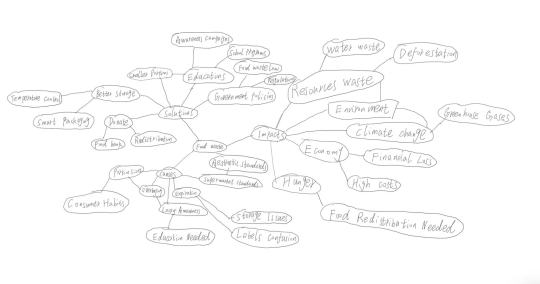

#economic impact of disposability

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

Rethinking Our Disposable Culture: How to Spend Wisely and Sustainably in the 21st Century 🌍💚

As we delve deeper into the 21st century, our society stands at a crossroads. The path we've been on—characterized by a growing throwaway culture fueled by increased disposable income—is unsustainable. It's time to consider how we might turn the tide.

The Economics of Disposability

Disposable income has undoubtedly improved living standards for many. Yet, this financial flexibility has also led to an increase in disposable products, fast fashion, and rapidly obsolete technologies. This trend is economically beneficial in the short term but environmentally and socially detrimental in the long run. 📉🌎

Rethinking Consumption

To mitigate the impact of throwaway culture, a shift in consumer mentality is essential:

Value-Based Spending: Align your spending with your values. If sustainability matters to you, support brands that prioritize eco-friendly practices.

Invest in Repairability: Choose products designed for longevity and that can be easily repaired, reducing the need to buy new.

Community Engagement: Get involved in or start local initiatives that promote sustainable living, from community gardens to tool-sharing libraries.

Policy and Change

Policy change can also drive significant shifts. Advocating for regulations that require producers to be responsible for the lifecycle of their products can decrease the volume of waste generated.

By adjusting how we view and utilize our disposable income, we can combat the rise of throwaway culture. It's about creating a future where we value what we own, understand the true cost of disposability, and choose a sustainable path forward. 🌍💚

Each of these posts could be adapted for platforms like WordPress, Medium, and Tumblr, considering the audience's preferences and engagement styles on each. For WordPress and Medium, a more formal and informative tone can be used, while Tumblr allows for a more casual and direct conversation style, incorporating relevant images, gifs, and interactive elements to engage the readers effectively.

#disposable income#throwaway culture#sustainable spending#environmental impact#consumer habits#financial literacy#eco-friendly products#waste management#economic impact of disposability#minimalism#reduce waste#responsible consumption#recycle and reuse#sustainable living#impact of consumerism#throwaway society#saving money#environmental responsibility#reducing landfill waste#ethical spending#Youtube

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm writing a sci-fi story about a space freight hauler with a heavy focus on the economy. Any tips for writing a complex fictional economy and all of it's intricacies and inner-workings?

Constructing a Fictional Economy

The economy is all about: How is the limited financial/natural/human resources distributed between various parties?

So, the most important question you should be able to answer are:

Who are the "have"s and "have-not"s?

What's "expensive" and what's "commonplace"?

What are the rules(laws, taxes, trade) of this game?

Building Blocks of the Economic System

Type of economic system. Even if your fictional economy is made up, it will need to be based on the existing systems: capitalism, socialism, mixed economies, feudalism, barter, etc.

Currency and monetary systems: the currency can be in various forms like gols, silver, digital, fiat, other commodity, etc. Estalish a central bank (or equivalent) responsible for monetary policy

Exchange rates

Inflation

Domestic and International trade: Trade policies and treaties. Transportation, communication infrastructure

Labour and employment: labor force trends, employment opportunities, workers rights. Consider the role of education, training and skill development in the labour market

The government's role: Fiscal policy(tax rate?), market regulation, social welfare, pension plans, etc.

Impact of Technology: Examine the role of tech in productivity, automation and job displacement. How does the digital economy and e-commerce shape the world?

Economic history: what are some historical events (like The Great Depresion and the 2008 Housing Crisis) that left lasting impacts on the psychologial workings of your economy?

For a comprehensive economic system, you'll need to consider ideally all of the above. However, depending on the characteristics of your country, you will need to concentrate on some more than others. i.e. a country heavily dependent on exports will care a lot more about the exchange rate and how to keep it stable.

For Fantasy Economies:

Social status: The haves and have-nots in fantasy world will be much more clear-cut, often with little room for movement up and down the socioeconoic ladder.

Scaricity. What is a resource that is hard to come by?

Geographical Characteristics: The setting will play a huge role in deciding what your country has and doesn't. Mountains and seas will determine time and cost of trade. Climatic conditions will determine shelf life of food items.

Impact of Magic: Magic can determine the cost of obtaining certain commodities. How does teleportation magic impact trade?

For Sci-Fi Economies Related to Space Exploration

Thankfully, space exploitation is slowly becoming a reality, we can now identify the factors we'll need to consider:

Economics of space waste: How large is the space waste problem? Is it recycled or resold? Any regulations about disposing of space wste?

New Energy: Is there any new clean energy? Is energy scarce?

Investors: Who/which country are the giants of space travel?

Ownership: Who "owns" space? How do you draw the borders between territories in space?

New class of workers: How are people working in space treated? Skilled or unskilled?

Relationship between space and Earth: Are resources mined in space and brought back to Earth, or is there a plan to live in space permanently?

What are some new professional niches?

What's the military implication of space exploitation? What new weapons, networks and spying techniques?

Also, consider:

Impact of space travel on food security, gender equality, racial equality

Impact of space travel on education.

Impact of space travel on the entertainment industry. Perhaps shooting monters in space isn't just a virtual thing anymore?

What are some indsutries that decline due to space travel?

I suggest reading up the Economic Impact Report from NASA, and futuristic reports from business consultants like McKinsey.

If space exploitation is a relatiely new technology that not everyone has access to, the workings of the economy will be skewed to benefit large investors and tech giants. As more regulations appear and prices go down, it will be further be integrated into the various industries, eventually becoming a new style of living.

#writing practice#writing#writers and poets#creative writing#writers on tumblr#creative writers#helping writers#poets and writers#writeblr#resources for writers#let's write#writing process#writing prompt#writing community#writing inspiration#writing tips#writing advice#on writing#writer#writerscommunity#writer on tumblr#writer stuff#writer things#writer problems#writer community#writblr#science fiction#fiction#novel#worldbuilding

304 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ko-fi prompt from IndigoMay:

What would be the economic impact if people could magically grow whatever food they liked? Including fodder for animals.

This is a very wide-ranging question, like... when was the magic introduced? What was the state of agriculture before that? Is this food generated from existing matter, delivered by gods, or something else?

I'm going to narrow this to:

What would happen if people could, starting tomorrow, grow any plant...

That is edible, by either humans or livestock, with appropriate treatment.

Without delay, meaning that the time sink is several minutes instead of weeks or months.

Without concerns for weather or other natural dangers like fungal infections or pests, or requirements for water or fertilizer.

Without depleting soil nutrients, so long as they have arable land to work with.

Without relying on fresh seeds or other 'raw ingredients' like leaf cuttings.

Well... let's start small.

Personal Basis - people who are not farmers

People who do not normally grow things would start angling to acquire some kind basic gardening implements. For some, like those who live in the suburbs, this would be as simple as going into the backyard. For those in cities, they'd need to get a window box or similar to use. If you have free, guaranteed fresh plant matter, that's already a good thing, but the time and care required to keep a garden alive is more than some people can manage due to work or children or housing. With immediate food that requires minimal effort, a lot of those hurdles are removed. You can grow the two tomatoes you need for dinner, and then put the pot of soil away for tomorrow.

The cost of

Personal Basis - small farmers

The obvious impacts for those who are small farmers is that people are less likely to buy their raw ingredients. Most of these small farmers would start looking into modifying their operations to do things that require processing.

Growing apples in your house for a snack is fine--if you have a pot big enough for a small tree, and a way to dispose of the wood if it's a one-time thing--but if you want applesauce or cider or pie, someone who knows how to cook or bake needs to do that part. You can grow wheat, but your chances of having the necessary tools to grind flour are slim. You can grow cashews, but fuck knows how you're going to process that without poisoning yourself! You can grow grapes on your trellis, but that doesn't mean you have the knowledge to make wine without accidentally going straight to vinegar. You can grow corn, but that doesn't mean you know the best way to dry it to make popcorn.

So small farms shift to those products that either need processing, or are part of an animal-based food. This includes things like flowers for bees. You can't really control bees, so just 'grow and go' might incite the bees to leave somehow. Maybe they can sense magic! Who knows!

Another option would be to focus on unique or heirloom things. If you go to a farmer's market, you might be going just to see all the fruits you've never encountered before. If there's an apple stand one year, and suddenly you can grow your own apples at home, then maybe what they start doing is growing unique or rare cultivars that you've never heard of, and that's their new niche. It's not that you can't grow the apples, but would you grow them if you've never heard of them? Plus, the apple stand is doing sauces and ciders now.

Mid-tier and large farms

These farms will start to focus in on large-scale crops that don't go straight to tables or cooking pots in homes. Scrap the eggplants, the cucumbers, the blueberries. Focus on:

Fruits and vegetables that are needed for popular secondary products, like tomatoes (ketchup, marinara), or oranges (juice), or corn (anything with fructose corn syrups, popcorn).

Plants that are popular but NEED processing to be edible, like coffee beans, cocoa beans, or wheat, that most people just don't have.

Plants that are needed in massive quantities for animal feed, such as alfalfa or chicken grains.

Now, I think these large farms would still be in production. We'd see a massive reduction in water usage, which is great (except for cranberries, I guess), but many of these products would still be needed in quantities that need industrial levels of processing. Someone needs to pick the oranges, to drive them to the juicing facility, the facility needs to juice and treat and preserve and bottle them, and then that needs to be driven to the store. The reduced time to grow, reduced water usage, reduced waste from natural predators or dangers, and general ability to plan things more efficiently would result in lower costs for many of these products in a truly free market... but would possibly also rise in cost as companies try to maintain a consistent flow of profit.

Sure you can make the juice at home, but what if you're already at work? There's still a demand for products; most of us can get water from a tap at home, but there are still convenience stores selling bottled water on every other corner in a big city.

I think the most interesting of these concerns would be grazing animals, like sheep, cattle, and goats. Being able to 'refresh' the grass of a single field without having to rotate the animals to new pastures once they've eaten away at one, and without damaging the nutrient profiles of the one they're staying at, means reduced deforestation or soil destabilization in agricultural areas. We'd see a fairly significant stalling of things like the decimation of Mongolia's grasslands if the goats didn't need as much grazing land.

Maintaining the meat industry would be one of the most constant sources of demand for large-scale agriculture, given that other products could go through cycles to more efficiently use land. You can grow and harvest oranges for Tropicana on Monday, grapes for Welch's on Tuesday, soy beans for Silk on Wednesday, tomatoes for Heinz on Thursday, and so on. They probably won't need more than they used to.

Meanwhile, the cows gotta eat. And eat. And eat.

Corporations

This one is fun! MONSANTO'S GONNA BE PISSED.

So, magically growing food, you don't need seeds, at least in this case. Or you can coax more product out of a seed you already have planted. You've gotten eight cycles corn out of this one stalk this season!

So Monsanto loses some of that insane seed monopoly situation.

You'd see a decrease in pesticides and anti-fungal products as agriculture speeds up a cycle by enough to prevent the spread of dangerous infestations. It's not going to kill your entire farm if you find fungus one day and have to burn it to prevent the spread. You lost one day's profit, not a full year's.

This impacts Monsanto too. Remember the Roundup debacle?

Now, to be clear, there are still plants that will rely on pesticides and anti-fungals. The premise only covers food, after all, so there are still important plants that will need longer, dedicated growing seasons.

Industry-wide shifts

Sooooooooooo a lot of the money starts to come from non-edible plants. This is your cottons, linens, hemps, latex/rubber trees, cork trees, lumber, and so on.

As the needed arable land necessary to feed humanity (and our livestock) decreases, more land is freed up for return to indigenous peoples, reclamation by nature, usage for alternate cultivation, housing, or... well, other capitalist ventures, like bitcoin mining or whatever.

On a geopolitical level, this causes some interesting shifts in places that draw their power from being 'breadbasket' nations. For instance, if you remember the start of the Russo-Ukrainian war, we saw some major pressures being placed by virtue of some countries (e.g. Lebanon, Pakistan) getting most of their wheat from Ukraine, and the war suddenly cutting off a massive portion of how they fed their people. Much of Ukraine's support, in those early days, derived from their importance as a breadbasket nation. If everyone can grown their own food, that moves the lines. Countries that are poor on space or water can stop relying on trade to survive in terms of water. Countries that rely on their agriculture to be able to trade for other things need to diversify their economies, and fast.

(Does mean that Saudi Arabia can stop using Arizona's water, though.)

The greatest shifts would come down to water usage and pollution, I think. Agriculture is currently one of the biggest contributors to the climate crisis, and the reduction of water use by farming would be a massive help. However, I'm less sure of how we'd see meat consumption change. The greater availability of fresh fruits and vegetables could result in a shift towards more plant-based diets worldwide, but just as easily we could see large agricultural corporations (and those that rely on them, like John Deere or the aforementioned Monsanto) market meat to consumers as a greater rate due to the profit margin.

Oh, also, I have a feeling that a lot of those corporations would try to get garden centers shut down, or buy out ceramic pot and planter factories. If you can't grow anything at home because you don't have a window planter, you have to buy from the store, right?

#ko fi#ko-fi#ko fi prompts#phoenix talks#magic#agriculture#microeconomics#macroeconomics#politics#environmentalism#water usage#pollution

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay I need honesty, do I sound fucking insane. like do I sound crazy. like do I sound cookoo dumb stupid crazy ass who should delete this and stop wasting their time on this or like am I making some snse

‘The pedophile’ is a scapegoat and boogeyman. It is an individualist, carceral, and fascist framing of childhood and adolescent sexual abuse. The individualist nature of this widely-accepted phenomenon functions to provide cover to the material basis that allows and creates such abuse, and is beloved by fascists for its malleability and galvanizing effect. Individual and carceral solutions are fundamentally incapable of stopping sexual abuse; if we truly care about the issue, we must abandon these frameworks altogether.

What is ‘the pedophile’ as a framework?

‘The pedophile’ is an attempt to provide anatomy of the problem. In this view, the cause is simple: for whatever reason, there exist a number of intrinsically sick, or more likely, evil individuals who lust after children and adolescents and make it their life��s goal to rape and defile them. With this framework, the solution is just as simple–dispose of the problemed people. If something about them is incurably evil, then what else is there to be done?

I understand the appeal of this framing to the majority that buy into it; a few years ago, I was caught up in the fervor myself. It’s a fairy tale; there exists a possibility of a ‘happily ever after.’ Evil is singular, and discreet from the world around it. The question of ‘why did they do it’ is conveniently irrelevant and inexplicable–evil is evil because it is evil; we must only know that it is evil and we (who could never be evil) must expel it.

Unfortunately, evil does not exist. But harm does, and harm is necessarily based in the material, not the moral, or spiritual, or metaphysical. Material results have material causes–that is to say, there are ‘whats,’ ‘whys,’ and ‘hows’ to every meaningful harm.

First, the ‘what’: What happened, and what detrimental material impact did it have?

Second, the ‘why’: Why might the person who did the harm have done so?

Third, the ‘how’: How was the harm made possible?

To view sexual abuse in terms of ‘bad people do bad things,’ we shut down the second question with the thought-terminating idea of evil, and entirely ignore the third question. By doing this, we fully close ourselves off from any ideas that could meaningfully deal with the issue outside of individual instances of it. If we don’t know how harm comes to pass, we are utterly powerless to stop its furtherance.

Childhood sexual abuse, like all forms of abuse, is made possible through unequal relationships to power. To understand this, we must understand ‘the family,’ the role of children within it, and the way capitalist society uses the family as an economic unit.

What is ‘the family’?

‘The family’ is capitalist society’s primary organizational method through which individuals meet their material needs. No matter a society’s methods of distribution, it is labor that is the animating essence of survival. Food must be cooked, children must be raised, waste must be taken out, and in a capitalist society, labor power must be sold so that the rent gets paid and the cabinets stay stocked.

Ignoring the production chains that produce the commodities that are foundational to our lives, it is exceedingly difficult to run a household single-handedly. If someone is not able to leave a situation because they would lack the financial means to subsist otherwise, the person providing those financial means holds power over them. This is a neutral

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

How To Deal With 'Fans' If You Have a Celeb SP 👀

You're in control of your reality, first and foremost. Your person also only wants you. That's it.

But should shit get to you one day, here's some reminders approached from a business-like and detached perspective:

They are lining your sp's pockets. That BTS-fandom rich emotional currency that creates the memes, fanfiction, sold out shows, and economic demand in real time is just making your person richer. Think about how they're gonna spend all of that on you. Fan devotion is excellent soil to plant your dreams in.

Anyone who seems really obsessed, even if they're a spiritual girlie who thinks they have a connection w/ them will not have them in your reality. But you need to be firm on that. No one is going to successfully 'manifest away' your person unless you think it's possible. You need to start thinking of yourself as their only choice.

Said fans are in love with a projection of them. It's their industry image that's palatable and carefully tweaked to appeal to specific demographics. This also may sound harsh but most of those fans will not think they can successfully or functionally be with them. They believe in social limitations and work with limits you've decided you don't have. You will be in the 'unrealistic' 1%. They will not.

Super locked-in and obsessed fans will eventually get bored and stop wanting your sp or won't as intensely. The real world's going to get more demanding, lifestyles and obsessions change, and they will inevitably focus on something or someone else. Gen Z's attention span is notoriously short and non-committal. Someone that seems like a fandom vet can stop updating their socials at random because of work, school, etc.

Even stalkers, saesangs, etc, inevitably get bored or have real life obligations. Putting that much energy into being a criminal, weirdo, etc will take a toll on their mental health sooner or later. From a safety pov when manifesting, imo, I like to think of them from a human view so I can minimize/prevent any harm they can do in my reality. Even if you're unmedicated and running on fumes, your obsession w/ a celeb will negatively impact your health, funds, relationships, and is not sustainable long-term. Therefore, I don't consider any creeps in my sp's life to be effective enough to cause harm of any kind. It's good to think of your relationship as a fortress they can't penetrate. They don't have the energy or disposable income like the girls used to bc of the global economy lmao. Just keep some safety affirmations on deck and you're fine.

Like I've said, their negative assumptions work to your advantage. That's why I said before that most creep behavior won't be seen positively by your sp w/ them bc they're terrified they'd hate them. They're insecure, don't think they have a chance with them, that they're out of their league, and all of these limiting ideas that industries concoct for money. All of this is working for you. That's a home-grown defense.

But you need to pair that with reminding yourself of how in love with and infatuated your sp is with you and no one else. This is why, imo, so many wives married to famous men wind up with infidelity. Despite being chosen, they still thought there'd be someone waiting in the wild to snatch their men up..and it'd inevitably happen. They had incredibly limiting beliefs about their men and assumed that because, 1, they're men, and 2, limitless access to women as an option meant they'd automatically go for it. So you need to get your boss bitch game up and start reveling in how amazing your person is and how they'd choose you over a million ig models or groupies. You need to think of yourself as the magical exception at all fucking times. You are a unicorn. Act like it!

IF YOU DON'T THINK YOU ARE THE EXCEPTION, YOUR CELEB SP WON'T EITHER!

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let me start with the following principle: “Energy is the only universal currency: One of its many forms must be transformed to get anything done.” Economies are just intricate systems set up to do those transformations, and all economically significant energy conversions have (often highly undesirable) environmental impacts. Consequently, as far as the biosphere is concerned, the best anthropogenic energy conversions are those that never take place: No emissions of gases (be they greenhouse or acidifying), no generation of solid or liquid wastes, no destruction of ecosystems. The best way to do this has been to convert energies with higher efficiencies: Without their widespread adoption (be it in large diesel- and jet-engines, combined-cycle gas turbines, light-emitting diodes, smelting of steel, or synthesis of ammonia) we would need to convert significantly more primary energy with all attendant environmental impacts.

Conversely, what then could be more wasteful, more undesirable, and more irrational than negating a large share of these conversion gains by wasting them? Yet precisely this keeps on happening—and to indefensibly high degrees—with all final energy uses. Buildings consume about a fifth of all global energy, but because of inadequate wall and ceiling insulation, single-pane windows and poor ventilation, they waste at least between a fifth to a third of it, as compared with well-designed indoor spaces. A typical SUV is now twice as massive as a common pre-SUV vehicle, and it needs at least a third more energy to perform the same task.

The most offensive of these wasteful practices is our food production. The modern food system (from energies embedded in breeding new varieties, synthesizing fertilizers and other agrochemicals, and making field machinery to energy used in harvesting, transporting, processing, storing, retailing, and cooking) claims close to 20 percent of the world’s fuels and primary electricity—and we waste as much as 40 percent of all produced food. Some food waste is inevitable. The prevailing food waste, however, is more than indefensible. It is, in many ways, criminal.

Combating it is difficult for many reasons. First, there are many ways to waste food: from field losses to spoilage in storage, from perishable seasonal surpluses to keeping “perfect” displays in stores, from oversize portions when eating outside of the home to the decline of home cooking.

Second, food now travels very far before reaching consumers: The average distance a typical food item travels is 1,500 to 2,500 miles before being bought.

Third, it remains too cheap in relation to other expenses. Despite recent food-price increases, families now spend only about 11 percent of their disposable income on food (in 1960 it was about 20 percent). Food-away-from-home spending (typically more wasteful than eating at home) is now more than half of that total. And finally, as consumers, we have an excessive food choice available to us: Just consider that the average American supermarket now carries more than 30,000 food products.

Our society is apparently quite content with wasting 40 percent of the nearly 20 percent of all energy it spends on food. In 2025, unfortunately, this shocking level of waste will not receive more attention. In fact, the situation will only get worse. While we keep pouring billions into the quest for energy “solutions”—ranging from new nuclear reactors (even fusion!) to green hydrogen, all of them carrying their own environmental burdens—in 2025, we will continue to fail addressing the huge waste of food that took so much fuel and electricity to produce.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

btw, if you're looking for a reason why so many movies have underperformed or bombed at the box office in recent years, regardless of actual quality

we're still dealing with the aftermath of a pandemic that shut down the entire fucking world for like 2 years

not to mention a financial crisis caused by said world altering plague that has left people with considerably less disposal income from before

The COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting economic recession had a devastating impact on the movie industry that it has not recovered from

#also the virus never went away btw#it's still very much a thing#no matter how much we want to pretend otherwise

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Starbucks is reducing its corporate employees’ holiday bonuses by 40% due to declining sales and financial struggles.

Key Facts:

– Bonus Cuts: Corporate staff will receive only 60% of their usual holiday bonuses this December. – Sales Slump: The company experienced its worst year since 2020, with revenue increasing less than 1% and operating income dropping 8%. – Customer Cutbacks: Cash-strapped customers are spending less on expensive menu items amid rising prices. – Operational Issues: Long wait times and controversies have further impacted customer satisfaction and sales. – Leadership Changes: New CEO Laxman Narasimhan is implementing strategies to revitalize the brand and regain customer trust.

The Rest of The Story:

Starbucks is facing significant financial challenges, prompting a substantial cut in holiday bonuses for its corporate employees. The company’s revenue growth has stalled, and operating income has declined, marking its most challenging year since the pandemic began. Customers are scaling back on premium beverages due to increased prices, leading to a slump in sales. Additionally, operational hurdles like lengthy wait times and public controversies have strained the company’s relationship with its clientele.

In response, CEO Laxman Narasimhan, who took over in September, is spearheading initiatives to rejuvenate the brand. These include hiring more baristas to improve service efficiency and redesigning store spaces to make them more inviting, reminiscent of Starbucks’ early days as a “third place” between work and home. Despite these efforts, employees at various levels are feeling the impact of the company’s financial downturn through reduced bonuses and halted merit raises for senior staff.

Commentary:

The financial woes of Starbucks are a reflection of the broader economic challenges many Americans face today. High inflation, often attributed to current economic policies, has eroded purchasing power, leaving consumers with less disposable income for non-essential luxuries like a $5 latte. The concept of “Bidenomics” has been criticized for contributing to rising costs of living, making it harder for average people to justify spending on premium-priced coffee when budgets are tight.

Moreover, the steep prices at Starbucks have long been a point of contention. In an era where every dollar counts, consumers are opting for more affordable alternatives or skipping the coffee shop altogether. This shift in consumer behavior underscores the need for economic policies that alleviate inflationary pressures and help restore financial confidence among the populace.

Looking ahead, there’s optimism that future leadership changes at the national level could steer the economy in a more favorable direction. Pro-growth strategies and fiscal policies aimed at curbing inflation could rejuvenate consumer spending. Such economic revitalization would not only benefit companies like Starbucks but also provide much-needed relief to consumers feeling the pinch of current economic strains.

The Bottom Line:

Starbucks’ decision to cut employee bonuses highlights the challenges businesses face amid economic hardships and shifting consumer behaviors. Addressing the root causes of these financial struggles is crucial for both the company’s recovery and the broader economic well-being.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Existential Trash: Tropes and Cliche

Ok so I’m gonna talk about waking up in a dump. By which I mean I’m going to talk about narrative strategy and game design and why tropes aren’t necessarily cliches.

When V wakes up in the dump in Cyberpunk 2077, we crawl forward through trash. The game doesn’t overstay its welcome with this. It does exactly what it needs to do in order to drill home that V is a fighter and something has gone even more wrong than we knew. At the same time, V’s literal disposability is bluntly illustrated. This is what waking up in the trash heap is for after all. It’s why Markus wakes up in the trash in DBH as well. One of these games is using tropes intelligently and one is reducing them to cliche.

V’s story is immediately and gracefully linked with Takemura’s and simultaneously builds the world in meaningful ways. We get visceral payoff of everything we’ve done thus far, from our own betrayal, to Arasaka’s power in this world, to Takemura’s character, to V’s personality, to foreshadowing the entire plot of the game. Nothing happens that hasn’t been set up and earned. It’s economical and graceful storytelling.

In DBH, we spend an excruciating amount of time stumbling around looking for components. This would be fine if the approach here were less scripted and redundant and padded with DBH’s preoccupation with horror cliche. The hands don’t grab Markus for any reason other than to be creepy. They aren’t creepy. Markus makes the same choice in the same way (kill or spare) twice. Watching androids struggle through the garbage heap is pathetic (in both senses of the word), but the impact is blunted by these redundancies and poor scripting. The chapter pacing and order likewise impedes momentum. In contrast, the scripted sequence in Cyberpunk 2077 is there following a heavy action sequence and preceding the main body of the story. It’s purposeful in its storytelling with every frame working on multiple levels. We learn more about Takemura’s psychology and motivation here than we ever truly know about Markus. I’m making a point here that I make a lot: you can do anything; it’s how you do it that matters.

With Markus, we haven’t earned the deployment of these tropes, and there is no payoff in terms of narrative or gameplay for suffering the tedium of the scripted event. The plot simply moves because we need it to. Markus finds a convenient jacket and all the parts he needs because we need to get through this section. It echoes the overall issue with deviancy in this game, which is at its worst with Markus. Connor’s slow path to deviancy provides a certain level of buy-in for the player. We see errors and conflicts chipping away at his ‘machine’ nature, and deviancy is framed as an actual choice. He can choose to stay machine, explicitly, as a rejection of the entire process. This is part of why the buddy cop drama works better than the rest of the game (the other part being Clancy Brown improving whatever he touches). Back to Markus: deviancy here is reactive. It’s something that happens to him in much the same way it seems to happen to Kara. Here, I could be a smartass about a black man and a woman being framed as reactive victims while the white guy gets actual agency, but I’m gonna keep it moving. Markus makes the same choice twice because we aren’t actually interested in telling a story that centers his perspective so much as we want to move the player along the plot. This is what we literature and film dorks mean when we say something hasn’t earned its emotional beats. Markus is a nascent savior figure because DBH is trying to swim in waters that are far too deep for its writers. We’re beat over the head with androids as a clumsy allegory for slavery and also civil rights and also oppression in general. And Markus is a weirdly reactive savior* because this is a badly written game that thinks that’s how you approach stories about oppression. It doesn’t want you to think about any of this or connect any dots. It’s moving you from point a to b in a pastiche of Hollywood tropes.

In contrast. V is awake and crawling through the trash because Johnny is eating their brain alive and because Takemura doesn’t know he’s trash too just yet and because V’s whole life has repeatedly gone to shit so why would dying be any different. It’s earned. Its specific. It’s poignant and ironic and fitting. It’s been set up. It’s going somewhere meaningful. We’re doing things for narrative rather than plot reasons. Good writers have strategies and narrative priorities they plot their way through. In this case, you’re being set up to start connecting complex threads through a story about what it means to be alive in a world where life is disposable.

Even outrageously long games like Rogue Trader and absolutely absurd games like Nier Automata have real reasons to scrap characters and force them to rebuild themselves beyond indulging in a trope or basic plot contrivance. Nier’s sequence drags on quite a bit but serves a profound purpose as a narrative turning point, and the agony is intentional. Rogue Trader presents a crucial narrative turning point that also deepens world building, adds character tensions, and provides satisfying mechanical challenges. Length isn’t an issue in and of itself. Neither is absurdity.

In a better game, Markus’s awakening would be a massive narrative turning point both for his character and his central role in the overall story of DBH. There’s two moments in this (again, excruciatingly drawn out) sequence that should serve that end: Markus can choose to kill and spare two other androids. It’s the same moment. Twice. One wants to live. One wants to die. You can kill or spare either. Doesn’t seem to change anything for Markus. And to add insult to insult re: the audience’s intelligence, instead of focusing the narrative on these choices, we spend our time on pointlessly-long pseudo-horror imagery and the world’s most poorly designed fetch quest (actually I just had to walk around a corner to pick up wire cutters with Kara and then walk around a room picking up objects and putting them down… so there’s some competition for the title). It’s a foreshadowing of the rest of this mess of a story. I suppose we can give it credit for being accurate foreshadowing. Markus isn’t truly someone taking up a cause because he’s become inescapably awake to the horrors of this world. Not really. If he were, his choices wouldn’t all be between killing or not killing. Markus is a savior for. Reasons. Reasons being we need to get from point a to b and nobody is thinking at all about how any of this fits together. And that’s how a trope becomes a cliche.

* Savior narratives can be great. See Buffy. Stories about freedom and oppression and corruption can have strong protagonists who aren’t saviors. See One Piece. You can do anything. It’s how you do it that matters.

#grandwitchbird does game analysis kind of#narrative strategy#obviously not tagging the game here because I’m not actually trying to be a downer in anyone who likes it#I like studying it though#it’s genuinely awful writing in a way that’s frankly rare in games#more rare than genuinely great writing imo#video games#video game analysis#tropes

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'd love to hear your thoughts on electric cars. ive been thinking of getting one myself, so ive been seeking out as many opinions as i can

ok so i personally really really don’t like them. i don’t think they’re as good for the environment as they’re made to sound - sure they have zero emissions but the amount of damage caused by lithium mining, producing the batteries, and then having to dispose of the batteries makes them far from ecological. they’re heavy, almost impossible to maintain on your own unless you’re super well versed in them, and as a result a slap in the face of right to repair. i think they have their purpose, and are good for super high performance cars and race cars, but the complete shift from gas power to electric really rubs me the wrong way.

i think the best way to lessen the environmental impact of cars, at least in the states, is to work more on less car centric infrastructure, lessening the impact of things like high traffic highways by not forcing everyone to own a car or drive it everywhere. trains are almost always the answer here. i love cars and want anyone who wants or prefers to drive to be able to, but i think the economic impact and financial impact for the individual would be far more greatly improved by implementation of accessible public transport than electric cars

and also yeah electric cars don’t go vroooom grumble grumble stutututututu and i like when cars do that lol i’m not gonna pretend that’s not part of it

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

Capitalist elites are driving the rationalities of overproduction while overconsuming and disproportionately intensifying extraction, commodification and usage of various resources, thereby threatening planetary systems and justice. Through media, advertising, influencer culture and control over means of production, they exacerbate not only inequities but perpetuate destructive growth models and logics of overproduction, overconsumption, disposal/wastage and disregard that crosses boundaries and borders. These global elites participate in accumulation by dispossession with disproportionate capitalist benefits from resource control and the promotion of neocolonialist policies via outsized policy influence. As a result, they contribute directly to ecological harms, biodiversity crises, water pollution, air pollution and climate breakdown that they themselves rarely experience firsthand, but which undermine wellbeing and safety of the majority, particularly BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and people of colour) communities everywhere. More insidiously still, socioecologically destructive and unfettered economic growth models and institutional policies shape the responses to the problems they create, influencing what desirable outcomes and solutions should be and what individuals should aspire to behave like to be modern. Instead of tackling the root causes of climate breakdown, the implication is that ideal global subjects should participate in particular notions of economic progress and consumption, even across the Majority World. As a result, the imperial modes of living of the globally-rich are promoted as global aspirations for all. The capitalist model of hyperconsumption, extractivism, commodification and a discard culture of increasing waste production are presented as signifiers of progress, while discounting their environmental consequences. This is affluence, but unsustainable affluence. The externalities are often overlooked, borne by the global poor who are simultaneously blamed for their poverty while being told they should support unsustainable capitalist models of progress. Rarely, by contrast, does the fact that the ever-expanding global billionaire class have carbon footprints thousands of times larger than average citizens feature in the models designed to curb the impacts of their behaviour. Yet this inequality is fundamental to climate breakdown. Ecological and planetary boundaries are being transgressed predominantly by capitalist elites in the Global North (or the high-energy industrialised economies), causing disproportionate social and ecological harms to large numbers of marginalised communities elsewhere. Extraction and discard culture are embedded in the economic models and processes which govern not just natural resources exploitation and commodification, but also the destruction of human lives and potentials, resulting in a disregard for the care economy and resilience of ecosystems. It also often involves lip service to basic welfare of billions caught in exploitative and neocolonial labour relations with global capital and extractive resource-based trade that causes irreversible harms, usually locally more profoundly.

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Individualist mind set is a fucking plague on the environment. I swear to fuck.

If I buy a new item of clothing I don't really need it has less environmental impact than the tens of thousands of items that go from manufacture to landfill because being without as a corporation is a worse sin than over producing and writing it off as a tax loss. The clothing I buy doesn't last a season cause it's made cheep, disposable, and not made for it. There's, like, 3 shops in the entire city centre that carries clothes in my size. What fucking choice is that?

If I let some food go bad in my fridge cause I forget about it it's not got SHIT on places like fast food places not even letting their staff eat left over food, it all has to be tallied to see what is wasted and then disposed of in the bin.

If I leave a light on in a room while I go to pee it's got fuck all on all those skyscrapers in every city across the world being illuminated all night while they are completely empty. It's got shit on Times Square and Piccadilly Circus advertising in vibrant LCD screens all day every day.

What the FUCK does my TV on standby have to the fucking huge mega servers used exclusively for trading bitcoin and NFT's back and forth for theoretical money?

I light a barbecue with friends or family. The government debates opening a new coal mine in my country for the economic benefits it will bring. It will bring jobs! The kind of jobs that can disable you, shorten your life expectancy, make someone else rich, and set a country on fire with climate change. I should really consider that charcoal on the barbecue and the co2 I'm putting out, shouldn't I? Maybe I should plant a fucking tree.

Like yes, there are things we can do as individuals, but they don't work because an individual has done it. It works because 15,000 individuals have done it. It's not individual action. It's collective. Embrace your inner fucking ant and lift with your fucking knees bro.

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

E.3.2 How does economic power contribute to the ecological crisis?

So far in this section we have discussed why markets fail to allocate environmental resources. This is due to information blocks and costs, lack of fully internalised prices (externalities) and the existence of public goods. Individual choices are shaped by the information available to them about the consequences of their actions, and the price mechanism blocks essential aspects of this and so information is usually partial at best within the market. Worse, it is usually distorted by advertising and the media as well as corporate and government spin and PR. Local knowledge is undermined by market power, leading to unsustainable practices to reap maximum short term profits. Profits as the only decision making criteria also leads to environmental destruction as something which may be ecologically essential may not be economically viable. All this means that the price of a good cannot indicate its environmental impact and so that market failure is pervasive in the environmental area. Moreover, capitalism is as unlikely to produce their fair distribution of environmental goods any more than any other good or resource due to differences in income and so demand (particularly as it takes the existing distribution of wealth as the starting point). The reality of our environmental problems provides ample evidence for this analysis.

During this discussion we have touched upon another key issue, namely how wealth can affect how environmental and other externalities are produced and dealt with in a capitalist system. Here we extend our critique by addressed an issue we have deliberately ignored until now, namely the distribution and wealth and its resulting economic power. The importance of this factor cannot be stressed too much, as “market advocates” at best downplay it or, at worse, ignore it or deny it exists. However, it plays the same role in environmental matters as it does in, say, evaluating individual freedom within capitalism. Once we factor in economic power the obvious conclusion is the market based solutions to the environment will result in, as with freedom, people selling it simply to survive under capitalism (as we discussed in section B.4, for example).

It could be argued that strictly enforcing property rights so that polluters can be sued for any damages made will solve the problem of externalities. If someone suffered pollution damage on their property which they had not consented to then they could issue a lawsuit in order to get the polluter to pay compensation for the damage they have done. This could force polluters to internalise the costs of pollution and so the threat of lawsuits can be used as an incentive to avoid polluting others.

While this approach could be considered as part of any solution to environmental problems under capitalism, the sad fact is it ignores the realities of the capitalist economy. The key phrase here is “not consented to” as it means that pollution would be fine if the others agree to it (in return, say, for money). This has obvious implications for the ability of capitalism to reduce pollution. For just as working class people “consent” to hierarchy within the workplace in return for access to the means of life, so to would they “consent” to pollution. In other words, the notion that pollution can be stopped by means of private property and lawsuits ignores the issue of class and economic inequality. Once these are factored in, it soon becomes clear that people may put up with externalities imposed upon them simply because of economic necessity and the pressure big business can inflict.

The first area to discuss is inequalities in wealth and income. Not all economic actors have equal resources. Corporations and the wealthy have far greater resources at their disposal and can spend millions of pounds in producing PR and advertising (propaganda), fighting court cases, influencing the political process, funding “experts” and think-tanks, and, if need be, fighting strikes and protests. Companies can use “a mix of cover-up, publicity campaigns and legal manoeuvres to continue operations unimpeded.” They can go to court to try an “block more stringent pollution controls.” [David Watson, Against the Megamachine, p. 56] Also while, in principle, the legal system offers equal protection to all in reality, wealthy firms and individuals have more resources than members of the general public. This means that they can employ large numbers of lawyers and draw out litigation procedures for years, if not decades.

This can be seen around us today. Unsurprisingly, the groups which bear a disproportionate share of environmental burdens are the poorest ones. Those at the bottom of the social hierarchy have less resources available to fight for their rights. They may not be aware of their rights in specific situations and not organised enough to resist. This, of course, explains why companies spend so much time attacking unions and other forms of collective organisation which change that situation. Moreover as well as being less willing to sue, those on lower income may be more willing to be bought-off due to their economic situation. After all, tolerating pollution in return for some money is more tempting when you are struggling to make ends meet.

Then there is the issue of effective demand. Simply put, allocation of resources on the market is based on money and not need. If more money can be made in, say, meeting the consumption demands of the west rather than the needs of local people then the market will “efficiently” allocate resources away from the latter to the former regardless of the social and ecological impact. Take the example of Biofuels which have been presented by some as a means of fuelling cars in a less environmentally destructive way. Yet this brings people and cars into direct competition over the most “efficient” (i.e. most profitable) use of land. Unfortunately, effective demand is on the side of cars as their owners usually live in the developed countries. This leads to a situation where land is turned from producing food to producing biofuels, the net effect of which is to reduce supply of food, increase its price and so produce an increased likelihood of starvation. It also gives more economic incentive to destroy rainforests and other fragile eco-systems in order to produce more biofuel for the market.

Green socialist John O’Neill simply states the obvious:

”[The] treatment of efficiency as if it were logically independent of distribution is at best misleading, for the determination of efficiency already presupposes a given distribution of rights … [A specific outcome] is always relative to an initial starting point … If property rights are changed so also is what is efficient. Hence, the opposition between distributional and efficiency criteria is misleading. Existing costs and benefits themselves are the product of a given distribution of property rights. Since costs are not independent of rights they cannot guide the allocation of rights. Different initial distributions entail differences in whose preferences are to count. Environmental conflicts are often about who has rights to environment goods, and hence who is to bear the costs and who is to bear the benefits … Hence, environmental policy and resource decision-making cannot avoid making normative choices which include questions of resource distribution and the relationships between conflicting rights claims … The monetary value of a ‘negative externality’ depends on social institutions and distributional conflicts — willing to pay measures, actual or hypothetical, consider preferences of the higher income groups [as] more important than those of lower ones. If the people damaged are poor, the monetary measure of the cost of damage will be lower — ‘the poor sell cheap.’” [Markets, Deliberation and Environment, pp. 58–9]

Economic power also impacts on the types of contracts people make. It does not take too much imagination to envision the possibility that companies may make signing waivers that release it from liability a condition for working there. This could mean, for example, a firm would invest (or threaten to move production) only on condition that the local community and its workers sign a form waiving the firm of any responsibility for damages that may result from working there or from its production process. In the face of economic necessity, the workers may be desperate enough to take the jobs and sign the waivers. The same would be the case for local communities, who tolerate the environmental destruction they are subjected to simply to ensure that their economy remains viable. This already happens, with some companies including a clause in their contracts which states the employee cannot join a union.

Then there is the threat of legal action by companies. “Every year,” records green Sharon Beder, “thousands of Americans are sued for speaking out against governments and corporations. Multi-million dollar law suits are being filed against individual citizens and groups for circulating petitions, writing to public officials, speaking at, or even just attending, public meetings, organising a boycott and engaging in peaceful demonstrations.” This trend has spread to other countries and the intent is the same: to silence opposition and undermine campaigns. This tactic is called a SLAPP (for “Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation”) and is a civil court action which does not seek to win compensation but rather aims “to harass, intimidate and distract their opponents … They win the political battle, even when they lose the court case, if their victims and those associated with them stop speaking out against them.” This is an example of economic power at work, for the cost to a firm is just part of doing business but could bankrupt an individual or environmental organisation. In this way “the legal system best serves those who have large financial resources at their disposal” as such cases take “an average of three years to be settled, and even if the person sued wins, can cost tens of thousands of dollars in legal fees. Emotional stress, disillusionment, diversion of time and energy, and even divisions within families, communities and groups can also result.” [Global Spin, pp. 63–7]

A SLAPP usually deters those already involved from continuing to freely participate in debate and protest as well as deterring others from joining in. The threat of a court case in the face of economic power usually ensures that SLAPPS do not go to trial and so its objective of scaring off potential opponents usually works quickly. The reason can be seen from the one case in which a SLAPP backfired, namely the McLibel trial. After successfully forcing apologies from major UK media outlets like the BBC, Channel 4 and the Guardian by threatening legal action for critical reporting of the company, McDonald’s turned its attention to the small eco-anarchist group London Greenpeace (which is not affiliated with Greenpeace International). This group had produced a leaflet called “What’s Wrong with McDonald’s” and the company sent spies to its meetings to identify people to sue. Two of the anarchists refused to be intimidated and called McDonald’s bluff. Representing themselves in court, the two unemployed activists started the longest trial in UK history. After three years and a cost of around £10 million, the trial judge found that some of the claims were untrue (significantly, McDonald’s had successfully petitioned the judge not to have a jury for the case, arguing that the issues were too complex for the public to understand). While the case was a public relations disaster for the company, McDonald’s keeps going as before using the working practices exposed in the trial and remains one of the world’s largest corporations confident that few people would have the time and resources to fight SLAPPs (although the corporation may now think twice before suing anarchists!).

Furthermore, companies are known to gather lists of known “trouble-makers” These “black lists” of people who could cause companies “trouble” (i.e., by union organising or suing employers over “property rights” issues) would often ensure employee “loyalty,” particularly if new jobs need references. Under wage labour, causing one’s employer “problems” can make one’s current and future position difficult. Being black-listed would mean no job, no wages, and little chance of being re-employed. This would be the result of continually suing in defence of one’s property rights — assuming, of course, that one had the time and money necessary to sue in the first place. Hence working-class people are a weak position to defend their rights under capitalism due to the power of employers both within and without the workplace. All these are strong incentives not to rock the boat, particularly if employees have signed a contract ensuring that they will be fired if they discuss company business with others (lawyers, unions, media, etc.).

Economic power producing terrible contracts does not affect just labour, it also effects smaller capitalists as well. As we discussed in section C.4, rather than operating “efficiently” to allocate resources within perfect competition any real capitalist market is dominated by a small group of big companies who make increased profits at the expense of their smaller rivals. This is achieved, in part, because their size gives such firms significant influence in the market, forcing smaller companies out of business or into making concessions to get and maintain contracts.

The negative environmental impact of such a process should be obvious. For example, economic power places immense pressures towards monoculture in agriculture. In the UK the market is dominated by a few big supermarkets. Their suppliers are expected to produce fruits and vegetables which meet the requirements of the supermarkets in terms of standardised products which are easy to transport and store. The large-scale nature of the operations ensure that farmers across Britain (indeed, the world) have to turn their farms into suppliers of these standardised goods and so the natural diversity of nature is systematically replaced by a few strains of specific fruits and vegetables over which the consumer can pick. Monopolisation of markets results in the monoculture of nature.

This process is at work in all capitalist nations. In American, for example, the “centralised purchasing decisions of the large restaurant chains and their demand for standardised products have given a handful of corporations an unprecedented degree of power over the nation’s food supply … obliterating regional differences, and spreading identical stores throughout the country … The key to a successful franchise . .. can be expressed in one world: ‘uniformity.’” This has resulted in the industrialisation of food production, with the “fast food chains now stand[ing] atop a huge food-industrial complex that has gained control of American agriculture … large multinationals … dominate one commodity market after another … The fast food chain’s vast purchasing power and their demand for a uniform product have encouraged fundamental changes in how cattle are raised, slaughter, and processed into ground beef. These changes have made meatpacking … into the most dangerous job in the United States … And the same meat industry practices that endanger these workers have facilitated the introduction of deadly pathogens … into America’s hamburger meat.” [Eric Schlosser, Fast Food Nation, p. 5 and pp. 8–9]

Award winning journalist Eric Schlosser has presented an excellent insight in this centralised and concentrated food-industrial complex in his book Fast Food Nation. Schlosser, of course, is not alone in documenting the fundamentally anti-ecological nature of the capitalism and how an alienated society has created an alienated means of feeding itself. As a non-anarchist, he does fail to drawn the obvious conclusion (namely abolish capitalism) but his book does present a good overview of the nature of the processed at work and what drives them. Capitalism has created a world where even the smell and taste of food is mass produced as the industrialisation of agriculture and food processing has lead to the product (it is hard to call it food) becoming bland and tasteless and so chemicals are used to counteract the effects of producing it on such a scale. It is standardised food for a standardised society. As he memorably notes: “Millions of … people at that very moment were standing at the same counter, ordering the same food from the same menu, food that tasted everywhere the same.” The Orwellian world of modern corporate capitalism is seen in all its glory. A world in which the industry group formed to combat Occupational Safety and Health Administration regulation is called “Alliance for Workplace Safety” and where the processed food’s taste has to have the correct “mouthfeel.” Unsurprisingly, the executives of these companies talk about “the very essence of freedom” and yet their corporation’s “first commandant is that only production counts … The employee’s duty is to follow orders. Period.” In this irrational world, technology will solve all our problems, even the ones it generates itself. For example, faced with the serious health problems generated by the industrialisation of meat processing, the meatpacking industry advocated yet more technology to “solve” the problems caused by the existing technology. Rather than focusing on the primary causes of meat contamination, they proposed irradiating food. Of course the firms involved want to replace the word “irradiation” with the phrase “cold pasteurisation” due to the public being unhappy with the idea of their food being subject to radiation.

All this is achievable due to the economic power of fewer and fewer firms imposing costs onto their workers, their customers and, ultimately, the planet.

The next obvious factor associated with economic power are the pressures associated with capital markets and mobility. Investors and capitalists are always seeking the maximum return and given a choice between lower profits due to greater environmental regulation and higher profits due to no such laws, the preferred option will hardly need explaining. After all, the investor is usually concerned with the returns they get in their investment, not in its physical condition nor in the overall environmental state of the planet (which is someone else’s concern). This means that investors and companies interest is in moving their capital to areas which return most money, not which have the best environmental impact and legacy. Thus the mobility of capital has to be taken into account. This is an important weapon in ensuring that the agenda of business is untroubled by social concerns and environmental issues. After all, if the owners and managers of capital consider that a state’s environmental laws too restrictive then it can simply shift investments to states with a more favourable business climate. This creates significant pressures on communities to minimise environmental protection both in order to retain existing business and attract new ones.

Let us assume that a company is polluting a local area. It is usually the case that capitalist owners rarely live near the workplaces they own, unlike workers and their families. This means that the decision makers do not have to live with the consequences of their decisions. The “free market” capitalist argument would be, again, that those affected by the pollution would sue the company. We will assume that concentrations of wealth have little or no effect on the social system (which is a highly unlikely assumption, but never mind). Surely, if local people did successfully sue, the company would be harmed economically — directly, in terms of the cost of the judgement, indirectly in terms of having to implement new, eco-friendly processes. Hence the company would be handicapped in competition, and this would have obvious consequences for the local (and wider) economy.

This gives the company an incentive to simply move to an area that would tolerate the pollution if it were sued or even threatened with a lawsuit. Not only would existing capital move, but fresh capital would not invest in an area where people stand up for their rights. This — the natural result of economic power — would be a “big stick” over the heads of the local community. And when combined with the costs and difficulties in taking a large company to court, it would make suing an unlikely option for most people. That such a result would occur can be inferred from history, where we see that multinational firms have moved production to countries with little or no pollution laws and that court cases take years, if not decades, to process.

This is the current situation on the international market, where there is competition in terms of environment laws. Unsurprisingly, industry tends to move to countries which tolerate high levels of pollution (usually because of authoritarian governments which, like the capitalists themselves, simply ignore the wishes of the general population). Thus we have a market in pollution laws which, unsurprisingly, supplies the ability to pollute to meet the demand for it. This means that developing countries “are nothing but a dumping ground and pool of cheap labour for capitalist corporations. Obsolete technology is shipped there along with the production of chemicals, medicines and other products banned in the developed world. Labour is cheap, there are few if any safety standards, and costs are cut. But the formula of cost-benefit still stands: the costs are simply borne by others, by the victims of Union Carbide, Dow, and Standard Oil.” [David Watson, Op. Cit., p. 44] This, it should be noted, makes perfect economic sense. If an accident happened and the poor actually manage to successfully sue the company, any payments will reflect their lost of earnings (i.e., not very much).

As such, there are other strong economic reasons for doing this kind of pollution exporting. You can estimate the value of production lost because of ecological damage and the value of earnings lost through its related health problems as well as health care costs. This makes it more likely that polluting industries will move to low-income areas or countries where the costs of pollution are correspondingly less (particularly compared to the profits made in selling the products in high-income areas). Rising incomes makes such goods as safety, health and the environment more valuable as the value of life is, for working people, based on their wages. Therefore, we would expect pollution to be valued less when working class people are affected by it. In other words, toxic dumps will tend to cluster around poorer areas as the costs of paying for the harm done will be much less. The same logic underlies the arguments of those who suggest that Third World countries should be dumping grounds for toxic industrial wastes since life is cheap there

This was seen in early 1992 when a memo that went out under the name of the then chief economist of the World Bank, Lawrence Summers, was leaked to the press. Discussing the issue of “dirty” Industries, the memo argued that the World Bank should “be encouraging MORE migration of the dirty industries” to Less Developed Countries and provided three reasons. Firstly, the “measurements of the costs of health impairing pollution depends on the foregone earnings from increased morbidity and mortality” and so “pollution should be done in the country with the lowest cost, which will be the country with the lowest wages.” Secondly, “that under-populated countries in Africa are vastly UNDER-polluted, their air quality is probably vastly inefficiently low compared to Los Angeles or Mexico City.” Thirdly, the “demand for a clean environment for aesthetic and health reasons is likely to have very high income elasticity.” Concern over pollution related illness would be higher in a country where more children survive to get them. “Also, much of the concern over industrial atmosphere discharge is about visibility impairing particulates … Clearly trade in goods that embody aesthetic pollution concerns could be welfare enhancing. While production is mobile the consumption of pretty air is a non-tradable.” The memo notes “the economic logic behind dumping a load of toxic waste in the lowest wage country is impeccable and we should face up to that” and ends by stating that the “problem with the arguments against all of these proposals for more pollution” in the third world “could be turned around and used more or less effectively against every Bank proposal for liberalisation.” [The Economist, 08/02/1992]

While Summers accepted the criticism for the memo, it was actually written by Lant Pritchett, a prominent economist at the Bank. Summers claimed he was being ironic and provocative. The Economist, unsurprisingly, stated “his economics was hard to answer” while criticising the language used. This was because clean growth may slower than allowing pollution to occur and this would stop “helping millions of people in the third world to escape their poverty.” [15/02/1992] So not only is poisoning the poor with pollution is economically correct, it is in fact required by morality. Ignoring the false assumption that growth, any kind of growth, always benefits the poor and the utter contempt shown for both those poor themselves and our environment what we have here is the cold logic that drives economic power to move location to maintain its right to pollute our common environment. Economically, it is perfectly logical but, in fact, totally insane (this helps explain why making people “think like an economist” takes so many years of indoctrination within university walls and why so few achieve it).

Economic power works in other ways as well. A classic example of this at work can be seen from the systematic destruction of public transport systems in America from the 1930s onwards (see David St. Clair’s The Motorization of American Cities for a well-researched account of this). These systems were deliberately bought by automotive (General Motors), oil, and tire corporations in order to eliminate a less costly (both economically and ecologically) competitor to the automobile. This was done purely to maximise sales and profits for the companies involved yet it transformed the way of life in scores of cities across America. It is doubtful that if environmental concerns had been considered important at the time that they would have stopped this from happening. This means that individual consumption decisions will be made within an market whose options can be limited simply by a large company buying out and destroying alternatives.

Then there is the issue of economic power in the media. This is well understood by corporations, who fund PR, think-tanks and “experts” to counteract environmental activism and deny, for example, that humans are contributing to global warming. Thus we have the strange position that only Americans think that there is a debate on the causes of global warming rather than a scientific consensus. The actions of corporate funded “experts” and PR have ensured that particular outcome. As Sharon Beder recounts in her book Global Spin: The Corporate Assault on Environmentalism, a large amount of money is being spent on number sophisticated techniques to change the way people think about the environment, what causes the problems we face and what we can and should do about it. Compared to the resources of environmental and green organisations, it is unsurprising that this elaborate multi-billion pound industry has poisoned public debate on such a key issue for the future of humanity by propaganda and dis-information.

Having substantial resources available means that the media can be used to further an anti-green agenda and dominate the debate (at least for a while). Take, as an example, The Skeptical Environmentalist, a book by Bjørn Lomborg (a political scientist and professor of statistics at the University of Aarhus in Denmark). When it was published in 2001, it caused a sensation with its claims that scientists and environmental organisations were making, at best, exaggerated and, at worse, false claims about the world’s environmental problems. His conclusion was panglossian in nature, namely that there was not that much to worry about and we can continue as we are. That, of course, was music to the ears of those actively destroying the environment as it reduces the likelihood that any attempt will be made to stop them.

Unsurprisingly, the book was heavily promoted by the usual suspects and, as a result received significant attention from the media. However, the extremely critical reviews and critiques it subsequently produced from expert scientists on the issues Lomborg discussed were less prominently reviewed in the media, if at all. That critics of the book argued that it was hardly an example of good science based on objectivity, understanding of the underlying concepts, appropriate statistical methods and careful peer review goes without saying. Sadly, the fact that numerous experts in the fields Lomborg discussed showed that his book was seriously flawed, misused data and statistics and marred by flawed logic and hidden value judgements was not given anything like the same coverage even though this information is far more important in terms of shaping public perception. Such works and their orchestrated media blitz provides those with a vested interest in the status quo with arguments that they should be allowed to continue their anti-environmental activities and agenda. Moreover, it takes up the valuable time of those experts who have to debunk the claims rather than do the research needed to understand the ecological problems we face and propose possible solutions.

As well as spin and propaganda aimed at adults, companies are increasingly funding children’s education. This development implies obvious limitations on the power of education to solve ecological problems. Companies will hardly provide teaching materials or fund schools which educate their pupils on the real causes of ecological problems. Unsurprisingly, a 1998 study in the US by the Consumers Union found that 80% of teaching material provided by companies was biased and provided students with incomplete or slanted information that favoured its sponsor’s products and views [Schlosser, Op. Cit., p. 55] The more dependent a school is on corporate funds, the less likely it will be to teach its students the necessity to question the motivations and activities of business. That business will not fund education which it perceives as anti-business should go without saying. As Sharon Beder summarises, “the infiltration of school curricula through banning some texts and offering corporate-based curriculum material and lesson plans in their place can conflict with educational objectives, and also with the attainment of an undistorted understanding of environmental problems.” [Op. Cit., pp. 172–3]

This indicates the real problem of purely “educational” approaches to solving the ecological crisis, namely that the ruling elite controls education (either directly or indirectly). This is to be expected, as any capitalist elite must control education because it is an essential indoctrination tool needed to promote capitalist values and to train a large population of future wage-slaves in the proper habits of obedience to authority. Thus capitalists cannot afford to lose control of the educational system. And this means that such schools will not teach students what is really necessary to avoid ecological disaster: namely the dismantling of capitalism itself. And we may add, alternative schools (organised by libertarian unions and other associations) which used libertarian education to produce anarchists would hardly be favoured by companies and so be effectively black-listed — a real deterrent to their spreading through society. Why would a capitalist company employ a graduate of a school who would make trouble for them once employed as their wage slave?