#denis langlois

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Oups ! 😁 🐕

"Le premier miroir fut la flaque d'eau. Difficile à emporter dans son sac."

Denis Langlois

Gif Imgur

#gif animé#imgur#flaque d'eau#oups#humour#funny pics#quotes#denis langlois#cute dog#chien#funny dog#funny animals#fidjie fidjie

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Je pense à Philippe FREY, le premier à avoir traversé en solitaire, sans assistance, LE SAHARA, de la mer Rouge à L'océan Atlantique (Mauritanie)

" Il avait fait le désert de Gobi, le Sahara, l'Atacanna, le Kalahari ; il lui restait à affronter le plus difficile : le désert du cœur "

Denis Langlois ( Revue 《Secousse》juin 2016 )

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Van Gogh and Me.

In his lifetime, Van Gogh managed to sell a single painting, having died in poverty. Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh, one of the most important precursors of modern painting. The son of a Protestant pastor, he was born in 1853, in Groot-Zundert, and his career was permanently marked by great changes. Initially (1869-1876), Van Gogh worked in several branches of the Goupil Gallery, interrupting this activity to study Theology in Amsterdam. Soon, however, he abandoned his studies and decided to make a career as a secular preacher, which took him to Belgium, where he worked for two years, then changing his profession. In 1881, he attended the Brussels Academy of Fine Arts for a few months. Two years followed in Paris, during which he learned the basic techniques of watercolor and oil painting. Between 1886 and 1887, Van Gogh lived in Paris with his brother Theo, who supported him financially.

The decisive change in his life came in February 1888, when he moved to the south of France, where he lived and worked with Paul Gauguin. Many of his best-known paintings (Coffee at Night, The Bridge of Langlois, The Bridge of Arles and Cornfield with Cypresses) are the result of his work from that year. Self-Portrait with a Severed Ear (1889) indicates the latent tragedy that would later completely ruin his life.

Art and commerce dominated the jubilee year of the talented painter, who for much of his life struggled with enormous financial difficulties.

Van Gogh's works reach very high prices on the art market: An indian ink drawing by the Dutch painter was sold at auction for around 1,230,000. During his lifetime, however, this type of recognition was completely denied him. On July 27, 1890, he shot himself with a revolver; The resulting injuries were so severe that they caused his death two days later.

#taylor swift#artists on tumblr#donald trump#star wars#super mario#welcome home#ariana grande#ciara#iggy azalea#miley cyrus

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

"SNATCHED PURSE AND RAN," Montreal Gazette. January 22, 1913. Page 3. --- Arrest of Two Boys Who Are Alleged Thieves. ---- Two young fellows, who are alleged to have stolen a purse containing nine dollars from Mrs. Lambert Villeneuve, 1647 St. Dominique street, αι noon Monday at the corner of Villeneuve and St. Dominique streets, and who are thought to have been connected with other robberies committed in the north end of the city, were arrested yesterday morning and locked up at the Laurier avenue police station. They are Rosario Cyr, 22 years of age, 1367 St. Lawrence street and Orphila Dupont, 21 years of age, 1408 St. Dominique street.

Mrs. Villeneuve was on her way to a grocery store at noon Monday when her purse was snatched by two young fellows. When they got the purse. they jumped into a coal cart that was passing and urged the driver to whip up his horse and dashed up St. Dominique street. The drivers of two oth er wagons, who saw what had happened, whipped up their horses and gave chase to the coal cart. When the two young fellows who had taken Mrs. Villeneuve's purse saw that they were being pursued and overtaken. they jumped from the coal cart opposite the Church of the Infant Jesus and ran through a lane off Laurier avenue and disappeared into a lumber yard.

The driver of the coal cart at first denied knowing who the young fellow were, but finally admitted that he did, and gave their names of Cyr and Dupont to Captain Choquette of the Laurier avenue police station. He claimed he did not know they had stolen anything when they jumped on his cart and urged him to whip up his horse.

Captain Choquette put Constables Langlois and Lefleur to work on the case to try and capture the pair who had stolon the purse. They persuaded Mrs. Villeneuve to Iny complaints against Cyr and Dupont, on which warrants were issued for their arrest. The two were taken into custody at their homes yesterday morning and locked up at the Laurier avenue po lice station. This morning they will be brought up in the Arraignment Court.

The police of the Laurier avenue station claim that both the accused have bad records, and may have been implicated in other robberies that have been committed recently in the north end of the city.

#montreal#arraignment court#purse snatchers#purse snatching#theft#crime spree#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada#long criminal records

0 notes

Photo

Gilbert Tourte (l-r) Directors Claude Lelouch, Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Louis Malle and Roman Polanski at a Press Conference Announcing That They were Shutting Down the Cannes Film Festival in Solidarity With the Striking Students and Workers in Paris and Throughout France, Cannes May, 1968

The news conference had been called to address the Langlois Affair, the scandal that erupted when the popular leftist director of the Cinémathèque Française, Henri Langlois, was removed from his position by the French government. Many in the cinema world thought his removal was for political reasons although French Culture Minister André Malraux, himself an old leftist, denied this, saying Langlois had been removed due to incompetence. Truffaut arrived in Cannes the night before the news conference. When he rose to speak at the conference, Truffaut stated that with factories occupied by striking workers, students at the barricades and trains stopped, it was ridiculous to continue the Festival. Godard agreed, calling for the Festival to be closed, with those who worked in cinema showing solidarity with the striking workers and students. Claude Lelouch, Jean-Claude Carrière, actress Macha Méril and jury members Louis Malle and Roman Polanski all announced that in, in solidarity with the workers and the students who were protesting across France, the festival must close. Louis Malle, Monica Vitti, Roman Polanski, and Terence Young resigned from the international jury and Alain Resnais, Claude Lelouch, Carlos Saura, and Miloš Forman asked for their films to be withdrawn from the competition.

“We’re talking solidarity with students and workers and you’re talking about dolly shots and close-ups. You’re assholes.” Jean-Luc Godard, at the press conference in Cannes announcing the directors solidarity with the striking workers and students throughout France. May, 1968

Jean-Luc Godard - 1930-2022 - Ave atque Vale

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

A goodbye

After almost 12 (!) years, it’s time for me to say goodbye to this blog. It will not be deleted though.

Here’s a (pretty rough and I’m sure not full) list of skaters featured here. They’re listed in alphabetical order by the first name (so “Ashley Wagner” is under “A” and not “W”). I know it’s not the correct way to do this thing but it was easier for me. Also, if you can’t find someone, try searching within the blog or just general Tumblr search.

Thank you for the company and bye!

Women

Adelina Sotnikova

Akiko Suzuki

Alaine Chartrand

Alena Kostornaia

Alena Leonova

Alexandra Trusova

Alexia Paganini

Alina Zagitova

Alissa Czisny

Alysa Liu

Amber Glenn

Amelie Lacoste

Anna Pogorilaya

Anna Shcherbakova

Ashley Wagner

Audrey Shin

Bradie Tennell

Carolina Kostner

Christina Gao

Cynthia Phaneuf

Ekaterina Gordeeva

Elena Radionova

Elene Gedevanishvili

Elizabet Tursynbaeva

Elizaveta Nugumanova

Elizaveta Tuktamysheva

Emmi Peltonen

Eunsoo Lim

Evgenia Medvedeva

Gabrielle Daleman

Gracie Gold

Haein Lee

Irina Slutskaya

Jenna McCorkell

Jenni Saarinen

Joannie Rochette

Josefin Taljegard

Joshi Helgesson

Julia Lipnitskaya

Kaetlyn Osmond

Kailani Craine

Kanako Murakami

Kaori Sakamoto

Karen Chen

Kiira Korpi

Kristi Yamaguchi

Ksenia Makarova

Lara Naki Gutmann

Laura Lepisto

Laurine Lecavelier

Loena Hendrickx

Madeline Schizas

Mae Berenice Meite

Mai Mihara

Mao Asada

Maria Artemieva

Maria Sotskova

Mariah Bell

Marin Honda

Michelle Kwan

Miki Ando

Mirai Nagasu

Polina Edmunds

Polina Korobeynikova

Pooja Kalyan

Rachael Flatt

Roberta Rodeghiero

Rika Hongo

Rika Kihira

Samantha Cesario

Sarah Meier

Sasha Cohen

Satoko Miyahara

Shizuka Arakawa

Sofia Samodurova

Stanislava Konstantinova

Viktoria Helgesson

Yelim Kim

Yu-Na Kim

Wakaba Higuchi

Zijun Li

Men

Adam Rippon

Adian Pitkeev

Alban Preaubert

Alexei Bychenko

Alexei Yagudin

Artur Gachinski

Brendan Kerry

Boyang Jin

Brian Joubert

Brian Orser

Chafik Besseghier

Daisuke Takahashi

Daniel Samohin

Denis Ten

Deniss Vasiljevs

Dmitri Aliev

Evan Lysacek

Evgeni Plushenko

Florent Amodio

Han Yan

Ilia Kulik

Jason Brown

Javier Fernandez

Jeffrey Buttle

Jeremy Abbott

Jeremy Ten

Johnny Weir

Joshua Farris

Jun-Hwan Cha

Max Aaron

Ryan Bradley

Michal Brezina

Keegan Messing

Keiji Tanaka

Kevin Aymoz

Kevin Reynolds

Kevin Van Der Perren

Kurt Browning

Matteo Rizzo

Mikhail Kolyada

Maxim Kovtun

Misha Ge

Moris Kvitelashvili

Nam Nguyen

Nan Song

Nathan Chen

Nobunari Oda

Patrcik Chan

Richard Dornbush

Sergei Voronov

Shawn Sawyer

Shoma Uno

Stephane Lambiel

Stephen Carriere

Takahiko Kozuka

Takahito Mura

Tatsuki Machida

Tomas Verner

Vincent Zhou

Yuma Kagiyama

Yuzuru Hanyu

Pairs

Alexa Scimeca Knierim and Chris Knierim

Alexandra Boikova and Dmitri Kozlovski

Alexandra Paul and Mitchell Islam

Aljona Savchenko and Robin Szolkowy/Bruno Massot

Amanda Evora and Mark Ladwig

Anabelle Langlois and Cody Hey

Anastasia Mishina and Alexander Galliamov

Ashley Cain and Timothy Leduc

Caitlin Yankowskas and John Coughlin/Joshua Reagan/Hamash Gaman

Caydee Denney and Jeremy Barrett/John Coughlin

Dan Zhang and Hao Zhang

Deanna Stellato and Nate Bartholomay / Maxime Deschamps

Ekaterina Alexandrovskaya and Harley Windsor

Ekaterina Gordeeva and Sergei Grinkov

Elena Berezhnaya and Anton Sikharulidze

Evgenia Tarasova and Vladimir Morozov

Felicia Zhang and Nate Bartolomay

Gretchen Donlan and Andrew Sperroff/Nate Bartolomay

Haven Denney and Brendan Frazier

Jamie Sale and David Pelletier

Jessica Dube and Bryce Davison/Sebastien Wolfe

Julianne Seguin and Charlie Bilodeau

Katarina Gerboldt and Alexander Enbert

Keauna McLaughlin and Rockne Brubaker

Kirsten Moore-Towers and Dylan Moscovitch/Michael Marinaro

Kristina Astakhova and Alexei Rogonov

Ksenia Stolbova and Fedor Klimov

Lubov Iliushechkina and Nodari Mausiradze/Dylan Moscovitch

Maria Mukhortova and Maxim Trankov

Maria Petrova and Alexei Tikhonov

Marissa Castelli and Simon Shnapir/Mervin Tran

Mary Beth Marley and Rockne Brubaker

Meagan Duhamel and Eric Radford

Miriam Ziegler and Severin Kiefer

Narumi Takahashi and Mervin Tran/Ryuichi Kihara

Natalia Zabijako and Alexander Enbert

Nicole Della Monica and Matteo Guarise

Paige Lawrence and Rudi Swiegers

Peng Cheng and Hao Zhang/Yang Jin

Qing Pang and Jian Tong

Rena Inoue and John Baldwin

Riku Mihura and Ryuichi Kihara

Stefania Berton and Ondrej Hotarek

Tae-Ok Ryom and Ju-Sik Kim

Tarah Kayne and Denny O'Shea

Tatiana Totmianina and Maxim Marinin

Tatiana Volosozhar and Stanislav Morozov/Maxim Trankov

Valentina Marchei and Ondrej Hotarek

Vanessa James and Morgan Cipres

Vera Bazarova and Yuri Larionov/Andrei Deputat

Wenjing Sui and Cong Han

Xiaoyu Yu and Yang Jin/Hao Zhang

Xue Shen and Hongbo Zhao

Xuehan Wang and Lei Wang

Yuko Kavaguti and Alexaner Smirnov

Ice Dance

Albena Denkova and Maxim Staviski

Alisa Agafonova and Alper Ucar

Alexandra Aldridge and Daniel Eaton / Matthew Blackmer

Alexandra Nazarova and Maxim Nikitin

Alexandra Stepanova and Ivan Bukin

Anna Cappellini and Luca Lanotte

Anna Yanovskaya and Sergei Mozgov

Carolane Soucisse and Shane Firus

Cecilia Torn and Jussiville Partanen

Charlene Guignard and Marco Fabbri

Ekaterina Bobrova and Dmitri Soloviev

Ekaterina Riazanova and Ilia Tkachenko

Elena Ilinykh and Nikita Katsalapov/Ruslan Zhiganshin

Elisabeth Paradis and Francois-Xavier Ouellette

Emily Samuelson and Evan Bates

Federica Faiella and Massimo Scali

Federica Testa and Lucas Csolley

Gabriella Papadakis and Guillaume Cizeron

Isabella Tobias and Deividas Stagniunas/Ilia Tkachenko

Isabelle Delobel and Olivier Schoenfelder

Kaitlin Hawayek and Jean-Luc Baker

Kaitlyn Weaver and Andrew Poje

Kana Muramoto and Chris Reed / Daisuke Takahashi

Kavita Lorenz and Panagiotis Polizoakis

Kharis Ralph and Asher Hill

Ksenia Monko and Kirill Khaliavin

Laurence Fournier Beaudry and Nikolaj Sorensen

Lilah Fear and Lewis Gibson

Madison Chock and Greg Zuerlein / Evan Bates

Madison Hubbell and Kiefer Hubbell/Zachary Donohue

Maia Shibutani and Alex Shibutani

Mari-Jade Lauriault and Romain Le Gac

Marie-France Dubreuil and Patrice Lauzon

Marina Anissina and Gwendal Peizerat

Margarita Drobiazko and Povilas Vanagas

Meryl Davis and Charlie White

Misato Komatsubara and Tim Koleto

Nelli Zhiganshina and Alexander Gazsi

Natalia Kaliszek and Maksim Spodyrev

Nathalie Pechalat and Fabian Bourzat

Nicole Orford and Thomas Williams/Asher Hill

Nora Hoffmann and Maxim Zavozin

Oksana Domnina and Maxim Shabalin

Olivia Smart and Adria Diaz

Penny Coomes and Nicholas Buckland

Pernelle Carron and Lloyd Jones

Piper Gilles and Paul Poirier

Sara Hurtado and Adria Diaz

Sinead Kerr and John Kerr

Shiyue Wang and Xinyu Liu

Tanith Belbin and Benjamin Agosto

Tatiana Navka and Roman Kostomarov

Tessa Virtue and Scott Moir

Tiffany Zahorski and Jonathan Guerreiro

Vanessa Crone and Paul Poirier

Viktoria Sinitsina and Nikita Katsalapov

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gnostic Boardwalk

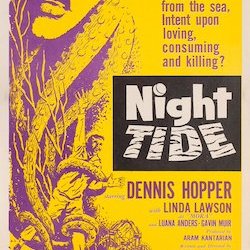

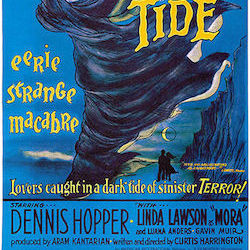

Canonical stature is a fragile and contingent thing, which is why powerful institutions seek to shore up the various canons of art with rankings and plaudits. We’ll play along by asserting that one of our favorite “B” movies was originally screened by Henri Langlois at the Cinematheque française with Georges Franju in attendance. Night Tide (1961) was an unlikely contender for this particular honor—shot guerrilla style on an estimated $35,000 budget, and intended, by its distributors at least, for a wider, less demanding audience seeking mostly air-conditioned escapism.

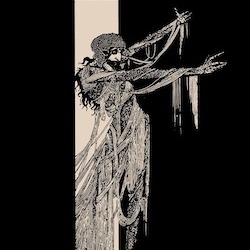

With its hinky cast—nonfictional witch, Marjorie Cameron; erstwhile muse to surrealist filmmaker Jean Cocteau, the undersung Babette who usually appears en travesti; and lecherous, booze-addled, fresh-faced Hollywood castoff Dennis Hopper—Night Tide invades the drive-in. A tarot reading at the film’s heart gives Marjorie Eaton her time to shine, traipsing into nickel-and-dime divination from her former life as a painter of Navajo religious ceremonies. Linda Lawson might have issued from an etching by Odilon Redon, with her raven locks and spiritual eyes, our resident sideshow mermaid. Not surprisingly and despite such gentle segues, the film itself traveled a rocky road from festivals to paying venues.

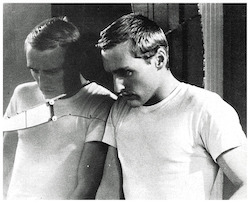

Night Tide had spent three years languishing in the can when distributor Roger Corman smuggled the unlikely masterwork into public consciousness, another of his now legendary mitzvahs to art. And the sleazy-sounding double bills that resulted also unleashed an aberrant wonder: the movie’s compact leading man, a force previously held captive by the studio system—looking, here, like some homunculus refugee from the Fifties USA. Dennis Hopper, in his first starring role, would later recall that it represented his first “aesthetic impact” on film since his earlier appearances in more mainstream productions such as Rebel Without a Cause and Giant had denied him meaningful outlets for collaboration.

It’s the presence of its featured players—certainly not their star power—that lends the film its haunting and enduring legacy, and elevates the term “cult classic” to its rightful place in the pantheon of cinema. But we argue that Night Tide remains outside these exclusive parameters—upholding an elsewhere-ness that defies commercial, if not strictly canonical, logic. Curtis Harrington’s first feature film escapes taxonomy, typology or genre—gets away—fueling itself on acts of solidarity instead. If Hopper contributes his dreamy aura, then Corman rescues the seemingly doomed project by re-negotiating the terms of a defaulted loan to the film lab company that was preventing the film’s initial release. His generous risk birthed a movie monument that would add Harrington’s name to a growing collection of talent midwifed by the visionary schlockmeister responsible for nursing the auteurs of post-war American cinema. And here we enter a production history as gossamery as Night Tide itself.

Unlike his counterparts entrenched within the studio system, Harrington was an artist – i.e. a Hollywood anachronism, with aristocratic graces and a viewfinder trained on the unseen. We see Harrington as Georges Méliès reborn with a queer eye, casting precisely the same showman’s metaphysics that spawned cinema onto nature. By the time moving pictures were invented, artists were moving away from a bloodless representational ethos and excavating more primordial sources for inspiration. The early stirrings of what surrealist impresario André Breton would later proclaim: “Beauty will be CONVULSIVE or it will not be at all.”

Harrington owned a pair of Judy Garland’s emerald slippers, and according to horror queen/cult icon Barbara Steele, also amassed an eclectic array of human specimens: “Marlene Dietrich, Gore Vidal, Russian alchemists, holistic healers from Normandy, witches from Wales, mimes from Paris, directors from everywhere, writers from everywhere and beautiful men from everywhere.” On a hastily constructed Malibu boardwalk, Hopper would be in his milieu among the eccentric denizens of California’s artistic underground—most notably, Harrington himself, a feral Victorian mountebank of a director who slept among mummified bats, practiced Satanic rites, and hosted elaborate and squalid dinner parties. One could almost picture the mostly television director in his twilight years as Roman Castavet of Rosemary’s Baby; a spellbinding raconteur with a carny’s flair for embellishment and enticement. Enthralled by the dark gnosticism of Edgar Allan Poe that had started when the aspiring 16-year-old auteur mounted a nine-minute long production of The Fall of the House of Usher (1942), Harrington would embark on a checkered film career that combined his occult passions with the quotidian demands of securing steady employment. Night Tide, a humble matinee feature whose esoteric underpinnings would spawn subsequent generations of admirers, united the competing forces of art and commerce that Harrington would struggle with throughout his career. Like Méliès, Harrington pointed his kinetic device towards the more preternatural aspects of early motion pictures to seek out the ‘divine spark’ that Gnostics attribute to transcendence, and the necessary element to achieve that immortal leap into the unknown. What hidden meanings and unspeakable acts Poe had seized upon in his writing were brought infernally to life with a mechanical sleight-of-hand. It was finally time for crepuscular light, beamed through silver salts to illuminate otherworldly and other-thinking subjects.

Curtis Harrington

By the time Harrington had embarked on his feature film debut, a more muscular celluloid mythology based on America’s proven exceptionalism was in full force, taking on a brutalist monotone cast in keeping with the steely-eyed, square-jawed men at the helm of a nascent super-power, consigning its more feminine preoccupations to the dusty vaults where celluloid is devoured by its own nitrate. Harrington would resurrect the convulsive aspects of his chosen vocation and embed them deep within the monochrome canvas he’d been allotted for his first venture into feature filmmaking, and combine them with the more rational aspects of so-called realism. In the romantic re-telling of a familiar myth, Harrington was remaining true to gnostic roots and the distinctly poetic language used to express its cosmological features.

In Night Tide, Harrington would map the metaphysical terrain that held up Usher’s cursed edifice as a blueprint for his own work that similarly explored the intertwined duality of the natural and the supernatural. The visible cracks that reveal a fatal structural weakness and a loss of sanity in both Roderick Usher and his doomed estate are evident in Night Tide’s conflicted heroine compelled to choose between her own foretold death underwater, or a worse fate for those who fall in love with her earthly human form.

A young sailor (Dennis Hopper) strolling the boardwalks of Malibu while on shore leave offers the viewer an opening glimpse into the film’s metaphysical wormhole, and a not so subtle hint of the director’s queer eye, stalking his virginal prey in the viewfinder. A beachfront entertainment venue is, after all, where one would casually encounter soothsayers and murderers, sea witches and perverts, as the guileless Johnny does, seemingly oblivious to the surrealist elements of his surroundings as he makes his way on land.

Harrington’s carnival-themed underworld is both imaginatively and convincingly presented as a quaint slice of post-war America, effortlessly dovetailing with his intended drive-in audience’s expectations of grind house with a dash of glamor—not to mention his own avant-garde leanings, which remain firmly intact despite Night Tide’s outwardly conventional construction and narrative.

Harrington is able to present this juxtaposition of kitsch Americana and the queer arcana of his occult fascinations. Indeed, Night Tide’s lamb-to-the-slaughter protagonist could have wandered off the set of Fireworks, Kenneth Anger’s 1947 homoerotic short film about a 17-year-old’s sadomasochistic fantasies involving gang rape by leathernecks.

Anger would later sum up his earliest existing film as “A dissatisfied dreamer awakes, goes out in the night seeking a ‘light’ and is drawn through the needle’s eye. A dream of a dream, he returns to bed less empty than before.” Harrington (a frequent collaborator of Anger in his youth) seems to have re-worked Fireworks, or at least its underlying queer aesthetic into a commercially viable feature film that explores his own life long occult fascinations.

Both Anger and his former protégé would view the invocation of evil as a necessary step towards the attainment of a higher level of consciousness. Harrington coaxed a more familiar story from the myths and archetypes that informed his unworldly views for a wider audience; a move that would be later interpreted by sundry cohorts as selling out. Still, Night Tide shares a thematic kinship with Anger’s more obtusely artistic output as acknowledged by the surviving occultist, who confirmed this unholy covenant at Harrington’s funeral by kissing his dead friend on the lips as he laid in his open coffin.

The hokey innocence of Dennis Hopper as Johnny Drake in his tight, white sailor suit casts a homoerotic hue on the impulses that compel him to navigate a treacherous dreamscape to satisfy a carnal longing, just as Anger’s dissatisfied dreamer obeys the implicit commands of an unspeakable other to seek out forbidden pleasures.

As he makes his way on land, the solitary, adventure-seeking Johnny will be lured into a waiting photo booth, his features slightly menacing behind its flimsy curtain, and brightly smiling a second later as the flash illuminates them. Johnny has entered a realm where intersecting worlds collide, delineating light from shadow, consciousness from unconsciousness. The young sailor’s maiden voyage into the uncharted waters of his subconscious is made evident in the contrasting interplay captured by the camera, where predator and prey overlap in darkness. Here, too, we get a prescient preview of the deranged psychopath Hopper would subsequently personify in later roles, most significantly as the oxygen deprived Frank of Blue Velvet—a man who seems to be drowning out of water. But here, Hopper convincingly (and touchingly) portrays a wide-eyed naïf, still unsteady on his sea legs as he negotiates dry land.

As a variation of Anger’s lucid dreamer in Fireworks (and later Jeffrey of Blue Velvet) Johnny will have abandoned himself quite literally (as his departing shadow on a carnival pavilion suggests, before its host blithely follows) to his own suppressed sexual urges; a force that eventually compels him towards denouement.

Moments later, inside the Blue Grotto where a flute-led jazz combo is in progress, Johnny spots a beautiful young woman (Linda Lawson) seated directly across from him. Her restrained and almost involuntary physical response to the music mimic his own, offering the first indication of a gender ‘other’ residing in Johnny; an entombed apparition cleaved from the sub-conscious and projected into his line of vision. Roderick and Madeline Usher loom large in Harrington’s screenplay and Usher’s trans themes lurk invisibly in the subtext. Harrington is arguably heir apparent to Poe’s vacated throne, pursuing similar clue-laden paths and exploring the dual nature of human and the primordial creature just beneath the surface poised to devour its host.

The near literal strains of seductive Pan pipes buoyed by the ‘voodoo’ percussion sets the stage for Harrington’s reworking of the ancient legend of sea-based seductresses and the sailors they lure to their graves.

Marjorie Cameron (or ‘Cameron’ as she is referred to in the opening credits) makes a startling entrance into The Blue Grotto as an elder of a lost tribe of mermaids seeking the return of an errant ‘mermaid’ to her rightful place in the sea. Cameron, a controversial fixture in L.A.’s bohemian circles and one-time Scarlet Women in the mold of Aleister Crowley’s profane muses, would later appear in Anger’s The Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome, and as the subject of Harrington’s short documentary The Wormwood Star (1956).

The inclusion of a bonafide witch, along with a host of less apparent occult/avant-garde figures, is further evidence of Night Tide’s true aspirations and its filmmaker’s subversive intent to sneak an art-house film into the drive-in, and introduce its audiences to the heretical doctrine that had spawned a new generation of occult visionaries influenced by Edgar Allan Poe. Decades later, David Lynch would carry that proverbial torch, further illuminating the writhing, creature-infested realm underlying innocence.

Johnny approaches the young woman who rebuffs his attempts at conversation, seemingly entranced by the music, but allows him to sit, anyway. Soon they are startled by the presence of a striking middle-aged woman (‘Cameron’) who speaks to Johnny’s companion Mora in a strange tongue. Mora insists that she has never met the woman before, nor understands her, but makes a fearful dash from the club as Johnny follows her, eventually gaining her trust and an invitation the following day for breakfast.

Mora lives in a garret atop the carousal pavilion at the boardwalk carnival where she works in one of the side show attractions as a “mermaid.” Arriving early for their arranged breakfast, her eager suitor strikes up a conversation with the man who runs the Merry-Go-Round with his granddaughter, Ellen (Luanna Anders). Their trepidation at the prospecting Johnny becoming intimately acquainted with their beautiful tenant is apparent to all except Johnny himself, who is even more oblivious to Ellen’s wholesome and less striking charms. Even her name evokes the flat earth, soul-crushing sensibilities of home and hearth. Ellen Sands is earthbound Virgo eclipsed by an ascendent Pisces. (Anders would have to subordinate her own sex appeal to play this mostly thankless “good girl” role. She would be unrecognizable a few years later as a more brazenly erotic presence in Easy Rider, helping to define the Vietnam war counterculture era.)

As Johnny ascends the narrow staircase leading to Mora’s sunlit, nautical-themed apartment, he almost collides with a punter making a visibly embarrassed retreat from the upper floor of the carousel pavilion. Is Johnny unknowingly entering into a realm of vice and could Mora herself be a source of corruption? Her virtue is further called into question when she not so subtly asks Johnny if he has ever eaten sea urchin, comparing it to “pomegranate” lest her guest fails to register the innuendo that is as glaring as the raw kipper on his breakfast plate. Johnny admits that he has never eaten the slippery delicacy but “would like to try.” Moments later, Mora’s hand in close-up is stroking the quivering neck of a seagull she has lured over with a freshly caught fish, sealing their carnal bond.

Their subsequent courtship will be marred by an ongoing police investigation into the mysterious deaths of Mora’s former boyfriends, and her insistence that she is being pursued by a sea witch, seeking the errant mermaid’s return to her own dying tribe. Her mysterious stalker will make another unwelcome entrance after her first appearance in the Blue Grotto—this time at an outdoor shindig where the free-spirited young woman reluctantly obliges the gathered locals who urge her to dance. The sight of ‘Cameron’ observing her in the distance causes the frenzied, seemingly spellbound dancer to collapse, setting off a chain of events that will force Johnny to further question her motives and his own sanity.

Mora’s near death encounter through dance is an homage of sorts to another early Harrington collaborator and occult practitioner. Experimental filmmaker Maya Deren had authored several essays on the ecstatic religious elements of dance and possession, and later went on to document her experiences in Haiti taking part in ‘Voudon’ rituals that would be the basis of a book and a posthumously released documentary both titled Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti. Note the Caribbean drummers whose ‘unnatural’ presence, in stark contrast to the more typical Malibu beach party celebrants, hint at the influence of black magic impelling the convulsive, near heart-stopping movements that eventually overtake her ‘exotic’ interpretive dance.

The opening sequence of Divine Horsemen includes a woodblock mermaid figure superimposed over a ‘Voudon’ dancer. The significance of this particular motif was likely known to Harrington, a devotee of this early pioneer of experimental American cinema. Deren herself appeared as a mermaid-like figure washed ashore in At Land (1947) who pursues a series of fragmented ‘selves’ across a wild, desolate coastline. Lawson with her untamed black hair and bare feet could be a body double of Deren’s elemental entity traversing unfamiliar physical terrain to find a way back to herself.

Mora’s insistence that she is being shadowed by a malevolent force directly connected to her mysterious birth on a Greek Island and curious upbringing as a sideshow attraction compel Johnny to investigate her paranoid claims, hoping to allay her fears with a logical explanation for them. The sea witch (or now figment of his imagination) will guide the sleuthing sailor into a desolate, mostly Mexican neighborhood where her departing figure will strand him—right at the doorstep of the jovial former sea captain who employs Mora in his tent show as a captive, “living, breathing mermaid.”

The British officer turned carnie barker is in a snoring stupor when Johnny first encounters him, snapping unconsciously into action to give a rote spiel on the wonders that await inside his tent. Muir balances Mudock’s feigned buffoonery with a slightly sinister edge. When Johnny arrives at his doorstep to find out more about the ongoing police investigation into her previous boyfriend’s deaths, the captain’s effusive hospitality takes on a decidedly darker tone when he guides his visitor to his liquor/curio cabinet where a severed hand in formaldehyde, “a little Arabian souvenir,” is cunningly placed where Johnny’s will see it. The spooky appendage serves as a reminder to Mora’s latest suitor of the punishments in store for a thief.

Captain Murdock’s Venice beach hacienda is yet another one of Night Tide’s deviant jolts: a fully fleshed out character in itself that speaks of its well-travelled tenant’s exotic and forbidden appetites. The dark, symbol-inscribed temple Johnny has entered at 777 Baabek Lane could be a brick-and-mortar portal into this mythic, mermaid-populated dimension that Johnny’s booze-soaked host thunderously defends as real.

Before falling into another involuntary slumber, Murdock will try to convince Johnny that while he and Mora merely stage a sideshow illusion, “Things happen in this world”—or, more to the point, Mora’s belief that she is a sea creature is grounded in fact.

Murdock’s business card that Johnny handily has in his pocket while tailing his dramatically kohl-eyed mark is oddly inscribed with an address more likely to be an ancient Phoenician temple of human sacrifice (Baalbek) than a Venice Beach bungalow. A lingering camera close-up offers another tantalizing, occult-themed puzzle piece—or perhaps a deliberate Kabbalah inspired MacGuffin. The significance of numbers as the underlying components for uniting the nebulous and intangible contents of the mind with the more inert, gravity bound matter, existing outside it, as the ancient Hebrews believed, wouldn’t have been lost on Night Tide’s mystically-minded helmer. Mora’s explicitly expressed disdain for Johnny’s view of the world as a rationally ordered, measurable entity that could be mathematically explained, reinforces Harrington’s world view, his love of Poe, and those French Symbolist artists who interpreted him.

In Odilon Redon’s Germination (1879), a wan, baleful, free-floating arabesque of heads of indeterminate gender suggests either a linear, ascending involution, or a terrifying descent from an unlit celestial void into a bottomless pit of an all-too-human, devolving identity. Redon’s disembodied heads gradually take on more human characteristics, culminating into a black-haloed portrait in profile. The cosmos of Redon’s etching is governed by an unexplained, inexplicable moral sentience, which absorbs the power of conventional light. Thus black is responsible for building its essential form, while glimmers of white, hovering above and below, prove ever elusive; registering as somehow elsewhere, beyond the otherwise tenebrous unity of the picture plane.

Night Tide has its own unsettling dimensions, of course, this black-and-white boardwalk where astral, egalitarian bums want to tip-toe; and, somehow, practically all of them do. Not a movie but an ever-becoming place, crammed into low-budget cosmogenesis unto eternity. We won’t discuss the ending here, since it hasn’t happened yet.

by The Lumière Sisters

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jean Giono sur ses terres

Un roi sans divertissement et autres romans

de Jean Giono

Préface de Denis Labouret, éditions et notes de Pierre Citron, Henri Godard, Janine et Lucien Miallet, Luce Ricatte et Robert Ricatte

La Pléiade, 1 360 p., 60 € jusqu’au 31 août (66 € ensuite)

Cahier de l’Herne Giono

dirigé par Agnès Castiglione et Mireille Sacotte

288 p., 33 €

Publié de son vivant en février 1970 – il mourut à 75 ans en octobre de la même année -, L’Iris de Suse, dernier roman de Jean Giono, parut dans une indifférence quasi générale. Longtemps, à l’exception de ses lecteurs fidèles et malgré les six volumes de La Pléiade, son œuvre ne fut pas mise à la place qu’elle mérite. Réunissant certaines de ses fictions, de Colline à L’Iris de Suse, ce nouveau tome de La Pléiade ouvre l’accès au cœur de l’œuvre. Comme Henri Bosco ou André Dhôtel, encore méconnus, Giono a délimité un domaine qui a ses propres lois.

Sa vie, ses lectures, son écriture se mêlent en un même tissu et il raconte dans Jean le Bleu (1932) comment la littérature fit échapper le héros, son double, à ce qui est pour ses personnages le mal suprême : l’ennui. Fils d’un cordonnier et d’une repasseuse, Giono fut initié à la littérature au collège et, surtout, grâce aux livres de ses parents. Bien des familles paysannes pauvres lisaient alors les classiques, les conservaient d’une génération à l’autre et, dans des collections à bon marché, découvraient des œuvres plus récentes.

Giono arpenta une contrée imaginaire, sauvage, battue des vents, écrasée par un soleil noir et des orages subits, où la beauté est tragique

Très tôt, son monde intérieur fut habité par de grandes présences : Homère, les tragiques grecs, la Bible, Shakespeare, Pascal, L’Arioste, très tôt aussi il se lança dans l’aventure de l’écriture et délimita une topologie romanesque autour de Manosque, la montagne de Lure, la Durance, la Haute-Provence, le sud des Alpes. Utilisant les noms de villages et de lieux-dits, s’amusant à les déplacer, à en inventer, il arpenta une contrée imaginaire, sauvage, battue des vents, écrasée par un soleil noir et des orages subits, où la beauté est tragique : « L’écrivain qui a le mieux décrit cette Provence, c’est Shakespeare », déclarait-il en 1954.

Ce volume de La Pléiade illustre bien comment ce territoire entre réel et invention s’est transformé, de Colline (1929) où la nature, imprévisible, fascinante, inquiétante est la principale force, à L’Iris de Suse où la violence dans les mêmes décors s’efface devant celle des personnages. Entre les deux romans, Giono a été emprisonné deux fois, en 1939 pour « pacifisme » et en 1944, accusé à tort de collaboration. Il renonce alors aux utopies politiques, se désintéresse des institutions humaines. Son espace littéraire est désormais peuplé de hautes figures, des « âmes fortes », monstrueuses parfois, vivant, jusqu’au suicide ou au crime, des passions secrètes et dangereuses.

→ CRITIQUE. Au Mucem, Jean Giono au-delà des clichés

L’Italie n’est jamais loin, ni le Stendhal des Chroniques italiennes. Ses territoires englobent à présent les petites villes, deviennent des labyrinthes : maisons abandonnées, couvents en ruine, terrasses dominant de vastes paysages, châteaux délabrés, chemins oubliés par lesquels arrivent des voyageurs venus d’on ne sait où, comme Monsieur Joseph dans Le Moulin de Pologne. Et le labyrinthe est surtout intérieur, prisons de l’âme rappelant celles de Piranèse. Les êtres ordinaires n’intéressent pas Giono, ils forment le fond du tableau et, à la façon du chœur dans la tragédie grecque, commentent les événements que bien souvent ils ne comprennent pas. Ce qui est au cœur du roman, c’est le combat contre le destin. « Ce sont, a-t-il dit, les êtres exceptionnels et torturés qui disent leurs quatre vérités aux vulgaires et aux médiocres. Ces êtres marqués de Dieu pour un sort exceptionnel contre le vulgaire. »

Les êtres ordinaires n’intéressent pas Giono

Le destin a parfois la forme de l’ennui, auquel seul le divertissement, qui détourne du sentiment de la mort, fait échapper. Fragmentaire dans le titre – Un roi sans divertissement –, complétée aux dernières lignes – « est un homme plein de misère » -, la citation de Pascal enveloppe l’histoire de Langlois, capitaine de gendarmerie chargé de résoudre l’énigme de meurtres en série commis durant six hivers consécutifs entre 1843 et 1848 dans un village du Vercors, où rien ne se passe et que la neige recouvre plusieurs mois par an. La neige, le sang : deux motifs récurrents, liés tout au long de la narration, descente dans les abîmes d’une âme, celle de Langlois qui est à lui-même sa propre énigme et qui, découvrant en lui la fascination du crime, choisit hardiment la mort.

Cette bataille est au centre de presque toutes les autres fictions. Dans Le Moulin de Pologne, comme dans les tragédies grecques, la fatalité s’est abattue depuis plusieurs générations sur une famille – les Coste – et la jalousie des dieux semble s’acharner sur les natures d’exception telles que Julie, figure centrale, blessée elle aussi, animal sacrifié : une frayeur soudaine a paralysé la moitié de son visage. Sa façon de chanter avec ferveur à la messe de Pâques a fait scandale : « Nous sommes des chrétiens, bien sûr, mais il ne faut pas nous en demander trop… En nous tout est petit », dit le narrateur, incapable plus tard, lorsque Julie danse et chante seule dans un bal où beaucoup se moquent d’elle, de deviner qu’un drame se joue sur un fond métaphysique invisible.

Pour ce roman, Giono avait hésité entre plusieurs titres comme La rue est à Dieu, suivi de l’épigraphe : Maintenant, Seigneur, laisse aller ton esclave en paix. Fatalité aveugle ? La chute de Léonce, dernier des Coste, est-elle l’effet du Démon ? Ou une punition divine ? Dans Faust en village (1949) le Diable apparaît sous l’apparence d’un auto-stoppeur. Les feuillets et brouillons du romancier témoignent de ses interrogations religieuses et de sa curiosité pour les forces maléfiques, mais il n’a pas donné de réponse.

———————

« La petite lorgnette du régionalisme »

Extrait de la préface de Denis Labouret à l’édition de La Pléiade

« Le romancier fait ainsi éclater toutes les frontières d’une région existante pour créer un «Sud imaginaire» qui n’a de contour sur aucune carte. (…) Ces «Hautes-Collines» (ainsi nommées dans Deux cavaliers de l’orage), ce «Haut Pays» d’Ennemonde, ces plateaux battus par les vents de Regain et de L’Homme qui plantait des arbres, c’est une terre imaginaire qui doit autant à la lecture des auteurs grecs et latins, dévorés et même broutés par Giono dans sa jeunesse, qu’à celle de Whitman ou plus tard de Faulkner – un pays mythique, poétique, souvent tragique. Si Provence il y a, Giono prend donc bien soin d’en refuser les lieux communs, quitte à surprendre, délibérément : «L’écrivain qui a le mieux décrit cette Provence, c’est Shakespeare.» »

https://ift.tt/2wQuVc1

from WordPress https://ift.tt/3eb6V4F via IFTTT

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

QUEL FESTIVAL! QUEL FESTIVAL?

par André ROY

On ne reviendra pas sur le feuilleton montréalais des festivals de films, la donne changeant chaque semaine. La SODEC et Téléfilm Canada ont déclenché une course, qui commence à ressembler à une comédie ubuesque, en déclarant Serge Losique persona non grata et en lançant un appel d'offres pour la tenue d'un festival international digne des plus grands. Mais à vouloir imiter des modèles, on risque de se retrouver avec un rendez-vous cinématographique bancal. On peut encore s'interroger sur tout ce cirque et ce qui en résultera au moment où se termine le Festival du nouveau cinéma de Montréal, qui fut cette année une belle réussite, tant dans le choix des œuvres que dans la fréquentation. Sur ce dernier point, on pourrait dire que le public, très averti en ce cas-ci, avait, consciemment ou non, décidé d'appuyer le projet de Daniel Langlois et Sheila de la Varende dévoilé quelques jours auparavant. Ce projet pourrait se résumer ainsi : vous voulez un grand festival, eh bien, comme Rome ne s'est pas bâtie en un jour, donnez-nous le temps et les moyens de le monter. Les organismes étatiques sont priés de considérer avec sérieux une augmentation annuelle de leurs subventions pour aider au développement, sur trois ans, du Festival du nouveau cinéma. Et après, on verra. Si la SODEC et Téléfilm seraient bien inspirés d'acquiescer au plan triennal du Festival du nouveau cinéma, cela ne nous rassure pas sur la spécificité d'un « grand » festival mondial de films à Montréal.

Mais à quoi sert au juste un festival ? La question n'est peut-être pas aussi inappropriée qu'on le pense. Le FNCM permet d'y répondre en quatre points, qui s'avèrent obligatoires pour une manifestation de son genre, internationale et ouverte au public. Le premier est le plus évident : permettre la découverte de cinéastes, même si plusieurs d'entre eux ont vu leurs films présentés ailleurs. Là-dessus, Claude Chamberlan et ses programmateurs n'ont pas failli à leur tâche en choisissant, par exemple, les œuvres, parfois arides, souvent magnifiques, d'Arnaud des Pallières, d'Abdellatif Kechiche, d'Apichatpong Weerasethakul, de Wang Bing. Le second est d'offrir aux auteurs de marque une place, qu'ils ont difficilement trouvée ou qu'ils maintiennent d'une manière encore précaire, leurs films n'ayant pas un succès monstre au box-office et n'étant toujours pas distribués hors de leur pays ; c'est ce qui est arrivé aux films de Jean-Luc Godard, de Raymond Depardon, de Claire Denis, d'Abbas Kiarostami, de Raoul Ruiz, auteurs pourtant illustres, qui n'ont pas été achetés par des Québécois, quelle misère ! Malgré leur aura, ces cinéastes, qui ont été au fil des ans chouchoutés par Claude Chamberlan, demeurent encore, comme on le constate, des inclassables, des minoritaires.

Le troisième point est de jouer, sans que l'organisation perde trop de vue ses buts propres, avec le star-système afin d'appâter les médias et le supposé grand public : participer au lancement en bonne et due forme de films dont le succès ne fait pas de doute et s'en servir comme locomotives. Sage comme une image, d'Agnès Jaoui, a été choisi exactement pour cette raison. Savoir si l'effet visé a été atteint, cela est à peu près inqualifiable, mais on doute tout de même énormément de son effet d'entraînement.

Et le dernier point, et qui n'est pas le moindre pour tout spectateur préoccupé par l'état d'un cinéma national : les titres québécois, d'André Forcier, de Wajdi Mouawad, de Lucie Lambert et de Francis Leclerc, entre autres, s'intégraient parfaitement à l'ensemble de la sélection. Ce qui prouve que, malgré les conditions difficiles et aléatoires de la production d'ici, des œuvres à part émergent et supportent parfaitement la comparaison avec les films d'ailleurs.

Tous ces points ont convergé de façon équilibrée au récent Festival du nouveau cinéma et ont permis d'assister à un festival qui s'est révélé fort par son abondance d'œuvres majeures. Ce rassemblement a suscité, non pas comme le festival de Losique, de l'ironie et de l'hostilité, mais de la sympathie et, pour notre part, une folle envie de continuer à y partager pendant quelques jours, chaque année, une sorte d'espoir commun : que chaque film soit cette œuvre vitale, libre, riche formellement, qui nous permette de penser le monde (le film emblématique, à cet égard, a été Notre musique de Godard). Il est donc permis de croire à l'utopie devant des films exceptionnels et puissants qui, modestement pour une grande part d'entre eux, affrontent une production dominante, aux scénarios formatés - mais c'est une utopie qu'il faut toutefois tempérer quand on constate l'incertitude de la production, le marasme de la distribution et l'incompétence et la médiocrité de la critique tant d'ici que d'ailleurs. Quand même ! Aller au Festival du nouveau cinéma a été souvent pour nous comme entrer en résistance, se retrouver dans une famille de combattants. C'est certainement ça qui nous tient le plus à cœur : ce sentiment de fraterniser, de se solidariser avec des aventuriers solitaires (trop souvent) et singuliers. Perdrions-nous ce sentiment si le FNCM s'agrandissait et devenait la manifestation tant souhaitée par les institutions gouvernementales ?

Roy, A. (2004). Quel festival! Quel festival? 24 images, (120), 4–4.

1 note

·

View note

Text

L’affaire Saint-Aubin : accident ou crime d’État ?

L’affaire Saint-Aubin : accident ou crime d’État ?

Ancien avocat et écrivain, Denis Langlois a consacré deux ouvrages à l’énigmatique fait divers ayant causé la mort deux jeunes Dijonnais. Après Le mystère Saint-Aubin en 1993, il vient de publier L’affaire Saint-Aubin aux éditions La Différence, nourri de nouveaux éléments. Entretien.

Par Antoine Gavory / Proscriptum Photos D.R.

La présence de certains éléments (les déclarations de Jean…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

" 'Je me dérangerai pour l'Apocalypse, à la rigueur pour la Révolution.' Il finit par se lever pour voir passer le Tour de France."

Denis Langlois

Gif de Tenor

#gif animé#tenor#cycliste#vélo#bicyclette#tour de france#bicycle#quotes#denis langlois#humour#funny pics#fidjie fidjie

22 notes

·

View notes

Quote

When speaking to the Post-Star, the mayor was fuzzy on the details, “I might have,” he said. “I post things all the time. I really don’t remember what I do half the time.” However, he then said, “I’m not doing it as an official; I’m doing it as a person. You can’t quote me as the mayor, you can only quote me as a person. As a mayor I wouldn’t say that, but as a person who believes in Republican values… Most people don’t even know I’m the mayor. Nobody cares anymore.

Mayor defends calling Democratic voters 'r*tarded' on Facebook: 'I have no regrets'

0 notes

Text

Five ways to jazz up your designs with sequins

Sequins are like the stars of the Haute Couture world. The little colored pieces have so much creativity hidden behind them. Do you know that until the 18th century, sequins were made up of metals like gold or silver? However, their costs didn’t allow marketing or distribution. Then was the ingenious idea of cutting sequins in sheets of gelatine. There is no denying that anyone’s wardrobe can be spiced up with a hint of Langlois Martin sequins. Even the simplest of fabrics can be easily transformed into something sassy by incorporating sequins.

How? Well, many businesses are using enticing ways to morph the plain-Jane designs into something eye-catchy and magical. Let's take a deep dive into their ideas and find out how you can be inspired!

From mundane to sparking

For those who don't prefer sewing gluing is an attractive option and enterprises are even using the glue technique. It is one of the easiest and most basic ways of adding glitter to any fabric. Get some loose paillettes, your choice of fabric, and glue. Start gluing the sequins one by one with the help of tweezers, and then give them a scattered look by keeping more spaces among them. You can place the sequins on the neckline, or if you want to get a boho look, you can also glue them at equal distances along the sleeves.

Sequins on denim

Do you want a brand new look to flaunt? Then you can style up your old denim with gold or silver sequins. Get a needle, thread, sequins, and a pair of denim jackets or jeans. Create or embroider a pattern or sew a small sequin and make a circle of other flat sequins around it. Trust us, you will love the look!

Flower Appliques

Searching for an intriguingly adorable way to embellish your designs? Then make sequins flowers. They are trending right now and can be used on practically anything from suits, sarees, and dupattas to tees, tops, and gowns.

Spruce up that old shoe

Only avid shoe collectors know the value of having a beautifully designed glamorous shoe. If your shoes have become monotonous, then you can spice them up by sewing sequins on them. Create small shells, flowers, or any interesting pattern, experiment a little, and create a unique style by designing your shoes your way.

Animate your boring bag

Whether you have a clutch or a shopping bag, if you don’t want to spend a lot of money on an embellished bag, you can add colorful sequins to make your bag as pretty as you want. From simple to intricate, there is a myriad of ways to easily add magic to any fabric within a limited budget.

Conclusion

A universe closely intertwined with embroidery, sequins can instantly make any design pretty. Whether you work with typical old-world sequins or you are stepping up to the French world of Langlois Martin sequins, the only constant is creativity. Get good quality sequins that can be sewn into any fabric. The sequins must stay intact, and of course, their glamor shouldn’t fade. Looking for attractively versatile sequins for your next design? Find them at Finest Beads now!

Source: https://www.finestbeads.com/32998.html

1 note

·

View note

Text

"FAITS DIVERS: Vol de coupons," Le Devoir. April 14, 1943. Page 10. --- Un quatrième inculpé s'avoue coupable - Un autre détenu comme témoin - 7 ans de pénitencier - Inondations --- La Gendarmerie royale du Canada a arrêté hier Harry Dubuc, 6085, des Erables, en rapport avec l'affaire des vols de coupons de rationnement de gazoline. Dubue recevra sa sentence le 16 avril prochain. Il s'est reconnu coupable, lors de sa comparution en correctionnelle. Un autre individu non encore identifié est détenu pour fins d'interrogatoire, d'ici la fin de l'enquête dans cette affaire. Mort tragique Jack Ballon, 62 ans, sans domicile connu, est mort hier au Jewish Hospital of Hope, à Tétreaultville. On l'a trouvé dans sa chambre portant des entailles à la gorge et aux poignets. On croit qu'il s'est servi d'une lame de razoir. Le cadavre est à la morgue.

Au pénitencier Roland Lemire, 25 ans, coupable de 7 vols à main armée commís entre novembre et mars sur des camionneurs devra passer 7 ans au pénitencier dans chaque cas. Le juge Omer Legrand a aussi condamné Jean Dubois, 22 ans, et Lucien Duval, 26 ans, tous deux complices de Lemire, à 3 ans de pé- nitencier dans le premier cas et 2 ans dans l'autre. Le juge Amédée Monet a condamné Ovila Riendeau, 19 ans, et son frère Jean-Paul Riendeau, 22 ans, à 2 ans de pénitencier pour avoir reçu des marchandises volées. Illégalités Le juge J.-C. Langlois a condamné hier V. Lefebvre, épicier, 6500 blvd Monk, à une amende de $50 pour avoir vendu des oeufs à un prix prohibitif et Albert Sauvé, directeur de Miller Awning, 911 Notre-Dame ouest, à une amende de $25 pour avoir haussé le taux de son stock d'entreposage.

Le juge E. Guérin a condamné Joseph Charlebois, de chez Wilson Frères, 2537 Notre-Dame est, à une amende de $50 pour avoir défoncé le maximum sur la vente du coke.

La plus forte amende de la journée a été imposée par le juge J.-C. Langlois à la firme T. Beauregard et Cie, 7905 Saint-Denis. Cette maison paiera $75 pour avoir accorde un crédit illégal sur des marchandises vendues.

Morts subites J. Janofsky, 80 ans, 5479, Hutchison, est mort subitement hier à la gare Windsor où il attendait son train.

Jean Gagnon, 68 ans, 5312, chemin de la Côte-St-Paul, est mort subitement hier, à son domicile.

Georges Mandeville, 3 mois, 1210, Delcourt, est mort subitement, hier, chez ses parents.

Le coroner du district, Me Richard-L. Duckett, a rendu un verdict de mort naturelle dans le cas d'Arthur Houle, 65 ans, 349, boulevard des Prairies, et de Mme Rachel Charat, 62 ans, de Huntindgdon, décédés subitement.

Mort accidentelle Le coroner a également rendu un verdiet de mort accidentelle dans le cas de Mme Célina Brosseau, 66 ans, 5530, 11ème avenue, Rosemont, morte à l'Hôtel-Dieu des suites de blessures qu'elle s'était infligées le 20 mars, en tombant sur le trottoir.

Grièvement blessé Jean-Yves Bacon, 3 ans, rue des Voltigeurs, est hospitalisé à Ste-Justine, à la suite des blessures que lui infligeait hier un camion conduit par M. Alfred Pinelle, 3340, boul. La Salle, Verdun. L'accident s'est produit rue Notre-Dame, près Maisonneuve. L'enfant souffre probablement d'une fracture du crâne et de multiples érosions au visage.

Tombé du toit Wilfrid Larose, 9 ans, 1705, Panet, s'est infligé un traumatisme du cou. hier, en tombant du toit d'un entrepôt de bois et de charbon. Affaire d'alambic Le procès des frères Charles et Camille Deur, Léon et Sylvain Fournerie et Amédée Roby, accusés de conspiration pour frauder, le fise fédéral de $100,000, en exploitant un alambic à Lacoste, dans la région du Nominingue, en 1942, se continue, devant le juge en chef Perrault, des Sessions de la Paix, après un ajournement de deux semaines. La défense produit ses té moins aujourdhui

Acquitté Les Trois-Rivières, 14 - Le juge F.-X. Lacoursière a acquitté Jean Cyr, accusé d'avoir causé des lésions corporelles, entrainant la mort de Mme Edmond Pothier, le 29 juillet 1942.

Voies de fait Christie Angelis, restaurateur, rue Windsor, a été trouvé coupable hier de voies de fait sur la personne de P. Rath, photographe ambulant, par le juge C.-E. Guérin, en Cour des sessions de la paix.

Pelle et cheval Le juge René Théberge entendra le 30 avril la cause de Noël Janvier, fils, de la Côte de Liesse, à Dorval, accusé par la Société protectrice des animaux d'avoir frappé son cheval avec une pelle, le 6 mars.

#montreal#vol a main armée#armed robbery#armed robbers#ration tickets#wartime rationing#black market#sentenced to the penitentiary#st vincent de paul penitentiary#tragic death#accidental death#theft#animal cruelty#price control#fines and costs#canada during world war 2#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada

0 notes

Text

A Masterlist of Underused French Names

So as a French person, I grew a little bit tired of seeing the same old French names over and over again. So under the cut is a list of 260 (185 first names and 105 surnames) underused French names, based on my experience, with the bolded ones being my favorites! And now don’t get me wrong, many of those names are not strictly French, and are in other languages too. But just know they are used in French too, so they can be used for your French character if needed. And there are obviously a lot of other names you can go for!

Female Names

Agathe

Alexandrine

Amélie

Andréa

Andréanne

Angélique

Anne

Apolline

Ariane / Arianne

Audrey

Brigitte

Cadence

Camille

Cécile

Céleste

Céline

Chantal / Chantale

Charlotte

Chenelle

Christelle

Christiane

Christine

Claire

Clara

Claudie

Clémence

Coralie

Darcie

Delphine

Desirée

Dianne

Élaine / Élène / Hélène / probably a lot of other variations

Éléonore

Éloïse

Émilie

Estelle

Èvelyn

Félicia

France

Geneviève

Giselle

Isabelle

Jacinthe

Jacqueline

Jeanie

Joanne

Joceline

Joséphine

Julie

Juliette

Laure

Laurie

Lavinia

Léa

Liliane

Linette

Loraine

Madeleine

Maia / Maya

Mallory

Margaux

Margerite

Marianne

Marjolaine

Marjorie

Mathilde

Maude

Mélanie

Mélodie

Mélusine

Myriam

Nancy

Nathalie

Noémie

Ophélie

Rachel / Rachelle

Rosalie

Rosemarie

Roxane / Roxanne

Solange

Stéphanie

Susanne / Suzanne

Thérèse

Valérie

Véronique

Violette

Virginie

Viviane

Male Names

Adrien

Alain

Antoine

Arnaud

Baptiste

Benjamin

Benoit

Bernard

Bruno

Charles

Christian

Christophe

Clovis

Colin

Damien

David

Didier

Dilan

Edmond

Edouard

Eliott

Émile

Ernest

Étienne

Fabrice

Félix

François

Gaspard

Gaston

Gauthier

Geoffrey / Geoffroy

Grégoire

Guillaume

Henri

Hubert

Ivan / Yvan

Jacques

Jérémie / Jérémy

Jérôme

Joseph

Jules

Karel

Laurent

Léo

Léon

Léonard

Lionel

Luc

Marc

Martin

Mathieu / Matthieu

Maurice

Merlin

Nathanaël

Nicholas / Nicolas

Olivier

Paul

Philip / Philippe

Pierre

Quentin

Raymond

Rémi / Rémy

Richard

Robert

Roland

Romain

Sébastien

Simon

Sylvain

Thierry

Thomas

Tristan

Victor

Vincent

Xavier

Unisex Names

Carol (male) / Carole (female)

Claude

Daniel (male) / Danielle (female)

Denis (male) / Denise (female)

Dominic (male) / Dominique (female)

Eugène (male) / Eugénie (female)

Fabien (male) / Fabienne (female)

Frédéric (male) / Frédérique (female)

Jasmin (male) / Jasmine (female)

Jean (male) / Jeane (female)

Joël (male) / Joëlle (female)

Jordan (male) / Jordane (female)

Justin (male) / Justine (female)

Louis (male) / Louise (female)

Lucien (male) / Lucienne (female)

Marcel (male) / Marcelle (female)

Michel (male) / Michelle (female)

Noël (male) / Noëlle (female)

Pascal (male) / Pascale (female)

Patrice

Samuel (male) / Samuelle (female)

Valentin (male) / Valentine (female)

Surnames

Adam

Allaire

Allard

Archambault

Beauchêne

Beaulieu

Beaumont

Bélanger

Béranger

Bernard

Bertrand

Blanchard

Blanchet

Boivin

Bouchard

Boucher

Brisbois

Brodeur

Bureau

Caron

Charbonneau

Cloutier

Comtois

Côté

Courtemanche

Cousineau

Couture

Delacroix

Desautels

Deschamps

Descôteaux

Desjardins

Desrochers

Desrosiers

Duboit

Duchamps

Dufort

Dufour

Duval

Fabron

Faucher

Faucheux

Favreau

Félix

Fontaine

Fortier

Fournier

Gagné

Gagnon

Girard

Giroux

Gosselin

Granger

Guérin

Hébert

Jacques

Labelle

Lachance

Lambert

Langlois

Lapointe

Laurent

Lavigne

Lavoie

Lebeau

Leblanc

Leclair

Leclerc

Lécuyer

Legrand

Lemair

Lemieux

Lévesque

Maçon

Marchand

Martel

Martin

Mathieu

Mercier

Michaud

Moreau

Morel

Paquet

Parent

Patenaude

Pelletier

Perrault / Perreault

Petit

Plamondon

Plourde

Poirier

Poulin

Richard

Richelieu

Robert

Rousseau

Roux

Samson

St-Martin

St-Pierre

Taillefer

Thibault

Thomas

Tremblay

Villeneuve

#masterlist#french masterlist#name help#rph#name masterlist#i needed to do this#this feels so great#also that moment my name is not one of my favorites oops

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Gnostic Boardwalk

Canonical stature is a fragile and contingent thing, which is why powerful institutions seek to shore up the various canons of art with rankings and plaudits. We’ll play along by asserting that one of our favorite “B” movies was originally screened by Henri Langlois at the Cinematheque française with Georges Franju in attendance. Night Tide (1961) was an unlikely contender for this particular honor—shot guerrilla style on an estimated $35,000 budget, and intended, by its distributors at least, for a wider, less demanding audience seeking mostly air-conditioned escapism.

With its hinky cast—nonfictional witch, Marjorie Cameron; erstwhile muse to surrealist filmmaker Jean Cocteau, the undersung Babette who usually appears en travesti; and lecherous, booze-addled, fresh-faced Hollywood castoff Dennis Hopper—Night Tide invades the drive-in. A tarot reading at the film’s heart gives Marjorie Eaton her time to shine, traipsing into nickel-and-dime divination from her former life as a painter of Navajo religious ceremonies. Linda Lawson might have issued from an etching by Odilon Redon, with her raven locks and spiritual eyes, our resident sideshow mermaid. Not surprisingly and despite such gentle segues, the film itself traveled a rocky road from festivals to paying venues.

Night Tide had spent three years languishing in the can when distributor Roger Corman smuggled the unlikely masterwork into public consciousness, another of his now legendary mitzvahs to art. And the sleazy-sounding double bills that resulted also unleashed an aberrant wonder: the movie’s compact leading man, a force previously held captive by the studio system—looking, here, like some homunculus refugee from the Fifties USA. Dennis Hopper, in his first starring role, would later recall that it represented his first "aesthetic impact" on film since his earlier appearances in more mainstream productions such as Rebel Without a Cause and Giant had denied him meaningful outlets for collaboration.

It’s the presence of its featured players—certainly not their star power—that lends the film its haunting and enduring legacy, and elevates the term “cult classic” to its rightful place in the pantheon of cinema. But we argue that Night Tide remains outside these exclusive parameters—upholding an elsewhere-ness that defies commercial, if not strictly canonical, logic. Curtis Harrington’s first feature film escapes taxonomy, typology or genre—gets away—fueling itself on acts of solidarity instead. If Hopper contributes his dreamy aura, then Corman rescues the seemingly doomed project by re-negotiating the terms of a defaulted loan to the film lab company that was preventing the film’s initial release. His generous risk birthed a movie monument that would add Harrington’s name to a growing collection of talent midwifed by the visionary schlockmeister responsible for nursing the auteurs of post-war American cinema. And here we enter a production history as gossamery as Night Tide itself.

Unlike his counterparts entrenched within the studio system, Harrington was an artist -- i.e. a Hollywood anachronism, with aristocratic graces and a viewfinder trained on the unseen. We see Harrington as Georges Méliès reborn with a queer eye, casting precisely the same showman’s metaphysics that spawned cinema onto nature. By the time moving pictures were invented, artists were moving away from a bloodless representational ethos and excavating more primordial sources for inspiration. The early stirrings of what surrealist impresario André Breton would later proclaim: “Beauty will be CONVULSIVE or it will not be at all.”

Harrington owned a pair of Judy Garland’s emerald slippers, and according to horror queen/cult icon Barbara Steele, also amassed an eclectic array of human specimens: “Marlene Dietrich, Gore Vidal, Russian alchemists, holistic healers from Normandy, witches from Wales, mimes from Paris, directors from everywhere, writers from everywhere and beautiful men from everywhere.” On a hastily constructed Malibu boardwalk, Hopper would be in his milieu among the eccentric denizens of California’s artistic underground—most notably, Harrington himself, a feral Victorian mountebank of a director who slept among mummified bats, practiced Satanic rites, and hosted elaborate and squalid dinner parties. One could almost picture the mostly television director in his twilight years as Roman Castavet of Rosemary’s Baby; a spellbinding raconteur with a carny’s flair for embellishment and enticement. Enthralled by the dark gnosticism of Edgar Allan Poe that had started when the aspiring 16-year-old auteur mounted a nine-minute long production of The Fall of the House of Usher (1942), Harrington would embark on a checkered film career that combined his occult passions with the quotidian demands of securing steady employment. Night Tide, a humble matinee feature whose esoteric underpinnings would spawn subsequent generations of admirers, united the competing forces of art and commerce that Harrington would struggle with throughout his career. Like Méliès, Harrington pointed his kinetic device towards the more preternatural aspects of early motion pictures to seek out the ‘divine spark’ that Gnostics attribute to transcendence, and the necessary element to achieve that immortal leap into the unknown. What hidden meanings and unspeakable acts Poe had seized upon in his writing were brought infernally to life with a mechanical sleight-of-hand. It was finally time for crepuscular light, beamed through silver salts to illuminate otherworldly and other-thinking subjects.

By the time Harrington had embarked on his feature film debut, a more muscular celluloid mythology based on America’s proven exceptionalism was in full force, taking on a brutalist monotone cast in keeping with the steely-eyed, square-jawed men at the helm of a nascent super-power, consigning its more feminine preoccupations to the dusty vaults where celluloid is devoured by its own nitrate. Harrington would resurrect the convulsive aspects of his chosen vocation and embed them deep within the monochrome canvas he’d been allotted for his first venture into feature filmmaking, and combine them with the more rational aspects of so-called realism. In the romantic re-telling of a familiar myth, Harrington was remaining true to gnostic roots and the distinctly poetic language used to express its cosmological features.

In Night Tide, Harrington would map the metaphysical terrain that held up Usher’s cursed edifice as a blueprint for his own work that similarly explored the intertwined duality of the natural and the supernatural. The visible cracks that reveal a fatal structural weakness and a loss of sanity in both Roderick Usher and his doomed estate are evident in Night Tide’s conflicted heroine compelled to choose between her own foretold death underwater, or a worse fate for those who fall in love with her earthly human form.

A young sailor (Dennis Hopper) strolling the boardwalks of Malibu while on shore leave offers the viewer an opening glimpse into the film’s metaphysical wormhole, and a not so subtle hint of the director’s queer eye, stalking his virginal prey in the viewfinder. A beachfront entertainment venue is, after all, where one would casually encounter soothsayers and murderers, sea witches and perverts, as the guileless Johnny does, seemingly oblivious to the surrealist elements of his surroundings as he makes his way on land.

Harrington’s carnival-themed underworld is both imaginatively and convincingly presented as a quaint slice of post-war America, effortlessly dovetailing with his intended drive-in audience’s expectations of grind house with a dash of glamor—not to mention his own avant-garde leanings, which remain firmly intact despite Night Tide’s outwardly conventional construction and narrative.

Harrington is able to present this juxtaposition of kitsch Americana and the queer arcana of his occult fascinations. Indeed, Night Tide’s lamb-to-the-slaughter protagonist could have wandered off the set of Fireworks, Kenneth Anger’s 1947 homoerotic short film about a 17-year-old’s sadomasochistic fantasies involving gang rape by leathernecks.

Anger would later sum up his earliest existing film as “A dissatisfied dreamer awakes, goes out in the night seeking a ‘light’ and is drawn through the needle’s eye. A dream of a dream, he returns to bed less empty than before.” Harrington (a frequent collaborator of Anger in his youth) seems to have re-worked Fireworks, or at least its underlying queer aesthetic into a commercially viable feature film that explores his own life long occult fascinations.

Both Anger and his former protégé would view the invocation of evil as a necessary step towards the attainment of a higher level of consciousness. Harrington coaxed a more familiar story from the myths and archetypes that informed his unworldly views for a wider audience; a move that would be later interpreted by sundry cohorts as selling out. Still, Night Tide shares a thematic kinship with Anger’s more obtusely artistic output as acknowledged by the surviving occultist, who confirmed this unholy covenant at Harrington’s funeral by kissing his dead friend on the lips as he laid in his open coffin.

The hokey innocence of Dennis Hopper as Johnny Drake in his tight, white sailor suit casts a homoerotic hue on the impulses that compel him to navigate a treacherous dreamscape to satisfy a carnal longing, just as Anger’s dissatisfied dreamer obeys the implicit commands of an unspeakable other to seek out forbidden pleasures.

As he makes his way on land, the solitary, adventure-seeking Johnny will be lured into a waiting photo booth, his features slightly menacing behind its flimsy curtain, and brightly smiling a second later as the flash illuminates them. Johnny has entered a realm where intersecting worlds collide, delineating light from shadow, consciousness from unconsciousness. The young sailor’s maiden voyage into the uncharted waters of his subconscious is made evident in the contrasting interplay captured by the camera, where predator and prey overlap in darkness. Here, too, we get a prescient preview of the deranged psychopath Hopper would subsequently personify in later roles, most significantly as the oxygen deprived Frank of Blue Velvet—a man who seems to be drowning out of water. But here, Hopper convincingly (and touchingly) portrays a wide-eyed naïf, still unsteady on his sea legs as he negotiates dry land.

As a variation of Anger’s lucid dreamer in Fireworks (and later Jeffrey of Blue Velvet) Johnny will have abandoned himself quite literally (as his departing shadow on a carnival pavilion suggests, before its host blithely follows) to his own suppressed sexual urges; a force that eventually compels him towards denouement.

Moments later, inside the Blue Grotto where a flute-led jazz combo is in progress, Johnny spots a beautiful young woman (Linda Lawson) seated directly across from him. Her restrained and almost involuntary physical response to the music mimic his own, offering the first indication of a gender 'other' residing in Johnny; an entombed apparition cleaved from the sub-conscious and projected into his line of vision. Roderick and Madeline Usher loom large in Harrington’s screenplay and Usher’s trans themes lurk invisibly in the subtext. Harrington is arguably heir apparent to Poe’s vacated throne, pursuing similar clue-laden paths and exploring the dual nature of human and the primordial creature just beneath the surface poised to devour its host.

The near literal strains of seductive Pan pipes buoyed by the ‘voodoo’ percussion sets the stage for Harrington’s reworking of the ancient legend of sea-based seductresses and the sailors they lure to their graves.

Marjorie Cameron (or ‘Cameron’ as she is referred to in the opening credits) makes a startling entrance into The Blue Grotto as an elder of a lost tribe of mermaids seeking the return of an errant ‘mermaid’ to her rightful place in the sea. Cameron, a controversial fixture in L.A.’s bohemian circles and one-time Scarlet Women in the mold of Aleister Crowley’s profane muses, would later appear in Anger’s The Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome, and as the subject of Harrington’s short documentary The Wormwood Star (1956).

The inclusion of a bonafide witch, along with a host of less apparent occult/avant-garde figures, is further evidence of Night Tide’s true aspirations and its filmmaker’s subversive intent to sneak an art-house film into the drive-in, and introduce its audiences to the heretical doctrine that had spawned a new generation of occult visionaries influenced by Edgar Allan Poe. Decades later, David Lynch would carry that proverbial torch, further illuminating the writhing, creature-infested realm underlying innocence.

Johnny approaches the young woman who rebuffs his attempts at conversation, seemingly entranced by the music, but allows him to sit, anyway. Soon they are startled by the presence of a striking middle-aged woman (‘Cameron’) who speaks to Johnny’s companion Mora in a strange tongue. Mora insists that she has never met the woman before, nor understands her, but makes a fearful dash from the club as Johnny follows her, eventually gaining her trust and an invitation the following day for breakfast.

Mora lives in a garret atop the carousal pavilion at the boardwalk carnival where she works in one of the side show attractions as a “mermaid.” Arriving early for their arranged breakfast, her eager suitor strikes up a conversation with the man who runs the Merry-Go-Round with his granddaughter, Ellen (Luanna Anders). Their trepidation at the prospecting Johnny becoming intimately acquainted with their beautiful tenant is apparent to all except Johnny himself, who is even more oblivious to Ellen’s wholesome and less striking charms. Even her name evokes the flat earth, soul-crushing sensibilities of home and hearth. Ellen Sands is earthbound Virgo eclipsed by an ascendent Pisces. (Anders would have to subordinate her own sex appeal to play this mostly thankless “good girl” role. She would be unrecognizable a few years later as a more brazenly erotic presence in Easy Rider, helping to define the Vietnam war counterculture era.)