#dnvp

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

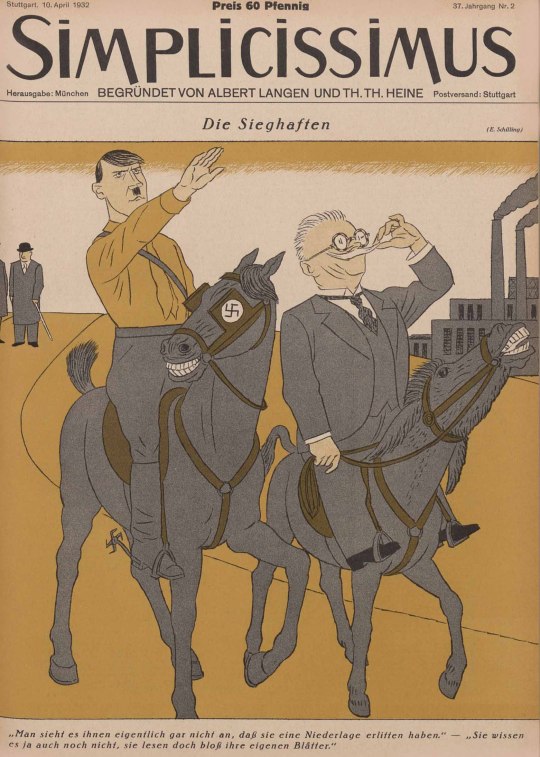

“Die Sieghaften [The victorious.],” Simplicissimus. Vol. 37, issue 2, April 10, 1932. Cover page.

Two men converse about Adolf Hitler, riding a blinkered horse, and Alfred Hugenburg, riding an ass: “Man sieht es ihnen eigentlich gar nicht an, daß sie eine Niederlage erlitten haben.” "Sie wissen es la auch noch nicht, sie lesen doch bloß ihre eigenen Blätter" [“You don't really see that they have suffered a defeat.” "They don't know it yet either, they're just reading their own papers"]

#simplicissimus#weimar republic#weimarer republik#weimar germany#crisis of the weimar republic#gravediggers of german democracy#alfred hugenberg#nsdap#dnvp#führerprinzip#reichspräsidentenwahl 1932#1932 german presidential election

1 note

·

View note

Text

#I Love You Friends ❤️🥀🌹#❤❤❤#beautychallenge#postinflammatoryhyperpigmentation#PhotoEditingChallengess#bestphotochallenge#postingchallenge#photographychallenge#beautifulchallenge#smilechallenge#photographyphotochallenge#crushqueen#queenchallenge#ChallengeAccepted#bestphotochallengeToday#BestPhotographyChallenge#HelloGuys#DNVP#DivyaNSp#Mahimalovelife

1 note

·

View note

Note

Still haven't the foggiest idea on why the dems are so caught up in the whole off-brand DNVP thing where they only have "were not the other guys!!!1!" going for them.

AND Abandoning your main base for the potential of a new (smaller) base on the assumption that main base is just going to stick around out of obligation is just fucking stupid.

Didn't work for coca-cola in the 80's and its sure as hell not gonna work for the dems.

they're trying to create a countrywide summoning circle to put some life back in genocide joe

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

okay, real quick [not so quick as it turns out, you will notice these get longer as i go on for basically no reason; this is as succinct as i get i think]:

italy (1914–1925): oligarchic/corrupt liberal parliamentary system, relatively weak + poor among the great powers, frustrated territorial ambitions despite a handful of colonies. heterogeneous radical nationalist movement (stretching left to right on various issues) in wwi advocates participation in the war for various conflicting reasons, and then sticks around after the war ends—at the same time as the national humiliation of unsatisfied territorial demands, a brief economic recession, problems w veteran demobilization, proto-revolutionary labor unrest, and the general collapse of politics-as-usual. radical nationalists generally consolidate into two camps, 1) a more radical and popular one behind mussolini ("fascists"), built mostly on the use of armed force against rural socialists (and to seize control of local govt) but also including a pro-worker 'left' faction, 2) a more reactionary, pro-business, monarchist, etc clique (ani). mussolini is handed power after a show of force in rome in 1922 but presides over a seminormal conservative govt (what we might call 'illiberal democracy' today?) until the fascist murder of the socialist leader giacomo matteoti in 1924; the ensuing crisis eventually forces mussolini to stand before parliament in 1925 and declare an outright dictatorship, but the regime that emerges in the late 1920s represents a series of compromises and the input of multiple, fascist + nonfascist (esp. the ani), contending factions

germany (1918–1933): late to imperialism and industrialization but caught up fast, becomes the industrial heart of europe under an increasingly militaristic authoritarian monarchy. stripped of colonies and much of its european territory after wwi, briefly succumbs to a communist rev that's crushed by the new post-imperial liberal democracy. diverse and aggressive far right subculture variously focused on imperial restoration, territorial aggrandizement, antisemitism, etc. german workers' party, working-class offshoot of a racialist occult sect, is among these groups and is quickly commandeered by adolf hitler and the adjective 'national socialist' added. radical nationalist ecosystem feeds off of national humiliation of defeat, abdication, etc etc, economic crisis, veteran problem, and continued impositions by france. nazi attempt to exploit a serious crisis in 1923 and take power by force fails, party banned and hitler imprisoned, during which time he fleshes out a sophisticated ideology of, basically, revolutionary racism, entailing complete dictatorship, social levelling and worker mobilization, new imperial conquests to the east, and extermination of racial inferiors. hitler released from prison early and gets party unbanned, great depression in 1929 catapults the nsdap into national politics, claiming a third of the vote by 1932. to the nazis' 'right' arguably are the dnvp (authoritarian, monarchist, pro-business) and the vaguely authoritarian presidential clique clinging to power by emergency rule as of 1930. nazi militia attacks leftists in the streets but also tries to rally workers and supports the late 1932 berlin transport strike; despite apparent radicalism, hitler promises industrialists he's their best option and so they pressure the weak/collapsing presidential regime to bring the nazis into the fold. this occurs as a result of internal squabbles in the conservative camp when hitler is named chancellor in early 1933, and only a few months of 'illiberal democracy' ensue before the nazis install a single-party dictatorship and, more specifically, begin consolidating much more total party control over the state and traditional elites than the italian fascists ever managed

spain (1930–1937): neutral in wwi. declining imperial power; largely poor, weak, and agrarian, similar to italy; conservative dictatorship overthrown in 1930, king rules as interim dictator until new elections act as de facto referendum on the monarchy: republicans sweep the cities in a landslide, the king goes into self-exile, and a liberal democracy is proclaimed. radical nationalist subculture partially inspired by what's going on in italy seeks restored authoritarian catholic monarchy. a young intellectual called ramiro ledesma ramos, like the nazis and fascists, preaches something beyond that, a revolutionary totalitarian republic based on worker mobilization and sweeping expropriations + nationalizations. he joins w an extreme catholic in 1931 to form the jons, composed of radical university students. in 1933, the aristocratic lawyer and dictator's son, josé antonio primo de rivera, founds his own fascist-inspired 'falange', somewhat more catholic and moderate; the falange wins two seats in parliament w help from the mainstream right. the year later the falangists and 'jonsists' merge, though josé antonio soon consolidates autocratic control w/in the party and kicks out ledesma. although increasingly violent towards leftists, the falange remains a minuscule and mostly irrelevant force. the rise of the popular front in 1936 sees a state crackdown on the falange and josé antonio's arrest, after which he begins plotting for armed insurgency; however, the military takes the initiative and stages a coup which becomes a civil war. the falange balloons in membership and joins the rightist 'nationalist' camp. w most of its old leadership executed by republicans, the nationalist generalissimo francisco franco coopts the falange and converts it into his personal power base in 1937, gradually purging the falange of authentically fascist elements over the next several years.

romania (1923–1941): not only victorious in wwi but, unlike italy, gets massive territorial concessions largely satisfying any lingering irredentism. no colonial history except that of its own colonization. deeply impoverished and agrarian society + oligarchic/corrupt liberal parliamentary system, w a looong history of antisemitism. jews are only granted civil rights in 1923; in the same year, professor and antisemitic politician a.c. cuza founds the lanc: aggressively anti-jewish on an almost single-issue basis. within the lanc is a faction of university students banking on the student protest movement of the early 1920s; their leader, corneliu codreanu, thinks cuza should go beyond electoral activity and build an armed mass movement capable of mobilizing a) students like himself, and b) the peasantry, or in other words the students' parents. this results in the codrenists splitting from the lanc in 1927 as the 'legion of the archangel michael' espousing a semiheretical and mystical school of orthodox christianity, genocidal antisemitism, and a sort of peasant socialism. over the 1930s the legionaries do in fact become an armed mass movement of the youth and peasants, and a persistent thorn in the side of the oligarchic establishment, at one point assassinating a prime minister. politics finally grinds to a halt in 1937, when the national christians (authoritarian, antisemitic, but not revolutionary; successor to the lanc, w a love-hate relationship to the legion) are hoisted into govt. the nc administration proves too friendly to the legionaries and instead, in 1938 king carol seizes power from above, creating a royal dictatorship w a vague/amorphous single party collecting members of the old oligarchy. codreanu is assassinated and the legion declares all-out revolutionary war on the state, but unsuccessfully. they remain a threat though; in 1940 carol changes tack and tries to coopt the legion, but his regime breaks down and he abdicates in favor of military dictator ion antonescu, who more fully absorbs the legion into govt in a franco-like arrangement. unlike franco who was able to slowly marginalize the falange, the legion's unruliness makes it an unsustainable partner: a 1941 legionary revolt turns into a horrific pogrom and antonescu purges it in the most brutal and decisive anti-legionary crackdown yet. this doesn't stop the more 'orderly' and pragmatic antonescu regime from participating enthusiastically in the holocaust.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ich kenne Aegidius persönlich und schätze ihn sehr. Aber hier muß ich ihm widersprechen.

Vor 2015 hatte die CSU eine Phase, in der sie dem Zentrum ähnlicher war als der DNVP. Bis 1988 (Strauß) und seit 2015 (Seehofer) ist sie der DNVP deutlich näher.

Es waren Zentrum und DNVP zusammen, die Hitler auf den Thron brachten.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the demonology of the West, for nearly a hundred years the rise to power of Adolf Hitler has played a leading part. Nearly everyone knows, or thinks he knows, though he is wrong, that “the Germans elected Hitler,” with the apparent lesson that a people can go bad and democracy must never be allowed to repeat such an error. Few, however, actually know the nuts and bolts of how Hitler came to power. This fascinating book fills that gap, by offering a day-by-day account of the national politics of the Weimar Republic from November, 1932 until the end of January, 1933. And it is certainly true that lessons are strewn everywhere in this story, though they have nothing to with reinforcing our own fake democracy. The authors, two German journalists, Rüdiger Barth and Hauke Friederichs, write a present-tense narrative covering each day, based on daily newspapers, as well as on other in-the-moment documents such as diaries and letters, along with secondary sources. Each day’s entry is headed by excerpts from the mainstream papers of the time, usually with wildly divergent presentations and calls to action (a phenomenon strange to us, of which more later). The authors do a good job of sketching the personalities of everyone involved, and of making clear what can be known and what must be surmised from the evidence. It sounds like such a narrative would be choppy, but the result is actually quite compelling, if not analytically deep.

…

A fundamental procedural problem was that Parliament for some time had had a “negative majority”—there were enough votes to obtain a vote of no confidence against any Chancellor, as enemies cooperated for that limited purpose, but not enough votes to form a majority that could stand behind a Chancellor. The most recent elections for the Reichstag (the main, lower house) had been held on November 6, 1932. A third of the seats were obtained by the National Socialists (NSDAP). Twenty percent and sixteen percent were held by the Social Democrats (SPD) and Communists (KPD) respectively—both parties of the extreme Left, but violent enemies, because the Moscow-directed KPD had been instructed that the slightly-more-centrist SPD was just as much the enemy as the NSDAP. The only other two parties of note were the centrist Centre Party, a Catholic (largely Bavarian) party, at twelve percent, and the conservative German National People’s Party (DNVP), led by the powerful media baron Alfred Hugenberg. Americans are used not only to an allegedly two-party system, but also to much more monolithic political activity. They are not accustomed to anything like the fractured atmosphere of late Weimar Germany, where many interests aggressively competed—not just political parties, but also powerful independent forces such as trade unions and the National Rural League (representing landowners), which were not aligned with a specific party. For decades in America, the Left has acted in unison, cooperatively crafting and rolling out a program which is then broadcast by Regime media to create the Narrative, then implemented and enforced by every powerful “independent” group in the country. In and through this process, every element of the Left coalition is rewarded and continually supports the collective line (though the recent wars in Israel have caused some cracks in this cozy setup, for the first time). The pretend opposition of the Republican Party cooperates with the Left’s program in exchange for social and material rewards. As a result, today the American system is close to a one-party state. We therefore find it hard to grasp the chaos that a system like Weimar embodied.

…

We begin on November 17, the day Papen resigned as Chancellor, when it became clear his cabinet refused to continue to support him. Papen was a protégé of the Defense Minister, Kurt von Schleicher, who had also turned against him, in part hoping to become Chancellor himself. The past six months had been uneasy months; among other crises, Hindenburg had dissolved the government of Prussia, the largest and most important state, and effectively administered Prussia by decree, the legality of which was winding its way through the courts. The question of the hour was how a new government could be formed that had any strong degree of support. A government of the Left was out of the question—not only because the Left parties did not cooperate with each other, and even collectively did not have anything approaching a majority, but because such a thing was unthinkable to Hindenburg and pretty much everyone else in the ruling classes. The obvious play was some combination of the National Socialists, the DNVP, and the Centre Party, who agreed on quite a bit. But the National Socialists were not playing nice with the government. They had no cabinet seats, as a result, and no direct access to federal power. Hitler had already rejected a proposal to make him Vice-Chancellor or give the NSDAP some minor cabinet posts. He regarded any attempt to bring the NSDAP into the government that did not include him as Chancellor as a non-starter, a mere attempt to coopt the National Socialists into working for a government that opposed their interests. His analysis was correct, of course—nobody in power actually wanted the NSDAP to have any real say in government. None of the men in charge liked the National Socialists, whom they regarded as vulgar upstarts, prone to gutter street fighting and openly contemptuous of the very existence of the Republic. The NSDAP, however, was behind the eight ball—they needed money (men of the SA, the Sturmabteilung, the National Socialist paramilitary force, with collection boxes, begging on behalf of the Party, were ubiquitous in the streets), and votes for the NSDAP had dropped significantly in the November election. Moreover, they were wracked by internal struggles, notably between Hitler and Gregor Strasser, who wanted more focus on socialist/distributive economics and other “third position” policies. Papen’s resignation meant that Hindenburg had to form a new government—but he wanted one that still excluded the NSDAP, and he certainly wasn’t going to include the Communists, or the Social Democrats, so forming any government was a challenge. The only way to pass something in Parliament was for either the Communists or National Socialists to vote for it, usually not because they favored a proposal, but because it harmed their opponents. (The Communists expected if the NSDAP came to power that they would gain, not lose, power themselves. Conversely, and a fact buried nowadays, most observers expected, if the NSDAP collapsed, that many of its members would move to the Communists.) Hindenburg met with all the key political players, including Hitler, as well as non-political players, such as leading industrialists and landowners. In fact, much of this book is the description of meetings between men of power—some private, some not, some meant to be private and made public by one mechanism or another. He tried repeatedly to get some powerful politician, any powerful politician other than Hitler or someone on the Left, to try to form a coalition government. All refused, or quickly failed in their attempts.

…

The Ministry of Defense spent much time wargaming whether the military could put down an alliance between the Communists and the NSDAP to permanently overthrow the Republic through a general strike. That may seem like an odd fear, but the two parties had cooperated in smaller-scale actions of this type before. Moreover, in the European context, this kind of general strike is more-or-less a euphemism for civil war, given that the aims of a general strike are massive and permanent governmental change, and that the instigators assume that violence will accompany a general strike. How likely any of this was is anyone’s guess, but the focus on it (and Schleicher’s involvement in it) show the pressure on Hindenburg to form a stable government that could avert this kind of outcome.

…

Reading all this, you get the feeling of watching a whirring hamster wheel, all these men running in place and getting nowhere. That they were smart and serious men did not prevent them from ending up in a situation that they all (except Hitler and his allies) were trying to avoid. It is not surprising; history offers many examples of disasters not avoided, despite the best efforts of competent, educated, far-seeing men. As always, there was no grand plan by some group behind the scenes; there never is, as much as many like to believe in such fantasies. Everything that happened emerged from the obvious, mostly public, efforts of many men both to advantage themselves and to do what they thought right for the Germans. That is just as true for 2024 America, omitting the part about doing right for the country. But what history does not offer is any example of a society such as ours, where the ruling classes are utterly dominated by the exact opposite of those in the Germany of 1932—rather we have incompetent, uneducated, stupid men and women, dominated by the latter, with the former being feminized, in thought and manner, in a way that would boggle the mind of any decisionmaker in Weimar. Thus, we don’t have the cushion that existed in Weimar, which still fell into disaster. Therefore, we can be sure that when crisis arrives here, the ground will come up even faster to meet us as we fall, not because there is nobody at the helm, but because of something worse—those at the helm are incapable, from a combination of malice and ineptitude, on every level.

…

So what? This was all long ago. But it matters, because we pretend desperation is not also our reality. True, at this moment, it is perhaps not our reality to the same extent as Weimar, where unemployment was thirty percent, and many did not know where their next meal was coming from. But at least Germany was a high-trust, homogenous society with an economy based on producing actual value, whereas we are—not. Certainly, huge swathes of our country are suffering quietly, unable to have any part of what used to be the standard American life. They are instead pumped full of, and killed with government approval by, Chinese and Mexican fentanyl, while they survive on handouts and gig jobs. They are sedated and kept quiet by government checks, weed, and the internet, games and porn, combined with threats and punishments for anyone who dares fight back or act like a man should. Without these suppressants, America would long since have exploded, and rightly so.

…

We often hear that our times are a pale imitation of the past, a variation on Nietzsche’s Last Man. Where are the crowds in the street, baying for their preferred political solution? Where are the brawls between competing factions? Where are the political assassinations? No doubt every time is different, and we seem a desiccated society. But I suspect, for both good and bad, we are not desiccated at all—merely asleep, artificially tranquilized. When that spell is broken, something new will emerge. Let’s hope it’s something good.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Adolf Hitler s'incline devant le maréchal Paul von Hindenburg pour l'accueillir devant l’église de la Garnison à Potsdam - Journée de Potsdam - Allemagne - 21 mars 1933

Photographe : Theo Eisenhart

©Deutsches Bundesarchiv - 183-S38324

Le Président allemand Paul von Hindenburg, le Ministre de la défense Werner von Blomberg et le Chancelier Adolf Hitler devant l’église de la Garnison à Potsdam – Allemagne – 21 mars 1933

Photographe : Georg Pahl

©Bundesarchiv - Bild 102-16082

La journée de Potsdam

Suite aux élections législatives de novembre 1932, Adolf Hitler est nommé Chancelier de la République de Weimar le 30 janvier 1933 bien que sa popularité dans les urnes a baissé (perte de 2 millions de voix et de 34 sièges au Reichstag).

Au bout d'un mois d'intrigues menées au plus haut sommet par l'ancien chancelier Franz von Papen avec le soutien de la droite, d'industriels et du Parti Populaire National Allemand (DNVP) le Président Paul von Hindenburg consent à le nommer à ce poste.

Dès le 1er février 1933, Hitler persuade Hindenburg de dissoudre le Reichstag. Les neuvièmes élections fédérales allemandes du 5 mars 1933 donnent la majorité des sièges au parti nazi (NSDAP) sans toutefois obtenir la majorité absolue en vue de faire adopter sa loi des pleins pouvoirs.

Suite à l'incendie du Reichstag dans la nuit du 27 au 28 février, dont la responsabilité a été attribuée aux communistes selon les nazis, il fallut trouver un endroit pour accueillir le nouveau parlement et solenniser le début de la nouvelle législature en rassurant les milieux conservateurs et religieux sur la fidélité et la continuité des traditions allemandes du projet hitlérien. A cette fin, Hitler doit s’assurer du soutien des conservateurs et du parti catholique du Zentrum pour adopter à la majorité des deux tiers son projet de loi des pleins pouvoirs qui lui octroierait le droit de gouverner par décret.

L’église de la Garnison de Potsdam, sanctuaire de la tradition prussienne, fut choisie pour cette cérémonie, le jour anniversaire de l’inauguration du premier Reichstag de l’Empire allemand par le chancelier Otto von Bismarck en 1871.

Le lendemain de la cérémonie, les deux premiers camps de concentration officiels furent établis à Dachau et à Oranienburg.

Deux jours plus tard, la loi des pleins pouvoirs fut adoptée et marqua le début de la dictature nazie.

#WWII#avant-guerre#pre-war#nazisme#nazism#journée de potsdam#potsdam day#hitler#von hindenburg#von blomberg#potsdam#allemagne#germany#21/03/1933#03/1933#1933

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Von Papen, ou l'histoire du pyromane qui jouait avec le feu

« Après les élections, le cabinet Schleicher est formé. Kurt von Schleicher, ancien ministre de la défense, et partisan d'un gouvernement autoritaire que le Parti national-socialiste des travailleurs allemands (NSDAP) soutiendrait, reprend à peu de chose près la composition de l'impopulaire cabinet Papen, composé de personnalités non affiliées. Néanmoins, von Schleicher ne réussit pas à affermir son faible pouvoir et voit poindre la menace d'une motion de censure lors de la nouvelle session parlementaire. Fin janvier, à la suite de multiples intrigues, von Papen convainc le président Hindenburg de nommer un gouvernement de coalition NSDAP-DNVP, avec Hitler à sa tête. L'armée joue un rôle dans ces intrigues, ainsi que la perte de confiance de von Papen et Hindenburg à l'égard de von Schleicher.

Finalement, Adolf Hitler est nommé chancelier le 30 janvier 1933 et forme un cabinet où se trouvent trois membres du NSDAP. Ouf ! La démocratie était respectée, et la bête immonde était sous contrôle, puisqu'en minorité dans le gouvernement. Il ne restait plus qu'au peuple de constater l'incompétence d'Hitler. Mais le pyromane, qui se croyait maître du feu qu'il avait contribué à nourrir, se fit dépasser par sa créature.

Les élections de novembre 1932 sont les avant-dernières élections législatives de la république de Weimar (avant celles de mars 1933) et les dernières considérées comme libres : à la suite de l'incendie du Reichstag le 27 février 1933, le Reichstagsbrandverordnung suspend les libertés civiles. Pris le lendemain, par le président de la République, le maréchal Hindenburg, ce dernier suspend l'essentiel des libertés politiques et civiles. Il s'agit du premier des textes d'ordre législatif ou réglementaire qui conduisent l'Allemagne de Weimar à devenir en quelques mois un État totalitaire : tous les partis politiques ou organisations syndicales sont dissouts. Le Parti communiste est ainsi interdit le 6 mars, suivi du parti social démocrate le 22 juin, du Zentrum le 5 juillet, et de l'allié même des nazis, le Parti populaire national allemand, le 29 juin. En parallèle, l'ensemble des syndicats sont dissouts par le gouvernement nazi qui crée le 2 mai 1933 l'Arbeit Front, censé représenter l'ensemble des travailleurs allemands. Le 14 juillet 1933, le parti nazi (NSDAP) est ainsi la seule organisation politique autorisée en Allemagne. »

Errare humanum est, perseverare diabolicum L'erreur est humaine, persévérer est diabolique

0 notes

Text

Das Zitat gibt die tatsächlichen Verhältnisse nur unzureichend wider.

Die (damals noch sozialdemokratische) SPD erreichte mit 32% die deutliche Mehrheit der Stimmen, doch aufgrund eines impliziten Unvereinbarkeitsbeschlusses durch die Bürgerlichen konnte sie keine Regierung bilden.

Stattdessen koalierte Erwin Baum vom Thüringer Landbund mit der NSDAP, der DVP, WP und DNVP. Sämtliche nationalkonservativen, rechtsliberalen, bürgerlich-mittelständischen Parteien wollten die Sozialdemokratie verhindern und legten sich daher mit der NSDAP ins Bett.

Der Nationalsozialist Wilhelm Frick wurde Minister für Inneres und Volksbildung und stellvertretender Vorsitzender der Regierung. Er entfernte Kommunisten und Sozialdemokraten aus den Ämtern, füllte dafür die Polizei mit Nationalsozialisten und schuf einen rasseideologischen Lehrstuhl an der Universität Jena. Am 1. April 1931 schied er nach einem Misstrauensantrag aus der Regierung aus - der Schaden blieb.

Das passiert, wenn man Faschisten "einfach mal machen lässt, damit sie sich selbst entzaubern".

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

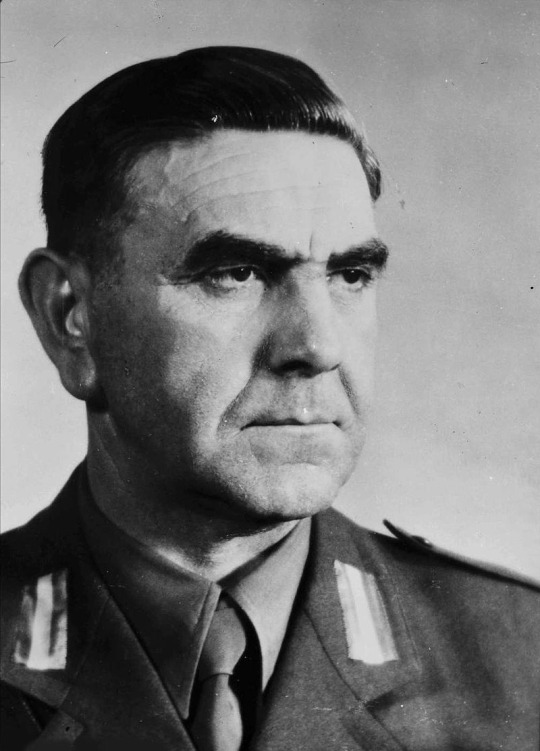

Wilhelm Reinhard - Der erste Präsident des Volkstags

Aus der PAZ: »Dem am 4. September 1860 in Neuwied in der preußischen Rheinprovinz geborenen Landwirtssohn Wilhelm Reinhard schwebte alles andere als eine politische Karriere vor, als er 1878 begann, evangelische Theologie zu studieren. Schon mit 23 Jahren wurde er zum Predigtamt der Evangelischen Landeskirche der älteren Provinzen Preußens ordiniert. Nach einem Vikariat in der Kurmark wurde er Domhilfsprediger in Berlin. 1888 trat er sein erstes Gemeindepfarramt in Paplitz in der Mark Brandenburg an. 1895 wurde er erster Pfarrer und Superintendent im westpreußischen Freystadt. Mit nur 39 Lebensjahren wurde er 1899 Konsistorialrat und erster Pfarrer an der Oberpfarrkirche von St. Marien und zugleich Stadtsuperintendent in Danzig. Seine Amtseinführung vollzog der Oberhofprediger Ernst von Dryander aus Berlin. Mehr als 600-mal stand Reinhard auf der Kanzel von St. Marien. 1911 wurde er zusätzlich Generalsuperintendent der Provinz Westpreußen. Die Universität Königsberg verlieh ihm 1917 den theologischen Ehrendoktor. Mit dem Ende des Ersten Weltkrieges und dem Friedensdiktat von Versailles wurde Danzig wie das Memel- und Saargebiet unter Völkerbundverwaltung gestellt. Nach fast 20-jähriger Tätigkeit als Superintendent wechselte der Patriot nun in die Politik. 1920 wurde er als Listenerster der Deutschnationalen Volkspartei (DNVP) in die verfassungsgebende Versammlung Danzigs gewählt. Als stärkste Fraktion hatte die DNVP das Vorschlagsrecht für das Präsidentenamt. Reinhard wurde am 14. Juni 1920 zum Präsidenten der verfassungsgebenden Versammlung und später auch des ersten Volkstages der Freien Stadt Danzig gewählt. Reinhard verstand es, das Vertrauen sowohl der Danziger als auch des Völkerbundes zu gewinnen. Ihm ist es zu verdanken, dass eine Neutralitätserklärung in die Verfassung des jungen Staates hineingeschrieben wurde. Damit konnte er polnische Ansprüche abwehren und der Bevölkerung, die zur Zukunft ihrer Stadt nicht gefragt worden war, wieder Vertrauen in die Politik zurückgegeben. Als der neue Stadtstaat in ruhigere Fahrwasser kam, verließ Reinhard Danzig und widmete sich wieder seiner kirchlichen Arbeit. Nach einem Zwischenaufenthalt in Berlin, wo er zum Präsidenten der Preußischen Verfassungsgebenden Kirchenversammlung gewählt wurde, wechselte er Ende 1920 als Generalsuperintendent nach Stettin in Pommern. Dort starb er am 17. Dezember 1922 mit 62 Jahren infolge eines Herzinfarkts. Er fand in der Schlosskirche in Stettin seine letzte Ruhestätte. http://dlvr.it/SfRTq9 «

0 notes

Note

Where the Nazis Left Wing? They were called National Socialist after all.

No

Thats all folks

Ok seriously, sorry if i’m being rude but I only ever heard this argument made by bad faith actors or gullible folks who just know nothing about 1930s Germany. THe Nazis as a Left Wing extremist organization is the type of thing that Far Right Pundits argue in books that they know will only sell to people who have no understanding of history and only consume Far Right Media, so I honestly kinda consider this question almost beneath me, but ok fine lets explain something which is super obvious.

(pictured, not leftists)

yes, the Nazi party, and almost all Fascist movements for that matter are/where Right Wing. If that wasn’t obvious by their beliefs (value traditionalism, patriarchy, anti immigrant, belief in hierarchy, conservatism) then it should be obvious by their choice of allies and enemies.

See when the Nazi Party ran for goverment during the Weimar Republic, they were allied with other political parties because you know....European Parliamentary politics. Infamously, in the 1933 election, the Nazis were only able to get 49% of the vote (despite massive voter suppression, cheating, and violence against the opposition). Hitler was only able to get the majority he needed to ally with other parties, specifically the German National People’s Party (Deutschnationale Volkspartei) or DNVP. THe DNVP was a conservative-Nationalist party who were the successor to the old pre WWI German Conservative Party.

In fact it was the DNVP which lead to the election of Hindenburg as President of Germany in 1925, and remember it was Hindenburg who appointed Hitler Chancellor after the 1932 election. This was part of the larger Hazburg Front, basically an alliance of all the Right Wing Parties to form a majority in the Parliament. This including the DNVP, the Nazi Party, as well as the Conservative Agricultural League.

(they had a very stupid logo)

They were also allied with the Pan-German League, a different German Nationalist Party, as well as the German People’s Party, who were a conservative Party. All of these groups would work together to ensure the Nazi seizure of Power in 1932-1933 before Hitler finally completely seized power for himself.

(The guy on the Right is the Hidenburg the Head of the Conservative Party, appointing Hitler Chancellor)

Another party worth mentioning here aws the German Centre Party (Zentrum) which was a Catholic Centrist Party which leaned conservative, who would eventually support Hitlers seizure of power. While they included left wing elements, the party as a whole included was Center Right, believing in the basic conservative principles you can find anywhere. They made the mistake of viewing Hitler as the lesser of two evils.

(Picture not Related)

Or even look at this internationally. The Nazi Party allied itself with Right Wing governments, from Franco in Spain to Mussolini in Italy, to the Governments of Hungary, Romania, and Croatia. Their allies in Vishi France were the Right, the Nazi allies in within the Soviet Union consisted of many right wing regimes, again and again you see the Nazis ally themselves with Far Right organizations. THis is at its most obvious with Imperial Japan, which was governed by a fanatically far right goverment. What all of these groups shared was a hatred of leftists of all stripes, in particular communist, and joint anti communist principles would prove to be the lynchpin of most of their groups. And this continues to this day, Nazi organizations identify with the right, even if they don’t necessarily support a specific party. It is no coincidence that the Neo Nazis in the US today call themselves the Alt-Right.

Basically if the Nazis were Leftists, they wouldn’t ally themselves with internationally with Right wing leaders. Here are some pictures of Nazi allies, guess which ones are leftists

....Thats right, fucking none of them.

The only reason why people seem to buy this is because of the term National Socialist, and if you had bothered to look this up, you’d know that it is because the term Socialism had different meanings in 1930s Germany than they do in America today. Basically the Nazis meaning of socialism was “take shit from non Germans and give to us” which is generally known as IMperalism. If you want more information, check out this article from Vox which explains it with more patience than I LINK

Now there were more socialist inclined Nazis when the Party was first founded like the Strasser brothers, but when Hitler took over the party he had many of these people purged from the party. In fact the left wing of the Nazi Party was largely killed in the Knight of Long Knives, though even calling them left wing is pretty far since they seemed to want “socialism but only for Ayrans”.

(never Trust Nazis...no not even then)

HItler himself basically hoped to co-opt the term socialist and the color red specifically to confuse leftist, a political strategy that experts call “U mad bro?”

Now Nazis were somewhat anti capitalist, but only in the sense that they felt both Communism and Capitalism were created by Jews who controled the world, because again, the Nazis were fucking idiots.

Now while Nazism is right wing, until 2015 I would say it wouldn’t be fair to compare Americna Right wing Political parties with the nazis except in the vaguist terms, but with the election of DOnald Trump, we have actual fascists in office now so...thats not good.

#ask evilelitest#National Socialist#Nazism#Right Wing#Left Wing#weimar republic#1933 German elections#Adolf Hitler#Night of Long Knives#Alt Right#Fascism#Far Right#Racism#Conservatism#DNVP#Gamergate#Neglected Historical Fact

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello my fellows! There are Idiots here in Germany, who think that we live in a dictatorship and that 2020 is pretty much the end of everything. So I dived into 1920 and I am going to Post a few things to proove that this is wrong. Pictures are from wikipedia

The treaty of Versailles was singned im the 28th of June in 1919. On the right it shows 1920. The treaty was activated on the 10th of January 1920 and turned 100 this year. The elections in Eastprussia, Pommerania Schleswig-Holstein and Upper East-Silesia were delayed. The people there first voted wether they wanted to remain German or not. It took 3 years till 1922.

The treaty of Verailles caused a shift. Pommerania Eastprussia and the remains of Westprussia strictly voted for the right wing. The DNVP (German National People's party) was against the treaty and for the resurection of the German Empire. These provinces voted for the right wing all the way through till 1933 with minor changes. At that time the DAP ( later known as NSDAP) gained popularity in Munich (Bavaria). Hitler already was a member and became the propaganda-leader.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Kapp Putsch

Members of the Ehrhardt brigade in Berlin on March 13. The swastika was not at this point exclusively associated with the Nazis (at this point a minor political party that was too far removed from Berlin to play a significant role in the putsch before it collapsed), though the symbol clearly had strongly reactionary connotations at this point.

March 13 1920, Berlin--Despite provisions in the Versailles Treaty against them, and the end of German involvement in the Baltic, the German right-wing paramilitary Freikorps remained a powerful force in Germany. On February 29, war minister Noske ordered the dissolution of two of the largest Freikorps groups. One of them, the Marinebrigade Ehrhardt, refused to comply, and received backing from the commander of Berlin’s regular army troops, General Lüttwitz, who demanded (among other things) a dissolution of the National Assembly and new elections for the Reichstag. When Chancellor Ebert did not accede, he ordered the Ehrhardt brigade into Berlin to seize government buildings; they began to move at 10PM on March 12.

No regular military troops resisted the Ehrhardt brigade. In an emergency session at 4AM on March 13, Ebert’s cabinet decided (with significant dissent) to flee the city for Dresden (and when that city proved unfriendly, Stuttgart) and to call for a general strike against the putsch. The meeting was cut short so that they could avoid capture by the Freikorps. Lüttwitz installed Wolfgang Kapp, from the right-wing DNVP, as the new chancellor. He was also joined by Ludendorff (who had largely been out of the picture since his sacking in the final weeks of the war) and con man and “spy” Trebitsch-Lincoln, who served as his press censor.

Ebert’s call for a strike was wildly successful; by March 15, over twelve million workers were participating. Lüttwitz’ position became untenable, and the non-left-wing parties attempted to ease him out of Berlin. On March 18, Lüttwitz resigned and the Ehrhardt brigade left Berlin (shooting some civilians who jeered at them while they did so) and Ebert’s government returned to Berlin two days later.

Ultimately, despite its failure, the results of the Kapp Putsch were a victory of sorts for reactionary forces in Germany. Lüttwitz’s allies did eventually get many of their demands anyway; the National Assembly would be dissolved the next month and Reichstag elections were moved forward. The Freikorps continued its prominent role in post-war Germany, as in the coming weeks they were used to end the general strike in the Ruhr (which had continued after the end of the putsch). A right-wing government took control of Bavaria at the same time, and Ludendorff continued his political intrigues there.

#wwi#ww1#ww1 centenary#ww1 history#world war 1#The First World War#The Great War#ludendorff#ebert#kapp putsch#march 1920

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Los socialistas abandonan el NSDAP

Por Otto Strasser (1)

4 de julio de 1930

Lectores, camaradas, ¡amigos!

Con profunda preocupación hemos contemplado en los últimos meses la evolución del NSDAP y con creciente recelo nos hemos visto forzados a observar cómo cada vez más a menudo y en cuestiones cada vez más importantes el partido entra en conflicto con la idea esencial del nacionalsocialismo.

En numerosas cuestiones de política exterior, de política interior y, sobretodo, de política económica, ha ido tomando el partido un posicionamiento que cada vez con mayor dificultad puede considerarse acorde con el espíritu de los 25 puntos (*2), en los cuales nosotros vemos el único (y exclusivo) programa del partido. Y todavía mucho más que eso ha pesado el creciente aburguesamiento del partido, una primacía de los intereses tácticos sobre los principios fundamentales, y la preocupante caciquización del apartado del partido, el cual cada vez más se ha convertido en la meta del movimiento y ha puesto sus intereses por encima de las exigencias programáticas de la Causa.

Nosotros habíamos comprendido y comprendemos aún al nacionalsocialismo como un movimiento conscientemente antiimperialista, cuyo nacionalismo se centra en la conservación y protección de la vida y el desarrollo de la Nación Alemana, sin ninguna clase de tendencias dominantes sobre otros pueblos y tierras.

Para nosotros había sido y sigue siendo aún, la negación del intervencionismo contra Rusia del capitalismo internacional y del imperialismo occidental, una exigencia esencial resultante tanto de nuestra ideología fundamental como de la necesidad de una política exterior propiamente alemana (*3). Alrededor de esto, hemos considerado las posturas de la dirección del partido cada vez más abiertamente favorables a una guerra de intervención, como contraria a la causa Nacionalsocialista y a las necesidades de una política exterior alemana.

Para nosotros había sido y sigue siendo todavía la solidaridad con el pueblo indio en su lucha por su libertad del yugo inglés y la explotación capitalista (*4) una necesidad, la cual se resulta del hecho de que para una política de liberación alemana, cada debilitamiento de los poderes tras el Pacto de Versalles (*5) es favorable, así como la afirmación por la lucha de cualquier pueblo oprimido contra la explotación de los usurpadores, ya que es consecuencia forzada de nuestra idea del nacionalismo, que el derecho a la autoafirmación de cada pueblo a su manera, lo que nosotros exigimos para nosotros, también corresponda a los demás pueblos y naciones.

En este aspecto para nosotros el concepto liberal de las “bendiciones de la cultura (civilizadora)” nos es completamente desconocido.

(N.d.E.: Para Otto y Gregor Strasser, el Nacionalsocialismo era una ideología enteramente aplicable por otras Razas y Culturas, de acuerdo a su propia realidad, y no limitada por ello exclusivamente a los alemanes. En este párrafo queda de manifiesto, además, que Otto no concebía la idea de “superioridad cultural”, que es completamente contradictoria con una concepción “Nacional” -es decir, diversa- del mundo).

Nosotros habíamos sentido por lo tanto la política de la dirección del NSDAP, la cual a menudo tomó partido por el imperialismo británico contra la libertad de la India, contrario a los intereses esenciales del Nacionalsocialismo.

Nosotros habíamos entendido y seguimos entendiendo al Nacionalsocialismo según toda su naturaleza, como un movimiento alemán, cuya labor en el interior del Estado no es únicamente es la creación de una Gran Alemania Popular, con el rechazo de pequeños estados separados y privilegios particulares basados en criterios dinásticos, religiosos o puramente arbitrarios (¡Intervención Napoleónica!) (*6), los que impiden la reunificación de todas las fuerzas nacionales, imprescindibles para la liberación y la autodeterminación de Alemania. Nosotros hemos sentido por lo tanto la cada vez más abierta toma de posición de la dirección del partido a favor de este sistema de estados y privilegios particulares, cuya salvación e incluso ampliación fue proclamada como una tarea propiamente del Nacionalsocialismo, como perjudicial tanto para los intereses del Estado como enemiga de la idea de una gran unidad alemana.

Nosotros habíamos entendido y seguimos entendiendo al Nacionalsocialismo como un movimiento republicano, en el que existe tan poco espacio para la monarquía hereditaria como para cualquier otro privilegio que no descanse en el servicio a la Nación.

Nosotros habíamos visto y seguimos viendo en él el movimiento revolucionario que busca acabar con el Estado autoritario del mismo modo que con la democracia formal, y que ve su meta para el Estado es un modelo estatal orgánico de auténtica democracia germánica. Nosotros habíamos sentido por lo tanto que los intencionados claroscuros entre republicanismo y monarquismo de la dirección del partido son un lastre; y el excesivo culto por el autoritarismo fascista, como se manifiesta cada vez con mayor fuerza en los puestos oficiales del partido, verdaderamente como un peligro para el movimiento y un crimen contra la causa.

Nosotros hemos considerado y seguimos considerando al Nacionalsocialismo ante todo como el gran antídoto del capitalismo, el cual pone en práctica la idea del socialismo verdadero (aquel que está libre de la corrupción marxista) que lleva a la economía común de una Nación para el bien de esta Nación y rompe con el ese sistema de gobierno del dinero sobre el trabajo que impide el natural desarrollo de los pueblos y la verdadera creación de una economía popular.

Para nosotros el socialismo significa economía de necesidad en interés de la totalidad de los productores, participando en la posesión, dirección y ganancias de toda la economía de la Nación, es decir, la quiebra del monopolio de la propiedad del sistema capitalista actual, y ante todo la quiebra del monopolio de su poder de decisión, actualmente ligado a la propiedad.

Nosotros hemos notado por lo tanto, y en contra del espíritu original de los 25 puntos, que las formulaciones de nuestra voluntad socialista quedan cada vez más descoloridas desde la dirección; y las múltiples atenuaciones de las exigencias socialistas del programa (considérese por ejemplo el punto 17) (7*) que se han tomado, como una falta contra el espíritu y el programa del Nacionalsocialismo original, algo contra lo cual desde hace años hemos estado luchando con nuestra labor de enfatizar las exigencias socialistas del programa.

Nosotros habíamos sensibilizado y seguimos sensibilizando al Nacionalsocialismo conforme a su esencia, como el enemigo tanto de la burguesía capitalista como del marxismo internacional y vemos su tarea en la superación de ambos, a partir del hecho de que el sentimiento genuino socialista está unido en el marxismo a sus falsas enseñanzas del materialismo y del internacionalismo, y la burguesía, el de por sí correcto sentimiento nacionalista está unido a las falsas enseñanzas del racionalismo liberal y el capitalismo, y ambas fuerzas esenciales y acertadas (nacionalismo y socialismo) estarán condenadas a permanecer infructuosas en sus nefastas alianzas para la Nación y para la Historia.

Nosotros hemos visto y seguimos viendo por ello en nuestra lucha contra el Marxismo y contra el Capitalismo ninguna diferencia esencial, pues el liberalismo (y materialismo) existente en ambos es nuestro enemigo por igual.

Nosotros consideramos por tanto que las consignas de lucha de la actual dirección del NSDAP siempre en una sola dirección, “contra el marxismo”, como insuficientes y vemos en medida creciente que en todo ello existe un guiño de simpatía a la burguesía, que bajo las mismas consignas defiende sus intereses particulares y capitalistas, con los los que nosotros no hemos tenido ni tendremos nada en común.

Reforzados, subrayados y patentes se hicieron estos temores de naturaleza fundamental al comprobar las preocupaciones sobre las vías tácticas tomadas por la actual dirección del partido.

Desde siempre nos ha llenado de pesar y malestar, el que Adolf Hitler se haya explicado siempre tan a menudo en los círculos directores del empresariado y a los grandes capitalistas sobre los motivos y vías del NSDAP, pero (casi) nunca se ha tomado la molestia de hacer lo mismo con los círculos directores de los trabajadores y campesinos. Nosotros consideramos que el sentimiento resultante de ello, el de que el Nacionalsocialismo está más cerca de los primeros círculos que de los segundos, como un gran obstáculo. Tanto más cuando la franqueza nuestra voluntad socialista, debería excluir cualquier clase de entendimiento con esos círculos para los cuales la defensa de sus intereses capitalistas siempre será más importante que la realización de las metas nacionales y colectivas, sobretodo cuando esta realización tiene al Socialismo como premisa.

Por los mismos motivos hemos visto con creciente preocupación la estrecha relación de la dirección con Hugenberg y con el Partido Nacional del Pueblo Alemán (DNVP) (8*), y en parte también con los “Cascos de Acero” (Stahlhelm) (9*) y los llamados “patriotas alemanes”, porque todos estos hechos –aún cuando por el bien del pueblo pueden ser aceptables en sus fines tácticos–, parecen hechos expresamente para dar una equivocada imagen de nuestro movimiento.

Como punto fundamental del carácter revolucionario del Nacionalsocialismo ha estado siempre y sigue estando para nosotros el rechazo frontal de cualquier clase de política de compromiso y/o coalición, pues toda coalición sólo puede servir a los intereses del sistema (y orden) establecido, el sistema de la explotación capitalista, y por lo tanto contrario a la libertad nacional.

Se nos muestra según la esencia del Nacionalsocialismo y su tarea, la realización de la Revolución Alemana, que es simplemente imposible elevar la consigna de “entremos en el Estado”, al cual todavía no hace dos años, con los “Cascos de Acero”, hemos combatido con toda la crudeza de la voluntad revolucionaria.

La decisión de la dirección del partido de llevar a cabo una coalición con partidos burgueses en Thüringen, ha sacudido con fuerza nuestra fe en que nuestra idea de la esencia y tarea del Nacionalsocialismo, que tanto en el programa como en la actividad del partido fueron expresados hasta ahora, puede seguir siendo sostenida. Nuestros reproches fueron dejados sin respuesta por la dirección. En ello se ha situado el NSDAP en la misma situación que el SPD tras el 1918, cuando tomaron la decisión de ir junto a los enemigos de su voluntad político-económica, acabando con ello, forzosamente, traicionando sus metas originales. Con implacables consecuencias se ha realizado en el NSDAP la misma línea de traiciones a los fundamentos, como se muestra en su rebaja de los impuestos a particulares, el aumento de los alquileres y otras muchas políticas realizadas en Thüringen.(10*)

La objeción de que el peligro de la persecución estatal obligue a tamaños sacrificios de las convicciones, no es sólo inexacta, como la prohibición en Baviera y en Prusia muestran, sino socava ante todo el carácter y el valor del movimiento, pues con este argumento de la cobardía toda traición puede quedar cubierta. Mientras que para nosotros toda táctica debe encontrar su fin en los fundamentos, la dirección del partido ha abandonado cada vez más a menudo y en cada vez aspectos más decisivos las cuestiones esenciales del Nacionalsocialismo por consideraciones tácticas.

Junto con el aburguesamiento del partido ha venido también un creciente caciquismo que ha acabado por tomar formas estremecedoras. No sólo los llamados altos dirigentes de las SA sino, en creciente medida, también los funcionarios políticos del partido se han desarrollado según su actitud y su forma de vida de un modo, que se encuentra en contradicción tanto con las leyes internas de nuestro movimiento revolucionario como con las mínimas exigencias de un carácter honrado. La -entre tanto- casi general dependencia material directa o indirecta de los funcionarios del partido y su líder, ha dejado aparecer una tamaña atmósfera de indignidad, que hace virtualmente imposible la reivindicación de cualquier opinión independiente; asimismo ha llevado las cosas a un estado de corrupción material e ideal, que no se puede conseguir ayuda sin el apoyo de toda la organización (estructura) del partido. Los numerosos desacuerdos y problemas con los conflictos personales dentro del partido tienen aquí su más profunda y esencial causa.

Este desarrollo que nosotros aquí observamos con creciente preocupación, en los campos de fundamentos, tácticas y organización del partido, nos ha visto en cada hora del los últimos años como los primeros, profundos y severos enemigos y denunciantes. Los cinco años de “cartas nacionalsocialistas” (nationalsozialistischen Briefe), dan aquí un claro testimonio, tanto en la opinión personal como expresada, que hemos tomado sin consideración a las presiones y tentaciones llegadas desde arriba. En ninguna hora hemos tomado en cuenta la posibilidad de variar nuestros posicionamientos por motivos oportunistas, y en numerosas ocasiones nos hemos encontrado ante la cuestión de si debíamos tomar una manifestación pública de nuestra disconformidad con la dirección del partido en sus duros choques con la esencia del Nacionalsocialismo.

El que no hayamos hecho esto hasta el día de hoy se debe a que la dirección del partido no había renegado del programa de los 25 puntos abiertamente, y también porque confiábamos en que el espíritu revolucionario que vive sobretodo en los militantes base de las SA podría vencer sobre las actitudes de una dirección caciquista.

Esta esperanza se ha hecho vana con el último acto de voluntad de la dirección del partido.

A través de una carta de Adolf Hitler del 30 de Junio, el Gauleiter de Berlín fue forzado a llevar a cabo una limpieza sin contemplaciones de todos los “bolcheviques de salón” del partido.

Junto con esta exhortación fue decretada la exclusión de todos los militantes reconocidos o sospechosos de ser socialistas revolucionarios.

Con ello quedó pronunciado el definitivo divorcio del NSDAP con las metas y exigencias de una Revolución Alemana, y también de los puntos socialistas del programa original.

Como firmes, indoblegables, partidarios del Nacionalsocialismo, como ardientes luchadores de la Revolución Alemana, rechazamos este falseamiento del carácter revolucionario, de la Voluntad Socialista y de los fundamentos esenciales del Nacionalsocialismo y permaneceremos al margen del NSDAP convertido en ministerial, y siendo lo que siempre fuimos:

Nacionalsocialistas Revolucionarios

Grupo Otto Strasser

Notas

(1) Otto Johann Maximilian Strasser (10 de septiembre 1897 – 27 de agosto 1974). Político alemán del ala izquierda del Partido Nacionalsocialista Alemán de los Trabajadores (NSDAP). Mantenía posiciones más radicales que las de Hitler a quien consideraba demasiado moderado, en especial en su política económica complaciente con el capitalismo industrial. Propugnaba una revolución nacionalsocialista anticapitalista con factores socialistas estatizantes.

(2) Gregor Strasser (también Straßer) (31 de Mayo de 1892 – 30 de Junio 1934). Político alemán y Presidente del Partido Nacionalsocialista Alemán de los Trabajadores (NSDAP) de 1923 a 1925, con motivo del encarcelamiento de Hitler a resultas del fracaso del golpe de estado de la cervecería Burgerbräukeller, en noviembre de 1923. Fue asesinado en Berlín durante la llamada “Noche de los cuchillos largos”, donde se eliminó el ala Socialista del Partido, de la cual únicamente sobreviviría Joseph Goebbels, el cual tomó partido por Hitler.

(*3) Los “25 Puntos” constituyeron la base programática del Partido Nacional Socialista de los Trabajadores Alemanes (NSDAP). Sin embargo, una vez que Hitler fue nombrado Canciller del Reich, su gobierno se alejó en diversos aspectos de lo que establecían dichos principios. En parte, ello se debió a necesidades tácticas, y en parte, a la imposibilidad de llevar a la práctica cada uno de los puntos en la forma que originalmente habían sido planteados. No obstante, es evidente que los “25 Puntos” poseían una clara y contundente orientación Socialista, que en la praxis fue menoscabada o al menos soslayada en muchos aspectos por el Tercer Reich. En ello, hubo adicionalmente razones de Estado que debieron anteponerse una vez que Francia, Inglaterra y EE.UU. (y a la postre, 156 países), le declararon la guerra a Alemania.

(*4) Alemania sólo tomó decidido partido por el movimiento independentista Hindú de Subhas Chandra Bose y Sri Asit Krishna Mukherji (el esposo de Savitri Devi), una vez en guerra contra Inglaterra. El Movimiento Nacional hindú (salvo en las particularidades religiosas) fue muy semejante a los movimientos occidentales como el austríaco o alemán. Se constituyó a partir de los años veinte en torno a la Asociación de Voluntarios Nacionales (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, RSS), una asociación consagrada a “reforzar” y “fortalecer” a los hindúes frente a la minoría musulmana de aquel tiempo. A modo semejante del Movimiento Nacionalsocialista alemán de esa época, se estableció una red nacional de ramas locales que se reunían diariamente en sesiones de entrenamiento de artes marciales. Al entrenamiento paramilitar se le añadían los discursos ideológicos que no que eran la versión hindú del ideal nacionalsocialista del Kulturkampf (Lucha por la Cultura Nacional), que era coreado por fervorosos de militantes: “Hindu, hindi, hindustán” (“Un pueblo, una lengua, un país”). Había 25.000 ramas que agrupaban a más de dos y medio millones de seguidores.

(*5) El llamado “Pacto de Versalles” fueron condiciones ignominiosas y absolutamente injustas, impuestas por las potencias vencedoras de la Primera Guerra Mundial contra Alemania, por haber pedido el armisticio y dar término a la guerra.

(*6) Napoleón en su invasión de Alemania y su control de los Territorios del Rin creó pequeños estados, derechos y privilegios que sobrevivieron durante varios Siglos.

(7*) 17) “Exigimos la reforma de la propiedad rural para que sirva a nuestros intereses nacionales; la sanción de una ley ordenando la confiscación sin compensación de la tierra con propósitos comunales; la abolición del interés de los préstamos sobre tierras y la prohibición de especular con las mismas”. Este punto afectaba directamente los intereses de los “Junkers” (la “nobleza” hereditaria alemana), que poseía enormes fincas improductivas. En la práctica, una vez que Hitler llegó al poder este punto no se aplicó con la fuerza requerida contra los “Junkers”, aunque con otras medidas, sí se mejoró rápida y notablemente el nivel de vida de los campesinos.

(8*) Partido ultranacionalista y ultraconservador dirigido por un millonario.

(9*) Grupo paramilitar ultranacionalista generalmente formado por veteranos de la Primera Guerra Mundial y en parte ligado al DNVP.

#Otto Strasser#strasserismo#nacional socialismo#socialismo nacionalista#nacional bolchevismo#fascismo rojo

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Während alle Welt seit Jahren davor warnt, dass die CDU (sobald es dazu eine Gelegenheit gibt) gerne die Fehler ihrer Vorgängerparteien Zentrum und DNVP wiederholt und aus Machtgeilheit mit den Nazis koaliert, entwickelt die CDU jetzt die geniale Idee, das ebenfalls machtgeile BSW solle zuerst mit den Nazis koalieren und man selbst wolle dann kurzfristig die Macht von diesen übernehmen (weil sie es ja sowieso nicht auf die Reihe brächten).

Die NZZ, die ja von ihren AbonnentInnen am rechten Tand lebt, schreibt das auch ganz offen:

Der Cicero, bei dem auf Befragen vermutlich niemand Demokratie * richtig definieren könnte, meint:

Selbsternannt ist ein Schlüsselwort, da kommt es auf die Anführungszeichen bei demokratisch gar nicht mehr an.

(*) in der heute noch gültigen Definition

0 notes

Photo

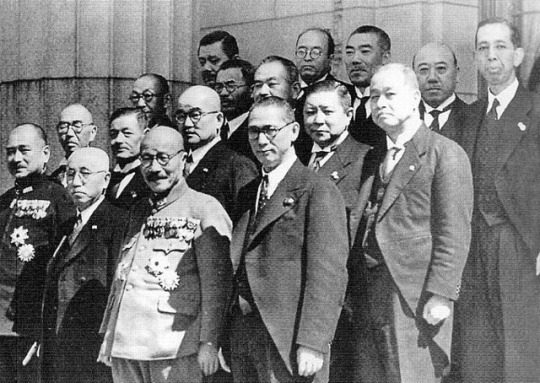

Des saluts nazis de la foule pour la grande marche de l'opposition nationale (Front de Harzburg) menée par Hugenberg et Hitler à Bad Harzburg – Allemagne – 11 octobre 1931

Photographe : Georg Pahl

©Bundesarchiv - Bild 102-12405

Le front de Harzburg était une brève alliance politique de droite formée en 1931 sous la république de Weimar afin d'unifier l'opposition au gouvernement du chancelier Heinrich Brüning. Cette coalition comprenait notamment le Parti national du peuple allemand (DNVP), de l'homme d'affaires millionnaire Alfred Hugenberg, le Parti national-socialiste des travailleurs allemands (NSDAP) d'Adolf Hitler, les paramilitaires du Stahlhelm, Bund der Frontsoldaten, la Ligue agricole (Landbund) ainsi que la ligue pangermaniste (Alldeutscher Verband).

L'alliance est formée le 11 octobre 1931 à l'occasion d'une convention de représentants des partis d'opposition dans la ville de Bad Harzburg. Elle sera de courte durée en raison de l'intransigeance du parti nazi et des différences idéologiques entre les partis de droite.

#Avant-guerre#Pre-war#République de Weimar#Weimar Republic#Front de Harzburg#Harzburg Front#Droite allemande#German right politics#Nazisme#Nazism#Bad Harzburg#Allemagne#Germany#11/10/1931#10/1931#1931

8 notes

·

View notes