#cymraeg tag

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Oh yeah question for cymblr, I was asking my dad this and he didn’t know, I was wondering if it was well known or not- I think most saints are called ‘Sant []’, but Saint David always seems to be ‘Dewi Sant’, is there a reason for it being the other way around? Is this way more common than just him bc I can’t think of any besides him. If anyone knows the answer I’d be interested :)

#Cymblr#cymraeg#Cymraeg tag#cymru#Dewi Sant#(If I’m wrong about anything here please tell me but be nice my Welsh is incredibly weak)

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is every single Welsh fic on the website… (some of them aren’t even in Welsh and were mistagged)

True suffering.

#Cymraeg tag#When I become more proficient in Welsh I will start posting in it!! This is a life’s goal of mine

3K notes

·

View notes

Note

PLEASE TELL US ABOUT Y DDRAIG TRAWS!

Certainly! I'm more than happy to oblige.

First though I'm gonna need to tldr: the history of Y Ddraig Goch before we get onto the (accidentally) canonically trans part.

A brief history of Y Ddraig Goch:

(The modern Welsh flag)

Y Ddraig Goch first appears in the tales of the Mabinogi (Charlotte Guest version) in the tale of Lludd and Llefelys where it is fighting a white dragon. The fight is also described/expanded upon in the c. 829 AD text Historia Brittonum (attributed to Nennius) - where the red dragon represents Wales and the white dragon represents the Anglo-Saxons. In the story the red dragon triumphs over the white. Of course, Geoffrey of Monmouth also covers the story c. 1136 in Historia Regnum Brittaniae in which he introduces the concept of the red dragon heralding the arrival of King Arthur.

Geoffrey of Monmouth claims Arthur used a banner featuring a golden dragon. But we also know the accuracy of Monmouth can be questionable at times. Owain Glyndŵr did use a banner with a golden dragon called Y Ddraig Aur - raised in 1401 at Caernarfon - Glyndŵr chose this banner as a nod to the supposed banner of Arthur and his father.

Later on the Tudor monarchs (being a Welsh family) adopted a red dragon on a white and green background in their heraldry. Eventually Y Ddraig Goch on a white and green background became the official badge of Wales in 1800. The design became the official flag of Wales in 1959.

Y Ddraig Traws:

Now for the thing you're all here for -

So, as outlined, the history of the dragon as a national symbol of Wales goes back a long way. If we're just talking post-1959, there's some interesting implications for Y Ddraig Goch's depiction.

This is what the Welsh flag (and Y Ddraig Goch) looked like in 1959 when it was officially adopted as the flag of Wales. It looks broadly the same as the first flag and has some common features - such as not having a penis (or, as in the correct heraldic terminology - a pizzle). Meanwhile, in the arms of the Tudors (specifically Henry VII)

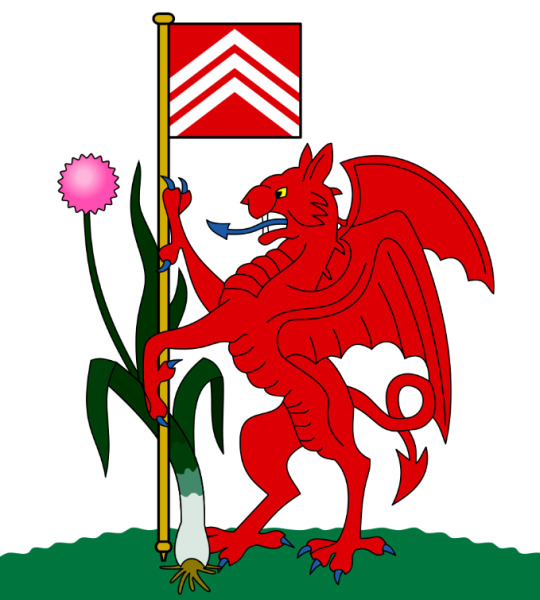

(Tudor dragon with pizzle) vs (dragon on the flag of Cardiff - pizzleless)

the penis is almost always included. So much to the point that the present royal family still includes the penis. While pretty much 0 depictions of the dragon in Wales include a penis. So you could interpret this as the dragon is seen as male only by the British royal family and as female everywhere else (which kinda implies that at some point the Tudor dragon had an mtf transition in Wales and she keeps getting misgendered by the royal family every time she is depicted in (mostly) England).

So much to the point that in 1995 this pound coin was made by the Royal Mint featuring the pizzle on the dragon with all four feet touching the ground as opposed to standing up (passant rather than rampant).

But in Wales you'd be hard pressed to see a pizzled dragon anywhere. Ergo, we can only conclude Y Ddraig Goch is trans and she transitioned in Wales and keeps getting misgendered in England.

[note: This is mostly tongue in cheek - but I do think it's fun to extrapolate that the Welsh dragon is trans because of the differences in depiction between Wales and England. Like many things Welsh, it is misrepresented by England and the idea of the Welsh dragon being misgendered only in England is, I think, a good metaphor for a whole lot of English treatment of Wales.]

Unrelatedly, there is a gay Welsh flag held at the National Museum of Wales which has a very wonky dragon which I find very endearing.

(cleaned up version I made)

So much so I made it an emoji in my Welsh bilingual LGBTQIA+ Discord (requirements for joining are - be 16+, either speak or are learning Welsh and identify as LGBTQIA+ in some way. Dm for link!).

(triaist ti 'you tried' emoji)

~ Completely unrelatedly ~ never forget the time someone was trying to homophobic to me by suggesting that I was disrespecting all the soldiers who died 'for the Welsh flag' by making it rainbow colours and not red - arguing that any change of colour of the dragon was disrespectful. Reader, my bus pass at the time for Mid Wales Travel had a purple dragon on it.

#cymraeg#welsh#cymblr#cwiar#trawsryweddol#traws#trans#trans dragon#y ddraig goch#welsh dragon#welsh history#dragons#wyverns#last tag because technically Owain's golden dragon is technically a wyvern

717 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vocabulary - to want

A few different ways (that I know) to express wishes and desires.

eisiau - to want. One of the standard ways of saying you want something, all across Wales. In truth, it’s not actually a verbnoun like many others, it’s really a noun. That’s why you don’t need the ‘yn’ before it ad you would for any other verbnoun: ‘yn mynd’, ‘Dwi’n mynd’. ‘Dyn ni’n aros.’ Etc.

‘Dwi eisiau cysgu.’ I want to sleep.

I believe the reason for this is an older construction that is used in literary Welsh, but that got shortened and dropped off over time in colloquial Welsh. ‘bod ... ar [rhywun]’ was the construction used, roughly meaning to have ‘a want upon you’ (very roughly).

Double checking this with Wiktionary (beloved), they do have a credible literary source demonstrating this: the Welsh bible (which thanks to a frenzied linguistics and orthography-fuelled spiral down Wikipedia, and oddly enough, the Welsh comedian and radio broadcaster Elis James (unrelatedly), I know was first translated in the 1500s and directly led to the loss of the letter ‘k’ from the Welsh alphabet).

‘Yr Arglwydd yw fy Mugail; ni bydd eisiau arnaf.’ The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want.

Close enough to colloquial Welsh to understand, that's using ‘eisiau arna (i)’. Over time, colloquial Welsh has dropped the ‘ar’. The example sentence above could've been 'Dwi eisiau cysgu [arna i]'.

A note. Some people have a misconception that eisiau should cause a soft mutation in the word following it, because it is an exceptional case of an action (of sorts) that doesn’t need an ‘yn’, and so must follow a pattern similar to a few other conjugations out there like ‘dylu’ (should).

‘Dylet ti ddweud rhywbeth’ (You should say something), ‘Galla i wneud rhywbeth amdano fe’ (I can do something about it), ‘Ga i rywbeth?’ (Can I have something?), the past tenses of gwneud, ‘wnaethon ni ddysgu Cymraeg’, ‘Mae rhaid iddyn nhw dduhino’n gynnar!’ (They must wake up early!)

And so on. This isn’t the case, as eisiau is not a conjugated verb. It’s just a noun for desire! (*not exactly. I’m trying to explain this as best I can)

There is a south Walian usage of ‘eisiau’ that makes this idea clearer.

In some southern dialects, the construction ‘mae eisiau i…’ is used to mean that someone needs something. E.g. ‘Mae eisiau i ti fwyta’ means ‘you need to eat’. What it literally means is ‘there is a need for you to eat’, and so you can see the noun eisiau (a need) in use.

North Walian Welsh uses the same structure, but with the noun angen instead. ‘Mae angen i ti fwyta.’ ‘Mae angen iddyn nhw sosban’, literally, ‘they are in need of a saucepan’.

Speaking of dialect differences, especially in north Wales Welsh, you might come across spelling variants of eisiau: ‘isio’, ‘isia’, (N) ‘isie’ (S), ‘isho’, etc. Perks of a phonetic language are that nothing’s a misspelling really if it sounds alright when said out loud. I did raise an eyebrow at the last one a little, ‘sh’ isn’t the English ‘sh’ in Welsh, is it? (Is that Wenglish?)

Other forms!

moyn - to want. Used pretty much only in the south and valleys, but this one is a regular verbnoun. ‘Dwi’n moyn cwpla fy ngwaith gytre’n fuan’ (I want to finish my homework soon)

(Just realised there are a Lot of dialect words in that sentence! Cwpla -> gorffen, gytre -> cartef)

It seems simpler than the exceptional eisiau construction, why isn’t it more widely accepted?, you ask. (Most people I’ve said it to say it immediately places you geographically to them because they never hear anyone else say it.) It derives from an older verb, ymofyn, which itself comes from the word gofyn (to ask), ‘ym’ + ‘gofyn’ = ‘ymofyn’, which sort of goes away from the original idea of wanting, and into one of asking. Still, language evolves, and so you will still hear moyn in South Wales. In fact, the Say Something In Welsh course teaches it (which is how I know it. Probably worth giving a disclaimer that I’m simply mad about linguistics and Welsh alternative bands, before anyone starts to think I live in Wales just because I occasionally write long grammar posts!)

Awydd - a desire. Used similarly to eisiau, no ‘yn’ precedes it. The whole point of making this post was that I just came across this sentence: ‘Ti awydd mynd i Gastell Caerfili?’ Meaning, do you want to go to Caerphilly Castle?

And those are the ones I know!

#vocabulary#sentences#source: online#source: dictionary#source: wiktionary#welsh#Dysgu Cymraeg#to want#language learning#I've done my homework this time so i am going to put it in the relevant tags. I'm fairly sure this is all correct#Cymraeg#learn Welsh#languages#linguistics#language stuff#etymology

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's Friday, so I'm back working drive-thru at the Song-to-go delivery window! Come collect your weekly listen of songs to carry with you on your scroll!

If you're new, firstly, hi! Song-To-Go is a weekly song poll presenting you with new, lesser-known songs as a takeaway musical meal.

As always, choose songs based on the 30-second Spotify snippets if you don’t know them (and I try to make sure there’s always something you won’t know). If you like what you hear, go listen to the full songs, they’re yours* to carry along on your trip!

*as in add them to your library etc., if you like them a lot come ask me and I’ll try and dig up a Bandcamp like for you, hee hee

[last week’s poll, playlist of everything so far (in order) and more]

I started last week's poll a couple of days late, so that's still open right now (as all song polls are technically 'open' to being discovered, you can still reblog them, you just can't vote but I feel like most people reblog and tell me what they like anyway! Which I love :) )

Happy scrolling! This week, I've picked out a French (Montreal) album I've been obsessed with anticipating winter vibes, some classic rock 'n' roll, beauuuutiful Welsh pop harmonies, some London Asian fusion pop, futuristic electrofunk and because it's me, always some weirdo-post punk :)

Liked anything? Let me know in the tags! Tell your friends! Come back next week!

Happy listening!

#music#Song to go#<- that's the tag; if you check it on my blog every friday you should find a new poll!#music recs#rave#Montreal#London#underground#party#Song poll#Cymraeg#Welsh#alt rock#grunge#indie#indie rock#pop punk#emo#Fall Out Boy#post punk#Art rock#Song recs#80s post punk#new music#funk#electronic

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

everyone must go an watch the way on bbc right now!!

it's one of the best things i've seen in ages.

it's written and directed by welsh people. it's set and filmed largely in wales. it has a plethora of wonderful welsh actors and actresses. it's totally made by welsh people FOR welsh people.

i loved the pure welshness of it: the relations to the story of king arthur (orginally a welsh story); the feeling of hiraeth the whole time. i'm going to be thinking a lot about this mini-series for a very long time.

#it's so so so good#i'll never stop recommending or talking about it fr#escxelle#elle's interests hyperfixiations and shenanigans#the way#the way bbc#bbc the way#wales#cymru#welsh tv#hiraeth#<- adding the hiraeth tag to reclaim it back to being about wales#welsh#cymraeg#teledu cymraeg#king arthur#brenin arthur

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dw i’n dal meddwl y dylen ni gael cân yn y Gymraeg

The UK has multiple minority languages and I still think we should enter a song in Welsh, Cornish, or Gaelic. Not everything in English all of the time.

#eurovision#cymraeg#Welsh#Cornish#I said this last year and I still think so#elen’s eurovision tag#elen dysgu cymraeg

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

A PSA if you like

Hiraeth:

A Welsh term describing the grief, longing, and frustration felt by Welsh people over the loss and colonization of their language, culture, and identity. It is specific to Wales and should only be used by Welsh people.

I have a very intense experience of hiraeth. My grandfather is from South Wales and much of my family now live in West Wales. I feel genuine anger and frustration sometimes, because Welsh is not my first language and I don't live in Wales. I know maybe three or four words in Welsh. My great-grandmother married a Welsh man and when she had my grandad and his sisters, refused to have the Welsh language spoken in her home. This meant my grandad never learnt Welsh, or my mother, or me and my sister. This means that in the future I want to try to learn Welsh to reconnect with my Welsh heritage.

This word can be interpreted in many ways and my own definition may not be accurate to someone else's experience of hiraeth, but the main thing is the very last sentence. Please do not use this word unless you are Welsh, and only in the context of Wales. This is not a cute word to put on moodboards with pictures of flowers and fields.

My culture is not your aesthetic.

#wales#cymru#cymraeg#hiraeth#definition#psa#public service announcement#welsh culture#my culture is not your aesthetic#how is that not a tag

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

@liabegins tagged me for December receptify! Thank you so so much!!! Sending much love your way! 🩵 Sorry this is late - as usual!

This one had a few surprises on it (Black Betty?) - but yay bangars cymraeg!! Cymru, Lloegr a Llanrwst (Wales, England and Llanrwst) should have been higher tbh! Also beautiful stranger is my current WIP sterek meetcute song so that's why that's so high. It's been played on repeat a lot recently...

No pressure whatsoever tags to: @hellameyers @novemberhush @gege-wondering-around @seaweed-water

@patolemus @renmackree @novasillies @novasillies and @greyhavenisback

And anyone else who wants to!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

call me blods!! 20. she/they. lesbian.

i draw stuff. sunshipduo aficionado. aimsey historian. gtws fan club. eng/welsh speaker.

u can support me over on kofi! all info about comms is on my page and they are open!

pls credit if you use my art <3

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think the hardest part of learning multiple languages is that the definitions don’t overlap perfectly. So I was doing Greek and πειράζω comes up and I’m like “oh I know that it’s try or test” and then I switch to welsh and I get the word “ceisio” and I’m like “oh. Test.” Nope. It only means try in welsh.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Help I was just showing my dad some gifs I have saved (wolves and sharks) and then accidentally showed him a Howl’s moving castle one, and he said “hm? Who’s that?” and so I said “Oh, that’s Howl, he’s Welsh by the way!” and he responded in the heaviest Welsh accent: “Oh! He’s Howell is he?”

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

bore da draig. dw i'n hoffi bwyta menyn. ob dw i ddim yn hoffi bwyta pys. hilfe mich

#cymraeg#wales#ig its welsh now#is welsh tumblr a thing#the tags say yes#shitpost#language shitpost#pg 13: some german#deutscher blog#sorry german tumblr

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Rule Britannia is out of bounds" - How England invented Great Britain

("Rule Britannia is out of bounds"- Life on Mars, David Bowie, 1971)

As promised, here is a more in-depth exploration of Wales' relationship to indigeneity or colonised status. And how England created the (political) concept of Great Britain when it formally annexed Wales in 1542. This is a long post but I will try and be brief where possible to do so. I graduated with a degree in Celtic Studies last year from Aberystwyth University so it's time to put that to use.

In my last post, I went over the groundwork for this conversation - so if you haven't read that one yet I strongly suggest you read that one first then come back to this one. In that first post, I establish the stickiness in claiming or applying the status of colonised onto the modern nation and people of Wales. I also explore how claims of indigeneity (intended to legitimise Welsh nativism through dubious claims of descent from the Iron Age Britons) are weaponised in modern political contexts.

With all that said - how does one categorise the suffering of Wales/its culture and language without straying into the language of the colonised?

Early Medieval English Imperial desire for Wales:

Very often, you will hear people make the claim that Wales was 'England's first colony' and that the other nations bordering England were guinea pigs for Britain's later colonial empire. My previous writing on this topic has established the difficulty in applying colonised as a term to Wales and its context. Which leads to the question of what do we describe it as instead?

For this, we need to make a distinction between colonialism and imperialism.

The two concepts are very similar (and do overlap slightly) but they have crucial differences which allow us to be more precise and succinct with our wording which aids both communication of the subject and quells misunderstanding through language which doesn't fit the situation.

Put simply, Imperialism is when one country, people or nation desires to extend power over another (usually a close-by or neighbouring territory) - especially (but not solely) through the means of expansionism.

Colonialism is also when a country, people or nation wants to extend power over another - but primarily through invasion and typically (but not always) against territories that are further afield and not immediate neighbours).

A lot of the way in which we view early British history in Wales is tinged with a kind of exceptionalism for what happened between England and Wales. Very often, what was done is framed as uniquely terrible for the time and held up as a poster child for the unique evil of England's expansionist desires. Yet all over Europe at the same time this was happening - other European nations and peoples were engaging in the same subjugator-subjugatee relationship. The exceptionalism present in framing Wales as uniquely suffering in this period is, unfortunately, borne out of the same British imperial culture which was thrust upon it and has become irrevocably entwined with culturally. It is a kind of British arrogance (which ironically crops up in anti-British arguments in Welsh independence activism) which presupposes nobody could have suffered the same or worse than they have, which demands the active ignorance of other, contemporary examples of that which they claim to oppose.

Wales was the first victim of English (later British) Imperialism - not its first colonial victim.

The build-up to and annexation of Wales by England:

Wales was annexed twice - once before the age of states and once shortly before that age dawned. The concept of states (as in, sovereign countries) didn't really exist until after the Treaties of Westphalia (1648). In which the concept of non-interference in the religious affairs of other countries (and other domestic affairs) was established and international relations was born. This is relevant to Wales' situation - as what England did to Wales happened long before the age of states began.

There was the Conquest of Wales by Edward I between 1277 and 1283. (Before that, the Norman Conquest of Wales by 1081). (However, the latter being conducted by the Normans is not necessarily equatable to the actions of England the country, which itself had only just been invaded by the Normans). And then the Laws in Wales Acts which formally incorporated Wales into the realm of the Kingdom of England in 1542.

The Conquest of Wales by Edward I overran the territories of the last Prince of Wales (from the Welsh monarchic tradition), Llywelyn the Last and divided the territories into Welsh Principalities and Marcher Lordships. This setup remained until 1542, when Henry VIII passed the Laws in Wales Acts and formally annexed Wales and made it (in all the legal senses) a part of England.

By the time international relations was in its infancy (i.e. shortly after the Peace of Westphalia) Wales had been absorbed into England for just over 100 years. The relevancy of this is that Westphalia had been about religious liberty - Henry VIII's incorporation of Wales into the Kingdom of England was partly informed by religion. Henry VIII had just broken away from Rome and established the Protestant Church of England, whereas Wales was still largely Catholic. The Laws in Wales Acts also replaced the language of the courts in Wales with English, cutting off monolingual Welsh speakers from legal representation. The language of worship became English instead of Latin. Wales was culturally assimilated into England over a long period of time. And that meant ensuring Wales followed the 'correct' religion and spoke the 'correct' language. After the Peace of Westphalia, these actions by Henry VIII to bend Wales to his new religion and to assimilate Wales into England would have been in poor taste or decried in light of the new Westphalian system that was developing in Europe. Alas, these events took place before then and temporally speaking, Wales was locked out of this recourse.

By contrast, Scotland was unified with England into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707 (after the Peace of Westphalia). England committed numerous acts of cultural erosion and destruction against Wales and Scotland at this time - but its Union with Scotland differs to that with Wales. Wales was incorporated into England, whereas Scotland was 'invited' to join a union between England (which then included Wales) and itself. Simplifying it greatly - like a marriage proposal in which the two spouses are *supposed* to be equals. After the Act of Union with Scotland, the whole island of Great Britain was 'unified' and thus the Kingdom of Great Britain was formed from two states - England (inc. Wales) and Scotland into one state.

Welsh Nationalism and Nationhood as separate from Statehood:

Wales and Scotland were the victims of English imperialism in many similar, but also many different ways.

Wales, having never been a 'state' was unable to acquire this status since it had long been incorporated into England by the time the concept of states had developed. Wales was unlucky in this way, because other nations on this island such as Scotland had managed to establish themselves long enough to survive into the age of states and thus became one. Because of this, Welsh nationalism cannot look to an era in which it was a free state because that did not happen. Instead, Welsh nationalism very often looks back with rose-tinted spectacles to Wales prior to Edward I's conquest and/or prior to Henry VIII's Laws in Wales Acts.

But nationhood and statehood are not the same thing - and it is the conflation of these two concepts (like the conflation of colonialism and imperialism) which has led to much of the confusion on these topics. Nationhood is acquired by a group of people who share several of these things: a common language, history, culture and (usually) territory. Not all of these things are required, but most nations have all or almost all of these qualities. Wales has a language (Welsh), a common history, culture and territory (Wales). Statehood is acquired by an association of people who have most or all of these things: formal institutions of government, laws, permanent territorial boundaries and sovereignty. Wales before 1283 very loosely had government and laws (monarchy and Laws of Hywel Dda) but had no permanent territory due to the conquest and lost some sovereignty in 1283 and total sovereignty in 1542.

Even if Wales had met all the criteria for a state in 1283, it would not have been eligible to become one - no nation in the world was able to do that yet because the concept (or proto-concept) for it would only be invented in 1648. Even England did not qualify for state status yet. Put simply, Wales got very unlucky with history and geography in such a way which prevented it from having a historical statehood post-1648 like neighbouring England and Scotland.

Naturally, when Welsh nationalism attempts to recall a past in which it was a 'state' - it is always an imagined and romanticised history. A fantasied history which generates ideas of the persecuted 'indigenous' Cymro where it shouldn't really be (in all seriousness, the injustices inflicted upon Wales by England are enough - extra additional injustices reliant upon a claim to to 'nativeness' do not need to be invented in order to be taken seriously). In the modern world, claims of nativeness in a European context are fraught, misguided, in poor taste and often copy the homework of the indigenous peoples those same European powers marginalised or colonised. In the modern world, a white Welshman claiming indigeneity is doing so in a postcolonial world and there really is no escaping that. Succinctly - the Welsh nationalist who relies upon a created sense of nativeness can only do so by drawing upon the work of marginalised native peoples living in parts of the world formerly colonised by Great Britain. To claim native status as a Welshman is to misunderstand and misappropriate history while wielding the language of the genuinely colonised while contributing nothing to it. It is purely extractive and a slap in the face of non-European native peoples everywhere. The pining for this return* to a prior point in Wales' history where it was a fully functional, sovereign nation populated only by 'native' or 'indigenous' Cymry is an alarming and ahistorical fantasy that all too easily slides into ethnonationalism and nativism -ancient or modern.

(*the choice of the word 'return' here is no accident - the desire to 'return' is inextricably linked to the alt-right dogwhistle 'retvrn' and it it is frighteningly common to see elements of that subculture crop up in Welsh nationalist calls to return to a point in Wales' history where it was 'sovreign'.)

Welsh nationalism which isn't vigilant to this kind of thinking very often will find itself arguing blatant untruths. For example, on the milder side of fake history, I've come across Welsh nationalist groups claiming symbolism from Owain ap Gruffydd's coat of arms - despite the fact he lived before the age of heraldry and he never used these arms because they were attributed to him later.

What next for Wales after 1542?:

Since Wales was fully and formally incorporated into the Kingdom of England by 1542, English colonisation of the Americas prior to 1707 naturally included Welsh colonists as well as English colonists. After 1707 Scots joined in with the now British colonisation of the Americas (both as/for/on the side of the Brits and as Scots fleeing Scotland after the Act of Union decimated Scottish Gaelic traditional culture). The Welsh, on the other hand, were more intimately involved with the colonisation of the Americas before that.

Though England spearheaded its colonisation of the Americas, Wales was not an unwilling participant dragged along by its association with and incorporation into England - Welsh colonisation, like Scottish colonisation, was often motivated by religious or cultural persecution - of which colonisation of another land was a possible solution to cultural loss in their home countries. Pennsylvania was settled by many Welsh Quakers and the idea of a Welsh Tract was floated to the Welsh settlers in 1684. The idea was to create a county which would operate in the Welsh language and serve as a vehicle for the preservation of the Welsh language. This attempt was not as successful as Wales' colony in Patagonia, Argentina in which native populations there were displaced at the behest of the Argentinian government - who needed the land settled and cleared. Welsh colonists took up this mantle and created Y Wladfa colony there in 1865.

Returning to the 17th Century - Welsh people were active colonists in the Americas during this time - motivated by saving the Welsh language and freedom of religion (especially the developing Nonconformist denominations of Protestant Christianity developing at this time). It was not so much that England was forcing Wales to participate in its colonialism, but that Wales has its own wants and ends for colonialism and was motivated entirely on its own grounds.

Back at home, Wales was still hard-done-by due to England - but two things can be true at once. Wales was a victim of English imperialism, but was also a perpetrator itself of colonial violence against Native Americans. England was no such victim of imperialism of any kind and the power dynamic for England had always been one rooted in absolute expansionism.

Summary and Conclusion:

With all of that said - if you were to ask point blank if I feel it is appropriate or okay for Wales to claim it was colonised by England and that Welsh people are in some way, more indigenous to the island than any other people living here - my answer would be no, I don't think it's okay.

I can't stop people from thinking otherwise, but I can reason that perhaps we shouldn't appropriate the struggles of people marginalised by the very nation we are talking about in order to craft a victimhood which is entirely unnecessary. Wales was a victim of English imperialism - but Wales was also an active colonising European nation. In the modern world, people are thankfully more willing to listen to the wants and needs of victims of colonialism - particularly victims of British colonialism in the Americas, Oceania and Asia. But I would warn against Welsh nationalism which seeks to capitalise on that increase in indigenous visibility in order to add legitimacy to itself (necessitating the crafting of an 'indigenous' narrative which did not exist there before). We live in the modern world where indigenous peoples are being taken more seriously than in centuries past - but that does not mean the only peoples hard-done by being taken seriously are colonised indigenous populations.

I believe it comes from a deep seated insecurity within Wales in which it is not uncommon to feel like Wales is being left behind because of all of this advancement. And this insecurity manifests as rejection of anything not obviously Welsh or demonstrably 'home-grown'. It's the national equivalent of a survival mechanism - but this is detrimental not only to the cause of Welsh nationalism, but to Wales itself. I've had people say to me (and I have read in historical sources from the last 100 years in Welsh) that the LGBTQ+ movement is actually an English invention created to erode Welsh traditional culture. Or variations on that rhetoric in which it is immigrants or other minorities which are made into this boogeyman come to destroy Wales and all Welsh ways of life. And it is so demonstrably not true but also bitter to see from the hearts and minds of my fellow Welsh speakers/Welsh people. Who have been hurt so much by the historical erosion of their culture that they confuse non-threats for threats and can only resolve to obtain some more legitimacy by appropriating the language of nativeness and colonisation in this ever changing world which, right now, is listening to native peoples for once.

It's difficult to put into words, even with all of the background knowledge above - but Wales is valuable and legitimate all on its own and doesn't need to rely upon things which isn't serving it - like ethnonationalism and nativism.

I want to live in a Wales which is uncompromising not only in its own fight for recognition and respect - but for other nations and peoples' fights for the same as well. I want to live in an independent Wales which is an ally to all those who share Wales' struggle and a Wales which rights the wrongs of its past without hesitation or compromise.

Would you rather a Wales for the few or a Wales for all who call it home?

#cymraeg#welsh#wales#cymru#ethnonationalism#cymblr#nativism#indigenous#native#indigeneity#nativeness#tags for relevance#celtic nations#celticist#I know there's so many more things I could say or could add but this post is so long already#granted it's evidence this conversation sorely needs to happen#so if you have any additions or thoughts please reblog or reply in the tags#and reblog this post so that more people have a chance to read it#diolch pawb#long post

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grammar - conjugations

Just trying to remember a couple of conjugations that sound close together that I sometimes mix up.

One is the future form of gwneud:

Gwneud - to make/do//auxiliary verb

Gwna(f) i - I will (do/make) Gwnei di - you will [sing., informal] Gwnaiff e/hi/etc. - He/she/it/etc. will Gwnawn ni - we will Gwnewch chi - you will [pl./sing formal] Gwnân nhw - they will

In a pattern repeated across a few other forms, the negative and interrogative forms have a soft mutation on the first letter g, dropping it.

So ‘Will you...?’ becomes ‘Wnei di...?’, and ‘No, I won't...’ becomes ‘Na wnaf, wna i ddim...’

(The f at the end of wna is optional, there are a number of patterns where it may stay or be dropped entirely. Adre(f) -> home, bydda(f) -> I will (plain old future of 'bod').)

Wnei di'r gwely? Will you make the bed? Wna i ddim y darlun. I will not make the painting. Na wnân, wnân nhw ddim byd heddiw. No, they will not do anything today. Gwna i bopeth yn iawn. I will make everything okay.

Another is the conjugation of cael asking for permission

Cael - to get, obtain, be allowed to do/have something. (It's a versatile verb).

In the present tense, in non-literary Welsh, you would just use the auxiliary 'bod' as per usual, ‘dwi'n cael’, ‘rwyt ti'n cael’, etc. In using its future and conditional tenses, it amounts specifically to the connotation of asking and receiving permission. May I go? Can he stay? Will we be allowed to bring our own water bottles? Could I have one?

Future

Ca(f) i - I will/can get/have/am allowed/ Cei di - You ... [singular, informal] Ceith (N)/Caiff (S) e/hi/ac ati - He/she/it/etc. ... [3rd person sing.] Cawn ni - We ... Cewch chi - You [formal/plural] Cân nhw - They ...

*N/S are northern and south Walian dialect variants, but don't take anything as too set in stone. I'm not the authority on it, anyway.

Conditional

Cawn i - I could ... Caet ti - You [sing, informal] could Câi fe/hi/rhywun - [3rd person] could Caen ni - We could Caech chi - You [plural/formal] could Caen nhw - They could

The 'c' softens to 'g' when used in the interrogative, but the negative gets an aspirate mutation: 'c' -> 'ch'

Ga i fynd? May I go? Châi fe ddim aros. He could not wait. (Conditional, in the sense of 'there is no way that he could wait', rather than past tense, which would be 'chafodd e ddim aros'. Maybe the next sentence is a clearer example) Cawn i aros hwyr os caet ti gollwng fi adre yn dy gar. I could stay late if you could drop me in your car. Gawn ni ddod â'n poteli dwr ein hunain? Will we be allowed to bring our own water bottles? Cei, cei di un. Yes, you may have one. Na chaiff, chaiff hi ddim tocynnau i'r cyngerdd mor hwyr. No, she cannot/will not be able to get tickets to the concert this late.

#grammar#welsh#vocabulary#sentences#conjugations#gwneud#future tense#conditional tense#tenses#Cymraeg#A note that is also in my pinned but worth re-iterating: tagged 'sentences' means I made that shit up; I could be wrong on the sentences

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

Oi! Barn onest ar ganeuon Cymraeg? 🎤👀

///please I need more opinions help a poor boy out/// 😔🙏

uHHHM OKAY! Maen nhw'n araf ac yn ddiflas, dwi'n meddwl. Mae bron pob cân yn swnio fel y gallai fod yr anthem genedlaethol. Mae'n anodd dod o hyd mewsic da. Uhhh...ond mae cloriau Cymraeg o caneuon Saesneg dwi’n meddwl sy’n swnio’n hardd? Idk if that counts lol.

(Is this for the papur glas™ papur newydd again or smth else??)

#flamingtwig <3#my beloved friend#welsh post-its#siarad yn cymraeg#music opinion ig??#irl people stuff#idk what to tag this#lmao#thanks for the interview???

6 notes

·

View notes