#condylarths

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Skull of a new periptychid mammal from the lower Paleocene Denver Formation of Colorado (Corral Bluffs, El Paso County)

Lucas N. Weaver, Jordan W. Crowell, Stephen G. B. Chester & Tyler R. Lyson

Abstract

The Periptychidae, an extinct group of archaic ungulates (‘condylarths’), were the most speciose eutherian mammals in the earliest Paleocene of North America, epitomizing mammalian ascendency after the Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) mass extinction. Although periptychids are mostly known from fragmentary gnathic remains, the Corral Bluffs area within the Denver Basin, Colorado, has yielded numerous exceptionally well-preserved mammalian fossils, including periptychids, from the earliest Paleocene. Here we describe a partial cranium and articulated dentaries plus an additional unassociated dentary fragment of a small-bodied (~273–455 g) periptychid from ca. 610 thousand years after the K–Pg mass extinction (Puercan 2 North American Land Mammal ‘age’) at Corral Bluffs. Based on these new fossils we erect Militocodon lydae gen. et sp. nov. The dentition of M. lydae exhibits synapomorphies that diagnose the Conacodontinae, but it is plesiomorphic relative to Oxyacodon, resembling putatively basal periptychids like Mimatuta and Maiorana in several dental traits. As such, we interpret M. lydae as a basal conacodontine. Its skull anatomy does not reveal clear periptychid synapomorphies and instead resembles that of arctocyonids and other primitive eutherians. M. lydae falls along a dental morphocline from basal periptychids to derived conacodontines, which we hypothesize reflects a progressive, novel modification of the hypocone to enhance orthal shearing and crushing rather than grinding mastication. The discovery and thorough descriptions and comparisons of the partial M. lydae skull represent an important step toward unraveling the complex evolutionary history of periptychid mammals.

Read the paper here:

Skull of a new periptychid mammal from the lower Paleocene Denver Formation of Colorado (Corral Bluffs, El Paso County) | Journal of Mammalian Evolution (springer.com)

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

It Came From The Wastebasket #20: Colossally Convoluted Condylarths

"Insectivora" was a wastebasket taxon so bad it had to be revised multiple times, but there's another particularly infamous case in mammal taxonomy that's still in the process of being resolved – the "condylarths".

This group was first created in the early 1880s, during the Bone Wars, and initially was just a subgroup of odd-toed ungulates containing only the phenacodontids. But just a few years later Condylarthra was promoted up to its own order, and groups like the periptychids and hyopsodontids were added in too.

Then over the next few decades various groups were added and removed from the condylarths, most notably with the mesonychids and arctocyonids being brought in from their previous position with the creodonts.

By the mid-20th century the condylarths had become a big convenient dumping ground for any and all "primitive" ungulate-like mammals that didn't easily fit into any modern groups, ranging in age from the early Paleocene through to the early Oligocene. But it soon became apparent that they had the same problem as the "insectivores" – there weren't really any unique anatomical features that united all these animals together.

They generally had rounded-cusped molar teeth and hoof-like toes, but they also had rather generalized "primitive mammal" features and a diverse range of ecologies. Some were small herbivores, but others were coati-like or dog-like omnivores, and some were even bear-sized carnivores.

From left to right, top row: Hyopsodus lepidus (hyopsodontid), Meniscotherium chamense (phenacodontid), Arctocyon primaevus ("arctocyonid"). Bottom row: Ectoconus ditrigonus (periptychid), Mesonyx obtusidens (mesonychid)

It wasn't even clear how the various different condylarth groups were actually related to each other. The best guess was that arctocyonids had arisen from within the "insectivores", with a Protungulatum-like form as the common ancestor of all the other condylarths. Where exactly modern ungulates had then evolved from within the condylarths was also still uncertain.

This looks familiar (Image sources: http://hdl.handle.net/2246/358 & https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/pepe-silvia)

Cladistic analysis in the 1980s began to tackle the confusing pile of assorted condylarths, and showed that they weren't the single ancestral source of all modern ungulates, but instead a loose collection of several unrelated groups from all over the ungulate evolutionary tree. Arctocyonids, periptychids, and hyopsodontids were placed as early "primitive" lineages, phenacodontids were loosely linked with the ancestors of odd-toed ungulates once again, and mesonychids were considered to be the ancestors of whales.

…And if you know modern mammal phylogeny you'll probably see some big problems here. 🐘 (Image source: https://doi.org/10.1017/S2475263000001343)

And, once again paralleling the mess of the "insectivores", it wasn't until genetic methods became available in the late 1990s that larger-scale ungulate relationships began to be properly resolved. The paenungulates (elephants, hyraxes, and sirenians), which had been traditionally considered to be a major branch of ungulates, were removed entirely and reclassified as afrotheres. And, along with some new fossil discoveries, whales were recognized as having actually evolved from within the even-toed ungulates instead of from mesonychids.

This shake-up threw the still-problematic "condylarth" classifications back into question – with some "condylarths" turning out to also be afrotheres instead of true ungulates.

Today the actual relationships of the main "condylarth" ungulate families are still in the process of being figured out, and there's a lot of remaining uncertainty and disagreement about them.

Phenacodontids seem to have mostly maintained their traditional position as early odd-toed ungulates, and hyopsodontids may potentially be part of this group too – possibly as members of the hippomorph lineage, closely related to horses and brontotheres. Arctocyonids might be a wastebasket themselves, with some studies finding them to be a mix of several different archaic ungulate lineages. Periptychids may have links to the even-toed ungulates. The mesonychids, meanwhile, are now generally considered to be a separate order from the traditional "condylarths", and may be either an early branch of the even-toed ungulates or much more basal ungulates closely related to the "arctocyonids".

Since the term "condylarth" no longer has any real taxonomic meaning some paleontologists have proposed replacing it with "archaic ungulate" to distance from the historical messiness of the old name. But this hasn't really caught on, and many papers still use "condylarth" in a very loose sense to refer to an "evolutionary grade" of early ungulates of unclear evolutionary affinities.

———

And while that's the last main entry for this month, we're not quite done yet. There's still one weekday left in October, and after digging through so many taxonomic garbage cans there's only one place we can go now.

…See you in the trash heap.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#it came from the wastebasket#wastebasket taxon#taxonomy#condylarths#ungulate#mammal#paleontology#art#science illustration#paleoart#palaeoblr

204 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meet Three Cat-Sized Mammals That Survived After Dinosaurs Died

Meet Three Cat-Sized Mammals That Survived After Dinosaurs Died

Palaeontologists have found fossilised teeth and jaws of three hitherto unrecognised mammals — Conacodon hettingeri, Miniconus jeanninae, Beornus honeyi — in the Great Divide Basin of Wyoming. The fossils suggest that these mammals were not bigger than a giant rodent or a small-sized cat and thrived during the early Puercan age, within almost 328,000 years after the dinosaurs disappeared. They…

View On WordPress

#beornus honeyi#CatSized#conacodon hettingeri#condylarths#Died#Dinosaurs#fossils#mammal new species condylarths periptychids fossil discovered wyoming post dinosaurs cat-sized mammals#mammals#Meet#miniconus jeanninae#periptychids#post-dinosaur world#Survived

0 notes

Text

Multituberculate Earth: Meniscoessidae

Meniscoessus is probably one of the most referenced multituberculates, if only because it occurs in the well known Hell Creek Formation where T. rex roamed. It is at times placed in the clade Cimolomyidae, but this seems to be a weakly supported clade with its alleged members cropping up in Ptilodontoidea and Djadochtatheroida (Meniscoessus itself seems to be just outside the clade containing these two groups). As such, animals closely related to Meniscoessus are referred here with the less ambiguous Meniscoessidae.

Meniscoessus crops up in the earliest Paleocene deposits, suggesting it crossed the KT boundary. It was a herbivore, albeit not as specialised as taeniolabidoids for instance, retaining a mid-sized plagiaulacoid. In this timeline its descendents dispersed across North America, Asia and Europe in a pattern much akin to “condylarth” grade ungulates like phenacodontids, but barring a few places like the Iberian Peninsula these animals were never particularly common, nor did they grow much larger than a dog. The Asian radiation of lambdopsalids, the spread of boffiids across Europe and the arrival of ferugliotheriids to North America all produced successful radiations of small to mid-sized herbivores, leaving meniscoessids as a group rather unspeciose, with usually only one taxon per site if any at all.

Thus, when the PETM hit, it was no surprise that they pratically perished. What is surprising, however, is that they didn’t go completely extinct: against all odds, they made it into Balkanatolia just as it became an island continent once more.

Here, they thrived across the Eocene, and in the absence of competitors they underwent an explosive radiation of species, for the first and last time in their existence. Some underwent insular dwarfism and became small mouse analogues; others became arboreal frugivores and folivores, like multituberculate sloths (with spider monkey prehensile tails), others still became gracile animals like clumsy attempts at making a multituberculate answer to a horse or a tapir. Their situation mirrors that of pleuraspidotheriid ungulates in our timeline, another clade found across Europe in the Paleocene but reduced to Balkanatolia in the Eocene, where they too thrived without competing ungulates or rodents.

In this island continent meniscoessids co-existed with kogaionids, Balkanatolia’s apex carnivores and their frequent predators; with galulatheriids, which occupied the largest herbivore niches as well as semi-aquatic ones few meniscoessids explored; and with relictual metatherians, too generalistic to compete with them either.

In our world Balkanatolia connected with Asia in the mid-Eocene, spelling the end for the local ungulates; not so much here, where higher temperatures meant higher sea levels. Thus, meniscoessids lasted across the Eocene, continuing to evolve in splendid isolation. But all good things come to an end, and if anything this prolonged isolation made the Grand Coupure all the more violent, the sharp temperature drop collapsing Balkanatolia’s tropical biomes while the prolonged isolation made meniscoessids less capable of surviving the new waves of competitors and predators.

In spite of this, some menicoessids apparently made it as recently as the Rupelian/Chattian boundary in eastern Europe and Anatolia, though once more these are rather rare animals.

The future looks bleak for these herbivores, which only had one chance to shine and no other.

#multituberculata#multituberculate earth#multituberculate#speculative biology#spec evo#speculative zoology#speculative evolution

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

mug that says “don’t talk to me about condylarths”

1 note

·

View note

Photo

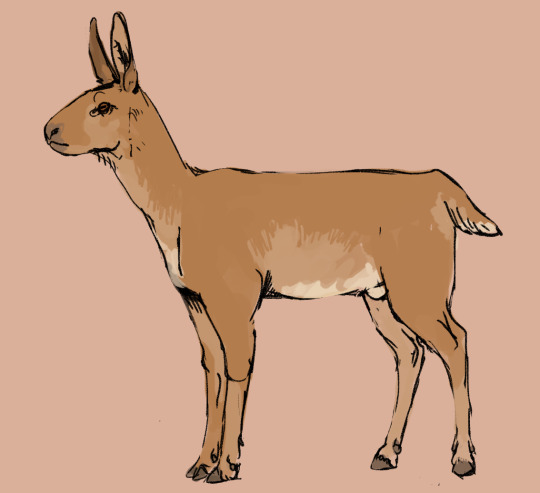

Biologists believe that whales (and modern hoofed animals) evolved from a group of extinct land mammals called mesonychid condylarths. The mesonychids resembled a slim wart hog without the tusks and hoofs.

257 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Retro vs Modern #16: Uintatherium anceps

Discovered in the Western United States during the early 1870s, Uintatherium anceps was part of one of the earlier major conflicts in the the Bone Wars. Nearly 30 different scientific names were applied to various fossil specimens of this mammal in under two decades, and the taxonomic tangle wasn't properly sorted out until nearly a century later in the 1960s when they were recognized as actually all being the same species.

1870s

Paleontologist Edward Cope considered Uintatherium (under the name "Loxolophodon") and its close relatives to be proboscideans – part of the elephant lineage – due to some of the similarities in their anatomy. The first reconstruction of these animals showed this version, depicting elephant-like animals with downward-pointing tusks, short tapir-like trunks, and the multiple bony projections on their skulls speculatively shown as attachment points for large antler-like horns.

Cope's rival Othniel Marsh heavily criticised that interpretation of Uintatherium, arguing that these huge mammals were instead a separate group within the ungulates named dinoceratans – although this wasn't really as huge of a classification difference as it seems today, since at the time proboscideans were also considered to be ungulates!

The dinoceratan ungulate interpretation quickly won out, and for a while in the 20th century Uintatherium actually became a fairly popular and well-known prehistoric mega-mammal, commonly included in collections of cheap plastic "dinosaurs" and usually depicted as more of a knobbly-headed sabertoothed rhino.

2020s

In recent years the dinoceratans seem to have fallen into obscurity and some degree of paleontological neglect, with little modern work on the group and no major studies for the last couple of decades – although this might be starting to change.

Despite the early ideas about them being ungulates, the evolutionary relationships of dinoceratans have become much more murky over the last century or so. Due to different elements of their anatomy being highly convergent with various other mammals it's easy to find "false positives" in morphological comparisons, and they've been proposed as being connected to a wide variety of groups including "condylarths", "insectivores", rodents, and cimolestans. But some mid-2010s research suggests they were in fact ungulates after all, closely related to early South American forms like Carodnia – a lineage whose own evolutionary relationships are murky, but may have close affinities with modern horses, rhinos, and tapirs.

We now know Uintatherium anceps lived across the Western and South Central USA during the mid-Eocene, about 46-40 million years ago, at a time when warm wet climates extended up into the Arctic and lush tropical-style rainforests covered much of the continent.

It was similar in size and build to a modern white rhino, about 4m long (13') and stood around 1.7m tall at the shoulder (5'7"). It had three distinctive pairs of "horns" on its forehead, snout, and nose, that were similar in structure to the ossicones of giraffids, probably covered in skin and hair rather than keratin. Its elongated canine teeth were protected by bony flanges on its lower jaw, and seem to have been a sexually dimorphic feature that was much more prominent in males.

It also had an oddly concave skull, with its forehead dipping inwards, and an unusually tiny braincase for its size. It probably wasn't a particularly intelligent animal, but it didn't really need to be – as one of the first types of herbivorous mammal to get truly huge in the early Cenozoic, a fully-grown Uintatherium probably had no natural predators at all.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#retro vs modern 2022#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#uintatherium#uintatheriidae#dinocerata#ungulate#mammal#art#sabertooth

765 notes

·

View notes

Text

Multituberculate Earth: Taeniolabidoidea

Derived lambdopsalid Cervochenia noduonti by foulserpent. Noticed hooved feet, digit reduction and MASSIVE DONG THAT EVOLVED AS A DISPLAY DEVICE.

(As with all animal pages so far, this only goes so far into the Oligocene… for now. )

Taeniolabidoids are the cimolodont group most adapted to herbivory, having lost their plagiaulacoids and expanded their molars into larger grinding surfaces; while the incisors didn’t grow perpetually like in rodents, in any least some species they kept emerging after the roots closed. Traditionally interpreted as sister-taxa to kogaionids, the most recent consensus seems to place them as slightly closer to the main cimolodont clade rather than them, making them essentially the second most basal lineage.

They first evolved in the Late Cretaceous, with Yubaatar and Erythrobaatar in Asia and Bubodens in North America. Successfully crossing the KT event in spite of their herbivorous habits, they soon diverged into two major clades: Taeniolabididae, occuring in North America and attaining large sizes (the iconic Taeniolabis taoensis weights somewhere between 30 and 100 kg depending on the study, making it not only the largest multituberculate known but also one of the largest mammals of its time) and Lambdopsalidae, ocurring in Asia and mostly diversifying as burrowing herbivores. In our timeline, the former die out in the Danian and the latter endure until the PETM, in environments otherwise dominated by rodents with no signs of diversity decrease; they easily make a strong case for rodents not being the main reason why multituberculates went extinct.

In this timeline, both groups endured, obviously. Idiot.

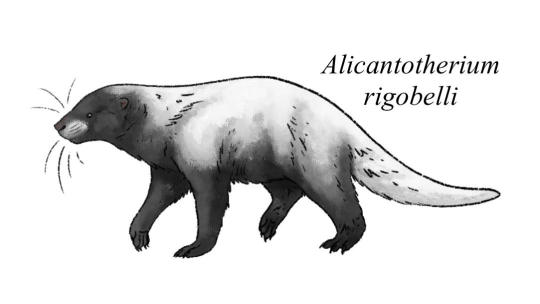

Alicantotherium rigobelli, from the early Paleocene of Bolivia. By pale.relics.

Taeniolabidids kept diversifying as large sized herbivores past the Danian in this timeline, their trajectory in some ways mirroring that of large placental herbivores from our timeline like pantodonts and “condylarth” ungulates. They became the dominant megafaunal herbivores in the northern continents, the largest species weighing up to a ton. Their diversity is particularly high in North America and Europe, with only a single genus in Asia, Kamuilabis. One species, Alicantotherium rigobelli, also occurs in the Santa Lucía Formation of Bolivia, suggesting a short lived excursion into South America.

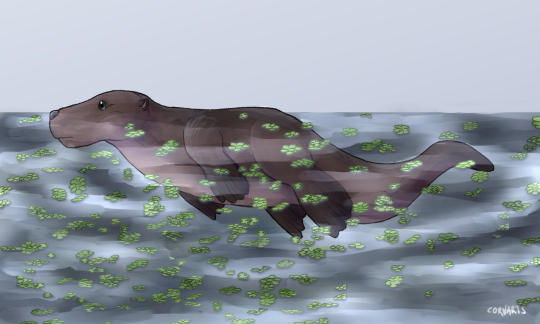

Taeniolabis itself might have already been semi-aquatic, so it is of no surprise that several Paleocene genera were already exploring aquatic niches (though many were unambiguously terrestrial). Most notably is footprint evidence suggesting they foraged on the coastline, the earliest Cenozoic evidence of mammals exploiting the sea and mirroring our world’s pantodonts in this regard.

The PETM saw a reduction in size much as in our world, with semi-aquatic species in particular prevailing over more terrestrial ones. The arrival of gondwanatheres in Asia pretty much ended their reign there on land, but North America and Europe saw their local diversity quickly recover in the Eocene’s nascent rainforests and reclaim their position inland (though in Europe they were comparatively rare, the dominant giant herbivores being gastornithid birds). Some of these forms reached as many as 3 tons, dwarfed only by African galulatheriids and South American/Antarctic/Australian mesungulatid dryolestoids.

Though these unique polar swimmers eventually died out, other taeniolabidids would explore marine environments further south in the Caribbean, and later spread across the Tethys as far east as India and westwards in the Pacific both to the northwest and South American coast, grazing on the abundant sea grass meadows. Some even arrived to Afro-Arabia and South America, returning inland to occupy freshwater niches.

With the Grand Coupure the reign of taeniolabidids on the northern continents came to an end. Collapsing rainforest biomes and herds of Asian gondwanatheres marching towards North America and Europe resulted in the extinction of the giant land herbivores, starved and outcompeted. But in the sea, taeniolabidids reached unparalleled success: the descendents of the second wave of sea goers achieved a cosmopolitan distribution, in polar waters even reaching sizes comparable to those of our largest desmostylians and Steller’s Sea Cow.

Barred from the mainland, the waters and islands hold a bright future for these majestic animals.

Cervochenia nuada (distinct from anterior species by slightly longer flag head) by foulserpent in display position, foaming like a camel ALSO MODIFIED FLAG-LIKE DISPLAY BENIS

The Paleocene saw a great diversity of lambdopsalids in their Asian homeland as in our world, except more as their placental competitors came crashing down. They seem to have largely replaced the local herbivorous djadochtatheroideans, ranging from small pika size and like burrowers to tall browsers and even hopping forms (as if mocking djadochtatheroideans further). One of their most distinguishing features in real-like was uniquely hypsodont molar teeth, suggesting that they were among the first local mammals to be specialised grazers; here, this is certainly apparent as they are among the first Cenozoic multituberculates to display adaptations for cursoriality in this timeline, marking them as well adapted for open biomes.

The PETM was especially harsh as it coincided with the collision with India, bringing gondwanathere competitors to Asia. Combined with the spread of rainforests, most of the earlier lambdopsalid radiation became extinct, with no species above 10 kg crossing the Paleocene/Eocene boundary. The small sized survivors, however, thrived and even colonised North America, spreading as small sized herbivores swiftly running across the forest floors and/or digging.

The Eocene saw the reduction of digits, with the forelimb coming to be supported on two toes while the hindlimb on a single one, an arrangement similar to some of our bandicoots particularly the Chaeropus genus. This seems to be a compromise between both increased cursoriality and retained digging habits much as in bandicoots, and like them it lead to the development of true hooves. In our bandicoots young are deposited in the pouch by placental stalks, thus removing the need for grasping forelimbs; conversely, juvenile monotremes (which as adults also have non-grasping, specialised forelimbs) actually move about very often in the mother’s pouch in search of mammary glands. Do lambdopsalids need a way around like bandicoots or don’t like monotremes? YOU DECIDE. Disregard that, multituberculates apparently gestated live young like placentals do there’s no need to overexplain the hooved forelimbs.

With the Grand Coupure, lambdopsalids moved into Europe, displacing several local small herbivores like ferugliotheriids and boffiids. With the spread of open grasslands they were allowed to attain large sizes once more, some Oligocene forms as large as an elk. In general there is some faunal provincialism, with lambdopsalids being more common in Eurasia and adalatheriids in North America, though both groups occurred across both landmasses.

Like all non-placental mammals multituberculates have bifurcated penises, and in lambdopsalids this lead to a truly unique evolutionary novelty. In derived species, one of the heads evolved into a flag-like organ and lost its urethra, while the other retained it and remained relatively small, just long enough to do its job. Thus, rather than horns and tusks the lambdopsalids probably developed the most direct sexual displays of any tetrapod.

As the world keeps cooling and drying and plains spread, lambdopsalids have bright horizons ahead. Soon, Afro-Arabia and Asia will collide, leading to interesting results…

#multituberculate earth#multituberculate#multituberculata#speculative zoology#speculative biology#spec evo#speculative evolution

6 notes

·

View notes