#east west: stories - salman rushdie

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#rosie’s rambling#nat version :3#natalie scatorccio#nat scatorccio#natalie yellowjackets#yellowjackets natalie#nat yellowjackets#yellowjackets nat#the nat tag#sources:#the sun is also a star nicola yoon#east west: stories salman rushdie#someday i’ll love ocean vuong#i think those are all the sources but if i’m wrong please correct me!!

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

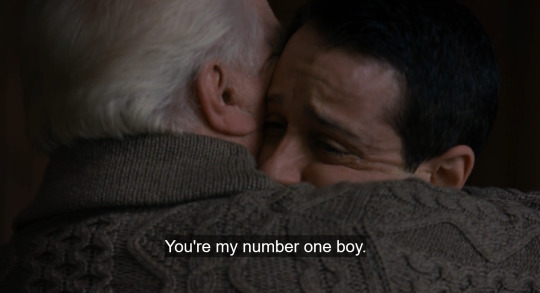

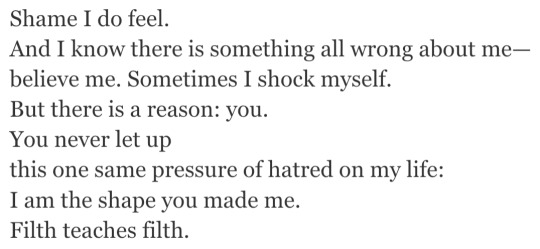

FATHERS AND THEIR CHILDREN (STRANGERS UNDER THE SAME ROOF).

East, West by Salman Rushdie / Woodtangle by Mary Ruefle / Dearest Father, a letter by Franz Kafka / This Dusk In A Mouth Full Of Prayer by Michael Wasson / Succession / Interview With The Vampire / Gangs of New York (2002), dir. by Martin Scorsese / An Oresteia by Anne Carson / The Cruel Prince by Holly Black / 6 ways to draw a circle by tumblr user filmnoirsbian / Origin Story by Desireé Dallagiacomo / Come the Slumberless To the Land of Nod by Traci Brimhal / Abraham and Isaac before the Sacrifice by Jan Victors (oil on canvas) / The Sacrifice of Isaac by Philippe de Champaigne (oil on canvas) / Supernatural, Season 1 Epside 22 'Devil's Trap' / Ruby by Cynthia Bond / Erou by Maya Phillips / Interview With The Vampire / Cut by Catherine Lacey / Succession / Frankenstein by Mary Shelley / The Last Days of Judas Iscariot by Stephen Adly Guirgis / Mindhunter / tumblr tags by @buckybucananbarnes / Saturn Devouring His Son by Francisco Goya (mixed media mural) / Saturn Devouring His Son by Peter Paul Rubens (oil on canvas) / Mother - John Lennon / Succession / Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe by Benjamin Alire Sáenz / forgiving our fathers by dick lourie

#literature#quotes#web weaving#web weave#fathers#succession#fatherhood#interview with the vampire#parallels#mine#words#word weave#fathers who hate you even though they do not know you.#fathers who hate that you have what they never had. fathers who despise you#for being luckier than they were. fathers who blame you. fathers who will always blame you.

386 notes

·

View notes

Text

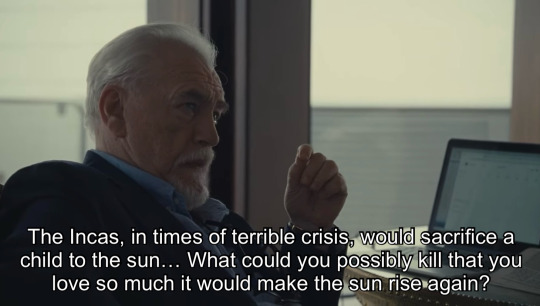

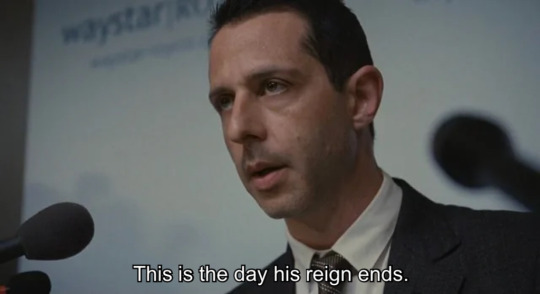

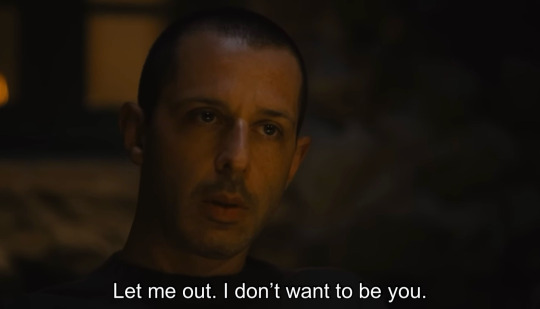

the heir: kendall logan roy

"it's fucking lonely. i'm all apart."

my similar but umm very long roman roy post

veniennes, "DOOMED FROM THE BEGINNING"

jamaica kincaid, the autobiography of my mother

katie maria (heavensghost), "it lingers for your whole life"

veniennes, "DOOMED FROM THE BEGINNING"

sophokles tr. anne carson, an oresteia: agamemnon by aiskhylos, elektra by sophokles, orestes by euripides

key ballah, "on fathers"

desireé dallagiacomo, "origin story"

elizabeth lindsey rogers, "questions about the father"

ivan turgenev, first love

george r. r. martin, a storm of swords

stephen adly guirgis, the last days of judas iscariot

eric kripke, supernatural, "in my time of dying"

amatullah bourdon (butchniqabi), "and my father’s love was nothing next to god’s will"

sam fender, "seventeen going under"

john mayer, "in the blood"

salman rushdie, east, west

george r. r. martin, a storm of swords

ocean vuong, "someday i'll love ocean vuong"

#the whiplash of learning that one of these quotes is from fucking SUPERNATURAL...#anyways i thought this would be short. OOPS!#kendall roy#logan roy#succession#succposting#webweaving#long post#abuse /#i will admit i wasn't a kenny stan. i don't have a lot in common with him.#but i think i like and understand him way more now that i've made this#my posts

276 notes

·

View notes

Text

alicent & aegon; a vicious cycle.

house of the dragon s01e05 / house of the dragon s01e06 / salman rushdie, east, west / house of the dragon s01e09 / fiona apple, relay / house of the dragon s01e02 / house of the dragon s01e08 / desireé dallagiacomo, origin story / house of the dragon s01e01 / yasmin belkhyr, bone light / house of the dragon s01e07 / house of the dragon s01e09 / leila chatti, faulty / house of the dragon s01e06 / ethel cain, wrestling in dirt pits, / house of the dragon s01e02 / house of the dragon s01e09 / unknown

#house of the dragon#hotd#alicent hightower#aegon ii targaryen#alicent x aegon#aegon x alicent#aligon#tom glynn carney#olivia cooke#web weaving#words#parallels#mothers and sons#fathers and daughters#my creations

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

ted lasso + his father

someday i’ll love ocean vuong - ocean vuong // unknown // east, west - salman rushdie // the lover - maguerite duras // the sun is also a star - nicola yoon // origin story - desireé dallagiacomo

#ted lasso#ted lasso tv#ted lasso’s father#quotes#poetry#i’m so sorry#i love him and he makes me so sad#theodore lasso#web weaving#fathers and sons#in my sadposting era#jason sudeikis

161 notes

·

View notes

Text

Out of Kansas: Revisiting The Wizard of Oz by Salman Rushdie

New York Magazine - May 4, 1992

Photograph from Everett

I wrote my first story in Bombay at the age of ten; its title was “Over the Rainbow.” It amounted to a dozen or so pages, dutifully typed up by my father’s secretary on flimsy paper, and eventually it was lost somewhere on my family’s mazy journeyings between India, England, and Pakistan. Shortly before my father’s death, in 1987, he claimed to have found a copy moldering in an old file, but, despite my pleadings, he never produced it, and nobody else ever laid eyes on the thing. I’ve often wondered about this incident. Maybe he didn’t really find the story, in which case he had succumbed to the lure of fantasy, and this was the last of the many fairy tales he told me; or else he did find it, and hugged it to himself as a talisman and a reminder of simpler times, thinking of it as his treasure, not mine—his pot of nostalgic parental gold.

I don’t remember much about the story. It was about a ten-year-old Bombay boy who one day happens upon a rainbow’s beginning, a place as elusive as any pot-of-gold end zone, and as rich in promises. The rainbow is broad, as wide as the sidewalk, and is constructed like a grand staircase. The boy, naturally, begins to climb. I have forgotten almost everything about his adventures, except for an encounter with a talking pianola, whose personality is an improbable hybrid of Judy Garland, Elvis Presley, and the “playback singers” of Hindi movies, many of which made “The Wizard of Oz” look like kitchen-sink realism. My bad memory—what my mother would call a “forgettery”—is probably just as well. I remember what matters. I remember that “The Wizard of Oz”—the film, not the book, which I didn’t read as a child—was my very first literary influence. More than that: I remember that when the possibility of my going to school in England was mentioned it felt as exciting as any voyage beyond the rainbow. It may be hard to believe, but England seemed as wonderful a prospect as Oz.

The Wizard, however, was right there in Bombay. My father, Anis Ahmed Rushdie, was a magical parent of young children, but he was prone to explosions, thunderous rages, bolts of emotional lightning, puffs of dragon smoke, and other menaces of the type also practiced by Oz, the Great and Powerful, the first Wizard De-luxe. And when the curtain fell away and his growing offspring discovered, like Dorothy, the truth about adult humbug, it was easy for me to think, as she did, that my Wizard must be a very bad man indeed. It took me half a lifetime to work out that the Great Oz’s apologia pro vita sua fitted my father equally well—that he, too, was a good man but a very bad Wizard.

I have begun with these personal reminiscences because “The Wizard of Oz” is a film whose driving force is the inadequacy of adults, even of good adults; a film that shows us how the weakness of grownups forces children to take control of their own destinies, and so, ironically, grow up themselves. The journey from Kansas to Oz is a rite of passage from a world in which Dorothy’s parent substitutes, Auntie Em and Uncle Henry, are powerless to help her save her dog, Toto, from the marauding Miss Gulch into a world where the people are her own size and she is never, ever treated as a child but as a heroine. She gains this status by accident, it’s true, having played no part in her house’s decision to squash the Wicked Witch of the East; but, by her adventure’s end, she has certainly grown to fill those shoes—or, rather, those ruby slippers. “Who would have thought a good little girl like you could destroy my beautiful wickedness,” laments the Wicked Witch of the West as she melts—an adult becoming smaller than, and giving way to, a child. As the Wicked Witch of the West “grows down,” so Dorothy is seen to have grown up. This, in my view, is a much more satisfactory reason for her newfound power over the ruby slippers than the sentimental reasons offered by the ineffably loopy Good Witch Glinda, and then by Dorothy herself, in a cloying ending that seems to me fundamentally untrue to the film’s anarchic spirit.

The weakness of Auntie Em and Uncle Henry in the face of Miss Gulch’s desire to annihilate Toto leads Dorothy to think, childishly, of running away from home—of escape. And that’s why, when the tornado hits, she isn’t with the others in the storm shelter and, as a result, is whirled away to an escape beyond her wildest dreams. Later, however, when she is confronted by the weakness of the Wizard of Oz, she doesn’t run away but goes into battle—first against the Wicked Witch and then against the Wizard himself. The Wizard’s ineffectuality is one of the film’s many symmetries, rhyming with the feebleness of Dorothy’s folks; but the different way Dorothy reacts is the point.

The ten-year-old who watched “The Wizard of Oz” at Bombay’s Metro Cinema knew very little about foreign parts, and even less about growing up. He did, however, know a great deal more about the cinema of the fantastic than any Western child of the same age. In the West, the film was an oddball, an attempt to make a sort of live-action version of a Disney cartoon feature despite the industry’s received wisdom that fantasy movies usually flopped. (Indeed, the movie never really made money until it became a television standard, years after its original theatrical release; it should be said in mitigation, though, that coming out two weeks before the start of the Second World War can’t have helped its chances.) In India, however, it fitted into what was then, and remains today, one of the mainstreams of production in the place that Indians, conflating Bombay and Tinseltown, affectionately call Bollywood.

It’s easy to satirize the Hindi movies. In James Ivory’s film “Bombay Talkie,” a novelist (the touching Jennifer Kendal, who died in 1984) visits a studio soundstage and watches an amazing dance number featuring scantily clad nautch girls prancing on the keys of a giant typewriter. The director explains that the keys of the typewriter represent “the Keys of Life,” and we are all dancing out “the story of our Fate upon that great machine.” “It’s very symbolic,” Kendal suggests. The director, simpering, replies, “Thank you.” Typewriters of Life, sex goddesses in wet saris (the Indian equivalent of wet T-shirts), gods descending from the heavens to meddle in human affairs, superheroes, demonic villains, and so on, have always been the staple diet of the Indian filmgoer. Blond Glinda arriving at Munchkinland in her magic bubble might cause Dorothy to comment on the high speed and oddity of the local transport operating in Oz, but to an Indian audience Glinda was arriving exactly as a god should arrive: ex machina, out of her own machine. The Wicked Witch of the West’s orange smoke puffs were equally appropriate to her super-bad status.

It is clear, however, that despite all the similarities, there were important differences between the Bombay cinema and a film like “The Wizard of Oz.” Good fairies and bad witches might superficially resemble the deities and demons of the Hindu pantheon, but in reality one of the most striking aspects of the world view of “The Wizard of Oz” is its joyful and almost total secularism. Religion is mentioned only once in the film: Auntie Em, spluttering with anger at gruesome Miss Gulch, declares that she’s waited years to tell her what she thinks of her, “and now, well, being a Christian woman, I can’t say it.” Apart from this moment in which Christian charity prevents some good old-fashioned plain speaking, the film is breezily godless. There’s not a trace of religion in Oz itself—bad witches are feared and good ones liked, but none are sanctified—and, while the Wizard of Oz is thought to be something very close to all-powerful, nobody thinks to worship him. This absence of higher values greatly increases the film’s charm, and is an important aspect of its success in creating a world in which nothing is deemed more important than the loves, cares, and needs of human beings (and, of course, tin beings, straw beings, lions, and dogs).

The other major difference is harder to define, because it is finally a matter of quality. Most Hindi movies were then and are now what can only be called trashy. The pleasure to be had from such films (and some of them are extremely enjoyable) is something like the fun of eating junk food. The classic Bombay talkie uses a script of appalling corniness, looks by turns tawdry and vulgar, or else both at once, and relies on the mass appeal of its stars and its musical numbers to provide a little zing. “The Wizard of Oz” has stars and musical numbers, but it is also very definitely a Good Film. It takes the fantasy of Bombay and adds high production values and something more—something not often found in any cinema. Call it imaginative truth. Call it (reach for your revolvers now) art.

But if “The Wizard of Oz” is a work of art it’s extremely difficult to say who the artist was. The birth of Oz itself has already passed into legend: the author, L. Frank Baum, named his magic world after the letters “O-Z” on the bottom drawer of his filing cabinet. His original book, “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz,” published in 1900, contains many of the ingredients of the magic potion: just about all the major characters and events are there, and so are the most important locations—the Yellow Brick Road, the Deadly Poppy Field, the Emerald City. But the filming of “The Wizard of Oz” is a rare instance of a film improving on a good book. One of the changes is the expansion of the Kansas section, which in the novel takes up precisely two pages at the beginning, before the tornado arrives, and just nine lines at the end; and another is a certain simplification of the story line in the Oz section: all subplots were jettisoned, such as the visits to the Fighting Trees, the Dainty China Country, and the Country of the Quadlings, which come into the novel just after the dramatic high point of the Witch’s destruction and fritter away the book’s narrative drive. And there are two even more important alterations. Frank Baum’s Emerald City was green only because everyone in it had to wear emerald-tinted glasses, but in the movie it really is a futuristic chlorophyll green—except, that is, for the Horse of a Different Color You’ve Heard Tell About. The Horse of a Different Color changes color in each successive shot—a change that was brought about by covering six different horses with a variety of shades of powdered Jell-O. (For this and other anecdotes of the film’s production I’m indebted to Aljean Harmetz’s definitive book “The Making of The Wizard of Oz.”) Last, and most important of all, are the ruby slippers. Frank Baum did not invent the ruby slippers; he had silver shoes instead. Noel Langley, the first of the film’s three credited writers, originally followed Baum’s idea. But in his fourth script, the script of May 14, 1938, known as the DO NOT MAKE CHANGES script, the clunky metallic and non-mythic silver footwear has been jettisoned, and the immortal jewel shoes are introduced. (In Shot 114, “the ruby shoes appear on Dorothy’s feet, glittering and sparkling in the sun.”)

Other writers contributed important details to the finished screenplay. Florence Ryerson and Edgar Allan Woolf were probably responsible for “There’s no place like home,” which, to me, is the least convincing idea in the film. (It’s one thing for Dorothy to want to get home, quite another that she can do so only by eulogizing the ideal state that Kansas so obviously is not.) But there’s some dispute about this, too; a studio memo implies that it could have been the assistant producer, Arthur Freed, who first came up with the cutesy slogan. And, after much quarrelling between Langley and the Ryerson-Woolf team, it was the film’s lyricist, Yip Harburg, who pulled together the final script: he added the crucial scene in which the Wizard, unable to give the companions what they demand, hands out emblems instead, and, to our “satiric and cynical” (the adjectives are Harburg’s own) satisfaction, they do the job. The name of the rose turns out to be the rose, after all.

Who, then, is the auteur of “The Wizard of Oz”? No single writer can claim that honor, not even the author of the original book. Mervyn LeRoy and Arthur Freed, the producers, both have their champions. At least four directors worked on the picture, most notably Victor Fleming, who left before shooting ended, however, so that he could make “Gone with the Wind” which, ironically, was the movie that dominated the Academy Awards in 1940, while “The Wizard of Oz” won just three: Best Song (“Over the Rainbow”), Best Original Score, and a Special Award for Judy Garland. The truth is that this great movie, in which the quarrels, firings, and near-bungles of all concerned produced what seems like pure, effortless, and somehow inevitable felicity, is as near as you can get to that will-o’-the-wisp of modern critical theory: the authorless text.

The Kansas described by Frank Baum is a depressing place. Everything in it is gray as far as the eye can see: the prairie is gray, and so is the house in which Dorothy lives. As for Auntie Em, “The sun and wind . . . had taken the sparkle from her eyes and left them a sober gray; they had taken the red from her cheeks and lips, and they were gray also. She was thin and gaunt, and never smiled now.” And “Uncle Henry never laughed. . . . He was gray also, from his long beard to his rough boots.” The sky? It was “even grayer than usual.” Toto, fortunately, was spared grayness. He “saved [Dorothy] from growing as gray as her other surroundings.” He was not exactly colorful, though his eyes did twinkle and his hair was silky. Toto was black.

Out of this grayness—the gathering, cumulative grayness of that bleak world—calamity comes. The tornado is the grayness gathered together and whirled about and unleashed, so to speak, against itself. And to all this the film is astonishingly faithful, shooting the Kansas scenes in what we call black-and-white but what is in reality a multiplicity of shades of gray, and darkening its images until the whirlwind sucks them up and rips them to pieces.

There is, however, another way of understanding the tornado. Dorothy has a surname: Gale. And in many ways Dorothy is the gale blowing through this little corner of nowhere, demanding justice for her little dog while the adults give in meekly to the powerful Miss Gulch; Dorothy, who is prepared to break the gray inevitability of her life by running away, and who, because she is so tenderhearted, runs back when Professor Marvel tells her Auntie Em is distraught that she has fled. Dorothy is the life force of Kansas, just as Miss Gulch is the force of death; and perhaps it is Dorothy’s feelings, or the cyclone of feelings unleashed between Dorothy and Miss Gulch, that are made actual in the great dark snake of cloud that wriggles across the prairie, eating the world.

The Kansas of the film is a little less unremittingly bleak than the Kansas of the book, if only because of the introduction of the three farmhands and of Professor Marvel—four characters who will find their “rhymes,” or counterparts, in the Three Companions of Oz and the Wizard himself. Then again, the film’s Kansas is also more terrifying than the book’s, because it adds a presence of real evil: the angular Miss Gulch, with a profile that could carve a joint, riding stiffly on her bicycle with a hat on her head like a plum pudding, or a bomb, and claiming the protection of the Law for her crusade against Toto. Thanks to Miss Gulch, the movie’s Kansas is informed not only by the sadness of dirt-poverty but also by the badness of would-be dog murderers.

And this is the home that “there’s no place like”? This is the lost Eden that we are asked to prefer (as Dorothy does) to Oz?

I remember, or I imagine I remember, that when I first saw the film Dorothy’s place struck me as a dump. Of course, if I’d been whisked off to Oz, I reasoned, I’d naturally want to get home again, because I had plenty to come home for. But Dorothy? Maybe we should invite her over to stay; anywhere looks better than that.

I thought one other thought, which gave me a sneaking regard for the Wicked Witch: I couldn’t stand Toto! I still can’t. As Gollum said of the hobbit Bilbo Baggins in another great fantasy, “Baggins: we hates it to pieces.” Toto: that little yapping hairpiece of a creature, that meddlesome rug! Frank Baum, excellent fellow, gave a distinctly minor role to the dog: it kept Dorothy happy, and when she wasn’t it had a tendency to “whine dismally”—not an endearing trait. The dog’s only really important contribution to Baum’s story came when it accidentally knocked over the screen behind which the Wizard stood concealed. The film Toto rather more deliberately pulls aside a curtain to reveal the Great Humbug, and, in spite of everything, I found this change an irritating piece of mischief-making. I was not surprised to learn that the canine actor playing Toto was possessed of a star’s temperament, and even, at one point in the shooting, brought things to a standstill by staging a nervous breakdown. That Toto should be the film’s one true object of love has always rankled.

The film begins. We are in the monochrome, “real” world of Kansas. A girl and her dog run down a country lane. “She isn’t coming yet, Toto. Did she hurt you? She tried to, didn’t she?” A real girl, a real dog, and the beginning, with the very first line of dialogue, of real drama. Kansas, however, is not real—no more real than Oz. Kansas is a pastel. Dorothy and Toto have been running down a short stretch of “road” in the M-G-M studios, and this shot has been matted into a picture of emptiness. “Real” emptiness would probably not be empty enough. This Kansas is as close as makes no difference to the universal gray of Frank Baum’s story, the void broken only by a couple of fences and the vertical lines of telegraph poles. If Oz is nowhere, then the studio setting of the Kansas scenes suggests that so is Kansas. This is necessary. A realistic depiction of the extreme poverty of Dorothy Gale’s circumstances would have created a burden, a heaviness, that would have rendered impossible the imaginative leap into Storyland, the soaring flight into Oz. The Grimms’ fairy tales, it’s true, were often brutally realistic. In “The Fisherman and His Wife,” the eponymous couple live, until they meet the magic flounder, in what is tersely described as “a pisspot.” But in many children’s versions of Grimm the pisspot is bowdlerized into a “hovel” or some even gentler word. Hollywood’s vision has always been of this soft-focus variety. Dorothy looks extremely well fed, and she is not really but unreally poor.

She arrives at the farmyard, and here (freezing the frame) we see the beginning of what will be a recurring visual motif. In the scene we have frozen, Dorothy and Toto are in the background, heading for a gate. To the left of the screen is a tree trunk, a vertical line echoing the telegraph poles of the previous scene. Hanging from an approximately horizontal branch are a triangle (for calling farmhands to dinner) and a circle (actually a rubber tire). In midshot are further geometric elements: the parallel lines of the wooden fence, the bisecting diagonal wooden bar at the gate. Later, when we see the house, the theme of simple geometry is present again: everything is right angles and triangles. The world of Kansas, that great void, is defined as “home” by the use of simple, uncomplicated shapes—none of your citified complexity here. Throughout “The Wizard of Oz,” home and safety are represented by such geometrical simplicity, whereas danger and evil are invariably twisty, irregular, and misshapen. The tornado is just such an untrustworthy, sinuous, shifting shape. Random, unfixed, it wrecks the plain shapes of that no-frills life.

Curiously, the Kansas sequence invokes not only geometry but arithmetic, too, for when Dorothy, like the chaotic force she is, bursts in upon Auntie Em and Uncle Henry with her fears about Toto, what are they doing? Why do they shoo her away? “We’re trying to count,” they admonish her as they take a census of chicks—their metaphorical chickens, their small hopes of income—which the tornado will shortly blow away. So, with simple shapes and numbers, Dorothy’s family erects its defenses against the immense and maddening emptiness; and these defenses are useless, of course.

Leaping ahead to Oz, it becomes obvious that this opposition between the geometric and the twisty is no accident. Look at the beginning of the Yellow Brick Road: it is a perfect spiral. Look at Glinda’s carriage, that perfect, luminous sphere. Look at the regimented routines of the Munchkins as they greet Dorothy and thank her for the death of the Wicked Witch of the East. Move on to the Emerald City: see it in the distance, its straight lines soaring into the sky! And now, by contrast, observe the Wicked Witch of the West: her crouching figure, her misshapen hat. How does she arrive and depart? In a puff of shapeless smoke. “Only bad witches are ugly,” Glinda tells Dorothy, a remark of high Political Incorrectness which emphasizes the film’s animosity toward whatever is tangled, claw-crooked, and weird. Woods are invariably frightening—the gnarled branches of trees are capable of coming to menacing life—and the one moment when the Yellow Brick Road itself bewilders Dorothy is the moment when it ceases to be geometric (first spiral, then rectilinear), and splits and forks every which way.

Back in Kansas, Auntie Em is delivering the scolding that is the prelude to one of the cinema’s immortal moments.

“You always get yourself into a fret over nothing. . . . Find yourself a place where you won’t get into any trouble!”

“Some place where there isn’t any trouble. Do you suppose there is such a place, Toto? There must be.”

Anybody who has swallowed the scriptwriters’ notion that this is a film about the superiority of “home” over “away, that the “moral” of “The Wizard of Oz” is as sentimental as an embroidered sampler—“East, West, Home’s Best”—would do well to listen to the yearning in Judy Garland’s voice as her face tilts up toward the skies. What she expresses here, what she embodies with the purity of an archetype, is the human dream of leaving—a dream at least as powerful as its countervailing dream of roots. At the heart of “The Wizard of Oz” is a great tension between these two dreams; but, as the music swells and that big, clean voice flies into the anguished longings of the song, can anyone doubt which message is the stronger? In its most potent emotional moment, this is inarguably a film about the joys of going away, of leaving the grayness and entering the color, of making a new life in the “place where you won’t get into any trouble.” “Over the Rainbow” is, or ought to be, the anthem of all the world’s migrants, all those who go in search of the place where “the dreams that you dare to dream really do come true.” It is a celebration of Escape, a grand paean to the Uprooted Self, a hymn—the hymn—to Elsewhere.

One of the leading actors in the cast complained that “there was no acting” in the movie, and in the usual sense this was correct. But Garland singing “Over the Rainbow” did something extraordinary: in that moment she gave the film its heart, and the force of her rendition is strong and sweet and deep enough to carry us through all the tomfoolery that follows, even to bestow upon it a touching quality, a vulnerable charm, that is matched only by Bert Lahr’s equally extraordinary creation of the role of the Cowardly Lion.

What is left to say about Garland’s Dorothy? The conventional wisdom is that the performance gains in ironic force because its innocence contrasts so starkly with what we know of the actress’s difficult later life. I’m not sure this is right. It seems to me that Garland’s performance succeeds on its own terms, and on the film’s. She is required to pull off what sounds like an impossible trick. On the one hand, she is to be the film’s tabula rasa, the blank slate upon which the action of the story gradually writes itself—or, because it is a movie, the screen upon which the action plays. Armed only with a wide-eyed look, she must be the object of the film as much as its subject, must allow herself to be the empty vessel that the movie slowly fills. And yet, at the same time, she must (with a little help from the Cowardly Lion) carry the entire emotional weight, the whole cyclonic force, of the film. That she achieves both is due not only to the mature depth of her singing voice but also to the odd stockiness, the gaucheness, that endears her to us precisely because it is half unbeautiful, jolie-laide, instead of the posturing adorableness a Shirley Temple would have brought to the role—and Temple was seriously considered for the part. The scrubbed, ever so slightly lumpy unsexiness of Garland’s playing is what makes the movie work. One can imagine the disastrous flirtatiousness young Shirley would have employed, and be grateful that Twentieth Century Fox refused to loan her to M-G-M.

The tornado, swooping down on Dorothy’s home, creates the second genuinely mythic image of “The Wizard of Oz”: the archetypal myth, one might say, of moving house. In this, the transitional sequence of the movie, when the unreal reality of Kansas gives way to the realistic surreality of the world of wizardry, there is, as befits a threshold moment, much business involving windows and doors. First, the farmhands open up the doors of the storm shelter, and Uncle Henry, heroic as ever, persuades Auntie Em that they can’t afford to wait for Dorothy. Second, Dorothy, returning with Toto from her attempt at running away, opens the screen door of the main house, which is instantly ripped from its hinges and blown away. Third, we see the others closing the doors of the storm shelter. Fourth, Dorothy, inside the house, opens a door in her frantic search for Auntie Em. Fifth, Dorothy goes to the storm shelter, but its doors are already battened down. Sixth, Dorothy retreats back inside the main house, her cry for Auntie Em weak and fearful; whereupon a window, echoing the screen door, blows off its hinges and knocks her cold. She falls upon the bed, and from now on magic reigns. We have passed through the film’s most important gateway.

But this device—the knocking out of Dorothy—is the most radical and the worst change wrought in Frank Baum’s original conception. For in the book there is no question that Oz is real—that it is a place of the same order, though not of the same type, as Kansas. The film, like the TV soap opera “Dallas,” introduces an element of bad faith when it permits the possibility that everything that follows is a dream. This type of bad faith cost “Dallas” its audience and eventually killed it off. That “The Wizard of Oz” avoided the soap opera’s fate is a testament to the general integrity of the film, which enabled it to transcend this hoary, creaking cliché.

While the house flies through the air, looking like the tiny toy it is, Dorothy “awakes.” What she sees through the window is a sort of movie—the window acting as a cinema screen, a frame within the frame—which prepares her for the new sort of movie she is about to step into. The special-effects shots, sophisticated for their time, include a lady sitting knitting in her rocking chair as the tornado whirls her by, a cow placidly standing in the eye of the storm, two men rowing a boat through the twisting air, and, most important, the figure of Miss Gulch on her bicycle, which is transformed, as we watch it, into the figure of the Wicked Witch of the West on her broomstick, her cape flying behind her, and her huge, cackling laugh rising above the storm.

The house lands; Dorothy emerges from her bedroom with Toto in her arms. We have reached the moment of color. But the first color shot, in which Dorothy walks away from the camera toward the front door of the house, is deliberately dull, an attempt to match the preceding monochrome. Then, once the door is open, color floods the screen. In these color-glutted days, it’s hard for us to imagine ourselves back in a time when color was still relatively rare in the movies. Thinking back once again to my Bombay childhood, in the nineteen-fifties—a time when Hindi movies were all in black-and-white—I can recall the excitement of the advent of color in them. In an epic about the Grand Mughal, the Emperor Akbar, entitled “Mughal-e-Azam,” there was only one reel of color photography, featuring a dance at court by the fabled Anarkali. Yet this reel alone guaranteed the film’s success, drawing crowds by the million.

The makers of “The Wizard of Oz” clearly decided that they were going to make their color as colorful as possible, much as Michelangelo Antonioni did, years later, in his first color feature, “Red Desert.” In the Antonioni film, color is used to create heightened and often surrealistic effects. “The Wizard of Oz” likewise goes for bold, Expressionist splashes—the yellow of the Brick Road, the red of the Poppy Field, the green of the Emerald City and of the Witch’s skin. So striking were the film’s color effects that soon after seeing the film as a child I began to dream of green-skinned witches; and years afterward I gave these dreams to the narrator of my novel “Midnight’s Children,” having completely forgotten their source. “No colours except green and black the walls are green the sky is black . . . the stars are green the Widow is green but her hair is black as black”: so began the stream-of-consciousness dream sequence, in which the nightmare of Indira Gandhi is fused with the equally nightmarish figure of Margaret Hamilton—a coming together of the Wicked Witches of the East and of the West.

Dorothy, stepping into color, framed by exotic foliage, with a cluster of dwarfy cottages behind her, and looking like a blue-smocked Snow White, no princess but a good, demotic American gal, is clearly struck by the absence of her familiar homey gray. “Toto, I have a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore,” she says, and that camp classic of a line has detached itself from the movie to become a great American catchphrase, endlessly recycled, and even turning up as one of the epigraphs to Thomas Pynchon’s mammoth paranoid fantasy of the Second World War, “Gravity’s Rainbow,” whose characters’ destiny lies not “behind the moon, beyond the rain” but “beyond the zero” of consciousness, in a land at least as bizarre as Oz.

But Dorothy has done more than step out of the gray into Technicolor. Her homelessness, her unhousing, is underlined by the fact that, after all the door play of the transitional sequence, and having now stepped out-of-doors, she will not be permitted to enter any interior at all until she reaches the Emerald City. From tornado to Wizard, Dorothy never has a roof over her head. Out there amid the giant hollyhocks, which bear blooms like old gramophone trumpets, there in the vulnerability of open space (albeit open space that isn’t at all like the Kansas prairie), Dorothy is about to outdo Snow White by a factor of nearly twenty. You can almost hear the M-G-M studio chiefs plotting to put the Disney hit in the shade—not simply by providing in live action almost as many miraculous effects as the Disney cartoonists created but also by surpassing Disney in the matter of the little people. If Snow White had seven dwarfs, then Dorothy Gale, from the star called Kansas, would have a hundred and twenty-four.

The Munchkins were made up and costumed exactly like 3-D cartoon figures. The Mayor of Munchkin City is quite implausibly rotund; the Coroner sings out the Witch of the East’s Certificate of Death (“And she’s not only merely dead, she’s really most sincerely dead”) while wearing a hat with an absurdly scroll-like brim; the quiffs of the Lollipop Kids, who appear to have arrived in Oz by way of Bash Street and Dead End, stand up more stiffly than Tintin’s. But what might have been a grotesque and unappetizing sequence in fact becomes the moment in which “The Wizard of Oz” captures its audience once and for all, by allying the natural charm of the story to brilliant M-G-M choreography (which alternates large-scale routines with neat little set pieces like the dance of the Lullaby League or the Sleepy Heads awaking mobcapped and be-nightied out of cracked blue eggshells set in a giant nest), and, above all, through Harold Arlen and Yip Harburg’s exceptionally witty “Ding Dong! The Witch Is Dead.” Arlen was a little contemptuous of this song and the equally unforgettable “We’re Off to See the Wizard,” calling them his “lemon-drop songs,” and perhaps this is because the real inventiveness in both tunes lies in Harburg’s lyrics. In Dorothy’s intro to “Ding Dong!” Harburg embarked on a pyrotechnic display of a-a-a rhymes (“The wind began to switch/the house to pitch”; until, at length, we meet the “witch . . . thumbin’ for a hitch”; and “what happened then was rich”)—a series in which, as with a vaudeville barker’s alliterations, we cheer each new rhyme as a sort of gymnastic triumph. This type of verbal play continues to characterize both songs. In “Ding Dong!” Harburg begins to invent punning, concertinaed words:

Ding, dong, the witch is dead!

This technique found much fuller expression in “We’re Off to See the Wizard,” becoming the real “hook” of the song:

We’re off to see the Wizard,

The wonderful Wizzerdovoz

If everoever a Wizztherwozz

The Wizzerdovoz is one because . . .

And so on.

Amid all this Munchkining we are given two very different portraits of adults. The Good Witch Glinda is pretty in pink (well, prettyish, even if Dorothy is moved to call her “beautiful”). She has a high, cooing voice, and a smile that seems to have jammed. She has one excellent gag line, after Dorothy disclaims witchy status: pointing at Toto, Glinda inquires, “Well, is that the witch?” This joke apart, she spends the scene looking generally benevolent and loving and rather too heavily powdered. Interestingly, though she is the Good Witch, the goodness of Oz does not inhere in her. The people of Oz are naturally good, unless they are under the power of the Wicked Witch (as is shown by the improved behavior of her soldiers after she melts). In the moral universe of the film, then, evil is external, dwelling solely in the dual devil figure of Miss Gulch/Wicked Witch.

(A parenthetical worry about the presentation of Munchkinland: Is it not a mite too pretty, too kempt, too sweetly sweet for a place that was, until the moment of Dorothy’s arrival, under the absolute power of the evil and dictatorial Witch of the East? How is it that this squashed Witch had no castle? How could her despotism have left so little mark upon the land? Why are the Munchkins so relatively unafraid, hiding only briefly before they emerge, and giggling while they hide? A heretical thought occurs: Maybe the Witch of the East wasn’t as bad as all that—she certainly kept the streets clean, the houses painted and in good repair, and, no doubt, such trains as there might be running on time. Moreover—and, again, unlike her sister—she seems to have ruled without the aid of soldiers, policemen, or other regiments of repression. Why, then, was she so hated? I only ask.)

Glinda and the Witch of the West are the only two symbols of power in a film that is largely about the powerless, and it’s instructive to “unpack” them. They are both women, and a striking aspect of “The Wizard of Oz” is its lack of a male hero—because, for all their brains, heart, and courage, it is impossible to see the Scarecrow, the Tin Man, and the Cowardly Lion as classic Hollywood leading men. The power center of the film is a triangle at whose points are Glinda, Dorothy, and the Witch; the fourth point, at which the Wizard is thought for most of the film to stand, turns out to be an illusion. The power of men, it is suggested, is illusory; the power of women is real.

Of the two Witches, good and bad, can there be anyone who’d choose to spend five minutes with Glinda? Of course, Glinda is “good” and the Wicked Witch “bad”; but Glinda is a silly pain in the neck, and the Wicked Witch is lean and mean. Check out their clothes: frilly pink versus slim line black. No contest. Consider their attitudes toward their fellow-women: Glinda simpers upon being called beautiful, and denigrates her unbeautiful sisters, whereas the Wicked Witch is in a rage because of the death of her sister, demonstrating, one might say, a commendable sense of solidarity. We may hiss at her, and she may terrify us as children, but at least she doesn’t embarrass us the way Glinda does. It’s true that Glinda exudes a sort of raddled motherly safeness while the Witch of the West looks—in this scene, anyhow—curiously frail and impotent, obliged to mouth empty threats (“I’ll bide my time. . . . But just try to stay out of my way”). Yet just as feminism has sought to rehabilitate pejorative old words such as “hag,” “crone,” and “witch,” so the Wicked Witch of the West can be said to represent the more positive of the two images of powerful womanhood on offer here. Glinda and the Wicked Witch clash most fiercely over the ruby slippers, which Glinda magics off the feet of the dead Witch of the East and onto Dorothy’s feet, and which the Wicked Witch seemingly has no power to remove. But Glinda’s instructions to Dorothy are oddly enigmatic, even contradictory. She first tells Dorothy, “Their magic must be very powerful or she wouldn’t want them so badly,” and later she says, “Never let those ruby slippers off your feet for a moment or you will be at the mercy of the Wicked Witch of the West.” Now, Statement No. 1 suggests that Glinda is unclear about the nature of the ruby slippers, whereas Statement No. 2 suggests that she knows all about their protective power. Neither statement hints at the ruby slippers’ later role in helping to get Dorothy back to Kansas. It seems probable that this confusion is a hangover from the long, dissension-riddled scripting process, in which the function of the slippers was the subject of considerable dispute. But one can also see Glinda’s obliquities as proof that a good fairy or a good witch, when she sets out to be of assistance, never gives you everything. Glinda, after all, is not so unlike her description of the Wizard of Oz: “Oh, very good, but very mysterious.”

“Just follow the Yellow Brick Road,” says Glinda, and bubbles off into the blue hills in the distance; and Dorothy—geometrically influenced, as who would not be after a childhood among triangles, circles, and squares—begins her journey at the very point from which the Road spirals outward. And as she does so, and while both she and the Munchkins are echoing Glinda’s instructions in tones both raucously high and gutturally low, something begins to happen to her feet: their motion acquires a syncopation, which by beautifully slow stages grows more and more noticeable until at last, as the ensemble bursts for the first time into the film’s theme song, we see, fully developed, the clever, shuffling little skip that will be the leitmotif of the entire journey:

You’re off to see the Wizard,

The wonderful Wizzerdovoz.

You’ll find he is a Wizzovawizz

If ever a Wizztherwozz. . . .

In this way, s-skipping along, Dorothy Gale, who is already a National Heroine of Munchkinland, who is already (as the Munchkins have assured her) History, who “will be a Bust in the Hall of Fame,” steps out along the road of destiny, and heads, as Americans must, into the West: toward the sunset, the Emerald City, and the Witch.

I have always found off-camera anecdotes about a film’s production simultaneously delicious and disappointing, especially when the film concerned has lodged as deep down inside as “The Wizard of Oz” has. It was a little sad to learn about the Wizard’s drinking problem, and to discover that Frank Morgan was only the third choice for the part, behind W. C. Fields and Ed Wynn. (What contemptuous wildness Fields might have brought to the role!) The first choice for his female more-than-opposite number, the Witch, was Gale Sondergaard, not only a great beauty but, prospectively, another Gale to set alongside Dorothy and the tornado. Then I found myself staring at an old color photograph of the Scarecrow, the Tin Man, and Dorothy, posing in a forest set, surrounded by autumn leaves, and realized that what I was looking at was not the stars at all but their stunt doubles, their stand-ins. It was an unremarkable studio still, but it took my breath away; for it, too, was both melancholy and mesmeric. In my mind, it came to be the very epitome of the doubleness of my responses.

There they stand, Nathanael West’s locusts, the ultimate wannabes. Garland’s shadow, Bobbie Koshay, with her hands clasped behind her back and a white bow in her hair, is doing her brave best to smile, but she knows she’s a counterfeit, all right: there are no ruby slippers on her feet. The mock-Scarecrow looks glum, too, even though he has avoided the full-scale burlap-sack makeup that was Ray Bolger’s daily fate. If it were not for the clump of straw poking out of his right sleeve, you’d think he was some kind of hobo. Between them, in full metallic drag, stands the Tin Man’s tinnier echo, looking as miserable as hell. Stand-ins know their fate: they know we don’t want to admit their existence, even though our rational minds tell us that when we watch the figure in this or that difficult shot—watch the Wicked Witch fly, or the Cowardly Lion dive through a glass window—we aren’t watching the stars. The part of us that has suspended disbelief insists on seeing the stars, and not their doubles. Thus, the stand-ins are rendered invisible even when they are in full view. They remain off camera even when they are onscreen.

However, this is not the reason for the curious fascination of the photograph; that arises from the fact that, in the case of a beloved film, we are all the stars’ doubles. Our imaginations put us in the Lion’s skin, fit the sparkling slippers on our feet, send us cackling through the air on a broomstick. To look at this photograph is to look into a mirror; in it we see ourselves. The world of “The Wizard of Oz” has possessed us. We have become the stand-ins. A pair of ruby slippers found in a bin in a basement at M-G-M was sold at auction in May, 1970, for the amazing sum of fifteen thousand dollars. The purchaser was, and has remained, anonymous. Who was it who wished so profoundly to possess—perhaps even to wear—Dorothy’s magic shoes?

On being asked to pick a single defining image of “The Wizard of Oz,” most of us would, I suspect, come up with the Scarecrow, the Tin Man, the Cowardly Lion, and Dorothy s-skipping down the Yellow Brick Road. (In point of fact, the skip continues to grow throughout the journey, and becomes a full-fledged h-hop.) How strange that the most famous passage of this very filmic film—a film packed with technical ingenuity and effects—should be the least cinematic, the most “stagy,” part of the whole! Or perhaps not so strange, for this is primarily a passage of surreal comedy, and we recall that the equally inspired clowning of the Marx Brothers was no less stagily filmed; the zany mayhem of the playing made any but the simplest camera techniques impossible.

The Scarecrow and the Tin Man are pure products of the burlesque theatre, specializing in pantomime exaggerations of voice and body movements, pratfalls (the Scarecrow descending from his post), improbable leanings beyond the center of gravity (the Tin Man during his little dance), and, of course, the smart-ass backchat of the crosstalk act:

TIN MAN (rusted solid): (Squawks)

DOROTHY: He said “Oil can”!

At the pinnacle of all this clowning is that fully realized comic masterpiece of a creation, Bert Lahr’s Cowardly Lion, all elongated vowel sounds (“Put ‘em uuuuuuuup”), ridiculous rhymes (“rhinoceros” and “imposserous”), transparent bravado, and huge, operatic, tail-tugging, blubbering terror. All three—Scarecrow, Tin Man, and Lion—are, in T. S. Eliot’s phrase, hollow men. The Scarecrow, of course, actually does have a “headpiece filled with straw, alas,” but the Tin Man, the ancestor of C-3PO in “Star Wars,” is completely empty—he bangs on his chest to prove that his innards are missing, because “the Tinsmith,” his shadowy maker, forgot to provide a heart—and the Lion lacks the most leonine of qualities, lamenting:

What makes the Hottentot so hot?

What puts the ape in apricot?

What have they got that I ain’t got?

Perhaps it is because they are all hollow that our imaginations can enter them and fill them up so easily. That is to say, it is their anti-heroism, their apparent lack of Great Qualities, that makes them our size, or even smaller, so that we can stand among them as equals, like Dorothy among the Munchkins. Gradually, however, we discover that, along with their “straight man,” Dorothy (she occupies in this sequence the role of the unfunny Marx Brother, the one who could sing and look hunky and do little else), they embody one of the film’s “messages”—that we already possess what we seek most fervently. The Scarecrow regularly comes up with bright ideas, which he offers with self-deprecating disclaimers. The Tin Man can weep with grief long before the Wizard gives him a heart. And Dorothy’s capture by the Witch brings out the Lion’s courage, even though he pleads with his friends to “talk me out of it.” For this message to have its full impact, however, it is necessary that we learn the futility of looking for solutions outside. We must learn about one more hollow man: the Wizard of Oz himself. Just as the Tinsmith was a flawed maker of tin men—just as, in this secular movie, the Tin Man’s god is dead—so too must our belief in wizards perish, so that we may believe in ourselves. We must survive the Deadly Poppy Field, helped by a mysterious snowfall (why does snow overcome the poppies’ poison?), and so arrive, accompanied by heavenly choirs, at the city gates.

Here the film changes convention once again, becoming a portrait of hicks from the sticks arriving in the metropolis—one of the classic themes of American films, with echoes in “Mr. Deeds Goes to Town,” and even in Clark Kent’s arrival at the Daily Planet in “Superman.” Dorothy is a country hick, “Dorothy the small and meek”; her companions are backwoods buffoons. Yet—and this, too, is a familiar Hollywood trope—it is the out-of-towners, the country mice, who will save the day.

There was never a metropolis quite like Emerald City, however. It looks from the outside like a fairy tale of New York, a thicket of skyscraping green towers. On the inside, though, it’s the very essence of quaintness. Even more startling is the discovery that the citizens—many of them played by Frank Morgan, who adds the parts of the gatekeeper, the driver of the horse-drawn buggy, and the palace guard to those of Professor Marvel and the Wizard—speak with what Hollywood actors like to call an English accent. “Tyke yer anyplace in the city, we does,” says the driver, adding, “I’ll tyke yer to a little place where you can tidy up a bit, what?” Other members of the citizenry are dressed like Grand Hotel bellhops and glitzy nuns, and they say—or, rather, sing—things like “Jolly good fun!” Dorothy catches on quickly. At the Wash & Brush Up Co., a tribute to urban technological genius with none of the dark doubts of a “Modern Times” or a “City Lights,” our heroine gets a little Englished herself:

DOROTHY (sings): Can you even dye my eyes to match my gown?

Most of the citizenry are cheerfully friendly, and those who appear not to be—the gatekeeper, the palace guard—are soon won over. (In this respect, once again, they are untypical city folk.) Our four friends finally gain entry to the Wizard’s palace because Dorothy’s tears of frustration undam a quite alarming reservoir of liquid in the guard. His face is quickly sodden with tears, and, watching this extreme performance, you are struck by the sheer number of occasions on which people cry in this film. Besides Dorothy and the guard, there is the Cowardly Lion, who bawls when Dorothy bops him on the nose; the Tin Man, who almost rusts up again from weeping; and Dorothy again, while she is in the clutches of the Witch It occurs to you that if the hydrophobic Witch could only have been closer at hand on one of these occasions the movie might have been much shorter.

Into the palace we go, down an arched corridor that looks like an elongated version of the Looney Tunes logo, and at last we confront a Wizard whose tricks—giant heads and flashes of fire—conceal his basic kinship with Dorothy. He, too, is an immigrant; indeed, as he will later reveal, he is a Kansas man himself. (In the novel, he came from Omaha.) These two immigrants have adopted opposite strategies of survival in a new and strange land. Dorothy has been unfailingly polite, careful, courteously “small and meek,” whereas the Wizard has been fire and smoke, bravado and bombast, and has hustled his way to the top—floated there, so to speak, on a cloud of his own hot air. But Dorothy learns that meekness isn’t enough, and the Wizard finds (as his balloon gets the better of him for a second time) that his command of hot air isn’t all it should be. (It is hard for a migrant like me not to see in these shifting destinies a parable of the migrant condition.)

The Wizard’s stipulation that he will grant no wishes until the four friends have brought him the Witch’s broomstick ushers in the penultimate, and least challenging (though most action-packed and “exciting”), movement of the film, which is in this phase at once a buddy movie, a straightforward adventure yarn, and, after Dorothy’s capture, a more or less conventional princess-rescue story. The film, having arrived at the great dramatic climax of the confrontation with the Wizard of Oz, sags for a while, and doesn’t really regain momentum until the equally climactic final struggle with the Wicked Witch, which ends with her melting, her “growing down” into nothingness.

Fast forward. The Witch is gone. The Wizard has been unmasked, and in the moment of his unveiling has succeeded in performing a spot of true magic, giving Dorothy’s companions the gifts they did not believe until that moment that they possessed. The Wizard is gone, too, and without Dorothy, their plans having been fouled up by (who else but) Toto. And here is Glinda, telling Dorothy she has to learn the meaning of the ruby slippers for herself.

TIN MAN: What have you learned, Dorothy?

DOROTHY: . . . If I ever go looking for my heart’s desire again, I won’t look any further than my own back yard; because if it isn’t there, I never really lost it to begin with. Is that right?

GLINDA: That’s all it is. . . . Now those magic slippers will take you home in two seconds. . . . Close your eyes and tap your heels together three times . . . and think to yourself . . . there’s no place like . . .

Hold it.

How does it come about that at the close of this radical and enabling film—which teaches us in the least didactic way possible to build on what we have, to make the best of ourselves—we are given this conservative little homily? Are we to think that Dorothy has learned no more on her journey than that she didn’t need to make such a journey in the first place? Must we believe that she now accepts the limitations of her home life, and agrees that the things she doesn’t have there are no loss to her? “Is that right?” Well, excuse me, Glinda, but it is not.

Home again, in black-and-white, with Auntie Em and Uncle Henry and the rude mechanicals clustered around her bed, Dorothy begins her second revolt, fighting not only against the patronizing dismissals by her own folk but also against the scriptwriters and the sentimental moralizing of the entire Hollywood studio system. “It wasn’t a dream, it was a place!” she cries piteously. “A real, truly live place! . . . Doesn’t anyone believe me?”

Many, many people did believe her. Frank Baum’s readers believed her, and their belief in Oz led him to write thirteen further Oz books, admittedly of diminishing quality; the series was continued, even more feebly, by other hands after his death. Dorothy, ignoring the “lessons” of the ruby slippers, goes back to Oz, in spite of the efforts of Kansas folk, including Auntie Em and Uncle Henry, to have her dreams brainwashed out of her (see the terrifying electro-convulsive-therapy sequence in the recent Disney film “Return to Oz”); and, in the sixth book of the series, she sends for Auntie Em and Uncle Henry, and they all settle down in Oz, where Dorothy becomes a Princess.

So Oz finally becomes home. The imagined world becomes the actual world, as it does for us all, because the truth is that, once we leave our childhood places and start to make up our lives, armed only with what we know and who we are, we come to understand that the real secret of the ruby slippers is not that “there’s no place like home” but, rather, that there is no longer any such place ashome—except, of course, for the homes we make, or the homes that are made for us, in Oz. Which is anywhere—and everywhere—except the place from which we began.

In the place from which I began, after all, I watched the film from the child’s—Dorothy’s—point of view. I experienced, with her, the frustration of being brushed aside by Uncle Henry and Auntie Em, busy with their dull grownup counting. Like all adults, they couldn’t focus on what was really important: namely, the threat to Toto. I ran away with her and then ran back. Even the shock of discovering that the Wizard was a humbug was a shock I felt as a child, a shock to the child’s faith in adults. Perhaps, too, I felt something deeper, something I couldn’t then articulate; perhaps some half-formed suspicion about grownups was being confirmed.

Now, as I look at the movie again, I have become the fallible adult. Now I am a member of the tribe of imperfect parents who cannot listen to their children’s voices. I, who no longer have a father, have become a father instead. Now it is my fate to be unable to satisfy the longings of a child. And this is the last and most terrible lesson of the film: that there is one final, unexpected rite of passage. In the end, ceasing to be children, we all become magicians without magic, exposed conjurers, with only our simple humanity to get us through.

We are the humbugs now. ♦

0 notes

Text

The Power and Influence of Global Indians: A Worldwide Diaspora

In a rapidly changing world, the influence of diaspora communities cannot be underestimated. Global Indians, a term often used to describe people of Indian origin living outside India, constitute one of the most significant and influential diaspora groups worldwide. The global Indian community has not only made substantial contributions to the countries they reside in but has also retained a strong connection to their roots in India. In this blog, we will explore the power and influence of Global Indians, their impact on various aspects of society, and the role they play in shaping the world.

The Global Indian Diaspora

Global Indians, also known as Non-Resident Indians (NRIs) or People of Indian Origin (PIOs), are a diverse group that encompasses individuals of Indian heritage living in every corner of the world. While many Global Indians are the descendants of immigrants who left India generations ago, there are also those who have migrated more recently for educational or professional opportunities.

This diaspora has grown substantially over the years and is currently estimated to number over 30 million individuals. It spans continents and includes influential communities in countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and the Gulf countries. This widespread presence gives Global Indians a unique perspective and a significant role to play on the global stage.

Economic Powerhouses

One of the most notable contributions of Global Indians to their adopted countries is their economic impact. A substantial number of Global Indians have excelled in various fields, from technology and finance to healthcare and academia. They have founded successful startups, risen to leadership positions in multinational corporations, and contributed to innovation and entrepreneurship in their respective countries.

For instance, Silicon Valley is home to a large and influential Indian diaspora, including leaders like Sundar Pichai (CEO of Google), Satya Nadella (CEO of Microsoft), and Arvind Krishna (CEO of IBM). These individuals have not only shaped the technology landscape but have also driven economic growth and job creation.

In the United Kingdom, Global Indians have made significant contributions to the financial sector, with individuals like Anshu Jain (former co-CEO of Deutsche Bank) and Rakesh Kapoor (former CEO of Reckitt Benckiser) leaving a lasting mark on the global business landscape.

Cultural and Artistic Contributions

Global Indians have also played a vital role in promoting Indian culture and arts on a global scale. Indian cinema, including Bollywood, has a vast international fanbase, and actors like Priyanka Chopra, Aishwarya Rai, and Irrfan Khan have achieved global recognition and success. These artists have helped bridge cultural gaps and showcase the rich and diverse tapestry of Indian culture to the world.

The literary world has also been greatly influenced by Global Indians, with authors like Salman Rushdie, Arundhati Roy, and Jhumpa Lahiri gaining international acclaim for their works. Their stories often explore the themes of identity, migration, and the complex relationship between the East and the West.

Diplomatic and Political Influence

The political arena is another domain where Global Indians have made their mark. Many have entered politics and held influential positions in their adopted countries. For instance, Kamala Harris, the Vice President of the United States, has Indian roots, and Priti Patel serves as the Home Secretary in the UK government.

These individuals bring a unique perspective to their roles, advocating for issues that affect both their home countries and the countries they serve, and they serve as role models for future generations.

Philanthropy and Social Impact

Global Indians have also been active in philanthropic and social initiatives, both in their adopted countries and in India. They have established charitable foundations, funded educational institutions, and contributed to healthcare and social development programs.

The Indian diaspora plays a significant role in supporting India's growth and development through investments, remittances, and philanthropic activities. Their contributions have a direct and positive impact on improving the quality of life for millions of people in India.

Global Indians represent a dynamic and influential diaspora that continues to make remarkable contributions to the countries they live in and to India itself. Their success in various fields, from business and technology to culture and politics, highlights the diversity, resilience, and adaptability of the Indian diaspora.

As the world becomes increasingly interconnected, the role of Global Indians in shaping international relations, economies, and cultural exchange will only continue to grow. Their ability to bridge the gap between cultures and bring about positive change makes them a force to be reckoned with in the global landscape. Global Indians are more than a diaspora; they are global ambassadors of India, and their impact is truly remarkable.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Out of Kansas: Revisiting “The Wizard of Oz.”

By Salman Rushdie May 4, 1992

I wrote my first story in Bombay at the age of ten; its title was “Over the Rainbow.” It amounted to a dozen or so pages, dutifully typed up by my father’s secretary on flimsy paper, and eventually it was lost somewhere on my family’s mazy journeyings between India, England, and Pakistan. Shortly before my father’s death, in 1987, he claimed to have found a copy moldering in an old file, but, despite my pleadings, he never produced it, and nobody else ever laid eyes on the thing. I’ve often wondered about this incident. Maybe he didn’t really find the story, in which case he had succumbed to the lure of fantasy, and this was the last of the many fairy tales he told me; or else he did find it, and hugged it to himself as a talisman and a reminder of simpler times, thinking of it as his treasure, not mine—his pot of nostalgic parental gold.

I don’t remember much about the story. It was about a ten-year-old Bombay boy who one day happens upon a rainbow’s beginning, a place as elusive as any pot-of-gold end zone, and as rich in promises. The rainbow is broad, as wide as the sidewalk, and is constructed like a grand staircase. The boy, naturally, begins to climb. I have forgotten almost everything about his adventures, except for an encounter with a talking pianola, whose personality is an improbable hybrid of Judy Garland, Elvis Presley, and the “playback singers” of Hindi movies, many of which made “The Wizard of Oz” look like kitchen-sink realism. My bad memory—what my mother would call a “forgettery”—is probably just as well. I remember what matters. I remember that “The Wizard of Oz”—the film, not the book, which I didn’t read as a child—was my very first literary influence. More than that: I remember that when the possibility of my going to school in England was mentioned it felt as exciting as any voyage beyond the rainbow. It may be hard to believe, but England seemed as wonderful a prospect as Oz.

The Wizard, however, was right there in Bombay. My father, Anis Ahmed Rushdie, was a magical parent of young children, but he was prone to explosions, thunderous rages, bolts of emotional lightning, puffs of dragon smoke, and other menaces of the type also practiced by Oz, the Great and Powerful, the first Wizard De-luxe. And when the curtain fell away and his growing offspring discovered, like Dorothy, the truth about adult humbug, it was easy for me to think, as she did, that my Wizard must be a very bad man indeed. It took me half a lifetime to work out that the Great Oz’s apologia pro vita sua fitted my father equally well—that he, too, was a good man but a very bad Wizard.

I have begun with these personal reminiscences because “The Wizard of Oz” is a film whose driving force is the inadequacy of adults, even of good adults; a film that shows us how the weakness of grownups forces children to take control of their own destinies, and so, ironically, grow up themselves. The journey from Kansas to Oz is a rite of passage from a world in which Dorothy’s parent substitutes, Auntie Em and Uncle Henry, are powerless to help her save her dog, Toto, from the marauding Miss Gulch into a world where the people are her own size and she is never, ever treated as a child but as a heroine. She gains this status by accident, it’s true, having played no part in her house’s decision to squash the Wicked Witch of the East; but, by her adventure’s end, she has certainly grown to fill those shoes—or, rather, those ruby slippers. “Who would have thought a good little girl like you could destroy my beautiful wickedness,” laments the Wicked Witch of the West as she melts—an adult becoming smaller than, and giving way to, a child. As the Wicked Witch of the West “grows down,” so Dorothy is seen to have grown up. This, in my view, is a much more satisfactory reason for her newfound power over the ruby slippers than the sentimental reasons offered by the ineffably loopy Good Witch Glinda, and then by Dorothy herself, in a cloying ending that seems to me fundamentally untrue to the film’s anarchic spirit.

The weakness of Auntie Em and Uncle Henry in the face of Miss Gulch’s desire to annihilate Toto leads Dorothy to think, childishly, of running away from home—of escape. And that’s why, when the tornado hits, she isn’t with the others in the storm shelter and, as a result, is whirled away to an escape beyond her wildest dreams. Later, however, when she is confronted by the weakness of the Wizard of Oz, she doesn’t run away but goes into battle—first against the Wicked Witch and then against the Wizard himself. The Wizard’s ineffectuality is one of the film’s many symmetries, rhyming with the feebleness of Dorothy’s folks; but the different way Dorothy reacts is the point.

The ten-year-old who watched “The Wizard of Oz” at Bombay’s Metro Cinema knew very little about foreign parts, and even less about growing up. He did, however, know a great deal more about the cinema of the fantastic than any Western child of the same age. In the West, the film was an oddball, an attempt to make a sort of live-action version of a Disney cartoon feature despite the industry’s received wisdom that fantasy movies usually flopped. (Indeed, the movie never really made money until it became a television standard, years after its original theatrical release; it should be said in mitigation, though, that coming out two weeks before the start of the Second World War can’t have helped its chances.) In India, however, it fitted into what was then, and remains today, one of the mainstreams of production in the place that Indians, conflating Bombay and Tinseltown, affectionately call Bollywood.

It’s easy to satirize the Hindi movies. In James Ivory’s film “Bombay Talkie,” a novelist (the touching Jennifer Kendal, who died in 1984) visits a studio soundstage and watches an amazing dance number featuring scantily clad nautch girls prancing on the keys of a giant typewriter. The director explains that the keys of the typewriter represent “the Keys of Life,” and we are all dancing out “the story of our Fate upon that great machine.” “It’s very symbolic,” Kendal suggests. The director, simpering, replies, “Thank you.” Typewriters of Life, sex goddesses in wet saris (the Indian equivalent of wet T-shirts), gods descending from the heavens to meddle in human affairs, superheroes, demonic villains, and so on, have always been the staple diet of the Indian filmgoer. Blond Glinda arriving at Munchkinland in her magic bubble might cause Dorothy to comment on the high speed and oddity of the local transport operating in Oz, but to an Indian audience Glinda was arriving exactly as a god should arrive: ex machina, out of her own machine. The Wicked Witch of the West’s orange smoke puffs were equally appropriate to her super-bad status.

It is clear, however, that despite all the similarities, there were important differences between the Bombay cinema and a film like “The Wizard of Oz.” Good fairies and bad witches might superficially resemble the deities and demons of the Hindu pantheon, but in reality one of the most striking aspects of the world view of “The Wizard of Oz” is its joyful and almost total secularism. Religion is mentioned only once in the film: Auntie Em, spluttering with anger at gruesome Miss Gulch, declares that she’s waited years to tell her what she thinks of her, “and now, well, being a Christian woman, I can’t say it.” Apart from this moment in which Christian charity prevents some good old-fashioned plain speaking, the film is breezily godless. There’s not a trace of religion in Oz itself—bad witches are feared and good ones liked, but none are sanctified—and, while the Wizard of Oz is thought to be something very close to all-powerful, nobody thinks to worship him. This absence of higher values greatly increases the film’s charm, and is an important aspect of its success in creating a world in which nothing is deemed more important than the loves, cares, and needs of human beings (and, of course, tin beings, straw beings, lions, and dogs).

The other major difference is harder to define, because it is finally a matter of quality. Most Hindi movies were then and are now what can only be called trashy. The pleasure to be had from such films (and some of them are extremely enjoyable) is something like the fun of eating junk food. The classic Bombay talkie uses a script of appalling corniness, looks by turns tawdry and vulgar, or else both at once, and relies on the mass appeal of its stars and its musical numbers to provide a little zing. “The Wizard of Oz” has stars and musical numbers, but it is also very definitely a Good Film. It takes the fantasy of Bombay and adds high production values and something more—something not often found in any cinema. Call it imaginative truth. Call it (reach for your revolvers now) art.

But if “The Wizard of Oz” is a work of art it’s extremely difficult to say who the artist was. The birth of Oz itself has already passed into legend: the author, L. Frank Baum, named his magic world after the letters “O-Z” on the bottom drawer of his filing cabinet. His original book, “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz,” published in 1900, contains many of the ingredients of the magic potion: just about all the major characters and events are there, and so are the most important locations—the Yellow Brick Road, the Deadly Poppy Field, the Emerald City. But the filming of “The Wizard of Oz” is a rare instance of a film improving on a good book. One of the changes is the expansion of the Kansas section, which in the novel takes up precisely two pages at the beginning, before the tornado arrives, and just nine lines at the end; and another is a certain simplification of the story line in the Oz section: all subplots were jettisoned, such as the visits to the Fighting Trees, the Dainty China Country, and the Country of the Quadlings, which come into the novel just after the dramatic high point of the Witch’s destruction and fritter away the book’s narrative drive. And there are two even more important alterations. Frank Baum’s Emerald City was green only because everyone in it had to wear emerald-tinted glasses, but in the movie it really is a futuristic chlorophyll green—except, that is, for the Horse of a Different Color You’ve Heard Tell About. The Horse of a Different Color changes color in each successive shot—a change that was brought about by covering six different horses with a variety of shades of powdered Jell-O. (For this and other anecdotes of the film’s production I’m indebted to Aljean Harmetz’s definitive book “The Making of The Wizard of Oz.”) Last, and most important of all, are the ruby slippers. Frank Baum did not invent the ruby slippers; he had silver shoes instead. Noel Langley, the first of the film’s three credited writers, originally followed Baum’s idea. But in his fourth script, the script of May 14, 1938, known as the do not make changes script, the clunky metallic and non-mythic silver footwear has been jettisoned, and the immortal jewel shoes are introduced. (In Shot 114, “the ruby shoes appear on Dorothy’s feet, glittering and sparkling in the sun.”)

Other writers contributed important details to the finished screenplay. Florence Ryerson and Edgar Allan Woolf were probably responsible for “There’s no place like home,” which, to me, is the least convincing idea in the film. (It’s one thing for Dorothy to want to get home, quite another that she can do so only by eulogizing the ideal state that Kansas so obviously is not.) But there’s some dispute about this, too; a studio memo implies that it could have been the assistant producer, Arthur Freed, who first came up with the cutesy slogan. And, after much quarrelling between Langley and the Ryerson-Woolf team, it was the film’s lyricist, Yip Harburg, who pulled together the final script: he added the crucial scene in which the Wizard, unable to give the companions what they demand, hands out emblems instead, and, to our “satiric and cynical” (the adjectives are Harburg’s own) satisfaction, they do the job. The name of the rose turns out to be the rose, after all.

Who, then, is the auteur of “The Wizard of Oz”? No single writer can claim that honor, not even the author of the original book. Mervyn LeRoy and Arthur Freed, the producers, both have their champions. At least four directors worked on the picture, most notably Victor Fleming, who left before shooting ended, however, so that he could make “Gone with the Wind” which, ironically, was the movie that dominated the Academy Awards in 1940, while “The Wizard of Oz” won just three: Best Song (“Over the Rainbow”), Best Original Score, and a Special Award for Judy Garland. The truth is that this great movie, in which the quarrels, firings, and near-bungles of all concerned produced what seems like pure, effortless, and somehow inevitable felicity, is as near as you can get to that will-o’-the-wisp of modern critical theory: the authorless text.

The Kansas described by Frank Baum is a depressing place. Everything in it is gray as far as the eye can see: the prairie is gray, and so is the house in which Dorothy lives. As for Auntie Em, “The sun and wind . . . had taken the sparkle from her eyes and left them a sober gray; they had taken the red from her cheeks and lips, and they were gray also. She was thin and gaunt, and never smiled now.” And “Uncle Henry never laughed. . . . He was gray also, from his long beard to his rough boots.” The sky? It was “even grayer than usual.” Toto, fortunately, was spared grayness. He “saved [Dorothy] from growing as gray as her other surroundings.” He was not exactly colorful, though his eyes did twinkle and his hair was silky. Toto was black.

Out of this grayness—the gathering, cumulative grayness of that bleak world—calamity comes. The tornado is the grayness gathered together and whirled about and unleashed, so to speak, against itself. And to all this the film is astonishingly faithful, shooting the Kansas scenes in what we call black-and-white but what is in reality a multiplicity of shades of gray, and darkening its images until the whirlwind sucks them up and rips them to pieces.