#dene athabascan

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

3 Flavors of Perfective Verbs in Three Athabascan Languages

(Sources listed at the bottom)

Athabascan languages (a sub-group of Na-Dene languages) feature verbs with many prefixes, which mark the subject, direct object, as well as adverbial elements which help the root define the action of the verb, and affixes which help identify tense and aspect, among others (as you might imagine, Athabascan verbs can get rather long). Among the Athabascan languages are Hupa, from the coastal Athabascan sub-group in Northern California, and Navajo, spoken in Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico. While both are Athabascan, they are not particularly close relatives, Hupa being in the Coastal subgroup, and Navajo being in the Southern subgroup. However, they share an interesting feature; different verbs form their perfective forms (NOT the same thing as a perfect) with one of a set of prefixes. These prefixes track to a certain nuance in sense. I will quote Pliny Earle Goddard's description of this from Hupa:

There are three simple sounds which by their presence indicate whether the act is viewed as beginnning, ending, or progressing. These sounds are not found in all forms of the same verb, but only in those tenses which refer to the act of state as one and definite.... In many cases the nature of the prefix requires the act to be thought of as beginning, ending, or progressing. The sound which is of most frequent occurrence is /w/. It stands at the beginning of a syllable, usually the one immediately preceding the root. The remainder of this syllable contains the subjective personal elements. Its initiatory force can be seen in the verbs /wiñyaʟ/ COME ON and /wiñxa/ WATER LIES like the ocean, which has no beginning... In a precisely parallel manner, /n/ occurs as the initial of the inflected syllable under circumstances which point to the completion of the act. With /wiñyaʟ/ (above) compare /niñyai/ IT ARRIVED... Without the same exact parallelism of forms which obtains with the two mentioned above, a large number of verbs have /s/ as the characteristic of the inflected syllable of the definite tenses. Most of these verbs clearly contain the idea of progression, or are used of acts which require considerable time for their accomplishment. The distributive prefix /te-/ is always followed by /s/, never by either of the other signs, and some of the prefixes listed above are used with /s/ with a distinction in meaning: for example /xawiñan/ he took a stone out of a hole (but /xaïsyai/ he came up a hill)… In one of the Eel river dialects the bringing home of a deer is narrated as follows: /yīgiñgīn/ he started carrying; /yītesgīn/ he carried along; /yīningīn/ he arrived carrying. here we have /g/ (corresponding to Hupa /w/), /s/, and /n/ used with the same stem, expressing the exact shades one would expect in Hupa.

In other words, perfectives in Hupa treat an action as either the start of a situation (with /w/), the process of a situation (with /s/) or the end of a situation (with /n/). Interestingly, there seems to be some parallel prefixes in Navajo with a similar meaning. Pulling from my notes on The Navajo Language (a book I no longer have access to, unfortunately), there are yi-, si-, and ni- perfectives in Navajo. Yi perfectives are used in the simple completion of the action of the verb, si-perfectives are used when the action creates a stative or durative state (for example “I set it up”), and ni-perfectives are terminal in effect, such as in arriving, stopping, finishing, etc. These prefixes also appear in some Navajo imperfective forms as well, adding the simple, final, or setting-up nuance to an imperfective action. These similarities, especially in the Hupa /s/ and /n/ with the Navajo /si/ and /ni/, show an interesting commonality.

Before I finish, I just remembered that I have another resource on an Athabascan language, namely of Mattole, another coastal Athabascan language. I have yet to devote much time to Mattole, and this document is a fairly brief overview, but it also describes the many prefixes of Mattole, and among the classes of prefixes are these (emphasis mine):

Time-aspect prefixes These express whether the action or situation lasts on (si), is going on all the time or is concerned with the result (ɣi), is instantaneous (ni), occurs in the future (diɣi), or involves a permission (oo).

Again, we see a difference in meaning, but there is noticeable overlap

Sources:

The Navajo Language: A Grammar and Colloquial Dictionary - Robert Young, William Morgan; 1987

Hupa - Entry in the Handbook of American Indian Languages, Pliny Earle Goddard; 1911

A Survey of the Athabaskan Language Mattole - Dick Grune; 2015

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Climate change makes farming easier in Alaska. Indigenous growers hope to lead the way

Read the full story from NPR. Growing up in rural Alaska, Eva Dawn Burk recalls hunting, trapping and going to fish camp every summer, gathering traditional foods with her family. Burk is Alaska Native, Dene’ and Lower Tanana Athabascan. She grew up in the small villages of Nenana and Manley Hot Springs along the Tanana River in Interior Alaska, where her family and neighbors relied on the land…

0 notes

Link

The word is Tinaaq (De-NAH-q). It replaces the current word, Itqaliq, which can be interpreted as offensive.

The elders came up with the new word during a two-week language program, called Ilisaqativut, in northwestern Alaska.

The old word, Itqaliq, is "not a very nice word," said Marjorie Tahbone, an Iñupiat woman from Nome, Alaska, who took part in the language program with her husband, Dewey Putyuk Hoffman, and their newborn daughter.

The word Itqaliq is from a time when Indigenous nations were warring over lands to hunt and fish, she said.

"It can mean lice-ridden people. It can mean people with no asshole. It was definitely a term that wasn't meant to be friendly," said Thabone.

"It's kind of outdated because now we live in harmony. We unite, we collaborate, we make babies, and so it's time for a new word."

Hoffman is Koyukon Athabascan from the interior. Tahbone said that when he introduces himself using the old Iñupiaq word for Dene Athabascan people, laughter often ensues.

"Everybody would giggle ... because we all kind of know what [Itqaliq] means," she said.

Hoffman joked about wanting a better Iñupiat word to describe himself.

Elders and some youth at the language camp obliged. They gathered and "Iñupia-tized" the word "Dena," or people of the interior, said Tahbone.

"Now he could just say ... 'I am Tinaaq.' There's no giggling. There's no inside joke about what we used to call Athabascan people, and I'm happy," she said.

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let’s Learn Navajo - Common Phrases & Farewell

Common Phrases – Greeting & Farewell

Yáʼátʼééh abíní. Good morning.

Aooʼ, yáʼátʼééh. Yes, hello. (a common response to Yáʼátʼééh)

Háágóóshąʼ? Where (are you going) to?

Haʼátʼíísh baa naniná? What are you doing?

Hazhóʼó naniná? Be careful; be good.

Ádaa áhólyą́. Take care of yourself.

Yiską́ągo índa. See you tomorrow (tomorrow, and then)

Shí kʼad ; Shí kʼad dooleeł. I’m leaving now.

Pronunciation rules can be found here (Simple Nouns Pt. 1), (Simple Nouns Pt. 2) and here (Simple Nouns Pt. 3).

#Navajo Language#navajo#ndn#language learning#learning#linguistics#indigenous languages#greetings#farewell#native american#native#native american languages#langblr#langblog#na-dene#dene#Athabascan#athapascan#U.S.#southwest langauges#southwest#arizona#languages of arizona#southern athabaskan

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Athabascan Council in Native American Nations, Vol. 2, for Shadowrun (1st Edition)

A note on spelling: NAN Vol. 2 spells it as above, though the map at the back spells it as “Athabaskan”, and future Shadowrun editions use the “k” spelling. There are two other spelling variants, at least for the eponymous language family, exchanging the “b” with a “p” to make Athapascan and Athapaskan.

Notice that splotch in the American Southwest? That’s the Navajo Nation, as discussed here.

And ironically, the Athabascan tribes (Koyukon, Yellowknife, Chilcotin, Dené) make up a minority (40%) of the population, with the non-Athabascan Aleut and Inuit making up the majority.

Let’s be honest: Athabascan Council is boring.

If the NAN were the Seattle Metroplex, Athabasca would be Snohomish: way up north, beautiful land, but no one goes there.

As such I don’t have a lot to say about it, so instead, I’ve decided to take some of the plot hooks peppering this section and spruce them up into Sprawl Sites style mini-adventures. Roll a d6...

Six Runs in the Athabascan Council

1. Kraken Attacken’

The Plot Hook: “What about that ferry that got taken down by a fragging kraken two years back?”

The Mr. Johnson: Rich eccentric old man, Ahab Ishmael, hires the team to recover valuables from a relative who was on that kraken-sunken ferry. He offers to fully fund an expedition, provided he can come with.

The Twist: Ahab is really hunting for the kraken, and of course, being shadowrunners, they get attacked by one.

2. Snow Moose Hunt

The Plot Hook: “You know what a snow moose is? I’ll put it in words of one syllable: twice as tall as a man, big as a house, mean as a cage of rats.”

The Mr. Johnson: Another rich eccentric old man, Pequod Starbuck, wants some shadowrunners to poach a snow moose so he can mount its head and giant antlers in his office.

The Twist: The team starts tracking a snow moose, only to find a group of Dené doing the same – except the tribe wants it for its meat and hide to help survive the winter. ETHICAL CONFLICT!

3. Biogene back again

The Plot Hook: “In 2011 Biogene Laboratories Inc. marketed the first efficient oil-leeching bacteria and the Tar Sands were once more an economic boon.”

The Mr. Johnson: A standard mirror-shades black-suited ultra-corper, hiring the runners to retrieve a Biogene bacterial sample from the Athabascan Tar Sands.

The Twist: Biogene was the company behind the run against Aztechnology in DNA/DOA, and so it was Aztechnology that has hired the team for a bit of payback.

4. Free Willies

The Plot Hook: “You’ve heard about fish farming, right? Well, how about whale farming?”

The Mr. Johnson: The team is hired by “Deerhunter”, who is an Athabaskan native looking to arrange a meet with Hollis Baynes, CEO of Farm-the-Sea, Inc., who is in Seattle to pitch a whale farming project to Salish-Shidhe Council representatives.

The Twist: When it becomes apparent that “Deerhunter” aims to slaughter Baynes in a toxic ritual, the team must rush to Edmonton to save their rep.

5. Let’s Start a War!

The Plot Hook: “The Athabascan Council continues to insist, according to its 2035 decision, that the UCAS remove all DEW sensor stations from Athabascan lands.”

The Mr. Johnson: Dick Herman, a grizzled, military lumberjack type, needs a decker to crash a “cold” network, as in, not connected to the Matrix, but also, it’s the Distant Early Warning (DEW) radar station network. A decker and friends are to meet a contact in the town of Deadhorse, Athabasca, who will help them infiltration the station on Oliktok Point.

The Twist: Clues from their Johnson, and their contact, indicate they have UCAS military ties, and some investigation from the locals in Prudhoe Bay reveal that crashing the DEW network could be viewed as a provocation that could lead to war.

6. Snow-Snow-Snow Gangs

The Plot Hook: “The go-gangs adapt to the conditions, of course. In the winter, they don’t use bikes, they use snowmobiles and customized Hovercats, with weapons fixed on hardpoints or firmpoints.”

No Mr. Johnson or Twist here – just the runners getting attacked by a snowmobile gang.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

radical gardener vol. 7: land recognition

This is Dena’ina ełnena.

In recent years, more and more events and rally open with a land recognition. A land recognition, or territory acknowledgement, is a statement that recognizes the indigenous people who have been dispossessed of their land by settler-colonial nations.

In Alaska, 1/7 of the population is Alaska Native or Native American. Native people and culture are integrated into the general population. It is crucial that indigenous peoples’ claim to the land is recognized, as their rights to land and livelihood has been degraded for centuries.

Prior to colonization, indigenous people did not “own” the land. Property was not a concept. The land did not belong to the people – people belonged to the land. People stewarded the land, and its bounty was shared by all.

Land recognition is one of the first steps of the larger process of decolonization. But it is not enough to simply state who lived on the land first; land recognitions must also recognize the broken treaties, the fact that indigenous people were dispossessed and evicted from their land, and that the settler-colonial system continues to oppress indigenous people to this day, by depriving them of their health and wellbeing, culture and traditions.

Settlers must recognize that they are guests on indigenous land, and that they are not entitled to its governance.

Scope of Project

In this volume, there are two maps.

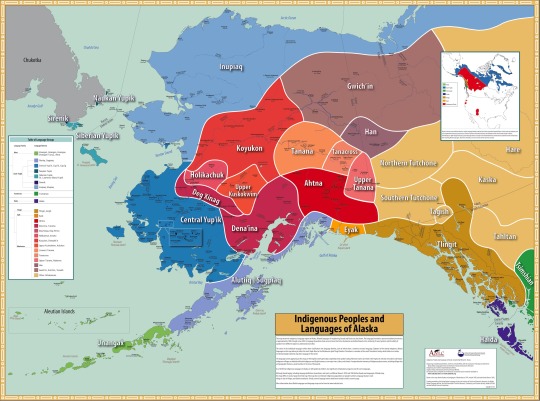

The first is the Indigenous Peoples and Languages of Alaska, published by the Alaska Native Language Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. This map is so familiar to me, as it is posted at all levels of educational institutions throughout Alaska. There are high resolutions available online, where you can see the indigenous place names for most major communities within Alaska. It is important to note that the delineation between regions is not a strict border. I was inspired by the ANLC map to create my own version, featuring place names within southcentral Alaska, which is the second map shown.

Southcentral Alaska is home to more than half of Alaska’s population, and is the most densely populated region of Alaska. This map features the Anchorage Bowl and the southern half of the Matanuska-Susitna River valleys. It is within the traditional territory of the Dena’ina people, and Ahtna people have also lived in the area, and they frequently intermingled. The Dena’ina and the Ahtna people are Dene (Athabascan) people, and are related to other Dene peoples within Alaska, Canada, along the Pacific coast, as well as the Navajo and Apache nations.

Shem Pete’s Alaska: The Territory of the Upper Inlet Dena’ina, James Kari’s seminal work about Dene place names, was invaluable in the creation of my map. The man interviewed by James Kari, Shem Pete (1896-1989), was an intrepid traveler who had a vast repository of knowledge about Dena’ina place names. In his work, there is a wealth of stories and legends. For Alaskans, it is a must-read.

Where there is only one place name present, it is in Dena’ina only; where there are two places names, it is in both Dena’ina and Ahtna. I decided to insert recorded Ahtna place names when they were present, to recognize the fact that this is a traditionally bilingual region. Dene people in this area were versed in both languages as they traveled, traded, and intermarried, and in the later colonial period, Native people here frequently spoke four or more languages: Dena’ina, Ahtna, Russian, and English.

I am someone who is descended from settlers. The purpose of this volume is to convey and amplify what I have learned from my Native friends and colleagues to the public at large. My goal is that settlers in Alaska will become more comfortable using longstanding indigenous places names, instead of marking familiar geographical features with colonial names. Captain Cook does not need the attention that he receives.

I encourage my readers to engage with the indigenous peoples of the land that they are living on.

157 notes

·

View notes