#confucianism and daoism

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Avatar: The Last Airbender and Philosophy: Wisdom from Aang to Zuko by Johan De Smedt

Aaaa! I was so excited when I learned this book existed. As an amateur philosopher, it lived up to all my expectations and desires. Here is my review.

Avatar: The Last Airbender and Philosophy: Wisdom from Aang to Zuko by Johan De SmedtMy rating: 5 of 5 stars Aaaa! I was so excited when I learned this book existed. As an amateur philosopher, it lived up to all my expectations and desires.It covers so many different aspects of the show and teaches philosophical concepts through the lens of the characters and worldbuilding and considers them…

#Anarchist beliefs#Avatar aang#avatar last airbender toph#Avatar the last airbender#Avatar Uncle Iroh Tea#confucianism and daoism#How do I forgive myself#how to forgive when you are still angry#Iroh#Katara#last airbender toph#N.K. Valek Reviews#Nonfiction#The Last Airbender#toph

1 note

·

View note

Text

//.

#{get u a friend who will give u the summary of confucianism vs daoism and the history of their teachings in a long ramble of GOOD CUSH#when i say i love Vish's podcast i fckn love her podcasts}#{me driving to work like WOW I AM LEARNING A LOT ABOUT PIRACY}#{i am a hoe for this info#{it brings me the utmost joy in life}#{vish is actually the bestest best :3}#;;ooc

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism: Chinese Popular Religion | Crash Course Religions #12

A large proportion of Chinese people believe in a god—yet most report they don’t belong to any religion. In this episode of Crash Course Religions, we’ll learn about two of the Three Teachings of China—Confucianism and Daoism—and explore why Chinese religious practice is much more fluid than the question “What religion do you follow?”

#religion#chinese popular religion#confucianism#taoism#daoism#buddhism#chinese buddhism#china#religion 101#crash course religions#video#divinum-pacis#Youtube

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Confucianism, Daoism and Buddhism all contributed to the modern notion of gongsheng, which speaks to the conviction and the worldview of mutually embedded, co-existent and co-becoming entities. The notion of gongsheng, shaped by these traditions, behooves us to question the validity of the notion of an individual being as a self-contained and autonomous entity and reminds us of mutually embedding, co-existent and entangling planetary relations. It also inspires within us reverence and care toward creatures, plants and other co-inhabitants and even inorganic things in the natural surroundings.”

The Philosophy Of Co-Becoming

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 11 of the Hyakunin Isshu: Translating Ancient Japanese Poetry: Unraveling the Essence of Samurai Takamura

Today, we’re going fishing with Sangi Takamura (参議篁). So to speak… Twitter Patreon GitHub LinkedIn YouTube わたの原 (Wata no hara) – Across the open sea,八十島かけて (Yaso-shima kakete) – Spanning eighty islands,こぎ出ぬと (Kogi idenu to) – Rowing forth,人には告げよ (Hito ni wa tsugeyo) – Tell those whom you meet,あまのつり舟 (Ama no tsuribune) – The boat of fishermen from Ama. In translating Sangi Takamura’s poem,…

View On WordPress

#Art of Translation#buddhism#Confucian#Cultural Equivalence#daoism#Dynamic Equivalence#East Asian philosophy#japan#japanese#japanese poetry#Language Artistry#language studies#Lawrence Venuti#Linguistic Harmony#localizer#Multilingualism#philosophy#poet#poetic#poetics#Poetry#Preserving essence#Transcreation Approach#Translating Art#Translation Philosophy#translator#Translator Scholars#Translators Journey#Walter Benjamin

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watching people arguing about whether Easter and Christmas are actually pagan and then it spiraling into the three Abrahamic faiths bristling at each other, while I sit my Asian agnostic ass over here, like, *blinkblink*

#idk about you but we just mashed up daoism buddhism and confucianism and called it a day#tears falling like peridots#uhhhh happy spring holidays i guess

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

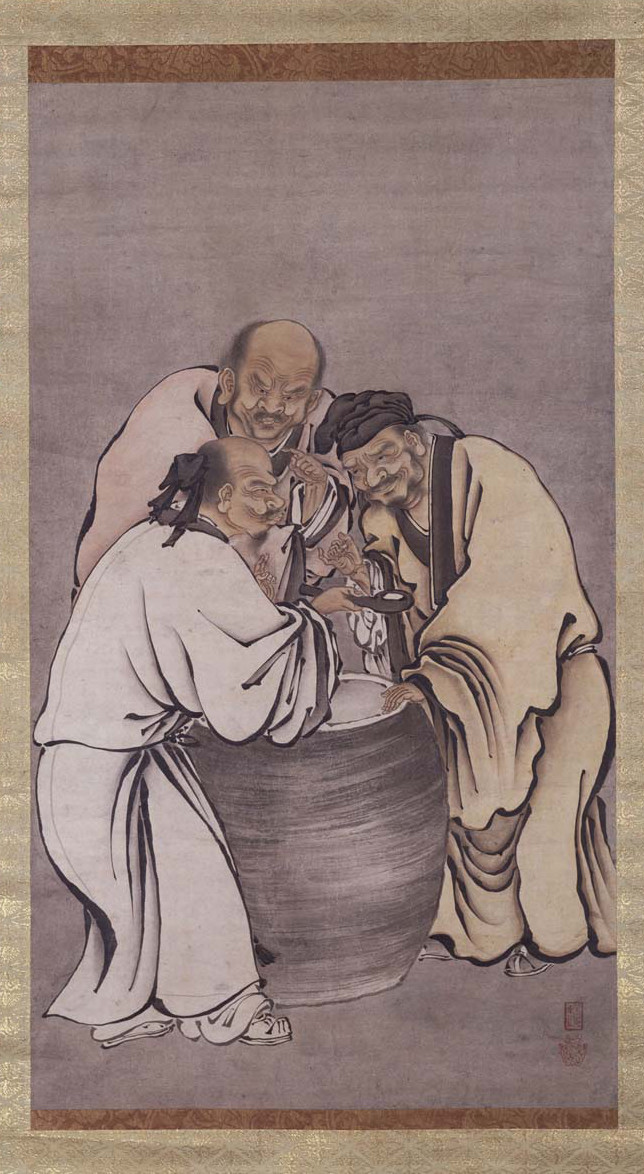

Same image

A Daoist priest flying over the water

#To explain in tags#The three vinegar tasters represents daoism Buddhism and confucianism with the daoist being the only one that finds the vinegar sweet#Since daoism alone of them regards mortal life as inherently enjoyable#And this seems borne out in a daoist priest having a rip roaring good time

14K notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Chinese New Year!

I wish you a Happy Chinese New Year! Year of the Snake The Essence of Chinese New Year: A Celebration of Renewal and Harmony Today marks the beginning of the Chinese New Year, also known as the Lunar New Year or Spring Festival (春节, Chūnjié)—a time of renewal, familial bonds, and deep cultural traditions that have endured for millennia. Rooted in the lunar calendar, this festival represents…

View On WordPress

#balance#China#Chinese Culture#Chinese New Year#Chinese Philosophy#Confucianism#Daoism#Harmony#health#impermanence#longevity#prosperity#Raffaello Palandri#renewal#self-reflection#Taoism#Year of the Snake

0 notes

Text

A Daoist Musing on the Reflections on Things at Hand 近思錄 3.5

Before I begin this, I find this passage as a way to ground and affirm the “supernatural” and “strange” in a way with what I believe to be in accordance with the Principle of Dao. Zhu Xi, and for the most part, the entirety of Neo-Confucian doctrine had a very nuanced belief about ghosts, spirits, and the Gods. Zhu Xi and Kongzi did believe in ghosts and spirits, however, their "existence" is a lot more rational and grounding. The Rujia school, from Kongzi to Zhu Xi seem to want to distance themselves from the "superstitious" aspects of the words 鬼 & 神, ghosts and spirits (and Gods) respectively. 鬼 & 神 are very real for Zhu Xi, but they are simply natural manifestations of Yin and Yang respectively. The mystical and faith-based beliefs and explanations of 鬼 & 神 are simply removed from the curriculum. This sort of rationalization of 鬼 & 神 is something I can appreciate and understand, and can ultimately confirm with my own experiences as well. However, I too, am faith-driven. There is an element of mysticism to the 鬼 & 神. I pray to the 鬼 & 神 of every budling and room I encounter. And not because a doctrine tells me this must be so, or because some superstitious ghost story led me to this practice. Rather, I've come to this practice via my own investigation of the Nature and Principle of ghosts, spirits, and the Gods (鬼 & 神). This is probably where I differ from the Rujia school of thought as proposed by Zhu Xi and all the thinkers found in the Reflections on Things At Hand (from here on out, referred to as Reflections). The following is a commentary on a Neo-Confucian passage through the lens of a student studying and practicing Daoism. I want to thank Yangzi (on Discord); whose @ on Twitter/X is MichaelMjfm, for helping clarify the nuances of the Neo-Confucian position of 鬼 & 神 to me. May the 鬼 & 神 bless you in every endeavor you embark on.

With that out of the way, let us look at this passage from the Reflections of Things at Hand 3.5 (here on out referred to as simply Reflections) along with comments from Chiang Yung:

People today believe in all kinds of supernatural things and strange tales simply because they do not clearly understand [universal] principle. If they try to understand principle in everything [that seems strange], when will there be an end? We must try to understand [universal principle] through learning.

Comments by Chiang Yung:

If we understand principle clearly, we can judge all supernatural things according to it. According to principle, some things are regular and others are not. Supernatural things need not seem strange to us. (Chiang Yung, Chin-ssu lu chi-chu, 3:1b)

This is an interesting statement to make. This comment that Zhu Xi includes makes it even more interesting. Albeit, one can derive a very secular interpretation from this. The comment by Chiang Yung makes me ponder…

There seems to be a kind very practical and grounding way to understand things that are “supernatural” in a way that makes them less “strange.” As per Kongzi Analects 3.12:

祭如在,祭神如神在。子曰:「吾不與祭,如不祭。」

The expression "sacrifice as though present" is taken to mean "sacrifice to the spirits as though the spirits are present." But the Master said: "If I myself do not participate in the sacrifice, it is as though I have not sacrificed at all." (tr. Roger T. Ames & Henry Rosemount Jr.)

Kongzi himself participated in things that may appear to the western mind as “strange.” But I purpose that Kongzi is actually investigating the nature of sacrificing to spirits (presumably ancestral ones in the context of Analects 3.12) through the Principle of Dao here in Analects 3.12.

Sacrificing to the spirits as though one were not present is what makes the whole ordeal of “sacrifice” strange. Behave as though the spirits are present…one’s sacrifice becomes ever real, ever “regular” as Chiang Yung might suggest. To sacrifice to the spirits as though they were fully present is to investigate the nature of sacrifice through Principle 理 -- the true reality of the thing being investigated. As Chiang Yung states: "According to Principle, some things are regular and some things are not. Supernatural things need not seem strange to us." If we take the time to investigate the "supernatural" and "strange" we begin to realize that everything labeled as "supernatural" and "strange" begins to fall apart. Self and other begin to fall apart. This is the Principle of the supernatural in one's practice. To begin to understand that ghosts, spirits, Gods, and the like are real in every sense of the word; now the "supernatural" becomes quite "natural." However, The "existence" and "non-existence" of the supernatural and strange and the natural and regular become obliterated too once investigating the Principle of this matter. To implore further about the "existence" or "non-existent" of what is regular or strange, supernatural or natural, is the reason why Dao and its Principle are diminished (Zhaungzi 2.12.4-5 tr. Richard J. Lynn). Do not become so overtly attached to the "realness" or "not realness" of the strange, the supernatural, and likewise the regular and natural. Trust in Dao with all your heart-mind and let yourself become absorbed within it All. I encourage anyone who reads this to read the Qingjing Jing, Humingjing, and Zhuangzi 2 to further elucidate the dissolution of these categories, as I am not qualified to speak any further on this.

So, my concluding comment to Reflections 3.5 and its comments by Chiang Yung:

Chapter 3.6 of the Reflections encourages us to investigate the “supernatural” and “strange” through the [universal] Principle [of Dao]. We do this by reading the ancients: Laozi & Kongzi; then the classics. The Daoist teacher then must teach the dizi 弟子 techniques of investigating the subtleties of the world away from the classics and books. The books teach you to crawl, then walk. They are your foundation.

With the foundation of the classics equipped; internalized within the dizi… the mysteries of Daoism then teach you to run into the “supernatural” and “strange” in order to shed these very dichotomies of “supernatural” and “strange.”

Although my understanding of “classics” here is very different from the Confucian tradition, I believe one must start with the Laozi. There are good arguments out there as to why this may be a bad idea, and they are good points to consider. However, I am a Daoist, so I make no excuse for my reasoning. The image below is a wonderful curriculum that one should diligently adhere to. Start with the Five Classics as listed in the picture below. The fifth is the Humingjing which I linked earlier in this post. Study them intently and intimately. Then read Zhu Xi and Kongzi, and if you wish, dip your toes into Confucian classic texts. After one deeply reads and reflects on the Five Classics and some Ruist literature, move on to the Four Books as listed below in the picture. This is my own curriculum and does not reflect the desired curriculum for the school of Daoism I'm training under (not initiated into, but simply training under).

#daoism#neoconfucian#philosophy#lao tzu#laozi#taoism#supernatural#ghost#spirits#confucius#confucianism#Kongzi#Zhu Xi

0 notes

Text

OKIE LES GET ITTTT

AP WORLD UNIT 1 PART 1

1 note

·

View note

Text

Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism: Chinese Popular Religion

youtube

#confucianism#buddhism#daoism#taoism#chinese popular religion#religion#spirituality#china#world history#Youtube

0 notes

Text

i do think it's interesting when ppl say things like lan zhan is autistic bc he stims with music (playing guqin) or all lans r autistic all jiangs r adhd like how winnie the pooh characters r all assigned diff mental illnesses but for clans. bc just as morality varies across time/place (even how 'the family' works across time/place - see everytjing abt whether madame yu is abusive, whether wwx is adopted or not, etc) it's fairly clear tht what counts as neuro-'divergence' differs based on norms. is it autistic for lan zhan to value family/ancestral rules + become distressed when his prev moral dichotomies r challenged or does he live somewhere in a time when filial piety was a whole thing etc. obviously the answer can be 'both'! but also autism Constructed As A Disability (& really the way Disability As A Construction has changed post civil rights act in the usa) is different from a character having autistic (as conceptialized in the 21st century) traits. was lan zhan Disabled socially, materially, etc, or did these traits factor into his high status? can u tell i am autistic by how much i'm writing about a topic that 99.999% of rhe world doesn't care anything about!

#i don't care whether u say he's autistic btw i think everyone should be autistic if they want to#BUT i think it's interesting to see 21st century traits of disability transposed onto ??st century wuxia characters#or for example eye contact in korea & nigeria works differently than in the usa wrt showing respect#but again to clarify autistic lan zhan is so real and my best friend#i'd bring up confucianism n daoism bc i feel like u can deffff see those things here but i don't think#i'm equipped to make any Definitive statements on that

1 note

·

View note

Text

So You Want to Read More about Chinese Mythos: a rough list of primary sources

"How/Where can I learn more about Chinese mythology?" is a question I saw a lot on other sites, back when I was venturing outside of Shenmo novel booksphere and into IRL folk religions + general mythos, but had rarely found satisfying answers.

As such, this is my attempt at writing something past me will find useful.

(Built into it is the assumption that you can read Chinese, which I only realized after writing the post. I try to amend for it by adding links to existing translations, as well as links to digitalized Chinese versions when there doesn't seem to be one.)

The thing about all mythologies and legends is that they are 1) complicated, and 2) are products of their times. As such, it is very important to specify the "when" and "wheres" and "what are you looking for" when answering a question as broad as this.

-Do you want one or more "books with an overarching story"?

In that case, Journey to the West and Investiture of the Gods (Fengshen Yanyi) serve as good starting points, made more accessible for general readers by the fact that they both had English translations——Anthony C. Yu's JTTW translation is very good, Gu Zhizhong's FSYY one, not so much.

Crucially, they are both Ming vernacular novels. Though they are fictional works that are not on the same level of "seriousness" as actual religious scriptures, these books still took inspiration from the popular religion of their times, at a point where the blending of the Three Teachings (Buddhism, Daoism, Confucianism) had become truly mainstream.

And for FSYY specifically, the book had a huge influence on subsequent popular worship because of its "pantheon-building" aspect, to the point of some Daoists actually putting characters from the novel into their temples.

(Vernacular novels + operas being a medium for the spread of popular worship and popular fictional characters eventually being worshipped IRL is a thing in Ming-Qing China. Meir Shahar has a paper that goes into detail about the relationship between the two.)

After that, if you want to read other Shenmo novels, works that are much less well-written but may be more reflective of Ming folk religions at the time, check out Journey to the North/South/East (named as such bc of what basically amounted to a Ming print house marketing strategy) too.

-Do you want to know about the priestly Daoist side of things, the "how the deities are organized and worshipped in a somewhat more formal setting" vs "how the stories are told"?

Though I won't recommend diving straight into the entire Daozang or Yunji Qiqian or some other books compiled in the Daoist text collections, I can think of a few "list of gods/immortals" type works, like Liexian Zhuan and Zhenling Weiye Tu.

Also, though it is much closer to the folk religion side than the organized Daoist side, the Yuan-Ming era Grand Compendium of the Three Religions' Deities, aka Sanjiao Soushen Daquan, is invaluable in understanding the origins and evolutions of certain popular deities.

(A quirk of historical Daoist scriptures is that they often come up with giant lists of gods that have never appeared in other prior texts, or enjoy any actual worship in temples.)

(The "organized/folk" divide is itself a dubious one, seeing how both state religion and "priestly" Daoism had channels to incorporate popular deities and practices into their systems. But if you are just looking at written materials, I feel like there is still a noticeable difference.)

Lastly, if you want to know more about Daoist immortal-hood and how to attain it: Ge Hong's Baopuzi (N & S. dynasty) and Zhonglv Chuandao Ji (late Tang/Five Dynasties) are both texts about external and internal alchemy with English translations.

-Do you want something older, more ancient, from Warring States and Qin-Han Era China?

Classics of Mountains and Seas, aka Shanhai Jing, is the way to go. It also reads like a bestiary-slash-fantastical cookbook, full of strange beasts, plants, kingdoms of unusual humanoids, and the occasional half-man, half-beast gods.

A later work, the Han-dynasty Huai Nan Zi, is an even denser read, being a collection of essays, but it's also where a lot of ancient legends like "Nvwa patches the sky" and "Chang'e steals the elixir of immortality" can be first found in bits and pieces.

Shenyi Jing might or might not be a Northern-Southern dynasties work masquerading as a Han one. It was written in a style that emulated the Classics of Mountains and Seas, and had some neat fantastic beasts and additional descriptions of gods/beasts mentioned in the previous 2 works.

-Do you have too much time on your hands, a willingness to get through lot of classical Chinese, and an obsession over yaoguais and ghosts?

Then it's time to flip open the encyclopedic folklore compendiums——Soushen Ji (N/S dynasty), You Yang Za Zu (Tang), Taiping Guangji (early Song), Yijian Zhi (Southern Song)...

Okay, to be honest, you probably can't read all of them from start to finish. I can't either. These aren't purely folklore compendiums, but giant encyclopedias collecting matters ranging from history and biography to medicine and geography, with specific sections on yaoguais, ghosts and "strange things that happened to someone".

As such, I recommend you only check the relevant sections and use the Full Text Search function well.

Pu Songling's Strange Tales from a Chinese Studios, aka Liaozhai Zhiyi, is in a similar vein, but a lot more entertaining and readable. Together with Yuewei Caotang Biji and Zi Buyu, they formed the "Big Three" of Qing dynasty folktale compendiums, all of which featured a lot of stories about fox spirits and ghosts.

Lastly...

The Yuan-Ming Zajus (a sort of folk opera) get an honorable mention. Apart from JTTW Zaju, an early, pre-novel version of the story that has very different characterization of SWK, there are also a few plays centered around Erlang (specifically, Zhao Erlang) and Nezha, such as "Erlang Drunkenly Shot the Demon-locking Mirror". Sadly, none of these had an English translation.

Because of the fragmented nature of Chinese mythos, you can always find some tidbits scattered inside history books like Zuo Zhuan or poetry collections like Qu Yuan's Chuci. Since they aren't really about mythology overall and are too numerous to cite, I do not include them in this post, but if you wanna go down even deeper in this already gigantic rabbit hole, it's a good thing to keep in mind.

#chinese mythology#chinese folklore#resources#mythology and folklore#journey to the west#investiture of the gods

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Notes: Philosophy

Philosophy - aims to ascertain basic existentialist truths of the world around us.

The term comes from “philosophia,” a word that has Greek and Latin origins.

Philosophers examine the nature of reality by posing philosophical questions or problems that they then attempt to solve through critical thinking.

Branches of Philosophy

Much of the value of philosophy lies in the specialization and categorization of philosophical questions that cannot be easily answered with empirical data or scientific knowledge.

Scholars organize such questions into different branches of thought, although there are perhaps as many ways of categorizing the different branches as there are scholars.

Here are just 3 of the potentially dozens of branches of philosophy:

Epistemology: Also called the theory of knowledge, this analytic philosophy studies the scope, validity, and extent of human knowledge—in other words, concepts surrounding how we can confirm what we think we know is true. Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason is an example of epistemology. In this work, Kant disagrees with philosopher David Hume, that our experiences and perceptions of things are subjective—therefore, our knowledge of things is not universal. Epistemology overlaps with many other branches of philosophy since human knowledge is relevant in other areas, such as the philosophy of language and the philosophy of mind.

Ethics: The moral philosophy of ethics is one of the oldest and broadest branches of philosophy. Ethics works to debate values of good and evil and questions where human actions fall on that spectrum. The ancient Greeks struggled with these questions as they developed their societies along two schools of thought—Stoicism and Epicureanism. Although these two schools, established in 300 BC, shared several tenets, they differed in describing the best way to live. Stoics believed that living a just and virtuous life was paramount, while Epicureans believed the search for pleasure should be the highest priority. Due to its broad nature, ethics is pervasive in nearly every academic discipline and overlaps within several other areas of thought, including the philosophy of history, the philosophy of law, and the philosophy of religion.

Metaphysics: The principles of metaphysics question our place in the world and the meaning of life and human existence. Metaphysics, like ethics, began as one of the main branches of philosophy in ancient Greece. One of the premier philosophical works that established the branch was Aristotle’s Physics. In exploring the working mechanics of our reality, Aristotle created foundations of thought that became important to western institutions and religions, like Christianity. Aristotle’s work greatly influenced the thirteenth-century Italian priest Thomas Aquinas, who utilized aspects of Aristotle’s philosophy of nature to confirm the existence of God as the omnipotent architect of the universe. Metaphysics often encompasses or overlaps with the philosophy of science—for example, as scientists grapple with questions related to humanity’s literal and figurative place in the universe.

Historical Figures of Eastern Philosophy

Learn how these notable eastern philosophers shaped their cultures with religion and philosophical breakthroughs throughout the history of philosophy:

Laozi (born circa 570 BCE): The historical existence of Laozi, or Lao Tzu, is disputed, but some believe the Chinese philosopher is the author of the Tao Te Ching, a manuscript central to the philosophical religion known as Daoism (or Taoism). The metaphysical and ethical philosophy promotes living in harmony with nature and doing no harm to others.

Confucius (551–479 BCE): The teachings of this Chinese philosopher and politician formulated the basic tenets of East Asian societies. Known as Confucianism, the Chinese philosophy encouraged family loyalty, ancestral appreciation, and education—concepts that remain important to modern Chinese traditions.

Siddhartha Gautama (born in fifth century BCE): Historians and academics dispute the facts of the life of Siddhartha Gautama, also known as the Buddha. By some traditions, he was born into an aristocratic family and enjoyed an entitled life until he decided to pursue a nomadic and ascetic lifestyle. Over time, people attributed teachings to him on self-restraint, meditation, and mindfulness—ideas that grew into a popular world religion.

Jalāl ad-Dīn Mohammad Rūmī (1207–1273): A thirteenth-century Persian poet, Jalāl ad-Dīn Mohammad Rūmī wrote Quranic verses and Sufi poems that scholars still translate and publish today. A large part of philosophy in Rumi’s poetry is his set of values around love and religion. His philosophy of life focused on using art and self-expression to bring humans closer to God.

Historical Figures of Western Philosophy

Ancient Greek philosophers established western philosophy as early as the sixth century BCE. Here are a handful of Greek philosophy figures who created theoretical foundations and frameworks that future generations could use to question their own complex societies:

Socrates (470–399 BCE): The Athenian philosopher Socrates is credited as the founding father of western philosophy and the Socratic method—a form of questioning that scholars in multiple areas of philosophy use to pinpoint shortcomings in logic or beliefs. His teachings were never published but lived on through the work of his student, Plato.

Plato (428/427–348/347 BCE): An influential thinker of the classical Greek period, Plato is famous for his theory of forms, which questions the connection between our minds and reality. He is also remembered for his several published works, like The Republic, which communicated his social and political philosophy.

Aristotle (384–322 BCE): The philosopher Aristotle was a star pupil of Plato’s (another ancient philosopher) and went on to found his own school, called Lyceum. During his career, Aristotle collected and simplified the philosophies of his predecessors and contributed to philosophical work in nearly every aspect of classical Greek culture. He was the first ancient philosopher to analyze the concept of free will.

René Descartes (1596–1650): A French mathematician and philosopher, René Descartes is best known for the existentialism theories he put forth in Discourse on the Method and his statement: “I think, therefore I am.” Descartes’ natural philosophy and metaphysical inquiries, as well as his thoughts on the existence of God, established him as a pioneer of modern philosophy.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831): German philosopher Georg Hegel is best known for his metaphysical concept known as idealism. The concept dictates that the perceptions of a self-conscious mind result in the most accurate interpretations of concrete objects. His work had a dramatic impact on western philosophy in the twentieth century and influenced the works of philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Nietzsche.

Source ⚜ More: Notes & References ⚜ Writing Resources PDFs

#philosophy#writing notes#studyblr#writeblr#dark academia#writing reference#writing inspiration#worldbuilding#literature#writers on tumblr#writing prompt#spilled ink#history#creative writing#writing ideas#light academia#ivan kramskoy#writing resources

120 notes

·

View notes

Note

As someone who’s Chinese w/ a degree in social science + (art) history regarding East Asia I’m always super intrigued and interested to how others interpret changes in new titles on older religious texts- but I will ask in particular if you have any personal ties to Buddhism/Taoism/Confucianism (and Chinese culture) when you find yourself interpreting BM:W’s change in allegorical use of Buddhism as contemporary political adherence! BM:W’s religious and soul mechanics follows their previous game without much overt linking between the two.

Overthrowing Gods in East Asian media is a very common trope in videos specifically due to player involvement (contrast to books where you are separate as the audience) and often is used as an allegory for the system/recent events we exist in. In such it does shift a lot from the original text in base but I think it’s not supposed to relay the same allegory due to the time period in which the writers exist! Wukong’s story changing to him still being chained by the principles that envelop life is far more relatable to late-stage capitalist environments viewers and artists exist in- as such he fulfils the contemporary variant of his original role in JTTW!

I think the change in purpose the Buddhist mythos serves in this game is decisive by nature due to inherent bias present in the original text as a religious piece, and such is core to the allegory. However I don’t think BM:W is supposed to relay that allegory, I think it is supposed to branch off on its own as an alternate contemporary extension of the foundation JTTW set out (plus with the 2 DLC’s on the way, there is plenty of time to extend the universe in game to validate a shift in religious purpose compared to the cut 7 chapters planned during development). And such i think attributing it to the CCP can be a bit of a touchy statement (especially if one doesn’t have long standing ties to East Asian culture or Regional religious practice!) and can accidentally play into sinophobic phrasing and attitudes.

Buddhism as a practice and way of life has a very different presence in writers centuries ago compared to now, as well as how we use religion in audience-involved stories. And such I find it an interesting shift regarding a game made with an international and widely multi-religious audience (that isn’t consuming it as a psycho-socio poem compared to a much smaller and more culturally homogenous readerbase. I think the friction caused by thematic changes is more due to how the game relays the physical journey so closely with reusing characters and having to shift them according to the foundational changes- if it was closer to other written “sequels” that created characters connected to the original cast through descending from them etc, the changes wouldn’t grate on completed arcs or how we compare the experience to wukong’s parallel one

No, I do not have any direct personal cultural connection to Buddhism, Daoism, or Confucianism. I live in Asia, though, and beyond my research of JTTW, I do study religion here (with more of an emphasis on folk religion as it pertains to the Great Sage). My negative view of Black Myth: Wukong is colored by my deep love for the original story. In general, I don't like adaptations.

Thank you for your explanation of the game.

#Asks#Journey to the West#JTTW#Sun Wukong#Monkey King#Black Myth: Wukong#Black Myth Wukong#Chinese religion#Buddhism#Taoism#Daoism

161 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wuxia is a popular Chinese literary genre, also known as wuxia xiaoshuo (武 侠小说, literally “martial arts fiction”). The genre consists of three components: wu (武, “martial arts” or “the arts of fighting”), xia (侠, “knighterrant”), and xiaoshuo (小说, “fiction”) (Ni 1980). Rooted in the spiritual and ideological traditions of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism, wuxia stories feature the adventures of a warrior xia and his/her skills in martial arts, as well as the themes or principles of xia (e.g. chivalry, altruism, justice, and righteousness). An important aspect of wuxia is its setting, known as jianghu (江湖, literally “rivers and lakes”), that is, an alternate society created by xia in opposition to the authority (Chen 2010, 108). This alternate society finds a concrete form in “the complex of inns, highways and waterways, deserted temples, bandits’ lairs, and stretches of wilderness at the geographic and moral margins of settled society” (Hamm 2005, 17). Jianghu also refers to a semi-Utopia where xia punishes evil and exalts goodness out of their chivalric imperative to “carry out the Way on Heaven’s behalf” (Chen 2010, 109). Classics such as Water Margin (or Outlaws of the Marsh) and Journey to the West solidified wuxia as a genre, with the former establishing “the literary formula emulated by later writers whereby righteous men choose to become outlaws rather than serve under corrupt administrations” (Teo 2015, 20) and the latter being “a source for supernatural elements in contemporary wuxia literature” (Rehling 2012, 73). Dang Li (2021) The Transcultural Flow and Consumption of Online Wuxia Literature through Fan-based Translation, Interventions, 23:7, 1041-1065, DOI: 10.1080/1369801X.2020.1854815 https://doi.org/10.1080/1369801X.2020.1854815

#wuxia#cdrama#jianghu#language#translation#chinese#my stuff#sorry again gonna keep posting interesting snippets cuz maybe one or two other folks will also be interested

88 notes

·

View notes