#dikenga

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Nós.

Nankin sobre tela.

15cm x 15cm.

#cosmograma bakongo#spiritual knot#bantu#dikenga#bantu-kongo#kongo#fu-kiau#azul#blue#black#preto#nankin

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

retrato da mestra makota valdina

retrato da mestra makota valdina …no que makota valdina disse, ao tocar o chão: kavungo é tudo, kavungo é a terra, nós somos a terra, nós somos essa química que é a terra, essa química que é remédio, química que é alimento, química que todo terreno precisa de ter – a gente precisa viver.

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

African American Baptism in De Leon Springs, FL. Circa 1915. Image via Florida Memory.

Seashells in Jomo

In West and West-Central African cosmology water is seen as a bridge between de material and spiritual world. In Jomo, the Kongo dikenga is a recurrent motif that is remembered and respected. This symbol illustrates the concept of water dividing the spiritual world and the material world; as the kalunga line divides the ancestral realm and the realm of creation.

Offerings:

Seashells were often given to ancestors as offerings. In Florida —and beyond— they were placed on the top of loved one’s graves. For one, to maintain a connection with them as they transitioned to another realm. Furthermore, to ensure those who passed on remained on the other side.

Protection/Talismans:

Consequently seashells were also worn as a means of protection against enemies. Ancestors and/or the deities they made covenants with, protected those who charmed seashells with that intent.

Candles:

Seashells could also be used to hold candlewax. These candles could be burned as offerings for the ancestors and/or specific deities.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Palo Mayombe: Kongo-derived Afro-Cuban Spirituality — Lawrence Talks!

“This complexity described in the Bantu-Kongo word for person, muntu is a ‘set of concrete social relationships ... a system of systems; the pattern of patterns in being.’ The person is contextualized as a system participating in other systems, a pattern, a ripple that is sourced and from a source.”

— Kimbwandende Kia Bunseki Fu-Kiau, African Cosmology 42

Dr. Kimbwandende Kia Bunseki Fu-Kiau, a Congolese native and scholar of African religion, captures the essence of Kongo cosmology with this quote, and from this cosmological structure lies the roots of the African diasporic religion Palo Mayombe. Just as a person is “a system of systems; the pattern of patterns in being,” ancestral reverence and inclusion positions humans through a multitude of bodies that have come before them. Ancestral veneration is at the core of many African Diasporic spiritualities. Many individuals who grew up in traditional Christian churches are leaving beliefs of Christendom in search for traditional religions that help them connect with their ancestors. Religious and spiritual systems like Ifa, Santeria, Vodou and Conjure have been popularized, sometimes in negative ways by the media, but for the most part these are the spiritualities that people turn to first in their exploration of African traditional religions (ATR). And what is known of Palo Mayombe by the general public is not a large amount of information by any chance. A Google search locates some articles which picture Palo as the “dark side” of Santeria, which is far from the truth. However, to understand Palo as a distinct spiritual system outside of other African diasporic religion, one must understand its BaKongo cosmological foundations.

History of ancient Kongo cosmology

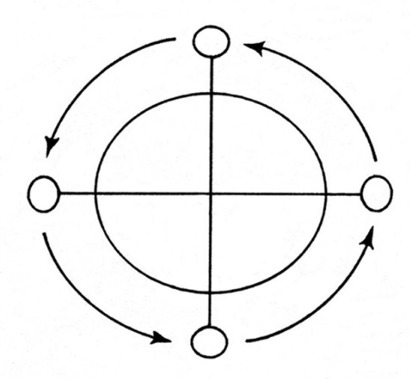

Figure 1: Kongo cosmogram (dikenga)

Fortunately, there is a symbol that captures the essence of Kongo cosmology. The Kongo cosmogram is a cosmological symbol that represents the very patterning of the life process. This symbol is a pre-colonial representation of the cosmogram, as it was conceptualized before European colonization in 1482[1]. It is called the dikenga in the KiKongo language, literally meaning “the turning;” it stands for the cycling of the sun around four cardinal points: dawn, noon, sunset, and midnight when the sun is shining in the world of the dead. Composed of a cross, a circle, and usually arrows, this symbol was found in Kongo material culture well before the contact of colonial Christianity and its cross motif. Anthropologist Robert Farris Thompson, a scholar of Kongo art and religion, says that the “dikenga represents the ultimate graphic design, containing key concepts of Bakongo religious belief, oral history, cosmogony, and philosophy, and depicting in miniature the Bakongo conceptual world and universe” (Thompson 110). The key principle of the dikenga is that nothing ever survives “intact” because nothing ever survives in a fixed form. It is this spiral that is the basic element of Kongo spirituality.

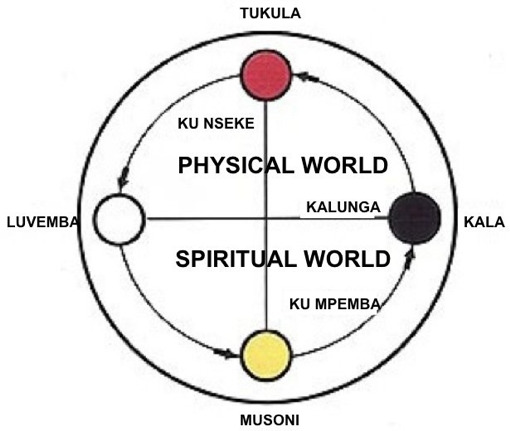

Figure 2: Dikenga

In his seminal piece on Kongo cosmology entitled African Cosmology of the Bantu-Kongo: Principles of Life & Living, Dr. Fu-Kiau explains the motion of the dikenga as the process of ancestralization, of dying and being reborn as an ancestor, through the heating and cooling of existence. This explanation of death and ancestralization is at the core of Palo Mayombe.

Origins of Palo Mayombe

Palo Mayombe is a Kongo derived religion from the Bakongo Diaspora. This religion was transported to the Caribbean during the Spanish slave trade and sprouted in Cuba mostly and in some places in Puerto Rico in the 1500. As the enslaved were forced out of their homelands, their beliefs went with them. Spanish colonialists in Cuba initiated a strategy in the sixteenth century to create mutual aid societies, called cabildos or cofradías, which served to cluster Afro-Cubans into different ethnic categories. This was a strategy of “divide and rule” designed to foster social differences across groups within the enslaved population so that they would not find a unifying focus through which to rebel against the colonial government. In contrast to the extensive blending of diverse African cultures that would be seen in Haiti and Brazil, Cuban cabildos contributed to rich continuations of Yoruba culture in the development of Santería and to largely separate developments of BaKongo beliefs in Palo Mayombe (Fennel). Elements of Catholic beliefs were incorporated into both Santería and Palo Mayombe due to the imposition of the Spanish colonial regime and the cabildo system.

Figure 3 Palo Mayombe Ceremony

Palo Mayombe is very nature-based. Although most African Diasporic religions base rituals and practices in nature, palo (meaning “stick” or “segment of wood” in Spanish) solely depends on the material elements of nature to access the spiritual realm. In Cuba, the Kongo ancestor spirits are considered fierce, rebellious, and independent; they are on the “hot” scale of natural forces. Just as the importance of ancestralization mentioned above, the ancestors are present and inclusive in the practitioner’s life. Nzambi Mpungo is the greatest force in which paleros or paleras (Palo practitioners) call God. Nzambi Mpungo is literally the first ancestor, the initial iteration which all human life flows. Nzambi was viewed as having created the universe, people, spirits, transformative death, and the power of minkisi (ritualized, material objects). The Godhead was thus viewed as being removed from mortal concerns, and supplications were made instead to the ancestor spirits or the intermediary spirits created by Nzambi. Below Nzambi are the mpungus (elemental forces), the ancestors, and the spirits of natural forces (Bettelheim). Each mpungu is similar to an orisha from Yoruba culture due to shared African derived origins, but the two are not the same entity by any means. The mpungu are Afro-Cuban spirits, specific to their diasporic groundings and to the lands of the Diaspora. However, due to their origin

The material tools of Palo Mayombe

Cigars are used to enter into a trance-like state in order to more easily connect with spirits. Special machetes and chains are also used in spirit pots. Candles and rum are essential elements for any Palo ritual. The nganga is used to describe an iron cauldron filled with dirt and specialized sticks; this aids the palero/a in communication with the spirit. In Central America, Cuba and the Caribbean, this cauldron is called a Nganga-Prenda because the culture of modern day and the influence of Latin American's spiritualism in Palo Mayombe.

Figure 4: Prenda de Lucero

The Muertos are important entities in the Palo religion. The house of the dead is where the Palo spirits and the ancestors reside. As illustrated through the Kongo cosmogram above, Palo cosmology does not believe in death, but a continual cycle through various forms. It is the process of ancestralization that makes communication with the spirits of the dead accessible. In the Kongo tradition, ancestors, who have access to invisible forces, have the duty to protect the living. In exchange, the ancestor’s descendants have the obligation to take care of the ancestor’s memory and to venerate their earthly representation. This is why bones are another central tool in Palo. After a person has passed, the bones remain, and the bones carries the essence of a soul long after a person is gone. Bones are thus a sacred item in Palo Mayombe and are usually incorporated in Palo rituals. Usually an ancestor altar is an essential piece in the house of a palero/a, along with offerings of food, drink, and special itemize to venerate their ancestors.

Like many ATR’s and magical system, initiation of some kind is needed in order to practice. Guidance from the elders of the religion is highly encouraged, especially since the ways of the spiritual system is nothing like physical realms.

Palo Mayombe and Other Religious Connections

The influence of Palo Mayombe can be found in Central America, Brazil, and Mexico and in the United States. There are different sects of Palo (Palo Monte, Christian-based Palo, Jewish-based Palo) that come from different lineages and distinct engagements with the cultural environment around the practice. There is another Kongo-derived religion in Brazil is Quimbanda, which is a mixture of traditional Kongo, indigenous in India and Latin American spiritualism. Palo Mayombe is the engagement of Kongo influence in the Caribbean and the wider Diaspora. It has its own priesthood and set of rules and regulations. Rules and regulations will vary according to the Palo Mayombe house to which an individual has been initiated into.

Some people who practice Palo might mix other African-derived systems, like Ifa, Vodou, or Santeria, but Palo is a religion in its own right. For example, Yemoja, the orisha of the ocean and motherhood, may be seen as the same energy as Madre de Agua, the mpungo of the ocean and of motherhood. Although these spirits may have similar functions within the religions, they are two separate entites from particular cultural origins and with specific needs. It is quite common for spiritual seekers to be initiated in multiple religions, so it is of great importance to make sure each path is approached. Although there are other religious elements in Palo, it is all included in the practice and not separated within the religion. When Portuguese missionaries brought the message of Christianity to the Kongo/Bantu, the natives embraced it…while continuing their own native practices (Jason R. Young, Rituals of Resistance). So, this pattern of centripetal inclusion is also present in Palo Mayombe. As Iya TeeDee Oshún, a priestess of African diasporic religions, commented in a recent Facebook post:

“Palo is a beautiful road for those of us that it is for. It's also not just some shit you get done real quick before you ‘elevate’ because that's what Iya's spirit guide said to her in the shower. (Not making that up at all.) It's definitely not Iya nor Baba's "witchcraft pot" in the closet or behind the washing machine or above the grease stain in the garage. It's rarely what I hear when people talk to me in Yorabalese” (2019).

Iya’s mention of “Yorbalese” speaks to a common trend of people in the Diaspora making all of African-derived religions about orisha Ifa/Nigeria, but Palo is of the BaKongo Diaspora. The only system close in origin and practice to Palo is African American Hoodoo, which uses similar elements of the heating and cooling of herbs in spiritual work.

Conclusion

When one decides to take a step into the spirituality of Palo Mayombe, the journey really is a deep engagement with their ancestors and with the raw elemental forces of nature. It is a spiritual awareness that provides protection for the community and the self. The ancestors are the root of one’s existence; the root is the culminating point from which all life springs. This Afrocentric view of cosmology in which Palo Mayombe is grounded, deals with the consciousnesses of nature and of ancestry. Anyone who claims Palo Mayombe as a “dark” or unorthodox religion does not understand the Kongo origins of which Palo operates.

[1] The Kongo cosmogram is a pre-Christian symbol, but due to the iconography of the Christian cross, many people overlap their meanings

#Palo Mayombe Kongo-derived Afro-Cuban Spirituality#Palo#ATR#Congo#African Cosmology#Ancestry#African Religions#IFA#Palo Monte#Kongo

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

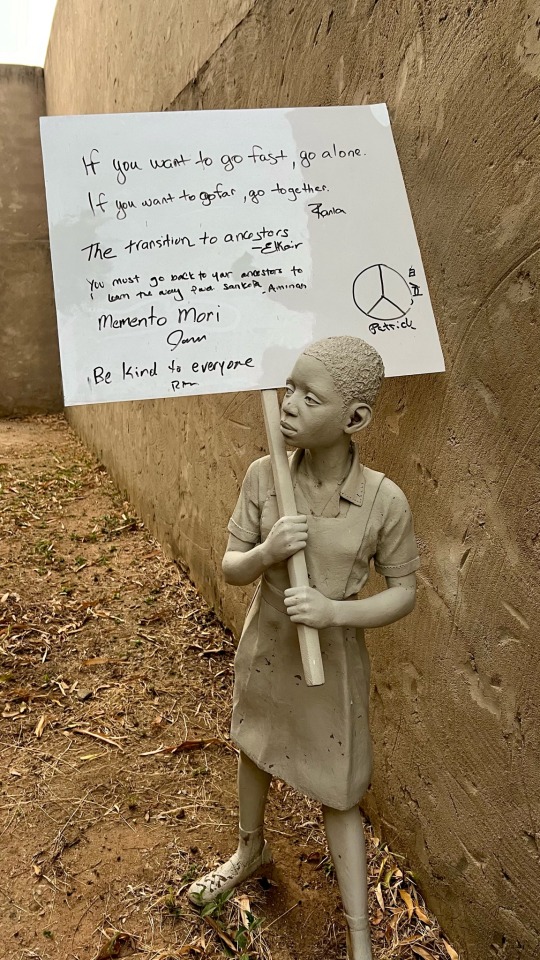

I took a captivating trip to the Nkyinkyim museum in Ada, just a 2-hour drive from Accra. The tour, priced at 100gh per person, was hosted by a griot, a very enthusiastic storyteller whose energy transformed the tour into an exciting journey.

The tour commenced with artifacts at the entrance, revealing the wonders of Sudano-Sahelian architecture dating back to 2500BC. The structures, crafted from organic materials like red mud, clay, and bamboo, showcased the remarkable skill and eco-friendly ingenuity of our ancestors. The community engagement in the construction process mirrored their deep connection with nature.

Intrigued by the symbolism etched on the walls, I marveled at the adinkra symbols, patterns, and shapes that were not only aesthetically pleasing, but held profound meanings. The journey unraveled the cultural ties across Africa, even discovering that Sudan boasts more ancient pyramids than Egypt.

The griot animatedly shared the wisdom behind the symbols—footprints symbolizing our shared humanity, the spider embodying intelligence, the tortoise exemplifying adaptability, and the snail conveying the concept of leaving a lasting legacy. The ant emerged as a powerful symbol of collaboration and community, echoed by the Nkyinkyim symbol representing resilience inspired by nature.

There was also a structure that was described as a life sized Lukasa memory board which challenged the notion that African traditions were solely oral. It became clear that our history was archived through symbols, writings, and memory boards, providing a unique form of communication despite the challenges faced during colonial times.

The journey progressed to a wall adorned with discs inspired by the Dikenga cross, a core symbol of Bakongo religion of the Kongo people symbolizing the cardinal points of human existence and the cycle of life.

The emotional apex was the veneration site—a symbolic memorial to enslaved ancestors. Sculptures conveyed tales of capture, from shock and determination to hidden identities and interrupted hair appointments. The vivid facial expressions on the sculptures offered a poignant glimpse into their harrowing experiences and the traumatizing ways through which they were captured.

There was a wall featuring diverse writings from across the continent, such as Nsibidi and vèvè, underscoring the richness of African history. The trip left me inspired to delve deeper into our heritage, resonating with the concept of Sankofa: going back to our ancestors' ways to chart a purposeful future.

The final chapter featured paintings showcasing accomplished individuals of African descent, a testament to resilience and exceptional lives emerging from the shadows of history. This transformative experience reinforced the belief that understanding our roots definitely shapes the trajectory of our future endeavors.

11 notes

·

View notes

Link

El Dikenga es para los kongo la representación de un mapa del cosmos. Un símbolo usado durante siglos, del que relatan:

“Nueve fueron los meses necesarios para crear la gente kongo, para lo que se precisaron nueve bastones, mvwala o nti amfumu, pertenecientes a los nueve clanes originales con los que instaurar las reglas sociales para un buen gobierno.

Tales bastones fueron vistos como instrumentos de poder, simbolizando el papel crucial del jefe en la comunicación entre el mundo de los vivos y el de los muertos. Los utilizados, también ilustran los puntos de vista de las personas kongo sobre el poder y resaltan la importancia de las mujeres y la fertilidad.

Utilizados exclusivamente por los jefes de clan, representan a una mujer como la fundadora o madre ancestral de dicho clan; un niño en su regazo o en su pecho representa al clan como una entidad unificada.

Los patrones geométricos en el eje del bastón son más que decoraciones: contienen mensajes codificados sobre las relaciones entre los vivos y los muertos. Las representaciones visuales del dikenga también tienen un poder espiritual innato. Por ejemplo, una persona puede pararse en el punto de cruce de un dikenga dibujado en el suelo para pronunciar un juramento”.

0 notes

Text

among other things*....

More interpretations of the Cross that have been passed down from the Ancestors, are through the Kongo Cross, the Dikenga, and the Andean Cross, the Chakana.

As the Dikenga, it represents the beliefs and traditional knowledge passed onto us by our west african ancestors. It represents, for our family, the belief in the Great Spirit (Nzambi Mpungu) and all the Spirits of traditional kongo religion (like the enkisi), including our ties to the Ancestors and the importance of Ancestral Veneration. The cross itself represents the four stages that all life goes through (seed, sprout, maturity; and death), and the Order given unto the physical-material realms and the spiritual-ancestral realms by Kalunga, the force that connects and moves all things. Kalunga is, at the same time, a title given to some Spirits, aswell as a term used to refer to liminal or threshold spaces, like crossroads, cemeteries, and the Ocean. It is also a symbolic representation of the cycles of Death & Rebirth in our lineage, and of the belief that we reincarnate in our descendants ("return to ourselves").

The Chakana, another symbol that represents the cosmology of our Ancestors but this time, of the andean peoples. Similar to the Dikenga, it represents the four elements (Allpa, Wayra, Nina and Yaku) and cycles of life (being a representation of our regional stellar-lunar-solar calendar). It explains the different forces of Nature that we live with and are guided by through their manifestations in the Stars, the Lunar and Solar cycles, aswell as in the Land itself. Very similarly to the Dikenga, it also states four stages to all Life (Sowing, Sprouting, Maturity and Harvest) and describes the Creator God as the Great Arranger, who's spark of life put order to all things past, present and future.

The cross is a seemingly simple symbol that represents many things for us. But in short, it represents the beliefs that our African and Indigenous Ancestors shared with each other and the Union of these two branches of Ancestry into one tradition, as it reached us.

The Mysteries of The Rose

"The rose reveals the portal that opens into the center of all things. This center is symbolized by the rose blossom." — Raven Grimassi in Grimoire of the Thorn-Blooded Witch.

The system I use in my personal practice is based not only on the dual concept of Blood and Water, but also on the pursuit of what I now shall call The Mysteries of The Rose. This system is informed by hereditary practices, ancestral veneration and the aid and perspectives of other practitioners.

One of the books that, much to my surprise, manages to match some of the beliefs that sum up this system, is Grimoire of the Thorn-Blooded Witch, where the author describes 'Five levels' of training in witchcraft, and acquiring mastery over each as 'gathering a thorn'. Personally, I view it slightly different. What I see are six, not five, skills that a successful practitioner should hone, and I see it less like levels (complete and perfect mastery being unachievable) and more like Doors that one crosses (into an ongoing process).

Then, the Doors to the Mysteries are sixfold, as six petals surrounding the center, and these doors are: herbalism and greencraft, magic, and stonecraft, mediumship, mysticism, and seership. Five of these match exactly the ones described by Grimassi, with the sixth being the addition of stonecraft. A skill, and a Door, to Spirits that are often misrepresented, or underrepresented, in witchcraft, if not forgotten and left aside completely.

These Doors are also divided in two sets of Threes. The First Set involves daily practices that define the present, tangible life of the witch, the Second Set involve Ties with the Other, with the Intangible, Spiritual world. Finally, a cross over the rose blossom represents, among other things, the Intersectedness of these skills. How none of them must be practiced in isolation, and instead, must be studied side by side, with each one supporting the others, to allow the practitioner a holistic view that connects past, present and future, and all manners of being: animal, vegetal and mineral.

The Crossed Rose then, symbolizes The Blood Of The Witch, in it's capacity to carry wisdom over generations, aswell as across different states of being. This is the Center of my practice.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Check out my article on Reclaiming + Reconnecting to Black African Indigeneity we are the world’s first and thus oldest Indigenous peoples. Anti-Blackness attempts to erase us/cause Identity crises in Black people but I am determined fo disrupt this 🙌🏾

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

If anyone has resources on learning Kikongo, please let me know.

#hoodoo#conjure#realhoodoo#african spirituality#rootwork#ancestors#adr#african american spirituality#atr#keepconjureblack#kongo#Kikongo#dikenga

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dois mundos.

Nankin, acrílica e guache sobre tela.

15cm x 20cm.

#bakongo#bantu-kongo#bakongo cosmology#dikenga dya kongo#cosmograma bakongo#cultura negra#painting#nankin#fu-kiau

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

cantos de kalunga. as africanidades e a espiritualidade mineira

A Escola Djalo Nomad convida você e sua família pra participar da mesa de conversa “As africanidades e a espiritualidade mineira”, onde vamos refletir sobre a importância da presença africana e suas aportações nas múltiplas dimensões da espiritualidade e religiosidade mineira, especialmente na região de Mariana e Ouro Preto. Como convidades mais que especiais, Ana Paixão, Arlindo Diório e…

View On WordPress

#africanidades e diáspora#afromineiro#ana paixão#arlindo diório#cantos de kalunga#dikenga#solange palazzi#tolerância religiosa

0 notes

Text

LifeSparks006: When Nature Speaks. Today, seing still.

#being still.#storyaid#qtellerr#maat#QDSA#GRT#lifesparks#storytelling#dikenga#kingscollegelondon#energy#meditation#beinghuman#sentience#natureteaches

0 notes

Text

February 2023 on The Hoodoo's Calendar asks us to visualize the power & depth of our roots - as we celebrate BLACK HISTORY MONTH✊🏾🖤

Our blood soaks the soil of the earth. It feeds our roots that burrow deep into her depths. The fillamentous stretch of each branch below is a mirror to those that stand tall & spread wide above.

As above, so below - the Kalunga line of the Dikenga. We are a direct reflection of those who came before us. We incarnate here on behalf of our lineages to serve a greater purpose(s). The progress of our journey here reflects the elevation of our lineages there.

A tree without roots cannot stand. An image cast without a mirror has no reflection. Without knowledge of self, we are without purpose. Without purpose, we are absent direction. In the absence of direction, we are lost. Lost, we are void of progress & fulfillment.

🌟 FINAL copies of The2023 Hoodoo's Calendar are available for purchase (once sold out, that's it)! Subscribe to the official e-newsletter for the latest updates & exclusive content access.

https://thehoodoocalendar.square.site 🌟

#hoodoo#hoodoos#atrs#juju#atr#conjure#rootwork#rootworkers#conjurers#black girl magic#hoodoo tradition#hoodoo heritage#for the culture#hoodoo culture#February 2023#black spirituality#roots

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Central African influence

The Bantu-Kongo origins in Hoodoo practice are evident. According to academic research, about 40 percent of Africans shipped to the United States during the slave trade came from Central Africa's Kongo region. Emory University created an online database that shows the voyages of the trans-atlantic slave trade. This database shows many slave ships primarily leaving Central Africa.

Ancient Kongolese spiritual beliefs and practices are present in Hoodoo such as the Kongo cosmogram. The basic form of the Kongo cosmogram is a simple cross (+) with one line. The Kongo cosmogram symbolizes the rising of the sun in the east and the setting of the sun in the west, and represents cosmic energies. The horizontal line in the Kongo cosmogram represents the boundary between the physical world (realm of the living) and the spiritual world (realm of the ancestors). The vertical line of the cosmogram is the path of spiritual power from God at the top traveling to the realm of the dead below where the ancestors reside.

The cosmogram, or dikenga, however, is not a unitary symbol like a Christian cross or a national flag.The physical world resides at the top of cosmogram and the spiritual (ancestral) world resides at the bottom of the cosmogram. At the horizonal line is a watery divide that separates the two worlds from the physical and spiritual, and thus the "element" of water has a role in African American spirituality. The Kongo cosmogram cross symbol has a physical form in Hoodoo called the crossroads where Hoodoo rituals are performed to communicate with spirits, and to leave ritual remains to remove a curse. The Kongo cosmogram is also called the Bakongo cosmogram and the "Yowa" cross. The crossroads is spiritual (a supernatural crossroads) that symbolizes communication between the worlds of the living and the world of the ancestors that is divided at the horizontal line. Counterclockwise sacred circle dances in Hoodoo are performed to communicate with ancestral spirits using the sign of the Yowa cross.

Communication with the ancestors is a traditional practice in Hoodoo that was brought to the United States during the slave trade originating among Bantu-Kongo people.

In Savannah, Georgia in a historic African American church called the First African Baptist Church, the Kongo cosmogram symbol was found in the basement of the church. African Americans punctured holes in the basement floor of the church to make a diamond shaped Kongo cosmogram for prayer and meditation. The church was also a stop on the Underground Railroad. The holes in the floor provided breathable air for escaped slaves hiding in the basement of the church. In an African American church in the Eastern Shore of Virginia, Kongo cosmograms were designed into the window frames of the church. The church was built facing an axis of an east-west direction so the sun rises directly over the church steeple in the east. The burial grounds of the church also show continued African American burial practices of placing mirrorlike objects on top of graves. The Kongo cosmogram sun cycle also influenced how African Americans in Georgia prayed. It was recorded that some African Americans in Georgia prayed at the rising and setting of the sun.

On another plantation in Maryland archeologists unearthed artifacts that showed a blend of Central African and Christian spiritual practices among enslaved people. This was Ezekial's Wheel in the bible that blended with the Central African Kongo cosmogram. The Kongo cosmogram is a cross (+) sometimes enclosed in a circle that resembles the Christian cross. This may explain the connection enslaved Black Americans had with the Christian symbol the cross as it resembled their African symbol. The cosmogram represents the universe and how human souls travel in the spiritual realm after death entering into the ancestral realm and reincarnating back into the family. Also, the Kongo cosmogram is evident in hoodoo practice among African Americans. Archeologists unearthed on a former slave plantation in South Carolina clay bowls made by enslaved Africans that had the Kongo cosmogram engraved onto the clay bowls. These clay bowls were used by African Americans for ritual purposes. The Kongo cosmogram symbolizes the birth, life, death and rebirth cycle of the human soul,and harmony with the universe.

The Ring shout in Hoodoo has its origins from the Kongo region with the Kongo cosmogram (Yowa Cross) and ring shouters dance in a counterclockwise direction that follows the pattern of the rising of the sun in the east and the setting of the sun in the west, and the ring shout follows the cyclical nature of life represented in the Kongo cosmogram of birth, life, death, and rebirth. Through counterclockwise circle dancing, ring shouters built up spiritual energy that resulted in the communication with ancestral spirits, and led to spirit possession. Enslaved African Americans performed the counterclockwise circle dance until someone was pulled into the center of the ring by the spiritual vortex at the center. The spiritual vortex at the center of the ring shout was a sacred spiritual realm. The center of the ring shout is where the ancestors and the Holy Spirit reside at the center. The ring shout tradition continues in Georgia with the McIntosh County Shouters. At Cathead Creek in Georgia, archeologists found artifacts made by enslaved African Americans that linked to spiritual practices in West-Central Africa. Enslaved African Americans and their descendants after emancipation house spirits inside reflective materials and used reflective materials to transport the recently deceased to the spiritual realm. Broken glass on tombs reflects the other world. It is believed reflective materials are portals to the spirit world.

In 1998, in a historic house in Annapolis, Maryland called the Brice House archeologists unearthed Hoodoo artifacts inside the house that linked to Central Africa's Kongo people. These artifacts are the continued practice of the Kongo's Minkisi and Nkisi culture in the United States brought over by enslaved Africans. For example, archeologists found artifacts used by enslaved African Americans to control spirits by housing spirits inside caches or bundles called Nkisi. These spirits inside objects were placed in secret locations to protect an area or bring harm to slaveholders. The artifacts uncovered at the James Brice House were Kongo cosmogram engravings drawn as crossroads (an X) inside the house. This was done to ward a place from a harsh slaveholder.

Nkisi bundles were found in other plantations in Virginia and Maryland. For example, Nkisi bundles were found for the purpose of healing or misfortune. Archeologists found objects believed by the enslaved African American population in Virginia and Maryland to have spiritual power, such as coins, crystals, roots, fingernail clippings, crab claws, beads, iron, bones, and other items that were assembled together inside a bundle to conjure a specific result for either protection or healing. These items were hidden inside enslaved peoples dwellings. These practices were concealed from slaveholders

#african#hoodoo#maryland#virginia#black history month#slaveholders#nkisi#kongo#cosmogram#afrakan#kemetic dreams#brownskin#afrakans#africans#african culture#afrakan spirituality#afrakan woman#savannah#georgia#savannah ga

200 notes

·

View notes

Text

futuristic holographic AI is a translucent glowing ghost. It is smiling upon its African American Ancestors looking at it. Background is a Kongo Dikenga influenced sacred geometric background. character concept art. art by Yusuke Murata. super glossy, glowing eyes and skin, Ray Traced, Ray Tracing, Tone Mapping, hyper-realistic, intricate, highly detailed, holographic, ultra sharp, vibrant colours --v 4

Nazara13

midjourney

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hoodoo Heritage Month: Conjuring, Culture, And Community

Source: IMAGE COURTESY OF MADAME OMI KONGO / PINTEREST

October is Hoodoo Heritage Month! Hoodoo is an umbrella term to describe the conjuring, culture, and community of Black Americans. It’s often regarded as a Black spiritual tradition that focuses on nature and ancestral reverence.

Hoodoo Heritage Month started in 2019 when Hoodoo and Pre-Elder Mama Rueshared a post about African American spirituality on Facebook and proposed a Hoodoo Heritage Day. The Walking the Dikenga Collective extended the idea from a day to a month, and Hoodoo Heritage Month was born. What was originally a weekend event filled with teaching and classes is now a social media and community celebration of all things Hoodoo.

Hess Love, Hoodoo Historian, Archivist, and Environmental Activist says that October is the perfect month because it correlates with the thinning of the veil between our physical world and the spiritual realm. For them, Hoodoo Heritage Month is “a wonderful month of celebration, exploration, history lessons, and connections and also people learning about how pragmatic this tradition is and dynamic it is at the same time.”

If you search the hashtag #HoodooHeritageMonth on social media, you’re sure to find many resources seeking to educate Black Americans about Hoodoo. The Walking the Dikenga Collective created certain dates to commemorate the great Hoodoo ancestors:

October 2: Nat Turner Day

October 6: Fannie Lou Hamer Day

October 21: Day of our Fathers

October 23: Day of our Children

October 25: Day of our Mothers

Third Thursday: John the Conqueror Day

October 31: Crossroads Day

Mama Rue spoke with MADAMENOIRE on the importance of sharing information about these ancestors. For John the Conqueror Day, she says,

“White-washed Hoodoo doesn’t even acknowledge John the Conqueror that much because he’s been white-washed to be the type of Spirit that helps men with their virility, help men get women, help gamblers get lucky, and he’s so much more than that, and you get to learn the truth about this Spirit and what this Spirit means to us and our people.”

This white-washing has extended to other Hoodoo spirits such as the Spirit of the Crossroads. While regionally and culturally the Spirit is treated differently, mainstream media has equated this spirit to a demonic force that grants wishes in exchange for your soul, such as with Robert Johnson. The Spirit of the Crossroads is actually a spirit that operates at the crossroads between the physical and spiritual realms.

Thankfully, Mama Rue, Hess Love, and other Hoodoos are sharing the truth of our tradition with other Black folks on social media.

Around the creation of Hoodoo Heritage Month, Mama Rue felt called by her Spirits to speak out against the culture of half-truths, misconceptions, and cultural appropriation surrounding Hoodoo. She says, “Hoodoo is often seen as the bastard stepchild of the ATRs (African Traditional Religions). Folks from that lens tend to say, ‘Hoodoo is just tricks. There is no spirit involved and there’s no initiation.’”

Hoodoo Heritage Month seeks to set the record straight.

Hoodoo, as a tradition, has waxed and waned in visibility in the United States. Mama Rue explains,

“During slavery, our ancestors were not allowed to express any sort of African traditional practices. There were repercussions. Our ancestors being so clever and being the geniuses that they were figured, ‘We can still do our work and work this crossroads because we didn’t make that and they can’t punish us for walking around it, and honoring our ancestors and honoring the spirits that our ancestors revere.’ We were able to sort of sneak our practice in without anyone watching or being truly aware of what was going on.”

These practices were hidden in various parts of Black culture, including the Black church, but in recent years Black folks have been turning away from the Black church.

Mama Rue shares,

“A lot of us were leaving our churches and were talking about abuse in church. Different types: financial abuse, sexual abuse, emotional and psychological abuse.”

She claims this mass exodus left many people feeling like spiritual orphans because they had a strong spiritual need with no way to channel it outside of the church structure.

While our ancestors had to hide their African spirituality, we’ve seen a shift in the past decade. Black celebrities such as Beyoncé and Solange, writers such as Tracy Deonn and Jesmyn Ward and even the Nap Bishop herself, Tricia Hersey openly celebrate Black spirituality in their work. This artistic movement coupled with the mass exodus from the church has led to a widespread reclamation of Hoodoo.

Both Mama Rue and Hess Love say that Hoodoo, and by extension, Hoodoo Heritage Month, is for descendants of enslaved Africans in the United States and descendants of free Black people during the time of enslavement. While many Black people have stepped away from the church, Mama Rue reminds us that church-going Black folks remain one of the biggest preservers of Hoodoo and are therefore always welcomed in the tradition.

Hess goes further and tells MN,

“It’s for Black folks who live and love and want to be part of an intentional Black community and also not running away from themselves. There are some Black people who have no desire and no intention of being in community with Black people in a particular way. It’s for Black people who love other Black people. It’s for Black folks who love their ancestors. It’s for Black people who may be displaced in their community but have a type of allyship with the land and the air.”

Hoodoo Heritage Month is now a celebration of many Black people returning to the tradition of our ancestors. It’s a time for Black people to honor our ancestors, community, the environment, and ourselves.

Mama Rue says,

“It’s a time for us to get in touch with the things that our ancestors brought to this land that were broken up, fragmented, lied on, etc. It’s our way to move toward complete liberation. It’s our way of righting certain wrongs especially in the practice of ancestor reverence.”

Ancestor reverence operates on the belief that our ancestors continue to exist long after they die. As spirits, we can honor them through learning about and sharing their stories, building an altar, giving them offerings, or simply talking with them. Through this relationship, the ancestors can help improve our lives, whether that’s spiritually, emotionally, financially or however we need them to.

For Black folks who are interested in Hoodoo, Hess suggests,

“If you’re curious about something and it peaks your interest, ask why does it peak your interest? If you see a Hoodoo talking about a particular ancestor, dive deeper about that. If you see someone talking about how to use plants and herbs and you still feel called to it, if you have memories from childhood where you used to talk to trees, dive into that.”

It’s through this exploratory process that we can begin to understand the work that our ancestors are calling us to do.

During this fourth annual Hoodoo Heritage Month, Mama Rue shares,

“I am so proud of what the younger people are doing with this information. I’m so proud of the journeys that they have the courage to plant their feet on and start taking those steps and manifesting and creating the life that they want for themselves, their families, and their community.”

This Hoodoo Heritage Month, it’s important to remember that there is no right or wrong way to practice Hoodoo. While different families and regions practice differently, Hoodoo is inclusive of all of our differences. Hoodoo is in our blood. It’s how we live, and it’s a reminder that we need our ancestors, community, and the Earth to truly thrive.

RELATED CONTENT: I Followed African Spirituality for A Year, Here’s How It Changed Me

13 notes

·

View notes