#cosmati

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Henry III rebuilt Westminster Abbey and Rome sent the mosaic tiles

#Cosmati Pavement#Westminster Abbey#King Henry III#Rome#church mosaics#English cathedrals#Christendom#AD 1268

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cosmati Pavement - Westminster Abbey

0 notes

Text

Duomo di Orvieto, Umbria. A close-up of the spiral column adorned with geometric mosaic on the facade of the cathedral, cosmati technique.

186 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Anointing Screen

The Anointing Screen has been designed and produced for use at the most sacred moment of the Coronation, the Anointing of His Majesty The King. The screen combines traditional and contemporary sustainable embroidery practices to produce a design which speaks to His Majesty The King’s deep affection for the Commonwealth. The screen has been gifted for the occasion by the City of London Corporation and City Livery Companies.

The Anointing takes place before the investiture and crowning of His Majesty. The Dean of Westminster pours holy oil from the Ampulla into the Coronation Spoon, and the Archbishop of Canterbury anoints the Sovereign on the hands, chest and head. It has historically been regarded as a moment between the Sovereign and God, with a screen or canopy in place given the sanctity of the Anointing.

The Anointing Screen was designed by iconographer Aidan Hart and brought to life through both hand and digital embroidery, managed by the Royal School of Needlework. The central design takes the form of a tree which includes 56 representing the 56 member countries of the Commonwealth. The King’s cypher is positioned at the base of the tree, representing the Sovereign as servant of their people. The design has been selected personally by The King and is inspired by the stained-glass Sanctuary Window in the Chapel Royal at St James’s Palace, which was gifted by the Livery Companies to mark the Golden Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II in 2002.

The Anointing Screen is supported by a wooden pole framework, designed and created by Nick Gutfreund of the Worshipful Company of Carpenters. The oak wooden poles are made from a windblown tree from the Windsor Estate, which was originally planted by The Duke of Northumberland in 1765. The wooden poles have been limed and waxed, combining traditional craft skills with a contemporary finish.

At the top of the wooden poles are mounted two eagles, cast in bronze and gilded in gold leaf, giving the screens a total height of 2.6 metres and width of 2.2 metres. The form of an eagle has longstanding associations with Coronations. Eagles have appeared on previous Coronation Canopies, including the canopy used by Queen Elizabeth II in 1953. Equally, the Ampulla, which carries the Chrism oil used for anointing, is cast in the shape of an eagle.

The screen is three-sided, with the open side to face the High Altar in Westminster Abbey. The two sides of the screen feature a much simpler design with maroon fabric and a gold, blue and red cross inspired by the colours and patterning of the Cosmati Pavement at Westminster Abbey where the Anointing will take place. The crosses were also embroidered by the Royal School of Needlework’s studio team.

At the Coronation Service, the Anointing Screen will be held by service personnel from Regiments of the Household Division holding the Freedom of the City of London. The three sides of the screen will be borne by a Trooper and Guardsman from each of The Life Guards, Grenadier Guards, Coldstream Guards, Scots Guards, Irish Guards, and Welsh Guards.

The screen has been gifted for the Coronation by the City of London Corporation and participating Livery Companies, the City’s ancient and modern trade guilds. His Majesty The King is a keen advocate and supporter of the preservation of heritage craft skills, and the Anointing Screen project has been a collaboration of these specialists in traditional crafts, from those early in their careers to artisans with many years of experience.

The individual leaves have been embroidered by staff and students from the Royal School of Needlework, as well as members of the Worshipful Company of Broderers, Drapers and Weavers.

As well as heritage craft, contemporary skills and techniques have formed part of this unique collaboration. The outline of the tree has been created using digital machine embroidery by Digitek Embroidery. This machine embroidery was completed with sustainable thread, Madeira Sensa, made from 100% lyocell fibres.

The threads used by the Royal School of Needlework are from their famous ‘Wall of Wool’ and existing supplies that have been collated over the years through past projects and donations. The materials used to create the Anointing Screen have also been sourced sustainably from across the UK and other Commonwealth nations. The cloth is made of wool from Australia and New Zealand, woven and finished in UK mills.

The script used for the names of each Commonwealth country has been designed as modern and classical, inspired by both the Roman Trojan column letters and the work of Welsh calligrapher David Jones.

Also forming part of the Commonwealth tree are The King’s Cypher, decorative roses, angels and a scroll, which features the quote from Julian of Norwich (c. 1343-1416): ‘All shall be well and all manner of thing shall be well’.

This design has again been inspired by the Sanctuary Window in the Chapel Royal, St James’s Palace, created for Queen Elizabeth II’s Golden Jubilee in 2002. At the top of the screen is the sun, representing God, and birds including the dove of peace, which have all been hand embroidered by the Royal School of Needlework.

The dedication and blessing of the Anointing Screen took place earlier this week at the Chapel Royal, St James’s Palace, where it was officially received and blessed by the Sub-Dean and Domestic Chaplain to The King, Paul Wright, on behalf of The Royal Household.

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

Masterlist: Lesson Recommended Readings

Masterlist

BUY ME A COFFEE

✨Lucy E. Thompson, 'Vermeer's Curtain: Privacy, Slut-Shaming and Surveillance in "A Girl Reading a Letter", Survelliance & Society 2017 ✨Gregor Weber, 'Paths to Inner Values,' in Gregor Weber, Pieter Roelofs, and Taco Dibbits, Vermeer, (NewYork: Thames & Hudson, 2023) ✨Bernard Berenson on Masaccio, panel in National Gallery, 1907 ✨Giorgio Vadari, Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects (online translation published, 1912) ✨Marjorie Munsterberg, Writing about Art ✨Paul Binski, Westminster Abbey and the Plantagenets: Kingship and the Representation of Power, 1200-1400, 1955 ✨Toby Green, A Fistful of Shells: West Africa from the River of the Slave Trade to the Age of Revolution, 'Rivers of Cloth, Masks of Bronze: The Bights of Benin and Biafra', 2019

✨Pieter Roelofs, 'Girls with Pearls', extract from 'Vermeer's Tronies' in Gregor Weber, Pieter Roelofs, and Taco Dibbits, Vermeer, (NewYork: Thames and Hudson, 2023)

✨Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks (1986)

✨Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth (1963)

✨Decolonial/Postcolonial Voices

✨Honour, Hugh and Fleming, John. A World History of Art. London: Laurence King Publishing. 7th ed, 2005

✨The Painter of Modern Life, Charles Baudlaire, 1863 Part 2, Part 3 Other Quality

✨The Photographers Eye, John Szarkowski, 1966

✨Elkins, James. Stories of Art. London: Routledge, 2002

✨Paragraphs on Conceptual Art, Sol Lewitt, 1967

✨Nikolaus Pevsner, The Buildings of England. London, volume 1, The Cities of London and Westminster, 1973

✨Annie E. Coombes, Reinventing Africa: Museums, Material Culture and Popular Imagination in Late Victorian and Edwardian England, 'Material Vulture at the Crossroads of Knowledge: The Case of the Benin "Bronzes", 1994

✨Hatt, Michael and Klonk, Charlotte, Art History: A Critical Introduction to its Methods, 2006

✨Meyer Schapiro, H. W. Janson and E. H. Gombrich, ‘Criteria of Periodization in the History of European Art’, New Literary History, 1970 ✨Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann, ‘Periodization and its Discontents’, Journal of Art Historiography, 2010

✨Kathryn Wysocki Gunsch, The Benin Plaques: A 16th Century Imperial Monument, 2018

✨D'Alleva, Anne. How to Write Art History. London: Lawrence King Publishing, 2010/2013/2015

✨Christopher Wilson, The Gothic Cathedral: the Architecture of the Great Church, 1130 - 1530, 1990

✨Anne D'Alleva, Methods and Theories of Art History, 2005/2012

✨Jonathan Alexander and Paul Binski (eds.), Age of Chivalry: Art in Plantagenet England, 1200-1400, 1987 ✨Paul Binski, Ann Massing, and Marie Louise Sauerberg (eds.), The Westminster Retable: History, Technique, Conservation, 2009

✨Christa Gardner von Teuffel, ‘Masaccio and the Pisa Altarpiece: A New Approach’, Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen, 1977 Part 2

✨John Shearman, ‘Masaccio’s Pisa Altar-Piece: An Alternative Reconstruction’, The Burlington Magazine, 1966

✨Kathryn Wysocki Gunsch, ‘Art and/or Ethnographica?: The Reception of Benin Works from1897–1935’, African Arts, 2013

✨Eliot Wooldridge Rowlands, Masaccio: Saint Andrew and the Pisa altarpiece, 2003

✨Svetlana Alpers, The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century, 1983

✨Clementine Deliss, Metabolic Museum 2020 ✨Laura Sangha, ‘On Periodisation: Or what’s the best way to chop history into bits’, The Many Headed Monster, 2016 ✨A Gangatharan, ‘The Problem of Periodization in History’, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 2008

✨McHam, Sarah Blake, "Donatello's Bronze David and Judith as Metaphors of Medici Rule in Florence," Art Bulletin, 2001

✨Eve Borsook, ‘A Note on Masaccio in Pisa’, The Burlington Magazine, 1961

✨Gombrich, E.H. The Story of Art, London: Phaidon Press Ltd, numerous editions

✨Paul Binski, 'The Cosmati at Westminster and the English Court Style', The Art Bulletin 72, 1990

✨Lindy Grant and Richard Mortimer (eds.), Westminster Abbey: The Cosmati Pavements, 2002

✨Peter Draper, The Formation of English Gothic: Architecture and Identity, 2006

✨Paul Crossley, ‘English Gothic Architecture’, in Jonathan Alexander and Paul Binski (eds.), Age of Chivalry: Art in Plantagenet England, 1200-1400, 1987

✨James H. Beck, Masaccio: The Documents, 1978 ✨R. A. Donkin, Beyond Price: Pearls and Pearl-Fishing: Origins to the Age of Discoveries, 1998

✨Nanette Salomon, ‘From Sexuality to Civility: Vermeer’s Women’, National Gallery of Art, Studies in the History of Art, 1998

✨Irene Cieraad, ‘Rocking the Cradle of Dutch Domesticity: A Radical Reinterpretation of Seventeenth-Century “Homescapes” 1’, Home Cultures, 2019

✨Walter D. Mignolo, ‘Delinking: The rhetoric of modernity, the logic of colonility and the grammar of de-coloniality’ in culture studies (2000)

✨H. Perry Chapman, ‘Women in Vermeer’s home: Mimesis and ideation’, Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek,2000

✨Christopher Wilson, ‘The English Response to French Gothic Architecture, c. 1200-1350’, in Jonathan Alexander and Paul Binski (eds.), Age of Chivalry: Art in Plantagenet England, 1200-1400, 1987

✨Johann Joachim Wicklemann (1717 - 1768) from Reflections on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture

✨Antonie Cotpel (1661-1722) on the grand manner, from 'On the Aesthetic of the Painter'

✨Andre Felibien (1619-1695) Preface to Seven Conferences

✨Charles Le Burn (1619-1690) 'First Confrence'

✨Various Authors (Reviews) on Manet's Olympia

✨Zionism and its Religious Critics in fin-de-siecle Vienna, Robert S. Wistrich, 1996

✨Sex, Lies and Decoation: Adolf Loos and Gustav Klimt, Beatriz Colomina, 2010

✨Women Writers and Artists in Fin-de-Siecle Vienna, Helga H. Harriman, 1993

✨Fashion and Feminism in "Fin de Siecle" Vienna, Mary L. Wagner, 1989-1990

✨5 Eros and Thanatos in Fin-de-Siecle Vienna, Sigmund Freud, Otto Weininger, Arthur Schitzler, 2016

✨Recent Scholarship on Vienna's "Golden Age", Gustav Klimt, and Egon Schiele, Reinhold Heller, 1977

✨Maternity and Sexulaity in the 1890s, Wendy Slatkin, 1980

✨Andre Breton (1896 - 1957) and Leon Trotsky (1879 - 1940) 'Towards a Free Revolutionary Art'

✨Sergei Tretyakov (1892 - 1939) 'We Are Searching' and 'We Raise the Alarm'

✨George Grosz (1893 - 1959) and Weiland Herzfeld (1896 - 1988) 'Art is in Danger'

✨Paul Gaugin (1848 - 1903) from three letters written before leaving for Polynesia

✨Siegfried Kracauer (1889 - 1966) from 'The Mass Ornament'

✨Victor Fournel (1829 - 1894) 'The Art of Flanerie'

✨Various Author's (Reviews) on Mante's Olympia

✨Rosalind Krauss (b. 1940) 'A View of Modernism'

✨Clement Greenberg (1909 - 1994) 'Modernist Painting'

✨Clive Bell (1881 - 1964) 'The Aesthetic Hypothesis'

✨Catherine Grant and Dorothy Price, 'Decolonizing Art History', Art History 43:1 (2020), pp.8-66.

✨Terry Smith (b. 1944) from 'What Is Contemporary Art?'

✨Geeta Kapur (b. 1943) 'Contemporary Cultural Practice: Some Polemical Categories'

✨Chin-Tao Wu 'Biennials Without Borders?'

✨Edouard Glissant (1928 - 2011) 'Creolisation and the Americas'

✨Rasheed Araeen (b. 1935) 'Why Third Text?'

✨Lisa G. Corrin, Mining the Museum: An Installation Confronting History, 1992

✨Fred Wilson, Mining the Museum, 1992

✨Tonny Bennett, The Birth of the Museum, 1995

✨Marina Tyquiengco, Book Review: Metabolic Museum, 2021

✨Hanna Daisy Foster, What is a Metabolic Museum? 2022 - 23

✨Anna Tihanyi, The Museum as a Body, Review: Metabolic Museum, 2022

✨A > Art in A to Z, Jens Hoffman, 2014

#art hitory#art tag#essay#paintings#art exhibition#art show#writing#artwork#art#art gallery#masterlist#writing tings#creative writing#personal essay#essential#essay writing#literacy#academic writing#critical thinking#on writing#art history#artists#illustration#art style#drawing#illlustration#architecture

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The artists whom Anne is known to have patronised include Holbein. Ives’s reading of the much discussed painting The Ambassadors links it exactly with her recognition as queen and with her coronation. The figures of Jean de Dinteville and George de Selve are shown standing not on a carpet but on a distinctive cosmati pavement. The only example of such a pavement in England was the floor of the sanctuary in Westminster Abbey, where Anne was anointed, witnessed by Dinteville, who was wearing, Ives suggests, the very costume in which he was painted.

La Bolaing, Patrick Collinson

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

ARTonWORLD - Presentazione del Volume "Digital Cosmati"

ArtonWorld nella collana Le Perle, è lieta di annunciare la presentazione del volume “Digital Cosmati: Arte e Scienza della Frattalizzazione”, scritto in collaborazione con i professori Pietro Pantano, Eleonora Bilotta e Francesca Bertacchini. Il libro esplora lo studio scientifico e matematico della trasposizione digitale degli antichi pavimenti Cosmateschi, unendo arte, tecnologia e scienza in…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

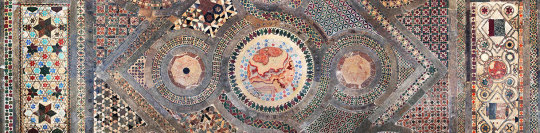

~ "The unique Cosmati pavement in front of the High Altar of Westminster Abbey. The complexity and subtlety of the design and workmanship can be seen nowhere else on this scale. It was laid down in 1268 during the reign of King Henry III. The great pavement is 24 feet 10 inches (7.58 m.) square, with dimensions calculated in Roman feet and consists of geometrical patterns built up from pieces of stone of different colours and sizes cut into a variety of shapes: triangles, squares, circles, rectangles and many others. The central roundel is made of onyx and the pavement also includes purple porphyry, green serpentine and yellow limestone. Also part of the original material are pieces of opaque coloured glass – red, turquoise, cobalt blue and bluish white. It lies on a bed of dark limestone known as Purbeck marble." ~

1 note

·

View note

Text

Fabio Barry, Painting in Stone (2020)

I’ve not been as blown away by an art book since I read Michael Baxandall’s Limewood Sculpturors of Renaissance Germany in opening my eyes to a whole new way of thinking about art. Not only is Painting in Stone the most beautiful book imaginable, it has so many things to say about the mystical and symbolic associations of the materials used to build sculptures and buildings, and the ways these were also translated into works of painted renaissance art. Here are a few of the buildings, objects and paintings included in the book, but there are many many more!

Chalice of Abbot Suger of St. Denis, 1st of 2nd century BC/11th-12th century, National Gallery of Art, Washington

Lorsch Gospels, c. 810

Aachen, Cosmati pavement, similar to the one at Westminster Abbey.

Fra Angelico, Annunciation, 1425-6, Prado, Madrid

Barry describes the marble floor depicted here as marble on a 'primordial plane' a liquid or vapour on the point of solidifying, the 'melting pot of matter in the divine mind before it was separated into created substances'

Giovanni Bellini, Lochis Madonna, c. 1475, Accademia Carrara, Bergamo

My students asked me what my favourite piece of renaissance architecture was. I don't have a favourite, but having been reading Barry's book, I had to pick the church of Maria dei Miracoli (1481-7) which came across unexpectedly on my last visit to Venice. Its a little jewel.

Plan of the marble floor of St Marco, Venice, by Angelo Visentini, 1761, Museo Correra, Venice

Tomb of St Cecilia, Rome, 1599-1603 - she is depicted shining with the light of immortality in pure white Pentelic marble, supposedly in the position she was found in.

0 notes

Text

CHIESE DEL TERRITORIO DEDICATE ALLA MADONNA DEL CARMINE

La Chiesa conventuale di Santa Maria del Carmine di Civita Castellana (VT) è ubicata in Via Vincenzo Ferretti, 161. Un tempo era denominata Chiesa di Santa Maria dell'Arco, perché per entrare al suo interno, secondo la tradizione, occorreva attraversare un arco, oggi inesistente. Datata tra l'VIII e il IX secolo, fu costruita quando la popolazione abbandonò Falerii Novi per tornare ad abitare il borgo, allora chiamato Massa Castellana. Sembra che venne utilizzata come cattedrale ancor prima del Duomo dei Cosmati. La Chiesa oggi è gestita dalle suore di clausura che vivono nel convento di fianco, nel quale dispongono di convitto e posti letto. Interessante poi è il campanile che consta di tre ordini di bifore, l'ultimo dei quali posa su colonne di marmo, le altre invece su pilastri, ed è fatto con diversi tipi di cortina: laterizi e mattoni.

Per saperne di più: https://edicoladelcarmine.suasa.it/CivitaCastellana.html

Per aggiungere informazioni: [email protected]

0 notes

Text

Cosmaty is a leading Wholesale and retail supplier of skin care products. From skin whitening products to fair cosmetics and night creams, we deal in almost every variety of personal care beauty products that will make you look younger for longer.

0 notes

Text

Lecture Notes MON 29th JAN

Masterlist

BUY ME A COFFEE

The Artwork in History: ‘Early Modern’ Art

What is ‘Early Modern’ Art? Well, it’s mostly an umbrella term for a lot of art, it can refer to the renaissance, and is sometimes associated with it. The Renaissance is a loaded term, especially when linked to culture and belief. So, some prefer to use ‘early modern’ as a term to describe it.

Let’s unpack ‘Early Modern’. ‘Modern’ we usually consider it to be closer to us? Another loaded term really. Because what is modernity? So, for art that is closer to us, we use the term contemporary rather than modern, since modernism is also a movement in art history, and there’s historical modern too.

One of the things modern may be: (depending on who) Just after the Renaissance or even the Renaissance. We usually limit ourselves in chronological thinking when it comes to Art History, although timelines are very helpful when it comes to understanding what influences what. What happens outside of Italy helps establish a vague name for the other art that is happening.

Jan Van Eyck is one of these painters, as he dates and signed all of his works (Van Eyck was here, was his signature). This means that his work is well documented for the time. His work was done during the same century as Renaissance Italy and the Masaccio panel, in reference to my previous lesson.

The Renaissance is a term that mostly refers to Italy during the 14th century and cannot entirely be applied to Eyck. That is where the term ‘Northern Renaissance’ comes in, attempting to mostly cash in on the cultural value of the term Renaissance. Another annoying term.

Jan van Eyck (d. 1441) Arnolfini double portrait, 1434 oil on panel, 82 x 59.5 cm National Gallery.

Why would this painting be modern?

Well, it’s non-religious for a start, it has directional lighting with cast shadows and perspective. Especially the mirror. Although the way Van Eyck’s script is written for his signature is more in the gothic style than humanitarian script.

Linseed oil and nut oils with pigment were used to paint this work, olive oil is not an option for painting with as it never dries. Linseed oil is translucent despite the natural pigments added. The detail of carpentry carving in beams next to the mirror, as well as the lustre on the brass chandelier.

To achieve this gradient of shadow and shade, you’d layer a base colour and then adding white to a layer you add light, here adding transparent glaze achieves shadow, rather than adding dark pigment. As light has more layers to pass through, so this creates the darker effect, we know this from x-rays of the painting. The vividness of this painting is achieved through the naturalistic colour palette. How artists at the time developed this, is still largely unknown but we have reason to believe historically, that some of their knowledge would’ve come from Arabic/Middle Eastern discoveries of light’s effect on the eye and colour.

Oil painting predates the Renaissance, it just becomes popular during this time.

The aforementioned convex mirror with great distortion, but still reflective and showing the artist. Can be linked to/associated with ‘modern art’ as self-awareness is an association of it.

Martin Kemp (who has a technological application interest and used it on Eyck’s work): if you tale what’s in the mirror you actually get a better/more accurate perspective than what you have un the main body of the painting. Vanishing points (as studied with computer tech).

Vasari knew Michelangelo told people to value and like this artwork at the time, so it’s been popular throughout history.

Bramante, ‘Tempietto’, c.1502, San Pietro in Montorio, Rome

‘Tempietto’ meaning little temple. Noticing the floor, it is similar to the cosmati pavement in Westminster Abbey, it appears as convincing Antiquity but is definitely Medieval. This complicate what the Renaissance is and Antiquity.

Northern Artists begin going/taking inspiration from Italy.

A Northern European artist in Italy: Dürer, Feast of the Rose Garlands, 1506 oil on poplar, 162 x 194.5 cm, Národní Galerie, Prague

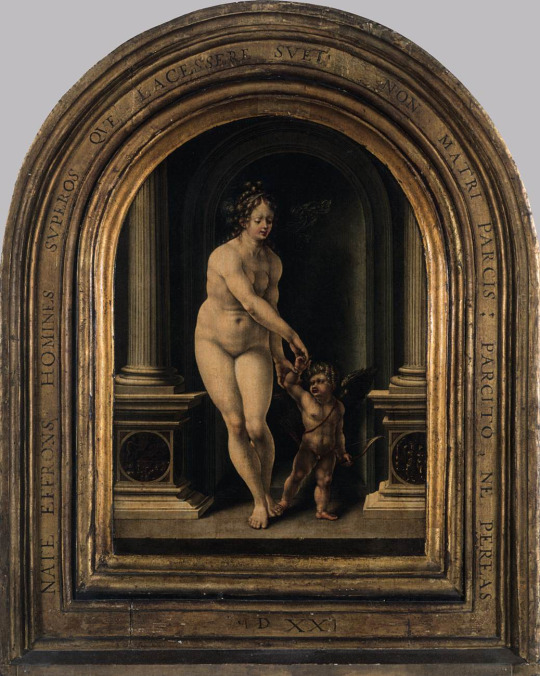

Van Eyck traditionally begins to blend with Italian Gossaert. Going from the Netherlands to Italy These Motifs of gods spread all across Europe.

Jan Gossaert, Venus and Cupid, 1521, oil on panel, 32 x 24 cm Brussels

And Religion gets complicated. The Reformation, which impacts the visual arts. The Protestant Reformation was a religious reform movement that swept through Europe in the 1500s. It resulted in the creation of a branch of Christianity called Protestantism, a name used collectively to refer to the many religious groups that separated from the Roman Catholic Church due to differences in doctrine.

Marin Luther, a very religious celibate, who published a doctrine for the reformation, has a portrait with his wife.

Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553) Portrait depicts Martin Luther and Katharina von Bora, 1529 Darmstadt

Cranach works closely with Luther in publishing propaganda and painting, he generally was an interesting historical figure.

Religious and political frameworks for the visual arts begin breaking down. Henry VIII takes ownership of all the churches land.

While the visual arts may not actually be effected to such an extent of what to paint/create, they are effected, in a different way. Iconoclastic was something that came from the reformation due to protestant belief centring around icons being removed, that you should worship without the need of icons. Especially in Northern Europe a lot of icons and images are smashed – coming from the more extreme views of no icons. In the Netherlands there is a large riot and smashing of icons:

Iconoclasm depicted: Frans Hogenberg, The Iconoclastic Riot of 20 August 1566 Engraving from Michael Aitsinger, De Leone Belgico, 1588

Iconoclasm in practice: Polychrome stone altarpiece Burial chapel of Jan van Arkel, c1500 Utrecht Cathedral.

As well as reconfiguring some Medieval churches:

Iconoclasm in practice: Interior of the church in Noordwijk aan Zee, Netherlands

This religious/political change around (mainly) Europe, disturbs the continuity of Church Art and the Visual Arts. This also actually breaks the entire art market at the time.

Holbein during this time comes to England for work. One of these portraits is of Erasmus, a very famous and one of the most important humanists of that time.

(Left) New emphases: Hans Holbein the Younger (1497-1543) Portrait of Sir Thomas More, 1527 (Right) Portrait of Erasmus, 1523 Oil on panel,74 x 59 cm, Frick, New York Oil on panel, 43 x 33 cm, Louvre

Around this time, comes Mannerism: a break in form and idealism. There are extensions in proportions and exaggerations. ‘Madonna with the long neck’/’swan neck’

‘Mannerism’ Parmigianino, Virgin and Child with Angels and St Jerome,1535- 40, oil on panel, 216 x 132 cm, Uffizi, Florence

Although mannerism can be summarised as a proportion change, it’s hard to put it into a box and explain exactly what mannerism is. Although it was also mostly an Italian insult, when referring to a work: to say it was not mannered/awkward.

However, mannerism also shows us how artists attempted something new and different.

Giulio Romano, East façade of the courtyard, Palazzo del Tè, Mantua, 1526-34

This also happened to architecture, although this façade looks to have tension and be slipping/sliding, this was done intentionally. At the time, only the sophisticated audiences would know and understand that these ‘faults’ are an intent and a joke.

Another twist that comes from the reformation: ‘Baroque’

And this title too is considered a bit of an insult, at least at the time it was. ‘Goth’ was also one of these. Baroque meant twisted and contorted. But despite this insulting title, this work was propagandistic and is considered one of the first global art styles due to mass colonisation during the time this style was popular.

‘Baroque’ Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Cornaro Chapel, 1652, Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome

Although this Caravaggio painting was well studied people still cannot determine or decide who St. Matthew is, out of all the men, it’s very ambiguous. As well as a little peculiar to depict saints and Jesus in a drinking scene, even if in the bible this is the setting, Caravaggio was a frequent visitor of drinking houses and enjoyed the drinking scene visually (pubs).

Caravaggio, The Calling of St Matthew,1599- 1600, oil on canvas, 322 x 340 cm, Contarelli chapel, San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome

Francesco Borromini, San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, Rome, 1638-41

Towards the end of this period, you have far less church art but still a large art ownership, especially in the Netherlands. There is a long tradition in Dutch Art for precise depiction, like in this landscape piece and still life. Although the still life succeeds in a secondary function, of depicting wealth through material goods: the Chinese porcelain, olives spilling out.

Jacob van Ruisdael, A Pool surrounded by Trees, and Two Sportsmen coursing a Hare, about 1665, oil on canvas, 107.5 x 143 cm, National Gallery

Willem Claesz. Heda, Still Life with a Lobster, 1650-9, oil on canvas,114 x 103cm, National Gallery

#art#artwork#art tag#writing#paintings#art show#art exhibition#essay#art gallery#artists#art history#historical#history#histoire#history lesson#lecture#learn#writers#writer#creative writing#academic writing#writeblr#writers on tumblr#writerscommunity#words#world#world politics#literacy#literature#dutch

1 note

·

View note

Text

Marble floor, St Vitale, Ravenna - very like the Cosmati pavement in Westminster Abbey

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The Cloister at Saint Paul’s Outside the Walls, Rome

#Rome#Roma#cloister#San Paolo fuori le mure#Saint Paul's Outside the Walls#mine#cosmatesque#Cosmati#architectural detail

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

HENRY COOK Civita Castellana Forte Sangallo e Ponte Clementino - 1840 - 30x45

#civitacastellana#civita#tuscia#italy#legrandtour#grandtour#viaggioinitalia#duomo#cosmati#cattedrale#forte#fortesangallo#fortezza#sangallo#ponteclementino#soratte#chiesa#borgia#landscape#henrycook

1 note

·

View note

Text

COSMATY BEAUTY PRODUCT

Cosmaty.in has the best beauty products and is considered to be the number one choice in the infirmary.

Cosmaty is a leading Wholesale and retail supplier of skin care products. From skin whitening products to fairness cosmetics and night creams, we deal in almost every variety of personal care beauty products that will make you look younger for longer.

With the guarantee of safety for long-term use, these personal care products can be consumed to make your skin shine with the glow of perfectio

Our journey began when we realized the gap in the availability of premium skincare products for urban women & men – they only like the best. Thus, when we decide to test our skin research expertise by creating formulations designed to meet the needs and concerns of women, we begin our journey.

https://cosmaty.in/skin-whitening-products-weight-loss-gain-product/

1 note

·

View note