#death in dessau

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

oury jalloh, death in dessau 2005

*

youtube

die bettwurst, rosa von praunheim 1971

#oury jalloh#death in dessau#2005#dessau#bauhaus#material#buw#jva#696#about photography#the lost tapes#landmann#die bettwurst#rosa von praunheim#1971#uri geller#kiesewetter#zschäpe#nsu#angst essen seele auf

1 note

·

View note

Text

Rumbeke, 31 October 1917

On 28 October 1917, Erwin Böhme visited Oswald Boelcke's parents in honour of his death a year earlier. Afterwards he was able to go to Hamburg to visit Annamarie. During this visit they became engaged.

Dearest Gerhard! Now I have a bride! You, my dear brother, shall know such tales at once. Today at noon I returned from my trip to Dessau and spent half a day in Hamburg. I arrived at noon, and at midnight my train left for the front - in these short hours I fetched my happiness from heaven. It still has to remain a secret until Annamarie's parents have agreed. Because, of course, it is Annamarie from the Hubertusmühle, whom I have told you about so often. Since we met at the famous "emergency landing" in May last year, we have been in correspondence. It was love at first sight, for me and, as she has now confessed to me, for her too. But neither dared to open up, each was always too worried not to betray their heart in the letters - she out of girlish shyness, I in my reserved way. At the same time, we were both tormented by the uncertainty of what it looked like in the other's hearts. Now you understand the heavy mood that was upon me that summer. I finally had to make things clear. Annamarie is quite the girl that suits me: a genuinely feminine being, fresh and natural, without any trace of the kind of modern man-woman I detest, and yet clever, brave and with the strong will of a man. I also find her very beautiful, with her lively dark eyes, from which kindness and loyalty shine and sometimes mischieve blossoms. Am I now a frivolous man? Without a secure position in life, without a definite plan for the near future, to chain another fate to mine! But I firmly count on the favour of the good spirits who always help the brave and strong. Boy, I wouldn't have believed that an old man, made serious and austere by life, could once again become so happy. Rejoice, Gerhard, with your old, rejuvenated brother!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blood Baptism in the Rites of Attis

“...[Attis’] worship is known to have comprised certain secret or mystic ceremonies, which probably aimed at bringing the worshipper, and especially the novice, into closer communication with his god. Our information as to the nature of these mysteries and the date of their celebration is unfortunately very scanty, but they seem to have included a sacramental meal and a baptism of blood. In the sacrament the novice became a partaker of the mysteries by eating out of a drum and drinking out of a cymbal, two instruments of music which figured prominently in the thrilling orchestra of Attis. The fast which accompanied the mourning for the dead god may perhaps have been designed to prepare the body of the communicant for the reception of the blessed sacrament by purging it of all that could defile by contact the sacred elements. In the baptism the devotee, crowned with gold and wreathed with fillets, descended into a pit, the mouth of which was covered with a wooden grating. A bull, adorned with garlands of flowers, its forehead glittering with gold leaf, was then driven on to the grating and there stabbed to death with a consecrated spear. Its hot reeking blood poured in torrents through the apertures, and was received with devout eagerness by the worshipper on every part of his person and garments, till he emerged from the pit, drenched, dripping, and scarlet from head to foot, to receive the homage, nay the adoration, of his fellows as one who had been born again to eternal life and had washed away his sins in the blood of the bull. For some time afterwards the fiction of a new birth was kept up by dieting him on milk like a new-born babe. The regeneration of the worshipper took place at the same time as the regeneration of his god, namely at the vernal equinox. At Rome the new birth and the remission of sins by the shedding of bull's blood appear to have been carried out above all at the sanctuary of the Phrygian goddess [Cybele] on the Vatican Hill, at or near the spot where the great basilica of St. Peter's now stands; for many inscriptions relating to the rites were found when the church was being enlarged in 1608 or 1609.” [1]

—J. G. Frazer, Adonis, Attis, Osiris, part 1 (The Golden Bough, vol. V, 1914, p. 274-275)

[1] Frazer's footnote: "Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum, vi. Nos. 497-504; H. Dessau, Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae, Nos. 4145, 4147-4151, 4153; Inscriptiones Graecae Siciliae et Italiae, ed. G. Kaibel (Berlin, 1890), p. 270, No. 1020; G. Zippel, op. cit. pp. 509 sq., 519 [*]; H. Hepding, Attis, pp. 83, 86-88, 176; Ch. Huelsen, Topographie der Stadt Rom im Alterthum, von. H. Jordan, i. 3 (Berlin, 1907), pp. 658 sq."

[*] Full citation: "Zippel, G., "Das Taurobolium," in Festschrift zum fünfzigjährigen Doctorjubiläum L. Friedlaender dargebracht von seinen schülern. Leipsic, 1895" (The Golden Bough, vol. XII: Bibliography and General Index, p. 143).

"Taurobolium, or Consecration of the Priests of Cybele under Antoninus Pius," by Bernhard Rode (c. 1780).

(Source: Bernhard Rode, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

#jg frazer#the golden bough#the golden bough vol v#adonis attis osiris#attis#blood rites#bulls#initiation#rebirth#baptism#vatican#cybele#st. peter's basilica

0 notes

Text

Johanna Charlotte of Anhalt-Dessau (6 April 1682 – 31 March 1750) was a princess of Anhalt-Dessau from the House of Ascania by birth and Margravine of Brandenburg-Schwedt by marriage. From 1729 until her death she was abbess of Herford Abbey.

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Victims of hate crimes and victim support groups presented Human Rights Watch with examples of cases in which the police at a crime scene had focused their questions on the victim rather than alleged perpetrator, had sought to discourage victims from filing complaints, or had failed to take basic investigative steps, all of which undermined confidence in the police.

Victims are sometimes reluctant to report hate crimes to the police for example because of negative prior experiences with the police in Germany or elsewhere.

...

Victim support groups and groups representing migrants and other minorities who are the target of violence told Human Rights Watch that victims of hate violence, particularly migrants, asylum-seekers and refugees, are sometimes reluctant to report incidents to police or file charges because they lack confidence that police will protect them or take their complaints seriously, or because they anticipate that the perpetrators are unlikely to be arrested or punished. [22]

Gautier, a 32 year-old man from Cameroon, who has lived in Berlin for over 8 years described to Human Rights Watch his interaction with police in October 2009 when he was attacked by 3 men, leaving him hospitalized for 5 days:

The first statement of the investigator was ‘why did you not call the ambulance, but the police?’ The second question was to ask for my ID. The third if they should call an ambulance. … . Only later they asked me a brief question on what happened. Two of the three men were arrested on the spot. [23]

The police later dropped the case because the three alleged perpetrators were Ukrainian nationals without registered addresses and could not be located after their release. [24]

Victim support organizations and a civil society representative told Human Rights Watch that victims are also sometimes reluctant to report crimes to the police because victims are concerned about reprisals or further conflict with the perpetrator. [25]"

"A motley crew of around 800 people has gathered at the train station to commemorate and protest the anniversary of one of Germany's most notorious deaths in custody: The presumed killing of Oury Jalloh, an asylum seeker from Sierra Leone who died in a Dessau police cell on January 7, 2005.

The protesters chant "no justice, no peace" and "Oury Jalloh, it was murder", among other slogans. Luisa Meier, who traveled to Dessau from Leipzig, says she joins the protest march every year.

"I believe the remembrance culture, keeping it up, is very important. The case is still unsolved, so I think it's important to keep doing it. There are also other cases like Mouhamed Dramé, who was killed by police. So it's a systemic problem -- police are a problem for people of color."

Dramé, two of whose relatives also joined the march, was a young Senegalese asylum seeker whose death made headlines across Germany since he died in August 2022. Last month, a German court found five police officers not guilty in the deadly shooting."

#murder tw#germany#hate crimes#human rights watch#there are so many examples in the video and i can't keep up#i am feeling sick

0 notes

Text

A man walking

[The Monk by Caspar David Friedrich (Staatliche Museen, Berlin)].

Acantilado publishes British tenor Ian Bostridge's obsessive study of one of the crowning works of German Romanticism, Franz Schubert's song cycle Winter Journey.

Franz Schubert (Vienna, 1797-1828) composed Winterreise (Winter Journey), a cycle of twenty-four lieder from poems by Wilhelm Müller (Dessau, 1794-1827), in two phases about ten months apart at the end of his short life. Müller, who had been a ducal librarian in his home town since 1820, was a poet well known to the composer, who had composed his first major song cycle (The Beautiful Miller) from another of his collections in 1823. It was just in 1823 that Müller published some poems in the journal Urania under the title of Wilhelm Müller's Travel Songs. The Winter Journey. In 12 lieder. The following year he published the twenty-four poems of the cycle in a book entitled Poems from the Papers Bequeathed by a Wandering Forest Bugler. Songs of life and love. We do not know at what point Schubert became acquainted with the first twelve poems, but from them he wrote a song cycle in February 1827. The Viennese publisher Tobias Haslinger published it in January 1828. By then, the composer had already discovered the complete collection, and in the autumn of the same year, 1827, he expanded his initial cycle into its final form. Haslinger thus published them on the last day of 1828, when Schubert had already been dead for six weeks and Müller, who would never hear these songs, for fifteen months.

Winterreise is a true fetish of Western culture and one of the most accessible and effective means of gaining first-hand knowledge and insight into the world of German Romanticism, which has had such an enormous influence on the shaping of our world, not only in the realm of culture, but also in the realm of society and politics. There are no excuses. The recordings of the cycle are well over a hundred and can be found by the dozens on any streaming or video platform. The texts are published in very affordable editions and can be accessed for free on the internet in many ways (be careful with the sources and translations, though).

[Schubert's ‘Winter Journey’. Anatomy of an obsession Ian Bostridge. Translation by Luis Gago. Acantilado, Barcelona, 2019. 385 pages. 24 euros]

The figure of the wanderer, the wanderer, the stranger, the outcast is an authentic cliché of German Romantic culture, with an extensive and intense trajectory throughout the 19th century. Despite its clear historical roots, linked to a very specific space and time, there are many elements in the Schubertian cycle that bring it closer to contemporary sensibility. To begin with, Schubert eliminated the definite article from his cycle: Die Winterreise (The Winter Journey, which was the title of Müller's collection of poems) became Winterreise (Winter Journey) as such, and in this simple abbreviation the composer not only appropriates the poetic source material in a radical way, but makes it more abstract and universal. Something extremely modern, just as modern is the absence of a real narrative plot: there is much that is Beckettian in a work that presents reality as we really perceive it, in a fragmented way. The theme is of course universal and eternal. Schubert's walking man is shrouded in the aura of mystery that characterises the heroes of a Lord Byron, tragic heroes of whose origin we know little, but he is also the individual who lives his love disillusionment with an existential anguish of which literature, philosophy and art of the last century is plagued. The man who walks is also the man who suffers. Through lack of love.

Any minimally attentive reading of the work can discover these keys and many others: loneliness, pain, cold (not only physical), nostalgia, despair, death, madness… Tenor Ian Bostridge (London, 1964) has gone further. Obsessed with the work since he first approached it as a child, and having performed it countless times over three decades halfway around the world, Bostridge has written an extraordinary book about it, a book-book that goes beyond any conventional approach to the cycle. Without disdaining musical analysis, the London tenor looks behind every word, delves into every mysterious or ambiguous sign, scalpel-deep into every trace of life to give it its proper context, a broad contextualisation, which refers to politics, society, tradition, science and of course music and art, that of his time and ours.

Schubert himself was the first performer of the cycle. He played and sang it for his circle of friends. One of them, Joseph von Spaun, recalled thirty years later how he had received the invitation: ‘Come to Schober's house today, I am going to sing you a cycle of eerie songs. I am curious to see what you say about them. They have cost me more effort than any of my other songs’.Spaun continued: ‘We were absolutely stunned by the sombre tone of these songs, and Schober said he liked only one, The Linden Tree.Spaun later recorded the composer's lapidary response to his friends' astonishment: ’I like these songs better than all the others, and you will like them too.

[Ian Bostridge (London, 1964), photo by Sim Canetty Clarke].

It is of course easy to interpret these songs from the perspective of Schubert's personal biography.Sick with syphilis from at least November 1822, the composer endured not only the sufferings of his illness, but the periodic torture of treatments as syrupy as they were futile, which would justify the overwhelmingly desolate and despairing tone of his music.But the relationship between the life and work of any artist is of course much more complex, and Bostridge takes pains to dispel clichés (most importantly in biographical matters, the insidious misconception that Schubert lived in squalor and without artistic recognition all his life) and to widen the focus of his gaze.We do not know at what point Schubert became acquainted with the first twelve poems, but from them he wrote a song cycle in February 1827. (sorry for un-complete translation, cannot feed 16 000 words into translation machine ...)

Un hombre que camina

[El monje frente al mar de Caspar David Friedrich (Staatliche Museen, Berlín)]

Acantilado publica el obsesivo estudio del tenor británico Ian Bostridge sobre una de las obras cumbres del Romanticismo alemán, el ciclo de canciones Viaje de invierno de Franz Schubert

Franz Schubert (Viena, 1797-1828) compuso Winterreise (Viaje de invierno), un ciclo de veinticuatro lieder a partir de poemas de Wilhelm Müller (Dessau, 1794-1827), en dos fases separadas por unos diez meses al final de su corta vida. Müller, que ejercía desde 1820 como bibliotecario ducal en su ciudad natal, era un poeta bien conocido por el compositor, quien había compuesto en 1823 su primer gran ciclo de canciones (La bella molinera) a partir de otra de sus colecciones. Fue justo en 1823 cuando Müller publicó en la revista Urania unos poemas bajo el título de Canciones de viaje de Wilhelm Müller. El viaje de invierno. En 12 lieder. Al año siguiente publicó los veinticuatro poemas del ciclo en un libro titulado Poemas de los papeles legados por un corneta del bosque errante. Canciones de la vida y el amor. No sabemos en qué momento Schubert conoció los doce primeros poemas, pero a partir de ellos escribió un ciclo de canciones en febrero de 1827. El editor vienés Tobias Haslinger lo editó en enero de 1828. Para entonces, el compositor había descubierto ya la colección completa y en el otoño de aquel mismo 1827, amplió su ciclo inicial hasta la forma definitiva. Haslinger los publicó así el último día de 1828, cuando Schubert llevaba ya seis semanas muerto y Müller, que jamás llegaría a oír estas canciones, quince meses.

Winterreise es un auténtico fetiche de la cultura occidental y uno de los medios más asequibles y eficaces para conocer de primera mano y profundizar en el universo del Romanticismo alemán, que tan enorme influencia ha tenido en la forja de nuestro mundo, no sólo en el ámbito de la cultura, sino también en el de la sociedad y la política. No hay excusas. Las grabaciones del ciclo pasan ampliamente del centenar y en cualquier plataforma de streaming o de vídeos se pueden encontrar por decenas. Los textos están publicados en ediciones muy asequibles y se puede llegar a ellos de forma gratuita por internet de muchas maneras (eso sí, ojo con las fuentes y las traducciones).

[“Viaje de invierno” de Schubert. Anatomía de una obsesión Ian Bostridge. Traducción de Luis Gago. Acantilado, Barcelona, 2019. 385 páginas. 24 euros]

La figura del caminante, del errabundo, del extraño, del desclasado es un auténtico tópico de la cultura romántica alemana, con una extensa e intensa trayectoria a lo largo de todo el siglo XIX. Pese a sus claras raíces históricas, vinculadas a un espacio y un tiempo muy concretos, hay en el ciclo schubertiano muchos elementos que lo acercan a la sensibilidad contemporánea. Para empezar, Schubert eliminó el artículo determinado de su ciclo: Die Winterreise (El viaje de invierno, que así se titulaba la colección de poemas de Müller) pasó a ser Winterreise (Viaje de invierno) a secas, y en esta simple abreviación el compositor no sólo se apropia del material poético de partida de forma radical, sino que lo hace más abstracto y universal. Algo extremadamente moderno, como moderna es la ausencia de una auténtica trama narrativa: hay mucho de beckettiano en una obra que presenta la realidad como realmente la percibimos, de forma fragmentada. El tema es por supuesto universal y eterno. El caminante de Schubert está envuelto en el aura de misterio que caracteriza a los héroes de un Lord Byron, héroes trágicos de cuyo origen apenas sabemos nada, pero también es el individuo que vive su desengaño amoroso con una angustia existencial de la que está plagada la literatura, la filosofía y el arte del último siglo. El hombre que camina es también el hombre que sufre. Por desamor.

youtube

Cualquier lectura mínimamente atenta de la obra puede descubrir estas claves y muchas otras: la soledad, el dolor, el frío (no sólo físico), la nostalgia, la desesperación, la muerte, la locura… El tenor Ian Bostridge (Londres, 1964) ha ido más allá. Obsesionado con la obra desde sus primeros acercamientos, cuando aún era niño, y después de haberla interpretado infinidad de veces durante tres décadas por medio mundo, Bostridge ha escrito sobre ella un libro extraordinario, un libro-río que desborda cualquier acercamiento convencional al ciclo. Sin desdeñar el análisis musical, el tenor londinense mira detrás de cada palabra, indaga en cada signo misterioso o ambiguo, profundiza con escalpelo en cada rastro de vida para darle su adecuado contexto, una contextualización amplia, que remite a la política, la sociedad, la tradición, la ciencia y por supuesto la música y el arte, el de su tiempo y el del nuestro.

Fue el propio Schubert el primer intérprete del ciclo. Lo tocó y lo cantó para su círculo de amigos. Uno de ellos, Joseph von Spaun, recordaba treinta años después cómo había recibido la invitación: “Ven hoy a casa de Schober, voy a cantaros un ciclo de canciones espeluznantes. Tengo curiosidad por ver lo que decís de ellas. Me han costado más esfuerzo que cualesquiera otras de mis canciones”. Spaun continuaba: “Nos quedamos absolutamente anonadados con el tono sombrío de estas canciones, y Schober dijo que sólo le había gustado una, El tilo”. Recogía después Spaun la respuesta lapidaria del compositor a la estupefacción de sus amigos: “A mí me gustan estas canciones más que todas las demás, y a vosotros también os pasará lo mismo”.

[Ian Bostridge (Londres, 1964). La foto es de Sim Canetty Clarke]

Es fácil por supuesto interpretar estas canciones desde la perspectiva de la biografía personal de Schubert. Enfermo de sífilis al menos desde noviembre de 1822, el compositor pasaba no sólo por los padecimientos propios de su enfermedad, sino por la periódica tortura de unos tratamientos tan sañudos como inútiles, lo cual justificaría el tono abrumadoramente desolado y desesperanzado de su música. Pero la relación entre la vida y la obra de cualquier artista es por supuesto mucho más compleja, y Bostridge se esfuerza en deshacer tópicos (el más importante en asunto biográfico, esa insidiosa y falsa idea de que Schubert vivió poco menos que en la miseria y sin reconocimiento artístico alguno toda su vida) y en ampliar el foco de su mirada. La angustia existencial del protagonista es fácil de reconocer, y en torno a ella se centran la mayor parte de los comentarios y análisis de la obra, pero Bostridge ahonda con sutil inteligencia en los elementos de crítica social y política, que permiten reconstruir el Viaje de invierno desde una perspectiva diferente.

Müller y Schubert escribieron sus respectivas obras en el conocido como período Biedermeier, nombre con el que se definen los modos de vida y la cultura del imperio austriaco entre la derrota de Napoléon y el inmediato Congreso de Viena de 1815 y la oleada revolucionaria de 1848. Aunque a la época se la suele caracterizar con la dulce visión de una clase burguesa acomodada dedicada a sus negocios y a sus inocentes divertimentos de salón, se trata realmente de un período de reacción política, que vivió sus momentos más virulentos justo en la década de 1820, cuando tras las leyes de Carlsbad de 1819 se impuso en toda Austria un régimen marcado por la censura, la represión de las más elementales libertades y un clima general de desconfianza y tensiones que afectaron especialmente a los artistas. Pese a su cargo público, vinculado a la corte ducal de Dessau, Müller era un liberal, y en el ciclo pueden rastrearse signos de malestar social y de acerba crítica política que Bostridge amplía usando la lupa con maestría, como cuando tras el humilde chamizo del carbonero que el caminante utiliza en su descanso del décimo lied del ciclo apuntan los carbonarios, revolucionarios italianos antiaustriacos que Müller seguramente conoció de cerca, pues había viajado por Italia entre 1817 y 1818.

[Dos hombres contemplando la luna de C. D. Friedrich (Galería Neue Meister de Dresde)]

Pero hay mucho más. Bostridge indaga en la germinación del nacionalismo alemán, en la obsesión romántica por la muerte y la aversión a la democracia, en el surgimiento de los sentimientos patrióticos, en la ironía sobre la autosatisfacción del mundo burgués… Con una estructura sencilla y previsible (va analizando las veinticuatro canciones una a una), el libro contiene también un repaso somero de cómo los avances científicos estaban transformando el mundo, y Bostridge explica a la luz de la razón los fuegos fatuos, el fenómeno del parhelio, los cristales de nieve, los glaciares o cómo la idea de Darwin acabaría por liquidar al vitalismo… La naturaleza como gran topos romántico encuentra lógicamente su espacio, pero es una naturaleza básicamente hostil, estúpida, maliciosa, que en muchas ocasiones se convierte en símbolo. Porque símbolos son los cuervos o el tilo, cuya flor es capaz de desencadenar los procesos de la memoria como la magdalena de Proust.

En la interpretación de la realidad cultural que vio nacer Winterreise, Bostridge convoca por supuesto a Goethe, Brentano, Friedrich, Novalis, Byron, Jean-Paul, Hoffmann, Rousseau o Schopenhauer, pero también figuran J. M. Coetzee, Thomas Mann, e e cummings, Samuel Beckett o Bob Dylan. Las referencias modernas no son gratuitas, se sustentan en hilos muy sutilmente escogidos y amarrados. Y por ese mismo mundo circula también esa imaginería que conocimos en su día por las novelas góticas y sentimentales y que han difundido las películas de época: el sonido del cuerno de caza, los coches de posta, los intercambios epistolares…

[Un paseo al atardecer de Caspar David Friedrich (Museo J. Paul Getty, Los Ángeles]

Pero Schubert fue músico, y Winterreise, una obra esencialmente musical. Bostridge no se olvida por supuesto de ello, y va dejando un reguero de apreciaciones que tienen que ver en muchos casos con su propia experiencia personal, aunque no olvida detalles analíticos. En la mayoría de los casos, el enfoque de los comentarios puramente musicales tiene pretensiones divulgativas y no técnicas. Hay excepciones. Los pianistas acompañantes apreciarán mucho, por ejemplo, sus disquisiciones sobre la asimilación del tresillo a un ritmo con puntillo en el comienzo del sexto lied. En el fondo, las distintas posibilidades a la hora de afrontar las canciones en detalles como ese (y otros) llevan al autor a defender una generosa libertad interpretativa y a definir la obra musical como el resultado de un acuerdo entre compositor, intérprete y público.

Winterreise termina con una de las canciones más enigmáticas y difíciles de todo el ciclo, Der Leiermann (El zanfoñista; durante mucho tiempo se tradujo como El organillero, nunca supe por qué, la referencia a la viola de rueda es muy evidente), “más antimúsica que música, y que llega al final de 70 minutos de intensa expresión lírica y declamación vocal”, como dice explícitamente Bostridge. La presencia del viejo y pobre tañedor de zanfoña le sirve al autor para recrear la historia del instrumento, sondear en la relación entre música culta y folclórica o volver a la crítica social. Pero la canción resulta ciertamente inspiradora, y permite interpretaciones muy variadas. Tradicionalmente, se ha relacionado con la cercanía de la muerte, e incluso se ha visto en el zanfoñista a una representación simbólica de la parca. Yo en cambio siempre quise ver en él la esperanza. El zanfoñista es el primer ser humano con el que el caminante se cruza en su amargo deambular, y su compañía puede verse como un nuevo comienzo. Pero Bostridge apunta otra idea muy interesante: quizás el zanfoñista siempre estuvo ahí. Desde este punto de vista, el viaje del caminante se convertiría simplemente en el relato que nuestro protagonista ha hecho al pobre viejo de sus tribulaciones, acaso para convencerlo (en la línea de los famosos versos de Calderón) de que siempre puede hallarse a alguien más desgraciado que uno mismo. ¿Querrá ahora acompañarlo en su vagar y poner música a sus canciones? Si la respuesta es que sí, habrá que volver a interpretar (escuchar) Winterreise desde el principio hasta el final, y seguir así en un eterno retorno con el que, en el fondo, siempre soñamos los obsesos de sus versos y de sus pentagramas.

youtube

—————————————————————–

ALGUNAS REFERENCIAS PARA VER Y OÍR

La página web Arkivmusic referencia ahora mismo 137 registros de Winterreise, pero sin duda hay muchos más. Aunque el tono sombrío de las canciones y una tradición creada sólo después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, y en la que tuvo mucho que ver la extraordinaria personalidad y popularidad del barítono Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, relaciona el ciclo con voces graves, el original está escrito para tenor, y de hecho Ian Bostridge comenta que al transportarlo a otro tipo de voces se pierden algunos de los matices que aportan las relaciones tonales entre las distintas canciones.

Por suerte, hoy las grabaciones de voces de tenor son normales. Está a punto de ponerse a la venta (el próximo viernes 23 de agosto lo anuncia Amazon) su última grabación, un registro en vivo para el sello Pentatone con el acompañamiento del compositor Thomas Adès, pero Ian Bostridge dejó ya un registro con el noruego Leif Ove Andsnes (2004), y cuatro años antes había participado igualmente en la película que filmó David Alden de la obra; entonces contó con el acompañamiento de Julius Drake (ojo, porque la edición original no tiene subtítulos en español).

Entre las versiones de tenor hay que destacar también al histórico Peter Anders (1945), a Peter Pears (con Benjamin Britten, 1963), Peter Schreier (con Sviatoslav Richter, en 1985) y más recientemente, además de a Bostridge, a Mark Padmore (dos veces, la segunda de ellas, aún reciente -2018-, con un instrumento de época en el acompañamiento). También con instrumento de época es la versión de Werner Güra (2010) o la primera de Christoph Prégardien, junto a Andreas Staier (1998). Jonas Kaufmann grabó el ciclo en 2014.

Entre las versiones de voces graves cabe señalar las históricas de Hans Hotter: su polémico registro de guerra (1942) con Michael Raucheisen y el posterior con Gerald Moore. Entre la infinidad de barítonos y bajos que han grabado la obra, obviamente no puede dejarse pasar a Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau en sus diversos acercamientos a la obra, desde el registro histórico de 1948 con Klaus Billing a las grabaciones junto a Moore, Demus, Brendel o Barenboim. Barenboim acompañó también a Thomas Quasthoff en un recital histórico celebrado en la Philharmonie de Berlín el 22 de marzo de 2005 que DG publicó en DVD. Pero deben tenerse también en cuenta los nombres de Hermann Prey, Matthias Goerne, que lo ha registrado al menos tres veces (en 1997, junto a Graham Johnson en la integral schubertiana de Hyperion, y luego junto a Brendel y Eschenbach), Thomas Hampson, Dietrich Henschel o Florian Boesch, que lo grabó dos veces. De muchas de estas interpretaciones hay versiones en vídeo.

Aunque con más prudencia, las mujeres también se han atrevido con el ciclo de los ciclos, especialmente las voces graves, como las de Christa Ludwig (su registro junto a James Levine en DG está descatalogado, pero puede buscarse su DVD de 1994 con Charles Spencer), Brigitte Fassbaender (junto al compositor Aribert Reimann, EMI, 1988) o Natalie Stutzmann con Inger Södergren (2004). Más raros son los acercamientos de las sopranos, pero la alemana Christine Schäfer se atrevió, con el acompañamiento de Eric Schneider, a grabar el ciclo en el año 2006.

De entre los arreglos que se han hecho de la obra, merece especial mención el que hizo Hans Zender para tenor y pequeña orquesta en 1993 y que grabó casi enseguida Hans Peter Blochwitz con el Ensemble Modern (1995) y poco después (1999) Christoph Prégardien con Klangforum Wien para Kairos. Muy recientemente, su hijo Julian Prégardien ha registrado también el soberbio arreglo de Zender con la Deutsche Radio Philharmonie para Alpha (2018). Hay otro arreglo que merece ser comentado por lo extraordinariamente audaz: lo hizo un virtuoso zanfoñista, Matthias Loibner, y sí, han adivinado, el acompañamiento se hace íntegramente con una zanfoña. La voz la puso una cantante singular, la bosnia Nataša Mirković-De Ro, que se mueve entre el mundo del folk, el clásico y el experimentalismo (ha colaborado con L'Arpeggiata de Christina Pluhar, sin ir más lejos). El sello que en 2010 asumió el riesgo de esta experiencia insólita fue Raumklang. Mi sincero reconocimiento.

[Diario de Sevilla. 19-08-2019]

1 note

·

View note

Text

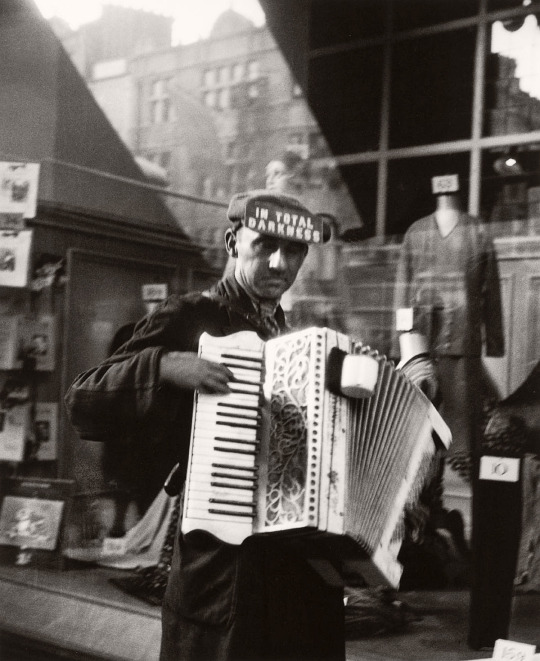

Edith Tudor-Hart 1908-1973

Austrian British Photographer

During the mid-twentieth century Edith Tudor-Hart (née Suschitzky) documented the unstable conditions of the Viennese and British working class. In a secret that was only revealed to her family nearly twenty years after her death, Tudor-Hart had also worked as an important spy for the Soviet Union.

The daughter of a bookshop owner in Vienna, she worked there as a Montessori kindergarten teacher but she had also studied photography at the Bauhaus in Dessau.

An anti-fascist activist and Communist, she saw photography as a tool for disseminating her political ideas. She married Alex Tudor-Hart, who belonged to a well-known radical and artistic family, and fled to England with him in 1933 so that she could avoid prosecution for Communist activities in Austria.

#Edith tudor hart#photography#culture#art collective#photomagazine#london#uk photography#female photographers

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

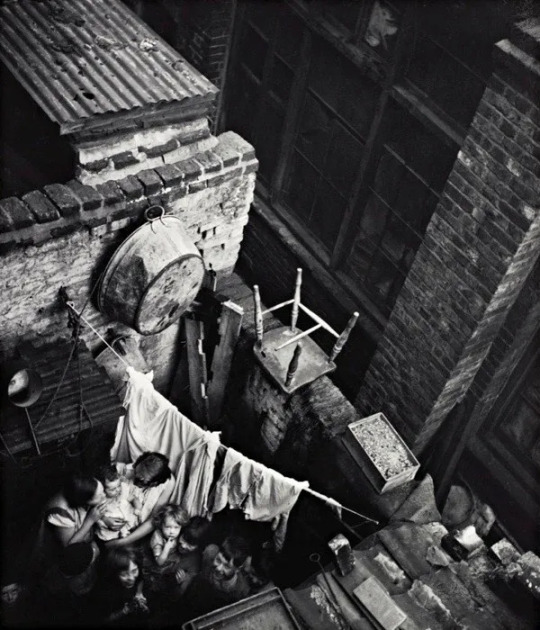

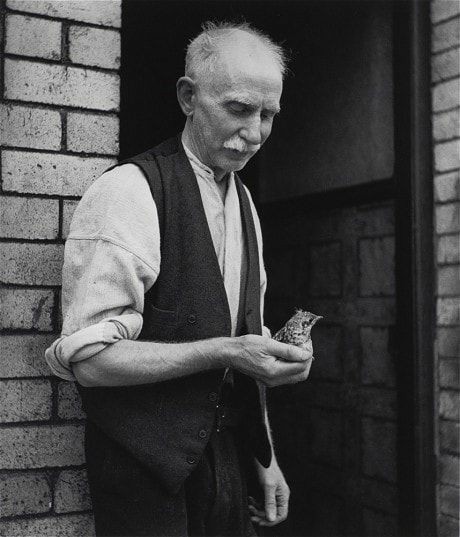

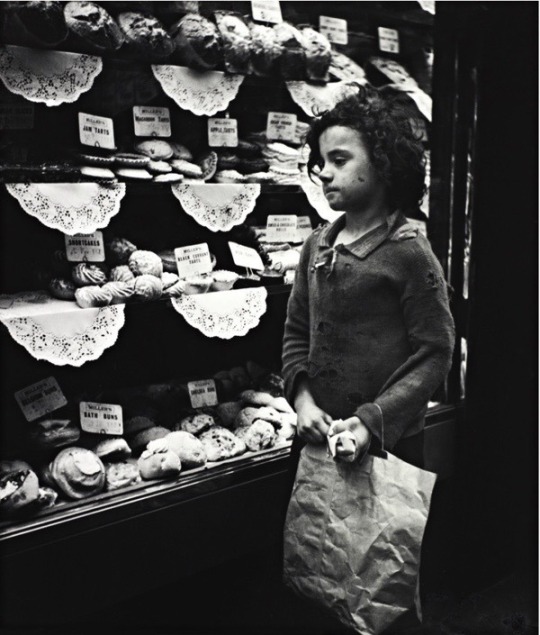

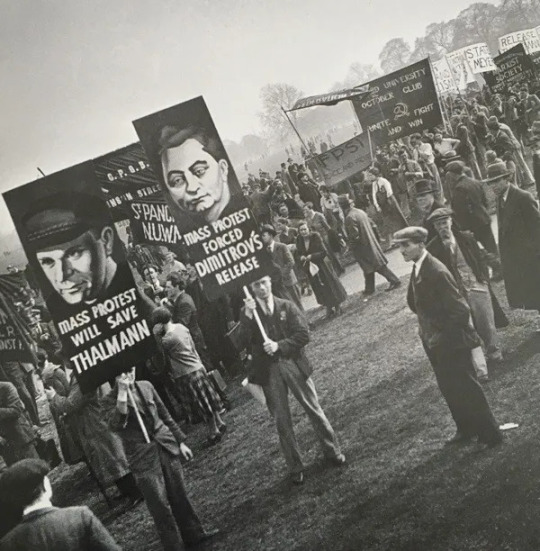

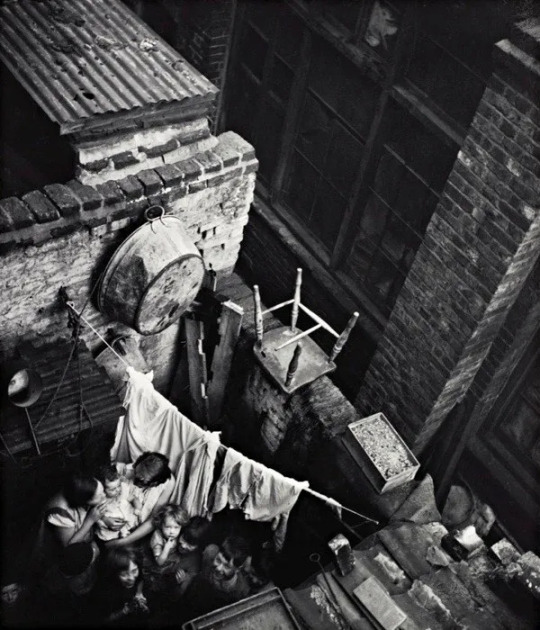

During the mid-20th century Edith Tudor-Hart (born Suschitzky) documented, using photographs, the unstable conditions of the Viennese and British working class.

In a secret that was revealed to her family only nearly twenty years after her death, she had also worked as a prominent spy for the Soviet Union.

Tudor-Hart was born in Vienna to atheistic Jewish parents in 1908. The passion for politics was born in the family, where her father was a Social Democrat.

She studied photography at the Bauhaus in Dessau and shortly thereafter she began photographing workers' demonstrations. The failure of Social Democratic politicians to alleviate the suffering of the workers in Vienna probably influenced her decision to join the Communist Party.

She married a British doctor and fellow anti-fascist activist, Alex Tudor-Hart, and in 1933 the couple fled to Britain to avoid political persecution. While living in South Wales, Edith began taking photographs for national magazines. Her photograph was formed on her communist ideals of hers, which served as a means of documenting the social inequality and deprivation to which the working class was subjected.

Although still active in the 1950s, the difficulties of finding work as a female photographer eventually led her to abandon photography altogether. She died, relatively unknown, in 1973 and only two years after her death was the importance of her documentary photography recognized.

*****

1) Communist-Party-demonstration in Hyde-Park c.1934

2) Selfportrait - c.1936

3) Home - No Dole - London -1931

4) Slums at Gee St - Clerkenwell -1936

5) Unemployed Workers’ Demonstration - 1932

6) Slum Housing - Vienna - 1931

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Agnes, Duchess consort of Saxe-Altenburg née Anhalt-Dessau, 1880s.

Maternal aunt of Princess Louise Margaret, Duchess of Connaught.

On 28 April 1853, Agnes married Ernst of Saxe-Altenburg.

They had one daughter, Princess Marie of Saxe-Altenburg.

As their only son died as an infant, the duchy would be inherited by their nephew Ernst upon Ernst I's death in 1908.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Please everyone sign the petition below to get justice for Oury Jalloh. He came to Germany as an asylum seeker from Sierra Leone. On 7th January 2005 he was burnt to death by police in a cell in Dessau, Germany. The petition is really close to its goal! #JusticeForOuryJalloh

https://www.change.org/p/mein-freund-ouryjalloh-es-war-mord-wir-fordern-l%C3%BCckenlose-aufkl%C3%A4rung

187 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cemetery

A cemetery is a place in which dead human bodies and cremated remains are buried, usually with some form of marker to establish their identity. The term originates from the Greek κοιμητήριον, meaning sleeping place, and can include any large park or burial ground specifically intended for the deposit of the dead. Cemeteries in the Western world are also typically the place where the final ceremonies of death are observed, according to cultural practice or religious belief. Cemeteries are distinguished from other burial grounds by their location and are not usually adjoined to a church, as opposed to a "graveyard" which is located in a "churchyard," which includes any patch of land on church grounds. A public cemetery is made open for use by a surrounding community; a private cemetery is used only by a portion of the population or by a specific family group.

Contents

1 History

2 Establishments and regulations

3 Famous cemeteries worldwide

4 References

5 External Links

6 Credits

1.1 Cemetery reform

1.2 Military cemeteries

1.3 Later developments

2.1 Family cemeteries

A cemetery is generally a place of respect for the dead where the friends, descendants, and interested members of the public may visit to remember and honor those buried there. For many, it is also a place of spiritual significance, where the dead may visit from the afterlife, at least on occasion.

Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn, New York

History

The grave of an infant at Horton, Northamptonshire.

The term cemetery was first used by early Christians and referred to a place for the Christian burial of the dead, often in Roman catacombs. The earliest cemetery sites can been traced back to the fifteenth century and have been found throughout Europe, Asia, and North America in Paleolithic caves and fields of prehistoric grave mounds, or barrows. Ancient Middle Eastern practices often involved the construction of graves grouped around religious temples and sanctuaries, while early Greek practices buried the dead along the roads leading to their cities.

Early burial grounds consisted of earthen graves, and were often unsightly and hasty places to dispose of the dead. European burial was customarily under the control of the church and took place on consecrated church ground. Though practices varied, in continental Europe, most bodies were buried in a mass grave until they had decomposed. The bones were then exhumed and stored in ossuaries either along the arcaded bounding walls of a cemetery or within the church, under floor slabs and behind walls.

The majority of fifteenth century Christian burial grounds became overcrowded and consequently unhealthy. The first Christian examples of cemeteries outside of a churchyard were founded by Protestants in response to overcrowded churchyards and the desire to physically and spiritually separate the dead from the living, a concept often intertwined with the Roman Catholic faith. Early cemetery establishments include Kassel (1526), Marburg (1530), Geneva (1536), and Edinburgh (1562). The structure of early individual grave sites often reflected the social class of the dead.

Cemetery reform

The formation of modern cemetery structures began in seventeenth century India when Europeans began burying their dead in cemetery structures and erecting vast monuments over the graves. Early examples have been found in Surat and Calcutta. In 1767, work on Calcutta’s South Park Street Cemetery was completed and included an intricate necropolis, or city of the dead, with streets of mausolea and magnificent monuments.

In the 1780s and 1790s similar examples were to be found in Paris, Vienna, Berlin, Dessau, and Belfast. The European elite often constructed chamber tombs within cemeteries for the stacking of family coffins. Some cemeteries also constructed a general receiving tomb for the temporary storage of bodies awaiting burial. In the early 1800s, European cities faced major structural reforms that included the restructuring of burial grounds. In 1804, for hygienic reasons, French authorities demanded that all public cemeteries be established outside city limits. Entrusted with a project to bury the dead in a way that was both respectful and hygienic, French architect Alexandre Brogniart designed a cemetery structure that included an English landscape-garden. The result, Mont-Louis Cemetery, would become world famous.

In 1829, similar work was completed on St. James Cemetery in Liverpool, designed to occupy a former quarry. In 1832 Glasgow’s Necropolis would follow. After the arrival of cholera in 1831, London was also forced to establish its first garden cemeteries, constructing Kensal Green in 1833, Norwood in 1837, Brompton in 1840, and Abney Park in 1840, all of which were meticulously landscaped and adorned with intricate architecture. Italian cemeteries followed a different design, incorporating a campo santo style which proved larger than medieval prototypes. Examples include Certosa at Bologna, designed in 1815, Brescia, designed in 1849, Verona, designed in 1828, and the Staglieno of Genoa, designed in 1851 and incorporating neoclassical galleries and an extensive rotunda.

Over time, all major European cities were equipped with at least one reputable cemetery. In larger and more cosmopolitan areas, such cemeteries included great architecture. U.S. cemeteries of similar structure included Boston’s Mount Auburn Cemetery, designed in 1831, Phildelphia’s Laurel Hill Cemetery, designed in 1839, and New York City’s Green-wood Cemetery, designed in 1838. Many southern U.S. cemeteries, such as those in New Orleans, favored above ground tomb structures due to strong French influence. In 1855, architect Andrew Downing suggested that cemetery monuments be constructed in such a way as to not interfere with cemetery maintenance; with this, the first "lawn cemetery" was constructed in Cincinnati, Ohio, a burial park equipped with memorial plaques installed flush with the cemetery ground.

Military cemeteries

Arlington National Cemetery, Washington D.C.

American military cemeteries developed out of the duty of commanders to care for their comrades, including those that had fallen. When the casualties of the American Civil War reached incomprehensible numbers, and hospitals and burial grounds overflowed with the bodies of the dead. General Montgomery Meigs proposed that more than 200 acres be taken from the estate of General Robert E. Lee for the purpose of burying the causalities of war. What followed was the development of Arlington National Cemetery, the first and most prestigious of war cemeteries to be erected on American soil. Today Arlington National Cemetery houses the bodies of those who died as active-duty members of the Armed forces, veterans retired from active military service, Presidents or former President of the United States, and any former member of the armed services who received a Medal of Honor, Distinguished Service Cross, Silver Star, or Purple Heart.

Other American military cemeteries include the Abraham Lincoln National Cemetery, the Gettysburg National Cemetery, the Knoxville National Cemetery and the Richmond National Cemetery. Internationally, military cemeteries include the Woodlands Cemetery near Stockholm (1917), the Slovene National Cemetery in Zale (1937), the San Cataldo Cemetery in Modena (1971), and the Cemetery for the Unknown in Hiroshima, Japan (2001).

Later developments

The change in cemetery structure sought to re-establish the "rest in peace" principle. Such aesthetic cemetery design contributed to the rise of professional landscape architects and inspired the making of grand public parks. At the turn of twentieth century, cremation offered a more popular, though in some places, controversial option to casket burial.

A "green burial" ground or "natural burial" ground is a type of cemetery which places a corpse into the soil to naturally decompose. The first of such cemeteries was created in 1993 at the Carlisle Cemetery in the United Kingdom. The corpse is prepared without traditional preservatives, and is buried in a biodegradable casket or cloth shroud. The graves of green burials are often minimally marked as to not interfere with the landscape of the cemetery. Some green cemeteries use natural markers such as shrubs or trees to denote a grave site. Green burials are posed as an environmentally friendly alternative to customary funeral practices.

Establishments and regulations

Internationally, the style of cemeteries has varied greatly. In the United States and many European countries, cemeteries may use tombstones placed in open spaces. In Russia, tombstones are usually placed in small fenced family lots. This was once a common practice in American cemeteries, and such fenced family plots can still be seen in some of the earliest American cemeteries constructed.

Cemeteries are not governed by laws that apply to real property, although most states have established laws that specifically apply to cemetery structures. Some common regulations require that each grave must be set apart, marked, and distinguished. Cemetery regulations are often required by departments of public health and welfare, and may prohibit future burials in existing cemeteries, enlargement of existing cemeteries, or the establishment of new ones.

Cemeteries in cities use valuable urban space, which may pose a significant problem within older cities. As historic cemeteries begin to reach their capacity for full burials, alternative memorialization, such as collective memorials for cremated individuals, became more common. Different cultures have different attitudes toward the destruction of cemeteries and subsequent use of the land for construction. In some countries it is considered normal to destroy the graves, while in others the graves are traditionally respected for a century or more. In many cases, after a suitable period of time has elapsed, the headstones are removed and the cemetery can be converted into a recreational park or construction site.

Trespassing against, vandalizing, or destruction of a cemetery or individual burial plot are considered criminal offenses, and can be prosecuted by the heirs of the involved plot. Large punitive damages, intended to deter further acts of desecration, may be awarded.

Family Cemeteries

A Buddhist graveyard. Kyoto, Japan.

In many cultures, the family is expected to provide the "final resting place" for their dead. Biblical accounts describe land owned by various important families for the burial of deceased family members. In Asian cultures, regarding their ancestors as having spirits who should be honored, families carefully selected the location for burial so as to keep their ancestors happy.

While uncommon today, family or private cemeteries were a matter of practicality during the settlement of America. If a municipal or religious cemetery was not established, settlers would seek out a small plot of land, often in wooded areas bordering their fields, to begin a family plot. Sometimes, several families would arrange to bury their dead together. While some of these sites later grew into true cemeteries, many were forgotten after a family moved away or died out. Groupings of tombstones, ranging from a few to a dozen or more, have on occasion been discovered on undeveloped land. Usually, little effort is made to remove remains when developing, as they may be hundreds of years old; as a result, the tombstones are often simply removed.

More recent is the practice of families with large estates choosing to create private cemeteries in the form of burial sites, monuments, crypts, or mausolea on their property; the mausoleum at architect Frank Lloyd Wright's Fallingwater is an example of this practice. Burial of a body at such a site may protect the location from redevelopment, such estates often being placed in the care of a trust or foundation. State regulations have made it increasingly difficult to start private cemeteries; many require a plan to care for the site in perpetuity. Private cemeteries are nearly always forbidden on incorporated residential zones.

Famous cemeteries worldwide

Père-Lachaise, Paris.

Since their eighteenth century reform, various cemeteries worldwide have served as international memorials, renowned for their meticulous landscaping and beautiful architecture. In addition to Arlington National Cemetery, other American masterpieces include Wilmington National Cemetery, Alexandria National Cemetery and the Gettysburg National Cemetery, a military park offering historic battlefield walks, living history tours, and an extensive visitor center.

Parisian cemeteries of great renown include the Père Lachaise, the world’s most visited cemetery. This cemetery was established by Napoleon in 1804, and houses the graves of Oscar Wilde, Richard Wright, Jim Morrison, and Auguste Comte among others. Paris is also home to the French Pantheon, completed in 1789. At the start of the French Revolution, the building was changed from a church into a mausoleum to hold the remains of noteworthy Frenchmen. The pantheon includes the graves of Jean Monnet, Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas, and Marie Curie.

London’s Abney Park, opened in 1840, is also an international place of interest. One of London’s seven magnificent cemeteries, it is based on the design of Arlington National Cemetery. The remaining magnificent seven include Kensal Green Cemetery, West Norwood Cemetery, Highgate cemetery, Nunhead Cemetery, Brompton Cemetery, and the Tower Hamlets Cemetery. England’s Brookwood Cemetery, also known as the London Necropolis, is also a cemetery of note. Established in 1852, it once was the largest cemetery in the world. Today more than 240,000 people have been buried there, including Margaret, Duchess of Argyll, John Singer Sargent, and Dodi Al-Fayed. The cemetery also includes the largest military cemetery in the United Kingdom. The ancient Egyptian Great Pyramid of Giza, marking the tomb of Egyptian Pharaoh Khufu, is also a well-known tourist attraction.

References

Curl, James Stevens. 2002. Death and Architecture. Gloucestershire: Sutton. ISBN 0750928778

Encyclopedia of U.S. History. Cemeteries. U.S. History Encyclopedia. Retrieved June 4, 2007.

Etlin, Richard A. 1984. The Architecture of Death. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Gale, Thomas. Cemeteries. Thomas Gale Law Encyclopedia. Retrieved June 4, 2007.

Oxford University Press. Cemetery. Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture. Retrieved June 4, 2007.

Worpole, Ken. 2004. Last Landscapes: The Architecture of the Cemetery in the West. Reaktion Books. ISBN 186189161X

External Links

All links retrieved January 23, 2017.

Cemeteries and Cemetery Symbols

London Cemetery Project: 130 cemeteries with high-quality photos.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats. The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

Cemetery history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

History of "Cemetery"

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sophie Elisabeth of Anhalt-Dessau (10 February 1589 – 9 February 1620) was a German princess of the House of Ascania. She was the last abbess of Gernrode (r.1593-1614). After leaving the abbey, Sophie Elisabeth married George Rudolf of Liegnitz and was duchess of Liegnitz until her death in 1620.

#Sophie Elisabeth of Anhalt-Dessau#House Anhalt-Dessau#House Ascania#XVI century#XVII century#people#portrait#paintings#art#arte

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

News: New Podcast From Kim Noble With Julian Barratt, Adam Buxton and Kim’s Mum

By Bruce Dessau on 10/8/2020

Award-winning performance artist and comedian Kim Noble is set to launch a brand new 10-part podcast entitled ‘Futile Attempts (At Surviving Tomorrow)’, with weekly episodes released on all Podcast Apps, from 19th August.

Unlike any podcast you’ve heard before, ‘Futile Attempts (At Surviving Tomorrow)’ mixes live field recordings with a voice over narrative from Kim. Armed with a hidden mic stuck under his jacket, Kim captures recordings from characters who become embroiled in his absurd life. Featuring archive footage of various break ups from his past, phone calls to Kevin Costner’s agent and conversations with his Mum, this ludicrous comedic sonic journey takes you to Sting’s mansion, down a sewer, underneath a church altar and into the arms of a Hounslow based cult.

Produced by Novel, each episode sees Kim attempt to find reasons and methods to survive life. Exploring a universal theme in each episode, Kim takes the listener on a journey to the centre of his warped reality. Starring Julian Barratt as God, Adam Buxton as himself and a ‘bloke Kim sometimes chats to on a park bench’ as himself, with sound by award-winning composer Benbrick.

Using his provocative and humorous style to expose the human condition: Kim Noble explores notions of death, sexuality, gender and religion with dry comedic wit of tragedy meshed with absurdity.

Kim Noble was one half of the Perrier best newcomer Award-winning, BAFTA-nominated experimental art-comedy duo Noble and Silver. He's since featured in shows including The Mighty Boosh, and performed critically acclaimed solo shows worldwide including Kim Noble Will Die in 2009 and the award winning You're Not Alone in 2015, about loneliness and his father's dementia.

Futile Attempts (At Surviving Tomorrow) will be released weekly on all Podcast apps from 19th August and released as a full box-set series on Spotify on the same date.

#Julian Barratt#Kim Noble#Adam Buxton#Futile Attempts#Futile Attempts At Surviving Tomorrow#Futile Attempts (At Surviving Tomorrow)#`❦

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

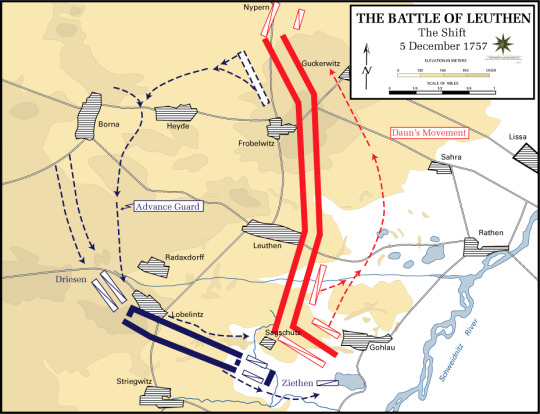

On this day in history: Battle of Leuthen (1757): Frederick the Great perfects his oblique order.

The Seven Years War (1756-1763) is regarded by many as the first true world war. It was fought on five continents and in many oceans, it was at its heart a battle of supremacy for worldwide influence, namely between Britain and France. Its origins were in colonial conflict between these two powers in North America which became known as the French & Indian War. However, it was also fought with a particularly ferocity in Europe. Britain was not a main participant involved in the European theater, instead this sector of fighting largely centered around their two main allies in this conflict and question of continental supremacy in Central Europe. it was the seeds to the so called German Question, would German speaking lands of Europe, then divided into the many entities of the Holy Roman Empire, be lead by the continual leadership of the Hapsburg Realm known based in the Archduchy of Austria or would it follow the Kingdom of Prussia?

Prelude: The German Question

-By the 18th century, the Holy Roman Empire, Central Europe and the German speaking peoples of Europe had largely been under the leadership of Vienna and the Hapsburg dynasty, then known as the Archduchy of Austria with its rulers serving as Holy Roman Emperor. A title that conveyed certain ceremonial & political weight with it. The Holy Roman Empire was a collection of mostly German speaking states that was concentrated in modern day Germany mostly alongside other parts of Central Europe. The Hapsburgs were its leading family and also held sway directly over parts of Italy, Bohemia, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Croatia, Italy and other parts of the Balkans. In the past its traditional enemy was the Ottoman Empire, long seen as the last bastion between Christendom and the spread of Islam throughout Europe.

-Its success against the Ottomans in the Great Turkish War (1683-1699) alongside Russia, Poland, Venice and other nations has essentially reversed the trend of Ottoman encroachment. Instead, the Turks now found themselves on the defensive and largely having to compete at against an expansionist Russia. Meanwhile, Austria challenged its longtime enemy France, now run by the Bourbon dynasty for control over influence within continental Europe.

-Austria sought Britain and the Dutch Republic’s assistance in containing French supremacy in Western and Central Europe, all these nations had a mutual interest in containing the expansion in French power which was coupled with the Bourbon’s taking over Spain and its empire too.

-Austria and France clashed in the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714) and the subsequent War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748).

-It was in the last 17th and early 18th century and the aforementioned wars, that the Kingdom of Prussia, centered in northeastern Germany and run by the Lutheran Hohenzollern dynasty looked to gain power and influence.

-Prussia was comparatively small relative to Hapsburg lands but it built its reputation on its military prowess, starting with Frederick WIlliam, Elector of Brandenburg. As a member state of the Holy Roman Empire, it had a vote in the election of the Holy Roman Emperor, who was not a direct rule of other members of the fragmentary “empire” but a “first among equals” and one who held the most sway over the collective.

-Frederick William, his son and grandson (Frederick I) & (Frederick William I) were recognized Electors of Brandenburg and in the latter two’s case as Kings in Prussia and they made many military reforms that improved Prussia’s army.

-Under Leopold I, Prince of Anhalt-Dessau who served as Prussia’s royal military overseer a number of key reforms which set it apart from all other European armies were implemented. Firstly, he replaced the traditional wooden ramrod of muskets with which a soldier must plunge the musket ball into the barrel with an iron ramrod. The difference was stark, a more durable iron ramrod had a longer shelf-life than wood, was less prone to breaking and therefore was quicker for reloading. Secondly, he introduced the goose-step march which slowed the march of the army, conserving their energy when going into battle and providing for more uniform cohesion. Thirdly, he increased the role of the fife and drum musicians, making musicians out of some soldier and increasing the size of military marching bands, which was seen to boost morale. Fourth, he introduced relentless drilling with emphasis on the rate of fire and the maneuverability of units in formation. Fifth, the officer corps were directed and limited to the Junker (Prussian nobility) class which had a good miltary education and was firmly loyal to the Prussian nation and King. Additionally, firm but harsh corporal punishment was introduced to instill discipline and deter desertion. Finally, politically the introduction of mandatory conscription was more enforced in Prussia.

-All these elements left in place the Prussian Army becoming perhaps the most well oiled war machine in Europe at the time with only Austria, France, Britain and Russia being competitors, in time they would come to find out just how well trained and efficient this force was.

-As Prussia’s military reputation grew, so did its influence in the world of German politics and Austria clearly began to see it as a rival. Though initially, in the War of the Spanish Succession, both nations were together to curb French influence, with the Prussians serving with distinction as mercenaries under the Holy Roman Empire’s banner.

-1740, however changed things when two new rulers came to rule over Prussia & Austria. It started with Frederick II, the new King of Prussia. Frederick had a troubled relationship with father, Frederick William I. His father was well educated in government and military affairs and had hoped his son and heir would be inclined towards such matters too. Frederick was instead, prone to the burgeoning trends of the Enlightenment then coming into full flourish and sweeping Europe’s philosophy circles. Frederick was more interested in music, the arts and philosophy. His father also physical and mentally abused him, beating him with a cane and calling him many insults. To add to the strain, he appears to have been a homosexual, something punishable by death even for a royal during that time. Famously, he attempted to flee to Britain with his tutor/lover Han Hermann von Katte to escape the abuse by his father. However, both Frederick & Katte were caught in 1730 during their flight. Katte and Frederick were technically army officers and Frederick William I wanted to make an example of them for their flight as a betrayal of the nation. Though Katte’s initial sentence was imprisonment until the King’s death, Frederick William I instead ordered his execution. He made his son watch his friend and lover die by beheading, Frederick is said to have passed out at the sight of his lover’s execution by his father’s order. Frederick himself was also imprisoned by his father for the next two years.

-Eventually, father and son somewhat reconciled. In part, because he got Frederick to marry a woman, Elizabeth Christine of Brunswick-Wolfsbuttel. However, Frederick remained a semi-closeted gay man and never had children with his wife nor had any physical intimacy with her, though appears to have had no affairs with other women either. Instead, he always maintain an interest in the military and quite probably had male lovers & confidantes. Instead, the couple maintained separate residences over the course of their lives and Frederick knew full well the marriage was for political purposes. It was to last from 1733 until his death in 1786.

-Frederick came to the throne in 1740, having inherited a Prussia with a stable economy, efficient administration & most important of all, well trained and sizable army relative to its population. All things despite their often strained relationship he owed to his father. Of his father after his death he said:

“What a terrible man he was. But he was just, intelligent, and skilled in the management of affairs... it was through his efforts, through his tireless labor, that I have been able to accomplish everything that I have done since.”

-1740, also saw accession to the Austrian throne, Maria-Theresa, daughter of Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria. She had married, Francis, Duke of Lorraine, a Franco-German, portion of the Holy Roman Empire. Together, they would co-rule the Hapsburg Empire & give rise to the Hapsburg-Lorraine branch of the family, as Maria-Theresa was the last in the senior line of the Hapsburg family, which is declared to “die out” due to no more direct male heirs. Their subsequent branch would head the family and rule Austria in its many iterations through World War I in the form of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

-The issue of Maria-Theresa’s gender came to be the powder keg for growing Austro-Prussian conflict. However, it was a smokescreen to expand Prussian power at Austrian expense, being just a convenient excuse other rulers needed to undermine Hapsburg rule as Holy Roman Emperors. Charles VI, aware of the problems caused by having no male heirs and relying on a system of primogeniture, where the eldest surviving legitimate male son or nearest male relative was given to rule, was forced to spend much of his reign using diplomacy and concessions to the other Electors of the Holy Roman Empire and great powers of Europe, to recognize his daughter as his heir and as Holy Roman Empress and ruler of Hapsburg lands. The Pragmatic Sanction of 1713 was the recognition by the other powers of Europe of her succession to these lands.

-However, looking to weaken the Austrians and get the balance of power set about in a more favorable fashion, France & Prussia backing the relative of Maria-Theresa, Charles-Albert of Bavaria, proclaimed his right to become Holy Roman Emperor. Making him in effect Charles VII, Holy Roman Emperor. He was of the House of Wittelsbach and his reign interrupted the Hapsburg claim to the title for the preceding 300 years. Citing, Salic Law, from the Middle Ages, neither France nor Prussia could truly “respect” a woman’s claim to hold the title of Holy Roman Emperor or to rule over the Hapsburg lands. For France it was about controlling the balance of power, for Frederick of Prussia, now Frederick II, it was a chance to increase Prussia’s profile. So launched the 8 year long War of the Austrian Succession. The war saw Frederick II invade Austrian Silesia in modern day Poland. With this Maria-Theresa & Frederick II were ever after archrivals.

- By 1745, Frederick’s army time and again surprised the Austrians and Europe at large and had more or less secured its war aims, Silesia. He secured for himself a reputation as a great tactician and for the Prussian army, a sense of true respect for their performance. The treaty of Aix-la-Chappelle in 1748 ended the war, Maria-Theresa was declared to be Holy Roman Empress and ruler of all Hapsburg lands with her husband who became Francis I as Holy Roman Emperor. Their family would continue to succeed them ever after. However, Frederick got to retain control of Silesia and this caused simmering tension and resentment with Maria-Theresa.

Diplomatic Revolution:

-In the years following the Treaty of Aix-la-Chappelle, the political goals of Europe’s great powers realigned. Britain and France still retained colonial rivalries the world over and both sought to have a favorable balance of power on the continent as well. Austria & Britain had been traditional allies for decades but with British support for Prussian claims to Silesia, Maria-Theresa no longer felt Britain could be a dependable ally in what she sought, a reclaiming of Silesia, she needed help to achieve this and turned to an unlikely place, its former rival...France.

-Meanwhile, Britain felt Austria itself was too weak to take on France and therefore was willing to subsidize other powers to contain French ambition on the continent while the Royal Navy & British Army took French colonies elsewhere. So a partner switch developed. Prussia & Britain signed an alliance in January 1756.

-Meanwhile. France at first declared neutrality thanks to diplomacy from Austria which no longer had borders on France’s natural borders and this lead to a thawing of icy relations. A series of treaties was signed between Austria and France in 1756-57 which formed an anti-Prussian coalition between the two and later supplemented by Russia & Sweden. France agreed to support Austria regaining Silesia, and subsidies for Austria to maintain a large army against the Prussians. In exchange at the war’s end, France would gain the Austrian Netherlands (Belgium). This would allow France new ports to threaten Britain.

War:

-War had broken out 1756 officially between Britain and France though their North American colonies had been fighting since 1754.

-Frederick II, sensing the growing alliance against him wanted to preempt any Austrian attack against Silesia and thusly invaded the Austrian ally, the Electorate of Saxony in August 1756, this kicked off the war and lead to many back and forth battles over the next 7 years.

-The war shifted in 1757 to Austrian Bohemia (Czech Republic) and left Prague under siege by the Prussians at one point. Frederick garnered many important early victories but was forced to withdraw in this instance.

-By late 1757, the French were providing Austria the long awaited support for its thrusts into Silesia. Prussia was gradually pushed back following the retreat from Prague and now was facing pressure from multiple approaches.

-This approach culminated in the November 1757 Battle of Rossbach, the only physical battle to involve both France & Prussia against each other. Frederick caught the Austro-Franco army by surprise and inflicted 10,000 casualties to his less than 1,000. France essentially remained a non-entity in this theater for the next several years, though they did continue to fund the Austrians. Austria’s real support would come later from Russia & Sweden against Prussia.

Battle of Leuthen:

-Meanwhile, another and even larger Austrian army was looking to engage Frederick, this one was lead by Maria-Theresa’s brother in law, Prince Charles Alexander of Lorraine. He sought to engage the Prussians and defeat Frederick decisively. Indeed he did defeat the Prussians, not under Frederick’s command at the Battle of Breslau in late November 1757 which threatened all of Prussian Silesia in December with 66,000 soldiers under his command.

-Frederick meanwhile had 33,000 meaning his troops would be outnumbered 2 to 1. Learning of the fall of Breslau, he moved his troops, 170 miles in just 12 days, a very accomplished maneuver given the roads and transport of the times.

-Prince Charles, aware of Frederick’s approach’s toward Breslau, the provincial capital of Silesia. He sought to stop the advance 17 miles west at the town of Leuthen.

-The Austrians hoped to check any Prussian countermove with a force running north to south spread out around Leuthen, knowing the Prussians would come from the west.

-Charles had placed his command in the village church tower to give him more of a vantage point over the rolling countryside displayed before his army. This meant he should be able to anticipate any move Prussia made.

-Frederick however, was quite familiar with the land, having used the Silesians countryside around Leuthen as parade and drilling grounds for the Prussian Army during peace time. Rarely one, to do the expected Frederick wanted to use his tactical prowess against the Austrians.

-His first step was to survey the land and hatch a plan. Austria’s strongest concentration of troops was on the left wing (south end) and their front stretched five miles north to south. Frederick, decided he would make the Austrians think he was in one place and then show in an unexpected place. His goal was to get the Austrians to react to this deceit which would provide an opening to his advantage.

-Realizing a series of low lying hills running almost parallel to the Austrian line lie in front of both armies. Frederick planned to use these hills to cover his troops movements for the main strike. First however, a force of cavalry would would launch an attack to distract the Austrians on the north end of the battlefield, the more lightly concentrated side. The Austrians thinking the attack was now coming from the north instead of the south would transfer the greatest concentration of troops from the south to north and check the Prussian attack. Meanwhile, Frederick employing his favorite tactic, oblique order would march from behind the hills to the now weakened south end of the Austrian line, perform a right angle turn and blast volleys into the weakened line, and roll it up from the south end, essentially performing a bait and switch on the Austrians.

-On the morning of December 5th, 1757, fog came onto the field, making it hard to see either side, this helped the Prussians more than the Austrians.

-Prince Charles saw Frederick’s initial moves early in the morning but interpreted them possibly as a retreat at first Meanwhile, Prussian cavalry attacked the north end of the Austrian line from the woods, indeed it seemed as if the Prussians were attacking the north end, having expected a southern end attack initially hence the greater concentration of troops. The worry was this attack coming from an unexpected direction could contribute to the Prussians rolling up the Austrian line.

-Charles reacted by shifting his entire southern flank’s reserve to reinforce and extend the line to the north. His transfer of troops drew out the line’s length and weakened the southern flank. They would in fact be facing the weaker Prussian attack, while the stronger attack would hit their originally anticipated southern flank, now weakened by deception. Little did he realize, he had fallen in Frederick’s trap.

-Indeed, Frederick marched his troops quietly in the fog and behind the hills before the Austrians, before he performed a right turn and executed oblique order, essentially moving the bulk of one’s forces against the weakened flank of the enemy and pushing them back so as to create an opening that forces the enemy line to shift, contort and break. His troops were well timed and disciplined to pull off such a maneuver.

-The main Prussian force marching south behind the hills was in two parallel columns. They moved past the length of the Austrian line and out of sight totally before veering eastward until they formed virtually a right angle with the Austrian line who was surprised by the sight of the Prussian army emerging from fog in battle line formation. The Prussian infantry opened fire with devastating volleys, keep in mind, the rate of five for Prussian infantrymen was 5 shots a minute per man compared to the 3-4 averaged by other European armies of the time. Their hard training had paid off with a faster and consequently more damaging rate of fire than their enemy.

-The Prussians now pushed forward against the confused and bedazzled Austrian army, which ironically, seeking to avoid being rolled up in the opposite direction, weakened their originally stronger side only to be rolled up anyway from a now completely unexpected direction.

-The Austrians had a few regiments try to check the Prussian advance from the south and indeed some artillery pointed south held them at bay but Frederick ordered some artillery of his own to be placed on one of the hills to the west of Leuthen, which in turn enfiladed the Austrian guns and forced them to withdraw.

-Meanwhile the Austrians tried to shift everything south in order to maintain control of the situation but the Prussian cavalry which had launched the screening attack on the Austrin north flank intially had withdrawn until was called into action by Frederick once more, causing more confusion for the Austrians who ultimately withdrew from the field, heading northeast.

-Frederick wanted to pursue but snowfall made him call off the pursuit. That night, Frederick arrived at the castle at nearby Lissa, occupied by both Austrian officers and refugees from villages caught near the battle. He politely surprised the Austrians by acknowledging they did not expect his presence their that night but did ask for lodging. Subsequently he went on to besiege Breslau and force an Austrian surrender.

-The war was far from over and Frederick and indeed Prussia’s fortunes fluctuated until its conclusion in 1763, in which Prussia would technically be the winner, retaining Silesia, in exchange for the recognition of Maria-Theresa’s son, Joseph as her heir. Though the war exhausted both sides in terms of manpower but ultimately, Frederick stopped Austrian +other Germans, French, Russian & Swedish armies from ending Prussia and his reign altogether.

-As a result of his tactical & strategic performance in this war and the preceding War of the Austrian Succession, he earned the historical moniker, Frederick the Great. The Battle of Leuthen was one illustration of the man’s tactical prowess, perhaps the most perfect example of this and more broadly of how far Prussia’s army had come from a comparative German backwater to the premier army on the European continent.

#on this day#military history#Seven Years War#third silesian war#prussia#tactics#oblique order#austria#Frederick the Great#maria theresa#holy roman empire#18th century#military tactics

10 notes

·

View notes

Quote

- "[...] Find me two crosses of the Order Mérite and send them to me, Old Dessauer has kicked the bucket. [...]" - "[...] The old Prince will be so happy when he meets all the devils he kept calling out to; and nobody except Geheimrat Deutsch will wish him a pleasant journey. [...]"

Frederick II. (the Great) to his chamberlain Michael Gabriel Fredersdorf and Fredersdorf’s answer concerning the death of Leopold von Anhalt-Dessau, April 8th and 9th of 1747.

Original German:

Frederick: “[...] schaffe mihr 2 creützer ordre Merite und Schike sie mihr; der alte Dessauer ist verreket. [...]”

Fredersdorf: “[...] Der Alte Fürst wirdt sich recht freuen, wann Er Bey alle die Teuffel komen wirdt, die Er immer so fleißig gerufen; und Niemand wirdt Ihm eine glückliche reise wünschen, als der Geheimtrath Deutsch. [...]”

#their correspondence is absolutely wonderful#frederick the great#michael gabriel fredersdorf#translation by yours truly#please do correct me

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

@ my german speaking followers

i’d like to share this docu series about the death of Oury Jalloh while in police custody 15 years ago.

not only because the state ministry of justice just blocked and hindered two special agents of the state parliament but also because some of my followers might not be aware of this having happened..

every year there are silent vigils so i hope you will take part next time to send a strong signal that this case isn’t resolved yet + to send a message to seehofer that an investigation of racial profiling is very much needed in this country.

15 notes

·

View notes