#economic philosophy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Fun fact: none of us are real humans! At least, not by the standards of capitalism.

The wide range of skill sets demanded by employers is becoming more and more unmanageable as they try to make one person handle more and more elements of what could be multiple positions - not because it's efficient or healthy for the person doing it, but because it means the people at the top of the pyramid get more money that way.

Have you ever noticed that a company's "value" isn't based on how much money or product or employees they have? It's not about their power to do things, but about how much more money they might make next year in comparison to this year.

So next time you read "must be good at multitasking" in a job description, take a moment to reflect on how literally no human ever would be able to perfectly execute the duties of a job that could or maybe should be held by three people instead of just one.

Hot take: Many of the problems in modern life could be addressed and even eliminated if the aim of businesses was to improve the lives of customers and employees, instead of "make more money."

Money is only valuable because we assign it value. Life is inherently valuable because without it, we wouldn't exist.

they should invent a searching for jobs that doesn't open a miles-deep pit of despair and rage within me that gets deeper and wider with every scroll because it's all shit that is impossible for me to do because I am not a real human like other people

34K notes

·

View notes

Text

21K notes

·

View notes

Text

The American Left And Right Loathe Each Other And Agree On A Lot

Economic philosophy is not just changing—it is converging

— United States | U-shaped Economic Thinking | July 13th, 2023 | Washington, DC

Image: Tyler Comrie/Getty Images

Normally, you need read only the first six or seven words of a senator’s sentence to be able to correctly surmise his party. See if you can tell from the next 40 or so, an extract culled from a prominent senator’s recent book: “Today, neoliberalism is in. In the eyes of our elites, the spread and support of free trade should come before all other concerns—personal, political and geopolitical. In recent years this has led to a kind of ‘free-market fundamentalism’.” Suppose you were given a hint. The three proposed solutions for the neoliberal malaise are: “putting Wall Street in its place”, bringing “critical industries back to America” and resurrecting “an obligation to rebuild America’s workforce”.

If you guessed a Democrat—perhaps even more cleverly Bernie Sanders writing in his recent work, “It’s ok to be Angry About Capitalism”—you would be wrong. It was in fact Marco Rubio, the Republican senator from Florida and one-time presidential contender, writing in his just-published book, “Decades of Decadence”.

The populist era marked by Donald Trump’s ascension has been tumultuous for economic policy on both the American left and right. What was once heterodox has quickly become orthodox. It is easy to be drawn to where the new left and the new right are diametrically opposed, because partisans amplify disagreement, and because there are real differences on the role of policing, say, or whether pupils ought to be schooled in gender fluidity. What the culture wars distract from is that, on matters of economic policy, there is rather a lot of agreement. The culture wars may even have hastened the convergence between the two sides by quickening the break-up between the Republican Party and big business, which is now commonly derided as just another redoubt of wokeness.

The diagnoses from the new right and new left of what ails America are strikingly similar. Both sides agree that the old order that prized expertise, free markets and free trade—“neoliberalism”, usually invoked as a pejorative—was a rotten deal for America. Corporations were too immoral; elites too feckless; globalisation too costly; inequality too unchecked; the invisible hand too prone to error.

These problems, both sides agree, must be rectified by the state, through the use of tariffs and industrial policy to boost favoured industries. That should be coupled with greater redistribution, to the detriment of corporations and to the benefit of left-behind workers. When Jake Sullivan, the national security adviser, who is tasked with making something called “a foreign policy for the middle class” a reality, endorsed the idea that the administration’s domestic economic policies represented a “new Washington consensus” in April, he was speaking grandly but not incorrectly.

For wonks pushing in this direction, that is great news. “It is a sign of a healthy politics that you have people with their eyes open on both sides of the political spectrum saying, ‘This is really broken,’” says Oren Cass, a former policy adviser to Mitt Romney and now the executive director of American Compass, a think-tank leading the charge on the right. In June the organisation released an anthology of policy essays called “Rebuilding American Capitalism: A Handbook for Conservative Policymakers” that resembles a slaughterhouse for Republican sacred cows.

Trade deficits are obsessed over; federal budget deficits are hardly mentioned. Child benefits for parents should be made much more generous, as Democrats suggest, though only on the condition that parents work. Financial engineering should be resisted, with share buy-backs banned. Organised labour is to be encouraged rather than being dismissed as a hindrance. “Conservative economics, unlike the fundamentalism that supplanted it for a time, begins with a confident assertion of what the market is for and then considers the public policies necessary for shaping markets toward that end,” Mr Cass writes at the start of the manifesto.

This is apparently a catchy proposition. Most of the young guard of Republican senators who are trying to fashion populist economic policy—like Tom Cotton of Arkansas, J.D. Vance of Ohio and Todd Young of Indiana—gave lengthy interviews at an event to celebrate its unveiling. Mr Rubio was there, too; his recent book of recriminations against the decadent technocratic, neoliberal elite is studded with references to Mr Cass and his writings.

The idea that capitalism has inherent contradictions that require government intervention is more usually associated with the left. But Thomas Piketty, the famed French chronicler of inequality, is also optimistic that there is a broader ideological shift under way. “Beginning with the 2008 financial crisis, we’ve seen the beginning of the end of this sort of neoliberal euphoria and the pandemic accelerated this transformation,” he reckons.

Mr Biden is doing “interesting things” when it comes to industrial policy, says Mr Piketty—who freely admits his preference for the more revolutionary Democratic alternatives like Elizabeth Warren and Mr Sanders over the centrist Mr Biden. The president, he says, is “not really questioning the very high level of inequality that we have in the us today”.

This is a critique that those in the Biden administration might heed. There are more than a few casual fans of Mr Piketty in the White House. Heather Boushey, a member of the president’s Council of Economic Advisers, helped edit an entire volume of economic essays titled “After Piketty”. Even as a tight labour market after the pandemic increased wages for the lowest-paid workers, top incomes continued to rise, causing some measures of inequality either to rise or remain stuck at stubbornly high levels. Mr Piketty had called for a return to the high marginal tax rates on income in effect in the three decades after the second world war, as well as a new steeply progressive wealth tax to finance a generous welfare state.

This is one difference between new right and new left. Mr Biden has taken on board the idea that extreme wealth at the top of the distribution is a problem that needs tackling, and insists that he will not raise taxes on those earning less than $400,000 a year (98% of Americans fall below that threshold). Mr Cass and co spend less time fretting that the top 2% are doing too well. Though since Mr Biden has not managed to actually raise taxes on top earners, the difference is moot.

All of which leads Mr Piketty to worry that America could have a “neoliberal stabilisation” at a very high level of inequality, or continue to flirt with alternative systems like the “neo-nationalism” embodied by Mr Trump. He also worries that some of the leftish industrial policy that the Biden administration has championed, and which plenty of Republicans would copy, is in fact something more retrograde in disguise. “Some of what we call industrial policy today looks a lot like subsidies and sort of a new wave of tax competition and a race to the bottom,” he says.

Crossing the Piketty Line

Aside from the focus on the super-rich, the differences between the new left and new right on economic matters can be hard to detect. Those on the left often discuss social policy as something that happens between state and individual; the right insists that the family remain the intermediating institution. Both find competition with China to be a justification for industrial policy; but the new right does not find the threat of climate change to be nearly so moving. There is little appetite on either side to reform entitlement programmes before the trust funds that hold cash for old-age-pension and health benefits are depleted within the next decade.

Both the new left and the new right agree on empowering workers but disagree on the means. “The Democratic Party is just completely committed at this point to strengthening existing unions,” says Mr Cass. He prefers alternative ways of organising labour like sectoral bargaining, or a German-style co-determination system in which a set number of corporate-board seats are reserved for workers (an arrangement also praised by Mr Piketty).

If there is so much agreement, why is Congress not enacting more laws that reflect the new consensus? The main reason is that mutual suspicion on matters of culture, the primary currency of contemporary politics, infect whatever new economic consensus there is. A wholesale refashioning of America therefore won’t come soon. But the ideas are already proving to be more than a mere passing fad.■

— This article appeared in the United States section of the print edition under the headline "Frenemies"

#United States 🇺🇸#U-shaped Economic Thinking#Economic Philosophy#Democrat#Capitalism#Republican#Donald Trump#Neoliberalism#Marco Rubio#Washington#Tom Cotton#J.D. Vance#Thomas Piketty#Elizabeth Warren#Bernie Sanders#Joe Biden#China ���🇳#Frenemies

0 notes

Text

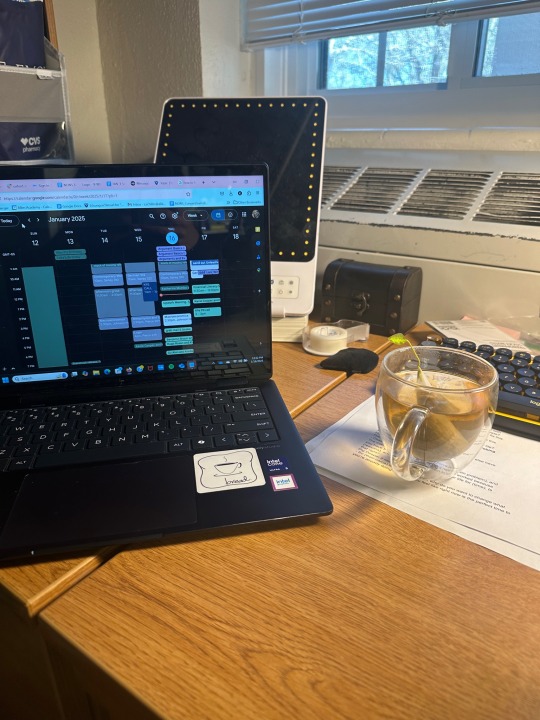

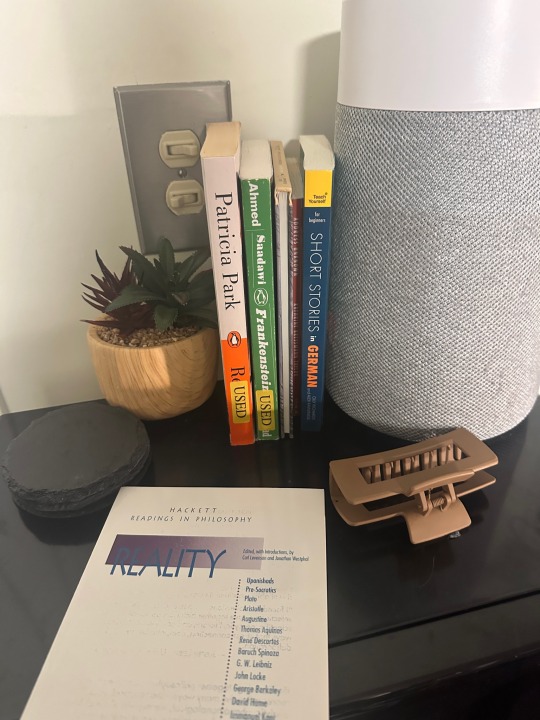

jan. 16, 2025—

-> all the green slots are calls

->write an article in 48 hours challenge. very possible.

->peep the bookshelf on top of the fridge (my required reading for this semester and then some)

->being this locked in gets lonely sometimes

->i'll post my schedule later

🌿Buyer's Remorse, That Handsome Devil

#studyblr#aesthetic#studying#studyspo#mathblr#100 days of productivity#dark academia#study#music#reading#copywriting#kimblestudies#kimblecore#metaphysics#philosophy#economics#logic

175 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Wherever there are politics or economics no morality exists.

Friedrich Schlegel, Ideas

709 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the funniest things about communism is that it rests on a premise that's basically like, "Hey, once everybody voluntarily gives up a specific set of strategies and advantages, everything will be wonderful. So, once we figure out how to coerce everybody into voluntarily giving those up, we'll be set."

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

The endless repetition of "marriage was an economic proposition" in discourse about 19th century lit is extremely annoying. Because in the strictest literal sense it is true... and also in the strictest literal sense it is almost tautological.

Marriage still is an economic proposition for both men and women. Whenever you pool resources (at whatever level of legal arrangement) with someone else, you are engaging in a significant economic proposition. Everything in life is economical, because we are physical beings living in a universe with limited resources and opportunity costs. Your most beloved hobbies are intrinsically economic because they involve the managing of finite resources and their transformation through labor that adds value to them.

Saying "hobbies are an economic proposition" does, however, come across as repugnant, because it reveals the unspoken implication of the original sentence: marriage was EXCLUSIVELY an economic transaction, understood in the most mechanicist, utilitarian way possible. And unless you are a convinced radical utilitarian and mechanicist, that rings untrue because most if not all other worldviews understand human action as much more complex, possessing moral, social, emotional and cultural dimensions that make them irreducible to one single aspect.

"Marriage was an economic proposition" is pseudo-intellectualism at its best.

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas, i.e. the class which is the ruling material force of society, is at the same time its ruling intellectual force. The class which has the means of material production at its disposal, has control at the same time over the means of mental production, so that thereby, generally speaking, the ideas of those who lack the means of mental production are subject to it. The ruling ideas are nothing more than the ideal expression of the dominant material relationships, the dominant material relationships grasped as ideas; hence of the relationships which make the one class the ruling one, therefore, the ideas of its dominance." - Karl Marx, The German Ideology

#politics#philosophy#socialism#sociology#communism#anarchy#marx#marxism#marxism leninism#anarchism#capitalism#anti capitalism#economics#economy#social justice#facts

203 notes

·

View notes

Text

The concept of antisocial behavior is strange. Are you telling me that you're spending the energy you have now in ways that destroy your opportunities to give or receive energy in the future? This seems like a losing strategy.

If you're so smart, why aren't you prosocial? Why haven't you realized that connection is the best part of life? And missing out on it is like missing the whole vibe.

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

"It seems to me to be equally plain that no business which depends for existence on paying less than living wages to its workers has any right to continue in this country. By 'business' I mean the whole of commerce as well as the whole of industry; by workers I mean all workers, the white collar class as well as the men in overalls; and by living wages I mean more than a bare subsistence level-I mean the wages of decent living." - Franklin D. Roosevelt.

His Statement on the National Industrial Recovery Act on June 16, 1933.

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

ᴏᴄᴄᴜᴘʏ ᴡᴀʟʟ sᴛʀᴇᴇᴛ poster created by Will Brown for 𝘼𝙙𝙗𝙪𝙨𝙩𝙚𝙧𝙨, 2011.

#occupy#chaos#anarchy#2010s#occupy wall street#nyc#politics#revolution#posters#economics#activism#protest#advertising#history#social justice#art history#kalle lasn#will brown#adbusters#philosophy#micah white#🐃

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I had to look up what it meant to get a 3rd in PPE (since that is apparantly the degree the original Elias Bouchard graduated with) but now I'm flabbergasted by the UK university level grading system (if I'm understanding it correctly). Do you mean to tell me that the highest level of honors degree only requires 70%??

#someone please explain this to me bc that... cant be what that means#of course if the og Elias only scored a 40-50% thats much more telling about the kind of person he was lol#also for anyone else who didnt know ppe is philosophy politics economics#tma#mag 49#the magnus archives#elias bouchard#uk schools

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

i must admit that i do not know what i want to know. im a sessile filterfeeder of information. im a sponge that wants to be a shark

#is ''i want to want to know'' an answer to ''what do you want to know''? feels like a regress type thing#postscript: this is about like. fields of knowledge. philosophy economics literature physics biology etc

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

But the monster also makes us realize that in an unequal society they are not equal. Not because they belong to different ‘races’ but because inequality really does score itself into one’s skin, one’s eyes and one’s body. And more so, evidently, in the case of the first industrial workers: the monster is disfigured not only because Frankenstein wants him to be like that, but also because this was how things actually were in the first decades of the industrial revolution. In him, the metaphors of the critics of civil society become real. The monster incarnates the dialectic of estranged labour described by the young Marx: ‘the more his product is shaped, the more misshapen the worker; the more civilized his object, the more barbarous the worker; the more powerful the work, the more powerless the worker; the more intelligent the work, the duller the worker and the more he becomes a slave of nature… . It is true that labour produces … palaces, but hovels for the worker… . It produces intelligence, but it produces idiocy and cretinism for the worker.’ Frankenstein’s invention is thus a pregnant metaphor of the process of capitalist production, which forms by deforming, civilizes by barbarizing, enriches by impoverishing – a two-sided process in which each affirmation entails a negation. And indeed the monster – the pedestal on which Frankenstein erects his anguished greatness – is always described by negation: man is well proportioned, the monster is not; man is beautiful, the monster ugly; man is good, the monster evil. The monster is man turned upside-down, negated.

— Franco Moretti, "The Dialectic of Fear."

Follow Diary of a Philosopher for more quotes!

#dark academia#quote#quotes#academia#gradblr#studyblr#book quotes#philosophy#chaotic academia#philosophy quotes#booklr#bookblr#monster theory#monstrous feminine#frankenstein#mary shelley#gothic literature#victor frankenstein#horror#horror genre#horror theory#social justice#inequality#poverty#capitalism#economics#working class#class warfare

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

OK. Part 2 for @hrovitnir.

Neoliberals of course don't quote Marx, and so they don't say "from each according to his ability, to each according to his need". But they do talk about "efficiency", which is when there's no waste and no shortage. They would claim that the market is the best way to achieve that.

Let's suppose we have a resource, and it's limited. That doesn't have to mean there's not enough of it to go around; it means that, if someone took as much as they could, then there wouldn't be enough to go around.

(Not all physical resources are limited in this way. Oxygen isn't, for example. Water might or might not be, depending on the local rainfall.)

But let's suppose our resource isn't controlled. There's nothing to stop anyone from taking as much as they want, except other people also taking what they want.

Contrary to the stereotype, neoliberals do not claim that everyone, in such circumstances, would be consumed by a frenzy of selfish greed. They point out, however, that it only takes one person who is, and then everyone else has no choice but to take whatever they can if they want to get any at all. Absent any kind of control, one selfish bastard fucks the entire system up for everybody.

So what kind of control can you place on resource distribution? There are four basic options:

a lottery, where the resource is distributed by chance;

a queue, where it's distributed to the first takers;

a triage, where a committee of experts decide who needs it most;

a market, where people signal their need by how much they're willing to trade for it.

Any communist-style planned economy is basically a form of triage. Now, no matter how expert your experts are, they're going to have to do serious data compression on the information they have to work with just to make it workable. They're going to produce standardized rules and procedures that don't take account of every individual's personal circumstances. Some people with rare needs are going to miss out, and some of the resource is going to be wasted on people who don't really benefit from it.

Therefore, neoliberals say, if your ideal is "From each according to his ability..." etc., the best way to get there is a free market. You're working with the same information as the triage, but you don't need to standardize and regularize. People who need the resource more will pay more for it, and people who don't need it won't buy it.

I am not allowed to ask questions in class; I can't give my student any advantage they wouldn't have if I wasn't there, except for their typed notes. I swear to gods, not one student thought to raise their hand and ask "What if people can't afford the resource at the market price? What if someone's 'willingness to pay' is high but their ability to pay is low?"

And because nobody asked it, I can't say with certainty how a neoliberal economist would answer it. In any case, it's a counter-argument, and I'm still leaving counter-arguments for somewhere further down the track.

I will mention, however, that in my first ECON lecture, they gave a familiar example of a queue in a modern economy: traffic lights. You wait to go until it's your turn, no matter how important it might be that you get to your destination on time. What if (said our lecturer) you're driving your kid to hospital and you desperately need to get there fast? As always, the market is the answer. Apparently there has been serious work done looking into the possibility of allowing drivers to speed up traffic lights in their favour by bidding in some kind of on-the-spot electronic micro-auction.

I for one immediately had this vision of a poor parent trying to get their kid to hospital, going one way, pitted against a bunch of rich douchebags going the other way with the kind of sense of humour that people must have who slow down for hitchhikers and then drive away again. (Perhaps -- let's be charitable -- that occurred to the researchers as well, and our lecturer just didn't elaborate because they were only giving an example in passing.)

They're completely serious about this. If you've ever wondered, this is the reason for that thing where rich people or organizations, instead of just donating money to a good cause off their own bat, will match (or double or triple) donations from other people. Those other people are the market deciding how important the cause is, you see. To just donate their own money would be to inappropriately take control away from the market.

How do neoliberals answer the charge that "Capitalism promotes selfishness and greed"? I'm not talking here about hard-line Randists who reply "What's wrong with selfishness and greed?" They exist, and they tend to be loud about it, but they're not the ones who have centrist politicians' ears.

Moderate neoliberals reply that capitalism is not meant to replace economic interactions like helping out one's neighbours or family. Of course it's a good thing for people to give generously to their community. The problem is that this kind of interaction doesn't scale up very well. Not everyone is your neighbour or family.

At some point, you're going to find yourself faced with a complete stranger who has something you need, and you're going to have to decide how to get it off them. And they're not going to be sticking around for you to form a relationship of trust with over time. Your options to get the thing you need are (1) trade and (2) violence. Trade is better.

That still sounds selfish, doesn't it? But the thing is, it doesn't have to be something you need for yourself. Let's suppose it's the zombie apocalypse, and you have a diabetic child to look after. They're nearly out of insulin, and you run into someone who has a big stash of it. Precisely because you are altruistic, precisely because you selflessly care for that child, you're going to be tempted to commit an act of violence to steal some of that insulin.

And perhaps you could justify it on the grounds of "why are they hoarding all that insulin?" -- but perhaps they have diabetic family members to look after too. And you could say "Well then, we should just be friends and share," but they don't know that you're not an evil person wanting to steal all their insulin and hoard it.

That covers all the bullet-points, at least. I hope it gives you a feel for the way neoliberals think. Next time, if there is a next time, I'll start on where the problems actually lie in their philosophy.

Kia ora! I followed you before even realising you were from Aotearoa. ^_^ Ko Ngāti Whakaue te hapu. Nō Ōtautahi me Pōneke au. Kei Ōtepoti tōku kāinga ināianei. Just sending a request for elaboration if you care to on your pretty fantastic point from the post re: insulating ourselves from right-wing viewpoints.

"Capitalism promotes selfishness and greed."

"Value is created by labour. Profit is theft."

"From each according to his ability, to each according to his need."

"Reducing all value to monetary value is soulless and shallow."

"You can't earn a billion dollars."

At the very least, leftists need to become aware of the neoliberal answers to these, and start coming up with better counter-arguments.

Kia ora, e hoa. He Pākehā au. Kei Ōtepoti tōku kāinga hoki -- te hia te oruatanga!

I'm probably going to have to spread this out over a bunch of reblogs, but it's going to go quicker if I start by explaining neoliberal economic theory once to begin with, rather than going point by point.

The first premise is that value is subjective. Different things are valued differently by different people, and no-one is wrong about their own valuation of something.

This subjectivity is the foundation of all economic transactions. Economic value is created by the differential between two different people's valuation of a good or service.

Let's say you buy a coffee for $5, and let's say you do so freely. You wouldn't do that if that coffee was worth less than $5 to you. But the sale also wouldn't happen if the coffee was worth more than $5 to the seller.

Just for the sake of argument, let's say that if that coffee had cost $6 you would still have bought it, but if it had cost over $7 you would have gone elsewhere. Then that coffee is worth $7 to you.

Meanwhile, the seller would (hypothetically) be willing to lower their price if they weren't getting enough customers, but let's say only down to $2 a coffee. So the coffee is worth $2 to the seller.

In this scenario, you've paid only $5 for something that's actually worth $7 to you. You've gained value equal to $7 - $5 = $2. The seller, meanwhile, has been paid $5 for something that's only worth $2 to them. They've gained value equal to $5 - $2 = $3. You're both richer, in terms of total value enjoyed, than you were before you bought the coffee. A total of $5 in surplus value has been created out of nowhere, simply by the act of buying and selling.

I've described this transaction in terms of a dollar price, because that's an easy way to talk about value, but it's important to note that the logic works just the same if you're exchanging goods and services directly for other goods and services. If you don't have $5 but you're willing to wash dishes for half an hour in exchange for your coffee, then by definition that coffee is worth more to you than that half-hour of your time.

That, by the way, already illustrates another foundational principle: value is measured by what people are willing to exchange for it. People can talk all they like about what they want and what's important to them, but if they're not willing to put anything on the line, then it's just talk.

What we've seen so far already gives you the neoliberal answer to a couple of our bullet-points:

"Reducing all value to monetary value is soulless and shallow." -- the neoliberal economist would answer, if you're not willing to pay for something, if you're not willing to give anything up for it, then it is your claim to still "value" it in some sense that is shallow.

"Value is created by labour. Profit is theft." -- to unpack that a little, the difference between the sale price of a good and the production cost to make that good is created by the worker's contribution. The economist will answer, no it's not; it's created by the fact that the buyer values the good more than the maker does.

Workers willingly come in to work and exchange their labour for the wage they're offered; their acceptance demonstrates, by definition, how much their time and energy is truly worth to them. Selling labour to an employer is exactly the same as selling goods to a customer; once sold, the customer owns the goods and is free to do what they like with them, including sell them at a higher price.

(I imagine you can already see at least one of the major problems with this theory; but I'm going to leave counter-arguments for a later reblog.)

Also: "You can't earn a billion dollars." -- the economist would answer that if people are willing to pay you that much money, then by definition whatever you do for them is worth that much money. Provided, of course, that they're fully aware of what they're buying when they agree to buy it.

But if value is subjective, you might be asking, why do economists talk so often as if things had a "true" value or a "correct" price? That's where the market comes in.

Leftists love to use "market" as a word of scorn, but to neoliberals "the market" is simply -- people.

Let's go back to that $5 coffee. If you're only willing to part with $1 for a coffee, you're out of luck. The seller is not willing to sell at that price and the coffee will go to someone else, someone who is willing to pay $5. Contrariwise, if the seller asks for $8, they're not going to get many customers, and people will go buy someone else's cheaper coffee.

If the price is too high, some sellers won't find buyers; the coffee will go unsold, and it will be wasted. If it's too low, some buyers won't find sellers; the coffee will all be snapped up by the first lot of customers to get there, regardless of whether they're the ones who valued the coffee highest, and there will be a shortage. Either way, some surplus value which could have been created, won't be.

But in a free market, customers can choose whose goods to buy, and sellers can choose what price to sell their goods at. Mathematically, the price which will generate the most profit for the sellers is also the price which creates the most total surplus value for sellers and buyers alike, thus minimizing both waste and shortage. That's what's called the market price.

Remember, surplus value -- in neoliberal theory -- is basically people getting what they want. The ideal situation is for the greatest possible number of people to get the greatest possible amount of what they want. That's the same thing as creating the greatest possible surplus value across the economy.

I've already pointed out one of the problems with this aspect of the theory in a reblog of the earlier post. But again, I'll come back to counter-arguments at a later time.

In fact I think I'll wrap up here for now, because this post is already getting megabig. I haven't covered everything yet, but I'm going to save it for next time.

However, this is an ideology which is sincerely and seriously believed by people some of whom are very intelligent. Which means it's important not to underestimate its allure. So to counter that, I do want to impress upon you that according to this ideology, the best possible outcome for any situation is by definition that which is determined by the market, human consequences be damned.

If the market deems that climate disaster is better than cutting back on fossil fuels, then climate disaster is better than cutting back on fossil fuels. If the market deems that millions dying of Covid is better than lockdowns and mask mandates, then millions dying of Covid is better than lockdowns and mask mandates.

Just bear that in mind.

5 notes

·

View notes