907.

Most Victorian doctors advised gentlewomen to refrain from any strenuous exercise; the demands of mountaineering went way beyond strenuous. It is a measure of Lucy’s character that she clearly ignored medical diktats. She was an educated woman, spoke several languages, knew her own mind and was not prepared to conform to any convention if it meant restricting her mountaineering.

In the Alps, she regularly climbed for more than 14 hours a day, tackled some of the most difficult summits and slept in barns high in the mountains, often close by the men in the party. Home life in Liverpool could not have been more different. There she played croquet, entertained and led the respectable life expected of a Victorian lady.

Even on the mountains, she was keen to maintain a feminine appearance whenever possible, always wearing skirts, but removing her crinoline once outside the village. Dresses were arranged so they could be shortened easily on steep or rocky slopes. Trousers didn’t become popular with women until the 1890s, long after Lucy’s climbing was over. She later said how envious she was of the easier conditions women experienced in the early years of the 20th century.

Although Lucy wrote nothing about her climbing, others did, noting her penchant for champagne – a common tipple among mountaineers, especially those who made unprecedented climbs. Lucy would get through several bottles during the course of an expedition. She became a renowned personality in the Alps whom everyone wanted to meet because, as famous mountaineer Edward Whymper, claimed, “no candidate for election in the Alpine club… ever submitted a list of qualifications at all approaching the list of Miss Walker.”

Lucy Walker died, in September 1917, at 81. But in the century since her death, Walker has nearly vanished from the public record. How many other women quietly pulled off great feats of athleticism but fell through the cracks of history without so much as a whisper? Walker at least lives on in the words of those who knew her.

“Her energies were immense and she was a bold, inveterate and able sightseer,” wrote mountaineer Charles Pilkington in the Alpine Journal after Walker died. “We were often roused by her from our laziness and taken to some point of view or interesting place, which but for her insistence, we might have missed. Traveling in her company was always enlightened by her great vivacity.”

#lucy walker#walker#pioneer#mountaineer#climbing#alpine#alps#matterhorn#adventure#history#femme#women#british#society#outdoor sports#nature#icon#personal

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Walking under the north face of the Eiger a couple of weeks ago was an ambition fulfilled. The film Nordwand or North Face was my first introduction to the epic stories which unfolded on the North Cave is the Eiger and ever since I just wanted to get an idea of its scale. I still don’t think I have, certainly have no idea what it would be like to try and climb it. #REchargejourney #eneloopREchaege #grindelwald #switzerland #eiger (at Grindelwald, Switzerland) https://www.instagram.com/p/B32ZfZQhaEn/?igshid=186nud6zd738i

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

5 Most Dangerous Mountain to Climb in the World

Some mountains have the treacherous weather condition with strong storms. While some mountains have cliffs that are impossible to climb. And, there are some mountains with risks of avalanches and rock falls in every single step.

Considering these risk factors and the fatality rate in each mountain, here’s a list of 10 hardest mountains to climb in the world.

1. Annapurna

Annapurna I – the 10th highest peak in the world tops the list among the hardest mountains to climb. Fascinating and equally dangerous – Annapurna rises to 8,091 meters in the Himalayas.

Unlike Everest, it attracts only those mountaineers that are top on their game. Unfortunately, one-third of them never return.

Annapurna I – the main peak in Annapurna massif has seen only 191 climbers conquer it. The deaths of 72 climbers on this mountain brings death rate to 38%. No other mountains in the world have such a high fatality rate.

Moreover, at such a high altitude in the cold climate, climbers often suffer from medical problems like altitude sickness, pulmonary edema, and more. Inaccessibility and lack of enough local support also play some roles in making Annapurna hardest to climb as compared to other eight-thousands.

2. K2

K2 offers deadly challenges with its extreme technicality. While around 500 reach the summit of Everest every year, K2 sometimes remain unclimbed an entire year. With a nickname “Mountaineer’s mountain”, only the elite mountaineers attempt to scale this mountain.

The bad weather and avalanches in the K2 mountain can hit upon the climbers any time. The steep slopes make the climb technically difficult. To worsen the expedition, there are sections of rocks that may collapse at any time on climbers.

The bottleneck is an infamous and deadly section on K2. The climbers have to travel across massive ice wall right beneath an overhanging glacier. The seracs are unstable and avalanches can occur at any time.

3. Nanga Parbat

Nanga Parbat is the ninth highest peak in the world. But, when we look at its technicality, the difficulty level is close to that of mount K2. With the difficulty that the expedition team experience and the increasing fatality rate, mountaineers call Nanga Parbat “The Man Eater.”

The avalanche is the major cause of deaths of most climbers on Nanga Parbat. Other major causes are falls and exposure to cold. Due to the extreme cold, climbers have never summited this mountain in the winter.

The southern face of the mountain is the largest mountain face on this entire earth. Known as, “ Rupal Face”, this southern face of Nanga Parbat rises 15,000 foot tall from its base.

The latest tragedies occurred in June 2017 when two climbers went missing and January 2018 when a Polish climber died in the attempt. At present, the death rate on Nanga Parbat stands at 22 %.

It is not the mountain only that poses threat in Nanga Parbat. The 2013 terrorist attack at Nanga Parbat killed 11 climbers. With all these past events, it’s clear why the climbing world referred this peak as the hardest mountain to climb.

4. Kanchenjunga

Firstly, Kanchenjunga is too remote. It takes you around two weeks just to reach the Base Camp. So, you are already tired before you begin your climb. Besides these, the major danger lies on the mountain itself. There are many short technical climbs to do on the way. A few times, you have to walk right beneath overhanging glacier and seracs that may tumble down at any time.

So, the avalanche is the major risk factor while trying to ascend this mountain. There are also very steep sections of 45°- 50° which make climbers nervous. Moreover, a steep section above Camp IV has taken lives of so many climbers while trying to return back from the summit. So, descending down from the summit looks more difficult than reaching the summit.

To sum up, the bad weather, avalanche prone areas, and steep climbing slopes all play a major role in making Kanchenjunga one of the most dangerous mountains in the world.

5. The Eiger

The most dangerous mountains are not always the tallest ones. With the height of only 3,970 meters from the sea-level, it is marked among the hardest mountains to climb in the world. Eiger stands over the small settlement of Scheidegg in the Bernese Alps. As compared to other huge mountains, it looks so small and is easily accessible. But, do not let the size and accessibility of the Eiger fool you- it is one of the most dangerous mountains in the world.

The north face, also known as Nordwand, is a huge wall of shattered limestones. This 1800-meters high wall is the largest north face in the Alps. With the difficulty and hazard it posses, the climbing world calls it “Murderous Wall.” Many climbers have died while attempting to scale the Eiger through the Murderous Wall.

The north face has several technical sections. Due to the melting of snow, there is a high risk of rock falls, ice falls, and avalanches. Many climbers have retraced back from a few hundred meters short of the summit due to rocks and ice falling on them.

10 Essential Items To Bring On Your Next Trek:

1. Navigation

Map (with protective case) Compass GPS (optional)

2. Sun protection

Sunscreen Lip balm Sunglasses, goggles or glacier glasses

3. Insulation

Jacket, vest, pants, gloves, hat (see Clothing)

4. Illumination

Headlamp or flashlight (plus spare) Extra batteries (kept near body when cold)

5. First-aid supplies

First-aid kit (see our First-Aid Checklist)

6. Fire

Matches or lighter Waterproof container Fire starter (for emergency survival fire)

7. Repair kit and tools

Knife or multi-tool Duct tape or other repair items

8. Nutrition

Extra day supply of food Energy bars

9. Hydration

Water bottles or hydration system (insulated) Water treatment system

10. Emergency shelter

Tent, tarp, bivy or reflective blanket

1 note

·

View note

Text

#mine#My Pictures#my picture#photography#amateur photography#nature#nature photography#mountain#mountains#bergen#mountain photography#switzerland#die schweiz#helvetica#eiger#eiger nordwand#eiger mountain#wasserfall#waterfall#waterfalls

88 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Eiger Nordwand .. [3 / 3] The north face of the Eiger during the approach to Kleine Scheidegg.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

what i read in january

too many books....

the unwomanly face of war, svetlana alexievich (tr. from russian) oral history of soviet women who served in ww2 (whether as soldiers, pilots, field nurses, laundresses etc, plus partisans) - interesting and harrowing, but honestly (& this just comes with the format i guess but it still made the book less enjoyable for me) pretty repetitive. 3/5

my sister, the serial killer, oyinkan braithwaite dark & snappy novel about beautiful ayoola, who has a habit of killing all her boyfriends, and her resentful but protective older sister korede, who always ends up cleaning up after her - until ayoola starts dating the man korede is in love with. not suuuper substantial, but an entertaining, twisty read with some hidden depths and great dark humour (ayoola about her trip w/ a boyfriend: ‘it was fine.... except he died’). 3.5/5

the private memoirs & confessions of a justified sinner, james hogg (uni) fucking wild ride of a book about (and mostly narrated by) a young calvinist radical who believes that, like, since he is one of the elect of God and his place in heaven is guaranteed no matter what he does, he might as well DO SOME MURDER!!! it’s fun, the theology is absurd, and one of the main characters (our young calvinist’s shapeshifting friend) is probably the devil! 4/5

friday black, nana kwame adjei-brenya collection of mostly speculative/dystopian short stories, some of which work very well, some of which don’t really. the stories based on racism in america are mostly very good, satirically heightening current issues to absurd levels while still feeling true. some others are not as good, including one where a man talks to the ghosts of the fetuses his girlfriend just aborted (like. bad.) the last story, a post-nuclear-apocalypse groundhog day type thing, is brilliant and i almost wish he’d turned into a novel/novella instead. 3.5/5

mythologies, roland barthes god, i wish french crit was always as fun as roro ‘kill the author’ barthes making fun of the myths of american evangelicalism and french imperialism. 3/5

moon of the crusted snow, waubgeshig rice set in a northern canadian first nations reservation, where one autumn, electricity, communications etc. fail. when no news (or scheduled deliveries of food etc) come from the south, the community has to figure out how to get everyone through the winter, relying increasingly on traditional survival skills. quiet & reflective twist on the post-apocalypse/social collapse narrative; occasionally the writing is a bit clumsy, but i’d still recommend it. 3.5/5

the haunting of hill house, shirley jackson a psychological haunted house story, more quietly disturbing than downright scary, but i really enjoyed the way the characters interact with each other and the visceral wrongness of hill house. also interested if anyone has done a queer reading bc i def feel like there’s some subtext between eleanor and theodora that plays into the horror (time to check jstor). and i just love jackson’s style of writing. 4/5

tentacle, rita indiana (tr. from spanish, i read the german translation) weirdo dominican queer post-apocalyptic time travel book involving yoruba/voodoo mysticism, time travel via anemone, art collectives, a trans protagonist who is the chosen one, destined to save the ocean, and a mention of einstürzende neubauten (automatic 0.5 point bonus). really cool! there is a lot of sexual & gendered violence so uh. that’s something to be aware of. 3.5/5

the orenda, joseph boyden ugh. so this is a historical novel set in 1600s northern america, centred around the huron/wendat nation and three characters: the wendat warrior bird, a jesuit missionary called christophe who lives among the wendat, and the young iroquois girl snow falls, who is... forcibly adopted?? by bird to replace his murdered family. interesting concept and a promising first third or so, but unfortunately the book is way too long, the characters and their relationships seemed shallow and their development was more Told than Shown to me, and it just never really came together for me. plus, halfway through i found out that boyden has apparently been either greatly exaggerating or completely making up his own native heritage so uh. bad. 1.5/5

nichts was uns passiert, bettina wilpert smart & very precisely observed story about an alleged rape in a lefty/academic social circle. anna claims jonas raped her at a party, while jonas says the sex was consensual. anna eventually goes to the police and as rumours begin to spread, the people around them begin to take sides and try to figure out how to deal with this thing that Does Not Happen To Us (the title) and is definitely not Done by People Like Us. in a smart twist, this is presented as testimonies collected by an unnamed first-person narrator who questions jonas, anna, their friends and family, which i found very effective as a narrative tool, making everything just ambiguous enough. ends on a legalese gutpunch. 4/5

o caledonia, elspeth barker lovely dark book about janet, outcast at school and in her family, always too intense, too earnest, too clumsy, as she grows up first in wartime edinburgh and then in an old house in the scottish highlands, feeling at home only among animals and the wild & harsh & romantic landscape. lyrically written, sometimes morbid and grim (the book opens with janet murdered at 16 y’all), but often funny and bittersweet as well. loved it! 4.5/5

espedair street, iain banks look, this is a novel about a burnt-out rockstar looking back on his rise to fame and wild life, which is like. incredibly unappealing to me from the beginning. tho i gotta give props to banks for managing to make me at all invested in this story with good writing & well-engineered weirdness - so i guess i need to read something from him where the very premise does not make me roll my eyes. 2/5

eiger dreams: ventures among men & mountains, jon krakauer i would never willingly go mountain-climbing but i sure am highkey obsessed with reading about it. this is a collection of short essays about mountain climbing, some about krakauer’s own experiences (trying to climb the eiger nordwand etc), some about special areas of climbing, infamous climbers etc, and krakauer is a good writer & funny dude (don’t smoke weed in your tent while on an expedition lmao). krakauer says in his foreword that “most climbers aren’t in fact deranged, they’re just infected with a particularly virulent strain of the Human Condition”, which is a great sentence, but based on this and into thin air it seems like that’s in fact the same thing! 3.5/5

fool’s errand (the tawny man #1), robin hobb y’all. i missed my silly silly son fitz who is now significantly older than me, and i was immediately captivated even tho the first 200 pages are mostly fitzy’s Hermit Homesteading Routine with Occasional Visitors. i loved that shit. i loved fitz being reluctantly-but-maybe-not-that-reluctantly being caught in court intrigue & schemes again even more. anyway, hobb’s strength as always is amazing characterisation that makes every character immediately seem real & rich and the relationships between those characters, which are nuanced and fraught and painful and wonderful (also when will fitz & the fool kiss JESUS). also it made me cry a lot about nighteyes, so well done there. 4/5

anyway i am now forcing myself to not just abandon all else and just speed thru tawny man but i really really want to so everything else is going quite slowly

#this looks like a lot of books (and is actually a lot of books) BUT#most of them were super short! like under or just over 200 pages!#i love 'infected with a particularly virulent strain of the Human Condition' but yeah that does 100% equal 'deranged'#the books i read

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

DANI ARNOLD und seine Begeisterung für die Schönheit der Berge. Ein Multimedia- Vortrag über Extrembergsteigen, Schnelligkeit, Leidenschaft. SAMSTAG, 25. MÄRZ 2023, 19.30 Uhr (Türöffnung 18.30 Uhr) Ort: Oberstufenzentrum Seidenbaum, Seidenbaumstrasse 1, 9477 Trübbach Eintritt: CHF 28 mit Vorkasse Reservation erforderlich – Platzzahl beschränkt! Reservation unter: [email protected] oder 079 233 42 54 …und irgendwann trennt sich der Spreu vom Weizen! Es gibt viele gute Alpinsten, es gibt viele Ausnahme-Alpinisten und es gibt Dani Arnold! 2011 hat der gebürtige Urner, aufgewachsen auf 1700 Meter, hoch über dem Schächental, seinen Beruf als Maschinenmechaniker an den Nagel gehängt. Seither lebt Dani Arnold seinen Traum vom Extrembergsteigen. Mit schnellen Solo-Begehungen in der Eiger-, Matterhorn und Grandes Jorasses-Nordwand hat er neue Massstäbe gesetzt! Dann kamen die Nordwände von Piz Badile, Aguille du Dru und Grosse Zinne dazu. Solo und extrem schnell! 9:39 ist seine Zeit für diese 6 grossen Nordwände und zugleich der Titel seines neuen Buchs… In seinem neuen Vortrag geht es um Erfolg und Scheitern an den grossen Bergen, um Taktik und Gefühl für die grossen Wände und um die Werte und Ziele, die man als Bergsteiger braucht und um seine grosse Leidenschaft für die Schönheit der Berge… #daniarnold_alpinist #alpinism #northface #nordwand #swissmade (hier: 9476 Weite) https://www.instagram.com/p/Cn1OkhoMSgo/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

Wir werfen einen Blick auf die gefährlichsten Berge der Welt und was sie so tödlich macht Ob es die Überlebensgeschichten sind, die von ihren tückischen Hängen bluten, oder die Visionen von Tapferkeit, die sich im Kopf sammeln, die gefährlichsten Berge der Welt machen weiterhin Schlagzeilen auf der ganzen Welt. Diese Berge üben eine morbide Faszination auf Bergsteiger, Kletterbegeisterte und Nachrichtenjunkies aus. Ich bin nicht anders. Meine Bücherregale, mein Kindle und meine Filmsammlung sind gefüllt mit Bergsteigerbüchern und -filmen und den tragischen Geschichten, die sie aufzeichnen. Es ist diese Faszination, die mich dazu gebracht hat, die gefährlichsten Berge der Welt zu untersuchen und zu untersuchen, was sie tödlich macht. Die gefährlichsten berge der welt Es gibt keine einzige empirische Studie über die gefährlichsten Berge der Welt. Daher habe ich mich auf eine Kombination aus Statistiken und einem breiteren Ansehen verlassen. Die Liste ist daher naturgemäß subjektiv, bietet aber einen zuverlässigen Querschnitt der gefährlichsten Berge der Welt. Diese sind nicht unbedingt die höchsten, die technischsten oder die abgelegensten. Manchmal ist es genau das Gegenteil: Bequemlichkeit, Nachlässigkeit und Überfüllung können zu höheren Sterblichkeitsraten auf niedrigeren und weniger technischen Gipfeln führen. Von mächtigen Achttausendern bis hin zu weniger bekannten Hügeln gibt es die gefährlichsten Berge der Welt in allen Formen und Größen. Manchmal sind es die Wetterbedingungen, ob Lawinen, Sturmböen oder überraschende Stürme, die einen Berg wirklich tückisch machen. 1. Nanga Parbat Höhe: 8.126 m (26.660 ft) Lage: Pakistan Reichweite: Himalaya Traumzeit Nanga Parbat war einst als Killer Mountain bekannt Lassen Sie sich von der Schönheit dieses Berges nicht täuschen: Der Nanga Parbat ist ein bekanntermaßen schwieriger Aufstieg und war einst als „Killerberg“ bekannt. Vor 1990 hatte der Nanga Parbat eine erstaunliche Sterblichkeitsrate von 77 %, was bedeutet, dass Gipfelstürmer eher sterben als überleben! Die Sterblichkeitsrate ist seitdem gesunken, aber er gilt immer noch als der drittgefährlichste Achttausender nach Annapurna und K2. Bis 2016 wurde er im Winter nicht bestiegen und fordert weiterhin Menschenleben. Betörend umgeben von idyllischen Wäldern und Gletscherseen erhebt sich der tödliche Berg mit einem enormen vertikalen Relief aus dem ruhigen Gelände um ihn herum. 2. Montblanc Höhe: 4.808 m (15.777 ft) Lage: Frankreich / Italien Reichweite: Alpen Traumzeit Der Mont Blanc hat mehr Tote gesehen als jeder andere Berg Der Mont Blanc ist wohl der gefährlichste Berg der Welt. Der Berg hat bis heute bis zu 8.000* Todesopfer gefordert, er hat mehr Menschen getötet als jeder andere Berg, und die Todesfälle häufen sich. Ein bequemer und relativ untechnischer Berg wie der Mont Blanc sollte nicht so gefährlich sein. Das ist zumindest die Logik hinter 20.000 Bergsteiger-Touristen, die jedes Jahr den höchsten Gipfel Westeuropas suchen. Auf dem Höhepunkt der Klettersaison versuchen täglich 300 Kletterer, den Gipfel zu erreichen, was zu Überfüllung und Nachlässigkeit führt, wobei jedes Jahr bis zu 100 Kletterer auf dem Mont Blanc sterben. *Das Buch „The High Mountains of the Alps“ von 1994 behauptet, es habe zwischen 6.000 und 8.000 Todesfälle auf dem Mont Blanc gegeben. 3. Der Eiger Höhe: 3.967m (13.015ft)Lage: SchweizBereich: Alpen Die berüchtigte Nordwand ist eine der drei großen Nordwände der Alpen Die größte der sechs großen Nordwände der Alpen, die Nordwand des Eiger (der Oger), ist wie ihre Gegenstücke für ihre technische Herausforderung im Gegensatz zu ihrer Höhe bekannt. Mit „nur“ 3.967 m (13.015 Fuß) ist es nicht die Höhe, die seit der ersten erfolgreichen Besteigung im Jahr 1938 mindestens 64 Bergsteiger das Leben gekostet hat. Die berüchtigte Nordwand bildet zusammen mit den Nordwänden des Matterhorns und der Grandes Jorasses die „Trilogie“, eine Untergruppe der sechs großen Nordwände,

die sich von den anderen dadurch auszeichnet, dass sie noch schwieriger und gefährlicher zu erobern sind. In den letzten Jahren, mit immer mehr Besteigungen und Rekordstürzen, hat sich der bedrohliche Ruf des Eiger etwas verflüchtigt. Doch die Sage von der Mordwand lässt Alpinisten noch immer Schauer über den Rücken laufen. 4. Baintha Brakk Höhe: 7.285 m (23.901 ft) Ort: Pakistan Reichweite: Karakorum Ben Tubby: CC BY 2.0 Der Oger ist berühmt dafür, einer der am schwersten zu besteigenden Gipfel zu sein Baintha Brakk – auch bekannt als The Ogre – ist berühmt dafür, einer der am schwersten zu besteigenden Gipfel der Welt zu sein. Unerhört im modernen Bergsteigen vergingen 24 Jahre zwischen der Erstbesteigung des Berges im Jahr 1977 und seiner zweiten im Jahr 2001. Während dieser Erstbesteigung im Jahr 1977 durch Doug Scott und Chris Bonington brach sich Scott beide Beine, während Bonington sich zwei Rippen brach und sich eine Lungenentzündung zuzog. Es gab relativ wenige Todesfälle auf dem Berg, aber zwischen den beiden erfolgreichen Expeditionen gab es unzählige Verletzte und über 20 erfolglose Versuche. Trotz der vergleichsweise niedrigen Sterblichkeitsrate fordert der Baintha Brakk weiterhin Menschenleben, wenn Versuche unternommen werden, und gilt daher weithin als einer der gefährlichsten Berge der Welt. 5. Kanchenjunga Höhe: 8.586 m (28.169 ft) Lage: Nepal / Indien Reichweite: Himalaya Traumzeit Seit den 1990er Jahren sind etwa 22 % der Gipfelstürmer am Kangchendzönga gestorben Der Kangchendzönga liegt an der indisch-nepalesischen Grenze und ist der höchste Berg Indiens, der zweithöchste Nepals und der dritthöchste der Welt. Seit den 1990er Jahren sind etwa 22 % der Gipfelstürmer (etwa jeder fünfte) am Kangchendzönga gestorben, was ihn zu einem der gefährlichsten Berge der Welt macht. Mindestens 53 Todesfälle wurden auf Kangchendzönga registriert, darunter fünf im Jahr 2013 und weitere drei im Jahr 2014. Das Kangchenjunga-Gebiet ist eine zutiefst abgelegene Region und hat sich erst kürzlich für den Tourismus geöffnet. Der Berg selbst ist nicht sehr technisch, wurde aber nur 283 Mal bestiegen und ist damit nach dem gefährlichen und brutalen Annapurna der am zweitwenigsten bestiegene Achttausender. 6. Matterhorn Höhe: 4.478 m (14.692 ft) Lage: Schweiz Reichweite: Alpen Traumzeit Das Matterhorn ist einer der berühmtesten Berge der Welt Das Matterhorn, eine weitere der drei großen Nordwände der Alpen, ist einer der berühmtesten Berge der Welt. Der ikonische Pyramidengipfel, der oft für die Geburt des Alpinismus Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts verantwortlich gemacht wird, wird jedes Jahr von Tausenden von Kletterern erfolgreich bestiegen, wobei in der Hochsaison täglich bis zu 150 einen Aufstieg versuchen. Im Laufe der Jahre hat der Berg über 500 Menschen das Leben gekostet, was ihn zu einem der tödlichsten Berge der Welt in Bezug auf die Anzahl der Todesopfer macht. Es hat sogar einen eigenen Friedhof. In den letzten Jahren ist der Berg sicherer geworden, seit Anfang der 1990er Jahre starben jedes Jahr durchschnittlich fünf Bergsteiger an seinen Hängen, ein Jahr zuvor waren es noch durchschnittlich acht. 7. Cerro Torre Höhe: 3.128 m (10.262 ft) Lage: Argentinien / Chile Reichweite: Anden Traumzeit Der Cerro Torre ragt senkrecht aus dem patagonischen Eisfeld heraus Der berüchtigte Cerro Torre ist nicht nur unheimlich gefährlich, sondern auch zutiefst umstritten. Der Streit begann 1959, als Cesare Maestri behauptete, er habe den Berg erfolgreich bestiegen. Sein Partner Toni Egger war jedoch zusammen mit der Kamera in den Tod gestürzt, was den erfolgreichen Aufstieg bewies. Als in den folgenden Jahren jede weitere Expedition zum Cerro Torre scheiterte und weitere Todesopfer forderte, kamen Zweifel an Maestris Gipfel auf. Damit begann eine lange Reihe kontroverser Ereignisse. Unabhängig von der Kontroverse kann man mit Fug und Recht sagen, dass der Cerro Torre, ein steiler und scharfer Gipfel, der senkrecht

aus dem patagonischen Eisfeld herausragt und mit einer gefährlichen Schicht Raureifeis und heftigen Winden befestigt ist, einer der gefährlichsten Berge der Welt ist. 8. Berg Washington Höhe: 1.916 m (6.288 Fuß) Lage: New Hampshire, USA Reichweite: Presidential Range Traumzeit Mt. Washington würde nirgendwo anders als viel mehr als ein Hügel betrachtet werden Mt. Washington, der als der gefährlichste kleine Berg der Welt bezeichnet wird, ist zwar der höchste Gipfel im Nordosten der USA, aber nirgendwo sonst auf der Welt würde er als viel mehr als ein Hügel angesehen werden. Es ist jedoch ein gefährlicher Hügel. Seit 1849 sind fast 150 Menschen auf dem Mt. Washington gestorben. Der Berg erhält ungewöhnlich hohe Windgeschwindigkeiten für diesen Teil der Welt und der Unterschied zwischen Wandern im Sommer und Winter ist gravierend. Schlechte Planung führt oft dazu, dass Wanderer schlecht auf Wetteränderungen vorbereitet sind. Nicholas Howe, Autor von Not Without Peril: 150 Years of Misadventure on the Presidential Range of New Hampshire, sagte, dass die Menschen oft „den Unterschied im Wetter zwischen Boston und den Bergen“ nicht zu schätzen wissen. 9. Annapurna Höhe: 8.091 m (26.545 ft) Lage: Nepal Reichweite: Himalaya Traumzeit Das Annapurna-Massiv ist den besten Bergsteigern vorbehalten Annapurna ist der zehnthöchste und einer der gefährlichsten Berge der Welt. Er wird meist als der gefährlichste der Achttausender bezeichnet, da er lange Zeit die höchste Todesrate bis zum Gipfel und auch die wenigsten Gesamtgipfel hatte (im März 2012 waren es 191 Gipfel und 61 Todesopfer). Seit 1990 hat Kangchenjunga jedoch eine höhere Sterblichkeitsrate. In jedem Fall ist Annarpurna I und das breitere Annapurna-Massiv ein sehr gefährlicher Ort zum Klettern. Das Massiv ist normalerweise nur den allerbesten Bergsteigern vorbehalten, wobei nur eine Handvoll privat geführter Expeditionen jemals auf dem Gebirge stattfinden. 10. Everest Höhe: 8.848 m (29.029 ft) Lage: Nepal / China Reichweite: Himalaya Traumzeit Bis heute sind mindestens 297 Menschen am Everest gestorben Obwohl der Everest der höchste Berg der Erde ist, ist er keineswegs der gefährlichste oder technisch anspruchsvollste Berg, den es zu besteigen gilt. Doch allein der Reiz, auf dem Gipfel der Welt zu stehen, lässt Menschen mit Gipfelfieber an die Hänge des Berges strömen. Da jedes Jahr mehr und mehr Genehmigungen für die Besteigung des Everest erteilt werden (373 wurden 2017 ausgestellt – die meisten aller Zeiten), erwarten Sie Szenen wie diese Conga-Klettererreihe auf dem Everest. Seit Mai 2018 sind mindestens 297 Menschen am Mount Everest gestorben. Er ist vielleicht nicht der härteste, herausforderndste oder gefährlichste, aber er ist der höchste Berg der Welt. Bis sich das ändert, werden die Menschen weiter auf den Everest klettern und sterben, was ihn zu einem der gefährlichsten Berge der Welt macht. 11. K2 Höhe: 8.611 m (28.251 ft) Lage: Pakistan / China Reichweite: Karakorum Traumzeit K2 ist als der wilde Berg bekannt Allein die Erwähnung dieser Legende lässt einem das Blut in den Adern gefrieren. Der K2 ist aufgrund des extrem schwierigen Aufstiegs und der zweithöchsten Todesrate unter den Achttausendern als Savage Mountain bekannt. Mit rund 300 erfolgreichen Gipfeln und 77 Todesopfern stirbt etwa jeder vierte Bergsteiger an den Hängen dieses tückischen Berges. Wie die Annapurna, der Berg mit der höchsten Sterblichkeitsrate, wurde der K2 erst kürzlich im Winter bestiegen. Bisher wurden in diesem Jahr „nur“ zwei Todesfälle gemeldet – der erste seit 2014. Im Laufe der Jahrzehnte war der Berg jedoch Schauplatz mehrerer Katastrophen, nämlich der K2-Katastrophe von 1986, als fünf Bergsteiger bei einem einzigen Ereignis starben (13 während der Saison), die K2-Katastrophe von 1995, als weitere sechs starben (acht in der Saison) und zuletzt die K2-Katastrophe von 2008, als unglaubliche 11 Bergsteiger bei einem einzigen Ereignis ihr Leben verloren.

Vor diesem Hintergrund ist es sicherlich nur eine Frage der Zeit, bis es am K2, einem der gefährlichsten Berge der Welt, zur nächsten Katastrophe kommt. Leitbild: Dreamstime .

0 notes